Religious Values and Educational Norms among Catholic and Protestant Teachers in Hungary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Hypothesis

2.2. Method

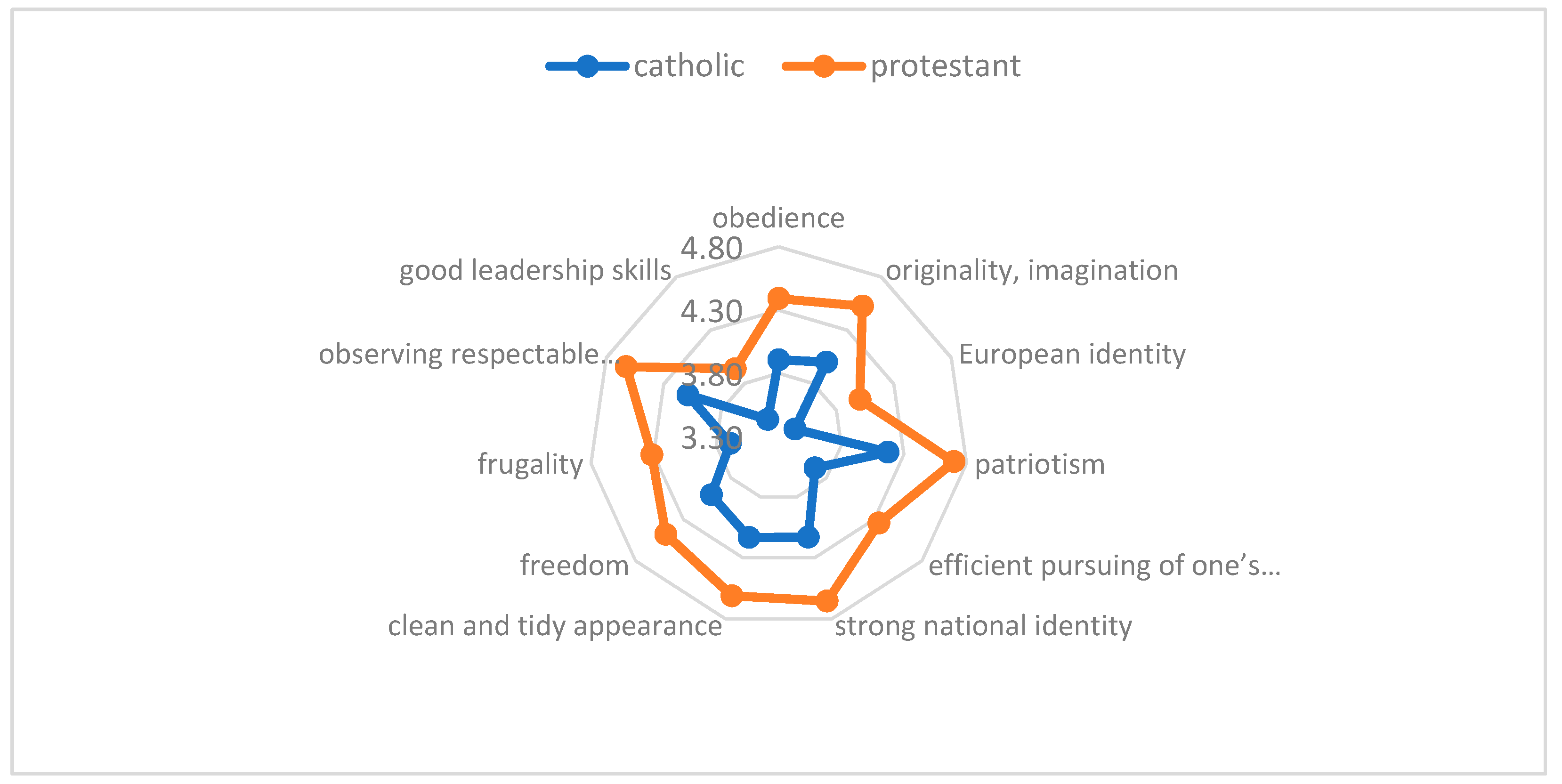

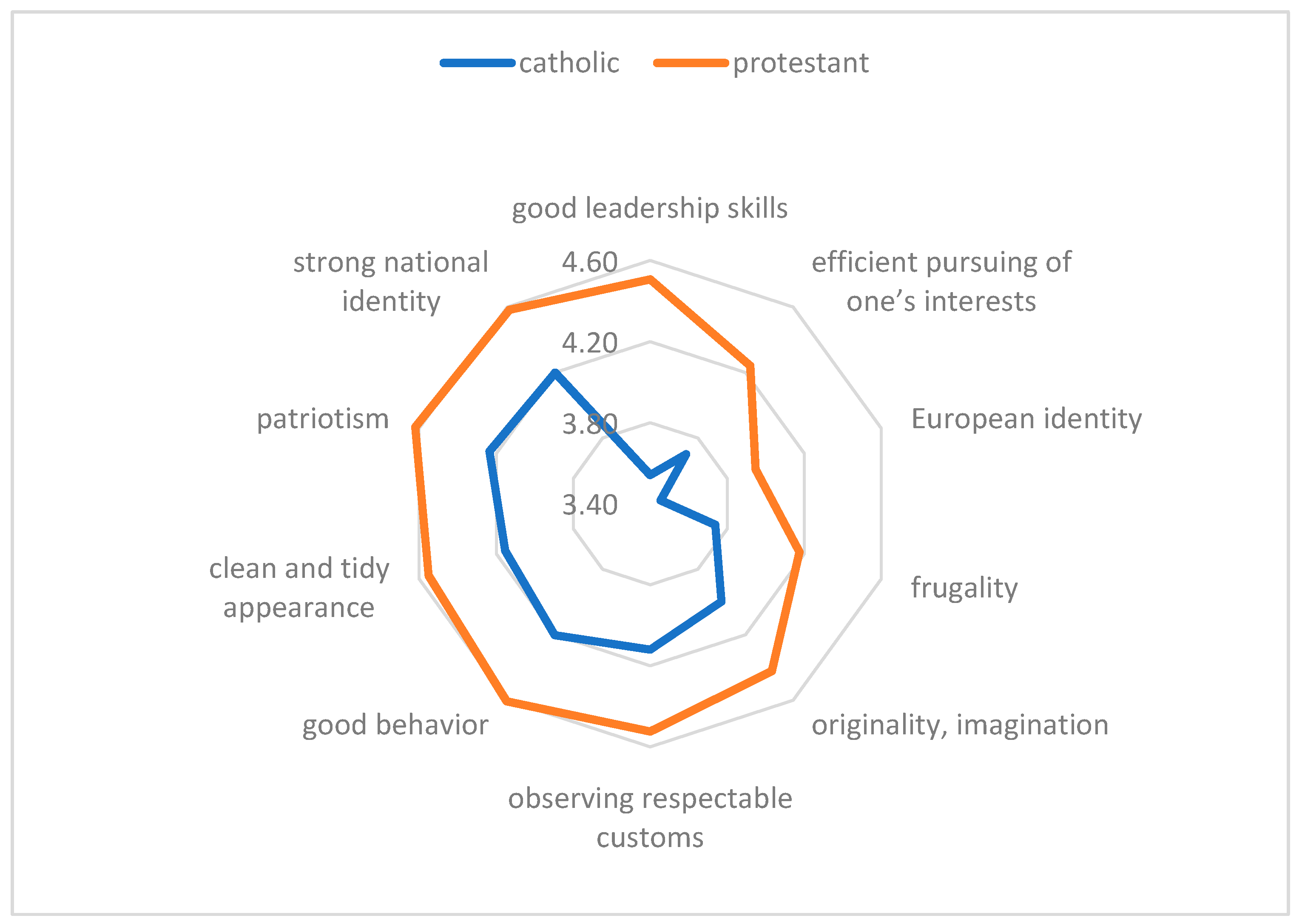

3. Results

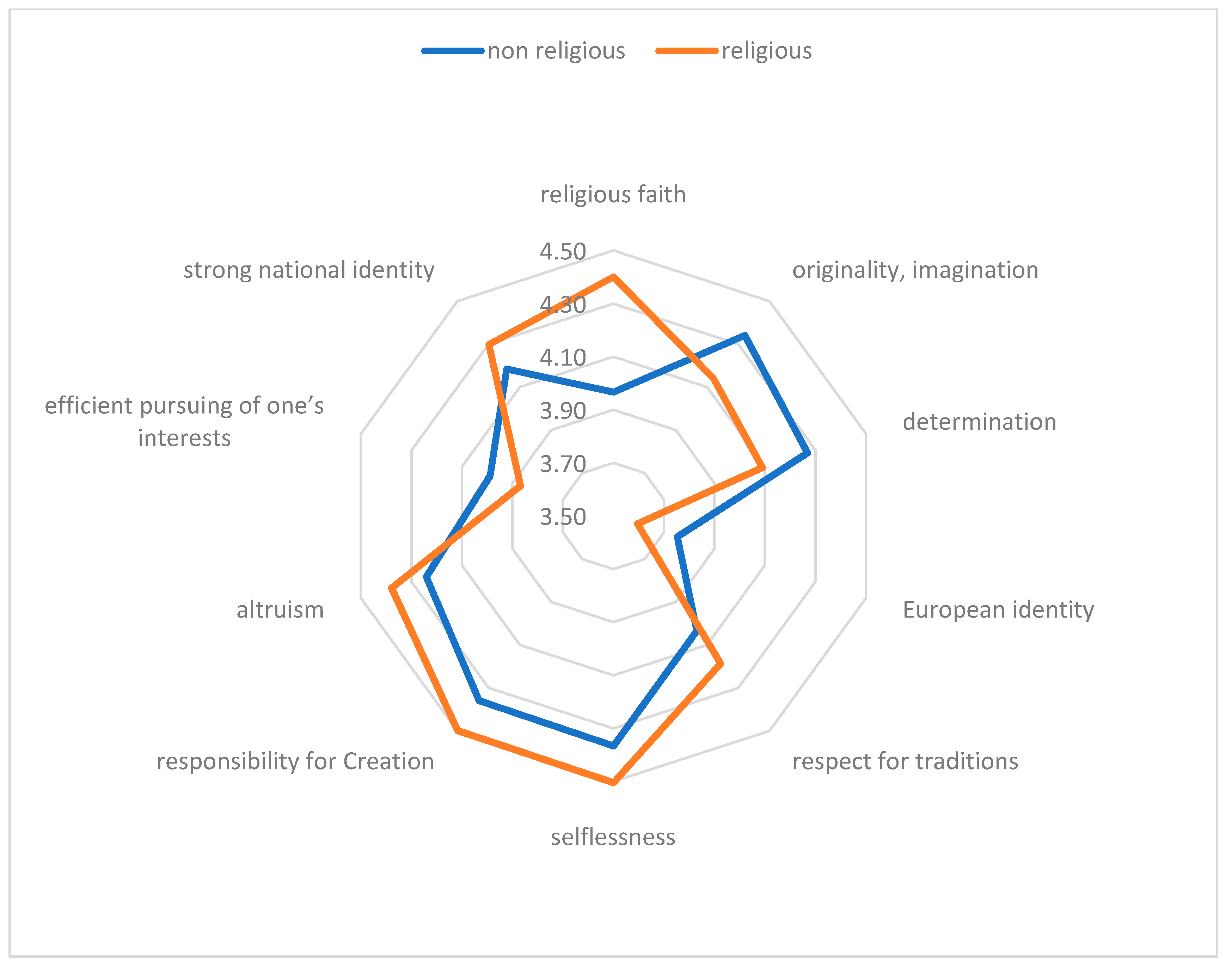

4. The Effect of Religiosity on Educational Values

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | (1) I am religious; I follow the teaching of the Church. (2) I am religious on my way. (3) I cannot tell if I were religious. (4) I am not religious. (5) Definitely not religious. |

| 2 | The examined values are: leadership skills, assertion of one’s interests, European identity, thrift, originality, upholding respectable customs, good behavior, arranged exterior, patriotism, national consciousness, sturdiness, obedience, courtesy, inner harmony, critical sense, freedom, word reception loyalty, patience, logical thinking, imagination, fantasy, love of work, independence, diligence, religious faith responsibility for the created world, respect for tradition, altruism, respect for others, tolerance, willingness to serve, being for others, Self-control, credibility, merriment, serenity, sense of responsibility, sincerity, reliability, spiritual fulfillment. |

References

- Allport, Gordon W., and J. Michael Ross. 1967. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacskai, Katinka, and Gabriella Kelemen. 2019. Imádkozva és dolgozva. Helyzetkép a tiszántú-li református általános iskolákról az OKM 2017. évi adatai alapján. [Praying and working. Situation of the Trans-Tisza Reformed primary schools based on the 2017 data of the National Student Assessment]. In Kozma Polisz. Tanulmányok Kozma Tamás 80. Születésnapjára. [Studies for Tamás Kozma’s 80th birthday]. Edited by Gabriella Pusztai, Ágnes Engler and Zsófia Kocsis. Debrecen: CHERD, pp. 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Baños, Ruth Vilá, Monserrat Freixa Niella, Angelina Sánchez-Martí, and María José Rubio Hurtado. 2019. Head teachers’ attitudes towards religious diversity and interreligious dialogue and their implications for secondary schools in Catalonia. British Journal of Religious Education 2: 180–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechert, Insa. 2021. Of Pride and Prejudice—A Cross-National Exploration of Atheists’ National Pride. Religions 12: 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, James S., Thomas Hoffer, and Sally Kilgore. 1982. High School Achievement: Public, Catholic, and Private Schools Compared. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Corten, Robert, and Jaap Dronkers. 2006. School Achievement of Pupils from the Lower Strata in Public, Private Government-Dependent and Private, Government-Independent Schools: A cross-national test of the Coleman-Hoffer thesis. Educational Research and Evaluation 12: 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, Alfred, and Darren E. Sherkat. 1997. The impact of Protestant fundamentalism on educational attainment. American Sociological Review. 62: 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davie, Grace. 2012. From Believing without Belonging to Vicarious Religion: Understanding the Patterns of Religion in Modern Europe. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, Catilin. 2004. Constructing the ethos of tolerance and respect in an integrated school: The role of teachers. British Educational Research Journal 30: 263–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronkers, Jaap, and Silvia Avram. 2015. What can international comparisons teach us about school choice non-governmental schools in Europe? Comparative Education 51: 118–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronkers, Jaap, and Péter Róbert. 2004. Has educational sector any impact on school effectiveness in Hungary? A comparison of the public and the newly established religious grammar schools. European Societies 6: 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Émil. 1897. Le Suicide: Étude de sociologie [Suicide: A Study in Sociology]. Paris: Félix Arcan Éditeur. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, Gegory, John McCormick, and Narottam Bhindi. 2018. A social cognitive framework for examining the work of Catholic religious education teachers in Australian high schools. British Journal of Religious Education 41: 134–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ene, Ionel, and Juliana Barna. 2015. Religious Education and Teachers’ Role in Students’ Formation towards Social Integration. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 180: 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füller, Christian. 2010. Ausweg Privatschulen? Was sie Besser Können, Woran sie Scheitern [Private Schools Way Out? What They Can Do Better, What They Fail]. Hamburg: Körber Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Heinz, Manuela, Kevin Davison, and Elaine Keane. 2018. I will do it but religion is a very personal thing’: Teacher education applicants’ attitudes towards teaching religion in Ireland. European Journal of Teacher Education 41: 232–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynson, Meghan. 2021. A Balinese ‘Call to Prayer’: Sounding Religious Nationalism and Local Identity in the Puja Tri Sandhya. Religions 12: 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imre, Anna. 2005. A felekezeti középiskolák jellemzői a statisztikai adatok tükrében [Characteristic of the Religious Secondary Schools in the Light of Statistic]. Educatio 3: 475–491. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, Jacqueline Jordan. 1989. Beyond role models: An examination of cultural influences on the pedagogical perspectives of Black teachers. Peabody Journal of Education 66: 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Hei C. 1977. The Relationship of Protestant Ethic Beliefs and Values to Achievement. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 16: 255–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, Melvin L. 1963. Social class and parent-child relationships: An interpretation. American Journal of Sociology 68: 471–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrer, Evelyn. 2008. Religion, Economics and Demography the Effects of Religion on Education, Work, and the Family. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lenski, Gerhard. 1961. The Religious Factor. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Leyser, Yona, and Shlomo Romi. 2008. Religion and attitudes of college preservice teachers toward students with disabilities: Implications for higher education. Higher Education 55: 703–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancebón, María Jesús, and Manuel A. Muñiz. 2008. Private versus Public High Schools in Spain: Disentangling Managerial and Programme Efficiencies. The Journal of the Operational Research Society 59: 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancebón, María Jesús, Jorge Calero, Álvaro Choi, and Domingo P. Ximénez-de-Embún. 2012. The Efficiency of Public and Publicly Subsidized High Schools in Spain: Evidence from Pisa-2006. Journal of the Operational Research Society 63: 1516–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Johanna Janna, Gerdien D. Bertram-Troost, A. de Kock, A. de Muynck, and Marcel Barnard. 2019. Stimulating Inquisitiveness: Teachers at Orthodox Protestant Schools about their Roles in Religious Socialization. Religious Education 114: 513–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, Frank. 2016. The Three Meanings of Meaning in Life: Distinguishing Coherence, Purpose, and Significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology 11: 531–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maussen, Marcel, and Floris Vermeulen. 2014. Liberal Equality and Toleration for Conservative Religious Minorities. Decreasing Opportunities for Religious Schools in the Netherlands? Comparative Education 51: 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, H. Richard. 2006. The promise of Black teachers’ success with Black students. Educational Foundations 20: 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Morvai, Laura. 2017. The Effectiveness of Protestant High School Students in the Light of the Hungarian National Competence Measure 2014 Database. Hungarian Educational Research Journal 7: 252–68. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Jason. 2010. Teacher Dispositions and Religious Identity in the Public School: Two Case Studies. Journal of Negro Education 79: 335–53. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, Graeme, David Smith, and Jo Fraser-Pearce. 2021. Irreligious Educators? An Empirical Study of the Academic Qualifications, (A)theistic Positionality, and Religious Belief of Religious Education Teachers in England and Scotland. Religions 12: 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, Gabriella. 2004. The Latent Function of Denominational Schools in Hungary. In Sociology of Religion in Hungary: Work in Progress. Edited by Miklós Tomka. Budapest: Pázmány Péter Catholic Univerity, pp. 109–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pusztai, Gabriella. 2006. Community and Social Capital in Hungarian Denominational Schools Today. Religion and Society in Central and Eastern Europe 1: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pusztai, Gabriella. 2020. A vallásosság nevelésszociológiája. [Sociology of Religious Education]. Budapest: Gondolat. [Google Scholar]

- Pusztai, Gabriella, and Katinka Bacskai. 2015. Parochial Schools and PISA Effectiveness in Three Central European Countries. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Social Analysis 5: 145–61. [Google Scholar]

- Pusztai, Gabriella, and Zsuzsanna Demeter-Karászi. 2019. Analysis of Religious Socialization Based on Interviews Conducted with Young Adults. Religions 10: 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, Gabriella, and Mihály Fónai. 2012. Asymmetric students relations and deprofessionalization: The case of teacher training. In Third Mission of Higher Education in a Cross-Border Region. Edited by Gabriella Pusztai, Adrian Hatos and Timea Czeglédi. Debrecen: University of Debrecen, CHERD, pp. 114–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pusztai, Gabriella, and Ágnes Inántsy-Pap. 2016. An Underground Church-run School during the Communist Rule in Hungary (1948–1990). Historia y Memoria de la Educación 4: 177–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusztai, Gabriella, and Laura Morvai, eds. 2015. Pálya–Modell. Igények és Lehetőségek a Pedagógus-Továbbképzés Változó Rendszerében [Career-Model. Needs and Opportunities in the Changing System of Teacher Training]. Nagyvárad and Budapest: Partium P.P.S U.M.K. [Google Scholar]

- Quiocho, Alice, and Frencisco Rios. 2000. The power of their presence: Minority group teachers and schooling. Review of Educational Research 70: 485–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis, Vanessa Delpierre, and Rebecca Dernelle. 2004. Values and religiosity: A meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz’s model. Personality and Individual Differences 37: 721–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H., and Sipke Huismans. 1995. Value priorities and religiosity in four Western religions. Social Psychology Quarterly 58: 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, Keith. 1997. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Catholicism: Ideological and institutional constraints on system change in English and French primary schooling. Comparative Education 33: 329–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standfest, Claudia, Olaf Köller, and Anette Scheunpflug. 2005. leben–lernen–glauben. Zur Qualität evangelischer Schulen [Live–Learn–Believe. On the Quality of Protestant Schools]. Münster: Waxman. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Rodney, and Roger Finke. 2000. Acts of Faith: Explaining the Human Side of Religion. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Sandra, and Ravinder Kaur Sidhu. 2012. Supporting refugee students in schools: What constitutes inclusive education? International Journal of Inclusive Education 16: 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen, Elmer John. 2013. Evangelism in the Classroom. Journal of Education & Christian Belief 17: 221–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth, Sarah M. 2015. A Qualitative Study on How a Teacher’s Religious Beliefs Affect the Choices They Make in the Classroom. Undergraduate Honors Thesis, Otterbein University, Westerville, OH, USA; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 2018. Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus [The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism]. Cologne: Anaconda Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Weiß, Manfred. 2011. Allgemeinbildende Privatschulen in Deutschland. Bereicherung oder Gefährdung des öffentlichen Schulwesens? [General Education Private Schools in Germany. Enrichment or Endangerment of the Public School System]. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Weiß, Manfred. 2012. Bessere Qualität der Schulbildung durch Privatschulen? [Better quality of school education through private schools?]. In Private Schulen in Deutschland. Entwicklungen–ProfileKontroversen. Edited by Ullrich Heiner and Susanne Strunck. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Weiß, Manfred, and Corinna Preuschoff. 2004. Schülerleistungen im staatlichen und privaten Schulen im Vergleich [Student performance in public and private schools in comparison]. In Die Institution Schule und die Lebenswelt der Schüler. Edited by Gundel Schümer, Klaus-Jürgen Tillmann and Manfred Weiß. Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 39–71. [Google Scholar]

- Weiß, Manfred, and Corinna Preuschoff. 2006. Gibt es einen Privatschuleffekt? Ergebnisse eines Schulleistungsvergleichs auf der Basis von Daten aus PISA-E [Is there a private school effect? Results of a school performance comparison based on data from PISA-E]. In Evidenzbasierte Bildungspolitik: Beiträge der Bildungsökonomie. Edited by Manfred Weiß. Berlin: Dunker & Humblot, pp. 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- White, Kimberly R. 2010. Asking sacred questions: Understanding religion’s impact on teacher belief and action. Religion and Education 37: 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Religious Self-Classification | Catholic Institutions | Protestant Institutions |

|---|---|---|

| Observes the rules of the church | 76.1% | 65.2% |

| Religious in their own way | 20.0% | 30.8% |

| Uncertain | 0.8% | 0.7% |

| Not religious | 1.2% | 1.1% |

| Refused to answer | 1.9% | 2.2% |

| N= | 806 | 328 |

| Religious Self-Classification | Old | New |

|---|---|---|

| Observes the rules of the church | 74.4% | 57.6% |

| Religious in their own way | 23.8% | 36.7% |

| Uncertain | 0.6% | 0.6% |

| Not religious | - | 1.9% |

| Refused to answer | 1.3% | 3.2% |

| N= | 160 | 158 |

| Christian and Non-Christian Religious Tenets | Catholic Institutions | Old Protestant Institutions | New Protestant Institutions | F | ANOVA Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| God | 4.62 | 4.87 | 4.66 | 9.046 | ** |

| Resurrection | 4.26 | 4.64 | 4.05 | 20.41 | *** |

| Heaven | 4.45 | 4.60 | 4.25 | 8.62 | ** |

| Devil | 3.84 | 3.43 | 3.13 | 2.41 | ns |

| Hell | 3.88 | 3.40 | 3.12 | 2.01 | ns |

| Saints | 4.31 | 3.03 | 3.66 | 12.16 | *** |

| Holy Trinity | 4.43 | 4.65 | 4.34 | 7.0 | ** |

| Immaculate Conception | 4.07 | 4.24 | 3.61 | 13.84 | *** |

| Miracles | 3.70 | 3.60 | 3.41 | 1.23 | ns |

| Life after death | 4.25 | 4.27 | 4.01 | 1.72 | ns |

| Telepathy | 2.40 | 2.22 | 2.4 | 1.3 | ns |

| UFOs | 2.06 | 1.57 | 1.54 | 0.35 | ns |

| Horoscopes | 1.93 | 1.26 | 1.6 | 14.23 | *** |

| Kabbalah/Talismans | 1.68 | 1.19 | 1.48 | 10.9 | ** |

| Reincarnation | 1.68 | 1.60 | 1.86 | 3.88 | * |

| Magic | 1.60 | 1.15 | 1.41 | 9.6 | ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pusztai, G.; Bacskai, K.; Morvai, L. Religious Values and Educational Norms among Catholic and Protestant Teachers in Hungary. Religions 2021, 12, 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100805

Pusztai G, Bacskai K, Morvai L. Religious Values and Educational Norms among Catholic and Protestant Teachers in Hungary. Religions. 2021; 12(10):805. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100805

Chicago/Turabian StylePusztai, Gabriella, Katinka Bacskai, and Laura Morvai. 2021. "Religious Values and Educational Norms among Catholic and Protestant Teachers in Hungary" Religions 12, no. 10: 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100805

APA StylePusztai, G., Bacskai, K., & Morvai, L. (2021). Religious Values and Educational Norms among Catholic and Protestant Teachers in Hungary. Religions, 12(10), 805. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100805