Abstract

Tejaprabhā Buddha is the lord of the constellations and one of the most significant esoteric deities. Its image occurs in a number of Chinese visual presentations dating from the Tang Dynasty to the Ming Dynasty. The cult of Tejaprabhā was also disseminated to Korea and Japan and spawned related local visual creations. Tejaprabhā Buddha and his followers do not belong to the core group of Buddhist deities but are instead connected to the Daoist deities. This was most likely due to the fact that asterism held a greater significance to Daoists, for whom it was the most important of all the power sources derived from the cosmos. The focus of this study is on unearthing the Daoist astrological influences in the visual presentation and its adaptation of Tejaprabhā Buddha and the accompanied luminary deities in China. The cult of constellations and Tejaprabhā in the context of Chinese Esoteric Buddhism was constantly evolving under the influence of Daoism, gleaned by examining and comparing the quantity and visual variations of luminaries in the artworks of Tejaprabhā of different periods.

1. Introduction

Tejaprabhā Buddha (Ch. Chishengguang fo 熾盛光佛), translated by Anglophone scholars as the Buddha of Blazing Light or Effulgent Buddha, is characterized by modern scholars as a deified incantation. In the perspective of Buddhist planetary worship, he is the lord of the constellations and one of the most significant esoteric deities (Sørensen 2011, p. 94). Tejaprabhā occurs in several scriptures, such as the Beidou qixing humofa 北斗七星護摩法 (Method of Performing the Homo Ritual for the Seven Stars of the Great Dipper),1 embedded in which is the Chishengguang Yaofa 熾盛光要法 (Essential Method of Tejaprabhā), and the Da weide chishengguang rulai jixiang tuoluoni jing 大威德熾盛光如來吉祥陀羅尼經 (Great Majestic and Virtuous Tejaprabhā Tathagata Good Fortune Dhāraṇī Sūtra) translated by Amoghavajra. Da weide Chishengguang rulai jixiang tuoluoni jing appears to have been the primary scriptures of the Tejaprabhā cult (Sørensen 2011, p. 240).

The existing visual representations of the Tejaprabhā Buddha date from the Tang Dynasty and conclude with the Ming Dynasty. Dazhengzang 大正藏 (Dazheng Buddhist Scriptures) describes the figure of Tejaprabhā as “head wearing the hat with the images of five Buddhas, two-handed gesture resembling Śākyamuni,”2 which indicates that Tejaprabhā possesses some of the ritual appearances of Śākyamuni. In Dasheng miao jixiang pusa shuo chuzai jiaoling falun 大聖妙吉祥菩薩說除災教令法輪 (Great and Holy Bodhisattva Śrī Lakṣmī Discourses on the Teaching for the Removal of Calamities by Turning the Dharma Wheel), the Tejaprabhā is depicted in great detail as holding a golden wheel with eight spokes, seated on a lion, surrounded by a thousand beams of light, and with an umbrella hanging above his head. In traditional Chinese Buddhist wall paintings, Tejaprabhā is often depicted with various deities of constellations and zodiac. There are a total of about 19 existing visual images of Tejaprabhā now, including silk paintings, paper paintings, sculptures, stone carvings, and wood prints. These works are scattered in the Turpan region, Dunhuang region, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Shanxi, Chongqing, Hangzhou, and Nara Japan (Wang 2020, pp. 123–24).

A late addition to the pantheon of Esoteric deities, Tejaprabhā is documented as having made its first appearance in the visual arts by Wu Daozi 吳道子 during the middle of the Tang Dynasty in China, according to Xuanhe Huapu 宣和畫譜 (Catalog of Paintings of the Xuanhe Emperor) (Xia and Shen 2019, p. 87). Later in the Song Dynasty, Nansong guangelu xulu 南宋館閣錄續錄 (Southern Song guange continued records) also documented the process by which Sun Wei 孫位 and Zhu Yao 朱繇 producing the image of Tejaprabhā (Xia and Shen 2019, p. 88). Although initially, Tejaprabhā Buddha merely possessed radiance or golden wheel attributes, he evolved in Tang times into a radiant Buddha who assumed the role of his traditional Daoist counterpart, the Great Thearch of Purple Tenuity of the North Pole (Ch. Ziwei beiji dadi 紫微北極大帝) and ruling the constellations of the celestial dome (Little and Eichman 2000, p. 25).

Although the cult of Tejaprabhā broadly existed in China and Inner Asia, its pictorial corpus is rather small. It comprises for this period—its most active one—less than one hundred extant visual works (McCoy 2017, p. 4). The existing images of Tejaprabhā can be broadly categorized into three paradigms. The first one is the image of Tejaprabhā in a bullock cart, which was primarily seen in the late Tang and early Song dynasties. The typical composition depicts Tejaprabhā seated on a lotus seat in a bullock cart without holding an instrument, with one hand performing the mudra of meditation and the other the mudra of teaching. The cart is adorned with precious umbrellas and flags, some offerings are placed on a square table in front of the cart bed, and five deities of luminaries are arranged around the cart while holding a variety of colored instruments in their hands. In those works, Tejaprabhā and the luminaries are of the same size. The second type of image is Tejaprabhā in meditation and preaching. The majority of surviving works were created during the Xixia 西夏, Liao 辽 and Yuan Dynasty, during which Tejaprabhā was surrounded by luminaries. The body of Tejaprabhā was usually deliberately enlarged, occupying a more significant portion of the scene than that of other deities. These two paradigmatic works were painted on portable materials such as silk and cloth, making it easier for the worshippers to carry and make offerings at any time and place. The third paradigm of visual work is the “Three Buddha Statues” (Ch. Fo sanzung 佛三尊), which depicts Tejaprabhā in the center flanked by two Bodhisattvas on either side in attendance. Eight other Bodhisattvas are interspersed among the three principal figures, while the remaining deities are encircled on the outside. The phrase “Three Buddha Statues” was painted on temple walls. Tejaprabhā, in this paradigm, acts as the guardian of the region. To create a compelling religious environment for the worshippers and allow them to immerse themself in the situation, the figures were purposefully drawn to life-size (Wang 2020, pp. 123–24; Meng 1998, pp. 34–39).

The artists responsible for the visual representations of Tejaprabhā were erudite in Daoist teachings. For example, Sun Zhiwei 孫知微 (976–1022) of the Song dynasty is recorded as being “very cultured in Daoist practice, good at both Buddhist and Daoist paintings.”3 On the wall of Chengdu Shouning Yuan 成都壽寧院 (Chengdu Shouning cloister), Sun painted Tejaprabhā Buddha with nine luminaries, which was admired by his contemporaries (Huang 2014, p. 245). The focus of this study is on unearthing the Daoist impact, particularly astrological influences, in the visual representation of Tejaprabhā Buddha in China since the Tang period.

2. The Worship of the Northern Dipper in Buddhism and Daoism

The figurative representation and iconography of Tejaprabhā must have derived from those of the Chinese Northern Dipper (Ch. Beidou 北斗) (Jing 2002, p. 215).4 The Chinese Celestial Master (Ch. Tianshidao 天師道) Daoists had already developed a functional and sophisticated astrological system in place when Buddhism, which brought with it Indian astrology and astronomical observations, came to China around the first and second centuries C.E (Sørensen 2011, p. 231). This indigenous system comprised not only significant portions of China’s traditional sciences but also compelling components of its philosophical systems, such as the tradition of Yin and Yang and the five elements, which are tied to the five fundamental stars: Saturn, Venus, Jupiter, Mercury, and Mars (Sørensen 2011, p. 231).

In ancient China, the Northern Dipper was considered as both the controller of the stars in the heavens and of humans on earth. Establishing a celestial pantheon in Chinese Buddhism was necessary because of the importance of astronomy in religious, political, social, and economic life, as well as in state affairs in ancient China.

It appears that the devotion of the Northern Dipper within the Buddhist framework dates to the early Tang Dynasty. The Chinese Buddhist monk-astronomers first adhered to the Chinese celestial pantheon in Daoism and worshipped the Northern Dipper as a supreme celestial monarch, who was later replaced by Tejaprabhā Buddha in the Buddhist context. This can be proved from a Buddhist text, The Hora of Brahma and the Nine Luminaries,5 where a passage entitled “the Daoist Immortal Ge Hong’s method of worshipping the Northern Dipper” imparted that all human beings, regardless of their social status, are dominated by the seven stars of the Northern Dipper.6 In order to escape calamities, one should worship the Northern Dipper (Jing 2002, p. 215). The cult of Northern Dipper proves Buddhism’s debts to Daoist astral worship and the medieval Buddhist-Daoist interaction. It is not easy to distinguish the Buddhist approach to individuals’ fate from the Daoist one (McCoy 2017, p. 41).

Although Buddhist divinities were transplanted on top of Daoist ones, the essence of the ritual remained the same. A Daoist-only literature Taishang xuanling Beidou benming yansheng zhenjing 太上玄靈北斗本命延生真經 (True Scripture on the Highest, Abstruse Spiritual, Northern Dipper’s Fundamental Extension of Life) resurfaced in the Buddhist framework as an authoritative treatise on the worship of the Northern Dipper (Sørensen 2011, p. 237). The inclusion of Daoist teaching in this Buddhist treatise is an apparent effort to subject the Nine Luminaries to the hierarchy of the Northern Dipper (Jing 2002, p. 215).

The cult of Tejaprabhā was inextricably linked to astrology. In the later Tang Dynasty, the cult was mainly used to dispel misfortune brought by malevolent stars. From the mid-Tang period onwards, Chinese people used astrology to predict their longevity and good fortune. People checked the position of the stars in Futianli 符天曆 (Futian Calendar), and it was believed that a person’s fate is determined by the position of the nine or eleven luminaries in the zodiac at the time of birth. The religion of Tejaprabhā is one of several ways created by the Tantra to eradicate the influence of malevolent stars. To prevent calamities, people chanted incantation (Skt. dhāraṇī; Ch. tuoluoni 陀羅尼) and established Tejaprabhā Bodhimaṇḍa (Ch. daochang 道場). The earliest example of this cult could be found in Da weide Chishengguang rulai jixiang tuoluoni jing, which is now in the Gansu Province Museum collection. This sūtra claims that it can “remove all the 80,000 inauspicious things in the world, and can accomplish 80,000 great auspicious things” (Duan 1999, p. 142).

3. British Museum, Painted Banner, Dated 897

The painting from Dunhuang Mogao Caves Cave 17 now in the British Museum is the oldest of the preserved Tejaprabhā paintings, and the prototypical work belongs to the first visual paradigm of Tejaprabhā on a bullock cart (Figure 1). The Tejaprabhā Buddha is represented as a celestial king, seated atop an ox-drawn cart and attended to by a cosmic retinue consisting of five planets, each of which is depicted with the characteristics that are associated with that planet (Jing 2002, p. 215). Proceeding from the left clockwise, we see five luminaries as Jupiter, Mercury, Mars, Venus, and Saturn in order (see Figure 2). The Fantian huoluo jiuyao 梵天火羅九曜 (Indian Astrology of the Nine Luminous Bodies) describes the figures of those five luminaries as below:

| Five Luminaries | Figures7 |

| Jupiter | “The form of the deity is like that of a minister. He wears a blue garment and a boar hat. In his hand(s) he holds flowers and fruits.”8 |

| Mercury | “The deity’s form is that of a lady. Atop her head she wears a monkey hat. In her hand she holds a paper and brush.”9 |

| Mars | “The figure of the deity is like that of the heterodox, wearing a donkey hat atop the head with his four hands holding weapons and blades.”10 |

| Venus | “A form is like that of a lady. Atop the head she wears a fowl hat. White silk garment. Plucking strings.”11 |

| Saturn | “A form like a Brahmin. Ox cap on the head. His hand holding a monk’s staff.”12 |

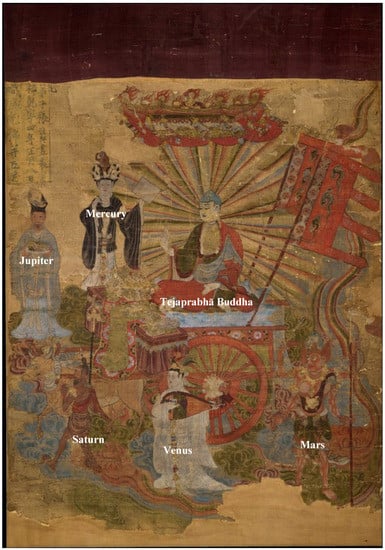

Figure 1.

Chisheng guangfo yu wuxingsheng 熾盛光佛與五星神 (Tejaprabhā Buddha and Five Deities of Stars), British Museum, Ink and colors on silk, From Cave 17, Dunhuang Mogao Caves, 80.40 cm × 55.40 cm, Dated 897.

Figure 2.

Iconographical annotation of Figure 1.

Compare the text with the picture; it is easy to find that the personified figures of the five luminaries are strictly following the description in the Fantian huoluo jiuyao.

In the course of the development of Buddhism, the five luminaries were eventually given human form (Sørensen 2011, p. 234). Their images include a few icons strongly suggestive of an “Iranian-Mesopotamian” origin which themself draw on an earlier Greco-Egyptian tradition (Kotyk 2017, pp. 33–88). The personification of the asterisms in China might happen in the latter half of the Southern and Northern Dynasties (386–581), for by the time of the Tang Dynasty, several bodhisattvas, many of which prestigious on their own merits, appeared in the roles as celestial bodhisattvas, including Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī (Ch. Wenshu 文殊) (Sørensen 2011, p. 234). The Tejaprabhā Buddha kept a close relationship with Mañjuśrī. According to the Buddha’s Sūtra, Buddha preached to Manjushri and the other deities. It is written in the Daweide jinlun foding chishengguang rulai xiaochu yiqie zainan tuoluoni jing 大威德金輪佛頂熾盛光如來消除一切災難陀羅尼經 (Tejaprabhā Buddha Sūtra for the Elimination of All Calamities):

“Then Śākyamuni Buddha, dwelling in the Pure Abode of Heaven, told Mañjuśrī Bodhisattva Mahāsattva, and Mañjuśrī’s four multitudes, the eight divisions, the great heavenly bodies, the nine deities, the seven luminaries, the twelve palace deities, the twenty-eight stars, and the sun and the moon.”13

As a result, it is possible that the personification of luminaries in China happened at the same historical period. According to the British Museum, the vessels displayed on the altar before the cart were drawn in ink and originally richly gilded. Gilding was initially applied to the Tejaprabhā Buddha’s exposed facial features and other visible regions of his body. The Buddha’s face, which is significantly darker than the other figures, shows strong traces of restored gilding and repainted ink lines. It is believed that the distinct hook of the Buddha’s redrawn mouth-line reflects a trend from the first half of the tenth century, in contrast to the mouth-lines of the other figures, which are straight and end in a slight swelling, thus dating the restoration of this painting to the first half of the tenth century.14 Although the Da weide Chishengguang rulai jixiang tuoluoni jing, translated during the Tang dynasty, mentioned Nine Luminaries at the end of its volume, the visual representation of the Tejaprabhā Buddha in Tang has been limited to Five Luminaries.

4. Musée Guimet, Painted Banner

Another Dunhuang painting of Tejaprabhā Buddha in the Musée Guimet includes five normal luminaries and two new luminaries Rāhu (Ch. Luohou 羅睺) and Ketu (Ch. Jidu 計都), who hailed from Indian astrology (Figure 3). It is another work that represents the scene of Tejaprabhā on a bullock cart. The Guimet painting shows three roundels—two above and one below—each displaying a menacing, monstrous face with a gaping mouth.

Figure 3.

Tejaprabhā procession, ca. 10th century, ink and colors on paper. 30.5 cm × 76.4 cm, Mogao cave 17, Dunhuang, China, now Bibliothèque nationale de France. Pelliot chinois 3995, gallica.bnf.fr.

Rāhu and Ketu are invisible planets representing ascending and descending lunar nodes. They are two imaginary constructs devised to explain lunar eclipses. Their addition expanded the traditional Chinese cast of the Five Luminaries (Ch. wuyao 五曜) to the new set of Seven Luminaries (Ch. qiyao 七曜).

Rāhu is a demigod who is said to have stolen the elixir of immortality, reserved for celestials. Alerted by the sun and moon gods, Viṣṇu chopped off his head. However, the heavenly elixir that he had drunk gave him immortality. He had become vengeful and started devouring the sun and moon. However, due to Rāhu’s existence only as a severed head, the sun and moon could escape from his broken neck and return to the sky. Rāhu’s bodily remains, on the other hand, turned into Ketu, a comet (Hartner 1938, pp. 112–54). Rāhu and Ketu, together with Mars (Ch. huoyao 火曜) and Saturn (Ch. tuyao 土曜), came to make up the “Four Evil Luminaries” in heaven. This dramatic scenario explains the painting in Guimet. The monstrous head on the top right is Ketu, as the nine serpentine heads rearing up from his scalp are among his known attributes.

Rāhu was depicted as a disembodied head in Indian and Central Asian art. Ketu later appeared as the snake-like tail to Rāhu’s upper torso and head. In Chinese art, the head-tail distinction was not observed. Rāhu and Ketu were conceived as a complementary pair of the sun head and the moon head in the Chinese Tejaprabhā visual culture. In this Dunhuang painting, the green demon in the red disk should be Rāhu and the other one is Ketu according to Qiyao rangzai jue 七曜攘灾决 (Avoiding Misfortune Caused by the Seven Planets) (McCoy 2017, pp. 65–66).

The change from five luminaries to seven is not just in number but also in the nature of their celestial makeup. The heavenly itinerary of the luminaries, particularly that of the “evil luminaries,” remained a constant source of anxiety in the medieval Chinese mind. This relates to the traditional projection of human affairs onto the heavenly field and the growing sense of correlation between one’s earthly life and its astral doppelganger in the sky.

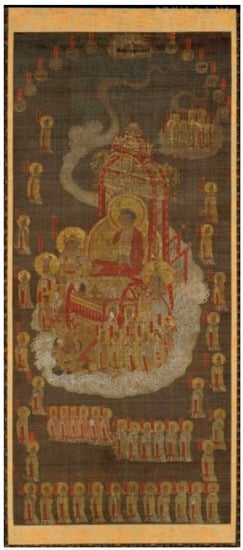

5. Tejaprabhā Buddha Subduing the Nine Luminaries—Liao Period, ca. 1000

The hand-colored woodblock print of Liao 遼 in Figure 4 belongs to the second paradigm: Tejaprabhā in meditation and preaching. In the composition, the addition of the sun and moon are made to the celestial pantheon cast, evolving from the set of seven luminaries to Nine Luminaries (Ch. jiuyao 九曜). Not only does the number of luminaries change, but the format for depicting Tejaprabhā Buddha changes too. He is no longer seated on a bullock cart, proceeding with his entourage, but sitting on a lotus throne surrounded by deities, holding a golden wheel. Another significant change is the image of Saturn. In the British Museum Tejaprabhā painting, Saturn was an elderly Brahmin with a bull’s headdress and a dark physique (Figure 2). However, in Figure 4, Saturn shows a pronounced degree of sinicization of the long gown draping the ground, which resembles the goddess on the right. The female deity may have been developed with symmetry in mind (Ouyang and Gao 2022, p. 71).

Figure 4.

Chishengguang jiuyaotu 熾盛光九曜圖 (Tejaprabhā Buddha Subduing the Nine Luminaries), Historical Relics Preservation Institute of Yingxian Wooden Pagoda 应县木塔文保所, Hand-colored woodblock print, 50 cm × 94.6 cm, Liao period, ca. 1000.

The upper part of the print is damaged, but two zodiac signs remain to the right of the Buddha’s halo and two to the left. Fragments of two further zodiac signs flank each side of the title cartouche. The upper part of the print, including the upper part of the cartouche, is missing but in the upper right and left corners, the swirls of clouds contained at least three standing figures each.15

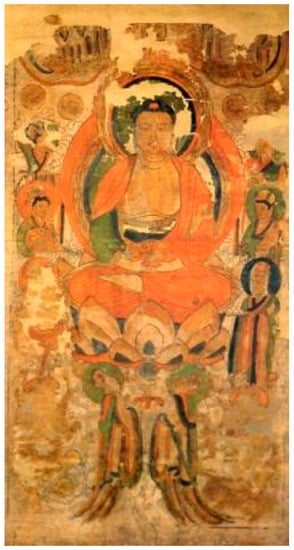

The Indian zodiac was first introduced to China around the Southern and Northern Dynasties.16 During the middle of the Tang period, this custom may have supplanted the conventional zodiac. The Chinese and Western zodiac system differs mainly as the Chinese correspond to years rather than months (Xia 1976, pp. 35–58). However, the new zodiac never grew sufficiently prominent to supersede the ancient one, and the artwork had examples of both systems coexisting side by side (Sørensen 2011, p. 232). In some Chinese paintings of Tejaprabhā, the Chinese and the western ones are mixed. This diverse representation of the Chinese and Western zodiac is even represented in a 14th-century Korean painting of Tejaprabhā Buddha (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Chixingguang rulai wanglintu 熾星光如來往臨圖 (The Descent of Tejaprabhā Buddha), MFA, Boston, Ink, colors, and gold on silk, 124.4 cm × 54.8 cm, Late 14th century (Korean Goryeo Dynasty).

The print shows the Nine Luminaries in the anthropomorphic form: at the viewer’s right of the Buddha, the Sun Bodhisattva, Mercury, and Jupiter; at the viewer’s left, the Moon Bodhisattva, Venus, and Mars. In the center, in front of the Buddha’s throne, is Saturn on the viewer’s right and a crowned female opposite, possibly Dimu, the Earth Mother. Flanking these two are the malign luminaries: Rāhu (lower right) and Ketu (lower left).

The shifting alignments of one’s “original-life chamber” with the entry of particular members of the Nine Luminaries (the Sun, Moon, Venus, Jupiter, Mercury, Mars, Saturn, Rāhu, and Ketu) are perceived as “visits” or “invasions” depending on their perceived disposition, could cause serious concern.

Before the inclusion of Rāhu and Ketu, when the planetary cast consisted only of the Five Luminaries, the concern was more with the proper alignment among the five. With the addition of two vengeful members to the cast, the planetary constitution became a more clear-cut, intelligible, melodramatic affair. Some accounts pitch the five good planets (the Sun, Moon, Jupiter, Venus, and Mercury) against the four malign ones (Mars, Saturn, Rāhu, Ketu). Other, more popular accounts in circulation posit an extended list of six evil luminaries, including Mercury and Venus, Mars, Saturn, Rāhu, and Ketu. The invisible Rāhu and Ketu are known to be capable of “sneaking into human beings’ original-life chamber.”17 It follows, therefore, that the invasions of the unruly planets into one’s “original-life chamber,” or other Jupiter-stations correlated with various important human affairs, are cause for grave concern. If the sun, moon, and the good luminaries lose out to the evil ones in the sky, then chaos and disasters will probably ensue on earth. Because of the importance the asterisms and planets had in the lives of medieval Chinese people, it’s possible that the ideas of longevity, wealth, and good health were inextricably linked with the worship of the celestial bodies (Sørensen 2011, p. 230).

In this case, the presence of Tejaprabhā Buddha is significant. According to Da weide Chishengguang rulai jixiang tuoluoni jing, Śākyamuni preaches to the space-traveling beings, the nine luminaries, the twenty-eight constellations,18 the twelve solar deities, and all of the other sages. In the course of his teaching, he advises kings and ministers whose countries are threatened to chant the Tejaprabhā dhāraṇī, thereby avoiding calamities. Tejaprabhā would not only assist in annihilating the threat but also pass it on to their enemies: “If Mars is causing calamities at state borders or causing obstacles, vehemently chant this dhāraṇī sūtra. Calamities will be transferred to disobedient kings and rebellious people.”19 In another Tejaprabhā sūtra, the practice of the rites is recommended for not only monarchs but also commoners, who may also suffer from oppression by the sun, moon, five planets, Rāhu, Ket, comets, and malign stars (Gridley 1998, p. 7).

Tejaprabhā Buddha is the focus of rituals performed to counter malign stellar influences. It was, then, necessary in those times to practice spell-craft. One is instructed to pose with specific mudras and recite specific mantras. To assist further the colossal battle between the planetary luminaries in one’s zodiac counterpart, it is advisable to set up ritual enclosures for the liturgies of Tejaprabhā Buddha. We are thus reminded of the Daoist practice of imaginary levitation in relation to asterisms. It begins with a meditation on the constellations, which are believed to correspond to one’s inner viscera. By internalizing the astral images, the practitioner feels himself levitating, either riding or treading the stars and spiraling upwards. In an ecstasy of flight, one gets to “ride the dragon” to reach the Purple Enclosure (the celestial sphere around the North Star), where one meets the Purple Thearch and obtains the Yinshu 隱書 (Cryptic Script) that allows one to roam with total freedom in heaven (Wang 2011, p. 154).

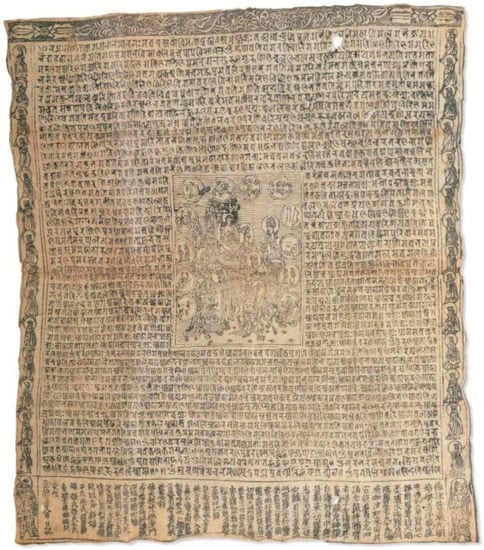

6. Ruiguangsi 1005 CE Print: Planetary Roadmap (Figure 6)

The Ruiguangsi 瑞光寺 (Ruiguang monastery) print is another work of Tejaprabhā on a bullock cart. The spell center is a rectangular frame showing a celestial scene in this print. The Tejaprabhā Buddha is seated on an oxcart, touring the celestial sphere with an entourage of nine luminaries: the Sun, Moon, Venus, Jupiter, Mercury, Mars, Saturn, Rāhu, and Ketu. The Nine Luminaries gradually replaced the five-luminary set in Tang and Song esoteric Buddhism. Du Guangting 杜光庭 (850–933), a famous late Tang Daoist priest, in his Lidai chongdao ji 歷代崇道記 (Records of Worshipping Taoism in the Past Dynasties), documented more than 10 poems of the Nine Luminaries, but only one of the Five Luminaries set (Du 1985). The twelve zodiac signs, introduced in China in the sixth century or earlier, are arranged in random order. A central pictorial scene is inserted into a field of arrays of Sanskrit letters.

Figure 6.

Dasuiqiu tuoluoni jing 大隨求陀羅尼經 (Tejaprabhā sutra) arranged in Sanskrit letters. Formerly sealed inside Ruiguangsi pagoda crypt, now collection of Suzhou Museum, China. Woodblock print, 25 cm × 21.2 cm, Dated 1005.

The traditional twenty-eight constellations flank the text. In the course of a month, the moon traversed a total of twenty-eight different constellations, which may be thought of as distinct regions in space. Compared to the more giant five planets—Mars, Venus, Saturn, Jupiter, and Mercury—these twenty-eight constellations are sometimes known as the lesser motions in the sky. Nevertheless, the effects of the twenty-eight constellations’ influencing energies could be sensed on a far more pronounced level in the world of people. (Sørensen 2011, p. 230).

The Tejaprabhā Buddha occupies the inner precinct with the Nine Luminaries, who appear to proceed in an orderly fashion within the domain of twelve zodiac signs. The twenty-eight constellations, shown as respectful officials, flank the symbolic ritual enclosure.

The Nine Luminaries also found their way to Japan, which can be witnessed in a 13–14th century Tejaprabhā Mandala painting (see Figure 7) in Japan. The five essential stars surround the Tejaprabhā Buddha in the middle when Sun and Moon occupy the left and right corners on top of the painting. Rāhu and Ketu are placed outside the circle of twelve zodiac and twenty-eight constellations in the lower part of the painting (see Figure 8). The extant Tejaprabhā Buddha paintings in Japan usually avoid the repetitive nature of Japanese astral Mandalas and circumvent the standardization of the subject in Yuan and Ming China. However, most of the Japanese Tejaprabhā paintings are based on a Tang dynasty print of the Northern Dipper Mandala (Tangben beidou mantuoluo 唐本北斗曼陀羅) (see Figure 9) transmitted to Japan in the early on. Its bearing can even be traced into 14th-century Japanese Tejaprabhā paintings, with new elements added to them. Moreover, in Japan, the iconography of Tejaprabhā Buddha is closely associated with Bhaiṣajyaguru (Jp. Yakushi Nyorai 薬師如来) (Su 2011, pp. 109–36). In a line drawing of 1164 (see Figure 10), the Tejaprabhā Buddha is holding a bowl in his left hand, stepping on two loti. This sort of attribution is usually attributed to Bhaiṣajyaguru instead of Tejaprabhā. Baibao kouchao 白寶口抄 even documented that Bhaiṣajyaguru and Tejaprabhā are interchangeable according to Qifo Yaoshi chao 七佛藥師抄.

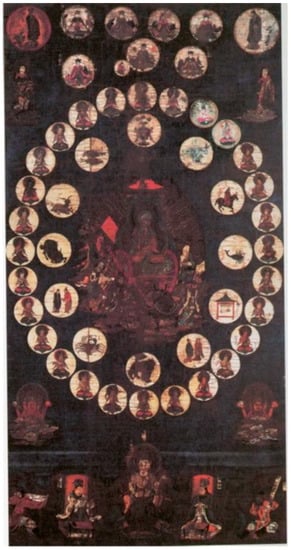

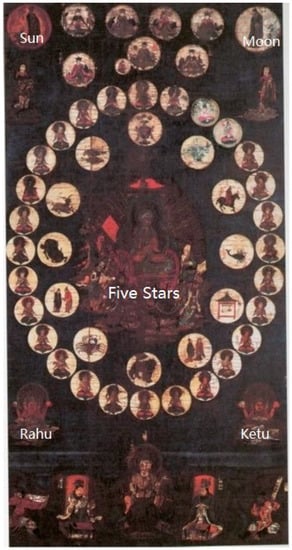

Figure 7.

Tejaprabhā Buddha Mandala, Sakai-Shi, Japan, Color on Silk, 102.2 cm × 61.3 cm, Kamakura Jidai (13th–14th century).

Figure 8.

Iconographical identification of Figure 7.

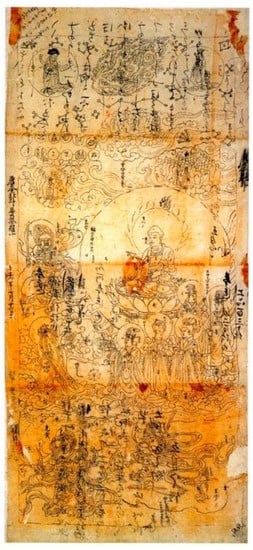

Figure 9.

Tangben beidou mantuluo zhiben mohua 唐本北斗曼荼羅紙本墨畫 (Tang Dynasty Ink Painting on paper of the Mandala of the Northern Dipper), The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts, 111.5 cm × 51.5 cm, 1148.

Figure 10.

Images of Nine Luminaries (Tejaprabhā Buddha), MOA Museum of Art, Ink on paper, 353.6 × 28.8 cm, 1164.

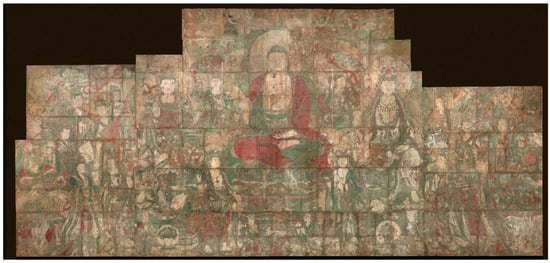

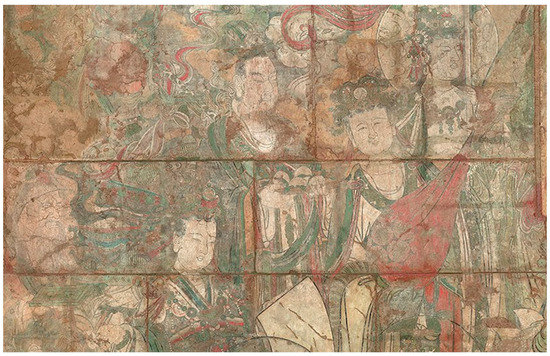

Up to this point, the pictorial framework has elevated Tejaprabhā Buddha to an even more aggrandized role. Daoist deities in attendance on a Buddha are especially appropriate at Guangshengsi 廣勝寺 (Monastry of Vast Triumph), where the Lower Monastery of Guangshengsi includes a Daoist compound. It is a typical “Three Buddha Statues.”

The Sun Bodhisattva is to the viewer’s right of the Buddha and the Moon to the left; each is seated in a lalitāsana posture, a posture in which one leg is pendant and which is usually adopted as subordination to the central, principal figure who is sitting in a virasana posture (see Figure 11). On the mural, the Sun and Moon bodhisattvas are slightly smaller than the central Tejaprabhā Buddha but more significant than the other figures, forming with the Tejaprabhā Buddha a central triad. The five planets have been consigned to the upper left corner: Venus plays a pipa; Mercury inscribes a sheet of paper in a monkey-shaped headdress; Jupiter bears a tray of peaches, with a headdress centering on a fine boar’s head; while Saturn, at the far left, is an older man wearing a cowl and holding a book (see Figure 12).

Figure 11.

The Assembly of Tejaprabhā, The Nelson-Atkins Museum, Ink and mineral colors on clay, From Guangsheng Lower Monastery (Ch. Guangsheng xia si 廣勝下寺), Shanxi Province, China, 713.74 cm × 1483.36 cm, Early the 14th century.

Figure 12.

Upper left corner of The Assembly of Tejaprabhā (detail).

Above this group stands Mars, his face obliterated through lost paint, but his horse headdress, armored upper torso, and raised powerful left arm remain to document his presence. In the corresponding location opposite, i.e., in the upper right corner, Ketu, with a green face and fangs, holds the head of a hapless victim in a bag; Rāhu, equally horrific with his bulging eyes, distorted forehead, and green face, is slightly above and to the left of Ketu.

Below Rāhu stands Yuebei 月孛, who raises his sword in salute to the Buddha and Ziqi, who holds his jade tablet,20 both decorously calm in their Chinese robes. Although Rāhu and Ketu are of Indian origin, Ziqi 紫氣 and Yuebei have their roots in Chinese literature and beliefs. Although in the Buddhist context, Yuebei is usually depicted as a comet with scattered long hair and holding a sword, in the Daoist context, Yuebei is a deity of thunder, and usually his surname is Zhu 朱, deviating from the eleven luminary system to be called “Taiyi 太一(乙).” Yuebei can even be a female deity in the Daoist context, which was also adopted in the depiction of Tejaprabhā Buddha. Furthermore, Ziqi is mainly associated with Daoism. Ziqi is a portent of the appearance of emperors, sages, or treasure. When Laozi was traveling west, for instance, the guard at the gate saw Ziqi floating above just before Laozi’s arrival, riding a green ox, on his way west.21 According to Gridley, Ziqi here is especially associated with Khubilai and, in this mural exalting Kubilai22, Ziqi is especially meaningful, for Ziqi not only predicted the appearance of an emperor but was also a champion of the Daoist cause.

The sūtra related to Tejaprabhā Buddha never mentions the two other stars, Ziqi and Yuebei. However, Ziqi and Yuebei are mentioned in a Daoist text entitled Yuanshi tianzun shuo shiyiyao da xiaozai zhou jing 元始天尊說十一曜大消災神咒經 (The Eleven Great Mantra of Dispelling Catastrophe Scripture). The context of this text is similar to the Buddhist sūtra Daweide jinlunfo chishengguang rulai xiaochu yiqie zainan tuoluoni jing 大威德金轮佛顶炽盛光如来消除一切災難陀羅尼經 (Sūtra of the Great Majestic and Virtuous Golden Wheel Usnisa Tejaprabhā Tathāgata Averting All Calamities and Hardships Dhārani), but Śākyamuni is replaced with Yuashi Tianzun 元始天尊 (Primeval Lord of Heaven). The attributes of the personified Five Luminaries, even in Daoist paintings, were borrowed from the Buddhist description; however, the expanded Eleven Luminaries of Daoism influenced the visual representation of Tejaprabhā Buddha in Buddhism. In fact, the Eleven Luminaries were not an invention from the Northern Song. During the year 785 of the Tang Dynasty, Li Biqian 李弼乾 started to promote the Eleven Luminaries system in the capital Chang’an 长安. Those facts prove that the concept of the Eleven Luminaries evolved from astrology into the Daoist belief systems.23 During the Northern Song dynasty, due to the systemization of Daoism and the further secularization of esoteric Buddhism, eleven Luminaries appeared in the visual arts (Xia and Shen 2019, p. 86). By the tenth century, the number of planets grew from nine to eleven, with the addition of two invisible planets of long-debated provenance to the two previously discovered planets of undoubted Indian origin. These eleven planets gained at least as much significance in Daoism as they did in Buddhism. Moreover, the western (solar) zodiac began to appear in an ever-expanding variety of contexts, including Daoist, non-astral Buddhist, and burial art, in modified but still easily recognized forms (McCoy 2017, pp. 9–10).

This sort of assembly representation spread to Korea and can even be witnessed in a painting of Tejaprabhā from the Chosŏn Dynasty (1392–1897), revealing Buddhist and Daoist iconography combined (see Figure 13). This painting shows Tejaprabhā Buddha seated in the midst of his retinue. At his side stand the Sun and Moon Radiance, identified by the sun and moon halo over their heads. In this particular painting, the worship of the Daoist Northern Dipper and Tejaprabhā Buddha is conspicuously combined, for below the Tejaprabhā Buddha sits the bearded figure of the North Pole Star as a Daoist sage, around whom all the stars revolve. He is also flanked by the Sun and Moon. Sixty-nine more figures, symbolizing the twenty-eight constellations, the nine Luminaries, and the twelve signs of the celestial zodiac, were arranged in a circle around these six central figures (Song 2016).

Figure 13.

Painting of the Tejaprabhā Buddha (Chisong Gwangbul) together with the North Pole star (Pukkuk song), British Museum, Mineral colors on coarse silk, From Korea, 136 × 139.6. Dated 1850–1860.

7. Conclusions

It is possible to conclude that Daoism was a significant source of inspiration and guidance for the esoteric Buddhist cult that venerated the celestial bodies as deities (Sørensen 2011, p. 244). Tejaprabhā Buddha is considered one of the most tangential figures in Buddhist mythology because he and his followers do not belong to the core group of Buddhist deities but are instead connected to the Daoist deities. This was most likely due to the fact that asterism held a greater significance to Daoists, for whom it was the most important of all the power sources derived from the cosmos. The whole Daoist canon may be devoted to the method of knowing the esoteric significance of the Big Dipper and its components, of learning to project one’s secret self into it, of realizing it inside one’s inner anatomical chambers, and of invoking it to stimulate, foster, and trigger miracles (Schafer 1977, p. 49).

The ancient Chinese viewed a star as analogous to a human being, with both spiritual and physical attributes that might be expressed in a variety of ways and to differing degrees (Schafer 1977, p. 42). We can draw the conclusion that planetary worship in the context of China Esoteric Buddhism was never a consistent tradition; rather, it was one that was constantly changing under the influence of Daoism. This is evidenced by the progression from the Five Luminaries to seven, then nine, and finally eleven. Mars, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn, along with Mercury, make up the fundamental group of five stars that correspond to the five elements in traditional Chinese metaphysics. It is difficult to make a clear distinction between the doctrines and practices of Buddhism and Daoism (Sørensen 2011, p. 244). Moreover, there are many overlaps between the Daoist and Buddhist representations of the cosmic pantheon, both function-wise and iconographic-wise. In terms of function, the uniform objective is to avoid danger and seek benefits. In terms of iconography, the majority of depictions of Tejaprabhā Buddha demonstrate a relatively harmonious synthesis of Buddhist and Daoist imagery and concepts (Sørensen 2011, p. 244).

Of all the Buddhas, Tejaprabhā is probably the one most readily associated with the power of an emperor because the golden wheel that he holds signifies that he is the monarch of the four continents that may be found circling the Buddhist World Mountain Meru in the four cardinal directions (Gridley 1998, p. 11). Tejaprabhā Buddha’s prime function, to a large extent, was to serve as a magical control to avert cosmic calamities and disasters.

In China, the worship of Tejaprabhā remained significant until the end of the Yuan dynasty. The 10th to 14th centuries were a time of civilizational collision and fusion in East Asia, and the belief in the Tejaprabha Buddha, which began in central China, expanded rapidly to the xizhou huihu 西州回鶻 (a local regime that existed in Xinjiang, China from 866 AD to the early 13th century) (Qin 2021, p. 190). By the start of the eleventh century, it was present in the Liao and Koryo kingdoms as well as Heian Japan. As evidenced by votive artworks ranging from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, the Tejaprabhā worship persisted far into the premodern period in both Korean and Japanese culture (Sørensen 2011, p. 241).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.C. and B.H.; methodology, Y.C. and B.H.; investigation, Y.C. and B.H.; resources, Y.C. and B.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.C. and B.H.; visualization, Y.C. and B.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Eugene Wang, Stephen Little, and this journal’s academic editors and anonymous reviewers for their invaluable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Ch. | Chinese |

| Skt. | Sanskrit |

| T | Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏經 [Newly compiled Tripiṭaka of the Taishō era], edited by Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 and Watanabe Kaigyoku 渡邊海旭. Tokyo: Issaikyō Kankōkai, 1924–1932. Chinese Buddhist Electronic Texts Association (CBETA) edition, https://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/, accessed on 1 September 2022. |

Notes

| 1 | Attributed to Yixing 一行 (683–723), a prominent monk and astral expert of the Tang Dynasty. |

| 2 | “首冠五佛像,二手如釋迦” T19·343b. |

| 3 | “孫知微……精黃老學,善佛道畫,于成都壽寧院畫熾盛光九曜及諸牆壁,時輩稱伏.” (Guo 1934, p. 322). |

| 4 | The constellation is known as the Great Bear or the Big Dipper in the Western Hemisphere. The Chinese Beidou venerated as a heavenly monarch by Chinese Buddhist monks was vastly distinct from the Indian Beidou that was later adopted. The Indian Beidou is a collection of eight female deities, not a supreme ruler. In Tantric religious pantheons in India, women occupy comparatively low positions (Jing 2002, p. 215). |

| 5 | Attributed to Yixing 一行. |

| 6 | Ge Hong 葛洪 (283–343) was a minor official in the south of China during the Jin Dynasty (263–420), most known for his interest in Daoism, alchemy, and longevity practices. |

| 7 | The content of the table was translated by Jeffrey Kotyk, see (Kotyk 2017, pp. 48, 51, 52, 54, 55). |

| 8 | “其神形如卿相,著青衣,戴亥冠,手持華果.” (Takakusu and Watanabe 1924–1934, T 1311, 21: 461c6–7). |

| 9 | “其神狀婦人,頭首戴猴冠,手持紙筆.” see (Takakusu and Watanabe 1924–1934, T 1311, 21: 460a25–26). |

| 10 | “神形如外道,首戴驢冠,四手兵器刀刃.” see (Takakusu and Watanabe 1924–1934, T 1311, 21: 460c26–27). |

| 11 | “形如女人,頭戴首冠,白練衣,彈弦.” see (Takakusu and Watanabe 1924–1934, T 1311, 21: 460b19–20). |

| 12 | “其神如波羅門,牛冠首,手持錫杖.” see (Takakusu and Watanabe 1924–1934, T1308, 21: 449b1–2). |

| 13 | “爾時釋迦牟尼佛,住淨居天宮,告文殊師利菩薩摩訶薩,及諸四眾、八部、遊空大天、九執、七曜、十二宮神、二十八星、日月諸宿.” T19n0964:338b). |

| 14 | According to the records kept by the British Museum, a large strip of purple silk can be seen at the very top of the picture. This strip demonstrates that the artwork was initially placed as a hanging scroll. |

| 15 | Eugene Wang believes that the purpose of placing this print of Tejaprabhā dominating the Nine Luminaries inside a sculpture of Śākyamuni in the pagoda was to assist in the apotheosis of the Liao emperor Xinzong (r. 1031–1055), and to ensure the protection of a major cache of sūtras that the monks had placed in the sculpture with the print. See (Wang 2011, pp. 127–60). |

| 16 | Other sources perceived that a Sui translation of an Indian Buddhist text contains the earliest known Chinese references to the twelve Western zodiac signs. 760 CE Tang translations of other Buddhist texts, like the sūtra known as Xiu yao jing宿要經 (Lunar lodges and planets), have additional references to the zodiac. However, by the Tang period, the majority of the Chinese names for the zodiac signs had remained unchanged. |

| 17 | “若羅睺計都暗行人本命星宮, 須誦此北斗真言.” Suyao yigui 宿曜儀軌 (Ritual Proceedings [for Worshipping] the Asterisms), T. 21: 423b. Translated by Eugene Wang, see (Wang 2011, p. 150). |

| 18 | Chinese astrologers classified the ecliptic into four sections, or “symbols,” each of which was associated with a mystery animal. To the east is the Azure Dragon, to the north the Dark Warrior, to the west the White Tiger, and to the south the Vermilion Bird. A total of 28 mansions may be found around the globe, with seven found in each of the seven regions. Mansions, also known as xiù, are latitudes that the Moon travels through in its monthly orbit around the Earth. See (Kistemaker and Sun 1997, p. V.38) |

| 19 | Cited in (Gridley 1998, p. 7). “Sūtra Spoken by the Buddha [Giving] the dhāraṇī of Tejaprabha of Great Virtue Which Rids of Calamities and [Brings] Good Fortune,” (Fo shuo Chishengguang daweide xiaozai jixiang tuoluoni jing), Taizōkyō, vol. 19, p. 963). |

| 20 | For the astrological meaning of Rāhu, Ketu, Yuebei, and Ziqi in China, see (Liao 2004, pp. 71–79). |

| 21 | Gridley believes that in the 1258 disputation, Laozi’s journey to the west was crucial to the Daoists’ argument that Daoism was the superior religion. |

| 22 | In 1258, during Khubilai’s rise to power, there occurred an event necessary for the interpretation of the Daoist context and content of the mural. Although not enthroned until 1260, Khubilai had been gaining power from 1251, when his brother Mongke took the throne. In 1258 Khubilai, at the command of Mongke, presided over a Buddhist and Daoist disputation, which Khubilai convened in an effort to defuse a religious conflict between Buddhists and Daoists that had escalated into pitched battles and the destruction of temples and monasteries. See (Gridley 1998, pp. 7–15). |

| 23 | Although the Chinese people seldom made such a difference, in this context, we need to differentiate between astronomy and astrology in the sense that the present Western world understands these concepts. The establishment of calendars, or other temporal devices, was a part of astronomy, which is the scientific (or pseudoscientific) observation of the motion and locations of celestial bodies. On the other hand, astrology is the practice of calculating and forecasting the movements of celestial bodies in relation to the perceived effect that these bodies have on the world of humans. See (Sørensen 2011, p. 230; Carus 1992, chp. 1). |

References

- Carus, Paul. 1992. Chinese Astrology: Early Chinese Occultism. Petaling Jaya: Pelanduk Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Guangting 杜光庭. 1985. Li Dai Chong Dao Ji 歷代崇道記 [Records of Worshipping Taoism in the Past Dynasties]. Taibei: Xinwenfeng chuban gongsi. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Wenjie 段文傑. 1999. Gansu Cang Dunhuang Wenxian 甘肃藏敦煌文献 [Collection of Dunhuang Documents in Gansu Province]. Lanzhou: Gansu renmin chubanshe, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Gridley, Marilyn. 1998. Images from Shanxi of Tejaprabha’s Paradise. Archives of Asian Art 51: 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Ruoxu 郭若虛. 1934. Tu Hua Jian Wen Zhi 圖畫見聞誌 [Record of Knowledge of Paintings]. In SiBuCongKan XuBian 四部叢刊續編 [An Annotated Catalog of Sibu Congkan]. Shanghai: Shangwu yin shuguan, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hartner, Willy. 1938. The Pseudoplanetary Nodes of the Moon’s Orbit in Hindu and Islamic Iconographies. Ars Islamica 5: 112–54. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Shih-shan Susan 黃士珊. 2014. Tangsong shiqi fojiao banhua zhong suojian de meijie zhuanhua yu zimo sheji 唐宋時期佛教版畫中所見的媒介轉化與子模設計 [Media Transformation and Modules Design as Seen in Buddhist Prints of the Tang and Song Dynasties]. In Yishushi Zhong De Hanjin Yu Tangsong Zhi Bian 藝術史中的漢晉與唐宋之變 [The Transition from the Han and Jin Dynasty to Tang and Song Dynasty in Art History]. Edited by Yen Chuan-ying and Shih Shou-chien. Taibei: Rock Publishing International. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Anning. 2002. The Water God’s Temple of the Guangsheng Monastery: Cosmic Function of Art, Ritual and Theater. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kistemaker, Jacob, and Xiaochun Sun. 1997. The Chinese Sky during the Han: Constellating Stars and Society. Sinica Leidensia Vol. 38. New York: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kotyk, Jeffrey. 2017. Astrological Iconography of Planetary Deities in Tang China: Near Eastern and Indian Icons in Chinese Buddhism. Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies 30: 33–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Yang 廖暘. 2004. Chishengguangfo goutu zhong xingyao de yanbian 熾盛光佛構圖中星曜的演變 [Changes of A Star Chart in The Illustrations of The Light-emitting Buddha]. Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 [Dunhuang Research] 4: 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Little, Stephen, and Shawn Eichman. 2000. Taoism and the Arts of China. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCoy, Michelle Malina. 2017. Astral Visuality in the Chinese and Inner Asian Cult of Tejaprabhā Buddham, ca. 900-1300 AD. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Sihui 孟嗣徽. 1998. Chishengguang fo xinyang yu bianxiang 熾盛光佛信仰與變相 [The Cult of Tejaprabhā Buddha and its Change]. Zijincheng 紫禁城 [Forbidden City] 2: 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Shanshan 欧阳姗姗, and Xiujun Gao 高秀军. 2022. Chisheng Guangfo Bianxiangtu Zhong de Tuxing Xingxiang Yanbian 炽盛光佛变相图中的土星形象演变 [The Evolution of Saturn Image of the Tejaprabhā Figure]. Tangut Research 1: 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Guangyong 秦光永. 2021. Zhongxi jiaorong yu huayi hudong: Tangsong shidai chishengguang xinyang de chuanbo yu yanbian 中西交融与华夷互动:唐宋时代炽盛光信仰的传播与演变 [Research on the Evolution and Dissemination of Belief in Tejaprabhā Buddha in the Tang and Song Dynasties]. Academic Monthly 53: 181–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, Edward H. 1977. Pacing the Void: Tang Approaches to the Stars. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Shenmi. 2016. The Twelve Signs of the Zodiac during the Tang and Song Dynasties: A Set of Signs Which Lost Their Meanings within Chinese Horoscopic Astrology. The Circulation of Astronomical Knowledge in the Ancient World. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 478–526. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, Henrik H. 2011. 7. Central Divinities in the Esoteric Buddhist Pantheon in China. In Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Leiden and Boston: Brill, vol. 24, pp. 90–132. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Jiaying 蘇佳瑩. 2011. 日本における熾盛光仏図像の考察 [A Study of the Iconography of the Tejaprabhā Buddha in Japan]. Kobe Review of Art History 2: 109–36. [Google Scholar]

- Takakusu, Junjirō 高楠順次郎, and Kaigyoku Watanabe 渡邊海旭, eds. 1924–1934. Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新脩大藏经 [Newly Compiled Tripiṭaka of the Taishō Era]. Tokyo: Issaikyō Kankōkai. Available online: https://21dzk.l.u-tokyo.ac.jp/SAT/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Wang, Chao 王超. 2020. Chishengguang fo xingxiangtu de sanzhong biaoxian fangshi yu “chengniuche xunshiyang” chishengguang fo xingxiang laiyuankao 熾盛光佛星象圖的三種表現方式與“乘牛車巡視樣”熾盛光佛形象來源考 [The Three Forms of Representation of the Tejaprabhā Buddha and the Origin of the Tejaprabhā Image of the ‘Parade by Bullock Cart’]. Mei yu shidai 美與時代 [Aesthetic and Time] 3: 123–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Eugene Yuejin 汪悅進. 2011. Ritual Practice without a Practitioner? Early Eleventh Century Dhāraṇī Prints in the Ruiguangsi Pagoda. Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie 20: 127–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Guangxing 夏广兴, and Yiping Shen 申一平. 2019. Chisheng guangfo xinyang yu songyuan shehui 炽盛光佛信仰与宋元社会 [Tejaprabhā Belief and the Song Yuan Society]. The World Religious Cultures 1: 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Nai 夏鼐. 1976. Cong Xuanhua Liaomu De Xingtu Lun Ershiba Xiu He Huangdao Shi’er Gong 從宣化遼墓的星圖論二十八宿和黃道十二宮 [The Twenty-eight Constellations and the Zodiac and the Star Altas in the Xuanhua Liao Tomb]. Kaogu Xuebao 考古學報 [Acta Archaeologica Sinica] 2: 35–58. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).