Re-Examining Death: Doors to Resilience and Wellbeing in Tibetan Buddhist Practice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. What Is Death? New Answers to an Old Question

Clearly, death is not a self-evident phenomenon. The margins between life and death are socially and culturally constructed, mobile, multiple, and open to dispute and reformulation.

3. Cardiorespiratory to Neurocentric Death

Not only have biomedical advances changed the ecology, epidemiology, and economics of death, but the very ethos of death—in the most abstract possible sense—has changed. Far from being clearer, the line between life and death has become far more blurry.

3.1. Historical and Theoretical Background

3.2. Biological and Socio-Cultural Death

3.3. Brain Death

The brainstem contains (in its upper part) crucial centers responsible for generating the capacity for consciousness. In its lower part, it contains the respiratory center. It is death of the brainstem (nearly always the result of increased intracranial pressure) that produces the crucial signs (apneic coma), which doctors detect at the bedside, when they diagnose brain death.

First of all, the analysis has to do with the self as agent and the self as experiencer. In this sense it’s very important. But now let us look to the flow of our experience: feelings of sadness and so forth arise in response to certain experiences. Then certain desires arise in our consciousness. From such desires the motivation to act may arise, and together with this motivation to act comes a sense of self, of ‘I’.

3.4. The Problem with Viewing Death as a Biological Event

4. Tibetan Buddhist Notion of Death

Bardo: Death as a “Moment of Transition”

5. How Do We Respond to Death?

Everything that man does in a symbolic world is an attempt to deny and overcome his grotesque fate. He literally drives himself into a blind obliviousness with social games, psychological tricks, personal preoccupations so far removed from the reality of his situation that they are forms of madness—agreed madness, shared madness, disguised and dignified madness, but madness all the same.

5.1. Terror Management Theory: Mortality Salience

Perhaps the most primitive aspect of death is how we respond to it, how we spend most of our lives imagining it away, how we fear it as some sort of unnatural schism in space–time. Every time we talk about death, the food seems terrible, the weather seems dour, the mood sullen. Every time we think about death, we get so depressed we can’t hold a meaningful thought in our heads. Many families talk about death only after their loved one is in the ICU, hooked up to more gadgets than Iron Man.

5.2. Death: Collective Cultural Reference

5.3. Death as a Psychological Adaptation Cultural Tool

5.4. Death as a Moral Supervisor

5.5. Death as a Means to Attain a Better Life

5.6. Death as a Means to Unmask Ultimate Reality

6. How Can We Die?

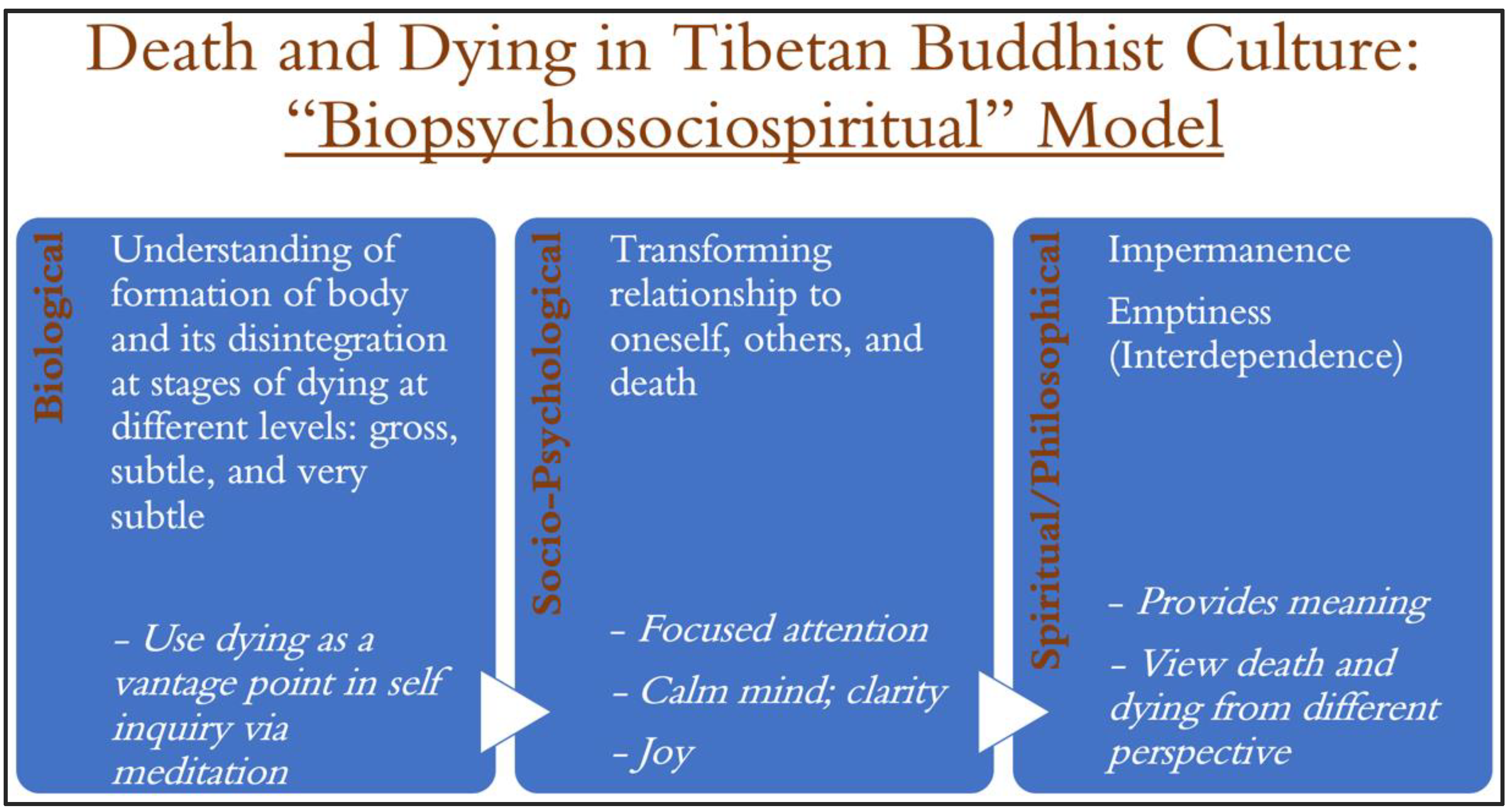

Tibetan Cultural Models of Ways of Dying

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Margaret Lock makes a similar case in her cross-cultural analysis of death (see, for instance, Lock 2002). |

| 2 | Geshe (Tib. dge bshes) or Geshema is a Tibetan Buddhist academic degree for monks and nuns. Geshe Lharam, which is the highest degree in Geluk tradition, is considered equivalent to a Ph.D. degree in the Western educational system. |

| 3 | Thugs dam is a state of meditation adept Buddhist practitioners engage in after clinical death. While in thugs dam, these practitioners are able to “impede physical flaccidity ordinarily preceding rigor mortis, retain a meditative state, suspend the process of decomposition, maintain warmth in the body” and occasionally, produce a uniquely pleasant fragrance (Zivkovic 2010, p. 176). |

| 4 | The persons’ names are replaced by pseudonyms in order to ensure anonymity. |

| 5 | Men-Tsee-Khang (Tib. House of Medicine and Astro. Science) is a research and education center of Tibetan Medicine in India. The Institute is a premier Tibetan Medical School outside Tibet, re-established by the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India, in 1961. |

| 6 | Tibetan doctors use pulse reading as one of the primary modes of making a diagnosis (other diagnosis techniques are urine analysis, observing, examining and touching different parts of the body, and talking to patients). Tibetan doctors read patients’ radial artery of both hands using each of their six fingers (pointer, middle, and ring) as the medium to decipher functions of internal organs and other related illnesses. I elucidate further on the Tibetan medicine mode of diagnosis in Chapter 4. (Also see Tidwell’s ethnographic work on how Tibetan doctors address and treat cancer via pulse and urine analysis, Tidwell 2017, pp. 376–410; Gonpo 1984). |

| 7 | For work elaborating on the topic of human consciousness in Tibetan Buddhist psychology, see (Thompson 2015). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | The Nyingma school is the oldest lineage tradition of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The other three lineage traditions are Kagyu, Sakya, and Gelug. Nyingma literally means ancient, for it is founded on the first translations of Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit to Tibetan in the eighth century. |

References

- Abramovitch, Henry. 2001. Death and Dying, Sociology of. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 3267–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aries, Phillip. 1974. Western Attitudes toward DEATH: From the Middle Ages to the Present. Translated by Patricia Ranum. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, Leonard, Samd Shemie, Jeannie Teitelbau, and Christopher J. Doig. 2006. Brief Review: History, concept, and controversies in the neurological determination of death. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia 53: 602–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Becker, Ernest. 1973. The Denial of Death. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beecher, Henry K. 1968. A definition of irreversible coma: Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death. JAMA 205: 337–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beecher, Henry K. 1970. Definition of ‘life’ and ‘death’ for medical science and practice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 169: 471–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkin, Gary S. 2014. Death before Dying: History, Medicine, and Brain Death. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, Jeffrey P. 2011. The Anticipatory Corpse: Medicine, Power, and the Care of the Dying. Notre Dame: University of Norte Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Maurice, and Jonathan Parry. 1982. Introduction: Death and the regeneration of life. In Death and the Regeneration of Life. Edited by Maurice Bloch and Jonathan Parry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Braswell, Harold. 2014. Death and Resurrection in US Hospice Care: Disability and Bioethics at the End-of-Life. Ph.D. thesis, ILA Department, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Brussel, Leen Van, and Nico Carpentier. 2014. Introduction: Death as a Social Construction. In The Social Construction of Death: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Edited by Leen Van Brussel and Nico Carpentier. London: Palgrave MacMillan UK, pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford, Terry. 1996. Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry: The Diamond Healing. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, Mike, and Shulgin Ann. 2019. Secret Drugs of Buddhism: Psychedelic Sacraments and the Origins of the Vajrayana. Santa Fe: Synergetic Press, ISBN1 9780907791744 (paperback). ISBN2 9780907791751 (ebook). [Google Scholar]

- Dorjee, Gyurdmey. 2007. The Tibetan Book of the Dead: First Complete Translation. Edited by Graham Coleman and Thupten Jinpa. Translated by Gyurdmey Dorjee. New York: Penguin Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1957. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, the Vol. 14. London: Hogarth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gawande, Atul. 2014. Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. New York: Metropolitan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Germano, David. 1997. Dying, death and other opportunities. In Religions of Tibet in Practice. Edited by Donald Lopez. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 493–548. [Google Scholar]

- Gonpo, Y. Yuthok. 1984. rGyud-bZhi (Four Tantra). Dharamsala: Men-Tsee-Khang. [Google Scholar]

- Gonpo, Yuthok Y. 2015. The Basic Tantra and the Explanatory Tantra from the Secret Quintessential Instructions on the Eight Branches of the Ambrosia. Translated by Thokmey Paljor, Pasang Wangdu, and Sonam Dolma. Dharamsala: Men-Tsee-Khang Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Green, James W. 2008. Beyond Good Death: The Anthropology of Modern Dying. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Jeff, Sheldon Solomon, and Tom Pyszczynski. 1997. Terror management theory of self-esteem and cultural worldviews: Empirical assessments and conceptual refinements. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Edited by Mark P. Zanna. San Diego: Academic Press, vol. 29, pp. 61–139. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, Roland R., Matthew W. Johnson, Michael A. Carducci, Annie Umbricht, William A. Richards, Brian D. Richards, Mary P. Cosimano, and Margaret A. Klinedinst. 2016. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology 30: 1181–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grob, Charles S., Anthony P. Bossis, and Roland R. Griffiths. 2013. Use of the Classic Psilocybin For Treatment of Existential Distress Associated with Cancer. In Psychological Aspects of Cancer. Edited by Brian Carr and Jennifer Steel. Boston: Springer, pp. 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, D. Gregory. 2003. Deconstructing death: Toward a poetic remystification and all that jazz. Journal of Poetry Therapy 16: 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajicek-Dobberstein, S. 1995. Soma siddhas and alchemical enlightenment: Psychedelic mushrooms in Buddhist tradition. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 48: 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halifax, Joan. 2008. Being with Dying: Cultivating Compassion and Fearlessness in the Presence of Death. Boston: Shambhala Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz, Robert. 1960. Death and the Right Hand. London: Cohen & West. [Google Scholar]

- His Holiness the Dalai Lama. 1998. The Four Noble Truths: Fundamentals of the Buddhist Teachings. Edited by Dominique Side. Translated by Thupten Jinpa. London: Thorsons. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, Michael Hviid. 2013. Deconstructing Death–Changing Cultures of Death, Dying, Bereavement and Care in the Nordic Countries. Odense: University of Southern Denmark Studies in History and socIal Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Sharon R. 2005. …And a Time to Die: How Hospitals Shape the End of Life. New York: Scribner. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Sharon, and L. Morgan. 2005. The Anthropology of the Beginnings and Ends of Life. Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 317–41. [Google Scholar]

- Korein, Julius. 1978. The Problem of Brain Death. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 315: 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubler-Ross, Elizabeth. 1969. On Death and Dying: What the Dying have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy, and Their Own Family Members. New York: Scribner Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, David. 1985. Death, Brain Death, and Ethics. Albany: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laureys, Steven. 2005. Death, unconsciousness and the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6: 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavi, Joshua Shai. 2005. The Modern Art of Dying: A History of Euthanasia in the United States. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lock, Margaet. 2002. Twice Dead: Organ Transplants and the Reinvention of Death. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Loy, David. 1992. Avoiding the Void: The Lack of Self in Psychotherapy and Buddhism. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 24: 151–79. [Google Scholar]

- Magnus, David. 2015. Persistent Problems in Death and Dying. The American Journal of Bioethics 15: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, Rachel E. 2018. Death Anxiety: The Worm at the Core of Mental Health. Psych. [Google Scholar]

- Menzies, Rachel E., and Ilan Dar-Nimrod. 2017. Death anxiety and its relationship with obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 126: 367–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, Ross G., Rachel E. Menzies, and Lisa Iverach. 2015. The role of death fears in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Australian Clinical Psychology 1: 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, Peter, and Richard Huntington. 1979. Celebrations of Death: The Anthropology of Mortuary Ritual. London, New York and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mollaret, Pierre, and M. Goulon. 1959. The depassed coma (preliminary memoir). Revue Neurologique 101: 3–15. (In French). [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neumann, Ann. 2016. The Good Death: An Exploration of Dying in America. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norwood, Frances. 2009. The Maintenance of Life: Preventing Social Death Through Euthanasia Talk and End-of-Life Care-Lessons from the Netherlands. Durham: Carolina Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nuland, B. Sherwin. 1994. How we Die: Reflections on Life’s Final Chapter. New York: A.A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa-de Silva, Chikako. 2006. Psychotherapy and Religion in Japan: The Japanese Introspection Practice of Naikan. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Palgi, Phyllis, and Henry Abramovitch. 1984. Death: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. Annual review of Anthropology 13: 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollan, Michael. 2018. How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence. New York: Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, John W., Jr. 1983. Dying and the Meanings of Death: Sociological Inquiries. Annual Review of Sociology 9: 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinpoche, Patrul. 1994. Words of My Perfect Teacher: A Complete Translation of Classic Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition. Padmakara Translation Group with a Foreword for the Dalai Lama. London: Altamire Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robben, CGM Antonius. 2004. Death and Anthropology: An Introduction. In Death, Mourning, and Burial: A Cross-Cultural Reader. Edited by Antonius Cornelis Gerardus Maria Robben. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Seneca. 2018. How to Die: An Ancient Guide to the End of Life. Translated by James S. Romm. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Sheldon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski. 1991. A Terror Management Theory of Social Behavior: The Psychological Functions of Self-Esteem and Cultural Worldviews. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. New York: Academic Press, vol. 24, pp. 93–159. [Google Scholar]

- Stolaroff, Myron. J. 1999. Are Psychedelics Useful in the Practice of Buddhism? Journal of Humanistic Psychology 39: 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, Jan, and Alan Cooper. 2005. Front Matter. In Physician’s Guide to Coping with Death and Dying. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt805z9.1 (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- Tart, Charles T. 1991. Influences of previous psychedelic drug experiences on students of Tibetan Buddhism: A preliminary exploration. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 23: 139–73. [Google Scholar]

- Teresi, Dick. 2012. The Undead: Organ Harvesting, the Ice Water Test, Beating-Heart Cadavers-How Medicine Is Blurring the Line between Life and Death. Rome: Pantheon. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Evan. 2015. Waking, Dreaming, Being: Self and Consciousness in Neuroscience, Meditation, and Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tidwell, Tidwell L. 2017. Imbibing the Text, Transforming the Body, Perceiving the Patient: Cultivating Embodied Knowledge for Tibetan Medical Diagnosis. Ph.D. thesis, Anthropology Department, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, Francisco J., ed. 1997. Sleeping, Dreaming, and Dying: An Exploration of Consciousness with the Dalai Lama. Boston: Wisdom Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Warraich, Haider. 2017. Modern Death: How Medicine Changed the End of Life. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Timothy J. 2007. Death in Contemporary Western Culture. Islam and Christian—Muslim Relations 18: 333–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, Tanya. 2010. The Biographical Process of a Tibetan Lama. Ethnos 75: 171–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, Tanya. 2014. Death and Reincarnation in Tibetan Buddhism: In-between Bodies. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Namdul, T. Re-Examining Death: Doors to Resilience and Wellbeing in Tibetan Buddhist Practice. Religions 2021, 12, 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12070522

Namdul T. Re-Examining Death: Doors to Resilience and Wellbeing in Tibetan Buddhist Practice. Religions. 2021; 12(7):522. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12070522

Chicago/Turabian StyleNamdul, Tenzin. 2021. "Re-Examining Death: Doors to Resilience and Wellbeing in Tibetan Buddhist Practice" Religions 12, no. 7: 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12070522

APA StyleNamdul, T. (2021). Re-Examining Death: Doors to Resilience and Wellbeing in Tibetan Buddhist Practice. Religions, 12(7), 522. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12070522