Abstract

Diseased Organ and tissue donation and transplantation entails removing organ and tissues from someone (the donor) and transplanting them into another person (the recipient). Transplanting organs and tissues from one person hold the capacity to save or significantly improve the quality of life of multiple recipients. This is a rare opportunity for one to become an organ donor. In 2018, Australia had a population of 24.99 million. A total of 160,909 lives were lost that year; almost half of this death occurred in hospitals. However, a person may only be able to become a donor if their death occurs in a particular way and fulfils a defined set of special criteria—for example, while on the life support machine in an intensive care unit. Because of this, only 1211 people out of the large number of lives lost in 2018 were eligible to be potential organ donors. This is one of reasons we encourage everybody to consider the virtues of organ and tissue donation in any end-of-life discussion. Diseased organ donation occurs only when the clinician is certain that the person has died. The death is diagnosed by neurological criteria or by circulatory criteria which are discussed in detail in the article. This is an unconditional altruistic and non-commercial act. A large number of people are waiting on transplant list in Australia who are suffering from end stage organ failure; some of them will die waiting unless one receives an organ transplantation. Australians are known to be highly generous people. That is why 98% of Australian say ‘Yes’ to become an organ donor when they die. But in reality, only about 64% of families consent for organ donation on an average. There are widespread misconceptions and myths about this subject, mostly due to lack of information and knowledge. I have attempted to explain the steps of diseased organ donation in this article which, hopefully will be able to break some of those misconceptions. I have avoided to discuss living donation which is entirely a different subject. I have only touched on Islamic perspective of organ donation here as multiple Islamic scholars are going to shed lights here. We encourage everybody to ‘Discover’ the facts about organ and tissue donation, to make an informed ‘Decision’ and ‘Discuss’ this with the family. If the family knows the wishes of the loved one, it makes their decision-making process much easier during such a devastating and stressful time.

‘My dad passed away in early 2014. Today, and for all the years to come, we will live with the consequences of him being gone and while the pain is not the raw shock and denial it was one year ago, that feeling of loss will always be there. Yet I will consider myself lucky as I have the comfort of knowing my dad was an organ donor and something of a hero to many, myself included. The fear that you will never hear or see your loved one again can be overwhelming. My dad spent his last night playing cricket on the beach, laughing with his daughters over homemade shortbread ice cream, and watching ‘The Hobbit’ with his son and wife. It was the perfect end to a brilliant life, almost as though he had designed his last night with us himself. But within hours we are faced with the question of whether or not we would donate his organs. Phrased like this it seemed harsh, but for those who need that second chance at life it really comes down to yes or no…

Today we live with the relief that we made this decision. It offers hope against the finality of death and out of our loss came the ability to prevent another family from suffering the heartache that we have.

For those who have received an organ and those who make it possible, I want to say how grateful I am. You hold a very special place in my heart for letting my dad live on’.(Donatelife NSW 2020a, vol. 18, p. 11)

An account written by Charlotte in ‘The Book of Life’, when her father passed away and became an organ donor.

The following is an extract written by Kate, who became an organ recipient at the age of 37:

‘I write this on the 12th anniversary of my kidney transplant. A day of thanks, a day when my thoughts return to my donor and donor’s family and a day when I reflect how my life has changed since I first heard the words ‘you have renal failure’ [kidney failure]. I was 37, fit, well and happily married with two young children when I felt as if I was coming down with the flu. Within days I had renal failure. My immune system had mistaken my kidneys for the virus and shut them down.

With the help of my family, I managed haemodialysis at home for five and half year. During those years, a transplant seemed like the ‘light at the end of the tunnel’.

I expected to be excited when I first received the call that a transplant was available but, as my husband and I travelled to the hospital, I was filled with sadness for my donor’s family. Today I am pleased to say my kidney and I are going well. I have a happy life, and my family and I enjoy the freedom that my transplant offers. I am very grateful to my donor and donor’s family for the opportunity they have given me’.(Donatelife NSW 2020b, vol. 1, p. 33)

These accounts, and many more heartfelt memoirs from real donors and recipients, are written in ‘The Book of Life’ by Donatelife Australia (www.donatelife.gov.au, accessed on 20 May 2020, go to ‘Donation stories’, then open ‘Donatelife Book of Life’).

1. Introduction

Deceased organ and tissue donation involves removing organs and tissues from someone who has died (the donor), and transplanting them into someone who, in many cases, is very ill or dying (the recipient). Transplanting organs or tissues hold the capacity to save or significantly improve the quality of life of the recipient. In this chapter, my primary focus rests upon a discussion of the process of organ and tissue donation and transplantation occurring after death. As such, this chapter will not discuss living organ donation, wherein a living donor donates an organ (such as a kidney, part of a liver or other tissue) to a recipient who needs transplantation, after which the living donor continues to live a normal life.

Organ donation in Islam is a complex subject and is still being debated as a controversial issue. Being a medical expert, and with large experience of working ‘on field’, I feel that people need to understand each step involved in simple terms. In this way, it would be easier to decide in times of immense distress. People need to know rulings from both schools about permissibility before making an informed choice, which are discussed in other parts of the publication.

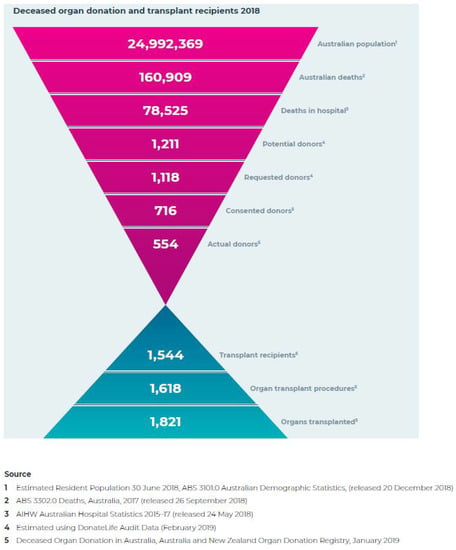

Organ and tissue donation after death is a rare opportunity to save or improve the quality of many lives. In 2018, Australia had a population of 24.99 million. A total of 160, 909 lives were lost that year; almost half of these deaths occurred in hospitals. However, a person may only be eligible to become a donor if their death occurs in a particular way and fulfils a defined set of special criteria—for example, while on the life support machine in an intensive care unit. Because of this, only 1211 people out of the almost 161,000 lives lost in 2018 were eligible to be potential organ donors (Donatelife NSW 2018). The image is just an example from 2018, which is similar each year. We recognise that countless more people could potentially be tissue donors and encourage everybody to consider the virtues of organ and tissue donation in any end-of-life discussion (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Funnel diagram obtained from Donatelife, NSW website www.donatelife.gov.au (accessed on 15 June 2020).

Islam is a major religion in the world today, followed by countless people across all cultures and regions. About 24% of the global population (that is, approximately 1.9 billion people) are Muslims (World Population Review 2021). In Australia, an estimated 2.6% of the national population (more than 600,000 people) are Muslims, with the largest percentage of Muslims residing in Sydney (Census Australia 2016, Australian Bureau of Statistics). In a recent survey conducted on a subset of the Muslim population, results indicated that there is widespread public support for organ and tissue donation in the Muslim community, with many voicing their support in the pursuit of helping others. However, despite many Muslims’ philosophical advocacy for organ donation, results for this survey also indicated the concerning misconceptions that continue to pervade Islamic conceptions about organ and tissue donation (Donatelife NSW 2020c; Multicultural Eid Festival and Fair 2013). Hence, proper education and the dissemination of information are crucial to building an informed foundation for understanding organ and tissue donation and transplantation among the Muslim population.

2. Islam and Altruism—Are Organ and Tissue Donation Allowed in Islam?

For many Muslims, altruism inviolably lies at the core of living a pious life, for the act of saving a life is regarded very highly in the Quran.

Islamic legal and moral codes are derived directly from the primary sources of the Qur’an and Sunnah, as well as the secondary sources of Ijma, Qiyas, ijtihad, Istishab, Maslaha, Istihsan and Urf (Rady and Verhejde 2014). The Holy Qur’an and Sunnah do not offer any clear verdict on the issue of organ and tissue donation and transplantation, arguably because there was no such issue to speak of during those times. However, they do offer general principles to shed light on unknown issues that may emerge with the passage of time. Muslim scholars around the world have discussed the issue over the last few decades, using principles from the aforementioned primary and secondary sources to clarify the status of comparable practices, and reach a verdict on the ambiguity regarding organ and tissue donation using analogy.

Of the evidence cited by scholars in support of organ and tissue donation, the following Qur’anic verses contained in Surah Al-Ma’idah and Surah Al Baqarah are given particular significance:

‘And whosoever bringeth life to one it shall be as though he had brought life to all mankind’.(AL Qur’an 5:32)

‘He (Allah) has only forbidden you dead meat, and blood, and flesh of swine… but if one is forced by necessity, without wilful disobedience, nor transgressing due limits, then he is guiltless…’.(AL Qur’an 2:173)

The principle of Fiqh, based on the above Qur’anic guidelines, states:

‘Necessity makes prohibition lawful’ (Khadija 2016 ‘Umdat al-Najir ‘ala al-Ashbah w’al-Naza’ ir). Therefore, in cases of need and necessity, impure unlawful and otherwise Haram things become permissible. When a person’s life is in danger and he is in dire need for transplantation, he is necessarily cast into such a situation—thus, it can be understood that in such circumstances, the transplantation of organs will be permissible.

The Islamic Fiqh Council, which convened its fourth conference in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia in 1988, determined ‘…It is permissible to transplant an organ from the body of one person to another… it is permissible to transplant an organ from a dead person to a living person whose life or basic essential functions depend on that organ, subject to the condition that permission be given by the deceased before his death, or by his heirs after his death, or by the authorities in charge of the Muslims if the identity of the deceased is unknown or he has no heirs…’ (Resolutions of Islamic Fiqh Council of the Organization of the Islamic Conference 1988).

Organ donation is thus not permissible in Islam if:

- Life depends upon that organ (e.g., the heart), or if any harm has been done to the donor (in the case of living donation);

- The organ is sold or traded;

- There is no consent.

The vast majority of Muslim organizations and leaders agree as above and consequently approve organ and tissue donation as a good deed.

There have been multiple conferences with Islamic scholars on the definition of death, particularly the understanding of brain death. In 1986, the Council of Islamic Jurisprudence held its third meeting in Amman, Jordan, and decided to ‘accept brain death equivalent to legal death according to Islamic religion’ (Resolution of the Council of Islamic Jurisprudence on Resuscitation Apparatus 1986). In fact, all Abrahamic religious traditions (that is, those of Judaism Christianity and Islam) have expressed support for this definition of death, assuming its evidentiary support in science (The Lancet 2011, Editorial).

It is to be noted that a sector of the Islamic scholarly community has expressed their opposition to organ donation and transplantation. Citing from the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), ‘Breaking the bone of a dead person is similar (in sin) to breaking the bone of a living person’ (Yaser 2008). It is a well-established principle of Shariah that all organs of the human body, whether one is a Muslim or non-Muslim, are sacred, and must not be tampered with. This school of scholars is convinced that the sanctity of the cadaveric body is broken by the organ donation surgery.

All views are respected when it comes to organ and tissue donation. That is why the opportunity must be discussed in detail, with all questions answered and informed consent ensured before every step is taken—whatever one’s decision may be.

I will abstain from delving further into the ethical debate surrounding Islam and organ donation and transplantation, as this discussion is well-investigated by countless Islamic scholars who have shed significant light on the subject here. In the remainder of the chapter, I will write on the medical aspects of organ donation and transplantation, explaining each step in simple terms. In doing so, I will also address a few of the common questions and myths that circle around this process.

3. The ‘Death Question’—Understanding What ‘Death’ Really Means

‘Death, as we conceptually understand, is the state when a soul has left the body. Death has immense cultural, spiritual, religious as well as biological importance, with contesting meanings emerging from each respective viewpoint. Biologically, dying is a process, and the determination of death is an event in that process. In biological terms, ‘dying’ describes the process when cellular and organ functions progressively cease. The determination and certification of death signifies that an irrevocable point in the dying process has been reached. We recognise death when we observe absence of life in a body, including immobility, absence of breathing and subsequent cooling of the body and decay’ (ANZICS Statement on Death and Organ and Tissue Donation 2018, p. 13).

There has been much debate in medical communities on how to define death in the last few centuries. William Harvey notably prompted a discussion of death in the 17th Century, describing the circulation of blood and the function of heart as a pump, stating that ‘… The heart is the principle of life… from which heat and life are dispersed to all parts’. (Harvey 1628). Within this concept, death occurs when the heart and circulation has stopped.

The success of mechanical ventilation and intensive care units have irrevocably changed the natural process of death. There have been reports of conditions in the late 19th century, where increased intracranial pressure (high pressure in head/skull) suddenly caused breathing to stop, whereas the heart continued to beat for a period, particularly if the artificial respiration was continued (Cushing 1902). If a patient has been put on a mechanical ventilator (‘life support machine’), a state will arise after a catastrophic brain injury (such as bleeding, or something similar), when artificial ventilation continues to push oxygen into the body. The state of high intracranial pressure could continue to worsen to such a state that blood flow to the brain will altogether stop. The brain, without any blood supply, on top of the initial injury, will die. However, the oxygen pushed by the ventilator into the lungs will keep the heart beating, keeping the blood circulation going and the body warm. The catastrophic loss of all functions of the brain, including the brainstem, is permanent and irreversible. The brain stem is responsible for maintaining basic human functions including consciousness, breathing, and others. If the patient was not on a ventilator, breathing would have altogether stopped, followed by the heart. In a report conducted on 23 patients, Mollaret and Goulon demonstrated that in the absence of any electrical activity in the brain, the body falls into a deep coma, with no breathing, no muscle activity, high urine output and low blood pressure—this phenomenon was called the ‘el coma despasse’ (‘beyond coma’) (Mollaret and Goulon 1959). Since then, a single operational definition of death has been proposed in Montreal, defining ‘death’ as ‘the permanent loss of capacity for consciousness and all brainstem functions, as a consequence of permanent cessation of circulation or catastrophic brain injury’ (Shemie et al. 2014).

Within the Australian context, the Australian Law Reform Commission recommended in 1977 that death be defined as:

- the irreversible cessation of all functions of the brain of the person (brain death) or

- the irreversible cessation of circulation of blood in the person (circulatory death).

All Australian state and territory laws concerning the definition of death are now closely based on this recommendation.

This is a vital subject when discussing organ donation in Islam. Death must be confirmed by medical and Islamic jurisprudence to consider deceased organ donation. As mentioned, the definition of death by medical communities is mostly accepted by Islamic scholars all around the world (Resolution of the Council of Islamic Jurisprudence on Resuscitation Apparatus 1986), though a significant section opposes it.

Islamic scholars in Australia also agree with the above definition. As the Grand Mufti from Australian National Imam Council (ANIC) stated in February 2013, ‘Organ and tissue donation transforms the lives of people in need of a transplant. It is a generous act that each of us has the potential for and any of us one day benefit from. In this way organ and tissue donation respects the sanctity of life and enables people to give the ultimate gift of life to others’. Similar endorsements have been given by most Islamic scholars and leaders in Australia, including Islamic council of Victoria, Arab council of Australia, Turkish Diyanet, Erskine Mosque, and Redfern Islamic Council, to name a few (Donatelife NSW 2020c).

4. Determination of Death

Every state and territory in Australia has stringent criteria when it comes to determining death. These conditions are outlined as follows:

- Circulatory determination of death (‘circulatory Death’, ‘Determination of Death by Circulatory Criteria’)

- This is the ‘death’ that we traditionally know—the person is unresponsive, not breathing, is not moving and has no pulse (the heart has stopped) for at least five minutes;

- A doctor certifies death after examination.

- Neurological determination of death (‘Brain Death’ ‘Determination of Death by Brain Death Criteria’) (ANZICS statement on Death and Organ and Tissue Donation 2018).

‘Death in Islam is the termination of worldly life and the beginning of the afterlife. Death is seen as the separation of soul from the body and its transfer from this world to the afterlife’ (Butrovic 2016). This is easily ‘seen’ in the case of circulatory determination of death. However, ‘Brain Death’ is a little more challenging for general population to understand, sometimes leading to considerable confusion. This is a fact for not just Muslims but the wider community. The confusion arises from the fact that even when a person is declared dead by neurological criteria as described, the person still feels warm, the monitor shows heart activity, and the chest is moving (due to the ventilator). However, as described elsewhere, most of the Islamic scholars around the world endorse that this is equivalent to the death accepted in Islam (Resolution of the Council of Islamic Jurisprudence on Resuscitation Apparatus 1986).

A short summary of its history has been depicted above with some explanation. I will attempt to elaborate furthermore on this here, though it may sound somewhat repetitive by virtue of its complexity.

Neurological determination requires proving ‘irreversible cessation of all functions of the brain’ (Australian Law Reform Commission 1977). ‘For neurological determination of death to be conducted, there must be definite clinical or neuroimaging [imaging of brain] evidence of acute brain pathology consistent with deterioration to permanent loss of all neurological functions. In case of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy [brain pathology due to low blood/oxygen supply, as may occur after a cardiac arrest], clinical history alone may provide sufficient explanation of the acute brain pathology and not require neuroimaging prior to neurological determination of death by clinical examination’ (ANZICS statement on Death and Organ and Tissue Donation 2018).

Acute brain pathology may also occur due to severe brain injury by trauma, catastrophic bleeding in the brain or a large ‘brain stroke’ (ANZICS statement on Death and Organ and Tissue Donation 2018).

- If such a catastrophe occurs, the brain cells become injured. The brain, like any other part of our body, then swells up due to the injury. The brain is situated inside our skull, which is almost like a closed box. Because the skull cannot expand in adults, the pressure inside the skull starts to rise—this is referred to as ‘high intracranial pressure’;

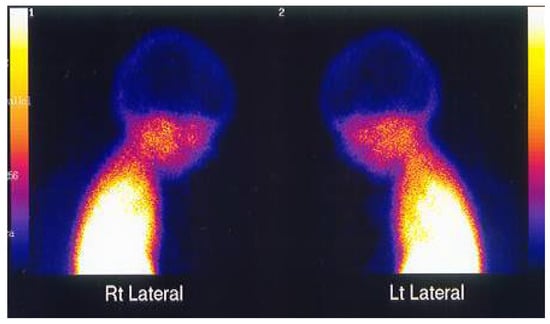

- This further exerts pressure on the brain, causing further brain injury. The doctors, at this stage, are working on the patient with various treatment methods. If these treatments fail, the brain may get so damaged that at some stage, all functions of the brain will be lost. Once a brain cell dies it is permanently lost; the body cannot regenerate brain cells. The high pressure inside the skull will stop all blood flow into the skull; this can be diagnosed by an angiogram (Figure 2) or a special brain scan (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Cerebral Angiogram showing normal blood supply on the left and no blood supply on the right. Photo Source: Australian Donor Awareness Programme and Training (ADAPT).

Figure 2. Cerebral Angiogram showing normal blood supply on the left and no blood supply on the right. Photo Source: Australian Donor Awareness Programme and Training (ADAPT). Figure 3. TC99 scan of the brain of a brain-dead person showing nil evidence of brain activities. Photo Source: Australian Donor Awareness Programme and Training (ADAPT).

Figure 3. TC99 scan of the brain of a brain-dead person showing nil evidence of brain activities. Photo Source: Australian Donor Awareness Programme and Training (ADAPT). - A ‘Formal Brain Death’ testing is performed by two senior clinicians with sufficient experience and expertise, as defined in every state and territory.

- Preconditions: There are specific preconditions that must be met before performing a formal clinical brain death testing. These includes various conditions that can affect the test result. These may include: the amount of sedation medication given to the patient which needs to be metabolised/washed off the body system, if there are severe electrolyte disturbances which may need to be corrected, and low blood pressure that may require further treatment. Sometimes, ensuring preconditions are satisfied may delay the brain death testing.

- Clinical testing cannot be done immediately after a brain injury—there is specific criteria for the observation period to ensure sufficient time has been given, influenced by the above preconditions.

- Two clinicians, as described above, then perform ‘formal brain death testing’ separately—this is done to detect the presence, or absence, of specific brain functions. This includes testing for various brainstem reflexes, such as:

- Response to pain—measured amount of stimulation is given to the head/neck area to see response;

- The eye’s pupillary responses to light—light is shone into each eye to see the pupil’s response;

- The eye’s corneal responses to touch—eye surface is touched with a soft cotton or similar;

- The cough reflex (by stimulating the trachea)—the tube which is already inside the trachea is gently moved to see if the patient coughs;

- The gag reflex (by stimulating the back of the throat)—back of the throat is touched to see if patient gags;

- Response to cold stimulation of the ear drum—a specific test to elicit a response on the eyes.

These may be followed by an ‘Apnoea test’—a test to see if the patient has any ability to breathe without any support from a ventilator (during this test, the ventilator is disconnected, and the patient is closely observed for spontaneous breathing activity). This is a crucial part of the test, as nobody can live without breathing by themselves. Sometimes, patients do not tolerate this step, wherein oxygen levels may descend to dangerously low levels, or blood pressure may become too unstable. If it is within their wishes, these tests can often be conducted in the presence of a family member. The clinical brain death testing is a rigorous process which takes one to two hours and is frequently assisted by a few nursing staff.

- g.

- The clinicians then complete a ‘Brain Death Certification’ form, signed by each member only when they are completely satisfied. The time of death is declared when the second examiner completes the test.

- h.

- Often clinicians can declare death after clinical testing. Sometimes, when clinical testing cannot be performed or clinicians are not satisfied during the process of testing (e.g., if the patient could not complete an Apnoea test), clinicians may request a radiological investigation to confirm the ‘absence of blood flow to the brain’, as mentioned previously—this process involves transporting the patient to the radiology department and undertaking an angiogram or a Technesium brain scan (neuroimaging). These investigations are then reported by appropriately trained radiologists, upon which the clinicians then decide whether to determine brain death.

As the above steps indicate, a rigorous process is followed before a person is declared brain dead, requiring supervision from various legal proceedings and guidelines.

This is important to understand when a loved one attends the person on bedside who has just been declared brain dead. It often proves confusing for family members, as the patient is still warm to touch—their chest is still moving (because of the mechanical ventilator) and heart is still beating, as seen on the monitor (because of the continuous oxygen supply by the ventilator). For this reason, we often spend a long time with family members to explain the complexity behind brain death.

All organs of a brain-dead person may function normally if supported with all the intensive care supports. However, as all functions of the brain are permanently and irreversibly lost, the heart will eventually stop. This person will never wake up.

By following the above criteria, one of the basic principles of Islam is ensured—no harm must be done to the donor. If there are any signs of life present during the above examinations, organ donation must not proceed. The confirmed diagnosis of death also ensures the resolutions of Islamic Fiqh council that organ donation must not harm the donor among other points. (Resolutions of Islamic Fiqh Council of the Organization of the Islamic Conference 1988). As mentioned earlier, neurological determination of death may be a difficult concept for a Muslim. Hence, there has been a lot of community education and a great number of meetings to bring the Muslim leaders up to the level of understanding. Many Imams and Islamic leaders in the community are now able to answer a lot of questions about death in such a devastating situation. One can request an Islamic leader to attend the hospital to help them understand death from an Islamic perspective.

5. Organ and Tissue Donation after Death

Organ and tissue donation can only happen once death has been confirmed by either circulatory or neurological criteria (Truog and Robinson 2003). This is an unconditional, altruistic and non-commercial act.

It is a rare opportunity to become an organ donor, as death must occur in very specific circumstances and specific ways for a person to become an organ donor.

A loved one must be on a life support machine in an intensive care unit or in an emergency department when the discussion of organ donation takes place. In such circumstances, the medical team will first determine death (brain death) or ‘futility of treatment’. Only in these circumstances will doctors then determine whether the patient is medically suitable to become an organ donor. Sometimes, an early decision can be made regarding whether the patient is ‘Not Medically Suitable’; for example, if the patient suffers from metastatic cancer (a cancer that has spread to other parts of the body). Moreover, a person might have made a clear decision, when alive, after proper research, that he/she would not want to be an organ donor after death and have conveyed that message to the family. Organ donation cannot proceed. Note that a Muslim might consider organ donation based on his or her understanding of Islamic teachings and rulings, however, also to note, theologically there is debate on the permissibility and impermissibility of organ donation in Islam (Padela and Auda 2020).

The donation process can occur through either of the following two pathways:

- Donation after Brain Death (i.e., following neurological determination of death) (ANZICS statement on Death and Organ and Tissue Donation 2018)

This is the more common pathway by which organ donation takes place. The discussion starts once the ‘Formal Brain Death Testing’ is complete as explained above. This is a rigorous process with stringent criteria set by ANZICS (Australia and New Zealand Intensive Care Society) and other health authorities. Many scholars from different parts of the world, including those from many Muslim countries, endorse ‘brain death’, however, the concept remains somewhat controversial in Islam.

- The patient is then kept on the ventilator with all support continued, including intravenous fluids, other medications, position changing, and daily routine care of the patient that may even include regular suctioning to clear secretions from lungs.

- The consenting process with the family continues alongside several investigations conducted to ensure the patient’s medical suitability.

- Amongst others, a select number of specific investigations are conducted to find the best match for the patient to minimise the chances of transplant rejection (the body may reject a transplanted organ for various reasons) in the recipient.

The above investigations may take 4–8 h to complete.

- d.

- Once consent is provided by the family, a large team is then engaged for the procedure, including the operating theatre, anaesthetists, numerous surgical teams (including the cardiothoracic surgeon, liver surgeon and abdominal surgeon), organ donation team, appropriate organ allocation team and the transplant team preparing at the transplant hospitals.

- e.

- After about 12–18 h of intensive work by the team, the patient is then transferred to the theatre. It is at this point that the family says goodbye to the loved one.

- f.

- The organ retrieval surgery takes place, maintaining full dignity respect and aseptic precautions, like any other surgery.

- g.

- During this time of preparation, family members are allowed to stay with the loved one. Family may organise to recite the Quran continuously at the bedside. An Imam may attend to bless the soul.

- h.

- Donation after Circulatory Death (Death determined by Circulatory Criteria) (ANZICS statement on Death and Organ and Tissue Donation 2018).

- i.

- Typically, the patient has been admitted in the intensive care unit for a period for critical illness. The clinical team has tried all aggressive therapy appropriate for the patient. At some stage, it becomes clear to the treating team that all interventions have failed and there is no chance of recovery. At this point, death is certain and inevitable.

- j.

- This is an incredibly difficult decision, taking days, sometimes even weeks, to arrive at this stage. This period entails the involvement and consultation of multiple teams, often requiring other colleagues to provide second, or even third, opinions to ensure that the decision is right.

- k.

- Only once this decision has been made can the discussion regarding organ donation commence (this stage is called ‘decoupling’, to separate the decision to palliate from organ donation).

- l.

- The medical suitability is checked as mentioned above. The consenting process with the family then starts.

- m.

- The same investigations (as described in the brain death section) then commence.

- n.

- Again, after 12–18 h of intensive work by the team, the patient is transferred to the theatre.

- o.

- The patient is usually taken to a room close to the operating theatre. The end-of-life process is then started by withdrawing all life-sustaining therapies, including taking out the ETT (endotracheal tube), stopping other medications and sometimes starting a small dose of comfort medications so that the patient does not suffer, ensuring that nothing is given to hasten death.

- p.

- The family is usually allowed to stay with the patient until the loved one dies. A doctor then examines the patient and declares death if all the criteria are fulfilled.

- q.

- The patient is then taken to the theatre where the surgeons are already scrubbed and gowned, so that no time is wasted.

- r.

- The organ retrieval surgery takes place (as outlined above).

- s.

- Again, most families would request an imam to bless the patient, and they themselves would continue to pray and recite Quran at the bedside. Every effort is taken by the hospital team to respect these family wishes.

There are a few special points that need to be mentioned here in relation to donation after circulatory death:

- The ‘Decoupling’ process is very important. Extreme effort is taken so that organ donation does not influence the decision for palliation. The process is open, transparent, and consultative. This ensures another principle of organ donation in Islam, which is ‘the donor must not be harmed by organ donation’ (Resolutions of Islamic Fiqh Council of the Organization of the Islamic Conference 1988).

- The patient dies in front of the family if the family wishes them to. The family witness death as it is accepted by the society—that is, when the patient’s heart stops, and they become unresponsive, immobile, and cold. This is a more ‘understandable death’ by the family, in comparison to brain death. The family is then required to say their last goodbyes and let the team take the patient to the operating room. If this cannot happen within a specified time (maximum few minutes), organ donation cannot take place.

- If the patient does not die within the specified period (maximum 90 min in Australia after taking the endotracheal tube (ETT) out), organ donation does not take place. In this case, the patient is usually taken back to the ICU to continue end-of-life care.

These strict time limits are stringently followed to ensure the viability of the organs to be transplanted. After this specified period, organs start to suffer from a lack of enough blood and oxygen supply, causing significant injury and increasing the chances for transplant failure.

Which Organs can be Donated and Transplanted?

Multiple organs can be donated through the above two pathways. However, a lot more people can still be eligible to be tissue donors if they are not suitable for multi-organ donors (Donatelife NSW 2020c).

1. Heart

The heart is vital for living, often called the ‘principle of life’. This is more commonly donated through the brain death pathway. With the emergence of new technologies, heart donation can now be considered via circulatory death pathways as well. During the procedure, the heart must be transplanted as a whole.

2. Lungs

The lungs are essential to oxygenating our body. We have one lung on each side of our chest (right and left). Both lungs can be transplanted to one recipient or be divided and transplanted to two recipients. In certain clinical situations, patients would almost certainly die without a transplantation.

3. Liver

The liver is essential to allowing the ‘cleaning’ of our blood. It also produces bile, which is required for our digestion. There are conditions when, if a liver fails, patients may enter an extremely critical state and die within a short period without a transplant. The liver can be transplanted whole or be split and transplanted into two recipients.

4. Kidneys

Kidneys clean the blood of waste products and fluids. If the kidneys fail, a patient cannot survive for long without undergoing dialysis. However, patients can live on dialysis for years, though with a much shorter life expectancy. Usually, two kidneys are transplanted to two recipients. Depending on the clinical condition of the donor, sometimes both kidneys are required to go to one recipient.

5. Pancreas and Islet cells

The pancreas and Islet cells produce insulin, which is vital to controlling blood sugar levels in the body. A lack of insulin in the body gives rise to the condition known as diabetes. Often, young people suffer devastating complications from type 1 diabetes. The pancreas is often transplanted with the kidneys, as both diseases often coexist. Islet cells are specialized cells in the pancreas responsible for producing insulin, unlike the other cells of pancreas which produce digestive hormones and can be extracted from the pancreas and transplanted accordingly.

6. Tissues

Whilst tissues can also be donated by multi-organ donors, many patients may also qualify as tissue-only donors. As tissues can be donated up to 24 h after death, comparatively, many more people are eligible to donate tissues than organs.

a. Eyes

The eye bank is led by a dedicated team. The team contacts the family if the loved one dies in hospital or a suitable facility. Once consent has been provided, the team then retrieves the eyes—the whole eyes are retrieved and then processed in the eye bank, after which the corneas are transplanted, and other parts are used for research (with the consent of the family). The eye sockets of the donor are transplanted with artificial eyeballs, so that eye contour is maintained for the funeral.

b. Bones

Bones can be donated from multiple sites, such as long bones from the thighs, legs, arms, etc. These bones are processed appropriately to be used by the orthopaedic surgeons during bone surgeries. When a bone is retrieved, the space is filled with artificial structures to maintain the body’s shape for the funeral.

c. Heart valves

There are many diseases that affect the valves of the heart. The heart fails without properly functioning heart valves, and patients may die out of arising complications. Whilst artificial valves are an option for many, human tissue valves remain the most advantageous. If the retrieved heart is not suitable for transplantation, the heart valves can be dissected and prepared for transplantation. The rest of the heart may be used for research if the family consents, or alternatively, returned to the body to be buried or cremated.

6. Medical Suitability

Whether a patient is medically suitable to become an organ donor or not is usually a clinical decision. In other words, there are a few medical conditions that can exclude somebody becoming an organ donor. However, families are often surprised to discover that the ‘contraindications’ are so few and far between.

Anybody can be an organ donor. Though age places some limitations, even very young and very old people (even those over 80 years of age) may be eligible to still be a donor. Smoking and drinking alcohol can influence the decision process, but do not present absolute contraindications. Similarly, there are many medical conditions which people often think would make them unsuitable, however, more often than not, it is to their surprise that they do not.

When the discussion for organ donation starts, the team collates a wide breadth of information from various sources, including family, long-term doctors of the patient and previous notes.

Additionally, multiple investigations during the donation process assist the team in making an informed decision. Often, patients may be permitted to donate one organ and not another; for example, a patient may be able to donate their kidneys but not their liver.

7. Consenting

‘Australia and New Zealand have an ‘opt in’ model of organ donation (Donatelife NSW 2020c). In contrast, an ‘opt out’, ‘presumed consent’ or ‘deemed consent’ model is commonly proposed as a legislative change to increase organ donation rates. In an opt-out model, it is assumed that each member of the community would be prepared to donate unless they register a decision to the contrary…’.(Donatelife NSW 2020c)

In Australia, organ donation depends entirely upon the consent of the family. The consent is given by the ‘Senior Available Next Of Kin’ (SANOK), which is clearly defined in each jurisdiction of the country.

Organ donation in certain countries like Australia can proceed with family or guardian consent. This consent can be given by the patient when he/she was alive or by the family, which conforms to the SANOK definition. In case of a situation where none of the above is available, Islamic leaders and scholars can be involved in such decision making. The consenting comes to the situation when the patient or family accepts the permissibility according to their belief and understandings of Islamic rules. The medical team fully respects the decision of the family.

The consenting process is fair, transparent, and informed. The family, including the SANOK, is given detailed information about every stage of the process, and allowed time to process and ask any questions regarding the procedure. An Islamic leader or a scholar can be invited to hospital at this stage to help the family understand from an Islamic perspective. The family may decide to consult scholars from both views including ‘endorsing; and ‘not endorsing’ organ donation in Islam to help explore all rulings. After answering all questions, the families are then given the opportunity to make their decision. Whatever decision the family makes is respected, maintaining full impartiality. Ultimately, the ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ decision does not influence or impact the patient’s care in any way.

Often, families find it easier to come to their ultimate decision at this stage if they are aware of the final intentions of their loved ones. As such, discussions about organ donation within the family are incredibly important. Again, a potential patient may conduct extensive research into the subject and ultimately decide that they do not wish to become an organ donor, and this decision is treated with complete respect. On the other hand, another potential donor may express interest in the procedure and wish to become a donor after they have died. This decision should always be discussed with the family.

The following extract explains the importance of registering oneself into the organ donor register and taking the step to openly discuss such decisions with one’s family:

‘Organ donation is an altruistic act and a gift of life. As we have seen a single organ donor can save many lives. This is a big incentive for many to help others. That is why 98% of Australians say ‘Yes’ to become an organ donor when they die. But in reality, we see only 64% of families consent for organ donation on an average. Lack of information and family discussion of the decision partly contribute to this low consent rate.

A recent analysis showed that about 93% families agreed to donation when their family member was registered on the Australian Organ Donor Register (AODR) compared to 73% when they knew their family member wanted to be a donor and 52% when the family member was not on the AODR and there was no family discussion on the subject. Most donor families (92%) find comfort in the donation of their loved one’s organs; 50% finding a great deal of comfort and 42% finding some comfort. For these family members, Donation has helped them in their grief (64%) and provided meaning to them (63%).

8. Organ Retrieval Surgery

On 17 June 1950, Dr Richard Lawler performed the world’s first successful kidney transplant on a 44-year-old lady (Life Source. Organ Eye and Tissue Donation 2021). Since then, medicine has evolved and progressed at an incredible rate, with the development of modern technology and new drugs allowing organ transplantation to become an essential part of modern medicine. Through the emergence of new medical technologies and methods, the success rate of organ transplantation today is high (Donatelife NSW 2020c).

The organ retrieval surgery is a highly specialized operation performed by specially trained teams. Multiple teams are involved in organ retrieval, depending upon which organs are to be retrieved. In this example, a generous donor may be suitable to donate only their kidneys. After all preparations are complete, a large team ensures that the patient is treated with principles of dignity and respect maintained. The operation is performed like any other surgery, maintaining full aseptic precautions in the operating theatre. A team leader overseas the whole process. The kidneys are retrieved and then prepared for transport to the transplantation hospital. Working within the limited time at hand, the kidneys go through specific preparation processes for them to be viable in the recipient. By this stage, a vigorous organ allocation process has already taken place prior to the surgery, to adhere to the strict time limitations after the retrieval itself. At the end of the surgery, the patient’s abdomen is sutured carefully and closed. With clothes on, there is no indication of a major surgery or physical disfigurement of the body that can be seen during the funeral.

A donor may have the opportunity to donate multiple organs. In this case, a cardiothoracic team works on the chest area to retrieve the heart and lungs, whilst separate kidney and liver retrieval teams work on the abdomen area. The organs are then prepared to be transported to the transplantation hospital. Again, there remains a limited time by which each organ should be transplanted. Sometimes, machines are utilised to assist in increasing the viability of organs.

The violation of the sanctity of a dead body is forbidden in Islam, as mentioned in the Hadith, ‘Breaking the bone of a dead person is similar (in sin) to breaking the bone of a living person’ (Yaser 2008). As explained above, the retrieval surgery is undertaken by a highly specialised team maintaining full respect and dignity in an operating theatre. Each member of the team ensures that sanctity is never violated. Once the surgery is completed, the body is prepared for family viewing and religious rituals. The body is then handed over to the funeral director, who then washes and prepares the body according to Islamic law for the burial.

9. The Process of Organ Donation as a Snapshot

In explaining a few of the steps of organ donation thus far, it is clear that this is a rigorous process involving many teams (ANZICS Statement on Death and Organ and Tissue Donation 2018).

The process begins with identifying a potential organ donor who has unfortunately become brain dead, or where an end-of-life care discussion has been started. After a preliminary look at the patient’s medical suitability, the specialised organ donation team is involved. This specialised team then requests information from the Australian Organ Donor Registry (AODR), which allows privileged access to information and is released only after the appropriate procedure has been followed.

The AODR information, which may indicate if the patient registered their wishes regarding whether they intended to become an organ donor after death or not (in which case, there will be no registration from the patient), is then conveyed to the family. Whilst all efforts are taken to uphold the patient’s wishes, the final decision regarding the process ultimately rests upon the family. If the family consents to proceed, then the patient’s blood samples are sent for special investigations, as well as ordering several other tests. At this point, a detailed consenting process with the family commences, after which surgical teams are contacted and theatres are organised. All the teams involved undertake multiple meetings to specify plans. As mentioned earlier, this process may take up to 12–18 h. Often, it is difficult for families to wait through this period when they know that their loved one has died or is dying. However, the thought of the gift of life to save more lives always gives them the solace to keep going and follow the process.

Once all the processing has taken place, with all the investigations at hand and teams satisfied with the plans, the patient is then transferred to the theatre, and organ retrieval surgery is done by the surgeons in theatre.

A large team is involved in allocating the organs to appropriate recipients, who are then selected and transported to the transplant hospitals at short notice. The retrieved organs are then transported by the specialised team to the transplant hospital, at which point the recipients have been properly prepared for the procedure. The transplantation then takes place; again, as aforementioned, there is only a limited specified time for each organ to be transplanted.

10. Organ Allocation

The donated organs are allocated to the most suitable recipients on the transplant waiting list. Several globally recognised doctrines address the ethical considerations surrounding organ and tissue donation and serve to provide the foundational principles upon which the procedure is conducted accordingly. The World Health Organization (WHO) guiding principles state that ‘the allocations of organs, cells and tissues processes should be guided by clinical criteria and ethical norms, not financial or other considerations. Allocation rules, defined by appropriately constituted committees, should be equitable, externally justified and transparent’ (Sixty-Third World Health Assembly, World Health Organization 2010).

The Declaration of Istanbul emphasises that organ trafficking, and transplant tourism should be prohibited (International Summit on Transplant Tourism and Organ Trafficking 2008). The Australian and New Zealand Human Tissue Acts governing organ and tissue donation prohibits trading in human organs and tissues. In its 2016 Ethical Guidelines for Organ Transplantation from Deceased Donors, the Australian NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) states, as a general principle, that the ‘donation of organs is an act of altruism, solidarity and community reciprocity that provides significant benefits to those in medical need (National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2016). The above constitutes the guidelines forming the ethical basis for organ allocation to appropriate recipients.

In relation to the procedure itself, numerous transplant waiting lists are maintained for each organ. The appropriate specialist refers a patient to the relevant transplant team. For example, a lung specialist may accordingly refer a patient requiring a lung transplant. The lung transplant team then reviews the patient, takes detailed notes regarding their medical history, and performs a full clinical examination with relevant investigations; upon the completion of these steps, a decision is then made as to whether the patient can be a viable transplant candidate. If any contraindications are found, such as if the patient is still smoking, then they are taken off the transplant waiting list.

Patients are monitored diligently so that the most suitable person receives the organ. For example, if somebody continues to drink alcohol, then they may not be suitable for a liver transplant. Factors such as the mental health of the patient are also considered to ensure that they will be able to adequately look after themselves after the transplant. Additionally, current clinical condition and genetic matching are also considered during the process of organ allocation.

Families can be assured that a large team is involved in maintaining the transplant waiting list and organ allocation, with well-monitored systems in place in Australia ensuring that allocation is always equitable externally justified and transparent.

Those scholars who endorse organ transplantation prohibit the sale of, or trading of, organs. This is ensured in the organ allocation process, which is open and transparent. No incentive is allowed in whatsoever manner to receive advantage in organ allocation in Australia.

11. Organ Donation Campaign—How to Become an Organ Donor

In 2008, the Federal Government of Australia launched a campaign to raise awareness about organ and tissue donation in Australia, after which the National Organ and Tissue Authority with Donatelife agencies from each of the states and territories were established. Many doctors, nurses and other staff were employed to improve organ and tissue donation (Donatelife NSW 2020c). Over the year, these agencies have expanded considerably, so that now, almost all major hospitals have dedicated full-time or part-time staff working on the issue. There has been an extensive amount of education, targeting not only clinical staff, both in and out of the hospital, but the general national population in raising awareness about organ donation. The campaign also includes radio, TV advertisements, and local programs at district and local levels. These activities have revolutionised conceptions of organ donation in Australia, leading it to now become an essential part of any end-of-life discussion.

The Donatelife website (www.donatelife.gov.au, accessed on 20 June 2020) contains a wealth of information which is constantly updated, where every question has an answer to help one discover more about the organ and tissue donation process.

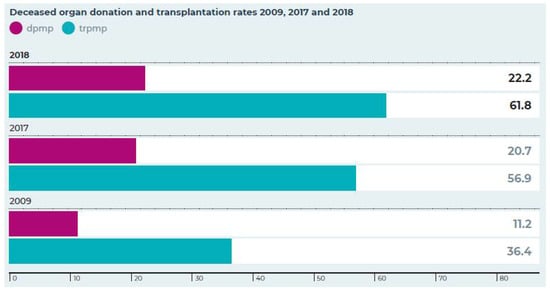

Since the campaign commenced, organ donation rates in Australia have increased from 13.8 PMM (per million population) to more than 22 PPM in 2018 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Deceased organ donation and transplantation rates in 2009, 2017 and 2018. Dpmp—donation per million population, trpmp—transplantation per million population. Source: Australian Donation and Transplantation Report 2018.

We need to make an informed ‘Decision’ and ‘Discuss’ this decision with our family, all alongside registering officially.

Australia maintains the Australian Organ Donor Register (AODR). Joining is simple—a form is available on the Donatelife website, which can be completed online. Printed forms are also available in hospitals/Medicare offices and other health sites. It is essential that we all complete the form and register our decision on the AODR to help them decide during the devastating and stressful time.

12. What’s Real and What’s Not—Debunking the Myths

There are myths and conceptions about organ and tissue donation in society. Most of those are based on fear and lack of information. Some of those myths are discussed here.

‘Are you sure my loved one will never wake up after they diagnose brain death?’

Amongst many other authorities on the matter, the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) prescribes a set of strict criteria that must be met before diagnosing a patient as ‘brain dead’. Families must not confuse brain death with coma—the two are completely different from each other (ANZICS Statement on Death and Organ and Tissue Donation 2018). Once brain cells die, they cannot regenerate, unlike many other organs of our body. A patient in a ‘coma’ is unconscious because their brain is injured in some way, however not all functions of the brain are lost. In this case, some brain functions may recover, to an extent, once acute injury and swelling are resolved. When one becomes brain dead, all brain functions are permanently lost. Many clinical and radiological tests are employed to clearly distinguish brain death from coma (ANZICS Statement on Death and Organ and Tissue Donation 2018)

‘If I am registered as an organ and tissue donor, doctors may not work as hard to save my life’

Doctors and nurses work according to the ethics of ‘Beneficence’, which involves actions that promote the wellbeing and healing of their patients, and ‘Primum non nocere’, which translates to ‘first, do no harm’ (Basic Principles of Medical Ethics 2008). Organ and tissue donation never influences any decision-making while a patient is being actively treated, and the procedures are only considered after all efforts have failed. Every effort is taken to ‘decouple’ active treatment and organ donation. Additionally, medical staff cannot access the Australian Organ Donor Register (AODR) without involving a special team. Clinical staff can request that information only after a discussion of a potential organ donation has taken place. The authorised team then decides whether to access the information contained in the AODR.

‘Will they respect my body and maintain dignity when removing organs?’

Organ donation surgeries are no different from any other surgical operations and are performed by highly skilled doctors. The procedure is undertaken in an operating theatre under full aseptic precaution (Royal Australasian College of Surgeon 2021). Throughout the duration of the procedure, the donor is always treated with full dignity and respect, wherein incisions are kept to a minimum to ensure that donation surgeries do not alter the appearance of the body. The donor’s family are then able to view the body after surgery, even retaining the option of holding an open casket funeral if they desire.

‘How much will it cost me’

Organ donation does not cost the donor’s family any money. All expenses involved are paid for by the hospital/government (Donatelife NSW 2020c).

‘I am concerned that organ donation may not be supported by my religion’

The relationship between organ donation and religion has been extensively discussed by religious scholars and relevant scriptures consulted for all major religions of the world. The procedure is generally supported by all major religions as an ultimate act of generosity. The Donatelife website (www.donatelife.gov.au, accessed on 18 June 2020, resources) provides extensive information about this. It is important to know that every effort is made by the hospital staff to accommodate any religious and cultural end-of-life rituals for potential organ donors and their families. The staff can also organise for religious leaders to come to the hospital to support end-of-life care and clarify any questions.

‘Why do I still need to tell my family if I have already registered with AODR?’

Family discussion is important, as donation will not proceed without family consent. If the family knows the wishes of the loved one, it makes their decision-making process much easier during such a devastating and stressful time. One of the main reasons why families decline donation is that they simply do not know the wishes of their loved ones. Therefore, we encourage discussing an informed decision with the family, even if you have registered with the AODR.

‘Can my decision be overridden by my family?’

Studies have shown that families most often follow the decision of the loved one if it is known to them (Donatelife NSW 2020c). However, in rare circumstances, this decision may be overridden by the family, for which there are usually specific reasons for doing so. Ultimately, every effort is made to uphold the wishes of the patient.

‘I do not want my organs to go to a person with bad habits such as an alcoholic or a heavy smoker’

People on the transplant waiting list are closely monitored and followed up on. However, directed donation after death is not allowed in Australia. There are extensive criteria to define the list of patients who need transplantation, and patients may be excluded from the list if these criteria are not followed. For example, a patient will be removed from the liver transplantation list if the person continues to, or re-starts, drinking alcohol. Ultimately, organ and tissue donation signify an altruistic gift to save or significantly improve the quality of life for others (Transplant Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) 2010).

‘Could my organs and tissues be sold for profit?’

Treating a human being as a commodity for organ trade is illegal and will remain illegal in Australia. Australian laws are consistent with ethical principles set by the international transplant community, the World Health Organization, and the World Health Assembly. Organ and tissue donation are a generous gift and not for sale, and there are numerous international efforts to stop organ trafficking around the globe (International Summit on Transplant Tourism and Organ Trafficking 2008).

‘I want to ensure the recipient is looking after my loved one’s organ. I want to meet them’.

This is not possible in Australia. By law, health professionals involved in donation and transplantation must keep the identity of donors and recipients anonymous. It is anticipated that introducing these two families to each other may create more problems than solutions. However, the two families can write to each other anonymously through Donatelife agencies (Donatelife NSW 2020c).

‘The organ will be given to a non-Muslim person which is not allowed in Islam’

Despite there being some confusion about this, the overwhelming evidentiary support confirms that organ donation to non-Muslim recipients is, in fact, allowed in Islam. When a funeral procession passed by the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), and he stood up for it, in response to his paying respects, the companions remarked ‘O Messenger of Allah! It is the funeral of a Jews’. However, the Prophet (PBUH) replied by stating that he was aware of this fact and affirmed that ‘When you see a funeral (Muslim or non-Muslims) then stand for it’ (Sahih Al Bukhari 2021).

These are just some of the numerous accounts from Islamic scripture which demonstrate the importance of the principles of altruism and tolerance in Islam, ultimately adding to a support for organ donation and transplantation.

‘Will my funerals be delayed by the organ donation process?’

‘Necessity overrides prohibition’—Al-Darurat Tubih Al-Mahzurat.

The above is an Islamic principle recognised by all Muslim scholars. Despite the provisions allowed by Islam, organ donation generally does not delay the funeral. Funeral directors usually require some time to organise everything; by the time that most funeral directors are ready, the donation process is usually complete.

‘How do I register my decision?’

Please ‘Discover’ the facts about organ and tissue donation on the Donatelife website (www.donatelife.gov.au, accessed on 17 May 2021, resources), where a wealth of information is available regarding the details and commonly asked questions for the procedure. Once an informed ‘Decision’ has been made, potential donors can complete an online form on the Donatelife website, or alternatively, visit any state or territory health site to complete a form to register the decision on AODR. Potential donors can also specify which organs that they want to donate. Please do not forget to ‘Discuss’ the decision with your family.

People from all walks of life need life-changing transplant surgery. Australia has demonstrated some of the best outcomes of organ transplant surgery in the world, yet Australia’s organ donation rates remain comparatively a lot lower than many other developed nations. Therefore, we encourage everyone to work towards raising awareness of, and committing to, delivering the gift of generosity in our communities.

13. Conclusions

One organ and tissue donor can save up to ten lives and improve the quality of lives of many more. It is imperative to understand what it means and what is involved in the whole process. Deceased organ donation requires a good understanding of death, whether death is defined by circulatory criteria or by neurological criteria. The neurological determination of death can be a little difficult to comprehend, as the loved one feels warm, chest is moving due to the ventilator and the monitor is showing heart activities. Medical communities and the majority of Islamic leaders around the world have gone through extensive research and discussed to arrive at the conclusion that the medical definition of death consists with death, as defined in Islamic jurisprudence and endorsed organ donation as a good deed. However, another school of Islamic scholars differs on the definition of death and the permissibility of organ donation in Islam. To maintain the sanctity of the dead, they do not endorse organ donation. This difference in opinion is the centre point of controversy. Every Muslim has the right to explore both sides of the view by exploring the rulings and then make the decision. Any decision taken by the family, either ‘Yes’ or ‘No’, is respected. A family member, or even an Islamic leader, if the family wishes so, can witness the rigorous process and examinations to determine death. It is imperative to know that organ donation takes place only once death is confirmed, to ensure that no harm is done to the donor, as per Islamic law. Many teams then get involved to uphold the wishes of the patient with fully informed consent. All Islamic rituals and practices are allowed to take place, including the recital of the Quran and prayers by Imams and family. The loved one is cared for by a dedicated team, and retrieval surgery is done with full dignity and respect. The sanctity of the body is never broken by any team. The organ allocation system in Australia is highly transparent, open, and scientifically based. Organ trading is illegal in Australia, like many other countries, as it is in Islam. There are misconceptions about organ donation and transplantation in the Muslim community that we have attempted to explain and answer. Family is the final decision maker. Whatever the family decides after detailed information is fully respected. The care of the loved one is not affected by the decision. May Allah help us all understand the facts and help us decide the right decision at the right moment.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- ANZICS Statement on Death and Organ and Tissue Donation. 2018. Available online: www.anzics.com.au (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Basic Principles of Medical Ethics. 2008. The Stanford University. Available online: www.stanford.edu (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Butrovic, Amila. 2016. Carved in Stone, Etched in Memory. London: Routledge, p. 34. ISBN 978-1-317-16957-4. [Google Scholar]

- Census Australia. 2016. The Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online: www.abs.gov.au (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Cushing, Harvey. 1902. Some experimental and clinical observations concerning states of increased intracranial tension. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 124: 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donatelife NSW. 2018. Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation Outcomes in Australia. Available online: www.donatelife.gov.au (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Donatelife NSW. 2020a. My Dad, His Legacy. In Book of Life; Donatelife NSW: Written by Charlotte. vol. 18, p. 11. Available online: https://www.donatelife.gov.au/sites/default/files/book_of_life_volume_18.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Donatelife NSW. 2020b. The Ultimate Gift. In Book of Life; Donatelife NSW: Written by Kate. vol. 1, p. 33. Available online: https://www.donatelife.gov.au/sites/default/files/book_of_life_-volume_1.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Donatelife NSW. 2020c. Multicultural and Faith Communities. Available online: https://www.donatelife.gov.au/resources/multicultural-and-faith-communities (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Harvey, W. 1628. Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals). Available online: en.wikipedia.org (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- International Summit on Transplant Tourism and Organ Trafficking. 2008. The Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 3: 1227–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khadija, Musa. 2016. ‘Umdat al-Najir ‘ala al-Ashbah w’al Naza’ ir. Edited by Bilingual. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Life Source. Organ Eye and Tissue Donation. 2021. Early Organ Transplants. Available online: www.lifesource.org (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Mollaret, P., and M. Goulon. 1959. Le coma de passe (memoire preliminaire) (The depassed coma (preliminary report) (sic). Revue Neurology 101: 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Multicultural Eid Festival and Fair. 2013. Analysis of Survey Results at the Multi-Cultural Eid Festival. August 18. Available online: https://www.meff.com.au/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). 2016. Ethical Guidelines for Organ Transplantation from Deceased Donors; Canberra: National Health and Research Council. Available online: www.nhmrc.gov.au (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Padela, Aasim I., and Jasser Auda. 2020. The Moral Status of Organ Donation and Transplantation Within Islamic Law: The Fiqh Council Of North America’S Position. Transplant Direct 6: e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rady, Mohammad Y., and Joseph L. Verhejde. 2014. The Moral Code in Islam and Organ Donation in Western Countries: Reinterpreting Religious Scriptures to Meet Utilitarian Medical Objectives. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 9: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Resolution of the Council of Islamic Jurisprudence on Resuscitation Apparatus. 1986. Decision No. (5) D 3/07/86. Paper presented at Thirds Meeting, Amman, Jordan, October 8–13. Safar 1407AH/11-16 October 1986 CE. [Google Scholar]

- Resolutions of Islamic Fiqh Council of the Organization of the Islamic Conference. 1988. Paper presented at Fourth Conference, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, January 18–23. Safar 1408 AH/6-11 February 1988 CE.

- Royal Australasian College of Surgeon. 2021. Available online: www.surgeons.org (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Sahih Al Bukhari. 2021. vol. 2. Book 23. Number 398. Available online: www.sahih-bukhari.com (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Shemie, Sam D., Laura Hornby, Andrew Baker, Jeanne Teitelbaum, Sylvia Torrance, Kimberly Young, Alexander M Capron, James L Bernat, Luc Noel, and The International Guidelines for Determination of Death Phase 1 Participants, in Collaboration with the World Health Organization. 2014. International guideline development for the determination of death. Intensive Care Medicine 40: 788–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sixty-Third World Health Assembly, and World Health Organization. 2010. WHO guiding principles on human cells, tissue, and organ transplantation. Cell and Tissue Banking 11: 413–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet. 2011. Religion, organ transplantation and the definition of death. Editorial 377: 271. [Google Scholar]

- Transplant Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ). 2010. Available online: www.tsanz.com.au (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Truog, R. D., and W. M. Robinson. 2003. Role of Brain Death and the Dead Donor Rule in the Ethics of Organ Donation. Critical Care Medicine 31: 2391–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Population Review. 2021. Muslim Population by Regions. Available online: www.worldpopulationreview.com (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Yaser, Qadhi. 2008. English Translation of Sunan Abu Dawud. Compiled by Imam Hafiz Abu Dawud Sulaiman bin Ash’ath. Davao City: Ryadh Darussalam. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).