New Iconography in Court-Sponsored Buddhist Prints of the Early Joseon Dynasty—Focusing on Record of the Manifestation of Avalokitesvara

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Record of the Manifestation of Avalokitesvara and Analysis of the Prints

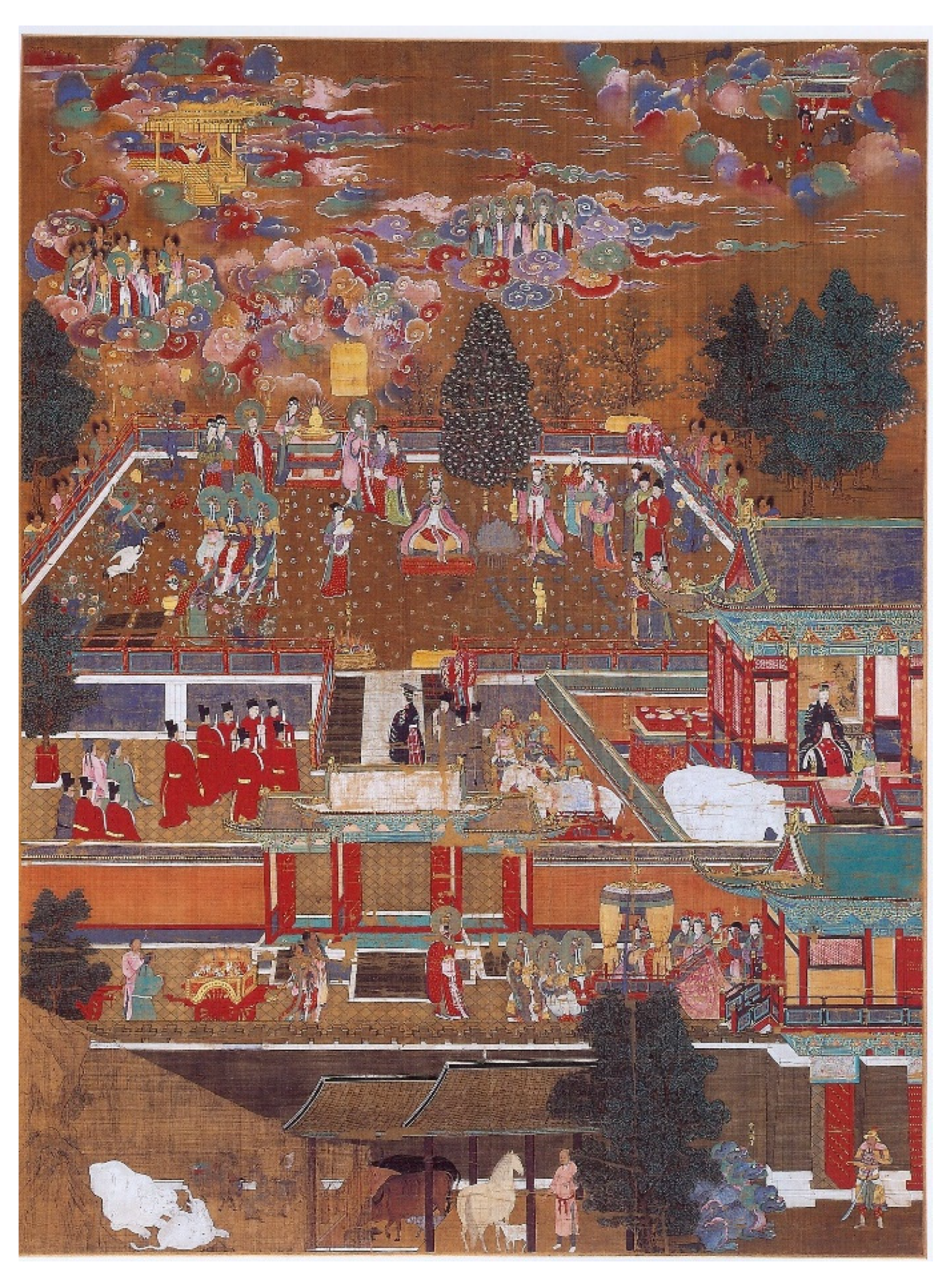

“The king and crown prince went out hunting, and leaving their troops at the bottom of the mountain they headed for Sangwonsa Temple with only a handful of guards. But even before they reached the temple, all sorts of auspicious events took place, and when they finally arrived the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, garbed in white robes, appeared in the sky above Damhwajeon [曇華殿 Udambara Hall, the main hall of the temple] and a light of five colors radiated in all directions in heaven and on earth as everyone exclaimed and worshiped [the bodhisattva]. King Sejo, pleased with this good omen, made offerings at Sangwonsa and wrote a royal decree granting amnesty to tens of prisoners. Upon his return to the palace, he had a statue of Avalokitesvara made and enshrined in a palace hall. He also ordered a picture of Avalokitesvara to be made, as he had witnessed with his own eyes, and distributed it throughout the country.”7

3. Image of the Ruler Projected on Religious Iconography

4. Iconographic Trends in Court-Sponsored Buddhist Prints from the First Half of Joseon

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In regard to court-sponsored Buddhist projects and artworks during the first half of the Joseon dynasty, see (Kwak and Kang 2018, pp. 207–37); (Kim 2019, pp. 39–72; 2021a, pp. 186–94); (Kim 2002, pp. 59–95; 2007, pp. 107–50); (Nam 2007, pp. 555–83); (Park 2002, pp. 155–83); (Park 2011a, pp. 5–37); (Eom 2012, pp. 463–506); (Chung 1999, pp. 129–66); (Choi 2017, pp. 123–44). |

| 2 | Choe Hang was a great scholar who served as a court official for 40 years, from the reign of King Sejong to the reign of King Seongjong. He led various publishing projects of the court and was almost solely responsible for writing the memorial letters to the throne carried by envoys on their missions to the Ming dynasty. These letters, called pyjeonmun 表箋文 (baojianwen), consisted of the pyomun, a memorial letter for the emperor, and the jeonmun, a memorial letter for the empress dowager, empress, or imperial crown prince. |

| 3 | Sangwonsa Temple was built in the Goryeo dynasty on Mt. Yongmunsan 龍門山 (formerly Mt. Mijisan 彌智山) in Yangpyeong-gun. Sangwonsa Temple maintained close relations with the court, as evidenced by the Annals of King Sejong, which say that in the first month of 1450 (32nd year of the reign of Sejong), the king, to heal disease, held a Water and Land Ritual at Sangwonsa Temple, which was also the prayer temple of Prince Hyoryeong during the reign of King Sejo, and that in 1457 (3rd year of the reign of Sejo) the king had one set of the Tripitaka Koreana, preserved at Haeinsa Temple 海印寺, carved and printed and the books were stored at the temple. |

| 4 | This print is used for research on temple architecture and landscaping in the first half of the Joseon dynasty as it is a realistic depiction of Sangwonsa Temple at the time. For further information, see (Lee 2007, pp. 160–63); (Hong and Hwang 2013, pp. 114–21). |

| 5 | Sejong sillok (Annals of King Sejong), 7th day of the 3rd month of 1467 (13th year of the reign of Sejong). |

| 6 | Sejo sillok (Annals of King Sejo), 29th day of the 10th month of 1462 (8th year of the reign of Sejo), which states that King Sejo stopped by Prince Hyoryeong’s farm at the foot of Mt. Mijisan and then proceeded to Sangwonsa Temple accompanied by the prince, Do Jinmu 都鎭撫, and others, and later returned to the farm where he stayed for a while. |

| 7 | For the content and commentary of the text, see (Kim 2017, pp. 138–41). |

| 8 | For details on the content of the two prints, see (Kim 2021b, pp. 69–71, 80–81). |

| 9 | For information on Buddhist auspicious signs, see (Park 2011b, pp. 25–66). |

| 10 | The portraits of Emperor Yingzong (r. 1435–1449), Emperor Tianshun (r. 1457–1464), and Emperor Chenghua (r. 1464–1487), who maintained ties with Tibetan religious leaders, differed from the portraits of previous emperors. They not only faced forward but wore imperial robes decorated with 12 symbols of the rule including the sun, moon, and mountain peaks, which became established as the typical style of imperial portraits. For further information on interest in Tibetan Buddhism in the Ming court and changes in Ming dynasty imperial portraits, see (Dora 2008, pp. 321–58). |

| 11 | Sejo sillok (Annals of King Sejo), 8th day of the 2nd month of 1459 (5th year of the reign of Sejo); 27th day of the 9th month of 1463 (9th year of the reign of Sejo). |

| 12 | Yeonsangun ilgi (Diary of Yeonsangun), 6th day of the 9th month of 1498 (4th year of the reign of Yeonsangun). Although Sangwonsa, Yongmunsa, and Sanasa 舍那寺 are independent temples because they form a single compound and are managed by the same clan, they were often grouped together under the name Yongmunsa. Hence, while this record states that King Sejo saw Avalokitesvara at Yongmunsa Temple, when various other records are taken into account, it would be proper to regard this as a reference to Sangwonsa Temple. |

| 13 | Sejo sillok (Annals of King Sejo), 17th day of the 9th month of 1456 (2nd year of the reign of Sejo); 21st day of the 5th month of 1460 (6th year of the reign of Sejo) etc. |

| 14 | Munjong sillok (Annals of King Munjong), 10th day of the 4th month of 1450 (1st year of the reign of Munjong). |

| 15 | Seongjong sillok (Annals of King Seongjong), 25th day of the 5th month of 1472 (3rd year of the reign of Seongjong). |

| 16 | Sanggyojeong Edition of Repentance Rituals of Compassion Altar is based on the contents of Repentance Rituals of Compassion Altar, which were revised, rearranged, and augmented in the Yuan dynasty. Two prints from this scripture remain extant, including the Liang Huang Repentance Liturgy, mentioned in the text as an example of a print depicting Buddhist history, and Denominated Buddha (Bulmyeongdo 佛名圖), which features a Buddhist icon and its name. |

| 17 | Seongjong sillok (Annals of King Seongjong), 25th day of the 5th month of 1472 (3rd year of the reign of Seongjong); 27th day of the 5th month of 1476 (7th year of the reign of Seonjong). |

| 18 | Seongjong sillok (Annals of King Seongjong), 21st day of the 1st month of 1471 (2nd year of the reign of Seongjong), 22nd day of the 1st month of 1471. |

| 19 | In regard to the adoption and change in Ming dynasty editions of the sutras during the first half of the Joseon dynasty, see (Kim 2017, pp. 96–122). |

| 20 | The earliest of such prints that remain extant are found in Weorin seokbo 月印釋譜 (Episodes from the Life of Sakyamuni Buddha), published in 1459 by King Sejo, which unites Weorin cheongang jigok 月印千江之曲 (Songs of the Moon’s Reflection on a Thousand Rivers), written by King Sejong in 1449, and Seokbo sangjeol (Biography of Guatama Buddha), published in 1447. |

| 21 | For the foreword of Seokbo sangjeol and related content, see (Lee 2016, p. 284). |

| 22 | Three prints contained in Vol. 21 of the Imperial Commentary depict fifteen scenes from the Buddha’s life, from birth to attaining enlightenment. For more detailed information, see (Kim 2011, pp. 35–68). |

| 23 | For more detailed information, see (Chung 2006, pp. 227–29). |

References

Primary Sources

Annals of King Taejong (Taejong sillok) 太宗實錄.Annals of King Sejo (Sejo sillok) 世祖實錄.Annals of King Munjong (Munjong sillok) 文宗實錄.Annals of King Songjong (Songjong sillok) 成宗實錄.Choe, Hang, Record of the Manifestation of Avalokitesvara (Gwaneum hyeongsanggi) 觀音現相記. Joseon (Mid-15th century).Daily Records of Yeonsangun (Yeonsangun ilgi) 燕山君日記.Episodes from the Life of Sakyamnuni Buddha (Weorin seokbo) 月印釋譜, Joseon (1459).Contrition in the Name of Amitabha Buddha (Yenyeom mita doryang chambeop) 禮念彌陀道場懺法, Joseon (1474).Lotus Sutra (Myobeop yeonhwagyeong) 妙法蓮華經, Joseon (1422).Nam, Hyo-on, Chugangjip 秋江集.Sanggyojeong Edition of Repentance Rituals of the Great Compassion (Sanggyojeongbon jabi dojang chambeop), 詳校正本慈悲道場懺法, Late Goryeo-Early Joseon.Sanggyojeong Edition of Repentance Rituals of the Great Compassion (Sanggyojeongbon jabi dojang chambeop), 詳校正本慈悲道場懺法, Joseon (1474).Secondary Sources

- Beijing Cultural Exchange Museum. 2007. Zhihuasicang yuan ming qing fojing banhua shangxi (智化寺藏元明淸佛經版畵賞析). Beijing: Beijing Yanshan Press (北京燕山出版社). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yu Ning (陈育宁), and Xiao Fang Tang (汤晓芳). 2009. Yuandi keyin xixia wen fojing banhua ji yishu tezheng (元代刻印西夏文佛经版画及艺术特征). Ningxia Social Sciences (宁夏社会科学) 2009-3期: 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, Hye-bong (천혜봉 主編), ed. 1992. National Treasures 14-Augmented Part II (Gukbo 14-jeungbopyeon [ha] 國寶14-增補編 [下]). Seoul: Woongjin Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Kyu-hee (조규희). 2021. The Conflict between Sungbul and Sungyu and the Politics of Landscape Paintings in the Middle of the 16th Century: A study of Thirty-two Responsive Manifestations of Avalokiteśvara from Dogapsa Temple, Muigugokdo, and Dosando (Seungbulgwa seungyuui chungdol, 16segi jungyeop sansu pyohyeonui jeongchihak-dogapsagwanseeumbosal samsipieungtaenggwa muigugokdomitdosando숭불과 숭유의 충돌, 16세기 중엽 산수 표현의 정치학-도갑사관세음보살삼십이응탱과 무이구곡도 및 도산도). Art History and Visual Culture (미술사와 시각문화) 27: 28–67. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Eung-chon (최응천). 2017. The Importance of the Early Joseon Bell Sponsored by Royal Family and That of Heungcheonsa Temple (Joseon jeongi wangsil balwon beomjonggwa heungcheonsa jongui jungyoseong 朝鮮前期 王室 發願 梵鐘과 興天寺鐘의 중요성). The Art History Journal (강좌미술사) 49: 123–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Woo-thak (정우택). 1999. The Study on Palace Style of Buddhist Paintings in the Chosun Dynasty (Joseon wangjo sidae jeongi gungjeonghwapung bulhwaui yeongu朝鮮王朝時代 前期 宮廷畵風 佛畵의 研究). Korean Journal of Art History (미술사학연구) 13: 129–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Woo-thak (정우택). 2006. A Study on the Iconography of Buddha at Birth in the Joseon Dynasty (Joseon wangjo sidae seokgatansaeng dosang yeongu조선왕조시대 釋迦誕生圖像 연구). Korean Journal of Art History (미술사학연구) 250· 251: 227–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dora, C. Y. Ching. 2008. Tibetan Buddhism and the Creation of the Ming Imperial Image. In Culture, Courtiers, and Competition: The Ming Court (1368–1644). Edited by David M. Robinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, pp. 321–58. [Google Scholar]

- Eom, Gipyo (엄기표). 2012. A Study on Buddhist Art in the King Sejo Period of the Chosun Dynasty (Joseon sejodaeui bulgyo misul yeongu 朝鮮 世祖代의 佛敎美術 硏究). The Journal of Korean Studies (한국학연구) 29: 463–506. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Kwang-pyo (홍광표), and Min-ha Hwang (황민하). 2013. A Study on the Landscape of Sangwonsa Temple of Early Joseon Period by Records and Picture in Gwaneumhyeonsanggi (관음현상기를 통해서 살펴본 조선 초기 상원사의 경관 연구 Gwaneum hyeonsanggireul tonghaeseo salpyeobon Joseon chogi gyeonggwan yeongu). Journal of Korean Institute of Traditional Landscape Architecture (한국전통조경학회지) 31: 114–21. [Google Scholar]

- Humanities Research Institute Sogang University 서강대인문과학연구소. 1972. The Sogang Text of the Wŏrin Sŏkpo (Gukhak jaryo je 1 jip weorin seokbo 國學資料 第1輯 月印釋譜). Seoul: Humanities Research Institute Sogang University, vols. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Ide Seinosuke (井手誠之輔). 2005. Taishakuten (帝釋天像). Kokka (國華) 1313: 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jahyeon (Kim Jahyun 김자현). 2011. Study on Woodcut Prints in Eojebijangjeon (including Eojebulbu and Eojejeonwonga) at Nanzenji Temple in Kyoto, Japan (Ilbon namseonsa sojang eojebijangjeonui eojebulbu eojejeonwonga panhwa yeongu 日本 南禪寺 소장 御製秘藏詮의 御製佛賦·御製詮源歌 판화 연구). Art History (美術史學) 25: 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jahyeon (Kim Jahyun 김자현). 2017. Study on Buddhist Sutra Illustration Prints of the First Half of the Joseon Dynasty (Joseon jeongi bulgyo byeonsangpanhwa yeongu 조선전기 불교변상판화 연구). Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Art History, Dongguk University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jahyeon (Kim Jahyun 김자현). 2019. Production and Flow of Sutra Illustration Woodblock Prints Sponsored by the Royal Family During the 15th Century (15segi wangsil balwon bulgyo byeonsang panhwaui jejakgwa heureum 15세기 王室發願 佛敎變相版畵의 제작과 흐름). BULGYOMISULSAHAK (불교미술사학) 27: 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jahyeon (Kim Jahyun 김자현). 2021a. The Royal Family’s Worship of Buddhism in Fifteenth-century Joseon and the Publication of Buddhist Scriptures by the Family of Grand Prince Gwangpyeong (15segi joseon wangsilui seungbulgwa gwangpyeong daegunilgaui buljeon ganhaeng 15세기 朝鮮 王室의 崇佛과 廣平大君一家의 佛典 刊行). BOJO SASANG (보조사상) 59: 183–217. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jahyeon (Kim Jahyun 김자현). 2021b. Transmission of Buddhist Iconography of Western Xia as Reflected in Buddhist Prints (Bulgyo panhwareul tonghae bon seoha bullgyo dosangui dongjeon불교판화를 통해 본 서하 불교도상의 東傳). Dongak Art History (동악미술사학) 29: 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jung-hee (김정희). 2002. The Illustration of Amitayur-dyana-sutra, made in 1465, and the Buddhist Affairs of the Royal Family in the Early Joseon Dynasty (1465 nyeonjak gwangyeong 16 gwanbyeonsangdowa joseon chogi wangsilui bulsa 1465년작 관경16관변상도와 조선초기 왕실의 불사). The Art History Journal (강좌미술사) 19: 59–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jung-hee (김정희). 2007. Prince Hyoryeong and Buddhist Art in the Early Joseon Dynasty (Hyoryong daegungwa Joseon chogi bulgyo misul-huwonjadeul tonghae bon Joseon wangsilui bulsa 효령대군과 조선 초기 불교미술-후원자를 통해 본 조선 초기 왕실의 불사). Art History Forum (미술사논단) 25: 107–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, Dong-hwa (곽동화), and Soon-ae Kang (강순애). 2018. A Study on the Buddhist Texts Sponsored by the Royal Family in the Early Joseon Dynasty (Joseon jeongi wangsil balwon bulgyojeonjeoke gwanhan yeongu조선 전기 왕실 발원 불교전적에 관한 연구). Journal of Studies in Bibliography (서지학연구) 74: 207–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Gyeong-mi (이경미). 2007. A Study on Transition of the Worship of the Sutra and Architecture Embodiment in the Koryo and Joseon era (Goryeo Joseon jeongi beopbo sinanggwa gyeongjang geonchukui byeoncheon yeongu고려‧조선전기 法寶信仰과 經藏建築의 변천 연구). Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Art History, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Yeong-jong (이영종). 2016. Life and Activities of Sakyamuni and Buddhist Temple Paintings of China and Korea (Seokssi wollyuwa junggukgwa hangukui buljeondo釋氏源流와 중국과 한국의 불전도). Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Archaeology and Art History, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zhitan (李之檀 主編), ed. 2008. Complete Works of Chinese Prints (Zhongguo banhua quanji 中國版畵全集) 1. Beijing: Zijincheng Chubanshe (紫禁城出版社). [Google Scholar]

- Nam, Hyo-on (남효온), and Dae-hyeon Park (박대현), trans. 2007. Korean Translation of Chugangjip (Gugyeok chugangjip 국역추강집). Seoul: Institute for the Translation of Korean Classics, Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, Jin-ah (남진아). 2007. Study on the Buddhist Bells sponsored by the Royal Family in the Early Joseon Dynasty (Joseon chogi wangsil balwon beomjong yeongu 朝鮮初期 王室發願 梵鐘 硏究). BULKYOMISULSAHAK (불교미술사학) 5: 555–83. [Google Scholar]

- National Palace Museum (國立故宮博物院). 2015. Jiangxin bilan-yuanzang mingqing Banhua tezhan (匠心筆藍-院藏明淸版畵特展). Taipei: National Palace Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Ah-yeon (박아연). 2011a. Royal Family-Commissioned Buddhist Statues Enshrined inside the Stone Pagoda of Sujongsa Temple in 1493 (1493 nyeon sujongsa seoktap bongan wangsilbalwon bulsanggun yeongu 1493年 水鍾寺 석탑 봉안 왕실발원 불상군 연구). Korean Journal of Art History (미술사학연구) 269: 5–37. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Do-hwa (박도화). 2002. Woodblock Prints of the Late 15th Century Sponsored by the Royal Family-Focused on the prints donated by Queen Jeonghee, the grand-mother of King Seongjong (15segi hubangi wangsil balwon panhwa jeonghui daewang daebi balwonboneul jungsimeuro 15세기 후반기 王室發願 版畵: 貞憙大王大妃 發願本을 중심으로). The Art History Journal (강좌미술사) 19: 155–83. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Se-yeon (박세연). 2011b. The Political Meaning of the Buddhist Omen under King Sejo’s Reign in the Early Years of Joseon (Joseon chogi sejodae bulgyojeok sangseoui jeongchijeok uimi조선초기(朝鮮初期) 세조대(世祖代) 불교적 상서(佛敎的 祥瑞)의 정치적 의미). Sa-chong (史叢) 74: 25–66. [Google Scholar]

- Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage. 2012. Korean Temple Murals–Jeollanam-do Province (Hangukui sachal byeokhwa–jeollanamdo 한국의 사찰벽화-전라남도). Seoul: Research Institute of Sungbo Cultural Heritage. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Lianxi (翁連溪), and Hongbo Li (李洪波) 主編, eds. 2014. Complete Works of Chinese Buddhist Prints (Zhongguo fojiao banhua quanji 中國佛敎版畵全集). Beijing: Zhongguo shudian (中國書店). [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J. New Iconography in Court-Sponsored Buddhist Prints of the Early Joseon Dynasty—Focusing on Record of the Manifestation of Avalokitesvara. Religions 2022, 13, 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111008

Kim J. New Iconography in Court-Sponsored Buddhist Prints of the Early Joseon Dynasty—Focusing on Record of the Manifestation of Avalokitesvara. Religions. 2022; 13(11):1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111008

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jahyun. 2022. "New Iconography in Court-Sponsored Buddhist Prints of the Early Joseon Dynasty—Focusing on Record of the Manifestation of Avalokitesvara" Religions 13, no. 11: 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111008

APA StyleKim, J. (2022). New Iconography in Court-Sponsored Buddhist Prints of the Early Joseon Dynasty—Focusing on Record of the Manifestation of Avalokitesvara. Religions, 13(11), 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13111008