Abstract

This study focuses on the contemporary use of two well-known Sámi offering sites in Alta, Finnmark, Norway. Today, these are hiking destinations and sightseeing points for both the Sámi and the non-Sámi local population, as well as a few non-local visitors. Many of these visitors leave objects at the sites, such as parts of recently slaughtered reindeer, clothing, coins, toys, sweet wrappers and toilet paper. This indicates that visitors have different levels of knowledge about and reverence for the traditional significance of these places. Through repeated surveys over several years, we also observed a certain development and change in the number and character of these depositions, as well as a variation in depositions between different sites. A series of interviews with various users and key stakeholders were performed to clarify the reasons for these changing practices, as well as what individuals and groups visit these sites, their motivation for doing so and for leaving specific objects, and what potential conflict of interest there is between different users. Furthermore, we surveyed what information has been available to the public about these sites and their significance in Sámi religion and cultural history over time. The results show that a diverse group of individuals visit the sites for a variety of reasons, and that there are contrasting views on their use, even among different Sámi stakeholders. While it is difficult to limit the knowledge and use of these places because they are already well known, more information about old Sámi ritual practices and appropriate behaviour at such sites may mediate latent conflicts and promote a better understanding of the importance of offering sites in both past and present Sámi societies.

1. Introduction

There have been many ways of relating to old Sámi offering sites, and there have been many ways of safeguarding them. In Norway, cultural heritage sites are generally recorded and mapped for land planning purposes and preservation. However, there are Sámi traditions for secrecy around certain offering sites, and a traumatic history of irreverence towards Sámi ritual sites and practices has contributed further to secrecy about old graves and offering sites. To some extent, Sámi cultural heritage authorities in Norway have maintained that offering sites that are automatically protected by law should be recorded only in password-protected databases (Fossum and Norberg 2012, pp. 19–23). The need to protect them in this way relates both to their general status as cultural heritage and their more specific and transcendent symbolic value as markers of the ethnic religion of the Sámi indigenous population in northern Fennoscandia. The latter has socio-political significance today because Sámi religion and rituals were systematically eradicated by missionary activity and other assimilation policies, at least from the 17th century onwards. The cultural and human consequences still affect Sámi communities and individuals today.

Some Sámi offering sites, however, are too well known locally and regionally to be protected by lack of mention in databases or cultural heritage guides. They represent the old Sámi sacred landscape but also the local landscape, as this is used and conceptualised by a variety of people. The past significance of the offering sites may ring through into various modern contexts, although in part as a rather diffuse idea about their meaning.

Instead of a profound spiritual meaning, the sites sometimes end up as focal points for what might be considered another general form of “spirituality” in an increasingly secularist Norway—the fascination with hiking. Hiking and skiing and, more generally, “being in nature” became national symbols of Norwegian identity during the late 19th and 20th century (Hesjedal 2004; Ween and Abram 2012). Hikes are often undertaken to reach a destination, whether a mountain peak, a cabin or some useful activity like fishing or berry and mushroom picking. The hikes may also aim for a landmark, and conspicuous Sámi offering stones are among such destinations.

The variation in knowledge among people using Sámi offering sites as hiking destinations about their significance in Sámi culture is given a material expression in a variety of depositions. What is left at the sites includes objects close to traditional Sámi offerings as well as things more similar to rubbish, at least at first glance. This is problematic both from the viewpoint of some Sámi individuals and groups and in terms of the Norwegian cultural heritage legislation. The law forbids destruction and vandalism but also “undue disfigurement”, which can cover the littering of heritage sites (Cultural Heritage Act §3-1). Sámi sites with place-specific traditions or archaeological remains from 1917 or older are automatically protected (§4-2).

In this article, we look into the latent conflicts related to the varied contemporary use of two old Sámi offering sites in Alta, Áhkku (“the Old Woman”) by the sea close to the town, and Fállegeađgi (“the Falcon Stone”) on the inland plains (Figure 1). The study is important to understand the interaction with these sites and what consequences diverging use and understanding of their sacredness may have for the dynamics of the multicultural community in Alta today. Through field observations and semi-structured interviews, we explore who exactly visits the sites and leaves the different things found there, what knowledge various groups have about the original Sámi use of the sites, their own attitude to these today, and how any conflicting use can be mediated at these well-known and easily accessible sacred sites.

Figure 1.

Satellite photo of Alta, Finnmark, northern Norway, with the sites mentioned in the text. Ill.: Marte Spangen. Photo: norgeskart.no.

2. Sámi Offering Sites and Rituals

Sámi offering and sacred sites, called sieidi (plural sieddit) in North Sámi, come in many shapes, but large blocks, sometimes split by ice or lightning, or other rock formations that stand out in the landscape are frequent among known sites. Contemporary overviews of sites in use were gathered by priests and missionaries in Sámi areas in the 17th and 18th centuries, with the main purpose of revealing and destroying them (e.g., Niurenius [1640] 1905; Olsen [1715] 1934). This knowledge has later been complemented with ethnographic and archaeological surveys and investigations, listing numerous offering sites (e.g., Qvigstad 1926; Hallström 1932; Manker 1957; Äikäs 2015).

The sources also describe rituals related to Sámi offerings, which were performed as a naturally integrated part of everyday life, life transitions and the general worldview. This included, but were not limited to, offerings of various animals; by families near the living areas, as part of hunting or fishing practices, and at particular offering sites as ceremonies for larger parts of the communities (e.g., Olsen [1715] 1934; Randulf [1723] 1903; Mebius 1968, 1972; Äikäs et al. 2009). Unfortunately, many of the early historical sources tend to copy each other without clarifying whether the described rituals are in fact performed in the local area where the author resided. This is a relevant source-critical issue, since the geographical area of Sámi settlement, Sápmi, covers large areas of Fennoscandia and incorporates a multiplicity of Sámi cultural expressions, subsistence strategies, and languages. More recent scholarship emphasises the importance of only using information specific to the time and place of any given historical study of religion (Rydving 1995a).

While the conspicuous offerings of animals at Sámi offering sites were heavily reduced by the intensified activity by Christian missionaries in the 17th and 18th century, they did not stop entirely (Qvigstad 1926; Äikäs 2015; Salmi et al. 2015, 2018). Furthermore, other types of offerings, like foodstuff, alcohol, tobacco, coins and small pieces of jewellery continued at many sites into the 20th century, and in some places until the present day. Notably, offering sites have also had different biographies, being established and falling into disuse at different points in time (Serning 1956; Mebius 1972; Äikäs and Salmi 2013; Äikäs and Spangen 2016). Thus, it is important to understand Sámi offering sites not only as a uniform element of Sámi pre-Christian ritual but as singular entities featuring diverse traditions depending on the history and context of the specific site (Mathisen 2010).

3. Áhkku—Grandma/The Old Lady/Woman

Áhkku is a distinct rock formation by the sea on the Komsa promontory in Alta (Figure 2). The Komsa name derives from a Norwegian name previously used for the small mountain at the promontory, “Kongshavnfjell”. The rock formation of Áhkku is known to have been a Sámi site of reverence, a sieidi.

Figure 2.

The rock formation constituting the sieidi Áhkku (Photo: T. Äikäs).

Geologist and mountain climber Baltazar Mathias Keilhau travelled through Finnmark in 1827. He comments on several interesting places, among them the two sieiddit discussed in this article. About Áhkku, he says that they sailed close by this rock of a vague human resemblance. The Sámi had worshipped it and brought it offerings in the past, so that reindeer antlers and fish bones were still visible in front of the rock (Keilhau 1831, p. 181). Linguist and ethnographer Just K. Qvigstad, who worked extensively with issues of Sámi culture, described the site in the early 20th century. He notes that the Sámi would try to trick those travelling past in boats into greeting the rock (Qvigstad 1926, p. 341). As late as in the mid-20th century, people were still respectful towards the site, and especially a cave behind the rock that was thought to be where offerings were placed. A man who dared to enter the cave was said to have become paralysed from the waist down (Sveen 2003, p. 52).

The name Áhkku can be understood in several ways and has associations to the present use as “grandmother”, but also “old woman” and “goddess”, in the sense that it is frequently used as a name for holy sites. Female denominations are also part of the names of historically recorded pre-Christian Sámi goddesses such as Máderáhkká, Sáráhkká, Juksáhkká, and Uksáhkká, although áhkka refers to “wife” rather than “grandmother”. Knowledge of the latter goddesses is only recorded in areas further south, and they were not known in Finnmark in the 18th century (Randulf [1723] 1903; Kildal [1730] 1945; Högström [1747] 1980; Leem [1767] 1975, p. 421; cf. Rydving 1995b, pp. 62, 70). However, it is likely that other female deities were well known even here, considering the use of such terms for known offering sites.

The Norwegian name of the site is “Seidekjerringa”, where seide is a Norwegianisation of the North Sámi word sieidi. The Norwegian word kjerringa can mean both “hag” and “woman”, but in the local dialect is more likely to refer to “woman” (Olsen 2017a, footnote 1). The name may still convey a certain derogative connotation, especially considering persistent ideas about the Sámi as untrustworthy sorcerers (Spangen 2016, pp. 226–27).

The rock is situated close to a residential area on Amtmannsnes near Alta town centre and less than a 1-km walk from the nearest car park on a path starting on a small beach often used by the local population. The rock is currently a relatively popular destination for small hikes, as it does not take too long and is manageable even for young children, despite going through somewhat rocky terrain.

The sieidi itself consists of a 7–8-metre-high rock formation with cracks and platforms. Today it is surrounded by birch trees so has limited visibility. The area of interaction with the sieidi also seems to be restricted close to the stone due to the vegetation and the rocky terrain by the shoreline.

4. Fállegeađgi—The Falcon Stone

The Fállegeađgi rock formation is situated on the northern side of the River Falkelva on a plateau where it can be seen from a long distance. It is relatively accessible by a 9-km walk from the closest road, but, in summertime, the crossing of bogs and small rivers make the hike more demanding than that to Áhkku. In winter, it can be reached on skis. The sieidi consists of three large boulders, one of which is in an upright position (Figure 3). One of the stones has split in two with a narrow crevice between the halves. It is situated on an ancient migration route for reindeer, initially followed by wild reindeer until they became extinct in the 18th‒19th century, and subsequently used for reindeer herds by several Sámi siidas (communities).

Figure 3.

The boulders constituting the sieidi Fállegeađgi. (Photo: T. Äikäs).

Keilhau (1831, p. 189) (see above) travelled past the Falcon Stone, but he only briefly describes its natural shape and mentions no offerings or rituals related to this stone in particular. Qvigstad, however, reports findings of recent offerings by the stone in the early 20th century: a boy passed it in October 1904 and noted many bones and antlers in the cracks of and below the rocks, as well as the backs and sides of two reindeer calves, their flesh still fresh. Furthermore, a student reported a large amount of old reindeer antlers and a recently slaughtered reindeer calf in the crack in the rock in July 1924. He had been told by locals that some of the Mountain Sámi still made offerings to the stone (Qvigstad 1926, p. 342).

Qvigstad (1926, p. 342) also recounts several local legends relating to this sieidi. A Sámi called Stuora-Piera (Big Peter) used to sacrifice to the sieidi as he passed by with his reindeer herd in the early 20th century. One year, he failed to do so, and many of the reindeer broke out of the herd and ran south into a swamp on a nearby headland where they died.

Another tale of caution concerned the Sámi man Garra-Rastus, who once, in the mid-19th century, took a reindeer antler from the sieidi and made a spoon from it. When he reached the nearby mountain station, Joatkajávri, and let go of his draft reindeer, they ran away as if pursued by wolves, although there were no dangers to be seen. Only with great difficulty did he manage to get them back. This was considered a punishment for taking the antler (Qvigstad 1926, pp. 342, 347).

Also in the 19th century, some mountain Sámi travelling to Djupvik in the Altafjord stopped at the sieidi for their reindeer to graze. One of the travellers addressed the sieidi mockingly: “I would like to know if you have gnawed any reindeer bones this year.” When they left, the best draft animal was found to be gone. They searched near and far without finding it. Later that autumn, they travelled back past the same place and found the bones of the lost reindeer right next to the stone. The sieidi would not stand for any insults (Qvigstad 1926, p. 342). Observations in recent years testify to a continued tradition of (parts of) reindeer being deposited at the site.

5. Observations at the Offering Sites

The authors of this article have visited the offering sites in question once and twice respectively, in 2017 and 2019. We have also benefitted from observations made by Prof. Kjell Olsen from UiT—the Arctic University of Norway, Alta campus, concerning the amount and complexity of the traces people have left when visiting Áhkku, as he visited the site every year from 2000 to 2015. For practical and ethical reasons, the archaeological investigations for this study have been limited to observations of the objects left on the site, with no excavations for older material or removal of deposited material. On our visit in 2017, we photographed all the finds that were visible at Áhkku and Fállegeađgi, which we deemed to be an ethically sound way of gathering evidence for this study without interfering with the practice or the objects as such. Only photos of generic objects with little to identify any particular individual visitor are published here (see below). Based on the photographic documentation, we have divided the finds into different operational categories, which seem to represent different interactions with the sites.

The finds at Áhkku can be divided into the following categories: children’s toys, natural objects, hunting- and fishing-related objects, food or drink, and ‘pocket holdings’ or accessories. Children’s visits are testified to by small plastic toys, a toy car, a small soft toy, a Pez sweet dispenser, a toy brush, a trading card, a toy ball and two children’s bracelets. Not all these objects necessarily indicate visits by children as they could have been left by adults too. The next category, natural objects, includes shells, an amethyst, small stones, a reindeer antler, a rose and altogether four bundles of flowers and other plants. Hunting- and fishing-related objects consisted of a fishing rod, a lure, a small net and ammunition shells. There are relatively few finds related to consuming food or drink. In 2017, only three bottles and cans were found and no food items. However, food was observed here in earlier years, including smoked fish, crispbread with spread and a tomato (Olsen 2020). The last group is somewhat hard to define but covers such objects that could easily be carried around and end up as a random offering. We have named this group of finds ’pocket holdings’, and it comprises accessories that people might have worn while visiting the sieidi. The pocket holdings include small coins, a lipstick, a pen, a colour pencil, a small clothespin, a reflector, a pair of bracelets, a lighter, a headband and a hair bobble, as well as accessories such as a sock, sunglasses, an advertising cap and a fleece jacket.

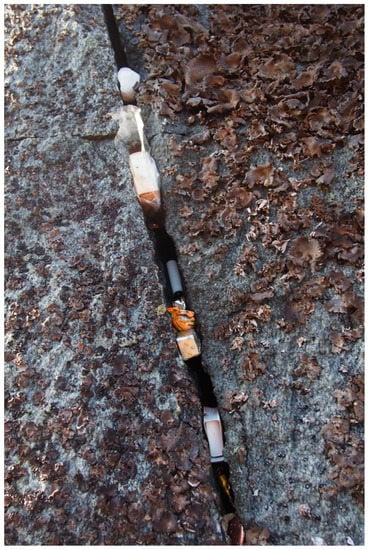

The finds at Fállegeađgi seem to indicate a somewhat different kind of interaction with the sieidi. Children’s toys are missing apart from two marbles, whereas antlers are more numerous here. Most of the finds at Fállegeađgi are situated in a crevice between two big stones. The crevice is almost filled with antlers (Figure 4), three of them with engravings personalising them. Together with the antlers, however, fishing gear and pieces of clothing have also been thrown or placed in the crevice. In addition to antlers, there are also vertebral bones in the crevice and a selection of other bones on the ground.

Figure 4.

Reindeer skull and other objects deposited in the crevice of the Fállegeađgi sieidi stone. (Photo: T. Äikäs).

The finds by the bigger stone are fewer and more heterogenous. Some of them seem to be random leftovers from a hiking trip, like a Coke can on the ground and more deliberately positioned sweets, a matchbox, biscuit wrappers, a biscuit and coins in the cracks of the stone (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Small objects shoved into a crack in the Fállegeađgi sieidi stone.

Observations at Áhkku over 15 years clearly indicate some changes in the type and amount of depositions at the sites. Notably, there was a distinct increase in depositions in 2013 (Olsen 2019a). On the other hand, a distinct decrease in depositions was noted here in 2019 compared to 2017, suggesting that someone found it necessary to clear away some of the objects previously present. One informant also noted this reduction in depositions in 2018 (Sara 2019). It has not been possible to establish who this might have been, when the clearing happened, and whether or not it has been a recurring phenomenon.

6. Users of the Offering Sites Today

To investigate who visits the offering sites today and for what purpose, as well as various opinions on their use and the consequent material assemblages, we contacted various people in Alta with these questions. We eventually encountered eight individuals whom we considered to represent key stakeholders or to be prime sources of information about the use of and knowledge about the offering sites. This was based on our preliminary understanding of who visits the sites and has an opinion on their use. Semi-structured interviews were performed in person or over the phone with a Sámi reindeer herder who has designated pastures close to the Fállegeađgi sieidi (Aslak J. Eira); a member of the Alta-based coastal Sámi interest group Gula (Dagrun Sarak Sara); the head of tourist information in Alta (Marianne Knutsen); an experienced tourist guide and bus driver based in Alta (Jonathan Matte); two school teachers who have brought schoolchildren to the sites (Martin Nordby and Trond A. Olsen); a long-time employee at Alta Museum (Hans Christian Søborg), and the author of the hiking guide book Altaturer (Ottem 2012). All the interviewees gave their consent to participate in the study with their full names and all were given the chance to check their quotes.

We also investigated possible online and other sources of information about the sites that could tell different groups of people about their existence, history and how to behave when visiting.

6.1. Touristic Interest

Sámi offering sites and suggested Sámi offering sites with no historical background are used as tourist attractions in Finland (Ruotsala 2008; Äikäs 2015; Valtonen 2019), which led us to hypothesise that this could be the case for the well-known offering sites in Alta too, whether in an organised fashion or with individual tourists visiting the sites on their own. However, the tourist information office has no printed information about the offering sites in the area, and staff report that tourists never ask for information about Sámi offering sites there. Instead, they ask more generally for things to do in a day or an afternoon, and they often decide to go for a tour of the Alta Canyon, which is the largest in northern Europe and a place of beauty (Knutsen 2019). An experienced bus driver/tourist guide working for North Adventure in Alta confirmed this impression, as he could only remember one occasion when a party from abroad had asked specifically to go to Áhkku. This was a crew from Disney visiting around 2016 who were looking for inspiration from Sámi culture (Matte 2019).

The main museum in the area is Alta Museum, which focuses on preserving and conveying the extensive World Heritage rock art sites found there. However, their exhibitions also include a section on Sámi pre-Christian religion, featuring photos of the sacred mountain Háldi and a small offering stone situated on the island Årøya in the Alta fjord as examples of the Sámi sacred and mythical sites in the landscape. There seems to be a general interest in this aspect of local history among foreign tourists or local groups visiting the museum alike (Søborg 2020). This is the reason why the first publication from the museum in 1994 was a pamphlet on pre-Christian Sámi beliefs (Hætta 1994). Some years ago, the museum website included a recommendation to go for a walk to Seideodden, the location of Áhkku (Olsen 2020). However, in the 30 years that our informant has been guiding people at Alta Museum, there have never been questions about how to get to visit a nearby Sámi offering stone (Søborg 2020).

Thus, the local tourist information centre and main museum do not actively guide visitors in the direction of the Sámi offering sites today. They do sell copies of the book Altaturer (“Alta hikes”), which was First published 2012 and contains descriptions of 88 hiking routes in the area, including hikes to Áhkku and Fállegeađgi. This is written in Norwegian and primarily aimed at the local audience. We will return to the book and its effect on the visiting rate below.

Quantifying touristic interest is somewhat difficult because many tourists in Finnmark never contact a tourist information office but find their own way to the interesting sites they want to see (Olsen 2017b). For instance, every year, more than 3000 people visit the northernmost point on the European mainland, Knivskjellodden on Magerøya, and, to our knowledge, there are no organised trips there (Olsen 2020).

Part of the reason is that tourists today get much of their information online. Consequently, we performed Google searches for “Seidekjerringa” and “Áhkku” in combination with relevant search terms1 and equivalent searches for “Fállegeađgi” or “Falkesteinen” to map the available information. The result shows that the official online visitor guide for the area, visitalta.no, does not mention Áhkku and Fállegeađgi. It does promote the distinct mountain Háldde as a sight worth seeing, but focuses on the late 19th-century northern light observatory built on it and how this serves as a suitable hiking destination, rather than on the fact that this is also a Sámi sacred mountain. This is of course an object of interest concerning how Sámi cultural heritage in the area is conveyed to tourists, and one informant for this study specifically pointed out that it would be preferable if people visiting this site were made aware of the significance of the mountain to Sámi tradition too (Sara 2019). The site is not further included in the discussion here, as it does not have the same focal depositary points as Áhkku and Fállegeađgi.

However, the sites in question here are promoted in both Norwegian and English by the privately run website travel-finnmark.no, which posts information about sights and travel routes in the county under different topical labels, including “Mythical places”. In both cases, the locations of the sites are marked on a digital map. The information about Áhkku, published in 2015, also includes a description of how to get there, and a brief note on old Sámi religion and offering tradition, as well as the meaning of the place name. The information about Fállegeađgi, published on the website in 2016, focuses on stories about the misfortune of those who failed to make offerings or took things from the offering site (referring to Sveen 2003). There is no description of the hike necessary to get there.

The hike to Fállegeađgi is described in English on the website geocaching.com, as a geocache was placed at the site in 2016, containing a logbook, pencil, and some trading items. The website gives a brief description of the meaning of offerings in Sámi tradition. It also notes the presence of animal remains and other objects testifying to the continued offerings at this site, illustrated with photos: “Once you get here, you’ll see that people are bringing gifts to the Falcon rock in our times as well.” Similarly, a geocache placed at Áhkku, called “Seidekjerringa”, in 2018, is described in the website through a short text about the Sámi animistic worldview and mentions that the sieidi is still receiving offerings.

This testifies to a certain availability for non-local visitors, but the physical remains at the sites and the interviews indicate that non-local tourists account for a very limited number of the visitors to these particular sites. This may be partly because they are not promoted by the local tourist guides, but also because most tourists look for activities that do not last too long or demand too much effort. This is not necessarily the case everywhere; studies of coins recently left at known Sámi offering sites rather suggest that people from a variety of countries visit and interact with some such sites (Äikäs and Salmi 2013; Äikäs 2015). This difference emphasises the individuality of sites within this category, where use depends on the local cultural context, centrality, accessibility, topography and the reception history of the place (Mathisen 2010; Spangen 2013, 2016; Äikäs and Spangen 2016).

6.2. Local Visitors

As noted above, the information available about the sites seems to circulate mainly in the local community, and to a lesser extent in a wider circle of potential visitors. The majority of online references to these sites, on for instance blogs or social media, are made by local visitors who take photos and record their hikes as adventures or workouts.

The term “local visitors” may seem a convenient category of investigation, but it should be kept in mind that the local communities nearby the offering sites are highly diverse. Alta is the largest town in Finnmark, with 20,446 inhabitants in 2017. These inhabitants identify as Norwegian, Sámi, Kvaens and/or other ethnic or national groups including groups of immigrants. Furthermore, the term “Finnmarking”, i.e., “a person from Finnmark”, is quite usual and can include attachment to several cultural traditions, not giving any of them preference (Olsen 2020). Making the matter more complex, the Sámi in Alta may further identify as coastal Sámi, mountain or reindeer-herding Sámi. These groups have varied histories, traditional subsistence strategies, cultural expressions, dialects and indeed different experiences with the Norwegian assimilation policies from the 19th century onwards (e.g., Minde 2003).

Thus, a variety of local groups may interact with the Sámi offering sites in question. Our interviews suggest that these may be divided into three main groups, partly based on ethnic identity but also on certain interests and activities: schools, Sámi groups and individual hikers. All three categories include people of different sexes, ages and/or ethnic backgrounds, resulting in varied knowledge about and use of the sites, within as well as between the groups. Consequently, they may all have several and multi-layered motives for depositing objects at the sites.

6.3. Use of the Sites by Schools

The use of Sámi offering sites as excursion destinations for schools is known from other northern Norwegian contexts. The main aim is usually to convey Sámi culture and ethnic religion to the schoolchildren, while also exploring the geography, botany and geology of these areas. For some offering sites, this is done in a systematic form with regular visits (Antonsen and Brustrøm 2002; Spangen 2016, p. 220). Pupils from the Alta Secondary School (Alta ungdomsskole) regularly visit Fállegeađgi as an autumn outing, mostly as a hiking destination. The school has several classes at each stage. One class has Sámi as the main learning language and includes at least some pupils for whom Sámi is their mother tongue. These classes usually start the school year in the autumn by going on an excursion to a site within cycling distance. Áhkku was recently included as one such destination. Few of the students know about the offering site beforehand, even if they know about other offering sites nearby, including Fállegeađgi. The interviewed teacher, who is from Alta, also said he had not learned about the site before joining the teacher’s college in 2007–2008. On a visit to Áhkku during August 2019, this teacher spoke to the students about how it is a sacred site for some people, how offerings were made for several reasons, such as fishing and hunting luck, or a prosperous and happy life, and how today it could be compared to the offerings made at wishing wells. Pupils were encouraged to make offerings, which at least some did. The place was treated with respect; for instance, nothing was moved or taken away from it. During the visit, another group arrived carrying fishing and hiking gear, presumably an upper secondary school class specialising in nature studies and outdoor activities (Olsen 2019b).

The nearby primary school, Komsa skole, also uses Áhkku as an excursion destination and to convey knowledge about Sámi history and culture to students. Like the secondary school, some of the classes have Sámi as the main teaching language. Every three years, all these pupils visit Áhkku, so they have all been there at least once when moving on to the secondary school. Few pupils seem to know the site beforehand, and the teacher interviewed, who is originally from the neighbouring municipality of Karasjok but has lived in Alta for a long time, had not heard about it until quite recently (Nordby 2019).

On the latest visit, the teacher told pupils about Sámi beliefs and traditions, as well as aspects of natural science, such as how different elements make rock formations. The children did leave things according to the traditions they had heard about, but this had not been prepared, so they placed whatever they had at hand by or on the rock, including pretty pebbles, bead strings, coins, twigs and heather tied together into a small bouquet (Nordby 2019). Thus, schools use the sites both for hiking and exploring nature and for conveying knowledge about Sámi history and religion. The latter may include depositing things.

6.4. Sámi Use of the Sites

For understandable reasons, considering the historical persecution and oppression of the Sámi religion, there has been a general reluctance among Sámi people to admit to any sort of continuous offering tradition. It is more often acknowledged that people leave coins or felled reindeer antlers at the sites in respect of their ancestors and beliefs. The parts of slaughtered reindeer at Fállegeađgi may be an example of this, as it is unlikely that other visitors would be able to obtain these to deposit at the site. However, who placed the animal parts here has yet to be confirmed.

The reindeer-herding Sámi interviewed for this study said he had no knowledge of any Sámi use of Fállegeađgi, so that if Sámi people left reindeer meat there, this must have been done in secret. He noted, however, that his family uses the area around Fállegeađgi in spring and autumn, when the ground is snow-covered, which also hides a good part of the depositions at the site (Eira 2019). There are other reindeer herders using the area at other times of the year, whom unfortunately we were unable to reach for an interview.

The tradition of collecting felled reindeer antlers and placing them around known offering stones is particularly common in reindeer-herding contexts. The coastal Sámi in Norway based their subsistence on fishing and husbandry farming, and offering sites along the coast are often related to fisheries, though reindeer, sheep and farming products such as cheese and butter have been offered here too (Qvigstad 1926, pp. 320, 324, 340). Another discrepancy between the mountain and coastal Sámi groups is the form and severance of the assimilation measures they suffered while this was Norwegian official government policy. The more sedentary coastal Sámi were generally in closer contact with Norwegians, and many communities suffered a near or full annihilation of Sámi language and culture (Bjørklund 1985; Minde 2003). This is not to say that the mountain Sámi did not suffer from these “Norwegianisation” efforts, but rather that the measures and effects of these varied, as did the more or less subversive Sámi responses. To some extent, these historical differences are reflected in different attitudes among these Sámi groups to questions about the exposure and use of Sámi cultural heritage sites today.

In Alta, the local coastal Sámi association Gula have organised excursions to Áhkku for both children and grown-ups, partly together with the Alta Sámi language centre, to highlight the coastal Sámi culture of the area. At least some participants knew about the site in advance but apparently not all of them. This could, however, have to do with Alta being a dispersed community where people living in the western part of the town area have not necessarily been familiar with the eastern area where Áhkku is situated, regardless of their ethnic identification (Olsen 2020). As explained by the second leader of Gula, the visitors have left things as a symbolic act to reflect on the use of the site, but she would encourage those who visit to leave perishable objects rather than plastic items or coins (Sara 2019). Thus, the Sámi interaction with the sites includes both not interacting with them directly and interacting with them as an educational and memorial pursuit, partly through leaving objects.

6.5. The Use of the Sites as Hiking Destinations

Going hiking has been a very strong tradition in Norway since the introduction of mountain climbing and hiking as a leisure activity for tourists in the 19th century, if not as widespread a tradition as the national self-image might claim. Over the last decade, it has become increasingly popular to do shorter walks from home to local mountain tops or other goals in the afternoon or at weekends, often as part of a “ten peaks” challenge or in order to ensure more everyday exercise and better health, which is also actively encouraged by the authorities. While hiking was usual even before this, the increased focus on walking or trekking as being important to public health has led to more frequent local outings and use of local destinations.

The Sámi offering sites of Áhkku and Fállegeađgi have obviously been known by at least some locals since they initially came into use. The depositions observed during a visit to Áhkku in 2000, of coins, rocks and a letter, reflect a certain local knowledge. The recent local deposition practice was also mentioned in the signpost put up by Alta municipality a few years later (Olsen 2017a, p. 121). The signposting was related to a project about the Komsa mountain area run by Finnmark County (2004). In another effort to improve the knowledge about and accessibility of the site, the path was also marked in blue paint and with wood markers hung from trees with the municipality coat of arms, of which there were still remains in 2012 (Ottem 2020). The present authors did not see these signs in 2017.

Despite these efforts, the most significant change in people’s knowledge about and behaviour at these sites seems to be related to the publication of the aforementioned book Altaturer in 2012 (Ottem 2012). By 2019, the book Altaturer had sold 4800 copies (www.altaturer.no), an extraordinary number for a local tour guide in an area with approximately 20,000 inhabitants. Here, the hike to Áhkku is described as a favourite trip, where a short walk brings you to a point in Alta where you are surrounded only by sea and mountains. The book describes the features, role and use of sieidi stones in Sámi pre-Christian religion, in line with the author’s intention of giving an accurate and respectful description of these traditions (Ottem 2020). It also describes how you can find candles, coins and other offerings at the rock today, and suggests that visitors find some nice natural object along the shore to give to Áhkku—“grandma” (Ottem 2012, p. 85).

As our observations have not been as consistent for Fállegeađgi, an increase in visitors cannot be pinpointed in the same way. However, the description of the site in Altaturer notes that there were already many objects at the site when it was visited by the author in 2012. The book specifically mentions a torch, a backpack, lots of coins, fishhooks, several bottles of alcohol and the entire skeleton of a reindeer. The author does not encourage leaving things here but advises that taking something from an offering site is bad luck. The author’s photos still appear to show fewer objects in 2012 than during our visit in 2017 (Ottem 2020, (Ottem 2012, p. 117)).

It should be mentioned that the sites are also depicted and described along with other Sámi offering sites in Finnmark in photographer Arvid Sveen’s book Mytisk landskap (“Mythical landscapes”) from 2003, although without explicit descriptions on hiking routes. This apparently did not result in a similar increase in visitors.

The observed increase in objects left by Áhkku in 2013 (Olsen 2019a) is likely to reflect the popularity of and specific hiking encouragement in the book Altaturer. Even before the book was published, some “sample trips” to other sites presented in the local newpaper Altaposten reportedly resulted in a lot more visitors (Ottem 2020). Conceivably, the book made the offering sites better known to a broader audience, with Áhkku as the easiest available close to Alta. As the category includes a wide variety of people from different backgrounds, their behaviour at the sites cannot be assumed to be heterogeneous, and motives for any depositions would be diverse. For instance, the category “hikers” includes grown-ups and children alike; in 2016, the local branch of the Norwegian Trekking Association (DNT) organised a trip specifically for children to Áhkku, where one activity was to pick branches, pine cones and other nice objects to make offerings by the stone for some good wish, like a warm summer (Alta DNT 2016).

6.6. Contemporary Deposits: Offerings or Mimicked Practices

The intentionality of leaving objects at the sieidi seems to vary between and within the groups of findings at Áhkku mentioned above. While many of the toys and ‘pocket holdings’ are objects that people can carry with them on a daily basis and leave on impulse, parting with jewellery or clothing —even if they are not valuable—might demand more reflection. Natural objects found at the sieidi included not only things that a person could have picked up at the site or on the way there, but also things that were brought from somewhere else, for example, an amethyst and certain flowers. In previous research on the sieiddit of Taatsi and Kirkkopahta in Finland, the use of natural objects has been ascribed to contemporary Pagan2 practices (Äikäs 2015; Äikäs and Ahola in press). There are similar examples from Britain, Southern Finland and Estonia, and interviews give evidence of the preference of decomposing objects as contemporary Pagan offerings (Wallis 2003; Blain and Wallis 2007; Jonuks and Äikäs 2019). However, this preference is also shared by local Sámi in Alta (Sara 2019). In the conducted interviews, there is no reference to contemporary Pagan practices at the Alta sites. This does not of course strictly rule out the possibility of contemporary Pagan visits, but it makes it somewhat unlikely. It is therefore interesting to note that contemporary Pagan practices and other people’s ideas of appropriate offerings are similar and not easily distinguished in the material.

On the other hand, the handiness of small stones and their placement next to each other might indicate a practice where a later visitor has mimicked the behaviour of previous visitors (Figure 6). Archaeologist Ceri Houlbrook (2018) has witnessed this kind of imitating practice when studying the use of coin trees in Britain and Ireland. The wish that others may imitate one’s behaviour might, on the other hand, also be a reason for contemporary Pagan offerings (Wallis 2003; Blain and Wallis 2007). The handiness of natural objects makes them available for different groups visiting the site. One of the interviewees mentioned that a flower bouquet was offered by a schoolchild (Nordby 5 September 2019).

Figure 6.

Small rocks placed on the Áhkku sieidi rock formation. (Photo: T. Äikäs).

A more intentional use of specific objects might be the finds that seem to address amorous wishes, most clearly a single rose placed under a heart-shaped stone (Figure 7). Hearts are also present in the form of a reflector and a small decorative item.

Figure 7.

A heart-shaped rock holding down a rose deposited on the Áhkku sieidi rock formation. (Photo: T. Äikäs).

Most of the finds lay on the ground by the Áhkku sieidi stone in 2017 (Figure 8). They may have fallen down from their original place or have been dropped there by the person who left them there. The coins that have been pushed into the cracks of the stones indicate a more deliberate positioning of the objects. This shows how the intentionality of the offering can be manifested in either the selection of a specific object or in the placing of even a mundane object, although it is also dictated by the material of the stone and where different things can be placed. Over the years, it has also been observed that “things move around”. Things that are found on the ground in the spring may have been on a shelf the previous autumn and brought back again onto a different shelf the following autumn. Hence, many of the objects are being continuously repositioned on the rock. In some cases, the different items seem to have been deliberately ordered (Olsen 2020). This is quite interesting, as it shows how people do not necessarily leave new things when they visit but find ways of interacting with the site through objects that are already there.

Figure 8.

Old signs once marking the path to the site and other objects at the foot of the Áhkku sieidi rock formation. (Photo: T. Äikäs).

In some cases, this reuse and interaction with the sieidi may appear close to vandalism. This could be said of the trail signs that have been taken from the track to the sieidi Áhkku and left at the stone, as well as of the mark painted on the sieidi in white (Figure 9). At first glance, the latter may be associated with graffiti or tagging, but the significance is not that easy to understand. The white paint is most likely a repainting of an older mark, and there used to be two such white marks on the rock (Olsen 2020).

Figure 9.

White spray paint on the Áhkku sieidi rock formation. (Photo: T. Äikäs).

At Fállegeađgi, the finds are more homogenous than at Áhkku and seem mostly to indicate the visits of locals and hikers. Reindeer bones and antler seem like unlikely deposits to be carried along on a hiking trip, whereas food-related items, clothing and hiking equipment could have been left by someone briefly visiting the site with or without a premediated plan to offer something. The fishing-related items could belong to either of these groups, even though it is noteworthy that the closest fishing waters are some 2 km from the sieidi as the crow flies. In summertime, the people in the Fállegeađgi area usually have a purpose, such as fishing, hunting or reindeer herding, and visiting the stone is actually a time-consuming detour for the two first groups. Thus, such finds indicate that people do visit the site specifically to interact with the sieidi. Mountain bikers also use the area, but they usually stay on the tracks. Wintertime visits are different, as these are made on snow by cross-country skiers who can make the detour more easily (Olsen 2020).

7. Effects of the Different Uses

It seems clear that the sites discussed here hold limited interest for tourists and non-local visitors, and the extent to which these affect the sites is minimal. The schools use the sites with the intention of informing local schoolchildren, both Sámi and non-Sámi, about the traditional culture and history of their home area. After a long period of suppression of Sámi culture in the Alta area, this is a significant change that has occurred since the Sámi political and cultural revival in Norway in the 1970s and 1980s (Minde 2003). The primary school now visits Áhkku regularly, but since many pupils in the secondary school did not know the site before a visit in 2019, this is apparently a fairly recent development. The teachers we spoke to had taken trips to these sites largely on their own initiative and based their presentation and activities on their own former knowledge of these specific sites and Sámi culture, history and religion in general. The act of depositing objects was sometimes encouraged but not planned in advance, resulting in somewhat random objects being placed, especially at Áhkku.

Sámi groups have used the sites in much the same fashion, promoting an internal and external awareness of the ancient Sámi presence in Alta and, in the case of Áhkku, emphasising the presence of a coastal Sámi culture in addition to that of the mountain reindeer-herding Sámi. The Gula visits have resulted in some depositions at the site, but it is encouraged to leave only perishable objects. Contrary to this, the reindeer-herding Sámi interviewed expressed strong feelings about any recent use of the sites (see below) and said he had no knowledge of any Sámi use of Fállegeađgi (pers. comm. Eira 2019).

Hikers and skiers are the most likely origins of the large increase in objects left at these sites over the last decade, presumably with the exception of animal remains. The variation in objects deposited is probably based on different understandings of the significance of the sites, not least because our current knowledge of Sámi rituals on offering sites is limited. On the one hand, some want to adhere to some opaque old Sámi offering tradition based on historical and ethnographic sources that may be unrelated to the time and place in question. On the other hand, some have just been told that when you go there you should leave something, as stated by one visitor whom we met on our way to Áhkku in 2017. In fact, the objects themselves may be what tell them this. As described above, how people interact in terms of deposition is also affected by what is already at the sites, making the accumulation self-reinforcing (Wallis 2003; Blain and Wallis 2007; Houlbrook 2018). Deposits attract more deposits, and especially similar deposits to those that have been made before.

Concerning what is deposited, the two sites are somewhat different. As one of the schoolteachers commented, people seem to leave things by Áhkku as a symbolic act, while there is more “rubbish” by Fállegeađgi (T. A. Olsen 5 September 2019). This tallies with our own observations, as there is a larger amount of food wrappers, toilet paper and objects that might be classed as “litter” at this site. This obviously has to do with topography and use—Áhkku is situated such that it is less inviting to camp right next to the rock, while Fállegeađgi is a skiing destination that provides shelter in open terrain. The use of the site as a shelter was demonstrated by the remains of a campfire close by the sieidi stone. People may well also leave or lose things in the snow that reappear as rubbish around this site in summertime. On the other hand, the distinction between ritual objects or offerings and litter can be fluid, and what appears as rubbish to one person might have ritual value to another (Finn 1997; Houlbrook 2015; Hukantaival in press).

8. Attitudes to the Current Use of the Offering Sites

It is clear that many of those actively relating to the sites today do this with the best intentions of promoting understanding of Sámi culture and past religion, and how this is an integral part of the history of Alta. Leaving objects is seen as a way to reflect on and respect its meaning (Sara 2019; Nordby 2019; Olsen 2019b; Ottem 2012, p. 85). Áhkku is seen as an important testament to the presence of coastal Sámi culture in Alta, and the representative for Gula who was interviewed expressed a wish for more information for visitors both here and on the sacred mountain Háldde (Sara 2019).

The litter-like deposits at Fállegeađgi may to some extent explain the more negative attitude to the current use from a mountain Sámi perspective. Our Sámi reindeer-herding interviewee mentioned an increase in objects in recent years and was not happy about more and more people being aware of the site and using it as a hiking and skiing destination. He considered most depositions as litter, including recent coins, which might be seen to mimic an older Sámi tradition. While he agreed that providing more information through signage might be a good idea to protect the sites, he considered limiting knowledge of them as more appropriate in order to avoid what he sees as misuse, which includes the heightened wear on the adjacent terrain. He strongly opposed our initial idea of an online questionnaire to gather information about the use of the sites, as this would only result in more widespread knowledge about and (mis-)use of the sites, comparing the latter to the desecration of churches (Eira 2019).

The situation at Fállegeađgi and the wish for restrictions has to be seen in a wider context. The area is used as grazing land for reindeer, and in northern Norway in general there have been continuous discussions and conflicts surrounding this use of various landscapes and other sites of interest, such as mining, the exploitation of wind energy and hydroelectricity and also recreational use (e.g., Olsen 2011).

9. Discussion

The sites discussed in this article are undoubtedly old Sámi offering sites that have been in more or less continuous use for centuries. A more recent deposition practice has been observed at both sites over a long period of time, but there seems to have been a distinct increase in objects since 2013 (Olsen 2017a, p. 122). This is likely a result of the publishing of the book Altaturer (Ottem 2012). Such private initiatives to disseminate knowledge of Sámi offering sites are not necessarily all negative, but more awareness of the opinions of key stakeholders and the problematic aspects of increased visits to such sites may be needed. Natural heritage sites are usually available to everyone in Norway based on legislation on public right of access to all countryside areas. It is perhaps not immediately evident that sacred Sámi sites, which are usually natural rock formations, mountains, etc., are both of great symbolic value and in fact automatically protected by law and should be treated with more care than other natural landmarks. Furthermore, there is little to coherently inform individuals who wish to behave respectfully about what this would entail. Paradoxically, the exposure of Fállegeađgi and Áhkku may serve precisely to increase this understanding if information about the traditions related to them is made easily available at the sites.

The interviews and most of the objects left at the sites suggest that visitors to the sites are local people in different capacities and of different ages, occupations and ethnic backgrounds. Defining who are key stakeholders in these contexts is nevertheless not a straightforward issue because of the heterogeneity of the population in Alta, where there have been frequent changes in ethnic identification and there are also several different Sámi communities (Berg-Nordlie 2018). This results in a variety of ways of interacting with the sites. Some will have some knowledge about their being old offering sites, while others have rather vague ideas about the past and present meaning and use of them, so they behave accordingly, leaving substantial amounts of random deposits. This is upsetting for some Sámi stakeholders who would prefer to keep such sites secret, protected from wear, or at least clear of random deposits (Eira 2019). These views are, as mentioned, related to a broader debate about landscape use, but such opinions obviously need to be taken into consideration in any future dissemination or facilitation of access to the sites.

It is difficult to undo public knowledge about these sites as accessible hiking and skiing destinations. The popularity of hiking in general and the book Altaturer in particular predicts that the sites will be visited by an increasing number of people in the years to come. It would seem that more information about the meaning of and how to relate to the sites in a way that is not offensive to stakeholders is, at this point in time, the most viable way forward. The hope of the interviewees was that signposting would install a higher degree of awareness in visitors that these sites are to be treated with respect, and would provide more understanding of what it means to leave something there and perhaps make visitors consider more carefully if they should leave something and, if so, what, even if this for some of the interviewees would at best just be a way to slightly alter an already unacceptable situation (Sara 2019; Eira 2019). Having said that, views vary between Sámi stakeholders, as the Sámi in Alta were more positive to the exposure of Áhkku, because this would promote Coastal Sámi heritage as a more visible and integral part of the Alta cultural history than it used to be.

Signs with instructions on how to behave have been used with relative success at far more famous and widely visited indigenous sacred sites elsewhere in the world, such as Uluru in Australia. In studies in Finland, it has been noted that local Sámi both expressed their wish to conceal the location of the sacred places in order to protect them and to provide more information so that raised awareness would help protect the sites (Äikäs 2013). In Inari, Finland, visitors disembarking on a Sámi sacred island Ukonsaari (Äijihsuálui) have been stimulating discussion since the early 2000s because walking on the sacred island could be seen as disrespectful, just like the platforms and stairs built there in order to protect the fragile environment of the island. In 2019, a local tourist operator decided to discontinue allowing disembarkation during the cruises it offered, in response to newspaper articles written by a local Sámi and archaeologist (Torikka 2019). This has not, however, prevented individuals from landing on the island by themselves. In any case, these kinds of restrictions could not be used at the sites in question here due to their location and accessibility on the mainland.

Having established that the recent users of these offering sites are mainly the local population in Alta and not tourists, this gives other opportunities for integrated approaches to the dissemination and protection of the sites. One important aspect, which is also seen at other (perceived) offering sites, is active use by schools and kindergartens to convey knowledge about Sámi culture, history and religion to new generations of locals (Äikäs and Spangen 2016; Spangen 2016). This would be in accordance with the attitude of the coastal Sámi representative in Alta, although there is a need for guidelines concerning behaviour and the practical and material consequences of such visits. The visits are currently made on the initiative of individual schools and teachers or other organisations for children’s activities, and knowledge about old Sámi offering rituals and sacred sites varies. Some teachers have encouraged the children to leave objects, and also do so themselves, while others emphasise that what they leave should be perishable, or do not focus on the children engaging directly in this practice at all. As depositions are self-reinforcing, this leaving of non-perishable or random objects without thoroughly contextualising the practice can be problematic. The offerings left by non-Sámi could also be seen as problematic within the framework of the cultural appropriation of religion: the borrowing of cultural elements from indigenous people without proper knowledge of their meaning. Even though cultural appropriation has been widely discussed in Sámi contexts in recent years, there has been no reference to contemporary offerings (e.g., Humalajoki 2017; Äikäs and Salmi 2019).

Hence, better information for visitors in terms of proper and, importantly, good-quality signposting to emphasise the importance of the information (Søborg 2020) may be a way of remedying a use that is offensive to some stakeholders. At the same time, the aim of these visits, the learning experience of the schoolchildren, is enhanced. If such signposting is to be realised, it would be important for both academic experts on ethnic Sámi religion and the local Sámi communities in Alta to be involved in discussing and ratifying what information should be given before a sign is put up. Notably, the information about appropriate respectful behaviour may differ between the two sites, because each Sámi offering site has its unique cultural historical background and biography (Mathisen 2010; Äikäs and Spangen 2016).

Teachers and pupils would benefit even more from a full school programme, preferably developed in cooperation with local Sámi organisations, that would prepare them for a visit in advance. This could include, for instance, a comprehensive visitor’s kit with thorough key information, activities teachers and classes can do in preparation, discussion points and, of course, guidelines for appropriate behaviour at the sites. This would achieve both increased understanding of Sámi cultural history and of the issues involved in using these sites for such excursions, even including current issues of littering in general. In time, schoolchildren would likely influence their parents who constitute the hikers and other visitors. This may help to create a knowledgeable population of responsible users of local Sámi cultural heritage.

10. Conclusions

Observations were made at two Sámi offering sites in Alta, Áhkku by the coast and Fállegeađgi inland, over several years, noting a living tradition for leaving a large variety of objects at these sites. The publication of a hiking guide including these two sites in 2012 has increased the number of visitors and depositions substantially, especially at Áhkku. It also seems that this has resulted in more litter-like depositions at Fállegeađgi. Through analyses of the object composition and interviews, we have established that the visitors are mainly local hikers and schoolchildren, not tourists and contemporary Pagans as in the case of Sámi offering sites elsewhere. The fact that, since 2012, the sites have become well known and used as hiking destinations for a variety of local groups presents some challenges in how to protect and convey them in the future. While some Sámi stakeholders are positive to and actively encourage the dissemination of especially Coastal Sámi culture through visits and interaction with such sites, other Sámi stakeholders are strongly opposed to the increase in visitors and/or random depositions, defining this as littering or even desecration. Despite a will among many visitors, including the author of the popular hiking guide, to behave in a respectful way, there is little coherent information about what this would entail. As the sites in question are by now very well known in the local community, the best way to mediate potential conflicts appears to be proper signposting with thorough information and guidelines for behaviour developed in cooperation with stakeholders. A further measure could be the development of a school programme to ensure and increase understanding and responsible use of Sámi cultural heritage in Alta.

Author Contributions

M.S.: Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, analysis, writing original draft, visualisation, writing and editing final version, T.Ä.: Conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, analysis, visualisation, writing and editing final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Äikäs’ stay in Norway for the investigations was covered by the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters through the project ‘Religious Contacts and Religious Changes: Interdisciplinary Investigation of Site Biographies of Sámi Ritual Places’ (294626). The publication charges for this article have been funded by a grant from the publication fund of UiT—the Arctic University of Norway.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Äikäs, Tiina. 2013. “Kelle se tieto kuuluu, ni sillä se on.” Osallistava GIS Pohjois-Suomen pyhien paikkojen sijaintietoon liittyvien näkemysten kartoituksessa. Master’s thesis, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Äikäs, Tiina. 2015. From Boulders to Fells: Sacred Places in the Sámi Ritual Landscape. Helsinki: Archaeological Society of Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Äikäs, Tiina, and Marja Ahola. In press. Heritages of past and present. Cultural processes of heritage-making at ritual sites of Taatsi and Jönsas. In Entangled Rituals and Beliefs. Monographs of the Archaeological Society of Finland 9. Edited by Tiina Äikäs and Sanna Lipkin.

- Äikäs, Tiina, and Anna-Kaisa Salmi. 2013. ‘The sieidi is a better altar/the noaidi drum’s a purer church bell’: Long-term changes and syncretism at Sámi offering sites. World Archaeology 45: 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Äikäs, Tiina, and Anna-Kaisa Salmi, eds. 2019. Introduction: In search of Indigenous voices in the historical archaeology of colonial encounters. In The Sound of Silence: Indigenous Perspectives on the Historical Archaeology of Colonialism. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Äikäs, Tiina, and Marte Spangen. 2016. New Users and Changing Traditions—(Re)Defining Sami Offering Sites. European Journal of Archaeology 19: 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Äikäs, Tiina, Anna-Kaisa Puputti, Milton Núñez, Jouni Aspi, and Jari Okkonen. 2009. Sacred and Profane Livelihood: Animal Bones from Sieidi Sites in Northern Finland. Norwegian Archaeological Review 42: 109–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alta DNT. 2016. Vi besøker Seidekjerringa. Web Page Announcement. Available online: https://alta.dnt.no/aktiviteter/79650/834373/?_ga=2.251966529.957513466.1585644366-759145878.1585644366 (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Antonsen, Lene, and Gudbrand Brustrøm. 2002. Fangstanlegget ved Gálgojávri. In Menneske og miljø i Nord-Troms: Årbok 2002. Storslett: Nord-Troms historielag, pp. 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Nordlie, Mikkel. 2018. The governance of urban indigenous spaces: Norwegian Sámi examples. Acta Borealia 35: 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, Ivar. 1985. Fjordfolket i Kvænangen. Fra samisk samfunn til norsk utkant 1550–1980. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Blain, Jenny, and Robert J. Wallis. 2007. Sacred Sites—Contested Rites/Rights. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eira, Aslak J. 2019. Leader, reindeer grazing district 30C in West Finnmark. Personal communication. August 27, August 29, September 2.

- Finn, Christine. 1997. ‘Leaving more than footprints’: Modern votive offerings at Chaco Canyon prehistoric site. Antiquity 71: 169–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnmark County. 2004. Komsa i tid og rom. Project Website. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20110809134946/http://www.fifo.no/komsa/ (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Fossum, Birgitta, and Erik Norberg. 2012. Reflexioner kring dokumentation av traditionell kunskap och arkeologi på sydsamiskt område. In Ett steg till på vägen. Resultat och reflexioner kring ett dokumentationsprojekt på sydsamiskt område under åren 2008–2011. Edited by Ewa Ljungdahl and Erik Norberg. Östersund: Gaaltije, pp. 8–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hætta, Odd Mathis. 1994. The Ancient Religion and Folk-Beliefs of the Sámi. Alta: Alta Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Hallström, Gustaf. 1932. Lapska offerplatser. In Arkeologiska studier tillägnade H. K. H. Kronprins Gustaf Adolf. Stockholm: Norstedt, pp. 111–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hesjedal, Anders. 2004. Vinterlandet Norge: Om hvordan samisk forhistorie har blitt usynliggjort i norsk arkeologi. In Samisk forhistorie. Várjjat Sámi Musea Čallosat 1. Edited by Mia Krogh and Kjersti Schanche. Varangerbotn: Varanger Samiske Museum, pp. 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Högström, Pehr. 1980. Beskrifning öfwer Sweriges Lapmarker 1747. Umeå and Stockholm: Två Förläggare Bokförlag. First published 1747. [Google Scholar]

- Houlbrook, Ceri. 2015. The penny’s dropped: Renegotiating the contemporary coin deposit. Journal of Material Culture 20: 173–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlbrook, Ceri. 2018. The Magic of Coin-Trees from Religion to Recreation. The Roots of a Ritual. London: Palmgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hukantaival, Sonja. In press. Vital scrap—The agency of objects and materials in the Finnish 19th-century world view. In Entangled Rituals and Beliefs. Monographs of the Archaeological Society of Finland 9. Edited by Tiina Äikäs and Sanna Lipkin.

- Humalajoki, Reetta. 2017. Alkuperäiskansat, kulttuurinen omiminen ja asuttajakolonialismi. AntroBlogi. Available online: https://antroblogi.fi/2017/11/alkuperaiskansat-ja-asuttajakolonialismi/ (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Jonuks, Tõnno, and Tiina Äikäs. 2019. Contemporary deposits at sacred places. Reflections on contemporary Paganism in Finland and Estonia. Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore 75: 7–46. Available online: http://folklore.ee/folklore/vol75/jonuks_aikas.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020). [CrossRef]

- Keilhau, Baltazar Mathias. 1831. Reise i Öst- og Vest-Finnmarken samt til Beeren-Eiland og Spits- bergen i aarene 1827 og 1828. Christiania: Cappelen. [Google Scholar]

- Kildal, Jens. 1945. Afguderiets Dempelse. In Nordnorske Samlinger 5. Edited by Marie Krekling. Oslo: A. W. Brøgger, pp. 135–44, Written in 1730. [Google Scholar]

- Knutsen, Marianne. 2019. Manager, North Adventures/Alta Tourist Information. Personal communication, August 30.

- Leem, Knud. 1975. Beskrivelse over Finmarkens Lapper: 1767. Edited by Asbjørn Nesheim. København: Rosenkilde og Bagger. First published 1767. [Google Scholar]

- Manker, Ernst. 1957. Lapparnas heliga ställen. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen, Stein R. 2010. Narrated Sámi Sieidis. Heritage and Ownership in Ambiguous Border Zones. Ethnologia Europaea. Journal of European Ethnology 39: 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Matte, Jonathan. 2019. Bus driver/guide, North Adventures. Personal communication, August 31.

- Mebius, Hans. 1968. Värro: Studier i samernas förkristna offerriter. Stockholm: Gummessons. [Google Scholar]

- Mebius, Hans. 1972. Sjiele: Samiska traditioner om offer. Uppsala: Lundequistska bokhandeln. [Google Scholar]

- Minde, Henry. 2003. Assimilation of the Sami: Implementation and Consequences. Acta Borealia 20: 121–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niurenius, Olaus Petri. 1905. Lappland, eller beskrivning över den nordiska trakt, som lapparne bebo i de avlägsnaste delarne av Skandien eller Sverge. Edited by Karl Bernhard Wiklund. Svenska landsmål och svenskt folkliv 17: 7–23, Written in 1640. [Google Scholar]

- Nordby, Martin. 2019. Teacher, Komsa elementary school. Personal communication, September 5.

- Olsen, Isaac. 1934. Finnernis afgudssteder. In Finnmark Omkring 1700. Aktstykker og oversikter. Annet hefte. Topografika 1638‒1717. Nordnorske Samlinger 1. Edited by Martha Brock Utne Brendel and Ole Solberg. Oslo: Etnografisk Museum, pp. 134–39, Written in 1715. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Kjell. 2011. Fefo, reinsdyr og andre vederstyggeligheter. Norsk Antropologisk Tidsskrift 22: 116–33. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Kjell. 2017a. What does the sieidi do? Tourism as a part of a continued tradition? In Tourism and Indigeneity in the Arctic. Tourism and Cultural Change 51. Edited by Arvid Viken and Dieter K. Müller. Bristol: Channel View Publications, pp. 225–45. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Kjell. 2017b. World Heritage List = Tourism Attractiveness? In Arctic Tourism Experiences. Production, Consumption and Sustainability. Edited by Young-Sook Lee, David Weaver and Nina Prebensen. Wallingford: CABI, pp. 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Kjell. 2019a. Professor, Department of Tourism and Northern Studies, UiT—Arctic University of Norway, campus Alta. Personal communication, June 21.

- Olsen, T. A. 2019b. Teacher, Alta upper secondary school. Personal communication, September 5.

- Olsen, Kjell. 2020. Professor, Department of Tourism and Northern Studies, UiT—Arctic University of Norway, campus Alta. Personal communication, April 22. [Google Scholar]

- Ottem, Lise. 2012. Altaturer: Turmuligheter i Alta kommune. Alta: Turer Lise Ottem. [Google Scholar]

- Ottem, L. 2020. Author/guide, Altaturer. Personal communication, March 31.

- Qvigstad, Just A. 1926. Lappische Opfersteine und Heilige Berge in Norwegen. Oslo: Oslo Etnografiske Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Randulf, Johan. 1903. Relation angaaende Finnernes saa vel i Finmarken som Nordlandene deres Afguderie og Sathans Dyrkelse, som af Guds Naade ved Lector von Westen og de af hanem samestæds beskikkede Missionairer, tiid efter anden ere blevne udforskede. In Kildeskrifter til den lappiske mythologi. Det Kgl. Norske Videnskabers Selskabs Skrifter. 1. Edited by Just Qvigstad. Trondhjem: Aktietrykkeriet, pp. 6–62, Written in 1723. [Google Scholar]

- Ruotsala, Helena. 2008. Does sense of place still exist? Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 1: 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rydving, Håkan. 1995a. The End of Drum-Time: Religious Change among the Lule Saami, 1670s‒1740s. Uppsala: Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- Rydving, Håkan. 1995b. Samisk Religionshistoria. Några källkritiska Problem. Uppsala: Uppsala University. [Google Scholar]

- Salmi, Anna-Kaisa, Tiina Äikäs, Markus Fjellström, and Marte Spangen. 2015. Animal offerings at the Sámi offering site of Unna Saiva: Changing religious practices and human–animal relationships. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 40: 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, Anna-Kaisa, Tiina Äikäs, Marte Spangen, Markus Fjellström, and Inga-Maria Mulk. 2018. Tradition and transformation in Sámi animal-offering practices. Antiquity 92: 472–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sara, Dagrun S. 2019. Wise chairman, Gula, the Sea Sámi association in Alta. Personal communication, September 2.

- Serning, Inga. 1956. Lapska offerplatsfynd från järnålder och medeltid i de svenska lappmarkerna. Stockholm: Museet. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöblom, Tom. 2000. Contemporary Paganism in Finland. In Beyond the Mainstream: The Emergence of Religious Pluralism in Finland, Estonia, and Russia. Edited by Jeffrey Kaplan. Helsinki: SKS. Studia Historica, vol. 63, pp. 223–40. [Google Scholar]

- Søborg, Hans C. 2020. Archaeologist/guide, Alta Museum. Personal communication, March 31.

- Spangen, Marte. 2013. ‘It could be one thing or another’: On the construction of an archaeological category. Fennoscandia archaeologica 30: 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Spangen, Marte. 2016. Circling Concepts: A Critical Archaeological Analysis of the Notion of Stone Circles as Sami Offering Sites. Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 70. Stockholm: Stockholm University. [Google Scholar]

- Sveen, Arvid. 2003. Mytisk landskap. Ved dansende skog og susende fjell. Lublin: Orkana. [Google Scholar]

- Torikka, Xia. 2019. Ensin Australian Uluru, nyt Inarin Ukonsaari—Paikallinen matkailuyritys ei enää rantaudu saamelaisten pyhälle saarelle. YLE Web News 1 November 2019. Available online: https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-11047399 (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Valtonen, Taarna. 2019. Miten Saanasta tuli pyhä? Erilaisten rinnakkaisten Saana-diskurssien tarkastelua. Terra 131: 209–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wallis, Robert J. 2003. Shamans/Neo–Shamans. Ecstasy, Alternative Archaeologies and Contemporary Pagans. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ween, Gro, and Simone Abram. 2012. The Norwegian trekking association: Trekking as constituting the nation. Landscape Research 37: 155–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Search terms used in combination with the site names: Alta, visit, tourist, information. |

| 2 | We recognise that the use of the term “Pagan” can be problematic since it has carried negative connotations referring to someone despicable who did not practise the main religion. The term has nevertheless been established in research literature and is also used as emic category by some contemporary Pagans (see e.g., Sjöblom 2000). In this study, the concept “Pagan” is therefore understood merely as an academic notion without any qualitative implications. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).