Abstract

I examine Hungary’s Catholic arts industry and its material practices of cultural production: the institutions and professional disciplines through which devotional material objects move as they become embedded in political processes of national construction and contestation. Ethnographic data come from thirty-six months of fieldwork in Hungary and Transylvania, and focuses on three museum and gallery exhibitions of Catholic devotional objects. Building on critiques of subjectivity- and embodiment-focused research, I highlight how the institutional legacies of state socialism in Hungary and Romania inform a national politics of Catholic materiality. Hungarian cultural institutions and intellectuals have been drawn to work with Catholic art because Catholic material culture sustains a meaningful presence across multiple scales of political contestation at the local, regional, and state levels. The movement of Catholic ritual objects into the zone of high art and cultural preservation necessitates that these objects be mobilized for use within the political agendas of state-embedded institutions. Yet, this mobilization is not total. Ironies, confusions, and contradictions continue to show up in Transylvanian Hungarians’ historical memory, destabilizing these political uses.

1. Introduction

The growing body of historical and anthropological literature on Catholic devotional art in the years after the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965) has tended to focus on embodiment processes, or how the objects, liquids, images, and spaces through which Catholics engage divine presence constitute their subjective bodily attitudes, orientations, perceptual regimes, and overall sense of self (McDannell 1995; Morgan 1998, 2005, 2012; Orsi 2003, 2005; Young 2008; Van Rompay et al. 2015). Yet, anthropologists who study religion in Eastern Europe’s formerly socialist societies have begun to question the universality of this focus on subjectivity in research on religious materiality. Luehrmann (2011), Wanner (2007, 2012), and Rogers (2011), for instance, have argued that this theoretical orientation reflects the normative assumptions of a parochial tradition of Western European and North American political liberalism—especially the assumption that society should be a collection of autonomous individuals and politics should be the negotiation of personal interests. Following these critics’ calls to look at dimensions of religious materiality beyond its role in subjective formation, in this article, I highlight how the ideological legacies of state socialism inform a national politics of Catholic devotional art. Based on fieldwork in Hungary and Romania, I examine recent traveling exhibitions of Catholic art in Hungarian communities to demonstrate how state institutions at multiple levels are competing to reshape the aesthetic form and content of Hungarian national identity.1

Since 2009, I have been conducting field research in Hungary and Hungarian ethnic minority regions in the Transylvania region of Romania, where more than 1 million ethnic Hungarians live outside Hungary’s current borders. Until 1919, Transylvanian Hungarians held a culturally dominant position in this region that was governed by Hungary as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After World War I, following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Virgin Mary gained great import in Hungarian political discourse. Mary took on enhanced meaning as a culturally unifying and nationally restorative figure, the patroness of a Hungarian community now divided among the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s successor states. During the socialist era, when Romania was governed by an officially atheist regime, Transylvanian Hungarian intellectuals continued to portray the Virgin Mary in museum exhibitions, but focused instead on her role as an element of Hungary’s cultural heritage (Hanebrink 2006; Hann 1990).

In this essay, I examine three Marian-themed museum programs organized by Hungarian and Transylvanian Hungarian intellectuals in the years following the collapse of Eastern Europe’s state-socialist regimes. First, I look at a 2009–2010 traveling exhibit of baroque art, “Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania,” originating in Odorheiu Secuiesc; second, a 2010 exhibit of World War I-era Catholic postcards in Sânmartin; and third, a 2011–2013 traveling exhibition of contemporary art, “Blessed Lady,” originating in Budapest.2 My central claim is that, drawing on the various historical interpretations of the Virgin Mary as national patroness and heritage object, today Hungarian cultural institutions are drawn to collect, exhibit, and interpret Catholic material cultural objects because Catholic material culture is meaningful across multiple fields of political contestation. Marian Catholic art carries meaning in the local, regional, and national scales of political contestation across which museum institutions operate in contemporary Hungarian communities. In the course of substantiating my argument, I thus depart from conventional accounts that describe either individual artworks or collections’ effects on embodiment. Instead, I focus on the goals curators imagined for these exhibitions and both the historical and political contexts that framed these objectives.

Implicit in my approach is an understanding that the categories into which curators place these statues, paintings, and postcards—Catholic ritual objects and legitimate artwork, fine art and mass-produced kitsch—are rooted in institutions and the intellectual practices that they mediate: museums, churches, and local, city, and national government; art history, heritage preservation, cultural administration, and urban design. The sublimation of Catholic ritual objects into the politicized domain of high art and cultural preservation necessitates that these objects be mobilized for use within the political agendas of state-embedded institutions such as museums and art galleries. Yet, this mobilization is not total. Ironies, confusions, and contradictions continue to show up in Transylvanian Hungarians’ historical memory, destabilizing these political uses. I cite a Transylvanian Hungarian historian who struggles to explain why, despite the curators’ claims that “Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania” demonstrates the Church’s role in preserving Hungarian cultural arts against the assimilationist Romanian state, the head of the Church had approved the government plan to demolish one of Târgu Mureș’s Catholic parishes.

I conclude by shedding light on the role that Catholic art plays in constituting cultural policy, which is to say the institutions and intellectual disciplines through which actors shape the production, distribution, and consumption of cultural goods. Through careful consideration of exhibitions of Catholic art in Hungarian communities within and without Hungary’s political borders, we understand not only the Virgin Mary’s polysemic flexibility in contemporary Hungarian culture but also how Catholic arts institutions, together with government-funded museums and research institutes, help constitute and legitimize a particular form of interaction between state institutions and the broader cultural field.

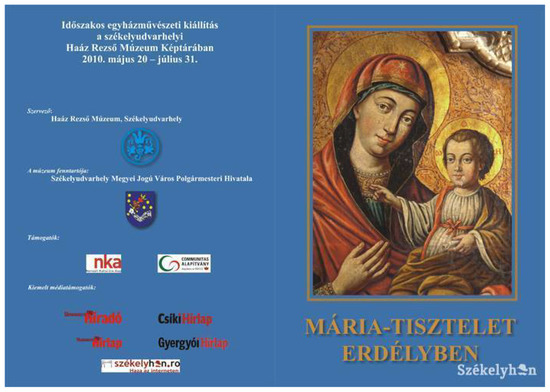

2. From Trash to Transylvanian Art

“Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania” appeared in museums in three cities vying to become centers of contemporary Transylvanian Hungarian cultural life. These exhibitions were curated by ethnologists, art historians, and curators affiliated with the Rezső Haáz Museum in the city of Odorhieu Secuiesc with financial support from the Hungarian state’s Hungarian National Cultural Foundation (Nemzeti Kulturális Alap) and the Communitas Foundation, the official Catholic ecclesiastical charitable organization (Mihály 2010, p. 2) (See Figure 1). It was the museum’s featured show, occupying the entire exhibition space of several large rooms and an entryway. The collection was transferred unchanged to the Catholic Church’s hotel and conference center, the Jakab Antal Study House, near the city of Miercurea Ciuc, before moving with a reduced number of exhibited pieces to an exhibit space in the John the Baptist Parish Church in downtown Târgu Mureş, where I had an opportunity to view the collection in person and interview its curators (Szász 2010).

Figure 1.

Placard Listing the Exhibition Funders.

As the originator of an exhibition that moved to other Transylvanian cities with large Hungarian populations, the Odorheiu Secuiesc-based Rezső Haáz Museum was not only partnering with art institutions in these locales but also advancing its home city’s claim to being a Transylvanian Hungarian cultural and political center (See Figure 2). Odorheiu Secuiesc’s claim took shape within the framework of a competitive rivalry that emerged during a wave of industrialization and urbanization in Romania’s late socialist period. In the 1970s and 80s’, the Romanian socialist government industrialized several Transylvanian cities with significant Hungarian populations, filling new factory jobs with large numbers of Romanian speakers in a move that, according to contemporary Transylvanian Hungarian politicians, served the socialist regime’s goal of national assimilation (Brubaker et al. 2007, p. 134). Odorheiu Secuiesc’s socialist-era political leaders tried but ultimately failed to lobby Community Party leaders to make the town the county seat and invest in its factories (Demeter 2014). This failure isolated Odorheiu Secuiesc from the two fastest-growing economic sectors of the socialist era, heavy industry and government administration. Partly as a result, the city’s population remained uniformly Hungarian throughout the socialist period (Demeter 2014, pp. 78–79). Although Odorheiu Secuiesc’s political leaders consider this to be a mark of pride, using tourism publicity to refer to Odorheiu Secuiesc as Transylvania’s “most Hungarian city” and arguing for its leading role in cultural life before Transylvanian Hungarian cities with mixed populations, it is an unintended consequence of the city leadership’s socialist-era political failures (Gerencsér 2016; Tarján 2020).

Figure 2.

Invitation to Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania Exhibition Opening.

The curators, ethnologists, and art historians who mounted this traveling exhibit also portrayed the Rezső Haáz Museum leading a rebirth of interest in devotional art after a long socialist-era dormancy. The Rezső Haáz Museum, the organizers claimed, was at the forefront of a movement to synthesize Catholic devotional practice with Hungarian national identity. In the publicity for the exhibit, they argued that this synthesis was necessary to correct the ideologically-motivated mistakes of Romania’s post-World War II socialist regime. The socialist government drove the museum’s founder, Rezső Haáz, from public leadership amid the class warfare of the early socialist period.3 Haáz was ostracized for his bourgeois class background and his collection of folk art sent to storage (Haáz Rezsõ Múzeum 2016). The museum’s official history describes the socialist period as a time of enforced dormancy: “With hindsight after the passing of decades, we can certainly say that this isolation—this artificially induced ‘hibernating’ condition—condemned the collection to simple survival during the socialist period” (Haáz Rezsõ Múzeum 2016).

The notion that religious objects were no longer collected as folk art conveniently rewrites the history of late socialism, when Hungarian Catholic intellectuals made significant contributions to a government-driven revival of folk music, dance, and ritual life (Loustau 2019; Cotoi 2011; Hedeșan 2008; Kapaló 2011; Kürti 2000; Mihăilescu 2008; Bíró et al. 1987). As Katherine Verdery has argued, “revising history in Eastern Europe often means snipping out and discarding sections of the time line, then attaching the precommunist period to the present and future as the country’s true or authentic trajectory,” an operation meant to safely contain socialist intellectual life in the past (Verdery 1999, p. 124). In Western Europe, recent exhibitions of medieval Catholic art also draw on the notion of a hibernating cultural sensibility, a latency whose existence is said to legitimize the Catholic Church’s effort to establish a Catholic high culture as constitutive of normative French secularism (Oliphant 2015, pp. 352–53). However, in Transylvanian Hungarian communities, religious intellectuals frame their “museumification” of religious art against the backdrop of socialist state-driven secularization and see themselves as correcting a politically mediated disappearance. Catholic devotional art is useful not just because it can reshape individual consumers’ subjective sensibilities, but because it can both rework and revive state-embedded intellectuals’ claim to represent the nation’s interests (see also Verdery 1991).

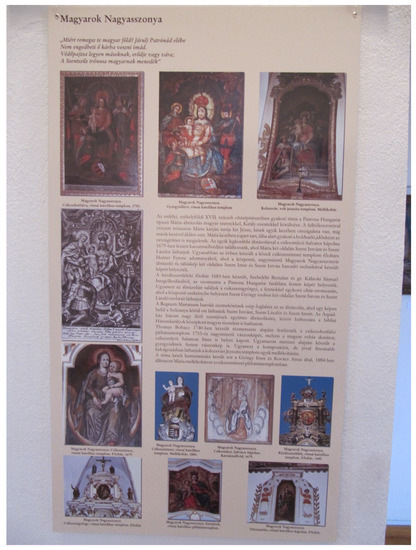

The curators of “Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania” confronted the same problem that Haáz had as he prepared his collection, insofar as he imagined these pieces to represent a Transylvanian Hungarian artistic tradition. He needed to find thematic and formal continuities among pieces from villages whose residents had little face-to-face contact with people outside these communities and did not think of themselves as self-consciously producing a Transylvanian regional artistic tradition. As Benedict Anderson argues, because members of even the smallest nation never know most of their fellow members, national intellectual entrepreneurs must identify these individuals with a larger community and construe their activities in such a way that “in the minds of each lives the image of their communion” (Anderson 1987, p. 15). The disparate pieces had no essential thematic unity. Instead, curators were challenged to organize the selected objects to best establish their national and religious representativeness: their producers’ identification with a tradition of Transylvanian Hungarian Catholic devotional art. The thematic unity of the pieces was primarily achieved through posters that juxtaposed a number of the statues and icons—both those present in the gallery and others that remained in situ in village churches—under headings, photographs, and explanatory text.

For instance, artists’ depictions of a prominent Catholic and national motif, “The Great Lady of the Hungarians” (Magyarok nagysszonya), was accompanied by an excerpt from a poem comparing the shields, strongholds, and castles of other nations to the Virgin Mary’s throne, Hungarians’ safe harbor. Underneath this quotation, there was a row of evenly spaced photographic copies of iconographical depictions of the Great Lady of the Hungarians the curators had found throughout Transylvania. The accompanying text described how this motif emerged in the 17th century in Transylvania, where artists portrayed the Patroness of the Hungarians surrounded by Hungarian saints:

On a throne guarded by wreaths of clouds, Mary holds the little Jesus in her arms, in one of whose hands is the national orb, while in his other hand he offers a blessing. Mary holds a scepter in her other hand, and beneath her feet appears on occasion the national crest, more frequently the crescent of the moon (See Figure 3). Figure 3. Great Lady of Hungarians Placard.

Figure 3. Great Lady of Hungarians Placard.

Two additional photographs running down the left-hand side of the panel, along with a series of smaller pictures along the bottom, formed a frame for the textual explanation of the motif.

A large statue was positioned on either side of the doorway of the interior room of the exhibition, creating a mirror image of Mary “standing guard.” The placards were set at an even distance on the wall, suspended from hanging lanyards running along the top of the wall, and they were interspersed among altarpieces and painted icons. One of the icons included two smaller glass cases enclosing metal ex-votos in the shape of healed body parts, evidence of miracles individual devotees had attributed to Mary. In the Odorheiu Secuiesc exhibition space, the walls were painted plain white and track lighting hanging from the ceiling provided regular and even illumination. The Târgu Mureş exhibition was mounted in a long single-room, a hallway on the second floor of a downtown church (See Figure 4). As in Odorheiu Secuiesc, here the exhibition began with the oldest pieces adjacent to the entryway and progressing, according to the chronological layout planned by the curators, through to more recent mass-produced images of Mary from the 19th and 20th centuries. The walls were white with arched ceilings in the Gothic style. Alcoves and windows broke up the available wall space, such that the placards were forced into tight proximity alongside one another, although they were similarly hung from lanyards leading down beneath tracks along the ceiling. Lighting was provided naturally by the windows, in addition to lights suspended from at several places along the hallway. The overall effect was to allow for an unhurried, orderly, and respectful contemplation of fine art.

Figure 4.

Târgu Mureș Exhibition Space.

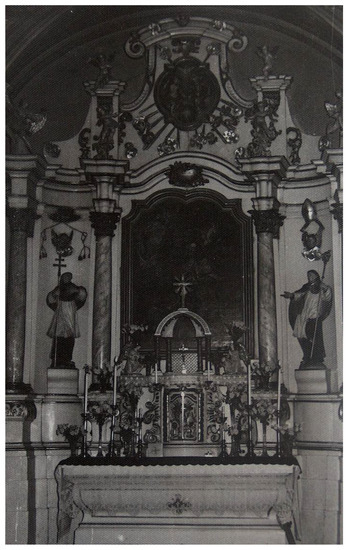

In the Ecclesiastical Art Museum of Târgu Mureş’s Saint John the Baptist Parish, curators stated that when they founded this institution in 2002, their goal was to recover endangered artistic treasures and display them as Transylvanian Hungarian Catholic heritage. The Rezső Haáz Museum’s traveling exhibition did not contradict this project but rather gave new momentum to the curators’ work to transform Catholic devotional objects from waste into valuable national treasures. This Catholic parish in downtown Târgu Mureş had set aside a second-floor hallway for a museum to display pieces of liturgical art that, prior to the collapse of the socialist regime in 1989, Romania’s late-socialist government had dismantled or discarded amid an effort to modernize major urban spaces such as Târgu Mureș. While in 1949 the government took ownership of a Târgu Mureş friary and church, it was not until the late 1960s that the government slated these structures for demolition as part of a project to renovate the city’s downtown (See Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The Theater and Square that Replaced Târgu Mureș’s Franciscan Catholic Church.

The socialist government represented the move to demolish—that is, transform into waste—the Franciscan church and its contents as part of its post-World War II plan to create “the new socialist man,” even as it also utilized the project as part of ongoing international relations campaigns. Many late socialist regimes embraced the belief that socialism’s new man needed a new built environment along with a new economic, cultural, and social system. As a result, throughout the Eastern Bloc architectural space became fundamental to the individual and social transformation that was envisioned, replacing the pedagogical processes that had originally stood at its heart (Fehérváry 2013; Sammartino 2017). This “ideology in infrastructure” produced significant amounts of waste when the socialist government tore down undesirable buildings such as Târgu Mureș’s Franciscan church and constructed in its place an open poured-concrete square facing the aggressively modernist National Theater (Humphrey 2005). At the same time, the socialist government made certain to announce that the head of the Catholic Church, Pope Paul VI, had given official approval to the project, which the regime interpreted as a sign that Romania was cooperating with local ecclesiastical authorities and protecting religious groups’ human rights (Ványolós 2016, p. 12). For instance, church–state cooperation in the name of human rights also took center stage in Romania’s late socialist international propaganda about its membership in the Christian ecumenical movement’s leading umbrella group, the World Council of Churches, which the government used to send the message that it had changed after decades when it was a pariah for imprisoning Catholic priests, liquidating the Greek Catholic Church, and banning public religious gatherings (Bottoni 2008; Hintikka 2000; Kaplan 2019).

The socialist-era government’s human rights rhetoric has been forgotten or dismissed by contemporary Transylvanian Hungarian intellectuals who reinterpret many of these built structures within the framework of post-socialist national contestation. According to historian Endre Ványolós, official socialist discourse provides an inadequate explanation for the project, since there was no need for a new National Theater during a period when the government’s funding plans focused on building housing developments, industrial factories, and stadiums (Ványolós 2016, p. 14). When Catholic priests rescued the baroque-style main altar from the ruins of the Franciscan church and continued to use it in worship, present-day intellectuals narrate this act as high-art Catholic resistance to state-sponsored ethnic animus (See Figure 6). While anthropologists studying Brazilian (Millar 2008) and Zambian (Hansen 2000) waste collectors have shown that neoliberal capitalism depends not only on formal wage labor but also on the informal work of “making trash into treasure,” in Romania and Hungary “recycling” waste as high art is a fundamentally political process (Gille 2004, 2007; Loustau 2020; Heintz 2006). These objects, according to the museum’s directors, fell into disuse not because Catholics had changed their tastes but “for reasons of historical transformation” (Magyar 2014).

Figure 6.

Period Image of the Altar of the Franciscan Catholic Church.

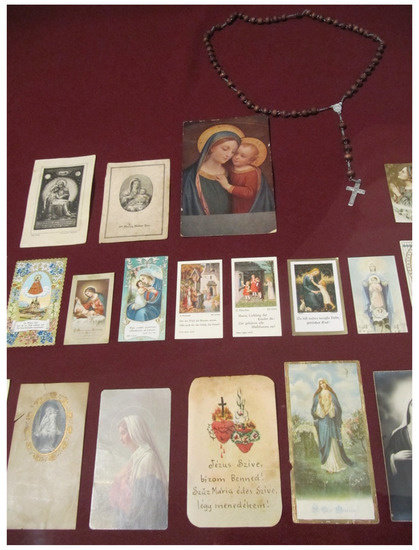

While newspapers celebrated the curators’ work to affect this transformation, with regard to the perceived worth of Catholic ritual objects, the exhibitions’ organizers also displayed mass-produced art objects that were neither old nor endangered by the pre-1989 government’s effort to transform regimes of artistic value in the name of the “new socialist man.” Photographs and mass-produced realistic portraits of Catholic saints, small enough to fit in a pocket or send in the mail as a postcard, are a widespread staple of the visual culture of contemporary Transylvanian Catholicism. The exhibition “Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania” in Târgu Mureş included a glass display case of such postcards along with strings of prayer beads called rosaries, hymnals, and other mass-produced contemporary religious paraphernalia (See Figure 7). The curators acknowledged the need to defend their inclusion of these pieces:

The pictorial and statuary representations of Marian devotionalism in Transylvania’s 19th and 20th centuries are difficult to measure with the benchmark of high culture. On occasion these have been treated as ‘shoddy commodities:’ mass produced and humbly crafted pictures and statues. Nevertheless, they are crucial appurtenances of contemporary Marian devotionalism.(Mihály 2010, p. 3)

Figure 7.

Exhibition Case Containing Mass Produced Prayer Cards.

The defensiveness in this statement speaks to the multiple challenges that destabilize collaborations between national art historians and ethnologists. The intellectual disciplines of Hungarian art history and ethnology not only embrace contradictory missions but also compete against each other from unequal positions within the broader field of Hungarian national cultural production. In their work on behalf of museums, Hungarian art historians are trained to educate the public to consume national traditions of high art. Hungarian ethnologists define their object of study as popular or vernacular artistic practices. While ethnologists represent these practices as pre-modern survivals in the present, they have begun to broaden their object of study to include contemporary mass-produced material culture when it appears in the non-ecclesiastical and popular social settings they conventionally study. The postcards’ inclusion in a program about Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania reflects the influence of ethnology’s changing purview.

However, the passage defending the postcards’ inclusion is written from the art historian’s perspective, using this discipline’s vocabulary. The phrase “shoddy commodities” suggests the legitimate connoisseur’s critique of middlebrow culture’s knockoff imitations of high art objects, such as poster versions of impressionist paintings. While the objects of the ethnologists’ craft must be defended, the exhibition’s high art objects do not merit such excuses. In the catalog, they are simply described and provenanced; their presence in the museum goes without justification. In this case, “Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania” invited experts from the two disciplines to collaborate, but not on equal ground when it came time to display the objects in museums such as Saint John the Baptist’s Ecclesiastical Art Museum.

Other exhibitions reclaimed mass-produced devotional art by inserting these objects into efforts to restore gravesites of World War I dead, thus reclaiming devotional art’s pedagogical functionality for projects that construct a Hungarian national past populated by these “heroic” figures. Beginning in the late 2000s, tourists to Transylvanian Hungarian communities—mainly middle-class urbanites from Hungary—began pairing trips for pleasure or relaxation with nationally framed charitable projects. Restoring cemeteries was a popular form of benevolent volunteerism for the nation that served not only tourists’ desire to strengthen bonds with cross-border Hungarian communities but also local governments’ need for legitimacy in the post-socialist period. Restoring the graves of World War I soldiers was a dramatic and visible way for local officials to break with socialist-era policy, which dictated that World War I dead be excluded from public commemorations because this conflict was an imperialist war (Popa 2013, p. 84).

Throughout Eastern Europe, restoring war graves has involved intensive collaborations with local authorities, as in Transylvanian Hungarian areas where village and county governments funded NGOs that welcomed volunteers to restore soldiers’ graves. Local Transylvanian Hungarian communities’ political agendas merged into the larger nation-building project of the Hungarian state through these acts nationally-framed benevolent service (Popa 2013, p. 82). As Georges Mosse argues, war cemeteries are constructed so that fallen soldiers are never dead and gone but continue to perform their mission of national renewal—in this case, by strengthening cultural and political ties between Hungarians on both sides of the border (Mosse 1979). In Transylvania, acts of benevolent service to restore fallen soldiers’ resting places are points of cultural and political encounter; World War I graves are contested sites where independent projects merge and local and national commemorations come together to create a structure of meaning that surrounds Hungarian soldiers’ bodies.

While Kosselleck argues that grave inscriptions are the primary material artefact for ascribing a national mission to the dead, in Transylvania, political labor performed on dead bodies extends far beyond the cemetery to include exhibitions of Catholic devotional art (Verdery 1999, p. 28; Koselleck 2002, pp. 285–300). During my fieldwork, I visited an exhibition of World War I-era Catholic prayer cards mass-produced for infantry, who had carried with them to the Eastern Front images of the Virgin Mary calming and comforting soldiers in stressful battle situations. The town council had used a room in a local school for the exhibition and timed it to coincide with a government-sponsored project to restore a cemetery for World War I soldiers. The soldiers’ heroic qualities dominated public discourse about that undertaking, in response to Romanian state officials’ use of this motif in commemorative projects begun in the early 2000s. Competitive claims-making and “ethnopolitical contestation,” Brubaker et al. have shown, are central features of post-socialist Romanian–Hungarian public discourse (Brubaker et al. 2007).

In the 1990s, Hungarian and Romanian officials used the notion of ethnic minority autonomy to exchange claims and counterclaims, but the discursive field of such claims-making soon expanded to include competitive heroizing when post-socialist Romanian governments restored Heroes’ Day celebrations. In addition, the government’s newly-created National Office for the Heroes’ Cult prompted Hungarian politicians to respond with efforts such as the gravesite restoration project in Sânmartin that highlighted the heroic characteristics of World War I dead (Popa 2013, p. 85; Bucur 2000, 2004, 2010). Soldiers are remembered not only for fighting against Romanian forces but also for exemplifying heroic victimhood in the name of justice for ethnic minorities during their subsequent careers. One former soldier, while serving as a federal judge, was fired twice for refusing to enforce unfair policies targeting the Hungarian minority (Daczó 2015).

The restoration project’s publicity embraced the era’s melodramatic descriptions of soldiers’ courage while overlooking the anxieties sparked by Catholic responses to modern mechanized warfare. World War I-era artists created cards that tailored prayer practice to the conditions of modern mechanized warfare. Before World War I, attacks were scheduled and soldiers could predict when they would be sent into battle, whereas now death could come at any time. Hungarian Catholic soldiers, who like all Catholics had been taught that priests must absolve their sins to guarantee their entry into heaven, often needed both absolution and comfort at a moment’s notice.

The illustrations position Mary in and around soldiers marching to battle, suffering from wounds, and dying. She stands above a soldier as he supported the body of a bloodied and wounded friend, with the caption, “The Good Friend in Trouble.” The Ave Maria text accompanies an illustration of a trench full of bloodied corpses. Several bodies hang over the trench’s edge, depicting how mechanized warfare made death at a distance a frequent occurrence. The Virgin Mary is standing in No Man’s Land below the caption, “Ave Maria,” a two-word phrase that declares her glory.

These prayers and images sparked anxiety as much as they consoled, according to historian Krisztina Frauhammer, an ambivalence that contradicts the findings of cultural theorists Susan Stewart and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in their research on the uses of photography within domestic settings. Both Stewart and Csikszentmihalyi describe photographs as a “fixed” medium and thus more conducive for use in consolidating selfhood through reflection, meaning-making, remembrance, and contemplation (Csikszentmihalyi and Halton 1981). On the other hand, Frauhammer notes that Hungarian Catholics worried about the efficacy of the quick, rote-like prayers soldiers were being encouraged to adopt for wartime use. One Hungarian Catholic bishop eased these fears by suggesting that sentiment mattered most: “Even if it is short, the soldier’s prayer should be practical and sincere” (Frauhammer 2019, p. 140).

In another card, Mary bends over a fallen and bleeding soldier. His soul is right then rising from his body. A short poem serves as the caption: “Without the patria, there is no life. Cast light and glory on him! Help us in the last hours! Forgive us our sins!”4 Along with the Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Virgin Mary was the foremost symbol of the salvific power of love, which the Church saw as the source of wartime soldiers’ virtues, including obedience, patience, self-denial, and humility. The Austro-Hungarian state and Catholic Church had as its main goal, in Krisztina Frauhammer’s words, “to provide emotional encouragement, consolation, and support that one could only muster through concepts of nation and religion” (Frauhammer 2019, p. 140). Mary sanctifies sacrificial death for the nation and guarantees salvation as consolation while reinforcing a culture of sentimentality centered on the intimacy of bonds between women and their male kin (Frauhammer 2019, p. 139).

Postcards on display in Sânmartin implored soldiers to take on a sentimentally heroic and noble attitude at home, as well. These images in particular sent the message that the chaos, violence, and danger of the war could not be contained to the front. In one scene, Jesus bars the way through the front door of a house from a civilian carrying an axe. “If the man is away at war/God protects his house/” reads the rhyming caption, “Treat him like your neighbor/Don’t covet his wealth.” On another card, a solder is shown inside a house as he intervenes to prevent another man from attacking a defenseless woman. She has flung her torso around toward a cradle in the foreground. At the cradle’s edge, the artist allows us to glimpse an infant’s chubby white arm reaching for the woman. Meanwhile, the soldier stands perfectly straight, barring the man’s way with a bold gesture of his outstretched arm. In rhyming couplets, the caption reads, “Having left his beloved home/The man of the house has long been gone/Fate is trying her womanly heart/For this reason, do not commit rape!”

These melodramatic messages took shape against the backdrop of radical social transformations in Hungarian communities. Indeed, Hungarian culture was not alone in seeing a growth of mass-marketed melodramatic narratives. Historian Peter Brooks identifies the origins of melodrama in European history as marking “the final liquidation of the traditional Sacred and its representative institutions (Church and Monarch), the shattering of the myth of Christendom […] and the invalidation of literary forms […] that depended on such a society” (Brooks 1976, p. 15). In France, during the mass absences caused by mobilization for World War 1, according to William Christian postcards “mobilized hearts” to make absent family members present: “[T]he virtual accompaniment that many loved ones experienced [through postcards] provided a protective presence through their correspondence” (Christian 2012, p. 165). Postcards suspended senders and recipients between the poles of complete absence and presence, and subjectively between the sentiments of great longing and joy. In Christian’s words, “The postcard trade encouraged the notion of absence combined with fondness, and combining images was a good way to picture the virtual reunion created by the card when sent” (2012, p. 132). Against the backdrop of the uncertainties and ambiguities of modernity, melodrama rehearses narratives of moral disambiguation, the recognition of virtue and villainy, and the pleasures of a moral mapping of the world.

3. Contemporary Devotional Art for a Complete Hungary

Through the 2010s, increasing numbers of Hungarian intellectuals, supported by Hungary’s new center-right government, began to complain about the limits of treating Marian devotional art as heritage, a focus evident in both the Rezső Haáz Museum’s “Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania” exhibition and more local displays such as Sânmartin’s World War I memorabilia show. Even into the 2000s, public discussions about the important Hungarian Marian relic, King Stephen’s Holy Crown, were already signifying national intellectuals’ dissatisfaction with museums’ backward-looking approach to Marian devotional art. In the late 1980s, Church and government officials in Hungary organized a traveling exhibition of the crown that Hungary’s first Christian monarch, King Stephen, is believed to have offered to the Virgin Mary in return for her protection and patronage of the Hungarian nation (Hann 1990).

While the crown remained on display first in the National Museum and then Budapest’s parliament building, some national intellectuals complained that viewing the Holy Crown behind glass in a museum did not foster a deep sense of identification with King Stephen and failed to inspire a devotional attitude toward the Virgin Mary. Hungarian historian László Péter observed how throughout the 1990s, “Holy Crown societies” formed to promote everyday awareness of this relic’s ongoing role in Hungarian public life, arguing that the crown was not “something to be tucked away in a museum” but rather “a living tradition and a part of national identity in this sense” (Péter 2003, p. 502, emphasis in original).5 While anthropologist László Kürti has written about the Hungarian government’s mimetic reproduction of the socialist-era tour of the relic, the Holy Crown societies identified by Péter represented intellectuals’ growing urge to change the purview of Catholic devotional art exhibitions, expanding this field beyond acts of merely preserving an inherited tradition (Kürti 2015, pp. 247–49).6

In response to these complaints and building on models provided by other traveling exhibitions of devotional art, in the 2010s, a group of prominent right-wing intellectuals constellated around a traveling exhibition of twenty-six living artists’ depictions of the Virgin Mary, titled “Blessed Lady” (Boldogasszony) (See Figure 8). The exhibition originated in 2010 at a private Budapest gallery, the Forrás Gallery, but over the next ten years traveled to forty museums, churches, and government exhibition halls around Europe. With financial support from the government’s Research Institute for National Strategy, the exhibition visited Hungarian minority communities in Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, Austria, and Ukraine, advancing the institute’s goal of reuniting a Hungarian nation divided by state borders. Before the Research Institute took on this objective, Norbert Tóth, the Forrás Gallery’s chief curator, noted that presenting the work of contemporary Transylvanian Hungarian artists was necessary because, “we can only grasp a complete picture of our Hungarian culture by recognizing the distinctive richness of the various parts of our nation” (Pálffy 2017). In Tóth’s essay, published in the gallery’s exhibition catalog for “Blessed Lady” and which I purchased in 2011 when the collection came to Cluj-Napoca’s National Museum of Art in Romania, he extended this mission to the field of Marian devotional art through emphasizing tradition’s dynamic nature: “The defining artists of the age, from time to time, use aesthetics—that is, the works of art that reflect the orderly and balanced relation between God and nature—to pass on and reformulate a community’s traditions” (Antall and Sárba 2012, p. 17).

Figure 8.

Invitation to Boldogasszony Exhibition Opening.

He hoped that Hungarians living in the Carpathian Basin and divided by the region’s political borders would converge upon the Forrás Gallery’s “Blessed Lady” exhibition, whereby growing numbers of Hungarians would envision themselves united together under the banner of Mary and discover that in the minds of each Hungarian resides the image of their communion, a process akin to what Anderson described in his account of the nation as an imagined community. Tóth helped establish the exhibition’s right-wing bona fides by opening the catalog with work by Hungary’s most famous right-wing architect and designer, Imre Makovecz. According to sociologist Luca Kristóf, Makovecz had become a favorite of right-wing Hungarian President Viktor Orbán when Makovecz welcomed the politician into conservative circles as he was transitioning from anti-communist radical to right-wing nationalist (Kristóf 2017, p. 136; Fehérváry 2013, p. 147). By the mid-2010s, the “Blessed Lady” exhibition had become allied with the illiberal political agenda of the influential president of the Hungarian Academy of Arts, György Fekete, who saw this collection of contemporary Marian devotional art as an antidote to exhibitions that had earned the ire of Hungary’s Reformed and Catholic Churches for blaspheming against Jesus’s teachings. “There must not be blasphemy in state-run institutions,” he complained in a famous 2012 interview. “This is about a Hungary built on Christian culture; there is no need for constant and perpetual provocation.”7

Fekete applauded the exhibition’s emphasis on rebirth during its 2015 opening at Budapest’s state-owned Garden Bazaar gallery, since the space itself had been recently renovated—“reborn,” in his words—as part of the right-wing Hungarian government’s urban redevelopment plan, which sociologist Bence Kováts has criticized as the construction of spectacle and “political commodification” of urban space (Kováts 2014). Like Tóth, Fekete emphasized the Virgin Mary’s symbolic role in representing the whole of Hungarian culture: “We want to serve the goal of reunifying the border-transcending nation by raising awareness of the cult of Mary in its role of representing Hungarian solidarity.” The artwork gathered together for “Blessed Lady” thus has a future-oriented and political purpose that aligns with the right-wing agenda of Hungary’s governing Fidesz party to establish for itself a leading position in the project of creating a border-transcending national cultural unity (See Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Invitation to the Exhibition at the Varkert Bazar.

Today, Transylvanian Hungarians live in multiple enclaves throughout this region, making up the majority in several small cities and a small portion of other larger ones. A subdued rivalry plays out as each city’s Transylvanian Hungarian intellectual leadership claims a representative role in shaping the minority community’s culture (Bárdi 2004, pp. 120–27; Bottoni 2008; Brubaker et al. 2007). Since more than half of Transylvania’s ethnic Hungarians are Catholic, characteristic genres of Catholic devotional art have also played an important role in constituting this competitive process through which art institutions in these cities compete to construct Transylvanian Hungarian minority cultural identity. While I have argued that this intra-regional competition informs recent exhibitions of Catholic art in Transylvania, artistic shows about the Virgin Mary also take place at local and national levels. In the case just discussed, the Forrás Gallery’s “Blessed Lady” exhibition, Catholic art serves not only to integrate Transylvanian Hungarian artists into a “full picture” of Hungarian culture but also legitimizes the creation of the right-wing government’s projects to build cultural infrastructures for new arts institutions. Exhibitions such as “Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania” also fuel local officials’ responses to the Romanian state’s politics of commemorating war dead.

Exhibitions of Hungarian Catholic art recategorize objects, marking both trash and ritual objects into fine art and representative examples of a shared heritage. Beyond Catholic art’s ability to shape personal subjectivity, a notion that Hungarian national culture shares an affinity with Catholic devotional culture and that Hungarians should and do feel a special allegiance to the Catholic Church, lies this process of moving devotional objects from storage spaces and trash bins to museums and art galleries. Catholic art animates the political claims of diverse institutions and intellectual fields at the local, regional, and state levels throughout both Transylvania and Hungary.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Harvard University, Application Number: F16729-105.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See especially Luehrmann’s analysis (Luehrmann 2011, pp. 4–6). |

| 2 | While Hungarian-speakers in Transylvania and Hungary use Hungarian versions of place names in everyday speech, I give the legally recognized versions of place names. This follows Brubaker et al.’s convention. For the Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania catalog, see (Mihály 2010). For publicity about the Sânmartin exhibit, see (Daczó 2015). For the “Blessed Lady” catalog, see (Antall and Sárba 2012). |

| 3 | The museum’s publicity describes how in the late 1940s and early 1950s Romania’s socialist regime forced Rezső Haáz first from his teaching position and then from his directorship of the museum. Haáz tried to demonstrate his demonstrate his sympathy for the government’s policy of class warfare against the bourgeoisie by joining the Social Democratic Party (Haáz Rezsõ Múzeum 2016). |

| 4 | The Hungarian text reads, “Haza nélkul nincsen élet/Derits rá fényt, dicsőséget/Végső órán segíts minket/Bocsásd meg vétkeinket.” |

| 5 | For a comparable case, see Russian Orthodox complaints that teaching Orthodoxy from a cultural perspective threatens to make it “boring” (Köllner 2016, p. 377). |

| 6 | These include the ceremonial installation of the Holy Crown in the Hungarian Parliament and the relic’s one-day visit to the Hungarian Cardinal’s residence in Esztergom. |

| 7 | The interview is available on Youtube.com at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PErD2Bm5Des, (accessed on 4 December 2020). |

References

- Anderson, Benedict. 1987. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Antall, István, and Katalin Sárba, eds. 2012. Boldogasszony [Blessed Lady]. Budapest: Forrás Galéria. [Google Scholar]

- Bárdi, Nándor. 2004. Tény és Való: A budapesti kormányzatok és a határon túli magyarság kapcsolattörténete [Fact and Reality: The History of Relations between the Budapest Government and Cross-Border Hungariandom]. Pozsony: Kalligram. [Google Scholar]

- Biíroó, Zoltán, József Gagyi, and János Péntek. 1987. Néphagyományok új környezetben: Tanulmányok a folklorizmus köréből. Bucharest: Kriterion. [Google Scholar]

- Bottoni, Stefano. 2008. Sztálin a Székelyeknél. A Magyar Autonóm Tartomány Története (1952–1960). [Stalin and the Székelys: History of the Hungarian Autonomous Region]. Miercurea Ciuc: Pro-Print Könyvkiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Peter. 1976. The Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama and the Mode of Excess. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Rogers, Margit Feischmidt, Jon Fox, and Liana Grancea. 2007. Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town. Princeton: Princeton U. [Google Scholar]

- Bucur, Maria. 2000. Between the Mother of the Wounded and the Virgin of Jiu: Romanian Women and the Gender of Heroism during the Great War. The Journal of Women’s History 12: 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucur, Maria. 2004. Edifices of the Past: War Memorials and Heroes in Twentieth Century Romania. In Balkan Identities, Nation, and Memory. Edited by Maria Todorova. New York: NYU Press, pp. 158–79. [Google Scholar]

- Bucur, Maria. 2010. Of Crosses, Winged Victories, and Eagles: Commemorative Contests between Official and Vernacular Voices in Interwar Romania. East Central Europe 37: 31–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, William. 2012. Divine Presence in Spain and Western Europe 1500–1960: Visions, Religious Images and Photographs. Budapest: CEU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cotoi, Cătălin. 2011. Sociology and Ethnology in Romania: The Avatars of Social Sciences in Socialist Romania. In Sociology and Ethnography in East-Central and South-East Europe: Scientific Self-Description in State Socialist Countries. Edited by Ulf Brunnbauer, Claudia Kraft and Martin Schulze Wessel. Munich: Oldenbourg Verlag, pp. 130–55. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, and Eugene Halton. 1981. The Meaning of Things: Domestic Symbols and the Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daczó, Katalin. 2015. Csíkszentmárton és Csekefalva hősei [The Heroes of Csíkszentmárton and Csekefalva]. Hargita Népe. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/azidoharcokatujrazii/home/6-haborus-emlekkepek-a-hargita-nepe-a-nagy-haborurol/csikszentmarton-es-csekefalva-hosei (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Demeter, Csanád. 2014. Rurbanizáció: Területfejlesztési és modernizációs politika Székelyföld elmaradott régióiban—1968–1989 [Rurbanization: Spatial Development and Modernization Politics in Isolated Parts of the Szeklerland]. Miercurea Ciuc: Státus Kiadó. [Google Scholar]

- Fehérváry, Krisztina. 2013. Politics in Color and Concrete: Socialist Materialities and the Middle Class in Hungary. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frauhammer, Krisztina. 2019. Imák és olvasatok: Imakönyvek a 19–20. századi Magyarországon [Prayers ad Readings: Prayer Books in 19th and 20th Century Hungary]. Szeged: MTA-SZTE Vallási Kultúrakutató Csoport. [Google Scholar]

- Gerencsér, Dóri. 2016. Erdélyi barangolások hegyen-völgyön [Transylvanian Spelunkers in Both Mountains and Valleys]. Világjáró: Utazási Magazin. Available online: https://vjm.hu/erdelyi-barangolasok-hegyen-volgyon/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Gille, Zsuzsa. 2004. Europeanising Hungarian Waste Policies: Progress or Regression? Environmental Politics 13: 114–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, Zsuzsa. 2007. From the Cult of Waste to the Trash Heap of History: The Politics of Waste in Socialist and Postsocialist Hungary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haáz Rezsõ Múzeum. 2016. A múzeumalapító Haáz Rezső. Available online: https://www.hrmuzeum.ro/haaz-rezso (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Hanebrink, Paul. 2006. In Defense of Christian Hungary: Religion, Nationalism, and Antisemitism, 1890–1944. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hann, Chris. 1990. Socialism and King Stephen’s Right Hand. Religion in Communist Lands 18: 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Karen. 2000. Salaula: The World of Secondhand Clothing and Zambia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeșan, Otilia. 2008. Doing Fieldwork in Communist Romania. In Studying Peoples in the People‘s Democracies: Socialist Era Anthropology in South-East Europe. Edited by Vintilă Mihăilescu, Ilia Iliev and Slobodan Naumovic. Berlin: LIT-Verlag, pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Heintz, Monica. 2006. Be European, Recycle Yourself! The Changing Work Ethic in Romania. Berlin: LIT Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hintikka, Kaisamari. 2000. The Romanian Orthodox Church and the World Council of Churches, 1961–1977. Helsinki: Luther-Agricola-Society. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey, Caroline. 2005. Ideology in Infrastructure: Architecture and Soviet Imagination. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 11: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapaló, James. 2011. Text, Context and Performance: Gagauz Folk Religion in Discourse and Practice. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, Jeffrey. 2019. More East than West: The World Council of Churches at the Dawn of the Cold War. Terrorism and Political Violence 31: 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köllner, Tobias. 2016. Patriotism, Orthodox religion and education: Empirical findings from contemporary Russia. Religion, State and Society 44: 366–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koselleck, Reinhart. 2002. The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing Concepts. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kováts, Bence. 2014. Political Commodification of the Inner City by Constructing Spectacles: Manipulation and Gentrification in the Contemporary Urban Development Agenda in Budapest. Available online: https://www.mri.hu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/bkovats_spectacle_budWEB.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Kristóf, Luca. 2017. Cultural Policy in an Illiberal State. Intersections 3: 313–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kürti, László. 2000. The Remote Borderland: Transylvania in the Hungarian Imagination. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kürti, László. 2015. Neoshamanism, National Identity, and the Holy Crown of Hungary. Journal of Religion in Europe 8: 235–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loustau, Marc R. 2019. Belief Beyond the Bugbear: Propositional Theology and Intellectual Authority in a Transylvanian Catholic Ethnographic Memoir. Ethnos: A Journal of Anthropology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loustau, Marc R. 2020. Transgressing the Right to the City: Urban Mining and Ecotourism in Post-Industrial Romania. Anthropological Quarterly 93: 1555–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luehrmann, Sonja. 2011. Secularism Soviet Style: Teaching Atheism and Religion in a Volga Republic. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magyar, Kurír. 2014 Egyházművészeti múzeum Marosvásárhely szívében [Ecclesiastical Art Museum in the Heart of Marosvásárhely]. Available online: https://www.magyarkurir.hu/hirek/egyhazmuveszeti-muzeum-mukodik-marosvasarhely-sziveben (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- McDannell, Colleen. 1995. Material Christianity: Religion and Popular Culture in America. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mihăilescu, Vintilă. 2008. A New Festival for the New Man: The Socialist Market of Folk Experts During the ‘Singing Romania’ National Festival. In Studying Peoples in the People’s Democracies: Socialist Era Anthropology in South-East Europe. Edited by Vintilă Mihăilescu, Ilia Iliev and Slobodan Naumovic. Berlin: LIT Verlag, pp. 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mihály, Ferenc, ed. 2010. Mária-tisztelet Erdélyben: Mária-ábrázolások az erdélyi templomokban [Marian Devotionalism in Transylvania: Portrayals of Mary in Transylvanian Churches]. Odorheiu Secuiesc: Haáz Rezsõ Múzeum. [Google Scholar]

- Millar, Kathleen. 2008. Making Trash into Treasure: Struggles for Autonomy on a Brazilian Garbage Dump. Anthropology of Work Review 29: 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, David. 1998. Visual Piety: A History and Theory of Popular Religious Images. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, David. 2005. The Sacred Gaze: Religious Visual Culture in Theory and Practice. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, David. 2012. The Embodied Eye: Religious Visual Culture and the Social Life of Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mosse, George. 1979. National Cemeteries and National Revival: The Cult of the Fallen Soldiers in Germany. Journal of Contemporary History 14: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, Elayne. 2015. Beyond Blasphemy or Devotion: Art, the Secular, and Catholicism in Paris. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 21: 352–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi, Robert A. 2003. “The Infant of Prague’s Nightie”: The Devotional Origins of Contemporary Catholic Memory. U.S. Catholic Historian 21: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, Robert A. 2005. Between Heaven and Earth: The Religious Worlds People Make and the Scholars Who Study Them. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pálffy, Lajos. 2017. Fókuszban a határon túli magyar alkotók [Cross-Border Hungarian Artists in Focus]. Magyar hírlap. Available online: https://www.magyarhirlap.hu/kultura/Fokuszban_a_hataron_tuli_magyar_alkotok (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Péter, László. 2003. The Holy Crown of Hungary, Visible and Invisible. Slavonic and East European Review 81: 421–510. [Google Scholar]

- Popa, Gabriela. 2013. War Dead and the Restoration of Military Cemeteries in Eastern Europe. History and Anthropology 24: 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Douglas. 2011. The Old Faith and the Russian Land: A Historical Ethnography of Ethics in the Urals. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sammartino, Annemarie. 2017. The New Socialist Man in the Plattenbau: The East German Housing Program and the Development of the Socialist Way of Life. Journal of Urban History 44: 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szász, Cs. Emese. 2010. Marosvásárhelyen a Mária-kultusz tárgyi emlékei [The Material Memories of the Cult of Mary in Marosvásárhely]. Available online: https://szekelyhon.ro/muvelodes/marosvasarhelyen-a-maria-kultusz-targyi-emlekei# (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Tarján, Tamás M. 2020. Székelyudvarhely: Erdély “legmagyarabb városa”. [Székelyudvarhely: Transylvania’s Most Hungarian City]. Rubicon Institute. Available online: https://rubiconintezet.hu/project/szekelyudvarhely-erdely-legmagyarabb-varosa/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

- Van Rompay, Lucas, Sam Miglarese, and David Morgan. 2015. The Long Shadow of Vatican II: Living faith and Negotiating Authority since the Second Vatican Council. Chapel Hill: UNC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ványolós, Endre. 2016. Modern tértörténetek Kelet-Európából [Modern Spatial Histories from Eastern Europe]. In Tértörténetek. Edited by Dezső Ekler. Budapest: L’Harmattan, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Verdery, Katherine. 1991. National Ideology Under Socialism: Identity and Cultural Politics in Ceaușescu’s Romania. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Verdery, Katherine. 1999. The Political Lives of Dead Bodies: Reburial and Postsocialist Change. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wanner, Catherine. 2007. Communities of the Converted: Ukrainians and Global Evangelism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wanner, Catherine, ed. 2012. State Secularism and Lived Religion in Soviet Russia and Ukraine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Young, Donna. 2008. Clothing of Piety, Clothing of Poverty: Object Lessons in a Convent School. Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 73: 377–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).