Abstract

This paper is concerned with the rights of refugees. The refugee issue has been an acutely charged item on the political agenda for several years. Although the great waves of influx have flattened out, people are continually venturing into Europe. Europe’s handling of refugees has been subject to strong criticism, and the accusation that various actions contradict internationally agreed law is particularly serious. It remains a question of how to respond appropriately to the influx of people fearing for their lives. This paper examines empirically how young people from different denominations in Germany (n = 2022) and how Roman Catholics from 10 countries (n = 5363) evaluate refugee rights. It also investigates whether individual religiosity moderates the influence of denomination or national context. The results show that there are no significant differences between respondents from different denominations, but there are significant differences between respondents from different countries. However, religiosity was not found to moderate the influence of denomination or national context. These findings suggest that attitudes towards refugee rights depend more on the national context in which people live rather than on their religious affiliation or individual religiosity.

Empirical research into human rights does not reflect on the legal status of human rights, but on the legitimacy of these rights as perceived by the persons involved. The development of a human rights culture in a democratic society depends on the support of the people who make up that society. It is therefore important to know if people agree with the rights in question. This research paper examines how young people from different denominations and from 10 countries think about specific aspects of the refugee issue and if attitudes are influenced by religion and by the national context in which they live.1 The paper begins with a theoretical introduction (Section 1), gives information on the design of the study (Section 2), presents the empirical results (Section 3), and concludes with a discussion of the findings (Section 4).

1. Introduction

In this section we first address the issue of refugees in the context of migration to Europe. Second, we consider the possibility that belonging to a religious tradition has an influence on attitudes towards refugees, and third, that this also applies to the origin of respondents representing national cultures of 10 different countries.

1.1. Refugee Rights

For some years now, Europe has experienced an increased influx of people, especially from the war zones in the Near East and from Africa. The wave of refugees peaked in 2015 and 2016, but since then people have continued to try to reach Europe by land or via the Mediterranean Sea. Dealing with refugees has become a politically and legally explosive issue and the large number of refugees has brought Europe to the brink of crisis (Gammeltoft-Hansen 2011). On the one hand, the influx has overwhelmed the countries that lie on Europe’s borders, because these countries had to accommodate masses of people in short periods of time. On the other hand, other European states declare themselves ‘not being responsible’, so that a lack of solidarity is deplored.

At the center of the misery, however, are the people who have escaped from war and the danger to their lives, and who now persevere in unworthy conditions at borders or in camps. The number of migrants worldwide is at an all-time high. They leave their country of origin due to violence, oppression, discrimination or poverty and the naked fear of survival.

In Europe, Italy and Greece are the countries most affected by the influx of refugees. As the situation stands, host countries have been barely prepared to accommodate the large number of people, and that has changed little to this day. In the civil society of many European countries, there is both support for the refugees, but also loud protests against the huge influx of refugees. The treatment of refugees has become Europe’s most pressing problem (apart from the COVID-19 epidemic). Governments are in conflict with each other about which policy is appropriate. The crisis has been exacerbating and a deep trench goes through Europe (Klepp 2010). It cannot be denied that the large number of Muslim refugees in Europe faces a reserved attitude.

Within the nation-states themselves, right-wing populists are gaining increasing influence, precisely because they engage in polemics against immigration, and there is no doubt that Europe’s policy regarding foreigners is in a state of crisis. Populist parties have recorded gains in many countries, not least because of their attitude towards aliens, especially if they are of Muslim origin (Gale 2004). When talking about foreigners or aliens, such references are mainly to people who are already in the country or who could be described as ‘ante portas’. In everyday language, both in the media and in political statements, the terms “economic migrant”, “refugee”, and “asylum seeker” are not used consistently. Economic migrants are people who leave their home country to look for better work and a higher standard of living. According to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (UN 1951), with its additional protocol of 1967, a refugee is someone who has a well-founded fear of being persecuted in his or her home country for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion. A refugee, in fact, is outside the country of his or her nationality and is unable to avail him- or herself of the protection of that country. According to the Geneva Convention on Refugees, persecution may be caused by states or by non-state actors. If people want to apply for asylum, the violence in the home country must come from the state. Persons can apply for asylum if they are politically persecuted, in that they have been subjected to targeted violations of their rights and have left their home country for this reason to seek protection abroad (Hathaway and Foster 2014). The persecution must be directly related to one’s own race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion. General emergency situations such as famine or environmental disasters are not accepted as grounds for asylum. An asylum seeker has to undergo a legal procedure to examine whether his or her fear of persecution is authentic and valid according to the law (U-Minn 2003). This often leads to a distinction being made between ‘proper’ and ‘non-proper’ refugees (Kneebone 2010). To put it somewhat casually: for most people it makes a difference whether the well-trained Christian surgeon from Syria is knocking on Europe’s doors or a Muslim from Afghanistan with hardly any schooling. However, the international community has made a binding commitment under international law to protect refugees and make asylum possible (Ziebertz 2017a; Unser et al. 2018).

In times of what has become a massive exodus from Syria, Iran, Iraq, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Afghanistan, and other countries to Europe, this right has come under pressure. The sheer volume of refugees flooding into Europe has reinforced the latent xenophobia in many European countries. Populist parties are experiencing a significant upsurge in support, especially because of their attitude to refugees, migrants, and aliens. Political leaders in several countries have become advocates of a policy that overrides the human rights of refugees.

We cannot cover all aspects of refugee rights in our study, but limit ourselves to some of the issues addressed by article 12 of the UN International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which states that “everyone lawfully within the territory of a State shall, within that territory, have the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose his residence” and “everyone shall be free to leave any country, including his own.” Refugees must receive the same treatment as that accorded to aliens generally with regard to (among others) the right to choose their living place and to move freely within the country.

The situation we have been dealing with for several years makes it imperative that people’s attitudes towards refugees be examined. As this research project was launched in 2014, the extent of the refugee inflow was not yet known. Furthermore, the questions we wanted to answer were somewhat general. We wanted to explore how young people respond to claims that the government should guarantee political refugees’ freedom to travel and provide them with a decent standard of living. The data thus reflect a reaction of citizens outside a state of emergency.

1.2. Christian and Islamic Perspectives on Refugees

What influence on the attitude to refugee rights could now be expected from the Christian religion? Attention and care for people who are afflicted and in need is a central theme in Christian tradition. In the context of the New Testament, Matthew 25 is about the final judgement of God. In this judgement, God will separate people from each other as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats (25:32). Those who are blessed are characterized by several behaviors: “For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me” (25:35). Among all the behaviors that are highlighted as valuable in God’s sight is an empathetic attitude towards strangers. The standard for dealing with refugees is clearly stated: Jesus himself declares the love for his neighbor to be a commandment that transcends borders. The parable of the Good Samaritan (Lk 10:25) makes it clear that the stranger is not just a guest, but in him is Jesus himself.

The Catholic social doctrine emphasizes that refugees do not lose their human dignity or their rights as individuals (cf. Zaccaria et al. 2018). Pope Francis described the refugee crisis as the “worst disaster since the Second World War” and what the world never may forget is that the refugees are not just numbers, but people who seek help.2

As in many countries, the Catholic Church in Germany is involved in the social and pastoral accompaniment of refugees and takes this service for granted. That is why the Church acts diaconically through counseling agencies such as the Caritas, the Jesuit Refugee Service or Malteser Migrant Medicine, and through public statements and background discussions with political leaders and administration at all levels.3 The special focus of the refugee work is on the human encounter and personal accompaniment, but the Catholic Church also wants to provide refugees with housing, pastoral care, education, and things that can help their well-being.4 The Church feels committed to contributing to the integration of people of other cultural and religious characteristics (Ives et al. 2019).

Various issues were discussed at the Catholic refugee summits in 2015, 2016, and 2017. The main purpose of the summit in 2015 was to bring together practitioners who discussed concrete refugee aid initiatives and put forward proposals for the work of the Special Envoy on Refugee Issues. At the heart of the summit in 2016, was the question of what society and the church can do to help integrate refugees. In 2017, the statement “pastoral care for escaped people as a task for the entire church” was validated.

With this appeal, the summit made clear that the pastoral care for refugees should be expanded. According to Archbishop Heße (Hamburg), ‘it is our task to be present among people, in the places that know little freedom and much desperation. We must be present to proclaim and testify to God’s love. And we should help God to discover just where our comfort does not allow his presence’.5 Even though the connection between religion and charity has often been proven (Ziebertz 2018), it is also contested that religiousness can fuel prejudice and it is not only a source of empathic compassion (Deslandes and Anderson 2019).

What was said for the Catholic Church is no less applicable to the Protestant Church. The Protestant Church reminds all member states of the European Union to become aware of their obligation to take responsibility and to act accordingly. No refugee should face closed borders, especially in the face of winter. In addition, safe and legal ways for those seeking protection are to be created and the fight against the causes of flight reduced.6 All these decisions were made by the Protestant Church in Germany in its twelfth synod in November 2018. ‘God’s love is for the whole world and does not stop at national borders. All human beings live equally in God’s nearness and grace—regardless of skin colour, gender, nationality, religion and fortune.’ With this statement, the Protestant Church in Germany emphasizes that human rights apply to every human being, whether they are fleeing or not. According to Luther, we are ‘committed to charity to people, for’ a Christian is a free person and no one is subject. ‘So all Christians live freely in the unconditional love of God. At the same time, this determines the relationships between people. Because this freedom is also responsibility and committed to charity’.7

The Christian churches share the same roots and they refer to the same sources. Thus, the arguments are similar, such that the Orthodox Church also quotes the gospel and, with regard to the refugee problem, especially Matthew 25:35. The Christian Orthodox Church also actively helps with the reception of refugees, because active charity is understood as a corresponding act to the commandment of the Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. In addition, the majority of the faithful have a migrant background, which helps the faithful to understand the meaning of the welcome. The Christian Orthodox Church is of the opinion that the so-called ‘welcome culture’ must become an ‘integration culture’.8

We cannot present the positions of the Christian churches in all the countries where our study takes place. The large churches do not differ in their main orientation towards the Bible and arrive at similar interpretations, however they differ in their policies and practical help they give to refugees (Giordan and ZrinŠČak 2018). In any case, it should be noted that the Christian religion encourages its believers to be open, empathetic, and helpful to strangers. Whether this claim is reflected in the orientation of people will have to be tested empirically. If there is an influence, will it be all the greater the stronger the religious commitment and the more intense the religious practice is maintained?

This question applies identically to the Muslim respondents in our sample. According to Nur Manuty (2008) there are numerous indications in Islam that refugees are to be protected. He refers to the Quran, Sunnah, and the opinions of the ulama (scholars of Islam) ‘that from its very beginning, Islam has strongly provided for the protection for refugees’ (Nur Manuty 2008, p. 29). In the sources of Islam, the concept of fraternity has an important meaning, which is first of all fraternity among Muslims. Some Islamic theologians place fraternity in a wider context, which should not be in contradiction to fraternity within Islam. Muslims are expected to be attentive to refugees because that is part of Islam, according to the Prophet’s words that ‘you have to extend help to an oppressor and to the oppressed’ (Nur Manuty 2008, p. 27). Muslims should not refuse any request from any human being who seeks asylum and refugee status (Hamidullah 1977). By including young Muslims in this study, the evaluation of the findings must take into account that the number of Muslims among the world’s millions of refugees is very high. So, it could be that Muslims are particularly attentive to the rights of refugees.

1.3. National-Cultural Influence on Attitudes towards Refugee Rights

Socialization and education take place in a cultural environment. Socialization is a fundamental process of the appropriation of customs, values, ways of thinking, and behavior in a society. The more secularized societies are, the more religion and culture diverge and become independent of each other (Bruce 2002; Dobbelaere 2009). Religious socialization is a partial aspect of socialization. The more the culture in a society is shaped by religion, or rather by a religious community, the less distinction is made between culture and religion. In this case, religious socialization is often still a component of the general socialization as a matter of course (cf. Ziebertz 2009, 2017b).

In this study we compare countries where religion and culture form a different mélange. Among them are two African countries in which the implementation of religion into culture has special characteristics. There is a high level of religious activity in large parts of the population, and the difference between the colonial religion of Christianity and the traditional African religion is still significant. India is a multi-religious country where religious activity is high as well, with Hinduism as the dominant blend of religion and culture. Chile has experienced a long dictatorship and has been historically influenced by Catholicism. For the past 20 years, membership of the Catholic Church has been declining steadily, while Protestant free churches have been growing in popularity. Croatia, Poland, and Lithuania are traditionally Catholic countries. They have experienced communism as a state-imposed cultural form, whereby the church in Poland in particular has been able to maintain its strength during this period. In the meantime, clear signs of secularization are evident in all these countries, including Italy. In Germany and Switzerland, in line with the Reformation, Catholic and Protestant or Reformation traditions are strong, but in both countries both a religious pluralization and a crisis of the traditional churches can be observed. In this sense, the interdependencies between culture and religion are very different. For the European countries, the secularization process as de-institutionalization and loss of importance of traditional religions is a continuing phenomenon (Turner 2011; Martin 2005; Ziebertz and Riegel 2009). Its process is slower or faster in different countries, but mostly points in the same direction. The result is that national cultures are becoming more independent of religion and much of what constitutes culture can no longer be attributed to religious influences (Pope 2001; Anthony and Ziebertz 2012). Since the concept of multiculturalism has predominantly negative connotations, an increasing number of people and groups claims some sort of national identity. The question ‘What is British, American, Polish, Greek, Russian…?’ is intense and one that has certainly benefited populist parties (Albertazzi and McDonnell 2008). Today, one may state that the category “national” is of increasing importance and has a powerful impact on a type of shared identity (Miller 2000).

The concept of culture has so many sharply different definitions that a decision is needed (Hofstede 1984). Here culture is understood as a collective phenomenon that represents the common frame of reference of a human group: “patterns in a way of life”, as Eisenhart has pointed out (Eisenhart 2001, p. 210). Cultural knowledge can be experienced and communicated in groups and fulfils the function of expressing or defending one’s own social identity. It consists of shared meanings that can be part of the social identity of group members (Chiu and Hong 2006; Allen and Wilder 1979). Although the reality is that the idea of a unified culture—distinguishable over another—can no longer be maintained; at the same time, that this idea is now promoted is a fact that cannot be overlooked (Modood 2015).

The countries included in this study are characterized by considerable differences in history, culture, political regime, geography, etc. Although young people participate in global communication through Facebook and the Internet, this will probably not neutralize the national imprint of socialization. It is also likely that national origin and the discourses on refugees that are conducted in each country in its own way, influence their attitudes towards refugee rights.

2. Method

In this section we outline the method of the present study. For that purpose, we shall outline the conceptual model (Section 2.1), followed by the description of the samples (Section 2.2) and thirdly, a presentation of the instruments (Section 2.3).

2.1. Conceptual Model

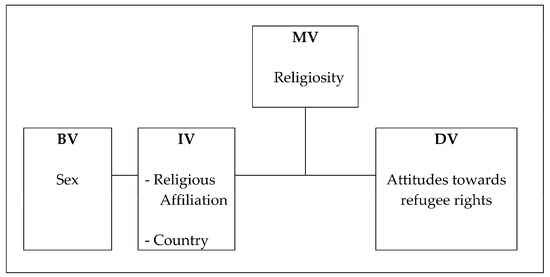

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model of the present study. We opted for an economical model that is limited to a few core concepts. A distinction is made between a background variable (BV), which is, in this case, sex and two independent variables (IVs) which are religious affiliation and country of origin. In addition to this, religiosity is included as a moderator variable (MV). Finally, the dependent variables (DVs)—the variables that we mainly want to explain—are the respondents’ attitudes towards refugee rights.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model. MV: moderator variable, BV: background variable; IV: independent variable; DV: dependent variable.

Above, we present good reasons for the assumption that the religious affiliation of the interviewees as well as their national-cultural background have an influence on their attitudes towards refugee rights. However, the influence of specific religious and cultural traditions depends on the extent to which people have acquired these traditions, their symbols, and narratives. The term religiosity, as used here, is an indicator of the subjective acquisition of a specific religious tradition, since according to the conceptualization of Glock and Stark (1965) it measures the commitment of individuals to a denomination in the dimensions of ideology, knowledge, practice, and experience. We therefore assume that differences in people’s religiosity moderate the influence of denomination and country of origin on attitudes towards refugee rights. Moreover, sex is included as a background variable to control for gender-specific differences in religiosity and attitudes towards refugee rights.

The paper addresses the following research questions:

- How do young people from different denominations evaluate refugee rights and does religiosity moderate the influence of religious affiliation on these attitudes?

- How do young people evaluate refugee rights differentiated by their country of origin and does religiosity moderate the influence of the country of origin on the attitudes towards refugee rights?

2.2. Samples

The data of the present study were gathered within the framework of the international empirical research project ‘Religion and Human Rights’.9 The aim of the project was to explore young people’s attitudes towards human rights and to measure the influence of religion on these attitudes. The survey was based on a standardized questionnaire designed by the international research group. The final version of the questionnaire was prepared in English and translated into the different languages by the national teams.

In this paper, two different samples are used. The question of whether the influence of religiosity differs between denominational traditions was examined for the German sample. This sample is characterized by different denominational traditions with a sufficient number of cases which allow for the necessary analyses. This sample is described below. Further, an international sample was used to examine whether the influence of religiosity differs between countries. Based on the results in the German sample and in order to keep the analysis as economic as possible, we decided to concentrate on Catholics and to choose only those countries with a minimum of 100 Catholics in the respective national sample. This international sample is also described below.

The German Sample

In Germany, data collection took place from spring 2013 to winter 2013/2014. The survey was conducted in 11 of Germany’s 16 federal states (in total 35 schools in 19 cities) and was implemented by paper and pencil interviews among high school students attending the 10th and 11th grades (students of about 16 years old) at different types of school. A total of 2157 students were interviewed. For the present analysis, we selected those students who belong to a denomination with a minimum of n = 100 in the sample. These students are Roman Catholics (n = 752), Protestants (n = 531), Pentecostals (n = 175), and Muslims (n = 106). We further included those students who considered themselves as ‘non-religious’ (n = 458). This selection resulted in a new sample size of n = 2022.

The percentage of female (53%) and male (47%) respondents is almost balanced in the sample. However, there are differences between the denominations which are significant (χ² (df = 4; n = 1988) = 30.5; p < 0.001). While the percentage of female and male respondents is very well balanced among the Protestants (female: 50%; male: 50%), there is a slight overrepresentation of female students among the Roman Catholics (female: 56%; male: 44%) and Muslims (female: 57%; male: 43%), and a clear overrepresentation of female students among the Pentecostals (female: 66%; male: 34%). Only among those students who considered themselves as ‘non-religious’, is a slight overrepresentation of male students found (female: 44%; male: 56%). These sample characteristics give further reasons to control for sex in the analysis.

Significant differences are also found regarding respondents’ religiosity. In the German sample, the mean of religiosity is 2.53 (on a five-point scale) with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.98. However, significant differences are observable between female (mean = 2.62; SD = 0.94) and male (mean = 2.42; SD = 1.00) respondents (t-test: t (1948) = 4.638, p < 0.001) as well as between the considered denominations. Among them, the Muslim students show the highest religiosity (mean = 3.81; SD = 0.82); they differ significantly from all other denominations, followed by the Pentecostals (mean = 2.77; SD = 1.11), Roman Catholics (mean = 2.71; SD = 0.87), and Protestants (mean = 2.63; SD = 0.83) building a homogenous subgroup and the “non-religious” (mean = 1.66; SD = 0.62) who also differ significantly from all the others (ANOVA: F (4) = 176.52, p < 0.001).

The International Sample

To analyze differences between countries regarding the influence of religiosity, we selected those countries from the international dataset of the ‘Religion and Human Rights’ project with a minimum of n = 100 Catholics in the respective samples. These countries are Croatia (n = 1097), Italy (n = 762), Germany (n = 752), Poland (n = 704), Chile (n = 497), Nigeria (n = 436), India (n = 387), Tanzania (n = 316), Lithuania (n = 241), and Switzerland (n = 171), resulting in a total sample size of n = 5363. The data collection in those countries took place between 2013 and 2016 and was implemented either via an online survey or by paper and pencil interviews of school and university students. Therefore, the respondents’ age ranges from 14 to 27 years (although 92.6% are between 15 and 19 years old). Although the age span here is larger than in the German sample, both the school and the university students surveyed can be assigned to a common life span, namely adolescence, since they are in transition to adulthood. Today, this development process is often first completed when they enter working life (Fend 2003). Nevertheless, in further analyses we will check whether age differences between the respondents have significant effects. The national samples are not random and the method of selecting the samples varies between the countries.

Female respondents (57%) are somewhat overrepresented in the international sample compared with male respondents (43%). The percentage of female and male respondents is only well balanced in the Chilean (female: 52%; male: 48%) and the Indian (female: 50%; male: 50%) subsamples, while there is a slight overrepresentation of female respondents in the Lithuanian (female: 59%; male: 41%), German (female: 56%; male: 44%), Italian (female: 59%; male: 41%), and Swiss (female: 56%; male: 44%) subsamples. There is a clear overrepresentation of female respondents in the Croatian (female: 64%; male: 36%), Polish (female: 62%; male: 38%), and Nigerian (female: 63%; male: 37%) subsamples. By contrast, male respondents are overrepresented in the Tanzanian subsample (female: 34%; male: 66%). These differences between the countries are significant (χ² (df = 9; n = 5345) = 119.3; p < 0.001).

In addition, significant differences regarding the respondents mean age were found between the countries (ANOVA: F (9) = 558.21, p < 0.001). However, the respondents’ age was not found to have a significant influence on the examined attitudes, so we excluded this variable from the analyses.

Significant differences between the countries were also found regarding respondents’ religiosity (ANOVA: F (9) = 221.28, p < 0.001). Among them, the Nigerian (mean = 4.43; SD = 0.49) and Tanzanian (mean = 4.41; SD = 0.45) respondents, which build a homogenous subgroup, show the highest religiosity, followed by respondents from India (mean = 3.98; SD = 0.78) and together in one subgroup, Poland (mean = 3.77; SD = 0.85) and Croatia (mean = 3.68; SD = 0.86). These are followed by a subgroup consisting of respondents from Chile (mean = 3.43; SD = 0.88) and Italy (mean = 3.28; SD = 0.87) and, finally, a subgroup of respondents from Lithuania (mean = 2.87; SD = 0.89), Germany (mean = 2.71; SD = 0.87), and Switzerland (mean = 2.67; SD = 0.98).

2.3. Instruments

The scales used to measure the dependent and the independent variables of the conceptual model are outlined below. The empirical inquiry was developed from the research network ‘Religion and Human Rights’. For further information on the instruments we refer to the corresponding publications.10

2.3.1. Attitudes towards Refugee Rights

Attitudes towards refugee rights were measured by two items which show an acceptable internal consistency in the German sample (α = 0.70) and in the international sample (α = 0.68). They read as follows:

The government should guarantee political refugees the freedom to travel.

The government should provide a decent standard of living for political refugees.

The respondents were asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement with these statements on a five-point scale. They could choose between the following categories: ‘I totally disagree’ (1), ‘I disagree’ (2), ‘I am not sure’ (3), ‘I agree’ (4), and ‘I totally agree’ (5).

2.3.2. Religiosity

Religiosity was measured by the five-item version of the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS) (Huber and Huber 2012). This scale measures religiosity as a multidimensional construct, whereby ‘the five core-dimensions [of religiosity, which are the intellectual dimension, the dimension of ideology, public practice, private practice, and experience] can be seen as channels or modes in which personal religious constructs are activated’ (Huber and Huber 2012, p. 713). The items are:

- How often do you think about religious issues? (five-point scale from 1 (‘never’) to 5 (‘very often’))

- To what extent do you believe that God or something divine exists? (five-point scale from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘very much so’))

- How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God or something divine intervenes in your life? (five-point scale from 1 (‘never’) to 5 (‘very often’))

- How often do you pray? (eight-point scale from 1 (‘never’) to 8 (‘several times a day’))

- How often do you take part in religious services at a church or mosque or another place? (six-point scale from 1 (‘never’) to 6 (‘more than once a week’))

According to the instructions from Huber and Huber (2012, p. 720), the two items measuring the dimension of public and private practice were recoded, so that all five items range in their values from 1 to 5. The items have a good internal consistency both in the German (α = 0.86) and the international (α = 0.85) sample.

3. Results

In this section we present the results of the empirical analyses, which concern the German sample in the first part and the international sample in the second part.

The first part contains analyses carried out to answer the first research question. First, we conducted frequency analyses to see how young people from different denominations evaluate refugee rights. Secondly, we conducted an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis with main effects and interaction effects to analyze whether religiosity moderates the influence of religious affiliation on attitudes towards refugee rights (Section 3.1).

In the second part, we answer the second research question. Therefore, we carried out analogue analyses, but with the data of Catholic respondents from the international sample. First, we conducted frequency analyses to see how young people from different countries evaluate refugee rights. Secondly, we conducted an OLS regression analysis with main effects and interaction effects to analyze whether religiosity moderates the influence of the country of origin on attitudes towards refugee rights (Section 3.2).

3.1. The Impact of Religious Affiliation on Attitudes towards Refugee Rights

To answer the first research question—How do young people from different denominations evaluate refugee rights?—we present the mean and standard deviation of attitudes towards refugee rights for each denomination separately.

Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviation. The acceptance of refugee rights is weak to moderately positive. A mean above 3.00 indicates an acceptance on the average, although the closeness of some values to the scale center mirrors a kind of ambivalence. The mean ranges from 3.25 for Roman Catholic to 3.67 for Muslim respondents. The standard deviation indicates that some respondents rejected the statements in the items.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) of attitudes towards refugee rights by denomination.

The second part of the research question contains the issue of moderation effects. We are interested in whether religiosity moderates the influence of religious affiliation on attitudes towards refugee rights. Thus, we computed an OLS regression with interaction effects. The results of this regression analysis are presented in Table 2. The analysis includes religiosity, denomination, and sex, as well as the interactions between religiosity and denomination as independent variables in the model. We decided to use Roman Catholic as reference category here because they showed the lowest acceptance of refugee rights (see Table 1). According to this decision, the results must be interpreted always in relation to Catholics.

Table 2.

The influence of religiosity, religious affiliation, sex, and the interaction between religiosity and denomination on attitudes towards refugee rights (ordinary least squares (OLS) regression).

Table 2 shows the influences (beta coefficients) of religiosity, religious affiliation, and sex on attitudes towards refugee rights. According to this analysis, religiosity has a small but significant positive influence on attitudes towards refugee rights (beta = 0.124). Since we included interaction effects in the model, the influence of religiosity presented here applies only to Roman Catholics. We also see that the differences between religious denominations, documented in Table 2, do not reach the limits of significance in the regression analysis. Only the non-religious respondents show a significantly higher acceptance of refugee rights compared to the Roman Catholics (beta = 0.189). Furthermore, there are significant sex differences which indicate that female respondents show a higher acceptance of refugee rights than male respondents (beta = 0.106).

However, the question of whether a certain affinity to a denomination—indicated by individual religiosity—moderates the effect of merely belonging to this tradition can be answered based on the interaction effects. Table 2 shows that there are no significant interaction effects, which means that there is no evidence for the assumption that differences in people’s religiosity moderate the influence of denomination on attitudes towards refugee rights—at least in the German context.

3.2. The Impact of National Context on Attitudes towards Refugee Rights

In the first part of this paper we discussed that differences between national contexts could be more important than denominational differences regarding the acceptance of refugee rights, as other studies have shown (Webb et al. 2012; Unser et al. 2016; Ziebertz 2017b). Further on, religiosity can be an important moderator in national contexts that differ from Germany. To test these assumptions, we conducted analyses with the international sample and concentrated on the Roman Catholic respondents in the 10 countries. This focus can also be justified from a theological point of view, since the Roman Catholic Church and its teachings claim to be universally valid in every national context. Being Catholic and belonging to this Church should accordingly diminish differences between the national context—at least in this logic.

To answer the question—How do young Roman Catholics from different countries evaluate refugee rights? (research question 2)—we present the mean and standard deviation of attitudes towards refugee rights for each country separately. Table 3 shows the mean and standard deviation. The evaluation of refugee rights by Roman Catholic youths ranges from slight rejection in Poland (mean = 2.83) to indecision in Lithuania (mean = 2.93), Croatia (mean = 2.97), and Italy (mean = 3.07) to a moderate acceptance in Chile (mean = 3.14), Switzerland (mean = 3.18), Tanzania (mean = 3.22), India (mean = 3.24), and Germany (mean = 3.25). Nigerian Catholics, however, differ from the other respondents in their clear acceptance of refugee rights (mean = 3.81).

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) of attitudes towards refugee rights by country.

To analyze whether these differences are significant and whether religiosity moderates the influence of the national context on attitudes towards refugee rights (research question 2), we computed an OLS regression with interaction effects. The results of this regression analysis are presented in Table 4. The analysis includes religiosity, country of origin, and sex, as well as the interactions between religiosity and country of origin as independent variables in the model. We decided to use Nigeria as a reference category here because the Roman Catholic youths from this country showed by far the highest acceptance of refugee rights (see Table 3). According to this decision the results must be interpreted always in relation to Nigeria.

Table 4.

The influence of religiosity, country, sex, and the interaction between religiosity and country on attitudes towards refugee rights (OLS regression).

Table 4 shows the influences (beta coefficients) of religiosity, country of origin, and sex on attitudes towards refugee rights.11 The analysis shows that religiosity has a significant, positive influence on attitudes towards refugee rights (beta = 0.227). Since we also included interaction effects in the model, the influence of religiosity presented here applies only to the Roman Catholics in Nigeria. We also see that there are significant differences between Nigeria and other countries. Nigeria differs significantly from Chile (beta = −0.110), Croatia (beta = −0.216), India (beta = −0.88), Italy (beta = −0.175), Lithuania (beta = −0.121), and Poland (beta = −0.249), but not from Germany, Switzerland, and Tanzania. Furthermore, there are significant sex differences which indicate that female Roman Catholics show a slightly higher acceptance of refugee rights than male Roman Catholics (beta = 0.056).

The question of whether religiosity moderates the effect of the national context can be answered on the basis of the interaction effects. Table 4 shows that there is only one significant interaction effect. Only in Chile, a small, negative interaction effect (beta = −0.069) is found which means that the more the Catholic respondents in Chile are committed to their religion, the more they are skeptical towards refugee rights.

4. Discussion

Migration usually has its causes in economic crises or war and violence. People repeatedly make their way to Europe because they want to escape the economic misery in their home country. In the past decades, the two Gulf wars, the war against the Taliban in Afghanistan and, more recently, the violence in North Africa and the war in Syria have triggered a large influx of people seeking refuge and security. Dramatic scenes have taken place especially at the European external borders and many refugees have died on their way to supposed freedom. The political handling of this situation was and is embarrassing for Europe, which seems to ignore its own values. National and international debates are stirred up by this and the refugee issue is a public issue both in those countries that are committed and in those that refuse to take responsibility. This debate permeates politics, law, culture, and education; it runs through politics, law, culture, and education, and the young people who took part in the research hear and know the arguments and formed their own opinion.

In this study we wanted to research: How do young people from different denominations and in different countries evaluate refugee rights? The results show that there is in most denominations and most countries a slight approval; a little more than just an ambivalent positive attitude, but in no case is it a convinced consent.

Close to the average are young people who either have a Protestant confession or who are non-religious. Members of a Protestant Free Church show less approval than the average, but the approval of Catholics is lowest. It reflects at best an ambivalent positive attitude, but there is also a group whose approval is clearly above average, namely, the Muslim interviewees. It may be that the stronger empathy is motivated by the Muslim faith, it also can be assumed that the higher value among Muslims is related to the fact that many migrants from the crisis areas indicated are Muslims, so that the agreement expresses empathy for one’s own religious group. However, the differences between the religious communities are of no significance and should therefore not be used for far-reaching conclusions. Differences in religiosity do not moderate the influence that religious affiliation has on attitudes to refugee rights.

We further researched: Does the country of origin have any influence on attitudes towards refugee rights? To this end, we discussed the possibility that both religion and nationality are capable of forming group identities. People identify themselves with certain groups (reference group) and by doing so they distinguish between one’s own group and those who do not belong to it. A reference group can be a group of people of the same nationality, whereby in this case nationality is so important that social or cultural differences within the nation do not count as identity markers. A reference group can also be a religious community, where religious identity extends to people who live scattered in many countries but share the same faith. Other aspects such as nation, language, etc. do not appear as identity markers in this case. But how are nation and religion interwoven? We assumed that there are strong differences in the extent to which religion and national culture are identical, partially connected or separated: the greater the degree of secularization, the greater the difference between culture and religion. When religion and culture coincide, no differences can be measured; when they diverge, the question is which group identity is more important.

Regarding religious affiliation we have chosen a religious group that has a particularly pronounced dogmatism and continues to assert an absolute claim to truth: the Roman Catholic Church. Although the Roman Catholic Church does not claim catholicity alone, it finds that it realizes catholicity in the most adequate way (cf. Lumen gentium 8 (Lumen Gentium 1964); encyclical letter Ut unum sint (Ut Unum Sint 1995)). A religious community which understands group identity as clearly as the Roman Catholic Church as part of its spirituality, which itself understands the church not only as an instrument for attaining salvation but also as a content of faith, could be able to develop a strong corps spirit.

If that were the case, could this corps spirit perhaps even be stronger than identification with a national culture? The empirical findings do not support this assumption. First of all, we were able to establish that the assessment of refugee rights already varies considerably between Catholic interviewees from the 10 countries. There was a slight rejection from Polish Catholics, which could mean that the respondents follow the line of the government, which has a negative attitude towards the welcoming of refugees, and that the voice of the Church, which is rather weak anyway, does not counteract this. The respondents from eight of the ten countries show an ambivalent attitude, neither rejecting nor agreeing. Only Catholics from Nigeria are clearly positive. Between them and the Polish interviewees lies one point on the five-point scale. In view of the religious foundations, which leave no doubt that Christians should take a caring attitude towards strangers, this finding is sobering. Reasons for this may be that church membership is a formal criterion that says nothing about the strength of the commitment, or that respondents differ from the church’s opinion on this point, or that the local churches place too little emphasis on commitment to refugees, or that it is precisely the political discussion that influences attitudes most, which in almost all countries is marked by conflict, restraint or even rejection—even in countries that host many people.

We found that Catholics from Nigeria agree most strongly with refugee rights, and in the analysis of which interviewees from which countries differ most from Nigerians, we found Poles, followed by Croatians, Italians, and in fourth place, Lithuanians. All four countries have a strong Catholic tradition and in these countries the debate on refugees is polarized. It seems that the opinions of young people reflect above all their country of origin. This is especially reflected by the fact that individual religiosity does not moderate the influence of country of origin—with the exception of Chile. Here it must be taken into account that although the Catholic Church sees itself as a world-church, it also or primarily appears as a local church. It is thus integrated and part of the arena of discourse that takes place in a state. As a largely domesticated church in the context of secularization, it does not have the power to generate an opposing attitude on refugee issues.

In summary, the finding of this research is that membership in a religious community has little influence on attitudes towards refugee rights. In contrast, when considering the different countries, larger significant differences are found. As far as the respondents’ religiousness is concerned, this neither reinforces nor weakens the influence that religious affiliation has on their attitudes. This also applies, except for Chile, to the influence on the country’s effect.

Of course, at the end of this study caution is advisable. We included only a few instruments in the analysis and ignored many parameters that would need to be examined for their effects in further analyses. The results are therefore of limited validity. The limitations of this study mainly concern methodological issues, which are due to the fact that the data analyzed here were collected in the context of a research project that focused on attitudes towards a wide range of human rights, but not on refugee rights in particular. Therefore, the measurement of attitudes towards refugee rights was based on only two points concerning the issues of freedom of travel and adequate living standards. The rights of refugees are of course more extensive, and other aspects should be researched more carefully in the future.

Another limitation concerns the age of the respondents, which was between 14 and 27 years. Since, as is well known, religiosity is linked to age, the impact of religiosity on attitudes to refugee rights may be different when interviewing older people, for example. However, such an explorative approach is necessary for the development of future research questions and hypotheses.

Author Contributions

A.U. (Method, Results, Discussion), H.-G.Z. (Introduction, Discussion). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Albertazzi, Daniele, and Duncan McDonnell. 2008. Twenty-First Century Populism: The Spectre of Western European Democracy. New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Vernon L., and David A. Wilder. 1979. Group categorization and attribution of belief similarity. Small Group Behavior 10: 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, Francis-Vincent, and Hans-Georg Ziebertz, eds. 2012. Religious Identity and National Heritage. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Steve. 2002. God Is Dead: Secularization in the West. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Chi-Yue, and Ying-Yi Hong. 2006. Social Psychology of Culture. New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deslandes, Christine, and Joel R. Anderson. 2019. Religion and Prejudice toward Immigrants and Refugees: A Meta-Analytic Review. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 29: 128–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbelaere, Karel. 2009. The Meaning and Scope of Secularization. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Edited by Peter B. Clarke. Oxford: University of Oxford Press, pp. 599–615. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhart, Margaret. 2001. Changing Conceptions of Culture and Ethnographic Methodology: Recent Thematic Shifts and Their Implications for Research on Teaching. In Handbook of Research on Teaching. Edited by Virginia Richardson. Washington: American Educational Research Association, pp. 209–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fend, Helmut. 2003. Entwicklungspsychologie des Jugendalters, 3rd ed. Wiesbaden: VS. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, Peter. 2004. The refugee crisis and fear: Populist politics and media discourse. Journal of Sociology 40: 321–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, Thomas. 2011. Access to Asylum: International Refugee Law and the Globalisation of Migration Control. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giordan, Giuseppe, and Siniša ZrinŠČak. 2018. One pope, two churches: Refugees, human rights and religion in Croatia and Italy. Social Compass 65: 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, Charles Y., and Rodney Stark. 1965. Religion and Society in Tension. Chicago: McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Hamidullah, Muhammad. 1977. Muslim Conduct of State. Lahore: Sheikh Muhammad Ashraf, p. 197. [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway, James C., and Michelle Foster. 2014. The Law of Refugee Status. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1984. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverley Hills: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Stefan, and Odilo Huber. 2012. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS). Religions 3: 710–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, Nicole, Jill Witmer Sinha, and Ram Cnaan. 2019. Who Is Welcoming the Stranger? Exploring Faith-Based Service Provision to Refugees in Philadelphia. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 29: 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Klepp, Silja. 2010. A Contested Asylum System: The European Union between Refugee Protection and Border Control in the Mediterranean Sea. European Journal of Migration and Law 12: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneebone, Susan Y. 2010. Refugees and displaced persons. The refugee definition and ‘humanitarian’ protection. In Research Handbook on International Human Rights Law. Edited by Sarah Joseph and Adam McBeth. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 215–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lumen Gentium. 1964. Dogmatic Constitution on the Church. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19641121_lumen-gentium_en.html (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Martin, David. 2005. On Secularization. Towards a Revised General Theory. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, David. 2000. Citizenship and National Identity. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Modood, Tariq. 2015. Multiculturalism. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Nationalism. Chichester: The Atrium, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nur Manuty, Muhammad. 2008. The Protection of Refugees in Islam: Pluralism and Inclusivity. Refugee Survey Quarterly 27: 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, Robert. 2001. Religion and National Identity. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Bryan S. 2011. Religion and Modern Society. Citizenship, Secularisation and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- U-Minn. 2003. University of Minnesota Human Rights Center. Study Guide: The Rights of Refugees. Available online: http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/edumat/studyguides/refugees.htm (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Unser, Alexander, Susanne Döhnert, and Hans-Georg Ziebertz. 2016. The influence of the socio-cultural environment and personality on attitudes towards civil human rights. In Freedom of Religion in the 21st Century. Edited by Hans-Georg Ziebertz and Ernst Hirsch Ballin. Leiden: Brill, pp. 130–61. [Google Scholar]

- Unser, Alexander, Susanne Döhnert, and Hans-Georg Ziebertz. 2018. Attitudes towards Refugee Rights in Thirteen Countries. A Multi-level Analysis of the Impact and Interaction of Individual and Socio-cultural Predictors. In Political and Judicial Rights through the Prism of Religious Belief. Edited by Carl Sterkens and Hans-Georg Ziebertz. Cham: Springer, pp. 275–302. [Google Scholar]

- UN. 1951. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/protection/basic/3b66c2aa10/convention-protocol-relating-status-refugees.html (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Ut Unum Sint. 1995. Encyclical letter by Pope John Paul II. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_25051995_ut-unum-sint.html (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Webb, Raymond J., Hans-Georg Ziebertz, Jack Curran, and Marion Reindl. 2012. Human rights among Muslims and Christians in Palestine and Germany. In Tensions within and between Religions and Human Rights. Edited by Johannes A. van der Ven and Hans-Georg Ziebertz. Leiden: Brill, pp. 177–201. [Google Scholar]

- Zaccaria, Francesco, Francis-Vincent Anthony, and Carl Sterkens. 2018. Religion for the Political Rights of Immigrants and Refugees? An Empirical Exploration among Italian Students. In Political and Judicial Rights through the Prism of Religious Belief. Edited by Carl Sterkens and Hans-Georg Ziebertz. Cham: Springer, pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ziebertz, Hans-Georg. 2009. The Impact of Culture on Religiosity. An empirical study among youth in Germany and The Netherlands. In Secularization Theories, Religious Identity and Practical Theology. Edited by Wilhelm Gräb and Lars Charbonnier. Münster: LIT, pp. 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ziebertz, Hans-Georg. 2017a. Beliefs and Refugee Rights: Empirical Research among Youth in Italy and Germany. Religioni e Societá 87: 59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ziebertz, Hans-Georg. 2017b. The Impact of Religious and National Belonging on Attitudes Concerning the Social Importance of Religion: A Cross-Cultural Explorative Empirical Analysis. Journal of Empirical Theology 30: 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziebertz, Hans-Georg. 2018. Religious commitment and Empathic Concern. An Empirical Study of German Youth. Journal of Empirical Theology 31: 239–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziebertz, Hans-Georg, and Ulrich Riegel. 2009. Europe: A Post-secular Society? International Journal of Practical Theology 13: 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The data originated from the international research program “Religion and Human Rights” (2012–2019). See: http://www.rhr.theologie.uni-wuerzburg.de. |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | See footnote 1. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | In a further analysis, we included age as an additional predictor in the model. Compared to the original model, no significant changes in beta values were found. In addition, the proportion of the explained variance increased by only 0.2%, which is why we only document the original model here. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).