Abstract

This paper presents an analysis of a ritual event memorialised on stone reliefs at the ancient city of Carchemish around 800 BC. It is argued that the reliefs represent a ceremony of investiture, in which boys of royal lineage are handed out toys as oracular instruments to elicit favourable omens for the heir apparent. The inclusion of boys and their toys in the visual commemoration of a political ritual has bearings on three levels of meaning. First, it testifies to a hitherto unrecognised cult practice, involving grouping boys in age classes and harnessing their ludic practices for ritual purposes. Second, it reflects local political preoccupations connected with dynastic controversies, in an attempt to silence counternarratives through the emphatic staging of children. Finally, the chosen imagery conveys complex philosophical ideas about life, education, and individual destiny, connecting with issues of material religion and childhood studies. The study integrates interpretive perspectives from visual semiotics, architectural analysis, and ancient studies to show how, upon specific occasions, marginal groups and everyday material items, such as children and their toys, may play critical roles in collective ritual events.

αἰὼν παῖς ἐστι παίζων πεσσεύων • παιδὸς ἡ βασιληίηLife is a boy playing, moving checkers on a board: royal power in the hands of a boyHeraclitus, fr. 52 D.-K.

1. Introduction

The research introduced in this paper explores the incorporation of children and their toys in political rituals, using as a state ceremony memorialised on stone reliefs at the ancient city of Carchemish, on the western shores of the Syrian Euphrates (Figure 1), as a case study. Following Catherine Bell, I understand political rituals as “ceremonial practices that specifically construct, display and promote the power of political institutions” (Bell 1997, p. 128). In its effort to be as effective as possible, this kind of political legitimation is often pursued through complex dramaturgical strategies, with ritual actors manipulating symbolic objects in spectacular, affective settings. This analysis shows that at Carchemish, the decorative cycle known as the “Royal Buttress” (Figure 2), erected in the city centre at the beginning of the 8th century BCE, depicts a royal investiture ceremony meeting Bell’s definition of a political ritual.1 Breaking with contemporary conventions, the images foreground the presence of boys playing with knucklebones and whipping tops. This unique choice relates to critical issues at the crossroads of material religion and childhood studies, opening perspectives on the symbolic meanings and extraordinary powers sometimes ascribed to children and children’s toys.

Figure 1.

Location of sites mentioned in text (map by the author, geographical background from Natural Earth).

Figure 2.

Rollout of the Royal Buttress reliefs (drawing by Elia Bettini).

In the ancient Near East, games and competitions were sometimes embedded in civic and religious festivals, providing popular occasions for entertainment and skill display.2 The specific cultic connotations of these ludic activities are still poorly understood. Literary sources suggest that they mixed fun aspects with serious expectations and anxieties. In the long-lived Sumerian tale Gilgamesh and the Netherworld, the young hero sends his best friend to the underworld to retrieve his lost gaming tools, Akkadian pukku and mekkû, a ball and a mallet used by young men to play a rough team sport.3 As the tale unfolds into a tragic exploration of death, the pukku and mekkû are revealed as dangerous items of transformative power. An analogous embedment of gaming in myth and ritual is not unusual across times and cultures, drawing its evocative power from the inherent ambiguity of play (Sutton-Smith 1997) and the liminal status of children and teenagers (Iijima 1987). Recent analyses combining symbolic anthropology with a “new materialism” single out the specific efficacy of toys in rituals. Toys are tangible, visionary and emotional at the same time. As such, they are items of “materialized affect,” capable of eliciting a semiotic vertigo of multiple meanings (Newell 2018). The reliefs from Carchemish are one of the very few sources in the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean Levant that allow an image-based study of this phenomenon.

In the following, I argue that, at Carchemish, boys of royal lineage were handed out toys as oracular instruments in the framework of an investiture ceremony. The iconographic details of the “Royal Buttress” indicate that this ritual took place under the aegis of two paramount city gods, the Storm God Tarhunza and the goddess Kubaba, the divine “Queen of Carchemish” (Hawkins 1981; Marchetti and Peker 2018). The inclusion of boys and their toys in the visual commemoration of this ritual occasion has bearings on three levels of cultural meanings. First, it testifies to a hitherto unrecognised cult practice, involving grouping boys in age classes and harnessing their games for divination purposes. At a second level, the “Royal Buttress” reveals specific political preoccupations connected with dynastic controversies and the ambiguous status of its main sponsor, the regent Yariri. Finally, at a third, more abstract level, the chosen imagery conveys complex philosophical ideas about life, education, and individual destiny, echoed by the famous Heraclitus’ fragment quoted at the opening of this paper.

2. Historical Background

The term “Royal Buttress” is a makeshift label introduced by early excavators to label a decorated stage platform erected in the ceremonial plaza of Carchemish (Figure 3), just outside the gate to a building compound recently identified as a royal palace (Marchetti 2016).4 The structure, presumably designed for public appearances of the king, was commissioned around 800, when Carchemish was the flourishing capital of a small but enormously wealthy princedom. The city was governed by a monarchy with a remarkably prestigious historical heritage, tracing its origins back to a side lineage of the Hittite Empire, the regional superpower of the 14th and 13th centuries. After the disintegration of the Hittite Empire, the rulers of Carchemish rose to complete independence and started to celebrate their political achievements with large-scale public monuments. These monuments were mainly erected in the city’s central ceremonial square, near the gates providing access to the main temples, administrative buildings, and royal residences. Over time, the square became the city’s main ceremonial arena (later, this space was transformed into the Hellenistic forum). Its monumental decoration was a veritable palimpsest of statues, reliefs, and inscriptions in Hieroglyphic Luwian, the local script. The monuments commemorated royal ancestors, military victories, and significant religious events. Significantly, they also bear traces of numerous remodelling and resignification events, pointing to ongoing negotiations about the monument’s meanings. With reference to the imagery on the Royal Buttress, it is important to note that none of the numerous monuments lining the plaza related in any way to topics of everyday life. Instead, from the 10th century onwards in particular, they consistently reflected state-sponsored ritual performances played out in public, presumably on the very spot (Gilibert 2011). We must keep this in mind in order to fully understand the role that images of children at play might have played within the monumental apparatus of the plaza.

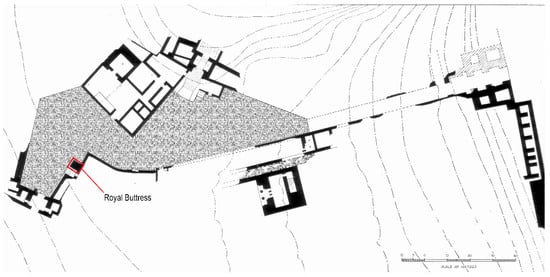

Figure 3.

The location of the Royal Buttress in the architectural context of Carchemish’ ceremonial plaza.

The Royal Buttress was one of the last figurative additions to Carchemish’s ceremonial plaza before the city was declared an Assyrian province in 717. The cycle of reliefs was commissioned by an interim regent, Yariri, who came to power after the premature death of the legitimate king, Astiruwa. In his inscriptions, Yariri takes pain to paint a pacified picture of himself as a just, wise, and loyal servant who paved the way for Astiruwa’s rightful heir. However, the Royal Buttress is a pointed testimony to his self-assertive and likely controversial rule.5 Before rising to his final position of power, Yariri had been a high official acting as “prime minister” and chief of special royal attendants, the wasinasi, for which an interpretation as court eunuchs is now generally accepted (Hawkins 2002; Hawkins and Weeden 2016). His steep trajectory as an outstanding magnate with royal allures and, as his inscriptions reveal, a special pride in erudition, was not unique. Similar figures featured prominently as influential courtiers, often eunuchs and de facto regents, as attested at the nearby sites of Kar Shalmaneser, Arslan Tash, Zincirli, and Karatepe. This generation of “learned viziers” did not attempt to subvert the monarchical status quo but expressed their aspirations, among other strategies, by crafting innovative images of power. They chose to do so because, by that time, the figurative sophistication of stone reliefs had already advanced these works of art to a medium capable of expressing synthetically controversial issues of ethnicity, class, and politics (Brown 2008). The Royal Buttress, subtly weaving together the royal family and Yariri’s royal attendants, is perhaps the most intriguing of these figurative productions.

3. Decoding the Royal Buttress

The ensemble, now on exhibit at the Gaziantep Archaeological Museum, consists of eight slabs carved in a refined high-relief. Originally, the slabs were arranged over a corner, inserted within a previously existing relief cycle converging on the gate to the palace (Figure 4). The previous, less sophisticated cycle, known as “Processional Way”, included ten armed warriors marching in triumph, a line of sixteen veiled women, ten athletic young men bearing offerings, and the goddess Kubaba, represented enthroned upon her totemic animal, a crouching lion (Gilibert 2011, pp. 45–49).

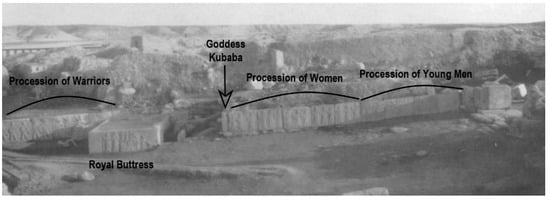

Figure 4.

The Royal Buttress and the adjoining older relief cycles (photo reproduced from Ussishkin 1967, pl. XVa).

Since the Royal Buttress deployed around a corner, it was de facto divided in a primary section facing northwest, aligned with the frontage of the plaza and bearing the images of nine children of varying age and identity, and a secondary section, decorated with a line of seven attendants bearing royal insignia. While the collective of grown-ups—attendants, warriors, women, and young men—manipulate arms or ritual objects imbued with religious meaning, the children are represented at play, in a scene with very few parallels on Western Asiatic monuments.6

The two sections converged on a long cornerstone inscription in Hieroglyphic Luwian (KARKAMIŠ A6; Hawkins 2000, pp. 123–25). The inscription is a first-person account by Yariri, extolling his achievements and providing selected information on the reliefs and their setting. Short captions interspersed among the individual images identify the most important figures (KARKAMIŠ A7; Hawkins 2000, p. 129). So far, studies of the Royal Buttress have dealt primarily with this epigraphic record (Morpurgo Davis 1986; Posani 2017; Yakubovich 2019), devoting little attention to the reliefs. Conversely, early art historical appraisals focused on style, aiming at assessing issues of dating (Akurgal 1949; Orthmann 1971). Decades later, Elif Denel (2007), Marina Pucci (2008), and Alessandra Gilibert (2011) analysed the architectural context in detail and discussed the visual ensemble as a political statement, connecting its imagery on a general level to the rituals and ceremonies held in the plaza. These studies advance our understanding of the Royal Buttress, but their scope does not include a close reading of the figurative composition. They do not discuss the nature of the peculiar objects and distinct attires displayed, nor do they explain the remarkable visual weight conferred to images of children playing in the highly formal context of the city’s central plaza. In the following, I will try to fill this gap and focus on these aspects.

4. Gestures of Power

At a literal level, the Royal Buttress depicts a state ceremony in which the regent Yariri regulated the dynastic succession of Carchemish, entrusted the heir apparent with insignia of royal power, and presented the royal family and the city’s top-level officials. However, both the single details of the images and the composition as a whole are imbued with allusions, symbolism, and allegory, transported first and foremost by specific gestures and, perhaps even more so, by symbolic objects, in a fascinating admixture of material features, emotional pathos, cultic significance, and political theology.

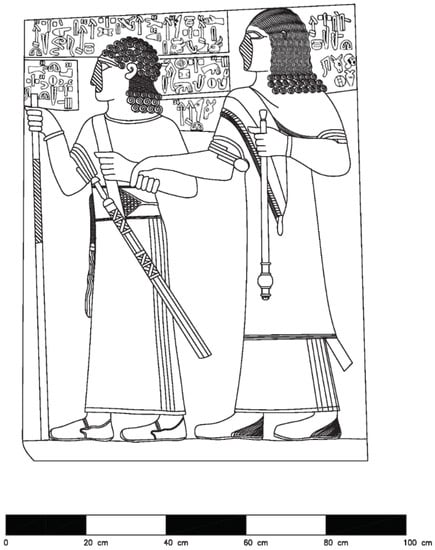

The visual fulcrum of the entire composition is the slab B7a7 adjacent to the corner inscription, here reproduced in Figure 5. The relief portrays Kamani, the young heir apparent to the throne, firmly led forward by the acting regent. Both characters stand in formal attire. Virtually every worn item is laden with symbolism. Most importantly, Kamani holds a staff in his right hand and has a long, elaborate tassel hanging from his belt, both exclusive royal prerogatives.

Figure 5.

Royal Buttress, Slab B7a: Kamani, the young heir apparent to the throne, firmly led forward by Yariri, the acting regent (drawing by Elia Bettini).

Conversely, Yariri holds a mace8 upside-down9 in his left hand and has an ornate toga draped over his shoulders. These regalia were formal attributes of specific status and rank. The same is likely true for seemingly minor details as well, such as the heavy bangles at the wrists and around the biceps of both characters.10

A passage of the corner inscription indicates that the scene commemorates Kamani’s appointment as the crown prince or, more likely, his formal ascension to the throne:

“I [Yariri] built this seat for Kamani, my lord’s child […]. I seated him on high and he trampled down all (enemies)11 while he was a child.”(KARKAMIŠ A6, §8–12)

Several details of this text recall earlier Hittite enthronement rituals, including the figure of a kingmaker identifying the successor, the combined appointment of the designated individual to kingship and priesthood, and his actual formal sitting upon a throne for the first time (Mouton and Gilan 2014). These and other Hittite traits reviewed below infuse the scene with a sense of nostalgia for a lost Hittite grandeur, which is thereby revived and self-consciously transformed in innovative forms.

The text passage clearly states that the enthronement ceremony occurred when Kamani was “a child.” Visually, the heir’s young age (that of a teenager) is expressed by the difference in height and hairstyle between him and Yariri.12 From a political point of view, the scene is first and foremost a statement on the kingmaker’s claims to power. Memorialising his loyalty to the young prince, Yariri put himself centre stage. Yariri’s figure is both towering behind the crown prince and reduplicated in miniature form in front of Kamani’s eyes, at the beginning of the corner inscription, where a tiny but meticulously chiselled Yariri impersonates the Hieroglyphic sign EGO, expressing the Luwian word amu, “I am”.13

Directly above the image, a short caption reads:

“This is Kamani and here I [Yariri] took him (by) the hand and established him over the temple”(KARKAMIŠ A7, §3–4).14

The figure of speech of “taking the hand” of a protégé is a Pathosformel of the Hittite visual and literary heritage (De Martino and Imparati 1998), introduced as a signature image by the 13th century Hittite kings (Klengel 2002; Taracha 2008) and later readapted by the rulers of the post-Hittite Syro-Anatolian polities (Figure 6).15 The so-called Umarmugszene, or “scene of embrace,” expresses in figurative terms the political legitimacy of the person “taken by the hand,” who is always the king or the crown prince. However, in all known cases except Yariri’s, the leading character is a god, usually the Storm God or, especially in the epigraphic record of Carchemish, the goddess Kubaba, acting as divine patron of kingship. In commissioning the sole known exception to the rule, Yariri devised a learned visual twist to illustrate through a resolute, almost muscular gesture of power the extent of his agency, effectively comparing himself to a tutelary god.16

Figure 6.

Drawing of the ARSUZ 1 stela (from Dinçol et al. 2015, Fig. 06).

5. The Eunuchs’ Line and the Weapons of the Storm God

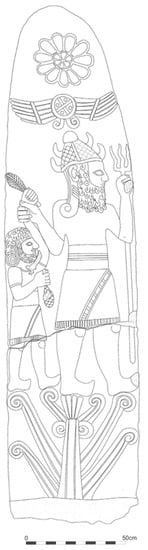

Ilya Yakubovich (2019) has proposed that Kamani’s ascension to the throne foresaw his investiture with the divine weapons of the Storm God Tarhunta, based on the following rendering of a passage on the socle of a lost statue of Yariri:

“I exalted Kamani as successor when I armed him for pre-eminence over kings”(KARKAMIŠ A15b, §§13–14)

Yakubovich’s interpretation fits with the imagery of the Royal Buttress’ secondary section (Figure 7). Here, seven wasinasi-attendants walk toward Kamani holding several weapons, including a double axe (later erased) and a staff ending as a tree branch. While some weapons may refer to the eunuchs’ varying ranks, the axe and the “tree branch” are divine weapons traditionally ascribed to the Storm God in text and imagery, which included a war axe and a “tree of lightning”, symbolising the power of thunderbolt (Wyatt 1998; Smith 1994, pp. 338–40).17

Figure 7.

Royal Buttress, slabs B4–5: the “eunuchs’ line” (drawing by Elia Bettini).

In the ancient Near East, deities had supernatural weapons. Some of these divine weapons were kept as actual ritual paraphernalia in temples. They were objects of prestige and devotion, cast in gold and other precious materials, carried forth as standards in processions and on the battlefield, and bestowed as power insignia upon rulers in ceremonies of investiture in temples (Wyatt 1998; Schwemer 2001, pp. 215–16, 226–27; Annus 2002, pp. 51–108). If this line of argument is correct, the left side of the Royal Buttress precisely commemorates this salient moment of Kamani’s ascension to the throne.

From a compositional point of view, the line of eunuchs plays with the relative heights of the depicted characters and their changing stand line to convey an impression of choreographed movement, first coming near (descending stand line and progressively augmenting heights) and then coming up (decreasing heights with the isocephalic line and the stand line designing a flight of stairs). This section also has important bearings on the overall meaning and effect of the Royal Buttress (Gilibert 2011, p. 49). First, it acts as a transitional link between the main section of the Royal Buttress and the older procession of armed warriors. In doing so, it dislocates the main accent and effectively transforms the warriors into secondary participants, transferring to the eunuchs their original, more prominent role. Second, the eunuchs act as an extension of the agency of the regent Yariri, surrounding the figure of the future king and singling him out from the group of children represented on the opposite side of the Royal Buttress. In this way, the Royal Buttress visually underscores the political and ritual influence of a selected group of non-royal actors in royal matters. Third, and most importantly for the line of argument pursued here, the reliefs create a visual bipolarity between Yariri’s eunuchs and the king’s brothers. The composition construes a contrasting symmetry between the two groups of young men, further integrating them into the underlying, pre-existing symmetry opposing the line of armed warriors to the beholder’s left and the line of women and young men bringing offerings to the beholder’s right.

Thus, a specific visual and conceptual structure emerges, further contributing to the overall impression of a highly choreographed order. The frontage of the palace is divided into a section dominated by the presence of arms and hunting gears, with explicit allusions to the Storm God, and a section keyed on the presence of special toys and offerings, with connections to the goddess Kubaba. The frontage also comes to deploy a sort of hierarchic diagram of selected stages of aristocratic age classes, gender, and rank, in which, as we shall presently see, male children play a primary role.

6. The Children’s Line and Kubaba’s Oracles

In addition to materialising in concrete and the spectacular form of the transfer of almighty power in the hands of the future ruler, the weapons of the Storm God were also regularly employed as symbols of divine sanction in hereditary settling and promissory oaths (Schwemer 2001, p. 326; Töyräänvuori 2012, p. 152). Their use in Kamani’s investiture may have also played a role in this sense. In a further passage of the corner inscription, Yariri makes an explicit point of Kamani invoking the goddess Kubaba in a solemn oath of protection towards his younger brothers:

“I made him say: ’O Kubaba, you yourself shall make them [the younger brothers] great in my hand”(KARKAMIŠ A6, §21–22)

If we accept Hawkins’ translation, this speech formula appears as an unusual inversion of an oath of loyalty usually required from the king’s brothers in favour of the king. The formula is also a direct internal reference mirroring Yariri’s embrace of Kamani: as Yariri extends his protection onto Kamani, thus Kamani shall extend his protective hand onto his brothers. Claudia Posani has recently underscored the prescriptive and all-encompassing significance of this oath, which binds together in one sentence Yariri, Kamani, the brothers, and the goddess (Posani 2017, p. 105). Its explicit insertion in the narrative speaks of political negotiations, disagreements, and tensions that must have followed the death of the former king, involving primarily the choice of the designated heir and the fate of his brothers. In the ancient Levant, the designation of a successor was a hotly debated matter, and sibling rivalry was a significant cause of anxiety for members of the ruling dynasties (Herrmann et al. 2016, p. 65). On the Royal Buttress, a (selected?) number of the brothers of Kamani are key figures in both the inscription and the reliefs. Their presence aims to conjure political harmony but inevitably also lets shadows of dissent transpire.

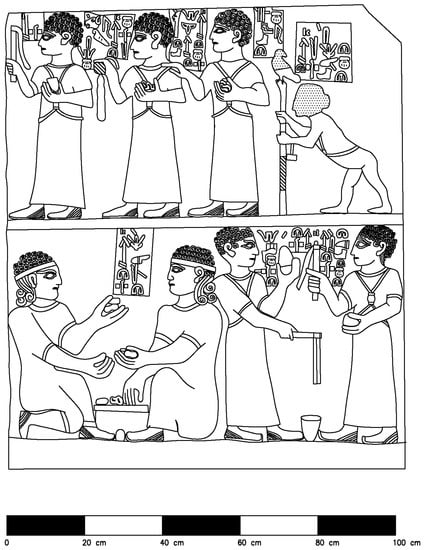

The king’s young brothers are introduced as a group, squeezed into a double register on slab B7b (Figure 8). The introduction of a double register generates an impression of a foreground (B7a) and a background (B7b, B8a), connected by a compositional movement from right to left, following the increasing height and age of the depicted children: a compositional strategy replicating the left-to-right progression of the eunuchs’ line. Eight children in total are represented, identified by name in captions. The ninth boy on the bottom left, the only one without a caption, is intended to be Kamani himself, in a ceremonial stage preceding his ascension to throne and temple, according to the reduplication conventions of ancient Near Eastern visual narratives and following a diagonal and chiastic “narrative” direction.

Figure 8.

Royal Buttress, Slab B7b. Bottom left: Kamani(?) and Sikara, represented as teenagers, throwing astragali on a board; bottom right: Halpawari and Yahilatispa, represented as young boys, setting whipping tops in motion; upper left: princes Malitispa, Astitarhunza, and Tarnitispa, represented as young boys, holding a whipping top and sets of knucklebones; upper right: prince Isikaritispa, represented as toddler, clenching a staff with a perched bird of prey (drawing by Elia Bettini).

The princes are arranged according to five age classes, expressed by varying heights, each reflected in a specific attire and hairstyle, reflecting conventionally defined maturity stages.18 Except for the youngest, the boys play games or hold children’s toys in an unparalleled scene of leisurely pastimes and ulterior symbolism.

7. Knucklebones and Whipping Tops

The children’s line begins on the bottom left, with two teenagers with loose, shoulder-long hair, prince Sikara and Kamani. The boys squat around a small table or a game box, throwing astragali, or knucklebones, with their left hands on a board game. The game is most likely a variant of “Twenty Squares” (Figure 9), a game combining luck and strategy in which two players compete to race their pieces across the board, rolling two astragali as dices, following rules like the modern classic Ludo (Finkel 2007; Rollinger 2011–2013; Wee 2018). In the ancient Near East, “Twenty Squares” was known at least from the third millennium onwards and became particularly popular among the elites of the second and first millennium Levant (Hübner 1992, pp. 72–74; de Voogt et al. 2013, fig. 1; Dehpalavan and Jahed 2021, p. 123).19 The colophon of a Babylonian tablet defines it as “a game for sitting about with friends, fit for nobles” (Finkel 2007, p. 19). Gaming boards and boxes were sometimes decorated with images of archers on racing chariots, hunting deer and wild bulls with dogs, and dressed falcons (van Buren 1937; Caubet 2009). This imagery suggests that, on a ludic level, the players identified with an aristocratic party participating in a competitive activity combining aspects of a chariot race with a staged hunt.20

Figure 9.

Egyptian game box for playing Twenty Squares from a Late Bronze Age Theban burial (Metropolitan Museum 16.10.475a).

Behind the gameboard players, two younger boys wearing short hair and breast straps with an amulet(?), identified as Halpawari and Yahilatispa, are setting whipping tops in motion (Figure 8, bottom right). The whipping top is a spinning top that is set and kept in motion by striking it with a toy whip (Gould 1973, pp. 80–92). Through skillful leashing, the player can influence the trajectory of his top, making it spring and clash against other tops, engaging in battles with one or more opponents. The objective of the game is to keep one own’s top spinning as long as possible, and requires ability and considerable physical stamina.21 Halpawari and Yahilatispa are pictured holding short double whips in their right hands and conical tops in their left hands, while a top is already spinning at their feet. They look each other in the eyes, suspended in a moment of foreboding tension. The top spinning at their feet, conspicuously ignored by the boys, generates a sophisticated contrast between ephemeral movement and an instant frozen in time.

While whipping tops are widely attested in the Classical world,22 the Royal Buttress provides the only known representation from a Near Eastern context.23 Western Asiatic archaeological examples are equally seldom. Their rarity is explained considering that most tops were wooden items and degraded quickly. Surviving ones might have gone unrecognised (some may have been mistaken for spindle whorls)24. However, spinning tops from ancient Egypt, including an elegant inlaid top from the tomb of Tutankhamun, corroborate their widespread use and their symbolic significance in the preclassical Levant (Giuman 2021, p. 1).

Knucklebones and whipping tops appear again in the upper register, where three further boys of identical attire stand in line (Figure 8, upper left). The first from left, identified as Malitispa, holds a whip and a whipping top. The second one, Astitarhunza, carries two astragali in the palm of his left hand and clenches a bag of game pieces(?) in his right hand. The third one, Tarnitispa, is also holding two astragali in his left hand25 while the other hand touches Astitarhunza’s shoulder.

The whole scene has no parallels in ancient Near Eastern art, which devotes little attention to childhood and none to toys.26 The beholder’s gaze is immediately captivated by the incongruence of the depiction. The boys of the Royal Buttress are undoubtedly playing with real toys. However, the monumental context and their restrained, formal body language is disconnected from any idea of amusement. Instead, the scene is reminiscent of the royal children’s portraiture in the Middle Ages and Early Modern times, in which age-appropriate toys are introduced as allusions to status, education, or personal fate (Vaz and Manson 2018). The context makes it evident that the boys are playing “serious games” with a purpose other than mere entertainment. A passage of the corner inscription glosses on this topic:

(For them) who are of fighting (katuna-), then I reverently put knucklebones (katuni) into their hands, (for them) who are of trampling (tarpuna-), then I reverently put whipping tops (tarpuna) into their hands.KARKAMIŠ A6 §14–17

The text, which poses philological challenges, appears to play upon a homophonic connection between the verbs katuna- and tarpuna-, both infinitives expressing actions of violence (Yakubovich 2002, pp. 202–208), and the nouns katuni and tarpuna, characterised by determinatives for objects of bone and wood respectively, expressing the Luwian words for knucklebones and whipping tops.27 We understand that both were gendered toys for boys, thought to require and promote, in duelling challenges, the abilities of an aristocratic warrior. Yariri confers knucklebones and whipping tops to the boys “reverently” (Yakubovich 2020, p. 471) in the formal framework of a religious ceremony.28 Why precisely these toys were picked as ritual objects and used during the ceremony remains debated, with scholars in doubt as to whether they were generic symbols of status (Yakubovich 2019, pp. 551–52) or specific insignia of political ranks (Morpurgo Davis 1986). The combined circumstantial evidence from cuneiform texts and the archaeology of Levantine ritual spaces adds significant depth to the depicted scene.

The embedment of games in rituals finds direct parallels in Akkadian sources, where the whipping top (Akk. keppû29) and knucklebones (Akk. kiṣallu), the latter often mentioned together with game pieces (Akk. passu, cf. Greek πεσσός), are among the very few toys identified by name (Landsberger 1960). They appear in several instances as metaphors of war, particularly in liturgical contexts belonging to the cult of the goddess Ishtar (Kilmer 1991), a deity with multiple analogies to Kubaba of Carchemish (Pedrucci 2008). The textual evidence supports the idea that game contests took place during great state festivals, including royal investiture ceremonies (Annus 2002, p. 56). In one case, there is an explicit mention of whipping top competitions played out before the goddess Ishtar (Reisman 1973, p. 187, l. 64).30 Other sources indicate further that kings and princes would personally take part in such games, which were seen as prefigurations of their dexterity on the battlefield, with the inevitable victorious outcome proving the legitimacy of their position (Annus and Sarv 2015).31

Although most cuneiform texts evoke spectacular and carnivalesque atmospheres, some indicate that there was a serious side to knucklebones and whipping tops. In the Neo-Assyrian religious tale Ishtar’s Descent to the Netherworld, the deity is described as mukiltu ša keppê rabûti, i.e., the “holder of the great whipping tops”, which apparently gave her the power of “stirring up the waters of wisdom” (Lapinkivi 2010, pp. 49–54). An 18th century administrative text proves that a whipping top was kept in Ishtar’s temple at Mari on the Syrian Euphrates and ritually anointed with perfumed oils (ARM 7 79:4, quoted in Goodnick Westenholz 2004, p. 15). Knucklebones and a whipping top appear together in dream omina (Oppenheim 1956, p. 286) and incantations as taboo cult objects (Geller 2008). Their attribution to Ishtar may find an explanation in the fact that, at Mari and in Assyria, the goddess was an oracular deity. Recently, Matthew Susnow and colleagues made a strong argument for a connection between the whipping top, knucklebones, and divination practices, referring in particular to numerous caches of knucklebones found in cultic contexts throughout the Levant (Susnow et al. 2021).32 When the contexts of these caches can be ascribed to a specific deity, it mostly is a female one of the “mother goddess” kind, particularly in Anatolian sites.33 While some of these caches may be votives, others expressly point to divination with game boards. In Cyprus, at Early Iron Age Kition, knucklebones and gaming tokens were found together with a monumental game board in the temple’s main hall, near its sacred hearth (Lamaze 2022). The same situation is closely replicated at Kilise Tepe in Cilicia, in a nearly contemporary Luwian shrine (Postgate and Stone 2013).34

These contexts dovetail with the general evidence that, from the late second millennium onwards, Twenty Squares and cognate board games based on throwing knucklebones were not only played for leisure, but also employed as divination tools (Hallo 1993, pp. 85–87; Finkel 2007; Wee 2018). This use is confirmed by the existence of board games shaped as liver models for instructing extispicy, by a commentary to the rules of the game and by allusions in texts. For instance, in a letter of praise to king Esarhaddon, the crown prince of Assyria, Ashurbanipal wishes to be granted favourable outcomes at Twenty Squares, connecting this to the military success of his father (Livingstone 1989, p. 57). Such oracular games, including the one depicted on the Royal Buttress, seem to be variants of casting lots, a ritual habit otherwise attested in Hittite, Levantine, and Assyrian divination used to reveal the fate of individuals and appoint them to priestly or political offices (Finkel 1995; Haas 2008, pp. 19–21, 25–27; Taggar-Cohen 2002; Warbinek 2019).35 Furthermore, in Hittite ritual practices, oracular inquiries were used to determine favourable dates for the enthronement date of a new king, double-checking the responses using different oracular techniques (Mouton and Gilan 2014, pp. 101–2).

In sum, circumstantial evidence indicates that, on the Royal Buttress, Kamani’s brothers are manipulating oracular toys with the intent of obtaining favourable omens and political appointments for themselves and their older brother, the king. An analogous decoding key also applies to the youngest depicted children.

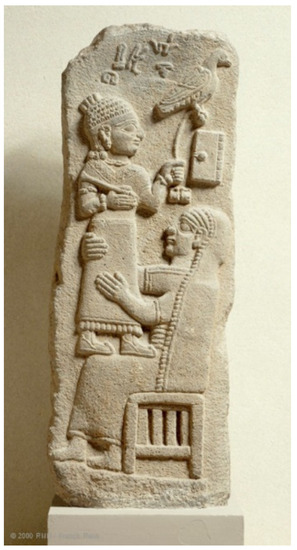

8. A Bird of Prey

Last in line in the upper register, a nude toddler with neck locks,36 wearing only the same breast strap as his brothers, is identified as Isikaritispa (Figure 8, upper right). In a posture probably intended to represent the growing body and the uncertain steps of a child learning to walk,37 Isikaritispa clenches a staff on which a small bird of prey is perched. The bird, which has the size and silhouette of a kernel or a pigeon hawk, is kept on a leash, with a spool(?) hanging from the child’s left wrist. Similar apparatuses, consisting of a leash, spool, and staff, were used for keeping falcons, particularly in North Syria and Turkey, where falconry was extensively practiced by the upper class since at least the mid-second millennium BC.38 The most detailed images of falcons on a leash appear on a ceremonial scene and a funerary stele from South-Eastern Turkey, both approximately contemporary to the Royal Buttress (Orthmann 1971, Sakçagözü A/7 and Maraş D/4). The funerary stele in particular (Figure 10) represents an elaborately dressed boy on the lap of his mother (the deceased). He holds writing implements and a falcon on a leash, evidently an item of his aristocratic upbringing and perhaps a symbol of his inclinations, abilities, or job specialty (as proposed by Radner 2009).

Figure 10.

Funerary stele from Maraş representing the deceased and her son, with a trained bird of prey (© 2000 RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre)/Franck Raux).

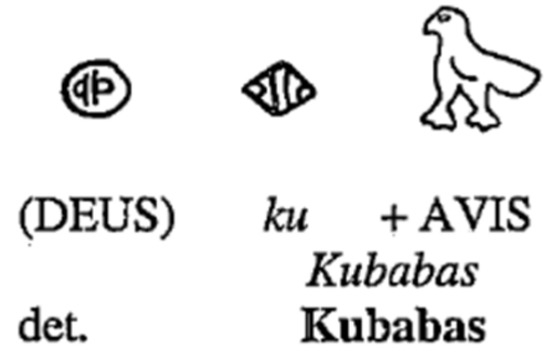

We cannot rule out that, at Carchemish and surroundings, bird pets were used to amuse toddlers. However, any serious dealings with falcons must begin at a later age than Isikaritispa’s.39 On the Royal Buttress, Isikaritispa’s bird, much like the toys of his older brothers, appears to have both a ludic and a ritual significance. On one hand, the scene may evoke special reach-and-grasp games for toddlers organised upon the occasion of civic ceremonies, such as those represented on miniature wine pitchers from 5th century Athens.40 On the other hand, Isikaritispa’s bird has strong ties to local signature cults. At Carchemish, a bird of prey was the animal symbol of the goddess Kubaba, and the silhouette of Isikaritispa’s bird closely reproduces the Hieroglyphic Luwian logogram used to express Kubaba’s name (Figure 11). This widely-attested icon was certainly familiar for everyone, including foreigners and illiterate persons. A cylinder seal found nearby proves the existence, among other divine standards, of a symbolic assemblage consisting of a bird perched on a staff (Figure 12), which, we may reasonably assume, was a locally revered insignia of Kubaba.

Figure 11.

The Hieroglyphic Luwian writing for the goddess Kubaba (from Payne 2010, p. 74).

Figure 12.

Iron Age seal found in the Ceremonial District of Carchemish (from Woolley and Barnett 1952, fig. 75).

The association between Kubaba and a bird of prey is best understood as part of a broader northern Levantine tradition of birds of prey, especially perched falcons, invested with symbolic meaning and used in rituals both as movable insignia and monumental images.41 Living falcons were also embedded in rituals, as proven by figurines of collared birds from Gordion (Mellink 1964). The habit of keeping live, tame birds for ritual purposes was connected to techniques of divination, developed locally into a specialised body of knowledge at least since the mid-second Millennium (Mouton and Rutherford 2013).42 As opposed to Greek or Mesopotamian diviners (Smith 2013), North Syrian augurs were specialised in solicited omens obtained with captive birds (Haas 2008, p. 28). These specialists, trained locally, were employed as scholars at royal courts and held in great regard.43 Indeed, it appears that royals could be expert augurs, too.44

The specifics of the bond between Isikaritispa and the bird on the perch still escape us. Are we witnessing the commemoration of a ritual game played by a royal child? Did Isikaritispa set off an oracular bird? Does the scene prefigure Isikaritispa’s future role as diviner at the royal court? Is it all of this together? If the perched bird of prey was a divination bird, did the position of its beak (later erased) perhaps encode a specific oracular result, as it was the case in Hittite augury (Haas 2008, pp. 46–47)? The full extent of the practical, symbolic, and allegorical meanings is still far from sufficiently understood.

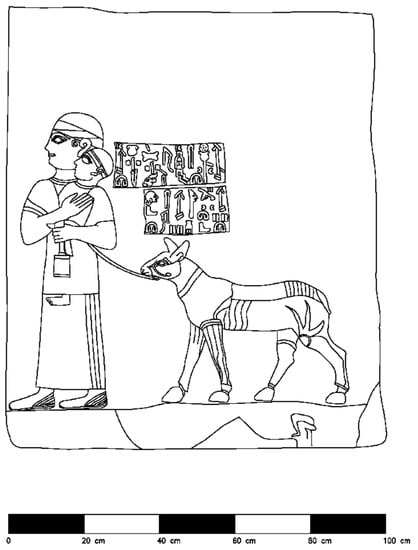

9. A Seal and a Donkey Foal

Far to the right on the last large slab of the section, a grown-up with a simple garment and a shaved head with a headband45 carries a baby, also wearing a headband (Figure 13). The baby is wrapped around the carrier’s body, tied in swaddling clothes or set in a baby’s sling.46 The accompanying caption reads:

Figure 13.

Royal Buttress, Slab B8a: unidentified official carrying the infant prince Tuwarsais, holding a seal(?) and leading a donkey on a leash (drawing by Elia Bettini).

“This (is) Tuwarsais, the beloved, the righteous, the prince proclaimed for pre-eminence.”(KARKAMIŠ A7, §14)47

Convincingly, Hawkins refers the caption to the baby and proposes that Tuwarsais is the designated successor of Yariri (Hawkins 2000, p. 129). If Yariri was indeed a eunuch, as generally assumed, then the baby boy could not be his biological offspring. In fact, the image and text suggest that Tuwarsais was the youngest biological son of the deceased king Astiruwa. The caption must thus refer to the baby’s formal adoption by the kingmaker for the purpose of having an heir.48 If events unfolded this way, considering that Tuwarsais is portrayed as a child of one year or less, the depicted ceremony must have occurred shortly after his father’s death, as already surmised above. Henceforth, Tuwarsais disappears from the historical record (perhaps an untimely death?). Eventually, Yariri was succeeded by a certain Sastura, who, early on in his career, acts as Kamani’s “first servant” and then, surprisingly and presumably after Kamani’s death, becomes king in his own right (Hawkins et al. 2013). This turn of events is significant and may foreshadow a repeated habit of creating blood relations between the king of Carchemish and his prime minister (Hawkins 1979, p. 172), adding credibility to Tuwarsais’ biological royal paternity. This intricate dynastic framework might also explain the compositional and plastic accent conferred to this slab.

The other depicted character, the baby’s carrier, is a male figure (Özgen 1989) and not, as proposed elsewhere, a wet nurse.49 A closer look at his specific, understated attire and prominent role further suggests that he is not just another eunuch attendant but a high functionary, perhaps the “Chief Scribe” (Luwian tuppalan-uri, Akk. rab ṭupšarri), as may also be the case of a similarly dressed figure saluting the king with writing implements on a nearly contemporary relief from Zincirli.

The baby’s carrier additionally juggles a square object hanging from a cord and leads an animal on a leash. Both details take up a significant portion of the composition. I propose to see in the object a large official seal, in close analogy to a 7th century Assyrian relief depicting an Assyrian official parading the royal seal of the Babylonian king Šamaš-šumu-ukīn as a war spoil (Figure 14, Novotny and Watanabe 2008). On the Royal Buttress, the form of the depicted object, perhaps somewhat magnified for readability, corresponds to the Luwian logogram for “seal” (Luwian *sasa-; Laroche 1960, pp. 168–69, Figure 15). In the Luwian-speaking cultural milieu, seals were cardinal legal instruments50 officially endowed, among others, to rulers and state officials.51

Figure 14.

The royal seal of the Babylonian king Šamaš-šumu-ukīn as identified by Novotny and Watanabe 2008 (photograph by Watanabe, published in Novotny and Watanabe 2008, p. 116).

Figure 15.

The Hieroglyphic Luwian logogram for SIGILLUM, “seal”.

The retrieved Iron Age seals inscribed with Luwian Hieroglyphic captions are consistently valuable objects cast in bronze or gold or carved out of translucent, multi-coloured hard stones. Approximately one-third of them52 are inscribed with the name of the goddess Kubaba. According to Claudia Mora, “these specimens had special functions of a high level, either in the political or religious sphere or as amulets or jewels” (Mora 2020, p. 362). We do not have direct proof of how exactly and by whom the “seals of Kubaba” were employed. However, they compare to other, better-known divine seals of the Late Bronze and Iron Age Near East (Opificius 1957–1971). Divine seals, mostly large-sized items, were thought of as belonging to gods and were usually kept in temples. They were employed to seal formal treaties and agreements, particularly those involving oaths and regulating matters of succession.53

In light of this evidence, the seal held by the baby’s carrier might be tentatively identified as the official seal of Kubaba of Carchemish, to be applied on a written document fixing the terms of Kamani’s succession, of his oath of protection of his younger brothers and, in particular, of Tuwarsais’ future appointments.54 One might furthermore surmise that, as with the other particular items featured in the Royal Buttress, this seal was not only a cult object but also a symbol of authority kept by a person holding a specific office, perhaps that of the child’s carrier or, if intended as regalia of investiture, the child’s itself.

Last in line, occupying a considerable share of the surface, is the leashed animal. The animal’s harness, its relative size, the details of its hooves and its divergent, pointed ears point to an equid, probably a donkey foal. The animal appears on the scene in its ceremonial and performative significance as a sacrificial animal, according to compositional conventions documented at Carchemish and elsewhere (Orthmann 1971, pp. 353–57). In the Levant, the ritual killing of young animals, particularly donkey foals, was performed specifically upon taking oaths and concluding covenants (Way 2011). In these rituals, the slaughtering of the animal was performed in front of the oath-takers and symbolised the fate that would befall the oath’s violator (Faraone 1993; Scurlock 2012). This moment of the ceremony was topical to the point that, at 2nd millennium Mari, the expression “to kill a donkey foal” (Akk. ḫayaram qatālum) came to be a synonym of “to make a covenant” (Way 2011, pp. 75–78, with ref.). I surmise that, on the Royal Buttress, the animal is introduced in reference to the oath of brotherly protection that Yariri imposes on Kamani, which, in all effects, solemnised a pact of succession.55

10. Harnessing Children against Political Dissent

If the interpretation advanced here is correct, the Royal Buttress is the best-preserved source for a spectacular ritual combining cultural memories of the Hittite Empire with original trends in elite ceremony, including a novel formal attention to childhood as a signature moment of one’s lifetime.56 Beyond ritual and belief, the involvement of royal princes and eunuch officers into the king’s accession to the throne appears to have had political reasons. The unique visual insistence on children and childhood ties up with contemporary written sources elaborating on the trope of the young prince protected by the gods and exalted among his brothers, who were also his most dangerous competitors (Posani 2021, pp. 130–31).57 In the case of Carchemish, this rhetoric was advanced by a kingmaker who, in doing so, removed and appropriated older monuments, vividly suggesting a contested narrative of the status quo and, perhaps, the existence of dissenting voices left out of the picture. In this perspective, the Royal Buttress advances a double political discourse. First, it seeks to cement the loyalty of royal family members by letting potential future rivals generate legitimising oracular responses in a highly affective, competitive framework. Second, it testifies to the increasing power held by eunuch court officials, as well as their own struggle to establish legitimacy and, perhaps, a hereditary status for their cardinal offices. On the Royal Buttress, eunuch officials and the king’s brothers are represented as essential counterparts, interlinked through kin relations and sanctioned in their power through their role as ritual and military leaders. Key aspects of this political discourse must have raised significant controversy: at a certain point after the erection of the reliefs, the face of Yariri and Kamani’s ruler staff were partly chipped off by violent blows, Isikaritispas’ face was accurately polished away, and both Kubaba’s bird and the Storm God’s double axe were removed with a chisel. Although the ratio behind these actions remains obscure, they nonetheless reveal the existence of a considerable degree of shared knowledge and specific understanding of the reliefs’ general message and individual details.

11. Heraclitus’ Boy and the Philosophy of Childhood in the Levant

On a broader level of meaning, the Royal Buttress documents how the material and sensory world of childhood may be used to heighten the affective efficacy of formal ceremonies and cults. In the ancient Near East, the ritual employment of children and toys is, in earlier periods, sparsely attested in Egypt (Szpakowska 2020) and Crete (Chapin 2020). Then, in the early first millennium, it also becomes visible in Israel (Garroway 2017), Cyprus, Northern Syria, and, somewhat later, on the Phenician coast. Most recently, a particularly noteworthy study re-examined an ivory doll from 5th century Carthage, proposing its use in domestic rituals of Levantine origin (Orsingher and Rivera-Hernández 2021). Indeed, by the 5th century the incorporation of children and children’s toys in rituals, particularly divinatory practices, establishes itself across the Mediterranean (Johnston 2001), turning into a long-term cultural feature (Grottanelli 1993; Sintomer 2019).

This historical trend is rooted in the profound ambiguity and liminality of the world of childhood, which pre-modern societies often saw as intermediary between grown-ups and other-worldly spheres (Iijima 1987). Ambiguity and liminality come forcefully to the fore in games and, metonymically, in toys. Children, when they play, walk the line between reason and impulse, reality and make believe, drama and fun, pleasure and violence. They also test their abilities, character, and luck. Adults observe them and reminisce. They may make sense of the world of children as a microcosmos of adulthood, where future destinies are forged, prefigured and revealed in riddles. This conceptualization was common in the Greek-speaking world of 6th century BCE, when Heraclitus wrote the famous fragment quoted in exergo. Heraclitus’ playing child reflects a highly sophisticated appreciation of children’s play as a creative force, political education, and oracular practice (Bouvier and Dasen 2020). Similar ideas resurface in a wide geographical area in the contemporary images of Achilles and Ajax playing a board game before meeting their destiny in battle (Baldoni 2017; Bundrick 2017).58 Indeed, Heraclitus may have been directly inspired by oracular games played by children at the Artemision of Ephesos, a cult place of Luwian origins he used to frequent and where numerous astragali have been retrieved (Greaves 2013; Franz 2017).

The “serious games” of Yariri’s children appear to reflect a philosophical and religious framework not too different from Heraclitus’ and other early Greek thinkers of Asia Minor. Although detailed knowledge of North Syrian philosophical notions is lost, the repeated use of metaphors for childhood in the epigraphic record of Carchemish and its neighbours (Posani 2017, 2021, pp. 69–70) underscores the profound meaning attached to the early ages of life. In this perspective, the Royal Buttress is not only the expression of a political agenda and the ritual endorsement of specific individuals. If we keep the hieroglyphic captions out of the picture and read the picture from right to left, a cinematic representation of a man’s path from birth to adulthood appears, where the individual destinies are fixed by divine will in competitions and challenges among one’s peers.59 The composition may even directly refer to familiar Egyptian and Levantine tropes of the ages of life as a (board) game played against Death and Fate (Dasen 2020). I suspect that some ancient viewers may have looked past politics, sought out indirect parallelisms with the royal sons and themselves as “sons of Carchemish”, as the male citizens of the city were commonly addressed,60 and additionally appreciated the Royal Buttress as the visualization of a shared discourse about rearing, education, decorum, individual destiny, and divine intervention.

12. Conclusions

The Royal Buttress at Carchemish stands out as one of the few depictions of children playing with toys in ancient Near Eastern art and perhaps the only one foregrounding children’s agency. Its unique imagery undoubtedly reflects the everyday ludic activities of elite boys, including playing board games, spinning tops, and keeping pets, as attested in contemporary texts and material culture. However, a close reading of the reliefs and an attentive pondering of comparative evidence reveals that the children of the Royal Buttress are special children using toys in an extraordinary situation. At a first glance, the reliefs appear almost as a snapshot of a carefree and sophisticated nursery—a first impression imbued with happiness and decorum that was certainly consciously pursued by the artistic sponsor. However, upon further scrutiny the children of the Royal Buttress are revealed as royal princes co-opted into a controversial political ritual, with toys handed out to them as a sacred duty, in a stark reversal of any notion of fun. According to the thesis advanced here, the young princes employed their toys as oracular instruments at a salient stage of a royal investiture ceremony, sanctioning the primacy of the heir apparent, with whom they had to negotiate a dangerous relationship. The choice to commemorate the princes with their toys also reflects a still poorly understood ancient philosophical discourse on the entaglement between life’s phases, social competition, and individual destiny.

From the point of view of methodology, the approach followed here illustrates how monumental art and architecture can be unlocked beyond disciplinary boundaries through the integration of visual semiotics, building history, and the social sciences. Specifically, the case of the Royal Buttress exemplifies how past visual sources from lesser-known historical and geographic contexts may open new perspectives on broader matters of material religion and the anthropology of art. It shows how liminal social groups and everyday items, such as children and their toys, may sometimes play critical roles in rituals precisely because of their ability to materialise multiple meanings and evoke affective feelings. It also spotlights the complex entangled sociological and psychological connections between the norms of rituals, the rules of games, the power of individual agency, and the realm of chance.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Henceforth, all absolute dates are intended BCE, if not stated otherwise. |

| 2 | I refer to Rollinger 2011 for a detailed introductory overview. Participants were mostly young men—children are seldom explicitly involved, although Hittite local cults occasionally mention their active presence (Cammarosano 2018, p. 156). |

| 3 | The translation of the two terms and their contextual implications have been much discussed: a review of the literature is given by Rollinger (2008), who, together with most commentators, settles for “ball and mallet”. |

| 4 | The details of the early excavations led by Leonard Woolley on behalf of the British Museum are published in Woolley and Barnett (1952, pp. 192–97). |

| 5 | While a detailed analysis of the building history of the Royal Buttress is beyond the scope of this article, it shall be noted that its construction involved the reuse of older images to craft the new ones as well as the dismantling and disposal of the image and long inscription of a previous, early 9th century ruler, Katuwa. These codified acts doubtless aimed at re-writing the official dynastic history. One has just to consider that Katuwa’s inscription was disparagingly re-used upside down as paving stone of a public gate nearby, a typical example of calculated humiliation, with parallels at several contemporary sites, including Tel Dan, Alalakh, Malatya and Carchemish itself. In general, the addition of the Royal Buttress to an already existing monumental landscape was a pondered action, investing the older reliefs with new and changed meanings. |

| 6 | Older comparanda are mainly found in images of children in Imperial Hittite art, including a golden pendant featuring a seated goddess with a naked child on her lap (Blanchard 2019, p. 63, with ref.). The scene as a whole can be compared with the bottom register of the side face of the left tower at Alaca Höyük, possibly depicting a line of royal children of different ages (and corresponding hairstyle), including a naked toddler(?), together with the Hittite king. In a broader sense, the image can be filed among other figurative “dynastic diagrams” presenting the king together with the crown prince with one or more of his brothers, relatively well documented in third-millennium Sumer (Romano 2014; see also Suter 2000, St. 10 and 48) but also in the Levant of the first-millennium, most notably the 7th century “Victory Steles” of king Esarhaddon of Assyria (Nevling Porter 2003, pp. 59–79). Something comparable might be envisaged also on a 9th century series of reliefs set up at the Outer Citadel Gate of Zincirli (Gilibert 2011, pp. 66–67). However, none of the quoted examples specifically depict toys or children at play. The regionally and chronologically nearest examples in this sense come from Phoenician suburban sanctuaries of Tyre and Sidon in Persian and Hellenistic Lebanon (Bostan el-Sheikh and Kharayeb in particular; on the latter, see now Oggiano 2022). |

| 7 | Labelling follows Woolley and Barnett (1952). |

| 8 | Yariri’s mace is a particularly interesting case. This object, similar to two slightly different and less elaborate maces held by other attendants, appears to be a symbol of rank introduced in North Syria from Assyria (Albenda 1988, pp. 16–17). Several examples of these maces have been retrieved from Assyrian palaces and temples, some of them inscribed with the owner’s name or with an ex-voto dedication to a god (Niederreiter 2014). The maces were decorated with lion heads (it is possible to recognise this detail in Yariri’s relief) and were cast in bronze and silver or smelted iron in order to create a striking bicolored artefact. They were specific insignia held by the highest court dignitaries, often eunuchs appointed as provincial governors or similarly top positions. These insignia could be bestowed upon the chosen dignitaries during the ceremony of royal investiture (Niederreiter 2014, pp. 584–85). Evidently, this range of meanings and uses was perfectly familiar to Yariri, who was in close contact (and, at least once, in direct military conflict) with the commander-in-chief of the Assyrian army Šamši-ilu. Šamši-ilu, who was a eunuch of probable local Syrian origin, held court in nearby Kar Shalmaneser, twenty kilometres downstream from Carchemish. Inside the royal palace of Kar Shalmaneser, wall paintings and stone reliefs illustrate Assyrian court etiquette and attest the widespread employment of lion-headed maces as power and rank insignia. Yariri must have considered the Assyrian mace an item of great power and prestige. Did he adopt it to commemorate specific contacts or formal agreements with Assyria? Was it rather a matter of cultural appropriation? Did these maces play a special role in ritual? The question requires further study, focusing in particular on parallels with Levantine contexts. At Tel Dan in the Jordan Valley, for example, a similar mace was deposited on an altar inside a temple’s wing where, apparently, burnt offerings and divination by game of chances also took place (Oggiano 2005, pp. 92–96), both elements that, as we shall see, played a pivotal role on the Royal Buttress as well. |

| 9 | This technique du corp appears significant. On an earlier funerary stele from Ördekburnu (Lemaire and Sass 2013) and on slightly later reliefs from Karatepe (Çambel and Özyar 2003, reliefs A/8 and A/28), a long-robed dignitary and hero hunter respectively also clench a mace upside down. On the Assyrian reliefs of Til Barsip, conversely, court dignitaries and officials are balancing the maces from the bottom up, keeping them awkwardly vertical with their palms, with the help of a leather loop. We may safely assume that these poses were formally defined and conveyed a precise message. |

| 10 | Biceps rings cast from precious metals are likely to have been heavily connoted objects produced locally. Earlier images of royalty at Carchemish do not include biceps rings but the royal iconography at neighbouring Zincirli (Cornelius 2019), Tell Tayinat (Harrison 2017), Sakçagözü and Malatya (Mori 2021) did, and sometimes prominently so, with examples stretching from the 10th century (Zincirli) to the late eight century (Sakçagözü and Malatya). In Assyria, golden biceps rings (Akk. semeru, ḪAR.MEŠ KÙ.GI) were introduced as divine attributes and material prerogative of the Assyrian royal inner circle in the early-ninth century, as shown on reliefs of the palace of king Ashurnasirpal II (completed around 865–859). On the same reliefs, they also appear at the biceps of the Levantine dignitaries bringing “audience gifts” (Akk. nāmurtu) to Ashurnasirpal and rings make out a significant part of the gifts themselves (Meuszynski 1981, tabs. 5–6, reliefs D5–8 and E1–4; Cifarelli 1998, p. 215; Degrado 2019, pp. 117–19). One such ring is expressly singled out as a significant item of the enormous tribute (Akk. madattu) negotiated by Ashurnasirpal from Sangara, king of Carchemish, during a military campaign in Northern Syria sometime between 875 and 867 (Greyson 1991, A.0.101.1, iii 65). It is interesting to note that, in the 7th century, the royal inscriptions of Ashurbanipal mention the formal conferment of gold rings as an act of royal investment of, specifically, Levantine allies and vassals (Novotny and Jeffers 2018, e.g., Ashurbanipal 11, ii 11, ii 81–94). On the highly symbolic meaning of Assyrian bracelets, (cf. also Collon 2010). |

| 11 | In this context, the Luwian verb “PES2+PES”tara/i-pa-ta5” recalls an aggressive bull trampling over the land with its hooves (Yakubovich 2002, pp. 202–208), a metaphor for subjugation and destruction by military might. It also connects with the metaphor of the Storm God (and, by the extension, of the ruler) as a wild bull (Watanabe 2002, pp. 57–64, and more specifically Herbordt 2010). The figure of speech of the king placing enemies under his feet is discussed in Posani (2021, p. 287). |

| 12 | It is unclear how long after king Astiruwas’ death this ceremony took place, and which consequences bore on Yariri. An early formal enthronement of Kamani immediately following the death of his father Astiruwa seems likely and might have inaugurated a co-regency, leaving Yariri the upper hand—and his titles—for a relatively long period of time. |

| 13 | On the Hieroglyphic Luwian amu-figure and its value as “imagetext”, (cf. Aro 2013, pp. 236–44; Mazzoni 2013, pp. 475–76; Payne 2016; Hogue 2019). |

| 14 | When not stated otherwise, English translations are derived by the Corpus of Hieroglyphyc Luwian inscriptions (Hawkins 2000). |

| 15 | The fragment KARKAMIŠ A17b, belonging to the reign of Kamani, replicates the image of an adult leading a child by the hand, indicating the relative persistence of the specific figurative topos. |

| 16 | The parallelism between Yariri’s rhetoric discourse and that usually applied to dynastic tutelary gods at Carchemish, especially Kubaba, cf. the inscriptions Karkemish A21 and A20b, where a king of the late-8th century declares: “Kubaba …-ed [me?] the hand, [and me(?)] she caused to sit on my paternal throne, […] she(? ) caused to embrace [me(?)], […] and she guarded me (as) a child […]” (Hawkins 2000, p. 160). |

| 17 | Or, alternatively, the rolling thunder (Schwemer 2008). |

| 18 | The age classes of Kamani’s brothers find a pertinent parallel in Neo-Assyrian cuneiform texts, especially the so-called “Harran Census”, which independently prove that, in Iron Age Northern Syria, children and prepubescent boys were routinely classified according to their height and nursing needs in five fixed age classes: suckling (Akk. ša zizibi); weaned (Akk. pirsu); 3-span child (Akk. ša 3 rūte, c. 83–84 cm, 3–5 years); 4-span boy (c. 110–112 cm, 6–11 years); and 5-span boy (c. 135–140), i.e., young teenagers (Fales 1975, pp. 344–46; Galil 2007, pp. 309–10, with ref.). This classification also finds close correspondences in Assyrian narrative reliefs (Riley 2020). A particularly fitting comparison is a relief from Niniveh illustrating a royal acclamation scene in which the Assyrian šut reši-eunuch official publicly introduces Ummanigash, the newly proclaimed king of Elam, in front of a large audience, accompanied by a choir of children divided in height-related age classes (Reade 1983, p. 63, fig. 93). An extensive overview of iconographic markers of age classes in ancient Near Eastern has been compiled and discussed by Parayre (1997). For Egypt, see Harrington (2018). |

| 19 | The game’s fortune at Yariri’s times is attested, among others, by archaeological examples found at the royal courts of Carchemish’ immediate neighbours, including Hama (Riis 1948, pp. 174–76, fig. 216; Fugmann 1958, pp. 177, 179, fig. 216), Zincirli (Wartke 2005; for sets of astragali, see Andrae 1943, pp. 122–23) and Tell Halaf (van Buren 1937; Hrouda 1962, pp. 8, 21, no. 43, 52, table 7, 43b). More examples of gameboards for “Twenty Squares” have been found at Kamid el-Loz, Hazor, and Tell Beth Shemehs (Sebbane 2016, p. 643). The Beth Shemesh example also shows that game-boards could be considered personal items, and inscribed with the name of the owner. |

| 20 | Excellence in similar hunting games, in which young aristocrats were apparently expected to prove themselves, was equally memorialised on monuments and considered proof of divine favour, as attested in Malatya (Hawkins 2000, pp. 318, 321–22, 327; Orthmann 1971, Malatya B/1–3). Written sources additionally suggest that Twenty Squares simulated war strategies (Wee 2018, n. 21), but this is an insubstantial discrasy, given that, in the ancient Near East, war and the hunt were considered essentially analogous. |

| 21 | In nineteenth century England, the game was recommended to activate the circulation in winter (Gould 1973, p. 10). |

| 22 | I refer to the excellent discussion in Giuman (2021), with further references. (See additionally Hübner 1992, pp. 86–89; Cruccas 2014). |

| 23 | A toy whip of the same kind may be tentatively recognised on a contemporary funerary stele (Orthmann 1971, Maraş C/1). |

| 24 | Cf., as possible candidates, conical Early Iron Age stone “whorls” from Alişar Hüyük, Turkey (von der Osten 1938a, pp. 98, 173). |

| 25 | The repeated association of astragali with the left hand of the players is certainly meaningful, but its precise references are unknown. On the symbolic association of the left hand in Hittite culture with the male gender, (cf. Posani 2021, pp. 97–98). |

| 26 | For recent literature on children and childhood in Mesopotamia and the Levant, (cf. Harris 2000; Nadali 2014; Flynn 2018; Garroway 2018, pp. 54–55). |

| 27 | In this sense, cf. Luwian tarpuna with Latin turbo. |

| 28 | The obscure 8th century funerary inscription KARKAMIŠ A5a, which belonged to a member of the city’s elite and may have originally stood in the temple of Kubaba on the acropolis, seems recall a similar religious procedure, apparently initiated by the author’s parents, involving his elder brother and fixing the author’s destiny (Hawkins 2000, p. 182). |

| 29 | For the translation of Akkadian keppû as “whipping top” and not, as proposed by Landsberger (1960, pp. 121–24), as “skipping rope”, (see Dalley 2000, p. 130, n. 80; Lapinkivi 2010, pp. 49–54). |

| 30 | We may find further attestations of whipping tops in ritual performance if we consider that the Akkadian word pilakku, i.e., “spindle”, may in certain contexts denote a spinning top, especially when associated to whips. This may be the case in a Neo-Assyrian hymn to the goddess Nanaya, where the kurgarru, a devotee with martial character, amuses the goddess ina palaqqi ṭeri tamšēri, which could either refer to musical activities (Lucio Milano, personal communication) or, hypothetically, could also translate as “hitting ‘spindles’ with whiplashes” (Livingstone 1989, p. 13, i. 10, with different interpretation). |

| 31 | Annus and Sarv report the anecdote of Darius challenging Alexander by sending him a mallet and a ball (or, in another version, perhaps a whip and a top(?)). It ensues a hermeneutic battle about how to decode the symbolic meaning of the objects—Alexander proposes to read them as a good omen, prefiguring his conquests. In another anecdote, the Persian crown prince is depicted as excelling among his brothers as a the most daring ball player (Annus and Sarv 2015, pp. 288–89). |

| 32 | For overviews and discussions of knucklebones from various Levantine contexts, and their use in divination, (see also Hübner 1992, pp. 43–62; Gilmour 1997; Minniti and Peyronel 2005). For an exceptional hoard of 406 astragali at Tel Abel Beth Maacah in northern Israel, (cf. Susnow et al. 2021). The association of whipping tops and divination in ancient Near Eastern contexts is based entirely on indirect circumstantial evidence. It is, however, securely attested in ancient Greece (Giuman 2021, pp. 38–41). Massimo Maiocchi calls my attention to the fact that the stellar trajectories of the planet Venus, the celestial counterpart of Ishtar, were regularly referred to in planetary omina and may resemble those of a spinning top (Maiocchi, personal communication, 10 May 2022). |

| 33 | On the use of knucklebones for divination in Western Anatolia and its connection with Luwian culture, (see Greaves 2013); for astragalomancy at Alishar Hoyuk, (see von der Osten 1938a, pp. 243, 250, 427; 1938b, p. 101); at the Iron Age Phrygian mother goddess temple at Oluz Höyük, (see Onar et al. 2022); at the Artemision of Ephesos, (see Hogarth 1908, pp. 190–92, pl. 36); at the oracular shrine of a mother goddess in the Uyuzdere Grotto near Metropolis, (see Meriç 1982, pp. 38–40, 101–103); at archaic Didyma, (see Greaves 2012). |

| 34 | To be also compared with the divinatory assemblages at Late Bronze Age shrines in Armenia described by Smith and Leon (2014). |

| 35 | At 13th century Emar on the Syrian Euphrates, the god Baal’s High Priestess was chosen by casting(?) “lots” (Akk. pūru) in the temple, in front of the god’s image (Fleming 1992, p. 175). Most significantly, the divination of individual destinies specifically in relation to the choice of the crown prince is a topic in the Assyrian royal inscriptions. In the opening section of his longest inscription, narrating the circumstances of his elevation to crown prince, Esarhaddon (reigning 681–669 BCE) recalls a situation with close parallels to Carchemish: “(my) father, who engendered me, elevated me firmly in the assembly of my brothers, saying: ‘This is the son who will succeed me.’ He questioned the gods Šamaš and Adad by divination, and they answered him with a firm ‘yes,’ saying: ‘He is your replacement.’ He heeded their important word(s) and gathered together the people of Assyria, young (and) old, (and) my brothers, the seed of the house of my father. Before the gods Aššur, Sîn, Šamaš, Nabû, (and) Marduk, the gods of Assyria, the gods who live in heaven and netherworld, he made them swear their solemn oath(s) concerning the safe-guarding of my succession.” (Leichty 2011, Esarhaddon 1, ll. 10–19). His successor Ashurbanipal (669–631 BCE) describes a similar procedure more succinctly: “the great gods in their assembly] determined a favourable destiny as my lot [when] I [was a ch]ild” (Novotny and Jeffers 2018, Ashurbanipal 115, l.3, with variations in several other inscriptions). |

| 36 | The habit of keeping recently toilet-trained toddlers naked is attested throughout the ancient Near East, (cf. Harris 2000, p. 22, n. 118). |

| 37 | To be compared with images of crawling toddlers in Egyptian and Greek art (Harrington 2018, p. 543). |

| 38 | A hand-held bird perch is represented as a divine attribute on an Old Hittite seal (Boehmer and Güterbock 1987, p. 56, fig. 39, discussed in Kozal and Görke 2018, with extensive references to birds of prey in Hittite texts and imagery). For a specific discussion of falconry gear in ancient Anatolia, (see Canby 2002, pp. 167–74). |

| 39 | In the “Collection of the Science of Falconry” (AD 1240), Muslim scholar Isa al-Asadi reports that Iraqi children would learn the principles of falconry by playing mock hunts, training kernels and pigeon hawks on sparrows and larks (Trombetti Budriesi 1999, p. xxi). |

| 40 | For an image on an Attic chous closely replicating Isikaritispa’s iconography, now in the Art Institute of Chicago, (see Fröhner 1892, p. 55, no. 125). On a broader level, the association of toddlers and small birds with ceremonial and religious undertones is attested in Hellenistic Egypt (the naked child Horus holding a pet hoopoe). More on the symbology of children holding hoopoe in (David 2014; Marshall 2015) and the Christian Levant (baby Jesus playing with a goldfinch on a string: Friedmann (1946)). |

| 41 | As attested by a golden sceptre from Kourion, Cyprus (Goring 1995), by the ivory wand topped with a falcon known as the “hawk-priestess” from Ephesus (Akurgal 1961, p. 206) and the colossal statue of a perched falcon from Tell Halaf, Northern Syria. |

| 42 | On Hittite bird divination, (cf. Ünal 1973; Archi 1975). |

| 43 | In Assyria, North Syrian “bird-watchers” (Akk. dāgil iṣṣūri) enjoyed a high status as part of the king’s entourage (Radner 2009). |

| 44 | In the thirteenth century, bird-diviners of Luwian background could occupy top positions at the Hittite court. Specifically, Piha-Tarhunta, a royal prince of Carchemish with significant political influence, acted as “Great Augur” and “Scribe of the Army” (Haas 2008, p. 29; Mora 2008, pp. 558–59; Bilgin 2018, p. 328). Seals impressions of Piha-Tarhunta combine several titles, including that of “eunuch.” Since this appears to be the only case of a prince eunuch, Bilgin warns that there may be an homonymy between the Piha-Tarhunta prince of Carchemish and the Piha-Tarhunta Great Augur. The problem has been discussed by Mora (2008), who is doubtful about a possible homonymy. |

| 45 | The person is shaved except for an evidently displayed, short side lock peeking out of his headband. This detail is significant (and shared by other eunuchs). On locks of hair and garment’s hems as critical loci of identity, (see Lynch 2013, with ref.). |

| 46 | For further attestations of this method of carrying babies, (cf. Parayre 1997, figs. 33b,c and 42d). |

| 47 | Translation after Hawkins (2000, p. 129), emended after Melchert (2019). |

| 48 | A practice followed by the “Chief Eunuch” of a nearby polity, as attested by the inscription MARAŞ 14: Hawkins (2000, pp. 265–67). |

| 49 | The character’s role as carrier of a royal prince does compare with that of royal nurses known from other sources (Nadali 2014), but in this case his gender is male and his functions appear to include the cultic offices. |

| 50 | The legal use of seals in formal occasions is reflected in the inclusion of the logogram for “seal” in the composite logograms for “agreement, contract” and “disagreement, litigation” (Hawkins 2000, p. 155; van den Hout 2021, p. 174). I leave to palaeographers to ponder whether the Luwian sign L 371, used to spell or determine concepts connected to the idea of “justice” (see now Melchert 2019) and L 474, the logogram for “eunuch” (Peled 2013), may be a graphic variant of the sign L 327, representing a seal. |

| 51 | As proven by a limited, but increasing number of inscribed stamp seals and seal impressions (Mora 1990; Hawkins 2000, pp. 572–86, with tables 328–333; Kubala 2015; Mora 2020), including a 9th century example recently found at Carchemish in an area not far from the Royal Palace (Dinçol et al. 2014). Seals included stamp seals, cylinder seals and combined forms. |

| 52 | Seven out of a total of sixteen inscribed seals, with reference to the items catalogued in Hawkins (2000), to which we shall add at least the new seal from Carchemish, a red jasper stamp seal found in 2018 at Sirkeli Höyük in Plain Cilicia (Elsen-Novák and Payne 2021), and three seals from Malatya (Mora 2020). |

| 53 | On the seals of Assur on the “Succession Treaties” of the Assyrian king Esahaddon: Watanabe (1985); on the use of divine seals on Hittite treaties: Watanabe (1989); on the seal of Ninurta at Late Bronze Age Emar: Yamada (1994) and Beyer (2001, pp. 430–37); on the seals of Addu and Marduk on a Middle Bronze Age royal adoption contract from Tell Taban (North-Eastern Syria): Yamada (2011); on the use of the seal of the god of justice Ishme-Karab at the “supreme court” of Susa, see De Graeft (2018); on divine seals in the Biblical tradition: Imes (2020). On kings commissioning the production of divine seals, (cf. Lee 1993). |

| 54 | The Hieroglyphic Luwian caption next to the baby may furthermore encrypt a pun in this sense, since the word for “proclaimed”, á-sa5-za-mi-i- (participle of asaza-, Luwian “pronounce, declare”) is spelled with the sign L 19, with the syllabic value <á>, representing a human profile, and the sign SIGILLUM, in its phonetic value <sa5->, which, visually combined one above the other, reproduce in miniature and compacted version the key elements of the image on the relief. An indirect reference to some practice involving both an act of sealing and protection of Kamani’s brothers may be foreshadowed in Karkemish A15b, §16–17, where Yariri proclaims that he “ANTA SASA-ed to the brothers, and to them, to my lord Astiruwa’s children, I extended protection” (Hawkins 2000, p. 131). |

| 55 | Other meanings cannot be ruled out. If the identification of the animal with a donkey foal is correct, we shall consider that donkeys also played a part in scapegoat rituals, and significantly so in rituals aimed at averting illnesses from infants, as illustrated by several “Lamashtu amulets” found in the Levant, including at Carchemish, Zincirli and Arslan Tash. These amulets were incised with images of donkeys symbolically “carrying away” evil influences (Degrado and Richey 2017; Wee 2018). Indeed, the form of these amulets, which were suspended from a cord, is analogous to the object held by the baby’s carrier. This evidence introduces the distinct possibility that the elements of the relief relate entirely to the baby, conveying a specific message of divine and magical protection. Additionally, we cannot a priori dismiss the possibility that both the animal and the infant had been selected to be sacrificed. As in an ante litteram version of the sacrifice of Isaac, the donkey could be interpreted as a sacrificial substitute for the prescribed immolation of a royal child. The sacrifice of royal offspring is documented as a Bronze and Iron Age Levantine practice (Stavrakopoulou 2004, pp. 207–99; Garroway 2018; Wyatt 2019) and may be discussed in a trilingual stele from Incirli, located in modern Turkey halfway between Marash and Carchemish, dating to the second half of the 8th century (Kaufman 2007). Additionally, the wording of Tuwarsais’ epigraph is comparable with Phoenician votive inscriptions connected to child offering. However, the festive ritual and ceremonial circumstances staged by Yariri do not fit the known occasions in which this extraordinary ritual practice was resorted to, and should invite us to ponder such speculations with the greatest caution. |