Enlightenment on the Spirit-Altar: Eschatology and Restoration of Morality at the King Kwan Shrine in Fin de siècle Seoul

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Enlightenment and Civilization

When Kim Okkyun 金玉均 (1851–1894) visited the Prime Minister Pak Kyusu, Pak took a globe of the earth, which his grandfather, Sir Yŏnam 燕巖 (i.e., Pak Chiwŏn朴趾源) had brought after traveling to China, out of his closet and showed it to Kim. Turning the globe, Pak told Kim with a smile, “Where is the Central State (中國: i.e., China) now? If you turn it that way, the US is the center. Turn it this way, Chosŏn is the center. If every state becomes the central one, where is the fixed Central State today?” Although Kim read about new thoughts and claimed Enlightenment, he had been captured by hundreds of years of an idée fixe that the state located in the center is China; cardinal states placed its East, West, South, and North are four barbarians; thus, it is taken for granted that the four should worship China. He had never dreamt of going further and maintaining the independence of his state. Enlightened greatly by what Pak said, Kim slapped his knee and stood up. The Kapsin [1884] Regime Change was brought out at the end.(Shin Ch’ae-ho, “The Influence of Copernican Theory,” quoted in NIKH 1999, p. 18)

The two men quietly organized a party among their young friends for the purpose of studying the history, customs and geography of the Western countries and the name of Kaiwha [dang] or Progressive Party was coined in the Korean language. During the year 1880 the two pioneers of Western education secretly went to Japan with the permission of His Majesty and took with them some twenty young men to study the outside world.(Giacinti, 4 September 1897)

We can expect the age of Enlightenment and the days of Great Peace within the near future. Isn’t it truly an excellent method to transform people and develop the culture, as well as the foremost strategy to promote beneficial utility and prosperous livelihoods?(SJW 1882-8-28)9

開化之期, 昇平之日, 可翹足而待也. 玆非化民成俗之妙法, 利用厚生之首謀乎?

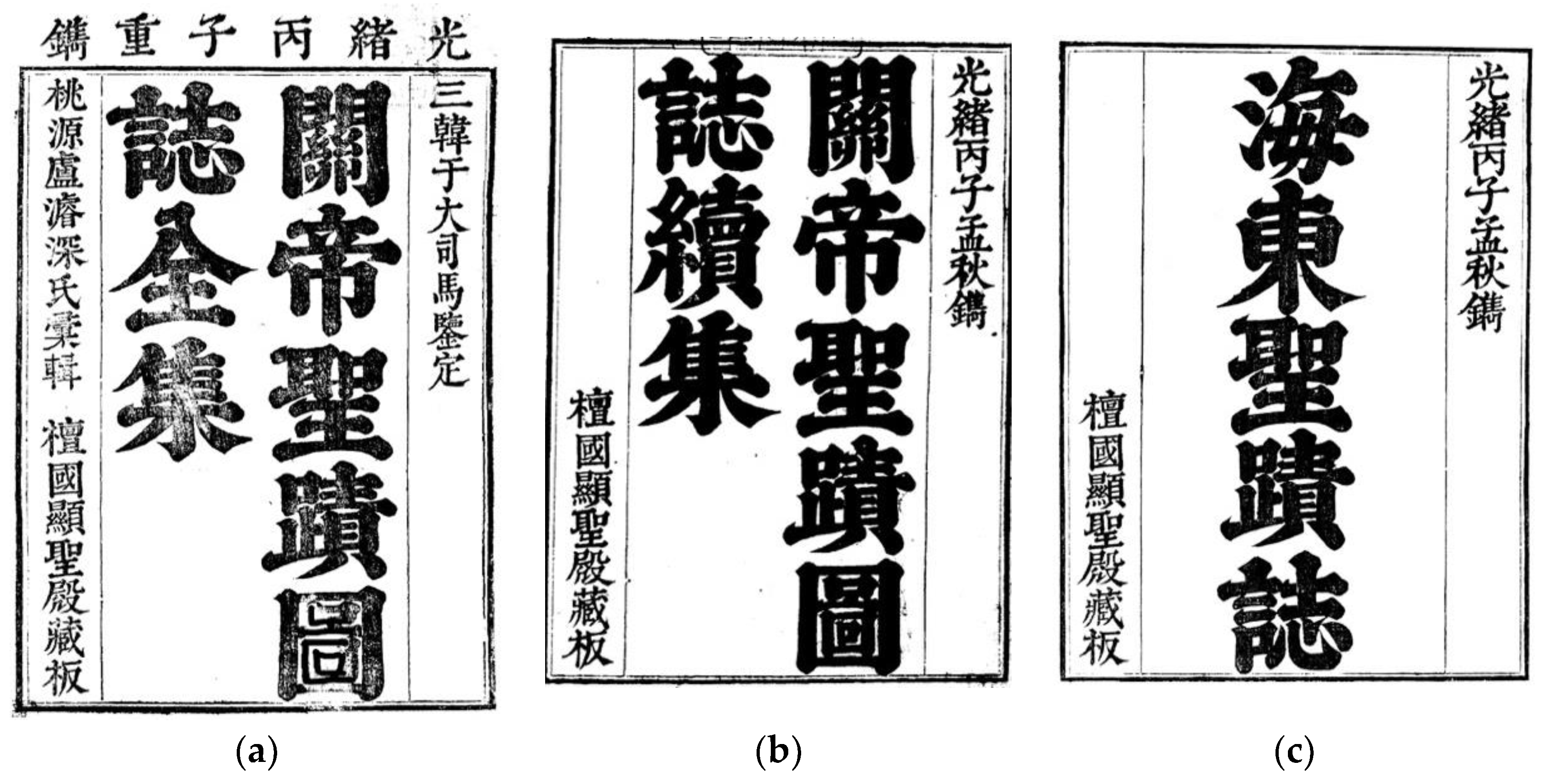

3. Spirit-Writing and Publication of the Scriptures of Thearch Kwan

The former general of the Han Dynasty, Marquis Kwan (kwanhu/guanhou 關侯), whose posthumous title is the Majestic and Sublime, became a King and a Thearch, with many honorable titles bestowed [from Chinese Emperors], so that he was worshipped in both Daoism and Buddhism, called as a Lord Thearch, a Heavenly Worthy, and a Bodhisattva.(KJ 1876, vol. 1, 1a)

漢前將軍關侯諡壯繆, 歷代屢加封典, 爲王爲帝, 而以至道釋二家, 亦俱崇奉, 稱帝君稱天尊稱菩薩.

4. Spirit-Writing of the Three Sages and Enlightenment

4.1. The Kwanwang Shrines and the Related Figures

4.2. The Three Sages and Revelations

[1879-9-13] (Instruction in the dream of Kim Hŭijŏng).

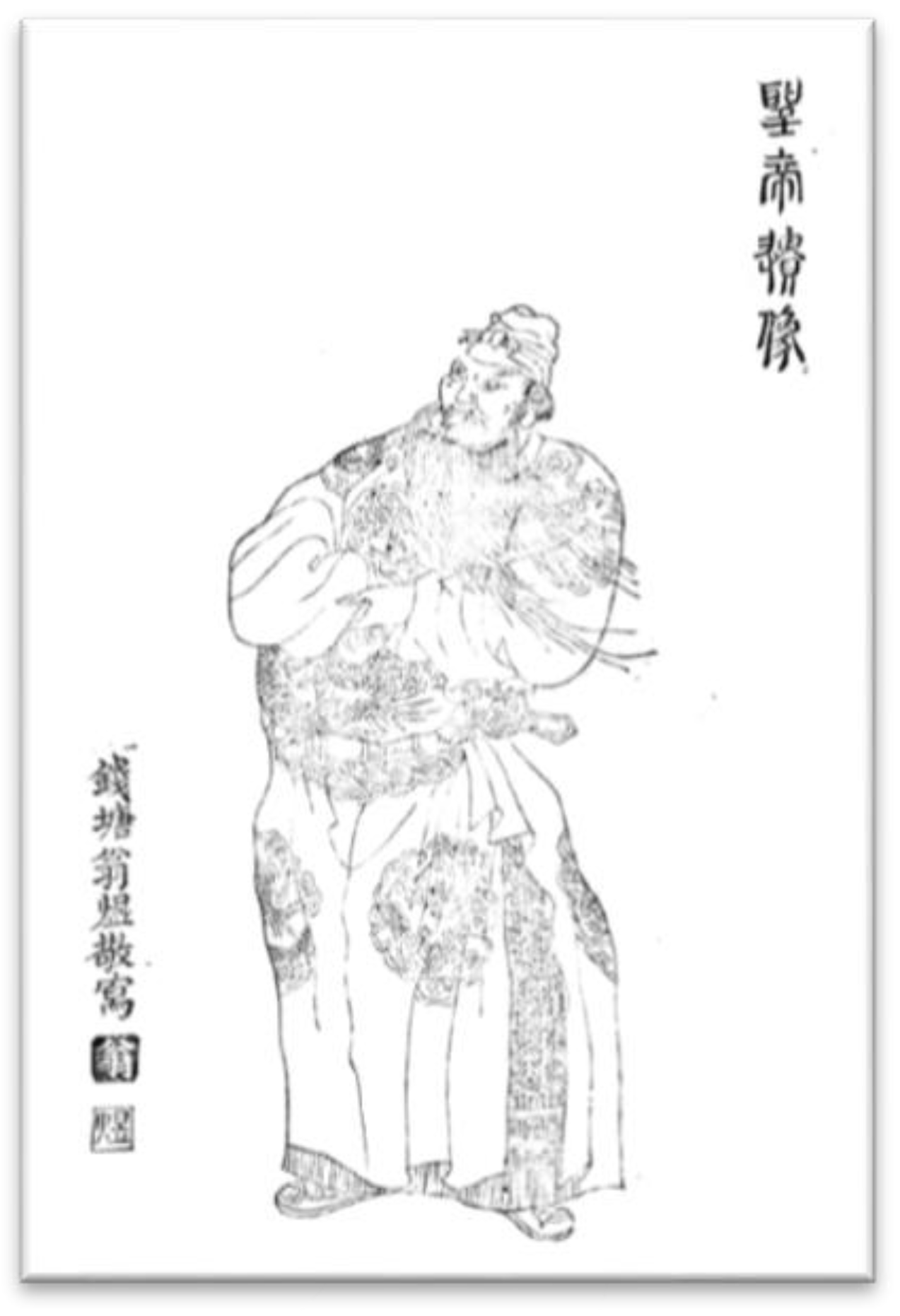

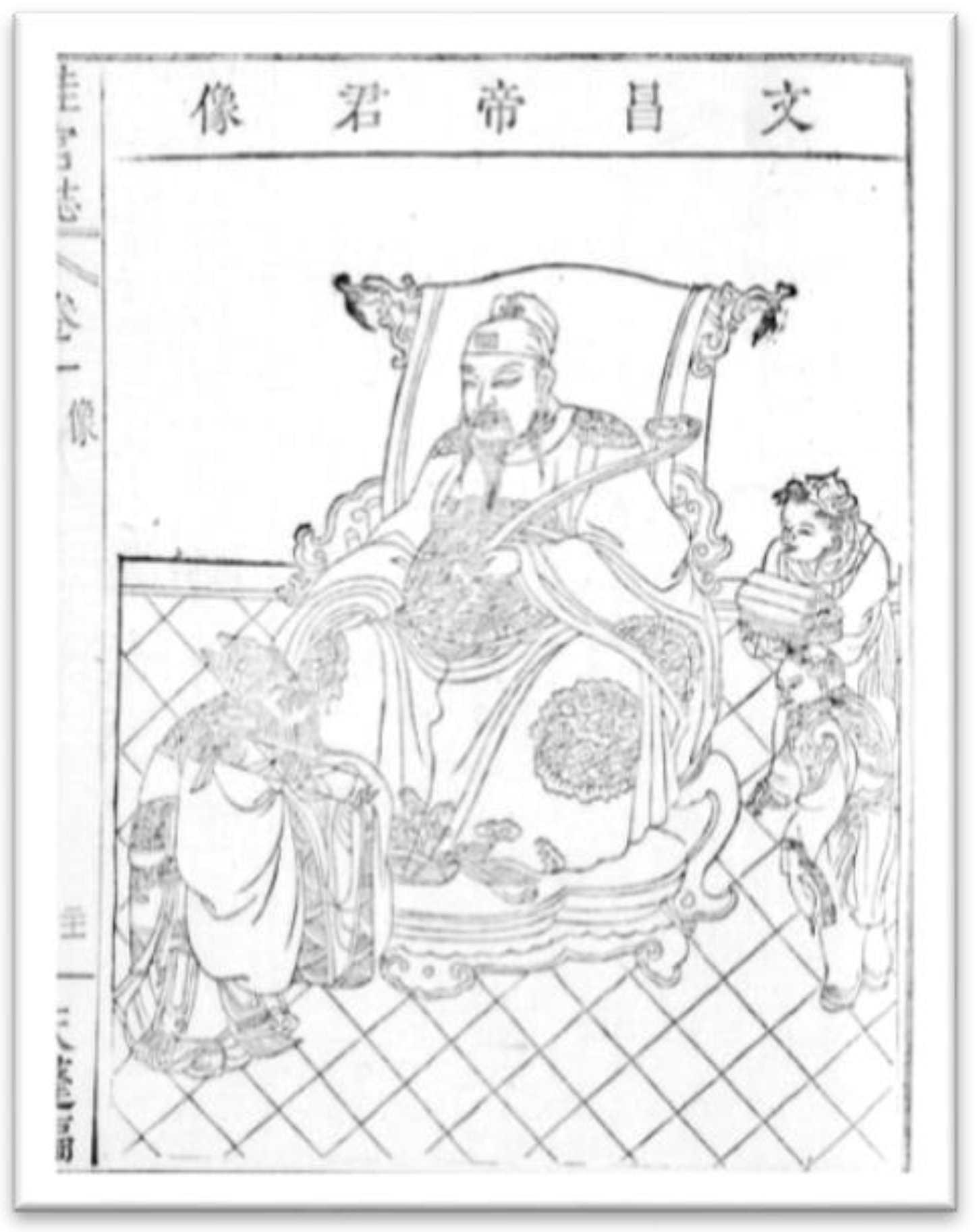

The Sacred Thearch [Kwan] descended and instructed: “Did you look into the divine color of the Thearch of Literature in detail?” I replied that I had respectfully looked into it more closely. Then [the Thearch] gave me a plate. I reverently looked up, and [its surface] was multicolored and had a red spot in the middle. [The Thearch] gave another plate. I saw it was red-colored and had a black spot in the middle. Shortly afterward, the Thearch gave an instruction: “The divine colors are just like that.” I received the instruction.

The Sacred Thearch instructed: “Disciple Yi, use the portraits of Thearchs of Literature and Succour as they are. The most critical thing is to take the style of old versions. Then, you should describe completely according to what you’ve seen of the divine colors.”.(SGJ, 52b-53b)

九月十三日(金熙鼎夢敎) 聖帝下敎曰, “爾果詳瞻文昌帝君神色耶?” 以詳細仰瞻對奏, 則下賜接匙一箇, 奉瞻則着彩而中點臙脂者也. 又下賜接匙一箇, 又奉視則着石磵朱而中點墨色者也. 仍下敎曰, “神色若此也.” 承敎. 聖帝敎曰, “李某, 仍用文昌帝・孚佑帝影帖, 以舊本之意最緊, 則一從爾之仰瞻神色圖寫.”

I admonish you by descending edict, for I am desperate for the task of Enlightenment.

降乩之諭, 予切開化之事也.(SGJ 1878-12-27, 37b)

The constant ethical standard has been violated and transgressed. Thus, I entrusted Yi Chinsun and others with [the task of enlightening and] transforming this world into the state of the Jewel Mountain.(SGJ 1880-2-10, 63b)

倫常乖舛. 故我托於李瑨等, 此世化爲寶山之境.

The mandate that I received from the Highest Thearch [the Jade Emperor] is the edict to manifest myself in this world and broaden the enlightenment-transformation [to all beings] in the air and in the water. Thousands and millions of my sayings come from the two words, “constant morality.”(SGJ 1880-8-3, 74a)

吾之所奉上帝勅命, 諭顯此世, 敷化飛潛. 千萬其言, 皆由此倫常二字中也.

5. Daoist Eschatology and Publication of Morality Books

5.1. Apocalypse and Salvific Enlightenment

[The True Writs of] Five Ancients of the Primordial Beginning written in Red Script on Jade Tablets emerged spontaneously from the midst of cavern-like emptiness (i.e., the Dao). It generated the sky and established the earth, and enlightened the luminous spirits [of all being].(DZ22, vol. 1, 2b)

元始五老赤書玉篇, 出於空洞自然之中, 生天立地, 開化神明.

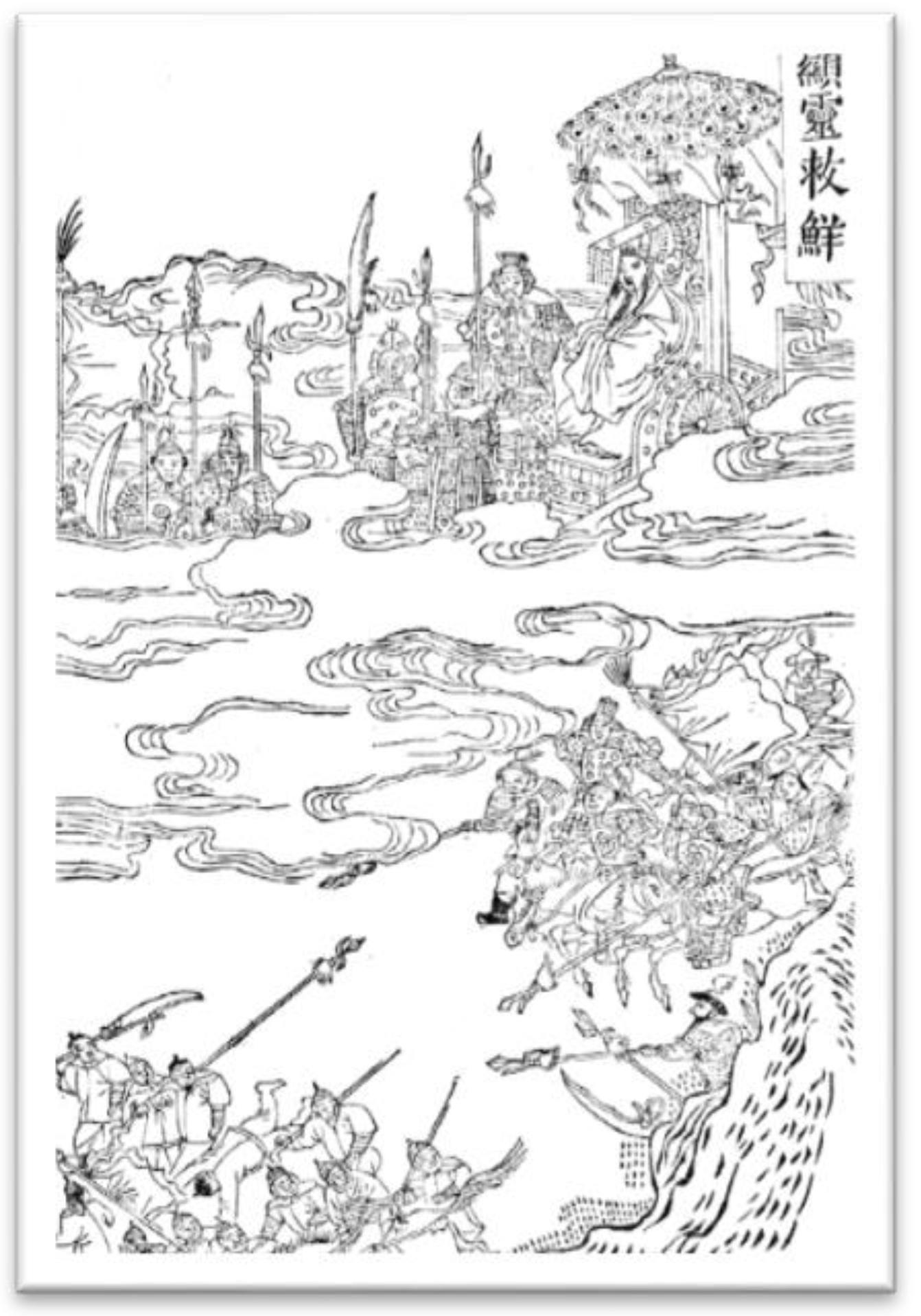

Recommended highly by the Heavenly Mandate, my position was elevated to the Golden Gate. I usually take a stroll in the Purple Void heaven and fly my spirit for visits and inspections [on the human world]. However, I descended on earth increasingly as the world changed. [Human world] is full of moral degradation, greed, shallowness, and deceit. It is harder to extinguish them all, even when the catastrophe of kalpa is about to occur. Thus, I manifest myself and enlighten through the phoenix [of spirit-writing].(JY255, 91b)

余以天命薦隆, 位登金闕, 逍遙紫虛, 遊神察訪, 而世變愈降. 偷薄鄙詐之風, 在在皆然. 況劫難將興, 未易消弭. 乃寓鸞顯化.

Human heart-minds become depraved every day, and enlightenment is seriously urgent. Although we could not secure three persons for the phoenix each time, we should transmit spirit-writing everywhere. Then, how can we wait for the wood-pen on the sandtray and the splendorous phoenix of the beautiful pavilion? Sometimes we show dream revelations, and sometimes we give lessons by miracles.(KGJ, vol. 1, 28b)

人心日異, 開化時急. 每不擇三鸞之人, 而徧處降乩. 奚待沙盤之木筆, 畵亭之綵鸞乎? 或示夢諭, 或誡靈跡.

5.2. Sacred Writs, Cure, and Distribution of Scriptures

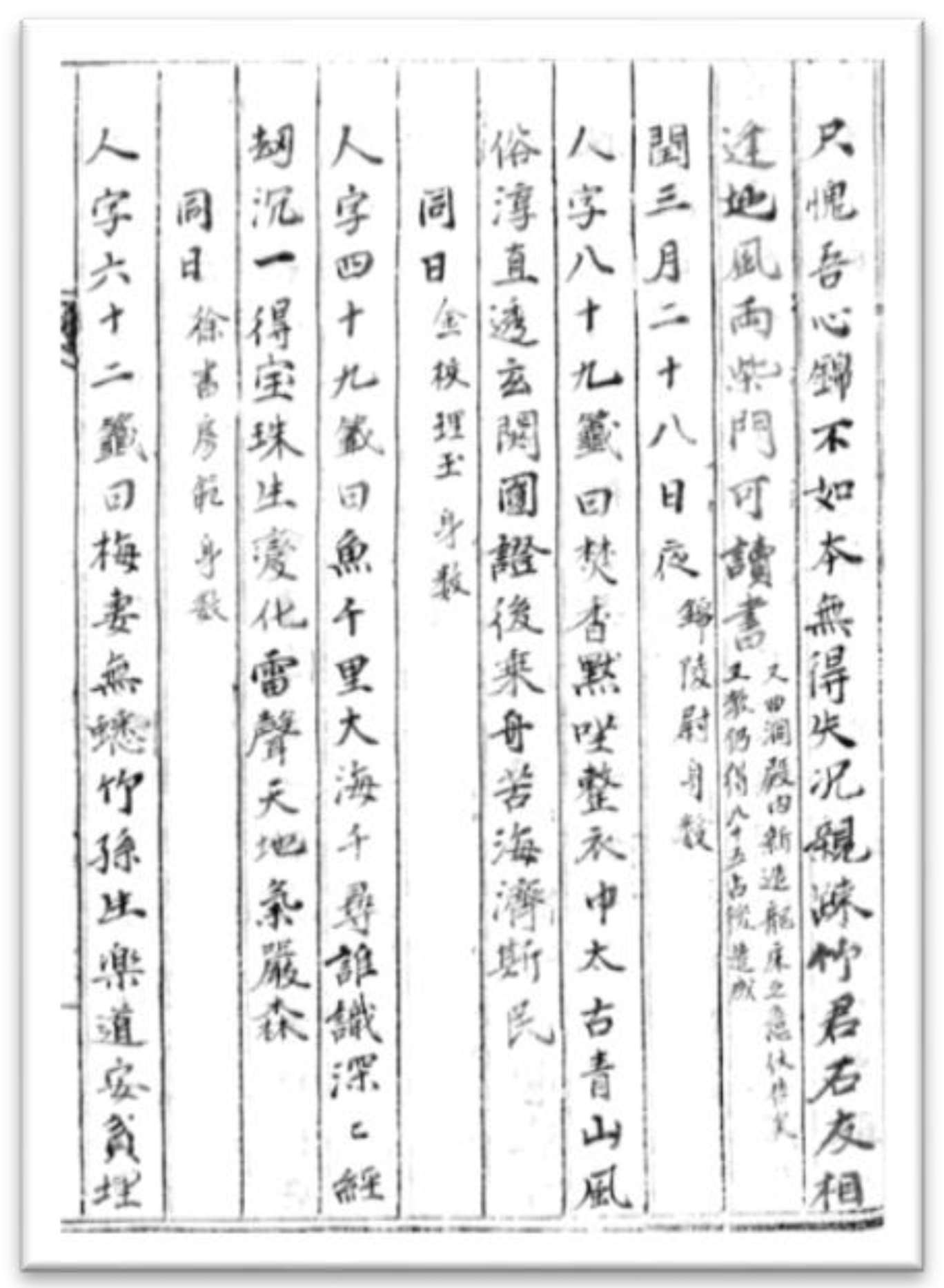

We received the order at the time of republishing the Illustrated Records of Sacred Achievement in 1876 that the Three Sages descended the eight-line regulated verse by spirit-writing to make pillar couplet for the East Shrine.(SGJ 1878-2-10, 23b-24b)

丙子年《聖蹟圖誌》重刊時, 三聖帝乩下律詩八句, 以爲東廟楹聯事, 奉命矣.

[1878-5-28] Disciple Yu Un and Yi Chinsun report: As for the work of [completing] the Corpus of Three Sages Enlightenment, we already humbly received the holy decree from the Thearch of Literature to sincerely publish the sacred teachings of Records of Cassia Palace and Collection of Various Fragrances. In consideration of completing them as soon as possible, we humbly [report] our plan. A faithful official Kim Ch’anghŭi had wished to read the sacred texts carefully, and suggested, “[Because] the collections of Three Sages’ [texts] have a great relation to Enlightenment, we must cut out superfluity. If we only select the sacred scriptures, lessons, hagiographies, miraculous stories of the Three Sages, and make efforts to simplify them down to the essentilas, appositely anticipating that [Scripture of] Awakening the World will provoke the faith, then their circulation will have no obstacle.”(SGJ, 27a-27b)

臣弟子劉雲・李瑨淳白: 三聖開化藏之役, 旣伏承文帝聖旨, 祗刊《桂宮誌》・《衆香集》之聖敎, 以爲從速撰成, 伏計矣. 信官金昌熙發願參閱於聖典, 而獻議言: “三聖合集, 大有關於開化, 須删去煩冗. 惟輯三聖聖經・聖訓・本紀・聖籤・靈驗, 務在簡要切實, 而期《覺世》起信, 流通無礙”云.

[Thearch Kwan] received the command from the Heaven, along with the other two Thearchs of Literature and Succour, to get their official duty to enlighten [the world] and promulgate [transformation] through spirit-writing phoenix.

[關聖帝君] 受天敕, 與文昌・孚佑兩帝君, 職任開化, 鸞乩宣誥.

[The Thearch of Literature] together with Thearch Kwan and Patriarch Lü, received the heavenly command to enlighten [the world] below Heaven.

[文昌帝君] 與關帝・呂祖, 同受天敕, 開化天下.

[The Thearch of Succour] served the command from the Heaven, received his duty to promulgate transformation with the other two lords of Thearch of Literature and Thearch Kwan. Thus, he traveled to the eight ends [of the world] to establish the salvation and complete all wishes of ordinary people.

[孚佑帝君] 乃奉天勅, 受宣化之職, 與文昌・關聖二帝君, 周遊八極立度, 盡凡夫之弘願.(SSHG 1880, 1a-1b)

[1880-3-11] I entered the Palace and attended on [his Royal Majesty], to deliver the Thearch’s will, and informed of the exorcism on the last night, as well. I received the edict to print and distribute several scriptures. [The Royal Majesty] asked whether or not there are the woodblocks of Anthology for the Pious Faith (JXL) and Folios on Retribution (GYP); thus, I replied and came out.(SGJ, 65b)

入侍大內, 仰稟聖意, 亦聞夜間掃氛之事. 承諸經印布之敎. 而下詢《敬信錄》・《感應篇》板本有無, 故仰對而出.

[1880-03-12] I entered the Palace and attended on [his Royal Majesty], to dedicate JXL and KHJS. Then, there was a royal edict to print and distribute them. There was another edict to find and present GYP.42(SGJ, 66a)

入侍大內, 進獻《敬信錄》・《過化存神》, 則有印布之敎. 又《感應篇》求進之敎.

[1880-07-06] The Highest Thearch, Jade Emperor issued an edict: “The King of your country, from now onwards, his mind to enlighten-transform people will become greater.” Thus, the Highest Thearch acclaimed his great virtue and commanded us as follows: To the King of your country, endow the reward by prolonging his life one cycle (twelve years); to the Queen and the Crown Prince, also extend one cycle (twelve years) of life. …Later, you can tell this edict of the Highest Thearch to your King.(SGJ, 71b)

玉皇上帝勅敎內: 汝之國王, 自今以來, 化民之心甚大. 故上帝讚其大德, 命於吾等: 汝之國王, 賜賞增壽一紀, 國母元儲, 亦各增一紀之壽. …… 後上帝勅旨, 傳宣汝之國王, 可也.

[1880-7-24] (Instruction and divination received in the dream of Kim Hŭijŏng).

Deep inside the peak, turning along the lane,

I passed the root of the mountain.

A house was there, among the woods in the bloom of golden flowers.

I asked: Where is the noble master?

Then in the remote valley, downside the brook,

the brushwood door was opened up.(SGJ, 72b)

庚辰七月二十四日(金熙鼎夢中下賜戒訓占)

峯深路轉過山根, 家在黃華爛漫樹, 借問高人何處在, 僻溪澗下闢柴門.

6. The Project of Enlightenment and Reform

I reformed the state government, in order to initiate the foundation of independence and build up the work of national restoration.…We will carry out the plan for beneficial utility and prosperous livelihoods, with impartial and righteous gorvernance.…so that my children [i.e., the people].…may live in peace and delight in their occupations.… Let all know that Reform and Enlightenment truly originates from [the heart of caring] for the people.(CWS 1895-5-20)

維新國政, 肇獨立之基, 建中興之業.…以公平正大之政, 行利用厚生之方.… 俾朕赤子.…安生而樂業.… 咸知更張開化之亶出於爲民也.

Imperial Edict: Every country in the world reveres a Fundamental Teaching [religion] without exception of using it as the center, because it refines human mind and results in the [righteous] way of rule…As for the religion of my country, is it not the Way of our Confucius?(CWS 1899-4-27)

詔曰: 世界萬國之尊尙宗敎, 靡不用極, 皆所以淑人心而出治道也.…我國之宗敎, 非吾孔夫子之道乎?46

That which is called Enlightenment is nothing but the expansion of the public [impartial] way [of discussion] and abolishment of personal [partial] opinion, so as to cause both officials and the people do their work rightly, thereby opening the source of beneficial utility and prosperous livelihoods, and do everything for enriching the country and strengthen the armed forces.… If they (Japan) had come with good intentions, … they should let our Lord and officials concentrate our minds and cultivate our roots, to make both domestic and foreign affairs organized and clear; according to public opinion and aiming at the right timing, [we can] gradually gain the momentum of self-government and steadily achieve the concrete reality of Enlightenment.(CWS 1894-10-3)

夫所謂開化者, 不過曰恢張公道, 務祛私見, 使官不尸位, 使民不遊食, 開利用厚生之源, 盡富國强兵之術而已….彼果出於好意也.…俾我君臣, 得以聚精會神, 培根端本, 內理外靖, 因民心酌時宜, 漸鞏自主之勢, 徐就開化之實.

As for so-called Enlightenment, this official knows nothing about what it is nowadays. Nevertheless, in my foolish opinion, from the period of Ancient Kija [Chosŏn] to Our Dynasty, the National Code has been brilliantly constituted, being the means by which people have been blessed and nurtured. The Way of Enlightenment has been already qualified without remainder, such as Comprehensive Compilation of National Code [Taejŏn t’ongp’yŏn大典通編, 1784] and Six Codes of Ordinances [Yukchŏn jorye六典條例, 1866]. However, the Way of Governance is not in inoperative laws, but in its concrete implimentation, so as to moderate control and to protect and cherish people. Only after that will our country get closer [to the ideal of Enlightenment].(CWS 1902-10-5)

今所云開化, 臣未知何件事. 而臣之愚見, 自箕子以來至于我朝, 典章燦備, 生民休養, 開化之道, 已盡無餘. 《大典通編》・《六典條例》, 此其具也. 然而爲治之道, 不在徒法, 在乎實行, 制節用度, 保愛生民, 然後國其庶幾也.

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

Primary Sources

Chibokchae sŏjŏk mokrok 集玉齋書籍目錄 [Book Catalog of the Studio of Collecting Jade]. 1908. http://kyujanggak.snu.ac.kr/.(CHJ 1881) Chunghyang jip 衆香集 [Collection of Various Fragrance] 1881. Chosŏn. Print.(CWS) Chosŏn Wangjo Sillok朝鮮王朝實錄 [Veritable Records of the Chosŏn Dynasty]. http://sillok.history.go.kr.(DZ22) Yuanshi wulao chishu yupian zhenwen tianshu jing元始五老赤書玉篇眞文天書經 [Scripture of the True Writs of the Five Ancients of the Primordial Beginning, written in Reddish Celestial Script on Jade Tablet]. In Daozang 道藏 [Daoist Canon]. Shanghai: Hanfenlou Edition涵芬楼版.(DZ29) Yuanshi tianzun shup Zitong dijun benyuan jing 元始天尊說梓潼帝君本願經 [Scripture of the Original Vow of the Dicine Lord of Zitong, as Expounded by the Heavenly Worthy of Primordial Beginning].(DZ1124) Dongxuan lingbao xuanmen dayi 洞玄靈寶玄門大義 [The Great Meanings of the Gate of Mystery (Daoism), Numinous Treasure in Cavern of Mystery].(DZ1241) Chuanshou sandong jingjie falu lüeshuo 傳授三洞經戒法籙略說 [Outline of the Transmission of Three Cavern Scriptures, Precepts, Manuals, and Registers].(Giacinti 1897) Giacinti, J. T. The Late Hon. Soh Kwangpom, The Independent 105(2), September 4, 1897. (Reprinted in The Korean Repository Vol. Ⅳ, January-December 1897, Seoul: The Trilingual Press).(GDQS 1858) Guandi quanshu關帝全書 [The Complete Collection of Thearch Guan]. 1858. Edited by Huang Qishu 黃啓曙. [Guandi wenxian huibian關帝文獻匯編. 1995. Beijing 北京: Guoji wenhua chuban gongsi].(Fukuzawa 1867) Fukuzawa Yukichi 福澤諭吉. 1867. Seiyōjijō Gaihen西洋事情外篇 [Western Matters: Extra Edition]. Tokyo: Woodblock-print.(HC 1986) Han’guk ŏhak charyo ch’ongsŏ 韓國語學資料叢書 [Collection of Sources for Korean Language Studies]. 1986. Seoul: T’aehaksa. 8 vols.(HD 1876) Haedong sŏngjŏk-chi 海東聖蹟誌 [The Records of Sacred Achievements in the East of Sea]. 1876. Woodblock-print. Chosŏn.(JY255) Wendi huashu 文帝化書 [The Book of Transformation of Thearch of Literature]. In Chongkan Daozang jiyao 重刊道藏輯要 [Essentials of Daoist Canon]. Sichuan: Erxianan Edition 二仙庵版.(JY261) Guansheng dijun benzhuan 關聖帝君本傳 [The Higiography of Thearch Lord Sage Guan]. In Chongkan Daozang jiyao.(KGJ 1881) Kyegung-ji 桂宮誌 [Record of the Cassia Palace]. 1881. Chosŏn.(KHJS 1880) Kwahwa jonsin過化存神 [Enlightened by Passing, Miracles by Presence]. 1880. Chosŏn.(KJ 1876) Kwansŏng-jegun sŏngjŏk doji jŏnjip關聖帝君聖蹟圖誌全集 [The Complete Collection of Illustrated Records of Sacred Achievements of the Thearch Lord Sage Kwan]. 1876. Woodblock-print. Tanguk Hyŏnsŏng jŏn 檀國顯聖殿 [the Pavilion of Manifesting the Sacred, the Country of Tan (Gun)]. Chosŏn. Reprint.(KS 1876) Kwansŏng-jhegun sŏngjŏk doji sokchip關聖帝君聖蹟圖誌續集 [Continuation of the Illustrated Records of Sacred Achievements of the Thearch Lord Sage Kwan]. 1876. Chosŏn.(Kim O. 1885) Kim Okkyun金玉均. 1885. Kapsinillok ryakcho 甲申日錄略抄 [Abbreviated Draft of the Daily Record of (Regime Change) in 1884]. Stored at Tōyō bunko東洋文庫.(Kim T. 1922) Kim Taekyŏng金澤榮. 1922. An Hyoje jŏn 安孝濟傳 [Biography of An Hyo-je], Sohodangjip 韶濩堂集 [Collected Works of Sohodang]. In Han’guk munjip ch’onggan韓國文集叢刊 [Compendium for the Comprehensive Publication of Korean Literary Collections] vol. 347. Seoul: Minjok Munhwa Chʻujinhoe. 1990.(KGS 1929) Kogosaeng 考古生. 1929. Kyŏngsŏng i kajin myŏngso wa kojŏk 京城이 가진 名所와 古蹟 [The Famous Places and Relics of Seoul]. Pyŏlgŏngon별건곤 [Another Universe]. Vol. 23. http://db.history.go.kr/item/level.do?levelId=ma_015_0210_0070.(LZQS) Lüzu quanshu 呂祖全書 [Complete Works of Patriarch Lü]. 1868. Qing Edition.(MC1) Munch’ang-jegun mongsu pijang kyŏng 文昌帝君夢授秘藏經 [Secret Scripture of Thearch of Literature Bestowed in Dream]. 1878. Chosŏn. Wooden movable type print.(MC2) Munch’ang-jegun sŏngse kyŏng文昌帝君惺世經 [Scripture of Thearch of Literature to Awakem the World]. 1878. Chosŏn. Wooden movable type print.(MC3) Munch’ang-jegun t’ongsam kyŏng文昌帝君統三經 [Scripture of Thearch of Literature to Unify the Three Teachings]. 1878. Chosŏn, Wooden movable type print.(NGB) Nihon gaikō bunsho日本外交文書 [Japanese Diplomatic Documents]. https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/annai/honsho/shiryo/archives/mokuji.html.(SGJ) Sŏnggye-jip聖乩集 [The Collection of Sacred Spirit-writings]. Handwritten Manuscript. Chosŏn. Handwritten Manuscript. Stored in Kyujang-gak Institute for Korean Studies, Seoul National University. http://kyujanggak.snu.ac.kr/home/index.do?idx=06&siteCd=KYU&topMenuId=206&targetId=379.(SHJJ 1878) Simhak jŏngjŏn心學正傳 [Orthodox Transmission in Learning of Heart-mind]. 1878. Chosŏn.(SJW) Sŭngjŏng-wŏn Illgi 承政院日記 [The Daily Records of Royal Secretariat of Chosŏn Dynasty] http://sjw.history.go.kr(SSHG 1880) Samsŏng hun’gyŏng三聖訓經 [Admonition of the Three Sages] 1880. Chosŏn.(Shinbun) Shinbun shūsei: Meiji hennen shi (新聞集成) 明治編年史 [The Meiji Chronicles: Collection of Newspapers]. 15 vols. Edited by Nakayama Yasumasa 中山泰昌. 1936–1940. Tokyo: Rinsensha林泉社. Vol. 4 https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1920347; Vol. 5 https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1920354.(SXTZ 1734) Shanxi tongzhi 山西通志 [Comprehensive Gazetteer of Shanxi]. 1734. Edited by Luo Shilin 羅石麟. Siku quanshu四庫全書 edition.(Yu 1895) Yu Kilchun 兪吉濬. 1895. Kaehwa tŭngkŭp開化等級 [Levels of Enlightenment]. Sŏyu kyŏnmun西遊見聞 [Observations on a Journey to the West]. Tokyo: Kōjunsha.(Yun) Yun Chiho 尹致昊. Yun Chiho Ilgi 尹致昊日記 [Yun Chi-ho’s Diary]. In Han’guk saryo ch’ongsŏ 韓國史料叢書 [Collection of Sources for Korean History] 19. 6 vols. Edited by Kuksa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏn hŏi 國史編纂委員會. 1973–1976. http://db.history.go.kr/item/level.do?levelId=sa_024r.Newspaper Archive of Korea. https://www.nl.go.kr/newspaper/Tongnip Sinmun 7 April 1896. “Ghost Worship and Idolatry.” http://lod.nl.go.kr/resource/CNTS-00098985730.Tongnip Sinmun 20 February 1899. “Volunteering in Restoration.” http://lod.nl.go.kr/resource/CNTS-00098999144.Tongnip Sinmun 21 February 1899. “A Funny Story.” https://lod.nl.go.kr/page/CNTS-00098999174.Maeil Sinbo 3 May 1914. “The Overcrowded South Kwanwang Shrine at the Spring Festival.” http://lod.nl.go.kr/resource/CNTS-00093971010.Shidae Ilbo 24 April 1924. “The Demolition of Kwanwang Shrine: People are against it.” http://lod.nl.go.kr/resource/CNTS-00093343940.Shidae Ilbo 24 November 1924. “Misfortune of Kanwang Shrines”; “Must Expelled Kwanwang Shrine (The Hall of Superstition).” http://lod.nl.go.kr/resource/CNTS-00093360907.Koryŏ sibo 1 March 1939. “New Year Fortune Telling: Over Five Thousand People for Divination.” http://lod.nl.go.kr/resource/CNTS-00109317993.Secondary Sources

- Brokaw, Cynthia. 1991. The Ledgers of Merit and Demerit: Social Change and Moral Order in Late Imperial China. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burton-Rose, Daniel. 2015. A Prolific Spirit: Peng Dingqiu’s Posthumous Career on the Spirit Altar, 1720–1906. Daoism: Religion, History and Society 7: 7–63. [Google Scholar]

- Burton-Rose, Daniel. 2020. Establishing a Literati Spirit-Writing Altar in early Qing Suzhou: The Optimus Prophecy of Peng Dingqiu (1645–1719). T’oung Pao 106. [Google Scholar]

- Duara, Prasenjit. 1988. Superscribing Symbols: The Myth of Guandi, Chinese God of War. Journal of Asian Studies 47: 778–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, Monica. 2013. Creative Taoism. Wil and Paris: University Media. [Google Scholar]

- Goosseaert, Vincent. 2014. Modern Daoist Eschatology: Spirit-writing and Elite Soteriology in Late Imperial China. Daoism, Religion, History & Society 6: 219–46. [Google Scholar]

- Goosseaert, Vincent. 2015. Spirit Writing, Canonization, and the Rise of Divine Saviors: Wenchang, Lüzu, and Guandi, 1700–1858. Late Imperial China 36: 82–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooossaert, Vincent. 2017. The Textual Canonization of Guandi. In Rooted in Hope. Vol. 2: Other Religions in China. Edited by Barbara Hoster, Dirk Kuhlmann and Zbigniew Wesolovski. Monumenta Serica Monograph Series LXVⅢ/2; Sankt Augustin: Routledge, pp. 509–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Jangsik 장장식. 2004. Sŏur ŭi kwanwangmyo kŏnch’i wa kwanusinang ŭi yangsang 서울의 관왕묘 건치와 관우신앙의 양상 [The Establishment of the Kwanwang Shrines and the Development of Kwanwoo Worship in Seoul]. Minsok’akyŏn’gu민속학연구 [Korean Journal of Folk Studies] 14: 403–40. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Paul. 1996. Enlightended Alchemist or Immoral Immortal? The Growth of Lü Dongbin’s Cult in Late Imperial China. In Unruly Gods: Divinity and Society in China. Edited by Meir Shahar and Robert Weller. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 70–104. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Paul. 2015. Spirit-writing and the Dynamics of Elite Religious Life in Republican-era Shanghai. In Jindai zhongguo de zongjiao fazhan lunwenji 近代中國的宗教發展論文集. Taipei: Guoshiguan, pp. 275–350. [Google Scholar]

- Kiely, Jan. 2017. The Charismatic Monk and The Chanting Masses: Master Yinguang and His Pure Land Revival Movement. In Making Saints in Modern China. Edited by David Ownby, Vincent Goossaert and Ji Zhe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Ilgwon 김일권. 2014. Chosŏn hugi kwansŏng-kyo ŭi kyŏngsin suhaeng-non 조선 후기 關聖敎의 敬信修行論 [A Study on the Faith-Reverence Practice of Kwan-sung Taoism in the Late Choseon Dynasty]. Dokyo munhwa yŏn’gu 道敎文化硏究 [Journal of the Studies of Taoism and Culture] 40: 157–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jihyun. 2019. Daoist Writs and Scriptures as Sacred Beings. Postscripts 10: 122–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Jong Hak 김종학. 2017. Kaehwa-dang ŭi kiwŏn kwa pimil wŏigyo개화당의 기원과 비밀외교 [The Origin of Enlightenment Party and Secret Diplomacy]. Seoul: Ilchokak일조각. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Myoungho 김명호. 2011. Sirhak gwa kaehwa sasang 실학과 개화사상 [Practical Learning and Enlightenment Ideas]. Han’guksa simin kangjwa 한국사 시민강좌 [Citizen Forum for Korean History] 48: 134–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Youngmin 김영민. 2013. Chosŏn Chunghwajuŭi ŭi chaekŏmt’o: Ironjŏk chŏpkŭn” 조선중화주의의 재검토: 이론적 접근 [Reconsidering Sinocentrism in Late Choson Korea: A Theoretical Approach]. Han’guksa yŏn’gu 韓國史硏究 [The Journal of of Korean History] 162: 211–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Youngmin. 2019. An Interpretive Approach to “Chinese” Identity. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Political Theory. Edited by Leigh K. Jenco, Murad Idris and Megan C. Thomas. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Youn Gyeong 김윤경. 2012. Chosŏn hugi min’gandogyo ŭi parhyŏn gwa chŏn’gae: Chosŏn hugi kwanje shinang, sŏnŭmjŭlgyo, musangdan조선 후기 민간도교의 발현과 전개—조선후기 관제신앙, 선음즐교, 무상단 [Expression and Deployment of Folk Taoism in the Late of Chosŏn Dynasty]. Han’guk ch’ŏllak nonjip한국철학논집 [Journal of Korean Philosophical History] 35: 309–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Youn Gyeong. 2019. 19 segi ch’oech’o ŭi togyo kyodan, musangdan yŏn’gu 19세기 최초의 도교 교단, 무상단 연구 [A Study of Spirit-writing Community in Joseon Dynasty]. Han’guk ch’ŏllak nonjip 한국철학논집 [Journal of Korean Philosophical History] 63: 127–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Yun Soo 김윤수. 2008. Kojong-gi ŭi landan dogyo 高宗期의 鸞壇道敎 [Spirit-writing Altar Daoism in Kojong Period]. Tongyang ch’ŏllak동양철학 [Asian Philosophy] 30: 57–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kleeman, Terry F. 1993. The Expansion of the Wen-ch’ang Cult. In Religion and Society in T’ang and Sung China. Edited by Patricia Buckley Ebrey and Peter N. Gregory. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 45–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kleeman, Terry F. 1994. A God’s Own Tale. The Book of Transformations of Wenchang, the Divine Lord of Zitong. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koselleck, Reinhart. 1988. Critique and Crisis: Enlightenment and the Pathogenesis of Modern Society. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Chi-Tim. 2016. Shijian, xiulian yu jiangji: cong nansong dao qing zhongye lüdongbin xianhua duren de shiji fenxi lüzu xinyang de bianhua 識見、修煉與降乩──從南宋到清中葉呂洞賓顯化度人的事蹟分析呂祖信仰的變化 [Recognition, Self-cultivation and Spirit-writing: On the Changing Conceptions of the Immortal Lü Dongbin from the Southern Song to the Mid-Qing]. Qinghua xuebao 清華學報 [Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies] 46: 41–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Ki Baik. 1984. A New History of Korea. Translated by Edward W. Wagner, and Edward J. Shultz. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Kwang Rin 李光麟. 1989. Kaehwap’a wa kaehwa sasang yŏn’gu 開化派와 開化思想硏究 [Study of Enlightenment Thinking and Its School]. Seoul: Ilchogak. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, You-Na. 2006. Chosŏnhugi Kwan U sinang yon’gu 조선후기 關羽신앙 연구 [A Study on the Belief of Kwan-Woo in the Late Chosun Dynasty]. Tonghak yŏn’gu동학연구 [Study of Eastern Learning] 20: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, Yuria 森由利亞. 2001. Dōzo shūyō to Shō Yoho no Ryoso fukei shinkō 道藏輯要と蔣予蒲の呂祖扶乩信仰. Tōhō Shūkyō東方宗敎 98: 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Murayama, Chijun 村山智順. 1935. Chosen no ruiji shūkyō 朝鮮の類似宗敎. Keijo (Seoul): Chosen sotoku fu 朝鮮總督府. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Korean History (Kuksa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏn hŏi국사편찬위원회). 1998. Chosŏnhugi ŭi munhwa조선후기의 문화 [The Late Chosŏn Culture]. Sinp’yŏn Hanguk-sa (신편) 한국사 [Korean History: New Edition]. Gwacheon: Kuksa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏn hŏi, vol. 35. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Korean History (Kuksa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏn hŏi국사편찬위원회). 1999. Kaehwa wa sugu ŭi kaldŭng 개화와 수구의 갈등 [Conflict between Enlightenment and Conservatism]. In Sinp’yŏn Hanguk-sa (신편) 한국사 [Korean History: New Edition]. Gwacheon: Kuksa p’yŏnch’an wiwŏn hŏi, vol. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, Kwan Bum 노관범. 2019. Kaehwa wa Sugu nŭn ŏnje illonat’nŭnga? ‘개화와 수구’는 언제 일어났는가? [A Study on the Historical Appearance of ‘Gaehwa and Sugu’ around the End of the Joseon Dynasty]. Han’guk Munhwa한국문화 [Korean Culure] 87: 345–94. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Byounghoon 박병훈. 2020. Tonghak kangp’il yŏn’gu 동학 강필 연구 [Study on Spirit Writing in Eastern Learning]. Chonggyo yŏn’gu 宗敎硏究 [Korean Journal of Religious Studies] 80: 235–52. [Google Scholar]

- Eunsook Park 박은숙, trans. 2009, Kapsin Chŏngbyŏn kwallyŏnja simmun, chinsul kirok: Chʻuan kŭp Kugan jung 갑신정변 관련자 심문·진술 기록 추안급국안(推案及鞫案) 중 [Records of Interrogations and Statements of People involved in Kapsin Coup: From the Ch’uan and Kugan]. Seoul: Asea Munhwasa.

- Park, Soyun. 2017. 19 segi huban Sŏul-chiyŏk sinang-gyŏlsa hwaltong gwa kŭ ŭimi: Pulgyo・Togyo kyŏlsa rŭl chungsimŭro 19세기 후반 서울지역 신앙결사 활동과 그 의미: 불교·도교 결사를 중심으로 [A Study on the Activities and the Meanings of Religious Associations at Seoul in the Late 19th Century: With Reference to Buddhist and Daoist Associations]. Han’guk kŭnhyŏndaesa yŏn’gu 한국근현대사연구 [Journal of Korean Modern and Contemporary History] 80: 7–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, Tadao 酒井忠夫. 1999–2000. Zōho Chūgoku zensho no kenkyū 増補中國善書の研究 [Studies of Chinese Morality Books, Expanded]. 2 vols. Tokyo: Kokusho kankōkai. [Google Scholar]

- Saler, Michael. 2006. Modernity and Enchantment: A Historiographic Review. The American Historical Review 111: 692–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Sujung. 2017. 19 segi huban kyŏlsa-danch’e ŭi pulsŏ p’yŏngan paekyŏng 19세기 후반 결사단체의 佛書 編刊 배경 [A Background on the Compilation and Publication of Buddhist Text by Buddhist Societies in the late 19th century]. Han’guk pulgyosa yŏn’gu 韓國佛敎史硏究 [Journal for the Study of Korean Buddhist History] 11: 298–330. [Google Scholar]

- Seth, Michael J. 2010. A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, Yongha 愼鏞廈. 2000. Ch’ogi Kaehwa sasang kwa Kapsin chŏngbyŏn Yŏn’gu初期 開化思想과 甲申政變硏究 [Study on Early Enlightenment Idea and Kapsin Regime Change]. Seoul: Chisik sanŏp sa. [Google Scholar]

- Stuke, Horst. 2014. Auf Klärung. Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Edited by Reinhart Koselleck Stuttgart. Translated by Nam Ki-ho. Seoul: P’urŭn Yŏksa. First published 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ter Haar, Barend J. 2017. Guan Yu: The Religious Afterlife of a Failed Hero. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lieu, Joshua. 2014. A Farce that Wounds Both High and Low: The Guan Yu Cult in Chosŏn-Ming Relations. Journal of Korean Religions 5: 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Chien-ch’uan 王見川. 2015. Spirit Writing Groups in Modern China (1840–1937): Textual Production, Public Teaching, and Charity. In Modern Chinese ReligionⅡ: 1850–2015. Edited by Vincent Goossaert, Jan Kiely and John Lagerway. Leiden: Brill, pp. 651–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, Chi-on 游子安. 2005. Shan yu ren tong: Ming Qing yilai de cishan yu jiaohua善與人同: 明清以來的慈善與敎化 [Goodness is One with Human Nature: Charity and Moral Reform during the Ming and Qing periods]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, Chi-on 游子安. 2010. Fuhua yunei: Qingdai yilai guandi shanshu ji qi xinyang de quanbo 敷化宇內: 清代以來關帝善書及其信仰的傳播 [Transforming all under Heaven: The Guandi Morality Books and Beliefs and their Transmission from the Qing period to the present]. Zhongguo wenhua yanjiusuo xuebao中國文化研究所學報 [Journal of Chinese Studies] 50: 219–53. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Nŭnghwa 이능화. 1986. Chosŏn dokyo sa 朝鮮道敎史 [History of Korean Daoism]. Annotated by Yi Chong-Eŭn李鍾殷. Seoul: Bosŏng munhwa sa. First published in 1929. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | As stated below, “enlightenment” was translated as kaika in late Edo Japan. On the other hand, Korean “kaehwa” was also rendered as “Enlightenment” in most modern English articles and books of Korean history. For example, see (K. B. Lee 1984, p. 297; Seth 2010, pp. 226–39). |

| 2 | I used the term “Kapsin Regime Change’’ for Kapsin Chŏngbyŏn 甲申政變 instead of the “Kapshin Coup’’ or “Coup d’etat’’ (K.B. Lee 1984; Seth 2010, pp. 237–39) because Kim Okkyun and his allies had no intention of eliminating their King. They launched a coup against the conservative pro-China faction, not against king Kojong. Although they maintained the equality of people, they planed to reform government as a constitutional monarchy under the rule of Kojong. After the failure, their opponents defined it as treason and called for punishment. Although Kojong bowed to pressure and gave a tacit admission of assassinating Kim Okkyun, Kojong took most of the members again as the leading party of the 1894 Reform. On the Kapsin Regime Change, see (Yi [1929] 1986; Shin 2000). |

| 3 | Shinbun, vol. 4, pp. 386–87. Chōya shinbō 朝野新報: Chōsen kaikatō no tameni ansatsu sareta Ri Tōjin 朝鮮開化黨の爲に暗殺された李東仁. |

| 4 | Op. cit., vol. 4, p. 393. Tōkyō nichinichi shinbun 東京日日新聞 7 May 1881. Chosŏn court officials came to study Japan: Enemies of the progressive and the conservative in the same boat (朝鮮國朝士日本の硏究に渡來:開進守舊の吳越同舟). While it stated “Ichitō wa shukyū, ichitō wa kaishin 一黨は守舊, 一黨は開進,” Yi Man-son 李萬孫 and Sim Sang-hak 沈相學 were the representatives of the conservatives; Ŏ Yun-jung 魚允中 represented the Enlightenment Party (kaikatō 開化黨). |

| 5 | Ibid., vol. 5, p. 48. Chōsen shinbō 朝鮮新報, Kin Gyokukin ōmei o ukete Nihon e 金玉均王命を受けて日本へ: “朝鮮の開化黨の有名なる金玉均は今般王命を奉じ我國に渡航する.”. |

| 6 | Fukuzawa 1867, pp. 10–11. 歴史ヲ察スルニ人生ノ始ハ芥昧ニシテ次第ニ文明開化ニ赴クモノナリ. |

| 7 | NGB 9-1, No. 6, 38. 開化ノ人ニ遇ヒ開化ノ談ヲ爲ス情意殊ニ舒ブ. |

| 8 | There was a court lady, nicknamed the Lady Counselor (ko-daesu), who served to the Queen and communicated with Kim Okkyun’s party in secret. Kim O. 1884-12-01. 一宮女某氏(年今四十二, 身體健大, 如男子, 有膂力, 可當男子五六人. 素以顧大嫂稱別號, 所以得坤殿寵時得近侍, 自十年以前, 趨附吾黨, 時以密事通報者也). |

| 9 | I will use this date format (year-month-day) for the records of the lunisolar calendar type. In Korea, the Gregorian calendar was adopted in 1896. |

| 10 | According to the record of KS, Jueshi zhenjing was revealed in 1668 (the seventh year of Kangxi 康熙七年). KS 1876, vol. 1, 1a-b. Sakai pointed out its Japanese edition was circulated in the 1680s in Edo Japan without affirming the exact dating of the text (Sakai 1999–2000, vol. 2, pp. 184–85; vol. 2, p. 374). See also Goossaert 2017, pp. 512–13; Yau 2015, pp. 222–25. |

| 11 | I will unify their titles in Korean texts as Thearch Kwan, Thearch of Succour, and Thearch of Literature. |

| 12 | Guan Yu was given the rank of Thearch in 1590 for the first time, titled “xietian huguo zhongyi dadi 協天護國忠義大帝, “the Great Thearch of Loyalty and Justice Who Protects the State and Assists the Heaven” (SXTZ, vol. 167). He subsequently received the title, “the Thearch Lord Sage Guan, Heavenly Worthy of Overarching Suppression with Divine Power, the Great Thearch who Subdues Demons in the Three Realms (Sanjie fumo dadi shenwei yuanzhen tianxun guansheng dijun 三界伏魔大帝神威遠鎭天尊關聖帝君” in 1605 (KJ 1876, vol. 3, 12a). |

| 13 | Nevertheless, modern studies are inclined to discuss the Guandi cult as a popular faith (mingan sinang 民間信仰) (NIKH 1998, pp. 160–63). Youn Gyeong Kim categorized Kwanwang cult as “popular Daoism,” in the sense that the cult pervaded the broad social classes, albeit its origin was the state cult (Y.G. Kim 2012, pp. 312–13). Most researches agree that the characteristic of the Kwanwang cult was royal-initiated and became popularized in the entire state in the Kojong period (Murayama 1935; Jang 2004; Y. Lee 2006). |

| 14 | About twelve names of Yi clan members appear in SGJ. Among them were: Yi Chunmo (i.e., Chinmo), the guard commander of Kyŏnghŭi Palace 慶熙宮衛將; Yi Hangyu 李漢奎 (48a); Yi Bonghwan 李鳳煥 (62a-63a), who held the post of the commander of Five Guards 五衛將; and Yi Wŏnsik 李源植 (68a), a commander of Palace Gate 守門將. The guard commander (wijang) had no fixed assingnment. |

| 15 | SGJ 1880-10-24, 31a. 李生瑨淳也, 田生在植也, 我本最愛之人也. |

| 16 | SGJ 1879-3-22, 44b-45a. 上行十籤事, 三日晝夜硏究後, 聖廟創建事, 伏祝矣. 得六十一籤. |

| 17 | SGJ 1879-3-23, 45a. 聖廟事引道之人, 以何處可合之意, 伏告. 得五十四籤. |

| 18 | SGJ 1879-3-24, 45b-47b. 夢謁領相・都統之後, 覺而卽入殿內, 以周施之意, 而處身數, 伏告. 得十八籤, 得二十籤. SGJ 1879-6-5, 47b. 領相直心職事, 伏祝. |

| 19 | Cho Yongha was Minister of Work (kongjo p’ansŏ 工曹判書) in 1876 and served as Minister of Rites (yejo p’ansŏ 禮曹判書) and Minister of Pessonel (ijo p’ansŏ 吏曹判書) in 1877. |

| 20 | Pak was nineteen years of age and married to the princess Yŏnghye 永惠 (1859–1872). Kim Okkyun was twenty-nine and served as the fifth-rank official at the Office of Special Adviser (Hongmun-gwan 弘文館). Sŏ Kwangbŏm was twenty-one; he had not yet passed the civil service examination. “Sŏbang” is literally “a book-room,” which is a common title for educated men preparing for the exams. |

| 21 | SGJ 1879-3-28. 魚千里大海千尋, 誰識深深經劫沈, 一得寶珠生變化, 雷聲天地氣嚴森. The oracle poem was No. 49 lot of the Sacred Lots in KS 1876, vol. 3, 68. |

| 22 | SGJ 1876-10-7. 學宗春秋, 直接孔門之道統. Guan Yu’s Confucian lineage has been built up in China, and became prominent in Qing texts. KJ 1876 (GQ 1693); JY261, 1a. 關聖帝君本傳: 帝字雲長, … 爲人義勇絶倫, 好讀左氏春秋, 諷誦略皆上口. It was already well known in eighteenth century Chosŏn (CWS 1730-12-6). |

| 23 | Military Traning Corps had a set of movable type (訓練都監字) since the sixteenth century, by which many books were printed. |

| 24 | SGJ 1877-9-21, 9a. Yi Chinsun (i.e., Chinmo) made divination with the One-Hundred Lots inside a shrine in his house. He reported to Thearch Kwan, “Because the illness of the Grand Royal Queen Dowager was serious, I could not help but offering a prayer out of worry and informed the Commander of the Military Training Corp 大王大妃殿病患危重, 故不勝感懷, 以屬祈禱事, 告于訓將.” SGJ 1877-9-24, 9b. Thearch Kwan’s revelation: “Now the Japanese emissary’s affair is no need for doubt and worry. You discuss things fairly with ordinary minds and do not behave recklessly. The Vice Minister Cho Yŏngha has various things to consult later, [thus if] he tells how things are going in person, sincerely serve him and perform without a doubt. 李生瑨也, 丁生鶴也, 兩人皆爲國之忠臣也. 今倭使之情, 可無疑慮. 汝等平心公議, 無妄作. 又趙判書寧夏, 後日種種有相議之事, 親近吐於事理, 無疑愼謹奉行.” Japanese affairs are also seen in SGJ 24a; 44a. There is also a record that alludes to a consultation about a secret agent to investigate Japan (wŏejŏng 倭情). SGJ 1877-10-6, 11a. 倭情之到京期約, 似在不遠矣. |

| 25 | Yun Soo Kim pointed out the images of Three Sages were installed at the Formless Altar in 1883 (Y.S. Kim 2008, p. 75), but the date of enshrinement at the Kwanwang Shrine precedes it by four years. |

| 26 | SGJ 1879-11-9. 聖帝奠座于文昌帝・孚佑帝兩聖奠座之中間. Based on another record, Thearch of Succour was placed in the East and Thearch of Literature in the West. SGJ 1878-1-27. 柱聯揭例, 東則孚佑帝聯, 西則文昌帝聯, 中則予聯. |

| 27 | SGJ 1879-2-13. 伏見救劫文中, 有木筆沙盤之句, 敢發愚意, 雖欲擧行, 知識暗昧, 敢此伏告伏俟聖旨. 卽因夢敎, 設于香案之訓. |

| 28 | SGJ 1880-10-2. 筆則以銅新造, 鸞鳥則如鳳……沙盘則以代紅紙, 長廣如席敷之, 甚好. 伏魔大帝示訓. |

| 29 | Byounghoon Park informed me of the possibility that Chosŏn spirit-writing had a different type from Qing China, in referring to the earlier practice of spirit-writing in Tonghak 東學 (Eastern Learning) with ink-brush on papers. According to him, spirit-writing played an important role in formation of scriptures and incantations, as well as the establishment of Tonghak lineagy since 1860s (B. Park 2020). |

| 30 | The Jade Emperor rarely descends directly on earth, but Yi Chinmo was blessed that the Jade Emperor descended to his house and gave a sacred name to him. SGJ 1877-6-17, 6b-7a. 玉皇上帝上天, 伏魔大帝奉命, 李瑨謨下字, 以淳字賜下……玉皇上帝降坐于李瑨謨家示訓. |

| 31 | Besides, the Formless Altar has been influenced by the Altar of Awakening Origin (Jueyuandan 覺源壇), the early ninteenth-century spirit-writing altar of Qing elite literati, that contributed to the compilation of Essentials of Daoist Canon (Daozang Jiyao 道藏輯要) in the 1810s. They worshiped Lü Dongbin as the first Patriarch and Liu Shouyuan 柳守元 as the second Patriarch. The Formless Altar also received a revelation from Liu Shouyuan, and Wendi compared the spirit medium Chŏng Hakku with the Qing literati Peng Dingqiu 彭定求 (1645–1719) and Huang Zhengyuan 黃正元 (fl. 1713–1755) (MC1, 1b). The altar members might be related to the reception of Essentials of Daoist Canon. As for the study of MC1, see (Y.S. Kim 2008; Y.G. Kim 2019). Huang Zhengyuan’s edition of Yinzhiwen tushuo 陰騭文圖說 explicitly influenced the creation of MC1, because major illustrations of MC1 are copies from Huang’s collection. As for Peng Dingqiu’s spirit-writing, see (Burton-Rose 2015). |

| 32 | KS 1876, vol. 2, 11a-11b. 嗚呼! 大劫臨矣. 吾等皆爲爾曹受罰, 爾等猶優遊自如耶? 恭惟帝心仁愛, 何忍以大劫茶毒斯民? 所以然者, 人心旣壞, 王法難容, 地獄之說疑誕, 來生之報爲迃, 不得已假手凶神, 授之鋒刃, 使一切元惡大憝, 分受其罪, 庶足以剔邪蕩穢, 興起良善. …… 大淸定鼎二百餘年, 昇平日久, 奸僞遂滋, 官吏紳民, 大率逆倫背理, 自絶於覆載. 上帝震怒, 已於數十年前, 令諸魔王降世, 流布瘟疫, 蜂起干戈. 爾時, 吾等聞命悚惕, ……乃偕諸神祗, 俯伏金闕, 哀懇暫緩, 容俟導化, 蒙恩准奏, 卽速開化. 於是遍處降乩, 不時降壇, 木笔沙盤, 千萬其言, 自謂可以普渡迷津矣. |

| 33 | The same passage was included in Guandi quanshu 關帝全書 edited and published by Huang Qishu 黃啓曙 in 1858 (GDQS 1858, vol. 24, 53b–55a; Guandi wenxian huibian 1995, vol. 6, pp. 662–65). Thus, the text was written between 1816–1858. See also (Goossaert 2017, pp. 520–22). |

| 34 | T3, 461b. 道成號佛, 無上至尊, 神徳光明, 無晝無夜. 從比丘衆, 六十二萬, 遊行世界, 開化群生. |

| 35 | The quotation in the Tang period Daoist Encyclopedia, shenming 神明 was replaced with renshen 人神. DZ1124, 8b. 其五篇真文合六百六十八字,是三才之元根,生天立地,開化人神,萬物所由. 故有天道・地道・神道・人道, 此之謂也. |

| 36 | It is not certain whether they referred to their names as “Daoist name (toho/daohao 道號).” There are usages that Chosŏn literati called ‘ho’, the name of the eminent literati scholar as ‘toho 道號,’ in which Dao means Confucianism. By “Daoist name,” I mean the name of one who pursues the Dao of the Three Teachings. |

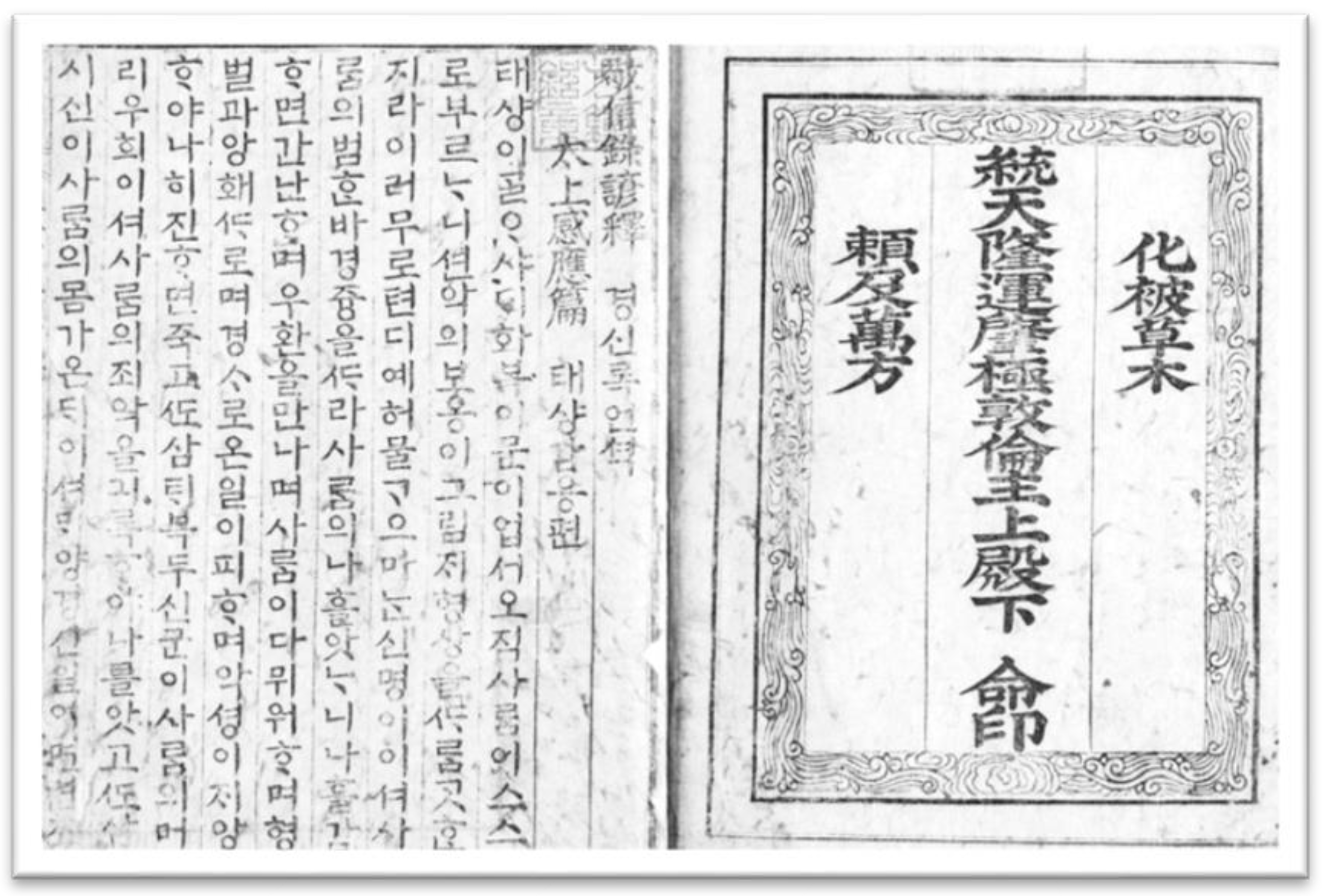

| 37 | Jingxinlu was compiled in 1769 and widely circulated in the eithgteenth century China (Sakai 1999–2000, vol. 2, 171–93). It was published in Chosŏn as the Kyŏngshin rok ŏnsŏk 敬信錄諺釋 at Buddhist temple Pulamsa 佛岩寺 in 1796, both versions of classical Chinese and vernacular Korean (HC 1986, vol. 2, pp. 1–26). I could not locate the 1796 edition. The 1880 edition was reproduced in HC 1986, v. 2. |

| 38 | KS 1876, vol. 3, 51b. 高尙鎭壯年艱嗣, 乙亥秋發願, 印施《敬信錄》一百部, 開印之月, 有孕產男. 而妻李氏產後, 血證沈綿瀕危, 尙鎭虔叩帝前, 妻病頓愈, 又印施《覺世眞經》一千卷. |

| 39 | MC1, Yŏngisŏ 緣起序, 1b. On the 18th day of the 12th month [1877], “Precious Book was dedicated to the Altar 寶典獻壇.” Annotation: “It means the Precious Book of the Three Sages (SSBJ). We received the command of the Sacred Thearch of Subduing Demons (i.e., Thearch Kwan), and proceeded together towards publication and distribution 三聖寶典, 承伏魔聖帝命, 彙進刊布.” It states that the Formless Altar members finished publication of the Precious Book to the Altar in 1877. |

| 40 | SSHG has no preface to inform us of the editor, but it has the same colophon (光緖六年庚辰季春刊印) as KHJS, which was printed by Kojong’s edict. Both were Kojong’s collection and reproduced in HC 1986, vol. 2. |

| 41 | SGJ 1880-2-18, 64b, 入侍, 下詢大內雜氛掃除事. SGJ 1880-3-10, 65b, 有三聖與周爺, 奉刀同進蕩滅之敎. |

| 42 | Chŏi Sŏnghwan published GYP as the classical Chinese version in 1848 and the Chinese–Korean bilingual version as the T’aesang kamŭng p’yŏn tosŏl ŏnhae 太上感應篇圖說諺解 in 1852. The 1880 edition was reproduced in HC 1986, vol. 3. |

| 43 | The first eight-character phrase was a revered title of Kojong, dedicated by court officials in 1872 (CWS 1872-12-24). It was incorporated in his posthumous title: 統天隆運肇極敦倫正聖光義明功大德堯峻舜徽禹謨湯敬應命立紀至化神烈巍勳洪業啓基宣曆乾行坤定英毅弘休壽康文憲武章仁翼貞孝太皇帝. |

| 44 | SGJ 1880-7-24, 72b 解曰: 有志慕道, 先訪其師, 不遠千里, 以遂其誠. 此卦回凡作聖之象. It is poem No. 27 from the Sacred Lots (KS 1876, vol. 3, 61a), which was spirit-writing of Thearch Kwan, received by Chŏng Hakku in 1876 (KS 1876, vol. 3, 85b). |

| 45 | As for the North Shrine, most scholars discuss it in the category of popular religion, especially based upon Murayama’s study of 1920s critics of what they regarded as superstition during Kojong’s reign (Murayama 1935, pp. 435–39; Jang 2004, pp. 417–18; KGS 1929). According to these figures, the North Shrine was built by Queen Min, who indulged in shamanism. However, the construction and function of the North Shrine should be reconsidered in the context of the Enlightenment project of Kojong. |

| 46 | I am grateful for Prof. Younseung Lee, who informed me on Kojong’s intention to establish Confucianism as a state religion. |

| 47 | SJW 1901-7-12; CWS 1901-8-25. 精忠節義之靈, 凜凜然亘千秋而不泯, 中正剛大之氣, 浩浩乎包六合而往來, 陰騭朕邦, 屢顯神威. |

| 48 | Tongnip Sinmun 獨立新聞 20 February 1899. “Volunteering in Restoration.” |

| 49 | Tongnip Sinmun 7 April 1896. “Ghost Worship and Idolatry.” It stated that the ghost worship and idoltry should be banned in the entire country, including not only the icons in ordinary people’s house but also the paintings in the state offices. It maintained that the prohibition helps making a progress of civilization. |

| 50 | Maeil Sinbo 毎日新報 3 May 1914. “The Overcrowded South Kwanwang Shrine at the Spring Festival.” |

| 51 | Shidae Ilbo 時代日報 24 April 1924. “The Demolition of Kwanwang Shrine: People are against it.” |

| 52 | Shidae Ilbo 24 November 1924. “Misfortune of Kanwang Shrines”; “Must Expelled Kwanwang Shrine (The Hall of Superstition).” |

| 53 | Koryŏ sibo 1 March 1939. “New Year Fortune Telling: Over Five Thousand People for Divination (關王廟買占人五千名突破).” |

| 54 | 1884-12-9, The testimony of Yi Chŏmdol (a servant of Kim Okkyun) in interrogation after the Kapsin Regime Change (Park 2009, p. 36). |

| 55 |  |

| 56 | As for this issue in the European Enlightenment, see (Saler 2006). Siginificant studies on this issue in Europe and East Asia are listed in footnotes 4 and 5 in (Katz 2015, p. 279). |

| 57 | The privatization of moral judgment is an important subject. Spirit-writing practice liberated people from formal religious institutions and clericalism and resulted in the individual encounter with one’s heart-mind—the unconscious dimension of humanity—from where spirit-writing descend. Recently, Daniel Burton-Rose showed the evolution of spirit-writing practice from the clan and community base into individual dreams and the self-fashioned practice. (Burton-Rose 2020). It should be studied the relevance between the contemplation on individual minds and East Asian modernization of morality. |

| Titles in the Book Catalog of the Studio of Collecting Jade | Place of Publication |

|---|---|

| Complete Works of the Patriarch Lü呂祖全書 (LZQS) Complete Biography of the Patriarch Lü 呂祖全傳 (LZQZ) | Qing China |

| Folios on Retribution感應篇 (GYP) Anthology for the Pious Faith 敬信錄 (JXL) Illustrated Records of Sacred Achievements 聖蹟圖誌 (KJ) Records of Sacred Achievements in the East of the Sea海東聖蹟誌 (HD) Commentary and Images of Precious Admonition 寶訓像註 Scripture of Luminous Sacredness 明聖經 Enlightenment by Passing, Miracles by Presence 過化存神 (KHJS) Scripture of Admonition of the Three Sages三聖訓經 (SSHG) | Chosŏn Korea |

| Kwansŏng-Jegun (K.) Guansheng Dijun (Ch.) 關聖帝君 Thearch Kwan | Pu-u Jegun Fuyou Dijun 孚佑帝君 Thearch of Succour | Munch’ang Jegun Wenchang Dijun 文昌帝君 Thearch of Literature | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Edition & Chosŏn Reprint Edition | Kwansŏng-jegun sŏngjŏk doji jŏnjip Guansheng dijun shengji tuzhi quanji 關聖帝君聖蹟圖誌全集 Complete Collection of Illustrated Records of Sacred Achievements of the Thearch Lord Sage Kwan [KJ] 1876 Chosŏn Reprint Edition of 19C Qing Edition Published in Kwanwang Shrine Pak Kyu-su, Preface Sŏ Chŏng, Preface Kim Ch’anghŭi, Postscript Kwansŏng-jegun bohun sangju Guansheng dijun baoxun xiangzhu 關聖帝君寶訓像註 Commentary and Images of Precious Admonition of Thearch Lord Sage Kwan 1882 Chosŏn Reprint Edition of [1731] 1850 Qing Edition Kwansŏng-jegun myŏngsŏng gyŏng Guansheng dijun mingsheng jing 關聖帝君明聖經 Scripture of Luminous Sacredness of Thearch Lord Sage Kwan 1883 Chosŏn Reprint Edition | Yŏjo jŏnsŏ Lüzu quanshu 呂祖全書 Complete Works of the Patriarch Lü [LZQS] [1744] 1868 Chinese Edition | Munje jŏnsŏ/Wendi quanshu 文帝全書 Complete Works of the Thearch of Literature [WDQS] [1743] 1775 Chinese Edition Munje sŏch’o/Wendi shuchao 文帝書鈔 Anthology of the Works of Thearch of Literature [WDSC] (1768) 1882 Chinese Edition Ŭmjŭlmun juhae/Yinzhiwen zhujie 陰騭文註解 Commentary on the Essay of Secret Virture [YZW] 1883 Chosŏn Reprint Edition Zhu Gui 朱珪, Commentary Yu Un, Postscript |

| Chosŏn Anthology from Chinese Edition & Chosŏn Original | Kwansŏng-jegun sŏngjŏk doji sokchip Guansheng dijun shengji tuzhi xuji 關聖帝君聖蹟圖誌續集 Sequel to Illustrated Records of Sacred Achievements of the Thearch Lord Sage Kwan [KS] 1876 Published in Kwanwang Shrine Haedong sŏngjŏk chi Haidong shengji zhi 海東聖蹟誌 Records of Sacred Achievements in the East of Sea [HD] 1876 Published in Kwanwang Shrine Kwahwa jonsin/Guohua cunshen 過化存神 Enlightenment by Passing, Miracles by Presence [KHCS] 1880 Published by Kojong’s Edict (Ch. with K. Translation) Kwansŏng-jegun myŏngsŏng gyŏng 關聖帝君明聖經 Scripture of Luminous Sacredness of Thearch Lord Sage Kwan 1886 (Ch. with K. Translation) | Simhak jongjon Xinxue zhengzhuan 心學正傳 Orthodox Transmission in Learing of Heart-Mind [SHJJ] 1878 Chosŏn Excerpt from LZQS Kim Ch’anghŭi, Preface (Ch. with K. Translation) Chunghyang jip Zhongxiang ji 衆香集 Collection of Various Fragrance [CHJ] 1881 Chosŏn Anthology of LZQS Kim Ch’anghŭi, Preface Yu Un, Postscript Yagŏn bojŏn/Yaoyan baodian 藥言寶典 Precious Book of Remedial Advices 1884 Anthology of CHJ | Kyegung ji/Guigong zhi 桂宮志 Record of the Cassia Palace [KGJ] 1881 Chosŏn Anthology of WDQS & WDSC Sin Chŏng-hŭi, Preface (1881) Yu Un, Postscript (1877) Munch’ang-jegun mongsu bijang gyŏng Wenchang dijun mengshou mizang jing 文昌帝君夢授秘藏經 Secret Scripture of Thearch of Literature Bestowed in Dream [MC1] 1878 Chosŏn Original Munch’ang-jegun sŏngse gyŏng Wenchang dijun xingshi jing 文昌帝君惺世經 Scripture of Awakening World of Thearch of Literature [MC2] 1878 Chosŏn Original Munch’ang-jegun tongsam gyŏng Wenchang dijun tongsan jing 文昌帝君統三經 Scripture of Unity in the Three Teaching of Thearch of Literature [MC3] 1878 Chosŏn Original |

| Samsŏng bojŏn/Sansheng baodian 三聖寶典 Precious Book of the Three Sages [SSBJ] 1877 Published by Formless Altar Samsŏng hun’gyŏng/Sansheng xunjing 三聖訓經 Admonition of the Three Sages [SSHG] 1880 The same colophon with KHJS (Ch. with K. Translation) | |||

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J. Enlightenment on the Spirit-Altar: Eschatology and Restoration of Morality at the King Kwan Shrine in Fin de siècle Seoul. Religions 2020, 11, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060273

Kim J. Enlightenment on the Spirit-Altar: Eschatology and Restoration of Morality at the King Kwan Shrine in Fin de siècle Seoul. Religions. 2020; 11(6):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060273

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jihyun. 2020. "Enlightenment on the Spirit-Altar: Eschatology and Restoration of Morality at the King Kwan Shrine in Fin de siècle Seoul" Religions 11, no. 6: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060273

APA StyleKim, J. (2020). Enlightenment on the Spirit-Altar: Eschatology and Restoration of Morality at the King Kwan Shrine in Fin de siècle Seoul. Religions, 11(6), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060273