2. The hijab in the West

An important body of qualitative research, which can be called “herméneutique du voile” (

Pelletier 2005), investigates the significance and agency that women who wear the

hijab ascribe to the garment. Studies using focus groups or interviews in Great Britain and North America reveal that the

hijab works as a means to achieve empowerment, respectability or modesty; to perform and confirm identity; to represent a political strand such as anti-colonialism; or even to negotiate spaces (

Haddad 2007;

Hopkins and Greenwood 2013;

Ruby 2006;

Siraj 2011;

Tarlo 2007). Other authors have tried to create typologies of the

hijab according to what motivates women to wear it (

Gaspard and Khosrokhavar 1995). A consensus has emerged from this literature: namely, the polysemy of the

hijab across all national contexts.

Another category of research shifts the perspective and examines the perceptions and attitudes of the majority society with regard to the

hijab, with these perceptions and attitudes being either expressed on the individual level or translated into national policies and media representations. Social psychologists have demonstrated that different individual and collective variables predict anti-

hijab attitudes (

Fasel et al. 2013;

Saroglou et al. 2009). More generally,

Helbling (

2014) has demonstrated that majority attitudes are more negative towards

hijabis than towards Muslims in general. Other scholars have argued that hostility towards veiled women is the gendered aspect of Islamophobia, and that it can be explained by stereotypes linked to the post-9/11 context (

Amiraux 2007;

Chakraborti and Zempi 2012) or to a particular conception of laicity in which the

hijab is constructed as a threat to the latter and to republican values such as gender equality (

Benelli et al. 2006).

Finally, relatively recent studies have started to look specifically at the practical consequences of wearing the

hijab in such socio-political contexts. This has been done mainly by investigating the economic impact of wearing the

hijab, which could be called the “

hijab penalty” just like authors reveal the existence of the “Muslim penalty” in other studies (

Khattab and Modood 2015): studies have shown through statistical analyses or field experiments that veiled women are significantly less likely to be employed than non-veiled women and non-Muslims (

Unkelbach et al. 2010), and have a significantly lower chance of being offered a job than similar applicants without the

hijab (

Ghumman and Ryan 2013;

Weichselbaumer 2020). Very few studies have examined other life domains, however.

Zempi and Chakraborti (

2015) show that hostility towards veiled women has negative consequences in individual, community, and societal terms. Drawing on the testimonies of victims of discrimination in the United Kingdom,

Carr (

2016) and

Allen (

2020) offer detailed investigations of the experience of discrimination for Muslim women who wear the

hijab, especially in the form of street-level attacks and minor incidents. As for the American context, a qualitative study has shown how the

hijab plays a prominent role in processes of racialization in Dallas and Chicago (

Selod 2015), while a quantitative study has found that the

hijab is the most important predictor of perceived discrimination among Muslim women (

Dana et al. 2019).

These studies make important contributions to understanding the impact of wearing the hijab in Western countries in specific life domains. However, they focus on street-level incidents, and usually limit their analysis to one life domain or one area. Drawing on different types of field experts who have heard and collected numerous testimonies allows us to widen the analysis to include a variety of life domains at a national scale.

3. The Swiss Context

Switzerland has a sizeable Muslim minority, amounting to 5.3% of the resident population; of these, approximately one-third have Swiss citizenship, and most have a migration background.

2Moreover, the headscarf controversy has animated public and political debate since 1997, when the federal court banned a schoolteacher from wearing the

hijab, a decision supported by the ECHR (Dahlab vs. Switzerland case). Conversely, attempts to ban schoolgirls from wearing the

hijab have often been discussed by the media, but have never succeeded legally (

Angst et al. 2006, p. 8). These debates take varying forms and intensity, depending on the regulation of religion and the extent to which laicity is or is not applied in each canton, Switzerland being a federal State (

Ossipow 2003). Scholars have also demonstrated how the “veil” is used in Swiss media as a symbol of radical Islamism, oppression of women (echoing a process of attribution of extraordinary sexism to the Other described by

Roux et al. 2007), or incompatibility with democratic values (

Parini et al. 2012).

Finally, after adhering to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination in 1971, Switzerland adopted a legal provision against racial discrimination, commonly known as the “anti-racism law”, including discrimination based on religion, in 1995 (Art. 261bis of Criminal Code): anyone who publicly discriminates or incites hatred against individuals because of their racial, ethnic or religious affiliation or sexual orientation shall be punished by up to three years of incarceration or by a fine.

3 Victims of discrimination can file a complaint that will automatically launch legal proceedings.

This enactment gave birth to a network of government-funded centers supporting victims of discrimination. It is partly individuals who work in these centers that I have interviewed for this paper. Since 1995, out of 935 procedures filed as part of the “anti-racism law” and compiled by the Federal Commission against Racism,

4 52 involved Muslims. Out of these 52 cases, only 2 concern direct discrimination against women wearing the

hijab, both in 2010 (one was insulted and the other got her

hijab torn off, both in the street), and 2 others were linked to communications inciting hatred and violence against women wearing the

hijab. The small number of legal cases involving direct victims might suggest that

hijabis very rarely report experiences of discrimination, which will be discussed in the analysis.

To sum up, Switzerland is quite similar to other European countries, although the level of structural discrimination is somewhat higher due to its system of direct democracy.

6. Results

6.1. The hijab as the Most Important Marker of Muslimness

Drawing on the multitude of testimonies given by individuals who had experienced discrimination, both the governmental and the non-governmental experts discussed the importance of this garment and the role that it plays in processes of discrimination. Analyzing the interviews reveals that the hijab is seen as the most important marker of Muslimness, which makes hijabis especially vulnerable to discrimination.

For example, one non-governmental expert claims:

“But the only negative point in this system are not Muslims; it is the Muslim woman. Muslims, I don’t know, there are prejudices sometimes in the workplace or hiring process. There are some stories linked to eating halal, etc. But the discrimination that is clear is against Muslim women, especially the veiled woman. This is really, this is the thing that sticks out the most”.

(N03)

Similarly, some of the other experts indicate that hijabis are the most vulnerable Muslims when it comes to discrimination. They mention that cases of discrimination reported to them “concern all veiled women” (N06), that they are “more affected” (G09), and that “women with the headscarf have the most difficulty, I think, without a doubt” (G07). Both the governmental and the non-governmental experts share this perception.

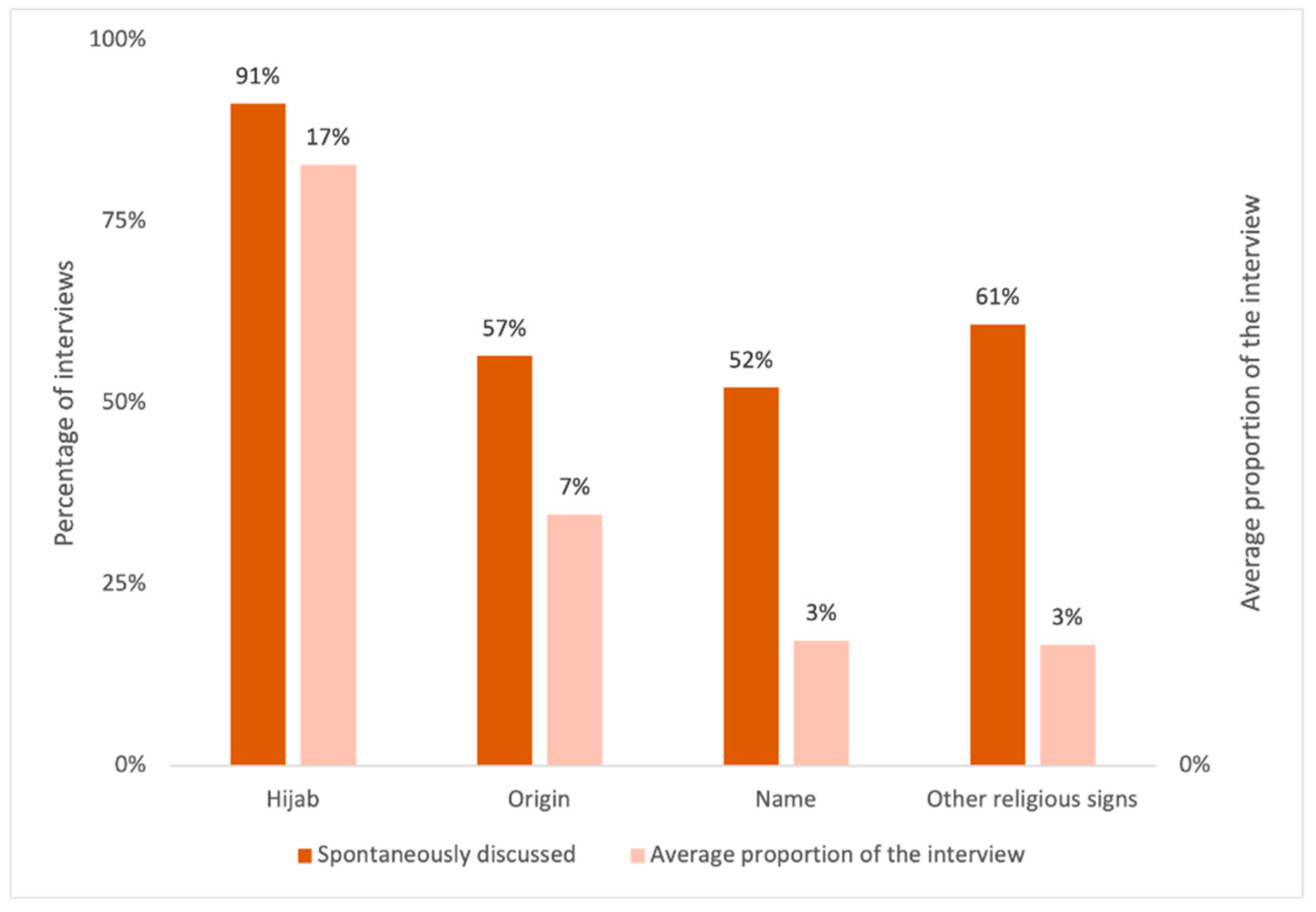

In this regard, it is interesting to note that the

hijab is a very salient topic when the experts discuss different markers of Muslimness. As

Figure 1 shows, the experts mention the

hijab spontaneously more often than other markers (left axis), as they bring up the issue themselves in 21 of the 23 interviews (91%). In contrast, they spontaneously mention other markers of Muslimness (right axis), such as name, origin, or signs seen as religiously motivated (Ramadan, beard, special diet), in only 12 (52%), 13 (57%), and 14 (61%) interviews.

Figure 1 also indicates that, in terms of the extent to which each marker is discussed, the

hijab is given more attention than other markers. On average, the

hijab takes up 17% of an interview, with a maximum of 40% and a minimum of 2%. Comparing these results to other markers (7% for origin, for example) shows clearly the prominence of the

hijab in the expert interviews.

Additionally, the hijab appears at a very early stage in the interview, with the issue cropping up after less than 13 min on average; it sometimes crops up in the first three minutes of the interview, and almost always within the first 20 min. However, the governmental experts were slower to mention the issue (17.4 versus 9.8 min on average).

6.2. Why hijabis Are Targeted: Visibility, Gender, and Racialization

In line with Goffman’s theory of “discredited stigma” (visible marker of otherness) and intersectional approaches, most of the experts explain that the vulnerability of hijabis is due to three main mechanisms: (a) the hijab makes their belonging to Islam directly visible; (b) gender and religious belonging intersect in the experiences of discrimination; (c) hijabis are racialized as they are often (wrongly) perceived as foreigners. These mechanisms are highlighted by both types of expert.

(a) According to the experts and in line with previous studies, the hijab “makes things a lot worse, because it is very visible” (N01, G09). As an illustration, one expert explains the difference between men and women as follows:

“With women it is more difficult; in most cases it is obvious that they are Muslims. For men, a beard is not sufficient anymore, unless you really wear religious clothes, but no one wears such clothes for a job interview. So, with men, other things cause problems like surname or first name. Or in a job interview when you say something. Or at work, you’re bullied by your colleagues, you hear certain stories or those bad jokes about Islam, about Muslims, but often also the countries of origin [are involved] like Turkey, Kosovo… With women it’s different, especially when they wear headscarves it’s obvious. She doesn’t have to say anything, she’s just … Her clothes speak”.

(N09)

(b) Additionally, the experts highlight how gender and religious belonging intersect in processes of discrimination. Apart from the obvious fact that the hijab is only worn by women, those women who do wear the hijab can be exposed to sexist comments in the public space. Examples were given of women who had been asked in public about why they hid their hair despite being “so beautiful”, and about their supposed difficulty in dating men (N07), as well as of sexist insults thrown at hijabis by strangers in the street and by neighbors.

The experts gave other examples of hijabis facing verbal attacks with regard to their maternal role, such as being told that what they are “doing with the veil is unacceptable, your child will suffer all his life because of your choice. Are you thinking about your child? Are you thinking about the suffering you’re causing him?” (N05). Other experts explain that, “when hijabis take a walk, some women even talk to the kids, telling them, ‘your mother with her headscarf …’” (N07); that hijabis are intentionally kicked on the bus when they are looking for something in the stroller (N05), or physically assaulted by a man trying to pull the hijab off (N09).

All these examples reveal how the injunctions made to women in different gender roles attributed to them by society are added to the prejudices and stereotypes linked to the wearing of the hijab.

(c) Finally, the experts highlighted how hijabis are racialized through xenophobic comments, as women wearing the hijab are often wrongly perceived as foreigners and attacked for this reason. They report situations where the victim is reduced to her (supposed) “foreign” identity. This can take different forms, such as direct insults or attributions of “otherness”, for example “go back home” (N02, N06, N07, N10, G02) or “dirty Arab” (N07); the implication that the world is divided between “us” and “you”, such as “in our country you can’t do this” (N07); and more subtle insinuations, such as being surprised that the woman speaks the local language, when she is asked, “Do you understand French?” (N04, N07, N14). The experts often highlighted the fact that these incidents had occurred with regard to Swiss citizens or second-generation individuals born in the country.

This process can be called “double-othering” (

Allen 2020), as women wearing the

hijab are attacked because they are Muslims

and because they are conceived as being “other” or as not belonging to the country.

To sum up these results, the experts explain that hijabis are especially targeted by pointing to the fact that they are more visible as Muslims, and that hijabis experience multiple discrimination where gender, belonging to Islam and (supposed) foreign origins intersect.

6.3. Pervasive and Multifaceted Discrimination

In addition to their specific vulnerability, another important dimension of discrimination against hijabis highlighted by experts is its pervasiveness: it (a) occurs in a variety of life domains, (b) takes different forms, and (c) affects a wide range of socio-demographic profiles.

(a) First, the experts interviewed identify different life domains where such discrimination occurs, especially the labor market, public spaces, and state schools.

As for the labor market, there seems to be a double glass ceiling for women wearing the hijab, as they find it almost impossible to access the labor market (G09) despite a good, and sometimes very good, level of education. The experts often highlight the fact that “there are veiled women who are hyper qualified, women who have a PhD in medicine, but who are housewives. With a master’s degree, a PhD, in educational sciences, journalists, teachers, there are a lot” (N03).

For example, they explain that students are unable to find internships in law or pharmacy (N02, N06, N11, N04), that women are fired as soon as they decide to wear the hijab at work (N03, G04), or are faced with the choice of either removing the hijab or quitting their job (N06, N07, G07), and that they have been refused a position explicitly or implicitly because of the hijab (N05, N07, N09, G08). Especially affected are the medical sector, teaching, jobs involving direct contact with customers, work in cantonal administrative offices, and universities.

As for public spaces, the experts talk about discrimination in different public situations, such as insults or physical assaults in the street (N02, G03, N04, N06, G07, N10, G09), in supermarkets (N07, N10), at the airport (N01, N04) where women are forced to remove the hijab in front of other passengers, at the post office or bank (N02, N04), on public transport (G02, N05, N08, N09), and in car parks (N07):

“Otherwise, most of the problems that arise are in car parks. Or at the till in shops. Or on the street. Sometimes it means looks, insults. Insults saying “go home”, things like that. That’s the majority of it, it’s in the street. Someone who says something quickly and leaves”.

(N07)

As well as the labor market and public spaces, schools, although mentioned less often, are no exception to the rule. Situations range from harassment by other children to degrading treatment by teachers. For example, one of the experts relates the testimony of a mother whose daughter had put her hijab back on after school and then bumped into her teacher on the street. Expressing her negative view of this practice, the teacher then completely changed her attitude towards the girl in class for the worse (N07).

Other examples are that girls who wore the hijab at school ended up taking it off (although legislation does not prohibit pupils from wearing it in Switzerland), or asked to change colleges because of harassment: “There was no way to talk to the teachers, it was always like closed doors. They (the schoolgirls) felt demeaned. They were losing their self-esteem” (N04).

(b) The variety of forms taken by discrimination is also important. Indeed, the incidents can range from verbal to physical attacks, be implicit or explicit discrimination, or take the form of practices of exclusion. The experts most often report practices of exclusion such as bullying or withholding a service (61.9%) and verbal abuse (31.0%), but physical assaults (7.1%) are not exceptional, with examples of women being spat at (N04), jostled and hit (N05, N09, N07), and having their hijab torn off (N06).

(c) Finally, the examples described by the experts show that the experience of discrimination affects all socio-demographic profiles, be they Swiss citizens or asylum seekers, born in Switzerland or abroad, with a high level of education or from poorer socio-economic backgrounds. One of the experts explains, for example, that no matter the status, exclusion from the labor market is commonplace: “Can you imagine, 200 rejections! … Just for an initial internship. They don’t succeed. It’s not easy, even though they were born here, they are Swiss, they are naturalised. But, in spite of that, they are marginalised, they are excluded from the system. They feel like second-class citizens” (N03). The analysis of discrimination in schools or kindergartens also points to the fact that the women affected by discrimination are of widely different ages.

In other words, the experts describe the discrimination faced by hijabis as pervasive, since it affects a wide range of life domains; multifaceted, since it takes a variety of forms; and it affects a wide range of socio-demographic profiles.

6.4. A Segregated Social Space

Analyzing the expert interviews also allows us to identify three kinds of space for

hijabis that are similar to the “out-of-bounds, civil and back places” coined by

Goffman (

1963).

First, the labor market is a quasi “out-of-bounds place”, as it appears to be almost forbidden for women wearing the hijab in Switzerland, in a variety of sectors. Several of the experts explain that “it is almost inaccessible for a woman who introduces herself veiled in a job interview”, be it in industry, in more social-oriented jobs (G09), or in local administration (N13, N05). The exclusion of hijabis can be formulated either explicitly or implicitly: the experts signal that many companies explicitly state that they “do not want to hire women who wear the hijab” (N11), and make a condition of employment the removal of the garment (N02, N03, N05, N10), or develop written guidelines to prohibit the wearing of “headgear” in the workplace (N02, N03, N11). The usual argument highlighted by the experts is that, if confronted with someone wearing the hijab, customers or patients could be “shocked” or “disturbed” (N02, N03, G07, N10). In some implicit situations, hijabis point to different clues as evidence of their lack of success in the process of applying for a job, such as repeated rejections, a sense of discomfort during the interview, and a sudden change of tone. To some of the experts, the only solution seems to be to remove the hijab, which some government workers at regional employment offices seem to encourage (N04, N09):

“And yes, there are many of them. To tell you the truth, there are quite a few who actually take off the veil. Because they were unemployed for years, devalued... And it’s true that at some point—for a matter of survival, too, for socio-economic reasons, they had to take the step, and I think that’s the case for many women”.

(N05)

Second, public space and state education could be described as “civil places”, where stigmatized individuals are treated as though they were not officially disqualified when in fact they are. Indeed, although Swiss legislation does not prohibit women from wearing the hijab in public spaces, or pupils wearing the hijab at school, the experts claim that practices of exclusion and stigmatization do in fact target women wearing the hijab in such places. In public spaces, this can range from verbal and physical aggression, to unfriendly looks that are sometimes difficult to decipher: “maybe you can say that’s not discrimination or that’s just a look. … when you stare at people, that would probably bother others as well” (N10). The frequency of such incidents depends on what is currently happening in the international context, as the incidents appear to increase immediately after a terrorist attack (N02, G03).

Examples at school also highlight how certain spaces are officially inclusive but are nonetheless sites where stigmatization is still at work: a teacher repeatedly calling a schoolgirl “scarf” instead of her name; a school head criticizing the parents for allowing a pupil to wear the hijab after returning from the holidays; girls forced to take off the hijab when photographed for their pupil ID card. Some schools, especially in cantons where laicity has become the subject of heated political debates, are known to be more problematic:

“And this school, unfortunately, is not the only one. I can easily think of a dozen girls who went to that school and really suffered. Girls who were veiled and ended up removing their veil, so much pressure”.

(N04)

Indeed, this could be explained by political contexts at the cantonal level. The federal nature of Switzerland implies important variations in the way laicity is (not) applied. For example, the new

Law on the laicity of the State (A 2 75) came into force in 2019 in the canton of Geneva, prohibiting the wearing of “ostentatious religious signs” for state employees, which is symptomatic of an especially tense context surrounding the “veil”. “The proximity of Geneva to France entails similarities in its political debates and understanding of laicity, namely in terms of invisibility of religious belonging and practices in the public sphere. As Amiraux points out, the

hijab is situated between the private and public spheres, and is often presented in public debates as a threat to laicity (

Amiraux 2007). Several experts, government as well as non-government ones, highlight a particularly hostile context towards

hijabis in Geneva (N03, N05, G07) and explain it by two main factors: a conception of laicity that is exclusive, contrary to Neuchâtel where it is inclusive (N02, N05, N08), and its proximity to France (N02, N04, N05, G02).

Finally, social exclusion, be it explicit or implicit, official or unofficial, leads hijabis to invest in “back spaces”, where they can navigate without experiencing discrimination or having to conceal their “social stigma”, with different experts often mentioning such spaces as being the household, low-skilled jobs, and voluntary work in Muslim organizations. For example, highly qualified women such as lawyers, legal experts, doctors, who unwillingly end up doing cleaning work (N02, N07), being full-time mothers (N03), or doing voluntary work (N05).

The interviews suggest that discrimination shapes the social world in three kinds of places for hijabis, although the boundaries between the places are not as clear-cut as Goffman’s theory might suggest: except for some low-skilled jobs and for businesses owned by Muslims, the labor market can be seen as an “out-of-bounds place” for women when they expose their religious affiliation through the hijab; public space and education can be seen as “civil places”, since officially they are inclusive, but unofficially exclusive in day-to-day experience; and voluntary work in Muslim organizations, low-skilled positions, and being a housewife are close to “back places”, where these women, by force of circumstance, can navigate these spaces without having to conceal their social stigma.

6.5. To Report or Not to Report?

With one exception, the governmental and the non-governmental experts provide broadly similar insights into the prevalence, nature and effects of discrimination against hijabis: namely, the non-governmental experts have a better understanding of the phenomenon whereby hijabis under-report to state services. The governmental experts are usually aware that just a minority of victims of discrimination report to their services and provide explanations (albeit at a general level) as to why that might be the case. For example, one of the experts enumerates possible reasons why victims of discrimination do not report to them: unawareness, fear and shame:

“So sometimes people don’t even know we exist; I think about people with a precarious status, people who have just arrived in Switzerland. Another reason is the fact that they are afraid to report because they fear possible repercussions for their illegal or precarious status in the country. Sometimes they are ashamed to talk about certain episodes with someone they don’t know well and there is also the fear of not being perceived as integrated. For people who have been here for a long time, recognizing that they are victims of discrimination represents a personal defeat”.

(G09)

In contrast, the non-governmental experts provide specific explanations as to why hijabis in particular do not report to state services, these explanations falling into three main categories: a sense of fatalism, the fear of being blamed, and the complexity of legal procedures.

As to the first category, the non-governmental experts explain that, if many hijabis do not report their experiences, it is because “some of them think that there is no point in talking. Even if she speaks, she won’t get anything. That’s a very strong reason” (N06). Others point to the attitude of resignation among hijabis with regard to discriminatory practices in the labor market, where women “know that they did not obtain a position because of the headscarf; they know and say, ‘alright, I accept it, I move on’” (N09).

As to the fear of being blamed, the non-governmental experts suggest that reporting discrimination that is linked to the hijab may involve a double stigmatization, with the person to whom the incident is reported judging the victim negatively for wearing the hijab. For example, one of the experts says that victims fear reporting discrimination because this might backfire on her (N04), and another says:

“I understand these women who don’t go because they are immediately told, ‘yes, you know, in our country, you shouldn’t wear …’ We make them feel guilty. Not only do we judge them; we also make them feel guilty, ‘it’s your fault, you’re dressed like that, well that’s what happens’”.

(N07)

These past experiences or concerns would explain why hijabis are sometimes reluctant to contact state services and would rather turn to Muslim associations comprised of Muslim peers who would better understand them. As one of the experts suggests: “So I come back to the reason why they come to us, because we don’t judge them, maybe we understand them because we have also experienced it”.

Finally, the non-governmental experts mention the fact that the complaint mechanisms and legal procedures are complicated. Indeed, if a victim of racism wants to defend his or her rights within the legal framework of provisions against racial discrimination, a framework that includes discrimination based on religion (Art. 261bis of the Swiss Criminal Code), then different criteria must be met, one of which is that there are witnesses to the racist incident and that the incident took place publicly. Both the governmental and the non-governmental experts highlight the difficulty here when talking about racist discrimination in general (G02, G05, G06, N09, N11): “most of the time, the case is closed. Word against word, lack of conclusive evidence, no witnesses, that’s it, the perpetrator can tell barefaced lies and that’s the end of it. And it’s a double punishment for the victims, so it’s a pretty traumatic process” (G02).

This means that

hijabis tend to be reluctant when it comes to contacting a state-funded center for help in criminal procedures; they regard a positive outcome as being unlikely. This could certainly explain the very low number of legal cases involving

hijabis recorded in the database presented in

Section 3: two cases of direct discrimination against

hijabis, concentrated in the year 2010, out of a total of 52 cases where the victims are Muslims since 1995. For example, one non-governmental expert describes the situation in these terms:

“After years of working in this company without any problems, she decided to wear a headscarf, and then this became a reason for her dismissal. Often it is clearly said, but not recorded, and that is not racial discrimination, according to criminal law, because this is a private relationship and there is no evidence, or no witnesses. Then maybe they can sue for defamation, but that will cost money”.

(N09)

Some of the experts also report that the police sometimes constitute another obstacle for hijabis when they wish to file a complaint, because the police either do not take the case seriously (N10), or immediately claim that there were no witnesses (N09).

In short, while the governmental experts have a general idea of why many victims of discrimination do not report to official centers, the non-governmental experts provide more detailed and specific reasons why that is the case, the three reasons that they mention being a fatalist attitude towards the situation, the fear of being blamed instead of supported, and the obstacles to initiating legal procedures.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, I set out to answer the question: how do governmental and non-governmental experts describe the discrimination experienced by hijabis in Switzerland? More specifically, I sought to (1) determine the importance and role of this “marker of Muslimness” that field experts discern in processes of discrimination; (2) identify the forms that discrimination takes, and the life domains and socio-demographic profiles affected; (3) understand the particular way that this discrimination configures the social space that hijabis navigate; and (4) reveal how governmental and non-governmental experts differ in their knowledge.

We can provide four answers to these questions. First, both the governmental and the non-governmental experts state that the hijab is the most important marker of Muslimness in processes of discrimination, which makes hijabis especially vulnerable to discrimination. The experts explain the specific vulnerability of hijabis by pointing to the fact that their affiliation to Islam is visible (like the discredited stigma described by Goffman); to the way that gender and religious belonging intersect in the experiences of discrimination; and to the processes of racialization and othering based on the (often false) perception as foreigners.

Second, the experts describe this discrimination as being widespread and multifaceted, since it occurs in a variety of life domains, takes various forms, and affects a wide range of socio-demographic profiles.

Third, the expert interviews suggest that the social world is configured around three kinds of places for hijabis (also highlighted by Goffman): the out-of-bounds places, such as the labor market, where the hijab is very rarely tolerated; the civil places, which are officially inclusive but actually marked by exclusion in day-to-day experiences, such as schools and public spaces; and, finally, back-places, which hijabis can navigate freely, mostly through voluntary work in Muslim organizations, in low-skilled positions, and in the household.

Fourth, the governmental and non-governmental experts converge with regard to the prevalence, nature, and effects of discrimination against hijabis. However, the non-governmental experts show a better understanding of the phenomenon of under-reporting, explaining the reluctance of hijabis to report their experiences to state services by pointing to their sense of fatalism, their fear of being blamed rather than supported, and the complexity of criminal procedures.

These results have several implications with regard to the current state of research and to recent events. For one thing, many studies that measure discrimination against Muslims show no significant difference between Muslim men and women. For example, they face unemployment in the same extent (

Connor and Koenig 2015;

Heath and Martin 2013;

Lindemann and Stolz 2018) and do not significantly differ in their perception of discriminations (

Lindemann and Stolz 2020). However, my results point to the specific difficulties faced by Muslim women who wear the

hijab. These difficulties do not appear in statistical analyses, either because such women constitute a minority of the Muslim population, or because they are under-represented in surveys. My study also suggests that existing field studies that rely on controlled situations and focus on specific life domains have not yet captured the pervasiveness and importance of discrimination against veiled women, welcoming further qualitative studies or new surveys that include items on veiling practices.

For another, passionate debates have broken out in the public and academic spheres regarding scientific research on minorities, debates that have culminated in the accusation of Islam-leftism levelled at social scientists working in these fields, especially in the French context (

Fassin 2021). At the same time, laws are being passed that ban different veiling practices in the public space in Europe, the latest being the banning of full-face veils in Switzerland, which was voted for in March 2021. During the campaign, it was not unusual to notice a quick slip from the niqab (full-face veil) to the

hijab in TV and radio debates. In such a context, there is still a clear need for dispassionate and serious empirical research to document and understand social injustices scientifically.