Abstract

In this article, we study women’s tattoos from a lived religion perspective. We describe how women’s tattoos express their inner lives, the religious dynamics associated with tattooing, and how they negotiate them with others. The sample used came from surveys and interviews targeting tattooed women at a confessional college on the East Coast of the United States. Women appropriate a prevalent cultural practice like body art to express their religious and spiritual experiences and ideas. It can be a Catholic motto, a Hindu or Buddhist sign, or a reformulated goddess, but the point is that women use tattoos to express their inner lives. We found that women perceive workplace culture as a hostile space for them to express their inner lives through tattoos, while they are comfortable negotiating their tattoos with their religious traditions. And they do so in a Catholic university.

1. Introduction

Tattooing is a social phenomenon whose cultural meaning is in flux (Silver et al. 2011). While, in the middle of the twentieth century, tattoos were considered a sign of marginal individuals and societies (Bell 1999; De Mello 2000), nowadays, they have become accepted, even becoming a fashion trend. As much as clothing and hairstyles, tattoos shape human bodies’ symbolic cultural capital, a project whereby individuals produce their appearance, choosing from a given cultural set of tools (Silver et al. 2011). Tattoos may be tools to challenge social mandates and exercise creativity and agency; however, class, race, and gender condition them (Dann et al. 2016).

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, researchers found, for the first time in Western societies, a correlation between tattoos and a positive image, even among people who did not have tattoos themselves (Armstrong et al. 2002). In 2012, two in ten Americans got a tattoo, a number that increased to three in ten by 2019, when those under the age of 55 were twice as likely to have at least one tattoo (IPSOS 2019). However, scholars point out that the association between tattoos and deviance is still present in a different way. More than the tattoos themselves, what is associated with deviance today is the type and location of the tattoo (Silver et al. 2011).

Tattoos have been studied as signs of memberships in risky professions or criminal cliques and as ethnic identity markers (Bell 1999; Galera and López Fidanza 2012; Sims 2018; Walzer Moskovic 2015). Here, we understand them as cultural creations, generated within a given context. We look at tattoos as manifestations of a human culture that occupy a niche as a potential expression of an inner experience (Leader 2016; Naudé et al. 2017).

While Dann et al. (2016) explore tattoos through the intersection of gender and class, here, we look at them at the intersection of gender and lived religion. Studies show that, in the U.S., across every religious affiliation and demographic (age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status), women are more engaged with religious practices than their male counterparts. However, in comparison to men, women do not have equal access to leadership positions in their churches (Pearce and Gilliand 2020; Putnam and Campbell 2010). Without denying the paradox (more participation, less power), we will explore women’s religiosity from a lived religion perspective. A “lived religion” perspective (Ammerman 2014, 2020; McGuire 2008) assumes that everyday religious practices by ordinary persons are not limited by institutional mandates. It understands religion as a space where subjects exercise their autonomy and produce and reproduce signs and meaning, through cultural idioms that are available to them, not limited by their religious confessions. Lived religion is what ordinary people do when they do religion in their daily lives. This approach allows us to look beyond institutional structures, permitting us to see the actors’ capacity to produce and express religious meaning in daily life, turning our attention to the embodied, discursive, and material dimensions of life (like tattoos), where sacred things are being produced, encountered, and shared (Ammerman 2020; Bender et al. 2013; Edgell 2012; McGuire 2008; Meyer and Houtman 2012; Morello 2019a; Morello et al. 2017; Rabbia et al. 2019; Salas and De la Torre 2020; Williams 2015).

Religiosity shapes and is shaped by historical circumstances and local cultures; religious practices occur within a repertoire of available cultural practices (Ammerman 2020). Today, for younger generations, tattoos have become a practice that is not only culturally available but also socially accepted, and a practice through which they can express their inner quest. Since the work of Émile Durkheim ([1915] 1965), sociologists have been studying tattoos as part of religious experiences, a form of self-expression that enables respondents to project who they are, and to tell a story about their life journey, where they have been, and what experiences have defined them (Barras and Saris 2020; Dougherty and Koch 2019; Naudé et al. 2017). For younger people, tattoos may be used to express a passage into adulthood, a spiritual threshold that establishes a sense of self (Dann et al. 2016).

In this article, we explore tattoos as expressions of college women’s inner lives, a venue for women to manifest their religious, spiritual experiences. What can we learn about college women’s lived religion by studying their tattoos?

2. Tattoos, Religion, and Women

There is a long tradition of religious tattoos (Morello 2021; Petkoff 2018) that might have started with Otzi “the iceman”, a 5250-year-old mummified male with 61 tattoos, discovered in 1991, although we do not know if any of them were religious. Closer to our times, in his study of the basic forms of religious life, Durkheim mentioned tattoos as “material emblems” of “collective sentiments”, “means by which the communion of minds can be affirmed” (1915, pp. 264–65). While, for Durkheim, tattoos materialized the belonging to a moral community, today, individuals use religious tattoos as a reminder of their faith and as a motivational purpose to live by in accordance with these religious beliefs (Dougherty and Koch 2019).

Recently, in the United States, qualitative studies among religious (Evangelical) college students pointed out that not only were religious people who got tattoos more likely to associate their body art with some aspect of their spiritual life, but religiously active students were also found to not believe that the Bible banned tattoos, and even reported support from their religious homes when they got them (Firmin et al. 2008). We acknowledge that religious mandates about tattoos are often at odds with what respondents expressed here. However, following the “lived religion” perspective, we study respondents’ perceptions of their religious traditions (and their negotiations with these perceptions) and not the religious mandates themselves.

Maldonado-Estrada (2020) has explored men’s tattoos, as devotional objects in the context of a Catholic festivity in Brooklyn, and among a group of devotees. Tattoos and religious dynamics share features like discernment, asceticism, and commitment (Morello 2021), expressing a pledge with the future, a material statement for others to see (Koch and Roberts 2012). Religious tattoos that portray religious images and Biblical references are more likely than non-religious tattoos to face the owner, and tend to be smaller than non-religious tattoos, mainly among women (Dougherty and Koch 2019). However, other research shows that the religious character of the tattoo is not necessarily in the image depicted, but in the spiritual intention of the bearer (Morello 2021), which is the key feature of everyday religious practices (Ammerman 2020).

The ambiguities regarding tattoos, either considering them as a sign of deviance or an accepted mainstream middle-class practice, are present in the research about women and tattoos. Through tattoos, women are able to resist some mandates imposed upon their bodies. Tattoos allow women to exercise agency, to construct their bodies while navigating social perceptions. This is particularly relevant in the case of college women who face dynamics of hook-up culture that contribute to the normalization of sexual violence. By tattooing themselves, women reclaim their bodies in their own terms, claiming their own aesthetic choices through a cultural tool that allows them to communicate with others. Tattoos may go far deeper than the superficial skin. Women may embark on long-term journeys of body modification to conform to or resist cultural femininity norms (Harris 2017; Lamont et al. 2018; Wade 2017). Tattooing can be a way to “retrieve the female body from the oppressive gaze” (Dann et al. 2016, p. 44), enabling women to create and perform their femininity on their own terms, and not submitting to the ways in which women perceive society’s expectations towards them.

The ways in which women wear their tattoos might embody either conformity or resistance to social concepts of femininity. Tattoos may be a tool for women to challenge the relations of power on their bodies, a way to subvert regulations on their bodies, or a practice through which women choose what and when to reveal or hide (Barras and Saris 2020). For Dann and Callaghan (2019), tattoos represent both a woman’s authentic self and a communal position. Women use tattoos as a source of power, strength, and resilience, most notably when these tattoos come out of a desire to heal from trauma. Tattoos can be transformative, an alternative way to signify beauty, sexuality, and agency (Reid-de Jong and Bruce 2020).

However, social constraints are present. In today’s culture, tattoos are socially accepted for women when they have a purpose (memorial, healing, care, identity, relations) and are not “mere” decoration (Dann and Callaghan 2019; Dann et al. 2016).

This article explores how women wear tattoos to express their inner lives, the experiences they express through them, and how they negotiate tattoos with the others’ gaze on their body (Dann et al. 2016).

3. Methodology

The sample used to answer these questions came from surveys and interviews targeting tattooed women at a confessional college on the East Coast of the United States. After the I.R.B. approval, the research team launched an online survey, between January 2020 and March 2020. The prompt placed the inquiry as a study on “meaningful tattoos” and invited individuals (male and female) who identified as “Catholics, Protestants, from other religious backgrounds, non-affiliated and non-believers” to answer the survey. It was implemented through Qualtrics and respondents answered questions about their demographics (date of birth, gender, ethnicity), religious affiliation, tattoo count, and affiliation with the university. Additionally, there were open-ended questions regarding the respondents’ perceived significance of their tattoo, as well as an option to share a photo of their tattoo. The link to the survey was uploaded to different social media groups for the university classes of 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023. It was also printed on flyers and displayed in heavy-traffic areas of the campus. The survey concluded with 91 responses.

Participants interested in volunteering for an interview were invited to provide their contact information. The goal of these interviews, which lasted about 30 minutes and were conducted by female and male undergraduate research assistants, was to allow participants to elaborate on the meaning of their tattoo(s). We also asked about the circumstances of getting the tattoos, others’ reactions (family, friends), and the process of getting it (pain, cost, location, how they decided on the location on their body). The 21 interviews took place between March 2020 and July 2020. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the interviews were conducted online through different video platforms. For this article, we selected a sub-sample of the 41 female participants in the survey and the 13 female interviewees.

4. Findings

Out of the 41 female participants who completed the survey, 28 identified as heterosexual, one as homosexual, nine as bisexual, two as other, and one undisclosed. Since the school where we conducted our research is affiliated with the Catholic church, it is not a surprise that most of respondents were Catholic (19), seven were Christians (six Protestants and one Eastern orthodox), four were from other religious confessions (Jew, Hindu, Muslim), and 11 were non-affiliated. More than half of the sample, 21 persons, had one tattoo; ten had two, and another ten had three or more. The pool encompassed respondents including one faculty member, three administrators, three graduate students, and 34 undergraduate students. Since the poll was advertised on undergraduate social media sites, our sample was not a surprise in terms of generations: 39 out of 41 respondents belonged to Generation Z (born between 1997 and 2003). In this regard, this study reflects the experience of a group of young persons, who volunteered to be interviewed, in a “regular life” context, contrasting Maldonado-Estrada (2020), who chose to interview individuals of an older generation, who belonged to a religious brotherhood, in the context of a religious celebration.

As mentioned, some respondents provided their contact information and volunteered to be interviewed. Of the 13 women interviewed, 11 were undergraduate students and the remaining two were administrative members; five identified as Catholics, two identified with other Christian denominations (Protestant and the Seventh-day Adventist World Church, SDA); two identified with non-Christian traditions (Judaism and Hinduism); one identified as Agnostic, and the remaining three as “non-affiliated”.

The 11 interviewees had 30 tattoos. Six tattoos were sentences, words, letters, or a question mark; four of them were openly religious in American culture (biblical text, spiritual sentence, Om sign, goddess figure); seven involved animals, (snakes, owl, rabbit, butterfly, koi fish, lion), and three portrayed vegetables (flowers, avocado). Nature (mountains, planets, moon, stars) was represented in two of them, and three showed pop culture items (middle finger, Pikachu, Harry Potter); female figures appeared in three (goddess, grandmother, art drawing) and four depicted other things (cards, compass, anchor, hands). Most of the tattoos were small figures of around one or two inches (three to five centimeters). All but three tattoos were located on the upper body and arms. The remaining three were on the legs and ankles. Respondents reported paying between USD 25 and 900 for all the tattoos they had.

4.1. Tattoos and Inner Life

The scholarship suggests that tattoos share some features with religious dynamics, like a time of pondering and discernment before making a decision, pain as an ascetic element, and a commitment to an ideal or experience that people want to remember and communicate (Morello 2021). We found in our sample similar dynamics. Sarah’s story illustrates them:

I went to a Jesuit [a religious group within the Catholic church] school for undergrad, (…) that is where I was first exposed to these things [social justice ideals] and I think I always knew I would make the leap into becoming a tattoo person (…) I’ve been playing around with this idea for a while (…) It was at this [meeting on social justice] that I was like “okay, no matter what happens in my life these are ideals that I would want to feel close to” (…) So I knew I wanted the, “In all Things.” My original plan was to have it on my arm and the weeks that I was thinking about it I would look at my arm (…) Ultimately, I decided to get it at my side at the very last minute (…) It was a weeknight, a Tuesday, and I decided I was going to do it (…) So I walked to the tattoo parlor (…) and [the tattooist] was like, okay we can do it right now. I was like [shocked noise] NO! I totally can’t. So, I put down the deposit, I think it was $100. I think I paid for the whole thing right there and we scheduled an appointment for the next week. I’m married (…) and I remember talking to my husband about it (…) The next week it was a weeknight, I wore a sweater and they played Motown music in the tattoo parlor and I remember I shazamed the song and I got on the table.(Sarah, Catholic, 29)

As was the case for Sarah, for many respondents, it took around a year or two to decide the subject (what the tattoo represented), the image (the design of the tattoo itself), and the body part on which the tattoo would be located. In our sample, one respondent mentioned thinking about it for as long as six years: Chelly (Catholic, 22) got a tattoo of an owl perched on a book that she got six months after her 18th birthday. She started to think about it when she was “like 11 or 12 years old, when my parents (…) were getting tattoos.”

As in Sarah’s story, many participants reported that the process of getting inked involved some back and forth; however, some reported that walking into the tattoo parlor was an unanticipated decision (Rebecca, Protestant, 21). Women also mentioned taking time selecting the tattoo parlor and the tattoo artist. Participants choose the tattoo parlor and artist for different reasons: a recommendation from someone who had already gotten a tattoo there (Chelly, Catholic, 22), reading reviews of the parlor (Rebecca, Protestant, 21), discounts offered (Esther, SDA, 19), picking an artist who was a “family friend” (Keke, agnostic, 19), or who shared the same ethnic background (Kenedi, Catholic, 22). In any case, the main point was to choose a place where they felt comfortable:

the first tattoo shop that I went to was very intimidating. So I was like, “I don’t really like that vibe” (…) I found her because the salon that I found was super chill, like a really good atmosphere, very clean, and then from there I looked at their artists and then I decided based on style.(Sarah, Jewish, 23)

Tattoos also involve penance, a common religious dynamic. Tattoos are painful; getting them hurts. Respondents knew this and were prepared to face the pain. Rowan (non-affiliated, 19) got a tattoo of a compass on her ankle (see Figure 1):

I actually feel like her [her mom] telling me how bad it was made it less painful for me because when I actually got it I was expecting this horrible, traumatic thing to happen and I just put a towel in my teeth and I was like look, it’s worth it and to be quite honest, I was going through a lot of emotional pain so physical pain didn’t seem as bad as what I was going through mentally. Again, I didn’t do it to hurt myself, it was more of like, I’m dealing with so much right now it’s like, what’s a tattoo at this point?(Rowan)

Figure 1.

Rowan’s compass tattoo on her right ankle.

As in the case of Rowan, some respondents mentioned that others prevented and prepared them for the pain they would experience. Someone told Jenny (Jewish, 23) that the “ribcage was difficult… That’s an understatement!” Kelly’s (Catholic, 18) brother told her that it was “like a cat scratching at a sunburn” and she completely agreed. However, for most of our respondents, the whole experience was positive (20 respondents had more than one tattoo). As Ana (non-affiliated, 18) put it, “It was a mix of being scared and adrenaline and pain, but it’s a very nice mix.” Again, as in the case of Rowan, some women mentioned that the stressful situation that was related to the meaning of their tattoo was more traumatic than the physical pain. As in many ascetic religious dynamics, the physical penance was a manifestation of a spiritual pain.

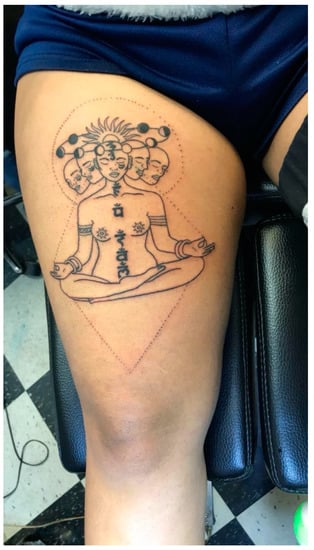

This ascetic feature of tattoos brings us to the next comparison with religious dynamics. What is the penance for? What is in the tattoo that makes the pain worthwhile? From the very beginning, we looked for individuals who had what they considered to be “meaningful” tattoos. During the online survey, we encouraged respondents to tell the story of their “significant” tattoos. To some extent, our data were biased toward tattoos that were not merely aesthetic. In this sense, it is not a surprise that respondents mentioned that they “wouldn’t get a tattoo just to get a tattoo. I would want it to have some sort of meaning for me” (Kelly, Catholic, 18). Participants defined themselves as “a meaning person” (Jenny, Jewish, 23), and as Keke, a 19-year-old Agnostic, explained, “if you want to put in on your body, it’s because there is a meaning” (See Figure 2). Tattoos in this sample were worthy because they expressed the women’s inner lives. According to Keke,

My higher power is a female with multiple heads on it. That is the most important one because it is my higher power, it’s the exact opposite of what everyone believes God to be. Mine is a female, multiple heads, she has tattoos on her body, which goes against the whole, “don’t alter your body in any way shape or form.(Keke)

Figure 2.

Keke’ goddess on her leg, facing outwards.

With her tattoo, Keke, who identified as Agnostic, is challenging the idea of divinity, a female, multi-headed, tattooed power (see Figure 2). Her commitment is religious, although with an alternative way of understanding religion. Her tattoo openly challenges the image of a male god, and since it is facing outwards, we can assume it is a statement that she wants to communicate to others, as a reverse corroboration of what Dougherty and Koch (2019) found.

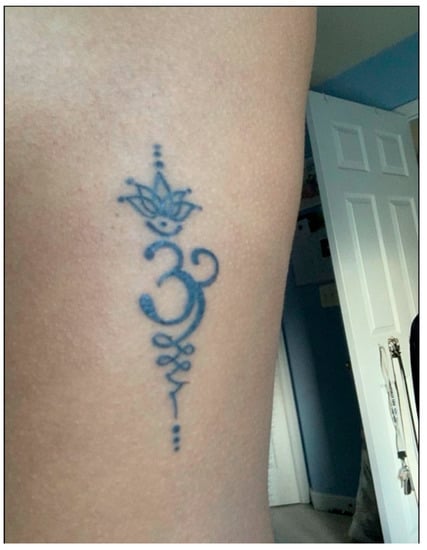

For other respondents, tattoos tell stories about important existential choices in their lives. For some, like Maia (Hindu, 19), tattoos are about religious and ethnic identity (see Figure 3). She got an

Om sign; my mom has an Om sign on her hip and we’re Hindu so that’s part of our religion and it’s (…) representative of peace and love in our religion and it means a lot (…) Every time I show someone it makes me proud to be Hindu, to be my religion, to be my ethnicity, to have that confidence to get a tattoo (…) I would say that it has not necessarily changed my perception of my religion but (…) I would say [it] has made me a stronger person.

Figure 3.

Maia’s Om tattoo, matching with her mother.

We have seen that, for Maia, adopting a Hindu sign has made her proud of her religion and ethnicity. Other participants also used their tattoos as a celebration of their ethnicity. Esther (SDA, 19) got hers to honor her Guatemalan heritage: “I am much closer to our Venezuelan side, and I personally just want to have that connection” with the other part of her family. She and her brother got matching tattoos depicting the bay laurel branches that are on the Guatemalan flag and coat of arms.

Rowan’s (non-affiliated, 19) compass tattoo is a sign of something steadfast (see Figure 1). She got it in the midst of a turbulent time in her life:

Unfortunately my parents got divorced and it was really chaotic for me and my life was changing all over again, I was going to college so I was like “I need something that is stable that I can just go back to, think about, and have with me,” and that was of course my metaphor of the compass, knowing that I can take different paths and be okay, I can open myself up to different ways of dealing with things so I put it on my right ankle because you want to put the “right” foot forward.

As we see in Rowan’s case, other respondents also got their tattoos as a sign or source of stability in the midst of what they perceived to be uncertain times. For Jenny (Jewish, 23), her tattoo was more about healing from “some kinds of events that happened in the past that weren’t ideal (…) I wanted to get [a] visual reminder to be a little bit nicer to myself.”

Four respondents mentioned getting a tattoo while abroad. For some, it was a memory of a holiday (Ana, non-affiliated, 18); for others, it marked an academic experience. The tattoo represented their learning: “It says, ‘Resilience’. I got that one when I was in Palestine after my trip that I went to recently. I really wanted something that would signify my trip and the Palestinian people as a whole and the one word that kept coming to mind the entire trip was ‘resilience’” (Kate, non-affiliated, 21).

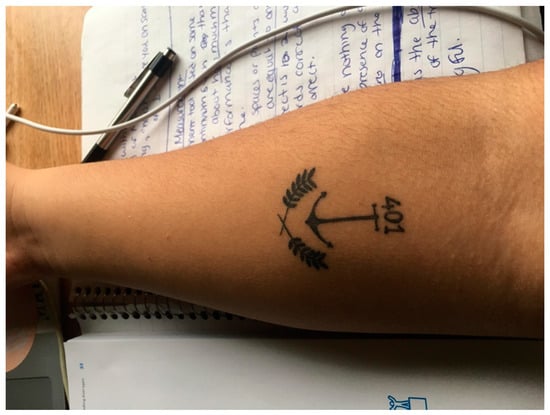

Tattoos might be used to express passage into adulthood, a way to build and project identity (Dann et al. 2016). Numerous respondents wanted to remember relations that shaped who they were, to preserve the link they had with significant persons, or to memorialize a conviction they had at some point in their lives. These were all experiences that were meaningful for them, but risked vanishing because of distance and time going by. Many respondents mentioned having matching tattoos with friends (Rebecca, Protestant, 21), cousins (Ana, non-affiliated, 18), siblings (Esther, Seventh-day Adventist, Kelly, Catholic, 18—see Figure 4; Esther, Seventh-day Adventist, 19—see Figure 5, and mothers (Keke, Agnostic, 19; Maia, Hindu, 19—see Figure 3; Kenedi, Catholic, 21; Chelly, Catholic, 22). Interestingly enough, among the male respondents in our sample, only one reported a “father–son” tattoo, and this with caveats: Steve (Catholic, 22) said, “My dad got a tattoo at the same time and he got a Celtic tattoo but it’s not the same thing or for the same reason. And his is different but we went in at the same time to get it.”

Figure 4.

Kelly’s tattoo, matching with her siblings.

Figure 5.

Esther’s tattoo, matching with her brother.

Summing up, tattoos involve a discernment process (about the experience of being inked, the image that would represent that experience, the part of the body, the artist), pain (not only necessary to get the tattoo, but also the tattoo as the materialization of a painful, challenging situation that is linked to the body art), and a spiritual commitment (a creative take on divinity, the adaptation of religious traditions, celebration of their ethnic background, re-signifying ordinary elements, memorializing meaningful relations). All these elements make tattoos embody manifestations of women’s inner lives.

4.2. The Others’ Gaze

When respondents were in the process of “discernment” about their tattoo, encouragement came mostly from their friends. Chelly (Catholic, 22) and Ana (non-affiliated, 19) got their designs from friends. Rebecca’s (Protestant, 21) first tattoo was a matching one with three other friends: “we thought about it for a long time, we played cards a lot with each other and we actually used a card game to determine who got each suite.”

College seems to be a favorable space that allows women to think about and get tattoos. Some academic opportunities triggered experiences that respondents wanted to memorialize by inking them onto their bodies. As mentioned, Emily (Catholic, 22) got hers while studying abroad in Ecuador, and Kate (non-affiliated, 21) got one as result of an academic trip to Israel and Palestine that was part of an upper-level class she took. College peer culture was also supportive and encouraging. Rebecca (Protestant, 21) got two of her tattoos in college, one of them during “Seniors Week”. She said she got news of the school closing down activities because of the COVID-19 pandemic (on Wednesday, 11 March 2020) so she and her roommate went to a tattoo parlor near campus (on Friday 13th) to get a matching “farewell” tattoo of a middle finger with a 13 on it. They got a tattoo that symbolized both their friendship and frustration.

Respondents reported encouragement and support from their families. Keke’s (Agnostic, 19) first tattoo was on her forearm and it was a matching one with her mother, who had it on her calf. Kenedi (Catholic, 21) got hers because of her mother. She mentioned that she was not thinking about getting a tattoo, but her mother did want a mother–daughter matching one, so they took some time and got “like something meaningful. So we love avocados (…) like how so you always split it in half and how it makes a cool piece, and my mom (…) she has the one with the pit, that symbolizes the belly.” Kenedi’s mother was her “only parent, and we’re always together” as one single avocado. Other cases reported support, even when parents did not get a tattoo. Chelly (Catholic, 22) went to the parlor with both her parents. Her father stayed in the waiting area, because “he was like ‘I’m happy that you’re doing what you want, but I can’t look at you crying’.”

Other participants mentioned parents’ opposition and hesitation about their decision to get a tattoo (see Figure 4):

So I got my tattoo when I was 16. So I’m the youngest of three. I have an older sister and an older brother. (…) They were home ‘cause they were in college for Christmas break and we’re just hanging out and randomly my brother was like, “What if we all got a sibling tattoo?” My parents immediately were like, “no, absolutely not.” Then, my brother’s like, “no, no, it would be cool” and my parents were like, “well Kelly is 16. She can’t get one.” And I was like, “but you guys can sign the paper, right?” (…) And then so she started sketching it out and I was like, “this is never going to happen” (…) Then showing that to my parents we were like, “all right, how are we going to make them allow me to get it”, (…) just to show my parents a little bit more what it meant to us. So when we showed them that literally on the same day, my dad was still like, “no”, but then I was like, “I’m paying for it. Like it’s my body. My siblings can’t get a tattoo without me, since it’s a sibling tattoo.” So that same day we ended up getting it but it was super last minute.(Kelly, Catholic, 18)

Respondents also mentioned partners’ involvement. While, for Jenny (Jewish, 23), it was a supportive participation (her husband got a matching tattoo with her), most women experienced certain pushback. Some were hesitant to engage their partners at all: “I remember talking to my husband about it, and remember feeling conflicted because he is part of everything I do, but also I wanted to make sure it was for me” (Sarah, Catholic, 29). Emily (Catholic, 22) mentioned that her boyfriend “was kind of upset about it because he didn’t like the fact I got it when I was abroad and I didn’t tell him before I did it.” Maia (Hindu, 19) also reported some resistance from her then boyfriend. Out of the six males whom we interviewed, none of them mentioned any engagement with their partners at all before getting their tattoos.

Participants negotiated their tattoos with their religious traditions in different ways. Some of them openly challenged the perceived banning on tattoos. Esther (Seventh-day Adventist, 19) got her tattoo (a matching one with her brother that celebrates their Latinx background; see Figure 5) with hesitation: “I live in a pretty strict household so it’s pretty against my parents and grandparents belief.” Kenedi (Catholic, 22) mentioned her inner struggle, “I’m like religious, it’s just not a thing I’m supposed to do”; however, she got it anyway. Although Esther and Kenedi mentioned that they were religiously active in their communities, neither mentioned any consultation with a religious authority.

Other respondents had easier experiences negotiating their tattoos with their religious heritage. Maia (Hindu, 19) found it easier to rely on her mother’s side of the family, who were “much more progressive Indian” than those on her father’s side, who were “much more strict Indian”. She chose the location of her tattoo carefully so that “when you wear Indian outfits, its’ cropped, all the tops are cropped and I did not want my dad’s side of the family to necessarily know that I had a tattoo, even though it is for religious reasons” (see Figure 3).

Kate (non-affiliated, 21) got hers when abroad in El Salvador, visiting her father. According to her, “tattoos over there are super forbidden because it’s a super Catholic place and tattoos are related back to the gang.” Religion contributed to the constraint, but was not responsible for all the hesitation. Central American gangs use tattoos as an identity marker that showcases one’s affiliation with the group. Kate was very careful not to get a tattoo that might associate her with the gangs.

While respondents were confident about their negotiation with their families, partners, and religious traditions, they were much more hesitant about the “corporate world” (Emily, Catholic, 22). Most of their concerns were about a visible tattoo jeopardizing possibilities in their future careers. Sarah (Catholic, 29) did not “want to be a tattoo person and have the stereotypes of tattoos arrest my potential to do the work that I do and I believe that my work is very good.” Chelly (Catholic, 22) wanted “to be a doctor so I wanted to put it in a spot where I knew I could keep it professional.” A professional future is a major constraint for women getting tattoos and a dealbreaker about what image to get and on which part of their bodies. All women reported having pondered on the possible impact of a tattoo on their careers. Emily (Catholic, 22) told us that she

wanted to put it in a place where I could cover it if I had the option. I didn’t want anything too obvious I suppose… I guess, kind of, for a job in the future. You know, so if I were interviewing or in the corporate world, just a place where I can hide it.

For some respondents, this concern was as painful as the physical distress of getting the tattoo. Rowan (non-affiliated, 19) explained that her father “was more concerned about the workplace environment like, ‘are you going to be treated differently for having a tattoo?’ And that was a thing that really bothered me a lot, more than even the pain actually.”

Most managed this concern about their tattoos being exposed by getting them on body parts that are usually concealed, like their ankle (Emily, Catholic, 22) or their ribcage: “I didn’t want anyone professional to see my tattoo, that’s another reason why I got it on the side. I was like, this will never come up in a job setting, no one will ever see this, no one has to see it if I don’t want them to.” (Maia, Hindu, 19) Many respondents set their boundaries on their hands, neck, and face, as did Keke (Agnostic, 19):

There’s definitely some jobs (…) I’m going to be a social worker so I’m working with kids so that’s something I’m really going to have to think about (…) Right now I have to be really careful especially with networking and college and stuff so I have to be really particular so right now I don’t have anything on my hands (…) I’m definitely not getting it on my face though, that’s a no (…) But yeah, you have to be very particular nowadays even though it’s getting more open minded, definitely, with the tattoo scene; but yeah you still have to be careful about that.

For other women, the strategy was to get a “family-friendly tattoo” that looked like a birthmark (Rebecca, Protestant, 22) or one that may trigger a conversation (Sarah, Catholic, 29). Others rationalized the constraint, mentioning that having control over when to show the tattoo and who could see it made it feel more intimate, “not a performative image but one that I hold really close to me” (Sarah, Catholic, 29). Kenedi (Catholic, 22) placed it under her bra strap because “it’s more like a thing for me.”

However, for Kenedi (Catholic, 22), a Latinx woman, there was another layer of complexity: “I think we just live in a society that as someone sees you have a tattoo, they assume things of you”. In her case, “already being Hispanic, I don’t need anything else added to me.” Kate (non-affiliated, 21) mentioned that getting hers in El Salvador (where her father’s family was from) made her very conscious about being able to cover it because tattoos were still associated with gang members.

We found that college appeared to be a favorable milieu for tattoos and that, in their households, respondents found both resistance and encouragement. Partners’ reactions were more conflictive. Women worried about them. When compared with male participants, women felt conflicted about sharing their decision of getting a tattoo with their partners. Male respondents did not report this conflict. The other’s gaze in the corporate world had no ambiguity. Women decided to conceal their tattoos to avoid unfavorable stereotypes, more so when respondents were of an ethnic minority.

5. Discussion

In line with Dann and Callaghan (2019), women in this sample embraced tattoos that had a purpose and were not mere decoration. Women expressed their religious beliefs and spiritual ties through their tattoos, even when the tattoo itself may not appear as a typical religious symbol. Women showed their spiritual commitment to ideals of social justice nurtured by a Catholic worldview, a sign of Hinduism shared with a mother, a carefully designed goddess that challenged the perceived established ideas of divinity.

Meaningful tattoos are a way for women to re-signify and reclaim their spiritual commitments in dialogue and tension with religious traditions. They do so with an important level of autonomy. While respondents spent, on average, between one and two years pondering their tattoos, no one mentioned any kind of conversation with a religious authority, even in the cases of explicitly religious tattoos or when respondents were active members of their religious communities. The participants who manifested a religious concern were worried about their household’s religious stance and their close religious communities. However, these women found enough freedom in the religious realm to decide what to reveal or hide, without care for the established authorities within the religious field.

In terms of lived religion, we found that women appropriate a cultural practice that is not confessional or traditional, to express their lived religious ideas. It can be a Catholic motto, a Hindu or Buddhist sign, a reformulated goddess, but the point is that the religious realm allows women some sort of negotiation. We hypothesize that this is the case because, in the U.S., women are more involved than men in religious practices (Pearce and Gilliand 2020). Even when women are underrepresented in leadership positions (Putnam and Campbell 2010), we speculate that their presence in the milieu challenges the male-dominated institutional gaze.

While no participant mentioned getting a tattoo after physical trauma, two (Rowan and Jenny) mentioned the tattoo as part of a spiritual healing process. The physical pain of the tattoo, its penitential dimension, became an external manifestation of what was going on in their inner lives.

Tattoos also show the impact of deep relations among women, relations that shape who they are. These tattoos represent mothers, grandmothers, siblings, cousins, friends. Even when some reported not being in touch with the represented persons, the tattoos reminded them of experiences they treasured.

Tattoos are related to ethnicity. Brown participants were much more aware of it than their White counterparts at the moment of making decisions about what design to get and on which body part the tattoo would be. In this sample, many respondents mentioned tattoos as marks in their path of growing awareness of their ethnicity and their roots, a way to celebrate it in their lives.

In spite of hook-up culture, which regulates women’s bodies in college culture, in this sample, we found that academic and peer culture at college creates a favorable atmosphere for women getting tattoos. Educational and spiritual experiences, and support from acquaintances, support the tattoos that women receive. In this particular case, a religious college provided a spiritual frame that allowed women to get one, due to encouragement from peers and reflections on learning experiences.

Matching tattoos, as well as tattoos representing other beloved persons, tell us that tattoos, as embodied and personal as they are, are not necessarily individualistic practices. When women receive matching tattoos, they often do so in order to solidify a specific bond that they have with another individual. Participants in this study reported a significant number of matching mother–daughter tattoos, which was not mentioned in the literature that we analyzed. Durkheim’s ([1915] 1965) understanding of tattoos as material emblems of “collective sentiments” might guide further research on mother–daughter matching tattoos and provide a way to explore current conceptions about maternity and daughterhood.

As was the case for Firmin et al. (2008), we found growing support from students’ homes. However, family and religious communities are mixed experiences. In this sample, we found both support and restrictions. We observed both encouragement and reluctance. However, we saw women negotiating their tattoos and affirming their autonomy and creativity at home and amidst their religious traditions. While women involved their partners in their tattoo decisions, men in this sample did not mention their partners. Further comparative research in this regard will be useful.

What we found was that the others’ gaze is still powerful in the economic realm. The workplace is perceived as a hostile space for women’s meaningful tattoos. While tattoos were once signs of risky professions (sailing, war, mining), today, they might be putting women’s professional careers at risk. There are employers that either do not allow tattoos or will ask employees to cover them. Even when tattoos may contribute to building women’s symbolic (spiritual) capital, in the workplace, they become a symbolic debt (Morello 2019b); tattoos (even spiritual ones) may jeopardize women’s ability to get a job.

Since these tattoos are the ones that say something about women’s inner lives, we can speculate that women are freer to express their spiritual convictions at home, in some religious spaces, and at college, but not in the workplace. As we saw, many respondents got their tattoos in the last years of high school or the early years of college, and were very intentional in placing them on a body part that they could easily conceal during their working hours. The perception of the institutionalized discipline of female bodies at the workplace implied a careful negotiation that started at early stages in the participants’ careers. Women perceive that the workplace is not open to this particular way of expressing their spiritual lives. Tattoos are in between the expression of their “authentic self,” their inner life, and constraint by a “communal position” in the workplace, where women do not want to risk their career opportunities (Dann and Callaghan 2019).

This is a descriptive study that has several limitations; the most important one is that participants were recruited in one institution on the East Coast, affiliated with the Catholic church. More diversity in terms of cultural regions and religious confessions will certainly bring more data and nuances about women’s inner lives as expressed in the tattoos they get. In this sample, participants’ expectations were about their professional careers. Respondents’ job prospects were either liberal professions (medicine, social worker) or the “corporate world” (banking, finance, consulting). Further research on women from different religious and socioeconomic backgrounds, and women working in non-corporate positions, will give us a more rounded view of the situation.

6. Conclusions

The religious field allows participants to exercise their autonomy, to challenge rules, and to produce and reproduce signs and meanings. They use tattoos to express their inner lives in their own ways, mixing religious and mundane signs. Tattoos are available cultural venues for women to express their spiritual, religious lives with creativity and autonomy from the expectations of their religious traditions. Tattoos tell us about women’s inner lives, convictions, and struggles, spaces of autonomy and creativity.

Women negotiated their meaningful tattoos with parents, boyfriends, and religious actors; they got support and encouragement from friends, siblings, spouses, and mothers; but they feared the corporate world. Women resisted the mandate imposed on their bodies by hiding their tattoos or selecting certain kinds of figures that would not jeopardize their professional potential. They still got tattoos, but they had less agency than in the religious realm. Career expectations, and not religious traditions, regulated women’s decisions about their tattoos.

Participants understood that religious people do not necessarily see tattoos as deviant. However, they assumed that the corporate world is not so tolerant. While college-educated women felt emancipated in terms of religion (they chose how to express their inner lives with autonomy and creativity), they felt that they were still regulated by their career opportunities. Respondents did not perceive the workplace as a space of freedom, perhaps because it is still a place where female bodies have not been retrieved from the oppressive gaze. Further studies might focus on female tattoos in the workplace to explore this issue in more detail.

In spite of these limitations, we found that tattoos are opportunities to both challenge social mandates and exercise autonomy and also socially regulated expressions. Participants expressed their interiority through their tattoos and found more freedom in the religious realm than in the corporate one. Even when women are not in positions of power, they have more agency in the religious field than in the “corporate world”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M.S., M.S., D.M. and A.E,; methodology, G.M.S., J.E.; formal analysis, G.M.S., M.S., D.M., J.E., A.E.; investigation, G.M.S., M.S., D.M., J.E., A.E.; data curation, J.E.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M.S., M.S., A.E.; writing—review and editing, G.M.S., M.S., D.M., J.E., A.E.; supervision, G.M.S.; funding acquisition, G.M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was founded by Boston College’s Undergraduate Research Fellowship program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Boston College (protocol code 20.110.01e; 26 November 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible through the support of the Undergraduate Research Fellowship program of Boston College’s Morrissey College of Art and Sciences. We are grateful for the help of Bianca López and Tarannum Rahman in collecting data for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Ammerman, Nancy. 2014. Sacred Stories, Spiritual Tribes. Finding Religion in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerman, Nancy. 2020. Rethinking Religion: Toward a Practice Approach. AJS 126: 6–51. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, Myrna L., Donna C. Owen, Alden E. Roberts, and Jerome R. Koch. 2002. College Tattoos: More Than Skin Deep. Dermatology Nursing 14: 317–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barras, Amélie, and Anne Saris. 2020. Gazing into the World of Tattoos: An Invitation to Reconsider how we Conceptualize Religious Practices. Studies in Religion, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Shannon. 1999. Tattooed: A Participant Observer’s Exploration of Meaning. Journal of American Culture 2: 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, Courtney, Wendy Cadge, Peggy Levitt, and David Smilde. 2013. Religion on the Edge. De-centering and Re-Centering Sociology of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, Charlotte, and Jane Callaghan. 2019. Meaning-making in women’s tattooed bodies. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, e12438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, Charlotte, Jane Callaghan, and Lisa Fellin. 2016. Tattooed female bodies: Considerations from the literature. Psychology of Women Section Review 18: 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- De Mello, Margo. 2000. Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of Modern Tattoo Community. Duke: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, Kevin, and Jerome Koch. 2019. Religious tattoos at one Christian university. Visual Studies 34: 311–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Emily. 1965. The Elementary forms of the Religious Life. New York: The Free Press. First published 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Edgell, Penny. 2012. A Cultural Sociology of Religion: New Directions. Annual Review of Sociology 38: 247–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmin, Michael, Luke M. Tse, Janna B. Foster, and Tammy L. Angelini. 2008. Christian Student Perceptions of Body Tattoos: A Qualitative Analysis. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 27: 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Galera, Cecilia, and Juan López Fidanza. 2012. Religiosidad popular en el siglo XXI: Transformaciones de la devoción a San La Muerte en Buenos Aires. Revista Estudios Cotidianos 1: 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Jessica. 2017. Centering Women of Color in the Discourse on Sexual Violence on College Campuses. In Intersections of Identity and Sexual Violence on Campus: Centering Minorized Students’ Experiences. Edited by J. Harris and C. Linder. Sterling: Stylus, pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- IPSOS. 2019. More Americans Have Tattoos Today than Seven Years Ago; Washington. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/more-americans-have-tattoos-today (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Koch, Jerome, and Alden Roberts. 2012. The Protestant Ethic and the Religious Tattoo. The Social Science Journal 49: 210–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, Ellen, Teresa Roach, and Sope Kahn. 2018. Navigating Campus Hookup Culture: LGBTQ Students and College Hookups. Sociological Forum 33: 1000–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leader, Karen. 2016. On the book of my body: Women, Power and “Tattoo Culture”. Feminist Formations 28: 174–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Estrada, A. 2020. Men, Tattoos, and Catholic Devotion in Brooklyn. Material Religion 16: 584–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Meredith. 2008. Lived Religion. Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Birgit, and Dick Houtman. 2012. Introduction: Material Religion-How things matter. In Religion and the Question of Materiality. New York: Fordham University Press, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Morello, Gustavo. 2019a. Why Study Religion from a Latin American Sociological Perspective? An Introduction. Religions 10: 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, Gustavo. 2019b. The Symbolic Efficacy of Pope Francis’ Religious Capital and the Agency of the Poor. Sociology 53: 1077–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, Gustavo. 2021. I’ve got you under my skin. Tattoos and religion in three Latin American cities. Social Compass 68: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, G., Catalina Romero, Hugo Rabbia, and Néstor Da Costa. 2017. Making sense of Latin America’s religious landscape. Critical Research on Religion 5: 308–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudé, Luzelle, Jacques Jordaan, and Luna Bergh. 2017. “My body is my journal, and my tattoos are my story”: South African Psychology Students’ Reflections on Tattoo Practices. Current Psychology 38: 177–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Lisa, and laire Chipman Gilliland. 2020. Religion in America. Oakland: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petkoff, Peter. 2018. Christian Tattoos As a Normative Demarcation of Memory, Defiance and Eternal Return. In Perplexed Religion. Edited by M. Díez Bosch, A. Melloni and J. L. Micó Sanz. Barcelona: Blanquerna Observatory, pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert, and David Campbell. 2010. American Grace. How Religion Divides and Unite Us. Ney York and London: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbia, Hugo, Gustavo Morello, Néstor Da Costa, and Catalina Romero. 2019. La Religión Como Experiencia Cotidiana: Creencias, Prácticas y Narrativas Espirituales en Sudamérica. Córodoba, Lima and Montevideo: EDUCC, Fondo Editorial PUCP, UCU. [Google Scholar]

- Reid-de Jong, Victoria, and Anne Bruce. 2020. Mastectomy tattoos: An emerging alternative for reclaiming self. Nursing Forum 55: 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, Anel Victoria, and Renée De la Torre. 2020. Altares vemos, significados no sabemos: Sustento material de la religiosidad vivida. Encartes 3: 206–26. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, Eric, Stacy Rogers Silver, Sonja Siennick, and George Farkas. 2011. Bodily Signs of Academic Success: An Empirical Examination of Tattoos and Grooming. Social Problems 58: 538–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, Jennifer Patrice. 2018. It Represents Me: Tattooing Mixed-Race Identity. Sociological Spectrum 38: 243–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, Lisa. 2017. American Hookup: The New Culture of Sex on Campus. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Walzer Moskovic, Alejandra. 2015. Tatuaje y significado: En torno al tatuaje contemporáneo. Revista de Humanidades 24: 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Williams, Roman. 2015. Visual Sociology and the Sociology of Religion. In Seeing Religion. Edited by R. Williams. London: Routledge, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).