Abstract

Today, it is challenging to separate online and offline spaces and activities, and this is also true of digital religion as online and offline religious spaces become blended or blurred. With this background, the article explores the need for new typologies of what is religious on the Internet and proposes a conceptual framework for mapping digital religion. Four types of that which is religious on the Internet are presented based on influential classification by Helland. He introduced (1) religion online (sites that provide information without interactivity) and (2) online religion (interactivity and participation). Helland’s concept is developed by, among others, adding two types: (3) innovative religion (new religious movements, cults, etc.) and (4) traditional religion (e.g., Christianity or Islam). Each type is illustrated by selected examples and these are a result of a larger project. The examples are grouped into three areas: (1) religious influencers, (2) online rituals and (3) cyber-religions (parody religions). Additionally, the visual frame for mapping digital religion is presented including the examples mentioned. The presented framework attempts to improve Helland’s classification by considering a more dynamic nature of digital religion. The model is just one possible way for mapping digital religion and thus should be developed further. These and other future research threads are characterized.

1. Introduction

Early studies on the Internet often praised its social and cultural impact. The Web was supposed to overcome the physical and social barriers of everyday life, as the time had come for the first truly global communication tool (see, e.g., Fisher and Wright 2001; Kergel 2020; Parna 2006). After this long period of utopian ideas, the last couple of years have revealed many disruptive ways in which the Internet can be and is used. Internet utopians acknowledge the recent disruptive trends, threats to democracy, the rise of online extremism, online fakes, etc. (see, e.g., Bartlett 2018; Levinson 2020).

The arguments presented by both utopians and researchers showing the negative side of the Internet seem to be one-dimensional and simplify the socially and culturally intricate reality. The Web is not a tool of universal happiness, prosperity and community. The hopes of utopians did not come true, because the Internet does not lie somewhere outside of the offline spaces, and does not “detach” itself from those. This is also the reason why not all users insult others, pretend to be someone else, or post fake news. Over the past 20 years, it became clear that it is difficult to separate online and offline spaces and activities. The most credible approach to the Internet is to claim that offline spaces cannot be separated from online ones, as they both interpenetrate and shape each other (see, e.g., Bolander and Locher 2020; Gomoliszek and Siuda 2017; Grimmelmann 2006).

With this background, the article deals with digital religion as scholars discuss how online and offline religious spaces become blended or blurred. Offline religious contexts intersect with online spaces, and a kind of hybrid spaces emerge (see, e.g., Campbell 2013, 2017; Lundby 2012). That which is religious offline shapes the digital. This does not mean that the opposite is not true, i.e., the digital shapes the contemporary religion. However, I do not aim to unravel the intricate interplay between offline and online. Rather, I focus on mapping and categorizing what is religious on the Internet, and the aim is to explore the need for new typologies. With this in mind, the article introduces a concrete conceptual framework for mapping religious online sites. For this purpose, four types of digital religion are presented in the following sections (compare Siuda 2010, 2012). These provide a demonstration of how we can begin to think more expansively about providing such typologies with plenty of room for additional innovation beyond the one proposed here.

In broad terms, religion is recognized as a social-cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, ethics, organizations, and other elements that relate to supernatural, transcendental, spiritual, and sacred. With no clear consensus over what precisely constitutes a religion, I assume after Karaflogka (2002) that religion—being an “influential force in human culture” (p. 279)—is a fluid and contested concept, “notoriously difficult to constrain within any one meaning” (p. 280). This is in line with the notion that any typology of digital religion (also the one presented here) is not definite and must be open to modifications.

Campbell (2017) described the evolution of digital religion research in terms of four waves:

In wave 1—the descriptive era—scholars sought to document what was happening to religious practices on the Internet (…). In wave 2—the time of categorization—scholars attempted to provide concrete typologies, identifying trends occurring within religious Internet practice (…). In wave 3—the theoretical turn—scholars focused on identifying methods and theoretical frameworks to help analyze offline religious communities’ strategies related to new media use (…). Wave 4 highlights current scholarly focus on religious actors’ negotiations between their online and offline lives, and how this informs a broader understanding of the religious in the contemporary society.(Campbell 2017, p. 17)

Additionally, digital religion researchers engage with several theoretical approaches (see Campbell 2017; Campbell and Vitullo 2016; Helland 2016):

- Mediatization of religion, which emphasizes that the media are crucial when it comes to shaping religious experiences. Media are the primary source of information about religion, and dominate and define the social order, including the religious one (Hjarvard 2008, 2014; Lövheim 2011; Lövheim and Lynch 2011).

- Mediation of meaning (Hoover 2006) assumes that media help people explain or assimilate religious ideals or beliefs. People are active in searching for the meaning of what is religious and use their own experiences and the information coming from media. The Internet has an important role to play in negotiating and expressing beliefs as well.

- The third spaces of digital religion (Echchaibi et al. 2013; Hoover and Echchaibi 2015) extend the mediation of meaning theory as it assumes that many online spaces help people to “determine” what religion means to them thus shaping religious cultures. Traditional structures of social power and religious identities, and human experiences, as well as media representations combine here, leading to the online reimagining of religion.

My considerations fit into Campbell’s second wave and I do not advocate one particular theoretical approach of those indicated above. Nevertheless, it is worth considering them as digital religion is in line with religious tendencies of modern society, i.e., religious individualization, and commodification of religion (see, e.g., Horsfield 2015; Rähme 2018). Religion is more like a commodity now (Grieve 2013). For people choosing religion like consumers, the Internet is a perfect tool, as it allows them to be religious on their terms. This point of view is important for the presented here mapping of religious content online.

Besides, the Internet reinforces the transformation and/or decline of religious authority. Individuals are free to ignore mediating authorities as they can directly access online content on their own. They no longer rely on authorities although the sources they access may be authoritative. Researchers point out that in today’s Western societies, the authority of the great religious traditions and church institutions has eroded (for discussion on this topic, see, e.g., Cloete 2016; Evolvi 2020; Giorgi 2019; Hutchings 2011, 2017; Kołodziejska 2018; Kołodziejska and Neumaier 2017; Porcu 2014; Solahudin and Fakhruroji 2020; Staehle 2020). On the other hand, some emphasize that the reverse process is taking place. For example, Cheong et al. (2011) showed that Buddhist religious leaders use social media to strengthen their authority. Guzek (2015) showed how Twitter can be used for the same purposes in the case of the papacy. He examined Pope Francis’ tweets for half a year of his pontificate. Guzek’s study offers an “in-depth overview of methods for studying the presence of religious authority in the digital world” (Guzek 2015, p. 63).

When it comes to digital religion, network society theory is also worth considering. More and more human activities are organized as networks, decentralized and flexible, freed from the territorial restrains, with the Internet as a major tool of shaping these networks (Castells 2000). Religion is not an exception, as emphasized by the networked religion theory by Campbell (2012). When it comes to religion, network society means the flattening of traditional religious hierarchies (Campbell 2007, 2010; Campbell and Evolvi 2020), immediate communication, and the rise of the so-called religious virtual communities. These are structured upon social networks of varying levels of commitment (see, e.g., Aeschbach and Lueddeckens 2019; Campbell and Vitullo 2016; Neumaier 2019).

One of the most important challenges in analyzing what is religious on the Internet is dealing with a huge number of overlapping and interrelated sites and phenomena. The increasingly blurry lines between offline and online communication and behavior do not help in mapping digital religion either. For example, different hybrid events may have both an in-person and live-streamed component. In the case of the presented research, handling these is about analyzing the online content and that which is visible online.

Although I later use various examples, the article is not meant to be a catalog (or list) of websites or online tools. The preparation of such could not even be possible due to the massiveness and dynamic nature of online content. This is why, wherever I refer to any site, I avoid giving URLs. These can change very quickly and the tools popular today may lose their importance tomorrow or even disappear completely.

In the following sections of the article, I indicate one possible way for mapping religious content on the Internet by distinguishing four types of religious online spaces. I define these and show the methods that I used to search for religious spaces online. Next, I give examples of sites and activities organized into three main areas and then refer these examples to pinpointed types. The article ends with a discussion, where I briefly summarize the considerations, show the directions of future research and the limitations of the presented analyses.

2. Types of Digital Religion

Mapping and classifying online religious sites is important when it comes to research on digital religion, as it provides a framework for empirical studies. I distinguish four types of religious online spaces and these are: (1) religion online, (2) online religion, (3) traditional religion and (4) innovative religion. The first two types follow the influential classification by Helland (2000b) and refer to religious participation occurring online. The next two are about long-existing, established, institutional traditions (Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, etc.) on the one hand, and new religious movements, cults, self-proclaimed prophets, or gurus, quasi-religious phenomena, etc., on the other.

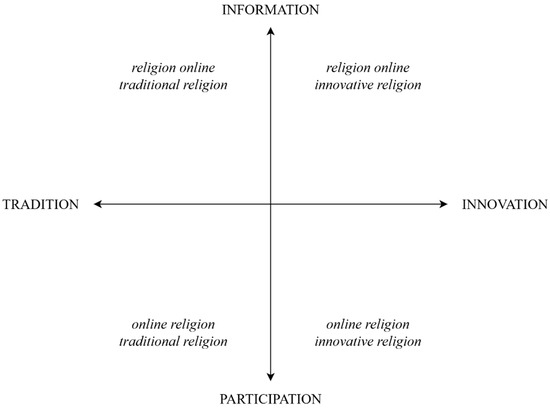

Each religious online space relates to the indicated four types. On the one hand, a given site is closer to religion online or online religion, and on the other hand, it is more traditional or innovative. Figure 1 visualizes the frame for mapping digital religion, and a given site and/or tool may be placed on a given point of the model depending on its characteristics. Next, I explain four types more clearly, and how one can decide to place a given online space on a particular spot on the frame.

Figure 1.

The visual frame for mapping online religious spaces.

Religion online and online religion were proposed by Helland (2000b, 2005, 2007) who noticed that religious spaces can offer a lot of autonomy when it comes to activities of users, and are highly interactive and participatory, and these are online religion. Religion online, on the other hand, is only about providing information without interactivity. Helland associated the division with the institutionalization of religion. Religion online means churches and traditional hierarchies being digitally present. Online religion is the not-so-formal community or communities which means communication, participation, membership, etc.

I develop Helland’s concept in two ways. He argued that religion online embodies one-to-many communication, so we are dealing here with a form of mass media. Online religion is the so-called web 2.0, so it is primarily about many-to-many communication, which simulates human creativity and participation. Originally, Helland (2000b) assumed that a given website could be only informational or participatory. Under the growing criticism, he revised the typology and concluded that:

Many religious Web sites (…) provide both information and an area where this information can be lived and communicated. (…) Web sites try to incorporate both an information zone and interaction zone in a single site or, more commonly, where popular unofficial Web sites provide the area for online religion, while the official religious Web site supplies religion online.(Helland 2005)

Despite this revision, it seems that the “mixing” of religion online and online religion needs to be raised more clearly as Helland’s standpoint remains too “rigid”. Helland’s 2005 work reflects the technology and use of the Internet at that early period. He did not consider many new tools, as the Internet continues to evolve. Today, technological change that has occurred must be noted and a more nuanced model is necessary.

It is true that most online spaces provide information or stimulate participation in different proportions. The official church website not only informs but could include a forum or chat room. A given virtual community usually refers to information related to a specific religion. The improved model presented here reflects more clearly that the two types interpenetrate, as it recognizes that the mixing varies greatly with the tools used. The nature and intensity of participation differ depending on whether one uses social media, forums, or instant messaging tools, and these differ as well, depending on the purpose they serve (e.g., communication, rituals, etc.). Claiming that religion online is more institutionalized seems too rigid as official religious websites and less formal groups or individuals may “use” both types equally (for examples, see Baffelli et al. 2010).

Deciding on the intensity of participation may not be easy. While instant messaging tools, forums, or online rituals could be considered participatory, in the case of other spaces, one may not be that sure. For example, are viewers of religious videos on YouTube passive or active since they can only post a comment or do not reveal their presence at all. The broad view applied here adopts a technical criterion, which means that if a given space uses participatory technologies, it is considered as moving toward online religion. These technologies include social media, forums, blogs, comments, virtual worlds, etc. I elaborate on this and give examples in the next sections.

I further develop Helland’s idea by adding two additional types, i.e., innovative and traditional religion. With these, the idea is to make a model polythetic and therefore more practically descriptive, as the innovation vs. tradition division is based on the source of authority online. The examples indicated in the next sections have different sources of authority that legitimizes their discourse online (see Campbell 2010; Cloete 2016). Traditional religion is long-standing, institutionally established religions (Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, etc.) and this is the source of authority. Everything that stands out is more or less innovative (new religious movements, cults, quasi-religious phenomena, etc.). This does not mean that other sources of the division into innovation and tradition cannot be included in the framework. Indicating and including these sources is a way to further develop the model and I elaborate on this in the Discussion section.

Considering the religious tradition of a given online space makes Helland’s proposal less rigid once more, especially since traditions differ when it comes to religious activities. Besides, considering these two additional types allows mapping religious internet sites more accurately. This is especially so, as both traditional and innovative religions mix and interpenetrate each other and must be considered as Weberian ideal-types (see, e.g., Lindbekk 1992), similarly to religion online and online religion. For example, the Japanese organization Soka Gakkai is a religious movement, but it is one of several Nichiren-related Buddhist groups online. A given online space may connect long-standing traditions with new religious movements or cults. What is more, on the Internet, laypeople can challenge the authority of clergy within a given tradition and that is a move toward innovativeness. Online spaces are multidimensional, i.e., a given space moves toward a particular ideal- type depending on its characteristic. It is worth stressing that the two dyads are not on a similar level, and I elaborate on this in the Discussion. I also explain relations between the types more clearly, elaborate on what the two new types do bring to Helland’s classification, and the ways the model could be further developed.

2.1. Methods

Only a few examples of online religious sites are indicated here, and these are a result of a larger project devoted to human activities online and the intersections between the Internet and religion. The project is in its early stages, and the researcher’s aim is to answer several research questions, including:

- What online tools do people use when it comes to digital religion?

- What religious activities do they undertake?

- What is the nature and quality of people’s religious experiences online?

- How religious authority changes and what are the sources of this authority in the case of digital religion?

The project’s initial phase involves systematically building a database of digital religion spaces, considering the above-mentioned research questions. This article is the result of these preliminary research activities. The database is being continuously expanded with the use of netnography, i.e., an online research method that translates traditional ethnography into studying computer-mediated communication, mainly virtual communities (Kozinets 2009; Tunçalp and Lê 2014).

It is argued that the netnographer should actively participate in the life of the studied communities (Kozinets 2009), but this is not obligatory (Tunçalp and Lê 2014). In the case of the project’s early stages, netnography is purely observational. It is more about becoming a lurker who does not “bother” users, hence this is just an exploration of various religious online sites, and the initial unsystematic analysis of these. Search engines, web directories, and social media internal search engines are being used to reach religious online spaces (see Siuda 2010, 2012). The later stages of the project involve using participatory netnography and other methods, including in-depth interviews.

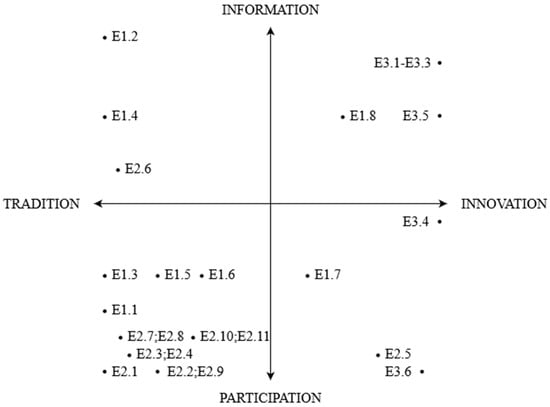

The aim of this article is conceptual, hence it comes at this initial phase of the project. The following examples are illustrative of the presented conceptual framework. I group the examples into three areas and mark them with the letter E and numbers accordingly (e.g., E1.1, E1.2, E2.1, etc.), to accurately relate these examples to the proposed framework. In the further section of the article, I present the second version of the visual frame (Figure 2) including the examples mentioned. Figure 3 clarifies how I decided on assigning a given place to a specific type—four in-depth cases are indicated. All sites are active for March 2021.

Figure 2.

The visual frame for mapping online religious spaces with placed examples.

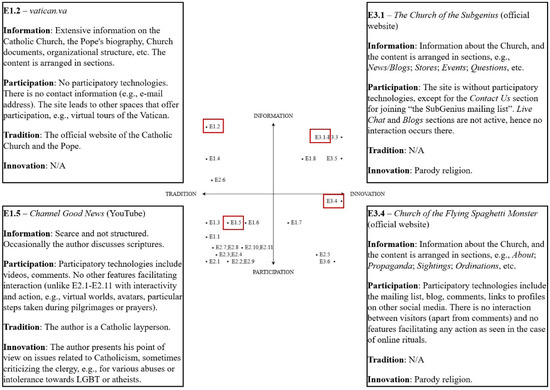

Figure 3.

The visual frame with four examples highlighted to show how online spaces have been assigned to given types.

2.2. Area 1—Religious Influencers

Influencers are bloggers, vloggers, social media users, etc., gaining considerable audiences (see, e.g., Freberg et al. 2011) with an interest in lifestyle in general as well as fashion, sex, medicine, education, and so on. Some users can be considered as religious influencers and these are both clergymen and laypersons. They differ in the degree of “innovativeness” of their messages, with clergymen usually closest to traditional religion as the innovativeness vs. tradition is based on the source of authority. They also differ when it comes to openness to user participation.

In the case of the Catholic Church, Pope Benedict XVI noted that new media is an important tool for communicating Catholic values and beliefs, evangelization, and making people come back to the brick-and-mortar church (Solatan 2013). However, it was not until Francis I that the Pope became a true religious influencer (see, e.g., Guzik 2018; Narbona 2016; Zijderveld 2017). His Twitter profile (E1.1) accords to best practices of influencer marketing (see, e.g., Sammis et al. 2015), as short and accessible posts signal problems that the Church is struggling with, or inform about the Pope’s position on a given subject. These posts are re-tweeted and commented on by mainstream media, and so the interaction and participation flourish, as shown, for example, by Guzek (2015). Communicating the papacy standpoint, without the need to read long and often hard to comprehend official documents is consistent with the Pope’s views on new media (see Guzek 2015). Francis I repeatedly emphasizes that the Internet—if used well—is a tool for doing good in the world (Narbona 2016; Zijderveld 2017). In the case of the Catholic Church, the Pope’s Twitter profile differs from the static and purely informative website vatican.va (E1.2).

Catholic clergy are using the Internet more and more. For example, in Poland, the most popular religious influencer is Father Adam Szustak, who states on his YouTube profile that the Web may be the “largest church in the world”. Szustak has almost 800,000 subscribers, with the channel enigmatically called Langusta na palmie (Crawfish on a palm tree) (E1.3) and operating since 2012. The priest uses the crowdfunding platform Patronite.pl to finance his YouTube activity and, so far, he has accumulated over 800,000 PLN (around 200,000 EURO). Therefore, Szustak’s activity strongly depends on the viewers and their participation and willingness to contribute. The popular on Polish YouTube Crześcijański Vlog (Christian Vlog) (E1.4) led by Father Piotr Pawlukiewicz is quite different. The priest posts sermons delivered in a brick-and-mortar church. These are recorded and presented on YouTube without the possibility to comment. Each sermon has tens of thousands of viewers, and the profile itself has 157,000 subscribers.

When it comes to laymen, the most popular influencer in Poland is Mikołaj Kapusta from Kanał Dobra Nowina (Channel Good News) (E1.5) on YouTube. This theology student has 39,000 subscribers and stresses that he “also addresses atheists.” Jola Szymańska on the Hipster Katoliczka (Catholic hipster) YouTube channel (E1.6) states: “I post because I believe in life without pigeonholing believers and non-believers. I believe in thinking and dialogue and god. And that she has a sense of humor.” Both Michał Kapusta and Jola Szymańska present their views on what it means to be a Catholic.

Influencers from Rainbow Faith and Freedom (E1.7) may be considered more controversial. They are both Christians and members of the LGBTI community. Their homepage greets visitors with the words: “We are a global movement that confronts religious-based LGBTI discrimination and improves the human and equality rights of LGBTI people everywhere.”

Catholic visionaries are equally controversial, as they use the Internet to report, document and testify their mystical experiences, and their authority is based on direct religious experience. In his book, The Internet and the Madonna, Apolito (2005) characterizes the visionary movement on the Web. He shows that although most of the apparitions refer to Catholicism straightforwardly, the visionaries are not recognized by church authorities or even condemned by the hierarchs (see Apolito 2005, p. 198). The Fatima Center (E1.8) is a website referring to the Portuguese apparitions of 1917. Although it seems to present the official position of the Catholic Church, it was founded by Nicholas Gruner, a Canadian priest who has repeatedly challenged the authority of the Vatican.

2.3. Area 2—Online Rituals

Online rituals mean activity and participation. In general, the term ‘ritual’ is used in a multitude of meanings, and various approaches focus on the course of rituals, their aesthetics, structure, communication, symbolism, etc. I do not rely on any specific definition nor do I focus on any of these aspects. Many researchers study online rituals (Jacobs 2007; Miczek 2008) beginning with early studies on neo-pagan rituals (see, e.g., Bittarello 2008; Brasher 2004; Grieve 1995; Helland 2000a; O’Leary 1996; Zaleski 1997). So far, the following online rituals have been studied the most often:

- Rituals based on text, graphics, virtual (three-dimensional) environments similar to computer games (Piasecki 2018). For example, The Church of Fools (E2.1) sponsored by the Bishop of London and the Methodist Church in Great Britain (see, e.g., Jenkins 2008), or Second Life rituals (for example, the ones performed in the Islamic mosque in the fictional region of Second Life called Chebi; E2.2) (see also Radde-Antweiler 2008).

- Virtual pilgrimages, for those who, for some reason, cannot go in person (Hill-Smith 2011; Kalinock 2006; MacWilliams 2002). The Internet is a kind of substitute here and evokes spiritual experiences, as in the case of The Virtual Hajj (E2.3), i.e., a virtual pilgrimage to Mecca. Many of the most important Christian offline pilgrimages in Western Europe can be made online, e.g., the Lourdes—www.lourdes-france.com, accessed on 21 May 2021 (E2.4). Members of new religious movements also make online pilgrimages, as shown by Coats and Murchison (2015) who studied New Age spiritual tourism of the Synthesis 2012 festival (E2.5).

- Prayer apps, websites, and other tools. For example, Öhman et al. (2019) clarify the role of Islamic prayer-bots on Twitter and prayer apps. Showing the example of Du3a.org (E2.6) service, they claim that apps, which automatically post prayers from its users’ accounts, are responsible for millions of tweets daily, constituting a significant portion of Arabic-language Twitter traffic (see also Wagner 2013). On saranam.com (E2.7), Hindu worshipers can say a prayer or offer (additional fee involved) a sacrifice at one of India’s 400 temples. The Sacred Space (E2.8) run by Irish Jesuits offers daily prayer assistance which is to follow the directions that appear on the screen. The World Prayer Team (E2.9), in turn, is about building prayer communities. Other spaces of online prayer are virtual cemeteries to commemorate deceased relatives (see also Duteil-Ogata 2015)—for example, The World Wide Cemetery (E2.10) or Virtual Grave (E2.11).

2.4. Area 3—Cyber-Religions

The Internet is full of so-called parody religions or fake cults. Karaflogka (2002) called these religions in cyberspace/cyber-religions to emphasize that the Internet is crucial to their rise. For the most part, religion in cyberspace is a satire against “ordinary” religious traditions, politics, consumerism, etc. The deity of The Church of the Subgenius (E3.1) is not a metaphysical being, but Bob, a middle-class American. In the religion called Kibology (E3.2), the polls decide who to worship. Faithful of the Virtual Church of Blind Chihuahua (E3.3) “believe what they want”, and the followers of the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster (E3.4) worship a floating mass of spaghetti noodles with a large meatball on either side of its body (Obadia 2015). Religions in cyberspace visionaries report about their apparitions. Founder of crystalinks.com (E3.5) reports on the visions she experiences with a being called Z, which she considers as being the incarnation of the Egyptian god Thoth.

Fake cults can be viewed as role-playing games, satire, or identity experiments (Obadia 2015). Chidester (2005) claims that some fake cultists treat their beliefs very seriously, undermining accepted ways of distinguishing “real” religions from those considered to be jokes or parodies. Chidester describes the struggle of the Discordianism fake cult to be listed in the “Religion and Faith” section of the Yahoo directory, not in the “Religious Parodies” section (Chidester 2005, p. 199). Thus, parody religions can be considered as innovative religion, as through parody and satire they “defy” the long-standing, “serious”, and “official” traditions.

Cyber-religions are not just parody though. There are non-satirical examples in this area as well. These also seem unusual by mainstream standards but tend to be quite serious. Karaflogka (2002) mentions Digitalism or Cosmosophy. She also distinguishes a quite serious type of cyber-religion she calls New Cyberreligious Movements giving Falun Gong and Partenia as examples. “New because they address issues using a new medium and introducing new possibilities; Cyberreligious because they mainly exist and function on-line; Movements because they can, potentially, mobilise and activate the entire human population” (p. 286). I do not include these in the visual frame below as I focus on a particular type (parody) of cyber-religions.

However, fake cults can be seen as a kind of new religious movements (see Chidester 2005). These also make up the innovative religion, but are much more “serious”, and often also controversial. The example here is The Family International (formerly known as The Children of God) (E3.6). This group performed the so-called “Reboot” (Borowik 2018; Helland 2016). Since 2010, it operates entirely online as chapter houses and communal homes were dissolved, and the group began to rely on online activity and Internet communication.

2.5. Examples and the Types of Digital Religion

Figure 2 refers the above-mentioned examples to the previously indicated four types to show how one can map what is religious on the Internet. Figure 3, on the other hand, explains how online spaces have been placed on a particular spot on the frame in four selected examples. The two figures are separated for clarity.

3. Discussion

As mentioned before, digital religion researchers recognize that between online and offline spaces and contexts, there is a lot of intersecting and blending. The original Helland’s perspective seems, therefore, one-dimensional and undynamic, and the presented model is an improvement because it is a step toward a more dynamic framework.

The two indicated dyads are two different levels of how religious spaces can be considered. The model includes two different approaches and perspectives on digital religion (online religion vs. religion online and innovative vs. traditional religion). However, the difference between these two levels does not make the main purpose of the model less important, and this is to capture what is religious on the Internet, as it is a general model (like Helland’s). Adding an innovative vs. traditional level is an attempt to improve the original classification by considering a more dynamic nature of digital religion.

I do not claim that the new model is complete and that it should ultimately replace the one by Helland. As mentioned before, his classification is outdated, needs to be expanded upon, and the conceptual framework presented here provides a demonstration of how we can begin to think more expansively about typologies of digital religion. The article is not so much about presenting the ultimate frame but rather about exploring the need for further typologies.

The new model could be developed further, as one can make more precise distinctions about the intensity of interaction and participation, and the features of different online tools. Based on this, new types (or sub-types) can be introduced, for example, the ones related to the use of social media like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, etc. Similarly, the model can be improved by considering the nature of religious innovativeness and traditionality. I pointed out that the source of authority online can be helpful here, but the model can be expanded to further elaborate on what makes particular groups, spaces, or phenomenon innovative or traditional.

The presented framework should be further developed also because digital religion is shaped by social, cultural, and historical factors, a topic not addressed here fully. The importance of researching religious meanings in various contexts and/or different parts of the world is raised by the religious–social shaping of digital technology approach proposed by Campbell (2017). She emphasizes “how individuals and groups within particular cultural contexts see their technological choices constrained by broader structural and social elements of their worldview and belief systems”. According to Campbell, the history of a given religion is important in the context of shaping the concept of community or authority. It is also crucial to identify core values of this religion and relate them to the use of information technologies or communal shaping of discourses regarding the use of these technologies (see also Bako and Hubbes 2011; Shahar and Lev-On 2011). Helland argues (Helland 2007) that a given tradition may be more oriented towards studying scriptures or evangelizing and these differentiate online activities. In the case of studying scriptures, religion online prevails, and evangelizing means a more participatory approach (for the opposite view to Helland’s see MacWilliams 2006). Besides, regardless of how the Internet is used, a given tradition must recognize new technologies, and a certain narrative indicating “good uses” of these is essential here (see also Noomen et al. 2011).

For example, in the case of the Catholic Church, there is a narrative that the Internet is a tool given by God, and therefore it can be used to reach the faithful (see, e.g., Narbona 2016 and the Pope example mentioned earlier; e.g., Zijderveld 2017). Some religious diasporas have a similar positive narrative, as the Internet connects the faithful, and brings them closer to their origins (see Virtual Tibet example by Helland 2015). Another example is Hinduism, with its long-standing concept of practicing religion at home rather than in temples (see e.g., Beckerlegge 2001; Scheifinger 2008, 2010), making online rituals more acceptable. Many of the fake cults claim that the Internet is crucial for spiritual life. In general, it can be said that the positives of using the Internet are emphasized by many religious groups or traditions.

Within a given tradition, not all have to agree on the role of the Internet. A positive or skeptical attitude towards the Web is determined by local cultural, political, or social factors (see e.g., Fukamizu 2007; Kawabata and Tamura 2007). For example, online Islam looks different in a multicultural country like Malaysia or Singapore than in the case of Arab countries or Islamic minorities (see e.g., Goalwin 2021; Siti Mazidah Haji Mohamad 2018; Piela 2010; Ridwan et al. 2019; Slama 2018; Solahudin and Fakhruroji 2020; Sorgenfrei 2021).

Such differences are worth exploring when it comes to mapping digital religion, but this is only one of the possible directions of future research in this regard. At least a few areas require more attention:

- More studies are needed on how people use the Internet for religious purposes, and why they use it. There is a clear need for long-term research that would show the changes taking place in this regard. How does the Internet compare to other media? What tools and solutions are most common? These are just a few questions worth answering.

- Qualitative research is needed into the nature and quality of people’s spiritual experiences online, both individuals and communities.

- There is a need for more detailed and comparative research on online religious activities, especially rituals.

- Attention should be paid to how the digital religion depends on the actions of media corporations such as Google, Facebook, Apple, etc. Helland noticed that “the structure created by these corporations (and governments) heavily dictates and channels people’s level of digital religious activity” (Helland 2016, p. 194).

Digital religion is not an easy field to research, not only because of the multidimensionality. The Internet itself is not an easy research area. The online content is massive and some spaces are not easily reachable. Therefore, when researching the Internet, it is worth using various data sources and combining online research methods with more traditional ones—for example, searching for informants, in-depth interviews, etc. These also may prove useful for mapping digital religion.

Each of the indicated types of religion on the Internet was illustrated with examples of sites and tools to make it clearer how religion emerges online. However, I emphasize once again that the article does not aspire to be a list of digital religion spaces. Creating such a catalog would be a daunting task due to the massiveness of content and the dynamic nature of the Internet. Online tools present one day can change or simply disappear on the next one. The same with the sites presented here. However, this limitation is not significant given the aim of the article, which is to signal a need to continuously explore and develop conceptual frameworks for mapping religious content online. By pinpointing the four types of digital religion, the article is to be a signpost for those who want to research the intricate connections between religion and the Internet.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and input.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aeschbach, Mirjam, and Dorothea Lueddeckens. 2019. Religion on Twitter: Communalization in Event-Based Hashtag Discourses. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 14: 108–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apolito, Paolo. 2005. The Internet and the Madonna: Religious Visionary Experience on the Web, 1st ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baffelli, Erica, Ian Reader, and Birgit Staemmler, eds. 2010. Japanese Religions on the Internet: Innovation, Representation, and Authority. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bako, Rozalia, and Laszlo-Attila Hubbes. 2011. Religious Minorities’ Web Rhetoric: Romanian and Hungarian Ethno-Pagan Organizations. Journal for the Study of Religions and Ideologies 10: 127–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, Jamie. 2018. The People Vs Tech: How the Internet Is Killing Democracy (and How We Save It). New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Beckerlegge, Gwilym. 2001. Hindu Sacred Images for the Mass Market. In From Sacred Text to Internet. Edited by Gwilym Beckerlegge. Aldershot: Ashgate in Association with the Open University, pp. 57–116. [Google Scholar]

- Bittarello, Maria Beatrice. 2008. Contemporary Pagan Ritual and Cyberspace: Virtuality, Embodiment, and Mythopoesis. Religious Studies and Theology 27: 171–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolander, Brook, and Miriam A. Locher. 2020. Beyond the Online Offline Distinction: Entry Points to Digital Discourse. Discourse, Context & Media 35: 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowik, Claire. 2018. From Radical Communalism to Virtual CommunityThe Digital Transformation of the Family International. Nova Religio 22: 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasher, Brenda E. 2004. Give Me That Online Religion. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi. 2007. Who’s Got the Power? Religious Authority and the Internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 1043–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2010. Religious Authority and the Blogosphere. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 15: 251–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2012. Understanding the Relationship between Religion Online and Offline in a Networked Society. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 80: 64–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A., ed. 2013. Digital Religion, 1st ed. Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Heidi A. 2017. Surveying Theoretical Approaches within Digital Religion Studies. New Media & Society 19: 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A., and Giulia Evolvi. 2020. Contextualizing Current Digital Religion Research on Emerging Technologies. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Heidi A., and Alessandra Vitullo. 2016. Assessing Changes in the Study of Religious Communities in Digital Religion Studies. Church, Communication and Culture 1: 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, Manuel. 2000. The Rise of the Network Society, 2nd ed. Oxford and Malden: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, Pauline Hope, Shirlena Huang, and Jessie P. H. Poon. 2011. Cultivating Online and Offline Pathways to Enlightenment. Information, Communication & Society 14: 1160–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidester, David. 2005. Authentic Fakes: Religion and American Popular Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cloete, Anita L. 2016. Mediated Religion: Implications for Religious Authority. Verbum et Ecclesia 37: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, Curtis, and Julian Murchison. 2015. Network Apocalypsis: Revealing and Reveling at a New Age Festival. International Journal for the Study of New Religions 5: 167–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duteil-Ogata, Fabienne. 2015. New Funeral Practices in Japan. From the Computer-Tomb to the Online Tomb. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echchaibi, Nabil, Susanne Stadlbauer, Samira Rajabi, Giulia Evolvi, and Seung Soo Kim. 2013. Third Spaces, Religion and Spirituality in the Digital Age Panel 2. AoIR Selected Papers of Internet Research 3. Available online: https://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/spir/article/view/9069 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Evolvi, Giulia. 2020. Materiality, Authority, and Digital Religion: The Case of a Neo-Pagan Forum. Entangled Religions 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Dana R., and Larry Michael Wright. 2001. On Utopias and Dystopias: Toward an Understanding of the Discourse Surrounding the Internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 6: JCMC624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freberg, Karen, Kristin Graham, Karen McGaughey, and Laura A. Freberg. 2011. Who Are the Social Media Influencers? A Study of Public Perceptions of Personality. Public Relations Review 37: 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukamizu, Rev Kenshin. 2007. Internet Use Among Religious Followers: Religious Postmodernism in Japanese Buddhism. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 977–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, Alberta. 2019. Mediatized Catholicism—Minority Voices and Religious Authority in the Digital Sphere. Religions 10: 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goalwin, Gregory. 2021. Tweeted Heresies: Saudi Islam in Transformation, by ABDULLAH HAMIDADDIN. Sociology of Religion 82: 117–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomoliszek, Joanna, and Piotr Siuda. 2017. Słowem wstępu: Od protestu w sprawie polskich sądów do społecznej przestrzeni internetu. In Internet. Wybrane przykłady zastosowań i doświadczeń. Edited by Joanna Gomoliszek and Piotr Siuda. Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kazimierza Wielkiego, pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Grieve, Gregory Price. 1995. Imagining a Virtual Religious Community: Neo-Pagans and the Internet. Chicago Anthropology Exchange 7: 98–132. [Google Scholar]

- Grieve, Gregory Price. 2013. Religion. In Digital Religion. Edited by Heidi A. Campbell. Abingdon, Oxon and New York: Routledge, pp. 104–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grimmelmann, James. 2006. Virtual Borders: The Interdependence of Real and Virtual Worlds. First Monday. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, Damian. 2015. Discovering the Digital Authority: Twitter as Reporting Tool for Papal Activities. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 9: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, Paulina. 2018. Communicating Migration—Pope Francis’ Strategy of Reframing Refugee Issues. Church, Communication and Culture 3: 106–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helland, Christopher. 2000a. Online-Religion/Religion-Online and Virtual Communitas. In Religion on the Internet: Research Prospects and Promises. Edited by Jeffrey K. Hadden and Douglas E. Cowan. London: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 205–24. [Google Scholar]

- Helland, Christopher. 2000b. Religion on the Internet: Research Prospects and Promises. New York: JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helland, Christopher. 2005. Online Religion as Lived Religion. Methodological Issues in the Study of Religious Participation on the Internet. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet: Volume 01.1 Special Issue on Theory and Methodology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helland, Christopher. 2007. Diaspora on the Electronic Frontier: Developing Virtual Connections with Sacred Homelands. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 956–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helland, Christopher. 2015. Virtual Tibet: Maintaining Identity through Internet Networks. In The Pixel in the lotus: Buddhism, the Internet, and Digital Media. Edited by Gregory Price Grieve and Daniel Veidlinger. New York: Routledge, pp. 213–41. [Google Scholar]

- Helland, Christopher. 2016. Digital Religion. In Handbook of Religion and Society, Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Edited by David Yamane. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 177–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Smith, Connie. 2011. Cyberpilgrimage: The (Virtual) Reality of Online Pilgrimage Experience. Religion Compass 5: 236–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2008. The Mediatization of Religion: A Theory of the Media as Agents of Religious Change. Northern Lights: Film and Media Studies Yearbook 6: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjarvard, Stig. 2014. From Mediation to Mediatization: The Institutionalization of New Media. In Mediatized Worlds: Culture and Society in a Media Age. Edited by Andreas Hepp and Friedrich Krotz. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 123–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Stewart M. 2006. Religion in the Media Age, 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover, Stewart, and Nabil Echchaibi. 2015. The Third Spaces of Digital Religion. Available online: https://thirdspacesblog.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/third-spaces-and-media-theory-essay-2-0.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Horsfield, Peter. 2015. From Jesus to the Internet: A History of Christianity and Media. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, Tim. 2011. Contemporary Religious Community and the Online Church. Information, Communication & Society 14: 1118–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, Tim. 2017. Creating Church Online. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Stephen. 2007. Virtually Sacred: The Performance of Asynchronous Cyber-Rituals in Online Spaces. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 1103–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Simon. 2008. Rituals and Pixels. Experiments in Online Church. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinock, Sabine. 2006. Going on Pilgrimage Online: The Representation of Shia Rituals on the Internet. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaflogka, Anastasia. 2002. Religious Discourse and Cyberspace. Religion 32: 279–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawabata, Akira, and Takanori Tamura. 2007. Online-Religion in Japan: Websites and Religious Counseling from a Comparative Cross-Cultural Perspective. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 999–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kergel, David. 2020. The History of the Internet: Between Utopian Resistance and Neoliberal Government. In Handbook of Theory and Research in Cultural Studies and Education, Springer International Handbooks of Education. Edited by Peter Pericles Trifonas. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejska, Marta. 2018. Online Catholic Communities: Community, Authority, and Religious Individualization. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kołodziejska, Marta, and Anna Neumaier. 2017. Between Individualisation and Tradition: Transforming Religious Authority on German and Polish Christian Online Discussion Forums. Religion 47: 228–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozinets, Robert V. 2009. Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online, 1st ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, Paul. 2020. Fake News: Understanding Media and Misinformation in the Digital Age. Edited by Melissa Zimdars and Kembrew McLeod. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lindbekk, Tore. 1992. The Weberian Ideal-Type: Development and Continuities. Acta Sociologica 35: 285–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövheim, Mia. 2011. Mediatisation of Religion: A Critical Appraisal. Culture and Religion 12: 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövheim, Mia, and Gordon Lynch. 2011. The Mediatisation of Religion Debate: An Introduction. Culture and Religion 12: 111–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundby, Knut. 2012. Theoretical Frameworks for Approaching Religion and New Media. In Digital Religion: Understand Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. Edited by Christopher Helland. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 225–37. [Google Scholar]

- MacWilliams, Mark W. 2002. Virtual Pilgrimages on the Internet. Religion 32: 315–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacWilliams, Marc. 2006. Techno-Ritualization: The Gohozon Controversy on the Internet. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miczek, Nadja. 2008. Online Rituals in Virtual Worlds. Christian Online Service between Dynamics and Stability. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, Siti Mazidah Haji. 2018. Everyday Lived Islam: Malaysian Muslim Women’s Performance of Religiosity Online. Journal for Islamic Studies 37: 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narbona, Juan. 2016. Digital Leadership, Twitter and Pope Francis. Church, Communication and Culture 1: 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumaier, Anna. 2019. Christian Online Communities: Insights from Qualitative and Quantitative Data. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 14: 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noomen, Ineke, Stef Aupers, and Dick Houtman. 2011. In Their Own Image? Information, Communication & Society 14: 1097–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, Stephen D. 1996. Cyberspace as Sacred Space: Communicating Religion on Computer Networks. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 64: 781–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obadia, Lionel. 2015. When Virtuality Shapes Social Reality. Fake Cults and the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman, Carl, Robert Gorwa, and Luciano Floridi. 2019. Prayer-Bots and Religious Worship on Twitter: A Call for a Wider Research Agenda. Minds and Machines 29: 331–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parna, Karen. 2006. Believe in the Net: The Construction of the Sacred in Utopian Tales of the Internet. Implicit Religion 9: 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasecki, Stefan. 2018. VR Mediated Content and Its Influence on Religious Beliefs. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 13: 17–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piela, Anna. 2010. Muslim Women’s Online Discussions of Gender Relations in Islam. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 30: 425–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcu, Elisabetta. 2014. Pop Religion in Japan: Buddhist Temples, Icons, and Branding. The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 26: 157–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radde-Antweiler, Kerstin. 2008. Virtual Religion. An Approach to a Religious and Ritual Topography of Second Life. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rähme, Boris. 2018. Digital Religion, the Supermarket and the Commons. Societes 139: 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siuda, Piotr. 2010. Religia a internet: O przenoszeniu religijnych granic do cyberprzestrzeni. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Akademickie i Profesjonalnie. [Google Scholar]

- Siuda, Piotr. 2012. Sieć objawień. O pewnym wymiarze e-folkloru religijnego. Kultura Popularna 33: 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ridwan, Benny, Iswandi Syahputra, Azhari Akmal Tarigan, Fatahuddin Aziz Siregar, and Nofialdi Nofialdi. 2019. Islam Nusantara, Ulemas, and Social Media: Understanding the Pros and Cons of Islam Nusantara among Ulemas of West Sumatera. Indonesian Journal of Islam and Muslim Societies 9: 163–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammis, Kristy, Cat Lincoln, and Stefania Pomponi. 2015. Influencer Marketing for Dummies. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Scheifinger, Heinz. 2008. Hinduism and Cyberspace. Religion 38: 233–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheifinger, Heinz. 2010. Hindu Embodiment and the Internet. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, Rivka Neriya-Ben, and Azi Lev-On. 2011. Gender, Religion and New Media: Attitudes and Behaviors Related to the Internet Among Ultra-Orthodox Women Employed in Computerized Environments. International Journal of Communication 5: 21. [Google Scholar]

- Slama, Martin. 2018. Practising Islam through Social Media in Indonesia. Indonesia and the Malay World 46: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solahudin, Dindin, and Moch Fakhruroji. 2020. Internet and Islamic Learning Practices in Indonesia: Social Media, Religious Populism, and Religious Authority. Religions 11: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solatan, Agnes D. 2013. The Catholic Church and Internet Use: An Evolving Perspective from Pope John Paul II to Pope Benedict XVI. Ph.D. thesis, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Sorgenfrei, Simon. 2021. Crowdfunding Salafism. Crowdfunding as a Salafi Missionising Method. Religions 12: 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehle, Hanna. 2020. Russian Orthodox Clergy and Laity Challenging Institutional Religious Authority Online: The Case of Ahilla.Ru. Entangled Religions 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçalp, Deniz, and Patrick L. Lê. 2014. (Re)Locating Boundaries: A Systematic Review of Online Ethnography. Journal of Organizational Ethnography 3: 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Rachel. 2013. You Are What You Install: Religious Authenticity and Identity in Mobile Apps. In Digital Religion: Understanding Religious Practice in New Media Worlds. Edited by Howard Campbell. London: Routledge, pp. 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zaleski, Jeffrey P. 1997. The Soul of Cyberspace: How New Technology Is Changing Our Spiritual Lives, 1st ed. San Francisco: Harpercollins. [Google Scholar]

- Zijderveld, Theo. 2017. Pope Francis in Cairo—Authority and Branding on Instagram. Online—Heidelberg Journal of Religions on the Internet 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).