Bible Journaling as a Spiritual Aid in Addiction Recovery

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology: A Multimodal Analysis

- Population size generally, the large population of Christians, and then the large number of Bible journaling Christians within that demographic.

- Location of primary market for US journaling Bible publishers.

- Energetic marketing of the Bible journaling products and peripherals (stationery, pens, highlighters, paints, paste-ins, etc.).

- Importance of the Bible in Protestant and Evangelical churches especially.

- Previous success of related creative, paper-based hobbies such as scrapbooking and colouring.

- Social media platforms facilitating groups and the sharing of experience and expertise, products, etc. Of the initial over thirty women who responded to me in the social media groups, only a handful were not geographically located in North America. Those willing to participate in a research project, to discuss their experience of addiction and to share photographs of their pages were all from North America.

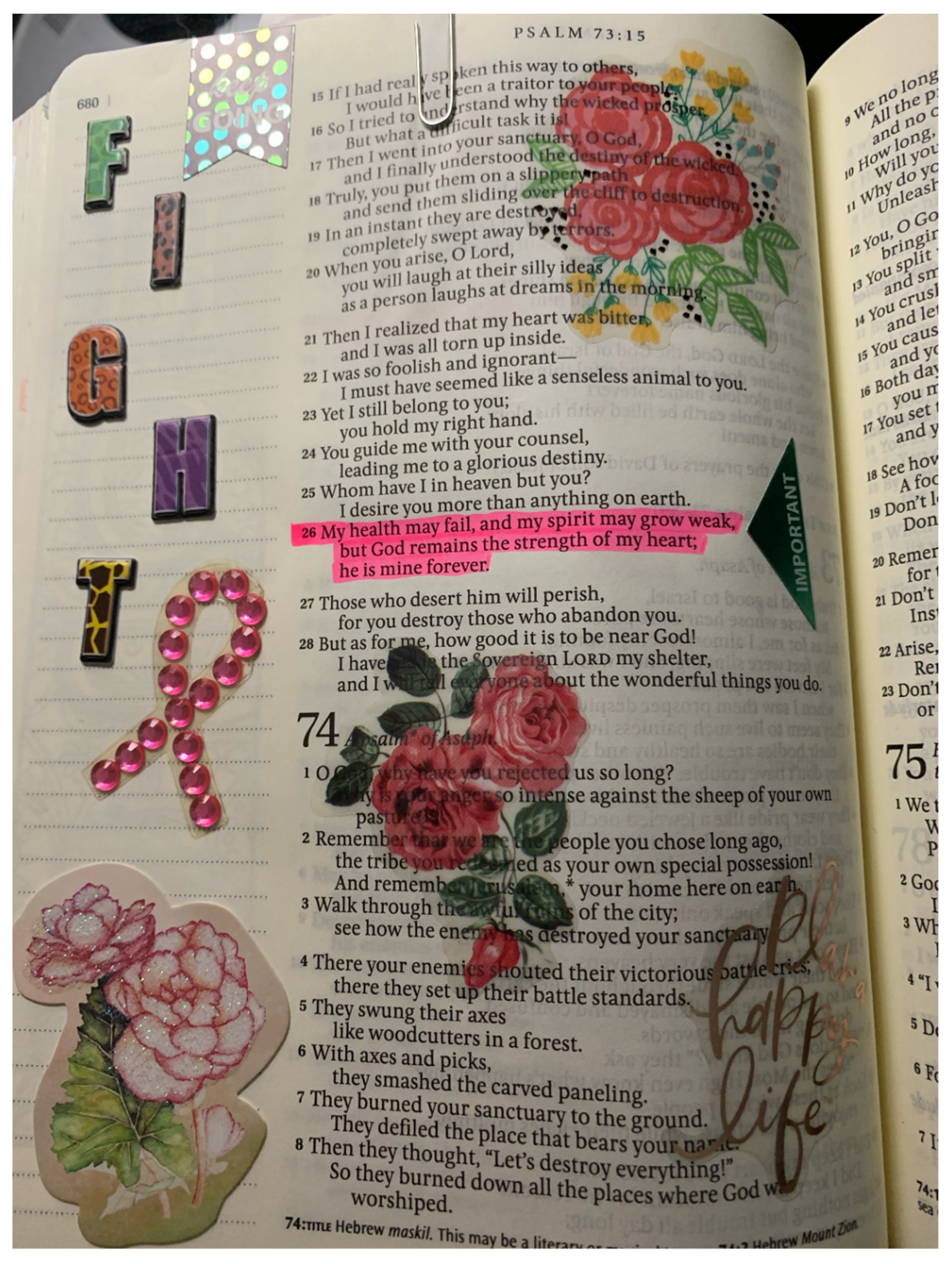

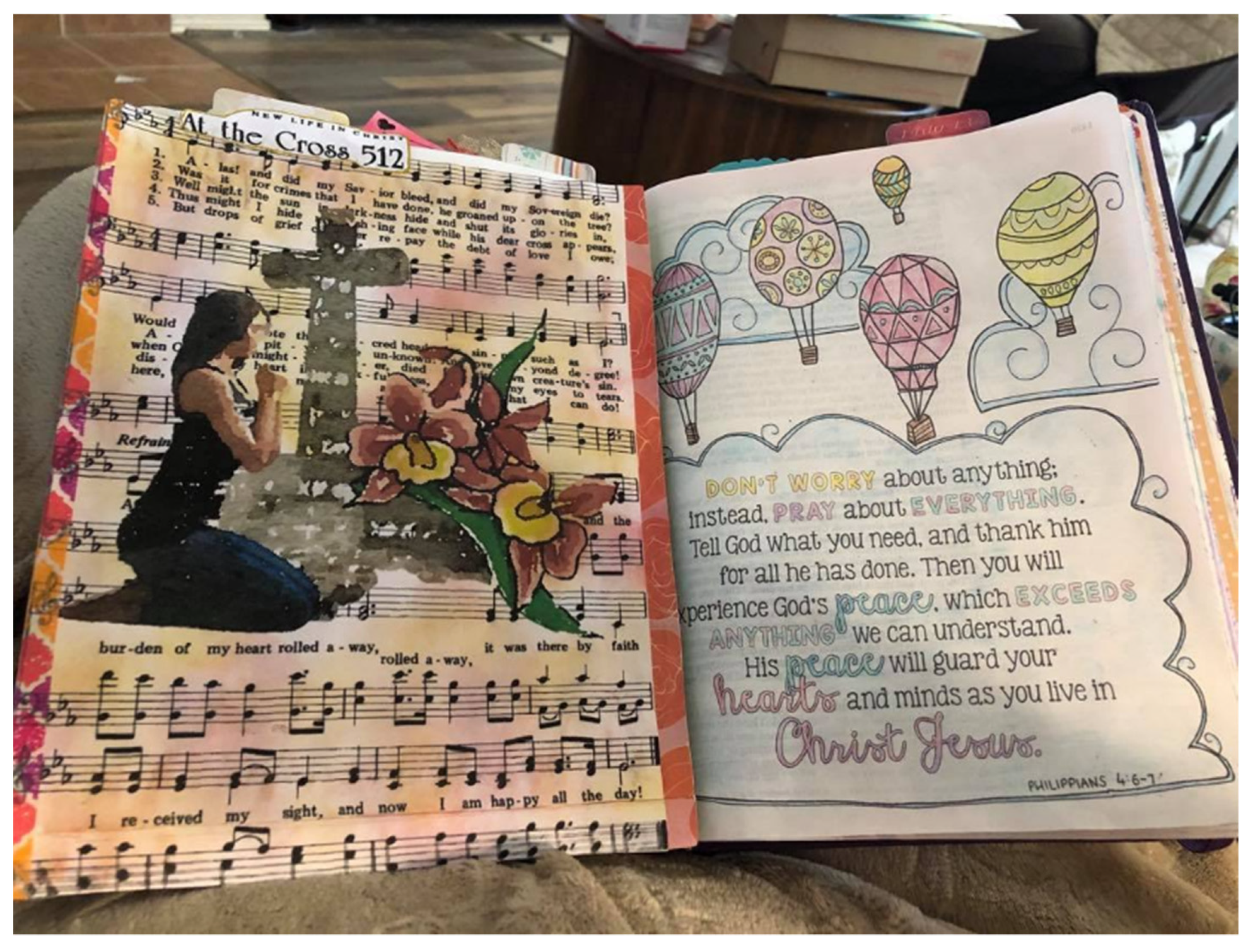

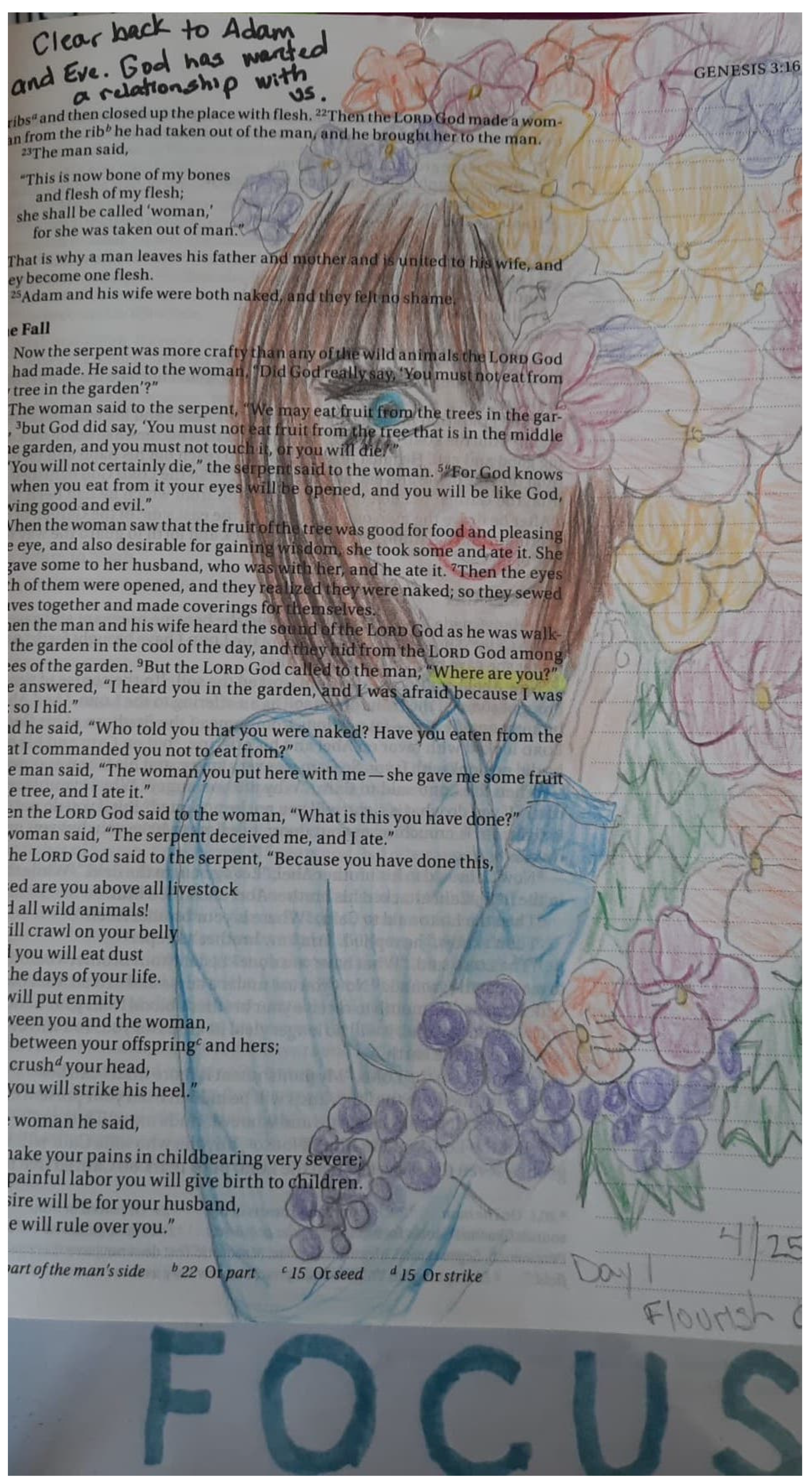

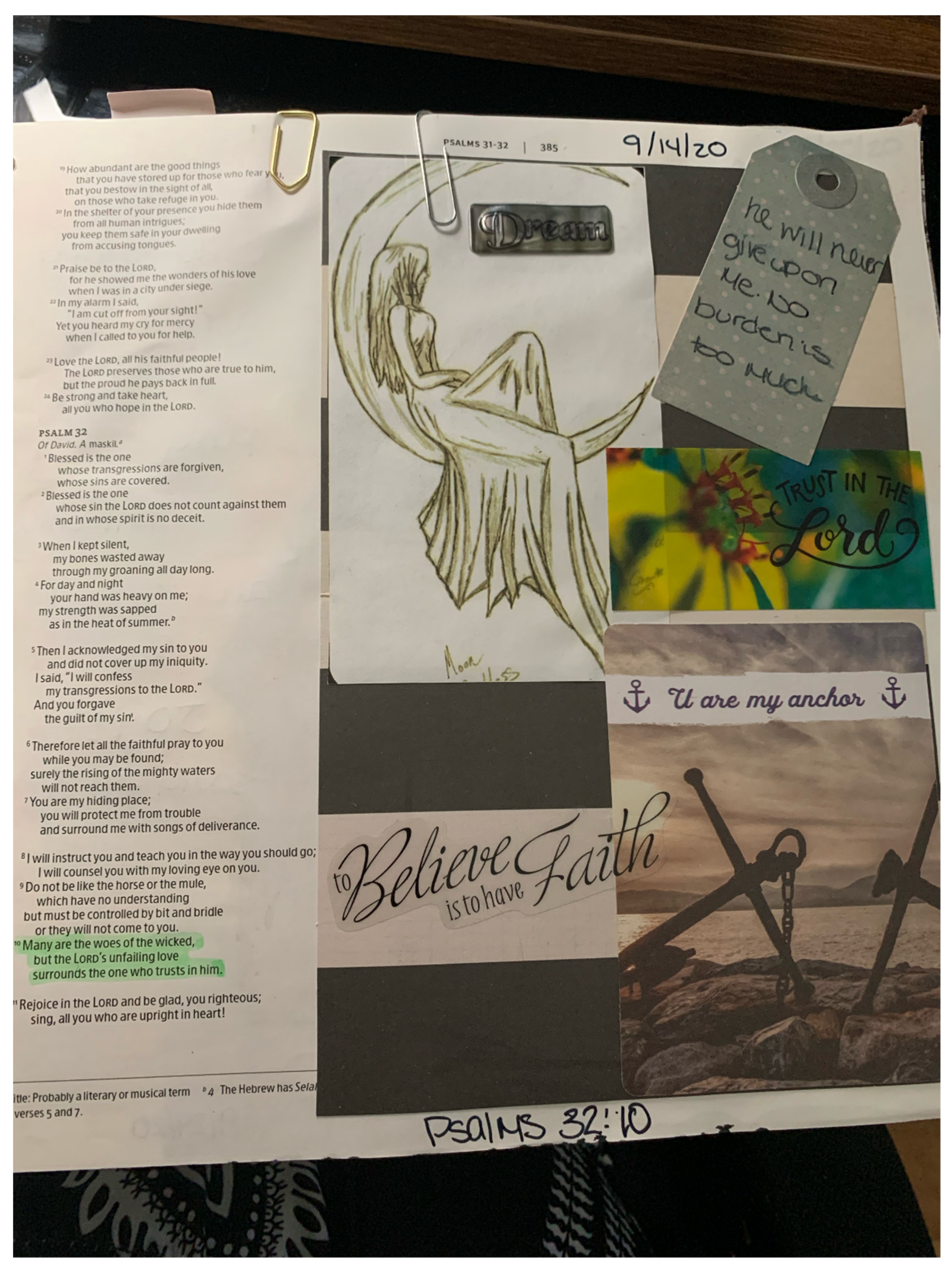

3. An Overview of the Bible Journalers and Their Practice

3.1. Pathways into Bible Journaling: Faith, Church and Addiction

Growing up we never had Bibles or heard anything about King Jesus and my family was alcoholics and drug addicts, so of course I started using and drinking at a young age, fast forward to about maybe 7–8 years ago, I was at my lowest, my rock bottom so to speak. I was homeless and heavy into crystal meth. I journaled a lot of that noise and it helped me to keep my head. The one moment I remember clearly was standing on a street corner asking the Lord for something, anything, as I was just done (which was also an entry in a journal). I was led to a trailer called “Love Lives Here” and there met a servant of Christ Jesus who was ministering repentance and water baptism. I never heard such things before. I then started reading the Bible and really journaling my struggle. Now, here’s where the journaling really came into action—I wrote everything: my fears about never getting clean, my fears about being homeless and sleeping on the street in the murder capital of this country. I also journaled all my moments of happiness, and things I was learning in the Bible stories, and about the people around me who inspired me. Journaling became my place where I could just sort things out where I could express things and be with the Father as no one else ever read my journals. My personal sort of documented walk [with the Lord].

Another woman describes her experience:I was baptised four years ago. Before I found God I had struggled in the area of addiction. I was also selling … I was in deep. Probably 35 Perc 30s a day.2 I was awful. I threw all my relationships in the trash and didn’t care … I grew up with an alcoholic and distant father who pushed me away constantly. My mother, the biggest source of strength had moved out of the state. My sister and brother both struggled with some addictions too and they lived in other states too. I felt like I had no one to turn to. Then one day I just stopped cold turkey. I had had enough. I was so tired of living my life that way! My children needed me more than I needed what I was doing. It wasn’t until I quit that I literally felt God calling me. I started out with Jehovah’s Witnesses coming to my home teaching me the Bible. I was honest and told them point blank I didn’t see myself attending their church but that I was more than happy to host them at my home (before Rona) in order to learn the Bible itself. She was such a sweet woman she came every week for over two years. My other half and I moved and we got a car and, finally, I was able to find my home at the Rock Church. This family here has been amazing.

My addiction was to multiple substances. Pills, coke, heroine. I did a lot of things that I was not proud of. I lost my faith throughout all of that. I almost overdosed, and in that moment I snapped back to reality and said to myself I need God back in my life. I need him to help me, I need him to save me. I am now five years clean and my relationship with God is stronger than ever. Bible journaling was a new way for me to express myself and my love for God and all he has brought back into my life after losing it all to addiction.

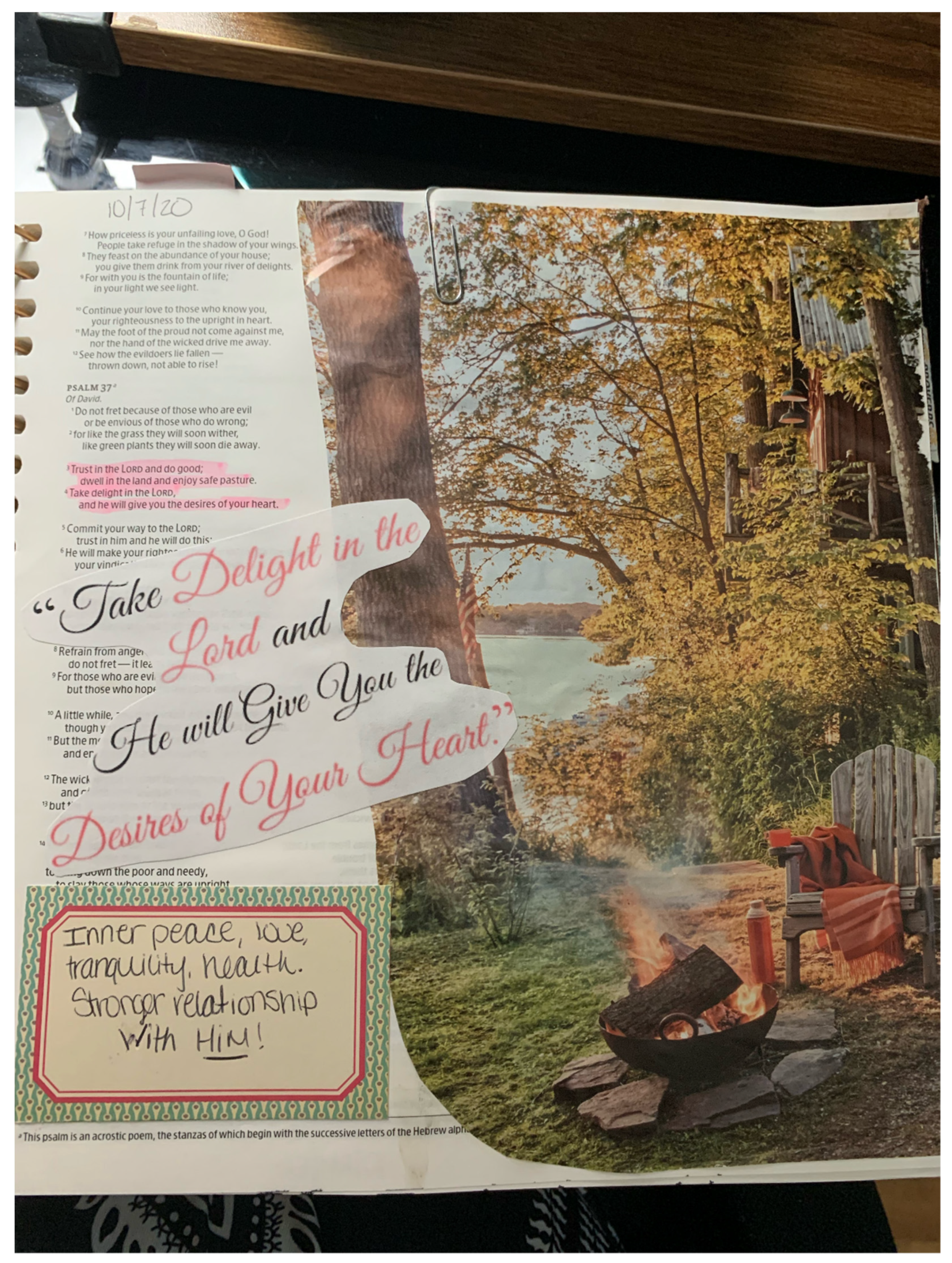

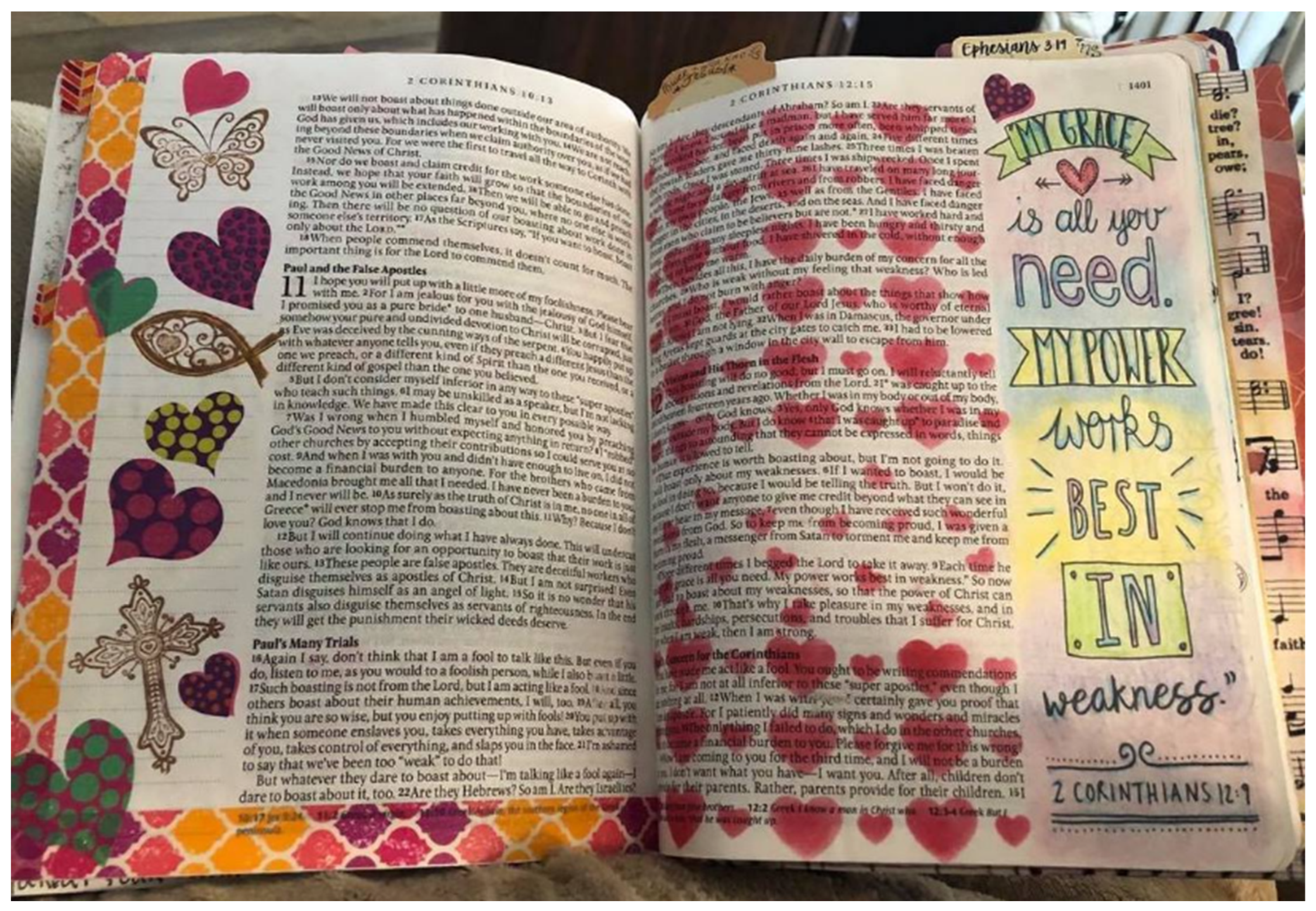

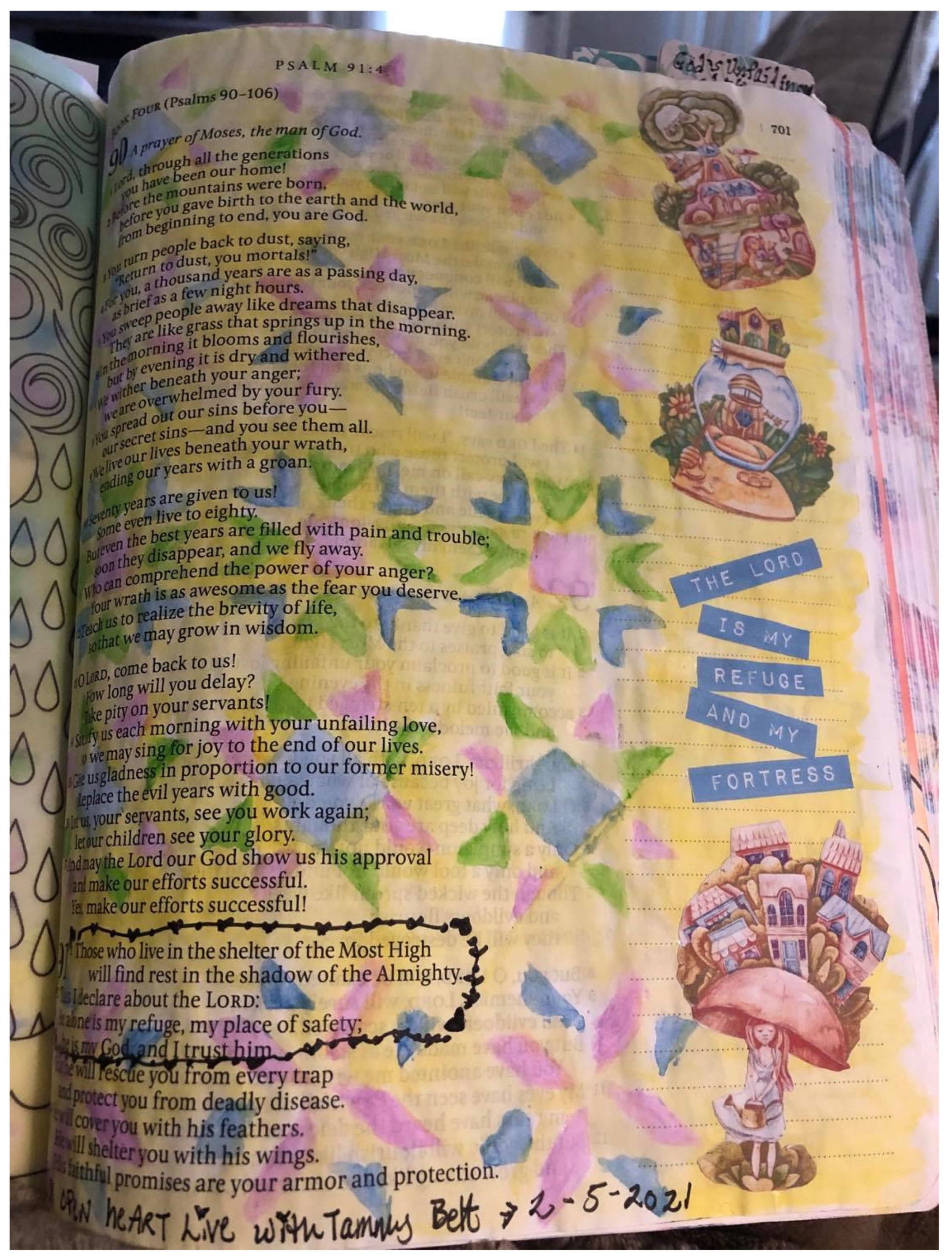

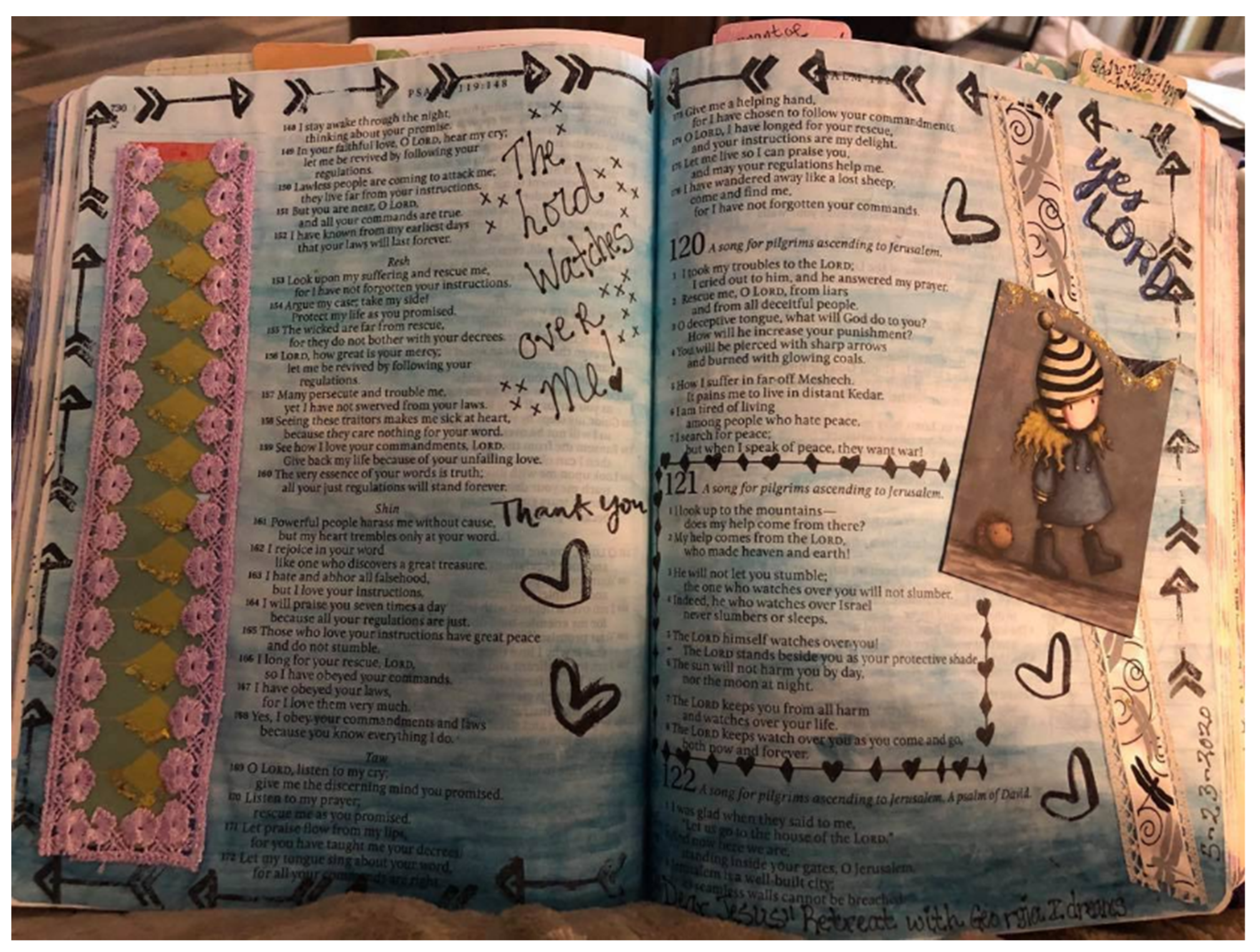

3.2. Practice

I have a few different Bible journals that I use.4 I have the Inspire Prayer, the original Inspire, the Psalms/Proverbs Illustrating Bible, and the original Illustrating Bible, and various notebooks. I usually journal every day. When journaling, it just depends, I pray around it [Bible]. I have a devotional that I use, and sometimes I open the Bible to a random page and read and then select the verses that speak to me on that day. Sometimes, I select a text from my devotional, other times it’s as simple as seeing a post on Facebook with a verse that jumps out at me.

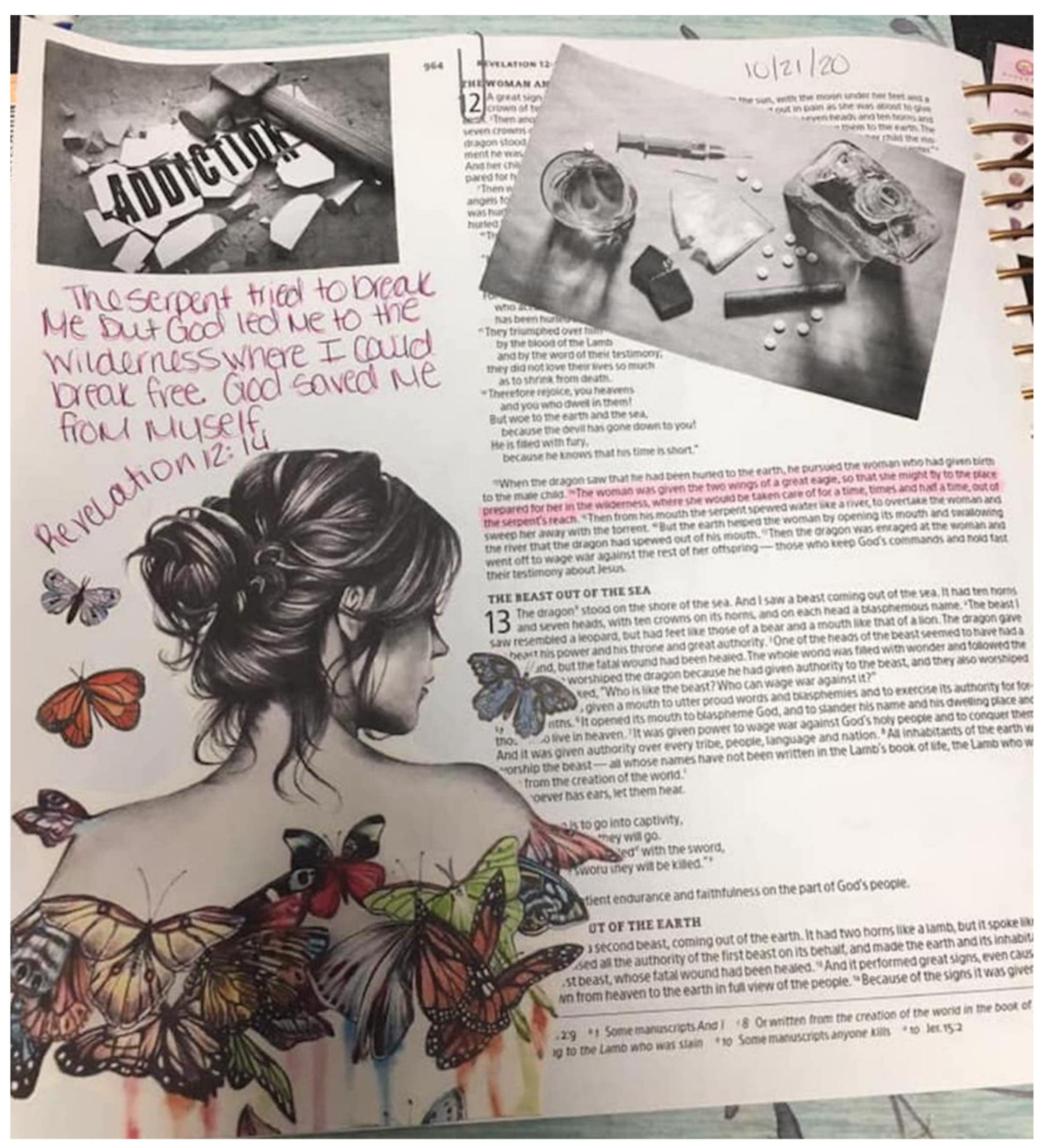

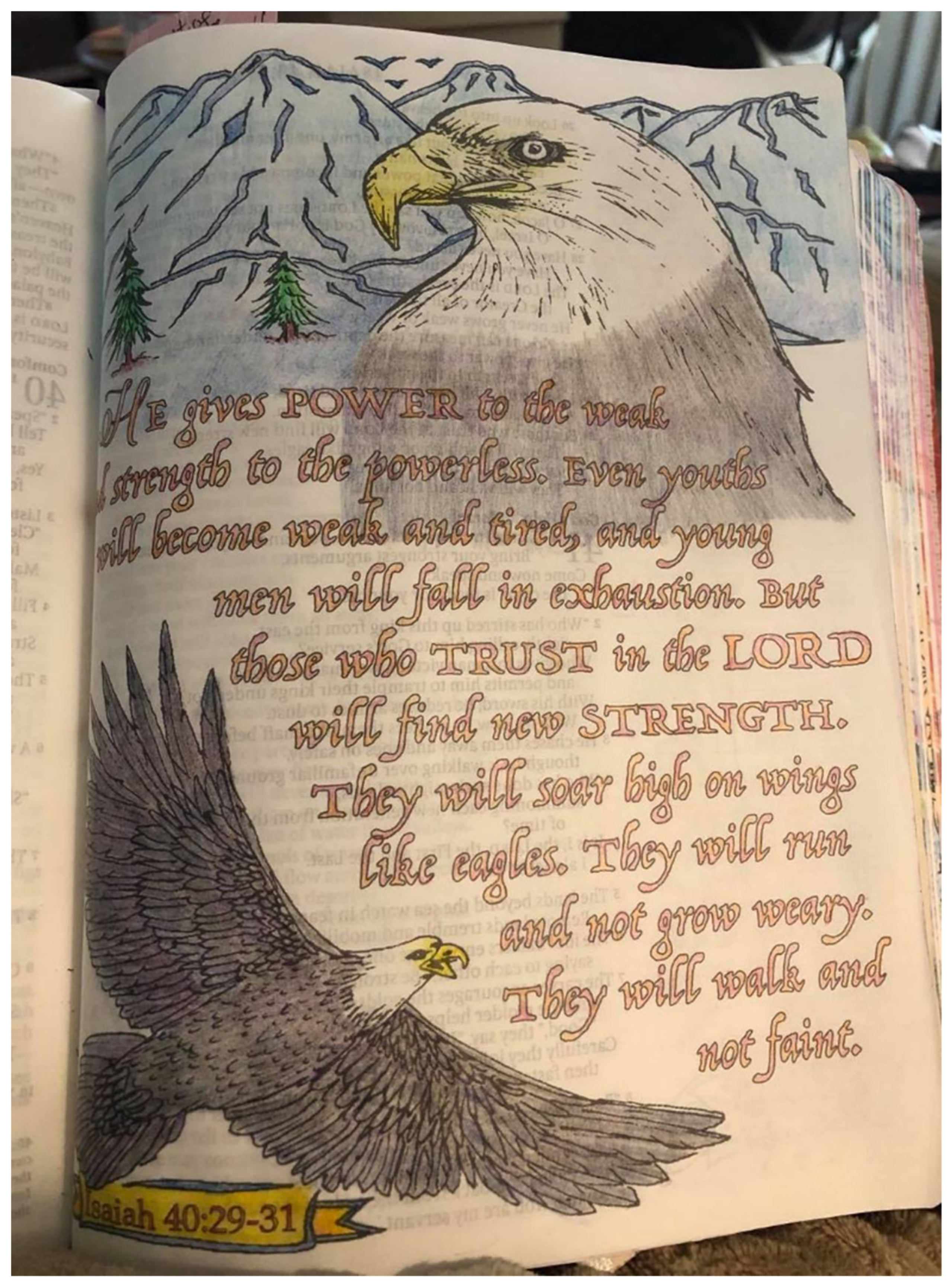

4. A Multimodal Analysis of a Bible Journaled Page

4.1. Thick Description

The woman was given the two wings of a great eagle, so that she might fly to the place prepared for her in the wilderness, where she would be taken care of for a time, times, and half a time, out of the serpent’s reach”.

The serpent tried to break me but God led me to the wilderness where I could break free. God saved me from myself. Revelation 12:14.

4.2. Composition

4.3. The Word-Image Relationship

4.3.1. “Break”

The woman was given the two wings of a great eagle, so that she might fly to the place prepared for her in the wilderness, where she would be taken care of for a time, times, and half a time, out of the serpent’s reach.(Rev 12:14)

4.3.2. “Wilderness”

4.3.3. “Nourish”

4.3.4. Conclusions

4.3.5. And Then

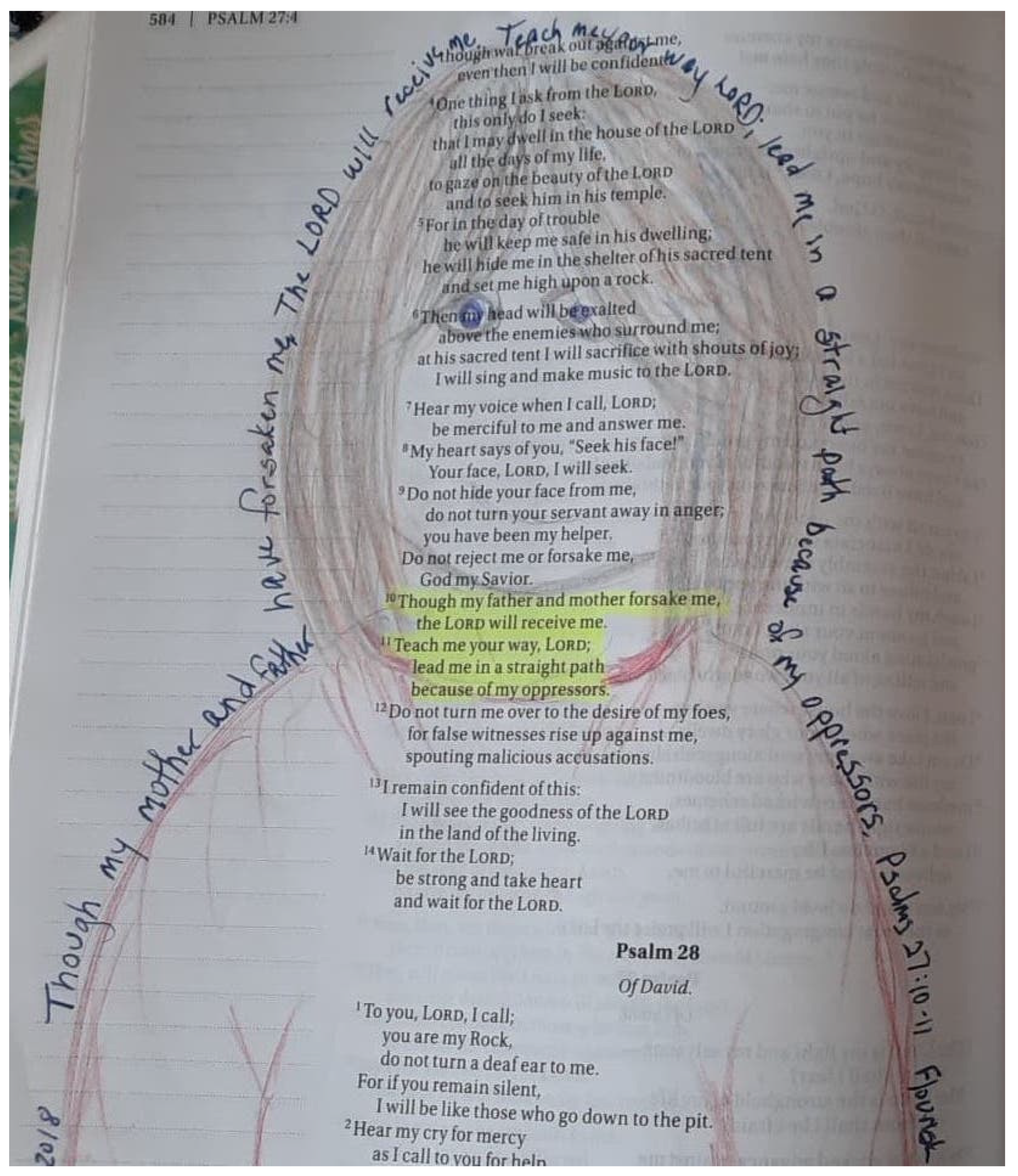

5. A Necessary Note on Trauma and the Bible

I believe journaling is God answering my prayers and showing me the answers he wants me to have. It is calming for me. My therapist has me journal everyday. Even if all I write is ‘life sucks’, ‘I wanna smoke’, ‘Anxiety is high’, ‘Pain hurts’, etc. It is me being real with where my thoughts are. My therapist and I have been able to uncover lies I believed… such as because I was not a boy I was unlovable by God. Because I wrote my thoughts. Then she helps me change the lie with Scripture. It’s a long process but one I’m willing to do … must do in order for whole wellness.

She has helped me heal a childhood where my Sunday School teachers told me regularly I was “Satan’s child”… where my twin brother was the perfect child. Boys were the chosen ones in what I grew up with. It contributed to my addictions to numb the feelings.

6. Limitations to This Study and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Our images reveal that we are holographic creatures, living multiple stories.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The Bible, as it exists today and is named and discussed in this article, consists of three parts: the Hebrew Bible, the Apocrypha, and the New Testament. The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh contains the canonical collection of Hebrew Scriptures, including the Torah (“Teaching”), Nevi’im (“Prophets”) and Ketuvim (“Writings”), composed between roughly 900 BCE (possibly later) and 160 BCE in Hebrew or Aramaic. The Hebrew Bible shares much of its content with its ancient Greek translation, known of as the Septuagint. It is important to note that these texts predate the emergence of Christianity and the Christian writings of the first and second centuries CE. The Hebrew Bible is also venerated by Christians. It came to form the first and larger part of the Christian Bible and is referred to as the Old Testament, in the Christian Bible. Within Christianity, the Roman Catholic church, Eastern/Greek/Ethiopian Orthodox churches and some Protestant churches recognise and include varying numbers of additional books as belonging to a second division, within the OT, named the Apocrypha. There are many differing traditions across denominations and religious groupings concerning which books belong in the canons of Scripture. The New Testament consists of 27 books. It was composed and redacted over a period of about a century, by diverse authors, in Greek, between about 40 CE and 140 CE. It was recognised as a canon of Scripture formally in the Christian church in the fourth century. The Bible contains texts recognised as divinely inspired by adherents of Judaism, Christianity, Islam and other faiths. |

| 2 | Percocet 30 mg. Percocet is a medication used to help relieve moderate to severe pain. It contains an opioid pain reliever (oxycodone) and a non-opioid pain reliever (acetaminophen). |

| 3 | The 12 step programme has many strong advocates within the addiction recovery literature, including from those who vouch for it enabling spirituality to be factored into a holistic approach to and for the person in recovery (see Plante 2018; Rohr 2011; Ringwald 2002). Others, however, are critical of this method and how the spiritual dimension is dealt with (see Szalavitz 2019). |

| 4 | Bible journaling has proven extremely lucrative for the publishing industry. Almost every US Bible publisher now offers many versions of a journaling Bible. Many popular translations are available as a journaling Bible, including but not limited to CSB, ESV, GNT, NAB, NIV, NKJB, NLT and NRSV, and where relevant, include Catholic editions. Some publishers have a multiplicity of versions, packaged in a variety of formats, targeted at different demographics. Some publish selected books of the Bible, such as the Psalms and Proverbs, separately. Journalers’ choices are made based on both preferred translation as well as the attractiveness and functionality of the book design. Comparing and contrasting these many different translations and editions are frequent topics of discussion in the many dedicated social media groups. Many journalers have more than one Bible journal ‘on the go’ at any one time, sometimes preferring one translation of a particular text over another. Some journal a Bible as a gift. One woman, not included in this study, was journaling her journey through drug addiction recovery as a legacy she would be handing on to her children in time, in order that they might understand what she been through and how these texts had shaped her recovery. |

References

- Adams, Kathleen. 2004. Scribing the Soul: Essays in Journal Therapy. Denver: Center for Journal Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Bruce K. 2008. The Globalisation of Addiction: A Study in Poverty of the Spirit. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Pat B. 1995. Art is a Way of Knowing. Boston: Shambala. [Google Scholar]

- Andermahr, Sonya, and Silvia Pellicer-Ortín. 2013. Trauma Narratives and Herstory. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolos-Cappadona, Diane. 2020. A Guide to Christian Art. London: T&T Clark Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, Beth Allison. 2021. The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth. Ada: Baker Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Beal, Timothy. 2012. The Rise and Fall of the Bible: The Unexpected History of an Accidental Book. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Bedi, Ashok, and Joseph H. Pereira. 2020. The Spiritual Paradox of Addiction, The Call for the Transcendent. Lake Worth: Nicholas Hays, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Budd, Luann. 2002. Journal Keeping, Writing for Spiritual Growth. Downers Grove: IVP. [Google Scholar]

- Burrus, Virgina. 1999. An Immoderate Feast: Augustine Reads John’s Apocalypse. In History, Apocalypse, and the Secular Imagination: New Essay’s on Augustine’s City of God. Edited by Mark Vessey, Karla Pollmann and Allan D. Fitzgerald. Bowling Green: Philosophy Documentation Centre, pp. 183–94. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, Aimee. 2020. Recovering from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood: How the Church Needs to Rediscover Her Purpose. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. [Google Scholar]

- Cepero, Helen. 2008. Journaling as a Spiritual Practice: Encountering God Through Attentive Writing. Downers Grove: IVP. [Google Scholar]

- Claassens, L. Juliana M. 2020. Writing and Reading to Survive: Biblical and Contemporary Trauma Narratives in Conversation. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeWeerdt, Sarah. 2019. Tracing the US opioid crisis to its roots. Nature 573: S10–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dillon, Amanda. 2020. Be Your Own Scribe: Bible Journaling and the New Illuminators of the Densely Printed Page. In From Scrolls to Scrolling: Sacred Texts, Materiality, and Dynamic Media Cultures. Edited by Bradford A. Anderson. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 157–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etherington, Kim. 2008. Trauma, Drug Misuse and Transforming Identities. A Life Story Approach. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Melissa, and Kate Peiffer. 2019. Bible Journaling for the Fine Artist. Mission Viejo: Quatro. [Google Scholar]

- Gibney, Alex. 2021. The Crime of the Century. HBO Documentary. Available online: https://www.hbo.com/documentaries/the-crime-of-the-century (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Grisel, Judith. 2019. Never Enough: The Neuroscience and Experience of Addiction. London: Scribe. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, James. 1994. Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Sumayah. 2016. What is Quran Journaling? How do you set up your Quran Journal? November 27. Available online: https://www.recitereflect.com/what-is-quran-journaling/ (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Hieb, Marianne. 2005. Inner Journeying Through Art-Journaling: Learning to See and Record your Life as a Work of Art. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, Carey. 2014. An Introduction to Multimodality. In The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis, 2nd ed. Edited by Carey Jewitt. London: Routledge, pp. 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Brian C. 2009. Wilderness. In NIDB. Nashville: Abingdon, vol. 5, pp. 848–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kobes Du Mez, Kristin. 2020. Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation. New York: Liveright. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. 2021. Reading Images, The Grammar of Visual Design, 3rd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, Alison. 1995. Telling Our Stories: Wrestling with a Fresh Language for the Spiritual Journey. London: Darton, Longman and Todd. [Google Scholar]

- Lukinsky, Joseph. 1990. Reflective Withdrawal Through Journal Writing. In Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood: A Guide to Transformative and Emancipatory Learning. Edited by Jack Mezirow and Assoc. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Maisel, Eric, and Susan Raeburn. 2008. Creative Recovery, A Complete Addiction Treatment Program That Uses Your Natural Creativity. Boulder: Trumpeter. [Google Scholar]

- Massyngberde Ford, J. 1975. Revelation. AYB. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maté, Gabor. 2018. In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction. London: Vermillion. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, Marion. 1986. A Life of One’s Own. London: Virago. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, Jennifer A. 2004. A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning: Theory and Practice. London: RoutledgeFalmer. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols Hickman, Lisa. 2013. Writing in the Margins: Connecting with God on the Pages of Your Bible. Nashville: Abingdon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ó Tuama, Pádraig. 2015. In the Shelter: Finding a Home in the World. London: Hodder and Stoughton. [Google Scholar]

- Peace, Richard. 1995. Spiritual Journaling: Recording Your Journey Toward God. Colorado Springs: NavPress. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker, James W. 2004. Writing to Heal: A Guided Journal for Recovering from Trauma & Emotional Upheaval. Denver: Center for Journal Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- Plante, Thomas G. 2018. Healing with Spiritual Practices: Proven Techniques for Disorders from Addictions and Anxiety to Cancer and Chronic Pain. Santa Barbara: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Progoff, Ira. 1975. At a Journal Workshop: Writing to Access the Power of the Unconscious and Evoke Creative Ability. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Progoff, Ira. 1983. Life-Study, Experiencing Creative Lives by the Intensive Journal Method. New York: Dialogue House. [Google Scholar]

- Ringwald, Christopher D. 2002. The Soul of Recovery: Uncovering the Spiritual Dimension in the Treatment of Addictions. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Rohr, Richard. 2011. Breathing Under Water: Spirituality and the Twelve Steps. Cincinnati: St Anthony Messenger Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schüssler Fiorenza, Elizabeth. 1991. Revelation: Vision of a Just World. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Stoicea, Nicoleta, Andrew Costa, Luis Periel, Alberto Uribe, Tristan Weaver, and Sergio D. Bergese. 2019. Current perspectives on the opioid crisis in the US healthcare system. A comprehensive literature review. Medicine 98: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stulman, Louis. 2014. Reading the Bible through the Lens of Trauma and Art. In Trauma and Traumatisation in Individual and Collective Dimensions: Insights from Biblical Studies and Beyond. Edited by Eve-Marie Becker, Jan Dochhorn and Else K. Holt. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, pp. 177–92. [Google Scholar]

- Szalavitz, Maia. 2019. Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction. New York: Picador. [Google Scholar]

- Theroux, Louis. 2017. Dark States—Heroin Town. BBC Documentary. Available online: https://www.bbcstudios.com/case-studies/louis-theroux-dark-states-heroin-town/ (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Thompson, Leonard L. 1997. The Book of Revelation: Apocalypse and Empire. Oxford: OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, Len. 2008. Multimodal Semiotics: Functional Analysis in Contexts of Education. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, Theo. 2005. Introducing Social Semiotics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yarbro Collins, Adele. 1979. The Apocalypse. Dublin: Veritas. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dillon, A. Bible Journaling as a Spiritual Aid in Addiction Recovery. Religions 2021, 12, 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110965

Dillon A. Bible Journaling as a Spiritual Aid in Addiction Recovery. Religions. 2021; 12(11):965. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110965

Chicago/Turabian StyleDillon, Amanda. 2021. "Bible Journaling as a Spiritual Aid in Addiction Recovery" Religions 12, no. 11: 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110965

APA StyleDillon, A. (2021). Bible Journaling as a Spiritual Aid in Addiction Recovery. Religions, 12(11), 965. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110965