Abstract

This article aims to provide a metaphysical elucidation of the notion of Theism and a coherent theological synthesis of two extensions of this notion: Classical Theism and Neo-Classical Theism. A model of this notion and its extensions is formulated within the ontological pluralism framework of Kris McDaniel and Jason Turner, and the (modified) modal realism framework of David Lewis, which enables it to be explicated clearly and consistently, and two often raised objections against the elements of this notion can be successfully answered.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Nature of Theism

According to J. L. Schellenberg (2005, pp. 23–38), at the heart of religious belief is an affirmation of the existence of a reality that is metaphysically and axiologically ultimate, in relation to which an ultimate good can be attained. Religious believers are thus united in affirming the very general claim that there exists an (undefined) ultimate reality and source of goodness.1 One way in which individuals have sought to define this ultimate reality and source of goodness is through an affirmation of the truth of Theism. Theism is the central claim attested to by the major ‘theistic’ (and ‘Abrahamic’) religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and can be construed succinctly as follows:

| (1) (Theism) | There is a God, identified as the perfect and ultimate source of created reality. |

At a more specific level, an adherent of Theism (i.e., a ‘theist’) posits the existence of a necessary and eternal being, who is omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, perfectly good, and who fulfils the role of being the basic, primitive, or fundamental source of all else that exists in the hierarchical structure of reality. A specific extension of Theism that has played an influential role in the intellectual history of the major theistic religions is that of Classical Theism. Classical Theism (hereafter, CT) is the particular extension of Theism that is endorsed in the writings of the influential medieval philosophical theologians Moses Maimonides (1138–1204 CE), Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274 CE) and Ibn Sīnā (980–1037 CE). Moreover, CT is uniquely identified, as noted by Ryan T. Mullins (2021), as a specific extension of Theism that affirms four additional attributes, each of which can be stated succinctly as follows:

| (2) (Classical Theism) | God, the perfect and ultimate source of created reality, is:

|

For (a) simplicity, CT affirms the conception of God as a metaphysically simple entity. God is simple in the sense that he is non-composite and thus lacks proper parts—where a proper part is a portion of an entity that is numerically distinct from it. Thus, by taking God to be metaphysically simple, there is no portion of God that is numerically distinct from him—God must be such that he does not have any sort of complexity involving composition. So, the denial of metaphysical complexity in God is thus also a denial of him possessing any properties as well (Dolezal 2011). More specifically, God does not exemplify any numerically distinct properties (i.e., proper metaphysical parts).2 If God were to exemplify these properties, he would be dependent upon them in order to be what he is. Yet, as God cannot be dependent in specific this way—given that he is a fundamental being—he thus must not be the bearer of any properties. Rather, any intrinsic characteristic ‘attributable’ to God must be numerically identical to him. For example, if the intrinsic characteristic of goodness is attributed to God, then one is not properly attributing to him an ontologically distinct property that he exemplifies. Rather, God is instead taken to be identical with his goodness (and all the other characteristics that are attributed to him as well). Moreover, given that God is identical to each of his attributes, one must also infer that his attributes are identical to each other due to the transitivity of identity. Thus, God’s identity with his goodness and his power entails the fact of his goodness being identical to his power (and, again, for all of the other characteristics that are attributed to him). Therefore, on the basis of God’s metaphysical simplicity, there is, first, no numerical distinction between God and his attributes and, second, there is no numerical distinction between each of God’s attributes as well. God is thus metaphysically simple.

For (b) timelessness, Theism, at a general level, affirms the fact of God’s eternality (i.e., God existing without beginning and without end). CT, however, provides a specific interpretation of this eternality as that of timelessness. God is timeless by him existing without temporal succession (i.e., God does not experience a succession of events within the divine life), location (i.e., God’s existence is not datable), and extension (i.e., God does not persevere through time) (Mullins 2021, p. 87). Thus, in this specific view, God’s existence is incompatible with time, such that God exists at no particular time—with solely God’s activity being able to bring about ‘datable events’ without himself being part of any temporal process (Davies 2004, p. 6).

For (c) immutability, CT conceives of God as immutable in the sense that he cannot intrinsically or extrinsically change (Peckham 2019, p. 48). That is, within this view, all change is ‘value laden’, and thus, given this, God cannot intrinsically change—as if this were the case, then God could increase or decrease in his intrinsic value (i.e., become better or worse). Yet, if God could increase in his intrinsic value, then he was not perfect to begin with—which goes against the traditional conception of God as a perfect being. Moreover, if he could lessen in his intrinsic value, then he would not be perfect after changing—which also goes against the traditional conception of God as a perfect being. Hence, God cannot experience any intrinsic change (Dolezal 2017). In addition to this, CT also maintains the view that a perfect being cannot extrinsically change, as supposing that God is timeless, then God cannot change in his extrinsic relation to others, because any change of this sort would require temporal succession—where God at t1 is not standing in relation to a given entity x, and at t2 he is standing in that relation to x. Thus, God must be immutable in the strong sense of the term, which is to say that he cannot experience intrinsic or extrinsic change.

For (d) impassibility, CT conceives of God as being an impassible entity in the sense of him not being able to be acted upon by anything external to him (Davies 2004, p. 5). God cannot be ‘casually modified’ in any sense—as for this to be possible, then, first, God would be moved from his perfect state of bliss, which is not possible (Creel 1997). Second, God would need to be able to experience change and thus lack immutability. That is, it follows from God being immutable (i.e., intrinsically and extrinsically unchangeable) that he cannot be casually affected or acted upon by any external agent—as for this to be so would require God to be able to change. Given this, God cannot stand in any real relation to any external entity, nor can he experience any responsive or changing emotions—which is simply to say that he is impassible in the fullest sense of the word. CT thus provides a very robust conception of God that, as noted previously, has deep roots in the intellectual history of the major theistic religions. As in focusing now on Christian theism, as Davies (2004, p. 2) notes, we see that CT is the specific extension of Theism that most (if not all) Christians believed in for many centuries, with—at least from the time of St. Augustine—most theologians having almost always worked on the assumption that belief in God is simply belief in CT (i.e., a God who is simple, timeless, immutable and impassible).3 Yet, in contemporary analytic theology, a movement towards a view of God termed Neo-Classical Theism has gained some followers who have sought to call into question the veracity of the conception of God that is expressed by the tenets of (2). That is, as Fred Sanders (2017, p. 47) writes, ‘Sometime after the middle of the twentieth century, a number of related movements in academic theology began to call into question the God of Classical Theism’. Various individuals have sought to distance themselves from the CT conception of God, primarily due to their belief that there is no biblical warrant for the view, as Stump (2016, p. 19), in emphasising this point, states, ‘on Classical Theism as it is often interpreted, God is immutable, eternal, and simple, devoid of all potentiality, incapable of any passivity, and inaccessible to human knowledge. So described, the God of Classical Theism seems very different from the God of the Bible’. Thus, proponents of Neo-Classical Theism (hereafter, NCT) have sought to affirm a different conception of God—specifically, one that maintains God’s perfection and ultimacy, yet replaces the four ‘unique identifying attributes’ of CT with their contraries: complexity, temporality, mutability and passibility. Thus, the conception of God that is expressed by NCT is to be construed as follows:

| (3) (Neo-Classical Theism) | God, the perfect and ultimate source of created reality, is: (a1) Complex: has proper parts. (b1) Temporal: has temporal succession, location and extension. (c1) Mutable: is intrinsically and extrinsically changeable. (d1) Passible: is causally affectable. |

For (a1) complexity, NCT denies the fact of God being metaphysically simple, in the sense that God lacks proper parts. Rather, God is conceived of as having ‘portions’ of him that are not him—that is, God instantiates (or exemplifies) properties and thus is not numerically identical to them (Dolezal 2017). NCT thus seeks to maintain a ‘weak’ form of simplicity, which is that of God’s nature being a ‘unified’ whole, such that (for certain proponents of NCT) the various properties that are rightly predicated of God (such as omniscience, omnipresence and perfect goodness) are entailed by the possession of one property—essential omnipotence—where this property is such that it could not be had unless the other properties were had as well (Swinburne 2016).4 Positing an ‘entailment relation’ here is the key move made by adherents of NCT for providing a potentially viable alternative to simplicity that is grounded upon the unity of the divine nature. So, for example, focusing on the derivability of the property of omniscience from the property of omnipotence, for God to be omnipotent, that is him having the ability to perform any logically possible action, then he must, at the minimum, possess knowledge of what occurred in the past (and what is occurring now in the present) in order for him to know of (and believe no false propositions about) what actions are logically possible for him to perform at any given point in time. Thus, to be omnipotent, God must also be omniscient, with this requirement holding for all of the other divine properties as well. Thus, given this entailment, the divine properties fit together so as to form a unified nature, which is the sole way, according to the proponents of NCT, that simplicity can be coherently affirmed (Swinburne 1994).

For (b1) temporality, NCT affirms the fact of God being eternal, but denies CT’s interpretation of this characteristic and provides an alternative conception of God’s eternality, which is that of temporality. God is temporal by him existing with temporal succession (i.e., there being a succession of events within the divine life), location (i.e., God’s existence is datable) and extension (i.e., God perseveres through time). Thus, in this specific view, God’s existence is compatible with time, with all of his actions taking place over periods of time.

For (c1) mutability, CT denies God’s immutability—and the reasoning behind it (by questioning the assumption that all intrinsic change is value-laden and rejecting God’s immutability/timelessness)—and replacing this characteristic with mutability, which is that of God being able to experience intrinsic and extrinsic change. Yet, importantly, proponents of NCT still seek to maintain a certain form of immutability: essential immutability, which is that of God not being able to change in his essential properties—such that God is necessarily omnipotent, omniscient and perfectly good, etc. (Swinburne 2016, pp. 231–34).

For (d1) passibility, the NCT denies God’s impassibility by taking God to be an entity that can be causally affected by other entities outside of God. God’s impassibility is thus replaced by the characteristic of passibility, which is that of it being possible for God to experience changing emotional states that are responsive to created reality—with God being empathetic to such an extent with created reality that he experiences all of the emotional states of creation (Zagzebski 2013).5

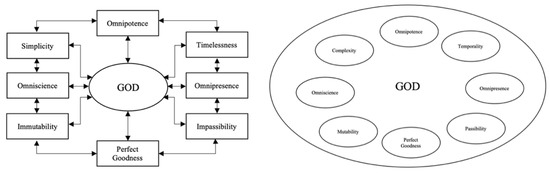

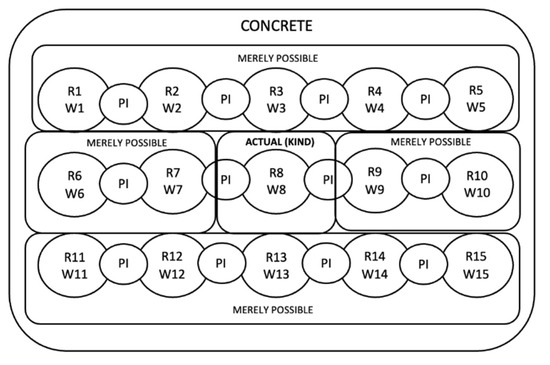

So, in the contemporary analytic theological literature, there are thus two ways for one to conceptualise God’s nature: one way, according to the proponents of CT, is to conceive of God as a simple entity who is timeless, immutable and impassible. God, under this conception, lacks parts, temporal succession, location and extension; is (intrinsically and extrinsically) unchangeable, and is not causally affectable by any external agent. However, according to the proponents of NCT, another way to conceive of God is as a complex entity that is temporal, mutable and passible. God, under this conception, is composed of parts; is able to experience temporal succession, location and extension; is (intrinsically and extrinsically) changeable, and is able to be causally affected by an external agent. There is thus a radical distinction between these two conceptions of God’s nature, which can be illustrated as such through Figure 1 (with the smaller ovals in the right mage representing the parts of God, as posited by NCT, and the double-headed arrows in the right image representing an identity relation, as posited by CT):

Figure 1.

Classical and Neo-Classical Conceptions of God.

1.2. Theism Dilemma and Creation Objection

This radical divide between the specific ways in which Theism can be extended, and thus the nature of God can be conceptualized, is indeed problematic. As, on the one hand, CT has the weight of tradition in favour of it. Yet, according to a number of scholars and biblical exegetes, it lacks a firm basis in ‘Sacred Scripture’, as Mullins (2021, p. 86) writes, ‘many scholars today think that the Bible teaches a very different conception of God than that of CT...critics of the classical view maintain that CT contradicts the biblical claims about God, especially since divine suffering and change are major biblical themes...Moreover, various classical theists admit that certain attributes, such as timelessness, are not taught in scripture’. However, on the other hand, NCT has the scriptural backing that CT lacks, although it clearly lacks strong precedent in ‘Sacred Tradition’ (and other religious traditions), given that, as Davies (2004, p. 2, emphasis added) writes, ‘Classical theism is what all Jews, Christians, and Muslims believed in for many centuries (officially, at least)’. Thus, one is faced with the issue that if they want to hold firmly to Sacred Tradition—which will include within it the consensus of the ‘Church Fathers’—then they are required to affirm CT. Yet, if they want to affirm Sacred Scripture—specifically, the veracity of the scriptural witness concerning the nature of God—then one is required to affirm NCT.

Now, an individual might hold to only one of these sources of authority, Sacred Scripture or Sacred Tradition, as having any real authority for their religious beliefs and practice, and thus they could choose to affirm one or the other conceptions of God on offer—which will help to deal with the problem at hand. Nevertheless, for certain forms of Christianity, such as Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy and (strands of) Anglicanism—let us call adherents of these forms of Christianity traditionalists—one is indeed required to affirm both sources of authority: Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition. However, in doing that, it seems as if a traditionalist must affirm a contradiction. That is, a traditionalist has to ascent to the veracity of the following construal of Theism:

| (4) (Theism1) | God, the perfect and ultimate source of created reality, is:

|

For the traditionalist, Sacred Tradition requires them to affirm (2) the CT extension of Theism that conceives of God as simple, timeless, immutable and impassible, whereas Sacred Scripture seemingly requires the traditionalist to also affirm (3) the NCT extension of Theism that conceives of God as complex, temporal, mutable and passible. The traditionalist is thus caught in a dilemma—let us call this the Theism Dilemma—with the sources of authority in the Christian faith demanding the traditionalist to affirm two extensions of Theism, which in combination—and when the central terms are further unpacked—is clearly inconsistent. The question that is now presented to the traditionalist is: how can one proceed to affirm the veracity of the traditionalist position without falling into absurdity?

The first and clear way out of this dilemma would be to deny the truth of CT, and thus affirm the truth of NCT (or vice versa), which would certainly remove the inconsistency presented by (3). However, this move is not open to the traditionalist, given that they are committed to the authority of Sacred Tradition and Sacred Scripture—and thus the conceptions of God that are expressed by these sources. However, one might have good reason to urge the traditionalist to give up their position and indeed take this option out of the dilemma. That is, some individuals such as Mullins (2021) have argued for the need for one to disaffirm the veracity of CT, given certain logical inconsistency issues that this extension of Theism faces.6 One specific argument provided by Mullins (2021, pp. 93–94), termed the Creation Objection, goes as follows: proponents of CT have sought to affirm the fact of there being a state of affairs in which God exists without creation and a state of affairs in which God exists with creation. The former state of affairs is affirmed by proponents of CT, primarily due to their commitment to God’s freedom and impassibility—God is free to create (or not) and would remain in a state of perfect happiness without creation.7 Given that there is a state of affairs in which God exists without creation and one in which God exists with creation, one can develop an argument that highlights the inconsistency inherent in a proponent of CT’s affirmation of creation ex nihilo and the timelessness and immutability of God. This argument, according to Mullins (2021, p. 93), can be stated precisely as follows:

| (5) (Creation Objection) | C1. If God begins to be related to creation, then God changes. C2. God begins to be related to creation. C3. Therefore, God changes. C4. If God changes, then God is neither immutable nor timeless. C5. Therefore, God is neither immutable nor timeless. |

Given (5), a proponent of CT must deny two of the unique identifying attributes of their conception of God. However, in order to avoid this conclusion, Mullins (2021, p. 93) sees that proponents of CT have traditionally focused on denying the truth of C2., mainly by denying the fact that God bears a real relation to creation. CT denies God’s real relation to creation because, in the thought of its proponents, God cannot be really related to anything ad extra to the divine nature—as if he were able to be, then this would result in him exemplifying an accidental property that is associated with the relation, which he cannot possess due to his simplicity. Hence, contra C2., God cannot begin to be related to creation, which enables a proponent of CT to continue to affirm God’s immutability and timelessness. In response to this, however, Mullins (2021, p. 93) sees that a critic of CT would not accept this response to the Creation Objection, as they would clearly deem it as a ‘deeply ad hoc’ move. Furthermore, Mullins (2021, p. 93) sees that a critic would raise the further issue that this specific response to C2. is unintuitive, as it is quite obvious that God’s act of creating and sustaining the universe entails the fact of him being really related to creation. Given this, the proponent of CT is thus still caught in a bind and must thus affirm the conclusion of the Creation Objection, which is a clear denial of some of the central tenets of the CT conception of God. Hence, the traditionalist, who is an individual that affirms the veracity of CT and NCT, is thus encouraged to forgo their allegiance to CT and fully adopt a NCT (or alternative) conception of God.8

So, two questions that are now presented to the traditionalist who faces the Theism Dilemma and Creation Objection is: first, is there a specific way for one to take both horns of the dilemma (as the traditionalist is required to do) without falling into absurdity? Second, is there a way to deal with the Creation Objection so as not to deny the central tenets of CT? For both questions, I believe that we do indeed have sufficient answers, which can be brought to light by employing the tools of analytic philosophy and applying them to the task at hand. Specifically, this article will seek to utilise the notion of ontological pluralism, as formulated by Kris McDaniel and Jason Turner, and the notion of modal realism, as formulated by David Lewis (and further developed by McDaniel and Philip Bricker), which, in combination, will help to provide a means for one to affirm the veracity of the CT conception of God as a simple, timeless, immutable and impassible entity that is not really related to creation—as is required by Sacred Tradition—whilst also being able to affirm the veracity of the NCT conception of God as a complex, temporal, mutable, passible entity that is really related to creation—as is required by Sacred Scripture—without falling into a contradiction. By utilising the concepts of ontological pluralism and modal realism, the traditionalist would thus be able to affirm both extensions of Theism whilst also escaping the Theism Dilemma and not being subject to the Creation Objection.9

Thus, the plan is as follows: in section two (‘Ontological Pluralism’), I explicate the nature of ontological pluralism, introduced by Kris McDaniel and Jason Turner, and apply it to the task at hand, which will provide a basis for the traditionalist to affirm the conceptions of God provided by CT and NCT. In section three (‘Modal Realism’), I then explicate the nature of Modal Realism, introduced by David K. Lewis, and further developed by McDaniel and Philip Bricker, and then apply it to the task at hand, which will complete the account that was introduced in the previous section and enable the traditionalist to affirm the veracity of Theism without facing the Theism Dilemma and being subject to the Creation Objection. After this section, there will be a final section (‘Conclusion’) summarising the above results and concluding the article.

2. Ontological Pluralism

2.1. The Nature of Ontological Pluralism

According to McDaniel (2009, 2010, 2017) and Jason Turner (2010, 2012, 2020), Ontological Pluralism is the view that there are different fundamental and irreducible ways, kinds, or modes of being.10 That is, entities can (and do) exist in different ways from one another, which is represented by different existential quantifiers—without the denial of the fact of these entities existing in the univocal category of being—namely, these entities also possessing generic existence. More specifically, the central tenets of Ontological Pluralism (hereafter, OP), according to McDaniel (2009) and Turner (2020), can be stated as follows:11

| (6) (Pluralism) |

|

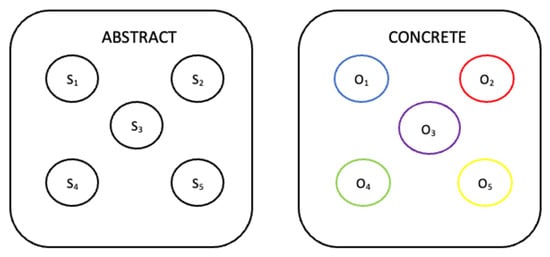

For (a), the notion of a ‘way of being’ finds its primary use in enabling one to account for the fact that the specific ontological kind (or category) that an entity is an instance of determines the specific manner in which that entity exists. For example, numbers are of a different ontological kind (or category) than tables—the former is of the kind (or category) abstracta, and the latter is of the kind (or category) concreta—and thus, these entities exist in a different manner than one another. An adherent of OP thus posits the existence of multiple ways of being in order to account for the different types of entities that display distinct features from one another. In positing the existence of multiple ways of being, OP is to be contrasted with the standard view in contemporary metaphysics of Ontological Monism (hereafter, OM), which posits the existence of solely one way of being. The notion of a way of being, posited by OM and OP, corresponds to the notion of an ontological structure. Following Turner (2010, pp. 6–7), we can further elucidate the notion of an ontological structure by utilising an analogy of a pegboard, which can be understood as follows: at a general level, an ontological structure is represented by a pegboard covered with rubber bands. For the adherent of OM, the correct understanding of ontological structure is that of a large pegboard, where pegs represent entities, and rubber bands of various colours represent objects instantiating different properties and objects standing in different relations to one another (picture, for the former, a band wrapped around a peg, and, for the latter, a band stretching from one object to another). For the adherent of OP, the view of ontological structure that is proposed by the thesis of OM is taken to be misleading in that reality is instead best represented by multiple pegboards—with each pegboard representing a distinct kind of entity with their associated ways of being. In short, proponents of OM conceive of reality as having a single ontological structure—represented by a single pegboard—for example, abstract and concrete entities existing together on one pegboard.12 However, for the proponent of OP, reality has multiple ontological structures—represented by multiple, independent pegboards—with, for example, abstract entities existing on one and concrete entities existing on another (Turner 2010).13 We can illustrate the multiple pegboards featured in OP as follows through Figure 2 (where, in the left image, ‘Abstract’ stands for ‘abstract ontological structure’ and ‘Sn’ stands for a ‘particular set peg’, whereas, in the right image, ‘Concrete’ stands for ‘concrete ontological structure’, ‘On’ stands for a ‘particular object peg’, and the different colours represent the different properties that are instantiated by each peg):

Figure 2.

Ontological Structure: Pegboard (i).

Thus, as is expressed by this particular analogy, the different ways of being featured within the framework of OP correspond to different structures or domains of reality—one can thus say that reality is indeed multi-faceted.

For (b), the notion of an ‘elite quantifier’ is grounded upon the Quinean association between existence and existential quantification—where ontology concerns what existential quantifiers range over. Given this association, the proponent of OP takes there to be several semantically primitive existential quantifiers that range over distinct domains of reality (where a quantifier is semantically primitive in the sense that it is not reducible to the unrestricted quantifier and a restricting predicate). More specifically, a central aspect of the contemporary iteration of OP, as expressed by McDaniel and Turner, is that of the denial of the fact of there being solely one existential quantifier. Rather, there are many—where, for example, there is one, ‘∃a’, which ranges over the domain of abstract entities, and another, ‘∃c’, which ranges over the domain of concrete entities (Turner 2010, p. 8). The contemporary project of OP is thus linked with quantificational pluralism—the view that there are multiple existential quantifiers, rather than a single generic quantifier (Turner 2020). However, multiple existential quantifiers can come on the cheap (i.e., one solely needs to introduce an existential quantifier and a restricting predicate to formulate more than one (restricted) existential quantifier). Hence, Caplan (2011, pp. 95–97), McDaniel (2009, pp. 305–10) and Turner (2020, p. 185) have emphasised the fact that, for the thesis of OP, only certain types of quantifiers are of concern to pluralists: elite quantifiers. Now, defining the notion of eliteness is indeed a challenging task, given that the notion seems to come in degrees. However, as noted by McDaniel (2017, pp. 27–28) and Turner (2020, p. 185), one can proceed to further elucidate the nature of this notion by adopting Sider’s (2011) extension of David Lewis’ (1983) notion of perfect naturalness, which centres around that of the notion of ‘carving nature at its joints’. Existential quantifier expressions that ‘carve nature at its joints’ are thus to be taken as elite (or ‘more elite’ than others that do not). So, taking into account the distinction between abstract and concrete entities, proponents of OP take these two kinds of entities to have different ways of being. These ways can be expressed, as noted previously, by two elite quantifiers: ‘∃a’ meaning existing abstractly (i.e., the quantifier ranging over the domain of abstract entities) and ‘∃c’ meaning existing concretely (i.e., the quantifier ranging over the domain of concrete entities). These two existential quantifiers (and the other multiple existential quantifiers posited by pluralists) are thus, as noted previously, taken as semantically primitive—through the notions that they express being irreducible—and elite, where these quantifiers (‘∃a’ and ‘∃c’) seem to be ‘fine-grained’ and deeply ‘joint carving’. Thus, taking all this into account, as McDaniel (2010, p. 635) writes, OP is the view that there are possible languages with elite quantifiers ‘that are at least as natural as the unrestricted quantifier’. At the heart of OP is thus the (surprising) claim that there are multiple ways of being and structures of reality and, most importantly, that there are multiple elite existential quantifiers that express these ways of being and structures of reality (Turner 2020). In other words, entities such as abstract entities and concrete entities are thus taken to have different fundamental ways of being—and are part of distinct fundamental structures of reality—that are ranged over by different elite existential quantifiers (e.g., ‘∃a’ and ‘∃c’). In short, one must thus use more than one existential quantifier to represent the extra ways of being and structures of reality.

For (c), the notion of ‘generic existence’ expresses the fact that all entities share in the univocal category of being. Thus, in affirming the veracity of OP—the existence of multiple ways of being that are expressed by multiple elite existential quantifiers—one is not (necessarily) negating an entity’s possession of generic existence. An adherent of OP is simply committed to the fact, as noted by McDaniel (2009, pp. 305–10), that the multiple elite quantifiers, that are taken to express the different ways of being of an entity (or entities), are more natural than the generic unrestricted quantifier—in the sense that they express the various fundamental facets of reality in a more accurate manner. Thus, in continuing with our paradigm examples of abstract and concrete entities, the distinction made between the modes of being of abstract entities and concrete entities—with the elite quantifiers of ∃a and ∃c—are simply to be taken to be more natural than the generic unrestricted existential quantifier: ∃. That is, as Bernstein (2021, p. 2), in emphasising this point, writes,

If one is taking an inventory of everything that there is, the pluralist’s ‘is’ is ambiguous between ∃1 and ∃2, and the items in being must be sorted into either category. The pluralist’s inventory is finer-grained than the list that falls in the domain of the single first-order existential quantifier, since it includes everything that there either is1 or is2.

OP thus affirms the fact that every entity—in addition to them having multiple ways of being—also enjoys the generic and univocal way of being that is expressed by the single, generic, unrestricted quantifier. Thus, what is disaffirmed by the thesis of OP is solely that of the latter quantifier being perfectly natural—in short, it does not ‘carve nature at its joints’.14 This disaffirmation, however, does not mean that single, generic, unrestricted quantifier is to be conceived of as a mere disjunction of the multiple elite existential quantifiers—given that, as McDaniel (2010) has shown, the domain that is ranged over by the former quantifier is unified by analogy. That is, as McDaniel (2010, p. 696) notes, we are aware of ‘something akin to disjunctive properties, but they aren’t merely disjunctive. Analogous features enjoy a kind of unity that merely disjunctive features lack: they are, to put it in medieval terms, unified by analogy’. This fact is evident, for example, in the concept of being healthy—which does not seem to be disjunctive, given the different ways of being healthy—as McDaniel (2010, p. 695) writes, ‘I am healthy, my circulatory system is healthy, and broccoli is healthy’. In each of these cases provided by McDaniel, there is a sense in which the generic ways of being healthy corresponds to the particular ways of being healthy—that is, we are presented with a concept of generic healthiness by analogy with the particular ways of being healthy (Builes 2019, p. 4). Existence in its many particular forms and its singular generic form is akin to this—in that, for the adherent of OP, there is a fundamental (i.e., perfectly natural) way in which certain entities exist and a non-fundamental (i.e., non-natural) and a non-disjunctive manner in which every entity generically exists, each of which is represented by (a modified form) of Quinean quantification.

The central components of the thesis of OP, and the manner in which these components are interconnected with one another, have been laid out. We will now turn our attention to applying the thesis of OP to the task at hand so as to provide a means to begin to ward off the Theism Dilemma (and a basis for avoiding the Creation Objection in the next section).

2.2. Theistic Ontological Pluralism

Theism is the basic claim that there is a perfect and ultimate source of reality. In traditional theology, and contemporary analytic theology, two extensions of this basic claim have been proposed: CT and NCT—with the former, according to (2), postulating the existence of a perfect and ultimate source of reality which is simple, timeless, immutable and impassible, and the latter, according to (3), postulating the existence of a perfect and ultimate source of reality which is complex, temporal, mutable and passible. These extensions of Theism appear to be mutually exclusive; yet the sources of authority for a traditionalist—a religious adherent who affirms the veracity of both Sacred Tradition and Sacred Scripture—require them to affirm both conceptions of God, with Sacred Tradition requiring one to conceive of God as the God of CT, and Sacred Scripture requiring one to conceive of God as the God NCT. The traditionalist is thus caught in a dilemma: the Theism Dilemma, where one must conceive of God in both ways by assenting to the truth of (4), which leads to the traditionalist affirming a clear contradiction. So the question presented to the traditionalist is: how can one take both horns of the dilemma (as the traditionalist is required to do) without falling into absurdity? Well, how one can indeed do this is by employing the notion of OP that was detailed in this section.

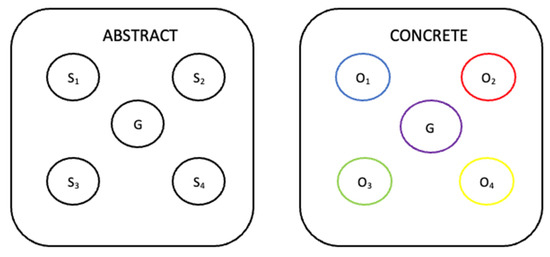

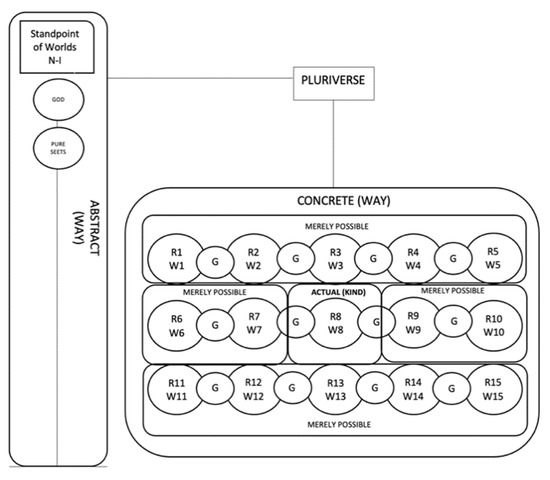

Now, in the application of the thesis of OP within a theistic context (hereafter, Theistic OP), we take it to be the case that in reality, there are two ontological structures: an abstract ontological structure and a concrete ontological structure, each of which can be represented by a specific pegboard—with each pegboard having pegs that represent the entities that exist within that given ontological structure. We can illustrate these multiple pegboards as follows through Figure 3 (where, in the left image, ‘Abstract’ stands for ‘abstract ontological structure’, ‘Sn’ stands for a ‘particular set peg’ and ‘G’ for ‘God peg’, whereas, in the right image, ‘Concrete’ stands for ‘concrete ontological structure’, ‘On’ stands for a ‘particular object peg’, ‘G’ for ‘God peg’, and the different colours represent the different properties that are instantiated by each peg):

Figure 3.

Ontological Structure: Pegboard (ii).

Each structure (and pegboard) would include within it a distinct kind of entity with a distinct way of being (or mode of existence): abstract entities that have an abstract way of being and concrete entities that have a concrete way of being. More precisely, abstract and concrete entities, though they are each a part of the univocal category of being, and thus possess generic existence (which is expressed by the single, generic, unrestricted existential quantifier ∃), are taken to have different fundamental ways of being that correspond to distinct fundamental structures of reality. Given the Quinean association between existence and existential quantification—where ontology concerns what existential quantifiers range over—these structures or domains, as noted previously, are taken to be ranged over by two different elite existential quantifiers: ‘∃a’ meaning existing abstractly and ‘∃c’ meaning existing concretely, each of which is perfectly natural by ‘carving nature at its joints’, and thus represent the distinct ways of being and structures of reality that are had by abstract entities and concrete entities. Within the framework provided by Theistic OP, we take God to be an entity that exists within two ontological structures: the abstract structure and the concrete structure. God is thus an entity that has two ways of being (or manners of existence): by existing in the abstract structure, God has an abstract way of being, represented by the quantifier ‘∃a’, and by God existing in the concrete structure, God has a concrete way of being, represented by the quantifier ‘∃c’. God is thus an entity that exists within, or overlaps, two ontological structures and domains of reality, and thus has two ways of being that correspond to these two structures and domains.

So on the basis of the different ways of being that are had by God, one can re-construe (Theism) as follows:

| (7) (Theism2) | God, the perfect and ultimate source of created reality, is: (∃a) in his abstract way of being: (∃c) in his concrete way of being: (a) Simple (a1) Complex (b) Timeless (b1) Temporal (c) Immutable (c1) Mutable (d) Impassible (d1) Passible |

In the abstract structure (or domain of reality), God’s manner existence is that of being an entity that lacks proper parts (i.e., is simple); temporal succession, location and extension (i.e., is timeless); is intrinsically and extrinsically unchangeable (i.e., is mutable); and is causally unaffectable (i.e., is passible). Yet, in the concrete structure (or domain of reality), God’s manner existence is that of being an entity that has proper parts (i.e., is complex); has temporal succession, location and extension (i.e., is temporal); is intrinsically and extrinsically changeable (i.e., is mutable); and is causally affectable (i.e., is passible). Thus, given the different ways of being that God has, there is no absurdity in a traditionalist affirming the CT and NCT extensions of Theism—as the four unique attributes posited by the former, and the contraries of these attributes that are posited by the latter, are had by God relative to a specific way of being. One can thus take the contradiction that is inherent within (4) to be produced by a false assumption that God only has generic existence (i.e., he is solely part of the univocal category of being). However, as God is taken here to have generic existence and different ways of being, one can relativise the apparently problematic attributes to the latter, rather than making the assumption that they are had by God in a singular and generic fashion. That is, the mistake that was made, and which gave rise to the Theism Dilemma, is that of one assuming a position of OM, with a single ontological structure, domain of reality and way of being that is expressed by the single, generic, unrestricted quantifier. Doing this is clearly problematic as it leads a traditionalist, who affirms the veracity of (2) and (3), to ascent to the fact that—within one ontological structure, domain of reality and way of being—God exists (∃) as a simple, timeless, immutable and impassible entity and God exists (∃) as a complex, temporal, mutable and passible entity, which is clearly contradictory. However, by assuming the position of Theistic OP, which takes God to exist within multiple ontological structures (and domains of reality) and for him to have more than one way of being (i.e., an abstract way of being and a concrete way of being)—with these ways being more natural than the generic way of being (which God does indeed possess)—the traditionalist is thus not lead to affirm a contradiction, as they are simply affirming the more ‘fine-grained’ and ‘joint carving’ state of affairs that takes into account the multiple structures, domains of reality and ways of being, in which God exists (∃a) as a simple, timeless, immutable and impassible entity and God exists (∃c) as a complex, temporal, mutable and passible entity. Thus, it is due to this relativisation of the attributes under question that we do not have a contradiction being affirmed by the traditionalist. One can thus be a traditionalist—and thus affirm the veracity of the conceptions of God that are given to one by Sacred Tradition and Sacred Scripture—without falling into absurdity. The traditionalist can thus escape the Theism Dilemma by adopting the position of Theistic OP and affirming the concept of Theism expressed by (7).

Or, is that so? Despite the conclusion reached here, one can indeed raise the objection concerning the cogency of taking God to have an abstract and concrete way of being. That is, how is it possible for God to be taken to be an abstract entity and a concrete entity? Additionally, what is the nature of the abstract and concrete structures such that God can coherently be an occupant of both? It seems as if we need a more comprehensive metaphysical account of the nature of the type of entities and categories that have been introduced here—in short, the solution to our dilemma seems to be metaphysically underdeveloped. This issue will surely need to be addressed if anyone—including the traditionalist—will be willing to sign on. Thus, to provide answers to these questions, it will be helpful to now turn our attention to detailing and applying an influential metaphysical thesis called ‘Genuine Modal Realism’,15 which will provide a means for one to build on the work that has been achieved through our utilisation of the notion of Theistic OP and thus provide a means to finally ward off the Theism Dilemma and the Creation Objection.

3. Modal Realism

3.1. Genuine Modal Realism

According to David K. Lewis (1983, 1986), Genuine Modal Realism (hereafter, GMR) is a metaphysical thesis that posits the existence of a ‘logical space’ or ‘pluriverse’ that is made up of an infinite plurality of concrete possible worlds.16 More specifically, the central tenets of Genuine Modal Realism, according to Lewis (1986, pp. 69–81), can be stated as follows:

| (8) (Realism) |

|

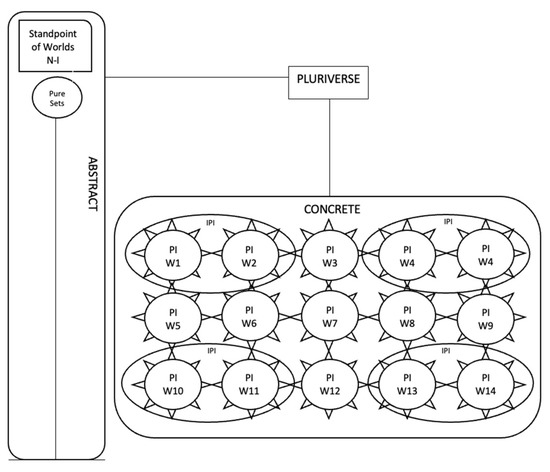

For (a), the notion of the ‘pluriverse’ functions in the framework of GMR as the metaphysical terrain of the totality of reality. In Lewis’ (1983, pp. 39–40) thought, the pluriverse is organised into three fundamental ontological categories: possible individuals, impossible individuals and non-individuals. These three ontological categories can be understood as follows: first, the category of possible individuals includes within it the entities that exist wholly within a world, i.e., as a part of that world. For the category of possible individuals, each of the worlds within the pluriverse is a (large) possible individual that has (smaller) possible individuals (such as atoms, humans and planets) as parts. Hence, any possible individual is ‘bound’ to a world through being a ‘part’ of it—with a world being an improper part of itself.17 Second, the category of impossible individuals includes within it the entities that do not exist wholly in any world, but are composed of possible individuals from two or more worlds. For the category of impossible individuals, these types of individuals are mereological summations of individuals within the pluriverse (Lewis 1983). More specifically, impossible, cross-world, individuals consist of parts from several distinct worlds within the pluriverse. As the name indicates, however, this type of individual is not a possible individual, as it is not in any world—it is partly in each of the many worlds. Third, the category of non-individuals includes within it the entities which do not exist in any world, but nevertheless exist ‘from the standpoint of a world’. That is, for the category of non-individuals, these types of entities—which are paradigmatically identified as ‘pure sets’ (i.e., numbers, properties, propositions and events)—do not exist in any world in the sense of them existing as a part of a world, nor do they exist as a mereological summation of the individuals that exist within the infinite number of distinct worlds; rather they exist from the standpoint of a world, by existing within the least restricted domain that is appropriate in evaluating the truth at the world of quantifications (Lewis 1983, p. 40). Thus, for Lewis (1983, p. 40), within the GMR framework, we have three fundamental ontological categories: possible individuals, impossible individuals and non-individuals, that are individuated by three distinct relations: being in a world (i.e., being part of a world) for possible individuals, being partly in a world (i.e., having a part that is wholly in that world) for impossible individuals, and existing from the standpoint of a world for non-individuals. For illustrative purposes, we can depict the nature of the pluriverse as follows through Figure 4 (where ‘PI’ stands for ‘possible individual’, ‘IPI’ stands for ‘impossible individuals’, ‘N-I’ stands for ‘non-individuals’, ‘’Wn’ stands for a ‘particular world’, ‘the starred circles’ represents ‘(relative) actuality’, ‘Concrete’ stands for ‘concrete domain’ and ‘Abstract’ stands for ‘abstract domain’):

Figure 4.

Nature of the Pluriverse (i).

Now, the positing of the existence of the pluriverse enables one to provide a reductive account of modality. That is, GMR, through the notion of the pluriverse (and, more importantly, the notion of a world), seeks to provide an analysis or reductive account of modal notions such that one can understand the meaning of modal locutions without them depending upon further modal notions—and thus modality being primitive. More specifically, within the framework provided by GMR, modal concepts are analysed in terms of worlds, which is expressed through the following biconditional:18

| (9) (De Dicto) | It is possible that x ↔ there is a w such that w is a world and at w, x. |

As expressed by (De Dicto), the modal operator ‘it is possible that’ (and modal operators such as ‘it is necessary that’), within the GMR framework, becomes a quantifier over worlds, which thus provides an analysis of modality and reduces the modal (e.g., possibility) to the non-modal (i.e., worlds)—ultimately dispelling the mystery that has often surrounded these types of locutions when they have been put under the ‘microscope’. In addition to the provision of an analysis of de dicto terms, GMR also provides a means for one to analyse de re modality. Before we unpack the nature of this analysis, it will be helpful to now further detail the notion of a world, as expressed by (b)–(d) of (Realism).

For (b), the notion of ‘concrete fusion’ expresses the fact that there exists an infinite plurality of concrete worlds within logical space that are identified as maximal mereological sums of spatiotemporally related individuals. The ‘concreteness’ of a world expresses the idea that the ‘merely possible worlds’ that make up the pluriverse are of the same ontological kind as the ‘actual world’. Lewis (1986), however, is hesitant to directly affirm the concreteness of worlds, given the ambiguity and lack of clarity that surrounds the abstract/concrete distinction in contemporary philosophy. Nevertheless, Lewis (1986, pp. 82–86) distinguishes four different ways of conceiving of the abstract/concrete distinction, and the manner in which worlds fit with these ways: first, the Way of Example: worlds have parts that are taken to be paradigmatically concrete (i.e., donkeys, protons, stars and galaxies). Second, the Way of Conflation: worlds are taken to be particulars and individuals, rather than universals and sets. Third, the Negative Way: worlds have parts that are taken to stand in spatiotemporal relation to one another. Fourth, the Way of Abstraction: worlds are taken to be fully determinate entities that are not abstractions from any other entity. In each of these four ways, according to Lewis (1986, p. 82), worlds (and most of their parts) can be conceived of as concrete entities—with all other types of entities (namely, non-individuals) being conceived of as abstract entities, due to the fact that these entities are not spatiotemporal and fail to meet the four-fold criteria. So a world is a concrete entity; yet, there is not only one world in logical space, but an ‘infinite plurality’ of worlds. More specifically, any way a world could possibly be is a way that some world is—in short, according to the Principle of Plenitude, worlds are abundant such that there are no ‘gaps in logical space’. In underwriting this principle, Lewis posits the holding of a more specific principle: the Principle of Recombination, according to which, as Lewis (1986, pp. 88–89) writes, ‘patching together parts of different possible worlds yields another possible world’. More specifically, the Principle of Recombination states that anything can co-exist, or fail to co-exist, with anything else. Thus, for example, as Lewis (1986, p. 88) notes, ‘if there could be a dragon, and there could be a unicorn, but there couldn’t be a dragon and a unicorn side by side, that would be an unacceptable gap in logical space, a failure of plenitude’. Thus, from the first half of this principle—that anything can co-exist with anything else—as illustrated by this example, we infer that any number of entities from different worlds can be brought together in any world, in any specific arrangement permitted by shape and size. However, for the second half of the principle—that anything can fail to co-exist with anything else—we have the example, as Lewis (1986, p. 88) writes, that ‘if there could be a talking head contiguous to the rest of a living human body, but there couldn’t be a talking head separate from the rest of a human body, that too would be a failure of plenitude’. We thus infer from this half of the principle, which expresses the Humean denial of necessary connections between distinct entities, that there is another world where one of these entities exists without the other (Bricker 2007).19 Thus, for the Principle of Recombination as a whole, anything can co-exist with anything, and anything can fail to co-exist with anything, so long as they are able to come together within the possible size and shape of spacetime that comprises the world that they are parts of (Lewis 1986, p. 90). The pluriverse is thus made up of an infinite number (and variety) of concrete worlds.

For (c), the notion of ‘isolation’ expresses the fact that there are no connections between worlds in the pluriverse—in that a given possible world is spatiotemporally (and causally) isolated from other worlds. The lack of spatiotemporal and causal connections between worlds results in the inhabitants of a given world being ‘world bound’. More specifically, a world is demarcated as a maximal individual whose parts are spatiotemporally related to one another and not anything else. That is, a world, according to Lewis (1986, p. 69), has possible individuals as parts, and is thus ‘the mereological sum of all possible individuals of one another’. In a world, if two things are parts of the same world, then they are—what Lewis (1986, p. 69) terms—worldmates. Individuals are thus worldmates if, and only if, they are spatiotemporally related. Thus, whatever is in a spatiotemporal relation with another is part of that world. A world is therefore unified, as Lewis (1986, p. 71) notes, ‘by the spatiotemporal interrelation of its parts’. However, there are no spatiotemporal relations that connect one world to another. That is, each world—which is simply the (maximal) mereological fusion of a certain set of concrete entities—is spatiotemporally isolated from every other world, as Lewis writes, ‘Worlds do not overlap; unlike Siamese twins, they have no shared parts … no possible individual is part of two worlds’ (Lewis 1983, p. 39). In other words, as the spatiotemporal relation is an equivalence relation, each individual (that is in a world) is part of exactly one world—there is no overlap between distinct worlds; rather, each world is spatiotemporally isolated and exists as the maximal sum of all of the individuals that are spatiotemporally related to it.

For (d), the notion of ‘relative actuality’ expresses the fact that all of the (‘merely possible’) worlds within the pluriverse have the same ontological status as the ‘actual world’—such that the notion of actuality is an indexical term that simply singles out the specific utterer of the sentence in the particular world in which they located at. In Lewis’ (1986, pp. 92–96) mind, actuality is a relative notion, such that each world is actual relative to itself and the individuals that inhabit it (and is thus non-actual relative to all the other worlds and individuals that inhabit those world). For Lewis, actuality is an indexical notion. That is, the word ‘actual’ is to be analysed in indexical terms, which is that of its reference varying dependent upon the relevant features of the context of utterance. That is, as Lewis (1999, p. 293) notes, ‘According to the indexical analysis I propose, ‘actual’ (in its primary sense) refers at any world w to the world w. ‘Actual’ is analogous to ‘present, an indexical term whose reference varies depending on a different feature of context’. Thus, something being actual to a given individual is that of it being part of the world that the individual inhabits—in other words, it is spatiotemporally related to that specific individual. Every world is thus actual at itself, which renders all worlds as being on par with one another. Thus, no world has the ontological status of being absolutely actual—the merely possible worlds are not to be distinguished from the ‘actual world’ in ontological status. Now, this is the nature of the pluriverse and the various worlds that exist within it. So, with this in hand, we can now turn our attention back onto assessing how GMR provides a means for one to analyse de re modality.

According to Lewis (1983, 1986), the analysis of de re modal statement is best provided through counterpart theory, which brings together the central tenets of GMR found in (Realism). More specifically, within the framework provided by GMR, worlds within the pluriverse do not overlap, and thus individuals do not exist in more than one world. Rather, each possible individual has counterparts—qualitatively similar individuals—that exist in other worlds. More precisely, a counterpart of an entity x is one that exists in a distinct world w from x and resembles x more closely than anything else that exists in w. For Lewis (1986, pp. 8–11), the counterpart relation—instead of the notion of transworld identity—is the specific resemblance relation that holds between distinct individuals that are inhabitants of distinct worlds, and thus it provides the grounds for an analysis of de re modal analysis, which can be expressed through the following biconditionals:

| (10) (De Re-P) | x is possibly F ↔ there is a world w and a counterpart x*, such that, in w, x* is F. |

| (11) (De Re-N) | x is necessarily F ↔ for every world, w, all counterparts of x are F. |

Counterpart theory thus provides the truth conditions for the modal properties that are possessed by a certain entity—and as the notion of resemblance which underpins this theory is itself a non-modal notion, modal locutions are able to be explained without reference to modal notions. Counterpart theory thus allows modal statements and locutions (e.g., x is possibly F) to be reduced to the non-modal (i.e., a counterpart of x is F). We thus have a plausible means of reducing the diversity of modal notions that have usually been taken as primitive—with this primitiveness in our structure being interpreted as that of the truth of these notions being ungrounded. At a general level, GMR thus allows one to take the non-modal claims made by (this specific theory of) modality to be a more fundamental ground for the modal statements and locutions that feature in our ordinary speech. Hence, affirming the veracity of GMR provides one with a more economical philosophical system, due to the fact that one has fewer (primitive) notions that are left unaccounted for within their system—namely, there are none. On the basis of this result, Lewis (1986, p. 3) believes that we have good grounds for believing the truth of GMR, primarily, as he notes, ‘because the hypothesis is serviceable, and that is a reason to think that it is true’. That is, we should believe in the existence of the pluriverse—which includes within it an infinite plurality of worlds (and counterparts)—due to the fact that this supposition is pragmatically virtuous. In other words, the pragmatic virtue of GMR provides sufficient justification for one accepting the extravagant ontology that is proposed by it.20 However, Lewis does not see this virtue as providing a decisive reason to favour GMR over any other alternative theory of modality, as Lewis (1986, p. 4) writes,

What price paradise? If we want the theoretical benefits that talk of possibilia brings, the most straightforward way to gain honest title to them is to accept such talk as the literal truth. It is my view that the price is right, if less spectacularly so than in the mathematical parallel. The benefits are worth their ontological cost.

Lewis thus believes that in affirming the veracity of the framework that is provided by GMR, one must perform a cost–benefit analysis—affirming the truth of GMR comes at a certain price. However, according to Lewis, this is a price that is worth paying, as, on balance, GMR costs less than alternative theories that provide the same benefits but procure more serious costs.21 Yet, despite the pragmatic value of GMR, there are indeed some (hidden) costs that have been brought to light by two important (and now standard) objections: the Humphrey Objection and the Island Universes Objection.

First, the Humphrey Objection focuses on highlighting a problem with the counterpart theory that plays a central role in the GMR framework. According to the proponent of GMR, each possible individual is world bound, and so the modal truths concerning that individual are not made true by facts concerning how that specific individual is in other worlds. Rather, these modal claims are made true by the existence and actions of counterparts of this individual. However, as Saul Kripke (1980, p. 45) famously noted

if we say ‘Humphrey might have won the election (if only he had done such-and-such)’, we are not talking about something that might have happened to Humphrey, but to someone else, a ‘counterpart’. Probably, however, Humphrey could not care less whether someone else, no matter how much resembling him, would have been victorious in another possible world.

It is a strong intuition of most—as expressed by Kripke—that the modal statement ‘Humphrey might have won the election’ (and others like it) is a statement that is solely about Humphrey, and thus the truth of that statement is one that has Humphrey, and Humphrey alone, as its truthmaker. Yet, counterpart theory takes it to be the case that this modal statement is not about Humphrey—but a counterpart existing in another world—which does not seem to be the correct truthmaker for the statement under question. Thus, as the objection goes, given the counterintuitive nature of counterpart theory, one should reject this theory and the thesis of GMR that is built upon it.

Second, the Island Universes Objection focuses on highlighting the incompatibility between the possible existence of island universes that are actual—actual individuals that do not stand in any spatiotemporal relation to one another—and some of the central tenets of the GMR framework. That is, the possible existence of island universes is problematic, under GMR, as the combination of the Isolation and Relative Actuality tenets imply that spatiotemporally disconnected island universes are impossible—in that there is no actual world that is not spatiotemporally united. As Bricker (2001, p. 28), in clearly expressing this objection, writes,

According to Lewis, possible individuals are part of one and the same possible world if, and only if, they are spatiotemporally related. It follows immediately that no possible world is composed of island universes of spatiotemporally isolated parts. Given the standard analysis of possibility as truth at some possible world, island universes, then, are impossible.

As with the issue raised by the Humphrey Objection, intuitively, it seems to be the case that it is possible that there could be more than one physical universe that is spatiotemporally unrelated to another. Yet, this is indeed also ruled out by GMR, which provides another good reason to reject GMR. Thus, the question that is now presented to a proponent of GMR is: should one indeed reject the GMR framework, given the incompatibility between our (pre-theoretic) intuitions, counterpart theory and the possibility of island universes, or is there a way to deal with these two problems by providing a version of modal realism that is not plagued by these issues? I do believe that one can take the latter option by adopting elements of two alternative versions of modal realism: Modal Realism with Overlap—proposed by Kris McDaniel—and Leibnizian Realism—proposed by Philip Bricker, which, when brought together, provide a means to affirm the veracity of modal realism without facing the Humphrey Objection and Island Universes Objection. More specifically, Modal Realism with Overlap proposes a version of GMR that does not include counterpart theory—and thus replaces the tenet of Isolation with that of Overlap, which allows one to abandon counterpart theory and thus ward off the Humphrey Objection. Furthermore, Leibnizian Realism proposes a version of GMR which does not relativise actuality—and thus replaces the tenet of Relative Actuality with that of Absolute Actuality, which provides one with a clear way to affirm the possible existence of island universes and thus ward off the Island Universes Objection. One can thus deal with both objections against GMR by combining the versions above—let us term this combination Leibnizian Realism with Overlap—which will also provide a more robust version of GMR that will be helpful in further clarifying the nature of Theism in the next section. It will be helpful to now further flesh out the central tenets of this version of modal realism.

3.2. Leibnizian Realism with Overlap

According to McDaniel (2004, 2006) and Bricker (2001, 2006, 2007), Leibnizian Realism with Overlap (hereafter, LRO) takes the worlds that make up the pluriverse to be similar to the worlds that are postulated by GMR—in that both theses conceive of worlds as ‘concrete’ objects that are maximal spatiotemporal entities. However, in the framework provided by LRO, worlds, contra Lewis, are not defined as maximal mereological sums of individuals. Rather, a given world is a ‘concrete’ object that is a maximal region of spacetime that has objects as occupants (not parts), is spatiotemporally isolated from other worlds, and is absolutely actual—by being an instance of the category of actuality and bearing the property of actuality. More specifically, the central tenets of LRO can be stated as follows:

| (12) (Realism*) |

|

Within the framework of LRO, the tenet of Pluriverse (i.e., that there exists an infinite plurality of concrete worlds) is maintained in the modification that is made to GMR by this version of modal realism, with solely the tenets of Concrete Fusion, Isolation and Relative Actuality being replaced with the tenets of Concrete Regions, Overlap and Absolute Actuality, each of which we can now briefly unpack.22

For (b) and (c), the notions of ‘concrete regions’ and ‘overlap’ express the fact of there being an infinite plurality of worlds that are identified as maximally spatiotemporally related regions of spacetime that have objects as occupants of those regions. Worlds are spatiotemporally isolated maximal regions of spacetime—rather than the maximal summation of the things that they contain—such that, as McDaniel (2004, p. 147) notes, ‘worlds are containers in the same sense that regions of spacetime are containers’.23 These regions of spacetime—instead of the material objects that they contain—are ‘parts’ of worlds. In other words, the primary way in which LRO conceives of an object being ‘contained’ within a world—that is, it existing at a specific world by occupying a spatiotemporal region—is that of it being wholly present at that region, without being a part of that region. At a more precise level, an object x exists at a world, as McDaniel (2004, p. 147) writes, if, and only if, ‘there is some region R such that (i) x is wholly present at R and (ii) R is a part of w; a region R exists at a world iff it is a part of that world’. Hence, according to LRO, the ‘atness’ relation within a world reduces to occupation. A specific object is thus at more than one world by it occupying a particular region that is part of one of the worlds, whilst it also occupying a different region that is part of one of the other worlds within the pluriverse. Material objects, as McDaniel (2006, p. 306) notes, thus ‘enjoy multi-location’.24

In addition to the account of ‘existing at a world’ provided by LRO, we also have an account of what it is for a particular object to have a ‘part at a world’ and a ‘property at a world’. For the former notion, an entity x is a part of an entity y at world w, according to McDaniel (2004, p. 148), if and only if ‘there is some R such that x is part of y at R and R is a part of w’. Objects thus have parts at parts of worlds. That is, assuming compositional pluralism—the thesis that there are two different fundamental part-whole relations—the fundamental parthood relation for spacetime regions is a two-place relation—where a region of spacetime is part of a region of spacetime simpliciter (i.e., not relative to anything). In contrast, the fundamental parthood relation for material objects is a three-place relation—where part-whole relations for material objects are indexed to specific spacetime regions. Objects are thus not parts of worlds but have parts at worlds, such that, as McDaniel (2006, p. 306) notes, ‘Objects and worlds not only do not overlap, but cannot overlap given that objects and worlds are unified by numerically distinct parthood relations’. Now, in a similar manner to the part-whole relation for material objects, LRO takes the possession of properties to also be indexed to spatiotemporal regions—namely, a given object has a property only if there is a specific region of spacetime, such that the object is wholly present at that region, the region is part of the whole in question, and the object possesses that property relative to that region (McDaniel 2004). Thus, given the notions of having a part at a world and a property at a world, an object cannot have a part or property simpliciter. Instead, an object must have a part of a property relative to a certain spatiotemporal region. Thus, as McDaniel (2006, p. 306) writes, given LRO, ‘objects are literally wholly present at different possible worlds. And the properties that an object literally has at other possible worlds are literally the properties that this very same object at our world could have had’. So, what we see here is that of the atness relation being able to be construed in a variety of different ways within the LRO framework.

For (d), the notion of ‘absolute actuality’ expresses the fact that actuality is a primitive (i.e., unanalysable) property that is categorial and absolute. In the pluriverse, there are many worlds; yet there is (at the least) only one world—our world—that possesses the special property of being actual.25 Actual entities comprise a fundamental ontological category by sharing a primitive, non-qualitative property of ‘actuality’, such that it is in virtue of these entities belonging to that specific category—and possessing that specific property—that they have a different ontological status to merely possible entities (Bricker 2007). In other words, actual entities are distinguishable by them possessing the special property of actuality, which results in a certain region of the pluriverse—the ‘region of actuality’—being ontologically distinct from another region—the ‘region of the merely possible’—with the latter not forming a genuine ontological category (Bricker 2006). Moreover, the ontological status bestowed upon these entities by the property of actuality is had by them in an absolute manner—in that, contra Lewis, actuality is not relative to the individual. Therefore, there is an ontological distinction of kind between the actual and the merely possible. Hence, as Bricker (2001, p. 29) notes, there is thus ‘an absolute fact as to which among all the possible worlds has been actualized’. Yet, despite actuality being absolute, rather than relative, actuality is still a contingent notion, due to the fact that a distinction can be made between what is true of a world and what is true at a world—such that possibility and necessity are to be interpreted in terms of what is true at a world, rather than what is true of a world. A property is true of a world, as Bricker (2006, p. 43) writes, ‘when the world has that property; a property is true at a world when the world represents itself as having that property’. In most cases, what is true at a world is what is true of that world; however, in the case of actuality, the two notions of ‘truth of’ and ‘truth at’ a world do not coincide, in that ‘is actual’ is true at every world, but is true of our world and no other world. Thus, the absoluteness of actuality is secured by the latter affirmation—a certain world has a special ontological status that other merely possible worlds do not have—and the contingency of actuality is secured by the former affirmation—namely, which specific world is actual is contingent as any world could be actual.

Now, in dealing with the Humphrey Objection and the Island Universes Objection—with a focus first on the latter—it is specifically the absoluteness of actuality, and the inherent contingency of it, that provides a means for one to affirm the possible existence of island universes as a modal realist—as by affirming the actuality of one world, one can indeed allow that the actual realm is, in fact, composed of island universes by permitting more than one world to be actual. In other words, unlike the position expressed by GMR, LRO allows for there to be a part of actuality that is spatiotemporally and causally isolated from the part that we, in fact, inhabit. Hence, the possibility of island universes is no issue for LRO.

Furthermore, it is specifically on the basis of this ‘existing at relation’ that one can reap the rewards of GMR—namely, the theoretical advantages of reducing the modal to the non-modal—without adopting counterpart theory and thus facing the Humphrey Objection—as de re modality can now be analysed within a new theoretical framework. That is, first, within the LRO framework, the notion of possibility is to be construed as such through the following biconditional:

| (13) (De Re-P2) | x is possibly F ↔ there is a world, w, such that x exists at w and is F at w; x exists at w iff x is wholly present at a region R that is itself a part of w. |

Second, the notion of necessity can also be construed as such through the following biconditional:

| (14) (De Re-N2) | x is necessarily F ↔ for every world, w, x itself exists at w and is F at w; x exists at w iff x is wholly present at a region R that is itself a part of w. |

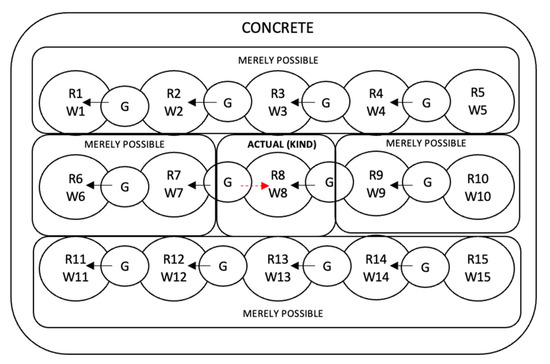

According to LRO, de re modal claims about objects are thus not made true by facts about counterparts of the objects in question; rather, they are made true by facts about the objects themselves—by the features that these objects literally have at other worlds. Within the LRO framework, some worlds within the pluriverse are thus taken to have overlapping content—and thus Isolation being false—as there exist worlds w1 and w2 that have objects that literally exists at both worlds, with different parts and properties at those worlds. For heuristic purposes, we can thus illustrate the important modifications made to the structure and map of reality by LRO as follows through Figure 5 (where, again, ‘PI’ stands for ‘possible (overlapping) individual’, ‘Rn’ stands for ‘region of space time’, ‘Wn’ stands for a ‘particular world’, ‘Merely Possible boxes’ represent ‘merely possible category/individuals’, ‘Actual (Kind) box’ represents ‘the actual world category/individuals’ and ‘Concrete’ stands for ‘concrete domain’):26

Figure 5.

Leibnizian Realism with Overlap.

Modal statements are thus now taken to be reducible to worlds and their occupants (i.e., objects), rather than that of counterparts that are taken to be inhabitants of a world. Hence, in fulfilling this role, one can thus take objects to not be world bound, and worlds are not isolated; instead, objects are (possibly) multi-located, and worlds can indeed overlap. Thus, given this, contra the Humphrey Objection, the truth of a modal statement about Humphrey would have Humphrey, and him alone, as its truthmaker. LRO thus fits with our pre-theoretic intuitions. Therefore, the central components of the thesis of GMR (now conceived of as LRO) have now been laid out, and the manner in which these components work together has been explicated. We will now turn our attention to applying the thesis of LRO to the task at hand to help show how the traditionalist can further elucidate the nature of Theism so as to provide a means to ward off the Theism Dilemma and the Creation Objection.

3.3. Theistic Modal Realism

In the Theistic OP framework, God has two ways of being: an abstract way of being (∃a) and a concrete way of being (∃c). In God’s abstract way of being, he exists as a simple, timeless, impassible and immutable entity, and in God’s concrete way of being, he exists as a simple, temporal, passible and mutable entity. This is the ontological strategy provided by the thesis of Theistic OP that enables one to deal with the Theism Dilemma. However, more can be said here by utilising the metaphysical thesis of modal realism, which, in combination with Theistic Ontological Pluralism, we can term Theistic Modal Realism (hereafter, Theistic MR). In Theistic MR—which adopts the version of modal realism that was previously termed LRO (rather than that of Lewis’ GMR)—the ‘pluriverse’, i.e., the totality of metaphysical reality and largest domain of quantification, is categorisable into three fundamental ontological categories: possible individuals, impossible individuals and non-individuals.27

Within the framework of Theistic MR, we now associate God’s abstract way of being, which was previously detailed, with the non-individual category, and God’s concrete way of being, which was also previously detailed, now with the possible individual category.

Focusing now on the first association made within the Theistic MR framework: God’s abstract way of being with the non-individual category, God has one way of being in which he exists within the domain of abstract entities—that is, God’s mode of being is him existing with the status of an abstract entity. More precisely, within the pluriverse, the domain of abstract entities includes the category of non-individuals, with the instances of this category each existing at the standpoint of a world—where an entity exists from the standpoint of a world if, as noted previously, it ‘belongs to the least restricted domain that is normally…appropriate in evaluating the truth at that world of quantifications’.28

God, in his abstract way of being, does not exist wholly or partly at any world—and thus is not conceived of within this mode of existence as a possible or impossible individual. Rather, as with other necessary abstract entities (i.e., pure sets), God exists from the standpoint of every world. That is, within the framework of Theistic MR, a traditionalist can thus take God to be among the objects that exist from the standpoint of each world. God has the same ontological status as abstract entities—without being like these objects in all respects.29

In other words, God has the same status as (some) abstract entities qua existing from the standpoint of every world, which thus results in him—in this specific way of being—being an object that does not bear properties and is outside of space and time altogether. More fully, as an entity that exists from the standpoint of every world, God, in this specific mode of being, is not a spatiotemporal object, which entails the fact of him being a simple, timeless, immutable and impassible entity. As a non-spatiotemporal object that exists from the standpoint of a world (rather than at a world), God is, first, not composed of proper (metaphysical parts)—in the sense of him instantiating properties—as properties are indexed to regions of spacetime.30

That is, as God, in this particular way of being, does not occupy regions of spacetime (by not existing at a world), he does not instantiate any properties—essential or non-essential. Instead, God is numerically identical to each ‘attribution’ that is made of him—with these attributions (such as being omnipotent, omniscient, and perfectly good) not designating any type of ‘property’.31