Religious Print in Settler Australia and Oceania

Abstract

1. Australia’s Printed Public

2. Settler Australian Religious Print Importation

3. Settler English Language Religious Print

4. Settler Indigenous Language Religious Print

5. Religion after Print

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The essay inverted the title of an essay he had published ten years prior which explored similar options (Smith 2009, p. 5, citing; Smith [1999] 2004). Both essays acknowledge the prior work of Wilfred C. Smith who examined the possibility of a similar historical study of religious texts along these lines (Smith 1971). |

| 2 | Barker is a legal scholar who has suggested that Australian secularism is closest to Charles Taylor’s third definition in A Secular Age (Taylor 2007, p. 203). That is, not a complete removal of God and religion from the public sphere, nor reduction of religious belief in the general population, but rather, where “religion… is just once voice among many, including those with no religion” (Barker 2015). |

| 3 | This difficulty is reiterated in the opening remarks in Chavura, Gascoigne and Tregenza’s Reason, Religion and the Australian Polity, where renewed scholarly debate about the visibility of “public religion” is discussed primarily in terms of the institutional relation between “’religion’ and the modern state.” (Chavura et al. 2019, p. 4). The approach taken here aims to complement existing research by providing a concrete example of how print provided material context to publicize religion in a public sphere. For a wider discussion of the ways the public private distinction can be applied to religion, see José Casanova’s Public Religions in the Modern World, (Casanova 1994, pp. 41–42). |

| 4 | Habermas dates the English language notion of public opinion to 1781 in the Oxford English Dictionary (Habermas [1962] 1989, p. 95). He also acknowledges that the idea of the public varied in philosophical treatises by Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Immanuel Kant (Habermas [1962] 1989, pp. 90–106). Nonetheless, his reliance on Kant’s “What is Enlightenment?” (Kant [1784] 1996) is particularly telling: “Each person was called to be a ‘publicist,’ a scholar ‘whose writings speak to his public, the world’” (Habermas [1962] 1989, p. 106). |

| 5 | The context was inevitably mixed in its use of texts over this period, and print was not a deterministic fate, so much as part of what Elizabeth Eisenstein calls, a “change of phase” in how these communication practices came to interact with each other (Eisenstein 2005, p. 332). It should also be noted that orality persisted alongside this diversity of printed materials. Many published sermons apologized for their lack of a preacher’s presence (McKenzie 2002, p. 241). As Andrew Pettegree has noted, in his recent Brand Luther, the reformer cultivated a kind of publicity and fame both as a preacher and in his printed work (Pettegree 2015, Loc 69). Nonetheless, book historians such as Chartier demonstrate an overall increase in engagement with various forms of reading and writing practices over the seventeenth and eighteenth-centuries (Chartier 2003b, pp. 111–16). |

| 6 | Despite their differences, early Protestant and Counter-Reformation Catholics of the sixteenth and seventeenth-centuries both emphasized the importance of preaching as well as liturgical practices. Each developed new ways for private religious community to develop in this era. As Lebrun notes, “both the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation played key roles in the internalization of piety” (Lebrun 2003, p. 109). |

| 7 | The details of specific Pietist doctrines or thought are beyond this essay’s focus upon the way their view of inner religious life relied on printed publications practices. They paradoxically publicized that view in a way that made religion more visible in the public sphere of printed communications. For a more full discussion of these relationships in the English context see (Green 2000). |

| 8 | For a summary of Wesley’s Pietist thought, see (Hempton 2004, pp. 257–72). |

| 9 | While Australian history of the book is well underway (Munro and Sheahan-Bright 2006; Lyons and Arnold 2001; Kirsop 1969; Kirsop 1988), less emphasis has been placed on religious texts. Research on the relationship between European importation and Australian printing was commenced by Wallace Kirsop (Kirsop 1962, 1969, p. 19). As Kirsop noted, Australia’s distance from Europe meant that it began producing its own printed materials much earlier than other colonial contexts such as Canada. As he put it at one point, ‘Isolation, then, is the initial impulse towards creating a printing industry’ (Kirsop 1969, p. 12). |

| 10 | None are included in John Ferguson’s multivolume Bibliography of Australia (Ferguson 1941, 1948, 1951, 1955, 1963–1969), nor are any listed in the first volume of the Historical Catalogue of the Printed Editions of the Holy Scripture in the British and Foreign Bible Society (British and Foreign Bible Society 1903–1911), which lists all English editions. |

| 11 | The details of these events have been summarized in more detail in Robb’s biography George Howe: Australia’s First Publisher (Robb 2003, pp. 14–19). For instance, it is worth noting that George had been sentenced to death for shoplifting. That sentence was commuted to transportation to Australia. |

| 12 | Blair also notes that George “served on committees and printed the records of groups such as the New South Wales Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and Benevolence, the New South Wales Sunday School Institution the Auxiliary Bible Society of new South Wales and Wesleyan Auxiliary Missionary Society” (Blair 1985, pp. 16–17). |

| 13 | Carey estimates that by 1871 Methodists made up 9.7% of the population of New South Wales and by the turn of the twentieth-century did not exceed 10% of the population. Wright and Clancy conclude, “By 1902 there were twenty-seven circuits and 2036 members, though the church had peaked in 1894–1895 with twenty-nine ministers, 142 local preachers, 2187 members and 7296 Sunday school scholars” (Wright and Clancy 1993, p. 52). |

| 14 | To reiterate, the aim of this paper is to demonstrate key features of early Australian print culture that fit Habermas’s outline of a public sphere. It is in this sense an ideal, with varying degrees expression in debate, readership and publication practices. |

| 15 | As D. F. McKenzie commented with regard to the New Zealand context, the vernacular literacy aims of the missionaries were driven by complex interests. “The missionaries were all too well aware that English would give the Maori access to the worst aspects of European experience. By containing them culturally within their own language, they hoped to keep them innocent of imported evils. By restricting them further to the reading of biblical texts and vocabulary, they limited the Maori to knowledge of an ancient middle-eastern culture; at the same time the missionaries enhanced their familiar pastoral role by making the Maori dependent on them morally and politically as interpretative guides to Pakeha realities” (McKenzie 1999, p. 84). |

| 16 | The issue of the Sydney Gazette cited, discusses missionary practices to Tahiti and notes the following, “By direction of the Rev. Mr. Marsden, several Scriptural translations have been printed here and are in readiness to be conveyed thither as soon as an opportunity shall offer” (Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser 1814). This citation is also included in Ferguson’s notes. |

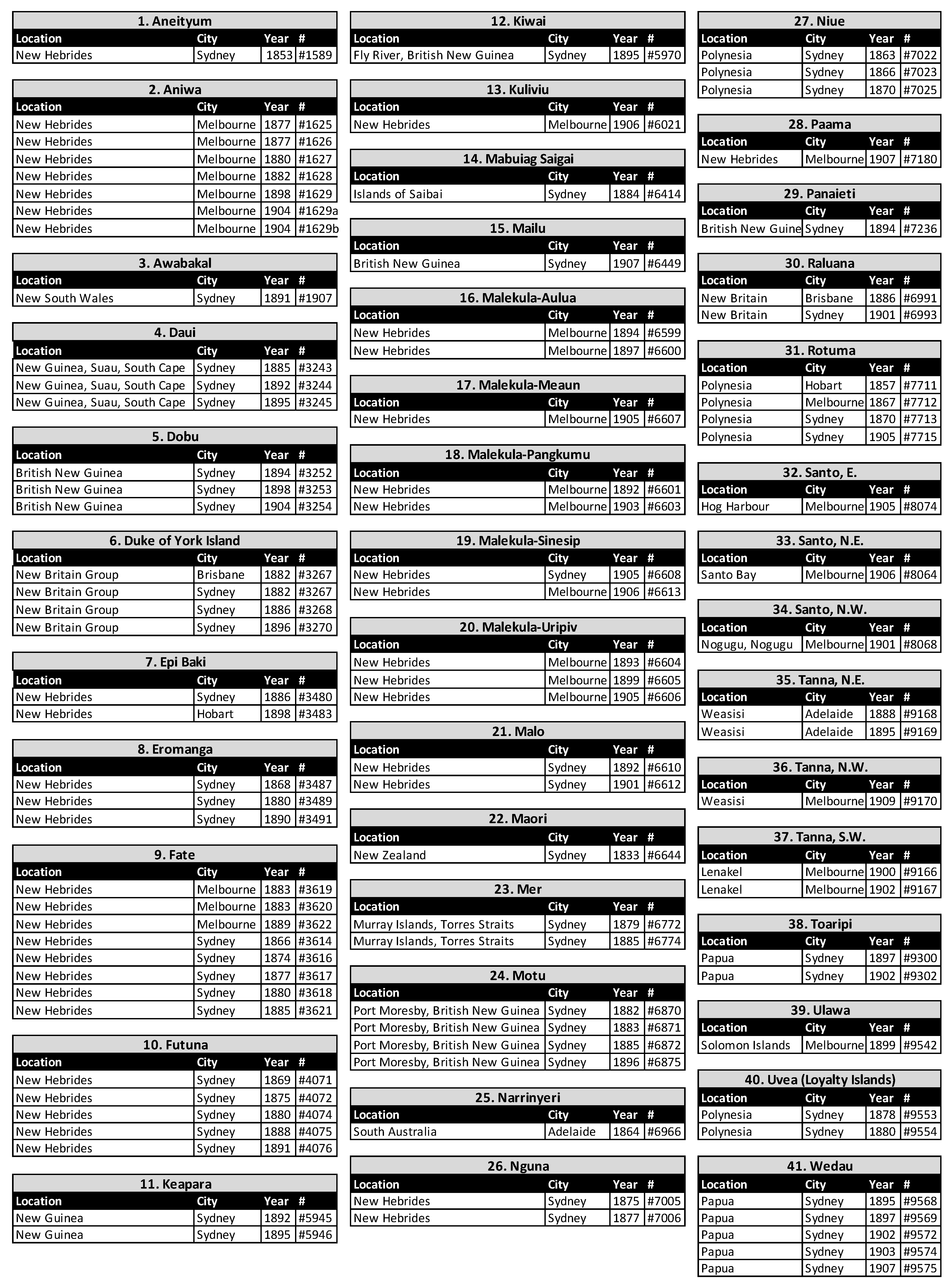

| 17 | The first printed Christian scriptures in North America were of a New Testament translation of the Indigenous Algonquin language dialect of the Wôpanâak people living in Massachusetts. It is known as the Wampanoag Bible and alternatively the Eliot Bible after its translator John Eliot (Wusku Wuttestamentum Nul-Lordumun Jesus Christ nuppoquohwussuaeneumun 1661). The complete Bible in the same language was published two years later in 1663. A discussion of the latter text can be found in Hamel’s The Book: A History of the Bible (Hamel 2001, pp. 270–74). While Hamel briefly discusses translations into Fijian, Tahitian and Maori (Hamel 2001, pp. 291–94), but makes no mention of Australian printing practices nor Australia’s Indigenous languages. |

| 18 | The Historical Catalogue of the Printed Editions of the Holy Scripture in the British and Foreign Bible Society lists an entry for the year 1833, with notes concerning its 1827 publication in Sydney (British and Foreign Bible Society 1903–1911, p. 1071). |

| 19 | One of the first printed Maori language texts was produced in 1815 as a spelling primer, entitled ed: “A Korao no New Zealand; /or, the/New Zealander’s First Book; /being/An Attempt to compose some Lessons for the/Instruction of the Natives” (Parr 1961, 429; citing Williams 1924). As D. F. McKenzie noted, the first printing press arrived in New Zealand in 1830 (McKenzie 1999, p. 96). |

| 20 | This would be roughly 3405.80 pounds today, as calculated at: https://www.officialdata.org/uk/inflation/1800?amount=41. (accessed on 2 February 2019). |

| 21 | At the University of Newcastle we acknowledge the Awabakal people as the traditional owners of the land upon which we work, and pay respect to the Elders past, present and future. |

| 22 | In both the Tahitian and Maori cases, Ferguson also records early hymns and catechism publications (Ferguson 1941, p. 241 [Tahitian Catechism], p. 241 [Tahitian Language Primer], p. 253, [Tahitian Hymns], p. 249 [Maori Language Primer], p. 416 [Maori Wesleyan Catechism], p. 495 [Maori Scripture Portions, Prayers, Catechism and Hymns]). |

| 23 | For another example listing printed Indigenous translations see Bernard Pick’s (1913) American Bible Society pamphlet, Translations of the Bible: A Chronology of the Versions of the Holy Scriptures Since the Invention of Printing, which lists Tahitian in 1818 and Maori in 1833. Awabakal is listed in 1891. |

| 24 | A summary of the literacy rate in relation to religious and economic backgrounds around the time of the influx of immigration in 1841 can be found in (Richards 1999, p. 347). |

| 25 | The mosque is now a museum heritage site. ‘Broken Hill Mosque Museum’, Broken Hill City Council, at <https://www.brokenhill.nsw.gov.au/Community/About-the-city/Outback-Museum-Stories/Broken-Hill-Mosque-Museum>. Accessed on 6 January 2021. |

| 26 | The earliest printed Qur’an in Arabic dates from “around 1537 in Venice,” with the Pope’s sanction of other Arabic translation projects (Atiyeh 1995, 2050-51n1). The earliest Islamic bans on print in the Ottoman context date from 1482 and were not lifted until 1727 (Albin 2007, p. 170). Lithography fostered more accurate preservation of manuscript aesthetics in Arabic. The first edition of the Qur’an was produced in Iran in 1832–33, when beloved nastaliq calligraphy script was able to be reproduced more beautifully. By 1848 in India’s state of Oudh, lithography became known as a “Muslim technology” (Albin 2007, p. 174). |

| 27 | The earliest translation into English was in 1649 by Alexander Ross. The second English translation was by George Sale in 1734 (Robinson 1993, pp. 229–51). An early 1734 example of Sale’s text exists in the State Library of New South Wales Richardson Collection. |

| 28 | As noted above, examples of Wôpanâak language sacred texts in the North American context are now held in the Huntington Library and feature in art gallery displays. They are also oft cited in the revival of that once extinct language. The Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project cites a page from the 1663 Bible on the homepage of its website: https://www.wlrp.org. (Homepage 2021). It is hoped that the research and table produced here may inspire similar work in the Australian, New Zealand and Oceania contexts. |

References

- Adams, Thomas, and Nicolas Barker. 2001. A New Model for the Study of the Book. In A Potencie of Life: Books in Society. Edited by Nicholas Barker. London: British Library, pp. 5–44. [Google Scholar]

- Albin, Michael. 2007. The Islamic Book. In A Companion to the History of the Book. Edited by Simon Eliot and Jonathan Rose. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 165–76. [Google Scholar]

- Atiyeh, George N. 1995. The Book in the Modern Arab World: The Cases of Lebanon and Egypt. In The Book in the Islamic World: The Written Word and Communication in the Middle East. Edited by George N. Atiyeh. Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 233–54. [Google Scholar]

- Auxiliary Bible Society of New South Wales. 1822–1823. Sixth and Seventh Reports, Sydney.

- Baker, Keith. 1996. Defining the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century France: Variations on a Theme by Habermas. In Habermas and the Public Sphere. Edited by Craig Calhoun. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 181–211. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, Renae. 2015. Is Australia a Secular Country? It Depends What You Mean. The Conversation. May 14. Available online: http://theconversation.com/is-australia-a-secular-country-it-depends-what-you-mean-38222 (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Blair, Sandy. 1985. George Howe and Early Printing in New South Wales. In Wayzgoose One. Pyrmont: Wayzgoose Press, pp. 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Borchardt, Dietrich Hans. 1988. Printing Comes to Australia. In The Book in Australia: Essays towards a Cultural and Social History. Edited by D. H. Borchardt and Wallace Kirsop. Melbourne: Australian Reference Publications in Association with the Centre for Bibliographical and Textual Studies, pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- British and Foreign Bible Society. 1903–1911. Historical Catalogue of the Printed Editions of the Holy Scripture in the British and Foreign Bible Society. London: The Bible House, vols. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Canton, William. 1904. A History of the British and Foreign Society. London: John Murray, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, Hilary M. 2010. Lancelot Threlkeld, Biraban, and the Colonial Bible in Australia. Comparative Studies in Society and History 52: 447–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, Hilary M. 2011. God’s Empire: Religion and Colonialism in the British World, C.1801–1908. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, José. 1994. Public Religions in the Modern World. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh, William. 2009. The Myth of Religious Violence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier, Roger. 2003a. Figures of Modernity: Introduction. In A History of Private Life: Passions of the Renaissance. Edited by Roger Chartier. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, vol. 3, pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier, Roger. 2003b. The Practical Impact of Writing. In A History of Private Life: Passions of the Renaissance. Edited by Roger Chartier. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, vol. 3, pp. 111–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chavura, Stephen A., and Ian Tregenza. 2015. A Political History of the Secular in Australia: 1788–1945. In Religion after Secularization in Australia. Edited by Timothy Stanley. New York: Palgrave, pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chavura, Stephen A., John Gascoigne, and Ian Tregenza. 2019. Reason, Religion and the Australian Polity. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Darnton, Robert. 1990. What is the History of Books? In The Kiss of Lamourette: Reflections in Cultural History by Robert Darnton. New York: Norton, pp. 107–35. [Google Scholar]

- Darnton, Robert. 1999. The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. 2005. The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eliot, Simon, and Jonathan Rose, eds. 2007. A Companion to the History of the Book. Malden: Blackwell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, John Alexander. 1941. Bibliography of Australia. Vol. 1: 1784–1830. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, John Alexander. 1948. Bibliography of Australia. Vol. 2: 1831–1838. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, John Alexander. 1951. Bibliography of Australia. Vol. 3: 1839–1845. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, John Alexander. 1955. Bibliography of Australia. Vol. 4: 1846–1850. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, John Alexander. 1963–1969. Bibliography of Australia. Vols. 5–7: 1851–1900. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, David, and Alistair McCleery. 2005. An Introduction to Book History. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gascoigne, John. 2002. The Enlightenment and the Origins of European Australia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Ian. 2000. Print and Protestantism in Early Modern England. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. London: Polity Press. First published 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, Christopher de. 2001. The Book: A History of the Bible. London: Phaidon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hempton, David. 2004. John Wesley (1703–1791). In The Pietist Theologians: An Introduction to Theology in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Edited by Carter Lindberg. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 256–72. [Google Scholar]

- Homepage. 2021. Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project. Available online: https://www.wlrp.org (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Howe, George. 1821a. Advertisement. In An Abridgment of the Wesleyan Hymns Selected from the Larger Hymn-Book, Published in England, for the Use of the People Called Methodist. Sydney: Printed by George Howe. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, Robert. 1821b. Preface [to the December Index of the Complete First Volume]. In The Australian Magazine: Or, Compendium of Religious, Literary, and Miscellaneous Intelligence. Sydney: Printed by Robert Howe, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Howsam, Leslie. 2014. The Cambridge Companion to the History of the Book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Anna. 2001. The Book Eaters: Textuality, Modernity and the London Missionary Society. Semeia 88: 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Anna. 2003. Missionary Writing and Empire, 1800–1860. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Anna. 2006. A Blister on the Imperial Antipodes: Lancelot Edward Threlkeld in Polynesia and Australia. In Imperial Careering in the Long Nineteenth Century. Edited by David Lambert and Alan Lester. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 58–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Immanuel. 1996. An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment? In Practical Philosophy. Edited by Mary J. Gregor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 58–87. First published 1784. [Google Scholar]

- Kenehihi: Ko te tahi o nga upoko. 1827. Sydney: G. Eager Printer (Seen through the press by Richard Davis).

- Kirsop, Wallace. 1962. Sources in Australian Libraries for the Religious History of the XVIth and XVIIth Centuries: A Preliminary Survey. Journal of Religious History 2: 168–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsop, Wallace. 1969. Towards a History of the Australian Book Trade. Sydney: Wentworth Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsop, Wallace. 1988. Bookselling and Publishing in the Nineteenth Century. In The Book in Australia: Essays towards a Cultural and Social History. Edited by Dietrich Hans Borchardt and Wallace Kirsop. Melbourne: Australian Reference Publications in Association with the Centre for Bibliographical and Textual Studies, pp. 16–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lake, Meredith. 2018. The Bible in Australia: A Cultural History. Sydney: Newsouth. [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun, François. 2003. The Two Reformations: Communal Devotion and Personal Piety. In A History of Private Life: Passions of the Renaissance. Edited by Roger Chartier. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, vol. 3, pp. 69–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, Martyn, and John Arnold. 2001. A History of the Book in Australia, 1891–1945: A National Culture in a Colonised Market. St Lucia: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, Martyn, and Rita Marquilhas. 2017. New Directions in Book History: Approaches to the History of Written Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, Martyn, and Lucy Taksa. 1992. Australian Readers Remember: An Oral History of Reading 1890–1930. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh, Richard. 1978. Richard Johnson. Chaplain to the Colony of New South Wales. His Life and Times 1755–1827. Sydney: Library of Australian History. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, Percy Joseph. 1913. The Jewish Press of Australia Past and Present: A Paper Read before the Jewish Literary and Debating Society of Sydney. Sydney: F. W. White. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Donald Francis. 1999. Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Donald Francis. 2002. Speech-Manuscript-Print. In Making Meaning: “Printers of the Mind” and Other Essays. Edited by Peter McDonald and Michal Suarez. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, pp. 237–58. [Google Scholar]

- Monsma, Stephen V., and J. Christopher Soper. 2009. The Challenge of Pluralism: Church and State in Five Democracies. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, Craig, and Robyn Sheahan-Bright. 2006. Paper Empires: A History of the Book in Australia, 1946–2005. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parau no Iesu Christ te Temaidi no te Atua: E no te mou pipi nona. 1814. Sydney: Printed by George Howe.

- Parr, Christopher J. 1961. A Missionary Library: Printed Attempts to Instruct the Maori, 1815–1845. The Journal of the Polynesian Society 70: 429–50. [Google Scholar]

- Pettegree, Andrew. 2015. Brand Luther: 1517, Printing, and the Making of the Reformation. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Pick, Bernard. 1913. Translations of the Bible: A Chronology of the Versions of the Holy Scriptures Since the Invention of Printing. New York: American Bible Society. [Google Scholar]

- Prentis, Malcolm. 2015. Methodism in New South Wales, 1855–1902. In Methodism in Australia: A History. Edited by Glen O’Brien and Hilary M. Carey. New York: Routledge, pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Eric. 1999. An Australian Map of British and Irish Literacy in 1841. Population Studies 53: 345–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, Gwenda. 2003. George Howe: Australia’s First Publisher. Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Francis. 1993. Technology and Religious Change: Islam and the Impact of Print. Modern Asian Studies 27: 229–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sale, George. 1734. The Koran, Commonly Called the Alcoran of Mohammed/Translated into English Immediately from the Original Arabic; With Explanatory Notes, Taken from the Most Approved Commentators: To which Is Prefixed a Preliminary Discourse. London: Printed by C. Ackers for J. Wilcox. [Google Scholar]

- Schrijver, Emile G. L. 2007. The Hebraic Book. In A Companion to the History of the Book. Edited by Simon Eliot and Jonathan Rose. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 153–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shantz, Douglas. 2013. An Introduction to German Pietism: Protestant Renewal at the Dawn of Modern Europe. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 2013. Scripture and Histories. In On Teaching Religion: Essays by Jonathan Z. Smith. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 28–36. First published 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 2004. Bible and Religion. In Relating Religion: Essays in the Study of Religion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 197–214. First published 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Wilfred C. 1971. The Study of Religion and the Study of the Bible. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 39: 131–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 1978. Map Is Not Territory: Studies in the History of Religions. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan Z. 2009. Religion and Bible. Journal of Bibilical Literature 128: 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stephenson, Peta. 2010. Islam Dreaming: Indigenous Muslims in Australia. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 1814. Volume 12.574. December 3. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, Nahum, and Nicholas Brady. 1828. Select Portions of Brady and Tate’s Version of the Psalms. Hymns for Special Occasions. Doxologies. [Select Portions of the Psalms of David according to the Version of Dr. Brady and Mr. Tate, to Which Are Added Hymns for the Celebration of Church Holy-Days, and Festivals]. Sydney: Printed by Robert Howe. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge: Belknap press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Threlkeld, Lancelot. 1892. An Australian Grammar Comprehending the Principles and Natural Rules of the Language as Spoken by the Aborigines in the Vicinity of Hunter’s River, Lake Macquarie, New South Wales. Sydney: Stephens and Stokes, Herald Office. First published 1834. [Google Scholar]

- Threlkeld, Lancelot. 1827. Specimens of a Dialect of the Aborigines of New South Wales, 1826, Sydney.

- Threlkeld, Lancelot. 1897. Euangelion Unni Ta Jesu-Umba Christ-Ko-Ba Upatoara Luke-Umba. The Gospel of Jesus Christ According to Luke in Awabakal and English (R.S.V.). Ingleburn: N.S.W Bible Society in Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Vliet, Rietje van. 2007. Print and Public in Europe 1600–1800. In A Companion to the History of the Book. Edited by Simon Eliot and Jonathan Rose. Malden: Blackwell Press, pp. 247–58. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Michael. 1992. Letters of the Republic: Publication and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wesley, John. 1821. An Abridgment of the Wesleyan Hymns Selected from the Larger Hymn-Book, Published in England, for the Use of the People Called Methodists. Sydney: Printed by George Howe. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Herbert William. 1924. A Bibliography of Printed Maori to 1900. Wellington: Dominion Museum Monograph. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Don, and Eric Clancy. 1993. The Methodists: A History of Methodism in New South Wales. St. Leonards: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Wusku Wuttestamentum Nul-Lordumun Jesus Christ nuppoquohwussuaeneumun. 1661. Cambridge: Printed by Samuel Green and Marmaduke Johnson.

- Zaret, David. 1996. Religion, Science, and Printing in the Public Spheres in Seventeenth-Century England’. In Habermas and the Public Sphere. Edited by Craig Calhoun. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 212–35. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stanley, T. Religious Print in Settler Australia and Oceania. Religions 2021, 12, 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121048

Stanley T. Religious Print in Settler Australia and Oceania. Religions. 2021; 12(12):1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121048

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanley, Timothy. 2021. "Religious Print in Settler Australia and Oceania" Religions 12, no. 12: 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121048

APA StyleStanley, T. (2021). Religious Print in Settler Australia and Oceania. Religions, 12(12), 1048. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12121048