Abstract

This article opens up a new scholarly subfield (royal-assassination-attempt commemoration) within the long-neglected field of annual (especially, provincial) ruler festivities in the nineteenth-century Russian Empire. It does so by subjecting an array of untapped, geographically dispersed sources to a systematic, highly theoretically underwritten analysis. As a result, the article generates many insights into the principles and pathways of pious thought and action of Russian imperial subjects from all walks of life vis-à-vis their monarch. In the process, it provides a methodological template for future studies of the intersections between belief and belonging going into the modern age, not only in Russia, but across the world.

1. Introduction

The purpose of this article is to approach the image of the most charismatic Russian ruler of the nineteenth century from a new angle—by mapping the broad gamut of popular responses to and ceremonial improvisations on the theme of the five unsuccessful attempts on Alexander II’s life.1 It will proceed in the following fashion. First, it will provide an international foil for the multiple attempts on the Russian Emperor’s life by discussing briefly the peculiar contemporary frequency of the practice of ruler assassination. Second, it will situate the present contribution within the existing bodies of relevant literature. Third, it will outline a suitable theoretical framework, consisting of newly designed (expressly for the present topic and context) as well as previously developed (for the Ottoman Empire) components. Fourth, it will provide a biographical sketch pivoted on some milestones of Alexander’s popularity with Russian subjects from all walks of life, leading up to the formation of what can be called a personality cult. Fifth, the main body will provide in-depth analysis of the ritual ramifications of the failed assassination attempts on the Emperor. Finally, the article will explore further expansions of the new sacred matrix, or, more precisely, what can be termed “latitudinal/lateral (intra-ruler)” and “longitudinal (inter-ruler)” commemorative linkages of the assassination attempts across the Russian Empire.

2. Ruler Assassination Attempts in the 19th Century. A Review of Russian Literature. A New Coordinate System (Matrix) of Ruler Sacrality

Whereas the assassination of political leaders is a phenomenon dating back to the beginnings of recorded history, it seems to have become much more frequent and widespread in the mid- to late nineteenth century, with a further spike in the early twentieth century leading up to World War I. If we take the century between the end of the Napoleonic Wars/the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914 and count the attempts, be they successful or not, on the lives of reigning royalty and heirs (crown princes or princesses), acting and former prime ministers, founding father figures, and colonial governors/viceroys globally, then we get the following table (Table 1):2

Table 1.

Approximate number of assassinations and attempts on heads of state globally by decade.

Three decades are particularly noteworthy for the distinct trajectory shifts they bring with them, namely, the 1860s (a sudden and drastic jump), the 1880s (a sharp drop), and the 1900s, as well as the period 1910–1914 (an even steeper rise than before). While seeking the exact reasons for these shifts would be extremely interesting, it would also be very complicated and time-consuming. Therefore, it lies beyond the scope of this article. It suffices to say that the beginnings of an answer have to do with the identity and belief systems of the assassins and their backers, which in turn would point to the rise of anarchism, nationalism, and nihilism from the mid-nineteenth century to the turn of the twentieth century. On the other side of the equation, the rise of what I have termed “modern ruler visibility”3 in the same period made assassination not only more tempting to regime opponents but also more likely to succeed.

In the vast majority of cases, assassination attempts against royalty were followed by brisk investigations and swift, very well-publicized retribution. Needless to say, both of these steps were meant to deter any potential sympathizers from engaging in any such acts in the future. What is indeed counterintuitive, and, to my knowledge, does not take place anywhere, except in Russia, is the memorialization of the assassination attempt itself by way of repeated (annualized) marking of the day it happened to occur on. The main reasons for avoiding the memorialization of assassination attempts would be the natural risk of (both private and public) questioning as to why the assassination attempt was allowed to proceed in the first place and the high potential for an associated perception in the public mind of both collective (regime) and individual (monarchic) weakness. And yet this is precisely what took place in Russia, from 1866 up until, more or less, the Empire’s demise. Moreover, the list of occasions for public commemoration includes not only the six attempts4 on Alexander II’s life but also the attempt on the life of Grand Duke Nicholas (the future Nicholas II) in Japan in 1891,5 and even Alexander III’s survival of a train wreck in 1888.6 This state of affairs opens up at least two complex overarching questions—“why” and “how.” This article will chart an alternating course between them. In the process, it will touch on a number of relevant topics, whose treatment in Russian imperial historiography is rather uneven. On the one hand, scholarship on royal ceremonial in the imperial center, doubtlessly stimulated by Richard Wortman’s seminal two-volume study (1995–2000), is extensive,7; on the other hand, it has not led to a single systematic (supra-regional) study of respective provincial festivities.8 Although there exists a very lively literature inspired by what Konstantin Tsimbaev first called “jubilee culture” (Tsimbaev 2002), then “jubileemania” (Tsimbaev 2005),9 its net is cast very widely—from jubilees concerning town foundations (Moscow, Omsk, Samara), medieval events (state foundation, Christianization), and territorial expansion (Siberia, Georgia), to reforms (Emancipation), battles (Poltava, Sevastopol), wars (1812), to individual literary figures (Pushkin) and so on. In such contexts, the monarch and dynasty come into view only sporadically, often even in passing. Despite a few exceptions, centered on Yuliya Safronova’s work in the history of emotions (Safronova 2010), sociocultural history (Safronova 2014), and religious studies (Safronova 2021),10 the literature on the assassination attempts against Alexander II remains heavily skewed towards sociopolitical (Baranov 2014; Turitsyin 2014), or sociolegal (Filonov et al. 2020) considerations, dealing with the incomplete nature of the emperor’s reforms or the ineffectual (Gogolevskiy and Sergachev 2000) character of his late regime, and above all, with our day and age’s inevitable topic of terrorism11 (or its historically more accurate counterpart—populism).12 Incredibly, despite the existence of copious highly digitized primary sources, a sampling of which will be discussed in great detail shortly, attesting to the enormous (and enormously creative) popular involvement from virtually all parts of the empire, irrespective of settlement size, to the best of my knowledge, there is not a single study of annual local celebrations of Alexander II’s survival of the first five assassination attempts on his life.13 To open up this new field at the intersection of two other well-developed fields focusing on popular piety/lived religion and the symbolic relationship/interaction between Tsar and people is this article’s main goal. In the process, it will explore an entirely uncharted mode of ruler-ruled interaction on the plane of piety and reveal a hitherto unknown, mystical fabric of ruler sacrality in nineteenth-century Russia, composed of interwoven iconographic, architectural, and ritualistic (liturgical) threads, further interlaced with patriotic (local, regional, and imperial) and less often military filaments. This discussion will take place within the following coordinate system of ruler sacrality, which facilitates the fusion of the profound and profane realms:

- (1)

- First Axis: the events of Alexander II’s physical survival of the first five assassination attempts (dates, facts, acts, etc.); a literal, matter-of-fact axis signifying the secular realm;

- (2)

- Second Axis: the open-ended, elite-dominated process of decoding Orthodox Christian saintly protection (the myth of naming, iconography, sacred architecture, etc.); an axis of nascent complexity signifying the object-based, people-free fixity of the sacred realm;

- (3)

- Third Axis: the mystical praxis of Orthodox Christians, subject to ceaseless variation and improvisation, open to other believers (religious rituals); an axis of advanced complexity signifying the subject-based, peopled fluidity of the sacred realm.

As the subsequent analysis will demonstrate, while it began as an unprecedented project of reverse engineering of the Emperor’s survival, over time, it grew along all of its axes and became a new sacred matrix encompassing all.

3. Modern Monarchic Visibility

Before we delve into the intricacies of failed-assassination commemoration, an overview of (a) yet another new conceptual framework facilitating the analysis of central power embodied by the ruler and the changing patterns of its public staging in nineteenth-century Russia and (b) earlier (and prevalent) types of public (secular and mixed) ruler celebration to which the new commemorations were added, may be in order.14 The heart of this type of analysis I originally developed for the Ottoman imperial experience lies in the concept of modern monarchic visibility, which can be subdivided into ruler visibility and dynastic visibility. I define ruler visibility as a combination of direct and indirect elements. The direct elements include the ruler’s physical presence at public ceremonies and the degree of his/her personal exposure to the public gaze. The indirect elements consist of a set of symbolic markers, such as his/her monogram, as well as architectural monuments, such as figural statues, churches, palaces, and tombs, either newly constructed or restored by the ruler. Modern ruler visibility is a composite concept, combining projected traits of personal character with short-term and long-term policy imperatives, both domestically and abroad. It incorporates not only actual bodily comportment and its symbolic dimensions in general, but also the more frequent occurrence of references to and discussions of the ruler’s persona in the press in particular. In the absence of a genuine, consistent, and credible effort on the part of the pre-modern ruler to reach out past elite circles or the confines of the royal capital, as well as due to the lack of a significant periodical press and mass culture to popularize his/her ‘good works’, both the direct and indirect types of ruler visibility were quite limited before the nineteenth century.

The main vehicles of modern ruler visibility in the Russian Empire, as in other contemporary empires, were the systematic, pan-imperial annual public ruler celebrations (especially the royal birthday and accession day, but also the coronation day, the royal name day,15 etc.), which had a widely felt impact at least until the Russian Revolution of 1905. While such celebrations had taken place on a smaller scale and less frequently in the Romanov realm before the nineteenth century, they were entirely transformed—both broadened and intensified—in the aftermath of the ill-fated 1825 Decembrist Revolt against the accession of Nicholas I and in favor of constitutional monarchy.16 Reinforced by technological improvements (telegraph, railways, electricity, etc.) and advances in print media, these proliferating and escalating ceremonial events ushered in a new era of ruler visibility, helping to create a modern public space/sphere and forging credible direct vertical ties of subject loyalty, irrespective of language, location, creed, or class.

By the term “modern public space/sphere” we can designate a process that unfolded on two related levels, both directionally and incidentally, facilitating the creation of social bonds for the average person in the provinces. Starting from a zero point, at which time the ruler had no physical presence and only a minimal symbolic presence outside the imperial capital, it expanded first through the ruler’s tours of the imperial domains—a major, if sporadic, event that helped to jumpstart the phenomenon—and then, in a more significant and lasting manner, through the annual ruler celebrations. Thus, the public space/sphere developed quite literally out of a public, communal place in which the people welcomed the ruler or gathered and organized in groups to celebrate him/her annually, such as in the town/village square or a similarly designated area. By way of regular recurrence, a growing scale, and a rising ritual complexity over time, these celebrations gradually tipped the balance towards a public sphere of wider boundaries of the desirable/permissible/acceptable symbolic interaction between the ruler and the ruled, which ultimately set the stage for a modern type of belonging.17

The second component of monarchic visibility—dynastic visibility—was closely related to the main swing of the reigning monarch’s ruler visibility. We will not concern ourselves much with it in this article.

The rapidly expanding monarchic visibility also facilitated the formation of ruler personality cults. In the context of the Russian autocratic system, the concentration of public attention on the reigning monarch should hardly come as a surprise. In the absence of a parliament, the well-publicized forms of popular infatuation with the ruler became a crucial source of ruler validation and legitimacy until the Russian Revolution of 1905. For the purposes of this article, a ruler personality cult is a set of ritual practices and attendant rhetoric signifying an extreme power/status differential between the celebrant/ruled/subject and the celebrated/ruler/object. Specifically, the cult is channeled through acts of homage related to the object’s body and persona, especially in his/her absence, and involves higher degrees of creative abstraction over time.18 While not a strictly modern phenomenon, ruler personality cults received a major boost from the ongoing processes of centralization of power, the enlargement, acculturation, and homogenization of the imperial public, as well as from infrastructural penetration and technological consolidation, all of which carried recognizably modern features.

4. A Loose Sketch of Alexander II’s Personality Cult

From the very outset of his life, Alexander II benefited from a set of circumstances that cast a favorable light on him in the eyes of the imperial subjects. Upon this foundation, first his parents,19 and then he himself was to build continuously throughout his life. In fact, his eventual personality cult persisted long after his death, until the end of the empire itself, thereby surpassing both in scale and in duration the first such transcendent (posthumous) personality cult (other than Peter I’s)—that of his uncle, Alexander I.20 To begin with, Alexander II was the only royal since 1740 to have been born in Moscow (17 April 1818)—the traditional (and spiritual) capital of Russia. Given that neither of his father (Nicholas)’s two older brothers (Alexander and Constantine) had any sons, this child, Nicholas’s eldest son, was treated from his cradle as a potential heir to the throne. Leading poets, such as Vasiliy Zhukovskiy (1783–1852), who later became Alexander’s tutor, wrote odes on the occasion of his birth.21 Whereas the practice itself was not new, in the aftermath of the Napoleonic wars (1805–1815), which gave birth to a heightened patriotic ethos and a redefined ruler-ruled relationship, new language pervaded these poems. Let us examine the following excerpt from Zhukovskiy’s ode:

Yes, in his exalted sphere he will not forget,The most sacred of callings; to be a human being,To live for posterity in his people’s majesty,For the good of all, his own to forget,Only in the free voice of the fatherland,To read his briefs with humility.22

These six lines are highly significant, coming as they do from a person with close ties to the royal family and the strongest direct influence on the education of the future ruler. They chart an ideal course towards a diminishing distance between the ruler and the ruled,23 whereby the former is willingly parting with his sublime station (“exalted sphere”), with a display of self-negation (“humility”) and dedication (“for the good of all, his own to forget”) to his people, who in turn have risen to royal heights (“people’s majesty”). Already here, two key modes of thought and feeling, which are of central interest to us in this article, set the tone of the ruler-ruled exchange—a religious credo (“the most sacred of callings”) merged with a patriotic credo/secular faith (“the free voice of the fatherland”). It should hardly come as a surprise then that the chapter on Alexander II in Richard Wortman’s original seminal two-volume study of Russian imperial mythology is entitled “the scenario of love.”

Here is a brief but telling sequence of further steppingstones, a list by no means exhaustive but strongly suggestive of the strategy for simultaneous aggrandizement and endearment of Alexander to the public, both at home and abroad. In 1825, on the very day of the Decembrist revolt, Emperor Nicholas I brought out his 8-year-old son and had members of the loyal Sapper Battalion, who had saved the imperial family, hold the boy, kiss his hands and feet, and accept him as the heir to the throne, an unprecedented act in all of Russian history.24 Two years later, in an act of what I have called elsewhere “the myth of naming”,25 a newly discovered rich gold mine in the Southern Ural Mountains (Zlatoustovskiy Okrug) was called “Knyaze-Alexandrovskiy (Grand Duke Alexander’s),” the expectation being that in quality of content and the overall amount of gold, it would be ranked immediately after its “Tsarevo-Aleksandrovskiy (Tsar Alexander’s)” and “Tsarevo-Nikolaevskiy (Tsar Nicholas’s)” counterparts.26 In 1830, this heir had his name day (Aug. 30, St. Alexander Nevsky’s27 feast day) celebrated abroad in Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, with much pomp and circumstance, including fireworks, illuminations, and a 21-gun salute, which to this day is the international standard for reigning royalty.28 Four years later, another newly minted ritual, Alexander’s oath-taking ceremony as heir to the throne, shortly after his sixteenth birthday, was celebrated with a deafening 301-gun salute.29 This ceremonial cannonade surpassed the 201-gun salvo with which his birth, according to custom, had been marked back in 1818.30 In 1837, immediately after his nineteenth birthday, Alexander undertook a tour of the Empire, a tradition to which his father Nicholas had also adhered in his day (1816). In a span of more than seven months, from April to December, the heir, accompanied by his tutor Zhukovskiy and another person, covered a distance of over 13,000 miles.31 It was the longest tour of the empire by a tsar or heir, and took him to regions including parts of Siberia never before visited by a member of the imperial family.32

In sum, it would not be hard to make the case that, except for the immediate context of Alexander’s rise to the throne towards the end of the Crimean War of 1853–1856, which was a humiliating loss to an international alliance, including the Ottomans, Russia’s arch-nemesis, Alexander’s public image, in the eyes of the majority of his subjects,33 was always on an upward trajectory. In fact, it reached new heights on 19 February 1861, a date we will return to, with his decree on the long-awaited liberation of the serfs,34 which earned him the moniker “Tsar-Liberator.”35 The decree was issued on the date of Alexander II’s accession to the throne in 1855, an act of what I call “cross-dating”.36

5. The Assassination Attempts on Alexander II’s Life and Their Ritual Ramifications

The first assassination attempt (pokushenie), by Dmitriy Karakozov, a petty Russian nobleman from the Saratov governorate (present-day Russia), dressed as a peasant, took place on 4 April 186637 in a public park, the Summer Garden, in St. Petersburg. According to official records, the assassin’s revolver missed because a bystander, Ossip Komissarov, an artisan (hatter) from Kostroma, hit his arm and deflected the shot. Karakozov was a member of a secret revolutionary society (“The Organization”) and hoped that the Emperor’s death would inspire a social revolution. For his brave act, Komissarov received a hereditary nobility, the name Komissarov-Kostromskiy, and multiple honorary citizenships (of domestic towns), among a number of other rewards. The fact that he not only came from the district of Kostroma, the birthplace of the Romanov dynasty in 1613 but, allegedly, from a village only 13 km away from the birthplace of Ivan Susanin, a popular hero for allegedly saving the life of the dynasty’s founder, Mikhail Romanov, during the Polish-Lithuanian War that same year, became the first major (secular) symbolic kernel, with multiple ripple effects on the public imagination. In a sense, one could speak of a nascent public cult of Komissarov-Kostromskiy, given the high number of objects and institutions created in his honor and named after him across the vast imperial domains—from a medal, poems, portraits, and monuments to stipends, schools, nursing homes, and so on.

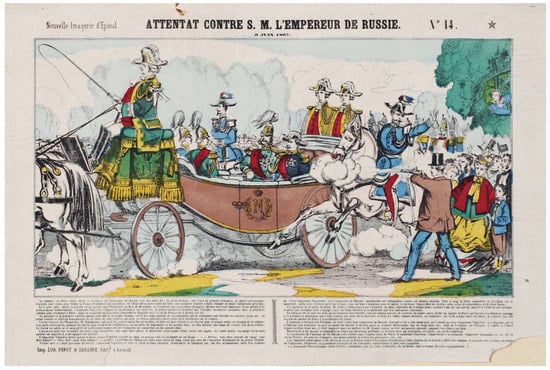

The second assassination attempt, by Antoni Berezowski, the son of a poor nobleman of Polish descent from the Volhynian governorate (present-day northwest Ukraine), took place on 25 May 1867 in a public park (Le bois de Boulogne) in Paris during the Emperor’s visit to the World Exposition (Figure 1). The revolver itself blew up, and the bullet hit a horse of the royal cortege. Before receiving a life sentence, Berezowski admitted that he had acted alone with the goal of avenging Alexander II’s suppression of the Polish Revolt of 1863–1864, in which he himself had participated.

Figure 1.

The 25 May 1867 assassination attempt on the life of Emperor Alexander II (Nouvelle Imaqerie d’Epinal, issue 14, 6 June 1867).

These two events resonated far and wide across the Russian Empire. By 12 April 1866, the editorial office of the leading capital newspaper, Sankt Peterburgskie Vedomosti, had received individual voluntary donations from across the Empire in the amount of 222 rubles and 52 kopeks.38 A temporary wooden chapel was placed on the site, and the foundation for a permanent stone one was laid in the summer of 1866. On 30 August 1867, the chapel was dedicated to St. Alexander Nevsky. Inside, a large image of the saint, painted by Timofey Neff, a member of the Academy of Fine Arts, and placed in a case (kiot) of white marble, was flanked by two crosses formed by gift icons. Other images by another academician, Evgraf Sorokin, included Christ Savior, the Mother of God, and all saints whose feast days fell on 4 April. Later, these images were rendered in mosaics. The chapel was magnificently executed in grey, white, and multicolored marble, as well as labradorite and lapis lazuli, with a roof made of gilded bronze, and the following sign with bronze letters on the front: “Do not touch the Аnointed by Мe (Не прикасайся к Пoмазаннику Мoему)” (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The chapel on the site of the 4 April 1866 assassination attempt in St. Petersburg’s Summer Garden (destroyed in 1930).

This august example from the very site of the shocking, unprecedented event set the frame for countless improvisations all across the provinces. Chapels were constructed or turned into churches; unheated churches were converted into heated ones, and so on, in commemoration of Alexander II’s deliverance (spasenie) by the hand of the Providence. Let us review the following two colorful, though by no means unique, cases of local ceremonial response to the two traumatic events and use them as points of entry into the subject of ruler sacrality in its latest, attempt-on-life-themed iterations.

In the village of Chervlennoraznoe (present-day Chervlennoe) near Tsarytsin (present-day Volgograd, Russia), Saratov governorate, people received the telegram about the 4 April event on the eve of St. George’s feast (23 April) in 1866. Given that it was accompanied by an issue of the local diocesan newspaper that announced the Emperor’s generous order to release 1.5 million silver rubles from the treasury for the benefit of institutions of religious learning, some concluded that his survival was a just reward for his good deeds. Communal prayers and liturgical services of gratitude were followed by discussions led by the head of the local volost’,39 a state peasant from the same village, of ways to memorialize this day by (a) arranging for an icon of Christ Savior to be hung in the altаr of the parish church with a gilded carving with the following words: ”the Tsar’s heart and life are in God’s hands; in memory of … ” and (b) purchasing a portrait of the Emperor for the parish school. To these items, which were unanimously accepted, the congregation added the order of another icon with the images of St. Alexander Nevsky and Mary Magdalene in the center and the Mother of God and St. Nicholas the Wonderworker in the upper left- and right-hand corners, respectively, with a gilded icon case (kiot), to be carried along in all processions of the cross.40 Moreover, on the Sunday following 4 April each year, a prayer service of gratitude with communal genuflection (kolenopreklonenie) was to be performed. Finally, a special address describing these acts was forwarded to the Emperor.41

In the town of Chernigov (Chernihiv in present-day Ukraine), Chernigov governorate, following the 25 May event the next year, a special committee for the construction of a commemorative chapel was formed. The interior was to be graced, in key positions, by the following images: (1) the Ascension of Jesus Christ, in memory of 25 May, (2) St. Alexander Nevsky, and (3) St. Joseph the Hymnographer, in memory of 4 April. In this chapel, images of all the wonder-working icons which had hitherto appeared in the Chernigov governorate—local relics (святыня)—would be placed, as well as images of the most important events of Alexander II’s reign—the emancipation of the serfs (1861), the establishment of the Zemstvo councils42 (1864), and the implementation of the court reform (1866). Moreover, the donors’ names—a list comprising clergy, nobles, and members of the town, peasant, and volost’ societies—would figure on a copper plaque along with a summary of their brief emotional remembrances of 25 May 1867.43

The first, most obvious, and clearly significant yet cryptic element, subject, as we will see, to infinite variation, was iconography. Tracing the identity and meaning of the icons associated with the assassination attempts, as well as their shifting (re-)configurations, would cut to the core of (especially ordinary) people’s lived religion, a main object of study in this article. As Alexander Nevsky was the patron namesake saint of the Emperor, so Mary Magdalene was the patron namesake saint of the Empress (Maria Aleksandrovna), with their feast days (30 August and 22 July) being the respective royal name days, official imperial holidays. Although I have not been able to identify the particular version of the Mother of God icon from the first example,44 both the Virgin Mary and St. Nicholas the Wonderworker45 are widely revered in Eastern Orthodoxy to this day, especially for their protective qualities. Naturally, the same holds for Christ Savior, to whom the Emperor’s survival could also be attributed outright.46 What is more, his icon was explicitly intertwined with the mythology of power in Russia, representing the Petersburg tradition. It was Peter the Great’s favorite icon, accompanying him into battle and in peacetime, hanging in a chapel near his small house on the Neva.47 Not surprisingly, this was the icon the royal family members most often donated to chapels and churches across the provinces thereby closing the feedback loop in the commemorative ruled–ruler exchange. For example, it was a copy of this icon and an unspecified icon of the Mother of God, both decorated with pearls, diamonds, and gilding, which the Heir, Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich (the future Alexander III), gifted to a church under construction in Sedlets (present-day Siedlce in Poland) on 4 December 1866. The list of other notable donors and their icon gifts included the Archbishop of Warsaw (“the Mother of God”), Grand Duchess Alexandra Petrovna (“The Ascension of the Christ”), and the Sedlets governorate police force (“St. Nicholas, the Wonderworker”).48 The church committee itself had arranged for an icon commemorating each of the two failed assassinations—“The Three Saints” and “The Ascension of the Christ,” respectively.49 Within the natural logic of Orthodox believers, the royal survival on those particular dates could be attributed to protection from the saints whose feast days fell on them. Hence, pious gratitude was owed to them. Although the identity of the three saints is never explicitly revealed in the sources I have consulted, two strong candidates, based on their frequent individual appearances on commemorative icons, are St. Joseph the Hymnographer and St. George of Mount Maleon, whose feast days fell on 4 April. It is possible that the third figure is the Virgin Mary herself, since one of her many icons (Mother of God Gerontissa) was also feted on 4 April. To date, I have not been able to ascertain a link between the standard icons of saintly triads50 and the ceremonial aftermath of the assassination attempts. The religious feast of the Ascension of the Christ, on the other hand, whose marking shifted from year to year since the date had to fall on the fortieth day after Easter, a Thursday, happened to fall on 25 May in 1867. Hence, it became forever etched on the minds of believers, in a case of what one might call a “spontaneous/natural cross-dating” and was memorialized by them in myriad ways for many years thereafter.

The pious mode of thinking of royal (tsarskie) days in terms of the saints presiding over them, which had its natural root in the royal name day, then spread to the assassination-attempt days, absorbed the royal accession day as well. Since the feast of St. Arhipp (and his father, St. Philimon), fell on 19 February, his image was also included in icon arrangements in memory of the failed attempts. A couple of examples from the Herson governorate (present-day Ukraine) alone include the icon initiative of parishioners from the large village (mestechko) Semenistyiy in 1867 in memory of 4 April (code: St. Joseph the Hymnographer)51 and another one by state peasants in the town of Novomirgorod in 1868 in memory of both dates (code: St. Joseph and Christ Savior). In the latter case, the Holy Synod52 notified the Emperor, who responded in writing as follows: “To be thanked.”53 Thus, the symbolism of the 19 February date became even more intense, operating as it did on three levels—two secular and one sacred.

In the process of sifting through ceremonial reports from various corners of the Russian Empire, one comes across ever more new constellations of saints, both in single icons and in entire iconostases. Some congregations went to great lengths to pay homage to the saints of particular pokushenie dates. As with 4 April, so with 25 May, a trinity of saints was improvised. Thus, three of the five icons in a wooden (carved and gilded) cross in the iconostasis of a chapel erected in St. Petersburg in 1869 in memory of 25 May contained images of scenes and saints feted on that date—“The Ascension,” already familiar to the reader, along with “The (Third) Acquisition of John the Baptist’s Head,” and ”The Holy Martyr, St. Therapont [of Cyprus].”54 In fact, there may have been unspoken expectations and perhaps even pressure on parish churches that happened to be dedicated to one such saint or scene to do more than their average peers. Such was probably the case with the Ascension church in the village of Petrovskoe, Poltava governorate (present-day Noviy Tagamlik in the Ukraine), given what its churchgoers did. In 1867, two years after erecting the church itself, they set the foundation stone (zakladka) of an adjacent chapel dedicated to the two attempts. It took some time to collect the necessary funds, by voluntary donation, but in 1874 it was consecrated with much pomp and circumstance.55 Its dark oak iconostasis, ordered all the way from the capital, displayed five life-size icons on golden backgrounds, separated by carved wooden columns, effectively forming icon cases, each bearing a sign of its icon’s dedication and an appropriate quote from the scriptures. Naturally, the Ascension icon took pride of place, with the two 4 April saints on its immediate right and St. Alexander Nevsky on its immediate left. The extreme right went to St. Arhipp and St. Philimon, with the double secular significance of the 19 Feb. date explicitly acknowledged. The extreme left was devoted to a new figure, St. Panteleimon the Healer, allegedly in honor of the Empress’s name day, 27 June. One hopes this was a journalist’s (double) mistake and not one in the physical since this saint’s feast day falls, in fact, on 27 July, which happened to be the Empress’s birthday.56 One way or another, this saint’s image marks a further step, after the royal name days and the accession day, in the process of the interweaving of secular and sacred meanings, all tied to the ruler or his consort, all under the pretext of the two assassination attempts.57 Before developing the theme of day/saint/scene/icon multiplication and reconfiguration any further, a few words on the next three assassination attempts, which added more fuel to the ritual fire, are in order.

These pokushenia came in rapid succession, more than a decade after the first two. On 2 April 1879 (Easter Monday), Alexander Solovyev, the son of a low-level civil servant and a member of the society “Earth and Will,” i.e., a Russian narodnik,58 shot five times at the Emperor during his habitual walk in the vicinity of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, with all the bullets missing their target. The next two (as was ultimately the successful one in 1881) were organized by the successor of “Earth and Will”, “The People’s Will (Narodnaya Volya)”, an openly terrorist revolutionary populist organization. The first attempt involved the explosion of the train by which the Emperor was expected to return from his summer residence in the Crimea. The event took place on 19 November 1879, near Moscow, but the emperor survived since the explosion hit the train carrying the retinue rather than the royal one. No one died.

The last unsuccessful attempt, on 5 February 1880, was also by way of a massive explosion, this time in the basement two floors below the dining room where Alexander II was supposed to have dinner in the Winter Palace. It was carried out by Stepan Halturin, a worker and member of the “People’s Will” who had earlier taken up a job as a carpenter in the palace service. Due to an unforeseen delay in his schedule that day, the Emperor survived. However, eleven soldiers of the Life Guard’s Finnish Regiment who were on duty in the guardroom above the basement died and 56 soldiers were wounded.

These three events, in combination with the twenty-fifth anniversary of Alexander II‘s accession to the throne (19 February 1880), opened up a range of new possibilities in terms of sacred ritual improvisation and respective icon combination. For example, already in late January 1880, а convention of Tula Diocese clergy deliberated on the composition and placement in the cathedral of Tula (in present-day Russia) of “such an icon, which in the inerasable memory of all posterity would depict the wondrous ways of God’s Providence manifested in the life of our Most Devout Master59 Emperor.” Eventually, it was decided that the main icon would be of St. Alexander Nevsky, surrounded on both sides by the following eight smaller icons separated by bezels of hammered gilded silver: (1) the Vladimir icon of the Mother of God (feted on Coronation Day, 26 August); (2) Apostle Arhipp; (3) St. Simeon of Persia (feted on the royal birthday, 17 April); (4) Holy Martyrs Adrianna and Natalie (26 August); (5) the “Recovery of the Dead” icon of the Mother of God (5 February 1880); (6) St. Joseph the Hymnographer; (7) St. Titus the Wonderworker (2 April 1879), and (8) St. Ioasaph and St. Varlaam (19 November 1879). Above them all would be the Ascension icon.60

Similar icon configurations and attendant rhetoric can be found in much smaller and much more remote locales across the Empire. Аn almost identical list of saints’ icons, including all whose feasts fell on “those five days in which God manifested his mercy to the Anointed One,” played out in the Trinity Church on the Sot’ River in Lyubimskiy County (uezd), Yaroslavl governorate (present-day Russia).61 The very same page of the diocese newspaper describing this arrangement also contains another icon-centered report from a neighboring county, which is well worth the reader’s attention. It concerns the acquisition of an icon of the Iberian Mother of God in memory of 19 November for the stone chapel of the Resurrection (Voskresenie) church in the village of Vyatsk, Danilovskiy uezd. Apparently, this was the unanimous decision of peasants from various hamlets (seleniya) of Vyatsk volost, who were “permeated by a burning feeling of devotion to the Master Emperor.” On 13 October 1880, as the local priest D. Korzlinskiy had reported in a previous issue, upon the completion of liturgy, a joint service with two other Vyatsk priests, as well as a prayer singing (molebstvenno penie) before the icon, the Iberian Mother of God was carried in ritual transfer from the Resurrection church to its chapel, where after another prayer service with the sprinkling of holy water (vodosvyatie), it was laid in its appointed place. This entire episode can be used as a rare window into the bygone world of common contemporary Russian Orthodox thought, imagination, and mystical praxis. The keys to solving the puzzle are: (1) that the 19 November “villainous attempt” occurred near Moscow and (2) that Vyatsk happened to have a church by the name of Resurrection. From these two basic threads, the whole intensely emotional multi-modal ritual was spun. Apparently, someone made a connection between the Resurrection church of Vyatsk and the Resurrection Gate of the Moscow Kremlin, which happened to house a chapel containing, since the seventeenth century, the much-venerated Russian icon of the Iberian Mother of God. Out of the several possible feast days of this icon, precisely the day associated with its ritual transfer to Moscow—13 October—was fixed for the new Vyatsk icon transfer ceremony. So, in a way, the whole pilgrimage to Moscow for the purpose of paying obeisance to the Iberian Mother of God was recreated in Vyatsk and relived by the local devout Christians, with the added dimension of the Emperor’s fortuitous occasion. It would probably not be an exaggeration to call the culmination of this religiopatriotic experience a belonging of the most intense and intimate nature, a case of a mystical parallelism or a pious equivalence/vicarious piety—as in Moscow, so in Vyatsk (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The Volost’ administration building in the village of Vyatsk in the early 1900s. In front, a monument to Emperor Alexander II is clearly visible. Today, it has been reconstructed.

Many congregations in other locales across the vast Empire did not have to conjure up the image of the Emperor in the abstract using the assassination attempts as a bridge but instead connected with him and the royal household directly. One particularly promising angle of approach to St. Petersburg, already touched on in passing, though not addressed explicitly (in the Sedlets example above), was based on the long-standing tensions, which had recently flared up (the 1863–1864 Polish Rebellion), between Catholic and Orthodox Christians and the general all-imperial policy of religiolinguistic and cultural Russification thereafter. Thus, when the news of a Catholic wooden temple (kostel)’s conversion into an Orthodox church (consecrated on 13 August 1867) containing “the people’s monument (narodnyiy pamyatnik)”62 in honor of 4 April and 25 May in the large village of Bragin, Minsk governorate (Brahin in present-day Belarus), was brought to Alexander II’s attention in late 1870, he sent as a gift a Christ Savior icon bearing the sign “We rejoice in Your salvation (Raduemsya o spasenii Tvoem).”63 The new “warm (literally)” church was dedicated to one wonder worker, a recently canonized (1861) Russian saint of the eighteenth century (St. Tihon Zadonskiy), and the icon was celebrated via an elaborate Orthodox ritual of solemn entry (vnesenie) on the feast day of another wonder worker (St. Nicholas, 6 December 1870), to whom the old “cold” church next door was dedicated. Allegedly, the ceremony intrigued people from other faiths or denominations in the following manner: local Jews looked on with curiosity whereas some Catholics, even though none lived in the village, entered the new temple, and kissed the icon (lobyizat’, prikladyivat’sya) one by one, in the reverend manner of a multitude of Orthodox pilgrims from far and wide. Following an all-night vigil (vsenoshtnoe bdenie), a procession of the cross with the icon being carried and lowered in the sign of the cross as a benediction to the people, circled three times (troekratnoe obhozhdenie) the old church amidst readings of the four Gospels, then repeated the motion around the new one before entering it. After the completion of the sacred rites there, the icon was laid to rest on the holy throne in the center of the altar until a suitable kiot could be arranged for it. A local choir sang the imperial hymn “God Save the Tsar”, and in the evening, the new church was decorated and illuminated. With the exception of the holy rites themselves, the church bells rang continuously.64

Further west, in the large village of Lyahovichi (in present-day Belarus), Slutskiy county, Minsk governorate, the Christ Savior icon, gifted by the Tsar to the local parishioners, simply bore the year “1867.”65 On 4 April 1869,66 it was embedded into a different set of sacred objects—amidst other large hand icons, eight gonfalons, and a large hand-held cross, before a church analoy67 with the Gospel—in a different space (the village square) and a different sacred choreography—a prayer service in the open performed by an abbot, Father Serapion, a deacon, and a former Catholic priest (ksendz), who had converted to Orthodoxy in 1867, and attended by, among others, hundreds of Jews, many Catholics, some Tartars, and 40 Hussars of the locally stationed Mitava Regiment. During the benediction for longevity and prosperity (mnogoletie), sung in a four-part polyphony, people lined up to kiss the cross. Upon completion of the prayer service, the church choir, which consisted of 14 recently trained illiterate peasant boys, took up “God Save the Tsar,” followed by a hymn containing these lines:

Glory be! Glory be! To Our Russian Tsar!God-given to us: Tsar—MasterMay Your Tsarist Clan be immortal!And through Him may the russian people prosper!68

After a brief ceremonious return to the church and hymn singing with genuflection, the congregation broke off. Upon their departure, the priests were surrounded by peasant children. Those among them who had converted to Orthodoxy in memory of 4 April69, received little crosses as gifts.70 In fact, prior to the service in the square, after the morning service, the abbot “told those present in the church both of the 4 April event itself and of its significance for the prosperity (blagodenstvie) of our state [lit. “mastership (gosudarstvo)”] through the preservation of the precious life of our beloved Monarch from the villainous attempt. At the end of the teaching (pouchenie), the abbot gave instructions, on the basis of the holy Scripture, how to pray for the Tsar, the Tsarist house and all orthodox christians.”71

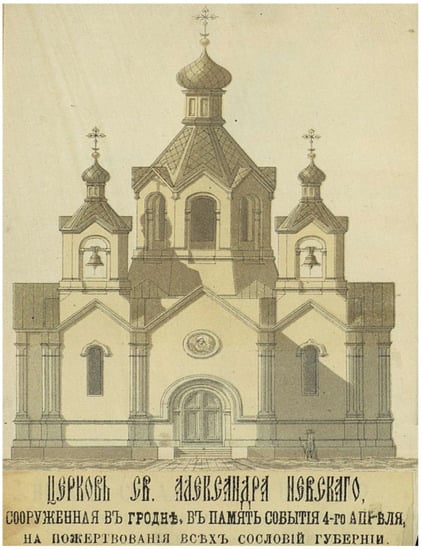

Finally, some places in the provinces that had temples erected and dedicated in memory of the assassination attempts were fortunate enough to be visited by the Emperor himself,72 at a rate impossible to gauge at this time. Such was indeed the case with Grodno (Grodna in present-day Belarus), the seat of the eponymous governorate, west of Minsk. Immediately following the 4 April event, the locals committed to building a church, which they financed and furnished via a large-scale campaign of voluntary donations from people of all classes and creeds (including the Orthodox and Catholic clergies, as well as Jews), even from faraway places, such as Moscow. The list of donors of church plate, priestly attire, icons, gonfalons, etc. started at the very top with the reigning Empress,73 the heir and his wife, followed by members of the high nobility, military officers and soldiers, merchants, and civil servants all the way down to ordinary individuals, including war veterans and peasants. The St. Alexander Nevsky church (Figure 4) was finished in late 1869, consecrated on 4 April 1870, and visited by Alexander II on June 24 that same year. Among the sacred objects donated, an icon of the Lord’s Transfiguration (Preobrazhenie Gospodne) deserves particular attention in terms of (1) its subject, (2) its donor—the Jews from the large village of Lunno, 40 km away—and (3) its dedication to the 25 May pokushenie, a singular occurrence in the entire ceremonial report. One cannot help but wonder whether the choice of a theme had anything to do with the fact that, according to all the Gospels of the New Testament, during the Transfiguration event, Jesus met and talked with two prophets—Moses and Elijah—of the Old Testament (the Jewish Bible). In other words, these people may have sought a middle ground, a common point of agreement where their faith could meet the Tsar’s.

Figure 4.

Source: Pamyatnaya Knizhka Grodnenskoy Gubernii na 1871 god, Chast’ 2 (1871).

The strategies for invoking the ruler’s presence in connection to pokushenie commemorations in faraway parts were not limited to the icons themselves. Sometimes, it was their decorative setting itself that did the job. Such was the case with a Kalmyk74 district school in Novocherkassk (in the far south of present-day Russia), which received a rather standard 4 April icon (St. A. Nevsky and St. Joseph) as a consequence of voluntary donations from parents in 1866. What is noteworthy is that its gilded kiot was embellished with miniature images of the imperial regalia. This example must have spread,75 since we find another community in the same diocese, the Don Cossacks76 in Verhne-Kurmoyarskaya (present-day Russia),77 dedicating in 1868 a large (2X3 arshins78) icon of the same saints to the same occasion and decorating its gilded frame with bas reliefs of the “tsarist attributes: crown, scepter, and so on.” The original intention, that arose during a prayer service of gratitude on 4 April 1868, was for the icon to serve “as a [token of] remembrance to [our] children and grandchildren.”79

The author of these two ceremonial reports, Fyodor K. Trailin, referred to Alexander II as “the Head of the Fatherland (otechestvo),” an unusual term, likely a product of the militarized Cossack mentality with which he was imbued from birth. The next section of this article will analyze further, explicit, and evocative, cases of intertwinement of spatial attachments/identifications, faith, and the Emperor in concentric circles radiating out from the local to the regional and on to the imperial level.

In 1872, the waters of a natural spring near the village of Velikoretskoe80 (present-day Russia) were piped. Above the pool of the water conduit (vodoprovod), between the Transfiguration and the St. Nicholas churches, a chapel dedicated to the Tsar’s survival of the 25 May pokushenie was erected by the peasants of the four villages81 of the local volost’. As it turns out, the date—25 May—coincided with “a great feast in the village of Velikoretskoe to which God had sent a singular mercy by the appearance of the miraculous Image of St. Nicholas the Wonderworker.” Apparently, each year, upon the approach of this date, the miraculous image was ceremonially transferred from Vyatka Cathedral, in the eponymous seat of the governorate, 66 km. away, to Velikoretskoe, where it stayed for three days (23–25 May).82 Pilgrims, up to 35,000 and more, from all corners of the governorate flocked to the village to pay their respects. The report’s author reasoned, as may well have the new chapel’s donors before him, that “these many thousands of worshippers, excited by the visible reminder of the salvation of our beloved Tsar from the villainous attempt, will raise fervent prayers to God for His prosperous reign and lift up gratitude to the Lord for preserving our fatherland from the great danger.” According to the donors’ wishes, the diocese authorities ordered that the icons from the nearby St. Nicholas chapel, built on the site of the saint’s image’s appearance, be ritually transferred to this chapel on 25 May every year. On that day in 1872, both the water conduit and the chapel were sanctified, and a prayer service, attended by numerous crowds, was held. At the peak of the solemn rites, in a gesture of “sacrifice in gratitude to the Tsar of Heaven” for saving the life of the Emperor, people en masse threw copper or silver coins, rings, or even earrings (in the case of a devout, if moneyless, Komi83 woman) into the pool.84

This was not the only case combining local amelioration/entrepreneurship and piety: in 1868, the peasants of another village (Verhoshizhemskoe) from the same county erected a chapel dedicated to 4 April and 25 May at the spot where they planned to set up a three-day Alexander Fair (yarmarka) from 21 May to 25 May each year. Not surprisingly, the foundation stone ritual took place on 25 May. What is more interesting is that the approximate date of completion, in July that year, seems to have been reflected in the inclusion of an icon of a regional85 (and all-imperial) significance (“the Appearance of the Kazan Mother of God”),86 whose feast fell on 8 July, in the chapel’s iconostasis.87 Moreover, it was public knowledge that, immediately after the 4 April shot, Alexander II had visited and prayed to the eponymous icon in the Kazan Mother of God Cathedral, about 1 mile away from the pokushenie site in St. Petersburg. Quite likely, this icon served as yet another imaginative mental link between deep provincials and the Emperor.

Let us revisit the original (general) sacred matrix and spell out its ruler and ruled (specific) implications. For their part, the emperor and the royal family operated on all three axes in a strictly positive manner—from the assassination attempts themselves (first), to donating icons, priestly attire, etc. (second), to paying actual visits and partaking in local rituals (third). The rest of society was beholden to a different triad—‘sin’ (axis 1), ‘guilt’ (axis 2), and ‘sacrifice/offering’ (axis 3), aiming at absolution/exculpation.

In fact, the entire set of newly forged and constantly shifting sacred objects, shrines, and religious rites can be conceived of as one large and ever-growing, complex purification ritual, a symbolic cleanup operation in the aftermath of the assassination attempts, which had been highly disruptive88 of the dominant power flows, polluting sacred space and therefore traumatic to the popular psyche. Crucially, it also had a forward-looking purpose of prevention, which gave activities, especially along Axis 3, a magical aspect.

Indeed, one does get a firm sense of the existence, on various levels (individual and group, local and regional), of often unspoken yet always unquestionable guilt and a striving towards repentance for a great sin vis-à-vis the ruler in the aftermath of each assassination attempt. Even though we cannot explore its specific Orthodox theological and Russian cultural roots in this article, we can at least shed light on some of its more vivid and telling ritual ramifications. If we visualize the closed circuit of devotion to the ruler going in one direction and fatherly love/care for the ruled going in the other, as a common field normally in a sort of loyalty equilibrium, then we could say that each assassination attempt caused a massive disturbance of it. All immediate and recurring ceremonial responses were intended to return the field back to its equilibrium. If we split this disturbance and the consequent pressure for guilt compensation/clearance into general and particular components, then it becomes clear that the former called for a deluge of telegrams of support and declarations of devotion to the Emperor in the form of addresses, both of which indeed sprung up from all parts of the Empire and traveled to the center by way of the local governors. As it turns out, the latter, specific components could, depending on circumstances, translate into loyalty surpluses or shortages, along wider regional lines. Thus, as Kostroma’s stock, already high, could shoot up with Komissarov’s heroic act during the first pokushenie, Volhynia’s stock could sink abruptly in the eyes of the imperial public bringing shame to the inhabitants in their own eyes as well after the second pokushenie committed as it was by a member of the Polish religiolinguistic community of Volhynia. It is to the latter case and the respective searches for spiritual absolution that we turn next.

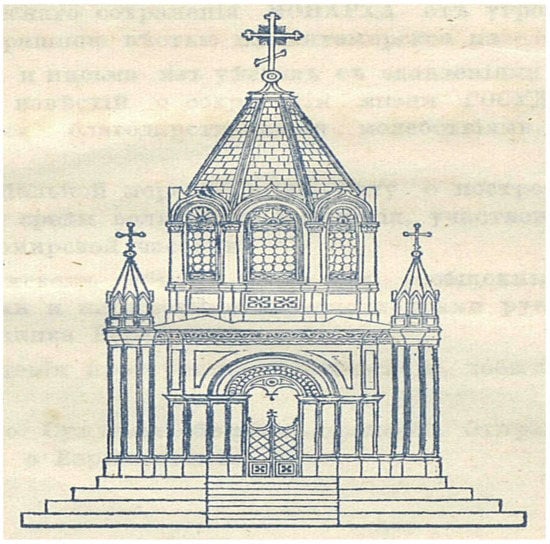

On 27 May 1867, two days after Antoni Berezowski’s attempt on the Tsar’s life, the governor of Volhynia sent a telegram to the Minister of the Interior to request permission to collect voluntary donations towards the construction of a commemorative chapel in the capital, Zhitomir (Zhytomyr in present-day northwest Ukraine).89 Less than a year later, on 11 April 1868, the imperial censorship bureau authorized the printing of a book of 86 pages that included descriptions of immediate reactions—by day and locale within the governorate—to the heinous act, a list of donors, a sketch of the proposed sanctuary (Figure 5), etc.90 Indeed, the chapel’s foundation was laid on 25 May 1868, and the building was erected later that year. This was neither the only nor the most radical work of the pious imagination seeking a collective Volhynian redemption.

Figure 5.

Source: Bratchikov (1868, p. 2).

In 1867, a professor of Holy Scripture, Latin, and Greek in the Volhynian Seminary, a Volhynian native by the name of Andrey Hoynatskiy (1837–1888), composed an icon, entitled “A Council of Volhynian saints pleasers (ugodniki) of God in memory of the miraculous salvation … of 25 May 1867,” for which he received a gift from the Empress Maria Alexandrovna—a golden ring decorated with gems.91 The list included eighteen saints,92 a fact which, years later, evoked the following reaction from a sympathetic anonymous commentator: “We should not treat but with special compassion the laudable zeal of Father Hoynatskiy towards the glorification of his fatherland Volhynia’s saints even though to their number he adds some who have been in Volhynia by chance such as, for example, St. Cyril and St. Methodius, teachers of the Slavs … and even some who have hardly ever been to Volhynia …”93

A few years later, in 1874, the Pochaev Monastery, which had been converted from the Uniate94 faith to Orthodoxy95 by Emperor Nicholas I immediately after his suppression of the Polish Revolt of 1830–1831, had “the images of Volhynia saints and other saints who had been prominent in the history of the Volhynian soil” painted on all walls of its Holy Dormition Cathedral.96 This act, in turn, inspired in 1878 Andrey Hoynatskiy, at that time a priest and teacher of divine law at the Nezhin Lyceum, to design a prospective liturgical service in the name of all Volhynian saints to be performed in the church of the Zhitomir high school, which he thought should be built in honor of them. Naturally, Hoynatskiy suggested their feast day be 25 May, “in the example of the Pochaev Monastery.” To this end, in 1878, he published a book, entitled “Accounts (ocherki) from the History of the Orthodox Church and Ancient Piety in Volhynia presented in the Biographies of Volhynian Saints Pleasers of God and Other Saints who took a most active part in the historical destiny of the Volhynian land.”97 Hoynatskiy envisioned the creation of brotherhoods in every county town of the governorate, each named after the local saint, for the purpose of disseminating information on the Volhynian saints and organizing commemorations of them. To his mind, it would behoove these brotherhoods “to have icons of all of these saints without any objections or reservations.” The next step would be to open subordinate branches in the rural parishes so that an entire network (set’) of brotherhoods would cover all of Volhynia. They would all strive to keep alive the memory of these saints by, among other things, dedicating icons, chapels, churches, church annexes with altars (pridel), etc. to them.

It matters little whether Hoynatskiy’s zealous musings came to be realized in their totality or not. The point was to examine the structure of the imaginative pathways in the aftermath of the assassination attempts and the logic of their unfolding in the lives, both ceremonious and mundane, of people from all walks of life. What began as a mere statement of the birthplace of a would-be assassin, resulted in a chain reaction of various individuals and institutions prodding each other into an open competition in pious patriotism, with substantial multi-level ripple effects.

The final section of this article will focus on other expansions of the new sacred matrix, or, more precisely, what can be termed “latitudinal/lateral (intra-ruler)” and “longitudinal (inter-ruler)” commemorative linkages of the assassination attempts across the Russian Empire. It will do so both in aggregate and by way of individual examples.

6. Commemorative Linkage and Expansion

Soon after the fifth attempt on the life of Alexander II (5 February 1880), the Holy Synod prescribed that 4 April, one of the five days of “miraculous salvation” of the monarch be commemorated with “a special solemnity.” However, the leaders of some dioceses found it necessary to issue circulars prescribing the celebration of the other days, “marked by the Lord’s Providence,” as well.98 One of them was Isidore, Metropolitan of Novgorod, who on 13 March 1880, by circular No. 192, directed the clergy of the Diocese of St. Petersburg to conduct a prayer service of gratitude to God “on the occasion of the deliverance of His Imperial Majesty from the looming danger” in all town, monastery, and village churches on 2 April and 4 April after the daily liturgy. In the future, the same directive was intended to hold for all five days every year (ezhegodno).99 Nor was this fusion of religious fervor and devotion to the monarch restricted to mainstream Orthodox believers alone. In the village of Lazh, Vyatka governorate, a young priest by the name of Vissarion Ergin equated the arrangement of icons commemorating 4 April to “a patriotic act”100, which he recommended not only to his Orthodox parishioners but also to the neighboring Old Believers.101

Finally, here are two cases of ritual accretion (and building expansion) that transcended both the attempts on Alexander II’s life and his reign all the while gaining a greater significance, both literally and mystically. From 1857 to 1859, a Cossack sergeant by the name of Sergey Polyakov built a well in a steppe ravine near Mariinskaya stanitsa on the Don in memory of his fallen brothers-in-arms who had suffered thirst during the Siege of Sevastopol (1854) in the Crimean War of 1853–1856. It was then consecrated to St. Nicholas, the Wonderworker, and his icon hung on the well’s wooden log roof. In 1867, a friend of Polyakov’s—a cornet (Ivan Stefanov) along with a merchant (Stefan Abrosimov) erected a chapel above the well, dedicated to St. Nicholas, in memory of the 25 May event. They sent a telegram to the Emperor, received his grateful approval, and arranged for an annual procession of the cross from Mariinskaya to the chapel on 9 May,102 which drew thousands of pilgrims, including Old Believers and Kalmyks.103 Next, Stefanov wished to build a monastery for monks in memory of 25 May, but, for some reason could not obtain permission from the diocese authorities. That changed twenty years later, in 1888 when Emperor Alexander III survived a train wreck near Borki. After Stefanov had donated further capital, the chapel was converted a year later into a church (St. Nicholas), in which services were held following monastery precepts, and a so-called “bishop’s courtyard (arhiereyskoe podvorye),” with a resident monk, was founded. In 1893, in view of the growing number of pilgrims who could no longer be accommodated, two church annexes were added, one of which was dedicated to Emperor Alexander III’s namesake saint (St. Alexander Nevsky).104 Finally, on 25 July 1895, by Order No. 2348 of the Holy Synod, the Bekrenevsky Monastery was founded.

The last few observations tie back to the Chernigov example discussed above as a sort of capstone. On 26 June 1911, 45 years after the first attempt on the life of Alexander II and 30 years after his death, the foundation stone for a St. Alexander Nevsky church and a Nikolaevskiy Diocese House next to the St. Alexander Nevsky chapel in memory of the 25 May event was solemnly laid in Chernigov, and once more, the gist of proceedings was memorialized in writing on a copper plaque.105 When apprised of this, Emperor Nicholas II responded, also in writing, with the following words: “I read it [the report] with pleasure.”106 The tsar must have been so impressed that he included the site in his upcoming travel plans and did indeed visit it on 5 September 1911.107 That encounter unfolded with a ritual complexity worthy of another article.

In the end, from one angle, it would seem that all intricate mythomystical play on the minds of the devout, all consummate ritual gamesmanship came to naught. On the sixth attempt, Emperor Alexander II became victim of his own curiosity or gallantry—rather than immediately leaving the site of the grenade attack against his carriage on the Ekaterininskiy canal in St. Petersburg on 1 March 1881, he hung around to inquire or say a soothing word to the wounded soldiers and died from another grenade explosion by a hitherto unseen attacker, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, a Belorussia-born revolutionary of Polish noble descent. Emperor Nicholas II also died a violent and even more ignominious death at the hands of the Bolsheviks, by firing squad and possibly bayonet, along with his wife, four daughters, and a son in Ekaterinburg on 17 July 1918. They were all buried at a secret location precisely in order to deprive followers of a physical/spatial basis for the construction of their personality cults. In the long run, it still did not work: in 2000, they were all canonized as saints of the Russian Orthodox Church as were the family doctor and several personal servants who died with them. At the site of Alexander II’s assassination, literally over a bloodied segment of the street’s pavement and canal fencing, a magnificent church—“the Savior on the Blood”—was constructed from 1883 to 1907. In the same vein, a “Church on the Blood” was built at the last Romanovs’ execution site in 2003.

Having begun to grasp the complex, multi-directional expansion of the new sacred matrix of symbolic, increasingly abstract yet fully lived, at times all-encompassing, overwhelming ruler-ruled interaction, the reader can perhaps begin to comprehend the great viciousness and ruthlessness with which the Bolsheviks demolished thousands of chapels, churches, and monasteries throughout the vast realms of the next Empire, the Soviet Union, before re-employing all previously developed techniques in the service of their own newly launched regime and personality cults.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The sixth attempt, on 1 March 1881, finally took the Emperor’s life. |

| 2 | These are approximate numbers I have compiled based on various lists, which are publicly available. Although they may not be precise and/or exhaustive, they point to clear trends which would be hard to refute. |

| 3 | See Stephanov (2014), and especially, Stephanov (2019). Although I have dwelled on modern ruler visibility in the Ottoman and Russian imperial cases only, there is no doubt in my mind that this term can have highly profitable applications globally. Michael Burleigh calls it “public visibility.” See Burleigh (2021, pp. 9, 56). |

| 4 | Since the sixth attempt, on 1 March 1881 does bring the Emperor’s life to an end, its ritual ramifications cannot be distinguished from those of the death itself. Therefore, it will not be dealt with in this article. |

| 5 | On 29 April 1891, a Japanese policeman—Tsuda Sanzo—escorting Grand Duke Nicholas Alexandrovich during his visit to Otsu, Japan as part of his world tour attempted to murder him by swinging at his face with a sabre. The wound was not lethal. The assassin’s motivation remains unclear, with explanations ranging from hatred of foreigners to mental derangement. |

| 6 | On 17 October 1888, the train with the royal family travelling from the Crimea to St. Petersburg derailed near the village of Borki, 50 km. away from Kharkov (Kharkiv in present-day Ukraine). Although there were many casualties (21 dead and 68 wounded), the royal family survived. It is said that Alexander III, who was known for his exceptional physical strength, prevented the collapse of the royal train car’s roof by holding it up with his bare hands until help arrived. |

| 7 | See (Zaharova 2001, 2003; Ageeva 2008; Ibneeva 2008; Otto 2009; Klyukova 2010; Limanova 2017, 2018). |

| 8 | The existing studies focus on geographically restricted, local or regional festivities (Goncharov 2004, 2013; Shilin and Skubnevskiy 2008; Аkireykin 2012; Gavrilova 2015; Frolova 2016; Ayusheeva 2018; Tsyganova 2019). |

| 9 | See (Kuzyichenko 2007; Buslaev 2010; Korkina 2013; Zipunnikova 2016; Sosnitskiy 2019; Saginadze 2020; Zav’yalova 2021; Komzolova 2022). |

| 10 | See also (Chesnokov 2014; Lobacheva and Karabut 2011). |

| 11 | See (Geyfman 1997; Budnitskiy 2000; Kinzhibaev 2008; Zimin 2012; Vorob’ev 2016; Zaharov and Shaymardanov 2018; Lukin 2019; Fathiev and Doronin 2021). |

| 12 | See (Ely 2016, 2022). |

| 13 | For scholarship on local reactions to the events themselves, see (Romanova 2006; Shevzov 2010; Korotun 2019). |

| 14 | This section borrows definitional passages from Stephanov (2022). See also Stephanov (2019). |

| 15 | The royal name day is the feast day of the royal namesake saint. |

| 16 | Upon his untimely death in late 1825 in Taganrog, South Russia, Emperor Alexander I had left neither a natural progeny, nor a publicly designated successor. This delicate situation created a split in elite loyalties between Alexander’s younger brothers Constantine and Nicholas, who were in Warsaw and St. Petersburg, respectively. To make matters worse, Constantine was allegedly sympathetic to the promulgation of a constitution for the empire, whereas Nicholas was very clearly not. By the time it became widely known that Constantine had definitely given up the throne, a constitutionally minded portion of the aristocracy and a few elite military units had committed open rebellion in the capital, which was bloodily put down by the eventual successor, Nicholas I. |

| 17 | For a similar approach, see Brophy (2009). For a different conceptualization, based on a different notion of socialization and social control, see (Cengiz Kırlı 2010). For the most influential formulation of a concept of public sphere, see Habermas (1989). |

| 18 | See Stephanov (2020, pp. 64–65). |

| 19 | See Chapter 9 (“Parents and Son”) in Wortman (2006). |

| 20 | See Stephanov (2020). |

| 21 | Wortman (2006, p. 171). |

| 22 | Zhukovskiy (1902, vol. 2, p. 126). The underlining is mine. |

| 23 | Cf. the cases of Emperor Alexander I (Stephanov 2020) and the Ottoman Sultan Abdülmecid (Stephanov 2019) on the one hand, and their respective subjects, on the other. |

| 24 | Wortman (1995, vol. I, p. 269). |

| 25 | See (Stephanov 2019, p. 151 and Stephanov 2020, p. 72). This concept, which I have not hitherto defined, refers to the widespread practice in contemporary empires of bestowing the august royal name, as well as depending on the particular cultural setting, the names of other royal family and dynasty members, both living and deceased, upon a wide range of public institutions, buildings, settlements, etc. as well as private company products. Needless to say, the presumption was that the named/grantees would thereby take on a veneer of mystique, which would be beneficial both in terms of popular loyalty and in terms of doing business. |

| 26 | Severnaya Pchela, 5 August 1832. |

| 27 | Alexander Nevsky (1221–1263), a key figure of medieval Rus,’ is a warrior saint of the Russian Orthodox church (canonized in 1547). |

| 28 | Severnaya Pchela, 2 October 1830. |

| 29 | Wortman (2006, p. 177). |

| 30 | Nikolaev (2005, p. 15). |

| 31 | By comparison, Nicholas’s trip in 1816 shortly before his twentieth birthday had lasted only three months (Wortman 2006, p. 125). |

| 32 | Wortman (2006, p. 178). |

| 33 | This appraisal excludes significant segments of the intelligentsia, portions of the nobility, and some religio-linguistic communities with a strong national orientation, such as the Poles. |

| 34 | Serfs were peasants bound to the land. |

| 35 | The same moniker became famous in Bulgaria, a principality carved out of the Ottoman Empire as a result of the Russo-Ottoman War of 1877–1878. Once more, the date of the San Stefano Treaty, which concluded that war, and the Day of Independence in Bulgaria to this day, is notable—19 February (OS)/3 March (NS). |

| 36 | Cross-dating refers to the act of combining one ceremonial occasion (such as, for example, the inauguration of a building) with another (such as, for example, the royal accession anniversary) on the same day for an accumulated effect on the public mind. This was a major strategy for ruler aggrandizement in many late empires. |

| 37 | Unless explicitly noted otherwise, all dates are in the Julian calendar. |

| 38 | Sankt Peterburgskie Vedomosti, 13 April 1866. |

| 39 | Volost’ was the smallest administrative unit in the Russian Empire, a set of several villages and their lands. |

| 40 | A procession of the cross (крестный хoд) is a religious procession with crosses, gonfalons, and icons. |

| 41 | Saratovskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, Year II, No. 22, 7 June 1866. |

| 42 | An early form of a system of self-government in rural areas. |

| 43 | Chernigovskiya Eparhial’nyiya Izvestiya, No. 13, 1 July 1867. |

| 44 | The description of the icon is succinct: “with an omophorion (a bishop’s vestment) on the hands.” |

| 45 | Needless to say, St. Nicholas was Alexander II’s father’s patron saint. |

| 46 | The attentive reader will note that both Christ Savior and the Mother of God images were present in the ur-chapel in St. Petersburg, the paragon for all other pokushenie-themed sanctuaries across the land. |

| 47 | Wortman (2006, p. 385). |

| 48 | One wonders whether it was a coincidence that the list of gifted icons, St. Nicholas included, was recorded on 4 December 1866, i.e., only 2 days before the feast of St. Nicholas. |

| 49 | Pamyatnaya Knizhka Sedletskoy Gubernii na 1876 g., p. 231. |

| 50 | The first set is of the three holy hierarchs—St. Basil the Great, St. Gregory the Theologian, and St. John Chrysostom; the second—St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, St. John the Merciful (Patriarch of Alexandria), and St. Basil the Confessor (Bishop of Parium). |

| 51 | Hersonskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, No. 14, 15 July 1867. |

| 52 | The Holy Synod was the highest administrative and judicial institution of the Russian Orthodox Church. |

| 53 | Hersonskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, No. 11, 1 June 1868. |

| 54 | Tambovskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, No. 23, 1 December 1880. |

| 55 | The consecration ceremony drew more than 3000 people, even though the church could only hold 1000. |

| 56 | Poltavskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, No. 22, 15 November 1874. |

| 57 | There does not seem to be a limit to this natural progression. Towards the end of Alexander II’s reign, a speech by Panteleimon Sapozhnikov, a monk in Moscow’s Bogoyavlensky Monastery, on the feast day of his namesake saint marked the date also as the birthday of the Empress, the birthday and name day of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevitsch the Elder, and the name day of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevitsch the Younger. It was published in Moscow in 1879. |

| 58 | A specifically Russian brand of revolutionary populism in the sense of idealization of the peasant commune and belief in its leading role (as opposed to the working class) in social reform. |

| 59 | The Russian root “master (gosudar’)” lies also at the heart of the Russian word for state—gosudarstvo, i.e., literally “a mastership”, “a belonging of the master”. |

| 60 | Addendum to Tul’skiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, No. 4, 15 February 1880. |

| 61 | Yaroslavskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, Year XXI, No. 52, 24 December 1880. The church still stands. |

| 62 | This brief mention of an act of architectural integration of belief and belonging is very intriguing. Unfortunately, the report provides no further information whatsoever about this monument. |

| 63 | This is an excerpt from Psalms 19:6. The full original reads: “We will rejoice in your Salvation (Myi vozraduemsya o spasenii tvoem) and in the name of our Lord will raise a banner (znamya). May God fulfill all your requests.” Translation is mine. Minskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, No. 4, 28 January 1871. |

| 64 | Minskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, No. 3, 21 January 1871. |

| 65 | It is not clear what this date meant—a connection to the 25 May event or a production/dedication year of the icon. If it is the former, due to the Polish element being prominent in both that event and the Western borderlands of the Russian Empire, then why was 4 April chosen for the sacred rites in Lyahovichi. If it is the latter, then why the two-year delay in its delivery and ritual reception? |

| 66 | Minskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, No. 9, 15 May 1869. The entire account comes from this source. |

| 67 | A high sloping table, on which liturgical books, icons, and other church accessories are placed. |

| 68 | Punctuation and capitalization are in accordance with the original. |

| 69 | Interestingly, despite the rich religious background of proceedings that day, the whole account was entitled simply—“the 4 April festivity (prazdnik) in Lyahovichi”—and not a single saint was mentioned explicitly, not even the one to whom the church was dedicated. Was this a coincidence, an omission due to the author-witness’s ignorance or, perhaps more likely, a deliberate policy of mental/spiritual centralization, an attempt to moor these souls, newly joined to Orthodoxy, directly to the ruler in St. Petersburg? See ft. 65. |

| 70 | As the reporter felt obliged to point out, the entire Lyahovichi parish consisted of recent converts (lit. “adjoined/attached ones”). |

| 71 | Once more, capitalization is significant and therefore kept in the original form, despite common English-language conventions. |

| 72 | Although the actual occasion for this royal visit remains to be determined, it might have something to do with the fact that this church lay on the land route from St. Petersburg to Western Europe. |

| 73 | Maria Alexandrovna gave away, among other things, several items of priestly attire bearing the monogram of her late mother-in-law, the Dowager Empress, Alexandra Fyodorovna, thereby establishing, whether deliberately or not, a symbolic multi-generational connection of royals, both living and dead, to the new Orthodox temple in the borderlands. |

| 74 | Kalmyks are a Mongol people of the Oyrat group of tribes who migrated from Central Asia to the Lower Volga and the Caspian region in the XVI—XVII centuries. |

| 75 | The author of the ceremonial report connecting the two locales, Fyodor K. Trailin (1836–1919), the first librarian of the Novocherkassk Town Library, who worked in the former at the time and hailed from the latter, may have had something to do with this. |

| 76 | The Cossacks are a group of predominantly East Slavic Orthodox Christian people who were members of self-governing, semi-military communities originating in the steppes of Eastern Europe. |

| 77 | This large Cossack settlement (stanitsa) was submerged in 1950 as part of the Tsimlyanskiy Reservoir on the Don. |

| 78 | Arshin is an ancient Russian unit of measure. One arshin equals 0.7112 m. |

| 79 | Donskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, Year I, No. 12, 23 March 1869. |

| 80 | Navalihinskoe volost’, Orlov county, Vyatka governorate. |

| 81 | Velikoretskoe, Navalihinskoe, Solovetskoe, and Chudinovskoe. |

| 82 | The image of St. Nicholas first appeared on the shore of the river Velikaya in 1383. Beginning in 1668, by order of the Vyatka Bishop, it was feted on 24 May. The land route was designed in 1778. After a long interruption during the Soviet period, this procession of the cross is still enacted annually and is one of the largest in Russia today. |

| 83 | A Finno-Ugric people today inhabiting mostly the Komi Republic of Russia. |

| 84 | Vyatskiya Eparhial’nyiya Vedomosti, No. 13, 1 July 1872. |

| 85 | Kazan is on the same meridian, only about 295 km away, i.e., almost next-door by the standards of Russian mental geography. |