Love and the Necessity of the Trinity: An A Posteriori Argument

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Necessary A Posteriori: The Essentialist Route

| Philosophical Concepts and Domains | |

| A Prioricity | Necessity |

| Philosophical Concept: Knowledge Philosophical Domain: Epistemology | Philosophical Concept: Modality Philosophical Domain: Metaphysics |

(Paradigm): If Saul Kripke exists, then Saul Kripke is a human being.

Necessary A PosterioriA statement is necessary a posteriori if it is a necessary truth, and its truth-value is knowable solely through empirical investigation.

| Necessary A Posteriori Elements | Formality (Modus Ponens) |

|

|

3. Necessary A Posteriori: The Trinitarian Essentialist Route

| Love Argument | |

| A Priori Argument | A Posteriori Argument |

| Concept of Love: Intuition Based Philosophical Methodology: Necessary A Priori | Concept of Love: Empirical Revelation Based Philosophical Methodology: Necessary A Posteriori |

(Target): If there is a God and love is revealed as a duty-imposing, multi-formed agapê, then necessarily God is the Father.

| Necessary A Posteriori Elements | (Necessary) A Posteriori Argument |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.1. Empirical Discoveries: God and Agapê

Contingent A Posteriori Statement(2) (P∧Q) There is a God and love has been revealed as a duty-imparting, multi-formed agapê.

(E1) There is a God, identified as an essentially, everlasting omnipotent person.

(E2) God has a provided revelation, expressed by the Christian Scriptures, that identifies love as a duty-imposing, multi-formed agapê.

(E2a) Love as a Duty-Imposing Agapê(E2b) The Multi-Formedness of Agapê

3.2. A Priori Conceptual Analysis: Agapê and God

Necessary A Priori Statement(1) (P∧Q→R): If there is God and love has been revealed as a duty-imposing, multi-formed agapê, then necessarily God would be the Father.

- (A)

- Three Aspects of Agapê

- (B)

- Nature of Romantic Love

- (C)

- God’s Fulfilment of the Duty to Agapê

- appreciation

- benevolence (willing the good to the beloved)

- striving for union.

The form of love appropriate between two young and healthy newly-weds and expressed through a companionship that is both sexual and otherwise needs to be different from the form of love expressed by an elderly person’s changing the soiled underclothes of a bed-ridden spouse. Yet there is a continuity: the couple hasn’t lost their love, but their romantic love has matured to a different form or, better, sub-form.

This objection…fails to take account of the fact that a person can be divided against herself. She can lack internal integration in her mind, and the result will be that she is, as we say, double-minded. She can also lack whole-heartedness or integration in the will. Aquinas describes a person who lacks internal integration in the will as someone who wills and does not will the same thing, in virtue of willing incompatible things, or in virtue of failing to will what she wills to will. There is no union with herself for such a person.

It is highly plausible that romantic love involves a desire for a sexual union as one body—for a total sharing, total union, at the bodily level. But this union is constituted, I have argued, by a mutual biological striving for reproduction. In desiring union, the members of the couple are implicitly desiring the biological striving that constitutes it.

3.3. Necessary A Posteriori: God Is the Father

Necessary A Posteriori Statement(3) (R): Necessarily, God is the Father

4. Prospects: Further Benefits of the A Posteriori Argument

God would nonetheless, sans creation, be perfect. Again, it’s a great good to be the source of a gorgeous, amazing cosmos, teeming with life, which one beholds with satisfaction as “very good”. But we don’t want to say that God would be imperfect if he’d made nothing...…were God to have “missed out on something high and wonderful”, it doesn’t seem to follow that there would be “a deficiency in God”. Not all goods, not even all great goods, are such that their absence would render one imperfect. Some goods one doesn’t need in order to be perfect.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For Richard St. Victors argument and overall view on the Trinity, see (Richard of Saint Victor 2012, On The Trinity). |

| 2 | This causation must be instantaneous and everlasting as if d1 began to cause d2 to exist at some moment of time in the past, as noted by Swinburne, it ‘would be too late: for all eternity before that time he would not have manifested his perfect goodness’, (Swinburne 2008, p. 29). Thus, if d1 is to exist, then he must instantaneously and for all time cause and keep in being d2 (and thus experience mutual love with him through sharing all that they have with each other). And together d1 and d2 must instantaneously and for all time cause to exist, and keep in being, d3 (and therefore both experience unselfish love through each divine person having another to love and be loved by). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | As Swinburne writes himself that his ‘ethical intuitions are inevitably highly fallible’ (Swinburne 1994, p. 178). |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | This specific conception of the Trinity—termed ‘Monarchical Trinitarianism in the contemporary analytic theology literature—assumes the veracity of the doctrine of the ‘monarchy of the Father’—the teaching that God is numerically identical to the Father alone—which is in contradistinction from the common position that holds to God being numerically identical to the Trinity. The difference between these positions is more than a linguistic issue as proponents of the monarchy of the Father will take the existence of the Father to be the basis for Christian Theism being monotheistic—as there is ‘one Father’ there is ‘one God’—whereas proponents of the common position would take the existence of the Trinity to be the basis for Christian Theism being monotheistic—the ‘unified collective’ (i.e., the Trinity) is the ‘one God’. For a further philosophical explication of the notion of the monarchy of the Father and its application to the Trinity, see (Sijuwade 2021). |

| 8 | One could raise the issue of designating God ‘the Father’ is to already posit the Son (Father of the Son; Son of the Father)—as it is a relational name, which thus requires something to be in relation—however, this is not problematic as the issue under question is whether God is essentially ‘the Father’—as Trinitarians argue that he is—or is contingently ‘the Father’—as (some) non-Trinitarains argue that he is. |

| 9 | Though it could be so in non-possible worlds. |

| 10 | The name of the first route is original to this article, and the name of the second route is that of Scott Soames’ (2011). Soames (2011) was the first individual to note that there are two routes in Kripke’s work. There has been some pushback on this by Erin Eaker (2014), who sees there to only be one route present in Kripke’s work: the essentialist route. However, despite this pushback, I proceed on the assumption that there are, in fact, two routes rather than one. Nevertheless, if I am indeed wrong on this assumption, the central argument that is to be formulated in this article will remain unchanged, given that it utilises the second route over that of the first. |

| 11 | The nominal route, which is the more famous of the Kripkean routes to the necessary a posteriori, focuses on the utilisation of rigid designators—designating terms which are true of a given individual in every possible world in which it exists—and the necessity of identity—the principle that for every individual x and individual y, if x and y are the same individual, it is necessary that x and y are the same individual—which demonstrates the possibility of necessary a posteriori statements. Why this route is not further detailed and employed in this article is due to the fact that on the one hand, as Soames (2011), Fitch (1976, 2004, pp. 87–114) and others have shown, this specific route seems to fundamentally flawed and, on the other hand, as shown by Eaker (2014), and as noted above, it is questionable whether this route is even to be found within Kripke’s work. Thus, it will be more helpful to proceed with what Soames (2011) terms Kripke’s ‘successful route’ to the necessary a posteriori, which is that of his ERNA. |

| 12 | A trivial essential property would be one such as being self-identical or, being round etc. (Hughes 2004, p. 108). |

| 13 | The truth of this statement rests on the cogency of rigid designation (the thesis that a term, such as a proper name, picks out the same entity in every possible world) and origin essentialism (the thesis that an individual’s origin is essential to them). For an explanation of both of these notions and some arguments in support of them, see (Kripke 1980). |

| 14 | There is a presupposition here that the knower is a human or acquires knowledge in an empirical way. For other knowers (like God) this would probably not hold. |

| 15 | Soames (2011, p. 80) sees Kripke as preferring the usage of the notion of a ‘possible-world state’ rather than the more common notion of a ‘possible world’. Furthermore, for Kripke (1980), a possible world-state is to be conceived of as an abstract object that is simply a counterfactual state of the world rather than as a concrete ‘Lewisian’ type object. |

| 16 | Though Soames (2011, p. 81) notes that Kripke was not explicit in stating this. |

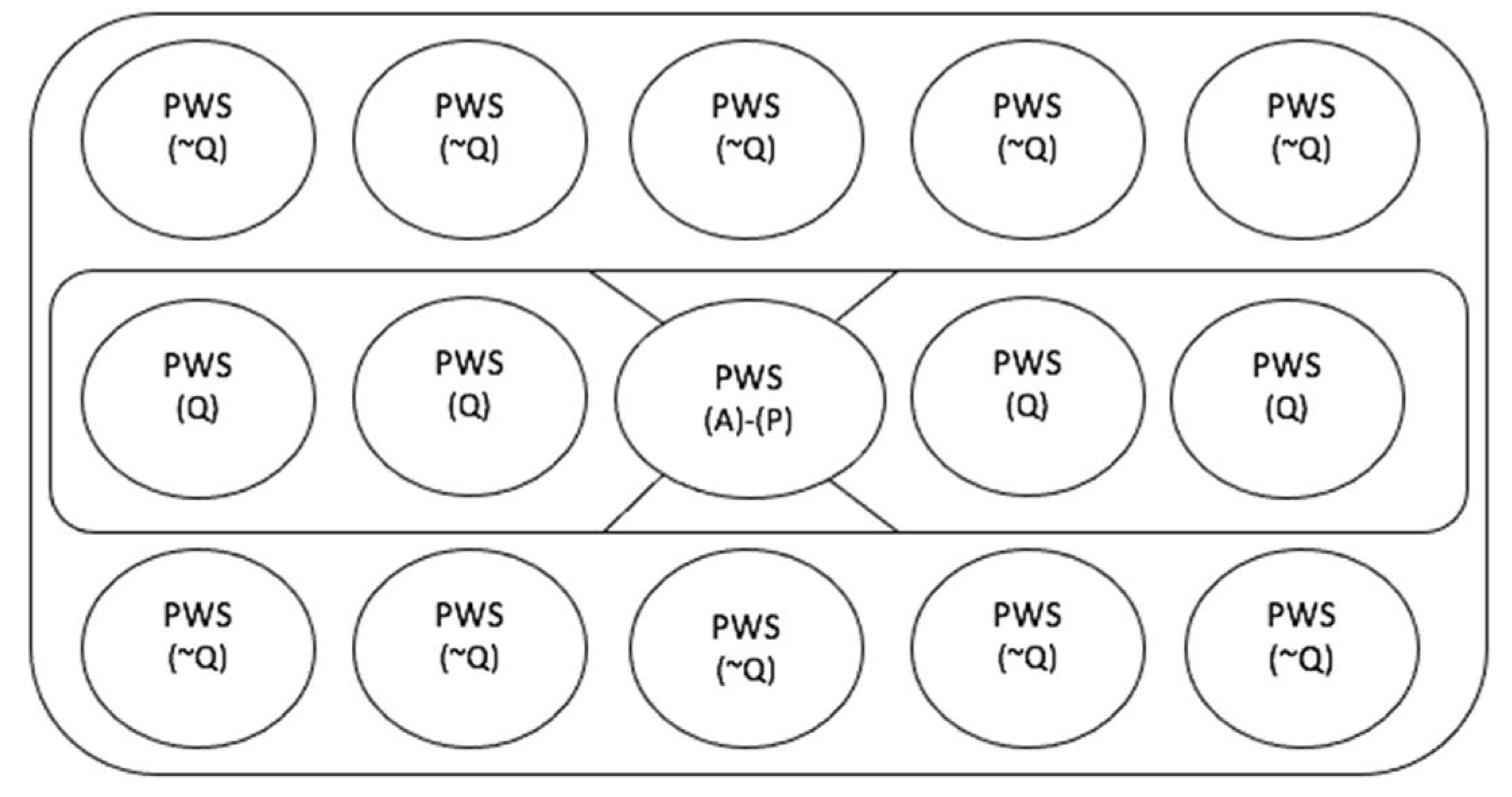

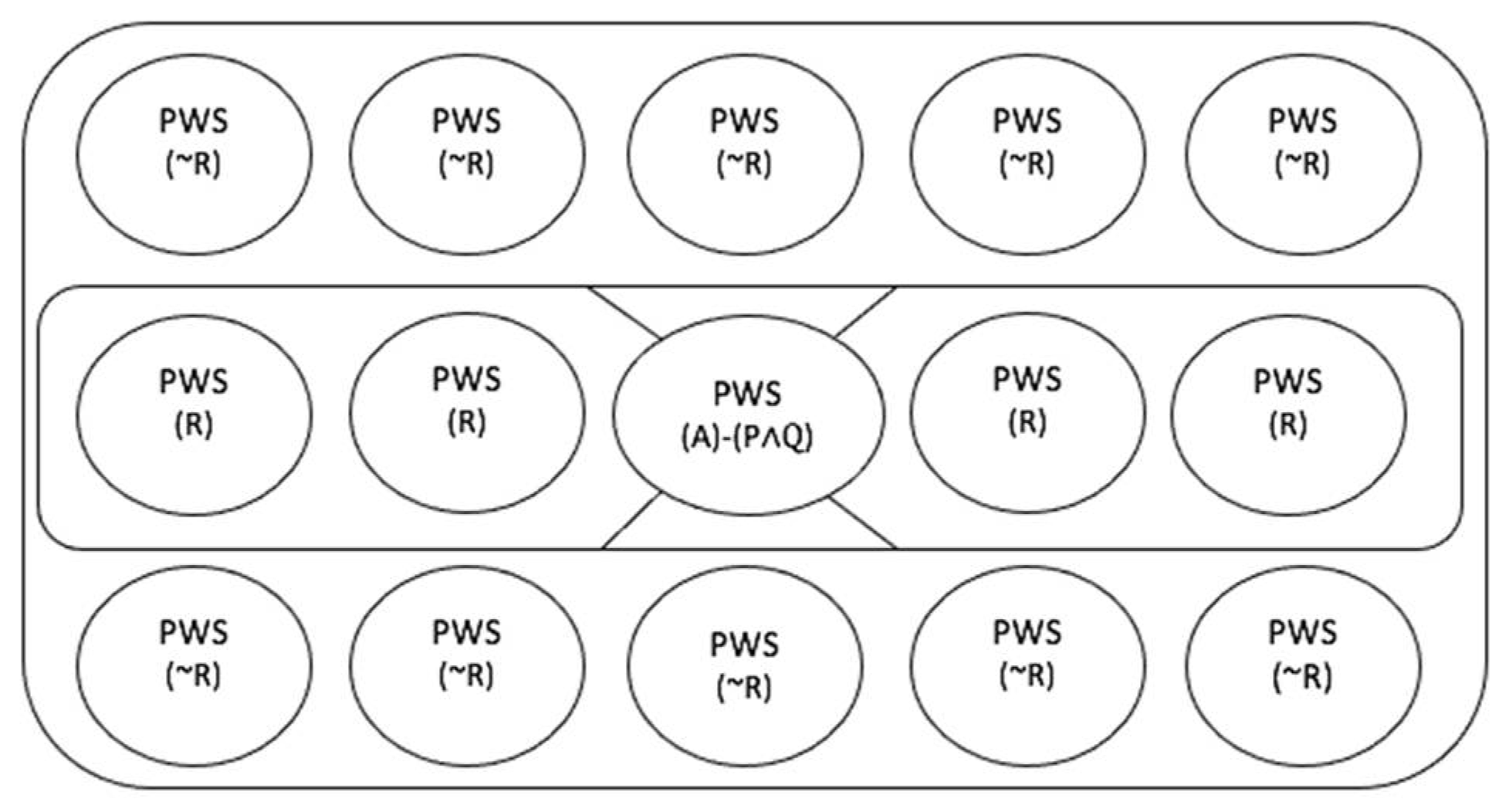

| 17 | These types of metaphysical possible-world states would be included within the small rectangular box in Figure 1 above. |

| 18 | This would be similar to how the Cosmological Argument, Teleological Argument and Moral Argument etc., are generally understood to be. |

| 19 | |

| 20 | One might see this as being a bit strong; if so, one can indeed adopt the weaker position of agapē being the superior form of love available, which still provides the needed grounds for the conclusion of the argument to be reached. |

| 21 | It is plausible that, given the missionary work of the various Christian denominations (and international organisations), over the many centuries of Christanity’s existence, the Chrisitan Revelation (as expressed by the Christian Scriptures) is universally accessible (or, at least nearly universally accessible). |

| 22 | Its important to remember that the term ‘ the Father’ is interchageable with the more conventional term ‘being Trinitarian’. |

| 23 | From this point on, (Target) will now be subsumed into (1) and referred to as such. |

| 24 | Calling the existence of God a ‘discovery’ is not to say that his existence was only recognised once Swinburne’s arguments were put forward—as natural theology has been practiced for many millennia! Rather, it is to say that Swinburne’s novel, inductive form of argumentation provides one with a certain methodology that allows God’s existence to be empirically ‘tested’ in a similar manner to scientific hypotheses. Furthermore, and more importantly, the subsequent natural theological argumentation/evidence that has been proposed by Swinburne, and which will be (very briefly) unpacked below, will be assumed to be cogent (and thus taken on as empirical discoveries that have been made). Yet, there are indeed a number of objections that can be raised against them. However, raising and responding to these objections will take us too far afield and thus, as these arguments/discoveries are not clearly implausible, we can take the conclusion to be reached at the end of this article as a prima facie, rather than an ultima facie conclusion. For the needed argumentation that establishes the ultima facie conclusion, see (Swinburne 2004). |

| 25 | God would also exist ‘necessarily’ in some sense. For an explanation of the sense in which God would exist necessarily, see (Swinburne 2016). |

| 26 | This construal of necessity is that of Swinburne’s (2004, p. 95) earlier position—the weak account, rather than Swinburne’s (2016, pp. 271–78) newer position—the intermediate account, which allows for self-causation (in an analogical sense). |

| 27 | Whereas in recognising an action as bad, God would have no motivation to perform it. |

| 28 | This data set would also include natural atheological evidence such as natural and moral evil (bad state of affairs deliberately or not deliberately caused by humans or by the negligence of humans) and the alleged state of affairs that God is hidden and the existence of individuals with an absence of belief in God. The former data slightly lowers the probability of God’s existence, whereas the latter has no effect. For a further unpacking of both (natural theological and athelogical) sets of evidence, see (Swinburne 2004, pp. 133–272). |

| 29 | |

| 30 | An important objection that one can raise is why should we take the Christian Revelation to be the most probably true candidate revelation? This is an important objection that needs to be addressed if an ultima facie assessment of the argument is to made. However, to do so here would, again, take us too far afield, given the need to propose a criteria for testing candidate revelations, arguing for the cogency of this criteria and then assessing the Christian Revelation and the other possible candidate revelations (such as the Islamic Revelation). This task surely cannot be successfully completed here. Nonetheless, for a plausible set of arguments in favour of taking the Christian Revelation to be the most probable candidate revelation, see Swinburne (2007, 2008), who has sought to fulfill this difficult task. That aside, what we can do here, as before, is simply to take the conclusion reached at the end of this article as a prima facie conclusion, that requires further argumentation to render it as an ultima facie conclusion (though it is plausible that the other candidate forms of revelation will also have similar requirements concerning the notion of agapê that will detailed below, which shows that the argument of this article is not wholly reliant upon the veracity of the Christian Revelation). |

| 31 | As with previous empirical discovery, and the assumption noted above concerning the probable truth value of the Christian Revelation, for the sake of space and time the following argument and scriptural passages provided by Pruss will also be assumed to be sound and correct. This assumption is, again, not implausible, and thus we can take the conclusion reached here to be a prima facie conclusion. For the needed further argumentation that establishes the ultima facie conclusion, see (Pruss 2013). |

| 32 | Despite love being such as to include a determination of the will that involves appreciation, goodwill and union, it is important to note that love is not experienced as these features, but is a single thing (Pruss 2013, p. 24). |

| 33 | As, the first two aspects of love will not vary drastically between the different forms of love—one can appreciate the same good of an individual in a romantic, filial and fraternal context, and the very same goods can also be willed within these contexts as well. |

| 34 | More on this notion below. |

| 35 | However, this ‘physical union’ will be taken below to be expressive of solely the human sub-form of the romantic form of love. |

| 36 | More specifically, self-love is thus taken—as with the other forms of love—to be a category that includes within it different sub-forms. The sub-forms that we take to be included within this specific category are that of ‘ordinary’ self-love and ek-static self-love. That is, ek-static self-love would thus be an analogous sub-form of ‘ordinary’ self-love—in that one is able to ek-statically love by us ‘stretching’ the meaning of ‘the self’. Now, how one can proceed to stretch (or analogise) the notion of the self here would be to follow Swinburne (2016, pp. 17–67) in, first, abandoning the ‘syntactic’ rules governing the notion of the self—which would specifically be the entailment that a self is identified as a numerically singular individual. Second, one must then find that the new ‘semantic’ rules that govern the notion of the self, resemble paradigm examples of things that we take to be selves rather than paradigm examples of things that we do not. That aside, however, the notion of ek-static self-love that has been introduced here is not ad hoc, as Pruss (2013, p. 46) sees self-love in non-theistic cases as not a wholly self-directed or self-centred notion, which we can see when he writes: In genuine love of oneself, one seeks what is good for oneself. But what is good for oneself is the life of virtue, and central to such a life is care for others. Thus, genuine self-love requires us to pursue the good of others, and in pursuing the good of others we promote our own good |

| 37 | Following our linguistic assumption noted above, we will continue to refer to divine person one as God. |

| 38 | The notion of ‘perichoresis’, as expressed in Christian theological writings, is best understood as the mutual indwelling of two (or more) entities. |

| 39 | It is important to note that, in a human context, I take the paradigm sub-form of a romantic relationship, as noted previously, to be a sexual relationship. Whereas in a theistic context, I take the paradigm sub-form of a romantic relationship to be one of a perichoretic relationship—which is not sexual, yet is simply directed in a similar manner towards the highest level of union (as ‘one nature’) as a sexual relationship is (as ‘one body’). |

| 40 | In the theistic case, the term ‘generation’ is to be favoured over that of ‘reproduction’, given the ties to biological organisms and processes, which the former does not have. Nevertheless, the notion is refer to the same type of generative act. |

| 41 | As above, in the theistic case, the term ‘generation’ is also to be favoured over that of ‘procreation’, for similar reasons. |

| 42 | Thus, unlike the human sub-form of a romantic relationship, the perichoretic lower-level activity would not be directed at the care and education of the divine person—as being omnipotent, this individual would not require care and education. Furthermore, this forwarding of the goals of the divine person would be in line with Swinburne’s (1994, p. 174) view that the divine persons each have their own separate sphere of activity. God and d2 would thus cooperatively aid the additional divine person to fulfil their goals within their own sphere of activity. |

| 43 | Specifically, the context that Swinburne proposes this response is in defense of his A Priori Argument. I have thus adopted and modified this response to fit with the A Posteriori Argument that is being presently proposed. |

| 44 | It is important to note that, even though agapê is conceptualised as a love that is a determination of the will towards the one’s beloved, in the theistic case, this determination of the will is determined by the essence of a divine person and not by the free-choice of that person. |

| 45 | These types of metaphysical possible-world states would be included within the small rectangular box in Figure 2 above. |

References

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1948. Summa Theologiae. Translated by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province. New York: Benziger Bros. [Google Scholar]

- Catholic Church. 1997. The Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed. Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Stephen T. 2006. Christian Philosophical Theology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eaker, Erin. 2014. Kripke’s sole route to the necessary a posteriori. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 44: 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, G. W. 1976. Are There Necessary A Posteriori Truths? Philosophical Studies: An International Journal for Philosophy in the Analytic Tradition 30: 243–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, G. W. 2004. Saul Kripke. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Frankfurt, Harry. G. 2004. The Reasons of Love. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hasker, William. 2013. Metaphysics of the Tri-Personal God. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Christopher. 2004. Kripke: Names, Necessity, and Identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kripke, Saul. 1980. Naming and Necessity. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kripke, Saul. 2008. Identity and Necessity. In Metaphysics: The Big Questions. Edited by Peter van Inwagen and Dean Zimmerman. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Langton, Rae, and David Lewis. 1998. Defining ‘intrinsic’. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 58: 333–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland, James P., and William L. Craig. 2003. Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview. Westmont: Inter-Varsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pruss, Alexander. 2008. One Body: Reflections on Christian Sexual Ethics. Available online: http://alexanderpruss.com/papers/OneBody-talk.html (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Pruss, Alexander. 2013. One Body: An Essay in Christian Ethics. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richard of Saint Victor. 2012. On the Trinity. Translation and Commentary by Ruben Angelici. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sijuwade, Joshua R. 2021. Building the monarchy of the Father. Religious Studies. pp. 1–20. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/religious-studies/article/abs/building-the-monarchy-of-the-father/713A3224230473308CAF87BD2A7BFF4D# (accessed on 5 March 2021).

- Soames, Scott. 2011. Kripke on Epistemic and Metaphysical Possibility: Two Routes to the Necessary A Posteriori. In Saul Kripke. Edited by Alan Berger. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 78–99. [Google Scholar]

- Stump, Eleonore. 2010. Wandering in Darkness: Narrative and the Problem of Evil. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 1994. The Christian God. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2004. The Existence of God, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2007. Revelation, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2008. Was Jesus God? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2016. The Coherence of Theism, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburne, Richard. 2018. The social theory of the Trinity. Religious Studies 5: 419–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuggy, Dale. 2015. On the Possibility of a Single Perfect Person. In Christian Philosophy of Religion. Edited by Colin Ruloff. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 128–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tuggy, Dale. 2021. Antiunitarian Arguments from Divine Perfection. Journal of Analytic Theology 9: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sijuwade, J.R. Love and the Necessity of the Trinity: An A Posteriori Argument. Religions 2021, 12, 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110990

Sijuwade JR. Love and the Necessity of the Trinity: An A Posteriori Argument. Religions. 2021; 12(11):990. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110990

Chicago/Turabian StyleSijuwade, Joshua Reginald. 2021. "Love and the Necessity of the Trinity: An A Posteriori Argument" Religions 12, no. 11: 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110990

APA StyleSijuwade, J. R. (2021). Love and the Necessity of the Trinity: An A Posteriori Argument. Religions, 12(11), 990. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110990