From Disruption to Dialog: Days of Judaism on Polish Twitter

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. The Evolution of the Church’s Communication with the Faithful through the Media

1.3. The Nature of Interreligious Dialogue

- Dialogue of everyday life—Christians share their joys, sorrows, problems, and worries with people of other religions in the spirit of friendship and openness;

- Dialogue of common endeavor—occurs when Christians, based on their religious needs, cooperate with the followers of other religions on social, economic, and political grounds to protect human rights;

- Dialogue of exchange of religious experiences—the faithful share the spiritual wealth and their own experience of God drawing on personal religious traditions;

- Theological dialogue—the faithful deepen their understanding of their own and other religions, appreciating spiritual and religious values in the spirit of humility and mutual understanding (Gądecki 2002, pp. 18–21).

1.4. Days of Judaism: History and Principles

- Explain and disseminate the nature of the Day of Judaism;

- Bring closer Church’s teachings on Jews and their religion after the Second Vatican Council;

- Make prayer an integral part of the Day of Judaism;

- Promote post-conciliar explanations of Scripture, which may have been interpreted in an anti-Judaist and anti-Semitic manner in the past;

- Explain the tragedy of the extermination of Jews to the faithful;

- Show anti-Semitism as a sin (John Paul II);

- Invite representatives of other Churches and Christian communities to common prayer on that day;

- Invite Jews to participate in Day of Judaism celebrations (Committee for Dialogue with Judaism at the 2008 Polish Episcopal Conference 2000).

2. Materials and Methods

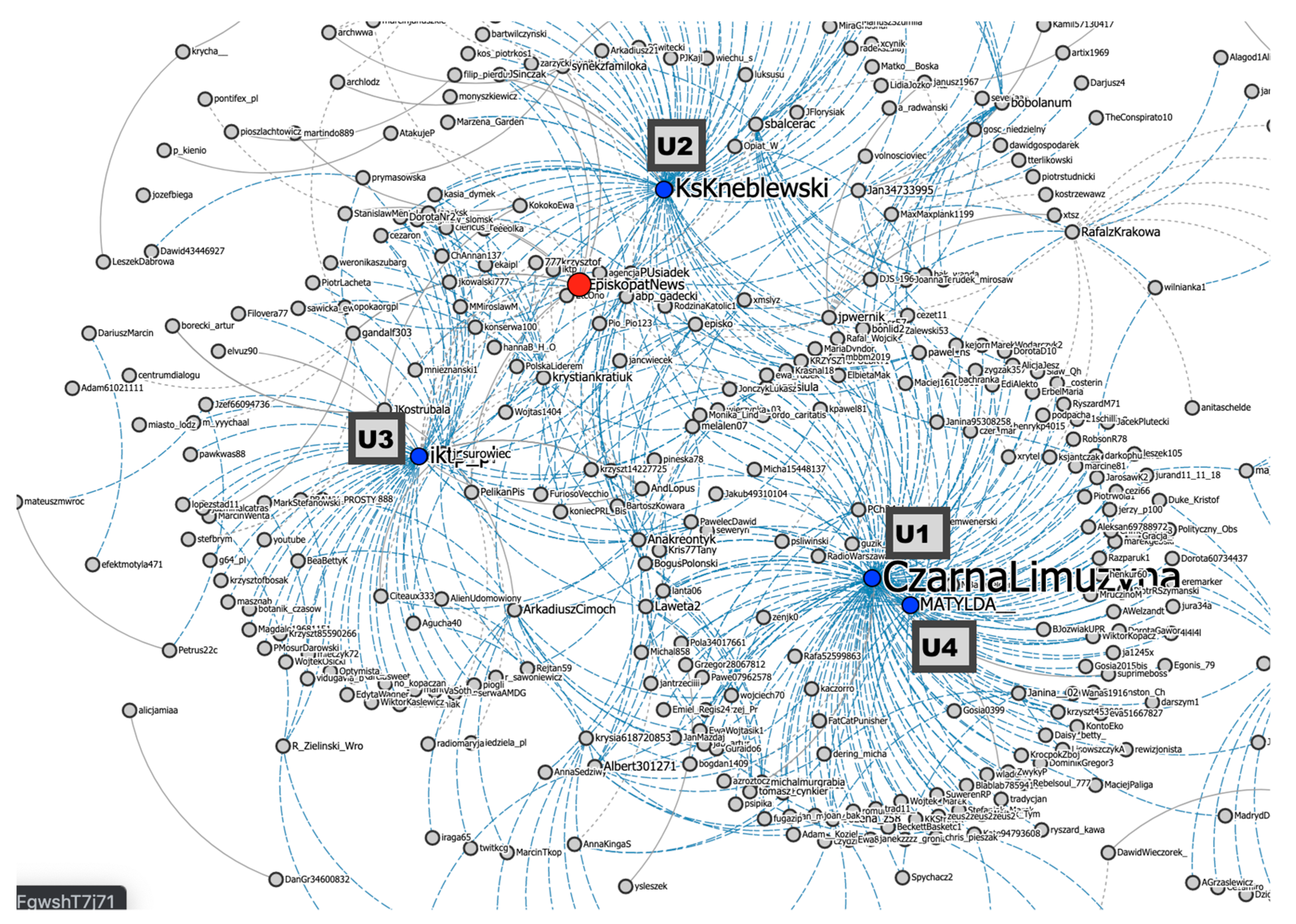

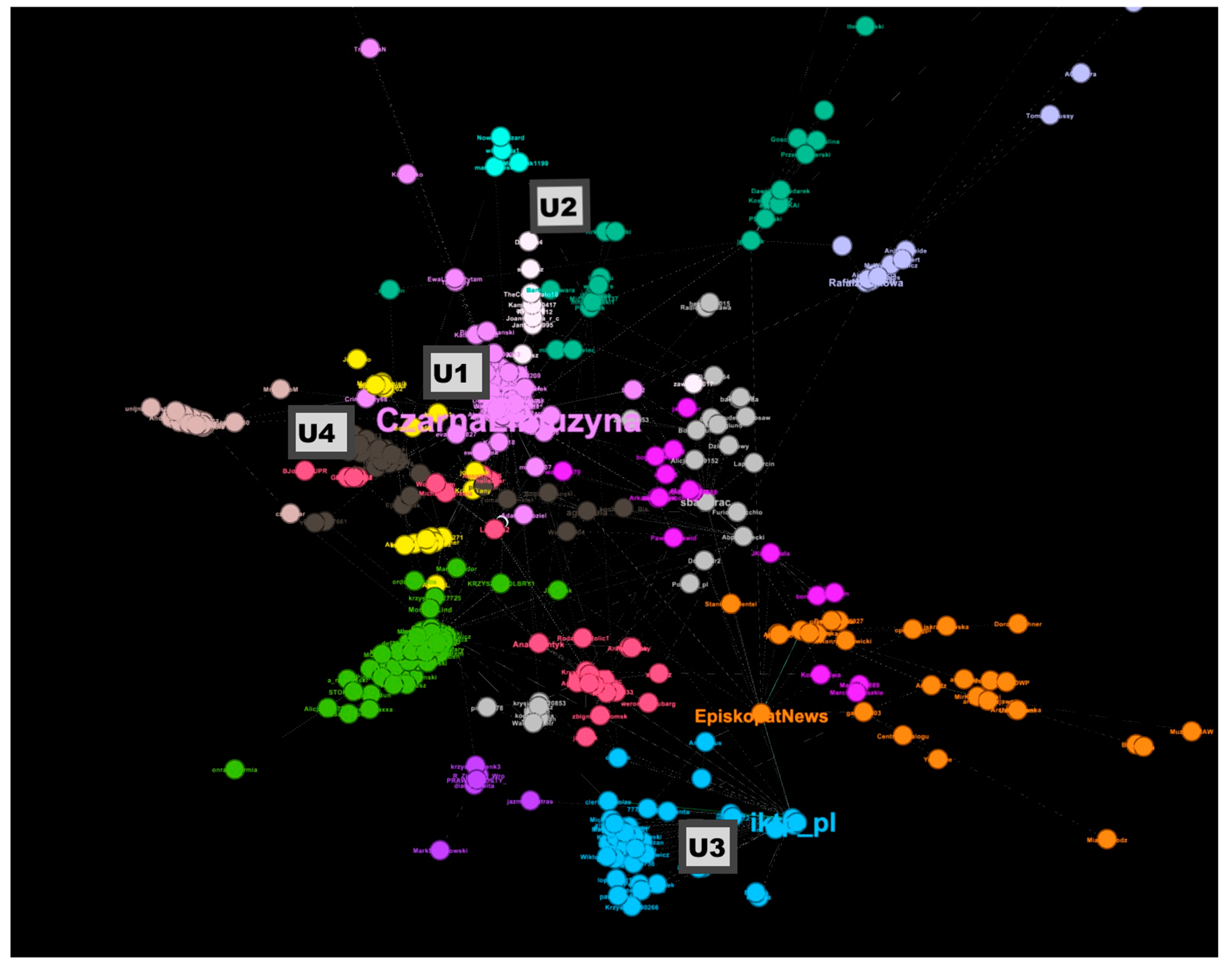

2.1. Visualizing Networks and User Rankings

@EpiskopatNews @CentrumDialogu @MiastoLodz @YouTube Zastanawiam się kiedy u przedstawicieli Judaizmu obchodzony jest dzień chrześcijan?[ENG: @EpiskopatNews @CentrumDialogu @MiastoLodz @YouTube I wonder when representatives of Judaism will celebrate the Days of Christianity]

Z uporem godniejszym lepszej sprawy cześć wpływowych hierarchów w Kościele Katolickim lansuje tzw. dzień judaizmu. Ta nierozumna praktyka trwa już 23 lata... (https://twitter.com/CzarnaLimuzyna/status/1215983702787928064, accessed on 30 January 2020)[ENG: With the stubbornness worth a better case, part of influential hierarchs in the Catholic Church promote so called day of judaism. This unreasonable practice goes back for 23 years…]

Dni judaizmu, islamu, protestantyzmu. A kiedy „dzień Tradycji” w Kościele? (https://twitter.com/KsKneblewski/status/1218270854821359616, accessed on 30 January 2020)[ENG Days of Judaism, Islam, Protestantism? When to expect “the day of tradition” in Church?]

Dzień Judaizmu, Dzień Islamu ... A gdyby tak sięgać po temat znacznie bardziej egzotyczny dla naszego duchowieństwa i urządzić w Kościele Dzień Tradycji Katolickiej? Biskupi z @EpiskopatNews celebrujący pontyfikalnie w swych katedrach po staremu, prelekcje ... Niemożliwe, co? (https://twitter.com/iktp_pl/status/1217709879755931648, accessed on 30 January 2020)[ENG: Days of Judaism, Days of Islam … And what if we take a subject much more exotic for our clergy and announce a Day of Catholic Tradition in the Church?Bishops from @EpiskopatNews pontifically celebrating in the old ways, lectures … Not possible, is it?]

RZYDZI2 [sic!] IDĄ NA CAŁOŚĆ. Dzień judaizmu: dzień bez Jezusa i Maryi w Kościele Katolickim. Czas zakończyć ten absurd. (https://twitter.com/MATYLDA__/status/1216099928537227265, accessed on 30 January 2020)[ENG: JEWS GO FULL STEAM AHEAD. Day of judaism: day without Jesus and Mary in Catholic Church. Time to end this absurdity]

2.2. Detecting Communities

Dzień Judaizmu przypomina nam o naszych korzeniach, a może jeszcze lepiej powiedzieć o tym, kim naprawdę jesteśmy. Każdy chrześcijanin jest w istocie duchowo Żydem. Jeśli nim nie jest, to nie rozumie ani własnej wiary, ani nie akceptuje Jezusa. Warto o tym—w tym dniu—pamiętać (https://twitter.com/tterlikowski/status/1350773421106364417, accessed on 30 January 2021)[ENG: The Day of Judaism reminds us about our own roots and can help us define who we really are. Every Christian is in fact, in his soul, a Jew. If one does not feel that way, one does not understand neither one’s own faith or Jesus. On such day, it is worth remembering it.]

Więc, powtórzę: przy okazji Dnia judaizmu nie opowiadajmy bzdur. Nie jesteśmy duchowo ani żydami ani tym bardziej w jakimkolwiek innym sensie Żydami. Duchowo jesteśmy uczniami i braćmi Jezusa, którego żydzi odrzucili.Mam też pytanie, czy judaizm obchodzi Dzień katolicyzmu? (https://twitter.com/RobertTekieli/status/1350783351792295939, accessed on 30 January 2020)[ENG: So let me repeat myself: on the occasion of the Day of Judaism let us not talk rubbish. We are neither spiritually nor in any other sense Jewish. Spiritually we are the disciples and brothers of Jesus, whom Jews rejected.I also have a question, does Judaism celebrate a Day of Catholicism?]

3. Results

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | EpiskopatNews is a Twitter account founded in 2015 under the name @EpiskopatNews. The main purpose of this information stream is to promote in the media the teaching of the Polish Bishops’ Conference and to inform about current events in the life of the Church in Poland and in the world. The account is run by the Press Office of the Polish Bishops’ Conference, it is the most authoritative and influential source of information for Catholic and lay media, and is conducted in several languages. |

| 2 | The word “Rzydzi” (for Jews, correct spelling “Żydzi”) is most likely deliberately misspelled here in a derogatory fashion in order to raise the expressiveness of this most toxic of more than 1000 analyzed tweets. |

References

- Barabási, Albert-László, and Réka Albert. 1999. Emergence of Scaling in Random Networks. Science 286: 509–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bartoszewski, Władysław. 2007. Przedmowa. In Czerpiąc z korzenia szlachetnej Oliwki. Dzień Judaizmu w Poznaniu 2004–2007. Edited by Jerzy Stranz. Poznań: Uniwersytet Adama Mickiewicza, pp. 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai-Nahon, Karine. 2008. Toward a theory of network gatekeeping: A framework for exploring information control. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 59: 1493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Murdoch, John. 2013. Why You Should Never Trust a Data Visualisation. Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2013/jul/24/why-you-should-never-trust-a-data-visualisation (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Benz, Wolfgang. 2004. Anti-Semitism Research. In The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies. Edited by Martin Goodman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 943–45. [Google Scholar]

- Berlanga, Immaculada, Francisco García, and Juan Salvadro Victoria. 2013. Ethos, Pathos and Logos in Facebook. User Networking: New «Rhetor» of the 21st Century. Comunicar 21: 127–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brock, André. 2012. From the Blackhand Side: Twitter as a Cultural Conversation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 56: 529–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, Axel. 2005. Gatewatching: Collaborative Online News Production. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, Axel, and Jean Burgess. 2011. The Use of Twitter Hashtags in the Formation of Ad Hoc Publics. In Proceedings of the 6th European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR), Reykjavik, Iceland, August 25–27; Colchester: The European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR), pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, Edward Idris. 2001. Przedmowa. In Jan Paweł II i Dialog Międzyreligijny. Edited by Byron L. Sherwin and Harold Kasimow. Kraków: WAM, pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cheong, Pauline Hope, and Charles Ess. 2002. Religion 2.0? Relational and hybridizing pathways in religion, social media and culture. In Digital Religion, Social Media and Culture: Perspectives, Practices, Futures. Edited by Charles Ess, Pauline Hope Cheong, Peter Fischer-Nielsen and Stefan Gelfgren. New York: International Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Chrostowski, Waldemar. 1999. Dialog w cieniu Auschwitz. Warsaw: Vocatio. [Google Scholar]

- Committee for Dialogue with Judaism at the 2008 Polish Episcopal Conference. 2000. Message from the Chairman of the Committee of the Polish Episcopal Conference for Dialogue with Judaism. Available online: https://www.prchiz.pl/dzien-judaizmu-abc (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Dante Francesco. 1990. Storia della “Civiltà Cattolica” (1850–1891). Il laboratorio del Papa. Roma: Studium, p. 57 i in. [Google Scholar]

- De Vaujany, François-Xavier. 2006. Between eternity and actualization. The difficult co-evolution of fields of Communication in the Vatican. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 18: 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gądecki, Stanisław. 1998. I Dzień Judaizmu. “Kto spotyka Jezusa Chrystusa, spotyka judaizm”. Warsaw: St. Wojciech. [Google Scholar]

- Gądecki, Stanisław. 2002. Kto spotka Jezusa spotyka judaizm. Dialog chrześcijańsko-żydowski w Polsce. Gniezno: Prymasowskie Wydawnictwo Gaudentium. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ibánez, Roberto, Smaranda Muresan, and Nina Wacholder. 2011. Identifying Sarcasm in Twitter: A Closer Look. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Portland, OR, USA, July 19–24; Stroudsburg: Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 581–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdy, Naila, and Ehab H. Gomaa. 2012. Framing the Egyptian Uprising in Arabic Language Newspapers and Social Media. Journal of Communication 62: 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, Bernie. 2016. Online Social Networks: Concepts for Data Collection and Analysis. Hogan. In The Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods. Edited by Nigel G. Fieldng, Raymond M. Lee and Grant Blank. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Helen, and William Allen. 2016. Data Visualisation as an Emerging Tool for Online Research. In The Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods. Edited by Nigel G. Fieldnig, Raymond M. Lee and Grant Blank. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 307–26. [Google Scholar]

- KhosraviNik, Majid. 2017. Social Media Critical Discourse Studies (Sm-Cds). In The Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies. Edited by John Flowerdew and John E. Richardson. London: Routledge, pp. 582–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kouloumpis, Efthymios, Theresa Wilson, and Johanna Moore. 2011. Twitter sentiment analysis: The good, the bad, and the OMG! Paper presented at 5th International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Barcelona, Spain, July 17–21; Menlo Park: The AAAI Press, pp. 538–41. [Google Scholar]

- Laniado, David, and Peter Mika. 2010. Making sense of Twitter. Paper presented at the ISWC ’10: 9th International Semantic Web Conference, Shanghai, China, November 7–11; pp. 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lewek, Antoni. 2003. Podstawy Edukacji Medialnej i Dziennikarstwa (Media Education and Journalism Fundamentals). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Kwan Hui, and Amitava Datta. 2012. Following the Follower: Detecting Communities with Common Interests on Twitter. Paper presented at 23rd ACM conference on Hypertext and Social Media, Milwaukee, WI, USA, June 25–28; pp. 317–18. [Google Scholar]

- Meraz, Sharon. 2017. Hashtag Wars and Networked Framing: The Private/public Networked Protest Repertoires of Occupy on Twitter. In Between the Public and Private in Mobile Communication. Edited by Ana Serrano Tellería. London: Routledge, pp. 303–23. [Google Scholar]

- Meraz, Sharon, and Zizi Papacharissi. 2013. Networked Gatekeeping and Networked Framing on# Egypt. The International Journal of Press/Politics 18: 138–66. [Google Scholar]

- Neugröschel, Marc. 2021. Redemption Online: Antisemitism and Anti-Americanism in Social Media. In Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds. Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat and Lawrence H. Schiffman. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, Donald A. 1999. Affordance, Conventions, and Design. Interactions 6: 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nostra aetate. 1965. Deklaracja o stosunku Kościoła do religii niechrześcijańskich. In Sobór watykański II (1962–1965), Konstytucje, dekrety, deklaracje. Poznań: Pallotinum, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- John Paul II. 1986. 1986-04-13 Jan Paweł II—Przemówienie w Synagodze Większej w Rzymie. Available online: https://cdim.pl/1986-04-13-jan-pawel-ii-przemowienie-w-synagodze-wiekszej-w-rzymie,467 (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- John Paul II. 1995. Encyclical of the Holy Father John Paul II on Ecumenical activity Ut Unum Sint. Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Perline, Richard. 2005. Strong, Weak and Inverse Power Laws. Statistical Science 20: 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petykó, Márton. 2018. The Motives Attributed to Trolls in Metapragmatic Comments on Three Hungarian Left-Wing Political Blogs. Pragmatics 28: 391–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorna-Ignatowicz, Katarzyna. 2002. Kościół w Świecie Mediów. Historia-Dokumenty-Dylematy (The Church in the World of Media. History-Documents-Dilemmas). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Raś, KS. Dariusz. 2021. Papal e-mail. Available online: www.opoka.org.pl/biblioteka/Z/ZW/ecclesia_oceania_email.html (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Sagi, Eyal, and Morteza Dehghani. 2014. Moral Rhetoric in Twitter: A Case Study of the Us Federal Shutdown of 2013. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society 36: 1347–52. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Vivek K., and Ramesh Jain. 2010. Structural Analysis of the Emerging Event-Web. In Proceedings of the 2010 World Wide Web Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, Raleigh, NC, USA, April 26–30; New York: ACM. [Google Scholar]

- Stranz, Jerzy. 2007. Zasadzeni nad płynącą wodą. Wprowadzenie. In Czerpiąc z Korzenia Szlachetnej Oliwki. Dzień Judaizmu w Poznaniu 2004–2007. Edited by Jerzy Stranz. Poznań: Uniwersytet Adama Mickiewicza, pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, Jeffrey C. 2010. Twitter Rhetoric: From Kinetic to Potential, Dissertation. Available online: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=3532&context=etd (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Yardi, Sarita, and Danah Boyd. 2010. Dynamic Debates: An Analysis of Group Polarization over Time on Twitter. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society 30: 316–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pisarski, M.; Gralczyk, A. From Disruption to Dialog: Days of Judaism on Polish Twitter. Religions 2021, 12, 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100828

Pisarski M, Gralczyk A. From Disruption to Dialog: Days of Judaism on Polish Twitter. Religions. 2021; 12(10):828. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100828

Chicago/Turabian StylePisarski, Mariusz, and Aleksandra Gralczyk. 2021. "From Disruption to Dialog: Days of Judaism on Polish Twitter" Religions 12, no. 10: 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100828