1. Introduction

On 30 August 2021, US troops completed the comprehensive withdrawal from Afghanistan, adding the final nail to the coffin of twenty years’ war with the Islamist Taliban, who had reseized power two weeks prior. Underpinning the longest war on foreign soil in American history are century-long interactions and conflicts between secular and religious actors across the world. The secular/modern international relation owed its evolution to the Christian Protestant Reformation, which redefined the locus of political and economic authority and presented the new possibility of the state capacity in the western hemisphere. From the Iranian Islamic Revolution (1978–1979) to various ethnoreligious conflicts within former Yugoslavia (1991–2001) to the two-decade US Global War on Terror since 9/11, religion goes beyond the domestic level and transcends geographical, spatial, and cultural borders with wide-reaching and diverse impacts on world politics. Globalization, populism, and nationalism characterizing the twenty-first century further reflect on the church–state binary and bring forward the “post-secular international relation”, which both contextualizes and facilitates the worldwide resurgence of religion, elevating it to a novel plane of significance (

Haynes 2021;

Toft et al. 2011;

Thomas 2005). A concept “older than the state [with] its aims encompass[ing] not just politics but all of life”, religion remains central to policy making and is long perceived as “one of the basic forces of the social universe” (

Snyder 2011, p. 1;

Shah and Philpott 2011, p. 24).

Surprisingly, contrary to the support it receives among politicians, the “return” and “come back” of religion spark only a tepid response among scholars of international relations (IR). A field privileging nation states as the sole unit of analysis and major foci of attention under the Westphalian worldview, IR stays vigilant against the “discover” and “rediscover” of faith-based organizations (FBOs) and individuals accompanying the global religious revival, which challenges states’ monopoly of violence and decision-making procedure at both domestic and international levels (

Haynes 2013;

Thomas 2005;

Philpott 2002;

Berger 1999;

Kulska 2020). Further exacerbating this Westphalian prejudice was the Enlightenment assumption embedded in the social sciences, which uphold the teleological assumption of modernization and consistently proclaim irreconcilable barriers between the superior secular sector and the primordial religion, the antithesis of human rationality comprised of nothing but “myths” (

Cavanaugh 2009), “fairytales” (

Thomas 2005), and “legends” (

Barnett 2015). While scholars attempt to transfer the secular–religious dichotomy into the novel diverse symbiosis ranging from international political theology (IPT), religious soft power, to the socially and historically constructed secular division, stigmatization and infantilization continue to loom over the literature on religious actors in armed conflicts, peacebuilding, and international development (

Appleby 2000;

Kubálková 2000,

2003;

Mandaville and Hamid 2018;

Haynes 2021). The explicit reductivist perception prevails among ongoing debates on whether religion manifests as a power of virtue or evil, thereby oversimplifying this distinctive factor as either an iconoclastic free-rider irrelevant to the international order or an explicit outlier incompatible with the world that deserves being disregarded. Consequently, the predatory “ontological injustice” puts religion into a paradoxical scenario. Albeit “stand[ing] at the center of international politics”, it is “barely consider[ed] by realism, liberalism, and constructivism in their analysis of political subjects” (

Toft et al. 2011;

Snyder 2011;

Wilson 2017). The intriguing question remains: how can religion interact with and affect the outcome of international relations? How should scholars relocate marginalized and overlooked religion squarely into conventional IR theoretical paradigms? What adaptations and innovations should the IR discipline make in response to the global religious resurgence in a post-secular world?

This essay examines this question in the context of a popular yet often undertheorized concept: religious soft power. The existing literature pioneered by

Haynes (

2010) emphasizes the role of transnational religious actors in shaping the identity, values, and norms of their global audience, which influence national foreign policy and are central to the reinforcement or dysfunction of the existing international system (

Jödicke 2018;

Öztürk 2020,

2021;

Mandaville and Hamid 2018;

Steiner 2011,

2016;

Ciftci and Tezcür 2016;

Haynes 2010). Despite being the “most currently influential approach to the topic”, religious soft power is often criticized for its ambiguity and the underexamined religion–power relation (

Kearn 2011;

Haynes 2021). To fill in this theoretical and empirical lacuna, this essay expands the current literature and proposes a multidisciplinary crosscut between IR and political sociology to further scrutinize and conceptualize the performative, discursive, and relational dimensions of the single source of religious soft power under

Reed’s (

2013) and

Mann’s (

1992,

1993) classic typology of the source of power. It commits to present an analytical model to enumerate motivations, mechanisms, and circumstances experienced by transnational religious actors, which are often marginalized and excluded from the international norm/rule-making procedure. Through the constructivist lens, this essay integrates literature on soft power, international norm, and sociological theories and examines the schema of three-dimensional religious soft power by applying the process-tracing method to the empirical case of faith-based evangelical US foreign policy in the post 9/11 Bush administration. The finding suggests that conservative evangelical groups’ manufactured reality of the clash of religion and civilization, infiltration into political systems, and localization and politicization of top-down religious messages correspond to the discursive, performative, and relational dimension of the religious soft power obtained by the evangelicals, who seized the Grotian moment to inject their identity, ideology, and interests into US foreign policies on international human rights and the Global War on Terror.

This typology contributes to the project of power by recalibrating a model to integrate systematic shifts on the international level with the process-level ideological reorientations and political cleavages on the domestic level, all of which facilitate the creation of the new language of religion that transfers religious actors’ perception of their identity, stakes, values, and issues of competition. It brings forward the three-fold contributions. Empirically, this detailed account brings forward multilingual and multi-archival evidence on evangelical groups’ economic, military, and political operations behind the US Global War on Terror. Theoretically, the enrichment and diversification of power, a concept embraced by realism, liberalism, and constructivism with different priorities, provides a solution to position religion back to the IR discipline (

Gallarotti 2010). Without the ambition to propose a complete synthesis among these major paradigms, the three-dimensional religious soft power indeed foregrounds the potential for the refinement of, communications among, and even integration of different theoretical frameworks. Moreover, religion as both a political and social factor renders the interdisciplinary attempt a necessary move to overcome the theoretical insufficiency of IR, which stubbornly upholds theoretical autonomy and rigid “academic division of labor” with comparative politics, leaving the discrepancy between our comprehension of international and domestic politics (

Caporaso 1997). Integration of IR and political sociology not only explores the balance between empiricism and rationalism from the macro perspective but also presents a potential approach to compare, contrast, and coordinate levels of analysis, agents–structures binary, systematic theory, reductionism, and other key methodologies on the micro-level (

Han and Zhao 2018). Politically, as we enter the third decade of the twenty-first century, which witnessed the emergence of religious essentialism and violent extremism, a deep dive into the transnational religious civil society enables both scholars and policymakers to understand challenges and opportunities associated with faith-based organizations’ material, normative, aspirational, and strategic claims over global order and politics, thereby dismantling the oversimplified “religious threat theory” in the era of “the clash of civilization” (

Huntington 1996).

The examination of the three-dimensional religious soft power proceeds as follows. This essay begins briefly by reviewing the state of the art of soft power and religious soft power in the current IR literature. Addressing the theoretical and conceptual limitations, it proceeds to investigate Reed’s source-of-power model and illustrates the performative, discursive, and relational dimensions of religious soft power (

Reed 2013,

2019). The third section follows with an archive-based case study. The concluding section evaluates the rigor and applicability of the theory at hand and suggests possible future research agendas for scholars of IR, political sociology, and historical sociology.

2. Soft Power and Religious Soft Power in IR

First appearing in the work of Joseph Nye, Jr. (

Nye 1991,

2002,

2003,

2004), soft power is originally defined as nation states’ capacity for facilitating or preventing certain actions of target actors with no coercive or material approach but only attraction, co-option, and endearment (

Gallarotti 2010). Contrary to conventional hard power, which either raises the cost of incompliance with the use or threat to use military forces as a stick or elevates the benefits of cooperation with economic resources and leverages as carrots, soft power expands the foci of attention to both material and ideational factors, introducing the alternative possibility of social pressure, status politics, and identity competition encompassed within the co-opting mechanism (

Mantilla 2017;

Bower 2015;

Towns 2012;

Hathaway 2002;

Chayes and Chayes 1993;

Acharya 2018). There exist three major sources of soft power: “the attractiveness of a country’s culture”, the achievement of its “political values at home and abroad”, and the perception of its “foreign policies as legitimate [with] moral authority” (

Nye 2004, p. 11). It is difficult to overstate that soft power falls most squarely into the constructivist framework. However, as

Gallarotti (

2010) and

Kearn (

2011) accurately illustrate, the delicate integration of material interests, the key priority of states striving for survival, interest seizure, and power augmentation under the anarchic international system in the eyes of realists and liberal institutionalists, and ideational factors including values, norms, identity, and social structures privileged by constructivists, foregrounds soft power’s potential paradigmatic synthesis and contributes to the increasing popularity and utility of this concept among IR scholars and politicians. Among them are researchers striving to unravel religion’s influence on foreign policy and for international politics to admit the global religious renaissance.

It is precisely within the purview of the post-secular turn of IR that emerges the novel concept of religious soft power, which witnesses both the “thinning”, fading, and “increasing porousness” of national boundaries and the rise of transnational civil society out of cultural globalization, whose spill-over effect accounts for increasing dissemination and attractiveness of both material and ideational factors of the religiosity (

Rudolph 2005;

Toft et al. 2011;

Barbato and Kratochwil 2009). Given its capacity to constitute and shape the culture, identity, attitudes, and policy preference of both religious groups and nation states, religion soon comes under the spotlight and is recognized as a novel and significant form and/or resource of soft power. The diversification of actors and currencies of power in international affairs prepares scholars pioneered by

Haynes (

2010) to challenge Nye’s static state-centered approach and introduce transnational religious actors (TRAs) into the project of soft power, thereby advancing the concept of religious soft power. Religious soft power refers to an endeavored influence exerted by one side to facilitate or discourage performances of the other through demonstrating the legitimacy and necessity of religious identities, norms, and values. As

Haynes (

2016) famously articulates, “the idea of ‘religious soft power’ involves encouraging both followers and decision makers to change behavior because they are convinced of the appropriateness of a religious organization goals”. A concept encompassing many consequential elements from culture, state identity, attractions, policies, to institutions, it opens the window of opportunity for scholars to examine the intersection of identity formation, religious beliefs, and foreign policy, elements that are perceived as disconnected if not completely mutually exclusive through the lens of traditional hard power.

Buttressed by this conceptual revolution, scholars in this vein begin to dive deep into the TRA groups with the hope to examine their orientations, operational mechanism, and influences. Without the material inducement or military coercion, TRAs wielding religious soft power often rely on two claims to attract like-minded groups. First, they emphasize religion’s capacity of salvaging its followers long-oppressed or marginalized by either secular regimes or another religious majority, deriving ideational and normative attractiveness from believers’ crises of identity and representation. Second, they point to the urgent human rights concern such as Afghan refugees and argue that the Grotian moment has arrived for the religious community to uphold universal moral principles and transfer the political status quo fundamentally, modeling themselves the only appropriate solution indispensable for the wide-reaching and imminent crisis. After establishing a broad and solid audience base to generate the bottom-up momentums in political, economic, social, and cultural arenas (

Bean 2014), TRAs can also infiltrate into the policy-making procedure and persuade secular leaders to “incorporate religious beliefs, norms, and values into foreign policy” for the top-down religious influence, as demonstrated in scholars’ examination of Islam-informed foreign politics in Middle Eastern states and the Balkans (

Öztürk 2020,

2021;

Mandaville and Hamid 2018;

Ciftci and Tezcür 2016;

Haynes 2021;

Tarusarira 2020). This top-down and bottom-up religious soft power can further translate into an accountability mechanism applied by both the state and religious non-state actors (RNGOs) to reinforce transparency, responsibility, and liability in multinational coalitions and global governance (

Steiner 2011).

From altering monolithic perceptions of actors in IR to introducing the mechanism of attraction, religious soft power doubtlessly makes a substantial contribution to ongoing theoretical debates on political power and religious influence on domestic and international politics. However, a close examination of this concept sheds light on three major drawbacks that undermine its explanatory capability. First, religious soft power is a mere attempt to assemble two established and stylized concepts—TRAs and soft power—thereby rendering itself relatively ambiguous and undertheorized (

Kearn 2011;

Haynes 2021). Not only does it fail to specify the distinct and unique dimension of soft power developed under various religious contexts, but it also surprisingly overlooks mechanisms, strategies, and tactics used by religious actors to attract others to meet certain expectations, leaving the process-level dynamics unclear and underexamined for the specific co-opting procedure. The intriguing question of why and how the TRAs choose and wield religious soft power is still not sufficiently addressed. Second, as

Kearn (

2011) insightfully discerns, the model of attraction or endearment underlying the religious soft power argument suffers from three key flaws. On the one hand, while religious soft power comprises both passive influences of preferences and values through persuasions and active “manipulat[ion] of the agenda of political choices” and outcomes (

Nye 2004, p. 7), attraction theory often omits the latter and increases the risk of “conflating … the use of soft power with the attractiveness of specific policies” (

Lukes 2005), thereby undermining the conceptual integrity and predictability. On the other hand, as the model of attraction implicitly brings forward a positive connotation and attitude toward religious actors, scholars may overlook the Janus faces of the TRAs, which are not necessarily the forces or either good or evil but can contain both benign and malign influence simultaneously. Additionally, the process of attraction is relational and context-sensitive which involves both leading actors and influences recipients/receivers. Complex interdependence and confrontations among actors with different levels of agency and autonomy often result in various two-way socialization, cultural appropriation, assimilation, and complete imitations, all of which fall on the sophisticated “spectrum” that cannot be fully captured by the simple model of attraction (

Bloomfield 2016). Third, similar to soft power, religious soft power faces the same difficulty of demarcating material resources from their ideational counterparts, thereby blurring the line between itself and conventional hard power. As globalization “elides borders and challenges identities (and privileges) tied to place” (

Lake et al. 2021), the rise of unconventional violence and warfare alter our knowledge of military might and economic capacity, while the world witnesses the securitization discourse, ideology, culture, and national identity, symbolizing the gradual hardening of traditional soft power elements. Once the TRAs begin to acquire more hard power in the post-secular world, whether religion can still remain under the category of soft power is subject to further debates and discussion, let alone the conceptual legitimacy and applicability of religious soft power.

To sum it up, albeit scholars’ active attempts to relocate religious factors back to analysis through extending the soft power concept to include transnational religious actors, the innovative yet still burgeoning concept of religious soft power suffers from the underdeveloped religion–power relation, the problematic mechanism of attraction, and the ambiguous boundary between itself and hard power. It is therefore theoretically promising to conceptualize the process of the application of religious soft power and to specify motivations, contexts, mechanisms, and tactics of relevant actors, who endeavor to alter the outlook of international politics and foreign policies. As detailed in the next section, an effective yet often overlooked method to further scrutinize and enrich religious soft power is to integrate international relations with political sociology, a field long intertwined with IR, remaining a valuable source of alternative theories, perspectives, and methods.

3. The Three Dimensions of Religious Soft Power: Performative, Discursive, and Relational

While IR repeatedly emphasizes its academic independence as a distinct branch of social science, it seldom denies the intimate connection to sociology. Just as

Weber (

2001),

Marx and Engels (

1967), and

Durkheim (

1965) who strived to “search for order in the broken fragments of modernity”, their counterparts in IR exemplified by

Waltz (

1979),

Wendt (

1999), and

Cox (

1986) also try their utmost to unravel the underlying rule of domestic and international societies (

Benjamin 1999). The common goal of exploring the fundamental order enables the young IR discipline to turn to sociology for conceptual and theoretical inspirations. Specifically, the famous Waltzian concept of international hierarchy and anarchy takes roots in Durkheim’s investigation of organic and mechanic solidarity and social order associated with the advancement of modernity, although scholars have long debated whether Waltz has mismatched and “misappropriated” these two pairs of concepts (

Lawson and Shilliam 2010;

Rosenberg 2013;

Griffiths 2018). The analogous theory production and borrowing of the shared language of disciplines result in a wide-reaching sociological imprint on the groundwork of IR paradigms, ranging from structural realism to constructivism. Meanwhile, the end of the Cold War facilitates the “third debate” of IR and witnesses the impulse of supplementing the dominant positivism with various sociology-oriented methods such as critical theory, social constructivism, and reflexivism (

McSweeney 1999). Further presented by the penetration of sociology in IR, according to

Lawson and Shilliam (

2010, p. 681), are three valuable analytical perspectives: “classical social theory, historical sociology, and Foucauldian analysis”. Given these theoretical, ontological, and methodological legacies, it is reasonable to argue that a sociological revisit and extension of religious soft power warrants our attention.

Power is a central, subfield- and discipline-organizing concept in sociology, and as a result, the way in which theorists parse, typologize, conceptually delimit, or otherwise comprehend power has consequences for empirical research and the truth claims that result from it (

Reed 2013, p. 195). A concept that “stands out as one whose definition is particularly contentious and unstable” (

Poggi 2006, p. 464), power has instigated a century-long theoretical debate in sociology, which unfolds into four consecutive stages. Weber’s definition of power as “chances of” a group of actors to actualize their “own will in a social action even against the resistance” of other participants marked the beginning of the first stage, which was characterized by the multiplicity of definitions (it includes three similar concepts of power, authority, and domination) (

Weber 1946,

1978). The conception of power pioneered by

Dahl (

1957),

Dahrendorf (

1958), and

Parsons (

1963) centered around two predominant categories: the empowerment model, which interpreted power as absolute capacity enjoyed by certain actors, and the domination model, which perceived power as relational influences exerted by the advantaged haves over the subordinate have-nots (

Reed 2013). After the initial specification of scope and context, scholars entering the second stage demonstrated strong interests in sources of power. A systematic summary of sociological theories along this trajectory can be found in the work of

Lukes (

1975), who traced the development of

Dahl’s (

1957) first dimension of power (pluralistic decision making as the single source),

Bachrach and Baratz’s (

1970) two-dimensional sources to include both decision-making and non-decision-making scenarios, and his third dimension of ideation and subjectivity as the source of power. The second stage of power also includes structuralist factors, which also have an impact on contemporary power discussions, such as functional separation of powers (

Chen 2020), exchange and power (

Jessop 1969), and state power (

Skocpol 1979). The three-dimension model was further modified by

Scott (

1996) and

Poggi (

2006), who recognized the political, economic, and ideational/normative power. Even more groundbreaking and widely acknowledged were ideological, economic, military, and political powers developed by

Mann (

1993), or the IEMP mechanism. The third stage presented the Foucauldian understanding of power, which emphasized its autonomy and agency and constituted the fourth dimension, providing scholars with a more complex puzzle hinging on the intersubjective perception and mutually constitutive relations between powers, agents, structures, and discourses (

Foucault 1980). The fourth or the current stage of discussion featured the work of

Reed (

2013,

2020), who interpreted power as the capacity of “making something happen”. The power–causality matrix consequently sheds light on the dimensional understanding of the single source of power, which comprises the performative, discursive, and relational components.

Consequently, this section applies the three-dimensional typology to the religious soft power with the aim to explore the scope, weight, and means of applications of each dimension. Mechanisms, actors, and influences of the performative, discursive, and relation religious soft power are elaborated in detail and summarized in

Table 1 at the end of this section.

3.1. Performative Dimension of Religious Soft Power

The performative dimension of religious soft power refers to the actions and practices of an actor who engages in certain behaviors, carries out the process, and delivers the outcome of particular events. While performance often incorporates both discourses and practices, it emphasizes more the latter and pays more attention to application and actualization rather than the substance of a claim or proposal, prioritizing the procedure of “walking the talk”. In other words, performance entails the procedure to rationalize discourse and claims proposed by actors, who engage in various practices of making ideas intelligible and acceptable to the recipients. The outlook of a performance manifests in two contradicting ways. First, actors can choose to engage in a regulatory repetition of certain “historically contingent” actions, which are originally neutral with no specific purpose but gradually become naturalized, fixated, routinized, and even ritualized through this repetitive performance of actions, which in turn brings certain facts and influences into existence (

Austin 1979;

Butler 1993;

Campbell 1998;

Braun and Clarke 2019). The “hidden and insidious” practice can evolve into habits, customs, and rules among participating actors and communities, who begin to take the performance for granted and follow the logic of appropriateness to follow suit and comply (

Reed 2013). Second, the performance can make a groundbreaking and norm-challenging theatrical scene. A sudden deviation of every day’s mundane routines carried out by a group of actors can ridicule the status quo and generate alternative realities, which alter the repertoires of meaning for the audience to contemplate and interpret (

Alexander 2006;

Schechner 2004). Since performance is also context-sensitive, the temporal and spatial order matters for the outcome and effectiveness of a performance (

Reed 2013). Achronological actions can precede fundamental revolutions, whereas a single sparkle in various states has the ability to spark a prairie fire across the globe. Meanwhile, it is worth mentioning that whether the performance comes out successfully does not necessarily have an influence on its effectiveness. A triumphant performance faces the risk of being overlooked and marginalized, whereas the miscarriage of an attempted practice may become the martyr that encourages a fundamental change in the long run.

In general, a performance encompasses key stages of actor presentations, message instantiation and communications, and audience receptions. These scenarios in turn advance three specific mechanisms applied by transnational religious actors to expand their sphere of influence. First, actors’ presentations can take place both frontstage and backstage. Whereas the former features the formal, instant, and direct interactions between specific actors and audiences, the latter concentrates on the informal, diffuse, and indirect communications delivered by the institution or the social structure. In frontstage performance, actors deliver personas and messages designed by the script with the help of the physical setting (

Goffman 1959). They can work on “appearance, conduct, and expressions [they] give and give off” to emphasize the realness and genuineness of the performance, thereby establishing a resonance between the scene and past experience of the empathetic audience, who consequently demonstrates recognition and support of actors (

Cook 2013). Under the classic typology of power by

Barnett and Duvall (

2005), close and direct connections between performers and the audience equip the former with compulsory power over the latter. Second, backstage without established subjective characters and physical props and scenery, actors derive their ability to persuade through the institutions they belong to. For instance, a Christian pastor after his or her Sunday mass is still a representative of the Church and the religiosity. Key messages and principles can still be disseminated through certain “dress, speech patterns, and body language” (

Cook 2013), which symbolize collective identities and norms of institutions and communities. Third, since religious actors exist both as performers and general audiences, they can facilitate the localization and socialization of religious norms delivered by the performers. On the one hand, believers in the audience can emphasize common sufferings and experiences between performers and the local community, shaping the external religious principle as a useful method to reinforce the legitimacy and efficiency of local authorities (

Acharya 2004). On the other hand, religious actors can highlight peer pressure, social opprobrium, and status competitions faced by the audience, who strives to obtain the ingroup identity and often finds the cost of rejection too high in the socialization process. Compared to the instant compulsory power exerted by the frontstage and backstage performance, audience infiltration gives religious actors considerable structural and institutional power to influence the community through diffuse processes (

Barnett and Duvall 2005).

Performative religious soft power shapes outcomes of domestic and international politics through three approaches: constituting identities and selfhood, maintaining the agency and ontological security, and reinforcing legitimacy and representation between actors and the audience. To begin with, the ontological existence and identity of a subject derive more from the “stylized repetition of acts” than “a founding act” (

Bell 1999). The action of repetition evolves into a particular norm enjoyed by the identity owners, who extract certain fundamental values from the logic behind the naturalization of this repetitive procedure. Consequently, repetitive performance as “a sign of power and powerlessness” advances the principle of difference in relation to which the identity constitutes and grows into the criteria of selfhood which demarcates the boundary between the insiders and outsiders, with the former enjoying substantial exclusive rights and privileges (

Campbell 1998;

McKinlay 2010). The moral superiority, together with the higher status in the international society, may further raise the attractiveness of certain identities, whose owners can utilize and co-opt “B to do something he would not otherwise do” (

Dahl 1957). Additionally, following the performative constitution of identity is the performative constitution of agency and ontological security, which describes agents’ “stable sense of self” and the subjective understanding of being (

Steele 2005;

Giddens 1984). Clear identities and routinized practice are two sources of ontological security of agents, who need to maintain the congruence between the subjective sense of selfhood and felicitous actions, and the absence of either component will lead to anxiety and a sense of insecurity of inaction (

Mitzen 2006;

Berenskoetter 2020). Since religious leaders and actors can alter repetitive practices and redraw the us-versus-them boundary in response to both endogenous ideational contradictions and exogenous systematic change, their performance remains central to ontological security of the entire community, thereby enjoying considerable agency and autonomy to alter outlooks of states’ foreign policy. Furthermore, since both secular and religious actors shoulder the tasks to represent both material interest and normative values of citizens of nation states, competition for legitimacy and leadership remains a central theme for the secular–religious contention. The repetitive attempts and claim of defending identities of the religious minority, restoring equity among the religious haves and have-nots, and ensuring efficiency in adequate problem resolutions strengthen religious leaders’ ability to control the hearts and minds of the audience. When believers sense potential threats to both their survival and ontological security, they will gravitate to the religious sector, which “performs agency through the securitization and establish [itself] as the designated” representative (

Braun and Clarke 2019), thereby marginalizing the secular counterpart, whose policies fail to protect from faith-based principles.

3.2. Discursive Dimension of Religious Soft Power

While the performative dimension concentrates more on practice repetition and actualization of claims on the macro level, the discursive dimension in contrast zooms into the process level and prioritizes the understanding of and making of claims. Owing its popularity largely to

Foucault (

1980), discourse describes the system in which meaning, perception, conceptualization, and ideas of certain subjects are addressed and delivered in a certain way to explain, predict, and prescribe relative actions in the reality, which further functions as contexts to constitute and influence the operation of the entire system. Core elements of discourses are the creation of meaning and knowledge, the system of signification, and “discursive productivity” (

Milliken 1999). Cognitive discourses are the ones specifying existence, ontological status, and content of factual and social reality. They are responsible for clarifying the frontier of know-how and drawing the boundary between the perceived and unexplored knowledge, thereby known also as the birthplace and repository of meaning. The establishment of factual and physical reality is followed by the normative construction of meaning, which matches material realities with value judgments. The process behind this normative discourse is the system of signification that categorizes subjects according to different signs, “written or oral, visual or auditive” (

Epstein 2008). Normative discourses place realities to the system of signs for classification and often present dichotomous categories—imaginable versus unimaginable, natural versus constructed—which implies a power asymmetry that “privileges … one element in the binary” (

Derrida 1981). In addition to its descriptive and explanatory aspect, discourse contains a distinctive element of productivity and constitution. On the one hand, it can scrutinize the methodology, ontology, and epistemology of individuals, society, and even the entire human beings. The control of the “habitual way of society thinks” advances the creation of common sense, or “naturalized” subjects which are taken for granted, “evacuated with historical contingency … [without] alternative meanings” (

Epstein 2008;

Bourdieu 1983). On the other hand, the monopoly of meaning-creation and naturalization of reality and statements further equips discourse with the power to identify the qualified, knowledgeable, and authorized “subject to speak and to act” (

Keeley 1990). Not only do discourses obtain the right and power to write the rules, norms, and values, but they can now determine who have the right to produce and execute these “standards of normality” (

Weber 1998), thereby preserving the right to interpret, maintain, transform, and abolish the physical and social realities.

How does discursive religious soft power contribute to foreign policy change? First, religious actors can rationalize their impetus of policy change through an interpretation of incidents in hand, shaping the scenarios into an architected reality that tilts the power balance toward their side. When religious actors are entrepreneurs of purported normative shifts, they can start by criticizing the infelicitous “situated creativity” and temporal dimension of the normative status quo and undermine the legitimacy and authority of local institutions (

Reed 2013). The emergence of a catastrophic crisis is so “radical and damaging” to the status quo that it constitutes a Grotian moment that both accommodates the systematic change and justifies the departure from the entrenched norms (

Bloomfield 2016). These state-of-emergency arguments thus enable religious actors to legitimately suspend the normal procedure and shift the psychological and evidentiary burden to the antipreneurs, who need to either successfully dilute the sense of imminence or find alternative approaches for crisis resolutions.

Second, religious actors can generate an innovative language of politics to reflect the reorientation of both ideational/normative factors and the material interests of the entire religious community. When observing the fluctuation in the international system that presents either material or ontological threats to their members, religious leaders have emotional and discursive power to not only capture “realities of revolutionary changes and conflicts” but also shape the audience’s perceptions of who they are and what issues and stakes they should pursue and compete around (

Chryssogelos 2021;

Hunt 1984). Consequently, it is not surprising to experience the insurgence of a hawkish and militarized position for a conventionally dovish religious group privileging international humanitarian development which now “wake[s] up to the … danger of [another] bloody, brutal type of religion and the clash of civilization” (

Baumgartner et al. 2008). The public opinions can further be translated into the outlook of foreign policy when the government pays special attention to the constituents to either fulfill the campaign promise or accumulate electoral support for incoming elections.

Finally, political language “emerged, elaborated, and interpreted” by religious discourse can exert considerable influence on the political culture of nation states (

Baker 1990). One of the most distinctive examples is the evangelical footprint on US fundamental foreign policy: American isolationism and exceptionalism. The city-upon-the-hill discourse in the founding myth reinforces the identity of the United States as “qualitatively different from other nations” due to its allegiance to liberty, dignity, and equality (

Amstutz 2013). It further frames this difference into a state of exceptionalism, which exempts the US to participate in international affairs and follow the shared rulebooks, gradually resulting in the US Isolationism that continued into the early twentieth century. This discourse of exceptionalism also enters the sphere of political morality, which attempts to “demonstrate to the world the habits, traditions, and values that contributed to the prosperity, liberty, and human dignity of American society” (

Amstutz 2013). The moral traditionalism and the us-versus-them evangelical worldview gradually evolve into the pursuit of a universal moral principle of liberty, democracy, and human rights, which account for the substantial annual budget allocated to the USAID, a foreign policy pillar often subject to partisan conflicts.

3.3. Relational Dimension of Religious Soft Power

Unlike the performative and discursive dimensions, which advance the property concept of power as possession of resources and acknowledge considerable agency acquired by actors in face of structural constraints, the relational dimension asserts that actors never operate in a vacuum and highlights embeddedness and positionality of actions in structured social relations. In a heterogeneous world entailing agents with different material, ideational, and normative capabilities, there exists a hierarchy that centralizes dominant actors and marginalizes newcomers with insufficient material and ideational resources and discourse power. Consequently, actors rooting in various relations face two major structural influences and constraints. First, the unequal distribution of resources, privileges, and capacities among different positions provides certain tactical and strategic advantages and disadvantages for felicitous agents at a particular spot. For instance, the working class residing on the peripheries experienced substantial exploitations under the traditional capitalist system, which allocated capacity and domination to the bourgeoise that enjoyed the disproportional privileges in the scope, weight, domain, cost, and means of power exercises (

Baldwin 2016). Second, in addition to material constraints, the dichotomous structure stressing the disparity and cleavages between the haves and the have-nots often suppresses the self-perception, cognition, and imagination of the latter, thereby depriving their normative resources and capacities. As

Lukes (

1975, p. 27) famously elaborates, a predatory structure with “the supreme and most insidious exercise of power prevent people … from having grievances shaping their perceptions, cognitions, and preferences in such a way that they accept their role in the existing order of things”. In order words, naturalizations and standardization of inequality and dispossession of the disadvantaged participants animate both external and internal entrapment of these agents, whose constrained daily practices and discourse further maintain and reinforce the entire system.

While positions of agents are multidimensional and should be best described as a flexible spectrum, their roles can usually fit in three categories: insiders of a community, rising newcomers, and principle-agents, each of which receives various distinctive strategic and tactical advantages to shape the policy outcome. Insiders of a community often enjoy substantial institutional, material, and discursive advantages in shaping the outcome of events. In

Haynes’ (

2013) categorization of transnational religious actors, the insider group corresponds to extended religious actors, which have usually established a concrete and well-developed transnational network and institution and demonstrated expansive interest in political, social, and cultural arenas. As exampled by the Roman Catholic Church, which remains a central insider of the global Catholic society, insiders of a community often occupy the gatekeeper position to monopolize the standard of normality and legitimacy and demarcate the line between us and them. They also enjoy substantial institutional advantage to accelerate or slow down purported policy change or even abolish and suspend the regular decision-making procedure.

In contrast, rising newcomers, or negotiated religious transnational actors in

Haynes’ (

2013) category, often lack the sophisticated cross-border base and strive to form the monolithic, “strong, and federated institutional structure” (

Levitt 2004, p. 8). Rising newcomers striving for insider identities pay special attention to socialization and norm localization. With the intention to demonstrate their positive attitude toward universal norms and principles, negotiated RTAs exemplified by Tablighi Jamaat (TJ) and many other Muslim groups can either develop subsidiary norms to bridge the discrepancy between universal requirements and local realities or establish subsidiary local institutions that endeavor to “integrate followers into powerful, well-established, cross-border networks” monopolized by the extended insiders (

Levitt 2004;

Acharya 2011). They also serve as key channels to deliver and consolidate the bottom-up influence of local entities to the central government, which faces pressures from both the extended and negotiated RTAs and must take faith-based opinions into consideration.

The principle-agents category may be the most familiar group under the church-state binary that dominates modern international relations. Corresponding to state-linked transnational religious actors in

Haynes’ (

2013) analysis, religious actors in this category have no intention to monopolize legitimacy and authority by excluding their secular counterparts. Instead, they acknowledge material and normative resources and expertise possessed by states, which are the dominant and experienced participants and vehicles in international affairs. In other words, state-linked RTAs choose the state government as their agents to advance the religious influence for the global community. There are two major approaches applied by religious actors. On the one hand, they can form interest groups, advocacy organizations, and electoral constituencies to advance religious interests and preferences in election politics. The religious identities of the congressional caucus, the cabinet of the presidents, and the supreme court justices can also leave religious footprints in the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, three channels of religious influence into the foreign policy. On the other hand, the decentralized, bottom-up structure of religious organizations and institutions can also constitute the civil religion, or “the integration of religion with public life” (

Amstutz 2013). This theology of national political faith further advances the politicization of religion and the religionization of policy making, resulting in the deep intertwine of secular and religious realms of identity, preferences, and interests reflected in domestic and international politics.

4. Evangelicals and US Foreign Policy under the Bush Administration (2001–2009)

To examine the applicability and rigor of the typology above, this section applies the three-dimensional religious soft power mechanism in the post-9/11 George W. Bush administration, which channeled substantial influence of the conservative evangelicals that emphasized dissemination of religious freedom and protection of human rights, thereby contributing to the initiation of US Global War on Terror and the passage of a series of congressional bills on international humanitarian aids and interventions. It begins with a brief review of the religiosity and composition of evangelical groups in the US. Understanding their identities, stakes around which they compete for, and their preferences, it moves on to analyze the performative, discursive, and relational soft power obtained by evangelical communities and actors, which engaged in various operations to advance military actions against radical Islam and global human rights campaign, two pillars of the US foreign policy formulated under the Bush administration, whose legacy continued to shape the outlook of the US’ participation in international affairs for another two decades.

4.1. The Evangelicals in the US: Who Are They and What Do They Want?

Often believed as the single largest religious group in the US, American Evangelical emerged in the eighteenth century as a branch of the Protestants. Its contemporary configuration dated back to the early 1940s, when New Evangelicalism returned to orthodox Protestantism in the face of the fundamentalist movement’s overt disengagement and pietism (

Amstutz 2013;

McMahon 2006). While scholars and pollsters have discerned denominational membership, self-identification, and religious beliefs as three ways to distinguish the evangelicals, the identity of this distinctive group remains flexible and slippery and is consistently mixed up with political conservatives and the Religious Rights (RR). Nevertheless, the evangelicals share a common belief in four core principles. First, the absolute priority and authority of the Scripture result in the textualist reading of the Bible, which lays down fundamental ethics, morality, and the way of life. Second, recognizing the sacrifice of Jesus Christ functions as a way for individuals to personally connect to and reconciliate with God. Third, the salvation of God enables believers to redeem their sins and convert to be born-again Christians. Finally, individuals shoulder the responsibility to proactively disseminate the good news (

euangelion in Greek) or gospel to the entire world (

McGrath 2015;

Bebbington 1989;

Amstutz 2013).

The four pillars of the evangelical belief system and worldview—textualist biblicism, “crucicentrism” (

Bebbington 1989), proselytization, and individual–God connection—thus bring forward two fundamental doctrines that define their material and normative stakes and guide their actions. On the one hand, the evangelicals pledge allegiance to the preservation of their spiritual citizenships. Fully aware of their ontological existence in both earthy nation states, “city of man”, and the spiritual Christian kingdom, “city of God”, evangelicals remain unsatisfied with “sin and human greed” embedded in secular governances, which often attribute social dilemmas to structural forces instead of individual responsibility and performance (

Amstutz 2013). The explicit contradiction to the “accountable individualism” principle that underlies individual–God commitment, therefore, calls for the restraint on state governance. Small governments unable or unwilling to ensure the wellbeing of the believers should transfer authority and rights to their spiritual counterpart, which instead advances the rule of “soulcraft as statecraft” in social engagements (

Shah 2009). On the other hand, since individuals remain key agents of God to actualize salvation and redemption across time and space, the evangelicals following the pietist tradition attempt to advance the universal defense and salvation of human dignity and personal religion by upholding moral traditionalism. Without the ambition to advance the global “moral transformation” (

Mouw 2011), strict and textualist biblical interpretations nevertheless result in the monolithic and fundamentalist moral matrix hinging on human rights, liberty, and justice. The moral superiority and religious exceptionalism thus demarcate the boundary between us and them. Any diversion from the moral orthodoxy is considered as pariahs so detrimental to the existence of evangelicalism that must be targeted and salvaged, even through the use of violence.

As demonstrated above, the religious identity of the evangelicals has left this group with two constant ambitions: to search for adversaries and enemies advanced by the narrative of securitization and to monopolize the making and execution of normative principles endeavored by the expression of moral supremacy. Needless to say, at the end of the Cold War that presented both a series of ethnoreligious humanitarian crises and the unipolar moment in which the US enjoyed unprecedented autonomy, domination, and discourse power, the outbreak of terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001, prepared the evangelicals with the felicitous moment to manufacture alternative realities to set the faith-based agendas, infiltrate three branches of US governments, and proselytize religious principles to rally the audience around the flag through various performances.

4.2. “No God in Common”: Evangelical Discursive Soft Power

Before the airplanes crashed into the World Trade Center and Pentagon, the evangelicals preoccupied with their triumph over the secular evil, the Soviet Union, had just embarked on another search for adversaries. While long aware of discrepancies between their religiosity and Islam, they did not formulate official, full-scale, and explicit anti-Islamic polemics and discourses until 9/11. These sudden, unprecedented, and existential threats designed by an overlooked religious other provided members of the evangelical community with a precise moment to occupy the moral high ground and declare the antagonism with this novel religious evil. The first step was to reexamine cleavages and incongruences between these two religiosities to establish the knowledge foundation of the apologetic narrative. Evangelicals often start with a literal reading and comparison of the Bible and the Qur’an. As exemplified in

Geisler and Saleeb’s (

1993)

Answering Islam, the textbook of evangelical apologetic literature, Islam demonstrates a polemic toward the priority of the Scripture, the resurrection and crucifixion of Jesus, and Christian teachings. Whereas these two religiosities contain different interpretations of overlapping components, the evangelicals find no “redemptive analogy” to establish the common ground between these two religiosities (

Richardson 2003;

Cimino 2005). Further alarming the evangelicals are the antagonism and hostility exhibited by excerpts of the Qur’an toward Christianity. For instance, Surah 5 and 9 of the Qur’an record the waring of Allah toward the Muslims to “take not the Jews and Christians for friends … slay the idolaters [infidels] wherever ye find them. … Fight against those who … believe not in Allah nor the Last Day” (

Hunt 2003). The explicit militancy and constant prescription of fighting enable the apologetics to conclude that Islam is characterized by the innate and habitual embracement of violence. To further elevate the convincingness and trustworthiness of their framings, the evangelicals sometimes turn to the former Muslims, who experienced conversions and are familiar with principles of both religiosities. Testimonies of this group, as exemplified by Unveiling Muslims, constitute a significant component in modeling Islam into a violent other, which not only discriminates “followers of Moses and Christ as children of Satan, not separated brethren” but also embraces jihads as an “essential and indispensable tenet” (

Caner and Caner 2002;

Cimino 2005).

Irreconcilable differences between peace-loving selfhood and cruel unorthodox prepare the evangelicals to engage in the secondary narrative: constructing the evil perpetrators. On the one hand, the evangelicals perceived Islamic extremists participating in the planning and execution of 9/11 as the “space of objects”, rendering Islam militancy and jihadism well-acknowledged and meaningful to the general audience (

Epstein 2008). The exceptionalism and lone-wolf characters of these terrorists were further reduced in the public speeches of the evangelical leaders, who repeatedly emphasized that “terrorists were not some fringe groups that changed the Koran to suit political ends. They knew the Koran quite well and followed the teachings of jihad to the letter”, rendering terrorists into symbols to both blur the line between “good Muslim” and “bad Muslims” and signify the violent nature of the Muslim community as a whole (

Caner and Caner 2002). On the other hand, after constructing and reinforcing the collective memories and common sense of Islam as a synonym for terrorism, the evangelicals further placed special emphasis on their identity as victims representing all oppressed populations around the globe. Islam as a sign of end-times recorded in the Bible symbolized the catastrophic moment that left the evangelicals with no choices but spiritual warfare as the only appropriate and available option. The special subject position as delegate and agent transferred the alienation of Islam to the criminalization of this “evil and wicked religion … with Muhammad [as] a terrorist” (

Baumgartner et al. 2008), thereby justifying the evangelical proposal of salvation and restoration of justice through probable military crusades to counter abuse of power by the adversary.

Further legitimizing its purported self-defense narratives, the evangelicals continued to escalate the instant victim–perpetrator relation into a manufactured, secularized, and systematic clash of civilization, hinging on the barbaric narrative embedded in orientalism. To rally people around the flag, they first turned to the ontological and existential threat to the “city of man”. The national security discourse was exemplified by the address of the Society of Americans for National Existence (SANE), an extremely conservative group arguing that “adherence to Islam as a Muslim is prima facie evidence of an act in support of the overthrow of the US. Government through the abrogation, destruction, or violation of the US Constitution and the imposition of Sharia on the American People” (

Haddad and Harb 2014). Similar concerns about religious freedom and human dignity were expressed by President Bush’s 2001 statement: “They hate our freedoms: our freedom of religion, our freedom of speech, our freedom to vote and assemble and disagree with each other … These terrorists kill not merely to end lives, but to disrupt and end a way of life” (

Bush 2001a). Islamophobia and outrage expressed in these narratives short-circuited the rational judgment of the general public, which believed in the demonized image of the barbaric other and displayed no empathy and effort to challenge the constructed reality. Additionally, as the evangelicals interpret 9/11 as an Islamic attack on the West as a whole, they disseminated anxiety and fear across national frontiers. To counter the “axis of evil”, a term coined by the Bush’s evangelical speechwriter Michael Gerson, the US and its allies set the agenda to defend and promote “a global spread of what the president sees as God-given rights”, especially religious freedom, democracy, and human rights, which constituted the new language of politics (

LaFranchi 2006).

Needless to say, the evangelical discourse of “no god in common” has altered the public perception, sentiment, and reaction to Islam as a religious other. Pew center discovered that 62% of evangelicals and 44% of non-evangelicals in the US remained vigilant to their drastic differences with Islam in 2001. The number of people unaware of the religious antagonism decreased from 31% to 22% from 2001 to 2003, when more than 70% of evangelicals perceived Islam as “a religion of violence” in 2003 (

Pew Research Center 2001;

Ethics and Public Policy Center/Beliefnet 2003;

Cimino 2005). The discursive soft power of the evangelicals in 2001 continues to leave footprints in the US public. Two decades after the tragedy of 9/11, 50% of Americans still perceive Islam as the main source of violence and terrorism, which is twice the number in 2002 (25%) (

Pew Research Center 2021). The anti-Islam thrust in the public memories laid down the foundation for the evangelicals to expand their webs into branches of government, thereby exercising their relational soft power.

4.3. Politicked Crusade in Political Branches: Evangelical Relational Soft Power

Albeit the First Amendment of the US Constitution explicitly demands the separation of church and state, the evangelicals are never strangers to the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The current configuration of evangelical penetrations dated back to the passage of the 1998 International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA), which established the Office of International Religious Freedom under the State Department, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) within the Congress, and a special advisor of international religious freedom (IRF) to the National Security Council (NSC). The evangelicals thus occupy key positions within these branches and possess substantial institutional resources and privilege to advance their agendas, concerns, and interests in the policy-making procedure, “as evident as anywhere in the words and deeds of the current Bush Administration” (

Wessner 2003).

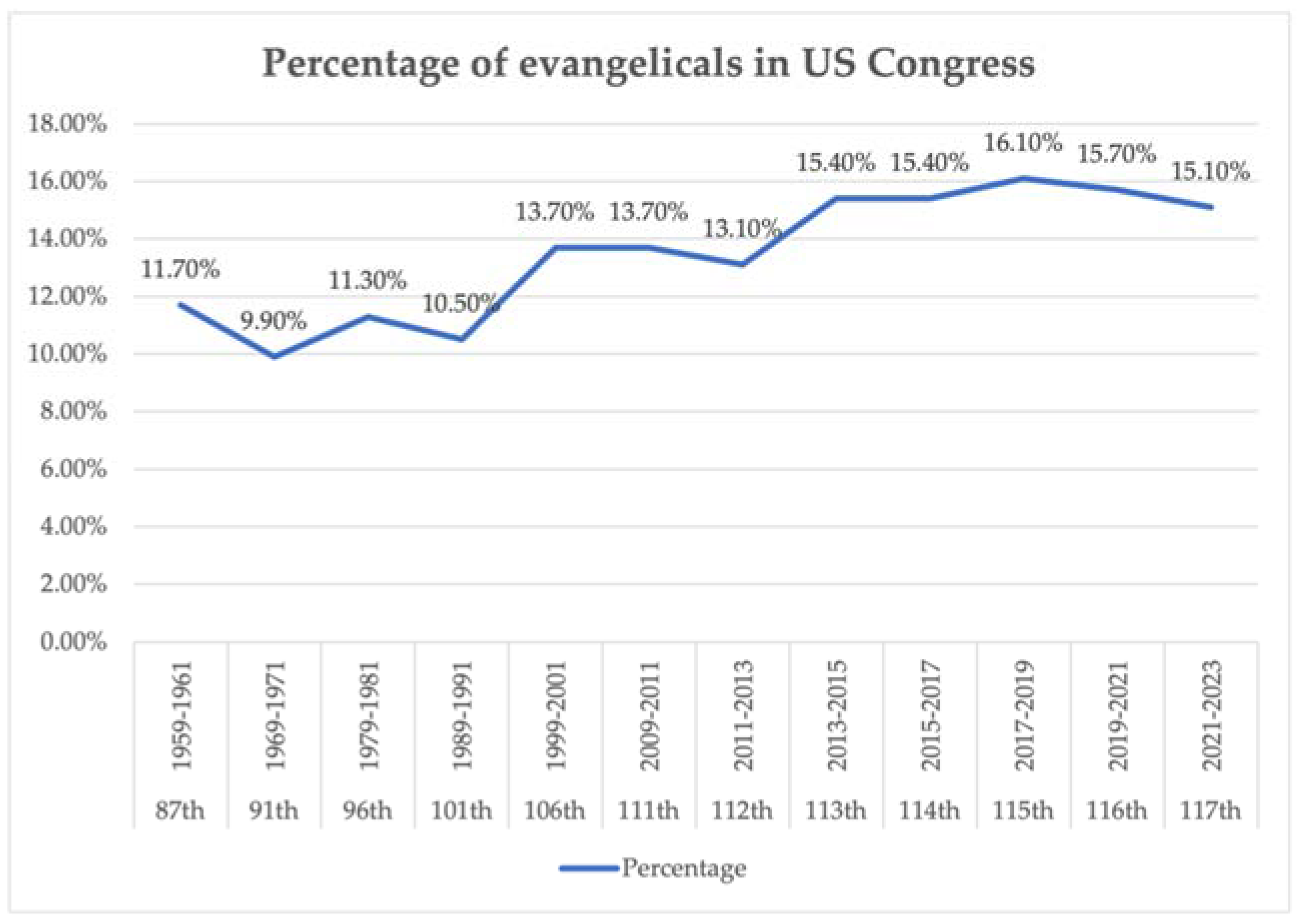

Unlike the US Supreme Court that had since hosted only one evangelical supreme justice, the legislative branch experienced the persistent evangelical influence on the constituency. As demonstrated by

Table 2 and

Figure 1, the percentage of evangelicals in the congress increased 3.4 points from 1961 to 2021, and evangelicals experiencing a drastic increase constituted 13% of congressional membership during Bush administrations (

Pew Research Center 2021). Moreover, the year 2001 witnessed an explicit alignment between partisanship and religious identity, with 61% of White evangelicals identifying with the republicans. Coalitions between the general public and legislators inside consequently contributed to the formation of a determined constituency and electoral group, which comprised various interest groups and lobbies ranging from the Family Research Council to the Christian Coalition. In response to the reorientation of evangelicals’ identity and interests after 9/11, “conservative Christian churches and organizations have broadened their political activism from a near-exclusive domestic focus to an emphasis on foreign issues” (

LaFranchi 2006). When 78% of White evangelicals casted their votes to Bush in his re-election and accounted for 23% of the total electorate (

Pew Research Center 2004;

Cady 2008), the head of state under substantial pressure had no means to circumvent his campaign promises, which emphasized the necessity and legitimacy of the Global War on Terror, a war parallel to the Cold War that excepted the similar triumph of the US in face of the evil Islam. Ensuring that the state would not hunker down and remain reluctant to put the boots down in the Middle East, evangelical groups exploited the textualist reading of the Bible, emphasizing that the Land of Israel was promised to Jewish people by God. As the Christian Zionism fostered an evangelical-Jewish coalition in the elections, it prepared the evangelicals to “be the most effective constituency influencing a foreign policy since the end of the Cold War” (

Brownfield 2002;

Salleh and Zakariya 2012).

In addition to the bottom-up pressure mechanism, the evangelicals identified four loci of direct influence within the executive branch: the president, Ambassadors at Large for IRF, special advisors in the NSC, and IRF-related special envoys and representatives (

United States Commission on International Religious Freedom 2021). Although the latter two were not fully established in the bureaucracy until the 2016 Frank Wolf Act signed by President Obama, the former two indeed provided sufficient institutional space and advantages for religious actors. Both ambassadors at large under the Bush administration were evangelicals with previous leadership in churches and organizations. The very first ambassador Robert Seiple was the president of World Vision International with priorities in evangelical international humanitarianism and developments, and the second ambassador John Hanford served as the pastoral minister of the West Hopewell Presbyterian Church for fourteen years (

Chandler 1986;

Bettiza 2019). Their wide connections and human resources thus prepared a channel for “evangelical Christian leaders to arrange sessions with senior White House aides” (

Page 2005), thus injecting evangelical values and preferences in the annual report analysis and the identification of “countries of concerns” conducted by the state department. Further expanding evangelical spheres of influence were the identity politics and evangelical president style upheld by President Bush, who attributed his successful election and re-election largely to the evangelical constituencies. Perhaps the only President after Carter to repeatedly express his commitment to evangelicalism in public scenarios, Bush was never shy about showing off the close relationship between religion and politics, which was also a religious vocation in his eyes (

Berggren and Rae 2006). “There is only one reason that I am in the Oval Office and not in a bar. I found faith. I found God. I am here because of the power of prayer” (

Frum 2003). Staff familiar with the “predominant creed” of the White House recalled Bush organizing various bible study groups inside the executive branch, and “opening every cabinet meeting with prayer and insisted on a high moral tone” (

Frum 2003). The intrusion of religion into politics resulted in his intimate relations with both domestic and international religious leaders. One of the most surprising examples in his religious connections was British Prime Minister Tony Blair, the “first Prime Minister since Gladstone to read the Bible habitually” (

Rentoul 2001). Bush had explicitly admitted the relational influence of his evangelical identities on the formation of political alliances: “Tony is a man of strong faith. You know, the key to my relationship with Tony is he tells the truth, and he tells you what he thinks and when he says he’s going to do something, he’s going to do it. I trust him” (

Bush 2003). As the US president, Bush found himself positioning at the intersection of the bottom-up demand for “answer[ing] the attacks and rid the world of evil” and the transnational call for “a crusade after all” for human dignity (

Bush 2001b). It was therefore not surprising to find the strong coalition between the US and its allies in the 2001 War in Afghanistan and 2003 Iraq War along with strong executive momentums behind the passage of a series of presidential acts to address human trafficking (2000), ethno-religious conflicts in Sudan (2002), and human rights atrocities in North Korea (2004), all of which witnessed the tri-sector collaborations between the evangelical churches, President Bush, and US allies with evangelical constituencies.

4.4. The Multi-Theater Repertoire: Evangelical Performative Soft Power

A multi-staged theater for the evangelicals to control the public interpretation of and response to crisis formulated when terrorists challenged the US way of life and freedom. The frontage stage performance took place during the evening of September 11 when President Bush delivered a national address loaded with religious elements through the television. The choice of television as the performance channel was a wise move to strengthen the actor–audience connection. The visual imaginaries of plane debris and ordinary heroes saving and helping others displayed a clear contrast between evil and good to instigate grief, fear, outrage, and demand for justice among the general public. A shared identity, “we the people” as American, began to emerge when the audience “see themselves in the collective representations that are the materials of public culture … [thereby] acquir[ing] self-awareness and historical agency” (

Hariman and Lucaites 2003;

Murphy 2003). After viewers familiarized themselves with the general plot, President Bush as the protagonist began to add flesh to the bone with his epideictic speech. The opening line—”our fellow citizens, our way of life, our very freedom came under attack in a series of deliberate and deadly terrorist acts”, with the “deliberate and deadly” echoing with the depiction of the Japanese attack of Pearl Harbor in the famous “Days of Infamy” speech by President Roosevelt—signified a major and sudden disruption of repetitive practice that defined the ontological existence and uniqueness of Americans. The introduction of biblical language, Psalm 23, intended to provide a psychological and spiritual comfort to the traumatized people, whose peace, dignity, freedom, and justice had been disfranchised by “evil, the very worst of human nature” (

Bush 2001c). The issue at hand, as interpreted by Bush also in his prayer and remembrance service at the national cathedral on September 14, was not a sporadic misfortune but a premeditated attack, “an adversity that introduces us to ourselves … as the God’s sign” (

Bush 2001b). Consequently, as the Bible often told, the US as a chosen nation with chosen people were obliged to stand up against the absolute evil and defend the biblical moral and ethics across the globe, thereby establishing religious legitimacy for the upcoming wars against the Taliban and Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan and Iraq. Also worth noticing was the evangelical communication style and emotions of the main actor that spiced up this scene. Famous for his “calmness, certainty … and emotional intelligence” derived from his firm belief in God’s will (

Berggren and Rae 2006), Bush appeared frowning with concerns on the scene. Despite his sincere sadness, there was no voice trembling or tearing up but only strong equanimous deliberations with confident hand gestures, assuring the audience that the imminent crisis ought to be addressed by a reliable and decisive leader, who determinedly claimed: “My faith frees me. Frees me to put the problem of the moment in proper perspective. Frees me to make decisions that others might not like. Frees me to do the right thing, even though it may not poll well” (

Bush 1999). As later recalled by the observer of the decision making regarding the Iraq War, “Bush’s faith offers no speed bumps on the road to Baghdad; it does not give him pause or force him to reflect … but [remains] a source of comfort and strength” (

Klein 2003).

It was evangelical leaders backstage that worked hard to sustain influences of visual imaginary, epideictic rhetoric, and evangelical policy-making style applied at the frontstage. Presidents of religious organizations and high priests from prestigious churches enjoyed considerable public image and media outreach and can reinforce the good–evil narrative and interpretation through their authority and legitimacy. Whereas television evangelist Pat Robertson publicly labeled Islam as “the demonic … and satanic power … worse than Nazis [that] motivate crazed fanatics”, Franklin Graham, the son of the respectable religious leader Billy Graham, accused “Islam as an evil and wicked religion” (

Puskar 2006;

Baumgartner et al. 2008;

Robertson 2002;

Mizner 2011). Performance of demonization was also carried on by the leader of the Southern Baptist Church Jerry Falwell, who expressively announced that “I think Muhammad was a terrorist” (

Baumgartner et al. 2008). In addition to the top-down announcement, rank-and-file religious leaders also strived to embed this anti-Islam thrust into the everyday practice of masses, seminars, and bible studies. Local churches functioned as captains to both localize and politicalize national religious messages. Integrating regional realities and drawing a line between strict Bible reading and conservative policies advanced by Republicans, evangelical leaders not only produced the “sacred expression of” policy agendas of evangelical politicians but also cast a spiritual significance to the performance of voting, which became a core element of the civil religion (

Bean 2014). The religionization of politics was exemplified in the interview with a deacon of Northtown Baptist Church, who testified that “if you listen to the message of the sermons, I believe they are right on with the conservative aspect of the Bible … As far as how it relates politically, it is very important to me to vote for a conservative-thinking candidate” (

Bean 2014). Backstage performances both in the hall of power and in daily life resulted in the effective audience socialization that rallied congregations around the flag with ease through Christian nationalism. The bottom-up evangelical momentum to shape foreign policy was famously displayed in 2004. Unsatisfied with Bush’s soft response to Palestine, Falwell and Robertson bombarded the White House with over 500,000 emails, which soon exhibited a more hawkish attitude to defend “Israel’s unilateral disengagement plan in Gaza” (

Nabers and Patman 2008).

5. Conclusions

How does religion interact with international relations? This essay approaches this question by re-examining the underdeveloped concept of religious soft power. Through an interdisciplinary attempt to integrate IR with political sociology, it challenges the monolithic view of power and proposes a three-dimensional religious soft power model, hinging on its discursive, performative, and relational faces. The applicability and theoretical rigor of this model are tested in the process tracing of the evangelicals’ “no god in common” discourse, politicked crusade in both legislative and executive branches, and the multi-staged performance of the anti-Islam repertoire. All these efforts in turn rendered into discursive, relational, and performative influence on the Bush administration, which structured its foreign policy around two evangelical faith-based pillars: international humanitarian assistance and the Global War on Terror. Through enumerating mechanisms, strategies, and tactics applied by the evangelicals to the Bush administration, this article attempts to provide an operational account of the exercise of religious soft power, whose application procedure is often hard to trace due to its subtle nature. Without overthrowing the current realism–liberalism–constructivism paradigm, it demonstrates that religion, a distinctive factor often marginalized or acquiescent with reluctance by students of international relations, indeed obtains chances and conceptual rigor to fight its way back in this discipline, especially in the post-secular world that animates re-contemplation of the Westphalian–Enlightenment assumption of international affairs.

Advancing the multi-dimensional understanding of religious soft power, this essay is fully aware of several limitations that may undermine the explanatory and predictive power of this model. First, despite scholars’ ceaseless effort to clarify the scope and context of this term, religious soft power still suffers from conceptual ambiguity, given the slippery nature of its key components—religion and soft power. Until scholars can accurately demarcate hard power from soft power, whose nature is undergoing significant changes under globalization, technological innovation, and epistemic revolution, religious soft power remains a debatable concept subject to ceaseless criticisms. Second, the small-N nature of the research based on the qualitative method without the support of significant quantitative data resulted in the limited external validity of the three-dimensional religious soft power model. Third, whereas this essay positions religion under the constructivist paradigm hinging on identity, values, and norms, the empirical analysis demonstrates that religious actors value both material interests and normative principles, with the former aligning more with the realist and rational institutionalist arguments. In fact, the US evangelicals were “neither as self-serving as some realists presume nor as aloof to international social dynamics as rational institutionalist and liberal scholars commonly allow” (

Mantilla 2017). Theoretical monism and “methodological fundamentalism” bring forward the problematic gladiatorial logic, leaving no space for paradigmatic innovations (

Fearson and Wendt 2002;

Checkel 2012).

Whereas this essay positions religion around power, there exit various key concepts in IR that can become anchorages for religion analysis, including but not limited to norm entrepreneurship and antipreneurship, states’ compliance with faith-based international human rights law and humanitarian law, religion and state building, spiritual warfare, and secular–religious competition for international order making and global governance. As we enter the third decade of the twenty-first century under a multipolar, bipolar (US-China), and even a nonpolar system, religion remains central to the functioning and dysfunction of the liberal international order, which has long functioned as both context and source of IR theoretical paradigms. Whether current IR theories and concepts will sustain to host religion remains a key question for future researchers.