Alterations in Religious Rituals Due to COVID-19 Could Be Related to Intragroup Negativity: A Case of Changes in Receiving Holy Communion in the Roman Catholic Community in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Individual and Interpersonal Dimensions of Religiosity

1.2. Alteration of Rituals Due to the COVID-19 and Intragroup Conflict in the Religious Community

1.3. The Present Study

2. Study 1

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Participants and Procedure

2.1.2. Measures

- Intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientation: The age universal I-E scale-12 (Maltby 1999) was used to assess intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientation. The scale consists of 6 items measuring intrinsic religious orientation (e.g., “I try hard to live all my life according to my religious beliefs”) and 6 items measuring extrinsic religious orientation (e.g., “What religion offers me most is comfort in times of trouble and sorrow”). The reliability of the intrinsic religious orientation was α = 0.741, and the reliability of the extrinsic religious orientation was α = 0.811.

- Positive and negative emotions toward the religious community: We used five indicators of positive emotions toward the religious community (trust, care, closeness, commitment, and joy) and four indicators of negative emotions toward the religious community (anger, contempt, fear, sadness). The participants rated how frequently they felt such emotions toward their Church members on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (Very often). The principal factor analysis yielded a clear two-factor solution (explained variance = 61.455%), with the factors of positive emotions (loadings > 0.702) and negative emotions (loadings > 0.657). The reliability of positive emotions toward the religious community was α = 0.838, while the reliability of negative emotions toward the religious community was α = 0.747.

- Perceived legitimacy of Church authority: It was measured with three items adopted from Van der Toorn et al. (2015). The items were reworded and were as follows: “I feel I should accept the decisions made by my Church authorities, even when I think they are wrong”; “I think that it hurts my religious group when I disagree with my Church authorities”; and “I feel that it is wrong to ignore the instructions of my Church authorities even when I can get away with it”. The responses were made on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (Disagree strongly) to 4 (Agree strongly). The reliability of the measure was α = 0.823.

- In-group and out-group perceived religious orientation: The study participants were asked to rate how statements regarding intrinsic and extrinsic orientation to religion were characteristic of persons who received Holy Communion on the hand or in the mouth. These sentences were adopted from the Age Universal I-E scale-12 (Maltby 1999) and reworded in order to assess the perception of a particular group. The participants used a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (Very bad) to 4 (Very good), with the mid-point of 2 (Hard to tell). The reliability of each scale (intrinsic vs. extrinsic) for each target (on the hand vs. in the mouth) ranged from α = 0.857 (extrinsic orientation ascribed to the “hand only” group) to α = 0.947 (intrinsic orientation ascribed to the “hand only” group).

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Results

2.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.3.2. Group Membership and Emotional Reactions toward the Religious Community

2.3.3. Group Membership and Legitimacy of the Church Authority

2.3.4. Intergroup Bias in the Social Perception of Religiosity

2.4. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Participants and Procedure

3.1.2. Measures

- Opinions about the proper form of reception of Holy Communion: In order to assess the beliefs about the proper form of reception of Holy Communion, we asked the participants to indicate to what extent a particular form of receiving Holy Communion was proper, safe, and justified during the pandemic. The Likert-type scale used ranged from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Very much). We also asked the participants to make the same evaluations for other common preventive behaviors: Wearing masks and social distancing (Harper et al. 2020). Reliability of measures of appropriateness of these behaviors (receiving Holy Communion on the hand, in the mouth, wearing masks, and social distancing) was satisfactory, α > 0.850.

- Empathic responding toward a target person: We assessed two types of empathic emotional reactions toward a target person: Empathic concern (responding with compassion and tender feelings toward an observed person) and empathic distress (responding with own distress in response to negative and challenging situations faced by an observed person). In order to measure both emotional reactions, we used adjectives taken from Batson et al. (1987). Empathic concern was measured with the following emotions: Compassionate, softhearted, moved, and warm, while personal distress was measured with the following emotions: Upset, distressed, worried, and troubled. The participants were instructed to report how strongly they felt these emotions toward the target person described in a scenario using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Very strongly). Reliability of the empathic concern scale ranged from α = 0.719 to α = 0.817 in various experimental conditions. Reliability of the personal distress scale ranged from α = 0.876 to α = 0.912 in various experimental conditions.

- COVID-19-related fear: The Fear of COVID-19 Scale (Ahorsu et al. 2020) consists of seven items (e.g., “I am most afraid of Corona”; “It makes me uncomfortable to think about Corona”). The participants indicate their level of agreement with the statements using a five-item Likert-type scale ranged from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree). The reliability of the scale was α = 0.799 in the present study.

- Moral foundations: The Moral Foundations Questionnaire (Graham et al. 2011), Polish version: Jarmakowski-Kostrzanowski and Jarmakowska-Kostrzanowska (2016) consists of 30 items and asks the participant to what degree he or she agrees with five moral dimensions: Care/harm, fairness/cheating, authority/subversion, loyalty/betrayal, and sanctity/degradation. There are two sections in the questionnaire: Judgments and relevance. In the first one, the participants rate the importance of each of the criteria when they make moral judgments (e.g., “Whether or not someone did something to betray his or her group”). In the second, the participants rate the degree to which they agree with each of the moral judgments (e.g., “I think it’s morally wrong that rich children inherit a lot of money while poor children inherit nothing”). For each moral dimension, a composite score was formed by taking the average of six items (three items from the first section, three items from the second). Each subscale was reliable in the present study, 0.608 (fairness/cheating foundation) < α < 0.743 (sanctity/degradation foundation).

3.1.3. Procedure

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

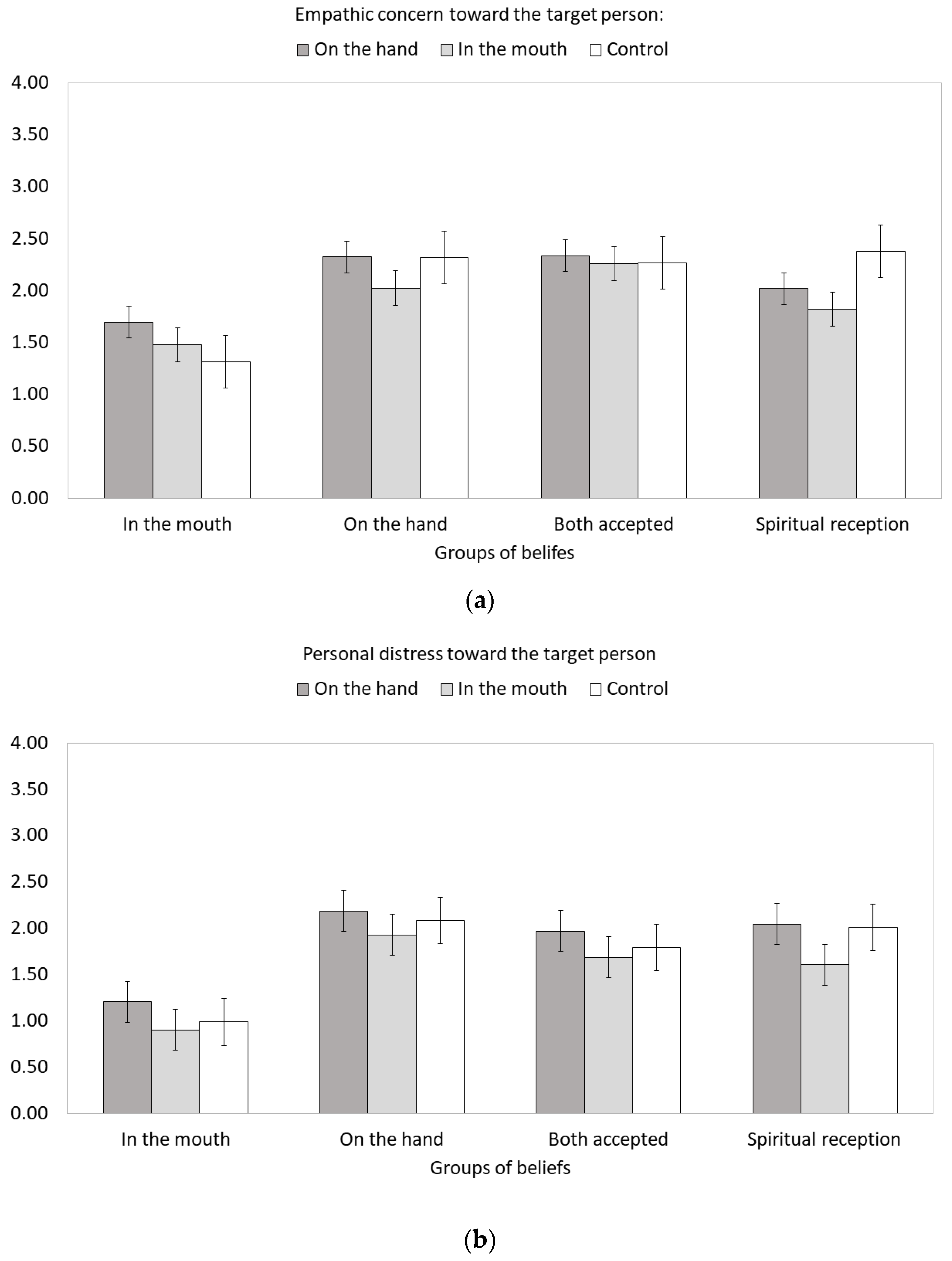

3.2.2. Empathy Bias

3.2.3. Moral Foundations and Fear of COVID-19 as Predictors of Opinions about the Proper Form of Receiving Holy Communion

3.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahorsu, Daniel Kwasi, Chung-Ying Lin, Vida Imani, Mohsen Saffari, Mark D. Griffiths, and Amir H. Pakpour. 2020. The fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and initial validation. Internationl Journal of Mental Health and Addictions, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, Gordon W., and Michael J. Ross. 1967. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C. Daniel, Jim Fultz, and Patricia A. Schoenrade. 1987. Distress and empathy: Two qualitatively distinct vicarious emotions with different motivational consequences. Journal of Personality 55: 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Catherine. 2009. Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 171–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bobrowicz, Ryszard, and Mattias Nowak. 2021. Divided by the Rainbow: Culture War and Diffusion of Paleoconservative Values in Contemporary Poland. Religions 12: 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cikara, Mina, Emile Bruneau, Jay J. Van Bavel, and Rebecca Saxe. 2014. Their pain gives us pleasure: How intergroup dynamics shape empathic failures and counter-empathic responses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 55: 110–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cikara, Mina, Emile G. Bruneau, and Rebecca R. Saxe. 2011. Us and them: Intergroup failures of empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science 20: 149–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Cory, Andrés Davila, Maxime Regis, and Sascha Kraus. 2020. Predictors of COVID-19 voluntary compliance behaviors: An international investigation. Global Transitions 2: 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, Jarret T. 2017. Are Conservatives More Sensitive to Threat than Liberals? It Depends on How We Define Threat and Conservatism. Social Cognition 35: 354–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, Carsten K. W., and Laurie R. Weingart. 2003. Task versus relationship conflict, team effectiveness, and team member satisfaction: A metaanalysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 741–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wit, Frank R. C., Lindred L. Greer, and Karen A. Jehn. 2012. The paradox of intragroup conflict: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 97: 360–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFranza, David, Mike Lindow, Kevin Harrison, Arul Mishra, and Himanshu Mishra. 2020. Religion and reactance to COVID-19 mitigation guidelines. American Psychologist. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demoulin, Stéphanie, Brezo P. Cortes, Tendayi G. Viki, Armando P. Rodriguez, Ramon T. Rodriguez, Maria P. Paladino, and Jacques-Philippe Leyens. 2009. The role of in-group identification in infra-humanization. International Journal of Psychology 44: 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deon.pl. 2020. Controversial Action “Stop Receiving Holy Communion to the Hands. There Are First Commentaries. Available online: https://deon.pl/kosciol/kontrowersyjna-akcja-stop-komunii-swietej-na-reke-sa-pierwsze-komentarze,1006332 (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Duan, Li, and Gang Zhu. 2020. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7: 300–02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, Fletcher, Rolf Verres, and Jan Weinhold. 2010. Regarding Ritual Motivation Matters: Agency Concealed or Revealed. In Ritual Matters. Dynamic Dimensions in Practice. Edited by Christine Brosius and Ute Hüsken. London: Routladge, pp. 253–69. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., Kenneth I. Pargament, Joshua B. Grubbs, and Ann M. Yali. 2014. The Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale: Development and initial validation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6: 208–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falbo, Toni B., Lynn New, and Margie Gaines. 1987. Perceptions of authority and the power strategies used by clergymen. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 26: 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, Franz, Eegar Erdfelder, Albert-Georg Lang, and Axel Buchner. 2007. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods 39: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- General Instruction of the Roman Missal. 2021. Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. General Instruction of the Roman Missal. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/ccdds/documents/rc_con_ccdds_doc_20030317_ordinamento-messale_en.html (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Gorsuch, Richard L. 1988. Psychology of religion. Annual Review of Psychology 39: 201–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Jesse, and Jonathan Haidt. 2010. Beyond beliefs: Religions bind individuals into moral communities. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 140–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, Jesse, Brian A. Nosek, Jonathan Haidt, Ravi Iyer, Spassena Koleva, and Peter H. Ditto. 2011. Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 101: 366–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, Ronald L. 1990. Ritual Criticism: Case Studies in Its Practice. Essays on Its Theory. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hadarics, Márton, and Anna Kende. 2018. Moral foundations of positive and negative intergroup behavior: Moral exclusion fills the gap. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 64: 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Deborah L., Adam B. Cohen, Kaitlin K. Meyer, Allison H. Varley, and Gene A. Brewer. 2015. Costly signaling increases trust, even across religious affiliations. Psychological Science 26: 1368–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, Craig A., Liam P. Satchell, Dean Fido, and Robert D. Latzman. 2020. Functional Fear Predicts Public Health Compliance in the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 27: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, Nick, and Steve Loughnan. 2014. Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annual Review of Psychology 65: 399–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewstone, Miles, Mark Rubin, and Hazel Willis. 2002. Intergroup bias. Annual Review of Psychology 53: 575–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, Nicholas M., Juliana Schroeder, Jane L. Risen, Dimitris Xygalatas, and Michael Inzlicht. 2018. The psychology of rituals: An integrative review and process-based framework. Personality and Social Psychology Review 22: 260–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, Emily A., Rory C. O’Connor, V. Hugh Perry, Irene Tracey, Simon Wessely, Louise Arseneault, Clive Ballard, Helen Christensen, Roxane C. Silver, Ian Everall, and et al. 2020. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 7: 547–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, John A. 2001. Self-esteem and in-group bias among members of a religious social category. The Journal of Social Psychology 141: 401–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüsken, Ute, and Frank Neubert. 2012. Introduction. In Negotiating Rites. Edited by Ute Hüsken and Frank Neubert. Oxford: Oxford University, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hüsken, Ute. 2007. Ritual dynamics and ritual failure. In When Rituals Go Wrong: Mistakes, Failure, and the Dynamics of Ritual. Edited by Ute Hüsken. Leiden: Brill, pp. 337–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Lynne M., and Bruce Hunsberger. 1999. An intergroup perspective on religion and prejudice. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 38: 509–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarmakowski-Kostrzanowski, Tomasz, and Lilianna Jarmakowska-Kostrzanowska. 2016. Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza Fundamentów Moralnych (MFQ-PL). Psychologia Społeczna 39: 489–508. [Google Scholar]

- Jehn, Karen A. 1997. Qualitative analysis of conflict types and dimensions in organizational groups. Administrative Science Quarterly 42: 530–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Megan K., Wade C. Rowatt, and Jordan LaBouff. 2012. Priming Christian religious concepts increases racial prejudice. Social Psychological and Personality Science 1: 119–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, Sudhir. 2010. The uses of ritual. In Ritual Matters. Dynamic Dimensions in Practice. Edited by Christine Brosius and Ute Hüsken. London: Routladge, pp. 201–9. [Google Scholar]

- Karwowski, Maciej, Marta Kowal, Agata Groyecka, Michał Białek, Izabela Lebuda, Agnieszka Sorokowska, and Piotr Sorokowski. 2020. When in danger, turn right: Does Covid-19 threat promote social conservatism and right-wing presidential candidates? Human Ethology 35: 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, Neal, Linda M. Chatters, Tina Meltzer, and David L. Morgan. 2000. Negative interaction in the Church: Insights from focus groups with older adults. Review of Religious Research 41: 510–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBouff, Jordan P., Wade C. Rowatt, Megan K. Johnson, and Callie Finkle. 2012. Differences in attitudes toward outgroups in religious and nonreligious contexts in a multinational sample: A situational context priming study. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 22: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyens, Jacques-Philippe. 2009. Retrospective and Prospective Thoughts About Infrahumanization. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 12: 807–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Wen-Qiao, Liman M.W. Li, Da Jiang, and Shuang Liu. 2020. Fate control and ingroup bias in donation for the fight with the coronavirus pandemic: The mediating role of risk perception of COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences 171: 110456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltby, John. 1999. The internal structure of a derived, revised, and amended measure of the Religious Orientation Scale: The ‘Age-Universal’ I-E Scale-12. Social Behavior and Personality 27: 407–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, John. 2002. The Age Universal I-E Scale-12 and orientation toward religion: Confirmatory factor analysis. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied 136: 555–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, Frances. 1997. The Influence of the Catholic Hierarchy in Poland, 1989-96. Journal of European Social Policy 7: 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirosławska, Monika, and Mirosław Kofta. 2007. The infrahumanization phenomenon: A preliminary test of the generalization-of-the self explanation. Psychologia Społeczna 3: 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Obst, Patricia, and Naomi Tham. 2009. Helping the soul: The relationship between connectivity and well-being within a church community. Journal of Community Psychology 37: 342–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, Helen. 2020. The absence of presence and the presence of absence: Social distancing, sacraments, and the virtual religious community during the COVID-19 pandemic. Religions 11: 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Episcopal Conference. 2005. Communiqué from the 331th Plenary Meeting of the Polish Episcopal Conference. Available online: https://episkopat.pl/komunikat-z-331-zebrania-plenarnego-konferencji-episkopatu-polski/ (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Polish Episcopal Conference. 2020a. The Permanent Council of the Polish Episcopate Recommends Precautions in Churches Regarding Coronavirus. Available online: https://episkopat.pl/the-permanent-council-of-the-episcopate-recommends-precautions-in-churches-regarding-coronavirus (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Polish Episcopal Conference. 2020b. Communication of the Commission for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments. Available online: https://opoka.news/komunikat-komisji-ds-kultu-bozego-i-dyscypliny-sakramentow (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Preston, Jesse L., Ryan S. Sitter, and J. Ivan Hernandez. 2010. Principles of religious prosociality: A review and reformulation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 4: 574–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Kun, and T. Tetsukazu Yahara. 2020. Mentality and behavior in COVID-19 emergency status in Japan: Influence of personality, morality and ideology. PLoS ONE 15: e0235883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riek, Blake M., Eric W. Mania, and Samuel L. Gaertner. 2006. Intergroup threat and outgroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review 10: 336–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowatt, Wade C., and Rosemary L. Al-Kire. 2021. Dimensions of religiousness and their connection to racial, ethnic, and atheist prejudices. Current Opinion in Psychology 40: 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saroglou, Vassilis. 2006. Religion’s role in prosocial behavior: Myth or reality? Psychology of Religion Newsletter 31: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skitka, Linda J., Christopher W. Bauman, and Brad L. Lytle. 2009. Limits on legitimacy: Moral and religious convictions as constraints on deference to authority. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97: 567–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosis, Richard, and Condace Alcorta. 2003. Signaling, solidarity, and the sacred: The evolution of religious behavior. Evolutionary Anthropology 12: 264–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosis, Richard. 2005. Does religion promote trust? The role of signaling, reputation, and punishment. Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 1: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Daniel H., Nicholas M. Hobson, and Juliana Schroeder. 2021a. A sacred commitment: How rituals promote group survival. Current Opinion in Psychology 40: 114–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Daniel H., Juliana Schroeder, Nicholas M. Hobson, Francesca Gino, and Michael I. Norton. 2021b. When alterations are violations: Moral outrage and punishment in response to (even minor) alterations to rituals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkowski, Lukasz, and Grzegorz Ignatowski. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on organization of religious behaviour in different Christian denominations in Poland. Religions 11: 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, Lawton K, Martin Heesacker, Daniel J. Snipes, and Paul B. Perrin. 2014. Social Perceptions of Religiosity: Dogmatism Tarnishes the Religious Halo. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 24: 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Edited by Stephen Worschel and William G. Austin. Monterey: Brooks/Cole, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Topidi, Kyriaki. 2019. Religious Freedom, National Identity, and the Polish Catholic Church: Converging Visions of Nation and God. Religions 10: 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Toorn, Jojanneke, Matthew Feinberg, John T. Jost, Aaron C. Kay, Tom R. Tyler, Robb Willer, and Caroline Wilmuth. 2015. A Sense of Powerlessness Fosters System Justification: Implications for the Legitimation of Authority, Hierarchy, and Government. Political Psychology 36: 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatican News. 2020. Covid-19. Vatican Holy Week Celebrations under Study. Available online: https://www.vaticannews.va/en/vatican-city/news/2020-03/vatican-coronavirus-easter-triduum-celebrations.html (accessed on 19 April 2020).

- Verkuyten, Maykel. 2007. Religious Group Identification and Inter-Religious Relations: A Study Among Turkish-Dutch Muslims. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 10: 341–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Stephen X., Yifei Wang, Andreas Rauch, and Feng Wei. 2020. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Research 288: 112958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubrzycki, Geneviève. 2020. Quo Vadis, Polonia? On religious loyalty, exit, and voice. Sociological Compass 67: 267–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Intrinsic RO | |||||||||

| 2. Extrinsic RO | 0.328 *** | ||||||||

| 3. PA | 0.315 *** | 0.414 *** | |||||||

| 4. NA | −0.031 | 0.092 | −0.125 | ||||||

| 5. LCA | 0.306 *** | 0.219 * | 0.271 *** | −0.134 | |||||

| 6. ”hand only” (IRO) | 0.259 *** | 0.247 *** | 0.191 ** | 0.053 | 0.245 *** | ||||

| 7. “hand only” (ERO) | 0.211 ** | 0.532 *** | 0.271 *** | 0.024 | 0.150 * | 0.507 *** | |||

| 8. “mouth only” (IRO) | 0.266 *** | 0.402 *** | 0.356 *** | −.040 | 0.160 * | 0.669 *** | 0.466 *** | ||

| 9. “mouth only” (ERO) | 0.139 | 0.469 *** | 0.188 *** | 0.091 | 0.115 | 0.509 *** | 0.576 *** | 0.654 *** | |

| M | 3.376 | 2.183 | 2.301 | 1.641 | 2.426 | 2.662 | 2.276 | 2.809 | 2.443 |

| SD | 0.539 | 0.884 | 0.876 | 0.982 | 1.153 | 0.845 | 0.697 | 0.832 | 0.784 |

| Age | 0.234 ** | −0.051 | 0.289 *** | −0.002 | 0.049 | 0.089 | −0.034 | 0.108 | 0.026 |

| Gender | 0.145 * | 0.181 * | 0.016 | 0.045 | 0.095 | 0.247 *** | 0.111 | 0.076 | 0.147 * |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empathic concern toward “on the hand” (target person) | ||||||

| Personal distress toward “on the hand” (target person) | 0.492 | |||||

| Empathic concern toward “in the mouth” (target person) | 0.778 | 0.368 | ||||

| Personal distress toward “in the mouth” (target person) | 0.438 | 0.841 | 0.477 | |||

| Empathic concern toward “control” (target person) | 0.867 | 0.510 | 0.835 | 0.506 | ||

| Personal distress toward “control” (target person) | 0.451 | 0.942 | 0.375 | 0.869 | 0.526 | |

| M | 2.242 | 1.975 | 2.028 | 1.687 | 2.161 | 1.844 |

| SD | 0.880 | 1.116 | 0.992 | 1.155 | 0.984 | 2.000 |

| α | 0.719 | 0.876 | 0.817 | 0.911 | 0.816 | 0.912 |

| Effect | Num DF | Den DF | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1 | 167 | 6.178 | 0.010 |

| Age | 1 | 167 | 3.879 | 0.051 |

| Beliefs about the proper form of reception of Holy Communion (BPHC) | 3 | 167 | 5.662 | 0.001 |

| Target person in a vignette (TPV) | 2 | 334 | 2.543 | 0.080 |

| TPV × Gender | 2 | 334 | 0.012 | 0.883 |

| TPV × Age | 2 | 334 | 0.969 | 0.380 |

| TPV × BPHC | 6 | 334 | 3.217 | 0.004 |

| Empathic response (ER: EC vs. PD) | 1 | 167 | 4.291 | 0.040 |

| ER × Gender | 1 | 167 | 3.054 | 0.082 |

| ER × Age | 1 | 167 | 0.014 | 0.907 |

| ER × BPHC | 3 | 167 | 1.410 | 0.241 |

| TPV × ER | 2 | 334 | 2.396 | 0.093 |

| TPV x ER × Gender | 2 | 334 | 2.371 | 0.095 |

| TPV × ER × Age | 2 | 334 | 2.037 | 0.013 |

| TPV × ER × BPHC | 6 | 334 | 2.367 | 0.030 |

| Predictor | Wearing Masks | Social Distancing | Holy Communion on the Hand | Holy Communion in the Mouth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | sr2 | β | sr2 | β | sr2 | β | sr2 | |

| Gender | −0.050 | 0.002 | −0.092 | 0.007 | 0.086 | 0.006 | 0.110 | 0.010 |

| Age | 0.067 | 0.004 | 0.096 | 0.008 | 0.046 | 0.002 | 0.105 | 0.010 |

| Fear | 0.287 *** | 0.076 | 0.316 *** | 0.092 | 0.155 * | 0.022 | −0.345 *** | 0.110 |

| Care/harm | 0.367 *** | 0.077 | 0.264 *** | 0.040 | 0.146 | 0.012 | −0.257 ** | 0.038 |

| Fairness/cheating | −0.095 | 0.005 | −0.091 | 0.005 | 0.045 | 0.001 | −0.123 | 0.009 |

| Loyalty/betrayal | −0.194 | 0.018 | −0.088 | 0.004 | −0.146 | 0.010 | 0.110 | 0.006 |

| Authority/subversion | 0.198 | 0.016 | 0.095 | 0.004 | −0.135 | 0.007 | 0.151 | 0.009 |

| Sanctity/degradation | −0.187 | 0.019 | −0.190 | 0.019 | −0.104 | 0.006 | 0.207 * | 0.023 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moroń, M.; Biolik-Moroń, M.; Matuszewski, K. Alterations in Religious Rituals Due to COVID-19 Could Be Related to Intragroup Negativity: A Case of Changes in Receiving Holy Communion in the Roman Catholic Community in Poland. Religions 2021, 12, 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040240

Moroń M, Biolik-Moroń M, Matuszewski K. Alterations in Religious Rituals Due to COVID-19 Could Be Related to Intragroup Negativity: A Case of Changes in Receiving Holy Communion in the Roman Catholic Community in Poland. Religions. 2021; 12(4):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040240

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoroń, Marcin, Magdalena Biolik-Moroń, and Krzysztof Matuszewski. 2021. "Alterations in Religious Rituals Due to COVID-19 Could Be Related to Intragroup Negativity: A Case of Changes in Receiving Holy Communion in the Roman Catholic Community in Poland" Religions 12, no. 4: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040240

APA StyleMoroń, M., Biolik-Moroń, M., & Matuszewski, K. (2021). Alterations in Religious Rituals Due to COVID-19 Could Be Related to Intragroup Negativity: A Case of Changes in Receiving Holy Communion in the Roman Catholic Community in Poland. Religions, 12(4), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040240