3.1. Analysis of the Covenant’s Text

The covenant is not lengthy, as one would expect of a religiously or lawfully binding contract. This could have been due in part to the nature of written documents at the time (there was a scarcity of writing materials and of those who could write) and the mostly oral tradition of the Arabs. Despite its apparent simplicity, we find a weighty promise: the protection of God and God’s Messenger on land and at sea. Here, the self-same protection that a Muslim would hope to receive by believing in and obeying God and His Prophet is accorded to Christians for a small yearly tax. As other covenants with Christians indicate, the yearly tax that was usually prescribed was far from being exorbitant or burdensome, and it was usually commensurate with the size of the community: it would amount to something like one dinar per person, or one bushel of wheat per household, for example.

The following text is from Prophet Muḥammad’s covenant with the Christians of Maqna: “They are under the protection of God and Muḥammad. They must give a quarter of their textiles and a quarter of their fruit” (

Al-Wāqidī 2004, vol. 3, p. 1032). Here is another excerpt from a covenant of his with the Christians of Adruh: “This is a peace treaty from the Prophet Muḥammad with the people of Adhruh. They are under the protection of God and Muḥammad. They must pay one-hundred dinars, a fair sum, every Rajab. They guarantee in the name of God that they will be loyal and kind to the Muslims”, as well as to Muslims who turn to them for shelter (

Ibn Kathīr 1990, vol. 4, p. 30).

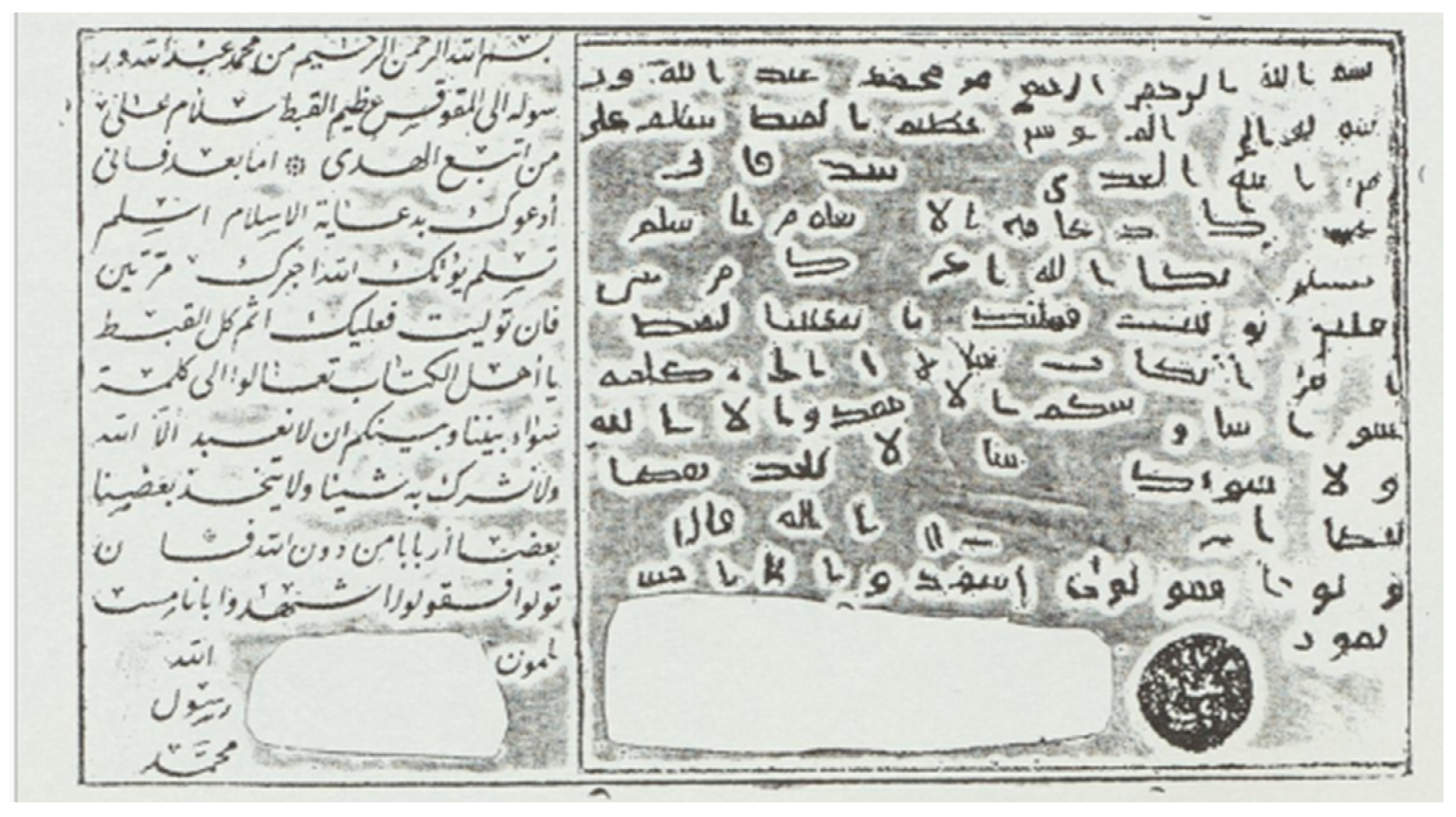

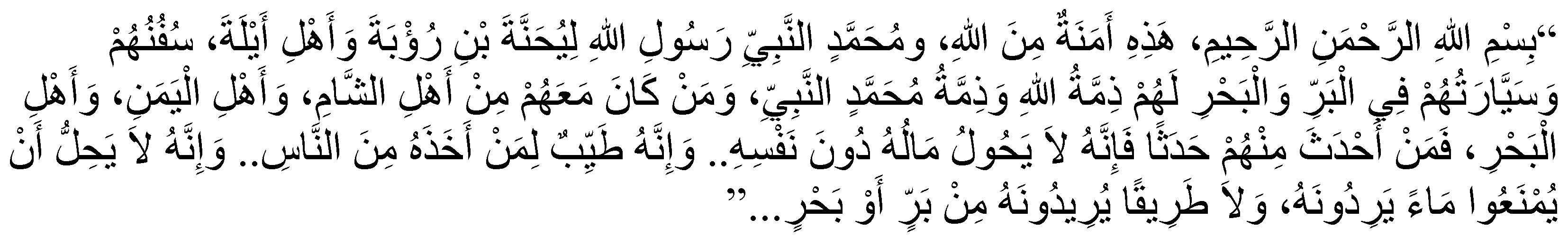

It should be noted that the translations provided above are my own, and I felt it necessary to translate them myself, as opposed to using an established translation, such as Guillaume’s, because of certain phrases I felt were mistranslated. For comparison, the following is Guillaume’s translation of the main covenant in question:

“In the name of God, the Compassionate and Merciful. This is a guarantee from God and Muḥammad the prophet, the apostle of God, to Yuḥanna b. Rū’bah and the people of Aylah, for their ships and their caravans by land and sea. They and all that are with them, men of Syria, and the Yaman, and seamen, all have the protection of God and the protection of Muḥammad the prophet. Should any one of them break the treaty by introducing some new factor then his wealth shall not save him; it is the fair prize of him who takes it. It is not permitted that they shall be restrained from going down to their wells or using their roads by land or sea”.

Much of the translation is similar, with minor differences present: “guarantee” instead of “promise of peace”, “caravans” instead of “carriages”, for example. The greatest point of comparison, however, and the reason why I decided to translate the covenant myself, can be seen in the last line of the treaty. Guillaume translates “water they wish to have access to” as “going down to their wells”, which, in the context of a covenant, is entirely significant. Why would the covenant need to mention that the Christians not be barred from taking water from their own wells? The phrasing dictates that these would be wells they already possess and have control over. If Guillaume’s translation is correct, that would mean the covenant says something along the lines of, “they should not be prevented from entering their own homes”. Similarly, Guillaume translates “from any road…they wish to take” as “using their roads”. Again, this is an inaccurate translation, for the same reason cited above, and it blatantly distorts or ignores the original Arabic phrasing, which uses the verb “yurīdūn”, or “they wish”. Perhaps Guillaume meant the antecedent for “their” to be the Muslims, but this is unlikely.

Although the covenant does not explicitly mention anything about integrating Yūḥannah’s community into the Islamic community, or “Ummah”, it implicitly does so by categorizing the residents of Aylah as those who fall under God’s protection. Therein lies the central axis upon which the entire Islamic understanding of religious pluralism rotates: a promise is made to God to protect His people, and a breaching of the covenant’s contract is understood as nothing less than transgressing divine statutes. Two communities that live by religious precepts sent by the same higher power should, in theory, have no reason to be in conflict with each other: this understanding is perhaps what led Pope Shenouda III, Patriarch of the Orthodox Church, to say, “The Copts will be happier and safer under the rule of Islamic Shariah” (

Al-Ahram 2016). (Note: this is not a misquote, nor is this an attempt to mislead the reader. Rather, the interpretation of the venerable Pope’s words is that if Muslims were to act in accordance with Islamic Shariah, the Copts would be safer, as Islam does not condone, nor tolerate, terrorist acts of aggression towards religious groups of any kind. The meaning here is not that the Copts would be better off were they themselves to live by the Islamic Shariah). Christians in particular are held in high regard in Islam and this is due in part to their relation to Jesus, the prophet that Muslims believe came to mankind just before Muḥammad.

3.2. Passages from the Qur’ān and Ḥadīth in Regards to Relations between Muslims and Christians

Below are a few excerpts from Islamic texts that serve to further demonstrate the compatibility of Islam with modern ideas of religious pluralism, and to bolster the claim that Islam respects Christian beliefs, which is perhaps why the covenant was drawn up the way it was.

Islam teaches that there is no compulsion in religion, as per the Qur’ānic verse: “There shall be no compulsion in [acceptance of] religion. The right course has become distinct from the wrong” (2:256 Saheeh International, p. 38). The Qur’ān commends the People of Scripture in general, and warns against arguing with them: “Do not argue with the People of the Scripture except in a way that is best, except for those who commit injustice among them, and say, ‘We believe in that which has been revealed to us and revealed to you. Our God and your God is one; we are Muslims [in submission] to Him’” (29:46 Saheeh International, p. 390). The Qur’ān permits eating the same food as them, the same way it permits marrying their women: “The food of those who were given the Scripture is lawful for you and your food is lawful for them. And [lawful in marriage are] chaste women from among the believers and chaste women from among those who were given the Scripture before you” (5:5 Saheeh International, p. 96).

As for Christians, they have a special status accorded to them, near and dear to Muslims: “You will find the nearest of them in affection to the believers those who say, ‘We are Christians’. That is because among them are priests and monks and because they are not arrogant” (5:82 Saheeh International, pp. 107–8).

The greater significance and ultimate intention behind a covenant is a promise of safety. Therefore, the People of Scripture have God’s promise, His Messenger’s promise, and the promise of all Muslims, that they may live under Islamic rule in peace and tranquility. The Prophet Muḥammad stressed the importance of caring for the “People of the Covenant” and promised that those who violated these commands would meet with God’s wrath and punishment, such as has been related in the following narration of his: Abū Dawūd mentioned:“On the Day of Judgement, I will come against anyone who wrongs someone he has entered into a treaty with (

mu‘ahhid), or fails to give him his due rights, or overburdens him, or takes something from him without his consent” (

Abū Dāwūd 2009, vol. 4, p. 78).

In his

Furūq, Al-Qarāfī relates a quote from Ibn Hazm’s

Marātib al-Ijmā’: “Indeed, it is obligatory on us to go out and fight to the death, with arms and weapons, anyone who comes to our country in pursuit of those who are under our care, in order to protect those who are under God Almighty’s protection and the Messenger’s protection, peace and blessings be upon him. Handing them over to their pursuers is nothing short of breaking the promise of peace” (

Al-Qarāfī 1997, vol. 3, p. 14).

3.3. Prophet Muḥammad’s Meeting with Yūḥannah

As related in Ibn al-Athīr’s biography of the Prophet, Jābir says: “I saw Yūḥannah the day he came to the Prophet Muḥammad. He donned a cross of gold that swung freely (from his neck). When he saw the Prophet Muḥammad, he bowed his head and placed his hand on his chest. The Prophet Muḥammad welcomed him and gifted him a Yemeni dress. He presented the religion of Islam to him, but he did not accept Islam as his religion. He preferred to pay the jizyah. The Prophet Muḥammad guaranteed their safety, and the sum of their jizyah was three hundred dinars.” After the covenant was ratified, Yūḥannah presented the Prophet Muḥammad with a white mule. The delegation that had accompanied Yūḥannah invited the Prophet Muḥammad to dine with them. They wished to amaze him with a meal he had never had before: taro (Colocasia). We do not know, however, if the taro was boiled, roasted, or sliced thin and fried, as the narrations do not mention how it was prepared. The Prophet enjoyed the taro and asked, “What is this?” They told him it was the “fat of the earth”. The Prophet remarked, “It is good” (

Al-Ṣāliḥī 1997, p. 7/212). When Yūḥannah requested the Prophet return with them to Aylah, the Prophet Muḥammad replied, “I am the closest person to the son of Maryam (i.e., Jesus). The prophets are paternal brothers. There is no prophet between me and him” (

Aleasqalānī 2009, vol. 6, p. 563). Yūḥannah did not comment; instead, he continued to smile in silence. Then he went on his way.

Neither in this historical account, nor in the accounting of the event itself as related by Jābir, do we find any display of animosity or ill-will between both parties. Rather, the entire affair was more of an exhibition of mutual respect and an exchanging of gifts and well-wishes.

3.4. Historical Background

Finally, the following historical background is relevant to understanding the circumstances surrounding the covenants:

3.4.1. 7th Century Arabia

In the Levant of the 7th century C.E., there were many great Arab kingdoms and numerous emirates in present-day Jordan, Palestine, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. The influence of the Byzantine Empire was strong, to the extent that most Arabs in the region’s north not only paid allegiance to the Byzantine Empire, but also left their pagan religion after being convinced that the Byzantine Empire derived its power from Christianity. They followed the Byzantine Empire ideologically, culturally, and even imitated it in some of its social customs. The Byzantine Empire was at the height of glory and power, and it is not surprising that Christian Arab kingdoms and many emirates allied themselves with the Romans with the same enthusiasm and partook in the Byzantine Empire’s wars against the Sasanian Empire—even against their Arab brothers and the Prophet Muḥammad.

The year 629 C.E. was a defining year in that severity of circumstances and the increasing activities of key players led to situations the Levant had never seen before, which hastened impossible changes that made the covenants possible. The Byzantine Empire was not at all pleased with these changes, especially since it had been only one year since the empire’s victory over the Persian Empire. According to Arab sources, the Byzantines were preparing their army to conquer Medina. It should be noted that, at times, it is difficult to cross-reference historical accounts from Arab sources with Byzantine sources because the Byzantine tradition, as posited by Kaegi, “contains bias and cannot serve as an objective standard against which all Muslim accounts may be confidently checked” (

Kaegi 1992, p. 3).

The killing of the Prophet Muḥammad’s letter bearer in 629 C.E was also a major tipping point. Shuraḥbīl ibn ‘Amr al-Ghassanī—a subordinate to the Byzantine governor in Balqa—triggered the Battle of Mu’tah between the Muslims and the Byzantines after he killed al-Ḥārithibn Umayr al-Azdī, whom the Prophet Muḥammad had sent with a letter to the King of Busra. Shurahbil intercepted al-Ḥārithibn Umayr al-Azdī and killed him.

The Prophet Muḥammad came to know of al-Harith’s death and was deeply grieved. He was forced to quickly equip an army of three thousand fighters that soon advanced and penetrated into the territories of the Byzantine Empire.

The battle took place in the town of Mu’tah between the Muslims on one side and the Byzantines and some Arab tribes loyal to the Byzantines on the other side. At the time, the Byzantine army was a global superpower comprised of more than a hundred thousand fighters. It is estimated (

Treadgold 1997, pp. 374, 412) that the size of the Byzantine Empire’s field army in the seventh century was about 109,000 strong. We are not sure how many Byzantine soldiers were dispatched to combat the Muslims, but we can assume it was a substantial sum that was unable to defeat the Muslim army.

3.4.2. Tabūk

The Prophet Muḥammad and his army waited a long while to face Heraclius and his great imperial army. Ultimately, they would never meet. The situation spurred the local princes to act and abandon Byzantine fealty. Heraclius’ apparent cowardice succeeded in saving the Byzantine army from battling the Prophet Muḥammad’s army, and Heraclius also succeeded in depriving the Prophet Muḥammad of possibly achieving a decisive victory that would crown his conquests. Heraclius failed, however, to address the belief that spawned among the Arab Christians—who were loyal to the Byzantine Empire—that Muslim power would soon dominate the region. As a result, some of them were convinced of the true divine nature of Islam, and most of them agreed to pay the jizyah (a yearly per-capita tax paid by non-Muslim subjects of an Islamic state). The first examples of such Arabs were Farwah ibn ‘Amr al-Judhami, the governor of Ma’an and a believer in the Prophet Muḥammad, and Tamim al-Dari, a Christian who hailed from Palestine. The final examples of such Arabs were: Ru’bah, governor and military commander of Aylah; Isḥāq, King of Dawma; the ruler of Jarba; and the ruler of Adhruh. They all transferred their allegiance from Heraclius to the Prophet Muḥammad.

3.4.3. Aylah

Aylah (Aylah, or Alyana al-‘Aqabah) was an ancient city that used to be called Elath (written in Latin as “Aela” and in Arabic as “Aylah” (

Ibn Isḥāq 2004, vol. 4, pp. 180–81), and it is now known as the city of ‘Aqabah in Jordan. Its strategic location and proximity to copper mines made it a regional center for the production and trade of copper since ancient times. From a religious standpoint, the city had a bishop appointed to it. An indication of the city’s religious significance is that its bishop witnessed the renowned Council of Nicaea, which was first organized by Emperor Constantine I in 325 C.E. in order for Christians to convene and discuss important issues related to Christianity.

3.4.4. Yūḥannah Ibn Ru’bah

Leaders of the region were observing the situation closely, calculating on a daily basis the amount of time it should have taken for Heraclius and his army to arrive. When they were certain that Heraclius and his great imperial army would not come, they abandoned ties of loyalty to Heraclius. The first to call for peace and proclaim a severance of ties to the Byzantine Empire and its tremendous army, which was the greatest global power at the time, was Yūḥannah, prince and military commander of Aylah. Prince Yūḥannah was a Christian Arab and a military commander who was thoroughly convinced that there would be no fighting. He went to the Prophet Muḥammad in Tabūk and asked that a peace treaty be written out. Yūḥannah did not wait long to confirm Heraclius’ hesitance. Yūḥannah’s intuition was correct in seeking peace, and it seems that he was further encouraged by the good impression the Prophet Muḥammad gave him. When Yūḥannah came to Tabūk, he brought gifts for the Prophet and entered his encampment with a large gold cross hanging from his chest and a staff in his hand. The Prophet Muḥammad did not punish him, nor did he order the removal or confiscation of the cross. Rather, he welcomed and honored him and ordered his muezzin, Bilāl ibn Rabāḥ, to remain stationed at his service throughout his stay. Bilāl had been a Christian before converting to Islam, and he hailed from Abyssinia, a Christian region of the Byzantine Empire at the time.

3.4.5. When did Yūḥannah Arrive?

Arab historians disagree as to when exactly Yūḥannah arrived. Some of them say that he came before Akīdar, King of Dawmah, and there are some that say no sooner had Prophet Muḥammad arrived in Tabūk than Yūḥannah had come. Some historians say he arrived after Akīdar (

Al-Maqrīzī 1997, vol. 2, p. 65), but none of them say he arrived alongside Akīdar. Ibn Isḥāq favored the former stance, Ibn Hishām affirmed it, and Ibn Kathīr followed suit. Akīdar, King of Dawmah, was the mightiest, most influential, and most powerful of the local rulers. He was also the farthest of them from Tabūk. Reasonable conjecture would dictate that he was not exposed to the Prophet Muḥammad, for had he been exposed, it would have opened the way for a bloody massacre. There is no way of telling what might have happened as a consequence of this. Taking their impregnable fortress into consideration, the Prophet wished to astonish the local rulers with his brigades and his actions, so he sent a battalion of soldiers to the most influential, most prestigious, and most distant of the rulers, not to fight and defeat him, but to bring him to the Prophet in order to prove his capacity for compassion and mercy.

The Prophet Muḥammad was prudent in sending Khālid ibn al-Walīd (his lead strategist) as head of a squadron of soldiers bound for Dawmat al-Jandal. Khālid succeeded in capturing King Akīdar while he was out hunting wildebeests, and the squadron returned to Prophet Muḥammad with the king in hand.

After close examination of the evidence, and after studying and weighing the various factors and rationales, one can assume that Yūḥannah arrived before Akīdar, seeing as how a strong conviction arose in him regarding the supremacy of Prophet Muḥammad’s influence and the imminence of his taking hold of the region. When Heraclius asked him to sever allegiance to the Prophet, Yūḥannah refused, even when Heraclius insisted that he would be crucified. Yūḥannah continued to uphold Prophet Muḥammad’s covenant, thus setting the most remarkable example of true Christianity in adhering to covenants and oaths. Had the means of communication at the time been faster, the Muslims would have heard of Heraclius’ decision to crucify him before the order had been carried out.

By comparison, had Yūḥannah come after Akīdar was brought, it would be understood that he had come out of fear of being brought the same way Akīdar, King of Dawmah, had been brought. Had he done that, he would have also done the same as Akīdar, and he would have broken the covenant. However, because he refused to reinstate allegiance to Heraclius, preferring crucifixion over nullifying the Prophet’s covenant, the belief he had in the Prophet’s righteousness and imminent regional supremacy is further proved. This belief, in turn, is what pushed him to take proactive steps to enter into a covenant with Prophet Muḥammad, which he upheld indefinitely.