The Donation Act of Hagi Constantin Pop’s Family for the Annunciation Church in Sibiu

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The description of the document

3. Transcription and Translation of the Document

3.1. Transcription

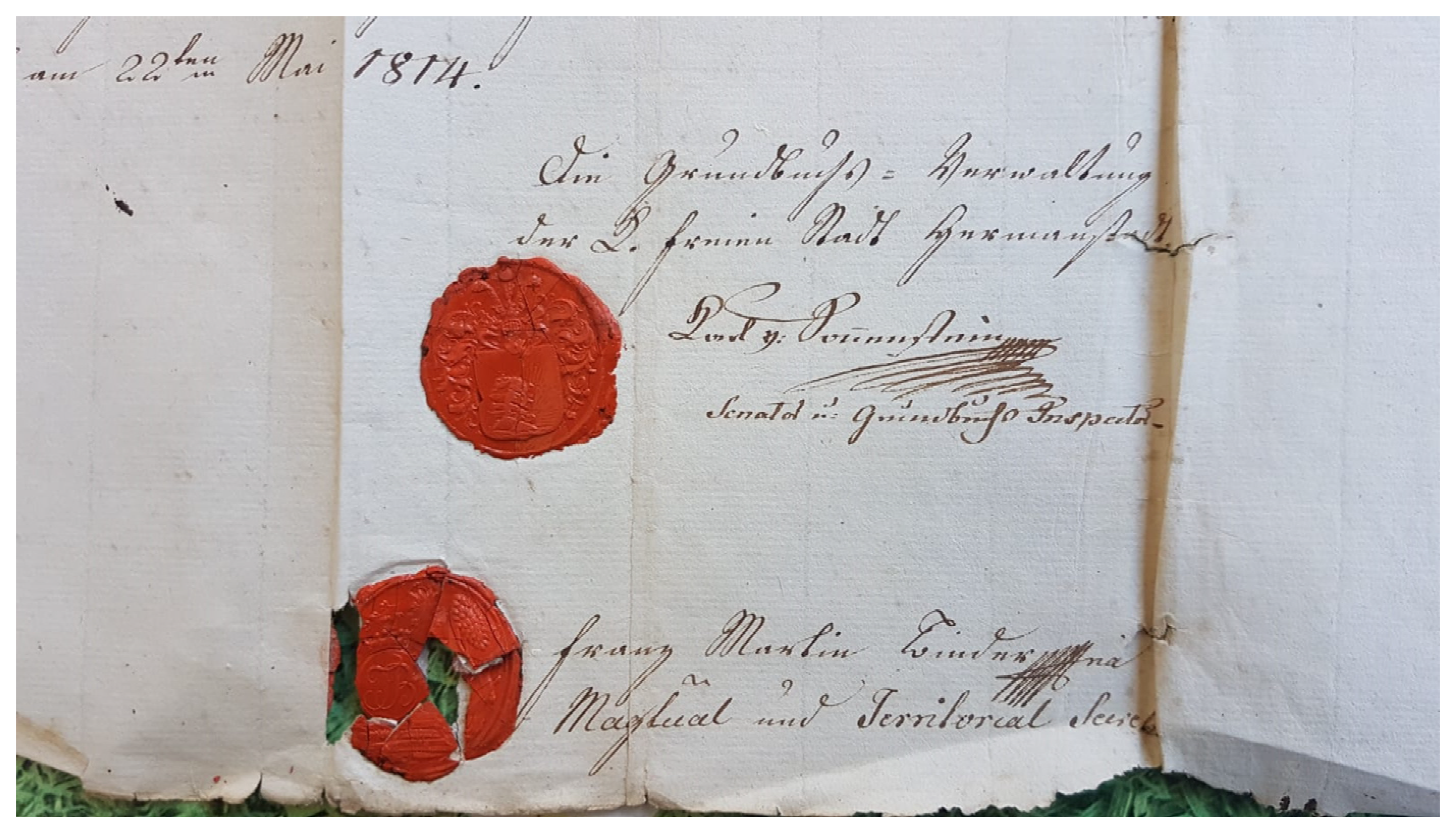

(page 1)Nro P. T. 34. (the coat of arms of Sibiu) 1814Kund und offenbar seyhiermit jerdermann, insonderheit aber denen, soes zu wissen gebühret, daß, nachdem der hiesige griechischeHandelsmann, und K.K. a Lieutenant in der Armee, Herr Zeno-vius Constantin Popp, im Namen seiner Frau Mutter derFrau Paulina verwittwetten Popp, geborene Lucca, nebst Ex-hibierung einiger Documente über die, zu der in der Joseph Stadtgelegenen, von seinem verstorbenen Herrn Vater Haggi Con-stantin Popp erbauten wallachischen Kirche, gehörigen Gründe,bey dem hiesigen Löblichen Magistrat das Ansuchen gemacht,womit statt dieser verschiedenen Documente, über den ganzen zuder gedachten Kirche gehörigen Terrain eine einzige Eigenthums-Urkunde ausgefertiget werden wolle, der Löbliche Magistrat, demdiesfälligen Gesuche der Bittstellerin Frau Paulina verwittwe-ten Popp willfahrend, unterm 7ten Februar 1814. Zahl 302/814.dieser Grundbuchs-Verwaltung wegen Ausfertigung der verlangtenEigenthums-Urkunde den Auftrag gemacht habe. Welch vorange-zogenem Magistratual Auftrage zu Folge dem auch die Grund-buchs-Verwaltung keinen Anstand genom[m]en hat, wegen Ausfer-tigung der eröfterten Eigenthums-Urkunde die nöthigen Anstal-ten zu tref[f]en; zu welchem Ende denn vorerst zur Ausmeßungdes mehrerwähnten Terrains geschritten worden, wobey sich denneine Länge von 36.° 4.’ und eine Breite von 29.° 3.´ mithinnein(page 2)ein Flächen-Innhalt von □ 1081.° 4.´ ergeben b; über welch ebenerwähnten in der Josephstadt, neben der wallachischen unverheirathetenWeibssperson, Fata c Floarje genannt, und dem Bach gelegenen Terrainvon 1081. □ Klaftern und 4. Schuh hiemit d bey Treue und Glaubenbezeuget wird, daß derselbe, von mehrbelobter Frau Paulina ver-wittweten Popp, als ihr rechtmäßiges Eigenthum, an die mehrerwähn-te, auf Unkosten ihres Herrn Gemahls erbaute Kirche geschenkt, mit-hin von nun an ein unbezweifeltes Eigenthum dieser Kirche seye.Zu weßen mehrerer Bekräftigung nicht nur in demhiesigen Stadt-Grundbuche die gehörige Vormerkung geschehen ist;sondern auch gegenwärtige Eigenthums-Urkunde expedit, und zurSicherheit der mehrbelobten Kirche in forma authentica extradit wird.Hermanstadt am 22ten Mai 1814Die Grundbuchs-VerwaltungDer K. e Freien Stadt Hermanstadt(stamp) Karl v. SonnesteinSenator und Grundbuchs-Inspector(stamp) Franz Martin BinderMag[istra]tual und Territorial Secre[tär] f(page 4) gNro IaEigenthums-UrkundeUeber den zur wallachischenNichtunierten Kirche in derJoseph Stadt gehörigenTerrain1868/815 (?)

3.2. Translation

(page 1)Nr. 34 (coat of arms of Sibiu) 1814To anyone who should be notified and acknowledged, especially those whoshould know this, the fact that, after the local Greek merchantand lieutenant in the imperial army, Mr. Zenovius Constantin Popp, on behalf of his mother, Mrs. Paulina, widow of Popp, born Lucca, in addition to submitting documents on lands located in Joseph Stadt, belonging to the Wallachian Church, built by his late father Haggi Constantin Popp, submitted the request to the worthy local magistrate, expressing her wish that, instead of these various documents, a single deed of ownership should be issued regarding the entire land belonging to the above-mentioned church, the worthy magistrate ordered to be given effect to this request of the petitioning lady Paulina, widow of Popp, and thus performed the assignment registered with the number 302/814 of February 7 in the local land administration, for issuing the requested property document. As a result of the magistrate assignment received, the administration of the land book did not raise objections against taking the necessary measures to issue the mentioned deed of ownership. For this purpose, the above-mentioned land was first measured, resulting a length of 36. ° 4.´ and a width of 29. ° 3.´, thereforeone(page 2)an area of □ 1081.° 4.´ It is hereby confirmed, honestly and in good faith, that the repeatedly above mentioned land, located in Josephstadt, near (the land) of the unmarried Wallachian female person named Țața Floarie and next to the river, with an area of 1081 □ fathoms and 4 feet, the rightful property of the much-praised widow Paulina Popp, is donated to the above mentioned church, built at the expense of her husband, and becomes henceforth the undisputed property of this church.To the multiple express confirmation, the proper record was made not only in the local urban land book, but the present deed of property was also sent, being handed over in authentic form to the much-praised church for guarantee.Hermannstadt, May 22, 1814Land book administrationOf the free royal city Hermannstadt(Stamp) Karl von SonnesteinSenator and inspector of the land book(Stamp) Franz Martin BinderMagistrate and territorial secretary(page 4)No. IaProperty documentRegarding the land located in Josephstadt,belonging to the Wallachian Orthodox Church1868/815 (?)

3.3. Notes

- “K.K.” is the abbreviation for kaiserlich-königlich (imperial royal), a title for Austrian officials and institutions before the formation of the dualist monarchy (1867).

- Signs are symbols for the fathom (°) and foot (´) as units of distance measurement. The square (□) is a symbol for fathoms and feet as units of surface measurement. The value of a Viennese fathom (klafter) in the first half of the nineteenth century differs slightly in the bibliographic sources: 1.896145 m (Jäckel 1824, p. 108); 1.896484 m (Czeike 2004, pp. 520–21). After the year 1871, 1 fathom became 1.896486 m (Czeike 2004, pp. 520–21). Initially, 1 surface fathom = 3.5979 m2 (Gernrath 1825, p. 573), and after 1871, it became 3.596652 m2 (Czeike 2004, p. 521). A total of 1 fathom contains 6 Viennese feet, so 1 foot measures approximately 0.316 m (Krüger 1830, p. 103).

- The letter “F” of the word “Fata” is similar to “T”. Thus, instead of “Fata” (girl, daughter of), it could be “Tata”, possibly the German transcription of the word “Țața”—a term of neo-Greek origin used for an older female person (similar to “my old woman”, “aunt”).

- Sic! Probably “hiermit”.

- “K”—the short form of Königlichen (royal). Hermannstadt was a royal free city. Very important cities in the Kingdom of Hungary and later in the Austrian Empire used to be designated by this term until 1876.

- Lit. “Magtual” (probably an abbreviation of the word “magistratual”) and “Secre”, probably “Secretär”, refer to categories of civil servants in the city administration. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, the chair of Sibiu had two “Magistratual-Secretäre” (Ludwig 1828, p. 472).

- Page 3 is blank.

4. Discussion

4.1. Historical Background

4.2. The Content of the Document and Its Importance

4.3. Events that Followed the Document of 1814

As it is also known to us–the authors of the memorandum showed at the end – the patron of the above-named church–the latter–Mr. Baron Zinovie H. Constandin Popp, together with all his legacy heir family, handed over the patronage of this church to Your Excellency and the followers of Your Excellency as openly shows the Widmungs-Urkunde14 of the acclaimed patronage. On 10 May 1854 he gave it to Your Excellency and on October 19 of the same year, you endured to receive it. On 31 October 1854 it has been confirmed under No. 20259/2559 by the Transylvanian Lieutenancy. Therefore, in this church there is nobody except Your Excellency to dispose.15

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

Archival Documents from Sibiu, Romania

BG (Abbreviation for Biserica din Groapă).ELS (Abbreviation for Evangelische Landeskirche in Siebenbürgen).BG, Donation Act of Paulina Pop, 22 May 1814, Parish Archive, doc. 660/1814.BG, Handover report, 27 October 1879, Parish Archive, doc. 3022/879.BG, Ioan Panovici, Ioan Oniţiu and Antoniu Bechniţiu to Andrei Șaguna, 3 February 1870, Parish Archive, doc. 31/870.BG, Donation act of Stan Ștefan Popovici, 1850, Parish Archive, doc. IV/1850N.BG, Andrei Șaguna to Ioan Panovici, 23 February 1850, Parish Archive, doc. 134/850.ELS, Auszüge der Traumatrikel Hermannstadt Band VI-a (1786–1812). Zentralarchiv der evangelischen Landeskirche in Siebenbürgen.Secondary Sources

- Abrudan, Ioan Ovidiu. 2013. Contribuţie la cunoaşterea unei valoroase piese de artă liturgică–iconostasul Bisericii din Groapă. Revista Teologică 2: 121–39. [Google Scholar]

- Arhidieceza Greco-Orientală din Transilvania (AGOT). 1897. Protocolul Sinodului Arhidiecezei greco-orientale române din Transilvania ținut la anul 1897. Sibiu: Tipariul tipografiei archidiecesane. [Google Scholar]

- Arhidieceza Greco-Orientală din Transilvania (AGOT). 1899. Protocolul Sinodului Arhidiecezei greco-orientale române din Transilvania ținut la anul 1899. Sibiu: Tipariul tipografiei archidiecesane. [Google Scholar]

- Arhidieceza Greco-Orientală din Transilvania (AGOT). 1900. Protocolul Sinodului Arhidiecezei greco-orientale române din Transilvania ținut la anul 1900. Sibiu: Tipariul tipografiei archidiecesane. [Google Scholar]

- Beethoven, Ludwig van. 1816. “Wellingtons Sieg oder die Schlacht bei Vittoria” für Orchester op. 91, nr. 2363, Wien: Steiner. Beethoven-Haus C 91/13, Bonn. Available online: https://da.beethoven.de/sixcms/detail.php?&template=dokseite_digitales_archiv_en&_dokid=bb:t00047857&_seite=1–4 (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Biserica Greco-Orientală Română din Ungaria și Transilvania (BGOR). 1900. Statutul Organic al Bisericei Greco-Orientale Române din Ungaria și Transilvania, cu un Suplement. Sibiu: Tiparul Tipografiei Arhidiecesane. [Google Scholar]

- Bodogae, Teodor. 1981. Sibiul, vatră de vieţuire ortodoxă românească. In Arhiepiscopia Sibiului–vatră de istorie. Edited by Mitropolia Ardealului. Sibiu: Editura Centrului Mitropolitan, pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Boicu, Dragoș. 2017. «Ca o cenuşotcă modestă, în dosul edificiilor, cari o încunjuoară»–pe urmele Bisericii companiştilor greci din Sibiu. Transilvania 1: 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Biserica Ortodoxă Română (BOR). 1949. Statutul pentru organizarea și funcționarea Bisericii Ortodoxe Române. Biserica Ortodoxă Română 1–2: 87–136. [Google Scholar]

- Brusanowski, Paul. 2007. Pagini din istoria bisericească a Sibiului medieval. Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană. [Google Scholar]

- Brusanowski, Paul. 2010. Învăţământul confesional ortodox român din Transilvania între anii 1848–1918: Între exigenţele statului centralist şi principiile autonomiei bisericeşti. Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană. [Google Scholar]

- Buschak, and Irrgang. 1879. Genealogisches Taschenbuch der Ritter-und Adels-Geschlechter, Vierter Jahrgang. Brünn: Druck und Verlag von Buschak & Irrgang. [Google Scholar]

- Czeike, Felix. 2004. Historisches Lexikon Wien. Vol. 3. H-L. Wien: K&S. [Google Scholar]

- Deuser, Hermann, and Richard Purkarthofer, eds. 2005. Deutsche Søren Kierkegaard. Band 1: Journale und Aufzeichnungen. Journale AA, BB, CC, DD. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Freyhan, Michael. 2009. The authenthic Magic Flute libretto: Mozart’s autograph or the first full-score edition? Plymouth: Scarecrow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gernrath, Johann Conrad. 1825. Abhandlung der Bauwissenschaften oder Theoretisch-praktischer Unterricht in der gemeinen bürgerlichen Baukunst, in dem Strassenbau (etc.). Brünn: J. G. Gastl. [Google Scholar]

- Goerg, Joseph Schmidt. 1978. Die Wasserzeichen in Beethovens Notenpapieren. In Beiträge zur Beethoven-Bibliographie, Studien und Materialien zum Werkverzeichnis von Kinsky-Halm. Edited by Kurt Dorfmüller. München: G. Henle, pp. 167–195. [Google Scholar]

- Härtl, Heinz, ed. 2018. Ludwig Achim von Arnim Briefwechsel IV (1807–1808). Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchins, Keith. 1996. The Romanians, 1774–1866. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iorga, Nicolae. 1906a. Negoţul şi meşteşugurile în trecutul românesc. București: Minerva. [Google Scholar]

- Iorga, Nicolae. 1906b. Scrisori de boieri şi negustori olteni către Casa de Negoţ sibiană Hagi Pop publicate cu note genealogice asupra mai multor familii. București: Atelierele grafice SOCEC & Comp. [Google Scholar]

- Iorga, Nicolae. 1906c. Scrisori şi inscripţii ardelene şi maramureşene. II. Inscripţii şi însemnări (formând volumul XIII din «Studii şi documente cu privire la Istoria Românilor»). București: Atelierele grafice SOCEC & Comp. [Google Scholar]

- Jäckel, Joseph. 1824. Zimmentirungs Lexikon für alle Handels-und Gewerbsleute nach den österreichischen Zimmentirungsschriften. Wien: Anton Strauß. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Hans. 1969. Die Schrift in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, Johann Friedrich. 1830. Vollständiges Handbuch der Münzen, Maße und Gewichte aller Länder der Erde. Quedlinburg and Leipzig: Verlag Gottfried Basse. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, Franz. 1828. Neuestes Conversations-Lexicon, oder Allgemeine Deutsche Real-Encyclopädie für gebildete Stände. Wien: Franz Ludwig, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Mildenberg, J. H. Benigni v. 1837. Handbuch der Statistik und Geographie des Großfürstenthums Siebenbürgen. 2. Heft. Hermannstadt: N. H. Thierry’s Buchhandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Păcurariu, Mircea. 2002. Cărturari sibieni de altădată. Cluj-Napoca: Dacia. [Google Scholar]

- Păcurariu, Mircea. 2006. Scurta istorie a vieţii bisericeşti a Sibiului până la începutul secolului al XX-lea. Revista Teologică 2: 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pleimes, Wilhelm aus Roesrath. 2018. Johann Michael Karl Conrad von Sonnenstein. Genealogische Datenbasis. Available online: https://gedbas.genealogy.net/person/show/1216406736 (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Reichsministerium für Wissenschaft, Erziehung und Volksbildung und der Unterrichts-Verwaltung der Länder. 1941. Schreibunterricht. RdErl. d. RMfWEV. v. 1. September 1941–E II a 334/41 E III, Z II a. Deutsche Wissenschaft Erziehung und Volksbildung. Amtsblatt des Reichsministeriums für Wissenschaft, Erziehung und Volksbildung und der Unterrichts-Verwaltung der Länder 17: 332–33. Available online: https://goobiweb.bbf.dipf.de/viewer/object/991084217_0007/347/ (accessed on 17 January 2020).

- Roth, Harald. 2006. Hermannstadt. Kleine Geschichte einer Stadt in Siebenbürgen. Köln, Weimar and Wien: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Seidl, Johannes. 2006. Schriftbeispiele des 17. Bis 20. Jahrhunderts zur Erlernung der Kurrentschrift. Ubungstexte aus Perchtoldsdorfer Archivalien. Percholdsdorf: Marktgemeinde Percholdsdorf. [Google Scholar]

- Sigerius, Emil. 1928. Vom alten Hermannstadt. 3 Folge. Hermannstadt: Verlag Krafft & Drotleff. [Google Scholar]

- Soroştineanu, Valeria. 2006. Despre catedrala mitropolitană din Sibiu. Transilvania 4: 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Soroştineanu, Valeria. 2010. Cimitirul Bisericii din Groapă din Sibiu. Studia Universitatis Cibiniensis. Series Historica 7: 135–52. [Google Scholar]

- Soroştineanu, Valeria. 2014. Biserica din Groapă și grecii din Sibiu. In Interferenţe culturale în Sibiul secolelor XVIII–XX. Edited by Ioan Popa and Mihaela Grancea. Sibiu: Astra Museum, pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner-Welz, Sonja. 2003. Von der Schrift und den Schriftarten. Mannheim: Reinhard Welz Vermittler Verlag Mannheim. [Google Scholar]

- Teutsch, Friedrich. 1907. Geschichte der Siebenbürger Sachsen für das sächsische Volk. 2. Band. Hermannstadt: Druck und Verlag von W. Krafft. [Google Scholar]

- Ventresca, Marc J., and John W. Mohr. 2017. Archival Research Methods. In The Blackwell Companion to Organizations. Edited by Joel A. C. Baum. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405164061.ch35 (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Voorn, Henk. 1960. De papiermolens in de provincie Noord-Holland. Haarlem: Papierwereld. [Google Scholar]

- Wien, Ulrich Andreas. 2017. Siebenbürgen–Pionierregion der Religionsfreiheit: Luther, Honterus und die Wirkungen der Reformation. Hermannstadt and Bonn: Schiller Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Ziesche, Eva, and Dierk Schnitger. 1995. Der handschriftliche Nachlass Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegels und die Hegel-Bestände der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Preussischer Kulturbesitz. Teil 2: Die Papiere und Wasserzeichen der Hegel-Manuskripte. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The Saxons believed that their freedom and autonomy would be threatened if the Hungarian nobility received the right of concivility, because the nobles did not obey the same laws. |

| 2 | The name comes from the German Meier, by which the free peasants who worked the land of an owner were designated. |

| 3 | Other English renderings are Church in the Pit or Church in the Ditch. |

| 4 | BG, Donation Act of Paulina Pop, 22 May 1814, Arhiva parohială, doc. 660/1814. |

| 5 | We managed to identify only one document from 1845, written in Serbian. |

| 6 | BG, Handover report, 27 October 1879, Arhiva parohială, doc. 3022/879. |

| 7 | Many personalities of the time—for example, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (Ziesche and Schnitger 1995, p. 72), Clemens Brentano (Härtl 2018, pp. 1962, 1983), or Søren Kierkegaard (Deuser and Purkarthofer 2005, p. 384)—used that type of paper for correspondence or diary entries. Ludwig van Beethoven wrote his late compositions on C&I Honig paper (Freyhan 2009, p. 74; Goerg 1978, pp. 180–81). Paper with the same watermark as the one appearing on the document to which the present study refers was used for the score of the composition “Wellingtons Sieg, oder die Schlacht bei Vittoria”, printed in 1816 (Beethoven 1816; https://www.loc.gov/item/consortium.bh_Bo59_FT00047857/). |

| 8 | All quotations from German and Romanian sources in this article have been translated into English by the authors. |

| 9 | Kurrent writing developed from the minuscule Gothic writing of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and reached a stable form in the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries, which later witnessed only minor changes brought to the letters (Jensen 1969, pp. 526–37). |

| 10 | BG, Ioan Panovici, Ioan Oniţiu and Antoniu Bechniţiu to Andrei Șaguna, 3 February 1870, Arhiva parohială, doc. 31/870. |

| 11 | ELS, Auszüge der Traumatrikel Hermannstadt Band VI-a (1786–1812). p. 189. |

| 12 | BG, Donation act of Stan Ștefan Popovici, 1850, Arhiva parohială, doc. IV/1850N. |

| 13 | BG, Andrei Șaguna to Ioan Panovici, 23 February 1850, Arhiva parohială, doc. 134/850. |

| 14 | Certificate of donation (German). |

| 15 | BG, Ioan Panovici, Ioan Oniţiu and Antoniu Bechniţiu to Andrei Șaguna, 3 February 1870, Arhiva parohială, doc. 31/870. |

| 16 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oancea, C.; Abrudan, I.O. The Donation Act of Hagi Constantin Pop’s Family for the Annunciation Church in Sibiu. Religions 2020, 11, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030108

Oancea C, Abrudan IO. The Donation Act of Hagi Constantin Pop’s Family for the Annunciation Church in Sibiu. Religions. 2020; 11(3):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030108

Chicago/Turabian StyleOancea, Constantin, and Ioan Ovidiu Abrudan. 2020. "The Donation Act of Hagi Constantin Pop’s Family for the Annunciation Church in Sibiu" Religions 11, no. 3: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030108

APA StyleOancea, C., & Abrudan, I. O. (2020). The Donation Act of Hagi Constantin Pop’s Family for the Annunciation Church in Sibiu. Religions, 11(3), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11030108