Abstract

Online social networks can be considered harbingers of modernity and are claimed to encourage individualization in religious practices. Nevertheless, religious minority groups, including reclusive communities, legitimize their use for religious and communal purposes. Accordingly, social networks are emerging as dynamic third spaces of identity reflections on key issues of lived religion. This study examined how members of a religious group negotiate their identity over online social networks. Accordingly, we conducted a content analysis of 70 ultra-Orthodox Jewish public (Haredi) WhatsApp groups and 40 semi-structured interviews with participants. Findings revealed three primary facets of identity performance: communal affinity; proclaimed conformism and practiced agency; and contesting dogmatism and pragmatism. Through these facets, a new social identity is crystallized within the Haredi sector in Israel. Thus, the secluded spaces of WhatsApp groups enable a marginalized grassroots religious public to promote incremental social change without shattering communal boundaries.

1. Introduction

Over the last two decades, there has been a notable proliferation in the use of online social media in religious communities. While social media is often lauded as enabling open communication, identity play, the orchestration of multiple identities, and leisure-laden practices (Danet 2001), for religious fundamentalist communities its affordances raise concerns, as they strive to uphold a unified, consistent system of role-identities in which each member holds a single identity (Heilman 1995, p. 86). These communities seek to maintain tight control over information and its dissemination (Nolt 2016; Turner 2007), aiming to ensure the continued existence of solid socialization structures in which to nurture the pious individual and communal identities to which they aspire.

The use of smartphones and social media is often viewed through the framework of digital divides, literacy, and socio-economic gaps (Schejter and Tirosh 2016). However, media resistance, such as avoiding smartphones for moral and religious reasons, is different. Avoidance of mobile-phone use is often identified with identity management and moral piety, particularly among ultra-religious communities and their elites that ostentatiously reject advanced communication devices as gateways to profligacy and sin (Neriya-Ben Shahar 2020).

Between media resistance and adoption, the effect of limited smartphone and social-networks’ use on the identity of community members who employ these technologies, and, accordingly, on these communities’ social structure has yet to be thoroughly analyzed. Thus, this study asks how members of a religious society negotiate their identity over online social networks.

To address this query, we focus on the ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) society in Israel, and explore members’ identity construction over WhatsApp groups. The Jewish ultra-Orthodox branch of Judaism (Haredi), sanctifies the Jewish codex of laws derived from the Bible and formulated during the 7th century (Talmud). The Haredi lifestyle stands in stark opposition to the Israeli mainstream. The Haredi sector comprises 13.5% of its population, and is the fastest growing sector in the country. It is also the most poverty-stricken sector in Israel. All these, together with the growing numbers of ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities abroad, attract scholarly attention from many disciplines. With regard to modernity, and specifically to ICT use, recent surveys indicate that, despite the overarching clerical objections to smartphones, their use has become popular, with almost all Haredi smartphone owners also using WhatsApp.

The use of WhatsApp groups among Haredim has greatly increased during the last five years (Askaria Surveys Company for the Haredi Society 2020). These groups offer an unsupervised sphere, enabling discreet discussions within circles of trusted peers, thus serving as an ideal platform to integrate social change into participants’ identities. Previous studies investigated Haredi entrepreneurship of, and through, web use and their effects on Haredi society (Golan and Mishol-Shauli 2018; Katzir and Perry-Hazan 2019), as well as Haredi leadership’s resistance to these efforts (Rosenberg and Blondheim 2021). However, the lived experience of Haredi social networks’ participants has yet to be studied. Therefore, we suggest that exploring designated Haredi discussion arenas, i.e., WhatsApp groups, bridges this gap. As gender roles in the Haredi society are strictly segregated, this article focuses on Haredi men1.

The main phenomenon highlighted by our findings is the deliberation of a distinct ‘working Haredi man’ identity. We analyze this identity’s expressions by projecting them on three identity axes that emerged from the contrasts between the traditional Haredi identity and the typical online social networking identity. Data collection for this study includes interviews with 40 Haredi users of WhatsApp groups and participant observations in over 70 WhatsApp groups, as well as several Telegram and Facebook groups, all designated ‘Haredi’, thus combining online and offline methods of qualitative research.

The findings show working Haredi men engage in a fragile process where they try, often unintentionally, to achieve two aims, which occasionally conflict: (1) Form peer groups in which they overtly and covertly solidify their alternative male identity and (2) Maintain their online groups well within the boundaries of the mainstream Haredi lifestyle and discourse. These aims clash on several levels. The first is that the favored, and in some sub-denominations the only, male identity within this pious society is that of a full-time Torah scholar (Avrech), secluded from the outside world. Thus, career-oriented individuals who engage in frequent interactions with non-Haredim threaten Haredi boundaries. The second level of discrepancy stems from the constant efforts of Haredi leadership to curb the use of smartphones, as they allow access to unfiltered information. Working Haredi men were found to use WhatsApp groups to achieve legitimization by establishing an inferior-yet-respected social class, right below that of the elite class of full-time Avrechim. They form a self-empowering subgroup on social media platforms, a subgroup that constitutes their self-identity and status, while still accepting the pillars of the existing social order, although these block them from becoming part of their society’s elite.

2. Approaching Identity

Our approach to identity derives from studies of online identity and ultra-religious identity. Research on male identities in reclusive or ultra-religious communities has found the role-identity paradigm (Stryker 2007) to be the most appropriate, as it stresses the limits that socially prescribed roles and scripts place on individual behavior (Marty and Appleby 1991; Stadler 2009). Scholars describe pious considerations and religious prescriptions as forming a “master/primary identity”, foreshadowing and brokering all other gender, familial, professional or national facets of their identity (Castells 2011; Tavory 2016).

The literature on identity expressions on online social network platforms suggests analyzing it via the interpersonal symbolic interaction paradigm (Turkle 1995). While exercising individual choices concerning with whom to interact, social network participants usually enact what they feel is their “real” identity (or at least selected parts of it) in these platforms. Researchers posit that the main reason for this identity coherence is that most interactions on social networks nowadays are with offline friends and acquaintances (Talmud and Mesch 2020).

3. The Interface between Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and Religious Societies

This study focuses on the communication practices of actors in Haredi-dominated online communities. Studies on online communities have highlighted contingency, creativity and playfulness, and delineated a typical social-network identity as comprised of agency, pragmatism and individual-orientation tenets (Danesi 2017; Danet 2001; Rainie and Wellman 2012; Schejter and Tirosh 2016). However, Barzilai-Nahon and Barzilai (2005) claimed that when members of ultra-religious communities go online, they reproduce their fundamentalist identity rather than adopt the typical online identity. In contrast to their unidirectional conclusion, Campbell (2012), in her comprehensive survey of the relationship between online and offline religion, stressed that online properties affect offline praxis, but not in a universal form. In her theory of Religious–Social Shaping of [communication] Technology (RSST), Campbell underscored this importance of context, by showing that much of the interplay between new-media platforms and religious users is defined by individual choices that are dictated by structural and social elements of their variant of religious identity and communality (Campbell 2017).

Hoover and Echchaibi explored the effects of digital media on social possibilities, and suggested relating to sites of online religious expressions as “third spaces”, thus borrowing and extending Oldenburg’s definition of third places (1989) as implementing various types of “in-between-ness” (Hoover et al. 2014). Hoover and Echchaibi posited various types of possible “in-between-ness” such as private and public, home and work, tradition and secularism, authority and autonomy, individual and community and static and generative. Establishing on which of these axes the Haredi participants utilize this online-enabled “in-between-ness” and which axes are set to re-enact their offline identity is an important part of understanding Haredi online identity negotiations. Hoover and Echchaibi claimed that these third spaces are becoming “the source of identities, ideas, claims and solidarities” that later also affect the offline world (Hoover et al. 2014).

Both RSST and the third spaces theory focus on the actions of religious individuals online. Studies using these perspectives often highlight the experiences of tech-savvy entrepreneurs and daring social activists in their efforts to change their religious communities (Campbell 2020; Golan and Fehl 2020). Other works in these tracts have examined individuals who choose to reject media affordances (Neriya-Ben Shahar 2020). Conversely, the theory of mediatization takes a more structural approach to studying the effects of media on society. Researchers adopting this paradigm examine changes in the forms and practices of religious establishments and “mainstreams” caused by their adaptation to the media-saturated world surrounding them. Mediatization studies describe how the new media affect local religious authorities (Francesc-Xavier 2015), how religious establishments attract followers by integrating media specialists into their workforce (Golan and Martini 2019) and how mainstream religious discourse changes to accommodate new media affordances (Mishol-Shauli and Golan 2019).

4. Haredi Male Identity and Discrimination against Working Haredi Men

Originally, Jewish ultra-Orthodoxy allowed men to work for a living, with only a small selected elite dedicating their entire time to the study of Torah. Howerver, throughout the long 19th century and into the 20th, the rise of attractive alternatives in the form of Zionism and secularism, together with persecution by various regimes culminating in the Holocaust, nearly demolished Jewish ultra-Orthodoxy. As a result, when the State of Israel was founded, Haredi leaders declared that in order to resurrect this branch of Judaism, every Haredi man must dedicate himself to full-time study of the Torah, regardless of personal preferences or competency (‘Avrech’), thus legitimizing a sole male identity. The successful implementation of this policy resulted in the term ‘the society of learners’ (Friedman 1991). While many Haredi communities maintain close ties with Jewish ultra-Orthodox abroad, such legitimization of a sole male identity is unique to Israeli Haredim (although, lately, US media reports suggest some Hassidic courts in New York are pursuing this direction). In order to keep the community unified and set in its ways, unprecedented power was given to its religious leaders to rule on every aspect of Haredi life; thus, regarding them to be the living embodiment of the scriptures and thus infallible (‘Daat Torah’) (Brown 2017). Accordingly, the literature tends to characterize the ideal Haredi male identity as dogmatic, collective-oriented, conformist and comprehensive (Brown 2017; Zoldan 2019).

The establishment of the society of learners has resulted in a distinct attitude towards male work among the Haredim, deeming it as inferior and even degrading. However, not all Haredi men fit the mold of the full-time Avrech. Those who do not (as well as their families) thus suffer discrimination within Israeli Haredi society. A Haredi is considered a working man if his vocation’s orientation is beyond a Yeshiva or a Hasidic court’s walls, and more so if it is carried out with non-Haredim and/or in a non-Haredi environment. In the Haredi public sphere, their opinions are often assumed to be a priori invalid, labeled ‘the opposite of Daat Torah’. Moreover, they suffer either limited matrimonial options, or their children are not allowed to study in some of the prestigious Haredi schools (Lehmann and Siebzehner 2009). Several grassroots Haredi movements have tried to change this state of affairs, but failed and disbanded.

5. Haredi Identity and New Media

Haredi Judaism is comprised of various sub-denominations and was traditionally divided by scholars to Sephardi, Lithuanian and Hassidic. However, at least in Israel, the individual lived religion of most Haredim diverges within their sub-denomination, as each is affected differently by interactions with other sub-denominations and the surrounding secular society. Therefore, for this study, we find the typology along a conservative to modern axis, as recently formulated by Cahaner (2020), to be more suitable. With regard to various aspects of modernity (ICT use, academic studies, leisure activities and more), Cahaner found Israeli Haredi society to be divided into four categories, from the most removed from modernity (28%) to modern Haredim (11%). In between are the mostly removed from modernity Haredim (32%), and the somewhat modern Haredim (29%). Focusing on new-media use, although the contrast between the previously described online identity characteristics and those of Haredi identity is evident, mediatization did not skip Haredi men. Either for economic reasons (the Haredi sector in Israel is by far the most poverty-stricken), or in order to reach out to new potential recruits, Haredi spiritual leaders have grudgingly allowed many of their flock to go online by authorizing smartphone ownership and WhatsApp participation on an individual basis. However, use of smartphones is still heavily contested as the Haredi men who participate in WhatsApp groups, even if for vocational purposes only, are considered problematic as they still deviate from the Avrech identity track. While most working Haredi men still suffer social discrimination, these discriminations seem to diminish, and current research perceives efforts to remove smartphone use to be a rearguard battle (Rosenberg and Blondheim 2021). Accordingly, an estimated 30% of adult Haredim (men and women) own a smartphone and have a WhatsApp profile (Askaria Surveys Company for the Haredi Society 2020).

6. Theoretical Framework: Constituting Religious Identity in Messaging Platforms

To uncover the identity dynamics that evolve during the partial integration of ICTs in the community, this study draws on a structural identity framework to pinpoint ongoing manifestations within the identity zeitgeist. It associates the theoretical underpinnings of discourse performance theory with those of structural theories of identity. Discourse theorists highlight power dynamics that are manifest in textual expression (Van Dijk 1993). Performance scholarship captures moments of cultural expression (Case 2009). These outlying concepts are manifested by the grounded public expressions that occur in WhatsApp groups. They both express identity and reconstitute it by socializing its users. Accordingly, to understand the identity formation that evolves during the legitimization of ICT use for working Haredi men, three structural axes that contrast the characteristics of online and reclusive religious identities were explored:

1. Dogmatism–Pragmatism: Dogmatism refers to a “closed organization of beliefs and disbeliefs about reality organized around a central set of beliefs about absolute authority, which, in turn, provides a framework for patterns of intolerance… towards others” (Rokeach 1954, p. 195), and is a characteristic of ultra-religious identities (Swindell and L’Abate 1970). Thus, dogmatic identity reflects an inclination toward maintaining the social order and upholding existing identity properties. Pragmatic identity, on the other hand, is open to change and adaptive to changing circumstances. Online identity is often depicted as flexible and inclined toward moratorium. In other words, it derives from social circumstances that allow a temporary deviation from commonly accepted norms (Kahane 1997). Online identity is also characterized as pragmatic, as it is highly susceptible to contingent influences (Danet 2001);

2. Collective–Individual Orientation: Individual-oriented identities are characterized as emphasizing values such as self-fulfillment and primary commitment to the self and the nuclear family (Darwish and Huber 2010). This type of characterization has been highlighted by online identity researchers, such as Rainie and Wellman (2012) who termed it “networked individualism.” In contrast, collective-oriented identities reflect actual, desired or imagined membership in a previously defined and more close-knit community. They are characterized as giving precedence to collective interests over individual ones (Darwish and Huber 2010). This orientation fits with traditionalist and fundamentalist communal settings (Marty and Appleby 1991);

3. Conformism to Structural Forces–Agency: Identity can be dominated by structural forces or shaped by personal agency. These factors interrelate: when individuals apply agency in shaping and expressing their identity, they do so in response to the various social structures to which they belong or to the crowd with which they interact (Stryker 2007). Conversely, structural forces can be viewed as instilling and imposing identity, image and praxis on the individual (Biddle 1986). Online identity research often attributes greater agency to the individual in the shaping of identity, consistent with symbolic interactionism (Turkle 1995). Research on religious groups, and particularly bounded communities, frames individual identity as being dominated by external structures, consistent with role-identity theory (Marty and Appleby 1991).

We contend that through an exploration of these axes on communal discourse in WhatsApp postings and offline rhetoric we will be able to identify the dynamics of key identity concepts among reclusive religious communities experiencing identity ambivalence confronting modernity. To answer the question of how members of a religious society negotiate their identity over online social networks in our case study, we look at both their online tracts and their offline conduct. We ask how they negotiate and express their Haredi identity online, first by studying their choices of groups to participate in and groups to avoid, and then by researching their discourse in the groups they participate in. Offline, we ask how their use of WhatsApp integrates into their Haredi life. We also ask how their nuclear family and community respond to their use of WhatsApp, and if they face resistance, how do they respond.

7. Methodology

7.1. Fieldwork: Engaging WhatsApp Groups and Conducting Interviewees

WhatsApp is a cross-platform instant messaging application, mainly for smartphones, that enables users to send and receive location information, images, video, audio and text messages in real-time to individuals and groups of friends at no cost. WhatsApp groups include at least one administrator. The first administrator is the group’s initiator. Administrators determine the groups’ title and primary topics, as well as control user affordances. Scholars have conducted research on mobile texting emphasizing age groups (especially youth), gender and socio-economic differences (Zelenkauskaite and Gonzales 2017). However, religion and communal affiliations have been largely overlooked as a meaningful cultural variable.

Aiming to uncover Haredi users’ experience, interpretations and justifications, we conducted interviews as well as participated in WhatsApp groups. The Haredi society is composed of closed communities to which we do not belong. Many researchers have described the difficulties in achieving access and rapport with interviewees, as academia is often perceived as representing a contesting set of beliefs (Golan and Campbell 2015). We were able to gain the trust of group administrators and interviewees by asking Haredi acquaintances and contacts from previous research to vouch for our credibility. Even so, we were not allowed to participate in all the groups we asked to join, and some participants declined an interview. However, once gaining initial trust, we found that being a sympathetic outsider had specific benefits when discussing contested issues, as previous researchers had already noted (Kusow 2003). Still, being outsiders, even after gaining experience with researching the Haredi public, we often consulted Haredi informants and forums, so as not to miss important subtleties and nuances.

7.2. Research Design

To uncover the identity dynamics resulting from the social change of ICT integration, we explored expressions of identity formation through an analysis of public WhatsApp groups and interviews. More specifically, this study examined the possible effects of social media affordances by analyzing identity expressions, with an emphasis on the axes that highlight the differences between the online and offline: Dogmatism vs. Pragmatism; Collective vs. Individual Orientation; and Conformism to Structural Forces vs. Agency. Accordingly, an interview protocol was prepared, and an initial list of indicators of Haredi identity expressions online was constructed. This list utilized language markers described in the literature, suggested by Haredi informants and/or stem from our previous research experience, and was slightly updated during the research.

7.3. Data Collection and Analysis

This study incorporates two sets of data. The first dataset is comprised of naturally occurring online discourse in public and work WhatsApp groups (see Dotto et al. 2019), the second holds the transcriptions of 40 semi-structured interviews. The interviews were conducted face-to-face, at the interviewees preferred time and meeting place (we did not conduct interviews during pandemic-related lockdowns). Interviews were between 45 and 120 min long. The interview protocol is attached as Supplementary Table S1, the WhatsApp groups coding scheme is attached as Supplementary Table S2. The interviewees’ age ranged between the early twenties to late forties. Four interviewees were single and the rest were married. The number of children of the married men (which not all interviewees disclosed) varied, but was all below the Hared average of 6.6 (ranged from one to five). The interviewees belonged to various Haredi sub-denominations, such as Hassidic courts (Ger, Chabad and more), Lithuanian and Sephardi. While the categories on the modernity axis presented in the literature review (Cahaner 2020) are less distinctive than sub-denomination, the majority of interviewees expressed views that conform to the ‘somewhat modern’ category. Five interviewees considered themselves modern and six defined themselves as conservative (for example, they use WhatsApp on office computers only so as not to own a smartphones). Only one of our interviewees was not a working Haredi man but a full-time Yeshiva Scholar (unmarried full-time Avrech) who secretly operated news-oriented WhatsApp groups. The occupations of the Haredi men interviewed varied and included journalists, therapists, teachers, book editors, computer-engineers and managers in non-profit organizations.

The groups we followed (during 2016–2022) varied with regard to their size and orientation. The most common orientations of the groups were news, music, vocation-oriented, local, religion-oriented and instrumental (e.g., helping the needy, sharing or giving work-tools and furniture, available jobs). Some of the groups had multiple numbers, with administrators coordinating and synchronizing them (to allow more members than possible in a single group). WhatsApp groups have changed over the six years we observed them. The number of members allowed on each group has grown, and new features were added. The feature with the greatest effect on the discourse within groups during our research period was the ability to allow only administrators to post new messages (deployed in 2018). This change has effectively turned most news and religious groups into channels.

Both datasets were imported into Atlas.ti mixed-method software. The online discourse was analyzed according to the ethnography of communication framework as well as functional discourse analysis, focusing on speech events and communities in their cultural context (Hymes 1974; Katriel 2004). Content analysis was applied to the interviews dataset employing categorization techniques (cf. Corbin and Strauss 1998). For reliability, two independent researchers scrutinized the data. Thereafter, we compared and discussed our interpretations of the most frequently recurring symbols and the category sets. We consulted Haredi informants and acquaintances on a regular basis concerning both unclear points and conjectures about which we were not sure.

The ethical design of this study received the formal approval of the university’s IRB. For the interviews, we obtained informed consent and duly concealed the subjects’ names or any other identifying data. Concerning the (constantly developing) online research ethics, we disclosed our identity as researchers in the WhatsApp groups we participated in. Furthermore, group administrators were approached and notified of the study’s objectives.

8. Findings

As smartphone and WhatsApp use are sanctioned on a case-by-case basis to Haredi men for vocational purposes, most Haredi men who use WhatsApp are working Haredi men, i.e., men who do not fulfill the sanctified identity of the full-time Avrech. The ubiquity of discourse surrounding this ‘failure to comply’ to this ideal identity both in the online discourse and in the interviews constitutes the main finding of our research. We identified three primary facets through which Haredi working men were found to deliberate their identity on and through WhatsApp groups: communal affinity; proclaimed conformism and practiced agency; contesting dogmatism and pragmatism.

8.1. Communal Affinity

When asked about participation in non-Haredi groups, most interviewees either stated that all of their groups are Haredi or downplayed the importance of the non-Haredi groups in which they participate. Online networking, in both local and vocational groups, was identified among Haredim from various sub-denominations, with scarce non-Haredi participation. Figure 1 depicts how three Haredi advertisers from different sub-denominations (Belz, Lithuanian and Chabad) discuss best practices in a WhatsApp group for Haredim in the advertising industry.

Figure 1.

A thread discussing advertising practices in a Haredi vocational group.

As the content is non-religious, participants could have consulted non-Haredi peers, yet elected to limit themselves to a Haredi group.

Another manifestation of the primacy of Haredi identity is evident through mass participation in WhatsApp channels for news updates. For example, a Haredi owner of an advertising agency explained:

“I don’t go there [Twitter], but I get Twitter messages via WhatsApp. I subscribed to a WhatsApp channel called “The Haredi Newsline 55”. There is tons of news there, but no licentiousness like “that actress who tripped on the catwalk” stuff. They know what this crowd [Haredim] finds relevant. That’s all the news I need.”

For the interviewee, Twitter is viewed as a morally problematic platform. However, information that originates on Twitter, but is filtered by trusted mediators from within the community is acceptable.

Group types are another aspect of communal affinity. Figure 2 shows an advertisement promoting a network of Kollels (Torah seminaries for married men) for working Haredim, exemplifies this well: The slogan (addressing men) intersects the online and offline meanings of the word ‘group’: “Everybody has a group. What is your group?”, while showing a Haredi man’s hand holding a smartphone with a list of WhatsApp groups:

Figure 2.

Advertisement for a working Haredi Kollel (2019).

The first group on the list is that of the Kollel, followed by work and family groups. Torah is placed above all else. In addition, there is no nuclear family group. This follows the communal prohibition against exposing children and youth to ICTs.

All in all, Haredi WhatsApp users continuously proclaim their affinity to the Haredi collective. This is the frame to which they orient their lifestyle and vocational networks.

8.2. Conformity to the Ideal, Agency in Practice

8.2.1. Conformity to Social Order

Working Haredi men stress their identity by displaying conformism to multiple aspects of the communal social order. The first aspect is rabbinical infallibility. WhatsApp group participants express vehement objections whenever they sense criticism of leading rabbis, even if implicit. The following example is from a Haredi group of politicians and journalists. One of the few religious Zionist participants commented that a key Haredi politician was manipulating leading rabbis. In response, a Haredi participant scolded him and stated: “I respect your right to criticize every public figure, but criticism of the great sages? Protest and even harsher methods are warranted”.

The second aspect of adherence to the Haredi social order is the sanctified status of full-time Avrechim. Participants often expressed regret for not being full-time Avrechim, and most interviewees described leaving full-time Torah studies as a personal crisis. A seasoned journalist described his yearnings to go back to full-time Torah studies:

“If only I had money, someone to fund me, just to sit and study (sighs). My job, I only do it to make a living. I would have gotten more satisfaction out of [Torah] studies. I would have sat in the Kollel knowing that I am serving the Lord right.”

This sentiment was repeated as interviewees often recited this narrative of regret, affirming its importance. In addition, WhatsApp Haredi users confirm the mainstream sentiment towards other social networking platforms. Facebook is rejected by the Haredi mainstream, and an interviewee in his middle 30s conforms to this sentiment:

“I have friends with Facebook profiles but…[hesitates] they don’t fear communal responses. Some of them really don’t care what anyone says about them. I’m not like that. And I don’t want to become like that.”

Thus, although the interviewee openly uses WhatsApp, he considers himself more pious than his friends who use Facebook. He resents their disregard of the communal norms objecting to Facebook use.

The third aspect of the Haredi social order is the subordination of working Haredi men to rabbinical authority concerning the use of WhatsApp and smartphones. All interviewees except three (who define themselves as “modern”) purchased a smartphone and started using WhatsApp only after consulting their rabbi.

A Young Haredi Working in an NGO: “I asked my rabbi. I had a need, the definition in my community is that you are allowed to use the internet only if you have a legitimate need… So I asked my rabbi and he allowed, and told me what [content filter] is recommended.”

All in all, conformism to the Haredi social order was expressed through reaffirming rabbinical infallibility, sanctifying the social status of full-time Avrechim and leaning on rabbinical authority for the legitimization of WhatsApp and smartphone use.

8.2.2. Agency

Once the initial legitimization to use WhatsApp and own a (filtered) smartphone is granted by the rabbi, a communicative moratorium is set in motion. This is to say, the boundaries between legitimate and illegitimate use become somewhat blurred and users are allowed some trial and error in smartphone tracts, as demonstrated in the aforementioned WhatsApp news channels. Although participation in these channels outreach rabbis’ sanctioned sites, working Haredi men exercise their agency in deciding that they are legitimate. Thus, the potential for bridging networks and information outlets via these new communication channels is constrained to fit the Haredi lifestyle.

Some interviewees’ agency went as far as claiming that rabbinical guidance on smartphones and social networks is misinformed and misconducted. They called for rabbinical authorities to stop treating WhatsApp and smartphones as some deadly sin and allow for personal growth and responsibility. These interviewees also considered communal and familial resentment to be either backwards or misguided. The same young Haredi previously describing his adherence to his rabbi described the communal resistance he faces in a completely different tone:

“[Communal resistance is manifested]…mostly through snide remarks. Like “What? Is this allowed?” or “How dare you use this?” It happens two or three times a month. It doesn’t bother me too much. I might answer back if I’m bored. I vividly remember someone muttering an angry remark that “This is not proper”. Later I found out that he has issues with himself and his rabbi, that he was simply frustrated for not getting permission to own a smartphone himself.”

The young Haredi explained his disdain towards communal resistance to smartphones and web use by demonstrating how it stems from illegitimate motives.

Nevertheless, some recurring narratives included disdain and ambivalence towards the app, particularly relating to its allure for leisure activities and the young. A recurring story, appearing both in interviews and groups we followed, describes an addiction-like behavior leading to a personal crisis that is often solved by deleting WhatsApp. The following interviewee described this with exceptional candor:

“This whole social networks thing, it holds sway. A man, or a child, or youth, that opened a WhatsApp group, he feels great… Back when I had WhatsApp, I had a group, I participated in a group of Hasidic music. It was really fun, but think of the implications for a man that gets addicted to this. When I was younger I had difficulties, you understand [Hints of a crisis in faith]? You go to YouTube, you see a film, and another one. It disrupts life. It doesn’t all happen in one day. When a building collapses, it doesn’t collapse in one boom. The foundations start shifting a little, cracks appear, and suddenly something happens and blows everything away. It was all very interesting, but WhatsApp took a lot of time from me. I think that the day I deleted WhatsApp I freed another hour each day for my family and I’m happy about that. Yes.”

The interviewee describes how the agency he found online failed him. He starts his story by describing WhatsApp as time consuming, but suddenly gets agitated and shifts into describing a great personal crisis surrounding his past addiction to YouTube and online content. Complementing this ‘slippery slope’ narrative, other interviewees often lamented how people they know deleted WhatsApp, but later secretly reinstalled it.

Beyond the ambivalence towards self-use, the participants also express uncertainty towards how to educate the younger generation with regard to social media, smartphones and the web in general. The following interviewee is a professional with academic training who lives in a religiously heterogeneous town. He describes a complete work–family separation, with no web connectivity in his home:

“The computer, open web and all that, it’s all here, inside the office. It will never enter my home. Never. I would never want my children to use these things. I think that even if I weren’t a Haredi I would think like this and forbid it at home. Praise the lord that I live in an excellent community that allows me to avoid this [getting my children acquainted with ICTs]. Even better! My community demands that I avoid it!”

This father highlights his role as an educator. He is happy that his community shares his views, but considers the decisions on how and at what age to allow web access to his children to be his parental prerogative. In contrast, the following interviewee describes a dilemma when discussing the smartphone and his children:

“Look, basically they know that I have a device for vocational needs. But, I’m really tiptoeing on eggshells here. On the one hand you educate them and all, on the other hand you have such a device, you understand? So I don’t take it out at home, I don’t even bring it home. At least I try not to.”

This interviewee does not have an office; therefore, he must occasionally use his smartphone at home as well. He feels he does not stand up to his own standards of piety, and is therefore in constant strife. A third Haredi, a journalist living in Jerusalem, describes a completely different reality:

“I don’t think that it’s such a big deal [Haredi youth using smartphones]. It’s one of these signs of adolescence. I think that most young men that are into that, their parents eventually cooperate or even buy them a device. It’s not an issue. It’s not the same as how we experienced our parents living without a phone. Nowadays children grow up in a home with both parents using a smartphone all the time. So it’s only natural that when they get to a certain age, they will already have a smartphone.”

In his narrative, smartphones are part of contemporary youth’s coming of age and developing autonomy, mirroring common modern parents.

Overall, while all interviewees expressed allegiance with Haredi social order, when it comes to their day-to-day use of WhatsApp and smartphones, the interviewees described different narratives. These narratives depict their approaches as stemming from their own decision, sometimes leaning on what is communally accepted, but never following any prescribed guidelines. Some embrace this agency enthusiastically, while others wish for clear rabbinical edicts to follow in what they view as an uphill battle.

8.3. Dogmatism–Pragmatism

8.3.1. Online Contesting Dogmatism and Pragmatism

Occasionally, in response to online expressions of allegiance to non-Haredi political parties, or alternative exegesis of rabbinical decrees, users protested what they saw as transgressions of the Haredi dogma. For example, when a group participant criticized rabbis that encouraged their flock to breach the State’s social distancing regulations surrounding COVID-19, one group participant announced:

“Excuse me but I must protest against the way you speak of the great Torah sages! really disrespectful! it has been said “careful with their amber”.”

Not settling for the previously discussed conformism, the participant evokes Haredi dogma by referring to Talmudic and folklore traditions telling of disasters occurring to Jews who spoke against grand rabbis. However, such dogmatic responses were often rejected by other group users, who resented importing the offline dogmatism online. Users often answered such messages by humorously reminding their initiators that a leisure-oriented online forum is hardly a fitting place for righteous zealotry.

8.3.2. Pragmatism concerning the Future of Haredi Society

As seen above, many interviewees expressed loyalty to the Haredi hierarchy, as well as a desire for their children to become full-time Avrechim or marry such. However, when asked about the future, the interviewees displayed pragmatism and resented the current state of affairs with regard to the society of learners. They challenged the current social order in two ways. First, they challenged rejections from prestigious schools on the basis of fathers’ participation in the workforce. These rejections bar boys’ path to attaining the status of full-time Avrechim. Their second challenge, contrasting with but also complementing the first, is for their sons (or themselves for young adults) to have other legitimate, even if less prestigious, Haredi male identity options besides that of the full-time Avrech.

Presenting such challenges in public was hardly possible for mainstream Haredim before the formation of the extended peer-groups enabled by WhatsApp groups. Figure 3 is an excerpt from the group description of a large yet firmly vetted group of young working Haredi men (printed with the administrator’s permission on condition of masking the group’s name):

Figure 3.

Excerpt from a communal discussion group of young working Haredi men.

Although this is a group for Haredi men; i.e., men who are and wish to remain Haredi, they stress their dissatisfaction with how the current Haredi establishment treats working Haredi men.

The final quote is from a Haredi in his early fifties, who is both a working Haredi and an academic. While the previous example was from young Haredi men fighting for their place in Haredi society, this interviewee speaks as a father. He laments the hardships that his children have to endure for his life path. He states that he raises his sons to know they have more than one option:

“Regarding this [the working Haredi man’s identity], my children have quite a struggle… I am a working Haredi but I am pious and I want them to become fulltime Avrechim! However, if one of them is not a fulltime Avrech, he will [stresses] have an alternative, O.K.? Unlike other families, where there aren’t alternatives.”

Being a full-time Torah scholar is still the ultimate goal, but it is no longer the sole legitimate option. The strongest indicator for the durability of a new identity model is its transmission to the next generation. However, this new identity model does not supplant the first, but constitutes an acceptable alternative to the sanctified Haredi male identity.

9. Discussion

This study inquired how working Haredi men negotiate and crystallize their social identity by and through the use of WhatsApp groups. Identity was researched by exploring the key tenets of Haredi and online identity (conformism–agency; dogmatism–pragmatism; collective–individual orientations). The findings indicate that working Haredi men display a strong collective orientation towards the Haredi sector. They limit themselves to participation in Haredi groups and obtain their news from communal information sources. They ostensibly display conformism to the Haredi social order in terms of the content of online discourse (see Mishol-Shauli and Golan 2019), as well as when describing their offline experiences.

However, working Haredi men were also found to manifest considerable agency with regard to their smartphone and WhatsApp use in the communal and domestic spheres. When facing communal pressures, some ignore them, others curb their use to avoid public scrutiny and the rest develop a narrative that legitimizes their use as adhering to the communal. In the domestic sphere, households individually choose how to best educate their children regarding social networks and smartphone use.

In terms of the dogmatic–pragmatic identity axis, Haredi WhatsApp groups operate in what can be seen as a sphere of anomie and moratorium (Kahane 1997). In other words, there are still no clear rules within Haredi society concerning how much prominence and leeway are allowed for working Haredi men. Online, we found dogmatic messages, however, these were few, and were often resented, as group participants underlined the pragmatic nature of the WhatsApp leisure forums which undermine dogmatic discourse. Thus, dogmatism is curbed on WhatsApp groups, unlike the dogmatic nature of Haredi mass media.

Offline, working Haredi men find themselves torn between fulfilling their (and their nuclear families’) material individual needs, and vying to remain part-and-parcel of their pious community. As part of their belonging, they affirm their dogmatic allegiance to religious mores. However, they also express and promote pragmatism towards leveling the hierarchical order of the ‘the society of learners’ to approximate (though not eclipse) the status of working Haredi men to that of the full-time Avrech.

The creation of mediatized tracts for working Haredi men, tracts that do not host pious Avrechim, fosters the formation of exclusive spaces. These are demarcated spaces that only working Haredim may inhabit, starkly contrasting their de jure inferior status. Such unsupervised environments are unprecedented for Haredi men, and accordingly, they display a new type of discourse, which, in turn, fosters change in their participants’ identities. Furthermore, these informal tracts are also devoid of the pressures of the nuclear family and have thus become ‘third places’ in Oldenburg’s terms. Hence, they form a liminal online space for conducting open conversations with relative protection from the outside world. Within these spaces, offline status claims (e.g., age, sub-denomination), are checked at the door in order that “all within may be equals.” (Oldenburg 1989, p. 23). While Oldenburg describes third places as having a prevailing playful mood, Haredi participants choose to somewhat limit this playfulness to keep the atmosphere Haredi. Yet, playful use of Haredi codes is welcome, and in line with Oldenburg’s portrayal, the discourse is “largely unplanned, unscheduled, unorganized, and unstructured.” (Oldenburg 1989, p. 33), as sober and serious attitudes and conversations are infrequent and are usually ended quickly to make way for entertainment and wit. Another third place characteristic exhibited by Haredi WhatsApp groups is the maintenance of a low profile. However, while Oldenburg posits that third places maintain a low profile in order not to “attract a high volume of strangers” (Oldenburg 1989, p. 36), the working men in Haredi WhatsApp groups usually do so to avoid the scrutiny of Haredi leadership.

As stated above, the fulfillment of the ideal male identity is central to the existence of Haredi society. This results in Haredi men being under stricter supervision than women (Stadler 2009). Before the integration of WhatsApp, mostly women used social networks that were largely fully disclosed (albeit in vetted forums, see Lev On and Neriya-Ben Shahar 2012), while men participated only in anonymous online tracts (Okun and Nimrod 2017). Working Haredi men’s inferior status enables them to act in their newfound spaces relatively unhindered. They know that as long as they are not perceived as a threat to the Haredi social order, their relative freedom in these groups will prevail. Thus, overall, in the sphere of WhatsApp groups, users are granted a reprieve from the norms and rules that govern daily life. However, they choose to instill many ‘Haredi’ standards curtailing the moratorium imbued in the technology’s affordances, as it contrasts with the Haredi worldview.

10. Conclusions

This study points to a religious social shaping of technology use in which the religious leadership tries to circumscribe the effects of mediatization to the less prestigious social classes. Haredi leadership tries to keep the Haredi elite (and children) unaware of the social networks’ affordances to maintain the social order as well as preserve the purity of their pious class of learners from unwanted pollution of external knowledge sources.

As discussed above, even within the “mediatized zones”, participants shape their use of the platforms so as to greatly curtail realizations of online identity tenets. We saw how advertisements show no nuclear family groups. We also discussed how, although participating in unsupervised ‘third spaces’, users choose to enact either bonding ties or limit their bridging ties to other Haredim (compare with Norris 2002).

For religious communities, balancing modernity and traditional inclinations continues to feed their struggles to assert their religious identity amidst this duality. For secluded religious societies, as the case at hand, resistance to modernity is often part of their identity, making the balancing act ever more challenging. While the aspiration to improve their economic status is a recurring reason to break away from the full-time Avrech track, Haredi working men feel obliged to constantly proclaim their belonging to the Haredi ‘clan’. Thus, in their choice to participate in Haredi vocational groups, rather than in secular counterparts, they try to distance themselves from the modern connotations involved in joining the workforce, such as secularization.

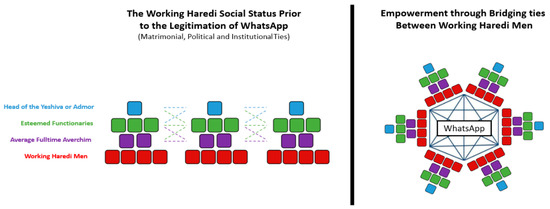

By carving spaces of their own, we posit that working Haredi men are empowered by the secluded spaces. In the past, Haredi working-men in each local community were isolated from fellow Haredi working-men. The new possibilities to form bridging ties under the umbrella of the Haredi sector enabled them to forge pan-Haredi peer-groups, develop trust-laden groups that facilitate social exchange and ultimately acquire group solidarity (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A Schematic Illustration of Haredi Working Men’s Empowerment.

This pattern of empowerment through secluded spaces for communication resonates with Fader (2020) in her analysis of the Haredi doubter movement in New York that thrives in online tracts.

Exploring online social networks that emerge within religious communities offers new avenues to explore the social formations and dynamics within these emergent structures. A group structure may spill over to become a primary or pressure group that coerces conformity to religious dogma and in effect grows into an extension of rabbinical authority. Alternatively, a group structure may evolve to form informal groups (Kahane 1997), that propel social change and engage with other communities. Thus, further exploration of these spaces will help shed light on the power of online social networks to either solidify boundaries between different collectives or serve as a mediating agency for the transfer of ideas between antagonized groups, religious or otherwise.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rel13111034/s1, Table S1: Interview Protocol; Table S2: WhatsApp Groups Coding Scheme.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M.-S. and O.G.; methodology, N.M.-S. and O.G.; formal analysis, N.M.-S.; investigation, N.M.-S.; resources, O.G.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M.-S. and O.G.; writing—review and editing, N.M.-S.; visualization, N.M.-S.; supervision, O.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university of Haifa (257/18; July 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Interviewees refused to sign a written informed consent so as not to have any material link to the research, regardless of specific citations. Expecting this, we obtained the university’s IRB permission to voice-record their informed consent. We keep the recordings on an encrypted external hard-disk.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Esther Singer for the language editing. The authors wish to thank Aref Badarne for his assistance in all stages of the manuscript’s preparations. Nakhi Mishol-Shauli’s work is supported by the President of the State of Israel’s Scholarship for Research Excellence and Innovation, and by the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture Scholarship for promising young researchers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Haredi society is characterized by a sharp division of gender roles, calling for the use of different theoretical framings in analyzing Haredi men and women. Therefore, social and anthropological research on the Haredim, especially qualitative research, is almost always “gender-segregated” (see Stadler 2009). |

References

- Askaria Surveys Company for the Haredi Society. 2020. Haredi Connectivity Patterns and Web Use During COVID. Israel: Bnei-Brak. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai-Nahon, Karine, and Gad Barzilai. 2005. Cultured technology: The internet and religious fundamentalism. Information Society 21: 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, Bruce J. 1986. Recent development in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology 12: 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Benjamin. 2017. The Haredim: A Guide to Their Beliefs and Sectors. Jerusalem: Am-Oved. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Cahaner, Lee. 2020. Ultra-Orthodox Society on the Axis between Conservatism and Modernity. Jerusalem: Israeli Democracy Institute. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2012. Understanding the Relationship between Religion Online and Offline in a Networked Society. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 80: 64–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2017. Surveying theoretical approaches within digital religion studies. New Media and Society 19: 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2020. Religion in Quarantine: The Future of Religion in a Post-Pandemic World. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Case, Judd. 2009. Sounds from the Center: Liriel’s Performance and Ritual Pilgrimage. Journal of Media and Religion 8: 209–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2011. The Power of Identity. New York: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Danesi, Marcel. 2017. Language, Society, and New Media: Sociolinguistics Today. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danet, Brenda. 2001. Cyberpl@y: Communicating Online. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Darwish, Abdel-Fattah E., and Günter L. Huber. 2010. Intercultural Education Individualism vs. Collectivism in Different Cultures: A cross-cultural study. Intercultural Education 14: 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotto, Carlotta, Rory Smith, and Claire Wardle. 2019. First Draft’s Essential Guide to: Closed Groups, Messaging Apps & Online Ads. Firstdraftnews.org. Available online: https://firstdraftnews.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Messaging_Apps_Digital_AW-1.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Fader, Ayala. 2020. Hidden Heretics: Jewish Doubt in the Digital Age. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Francesc-Xavier, Marin. 2015. Islam and Virtual Reality. How Muslims in Spain Live in the Cyberspace. In Negotiating Religious Visibility in Digital Media. Edited by Miriam Diez Bosch, Josep Lluis Mico and Josep Maria Carbonel. Barcelona: Blanquerna Universitat Ramon Llull, pp. 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Menachem. 1991. The Haredi (Ultra-Orthodox) Society-Sources, Trends and Processes. Jerusalem: The Jerusalem Institue For Israel Studies. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Golan, Oren, and Heidi A. Campbell. 2015. Strategic Management of Religious Websites: The Case of Israel’s Orthodox Communities. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20: 467–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, Oren, and Eldar Fehl. 2020. Legitimizing academic knowledge in religious bounded communities: Jewish ultra-orthodox students in Israeli higher education. International Journal of Educational Research 102: 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, Oren, and Michele Martini. 2019. Religious live-streaming: Constructing the authentic in real time. Information, Communication & Society 22: 437–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, Oren, and Nakhi Mishol-Shauli. 2018. Fundamentalist web journalism: Walking a fine line between religious ultra-Orthodoxy and the new media ethos. European Journal of Communication 33: 304–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, Samuel C. 1995. The vision from the Madrasa and Bes Medrash: Some Parallels between Islam and Judaism. In Fundamentalisms Comprehended. Chicago: Chicago University Press, pp. 71–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Stewart M., Echchaibi Nabil, and M. Marty. 2014. Media Theory and the “Third Spaces of Digital Religion”. Research Methods and Theories in Digital Religion Studies 3: 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hymes, Dell. 1974. Foundations in Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahane, Reuven. 1997. The Origins of Postmodern Youth: Informal Youth Movements in a Comparative Perspective. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katriel, Tamar. 2004. Dialogic Moments: From Soul Talks to Talk Radio in Israeli Culture. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katzir, Shai, and Lotem Perry-Hazan. 2019. Legitimizing public schooling and innovative education policies in strict religious communities: The story of the new Haredi public education stream in Israel. Journal of Education Policy 34: 215–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusow, Abdi M. 2003. Beyond Indigenous Authenticity: Reflections on the Insider/Outsider Debate in Immigration Research. Symbolic Interaction 26: 591–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, David, and Batia Siebzehner. 2009. Power, Boundaries and Institutions: Marriage in Ultra-Orthodox Judaism. European Journal of Sociology/Archives Européennes de Sociologie 50: 273–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev On, Azi, and Rivka Neriya-Ben Shahar. 2012. To browse, or not to browse? Third-person effect among ultra-Orthodox Jewish women, in regards to the perceived danger of the Internet. In New Media and International Communication. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, pp. 223–36. [Google Scholar]

- Marty, Martin E., and Scott R. Appleby, eds. 1991. Introduction. In Fundamentalism Observed. Chicago: Chicago University Press, pp. vii–xiv. [Google Scholar]

- Mishol-Shauli, Nakhi, and Oren Golan. 2019. Mediatizing the Holy Community-Ultra-Orthodoxy Negotiation and Presentation on Public Social-Media. Religions 10: 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neriya-Ben Shahar, Rivka. 2020. “Mobile internet is worse than the internet; it can destroy our community”: Old Order Amish and Ultra-Orthodox Jewish women’s responses to cellphone and smartphone use. Information Society 36: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolt, Steven M. 2016. The Amish: A Concise Introduction. Baltimore: John Hopkins UP. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Pippa. 2002. The Bridging and Bonding Role of Online Communities. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 7: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okun, Sarit, and Galit Nimrod. 2017. Online Ultra-Orthodox Religious Communities as a Third Space: A Netnographic Study. International Journal of Communication 11: 2825–41. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, Ray. 1989. The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Community Centers, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars, Hangouts, and How They Get You through the Day. Minnesota: Paragon House Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Rainie, Harrison, and Barry Wellman. 2012. Networked: The New Social Operating System. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rokeach, Milton. 1954. The Nature and Meaning of Dogmatism. Psychological Review 61: 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, Hananel, and Menahem Blondheim. 2021. The smartphone and its punishment: Social distancing of cellular transgressors in ultra-Orthodox Jewish society, from 2G to the Corona pandemic. Technology in Society 66: 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schejter, Amit M., and Noam Tirosh. 2016. A Justice-Based Approach for New Media Policy: In the Paths of Righteousness. New York: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Stadler, Nurit. 2009. Yeshiva Fundamentalism: Piety, Gender, and Resistance in the Ultra-Orthodox World. New York: University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryker, Sheldon. 2007. Identity Theory and Personality Theory: Mutual Relevance. Journal of Personality 75: 1083–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindell, Dorothy H., and Luciano L’Abate. 1970. Religiosity, dogmatism, and repression-sensitization. Scientific Study of Religion 9: 249–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmud, Ilan, and Gustavo Mesch. 2020. Wired Youth: The Online Social World of Adolescence. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tavory, Iddo. 2016. Summoned: Identification and Religious Life in a Jewish Neighborhood. Chicago: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turkle, Sherry. 1995. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Bryan S. 2007. Religious Authority and the New Media. Theory, Culture & Society 24: 117–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, Teun Adrianus. 1993. Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society 4: 249–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zelenkauskaite, Asta, and Amy L. Gonzales. 2017. Non-Standard Typography Use Over Time: Signs of a Lack of Literacy or Symbolic Capital? The Journal of Community Informatics 13: 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoldan, D. 2019. The New Haredim. Modiin: Dvir Publishing. Zmora: Kineret. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).