Abstract

This paper examines the interaction between state power and the everyday life of ordinary Chinese Singaporeans by looking at the Hungry Ghost Festival as a contested category. The paper first develops a theoretical framework building on previous scholars’ examination of the contestation of space and the negotiation of power between state authorities and the public in Singapore. This is followed by a short review of how the Hungry Ghost Festival was celebrated in earlier times in Singapore. The next section of the paper looks at the differences between the celebrations in the past and in contemporary Singapore. The following section focuses on data found in local newspapers on Getai events of the 2017 Lunar Seventh Month. Finally, I identify characteristics of the Ghost Festival in contemporary Singapore by looking at how Getai is performed around Singapore and woven into the fabric of Singaporean daily life.

1. Introduction

In traditional Chinese culture, people believe that the gates of hell are unlocked and the souls in the underworld roam around the world of the living and search for food in the lunar seventh month. Festivals in this lunar month are known as the Yulan Festival (or the Ullambana Festival 盂蘭節) in Buddhism and the Zhongyuan Festival (中元節) in Taoism. These rites are commonly called the Hungry Ghost Festival by ordinary people. The rituals and practices dedicated to the ancestors and the souls of deceased people in both Buddhist and Taoist traditions reflect the imagination of the afterlife in Chinese culture.

In order to pray for peace in the living world and demonstrate filial piety to the ancestors, people burn paper money, along with other paper offerings representing various items like cars or jewelry, and offer sacrifices to the gods, ghosts and ancestors, the three major objects of worship in Chinese cosmology. The rituals and practices to these transcendent, supernatural, or numinous beings reveal how Chinese imagine and conceptualize ‘the underworld’ as well as ‘the souls of the dead’ (Wolf 1974). The Hungry Ghost Festival is an event showing how Chinese people perform rituals to gods, ghosts and ancestors in a visible and material way.

These kinds of practices show how individuals activate the traditional Hungry Ghost Festival in their own ways. Apart from individual practices, more organized events, which aim to appease the dead spirits, are organized by various communities of different neighborhoods and they are called ritual festivals (Fa Hui 法會 or Sheng Hui 勝會). This is a collective event held in public spaces in which the whole community is involved.

The Hungry Ghost Festival originated in Indian Buddhism. According to Teiser (1988), the Hungry Ghost Festival originated with the story in Ullambana Sutra of Buddhism but later mixed in aspects of traditional Chinese worship of ghosts and ancestors during the Tang Dynasty. He claimed that the Buddhist story could gain popularity in China and became the core narrative of the Chinese Hungry Ghost ceremonies because the Indian myth of Ullambana Sutra had been mixed with a Chinese legend of Mulian rescuing his mother, thereby reconciling Buddhism with Chinese ideas of filial piety. As a result, the canonical scriptures of Buddhism provide core values of the Hungry Ghost Festival but the visible rites of the Ghost ceremonies are a mixture of Taoist practices and folk traditions. The support from the imperial court as well as the general public endowed the Hungry Ghost Festival with new and different meanings (Chen 2015, p. 7). In many previous studies, scholars were eager to discover the origins of the Hungry Ghost Festival. They would conduct their research by analyzing various archival documents or Buddhist scriptures (Teiser 1988; Karashima 2013).

On the other hand, some scholars also explored the Hungry Ghost Festival by looking at these collective events in different regions. Rituals of offering and burning during the period of the Hungry Ghost Festival are still performed in many Chinese communities. In Taiwan, large scale ceremonies during the Hungry Ghost Festival performed by Buddhist monks and Taoist ritual masters are widespread (Cheung 2012). In some regions of mainland China, including Shandong, the Chung Yuan Festival is still celebrated among the general public (Diao and Zhao 2015). In Hong Kong, the Hungry Ghost Festival ceremonies are organized by Chaozhou migrants and these rites are deeply related to their sense of collective memory (Chen 2015).

Singapore, a cosmopolitan city-state with a majority Chinese population, also maintains this traditional Chinese festival. Getai, boisterous staged singing and dialogue productions, are a significant feature of the Singapore Hungry Ghost Festival. Their role also helps explain another facet of the Hungry Ghost Festival, namely how these practices are internalized as an everyday life activity for the local Chinese.

In this paper, I examine the interaction between state power and the everyday life of ordinary Chinese Singaporeans by looking at the Hungry Ghost Festival as a contested category. The first part of the paper develops a theoretical framework of the research building on previous scholars’ examination of the contestation of space and the negotiation of power between state authorities and the public in Singapore. This is followed by a short review of how the Hungry Ghost Festival was celebrated in earlier times in Singapore. The next section of the paper looks at the differences between the celebrations in the past and in contemporary Singapore. The following section focuses on the data found in local newspapers. Finally, I will identify characteristics of the Hungry Ghost Festival in contemporary Singapore by looking at how Getai is performed around Singapore and woven into the fabric of Singaporean daily life.

2. Theoretical Framework

Scholars have mainly focused on two aspects of the Hungry Ghost Festival. Some searched for historical and doctrinal origins of the festival (Teiser 1988). Others tried to understand the Hungry Ghost Festival from an anthropological perspective by looking at collective events in distinct regions, using ethnographic research. For example, Jean DeBernardi examined the Hungry Ghost Festival in Penang, Malaysia in 1984 (DeBernardi 1984). Professor Choi Chi Cheung recorded the 4 nights and 5 days of the Hungry Ghost Festival in Kobe, Japan in 1982 (Choi 1984).

This study of the Hungry Ghost Festival in Singapore will focus on the relationship between state power and the everyday life practices of the public. This is because the Hungry Ghost Festival underwent various changes over the past decades, and these are largely related to the socio-economic policies adopted by the colonial government and later by the PAP (People’s Action Party) government.1

During colonial Singapore, the British imperial government employed the strategy of “divide and rule” to control its colony. A colonial “plural society” was formed as the major social developments shaped Singapore’s social order (Trocki 2006, p. 34). Singapore started its rural socioeconomic development under colonial rule.

Brenda Yeoh has successfully traced and explained the relationship between the colonial municipal authorities and ordinary inhabitants by using the concepts of power and space. She applied the cultural theory of Michael Foucault and examined the contested use of “power” within the colony. She explained that every single space within the colony, from the verandah to the five-foot way to cemeteries, became a battlefield between various parties. Moreover, she showed that the policies adopted by the municipal authorities were not rigid and could change in response to actions and responses from local groups. The urban built environment in Singapore was not only a reflection of dominant colonizing structures, but also a result of the contesting of power and compromises between the colonizing and colonized groups (Yeoh 2003).

Singapore underwent fundamental changes after attaining independence in 1965. The People’s Action Party, the ruling political party in Singapore, under the rule of the first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, focused on the fragility of the new nation. Singapore lacked a hinterland and faced racialized politics as a “Chinese” island surrounded by a largely “Islamic” archipelago. As a result, the national ideology of survival and pragmatism was adopted, empowering the state to intervene in many socio-economic aspects of society (Lim 1983, pp. 757–58). This was the beginning of the state’s “total design” approach which aimed at promoting a good life and prosperity for its citizens.

A significant change is the transformation of the physical and socio-economic-religious landscapes, given that the state controlled the utilization of land. Physical landscapes and socioeconomic policies underwent enormous changes which refabricated the everyday life of Singaporeans.

The PAP government adopted urban development and landscape planning policies beginning in the 1960s. These initiatives can be divided up into three phases. The first phase was marked by the development of the HDB (Housing & Development Board)2 and the Planning Department. The state aimed to clear slums and build up public housing. Citizens started to move into HDB estates and move out of the villages (kampung). The second phase was laid out in the 1971 Concept Plans, in which the state implemented economic pragmatism as the state ideology and applied this logic in land use. Land acquisition was carried out in the name of patriotism. As a result, various new towns were developed, while farmlands and other rural occupations were phased out. The third phase took shape in the 1991 Concept Plans and its proposal for future landscape planning (Waller 2001, pp. 47–63).

The state polices on land use led to fundamental changes in the everyday life practice of the ordinary people. Chua Beng Huat suggested that massive changes that take place in everyday life are often the amplified results of initiatives taken by political leaders. He argued that the cumulative effects of a series of administrative decisions could transform existing everyday life into a new configuration, a new everyday life. Pragmatism as the government ideology, is pertinent to the everyday life of Singaporeans, especially regarding changes to the lived environment (Chua 1995, pp. 79–100). Singaporean experienced a new lived environment in the new residential communities of the HDB estates.

State intervention not only affected socio-economic activities but also affected the everyday practices of the people. A highly-interventionist state developed in Singapore, which attempted to develop a comprehensive management of social life. Land, housing, employment and even private life were all areas subject to intervention by state power. For example, dialects used by various Chinese communities were prohibited in schools and Chinese Singaporeans are all encouraged to speak Mandarin Chinese as the lingua franca, which helped to build up a homogenous “Chineseness” among the Chinese within the nation state. Lily Kong and Brenda Yeoh, both Singaporean scholars, stated that under state policies, even the religious landscape was sacrificed for urban planning. In many cases, religion activities now have to be held in residential estates (Kong and Yeoh 2003, pp. 75–93). Residential areas and religion activities sometimes share the same physical landscape.

Kenneth Dean has further explained that within religious transnational networks, religious space has been both compressed and extended. He stated that Singapore is a nation-state and all levels of political discourse and action occur at each and every level of lived space, thus space in Singapore has become flattened and highly concentrated. The HDB estates are the example of this homogenization of space, Nonetheless, religious activities transform this space into a ritual sensorial zone (Dean 2015).

The use of space is not completely controlled by state power and the public can and does subvert and transform state planned space into other religious spaces, especially during the Hungry Ghost Festival. Terence Heng argues that although the use of space in Singapore is well planned by the state for particular secular purposes, and ethnic heterogeneity is replaced by a homogeneous Chinesenese, these narratives are not rigid and are challenged by the people during two kinds of religious activity. These are the rituals found on the sides of the road and streets during the Hungry Ghost Festival and also the rituals performed by the spirit mediums in the HDB areas (Heng 2015, 2016). Through engaging in these practices, ordinary Chinese Singaporean subvert and transform the hegemonic narrative and spatial designing presented by the state power.

Terence Heng (Heng 2015, 2016) employs the concept of aesthetic markers, which involve the use of tangible materials to perform an individual’s or collective’s ethnic identities. Aesthetic markers may give a particular space a ‘look’ of ethnic occupation.

In the Hungry Ghost Festival, paper money is burned in rusted incense burners and other sacrifices and food offerings are laid out. These are the transient aesthetic markers which subvert and transform the state planned street into an ethnic and private space, in which the diasporic ethnic identities of the individual will be performed and strengthened during the rites. Terence Heng claims that even though the cultural representations of transient aesthetic markers have to some extent been hybridized and syncretized over generations, nonetheless the identification of ‘Chineseness’ could still be seen during the rituals of the Hungry Ghost Festivals. Here, space which is state-defined was reified into an imaginary ethnized “second space” (Heng 2014, 2015).

In the case of spirit medium performances in private apartments within the HDB, the functionalist policies of the state are once again challenged by the mediums (Tang-ki (童乩)) and their followers. Aesthetic markers, which include the behavior the Tang-ki, their vestments and other ritual tools, subvert and transform the HDB flat into a sacred space. Although this kind of religious practice is not encouraged by the state, it is tolerated as long as the Tang-ki is not receiving any complaints from the other households. This once again shows that state policies are not rigid (Heng 2016).

The rites for the Hungry Ghost Festival and the spiritual medium sessions performed in HBD estates can be regarded as an alternative to the state planned narrative. The participants reinforce their ethnicity during these rites, expressing differences from a unified state imposed identity, while preserving the continuity of their unique cultural identity. This paper argues that Getai, a ritual theater performance, functions in similar ways and takes on considerable agency in structuring the Hungry Ghost festival in Singapore. Thus, Getai can also be analyzed in terms of the contestation and negotiation of power between the state and the public.

3. Date Collection

In term of methodology, previous studies analyzing the Hungry Ghost Festival relied mostly on ethnographic approaches, including participant observation. Information regarding the festivals, such as the number of participants, the configurations of the festival venues, can be observed while participating in the event. Information related to the festival organizers and the participants can also be collected by conducting in-depth interviews.

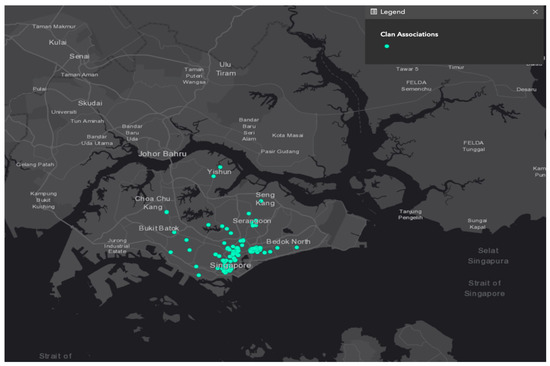

This paper uses data from the Singapore Historical GIS to discuss the vicissitudes of the Hungry Ghost Festival in Singapore (Singapore Historical GIS 2020). The SHGIS displays multiple layers of cultural historical data, particularly the expansion of the HDB blocks that provide shelter for over 80% of Singaporeans from the 1950s onwards. This database also includes the current and previous locations of the Chinese clan associations. (Dean et al. 2019). This information provides an overview of the changes to the Hungry Ghost Festival since the late 19th century.

This research also collected data from newspaper archives. The three major Singaporean Chinese-newspapers, the Shin Min Daily News (Shin Min Daily News 2017) (新明日報), the Lianhe Zaobao (Lianhe Zaobao 2017) (聯合早報) and the Lianhe Wanbao (Lianhe Wanbao 2017) (聯合晚報) publish daily announcements providing the details of Getai every lunar seventh month. This paper collected and analyzed all the announcements published in 2017 to illuminate the status of the Hungry Ghost Festival in contemporary Singapore.

4. Hungry Ghost Festival in Past-Time Singapore

In the past, the Hungry Ghost Festival was celebrated through the laying out of sacrificial food offerings and the preforming of dramas, including puppet shows, wayang (哇揚皮影戲) and other dialect operas. It was an important part of the spiritual life of the Chinese migrants. According to Yen Ching-hwang, Chinese migrants in the 19th century Singapore who spoke the same dialect and came from the same region would group together socially (see also Wang 1981). Each of these dialect groups would have differences in religious worship but the function of these religious activities was basically the same, which was to provide a collective symbolic event to bring all the social members together (Yen 1986, p. 15).

The Hungry Ghost Festival in this period could then be understood as a collective event to reinforce the bonds between the sojourners of different dialect groups in the Straits Settlements. The collective memories and nostalgic sentiments towards their hometowns among the immigrant generations were very strong, especially when they encountered obstacles or difficulties in their new context. According to Le Goff, memory is an essential element of individual or collective identity The social and historical memories of the immigrant Chinese have pushed them to re-evaluate their cultural and religious practices to maintain their sense of cultural continuity (Le Goff 1996, p. 98). This can be clearly demonstrated through the Hungry Ghost Festivals in 19th century Singapore.

The organizers of the Hungry Ghost Festival ceremonies were mainly the dialect organizations. Most of the Chinese came from the rural areas of South China and they tended to preserve most of their religious practices and social customs. The dialect associations would then take up the role to provide religious precession and festival celebrations to the immigrant Chinese. For example, the records of the Ying Ho Association (應和會館), a joint Hakka-Cantonese dialect association, reveal that their religious and social activities were the most important functions of the association in the 19th century. They would offer sacrifices to the wild ghosts during the lunar seventh month on behalf of their migrant communities (Yen 1986, pp. 45–46).

Apart from dialect organizations, clan organizations also provided celebrations during the Hungry Ghost Festival. Chinese lineage as a social organization has progressed into a cultural network that encompassed members scattered throughout the diaspora. The Hungry Ghost Festival was an event to enhance the spirit of solidarity among these community members. So this festival had the same social function as the other seasonal festivals did in 19th century, which was to provide a site for the social gathering of members so as to promote a sense of solidarity.

According to the data on clan organizations found in Singapore Historical GIS, the clan organizations in the 19th century were mainly located along the Singapore River, which is the China Town area and the Telok Ayer area in today’s Singapore. The SHGIS structures, manages and visualizes the data of Chinese clan associations through space and time. Many of them also were located in the Tanjong Pagar area and Bugis area (Figure 1). It can be extrapolated that many Hungry Ghost Festival Ceremonies were celebrated in these areas in that period of time.

Figure 1.

The Distribution of the Clan Organizations in Singapore (Singapore Historical GIS 2020).

During the colonial era, Chinese customs and traditions became a major source of conflict between the Chinese community and the British colonial authorities. The colonial government tried to control the Chinese community with laws and thus force through changes in Chinese customs and traditions. The clash between the two parties hinged on the issue of noise, safety and hygiene.

Brenda Yeoh had recorded the conflict regarding the use of verandahs and also the five-foot ways along the sides of public streets between the Chinese community and the British Municipal authorities. This conflict reflected the larger culture clash in a colonial context, for public space is the common ground where civility and collective sense of what may be called ‘publicness’ are developed and expressed (Yeoh 2003, p. 245).

During the Hungry Ghost Festival, Chinese people would burn paper money, display sacrifices to the dead, and hold street-wayang. However, due to the passing of the Municipal Ordinance IX of 1887, the municipal authorities were empowered to remove any obstruction along verandahs, arcades or streets which either hindered the work of garbage collection or caused inconvenience to the passage of the public. In this way, the Chinese community was restricted in their use of ‘public space’ to celebrate their traditional festivals. This led to discontentment towards the colonial authorities. The ‘Verandah Riot’ broke out between the municipal authorities and the Chinese community (Yeoh 2003, pp. 250–53). Although the protest of the Chinese could not change the situation, the question regarding the use of verandahs continued into the following decades.

The nature of public space and how it should be utilized continued to be contested in the daily arena. The use of space was a strongly contested terrain on a daily basis between the municipal authorities and the ordinary people. As Brenda Yeoh pointed out, the use and occupation of the urban environment was an arena of conflict between public definition and private use, between European ideals and Asian reality, and between the power of authorities and the purpose of those who lived within the city (Yeoh 2003, p. 271). The collective ceremonies found during the Hungry Ghost Festival was just one facet of the contestation and negotiation between the colonial government and the Chinese community.

5. Hungry Ghost Festival in Contemporary Singapore—The Case of Getai in 2017

Getai does not have a very long history in Singapore. It emerged roughly around the 1940s, during the Japanese occupation (Wang 2006, pp. 1–4). According to the research of Chan Kwok-bun and Yung Sai-shing, the emergence of Getai had nothing to do with the Hungry Ghost Festival. It was instead an amusement activity found in the amusement parks. It began as a song performance and later added in dancing, drama and acrobatics. It reached its heyday in the 1950s due to financial support from Singaporean merchants (Chan and Yung 2005, pp. 120–24).

Yet, this amusement activity has been combined with religious activities and has become an indispensable element of the current Hungry Ghost Festival in Singapore. Hundreds of Getai are performed across Singapore Island during the Lunar Seventh Month, most of them held in the HDB (Housing Development Block) estates. Many residents enjoy the performances over the whole lunar seventh month, as it became a daily amusement for them. The popularity of Getai during the Hungry Ghost Month can be proved by looking at the number of Getai performance.

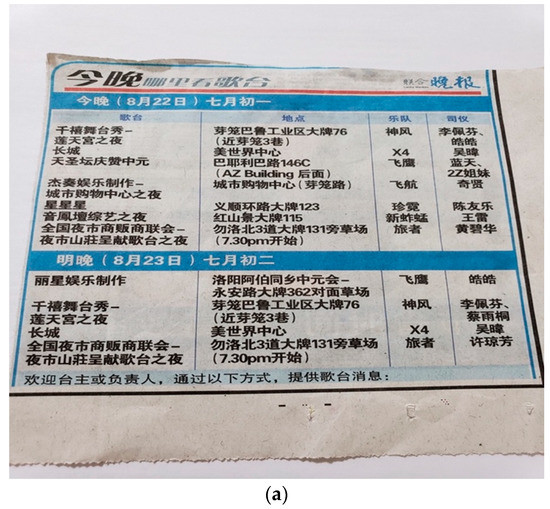

During the whole lunar seventh month, the three major Chinese newspapers in Singapore, which are the Shin Min Daily News (新明日報), the Lianhe Zaobao (聯合早報) and the Lianhe Wanbao (聯合晚報) publish daily announcements providing the details of Getai. The details include the names of the performers, the location, the live band and also the hosts of the Getai. The newspapers welcome the Getai organizers (Taizhu台主) to provide information on their Getai to the newspapers so that they can help spread the news to their readers (Figure 2). Since newspapers did not send journalists to investigate different Getai performances, they had to rely on the reports from the organizers and there might be some Getai performances which were not reported in the newspapers.

Figure 2.

An Announcement of Getai Performances (Lianhe Wanbao 2017) (a) with English translation (b).

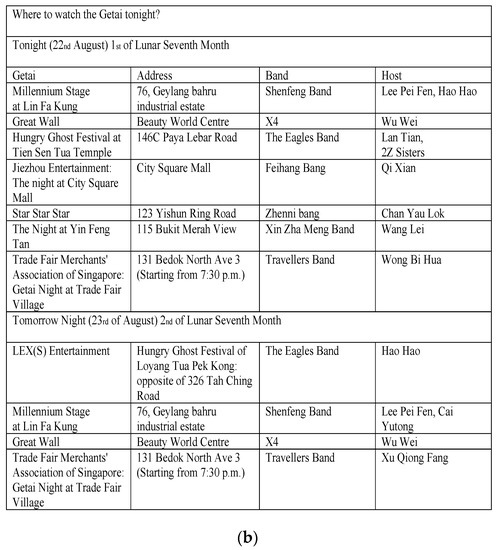

According to the newspaper announcements and reports collected from the 21st of August (30th day of the Lunar Sixth Month) to the 19th of September (29th day of the Lunar Seventh Month) in 2017, 307 events related to the Hungry Ghost Festival were recorded. A total of 284 of them were Getai-related events and only 23 of them were non-Getai related events (Figure 3). Many individual practices could also be considered as activities of the Hungry Ghost Festival, but it is difficult to record them all. Moreover, many collective ceremonies organized by the temples or social communities were not recorded by the newspapers. On the other hand, the organizers of Getai were allowed to report their activities to the newspaper and many Getai performers are actually local celebrities in Singapore. Their news would then be reported in the Entertainment section of the newspapers. This is the reason why the reports about Getai greatly outnumber the other Hungry Ghost Festival related activities.

Figure 3.

Hungry Ghost Festival activities recorded in Chinese newspapers in 2017.

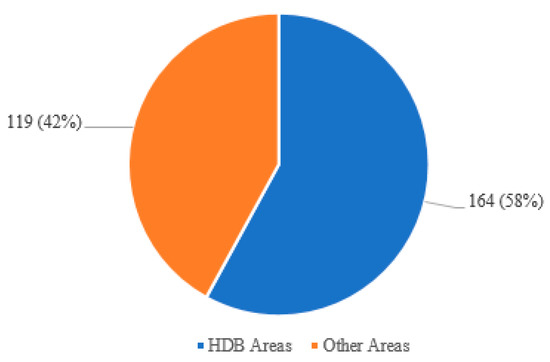

Among the 284 Getai performances, 165 of them were located in HDB areas while 119 of them are located in other areas like industrial areas or temples or even in different hawker centers. This means more than half of the Getai were performed in HDB areas (Figure 4). However, it is difficult to identify the exact location of the Getai and to group them into different categories. Firstly, all the names recorded in the newspaper are in Chinese, but some of the names are just transliterations from English names.3 Moreover, many addresses published in the newspaper did not provide the postal code, which made it difficult to locate them on the map. Second, many addresses found in the newspaper are not the exact location of the Getai but just show the name of the street.4 Third, many Getai in hawker centers or community centers are actually located inside the greater HDB area. So in Figure 4, only the Getai in HDB area are identified and the rest are all classified under the category of ‘Other Areas’.

Figure 4.

Getai in the Housing & Development Board (HDB) areas.

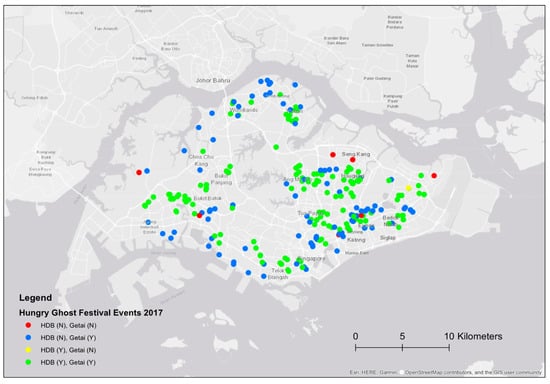

In order to make a clear picture of the distribution of the location of the Getai, a map was drawn using GIS as shown in Figure 5. According to the map, it is clearly shown that many Getai were performed in the HDB areas in both the East and West side of Singapore. There was a high concentration of Getai in Jurong West, Ang Mo Kio, Tao Payoh, Hougang and Yishun. Getai could also be found in non-HDB areas, mainly in Sembawang, Woodlands and also along the West Coast area.

Figure 5.

Distribution of Getai in 2017.

Getai shows are usually performed in open-air venues in HDB estates. The open areas in HDB are secondspaces (Soja 1996) designed and regulated by the state. These open spaces were indeed meant to have the kind of liveliness and spontaneity that made the back lanes so attractive to the early HDB settlers (Seng 2012). However, stringent regulations are applied over all ‘misbehaviors’ (spitting, illegal parking and littering), which reinforces state control over these open spaces.

All this, however, loses its efficacy during the Lunar Seventh month. Getai live stages are pervasive across the open space in HDB estates. The space is no longer simply for regulated leisure use. Instead, it becomes a temporary religious and entertainment center. Getai entertainment is popular for the ordinary people, as well as the wandering spirits. Getai singers pray to the wandering ghosts before every gig. The first row of the seats is also reserved for the ghosts to enjoy the performances. Performers sing both traditional songs in dialect, together with English and Mandarin pop music. The boisterous performance ends after 10:00 p.m., at which time the open area is cleaned up by the town council.

This open area becomes temporarily re-purposed beyond what was intended by the state. Getai shows convert the space into a carnivalesque space in which the rules of use and conduct are made ambiguous and porous. Enjoying the Getai performance is part of the daily activities of Chinese Singaporean in every lunar seventh month, but at the same time undermines the narratives of everyday lives created by the state. It can be concluded that the Getai, as an amusement activity, has already deeply intertwined and co-exists with the everyday life activity of the ordinary people in residential areas and also in industrial and mixed-use areas.

This kind of coexistence can be further explained by looking at the organizers of the Getai. According to news report, 48 out of 284 Getai performances in 2017 were organized by religion organizations, such as temple committees. A total of 35 of them were organized by private companies as part of a banquet to celebrate the Hungry Ghost Festival with the company staff. From this perspective, it can be shown that Getai in Singapore is no long either an amusement activity or a religious activity, it is a combination of both kinds of events.

This kind of coexistence can be seen as a result of the state policy towards the use of space. According to Terence Heng, areas for different activities are carefully planned and defined. The state takes it upon itself to reshape and gentrify sectors of Singapore into its vision of what it means to be Chinese (Heng 2016, p. 58). However, Heng mentioned that these policies have not been implemented completely. He vividly used images and the concept of aesthetic markers to explain how people try to compromise with state power and at the same time maintain their own cultural identity (Heng 2015, pp. 58–61).

The case of Getai could lend further support to his ideas because the use of dialect in the Getai performance is also subverting state planned ethnic homogenization. Chinese Singaporeans are roughly defined into five main linguistics groups, Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka and Hainanese, according to the dialects they spoke. There was a clear residential segregation of dialect groups in pre-war Singapore. The everyday life of the Chinese was also restricted to their own dialect community (Yamashita 1986). In the mid-20th century, Chinese Singaporeans still spoke dialect most frequently in their daily life (Census of Population 1981). However, the PAP state enforced Mandarin as the compulsory common ‘mother-tongue’ language for all ethnic Chinese and banned the use of dialect in all radio and television programs since the late 1970s (Clammer 1985). The intention was to forge a new cultural identity and a single Chinese community by means of the state language policy. In theory, the Chinese in Singapore would no longer be Hokkien Singaporean or Cantonese Singaporean but a unified kind of Chinese Singaporeans, all using Mandarin as their only ‘mother tongue’.

Despite the eradication of dialect use from official discourse, dialect is still used regularly among the older Chinese Singaporeans and the working classes (Chua 2003). Languages play an essential role in defining self-identity. In Chinese communities, the use of dialect also helped to identify the ethnicity of an individual. Getai show offers an opportunity, despite its fleeting temporality, for these dialect speakers to share their regional ethnic identification, mainly the Hokkien identity. In the Getai performances, Hokkien is widely used. From the newspaper reports, it can be seen that most of the singers were singing in Hokkien with some Mandarin or Cantonese songs. Many singers from other Hokkien speaking areas, like Taiwan or Malaysia, were even invited to perform Getai.5 Moreover, all the hosts in Getai also spoke in Hokkien or other dialects. So Getai is a temporary stage to revert to earlier forms of ethnic heterogeneity which is different from state planned ethnic homogeneity. The ethnic identification is reignited in that particular time (Lunar Seventh Month) and space (Getai performance at HDB).

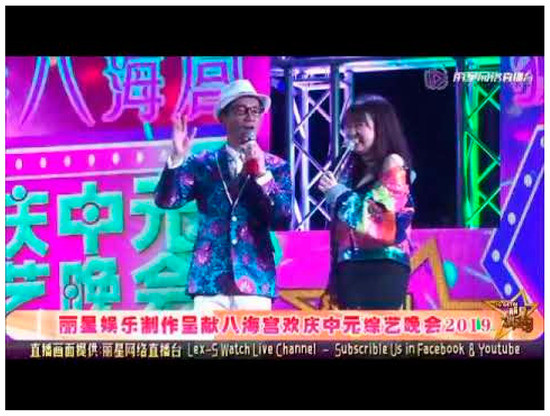

Furthermore, in recent years, some Getai production companies even generated facebook livestream broadcasts for their audiences. LEX(S) Entertainment Production (麗聲娛樂製作), the leading company in Getai Industry, creates Facebook and YouTube channel for the live Getai performances (Figure 6). This new media platform has extended the ethnic space for the Chinese Singaporeans because it provides an opportunity for other dialect speaking communities from China or Taiwan to participate in the same event.

Figure 6.

A live Getai performance on YouTube (Just Music只是宣傳 2019). The title of the show is LEX(S) Entertainment Production, The Hungry Ghost festival at Ba Hai Gong 2019.

6. Conclusions

This paper examines how Getai performances subvert and transform state planned space into a temporary ethnic heterogeneous landscape, in which the everyday life practices become an important component. Getai, being a temporary stage, reverts to the earlier forms of ethnic heterogeneity of the Chinese Singaporean, which is different from the state planned Chinese homogenous identity. The underlying forces behind the continued popularity of the Hungry Ghost Festival are based in the hybridity of everyday life activity and religious activity. These forces have reshaped the Hungry Ghost Festival into a new format which is widely accepted and welcomed in Singapore.

By researching Getai performances in Singapore, I want to develop a new perspective to look at how the traditional Hungry Ghost Festival transformed in an expanding urban context. This paper can serve as a foundation for future research to analyze the contesting of power and the compromises over the use of space between the state and various Chinese communities. This project seeks to trace and identify the changing historical features of the inter-relationships between space, the state, power and the people by using the Hungry Ghost Festival as an analytic category. The cultural identity of the Chinese communities underwent changes under PAP authority. The study of the Hungry Ghost Festival and Getai performances allows a new perspective on the clash between state-promoted homogenized “Chineseness” and the heterogeneity of individual and dialect group identities. Further research is needed to examine these issues in depth.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Thank you for the support and help to Kenneth Dean, Yan Yingwei, and Xue Yiran.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Census of Population 1980, Singapore. Release no. 2, Demographic Characteristics. 1981. Singapore: Department of Statistics.

- Chan, Kwok-bun, and Sai-shing Yung. 2005. Chinese Entertainment, Ethnicity, and Pleasure. Visual Anthropology 18: 120–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Qian 陳蒨. 2015. Chao ji yu Lan Sheng Hui: Fei Wuzhi Wenhua Yichan, jiti Huiyi yu Shenfen Rentong 潮籍盂蘭勝會:非物質文化遺產, 集體回憶與身份認同 (Chaozhou Yulan Ghost Festival: Intangible Cultural Heritage). Hong Kong: Chung Hwa Book Company (Hong Kong) Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, Wei Yi. 2012. Theravadizing the Ghost Festival in Taiwan. Contemporary Buddhism 13: 281–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Chi Cheung. 1984. The Chinese “Yuen Lan” Ghost Festival in Japan: A Kobe case study, August 31–4 September 1982. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch 24: 230–63. Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/23902775 (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Chua, Beng Huat. 1995. Communitarian Ideology and Democracy in Singapore. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415164656. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, Beng Huat. 2003. Life Is Not Complete without Shopping: Consumption Culture in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore University Press. ISBN 9789971692728. [Google Scholar]

- Clammer, John. 1985. Singapore: Ideology, Society, Culture. Singapore: Chopmen Publishers. ISBN 9789971681180. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, Kenneth. 2015. Parallel Universe: The Chinese Temples of Singapore. In Handbook of Asian Cities and Religion. Edited by Peter van der Veer. Berkeley: U. C. California Press, pp. 257–89. ISBN 9780520281226. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, Kenneth, Xue Yiran, Hue Guan Thye, and Yan Yingwei. 2019. SHGIS and SBDB—Two ongoing database and mapping projects related to Singaporean cultural history. A Newsletter of the Asia Research Institute 44: 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- DeBernardi, Jean. 1984. The Hungry Ghosts Festival: A Convergence of Religion and Politics in the Chinese Community of Penang, Malaysia. Southeast Asian Journal of Social Science 12: 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Tongju 刁統菊, and Rong Zhao 趙容. 2015. A study of the Zhongyuan Festival in Shandong province 山東中元節節俗述略. Journal of Yunnan Minzu University (Social Sciences) 雲南民族大學學報 (哲學社会科學版) 32: 60–67. Available online: http://gb.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?filename=YNZZ201503011&dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2015 (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Heng, Terence. 2014. Hungry ghosts in urban spaces: A visual study of aesthetic markers and material anchoring. Visual Communication 13: 147–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, Terence. 2015. An appropriation of ashes: Transient aesthetic markers and spiritual place—Making as performances of alternative ethnic identities. Sociological Review 63: 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, Terence. 2016. Making “Unofficial” Sacred Space: Spirit Mediums and House Temples in Singapore. Geographical Review 106: 215–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just Music 只是宣傳. 2019. Xinjiapo getai zongyi wanhui 01.08.2019 (Nongli qiyue chuyi)—Wanglei, Mingzhu jiemei (shipin qu zhi Lixing Wangluo Zhibo tqi). Youtube. August 2. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=APgki7FV-4Q (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Karashima, Seishi. 2013. The Meaning of Yulanpen 盂蘭盆—“Rice Bowl” on Pravarana Day. Annual Report of The International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University for Academic Year 2012 XVI: 289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Lily, and Brenda S. A. Yeoh. 2003. Politics of Landscapes in Singapore: Constructions of “Nation”. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 081562980X. [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff, Jacques. 1996. History and Memory. Translated by S. Rendall, and E. Claman. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231075909. [Google Scholar]

- Lianhe Wanbao. 2017. Jinwan nali kan getai 今晚哪裡看歌台 (where to watch the Getai Tonight). Lianhe Wanbao (聯合晚報), August 21–September 19. [Google Scholar]

- Lianhe Zaobao. 2017. Jinwan nali kan getai 今晚哪裡看歌台 (where to watch the Getai Tonight). Lianhe Zaobao (聯合早報), August 21–September 19. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Linda. 1983. Singapore’s success: The myth of the free market economy. Asian Survey 23: 752–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, E. 2012. Politics of greening: Spatial constructions of the public in Singapore. In Non West Modernist Past: Architecture and Modernities. Edited by S. W. Lim and J.-H. Chang. London: World Scientific, pp. 143–59. ISBN 9789814365949. [Google Scholar]

- Shin Min Daily News. 2017. Jinwan nali kan getai 今晚哪裡看歌台 (where to watch the Getai Tonight). Shin Min Daily News (新明日報), August 21–September 19. [Google Scholar]

- Singapore Historical GIS. 2020. Available online: http://shgis.nus.edu.sg/ (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Soja, E. W. 1996. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 9781557866745. [Google Scholar]

- Teiser, Stephen F. 1998. The Ghost Festival in Medieval China. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691026770. [Google Scholar]

- Trocki, Carl. 2006. Singapore: Wealth, Power, and the Culture of Control. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415263867. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, Edmund. 2001. Landscape Planning in Singapore. Singapore: Singapore University Press. ISBN 9971692384. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guungwu. 1981. Community and Nation: Essays on Southeast Asia and the Chinese. Singapore: Heinemann Educational Books (Asia) LTD. ISBN 9971640260. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Zhenchun 王振春. 2006. Xinjiapo Getai Shihua 新加坡歌台史話 (The history of Singapore’s Getai). Singapore: The Youth Book Co. ISBN 9810565038. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Arthur P. 1978. Gods, Ghosts, and Ancestors. In Studies in Chinese Society. Edited by Arthur P. Wolf. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 131–82. ISBN 0804710074. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, Kiyomi. 1986. The Residential Segregation of Chinese Dialect Groups in Singapore: With Focus on the Period before ca. 1970. Geographical Review of Japan 59: 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Ching-hwang. 1986. A Social History of the Chinese in Singapore and Malaya 1800–1911. Singapore: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195826663. [Google Scholar]

- Yeoh, Brenda S. A. 2003. Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations in the Urban Built Environment. Singapore: NUS Press, Originally published by Oxford University Press in 1996. ISBN 978-9971-69-268-1. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The People’s Action Party has been the ruling political party of Singapore since 1959. |

| 2 | The Housing & Development Board (HDB) is the statutory board responsible for public housing in Singapore. The HDB flats currently spell home for over 80% of Singapore’s resident population. |

| 3 | For example, Jln Rajah is translated into 惹蘭拉惹 in Chinese. |

| 4 | For example, an address of Getai was shown as 甘榜安拔, 在裕盛路附近一帶 (Kampong Ampat, near Yu Sheng Lu) in the newspaper only (Shin Min Daily News 2017). |

| 5 | Taiwanese singer Xie Yijun (謝宜君) was invited to perform in a Getai in Jurong East on 12th September 2017. Jinwan nali kan getai 今晚哪裡看歌台 (where to watch the Getai Tonight), (Lianhe Wanbao 2017). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).