Abstract

The arrival of new technologies has always presented new challenges and opportunities to religious communities anchored in scriptural and oral traditions. In the modern period, the volume, speed and accessibility of digital technologies has significantly altered the way knowledge is communicated and consumed. This is particularly true for the way religious authority is constructed online. Using in-depth fieldwork interviews and survey findings of Australian Muslims, this article examines the way religious actors, including imams/sheikhs, educators and academics in the field of Islamic studies, perceive and use online platforms to convey their religious knowledge. The findings suggest Muslims value the benefits of accessing knowledge, communicating ideas and facilitating religious pluralism via digital platforms. By the same token, participants warned against the dangers of information anarchy, “Sheikh Google” and the limitations of “do it yourself Islam”. Importantly, the article shows imams, educators and Muslim scholars largely prioritise face-to-face learning as a more reliable and effective method of teaching and establishing rapport among Muslims compared to eclectic internet-based information dissemination. At the same time, religious actors are not averse to Muslims using digital platforms so long as they possess the skills to cross-examine online content and verify the credentials of religious actors. For more complex and circumstantial issues, participants encouraged Muslims to consult a local imam or trusted religious scholar from the community.

1. Introduction

Since time immemorial, religions, including Islam, have embraced, adapted and resisted various technologies, dating back to the use of parchment, printing, and more recently, digital communications (El Shamsy 2020; Deibert 1997; Robinson 1993). For most of Islamic history, religious scholars (ulama) generated their influence through the oral and written transmission of Islam’s sacred texts and Prophetic traditions (Berkey 2014; Brown 2014; Zaman 2001). Within the domain of ulama, religious expression was conveyed in speech, writing, rhetoric, ritualistic performance and non-discursive cues (Mouline 2014; Jones 2012). To this day, these forms of religious expression and scholarly transmission of knowledge are facilitated in mosques, prayer halls, madrasas, libraries, universities and Sufi lodges with the aid of books, manuscripts, electronic media and other literary, aesthetic and cultural devices (Bunt 2018; Brinton 2016; Moosa 2015; Hefner and Zaman 2010). Although Muslims have been privy to new technologies over the centuries, the volume, speed and accessibility of digital technologies has significantly altered the way religious knowledge is communicated and exchanged between Muslim audiences and religious actors vying to speak for Islam.

At the heart of the debate about digital technologies is whether Muslim religious authority is experiencing a rejuvenation of pluralism or a liquidation of its traditional structures of authority. Within the academic and intellectual landscape, the increased accessibility of new platforms is usually viewed in two distinct ways: as a benefit for the democratisation of knowledge, or conversely, as the “fragmentation of religious authority” (Robinson 2009; Eickelman and Piscatori 1996). Other scholars, meanwhile, refrain from the term “fragmentation” as Islam never exhibited a single united religious authority, but a “proliferation” of ideas (Krämer and Schmidtke 2014, p. 12). Regardless of the terminology employed, the common denominator binding these arguments points to the rapid and unprecedented level at which ideas and interpretations of Islam are readily available and contested in what Dale Eickelman and Jon Anderson have labelled the “new public sphere” (Eickelman and Anderson 2003, p. 16).

Within this emerging public sphere, Islam is expressed in countless online platforms from scanned copies of sacred texts to fatwa websites, live forums, online blogs, personal websites of sheikhs, marriage celebrants, library repositories, podcasts, YouTube, Islamic television networks and social media. Gary Bunt (2018, p. 7) uses the umbrella term “cyber-Islamic environments” to describe the diversity of Muslim worldviews and identities found on the internet. Bunt claims religious authority is a fundamental driver within cyber-Islamic environments. He points out there is an expectation among Muslims who are digitally literate to access live sermons, podcasts, videos and other source material associated with religious authorities (Bunt 2018, p. 72). Bunt (2018, p. 80) further speaks about the challenge in identifying the authenticity and credibility of religious authorities online.

This paper critically examines the perceptions of Australian Muslim religious actors in the way Islamic religious authority is constructed online. It specifically investigates whether digital and social media is a valid tool in teaching, obtaining and searching for Islamic knowledge. The paper draws on empirical research conducted in Australia between 2018 and 2019 with Muslim religious actors, including imams/sheikhs, institutional leaders, educators and academics in the field of Islamic studies. In doing so, the paper identifies participant views regarding the popularity, efficacy, accessibility and social connectivity of digital platforms. This is contrasted with concerns about information anarchy, an over-reliance on “Sheikh Google”, the rise of pseudo-clerics and dangers of fatwa shopping. Overall, imams, educators and academics encouraged self-regulatory practices when identifying credible online authorities, such as verifying educational credentials of scholars, cross-examining content and deferring “offline” to local religious scholars/experts on personal and context-specific issues.

2. Islamic Religious Authority

Islam does not inherit a central religious institution, nor do Muslim clerics hold any binding authority or exclusive rights to interpreting Islamic scripture (Ali 2020, p. 102; Afsaruddin 2015, p. 15). Rather, there are multiple religious actors, institutions and scholars who lay claims to religious authority based on their ability to transmit, interpret and embody Islamic knowledge. Such a decentralised structure fosters plurality and competition among those claiming religious authority within a particular Muslim community. The most dominant religious entity in the formative and classical periods of Islam was the ulama and its institutions. During this period, the ulama’s authority was largely a non-state, scholarly and civic enterprise. The ulama relied on various archetypes of authority ranging from epistemic, juristic, genealogical, charismatic and pietistic characteristics to guide Muslims on matters of Islamic doctrine and practice (El Fadl 2014; Hallaq 2009; Takim 2006).

Prior to the printing press in the nineteenth century, the ulama were among the very few who had “exclusive access to religious literature” giving them a monopoly over religious knowledge (El-Nawawy and Khamis 2009, pp. 41–42). The ulama’s role as guardians and interpreters of Islam’s sacred tradition was almost unrivalled, particularly on matters of theology, Qur’anic exegesis, Islamic jurisprudence, hadith (Prophetic traditions) and Sufism (tasawwuf). This is partly because many of these knowledge fields were developed in accordance with the ulama’s epistemology and methodologies for interpreting Islam (Kuru 2019, pp. 7, 232–33). As a result, the ulama possessed a “de facto hegemony on religious debate” in Islam (Roy 2004, p. 158). The ulama’s influence, moreover, was not limited to teaching Islam, as many of them served as civil servants, diplomats, caretakers of mosques, orphanages and managed religious endowments (Mouline 2014, p. 2; Saeed 2006, p. 11).

However, towards the nineteenth century the onset of colonialism, authoritarianism, state-centric reforms, ulama–state alliances, increased literacy rates and technological advances in the Muslim world dramatically shifted the contours of Islamic religious authority, both epistemologically and politically. As the ulama’s moral authority and monopoly over religious knowledge diminished, a new wave of religious actors surfaced, including lay interpreters, Islamists, state officials, scholar-activists, da’wa (missionary) preachers, cyber imams, televangelists and online bloggers vying to speak for Islam. Within this hyper-pluralised context, the question of who speaks for Islam is no longer attributed to the ulama, but something shared by all Muslims who have access to the founding texts and other forms of knowledge through the increasing accessibility of mass media and information technology (Mandaville 2007, p. 102; Volpi and Turner 2007; Eickelman and Piscatori 1996, p. 131).

3. Hyper-Pluralism in a Digital Age

Various works specify the increasing communication and multiplicity of voices emerging in the digital Muslim sphere. This includes research on the digital contestation of Islam and religious authority, cyber clerics, the online–offline nexus, digitisation of Muslim religiosity, the use of social media among diaspora Muslims and creation of virtual communities (Rozehnal 2019; Bunt 2018; Kayıkcı and d’Haenens 2017; Larsson 2016; Possamai and Turner 2014). Jon Anderson (2003, p. 48) describes the internet as creating a public space that allows a new class of interpreters to reframe Islamic authority and expression in their own terms. He asserts, “In this move, relatively greater anonymity conveys an aura of more social—or at least more common—authority than that of face-to-face transmission between master and pupil, pir and murid, mulla and congregant” (Anderson 2003, p. 48). While cognisant of the fragmentation of religious authority, Eickelman and Anderson (2003, pp. 15–16) view the proliferation of actors, swift knowledge exchange and high levels of pluralism shared in the public space as a positive development for civil society.

Peter Mandaville (2003, p. 146) similarly refers to how online members can share the same communal resolve as part of an “imagined community”. Mandaville (2003, p. 146) refers to the use of the internet as part of a “new embodiment of the global umma”. This prompts questions as to whether sacred rituals and religious practices can be embodied online, bringing the “imagined” to the “real”. Such observations are important to consider in wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. With the closure of mosques and religious institutions, the month of Ramadan saw an increase in internet usage to upload daily podcasts, videos and Friday sermons to ensure Muslims remained informed and connected with their community (Mansoor 2020; Ibrahim 2020b). Even the world’s most sacred mosques in Mecca, Medina and Al-Aqsa closed for Friday prayers with some prayers being livestreamed (Ibrahim 2020a). The livestreaming of Friday (jumma) prayers sparked intense debate among Muslims, with most Islamic legal authorities prohibiting virtual prayers in their fatwas.1

A further area of contention has been the mass proliferation of online fatwas (non-binding religious edicts). The process of searching for Islamic rulings online has been labelled as “fatwa shopping” or “inter-madhab surfing” (Yilmaz 2005, p. 198). Ihsan Yilmaz describes the pragmatism behind the ability of Muslims to use their own self-agency in selecting fatwas to resolve minor issues.2 Yilmaz (2005, pp. 198–99) correspondingly notes that it opens the door for individuals to handpick fatwas at their own peril. The problem becomes twofold when fatwas are removed from their cultural, customary and legal contexts and applied to new environments without the same societal values, or when dubious fatwas from unknown sources are arbitrarily endorsed by individuals.

Fatwa-making is traditionally reserved for highly trained jurisconsults in Islamic law.3 Alexandre Caeiro (2014, p. 75) contends that the traditional standards of issuing fatwas has been drained in a new media age where “charisma and fame” has replaced “knowledge and piety” among Muslim audiences. This, he argues, is perpetuated by the absence of a regulating body to control the quality and authenticity of fatwas on the television and internet (Caeiro 2014, p. 75). Caeiro, nevertheless, claims the chaos attributed to fatwas fails to do justice to the “remarkable restraint” Muslims have demonstrated in the face of new technologies. He maintains that Muslims still defer their religious questions to recognised scholars. In this respect, Caeiro (2014, p. 75) credits the ulama for being able to address contradictory fatwas as part of a long-existing pluralistic tradition.4

However, while contradictory fatwas and interpretations existed in the past, Muslims did not have as much access to the large quantity of fatwas available today. The spread of online media, as Caeiro maintains, made these contradictory fatwas more visible, increasing “confusion and uncertainty” among the Muslim masses. The domain of fatwas, therefore, represents a microcosm of the much larger debate about the hyper-pluralisation of Islamic authority, especially in environments where individualism, self-discernment and progressive ideas of ijtihad (independent reasoning) are firmly taking root.

The notion of an enlarged Islamic digital sphere reveals the tension between old and new ways of conferring religious authority. It opens new pathways for religious actors and Muslim audiences to facilitate, debate and assert their ideas in virtual spaces. With this comes increasing diversity, competition and pedagogical shifts in learning and consuming knowledge. More significantly, the framing of an Islamic public sphere prompts questions relating to the Muslim “private sphere”. With access to multiple platforms and voices, it is important to explore how Muslims internalise and self-discern who they trust and seek for religious knowledge. By the same token, it is important to consider how religious actors shape and tailor their methods of teaching and preaching to new online audiences.

4. Methodology

This paper collates data from fieldwork conducted between 2018 and 2019 among Muslim religious authorities in Australia. It includes 40 in-depth interviews with imams/sheikhs, chaplains, academics and educators from Australia’s major mosques, peak Islamic bodies and universities teaching Islamic studies. In total, 25 clerics and 15 academics/educators were recruited for interviews. The high ratio of Muslim clerics interviewed compared to Muslim academics and educators is indicative of the high number of clerics in Australia.5 This correlates with the widespread involvement of imams in mosques, Islamic schools, chaplaincy services, aid organisations, youth groups, halal certification boards and peak body organisations, such as the Australian National Imams Council (ANIC) and Australian Federation of Islamic Councils (AFIC).

Most imams and sheikhs interviewed were employed inside Australian mosques and held overseas university degrees in Islamic studies or traditional ijazas (licences) from recognised Islamic scholars.6 Academics and educators constitute another group of scholars and intellectuals who are not generally considered ulama. In Australia, most Muslim academics and educators do not lead congregations or provide religious counsel in their roles as university lecturers and teachers of religion in secular and religious institutions. However, several community educators and academics in this study have previously served as imams in mosques and undertaken traditional Islamic studies prior to their university education. Nevertheless, most academics are typically considered as fulfilling a secular profession, not a religious one.

Muslim academics and educators interviewed came from diverse cultural backgrounds with qualifications in the field of Islamic studies from Australian and overseas educational institutions. 18 different ethnicities were represented in the sample of imams, educators and academics, along with 14 mosques and several Australian universities. All 25 clerics interviewed were male. To compensate for the lack of female clerics in the sample, a higher ratio of female academics and educators was sampled. Out of the 15 academics sampled, 10 (66.7%) were female. Altogether, the sample represented Muslims from major and minority ethnic groups, Sunni, Shi’a, Sufi, Ahmadiyya, men, women, intergenerational Muslims and converts.

In addition to interviews, 300 Muslim participants were surveyed from different backgrounds and localities across Australia. Survey participants came from 40 different ethnicities with a larger representation of female participants (58%) compared to men (42%). The survey was open to Muslims from all religious persuasions. Overall, 81% of respondents identified as Sunni Muslims, 10% identified as Shi’a, 7% as non-denominational Muslims and 2% as “other”. A small portion of participants identified as Ahmadiyya, Alawite and Sufi in the other category. The survey was disseminated to different locations, Muslim associations and ethnic groups to maximise the probability of obtaining a representative sample. This was part of a snowballing technique, which involved sampling a small group relevant to the research questions who would pass the survey to other interested parties, creating a flow-on effect (Bryman 2015, p. 424).

As part of the study, interview participants were asked about the impact of online platforms in obtaining and conveying religious knowledge. Participants were asked whether social media was a good tool for conveying Islamic knowledge, and whether they perceived Muslims were using the internet for gaining Islamic knowledge instead of consulting ulama or field experts in Islamic studies. Survey questions, on the other hand, focused on various themes relating to Muslims and religious authority, including the different religious actors and platforms Muslims consulted for religious knowledge.

All participants have been de-identified. Popular Muslim names have been used as pseudonyms to protect their identity. Where appropriate, I describe their ethnic background, location and religious affiliation to capture the sample diversity.

5. Identifying Muslim Religious Actors

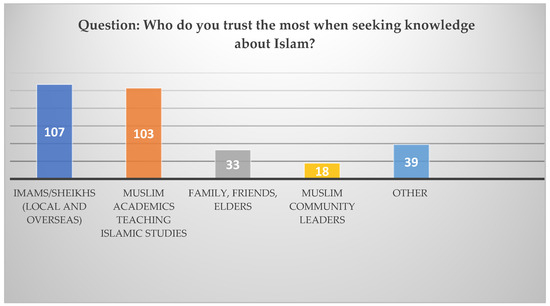

This study uses Weberian understandings of authority to ascertain who Muslims trust and go to for religious knowledge. For Weber (1978, pp. 126–27), legitimate authority is based on ideas of trust, non-violence and social recognition. Bryan Turner (2007, p. 119) similarly claims a religious leader in Islam gains legitimacy because of popular recognition and support in what he calls “a local, discursive and popular form of authority”. Among the survey questions, participants were asked who they trust most in seeking Islamic knowledge. Survey participants were provided six options: (1) local imams/sheikhs; (2) overseas imams/sheikhs; (3) Muslim academics in the field of Islamic studies; (4) Muslim community leaders; (5) families, friends and elders; and (6) other. The “other” category allowed respondents to enter actors not mentioned in the survey options. See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Muslim actors and Islamic knowledge.

Imams and sheikhs constituted the most trusted actors among survey respondents, nominated by 35.6% of participants (19.3% preferred local-based imams, while 16.3% went to overseas-based clerics). This was followed closely by 34.3% of participants who selected academics. Together, imams and academics constituted 70% of participant responses, showing direct correlation between scholarly knowledge and authority. The remaining respondents approached actors including family/friends/elders (11%), Muslim community leaders (6%) and others (13%). The findings indicate survey participants had greater trust in people specifically trained and involved in Islamic studies as opposed to leaders from different professions in business, politics and government. Survey respondents who selected the “other” category identified Islam’s sacred texts, local and overseas sheikhs and specific scholars as their sources of trust.

6. Platforms Used to Obtain Islamic Knowledge

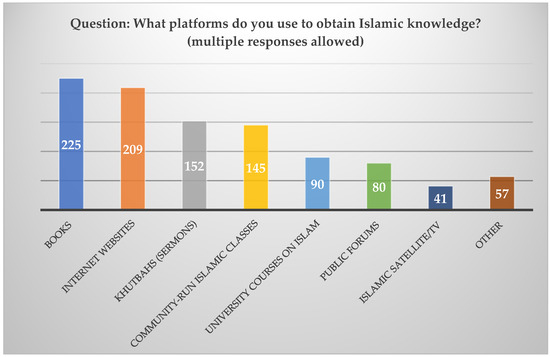

Survey and interview participants identified the internet and other digital devices as an important communication and marketing tool. According to survey results of 300 Muslims, the most sought-after platforms were books (22.5%), websites (21%), sermons (15%) and community-run Islamic classes (14.5%). Under “other”, participants cited podcasts, YouTube, social media, Qur’anic study circles, local imams and institutions, family, friends and Islamic retreats (rihlaat) (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2.

Platforms used to obtain Islamic knowledge.

A total of 999 survey entries were made. On average, each respondent accessed three platforms, highlighting that Muslims are not one-dimensional in their knowledge search. This could be due to natural curiosity to explore new ways of obtaining information, the ability to cross-examine sources, easy access and affordability. Incidentally, many of these platforms overlap with each other. For example, sacred texts and scholarly books are available online, along with fatwas, sermons, live forums, conferences and university classes on Islam.

The internet’s popularity was almost undisputed among participants. Sheikh Ali, an Iraqi-born freelance Shi’a cleric, was among the many clerics who used digital platforms and social media to engage with their congregations. When asked what platforms he used to convey Islam, he replied: “I have online lessons, I have my participation in different gatherings, I have my social media involvement, I have my YouTube channel, I have my books and writings, I have my website”. Although Ali preferred the mosque as the main headquarters to teach Islam, he recognised the importance of engaging in different platforms to increase his reach and influence.

Like Ali, Sheikh Abdul, who is an Australian-born imam, emphasised the importance of engaging with multiple platforms to reach out to younger generations of Muslims, particularly those detached from the mosque:

For those who are born and raised here, you need more platforms for you to engage with them than those who come from overseas because those who come from overseas are used to the concept of the mosque, and the mosque is the place that you go to for Islamic help or Islamic assistance or uplifting. The second and third generation, those that are born and raised here, you need more platforms for you to engage with them. Social media is another platform these days.

Abdul explained that Muslims raised in Australia inherit different ideas about the mosque compared to overseas Muslims. In his opinion, overseas Muslims were more accepting of the mosque as a place to gain religious guidance and assistance, whereas younger and first-generation Muslims needed alternative platforms like social media to be engaged.

Imam Tahir, who is a younger Pakistani-born imam in his late 20s, commented on the convenience and practicability of the internet. When asked if Muslims were consulting the internet for religious knowledge, he responded: “They are using internet a lot because it’s all open, whenever you need to look for something you just Google it. But that’s why it’s also causing a bit more confusion and wrong things are going around as well…” Tahir’s comments echo Caeiro’s criticisms about the confusion and anarchy surrounding the mass proliferation of information. As Tahir alluded to, many Muslims do not have time to carefully examine religious content, leading to subjective and personal biases in determining between what is right and wrong.

Other imams viewed the internet as an effective tool to engage with Muslim congregations. Sheikh Elias, a Sydney-based freelance cleric, reflected on the importance of engaging with social media to increase visibility and networking with the Muslim community. He spoke positively about his experiences:

I’ve worked with a few different media companies and we did a video, and it went viral, like more than a million views…You’ve got to be on social media and yes, whatever we can…all the classes and things we did it all streamed or whatever it is, live on social media. It’s a huge platform.

Despite mentioning its benefits in spreading Islamic content, Elias was critical of Muslims going to the internet blindly. He argued trying to find knowledge on the internet was an issue for people, especially those “without the requisite background” or “foundation in Islamic law or Islamic training or education”.

Various academics and educators shared similar views about the internet’s widespread use and popularity. Amina, a Melbourne-based academic in the field of Islamic studies, explained that online courses and search engines like Google were becoming “more and more dominant”. Likewise, Musa, a community educator, reflected on the easy accessibility of the internet, particularly for younger generations:

I think the younger generation are, it’s a lot easier for them to do that in terms of access so they will do a search on a particular topic, and the danger with that is if they have not been trained or educated in how to assess the quality of information that they find on the internet then they might just take anything that they find without being able to assess the veracity, or the quality, of the source of information that they’re accessing.

Musa reflected on the dangers of not knowing how to assess the quality of information. He drove home the point about digital and religious literacy, and the importance of cross-examining information. Correspondingly, Amina encouraged her students to discern between websites and peer-reviewed journals. She said most university students were “academically diligent” in the sources they used. Amina maintained that university students could “discern between what they should be looking at and what they shouldn’t, but the wider community, they’ll just read anything”.

Karim, who is a lecturer in Islamic studies, spoke optimistically about using social media as a marketing and communication tool. When asked if social media was a good tool to disseminate religious knowledge, he replied:

Yes of course, social media is great in firstly getting a public profile and also you can make videos, you can have short tweets that have lessons in them, so I definitely think that social media can be great and especially with YouTube and other podcasts. People have a lot of listening time because of their smartphones. It actually, in my view it is essential to get into that field.

Apart from networking and building public profiles, academics use Twitter to share videos, lectures, articles, op-eds and threads to illustrate a point or engage in public debate. Many Muslim academics use Twitter as a springboard to market their scholarly and personal works to wider audiences. In Australia, there are fewer imams active on Twitter compared to academics. However, globally there are many high-profile imams and preachers with significant followings surpassing the millions.7

Karim added that there were many perks of using the internet, such as its convenience, accessibility and ability to connect globally:

Internet just gives access to so many people, especially the ones that are not in Australia. It’s so convenient. You can listen to a nice 20 min talk while you’re on your train going to work. It just makes it so convenient for the listeners. However, I think people still contact the local imam, sheikh or scholar if they have very specific questions to ask or they need help and guidance at a personal level.

Karim’s comments are true for Muslims living in urban communities with busy lifestyles and families who do not get the time to engage in lectures, courses or visit imams. Karim, like most of the participants, advised Muslims to contact a local scholar or imam if there are specific questions they need addressed.

The rise of online platforms has also resulted in the expansion and democratisation of religious knowledge. Sara, a Melbourne-based academic in Islamic studies, explained that “the diversity of platforms in Australia was an asset”. Others argued that Islam should be “kept open and accessible” and warned against any groups or institutions trying to monopolise religious knowledge. In this context, the digital environment allows Muslims to preserve their autonomy and access platforms they find appropriate and beneficial.

At the same time, imams alluded to the erasure of traditional methods of learning Islam via scholarly traditions and teacher–student transmission. Imam Idris, for example, noted that the ulama had almost become dispensable in the internet age: “…before, the sheikhs, their power was holding the knowledge. Now the knowledge is on the internet so you don’t really need the ulama a lot of the time because you can go and research yourself”. Idris’s observations are noteworthy as they touch on the ulama’s demise as the sole gatekeepers of religious knowledge and the rise of self-guided approaches to Islam.

7. Social Media

Imams and academics were less sceptical about using social media as a platform to convey information about Islam. Several imams expressed the necessity and practicability of using social media to spread the message of Islam. This was also met with caution and warning about the limitations of online media. In speaking about the internet’s ubiquity, Imam Sadiq, who leads his congregation in Brisbane, replied:

Social media is used all around the place; it’s used all around the world. Everybody is on WhatsApp, and Facebook…I believe it is a good tool, but it is not sufficient as a standalone tool. You have to go somewhere and actually sit with them because it’s not face-to-face; you don’t know who you’re talking to online.

Other imams insisted that social media was used more as a practical necessity in modern-day contexts. Imam Irfan, a Pakistani-born imam from Sydney, agreed social media has its benefits: “Like as an imam for example, we can spread the message to the people straightaway…For example, making the decision for the Eid or Ramadan”. Imam Yasir, a Lebanese-born imam from Sydney, concurred that, “we need to use this means in order to deliver the right picture of Islam”. Meanwhile, Imam Usman, an Indonesian imam in his 60s, stressed the need for imams to be adaptable and use social media: “We live now in modern times; we have to be conversant, familiar and have sufficient knowledge about these tools…we as imams need to be smart in spreading Islam”.

Imam Yusuf, an elderly imam from Melbourne, mentioned he was apprehensive about the role of social media. He said there was a lot of “rubbish” on Facebook, and he was not part of any social media platform. Despite his reluctance to engage in social media, Yusuf conceded people with expertise in social media could harness it to benefit the Muslim community. He felt it could be particularly useful for messaging and promoting events. Upon reflection, Yusuf mentioned how he missed out on attending a public event from a popular visiting imam from overseas. He said the visit was advertised all over social media, but as he had no account or engagement on social media, he was completely unaware of the visit.

Sheikh Abdul, a senior member of ANIC, argued that imams needed training in social media: “…not all imams have the touch of the social media, so that can be one of the things that we can train up the imams in”. At the same time, Abdul qualified, “A lot of people are just going online seeking the Islamic guidance from online which is a concern to us”. In response, he has given lectures to his followers about the dangers of seeking Islamic help and guidance online as a way of increasing digital literacy in the community.

Muslim academics and educators provided similar responses. Ayesha, who is an educator in Islamic studies, spoke about the efficacy of social media. She argued that in a normal lecture, students stay “10 min to listen to your lecture, but they can stay 10 h on Facebook and WhatsApp”. When asked about the internet more generally, she replied it was having a negative impact on Muslims because of the inability to verify the source of information and make accurate and informed judgments. Ayesha argued passionately about the dangers of the internet and equated it to self-diagnosing an illness and prescribing medicine to oneself without consultation from a doctor. She added that people were dealing with their “spirit”, “knowledge” and “intellect”, which is “very complicated” and deserves the right attention and respect.

Amina also spoke about the impact social media is having in getting research out to the community. She claimed using social media is more effective than getting your article cited by journal articles: “So, that impact is measured by how you’re changing the community or how it’s affecting policies or people, whereas before impact was about how many times you get cited in a journal”. While Amina did not downplay the importance of academic publishing and citations, she said the internet and social media made Islam more accessible to Muslims who do not have the time to attend courses at university.

8. Religious Actors, Social Media and Muslim Youth

Numerous references were made about social media and its relationship with the Muslim youth. Imam Hakim, an Egyptian-born cleric based in Melbourne, spoke about the importance of social connectedness with the community:

So, social media is making things easier for the people. I did not have close relationships with many young Muslims and I found them asking me questions on Facebook and it says, ‘I’m even shy to come to ask you, that’s why I sent you that message on Facebook.’

Hakim shed light on the difficulties faced by Muslim youth in engaging with imams or older mentors in the community. Despite his preference to use social media, Hakim was not oblivious to the dangers Muslim youth faced by going on the internet. He mentioned there are people in the world who try to brainwash the minds of youth and put the “poisons of extremism in their minds”. Hakim stressed the importance of encouraging Muslim youth to cross-examine information with other sources, such as imams, books and texts:

…I’ll always say this is from the European Council of Fatwa; this is from the Assembly of Muslim Jurists in America. So, I refer to the resource or the information, this is from that book, this is from that book, so they can go and read to make sure because many people say this imam said that fatwa and you go and check in the book, [and] the book is not there.

Like Hakim, Imam Zakir, who leads an Albanian mosque, urged the youth to be more discerning in choosing who to listen to online. He warned young Muslims about the dangers of finding fake imams and impersonators on the internet.

Despite constant warnings about fake imams, most self-styled preachers have become well-versed in mimicking non-discursive cues and using emotion to lure young Muslims into thinking they are legitimate scholars. In writing about “travelling” and “self-made” imams in the Netherlands, Daan Beekers (2015, p. 202) notes the successful transmission of knowledge does not always depend on the message’s contents, but the “persuasive and performative capacities of speakers”. In the context of radicalism, Imam Sadiq agreed that younger Muslims are more prone to falling for charismatic and dynamic preachers online:

Most of the youngsters that have become radical, they become radical because they are onto this highway without investigating, without consulting with a local scholar, they started listening to a person that may be dynamic but he’s words are venomous, and his message is venomous.

Sadiq touched on the dynamism of online preachers and “internet sheikhs” who preached conservative, simplistic and ideological interpretations of Islam. This was a major concern shared among imams and Muslim leaders during the height of ISIS’s online propaganda campaign to recruit young Australian Muslims (Klausen 2015; Harris-Hogan and Zammit 2014). The message to consult local imams was part of a large-scale effort to reconnect with Muslim youth and better understand their experiences. The same message can equally be applied to other online forms of radicalisation found in far right and white ethno-nationalist groups.

9. Confusion, Anarchy and Digital Literacy

Positive attitudes towards the internet were counterbalanced with arguments about the risks of gaining knowledge from the internet. Imam Irfan expressed that Muslims should go to ulama for “real knowledge” rather than relying on the internet. He explained, on the internet, people get confused between right and wrong. He asked: “What will happen? You’ll get confused. You can get heaps of opinions, [but] how are you going to say that this one is correct…if you trust any alim [scholar], go to him and get his opinion and follow”. Imam Usman used the analogy of a coin to describe how the internet had two sides—one that could be beneficial and one that could be dangerous depending on a Muslim’s foundational knowledge of Islam.

Searching for information online was a concern for most imams. Imam Idris, who is a Muslim chaplain in Sydney, correlated the rise of digital platforms with the lack of certainty around knowledge and truth claims. For him, the World Wide Web lacked the veracity and authenticity of traditional scholarship:

Everything is now online and whatever’s online is the truth basically…Everyone’s out there putting a voice but who qualifies the voices? So that’s the problem with social media. It will never replace traditional scholarship in my opinion, but it can be there just more like a fluff you know, a bit of reminders, but I wouldn’t be taking too much from it.

Idris favoured receiving religious instruction and mentorship from a recognised sheikh. He, like many imams, emphasised the importance of being guided through the ijaza-isnad (licence-transmission) tradition, where students receive licences from recognised scholars to transmit texts or Prophetic sayings.

The same sentiments were shared by Sami, a sociologist of Islam, who mentioned the phenomenon of fatwa shopping:

You punch a couple of buttons and you find a sheikh who is ready to give a fatwa and there you go, you don’t even have to move your butt to move around and you even, you can even do sheikh shopping on the internet.

The unregulated nature of fatwas in the public domain was a serious concern to participants. The confusion and indecision about following the “right fatwa” can be particularly hard for Muslims without any religious guidance or supervision. The issue becomes even more dangerous when an individual chooses verdicts aligned with their political and ideological interests.

The implications of who is granted authority were raised among imams. When speaking about the cyberworld and Islam, Sheikh Ali responded that “everyone now is assuming authority” after having read a few books or videos online. He recounted, “And that’s why we always jokingly say Ayatollah Google answers all of your questions”. By the same token, Ali argued that people are becoming increasingly skilled in learning “the etiquette of internet usage”. He suggested, in its first manifestation, the internet overwhelmed people with the amount of information it had to offer, but now, he argues “…people are able to find the balance where they would like to verify what kind of person this is, what qualification they have, whether they are an authority or not, whether the information is authentic or not, and things like that”. Ali provided a unique perspective of the critical thinking and verification methods behind explorations of religious authority online.

Academics and educators also expressed the challenges of identifying religious authorities. Nadia, a Sydney lecturer in Islamic studies, argued that many Muslims were deferring to “Sheikh Google” for knowledge instead of experts and scholars:

Unfortunately, we do have that problem of authority in some sense that ‘Sheikh Google’ becomes really easily accessible to the youth who don’t know how to manoeuvre through all this information that the [World] Wide Web can have…I think people are also conscious of this radicalism of the information they get about Islam. So, some people are seeking more authentic places to seek Islamic knowledge but like I said, the common young person growing up, it’s at the tip of their fingers.

As was the case with imams, Nadia raised the issue of being able to navigate the internet. She suggested that systems could be put in place in cybersecurity to caution people against incorrect information. Most academics and imams, however, did not expand on policing or government-based regulations and focused on increasing religious literacy, self-discernment and mentorship to identify credible websites and religious actors.

When it came to how Muslims should navigate the online world, several imams agreed that Muslims need to “know the source”. Despite this advice, Imam Yasir maintained: “This is not enough—[you] need to have connections with mosque in order to deal with personal issues”. Yasir explained the internet causes confusion and provides conflicting information about Islamic issues. Imam Omar, an Afghan imam in Melbourne, also recommended Muslims go directly to an imam for guidance: “But first come to the imam, but choose an imam whom you trust: you study his background, experience him, listen to him many times. When you trust him completely then ask him; he will guide you properly”. Omar mentioned trust is formed through dialogue and conversation. He added, from communication, one can see how an imam tries to resolve an issue, how the imam listens to a person and what sources the imam refers to and the context he is talking about.

10. Face-to-Face Versus Online Learning

Much of the ulama’s authority and appeal relies on their ability to mentor adherents under a teacher–student model centred on what Ebrahim Moosa (2015, p. 58) calls “heart-to-heart transmission”. The ulama cultivated a distinctive pedagogy for transmitting knowledge through a chain of living teachers and scholars linking themselves back to the Prophet. Moosa (2015, p. 58) adds the value of face-to-face learning fulfils the function of grounding knowledge in a “network of authority, authenticity, and sanctity”. American-based jurist, Mohammad Fadel (2016, p. 475), similarly refers to this process as “acculturation (tarbiya)” within the Islamic tradition. He argues that the mastery of religious values emerges through the living embodiment of Islamic values as taught by well-trained religious instructors.

Several imams reiterated the value of face-to-face interaction. Despite using digital technologies to engage with his congregation, Sheikh Ali described the mosque as the “headquarters” and “hub” for spiritual and religious knowledge. He juxtaposed the mosque’s centrality with other platforms like social media as being “effective and more powerful”. Ali explained that physical interaction brings into play other spiritual and religious aspects of teaching and worship that would otherwise be missed if Muslims learnt Islam online or in isolation. Imam Hamza, a Turkish-born imam, similarly reflected that “…people get benefit from one-on-one relations and learn more than the internet”.

Imam Sadiq argued the internet lacks the ability to assess and understand a person’s moral conduct and level of piety, which is easier done in front of a local person. He warned Muslims about following random people on the internet:

You may listen to a person on the internet that is dynamic but you don’t know what his personal life is and basically we are ordered to find out the characteristics, the spirituality of the person before we listen to him because if it’s holy words, it’s not going to register and it’s not going to be of any use to the person. I strongly speak against listening to random people on the internet; of course, if a person is well known throughout the world that is different, but if a person is not well known, he’s just dynamic. I don’t support that.

The observation of an imam’s adab, or refinement of character, is a well-established principle of the ulama’s pedagogy (Keiko and Adelkhah 2011). Akbar confirmed it is incumbent on a believer to examine the imam’s or preacher’s moral characteristics and spiritual ethic to assess their conduct and reliability. Rather than calling for any restrictions or regulations on the internet, Akbar put the onus on the individual to investigate the credibility of the imams they followed.

Despite its short-term benefits, there was also sharp criticism towards social media as a replacement for in-depth teaching. Jamila, an educator who runs community courses about Islam, explained:

I think unfortunately for young people, social media is their platform, they’re all on their phones and gadgets; however, what is missing is knowledge not information. So, information is conveyed on social media because people only have literally 30 s to get through something but that’s not going to change people’s attitudes…So, social media, it’s good just to create this image branding of a relevant Islam but it’s not a meaningful way.

For Jamila, social media represented a quick fix solution to make Islam relevant. It only succeeded in transmitting information as opposed to meaningful knowledge. Rahim, an academic in Islamic studies, argued along the same lines: “Clearly, one cannot use social media to convey in-depth knowledge of Islam, but one can use social media to convey certain ideas about Islam”. In this instance, imams, academics and educators—despite their different workplaces and functions in society—shared similar sentiments regarding the benefits of in-depth learning as opposed to information seeking.

Michelle Walker’s (2020) recent work is instructive in understanding in-depth and systematised forms of learning. She refers to the ability to think, process and reflect on information as “slow philosophy” or “reflective and transformative thought”. She offers slow philosophy as a solution to the thoughtlessness and haste overshadowing the modern industrial world, where slowness is seen as a liability to progress and efficiency. She contends:

…in a time where internet scrolling, scanning, and skimming dominate much of the intellectual landscape, slow philosophy has its work cut out for it. Slowness sits uneasily in a culture devoted to speed and haste. All the more reason for philosophers to demonstrate the importance of such an education in thinking.(Walker 2020)

Walker’s notion of slow philosophy runs parallel with the attitudes of imams and educators who feel the internet is harming contemplative methods of learning and education. It also unveils the dynamic between the “public space” where information is quickly exchanged and digested, compared to the “private sphere”, which requires the time to think, process and intellectualise information. The private sphere, in a sense, enables Muslims to internalise their doubts, and navigate their beliefs, attitudes and understandings of Islam before deciding where to go next for guidance.

11. Discussion

Despite their different functions in the community, imams and academics described similar experiences with digital and social media. For imams, the digital world provided the opportunity to preach, spread da’wa and promote their charity and religious activities. Meanwhile, academics found platforms such as Twitter useful to convey short messages, lectures and academic content. Although imams preferred traditional pathways of conveying and teaching Islam, they agreed that digital media was a modern-day necessity. Academics and imams also emphasised the importance of digital literacy, with some leading the way with educational initiatives and sermons about identifying the credentials of religious actors, fact-checking online content, seeking accredited and qualified teachers, encouraging face-to-face interaction and watching out for fake imams.

The high volume of material in the digital space was a concern to participants, particularly for vulnerable populations such as youth who are susceptible to exploitation and misinformation. However, hardly any of the participants called for extravagant measures to control or regulate where and from whom Muslims gather their information. Participants, instead, challenged the Muslim public to think critically in using their judgment to see which platforms are reputable, trustworthy and morally viable. In addition, participants encouraged Muslims to refer complex, personal and context-specific questions about Islam to a recognised scholar, local imam or field expert.

Lastly, most participants were clear the internet was not a substitute for face-to-face learning. Imams implicitly distinguished social media as a tool for communication and information as opposed to a systematised method of learning. Instead, imams were able to reassert the credibility and reliability of traditional approaches of learning in juxtaposition to the internet. For them, the internet’s shortcomings helped reinforce the ulama’s age-old formula of “heart to heart” transmission between the scholar and student. This does not mean imams relinquished their ability to engage in alternative methods of communication, so long as it did not replace traditional platforms of obtaining knowledge under the guidance of scholars.

12. Conclusions

Muslim religious actors are gradually adapting new strategies and techniques in using online and social media platforms. Most religious actors in this study used digital platforms as active or passive participants. The impact on religious authority is significant on three main counts. First, it enlarges the Muslim public space to allow different religious actors to engage online about Islam, thus increasing the multiplicity of voices and enriching public debate. Second, it enables religious actors and Muslim audiences to project and share religious content through faster and more effective mediums to reach wider audiences. Lastly, it helps connect various Muslim groups, particularly those who feel alienated or marginalised, who seek religious authorities online.

Conversely, participants expressed concerns about the overreliance on “Sheikh Google”, the dangers of fatwa shopping and rise of pseudo-religious clerics. Participants warned against dynamic preachers online who were not adequately trained or recognised as legitimate scholars. This was met with fears around Muslims navigating Islamic cyber environments unknowingly without guidance. As a result, participants argued that online methods of learning were not as deep, meaningful and authoritative as face-to-face interactions, where matters could be directly clarified, learned and embodied from qualified instructors. For imams, building trust and rapport was much more easily done by sitting with scholars, as opposed to surfing the internet and being overwhelmed with information.

Amid the hyper-pluralism of the Islamic digital space lies a willingness among participants to better understand the dynamics of religious authority. The onus, as illustrated in the article, is on the communities, individuals and religious actors to be transparent in how they assess and identify credible sources. There is emerging consensus about fact-checking information, scrutinising qualifications and exercising careful judgment over who and what kind of information one takes to inform religious practice or worldviews. This requires the diligent self-assessment of individual Muslims who must remain aware and critical of how authority can be misplaced and exploited, or even worse, exercised in a manner that undermines peaceful and pluralistic invocations of Islamic practice. At the same time, Muslim communities can focus collectively on developing methodologies for ranking the authenticity of major websites about Islam, and refining educational programs tailored for Muslims, particularly the youth.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Deakin University (code HAE-18-048 on 6 July 2018 and code 2019-092 on 3 May 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For fatwas allowing virtual Friday prayers see: Islamic Centre of Ireland, (Umar Al-Qadri Fatwa on Permissibility of Online Jumma Prayer 2020). For fatwas against viritual Friday prayers see: (A Statement Regarding the Ruling on Jumma Prayer through Broadcast 2020); (Australian Fatwa Council 2020). |

| 2 | Despite the pragmatism involved in self-selecting fatwas, Yilmaz (2005, pp. 198–99) warns against the increasing growth of micro-mujtahids, especially those who operate outside the boundaries of the established schools of law. He argues that historically traditional Islamic jurisprudence used consensus to stop the avalanche of individual interpretations of Muslim legal scholars. As a consquence, Murad (2004, p. 15) observes that “Instead of the four madhhabs [schools of law] in harmony, we will have a billion madhhabs in bitter slef-righteous conflict”. |

| 3 | The high reverence granted to jurists is enshrined in their ability to exercise ijtihad (independent legal reasoning) and the epistemic primacy associated with applying the shari’a (Zaman 2012, p. 48; Hallaq 1984, p. 3). |

| 4 | Murad (2004, pp. 4–5) asserts how early ulama looked to resolve, understand and negotiate apparently contradicting revealed texts through a range of linguistic, textual, legal and historiographical techniques under the hermeneutical discipline of usul al-fiqh (foundations of Islamic jurisprudence). |

| 5 | There is no official data on the number of imams in Australia. After conducting preliminary internet search in 2018, I found 237 Muslim clerics in Australia compared to 38 Muslim academics in the field of Islamic studies. |

| 6 | Out of the 25 imams interviewed in this research, 23 hold university degrees equivalent to a bachelor’s or master’s, with nine holding PhDs and two with no formal training. Most imams obtained their degrees from overseas universities or madrasas teaching Islamic studies in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Pakistan, Malaysia, Yemen and Iran. Some imams attended master’s and PhD degree programs in Australian universities in the fields of sociology, education and contemporary Islamic studies. |

| 7 | See Twitter accounts for Egyptian televsion preacher Amr Khaled (11.1M), Mufti of Zimbabwe Ismail Menk (8M) and Pakistani Islamic schoalr, Sheikh Tahir-ul-Qadri (2M). |

References

- A Statement Regarding the Ruling on Jumma Prayer through Broadcast. 2020. Assembly of Muslim Jurists of America. March 20. Available online: https://www.amjaonline.org/remote-jumah-prayer (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Anderson, Jon W. 2003. The Internet and Islam’s New Interpreters. In New Media in the Muslim World: The Emerging Public Sphere. Edited by Dale F. Eicklman and Jon W. Anderson. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Afsaruddin, Asma. 2015. Contemporary Issues in Islam. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Jan. 2020. Islam and Muslims in Australia: Settlement, Integration, Shariah, Education and Terrorism. Carlton: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Fatwa Council. 2020. Prayers behind an Imam Online. Australian National Imams Council. April 21. Available online: https://www.anic.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Fatwa-Prayers-behind-an-Imam-Online.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2020).

- Beekers, Daan. 2015. A Moment of Persuasion: Travelling Preachers and Islamic Pedagogy in the Netherlands”. Culture and Religion 16: 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berkey, Jonathan. 2014. The Transmission of Knowledge in Medieval Cairo: A Social History of Islamic Education. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brinton, Jacquelene G. 2016. Preaching Islamic Renewal: Religious Authority and Media in Contemporary Egypt. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Jonathan. 2014. Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet’s Legacy. London: Oneworld Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, Alan. 2015. Social Research Methods, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bunt, Gary. 2018. Hashtag Islam: How Cyber-Islamic Environments Are Transforming Religious Authority. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caeiro, Alexandre. 2014. Ordering Religion, Organizing Politics: The Regulation of the Fatwa in Contemporary Islam. In Ifta and Fatwa in the Muslim World and the West. Edited by Zulfiqar Ali Shah. Washington: The International Institute of Islamic Thought, pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Deibert, Ronald. 1997. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication and World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eickelman, Dale, and James Piscatori. 1996. Muslim Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eickelman, Dale, and Jon Anderson, eds. 2003. Redefining Muslim Publics. In New Media in the Muslim World: The Emerging Public Sphere. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- El Fadl, Khaled Abou. 2014. Speaking in God’s Name: Islamic Law, Authority and Women. London: Oneworld. [Google Scholar]

- El Shamsy, Ahmed. 2020. Rediscovering the Islamic Classics: How Editors and Print Culture Transformed an Intellectual Tradition. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- El-Nawawy, Mohammed, and Sahar Khamis. 2009. Islam Dot Com: Contemporary Islamic Discourses in Cyberspace. Palgrave MacMillan. London: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Fadel, Mohammad. 2016. Islamic Law and Constitution-Making: The Authoritarian Temptation and the Arab Spring. Osgoode Hall Law Journal 53: 472–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Volpi, Frédéric, and Bryan Turner. 2007. Introduction: Making Islamic Authority Matter. Theory, Culture & Society 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallaq, Wael. 1984. Was the Gate of Ijtihad Closed? International Journal of Middle East Studies 16: 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallaq, Wael. 2009. An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Hogan, Shandon, and Andrew Zammit. 2014. The Unseen Terrorist Connection: Exploring Jihadist Links Between Lebanon and Australia. Terrorism and Political Violence 26: 449–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefner, Robert, and Muhammad Qasim Zaman, eds. 2010. Schooling Islam: The Culture and Politics of Modern Muslim Education. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, Arwa. 2020a. Praying in Time of COVID-19: How World’s Largest Mosques Adapted. Al-Jazeera. April 7. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/praying-time-covid-19-world-largest-mosques-adapted-200406112601868.html (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Ibrahim, Arwa. 2020b. Tarawih Amid Coronavirus: Scholars Call for Home Ramadan Prayers. Al-Jazeera. April 22. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/04/tarawih-coronavirus-scholars-call-home-ramadan-prayers-200422110654018.html (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Jones, Linda G. 2012. The Power of Oratory in the Medieval Muslim World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kayıkcı, Merve, and Leen d’Haenens, eds. 2017. European Muslims and New Media. Leuven: Leuven University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keiko, Sakurai, and Fariba Adelkhah, eds. 2011. The Economy of the Madrasa: Islam and Education Today. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Klausen, Jytte. 2015. Tweeting the Jihad: Social Media Networks of Western Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 38: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, Gudrun, and Sabine Schmidtke. 2014. Speaking for Islam: Religious Authorities in Muslim Societies. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kuru, Ahmet. 2019. Islam, Authoritarianism, and Underdevelopment: A Global and Historical Comparison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, Göran. 2016. Muslims and the New Media: Historical and Contemporary Debates. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mandaville, Peter. 2003. Communication and Diasporic Islam: A Virtual Ummah? In The Media of Diaspora. Edited by Karim Haiderali Karim. London: Routledge, pp. 135–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mandaville, Peter. 2007. Globalization and the Politics of Religious Knowledge: Pluralizing Authority in the Muslim World. Theory, Culture & Society 24: 101–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, Sanya. 2020. Muslims amid Coronavirus Lockdowns. Time Magazine. April 23. Available online: https://time.com/5825166/ramadan-coronavirus/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Moosa, Ebrahim. 2015. What Is a Madrasa? Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mouline, Nabil. 2014. The Clerics of Islam: Religious Authority and Political Power in Saudi Arabia. Translated by Ethan Rundell. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murad, Abdal Hakim. 2004. Understanding the Four Madhhabs. Cambridge: Muslim Academic Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Possamai, Adam, and Bryan Turner. 2014. Authority and Liquid Religion in Cyber-Space: The New Territories of Religious Communication. International Social Science Journal 63: 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Francis. 1993. Technology and Religious Change: Islam and the Impact of Print. Modern Asian Studies 27: 229–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Francis. 2009. Crisis of Authority: Crisis of Islam? Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 19: 339–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Olivier. 2004. Globalized Islam: The Search for a New Ummah. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rozehnal, Robert. 2019. Cyber Sufis: Virtual Expressions of the American Muslim Experience. London: Oneworld Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, Abdullah. 2006. Islamic Thought: An Introduction. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Takim, Liyakat. 2006. The Heirs of the Prophet: Charisma and Religious Authority in Shi’ite Islam. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Bryan. 2007. Religious Authority and the New Media. Theory, Culture & Society 24: 117–34. [Google Scholar]

- Umar Al-Qadri Fatwa on Permissibility of Online Jumma Prayer. 2020. Islamic Centre of Ireland. April 12. Available online: http://www.islamiccentre.ie/wp-content/uploads/Fatwa-on-Permissibility-of-Online-Jumuah-Taraweeh-during-Covid19-Islamic-Centre-of-Ireland-2.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Walker, Michelle Boulous. 2020. Why Slow Philosophy Is the Antidote to Fast Politics. ABC Religion and Ethics. June 9. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/religion/michelle-boulous-walker-slow-philosophy-in-a-time-of-fast-polit/12336408 (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Weber, Max. 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. Berkeley: University of California Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Ihsan. 2005. Inter-Madhhab Surfing, Neo-Ijtihad, and Faith-Based Movement Leaders. In The Islamic School of Law: Evolution, Devolution and Progress. Edited by Peri Bearman, Rudolph Peters and Frank Vogel. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 191–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, Muhammad Qasim. 2001. The Ulama in Contemporary Islam: Custodians of Change. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zaman, Muhammad Qasim. 2012. Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age: Religious Authority and Internal Criticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).