Abstract

Religion has an important role in coping with the social and psychological problems encountered in human life. However, one topic has not been studied enough, namely that religious attitudes, which are adopting and living religious values, have positive contributions by changing the characteristics of individuals coping with problems. In this study, the indirect role of meaning in life in the association of religion with depression was examined. The current study was conducted online and was cross-sectional and quantitative, with 1571 individuals aged 18–30 in Turkey. For this purpose, scales of religious attitude, depression, and meaning in life were used. First confirmatory factor analysis, and then correlation and multiple regression analyses, were carried out to test the hypotheses using the SPSS, Amos, and Process Macro Plug-in programs. According to the test results, religious attitude has positive relations with meaning in life, and meaning in life has a negative association with depression. Therefore, it was understood that the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life had mediating roles in the relations of religious attitudes with depression.

1. Introduction

Religion has been essential to making sense of life and struggling with difficulties in all areas of life throughout human history. Studies show that religious attitudes and behaviors are effective in overcoming problems, coping with psychological issues, behavior towards others, and regulating behavior and happiness (Pargament et al. 2004; Ayele et al. 1999; Thomas and Barbato 2020; Koçak 2021a, 2021b; Muruthi et al. 2020). Even during the COVID-19 pandemic period, there have been differences in the approach of individuals to problems in those who are religious compared to those who are not (Yıldırım et al. 2021; Pirutinsky et al. 2020; Sulkowski and Ignatowski 2020; Koçak 2021b). Religious interests and activities have increased even more than before (Stańdo et al. 2022).

In every society, attitudes and behaviors towards religion can change according to society’s education, culture, urbanization, and approach to religion (İshak 2012; Pollack 2015; Hjarvard 2011). As welfare increases in a country, individuals become urbanized, then they become secularized, and thus attitudes and behaviors exhibited in a religious format may lose their connection with religion over time (Halman and Pettersson 2006; van Ingen and Moor 2015; Turner 2010; İshak 2012). While 89% of Turkish society sees religion as an important element, the rate of those who define themselves as atheists is around 3%, with increasing urbanization (Kenton 2019). Despite the increase in the number of deists and atheists in parallel with urbanization, the rate of those who define themselves as religious in Turkish society is around 51% (Kenton 2019). Despite the high rates of urbanization (93.2%) in Turkey (TUIK 2022), it is seen that the respect for religion and the importance given to religious attitudes and behaviors are still at significant rates. In studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic period in Turkey, it has been determined that there are significant relationships between religiosity and individuals’ fear of death, their ability to cope with problems, and their psychological resilience during the COVID-19 period (Kandemir 2020; Kımter 2020; Kalgı 2021; Koçak et al. 2021).

In the literature, there are studies explaining that religion has positive relations with individuals’ mood, well-being, and physical and mental health (Shiah et al. 2015; Bamonti et al. 2015; Dunn and O’Brien 2009; Craig et al. 2022). It was found that individuals’ meaning in life is positively or negatively associated with these variables (Steger and Shin 2012; Steger and Frazier 2005; Van Tongeren et al. 2013; Dulaney et al. 2018; Heine et al. 2006). It is understood that one of the most important problems of today’s modern people is that they cannot adequately comprehend meaning in life (Sezer 2012). Meaning in life varies from individual to individual and can also differ in the same individual at different times (Newman et al. 2018; Bodner et al. 2014; Dulaney et al. 2018). Meaning in life is generally evaluated in two categories: the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life (Steger et al. 2006; Newman et al. 2018; Bodner et al. 2014). The presence of meaning in life refers to how individuals perceive their current life as important and meaningful, while the search for meaning in life refers to the perception of the search for an understanding of meaning in life. However, these two phenomena have different characteristics and can lead individuals to different behaviors (Krok 2015; Li et al. 2021; Huo et al. 2021; Newman et al. 2018; Steger et al. 2006). The presence of meaning in life provides individuals with a certain positive goal and mission sense beyond ordinary life, while the search for meaning in life can bring about a more negative dynamic and active life (Linley and Joseph 2011; Chen et al. 2021; Emmons 2004; Newman et al. 2018; Steger et al. 2006; Bodner et al. 2014). Finding meaning in life enables individuals to interpret and direct their experiences, set priorities, and use their strengths best (Steger 2012). The changes and difficulties caused by the capitalist system and modern life, which make people work more to meet their needs, may lead individuals to search for more about their existence and what they do in a finite world. However, regardless of all these factors, a human being’s existence also raises the question of why I exist (Sezer 2012). When this question is answered and interpreted, the quality of life is also affected.

Meaning in life is enhanced by goals and by acting in accordance with them, by having a spiritual and religious lifestyle, and by certain activities and self-esteem (Steger 2012). In most studies, there is not enough research on how religion’s effect on individuals occurs, what changes affect individuals’ life satisfaction, and physical and mental health. Therefore, in this study, an answer was sought to the question of how the relations of religious attitudes with depression occurs. For this purpose, it was investigated whether meaning in life has a mediating role in the relations of religious attitudes with depression. This study was based on Viktor Frankl’s theory that, when individuals make sense of life, they have a unique mission to strive for throughout their lives (Frankl 1963, 2005). Frankl’s theory has been cited as a theoretical basis in many studies on meaning in life (Devogler and Ebersole 2016; Glaw et al. 2016; Molasso 2006; Schnell and Becker 2006; Martela and Steger 2016; Zika and Chamberlain 1992; Steger 2012; Steger and Shin 2012). Many factors, such as civilization, life satisfaction, well-being, happiness, education, family, work, and relations, as well as religion, have many positive relationships with meaning in life (Grouden and Jose 2014; Zhang et al. 2016). As a result of this research, which surveyed 1571 individuals aged 18–30 in Turkey, it was determined that religious attitudes have negative associations with depression, and meaning in life had a mediating role in this relationship. The importance of religion as a coping mechanism that reduces the psychological problems of individuals by adding meaning in life should be explained to policymakers, practitioners working in the field, and families.

2. Literature Background and Hypotheses

2.1. The Associations between Religious Attitudes, Meaning in Life, and Depression

Religion shapes the lives of individuals and adds a distinct and remarkable meaning to life by influencing individuals’ inner world, lifestyle, social relations, criteria, and psychology (Lim and Putnam 2010; Lindsey 2020; Molteni et al. 2021). Religions see the world as temporary and do not usually promise happiness in the temporary world. According to religions, seeking happiness in the temporary world life may lead to unhappiness (Baumeister et al. 2013). For this reason, struggling with the difficulties and troubles that religious people face in the temporary world are seen as a reward for gaining the hereafter rather than destroying their psychology (Mohamed Hussin et al. 2018; Lum 2017; Şimşir et al. 2017; Cohen et al. 2005). Religiosity has the effect of increasing meaning in life, as well as reducing death anxiety and suicidal tendencies (Wilchek-Aviad and Cohen-Louck 2022; Iverach et al. 2014; Neimeyer and Van Brunt 2018; Abdel-Khalek 2010b). Religion adds value to life by giving reasonable answers to the questions of individuals about their existence, offers individuals a unique sense of belonging and personality, and provides a social support network wherein members of the same religion and beliefs come together. Steger and Frazier (2005) found a positive relationship between religion and meaning in life and found that meaning in life has a mediating role between daily religious behaviors and well-being (Steger and Frazier 2005). Van Tongeren et al. state that religion is a potential source in the development of meaning in life, and, in the research conducted, it was determined that there was a positive association between the two (Van Tongeren et al. 2013). According to the recent literature, meaning in life was associated with religious coping in many studies (Hupkens et al. 2018; Wilchek-Aviad and Ne’eman-Haviv 2016; Yıldırım et al. 2021).

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Religious attitudes have an association with the presence of meaning in life (i) and the search for meaning in life (ii).

Religion affects the individual’s relationship with God as well as the individual’s relationship with the social environment (Tanyi 2002; Novšak et al. 2012). Throughout history, religion’s effect on individuals has been seen in many psychological, social, and cultural areas (Ives and Kidwell 2019; DeFranza et al. 2021; Lipowska et al. 2022; Diener et al. 2011; Koçak 2021c). Religion and spirituality are considered one of the essential mechanisms for dealing with problems. Due to the extreme stress brought by today’s modern city life and the COVID-19 pandemic in recent years, the psychological problems of individuals are increasing. Depression, anxiety, and stress gradually increase in individuals and cause the progression of many mental and physical chronic diseases and disabilities. A negative relationship between religion and spirituality and psychological issues such as stress, anxiety, and depression draws attention in many empirical studies in the literature (Reutter and Bigatti 2014; Hart and Koenig 2020; Paukert et al. 2009; Dein et al. 2020; Koçak 2021b; Thomas and Barbato 2020). In a study conducted in adolescents, it was determined that religiosity had a strong negative relation with depressive individuals (Fruehwirth et al. 2019). In a systematic review study, it was determined that 38% of the studies predicted a decrease in depression, 59% of them predicted an increasing effect of religious struggle, which is called “negative religious coping”, on depression, and that religiosity was more protective in those with psychiatric symptoms (Braam and Koenig 2019). In the study conducted with 68,874 individuals in the sixth and seventh wave of the European Social Survey, it was determined that those who attended religious services had less depressive feelings, that religious people had less depression than non-religious people, and that this situation was more common in regions where religiosity was intense (Van de Velde et al. 2017). Therefore, the following hypothesis was written.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Religious attitudes have a negative association with depression.

The challenges faced by individuals may cause them to understand the cause, effect, and changes of distress and to question the life they exist in. In this sense, the role of meaning in life, adopted in the cognitive adaptation process experienced, is essential for individuals to react to the problems they experience, make sense of them, and control them (Korkmaz and Güloğlu 2021; Steger et al. 2009). It is seen that meaning in life gives individuals the feeling and thought that their life is valuable, and there is a higher risk for individuals who do not have meaning in life to have an increased tendency to use alcohol and drugs and to tend to suicide (Eskin et al. 2020; Glaw et al. 2016; Dunn and O’Brien 2009; Steger et al. 2009). A study conducted with four common religious groups (Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and Muslims) in the USA determined that religiosity is negatively associated with suicide risk, and, when compared to other religions, Muslims had lower rates of suicidal behavior (Gearing and Lizardi 2008; Dervic et al. 2004; Lawrence et al. 2016; Abdel-Khalek 2010a; Lizardi et al. 2007; Eskin et al. 2020). In most empirical studies, it was determined that meaning in life is effective in coping with life’s problems. In this sense, it was understood that meaning in life has negative relations with stress, depression, and physical and mental disorders (Reker and Woo 2011). Especially in extraordinary times such as the COVID-19 pandemic, meaning in life will provide significant support to either adjusting or restructuring life according to the difficulties experienced (Arslan et al. 2022; Lin 2021; Eisenbeck et al. 2021; Korkmaz and Güloğlu 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic period, the mental health of individuals has been seriously impaired due to the social, economic, and psychological problems experienced (Hyland et al. 2020; Lakhan et al. 2020; Koçak et al. 2021). In this sense, there is a need to determine the factors that will contribute positively to the psychological health of individuals during the COVID-19 period (Arslan et al. 2022; Koçak 2021c; Lin 2021; Eisenbeck et al. 2021). In this sense, following hypothesis was written.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The presence of meaning in life (i) and the search for meaning in life (ii) have an association with depression.

In the literature, direct relations between religious attitudes and meaning in life, and direct relations between meaning in life and depression have been determined. In addition, according to the literature, it has been understood that religious attitudes are negatively related with depression. In this sense, it was assumed that meaning in life has a mediating role in the relationship between religious attitudes and depression. Therefore, the following hypothesis was written.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The presence of meaning in life (i) and the search for meaning in life (ii) have a mediator role in the association between religious attitudes and depression.

In addition, studies have found that there are relations between marital status and religiosity (Himawan et al. 2018; Wolfinger and Wilcox 2008). Religiosity appears to increase marital commitment; thus, married people generally have higher levels of religiosity (Olson et al. 2013; Schnell 2009). It was understood that religious attitudes are effective in reducing the problems that arise between married couples (Fard et al. 2013; Orathinkal and Vansteenwegen 2006). Many other studies have found that age, marital status, and parental status are associated with meaning in life (Itzick et al. 2016; Redekopp 1990; Skrabski et al. 2005; Krause and Rainville 2020). In addition, studies have found that income status is associated with religious attitudes, meaning in life, and depression (Kilbourne et al. 2009; Aranda 2008; Chan and Sun 2020; Patel et al. 2018). The literature shows that depression, meaning in life, and religious attitudes are high in low-income societies, groups, and individuals (Garrison et al. 2008; Zimmerman and Katon 2005; Patel et al. 2018). However, some studies have also found a positive correlation between income and meaning in life (Ward and King 2016, 2019). In the current literature, it was understood that there is an association between the employment status of individuals and their depression (Heinz et al. 2018; Friis and Nanjundappa 1986; Schoenbaum et al. 2002). In today’s lifestyle, where urbanization rates are high, risks in working life and employment status can potentially negatively affect individuals’ psychological health. It was understood that this negative relationship increased even more due to risks, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hamouche 2020; Giorgi et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2020). In this sense, there is a positive correlation between unemployed or underemployed individuals and their depression levels (Yoo et al. 2016; Dooley et al. 2000; Anderson and Winefield 2011; Obschonka and Silbereisen 2015). Therefore, the following hypotheses were written.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Marital status has a moderator role between religious attitudes and the presence of meaning in life (i), and the search for meaning in life (ii).

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Income has a moderator role between religious attitudes and the presence of meaning in life (i), and the search for meaning in life (ii).

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Working status has a moderator role between religious attitudes and the depression.

2.2. The Current Study

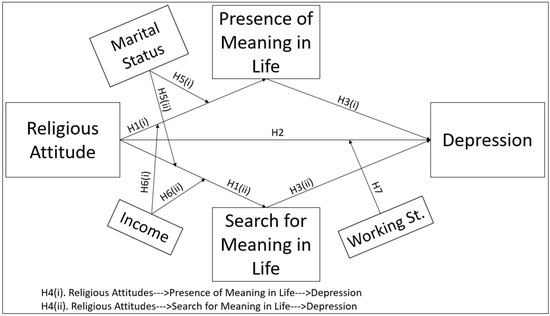

For the current study, the direct relations of the conceptual model set up below were underpinned by the current literature above, and the hypotheses of the direct relations were written accordingly. The present study assumed that meaning in life had a mediating role in the relationship between religious attitudes and depression. According to the literature, there is a relationship between religious attitudes and meaning in life and meaning in life with depression. Therefore, in this study, a conceptual model was established, as seen in Figure 1, and it was thought that meaning in life had a mediating effect. In the present study, it was assumed that marital status had a moderator role between religious attitudes and the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life. Each of the hypotheses underpinned by the literature is shown in the conceptual model.

Figure 1.

Conceptual frame of the model.

3. Participants and Methods

3.1. Participants

Participants living in different cities of Turkey were reached online through the Survey Monkey program. Table 1 shows the demographic data of the participants in our study and the mean and standard deviation values of the scales used. From the categorical variables, it was understood that 75.7% of our sample was female, 24.3% male, 8% married, 92% single, 77.2% had a university degree or higher, and 22.8% had a lower-than-university degree. It was determined that the income levels of 49.1% of the participants was low or lower-middle and that 50.9% of them were middle or above the middle. In the study, it was seen that 83.4% of the sample did not work, and on the other hand, 16.6% were working in a job. Among other variables, the mean age was 20.91 (2.945); religious attitude was 3.5367 (0.90502); PMOL was 4.1804 (1.1247); SMOL was 4.706 (1.03722), and depression was 0.9951 (0.47521).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

3.2. Measures

Personal questions such as gender, education level, marriage status, income levels, and working status were asked in a categorical form to determine the demographic characteristics of the participants, while age was asked in a continuous form.

The meaning in life scale was developed by Steger et al. in 2006 (Steger et al. 2006). Akın and Taş conducted the Turkish reliability and validity study of the meaning in life scale in 2015 (Akin and Taş 2015). In the Turkish translation of the scale, the correlation values between the items were 0.65–0.91. The exploratory factor analysis showed that ten items explained 57% of the total variance and had two scales in line with the original. A 7-point Likert scale was used in the scale, which is not at all true for me (1) and completely true for me (7). In the scale questions, there are items such as I am looking for something to make my life feel meaningful, I am always trying to find my life’s purpose, I know the meaning of my life, and I discovered a fulfilling life purpose. The Cronbach’s alpha of the current study was 0.805.

The scale development and validity study of the religious attitude scale was conducted by Üzeyir Ok in 2011 (Ok 2011). The religious attitude scale was prepared by taking into account the religion of Islam. Testing the scale in Islamic traditions outside of Turkey will show the level of its international validity. In the scale, there are items like “I try to fulfill the requirements of the religion I believe in” and “I really enjoy when I participate in religious activities”. The scale item correlation values were between 0.71–0.76. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale was 0.923.

The depression scale used in the study was developed by Lovibond and Lovibond in 1995 (Lovibond and Lovibond 1995), and the DASS (depression, anxiety, and stress) scale was reduced to 21 items by Henry and Crawford in 2005 and was given the short name DASS-21 (Henry and Crawford 2005). The DASS-21 scale was adapted into Turkish by Yılmaz et al. in 2005 after reliability and validity tests (Yılmaz et al. 2017). The current study used the depression factor of the scale. The scale questions are a 4-point Likert type, not suitable for me (0), somewhat suitable for me (1), generally suitable for me (2), and completely suitable for me (3). In the scale items, there are statements such as I felt miserable and sad and I felt that I was worthless as an individual. The Cronbach’s alpha value of the current study was found to be 0.885.

3.3. Procedure

Participants were reached using the Survey Monkey online survey program through Faculty of Health Science students between 20 October 2021 and 30 November 2021, when the COVID-19 pandemic was intense. The participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the methodology, and data security procedures before the survey began, and their approval was then obtained. Participants were allowed to leave the study whenever they wanted. None of the participants in the study were asked for their IPs or private information. The average duration of the study was around 10–15 min. All research processes were carried out according to the Helsinki Declaration criteria.

3.4. Statistical Analyses

The research was developed as cross-sectional and quantitative. Once the survey part of the research was carried out online via Survey Monkey, the collected data was copied to MS-Excel for the deletion and revision of unnecessary information. First, the IBM SPSS (IBM Corp 2013) program was used for statistical data analysis such as descriptive, reliability, correlation, and reverse coding. Demographic variables were coded, and the meanings of the codes are explained under the tables in which the analyses are shown. The IBM AMOS 25 software was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis to assess the suitability of the data’s measurement model and the factors’ construct validity (Amos 2017). After reaching the required measurement values, data imputation was made, and the factors used in the analyses were created. Finally, multiple regression, mediation, and moderation analyses were performed in the PROCESS–Macro Plug–in SPSS program using Model 4 and Model 7 with 5000 bootstrap and a 95% confidence interval (Hayes and Rockwood 2020). To visualize the moderating results of two-way interactions, a simple slope analysis was used (Dawson 2014).

4. Findings

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In order to test the measurement model designed for the research, confirmatory factor analysis was performed in the IBM AMOS 24 structural equation statistical program (Amos 2017). It was observed that the first values were below the expected model fit values. However, thanks to the execution of the five covariances shown in the modification indices, it was found that the model fit values matched the expected values. It was also found that these values met Kline’s cut-off criteria (Cmin/df < 5, CFI, TLI, NFI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.80). Therefore, after it was understood that the actual measurement model values were at very good levels, as shown in Table 2, a new SPSS data file was created by creating factors with the use of data imputation analysis.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis values.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

According to the correlation analysis shown in Table 3, age was positive with working status (r = 0.625, p < 0.01), religious attitude (r = 0.066, p < 0.01), and the presence of meaning in life (r = 0.093, p < 0.01) and was negatively correlated with depression (r = −0.086, p < 0.01). Marital status had a negative relationship with income (r = −0.101, p < 0.01), working status (r = −0.385, p < 0.01), religious attitude (r = −0.111, p < 0.01), and the presence of meaning in life (r = −0.119, p < 0.01), and marital status had a positive relationship with education (r = 0.198, p < 0.01), search for meaning in life (r = 0.054, p < 0.05), and depression (r = 0.136, p < 0.01). Education was positively correlated with income (r = 0.069, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with working status (r = −0.144, p < 0.01) and religious attitude (r = −0.077, p < 0.01). Income had a positive correlation with working status (r = 0.069, p < 0.01) and the presence of meaning in life (r = 0.069, p < 0.01), and income had a negative relation with religious attitude (r = −0.144, p < 0.01) and depression (r = −0.077, p < 0.01).

Table 3.

Correlations.

Positive associations occurred between working status and religious attitude (r = 0.061, p < 0.05) and the presence of meaning in life (r = 0.059, p < 0.05), and there were negative relations between working status and search for meaning in life (r = −0.058, p < 0.05) and depression (r = −0.062, p < 0.05). Religious attitude was positively correlated with the presence of meaning in life (r = 0.507, p < 0.05) and the search for meaning in life (r = 0.201, p < 0.05) and negatively correlated with depression (r = −0.287, p < 0.01). The presence of meaning in life had a positive correlation with search for meaning in life (r = 0.434, p < 0.05) and negative with depression (r = −0.673, p < 0.01), and the search for meaning in life had a negative association with depression (r = −0.117, p < 0.01).

4.3. Direct Analyses

In Table 4, the main and interaction associations of independent variables with dependent variables were analyzed. First, the relations between independent variables and PML and SML, which are mediating variables in the model, were tested. Accordingly, in Step 1, religious attitude (B = 0.65, p < 0.001), gender (B = 0.16, p < 0.01), and income (B = 0.14, p < 0.001) had positive relations, and working status (B = −0.17, p < 0.05) had a negative relation with PML. For the other mediating variable, in Step 2, religious attitude (B = 0.24, p < 0.001) and marital status (B = 0.27, p < 0.05) had positive associations, whereas working status (B = −0.19, p < 0.05) had a negative relation with SML. The second aim was to examine the connection of independent variables with the dependent variable depression. In Step 3, religious attitude (B = −0.16, p < 0.001), gender (B = −0.06, p < 0.05), marital status (B = −0.20, p < 0.001), education (B = −0.07, p < 0.01), and income (B = −0.06, p < 0.001) all had negative correlations with depression.

Table 4.

Direct and interaction analyses.

In Step 4, which is the last step related to direct relations, the associations of all independent and mediator variables with the dependent variable were analyzed. Accordingly, religious attitude (B = 0.04, p < 0.01), SML (B = 0.10, p < 0.001), and marital status had positive correlations (B = 0.11, p < 0.001) and PMOL (B = −0.33, p < 0.001), whereas education had negative associations (B = −0.06, p < 0.001) with depression. The interaction analysis found a significant negative relation (B = −0.29, p < 0.01) of the interaction variable, which consists of the multiplication of RA and MS variables, with PML.

4.4. Indirect Analyses

The outcomes of the mediation analysis are displayed in Table 5. However, to better understand the indirect relations, the direct associations shown in Table 3 should be evaluated. A significant connection of religious attitude with both PML and SML was detected. Likewise, the correlation of PML and SML with depression was also found to be significant. Therefore, it was understood that PML and SML, which are mediating variables, had significant relations with both independent and dependent variables, and there were significant mediating roles. Following that, an indirect analysis was carried out to find the mediating associations. According to the mediation analysis results shown in Table 5, a significant mediation correlation was found in the relations of religious attitudes with depression through PML (γ = −0.2166, SE = 0.0127, 95% CI [−0.242, −0.1922]) and SML (γ = 0.0236, SE = 0.0042, 95% CI [0.016, 0.0326]) mediator variables.

Table 5.

Total, direct, and indirect regression analysis on depression.

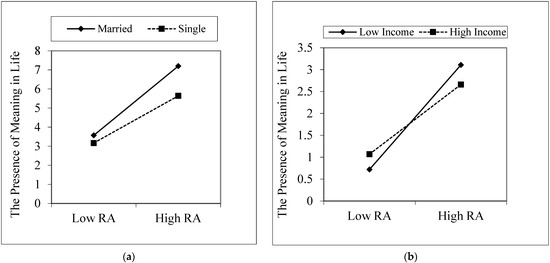

4.5. Interaction Analysis

In the study, moderation analysis was conducted to determine the moderator role of marital status and income status in the relations of religious attitudes with the mediating variables, the presence of meaning in life, and the search for meaning in life. For this purpose, a new interaction variable was created by multiplying religious attitudes with marital status (RA×MS) and income (RA×Income). As a result of the moderation analysis made with Model 7 in Process Macro, a moderator role of marital status in the associations of religious attitudes with the presence of meaning in life was found (B = −0.29, p < 0.01), whereas it was not seen in the association of religious attitudes on the search for meaning in life (B = −0.09, p > 0.05). According to the results of the interaction role, as seen in Figure 2a, it was understood that religious attitudes have positive correlations with the presence of meaning in life more in married people than in singles. In addition, it was determined that the income of individuals has a significant moderator role in the relationship between religious attitudes and the presence of meaning in life (B = −0.050, p < 0.05). However, the moderation role of income was not seen in the associations of religious attitudes with the search for meaning in life (B = −0.012, p > 0.05). Accordingly, as religious attitudes increase, the presence of meaning in life increases more among those with low incomes than those with high incomes, as seen in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

Interaction effects of RA and Marital St. on PML (a) and RA and Income St. on PML (b).

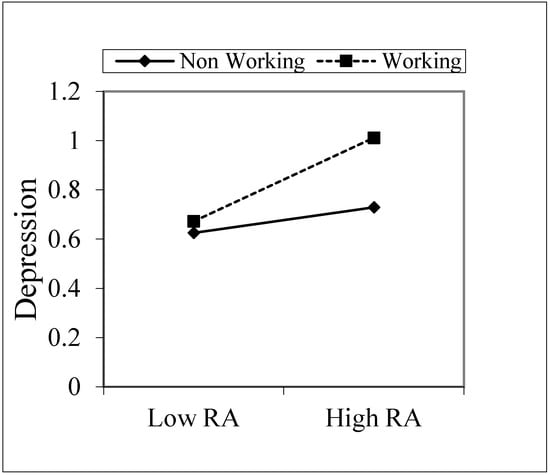

In order to understand how the working status of the participants has a moderator role in the relationship between religious attitudes and depression, an interaction variable with religious attitudes and working status was created (RA×WS). As a result of the moderation analysis carried out, it was understood that working status had a moderation role in the relationship between religious attitudes and depression (B = 0.059, p < 0.05). According to this result, it was determined that, as the religious attitudes increased, the depression of those are working increased more than those who are non-working, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Moderation role of working St. between RA and depression.

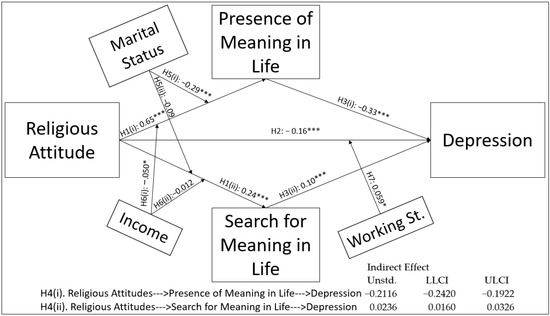

4.6. The Outcomes of the Suggested Model and Hypotheses

After performing the correlation, direct, mediation, and interaction analyses using the factors in Figure 1, which was shown as the conceptual model of the research, the coefficients and significance values shown in Figure 2 were obtained. The effect’s direction is shown by the direction of the arrow on the line connecting the two variables, the values above the arrow indicate the magnitude and direction of the impact, and the asterisks indicate the significance levels. Mediation hypotheses were shown at the bottom in Figure 2, and the LLCI and ULCI values show the magnitude and significance of the indirect relations. In addition, two separate hypotheses showing the moderator role of marital status were also presented. As seen in Figure 2, it was seen that only H5(ii) was not significant.

In the scheme shown in Figure 1, direct, mediator, and moderator hypotheses were tested. The results and significance values of the hypotheses obtained from the tests are shown in Figure 4, and the analysis results are listed in Table 6. According to the results, all hypotheses except H5(ii) were supported. All evaluations were made in the discussion section based on the hypothesis results.

Figure 4.

Hypothesis values of proposed model (*** p < 0.001, * p < 0.05).

Table 6.

Test results of hypotheses.

5. Discussion

A human is an entity with biological, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions (Saad et al. 2017; Bogue et al. 2019; Felicilda-Reynaldo et al. 2019; Marks 2005). In this sense, the health of individuals should be evaluated from a holistic perspective. The physical and psychological health of today’s modern societies is gradually deteriorating due to unhealthy urbanization, decreasing family support, increasing individualization and loneliness, and technology addiction. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the inability of individuals to go out, go to work and school, meet their friends and relatives, be unemployed, and fear losing their income has led to serious psychological problems. While these problems reduce the interest in spiritual and religious values in some individuals, they also increase their orientation toward spiritual and religious values in a large part of them. At the same time, it is seen from the research that religion and spirituality come into play in difficult times as coping mechanisms in difficult times.

This study tried to examine how religious attitudes associated with the psychological problems of individuals, such as depression. It was determined that meaning in life, which was used as another variable in the study, had a mediating role in the relation of religious attitudes with depression. In other words, when a question is asked about how religious attitudes have a negative relationship with depression, it is understood that the answer is provided by establishing a positive association of religious attitudes with meaning in life. In short, religious attitudes establish their negative relationship with depression through positive association with meaning in life. In this study, it was determined that the changes in the model, including the mediator variables of meaning in life, explained 50% of the total change in depression, as seen in Table 4 and Step 4. It is understood that religion has a protective role and strengthens the coping mechanisms of individuals with the difficulties and challenges encountered by adding meaning to life in struggling with the difficulties of life.

The present study found that religious attitudes have a negative association with depression and a positive connection with meaning in life, and meaning in life is negatively related to depression. Meaning in life had a mediating role in the relationship between religious attitudes and depression. In addition, it was determined that marital status had a moderator role between religious attitudes and the presence of meaning in life, but marital status did not have a moderator role between religious attitudes and the search for meaning in life. Gender, age, marital status, education, income level, and working status variables were used as control variables in the study. As a result of the tests of the hypotheses, all hypotheses were supported except for the H5(ii) hypothesis. The direct, indirect, and moderator hypotheses obtained from the study were discussed separately below.

5.1. Direct Relations

In the study, the H1(i) and H1(ii) hypotheses assumed that there is a positive relationship between religious attitudes and the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life. Both hypotheses were supported. However, it was understood that the relationship between religious attitudes and the presence of meaning in life is much stronger than its relationship with the search for meaning in life. These two factors can obtain different values because the presence of meaning in life entails how people consider their current life essential and meaningful. In contrast, the search for meaning in life refers to the view of the search for the comprehension of meaning in life (Dursun 2012; Fullerton et al. 2021; Martela and Steger 2016; Chen et al. 2021). The presence of meaning in life provides individuals with a positive solution and a sense of purpose beyond the ordinary of life, whereas the search for meaning in life can give a more negative dynamic and challenging life (Newman et al. 2018; Steger et al. 2006; Linley and Joseph 2011; Martela and Steger 2016). The relationship between religious attitudes and the search for meaning in life has been weak, as the search for meaning in life is a more difficult, troublesome, and perhaps longer process than the presence of meaning in life. Therefore, it is normal to have this different result. Similarly, the existence of a relationship between religious attitudes and meaning in life is common in the current literature (Fry 2010; Hupkens et al. 2018; Wilchek-Aviad and Ne’eman-Haviv 2016; Yıldırım et al. 2021).

The H2 hypothesis regarding the associations between religious attitudes and depression was supported in the study. Accordingly, it is understood that there was a negative relationship between religious attitudes and depression. In a way, it is seen that religious attitudes reduce depression because religion strengthens individuals as a cope-up mechanism in the fight against problems and leads to a decrease in psychological issues. Religion and spirituality have had a healing effect on the worsened psychology of individuals, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, when individuals faced many troubles and felt closer to death. Many studies from the current literature support this result in the study (Yang and Fry 2018; Koçak 2021b; Reutter and Bigatti 2014; Hart and Koenig 2020; Paukert et al. 2009; Thomas and Barbato 2020; Dein et al. 2020; Fruehwirth et al. 2019; Braam and Koenig 2019; Van de Velde et al. 2017). However, some studies have shown that religious struggle can have positive relations with depression. In this study, when multiple regression analysis was performed together with the sub-factors of meaning in life, it was seen that religious attitudes had positive relations with depression. As a result of the hierarchical regression analysis, when the PML was included in the model, it was seen that the relationship between RA and depression was negative. However, in the next analysis, it was determined that the relationship between RA and depression changed positively when SML was added to the model. This result is suitable for the literature because the search for meaning in life (SML) can bring a more negative dynamic and active life (Newman et al. 2018; Steger et al. 2006; Linley and Joseph 2011; Chen et al. 2021; Emmons 2004; Bodner et al. 2014; Braam and Koenig 2019).

The problems and challenges experienced will cause individuals to question the existing situation. The role of the meaning in life that individuals have in the process of cognitive adaptation to the problematic situation will be influential. In fact, the realization of a meaning in life will affect the individual’s view of life. In the study, the H3(i) and H3(ii) hypotheses, in which the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life are assumed to be associated with depression, were supported. However, while the presence of meaning in life was negatively associated with depression, the search for meaning in life was positive. While the presence of meaning in life leads to a more positive approach and behavior in the individual, it also has a negative relation with the depression of individuals. Due to the absence or lack of meaning in life, the tendency of individuals to use alcohol and drugs increases, and they may attempt suicide (Glaw et al. 2016; Dunn and O’Brien 2009; Steger et al. 2009; Bodner et al. 2014). However, the search for meaning in life will push the individual to an unusual search in his life, possibly leading to a more negative, dynamic, and active life (Newman et al. 2018; Steger et al. 2006; Linley and Joseph 2011; Chen et al. 2021). The search for meaning in life expresses the effort to create or increase the goals and understanding of meaning in life (Chen et al. 2021; Huo et al. 2021). Therefore, the search for meaning in life can have a positive association with the depression of individuals further. In accordance with the literature, in the present study, a negative relationship of age with the search for meaning in life and a positive relationship with the presence of meaning in life were found. The search for meaning in life leads to healthier behaviors in adolescents (Brassai et al. 2017; Steger and Kashdan 2006; Dulaney et al. 2018), and if meaning in life is not strong in the individual, it is seen that it predicts low subjective well-being (Cohen and Cairns 2012; Dulaney et al. 2018; Li et al. 2021).

5.2. Indirect Relations

In the study, hypotheses H4(i) and H4(ii), which assume that the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life have a mediating role between religious attitudes and depression, were supported. However, the mediating role of the presence of meaning in life (PML) in this relationship was negative, while the search for meaning in life (SML) was found to be positive. In this mediation analysis, the different associations of PML and SML are clearly understood. Although religious attitudes are positively related to SML, it is understood that SML is positively associated with depression, unlike PML. There are generally similar results in the literature (Huo et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2021; Emmons 2004; Huo et al. 2021; Li et al. 2021). However, since PML has a negative mediation role, it is understood that it is negatively related to depression. Therefore, it was found that PML and SML have different mediating roles in the correlations of religious attitudes with depression, as expected.

5.3. Moderator Relations

In the study, only the H5(i) hypothesis was supported among hypotheses H5(i) and H5(ii), which were assumed to have a moderator role of individuals’ marital status in the associations of religious attitudes with the presence of meaning in life and the search for meaning in life. Marriage is a phenomenon that increases the responsibilities of individuals. Religiosity increases not only individuals’ responsibilities but also the meaning in life and, therefore, the positive approach towards marriage (Fard et al. 2013; Orathinkal and Vansteenwegen 2006). In addition, religiosity strengthens the spirituality and coping mechanism in individuals, supports the relations between married couples, offers alternatives for solving the problems between them, and thus contributes to longer-term marriages (Itzick et al. 2016; Redekopp 1990; Skrabski et al. 2005; Krause and Rainville 2020; Fard et al. 2013; Orathinkal and Vansteenwegen 2006; Himawan et al. 2018; Wolfinger and Wilcox 2008).

In the study, the H6(i) and H7 hypotheses were supported, whereas H6(ii) was not supported. It was understood that income moderates the relationship between religious attitudes and the presence of meaning in life. As a result, as religious attitudes improve, the presence of meaning in life rises more among low-income people than among high-income people. The literature shows a negative relationship between income and religious attitudes (Kilbourne et al. 2009; Aranda 2008; Chan and Sun 2020; Patel et al. 2018; Garrison et al. 2008; Zimmerman and Katon 2005). Possibly, low-income groups turn to religion because of the problems they experience, and therefore, they attribute a meaning to life (Modell and Kardia 2020; Maliski et al. 2010; Sisselman-Borgia et al. 2018). This study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic period. It was understood that the psychological problems of individuals increased due to problems such as not being able to go out, not socializing, and not being able to go to school and work during this period (Mumtaz et al. 2021; Koçak et al. 2021; Hamouche 2020; Zhang et al. 2020). Working individuals especially experienced the fear of losing their current job. In this sense, in the current study, it was seen that the relationship between religious attitudes and depression was very strong in those already working. In the literature, it has been found that individuals have a similar fear of losing their jobs, especially during the COVID-19 period, which positively predicts their depression (Anderson and Winefield 2011; Dooley et al. 2000; Yoo et al. 2016).

5.4. Evaluation of the Research Question

In the introduction part of the present study, “a question of how the relations of religious attitudes with depression occurs” was asked. First of all, it was determined that religious attitudes had a negative relationship with depression. In addition, as a result of the mediation analysis on this negative relationship, it was determined that religious attitudes have a negative relationship with depression through their positive relationship with meaning in life. Therefore, a strong mediating effect of meaning in life was identified. However, in the multiple regression analysis, it was understood that the search for meaning in life, one of the sub-factors of meaning in life, had a positive relationship with depression, unlike the presence of meaning in life. The fact that the search for meaning in life is positively associated with depression is likely due to the fact that the search for meaning in life is more inquisitive and challenging. Since searching is a laborious, tiring, and uncertain process, it is possible that the search for meaning in the life of individuals has a positive relationship with their depression.

In addition, the moderator effects of the participants’ marriage, income, and working status were tested in the current study. It was understood that marital status and income status have moderator roles in the relationship between religious attitudes and the presence of meaning in life. According to moderating results, religious attitudes have positive correlations with the presence of meaning in life more in married people than in singles. In addition, it was observed that the relationship between religious attitudes and the presence of meaning in life was more positive in those with low-income status than those with high-income status. Furthermore, in the moderator analysis performed with working status, it was determined that the relationship between religious attitudes and depression was more positive in working status than in non-working status. Therefore, the presence of meaning in life is stronger in married and low-income groups, which can be explained by the fact that these groups have more responsibilities in life. It is possible that depression is stronger in employees than in non-workers, both because of their fear of losing their job during the COVID-19 period and because of the responsibilities they have that push them to work.

6. Study Limitations

When analyzing the findings, it is important to take into account the fact that the current study was cross-sectional. Since the survey was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not possible to conduct face-to-face interviews. Therefore, we had to conduct an online survey. Since the duration was limited to the survey, it was impossible to understand the participants’ thoughts and emotional reactions. In addition, due to problems such as physical distance and the risk of transmission of COVID-19, only a specific age range between 18 and 30 could be reached. Therefore, the analysis results cannot be generalized to all segments of society. As the study is limited to the COVID-19 period only, comparisons cannot be made with the period before and after COVID-19. Furthermore, the research was carried out only in Turkish society and cannot be generalized to other societies. Because linear regression analysis was performed in the study, more structural equation analyses (SEM) will be used in future studies to obtain new findings.

7. Conclusions and Implications

While today’s social problems increase the stress and depression of individuals in society, they especially worry young people about the future. While social problems such as the COVID-19 pandemic trigger other problems, physical and mental illnesses spread more. In addition to the fear of not being able to go to school and work, fear of being fired, not being able to obtain enough education, not being able to be employed in today’s daily life, and not being able to pursue a career, especially thanks to COVID-19 restrictions, the stress, anxiety, and depression of young and middle-aged individuals have increased. In this sense, in many studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic period, it has been understood that religion and spirituality positively affect people’s ability to cope with reducing stress, anxiety, and depression. In many studies conducted before COVID-19, it has been revealed that there are negative relationships between religiosity and mental issues, death anxiety, and suicidal symptoms.

Similarly, in this study, it was found that religious attitudes had negative associations with depression in the COVID-19 period. Religious attitudes were found to have positive associations with meaning in life. In addition, it was understood that meaning in life has a mediating role in the relationship between religious attitudes and depression. However, it was found that depression had negative relations with the presence of meaning in life and positive relations with the search for meaning in life, which are the sub-factors of meaning in life. In addition, it was determined that the relations of religious attitudes with the presence of meaning in the lives of married people is higher than in that of singles. It was understood that religious attitudes have an important function, especially due to the problems experienced by low-income groups, and that religious attitudes have more positive associations with the meaning of life than high-income groups. According to the findings of the research, religious attitudes support individuals making a better sense of life during their distressing periods while having negative associations with the problems they experience, such as depression.

It is important for policymakers to update micro and macro policies for better learning, understanding, and living with religion in the family, school, and civil society from childhood. Thus, many mental problems will not arise with protective and preventive approaches, which are applied to decrease the burden of health problems and associated risk factors and consequently will contribute to the health of society. Religious attitudes are generally effective throughout the lives of individuals if they are brought into the lives of individuals at the earliest ages in the family and in school. For this reason, the policies of policymakers to encourage religious attitudes toward children in the family and school will be the most basic protective and preventive approach. Therefore, researchers should be able to conduct new studies and develop more up-to-date theories by including different mediator variables, such as the effect of online technologies, family, friends, and school life on the relationship between religion and psychological problems, during further research.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of anonymous information of individuals.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed M. 2010a. Neither Altruistic Suicide, nor Terrorism but Martyrdom: A Muslim Perspective. Archives of Suicide Research 8: 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Khalek, Ahmed M. 2010b. Religiosity, Subjective Well-Being, Self-Esteem, and Anxiety among Kuwaiti Muslim Adolescents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 14: 129–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, Ahmet, and İbrahim Taş. 2015. Meaning in Life Questionnaire: A Study of Validity and Reliability. Turkish Studies 10: 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos. 2017. Amos, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Armonk: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Sarah, and Anthony H. Winefield. 2011. The Impact of Underemployment on Psychological Health, Physical Health, and Work Attitudes. In Underemployment. New York: Springer, pp. 165–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, Maria P. 2008. Relationship between Religious Involvement and Psychological Well-Being: A Social Justice Perspective. Health & Social Work 33: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, Gökmen, Murat Yıldırım, Zeynep Karataş, Zekavet Kabasakal, and Mustafa Kılınç. 2022. Meaningful Living to Promote Complete Mental Health Among University Students in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 20: 930–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, Hana, Thomas Mulligan, Sylvia Gheorghiu, and Carlos Reyes-Ortiz. 1999. Religious Activity Improves Life Satisfaction for Some Physicians and Older Patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 47: 453–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamonti, Patricia, Sarah Lombardi, Paul R. Duberstein, Deborah A. King, and Kimberly A. Van Orden. 2015. Spirituality Attenuates the Association between Depression Symptom Severity and Meaning in Life. Aging & Mental Health 20: 494–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, Roy F., Kathleen D. Vohs, Jennifer L. Aaker, and Emily N. Garbinsky. 2013. Some Key Differences between a Happy Life and a Meaningful Life. The Journal of Positive Psychology 8: 505–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, Ehud, Yoav S. Bergman, and Sara Cohen-Fridel. 2014. Do Attachment Styles Affect the Presence and Search for Meaning in Life? Journal of Happiness Studies 15: 1041–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogue, Richard J., Being Human, and Richard J. Bogue. 2019. A Philosophical Rationale for a Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual Approach to Wellbeing. In Transforming the Heart of Practice. Cham: Springer, pp. 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braam, Arjan W., and Harold G. Koenig. 2019. Religion, Spirituality and Depression in Prospective Studies: A Systematic Review. Journal of Affective Disorders 257: 428–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassai, Lászĺo, Bettina F. Piko, and Michael F. Steger. 2017. Existential Attitudes and Eastern European Adolescents’ Problem and Health Behaviors: Highlighting the Role of the Search for Meaning in Life. The Psychological Record 62: 719–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Ho Wai Queenie, and Chui Fun Rachel Sun. 2020. Irrational Beliefs, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among University Students in Hong Kong. Journal of American College Health 69: 827–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Qian, Xin Qiang Wang, Xiao Xin He, Li Jun Ji, Ming Fan Liu, and Bao Juan Ye. 2021. The Relationship between Search for Meaning in Life and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety: Key Roles of the Presence of Meaning in Life and Life Events among Chinese Adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders 282: 545–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Karen, and David Cairns. 2012. Is Searching for Meaning in Life Associated with Reduced Subjective Well-Being? Confirmation and Possible Moderators. Journal of Happiness Studies 13: 313–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Adam B., John D. Pierce, Jacqueline Chambers, Rachel Meade, Benjamin J. Gorvine, and Harold G. Koenig. 2005. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Religiosity, Belief in the Afterlife, Death Anxiety, and Life Satisfaction in Young Catholics and Protestants. Journal of Research in Personality 39: 307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, David J., Jasmine Fardouly, and Ronald M. Rapee. 2022. The Effect of Spirituality on Mood: Mediation by Self-Esteem, Social Support, and Meaning in Life. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 228–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, Jeremy F. 2014. Moderation in Management Research: What, Why, When, and How. Journal of Business and Psychology 29: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFranza, David, Mike Lindow, Kevin Harrison, Arul Mishra, and Himanshu Mishra. 2021. Religion and Reactance to COVID-19 Mitigation Guidelines. American Psychologist 76: 744–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dein, Simon, Kate Loewenthal, Christopher Alan Lewis, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2020. COVID-19, Mental Health and Religion: An Agenda for Future Research. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 23: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervic, Kanita, Maria A. Oquendo, Michael F. Grunebaum, Steve Ellis, Ainsley K. Burke, and J. John Mann. 2004. Religious Affiliation and Suicide Attempt. American Journal of Psychiatry 161: 2303–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devogler, Karen L., and Peter Ebersole. 2016. Categorization of College Students’ Meaning of Life. Psychological Reports 46: 387–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Louis Tay, and David G. Myers. 2011. The Religion Paradox: If Religion Makes People Happy, Why Are so Many Dropping Out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101: 1278–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooley, David, Joann Prause, and Kathleen A. Ham-Rowbottom. 2000. Underemployment and Depression: Longitudinal Relationships. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41: 421–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulaney, Ellen S., Verena Graupmann, Kathryn E. Grant, Emma K. Adam, and Edith Chen. 2018. Taking on the Stress-Depression Link: Meaning as a Resource in Adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 65: 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Marianne G., and Karen M. O’Brien. 2009. Psychological Health and Meaning in Life: Stress, Social Support, and Religious Coping in Latina/Latino Immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 31: 204–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, Pınar. 2012. The Role of Meaning in Life, Optimism, Hope and Coping Styles in Subjective Well-Being. Available online: https://open.metu.edu.tr/handle/11511/22126 (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Eisenbeck, Nikolett, José Antonio Pérez-Escobar, and David F. Carreno. 2021. Meaning-Centered Coping in the Era of COVID-19: Direct and Moderating Effects on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A. 2004. Personal Goals, Life Meaning, and Virtue: Wellsprings of a Positive Life. Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived, 105–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskin, Mehmet, Nazlı Baydar, Mayssah El-Nayal, Nargis Asad, Isa Multazam Noor, Mohsen Rezaeian, Ahmed M. Abdel-Khalek, Fadia Al Buhairan, Hacer Harlak, Motasem Hamdan, and et al. 2020. Associations of Religiosity, Attitudes towards Suicide and Religious Coping with Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts in 11 Muslim Countries. Social Science & Medicine 265: 113390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, Mohammad Khodayari, Rouhollah Shahabi, and Saeid Akbari Zardkhaneh. 2013. Religiosity and Marital Satisfaction. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 82: 307–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicilda-Reynaldo, Rhea Faye D., Jonas Preposi Cruz, Ionna V. Papathanasiou, John C. Helen Shaji, Simon M. Kamau, Kathryn A. Adams, and Glenn Ford D. Valdez. 2019. Quality of Life and the Predictive Roles of Religiosity and Spiritual Coping Among Nursing Students: A Multi-Country Study. Journal of Religion and Health 58: 1573–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, Viktor E. 1963. Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. New York: Washington Square Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, Viktor E. 2005. Der Wille Zum Sinn. 5. Aufl. Huber-Klassiker. Bern: Huber. [Google Scholar]

- Friis, Robert, and G. Nanjundappa. 1986. Diabetes, Depression and Employment Status. Social Science & Medicine 23: 471–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruehwirth, Jane Cooley, Sriya Iyer, and Anwen Zhang. 2019. Religion and Depression in Adolescence. Journal of Political Economy 127: 1178–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, Prem S. 2010. Religious Involvement, Spirituality and Personal Meaning for Life: Existential Predictors of Psychological Wellbeing in Community-Residing and Institutional Care Elders. Aging & Mental Health 4: 375–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, Dayna J., Lisa M. Zhang, and Sabina Kleitman. 2021. An Integrative Process Model of Resilience in an Academic Context: Resilience Resources, Coping Strategies, and Positive Adaptation. PLoS ONE 16: e0246000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, M. E. Betsy, Loren D. Marks, Frances C. Lawrence, and Bonnie Braun. 2008. Religious Beliefs, Faith Community Involvement and Depression: A Study of Rural, Low-Income Mothers. Women & Health 40: 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, Robin E., and Dana Lizardi. 2008. Religion and Suicide. Journal of Religion and Health 48: 332–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, Gabriele, Luigi Isaia Lecca, Federico Alessio, Georgia Libera Finstad, Giorgia Bondanini, Lucrezia Ginevra Lulli, Giulio Arcangeli, and Nicola Mucci. 2020. COVID-19-Related Mental Health Effects in the Workplace: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 7857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaw, Xanthe, Ashley Kable, Michael Hazelton, and Kerry Inder. 2016. Meaning in Life and Meaning of Life in Mental Health Care: An Integrative Literature Review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 38: 243–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grouden, Melissa E., and Paul E. Jose. 2014. How Do Sources of Meaning in Life Vary According to Demographic Factors? New Zealand Journal of Psychology 43: 363–70. [Google Scholar]

- Halman, Loek, and Thorleif Pettersson. 2006. A Decline of Religious Values? In Globalization, Value Change and Generations. Leiden: Brill, pp. 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouche, Salima. 2020. COVID-19 and Employees’ Mental Health: Stressors, Moderators and Agenda for Organizational Actions. Emerald Open Research 2: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Curtis W., and Harold G. Koenig. 2020. Religion and Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 1141–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, Andrew F., and Nicholas J. Rockwood. 2020. Conditional Process Analysis: Concepts, Computation, and Advances in the Modeling of the Contingencies of Mechanisms. American Behavioral Scientist 64: 19–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, Steven J., Travis Proulx, and Kathleen D. Vohs. 2006. The Meaning Maintenance Model: On the Coherence of Social Motivations. Personality and Social Psychology Review 10: 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, Adrienne J., Brienna N. Meffert, Max A. Halvorson, Daniel Blonigen, Christine Timko, and Ruth Cronkite. 2018. Employment Characteristics, Work Environment, and the Course of Depression over 23 Years: Does Employment Help Foster Resilience? Depression and Anxiety 35: 861–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, Julie D., and John R. Crawford. 2005. The Short-Form Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct Validity and Normative Data in a Large Non-Clinical Sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 44: 227–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himawan, Karel Karsten, Matthew Bambling, and Sisira Edirippulige. 2018. What Does It Mean to Be Single in Indonesia? Religiosity, Social Stigma, and Marital Status among Never-Married Indonesian Adults. SAGE Open 8: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2011. The Mediatisation of Religion: Theorising Religion, Media and Social Change. Culture and Religion 12: 119–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Jun Yu, Xin Qiang Wang, Michael F. Steger, Ying Ge, Yin Cheng Wang, Ming Fan Liu, and Bao Juan Ye. 2019. Implicit Meaning in Life: The Assessment and Construct Validity of Implicit Meaning in Life and Relations with Explicit Meaning in Life and Depression. The Journal of Positive Psychology 15: 500–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Jun, Xin Qiang Wang, Ying Ge, Yin Cheng Wang, Xiao Yu Hu, Ming Fan Liu, Li Jun Ji, and Bao Juan Ye. 2021. Chinese College Students’ Ability to Recognize Facial Expressions Based on Their Meaning-in-Life Profiles: An Eye-Tracking Study. Journal of Personality 89: 514–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupkens, Susan, Anja Machielse, Marleen Goumans, and Peter Derkx. 2018. Meaning in Life of Older Persons: An Integrative Literature Review. Nursing Ethics 25: 973–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, Philip, Mark Shevlin, Orla McBride, Jamie Murphy, Thanos Karatzias, Richard P. Bentall, Anton P. Martinez, and Frédérique Vallières. 2020. Anxiety and Depression in the Republic of Ireland during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 142: 249–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics Program. Armonk: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- İshak, Torun. 2012. The Sociology of Religion in Turkey Where Villages Urbanized and Urbans Turned into Village. Manas Journal of Social Studies 1: 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Itzick, Michal, Maya Kagan, and Menachem Ben-Ezra. 2016. Social Worker Characteristics Associated with Perceived Meaning in Life. Journal of Social Work 18: 326–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverach, Lisa, Ross G. Menzies, and Rachel E. Menzies. 2014. Death Anxiety and Its Role in Psychopathology: Reviewing the Status of a Transdiagnostic Construct. Clinical Psychology Review 34: 580–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, Christopher D., and Jeremy Kidwell. 2019. Religion and Social Values for Sustainability. Sustainability Science 14: 1355–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalgı, Mehmet Emin. 2021. COVID-19 Salgınına Yakalanan Kişilerde Dindarlık ve Dinî Başa Çıkma. Marife Turkish Journal of Religious Studies 21: 131–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemir, Fatih. 2020. Bazı Demografik Değişkenler Bağlamında COVID-19 Pandemi Neslinin Dindarlık ve Ölüm Kaygısı İlişkisi Üzerine Ampirik Bir Araştırma. Tokat İlmiyat Dergisi 8: 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenton, Peter. 2019. Turks Examine Their Muslim Devotion after Poll Says Faith Could Be Waning. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2019/02/11/692025584/turks-examine-their-muslim-devotion-after-poll-says-faith-could-be-waning (accessed on 11 February 2019).

- Kilbourne, Barbara, Sherry M. Cummings, and Robert S. Levine. 2009. The Influence of Religiosity on Depression among Low-Income People with Diabetes. Health & Social Work 34: 137–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kımter, Nurten. 2020. COVID-19 Günlerinde Bireylerin Psikolojik Sağlamlık Düzeylerinin Bazı Değişkenler Açısından İncelenmesi. IBAD Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 3: 574–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, Orhan. 2021a. How Does the Sense of Closeness to God Affect Attitudes toward Refugees in Turkey? Multiculturalism and Social Contact as Mediators and National Belonging as Moderator. Religions 12: 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, Orhan. 2021b. How Does Religious Commitment Affect Satisfaction with Life during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Examining Depression, Anxiety, and Stress as Mediators. Religions 12: 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, Orhan. 2021c. Does Emotional Intelligence Increase Satisfaction with Life during COVID-19? The Mediating Role of Depression. Healthcare 9: 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçak, Orhan, Ömer Erdem Koçak, and Mustafa Z. Younis. 2021. The Psychological Consequences of COVID-19 Fear and the Moderator Effects of Individuals’ Underlying Illness and Witnessing Infected Friends and Family. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, Hande, and Berna Güloğlu. 2021. The Role of Uncertainty Tolerance and Meaning in Life on Depression and Anxiety throughout COVID-19 Pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences 179: 110952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, and Gerard Rainville. 2020. Age Differences in Meaning in Life: Exploring the Mediating Role of Social Support. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 88: 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2015. The Role of Meaning in Life Within the Relations of Religious Coping and Psychological Well-Being. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 2292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, Ram, Amit Agrawal, and Manoj Sharma. 2020. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress during COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice 11: 519–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, Ryan E., Maria A. Oquendo, and Barbara Stanley. 2016. Religion and Suicide Risk: A Systematic Review. Archives of Suicide Research 20: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jian Bin, Kai Dou, and Yue Liang. 2021. The Relationship Between Presence of Meaning, Search for Meaning, and Subjective Well-Being: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis Based on the Meaning in Life Questionnaire. Journal of Happiness Studies 22: 467–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Chaeyoon, and Robert D. Putnam. 2010. Religion, Social Networks, and Life Satisfaction. American Sociological Association 75: 914–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Li. 2021. Longitudinal Associations of Meaning in Life and Psychosocial Adjustment to the COVID-19 Outbreak in China. British Journal of Health Psychology 26: 525–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, Linda L. 2020. Gender: Sociological Perspectives, 7th ed. New York: Routledge Books. [Google Scholar]

- Linley, P. Alex, and Stephen Joseph. 2011. Meaning in Life and Posttraumatic Growth. Journal of Loss and Trauma 16: 150–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipowska, Małgorzata, Arkadiusz Modrzejewski, Artur Sawicki, Mai Helmy, Violeta Enea, Taofeng Liu, Bernadetta Izydorczyk, Bartosz M. Radtke, Urszula Sajewicz-Radtke, Dominika Wilczyńska, and et al. 2022. The Role of Religion and Religiosity in Health-Promoting Care for the Body During the Lockdowns Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic in Egypt, Poland and Romania. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 4226–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizardi, Dana, Diane Currier, Hanga Galfalvy, Leo Sher, Ainsley Burke, John Mann, and Maria Oquendo. 2007. Perceived Reasons for Living at Index Hospitalization and Future Suicide Attempt. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 195: 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, Peter F., and Sydney H. Lovibond. 1995. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy 33: 335–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, Kathryn Gin. 2017. Ideas of the Afterlife in American Religion. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliski, Sally L., Sarah E. Connor, Lindsay Williams, and Mark S. Litwin. 2010. Faith Among Low-Income, African American/Black Men Treated for Prostate Cancer. Cancer Nursing 33: 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, Loren. 2005. Religion and Bio-Psycho- Social Health: A Review and Conceptual Model. Journal of Religion and Health 44: 173–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, Frank, and Michael F. Steger. 2016. The Three Meanings of Meaning in Life: Distinguishing Coherence, Purpose, and Significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology 11: 531–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modell, Stephen M., and Sharon L. R. Kardia. 2020. Religion as a Health Promoter During the 2019/2020 COVID Outbreak: View from Detroit. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2243–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Hussin, Nur Atikah, Joan Guàrdia-Olmos, and Anna Liisa Aho. 2018. The Use of Religion in Coping with Grief among Bereaved Malay Muslim Parents. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 21: 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molasso, William R. 2006. Exploring Frankl’s Purpose in Life with College Students. Journal of College and Character 7: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, Francesco, Riccardo Ladini, Ferruccio Biolcati, Antonio M. Chiesi, Giulia Maria Dotti Sani, Simona Guglielmi, Marco Maraffi, Andrea Pedrazzani, Paolo Segatti, and Cristiano Vezzoni. 2021. Searching for Comfort in Religion: Insecurity and Religious Behaviour during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy. European Societies 23: 704–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, Ayesha, Faiza Manzoor, Shaoping Jiang, Mohammad Anisur Rahaman, Alyx Taylor, and Roberta Ferrucci. 2021. COVID-19 and Mental Health: A Study of Stress, Resilience, and Depression among the Older Population in Pakistan. Healthcare 9: 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muruthi, Bertranna A., Savannah S. Young, Jessica Chou, Emily Janes, and Maliha Ibrahim. 2020. ‘We Pray as a Family’: The Role of Religion for Resettled Karen Refugees. Journal of Family Issues 41: 1723–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, Robert A., and David Van Brunt. 2018. Death Anxiety. DYING: Facing the Facts 2018: 49–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, David B., John B. Nezlek, and Todd M. Thrash. 2018. The Dynamics of Searching for Meaning and Presence of Meaning in Daily Life. Journal of Personality 86: 368–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novšak, Rachel, Tina Rahne Mandelj, and Barbara Simonič. 2012. Therapeutic Implications of Religious-Related Emotional Abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 21: 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obschonka, Martin, and Rainer K. Silbereisen. 2015. The Effects of Work-Related Demands Associated with Social and Economic Change on Psychological Well-Being: A Study of Employed and Self-Employed Individuals. Journal of Personnel Psychology 14: 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ok, Üzeyir. 2011. Religious Attitude Scale: Scale Development and Validation. Uluslararası İnsani Bilimler Dergisi 8: 528–49. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, Jonathan R., H. Wallace Goddard, and James P. Marshall. 2013. Relations Among Risk, Religiosity, and Marital Commitment. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy 12: 235–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orathinkal, Jose, and Alfons Vansteenwegen. 2006. Religiosity and Marital Satisfaction. Contemporary Family Therapy 28: 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, Kenneth I., Harold G. Koenig, Nalini Tarakeshwar, and June Hahn. 2004. Religious Coping Methods as Predictors of Psychological, Physical and Spiritual Outcomes among Medically Ill Elderly Patients: A Two-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of Health Psychology 9: 713–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Vikram, Jonathan K. Burns, Monisha Dhingra, Leslie Tarver, Brandon A. Kohrt, and Crick Lund. 2018. Income Inequality and Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association and a Scoping Review of Mechanisms. World Psychiatry 17: 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paukert, Amber L., Laura Phillips, Jeffrey A. Cully, Sheila M. Loboprabhu, James W. Lomax, and Melinda A. Stanley. 2009. Integration of Religion into Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Geriatric Anxiety and Depression. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 15: 103–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirutinsky, Steven, Aaron D. Cherniak, and David H. Rosmarin. 2020. COVID-19, Mental Health, and Religious Coping Among American Orthodox Jews. Journal of Religion and Health 59: 2288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, Detlef. 2015. Varieties of Secularization Theories and Their Indispensable Core. The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory 90: 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redekopp, David Eric Dean. 1990. A Critical Analysis of Issues in the Study of Meaning in Life. Edmonton: University of Alberta Department of Educational Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Reker, Gary T., and Louis C. Woo. 2011. Personal Meaning Orientations and Psychosocial Adaptation in Older Adults. SAGE Open 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reutter, Kirby K., and Silvia M. Bigatti. 2014. Religiosity and Spirituality as Resiliency Resources: Moderation, Mediation, or Moderated Mediation? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 53: 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, Marcelo, Roberta De Medeiros, Amanda Cristina Mosini, Byeongsang Oh, Penelope Klein, David S. Rosenthal, and Albert S. Yeung. 2017. Are We Ready for a True Biopsychosocial–Spiritual Model? The Many Meanings of ‘Spiritual’. Medicines 4: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, Tatjana. 2009. The Sources of Meaning and Meaning in Life Questionnaire (SoMe): Relations to Demographics and Well-Being. The Journal of Positive Psychology 4: 483–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, Tatjana, and Peter Becker. 2006. Personality and Meaning in Life. Personality and Individual Differences 41: 117–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenbaum, Michael, Jürgen Unützer, Daniel McCaffrey, Naihua Duan, Cathy Sherbourne, and Kenneth B. Wells. 2002. The Effects of Primary Care Depression Treatment on Patients’ Clinical Status and Employment. Health Services Research 37: 1145–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezer, Sevgi. 2012. A View to the Subject of the Meaning of Life in Terms of Theoretical and Psychometric Studies. Ankara University Journal of Faculty of Educational Sciences (JFES) 45: 209–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiah, Yung Jong, Frances Chang, Shih Kuang Chiang, I. Mei Lin, and Wai Cheong Carl Tam. 2015. Religion and Health: Anxiety, Religiosity, Meaning of Life and Mental Health. Journal of Religion and Health 54: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şimşir, Zeynep, S. Tuba Boynueğri, and Bülent Dilmaç. 2017. Religion and Spirituality in the Life of Individuals with Paraplegia: Spiritual Journey from Trauma to Spiritual Development. Spiritual Psychology and Counseling 2: 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]