Abstract

In ancient China, all moral concepts are based on Li 禮 (ritual). Jing 敬 (reverence and respect) is one of the core categories of Confucian ritual spirituality and has rich ideological connotations. This study discusses how Confucianism realizes the ritualization of jing and constructs its symbolic system in the capping ritual to strengthen adult consciousness and social responsibility. First, based on relevant classic texts, we clarify the internal relationship between traditional ritual spirituality and jing. Then, we present an overview of the coming-of-age ceremony and discuss how religious beliefs and rituals incorporate Confucian ethical values and aesthetics. Finally, from the ritual uses of time, space, and behavior, we examine the meaning of jing in the specific practice of the traditional Chinese capping ritual and how it is conveyed to participants and observers through ritual implements and behaviors. The results show the capping ritual as an important life etiquette, and Confucianism injects the spirit of jing into every phase to cultivate an emotional response that will instantiate a moral ideal applicable to individuals and the state. In complex, modern societies, it is important to condense the Confucian spiritual connotation of jing and integrate it into modern coming-of-age rites.

1. Introduction

Confucianism has played a vital role in establishing the foundation of religious practice in the traditional societies of East Asia (Jung 2019). Li 禮 (ritual), one of the core concepts of Confucian thought, was initially applied to specifically religious ceremonies, and later extended to refer to the ceremonial expression of respect or grandness and used in a general sense of social ethical standards of hierarchical feudal society (Editorial Board of Ci Hai 1997). As said in the Rites of Zhou (Zhouli 周禮), “The rules have 300 articles and 3000 in detail 經禮三百,曲禮三千”. From the perspective of Confucian thought, the ritual system involves efforts to cultivate one’s inner etiquette behavior, moral conduct and sentiment. It also consists of regulations stipulating human–nature relationships, interpersonal ethical relationships, and the ruling order (Fan and Li 2020; Hsu 2021). Indeed, over time, Confucianism gives meaning to and regulates everyday life in more inclusive ways. Significantly, the essential occasions in people’s lives—commemorating one’s birth, puberty, marriage, and death—have been fundamentally based on Confucian rituals (Jung 2019; Peng 2017).

Durkheim once said, “In fact, if the ritual does not have a certain degree of sacredness, it cannot exist (Durkheim 2008)”. From the primitive religion to the humanistic religion of civilized societies, the purpose of religious rituals is to solve the fear and anxiety that human beings feel towards death. The concern for life directly leads humans to pay attention to turning points of the lifecycle in individual development. The Rites of Passage (van Gennep et al. 1961) notes that birth rituals, coming-of-age rituals, marriage rituals, funeral rituals, and other ceremonies have structures and symbolic meanings similar to transition rites, simulating death and rebirth to rid people of potential danger during these delicate periods. In a person’s lifetime, adolescence is when secondary sexual characteristics emerge, and physiological and psychological status changes significantly and profoundly in both sexes. Almost all cultures attach great importance to this stage in anthropological materials. As a life ritual, the coming-of-age ceremony for men was called the capping ritual (Guanli 冠禮) in ancient China; another for girls was known as the hair-spinning ritual (Jili 笄禮). Because there are few records of the second, for the convenience of writing, this article mainly takes the capping ritual as an example to investigate. The ancients believed that capping marked the beginning of Confucian ritual propriety and helped the youth become a complete person or an adult. We surveyed Mandarin-language literature and discovered many studies on the traditional capping ritual, for example, focused on the historical origin (Yang 1999), institutional changes (Wang 2016), ritual norms (Hardy 1993), costume characteristics (Hsu 2021), and educational value (Ping 2012). However, the ideological implications hidden in the logical structure of capping’s main program have not been sufficiently discussed.

The traditional ritual spirit of jing 敬 (reverence and respect) runs through the development of Confucian thought. Jing is a spiritual demand on secular life and the emotional basis of moral behavior. Compared with the research on other concepts of moral principles (i.e., affection for the family 親親, respect for honor 尊尊, filial piety for elders 孝, humaneness for the treatment of all 仁) born from the patriarchal clan system, the theoretical research and practical attention to jing are relatively weak. Some scholars have begun to explore the relationship between jing, ancient religious beliefs, and Confucian rituals in recent decades (Angle 2005; Liu 2019). These studies indicated that the concept of jing originated from ancient wu 巫 (shaman) activities. Although jing appears to denote religious piety, in fact, it emphasizes human subjectivity and moral principle; this religious emotion and attitude was especially extended in Zhou ritual propriety to one’s sincere reverence towards elders and superiors, which become a part of human shaping (Li 2004; Mou 2008). Based on the role of emotions in classical Confucian conceptions, Jia interpreted the inner orientation of the word chengjing 诚敬 (sincere reverence) in the compound form and emphasized that it was an essential moral emotion and attitude (Jia 2021). Chen (2013) conducted exploratory research around the key words of the capping ceremony and the spirit of respect, but the relevant issues were not discussed in depth. Therefore, although some researchers have realized the importance of jing in the execution of Confucian etiquette, there is a less comprehensive examination of this critical concept in the context of specific rituals.

Li 禮 (ritual) is an essential method and medium to express and strengthen the inner emotion of jing. As an important stage of life etiquette, does the capping ritual carry such an emotional core? What kind of rite arrangements will help the candidate become an adult and qualify for ancestral services? How do people cultivate reverence and respect for their social roles and realize the goal of adult responsibility consciousness and ethical self-discipline? Therefore, based on classical Confucian texts, this study selected the deployment of time, space, and behavior in the traditional capping ritual as an example to discuss how the emotional expression, spiritual essence, and moral connotation of jing are ritualized.

2. The Fundamental Spirits of Confucian Ritual: Jing (Reverence and Respect)

The Chinese term li 禮 is somewhat broader than the English “ritual” since it includes actions and attitudes that we would be more likely to categorize as propriety, decorum, or etiquette. Analyzed from the angle of character shape and origin, li is composed of shi 示 (the god of sacrifice) and li 豊 (the instrument of worship). The first Chinese dictionary, the Origin of Chinese Characters 說文解字 (Xu 2018) compiled by Xu Shen, 121 A.D, explained that “li, to perform or carry out, serving the spirits to obtain blessings (禮,履也,所以事神致福也) (Ing 2013).” Li originated from sorcery rites in prehistoric societies. Its meaning is to hold ceremonies, make sacrifices and seek blessings, expressing a reverence for nature and the worship of deities. It was later extended to a code of conduct or moral attitudes and actions to express respect. The attribute structure of li has the characteristics of religion, morality, social hierarchy, practical principle, institutional factor and politics, and it plays a vital role in distinguishing the status and affinity between individuals and maintaining a hierarchical order of ethical relationships conducive to social stabilization (Sun 2015; Tian 2014). As The Great Learning 大學 (Confucius and Mencius 2003) asserts, “A sovereign should try to reach the realm of benevolence, a minister should try to reach that of reverence, a son, that of filial obedience, a father, that of affection, and those who want to make friends with other people, should try to reach the realm of trustworthiness (為人君止於仁,為人臣止於敬,為人子止於孝,為人父止於慈,與國人交止於信).” The confirmation of li not only assumes the vital function of maintaining patriarchal social order, but also clarifies individuals’ identity in ethical relations. The spirit of li is important, but without the form, the meaning of ritual will cease to exist. Therefore, the significance of formulating rituals lies in constructing a symbolic order. Through poetry, music, ritual implements, and costumes, the public learned inherent moral values, which enlightened adherents on both their status and responsibilities, and consequently, the people fulfilled their duties and obligations.

Jing 敬 (reverence and respect) is the core category of Confucian philosophy, running throughout the development of Confucianism (Fu 2020; Li 2004). The original meaning of jing refers to vigilance against external threats and dissident forces, as well as the feelings of devotion and awe towards heaven in the relationship between humankind and nature. From the Yin-Shang Dynasty to the early Zhou Dynasty, the spirit of jing developed from “god-fearing” to “heaven-fearing”, which was described as a kind of “consciousness of worries and hardships 憂患意識 (Xu 2001)”. However, with the promotion of the “composition of ceremonial melodies” by Duke Zhou, rituals quietly changed from dealing with the relationship between the divine and humans to the relationship of humans with each other, which is more secular. Especially in the late Spring and Autumn Periods, Confucius transformed and updated the original concept of jing and incorporated it into the Confucian ideological system, cultivating personal reverence and respect for social roles and bringing about a strong sense of moral obligation. A ritual system centered on “affection for the family” and “respect for the honourable” emerged, which required all actions between different social roles to incorporate displays of respect. In conclusion, the connotation of jing gradually expanded to social fields, realizing the transition from religion to politics and then to ethics.

Li (ritual) and jing (reverence and respect) are closely related, and they have been mentioned in many classic texts, such as The Chronicle of Zuo 左傳, The Book of Rites 禮记, and The Analects of Confucius 論語. With the spirit of jing as inner psychological support, rituals have universal significance and value in dealing with human relationships with the divine, ghosts, and other humans. According to Hsun Tzu’s discourse on ritual principles, the main official rituals in Confucian states consisted of sacrifices to three kinds of entities: Cosmic forces, royal ancestors, and Confucian sages (Wang 1988). In addition, in early Confucian literature, jing typically manifested a frame of mind that includes single-mindedness, concentration, seriousness, caution, and a strong sense of responsibility for people, things, or states of affairs (Liu 2019). The Record of Rites (Consolidation Committee of Thirteen Classics Explanatory Notes and Commentaries 2000b) said, “Do not be without carefulness; be instead serious in deportment and thinking, and with words as calm as they are sure. Such an example will make people feel at ease (毋不敬,儼若思,安定辭,安民哉)”. Zheng Xuan 鄭玄 (a master of the late Eastern Han) explained that “all rituals are based on the spirituality of jing”. Kong Yingda 孔穎達 from the Tang Dynasty further noted that people must have a respectful heart when they do the five ceremonies—rituals pertinent to circumstances designated as auspicious, inauspicious, fine, guest, and militar. Therefore, in the view of Confucianism, jing is an external attitude and an internal emotion (Li 1997; Liu 2019).

3. The Reconstruction of the Coming-of-Age Ceremony in Confucian Ritual: The Capping Ritual (Guanli 冠禮)

As a life transition, the coming-of-age ceremony is an essential and indispensable rite of passage. It developed from a fertility cult and totem worship in ancient society and is common in modern life rituals for various nationalities. The coming-of-age ceremony has characteristics of transience (goes through the transformation of space–time conditions), separation (achieves isolation from the past environment, worldly things, and the past self), liminality (emphasizes that the individual is in a vague state during the ritual stage), community (completes the integration of different identities and levels, sacred and secular, social and self), and reintegration (realizes the acceptance of clans, ethnic groups, and social groups) (Ping 2012). In a clan-based society, teenagers need to undergo training or a trial of initiation ceremonies at a specific age to master the necessary knowledge, skills, and strong perseverance expected of adults, to be accepted as whole clan members, and to enjoy adult rights and duties (Yang 1999). These activities often test whether individuals can satisfy the immediate goal of survival. Therefore, such a coming-of-age ceremony contains many cruel aspects, i.e., tattoos, ear piercing, nose piercing, and tooth cutting (Zhang 2015). It is believed that physical injury as a symbol can help young people establish a specific connection with clan totems and ancestral beliefs by restraining the power of sacrifice, which have the meaning of religious belief. In summary, the coming-of-age ceremony in primitive societies can be regarded as a ritual activity that mysteriously transforms an organism into a person with religious characteristics.

With the development of increasingly complex social structures, the rites of the clan system changed. A typical example is that the Chinese capping ritual was changed from a ceremony of initiation that existed in earlier clan systems (Yang 1999). Although this ritual still requires a certain amount of education and training to symbolize the passage of youth into adulthood, it must be stressed that it is by no means a simple continuation. In primitive society, the coming-of-age ceremony is mainly used to identify whether young people are adults by their endurance and tolerance to the sufferings of the body and mind; by contrast, the capping ritual in a class-based society aims to introduce the recipient to patriarchal social life through a series of ritual activities marked by clothes and accessories, which reflects the hierarchical relationship between the social status of youth and adults.

“Capping is the beginning of ritual”, stated the chapters “Guanyi 冠義” and “Hunyi 昏義” in the Record of Rites (Liji 禮記) (Consolidation Committee of Thirteen Classics Explanatory Notes and Commentaries 2000b). The capping ritual (Guanli 冠禮) marked the passage from male adolescence to adulthood. A parallel ritual for girls was known as “pinning” (Jili 笄禮), but few details have survived. According to the ritual texts, through capping one becomes a complete person or an adult, and the appropriate age for this transformation was in the twentieth year. The main activities of the capping ritual are “adding the crown,” that is, a young man is capped with three symbolic caps, in turn, dressed in corresponding costumes, and given a style-name (Jiao 2011). As the source for most information on how to perform the rites of life passage, the Book of Etiquette and Ceremonies (Yili 儀禮) (Consolidation Committee of Thirteen Classics Explanatory Notes and Commentaries 2000a) presents the complete description of the capping ceremony in the first chapter, which is entitled “The Ritual for Capping an Ordinary [Citizen] 士冠禮”. The capping ceremony is of great significance in the ancient Confucian ritual system. The Record of Rites (Liji 禮記) records, “In treating him as an adult, they will require from him the behavior appropriate to an adult (ch’eng-jen li). In requiring adult behavior from him, they will demand that he perform the duties (li) of a son, a younger brother, a subject, and a subordinate. If they are going to demand these four types of behavior in his interactions with people, how could they not emphasize this [capping] ceremony? After the demonstrations of filial piety, brotherly deference, loyalty, and obedience are accomplished, he can be regarded as a [full-grown] man. And after he is regarded as a man, he can be used to govern others (成人之者,將責成人禮焉也。責成人禮焉者,將責為人子、為人弟、為人臣、為人少者之禮行焉。將責四者之行於人,其禮可不重與?故孝弟忠順之行立,而後可以為人。可以為人,而後可以治人也).” For these reasons, the sage kings in ancient times emphasized capping. They emphasized that ritual is used to consolidate aristocracy and maintain the patriarchal system to underscore the need for strongman rule (Hsu 2021).

According to the early classic texts, the capping ritual is divided into three stages: Preparation rites, formal rites, and post-transition rites, and it consists of 18 main steps, which are highly complex. The moral concepts in the ancient China context are based on li, and the spiritual core of li is jing. This spiritual dimension has played a vital role in the system maintenance of hierarchy order, the identification of social members, and the ethical cultivation of interpersonal relationships. As the critical period for the development and completion of the Confucian ethical system, the pre-Qin period was also the stage in which the capping ritual was admired and recognized the most deeply. Early Chinese culture was based primarily on kinship ties. As a result, the capping ritual became the core cultural symbol of the spirit of Confucian ritual and gradually broke through the scope of traditional religion. The spirit of Confucianism penetrated every aspect of social life, mandating consciousness, reverence, and respect for Confucian ethics, which has a particular function in ethical education.

4. The Spiritual Expression and Symbolic Analysis of “Jing” in the Traditional Chinese Capping Ritual

4.1. A Reverence for Heaven: The Role of Timing

As stated in the Record of Rites (Liji 禮記) (Consolidation Committee of Thirteen Classics Explanatory Notes and Commentaries 2000b), “In ancient times the date on which the ceremony of capping was held and the host who held it should be fixed by use of the divine of the stalks. This shows the holding of it is grave and earnest (古者冠禮,筮日、筮賓,所以敬冠事).” It describes how the capping ritual used divination instead of an arbitrary marker to determine the appropriate day, highlighting the atmosphere of solemnness and sanctity and reflecting the kindness and blessings given by heaven. The use of tortoise shells to the divine is called a practicing of ‘bo’ (divination by tortoise-shell 龜為蔔), and the use of stalks to the divine is called a practicing of ‘shi’ (divination by use of stalks 策為筮). Divination was born in culture associated with witchcraft. To prevent practical harm brought on by personal choices, the decision of timing was left to sorcery or divination. It says that divination will make humans believe what they do is not wrong while doubted, and the choice of a fortunate date will have a good ending (Chen 2009). Therefore, in traditional Chinese society, events such as capping rituals, wedding rituals, mourning rituals, and sacrifice rituals needed divination.

Some concerns need to be explained first, including whether there is a regular season or month for the capping ritual. Yang (Yang 2017) and Tang (Tang 2010a) have made some interpretations around this issue. In accordance with records in the ancient books of Xia Xiao Zheng 夏小正 (Xia 1981) and Si Min Yue Ling 四民月令 (Cui 1981), as well as unearthed documents (Ding and Xia 2010) such as the Book of Divination 日書 and the Chu Silk Manuscript 楚帛書, most Chinese scholars believe that the capping ritual was primarily held in mid-spring. Through the investigation of ancient records of astronomy and calendars, it is not difficult to find that the traditional Chinese were an agricultural society, and the origin of agricultural activities is closely related to the seasons (Xiao 2016). In the eyes of the pre-Qin Chinese, the change in the four seasons is not only a symbol of the natural order but also a hallmark of the living quality of nature. Based on this, the ancients formed social thought systems that respected heaven as a deity and obeyed prescribed times for various sacrificial activities, hoping to communicate the relationship between humans and nature through a mysterious cosmic force. It is known that spring is a symbol of prosperity, growth, and the starting point of the cycle. As a result, people associated the capping ritual with the symbolic characteristics of the spring season, which is fundamental to finding a personified prototypical representation of the universal phenomena of nature. As anthropologist Harrison claimed, the hymn sung in the Dionysian ceremony eulogizes spring and is sung as a coming-of-age hymn for youth to celebrate their “second birth” (Harrison 2008).

Second, what designated particular days in divination as auspicious for the capping ritual? As said in the chapter “Quli 曲禮” in the Record of Rites (Liji 禮記), “To do the affairs outside the ancestral temple you should begin on the odd days, and the affairs internal on the even days. The use of tortoise-shell or stalks to divine the date, beyond ten days is called a distant day, and within ten days is called a near day. The date of making a funeral should divine a distant day, and of making fortunate matters should divine a near day (外事以剛日,內事以柔日。凡蔔筮日:旬之外曰遠某日,旬之內曰近某日。喪事先遠日,吉事先近日).” As the capping ritual is the most important of the fine ceremonies, and it is also an internal affair held in the ancestral temple, even-numbered days may be the best choice. Assuming that the ritual was performed in February, divination should be performed in late January; if the result is unfavorable, people proceed to divine for a day farther off, observing the same rules as above (Yang 2017). Although ancient texts contained instructions for choosing the day for the capping ritual, people did not completely follow the relevant provisions in practice and fixed the ceremony by month, which had some rational characteristics. However, there is no denying that the method of seeking divination hides people’s reverence for the power of the universe.

Importantly, the capping ritual was generally held at the dawn of day as the best time to communicate with the deities. The Book of Etiquette and Ceremonies (Yili 儀禮) said, “The usher asks the Master of Ceremonies to name a time, the steward announces it, saying ‘To-morrow, at full light, the ceremony will commence’ (擯者請期。宰告曰『質明行事』)”. It follows that all things were seen as revitalized in the full light of day. As a result, the capping ritual held at this time would have easily made the ritual candidate feel a particular spirit of reverence. In conclusion, the capping ritual of the pre-Qin Dynasty tended to be held at the dawn of one of the even-numbered days in a specific spring month according to ancient texts. There is evidence to prove that such timing is not accidental. The ritual is held following natural timing, showing an apparent spirit of reverence and obedience to heaven.

4.2. Honoring Ancestors: The Role of Space

As the Book of Etiquette and Ceremonies (Yili 儀禮) recorded, “Divining (with the stalks) is carried out in the doorway of the ancestral temple 筮於廟門”. The temple is a place to worship the ancestors of clans or families and is also sacred land for rites of passage. The Record of Rites points out the importance of holding the pre-Qin capping ritual in the solemnity of the temple: In ancient times they attached importance to the ceremony of capping, so they held this ceremony in the ancestral temple, which showed their respect for the capping. So, they dared not to treat it presumptuously. This was because their positions in the family hierarchy were humbled, and they gave reverence to their ancients (古者重冠,重冠故行之於廟;行之於廟者,所以尊重事;尊重事。而不敢擅重事;不敢擅重事,所以自卑而尊先祖也). The practice of the capping ritual began with divination at the door of the ancestral hall and was then held inside, which reflected the solid centrality of ancestor worship with a spirit of reverence. On the one hand, it emphasized that through this ritual, ritual candidates have the status and responsibilities of adults and are thereby eligible to carry on the family line and serve the ancestors. More importantly, it is hoped that ritual candidates can obtain the recognition and blessings of ancestors through the ritual. These feelings of reverence, awe, and dependence on the ancestors belong to religious emotions.

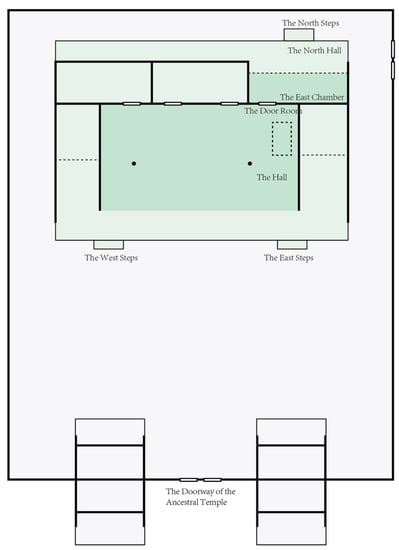

According to the architectural composition and hierarchical principles of the ancestral temple, places such as doors, steps, halls, and chambers contained sacred relationships related to identity conversion, and powerful narratives (Tang 2010b). In the space for the capping ritual, the ritual candidate is mainly involved in three places: The steps, the hall, and the east chamber. The east chamber 東房 carries the most sacred sense of ritual, regarded as a holy space of death and rebirth (Figure 1). Why is the east chamber so crucial in the capping ritual? First, the chamber is the main activity space for ancient Chinese women (mothers). The ancient Chinese architecture and its internal structure contain the profound connotations of the ritual system everywhere, which conveys the concept of social hierarchy, gendered roles, and the desire for heaven’s blessings, indicating distinctions in old Chinese manners. Second, the east chamber is divided into two parts, and the area outside on the north side connected to the stairs was called the north hall. It indicated that the spatial orientation in ancient Chinese temples has a connection to the five elements 五行 (Ye 2005). For example, the north is associated with receding factors such as water, earth, winter, darkness, death, and the female sex. Therefore, compared to the hall in the middle (for the head of a family), the north hall is the feminine place for women (mothers) to stand during the ritual. In addition, there is other evidence that the north hall refers symbolically to women, such as the presence of daylilies (Tang 2010b). The chapter “My lord, Songs of Wei” in the Book of Poetry says, “Where’s the herb to forget? To plant it north I’d start (焉得諼草? 言樹之背)”. The word “herb” refers to daylilies. Planting them in the north hall can make people remember to forget. If women wore daylilies, it means they could have more children, making the daylily a symbol of motherhood in ancient families (Williams 2006).

Figure 1.

The spatial distribution diagram of the ancestral temple. (Reference from the book of The Orientation Map of the Newly Compiled Etiquette and Ceremonial, Mai Jin, published by Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House).

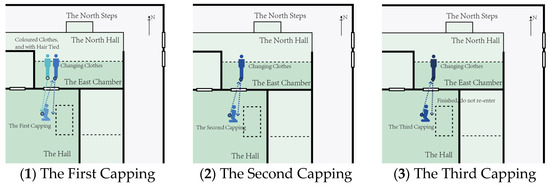

Through many ethnographic writings, it is not difficult to find that the coming-of-age ceremony of various ethnic groups worldwide generally hides a symbolic meaning of resurrection from the dead. For example, the anthropologist Victor Turner (Turner 1970) pointed out that “youth without rites of passage is parasitic in the womb of society, while life is still in a certain dark state”. Meanwhile, it can be found that a sacred place for the coming-of-age ceremony is needed to convey the core meaning of symbolic death and rebirth, such as groves, caves, wigwams, or graveyards. Based on the above analysis, the east chamber, in the spatial intention of the capping ritual, was a symbol of the mother’s body and had the same symbolic identity as resurrection from the dead (Tang 2010b). The ritual candidate, dressed in the clothes of his youth and with his hair tied together in the east chamber, waited before the ritual and shuttled through the hall to salute and change clothes during the three cappings (see Figure 2). After that, the ritual candidate was completely separated from the east chamber and did not return there. Compared with the first (natural) birth from the mother’s abdomen, the process of entering and leaving the east chamber is similar to the action of swallowing and spitting, symbolizing the candidate’s experience of the second rebirth and becoming a complete man who can enter social situations. To summarize, the capping ritual held in the ancestral temple strengthens the clan relationship and implies deep love and gratitude for ancestors and parents. This shows the hierarchical characteristics and ethical norms of ritual space built with jing as the support, highlighting a serious frame of mind.

Figure 2.

The orientation diagram of the ritual “adding three cappings”. (Reference from the description of the Record of Rites and the Book of Etiquette and Ceremonial).

4.3. Valuing Affairs: The Role of Behavior

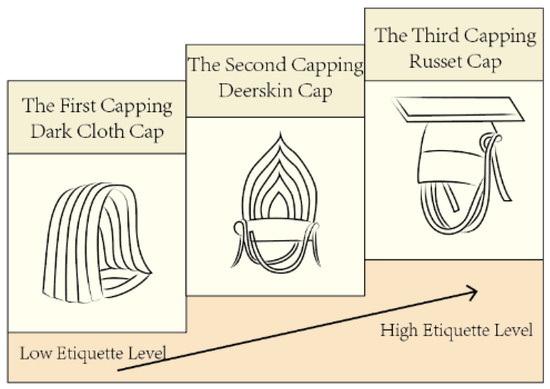

The behavior of “adding the crown 加冠” is the central part of the pre-capping ritual. After a series of preparatory rites, the candidate, with the help of the guest, puts three kinds of symbolic caps on his head and changes into corresponding costumes (Hardy 1993) (Figure 3). As recorded in the Record of Rites, “Hold the ceremony three times, with each more honourable than the last to show that the one has become a full-grown man (三加彌尊,喻其誌也)”. In other words, the three cappings are of a progressive stateliness and are intended to intensify the feelings concerning the significance of the ritual. It was hoped that by paying reverence to ancestors and heaven, people had more emotional access to inspiration and connectedness under the influence of the external environment, thereby eventually shaping the moral character of the candidate imperceptibly and causing him to perceive the rights and obligations of adults.

Figure 3.

The typical crowns of the ritual “adding three cappings” (Reference from the Newly Collated Pictures of “The Three Rituals”, Nie Chongyi, a scholar of Song Dynasty).

There are different ideas underlying the use of the three cappings. First, the candidate received a dark cloth cap 緇布冠 from an assistant. In the chapter “Jiao Te Sheng 郊特牲”, it is said that, “In the remotest antiquity undyed cloth was worn as a head-dress, only when they took part in the sacrifice ceremony their caps were dyed black (大古冠布,齊則緇之)”. At first, the black cloth cap was part of costume-based symbols to remind the candidate not to forget the hardships of the ancestors. The cap also denotes that the youth have since been empowered to participate in family affairs and some aspects of state politics. At the second capping, the guest placed a deerskin cap 皮弁 on the candidate, who again changed his robe and knee covers. The skin cap was made from pieces of white deerskin, which was initially used to protect the head in combat and hunting. The meaning is that the candidate can enjoy hunting and fighting rights and participate in national political and military activities after this ritual. At the third capping, the guest placed the russet cap 爵弁 on the initiate’s head, after which the candidate again changed his ceremonial robes. The russet cap is a flat-topped hat, which is mainly used for mourning and rituals of sacrifice and had the shape of a “round front and square back”, symbolizing heaven and earth. Mourning rituals and sacrifices are state affairs. Their purpose is to remind people to remember the grace of dominators and parents and show respect towards their ancestors. The russet cap for the third capping is horned, indicating that the candidate is endowed with the right to participate in funeral activities and make sacrifices to the ancestors. According to the concept of rites of passage by Gennep (van Gennep et al. 1961), individuals in the liminal phase are seen as the closest to the deities with superhuman powers. Tang (Tang 2010b) discussed the symbolic meaning of typical crowns by adding three cappings according to the ethnology materials, and believed that the deerskin cap seemed to be endowed with some ability to help individuals communicate with mysterious forces. In the pre-Qin records, deerskin was used as a reward or gift. In the chapter “the marriage of an ordinary officer 士昏禮” of the Book of Etiquette and Ceremonial (Yili 儀禮), it can be seen that the present sent by the father of the young man to complete the preliminaries is a bundle of black and red silks and a pair of deer skins. However, it may mean more than that. It might be known as deer and deerskin have sacred symbolic significance. For example, Shaman doctors believed that deer could fly and that wearing an antler hat would continue this function (Martynov 1991). In this sense, the original meaning of adding cappings seems to symbolize specific abilities to communicate with mystical forces, showing an intentional state of respect. With further research, there may be more evidence to support this idea.

The spirit of jing reflects an attitude and value pursuit of life. The tedious process of “adding the crown” shows the ancient people’s concentration, seriousness, and cautious attitude towards life. As the carrier of ritual symbolism, costume embodies the practical significance of the rite of passage and highlights the inner meaning of Confucian ritual spirituality. The threefold capping means that each cap is honored more than the last, thus reminding the candidate to reverently restrain their demeanor and preserve the integrity of their virtue. More importantly, the effect of the entire process is to increase the candidate’s resolve and then develop an inner sense of reverence for individuals, families, societies, and countries. The change of clothes and crowns corresponds to the meaning representation of “death and rebirth”, which reminds of the clarity of power and obligation for men. In conclusion, the capping ritual created an intentional state of respect for the candidate, making them feel and experience it, thereby cultivating personal reverence and respect for social roles through emotional rendering and self-discipline.

In addition, there are other behaviors worth noting during the capping ritual (Wang 2019). For example, implements for the capping ritual are placed in the western inner hall of the east chamber from north to south according to the order of their use. The place where the guest who officiates the ritual stands, and those of the family members in attendance, all have a hierarchical order. The pursuit of the sense of order and harmony in ancient rites reflects the promotion of the candidate’s inner respect through ritual behaviors, which organically combine the direct quality and symbolism of the Confucian spirit (Hsu 2021).

5. Concluding Remarks

Confucianism has played a vital role in establishing the foundation of East Asian civilizations. This study firstly used the literature to sort out the internal relationship between li (ritual) and the spirit of jing (reverence and respect). For the state and society, the traditional ritual is a means of state domination, and it affirms hierarchical distinctions to restrain social conflict. For individuals, it had the capacity to restrain personal emotion and strengthen internal cultivation. As the external expression of natural human emotion, the spirit of jing is positively expressed and, at the same time, properly controlled under the guidance and cultivation of Confucian etiquette. People inspired this natural feeling through a symbolic system that guided the Confucian rites of passage in life. These ideas were proven in several ways in subsequent discussions.

Second, we reviewed the historical evidence for the actual performance of the coming-of-age ceremony and discussed the different characteristics and signs of coming-of-age ceremonies in primitive societies and feudal societies. In the Confucian context, capping was the ceremony in which adolescent males were initiated into adulthood. It seems particularly useful for reflection on early moral emotions since it belongs to a category of ritual that has received considerable attention throughout the world. It is concluded that the feeling of jing was ritualized in the traditional capping ritual and permeated the whole procedure. The capping ritual’s arrangement of time and space have sacred purposes to reflect gratitude for the kindness given by heaven and to obtain the blessings of ancestors by offering sacrifices. More importantly, simulating the cycle of the four seasons captures the inherent meaning of “death and rebirth”. On the other hand, through a set of standardized actions, costume supports, and ritual implements, the ceremony created a solemn situation to help the candidate internalize moral emotions in practice. The psychological benefits of capping are always subordinated to its social functions, and foremost among them was the patriarchal education of a young man in an atmosphere of reverence and respect.

With the spread of traditional Confucianism in East Asia, the capping ritual was absorbed and transformed into ceremonies with local cultural and custom characteristics. The Chosun Dynasty in Korea and Edo Japan continued this ritual from China, and it still exists today. For example, Korea defines the third Monday of May as the day of 성년의 날, while Japan defines the second Monday of January as the day of 成人の日. The ceremonial functions of the capping ritual have been observed to reflect cultural values and shape spiritual thought. On this point, the early ritual texts were quite successful. However, if continued use is an index of a ritual’s satisfactoriness, capping was inappropriate in later imperial China (Hardy 1993). Although the cap has been an essential item of formal costume throughout Chinese history, gradually, the capping ritual ceremony was no longer strictly practiced. The Ming and Qing dynasties frequently noted that other family rituals enjoyed greater continuity. The capping got lost in the transition.

Spirituality is rooted in the essence of Confucian capping rituals and etiquette. In contemporary social contexts, adolescents have become pioneers in the development of a modern lifestyle. Their phase of life is increasingly expanding, and they are gradually faced with the structural characteristics of status insecurity and status inconsistency (Hurrelmann and Quenzel 2015). The lack of etiquette and the confusion of moral values among young people in Chinese society makes it necessary and urgent to return connotations of traditional etiquette and Confucian spirit. Although the proposal to revive the capping ritual received social attention in the early 2000s, it still faces the development dilemma of maintaining and transforming the connotation of Confucian rituals in contemporary society. It can be said that the moral symbolism and the emotional expression of the capping ritual are influenced by the change of context in cultural essentialism, nationalism, and popular culture. However, these discourses are still worthy of reflection from both normative and descriptive perspectives, rather than arguing that they are outdated and need to be written off to “purify” Confucian ethics. Therefore, this study explores the ritualized presentation of the feeling of jing in the capping from a cultural perspective, hoping to contribute to the current trend of approaching Confucian ethics from a more comprehensive perspective. At the same time, it will help us further understand the interaction between the Confucian ritual spirit and the reform of modern ceremonies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. and Y.S.; formal analysis, Y.W. and Q.J.; investigation, Y.W. and Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. and H.L.; supervision, H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L and Y.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province” (NO.KYCX22_2293) and “The National Social Science Foundation Project of Art” (NO. 21BG142).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Angle, Stephen C. 2005. Ritual and Reverence in Ancient China and Today. Philosophy East and West 55: 471–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Juanjuan 陳娟娟. 2013. The Study of the Spirit of “Respect” in the Capping Ceremony 冠禮中的「敬」精神研究. Master’s thesis, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Lai 陳來. 2009. The World of Ancient Thought and Culture 古代思想文化的世界. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Confucius, and Mencius. 2003. The Four Books 四書. Beijing: Chinese Cultural and Historical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Consolidation Committee of Thirteen Classics Explanatory Notes and Commentaries 十三經註疏整理委員會. 2000a. The Commentary of the Book of Etiquette and Ceremonial 儀禮註疏, Thirteen Classics Explanatory Notes and Commentaries 十三經註疏 ed. Bejing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Consolidation Committee of Thirteen Classics Explanatory Notes and Commentaries 十三經註疏整理委員會. 2000b. The Commentary of the Record of Rites 禮記正義, Thirteen Classics Explanatory Notes and Commentaries 十三經註疏 ed. Bejing: Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Shi 崔寔. 1981. The Interpretation of Simin Yueling 四民月令輯釋. Beijing: Agriculture Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Sixin 丁四新, and Shihua Xia 夏世华. 2010. Study on the Thought of the Bamboo Slips and Silk: The Forth 楚地簡帛思想研究 4. Wuhan: Chongwen Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Émile. 2008. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by Carol Cosman. Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks. [Google Scholar]

- Editorial Board of Ci Hai 辭海編輯委員會. 1997. Ci Hai 辭海. Shanghai: Shanghai Lexicographic Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Kuokuang, and Xuehui Li. 2020. Taking Lacquer as a Mirror, Expressing Morality via Implements: A Study of Confucian Ritual Spirituality and the Concept of Consumption in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Religions 11: 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Fenge 付粉鸽. 2020. Political Ethics, Communication Norms, Self-cultivation: Philosophical Implication of Confucian “Reverence” Concept 政治倫理·交往規範·修養工夫:儒家“敬”觀念的哲學意涵. Journal of Xidian University (Social Sciences Edition) 30: 129–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, Grant. 1993. The reconstruction of ritual: Capping in ancient China. Journal of Ritual Studies 7: 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Jane Ellen. 2008. Ancient Art and Ritual 古代藝術與儀式. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Naiyi. 2021. Dressing as a Sage: Clothing and Self-cultivation in Early Confucian Thought. Dao 20: 567–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurrelmann, Klaus, and Gudrun Quenzel. 2015. Lost in transition: Status insecurity and inconsistency as hallmarks of modern adolescence. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 20: 261–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ing, Michael DK. 2013. Ritual as a Process of Deification. In By Our Rites of Worship: Latter-Day Saint Views on Ritual in History, Scripture, and Practice. Edited by Daniel L. Belnap. Provo: BYU Religious Studies Center, pp. 349–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Jinhua. 2021. Writings, Emotions, and Oblations: The Religious-Ritual Origin of the Classical Confucian Conception of Cheng (Sincerity). Religions 12: 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Jie 焦杰. 2011. On the Symbolism of Crown Ceremony and Hairpin Rite during the Pre- Qin Period 試論先秦冠禮和笄禮的象征意義. Nankai Journal, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Jaesang. 2019. Ritualization of affection and respect: Two principles of Confucian ritual. Religions 10: 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Chunqing 李春青. 1997. The historical meaning of “Jing” and its multidirectional value 論“敬”的歷史含義及其多向價值. Jounal of Liaoning University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zehou 李澤厚. 2004. Reading the Analects Today 論語今讀. Beijing: Sanlian Bookstore. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Pengbo. 2019. Respect, Jing, and person. Comparative Philosophy 10: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynov, Anatoliĭ Ivanovich. 1991. The Ancient Art of Northern Asia. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, Zongsan 牟宗三. 2008. Essential Features of Chinese Philosophy 中國哲學的特質. Shanghai: Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Lin. 2017. Enlightenment Meaning of Confucian’s Life Etiquette 儒家人生禮儀中的教化意涵. Journal of Guangxi University (Philosophy and Social Science) 39: 1–7, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, Zhangqi 平章起. 2012. Study on Moral Function of Coming-of-Age Rites 成年儀式的德育功能研究. Tianjin: Nankai University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Chunchen 孫春晨. 2015. Pre-Qin Confucian Ritual Ethics and its Modern Values 先秦儒家禮制倫理及其現代價值. Studies in Ethics, 40–44, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Qicui 唐啟翠. 2010a. Eastern Chamber and “Rebirth” Shrine—Chinese Myth History from the Perspective of Crown Ceremony 東房與“再生”聖地—從冠禮空間看中國神話歷史. Journal of Western Chongqing University (Social Sciences Edition) 29: 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Qicui 唐啟翠. 2010b. “Rebirth”Myth and Ceremony of Celebrating the Spring Festival—An Inquiry into the Time of Ceremony for Boy’s Coming of Age “再生”神話與慶春儀式—冠禮儀式時間探考. Journal of Baise University 23: 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Jun 田君. 2014. An Introduction to the Theory of “Li” in China 論「禮」的字源、起源、屬性與結構. Journal of Sichuan University (Philosophy and Social Science Edition), 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor Witter. 1970. The Forest of Symbols. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van Gennep, Arnold, Monika B. Vizedon, and Gabrielle L. Caffee. 1961. The Rites of Passage (Les Rites de Passage). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jiewen 王傑文. 2016. The Ideal and Practice of Traditional Chinese Initiation Rites 中國古代“成人儀式”的理想與實踐. Folk Culture Forum, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xianqian 王先謙. 1988. The Complete Works of Xunzi 荀子集解. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yanbo 王艷波. 2019. The Study of Capping Rite and its Value Based on the Ritual Sense 基於儀式感的冠禮及其價值研究. Master’s thesis, Northwest University, Xi’an, China. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Charles Alfred Speed. 2006. Outlines of Chinese Symbolism and Art Motives 中國藝術象征詞典. Translated by Hong Li, and Yanxia Xu. Changsha: Hunan Science and Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Weiying 夏纬瑛. 1981. Scripture Interpretation of Xia Xiaozheng 夏小正經文校釋. Beijing: Agriculture Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Fang 蕭放. 2016. The Research of Seasonal Festivals 歲時節日. Folk Culture Forum, 126–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Fuguan 徐復觀. 2001. A History of the Chinese Theory of Human Nature: Pre-Qin Volume 中國人性論史: 先秦篇. Shanghai: Shanghai Joint Publishing Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Shen 許慎. 2018. Origin of Chinese Characters 說文解字. Translated by Kejing Tang. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Hua 楊華. 2017. Research on Chu Etiquette System 楚國禮儀製度研究. Wuhan: Hubei Educational Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Kuan 楊寬. 1999. History of Western Zhou 西周史. Shanghai: Shanghai People′s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Shuxian 葉舒憲. 2005. Philosophy of Chinese Mythology 中國神話哲學. Xi’an: Shaanxi People′s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Shuye 張樹業. 2015. Capping Ceremony and Way to Be a Man: Interpretive Characteristic of Etiquette in Confucian Philosophy by the Definition of Capping Rite 冠禮與成人之道—由冠禮釋義看儒家哲學的禮義詮釋特征. Journal of Nanchang University (Humanities and Social Sciences) 46: 25–34. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).