The Role of Religious Coping in Caregiving Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Caregiving and Stress Process

1.1.1. Primary Stressors

1.1.2. Secondary Stressors

1.1.3. Depression

1.2. Religious Coping and the Stress Process

1.3. Present Research

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

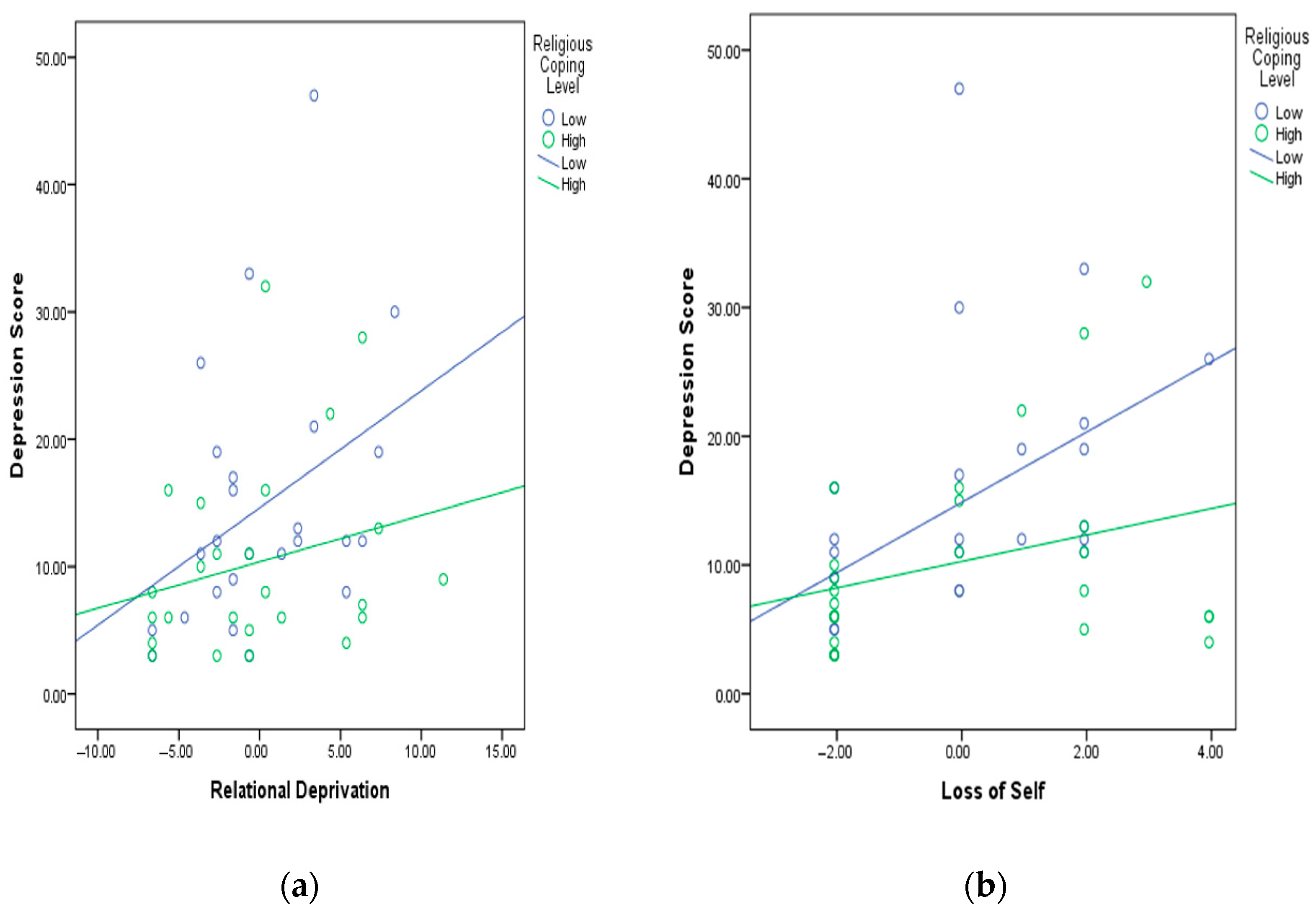

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Theoretical Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, Kathryn Betts, McKee J. McClendon, and Kathleen A. Smith. 2008. Personal Losses and Relationship Quality Indementia Caregiving. Dementia 7: 301–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahles, Joshua J., Amy H. Mezulis, and Melissa R. Hudson. 2015. Religious Coping as a Moderator of the Relationship between Stress and Depressive Symptoms. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 8: 228–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneshensel, Carol S. 2015. Sociological Inquiry into Mental Health: The Legacy of Leonard I Pearlin. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 56: 166–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneshensel, Carol S., Leonard I. Pearlin, Joseph T. Mullan, Steven H. Zarit, and Carol J. Whitlach. 1995. Profiles in Caregiving: The Unexpected Career. San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bademli, Kerime, Neslihan Lök, and Ayten Kaya Kiliç. 2018. The Relationship between the Burden of Caregiving, Submissive Behaviors and Depressive Symptoms in Primary Caregivers of Patients with Schizophrenia. Archive of Psychiatric Nursing 32: 229–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Mary J., Melitta K. Maddox, Laura N. Kirk, Theressa Burns, and Michael A. Kuskowski. 2001. Progressive Dementia: Personal and relational impact on caregiving wives. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias 16: 329–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeson, Rose A. 2003. Loneliness and Depression in Spousal Caregivers of Those with Alzheimer’s Disease versus Noncaregiving Spouses. Archive of Psychiatric Nursing XVII: 135–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bevans, Margaret, and Esther M. Sternberg. 2012. Caregiving Burden, Stress and Health Effects among Family Caregivers of Adult Cancer Patients. JAMA 307: 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, Lídia, João Duarte, Manuela Ferreira, and Carlos dos Santos. 2014. Anxiety, Stress and Depression in Family Caregivers of the Mentally Ill. Aten Primaria 46: 176–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carpenter, Thomas P., Tyler Laney, and Amy Mezulis. 2012. Religious Coping, Stress, and Depressive Symptoms among Adolescents: A Prospective Study. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 4: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Sally Wai-chi. 2011. Global Perspective of Burden of Family Caregivers for Persons with Schizophrenia. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 25: 339–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Kam Hock, and Stephen Horrock. 2006. Lived Experience of Family Caregivers of Mentally Ill Relatives. Journal of Advanced Nursing 53: 435–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Wai-Tong, Sally W. C. Chan, and Jean Morrissey. 2007. The Perceived Burden among Chinese Family Caregiver of People with Schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Nursing 16: 1151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, Sulistiana. 2012. Gambaran Kebutuhan Hidup Orang Dengan Skizofrenia dan Caregivernya di Poliklinik Psikiatri RSUPN Cipto Mangunkusumo. Master’s thesis, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, West Java, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Dumaria, Christina. 2016. Efektivitas Intervensi Keluarga untuk Menurunkan Tingkat Caregiver Burden pada Primary Caregiver Orang Dengan Skizofrenia. Master’s thesis, Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Indonesia, West Java, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Eifert, Elise K., Rebecca Adams, William Dudley, and Michael Perko. 2015. Family Caregiver Identity: A Literature Review. American Journal of Health Education 46: 357–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopther G., and Andrea K. Henderson. 2011. Religion and Mental Health: Through The Lens Of The Stress Process. In Toward a Sociological Theory of Religion and Health. Edited by Anthony J. Blasi. Leiden: Brill, p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Fabricatore, Anthony N., Paul J. Handal, Doris M. Rubio, and Frank H. Gilner. 2004. RESEARCH: Stress, Religion, and Mental Health: Religious Coping in Mediating and Moderating Roles. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 14: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Peter, Amy L. Ai, Nilüfer Aydin, Dieter Frey, and S. Alexander Haslam. 2010. The Relationship between Religious Identity and Preferred Coping Strategies: An Examination of the Relative Importance of Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Coping in Muslim and Christian Faiths. Review of General Psychology 14: 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, Terry Lin. 2000. Integrating Religious Resources within a General Model of Stress and Coping: Long-Term Adjustment to Breast Cancer. Journal of Religion and Health 39: 167–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, Felipe E., Darío Páez, Alejandro Reyes-Reyes, and Rodolfo Álvarez. 2017. Religious Coping as Moderator of Psychological Responses to Stressful Events: A Longitudinal Study. Religions 8: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Timothy M., Christian U. Krägeloh, and Marcus A. Henning. 2014. Religious coping, stress, and quality of life of Muslim university students in New Zealand. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17: 327–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay, Nitin, Nora S. Vyas, Renee Testa, Stephen J. Wood, and Christos Pantelis. 2011. Age of Onset of Schizophrenia: Perspectives from Structural Neuroimaging Studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin 37: 504–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, Angelica P., Jerry W. Lee, Rebecca D. Nanyonjo, Larry E. Laufman, and Isabel Torres-Vigil. 2009. Religious Coping and Caregiver Well-being in Mexican-American families. Aging and Mental Health 13: 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jusuf, Lina. 2006. Asesmen Kebutuhan Caregiver Skizofrenia. Master’s thesis, Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Indonesia, West Java, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, Carolyn. 1995. Family Caregiving Systems: Models, Resources, and Values. Journal of Marriage and Family 57: 179–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Ziasma Haneef, and P. J. Watson. 2006. RESEARCH: Construction of the Pakistani Religious Coping Practices Scale: Correlations with Religious Coping, Religious Orientation, and Reactions to Stress among Muslim University Students. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 16: 101–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Harold George. 2005. Faith and Mental Health: Religious Resources for Healing. West Conshohocken: Templeton Foundation Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kristanti, Martina Sinta, Christantie Effendy, Adi Utarini, Myrra Vernooij-Dassen, and Yvonne Engels. 2019. The Experience of Family Caregivers of Patients with Cancer in an Asian Country: A Grounded Theory Approach. Palliative Medicine 33: 676–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Bong-Jae. 2007. Moderating Effect of Religious/Spiritual Coping in the Relation between Perceived Stress and Psychological Well-Being. Pastoral Psychology 55: 751–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Nan, and Alfred Dean. 1984. Social Support and Depression. Social Psychiatry 19: 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Nan, and Walter M. Ensel. 1989. Life Stress and Health: Stressors and Resources. American Sociological Review 54: 382–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.-Fen, Holly R. Fee, and Hsueh-Sheng Wu. 2012. Negative and Positive Caregiving Experiences: A Closer Look at the Intersection of Gender and Relationship. Family Relations 61: 343–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, L., G. Fadden, M. Madianos, J. M. Caldas de Almeida, T. Held, M. Guarneri, C. Marasco, P. Tosini, and M. Maj. 1998. Burden on the families of patients with schizophrenia: Results of the BIOMED I study. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology 33: 405–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minichil, Woredaw, Wondale Getinet, Habtamu Derajew, and Sofia Seid. 2019. Depression and associated factors among primary caregivers of children and adolescents with mental illness in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry 19: 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. 2018. Basic Health Research Report 2018. Jakarta: Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Noonan, Anne E., and Sharon L. Tennstedt. 1997. Meaning in Caregiving and Its Contribution to Caregiver Well-Being. The Gerontologist 37: 785–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pargament, Kenneth, Margaret Feuille, and Donna Burdzi. 2011. The Brief RCOPE: Current Psychometric Status of a Short Measure of Religious Coping. Religions 2: 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Michelle J. 2005. A Critical Review of the Forms and Value of Religious Coping among Informal Caregivers. Journal of Religion and Health 44: 81–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, Leonard I., Elizabeth G. Menaghan, Morton A. Lieberman, and Joseph T. Mullan. 1981. The Stress Process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22: 337–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, Leonard I., Joseph T. Mullan, Shirley J. Semple, and Marilyn M. Skaff. 1990. Caregiving and Stress Process: An Overview of Concepts and Their Measures. The Gerontologist 30: 583–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, Leonard I., Carol S. Aneshensel, and Allen J. Leblanc. 1997. The Forms and Mechanisms of Stress Proliferation: The Case of AIDS Caregivers. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38: 223–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pew Research Center. 2015. The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010–2050. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Puspitosari, Warih Andan, Shanti Wardaningsih, and Sandeep Nanwani. 2019. Improving the quality of life of people with schizophrenia through community-based rehabilitation in Yogyakarta Province, Indonesia: A quasi experimental study. Asian Journal of Psychiatry 42: 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radloff, Lenore Sawyer. 1977. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1: 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, Loujain, Shimaa Basri, Fidaa Alsahafi, Mashael Altaylouni, Shihanah Albugumi, Maram Banakhar, Nofaa Alasmee, and Rebecca J. Wright. 2020. An Exploration of Family Caregiver Experiences of Burden and Coping while Caring for People with Mental Disorder in Saudi Arabia—A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Juheui, Amy Erno, Dennis G. Shea, Elia E. Femia, Steven H. Zarit, and Marry Ann Paris Stephen. 2007. The Caregiver Stress Process and Health Outcomes. Journal of Aging and Health 19: 871–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streid, Jocelyn, Richard Harding, Godfrey Aguipo, Natalya Dinat, Julia Downing, Liz Gwyther, Barbara Ikin, Thandi Mashao, Keletso Mmoledi, Anthony P. Moll, and et al. 2014. Stressors and Resources of Caregivers of Patients with Incurable Progressive Illness in Sub-Saharan Africa. Qualitative Health Research 24: 317–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudjatmiko, Iwan Gardono, Irsyad Zamjani, and Adrianus Jebatu. 2018a. The Meaning and Practice of Leisure and Recreation: An Analysis of Three Indonesian Muslim Professionals. In Mapping Leisure: Studies from Australia, Asia and Africa. Edited by Modi Ishwar and Teus J. Kamphorst. Singapore: Springer, pp. 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudjatmiko, Iwan Gardono, Lidya Triana, Roy Ferdy Gunawan, Tiara Wahyuningtyas, and Rangga Ardan Rahim. 2018b. Social Well-being, Religion, and Suicide: A Comparison of Japan and Korea with Thailand and Indonesia. The Senshu Social Well-Being Review 5: 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tarakeshwar, Nalini, and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2001. Religious Coping in Families of Children with Autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 16: 247–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, Peggy A. 2011. Mechanism Linking Social Ties and Support to Physical and Mental Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 52: 145–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, Justin, and Mariapaola Barbato. 2020. Positive Religious Coping and Mental Health among Christians and Muslims in Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Religions 498: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristiana, Rr Dian, Bayu Triantoro, Hanik Ending Nihayati, Ah Yusuf, and Khatijah Lim Abdullah. 2019. Relationship between Caregiver’s Burden of Scizophrenia Patients with Their Quality of Life in Indonesia. Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Mental Health 6: 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, Blair. 1985. Models for the Stress-Buffering Functions of Coping Resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 26: 352–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheaton, Blair, Marisa Young, Shirin Montazer, and Katie-Stuart Lahman. 2013. Social Stress in the Twenty-First Century. In Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health, 2nd ed. Edited by Carol. S. Aneshensel, Jo C. Phelan and Alex Bierman. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | n | % | Mean of Depression Score | Mean of Relational Deprivation Score | Mean of Loss of Self Score | Mean of Religious Coping Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship with PwS | ||||||

| Parent | 30 | 60 | 13.2 | 11.9 | 4.4 | 24.5 |

| Wife/husband | 4 | 8 | 6.5 | 14.2 | 3.0 | 28.0 |

| Child | 3 | 6 | 13 | 17.3 | 4.7 | 25.0 |

| Sibling | 13 | 26 | 12.7 | 12.8 | 3.3 | 23.9 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 16 | 32 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 4.4 | 25.4 |

| Female | 34 | 66 | 13.1 | 13.0 | 3.8 | 24.3 |

| Religion | ||||||

| Islam | 39 | 78 | 12.4 | 12.5 | 4.3 | 25.1 |

| Christian | 6 | 12 | 16.0 | 15.7 | 3.5 | 24.7 |

| Catholic | 5 | 10 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 2.8 | 21.4 |

| Age | ||||||

| 20–29 | 4 | 8 | 13.5 | 13.5 | 2.5 | 20.5 |

| 30–39 | 5 | 10 | 15.6 | 12.2 | 4.0 | 26.2 |

| 40–49 | 9 | 18 | 11.9 | 14.8 | 4.1 | 25.1 |

| 50–59 | 11 | 22 | 11.0 | 11.6 | 3.6 | 24.7 |

| 60–69 | 19 | 58 | 13.5 | 12.6 | 4.8 | 24.6 |

| 70–79 | 2 | 4 | 5.5 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 28.0 |

| No | Items | Islamic M (SD) | Christian M (SD) | Catholic M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Looked for a stronger connection with God. | 3.61 (0.59) | 3.50 (0.55) | 3.20 (0.84) |

| 2 | Sought God’s love and care. | 3.59 (0.64) | 3.50 (0.55) | 2.60 (1.14) |

| 3 | Sought help from God in letting go my anger. | 3.59 (0.64) | 3.67 (0.52) | 3.00 (0.71) |

| 4 | Try to put my plans into action together with God. | 3.54 (0.60) | 3.50 (0.55) | 3.20 (0.84) |

| 5 | Tried to see how God might be trying to strengthen me in this situation | 3.59 (0.68) | 3.33 (0.52) | 3.20 (0.84) |

| 6 | Asked forgiveness for my sins | 3.72 (0.51) | 3.67 (0.52) | 3.20 (0.84) |

| 7 | Focused on religion to stop worrying about my problems | 3.46 (0.82) | 3.50 (0.55) | 3.00 (0.71) |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relational Deprivation | 12.6 | 4.67 | 1 | 0.351 * | 0.016 | 0.303 * |

| Loss of Self | 4.04 | 2.04 | 1 | 0.129 | 0.365 ** | |

| Religious Coping | 24.7 | 3.85 | 1 | −0.249 *** | ||

| Depression | 12.5 | 9.26 | 1 |

| Predictor | Coeff B a | SE B | Β b | p | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | i1 | 12.540 | 1.228 | 0.000 | 0.157 | |

| Relational Deprivation | b1 | 0.610 | 0.266 | 0.307 * | 0.026 | |

| Positive Religious Coping | b2 | −0.611 | 0.322 | −0.254 *** | 0.064 | |

| Intercept | i2 | 12.581 | 1.197 | 0.000 | 0.217 | |

| Relational Deprivation | b1 | 0.715 | 0.265 | 0.360 * | 0.010 | |

| Positive Religious Coping | b2 | −0.762 | 0.324 | −0.317 * | 0.023 | |

| Relational Deprivation * Positive Religious Coping | b3 | −0.144 | 0.077 | −0.258 *** | 0.067 |

| Predictor | Coeff B a | SE B | Β b | p | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | i1 | 12.540 | 1.179 | 0.000 | 0.222 | |

| Loss of Self | b1 | 1.833 | 0.589 | 0.404 ** | 0.003 | |

| Positive Religious Coping | b2 | −0.724 | 0.312 | −0.301 * | 0.025 | |

| Intercept | i2 | 12.843 | 1.168 | 0.000 | 0.270 | |

| Loss of Self | b1 | 2.197 | 0.614 | 0.484 ** | 0.001 | |

| Positive Religious Coping | b2 | −0.959 | 0.334 | −0.399 ** | 0.006 | |

| Loss of Self * Positive Religious Coping | b3 | −0.306 | 0.176 | −0.248 *** | 0.090 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Triana, L.; Sudjatmiko, I.G. The Role of Religious Coping in Caregiving Stress. Religions 2021, 12, 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060440

Triana L, Sudjatmiko IG. The Role of Religious Coping in Caregiving Stress. Religions. 2021; 12(6):440. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060440

Chicago/Turabian StyleTriana, Lidya, and Iwan Gardono Sudjatmiko. 2021. "The Role of Religious Coping in Caregiving Stress" Religions 12, no. 6: 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060440

APA StyleTriana, L., & Sudjatmiko, I. G. (2021). The Role of Religious Coping in Caregiving Stress. Religions, 12(6), 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060440