1. Introduction

Australia is becoming increasingly religiously diverse. This diversity is often described as threatening to social cohesion, and the maintenance of social cohesion is often identified as a policy goal in response to this increasing diversity (

Andrews 2007;

Jupp 2007;

Markus and Kirpitchenko 2007;

Markus 2018;

Turnbull 2018). This paper critically examines the utility of the concept of social cohesion as both a theoretical concept and as a policy goal. We begin by presenting Census statistics that chart religious diversity in Australia and some of the opportunities and challenges it presents. Then, we consider the concept of social cohesion, and some alternative conceptualizations of how to live together respectfully amidst diversity. This is followed by a review of current Australia policies in response to rising religious diversity.

We find social cohesion to be a problematic and ambiguous concept that needs to be used with care in any policy considerations. Concepts such as deep equality, cosmopolitanism, and reasonable pluralism provide more useful ways of conceptualizing the challenges and opportunities generated by religious diversity. We argue that the significant changes to Australian culture and social structures wrought by increasing religious diversity can be understood as an opportunity to form new social relationships and ways of engaging with that diversity. These may be experienced as destabilizing of traditional cultural practices and social structures. This destabilization is often interpreted as a threat to social cohesion. However, we argue that it can also be understood as resistance to, and agonistic engagement with, new forms of respectful engagement with diversity.

The paper critically examines the use of the concept of “social cohesion” both in existing academic studies and in policy statements on Australian government websites. Methodologically, this allows us to compare the theoretical debate with the practices of government policy. It also highlights how, for discussions of social cohesion, empirical description is bound up with sets of ideals, policy goals, and the interests of particular sections of society. The longer theoretical discussion is important to demonstrate this as a theoretical issue. We, then, use the review of government statements to illustrate how this operates in policy and practice.

Australia has a long history of social stability, with broad support for inclusion and equality, and not without good reason prides itself on being a successful multicultural society. However, there are conspicuous areas of specific failure, the foremost of which has been the ongoing mistreatment of Indigenous Australians. The pursuit of social stability and cohesion has often been associated with the maintenance of privilege and forms of social exclusion. Examples include the White Australia policy in the 20th century, and before that restrictive policies on ethnic and religious minorities such as the treatment of Irish Catholics, Chinese, and Japanese settlers in the 1800s. Racism also persists in Australia, with disturbing levels of Islamophobia and anti-Semitism, and ill-treatment of asylum seekers (

Bouma and Halafoff 2017b;

Markus 2018).

As with many other nations, “Australia has become more coercive in response to the fear of terrorism” (

Jupp 2007, p. 11). Recent decades have seen a shift from policies designed to assist ethnic and religious minorities with language and welfare support to “anxiety about religion, values, and loyalty” (

Jupp 2011, p. 141). Whilst the threat of terrorist violence is certainly very real, the pursuit of shared values to preserve social cohesion represents a defensive response reflecting a Hobbesian perception of diversity as a threat to social order. This is reflected in a range of post-September 11, 2001 policies that are more explicitly integrationist rather than multicultural. For example, in 2007, the then Minister for Immigration and Citizenship said: “the Australian Government has in place policies and programs that complement the immigration program and strengthen social cohesion. They seek the effective integration of migrants into Australian life” (

Andrews 2007, p. 46).

Internationally, the concept of social cohesion began to appear in policy documents such as those produced by the OECD at the beginning of this century. The use of the term social cohesion appears to have come as a response to growing diversity in an increasingly globalized world and the idea that there was the potential for a clash of cultures, particularly between Western and Islamic values (

Markus and Kirpitchenko 2007). In the last decade a “diversity paradigm” has come to dominate across Europe (

Griera 2018, p. 44), hinging “on the ideas of social cohesion, anti-radicalization, and religious freedom(s)” (see also

Jackson 2019, pp. 264–85). This “diversity paradigm” began to also emerge in Australia particularly at the national level and in New South Wales at the turn of the 21st Century, however, the state of Victoria chose to promote an alternate approach to social cohesion that celebrates difference and respect, rather than integration around values and homogeneity. While social cohesion is often raised in relation to ethnic diversity and other forms of social division and inequality, in this analysis we focus primarily on religious diversity.

2. Religious Diversity in Australia

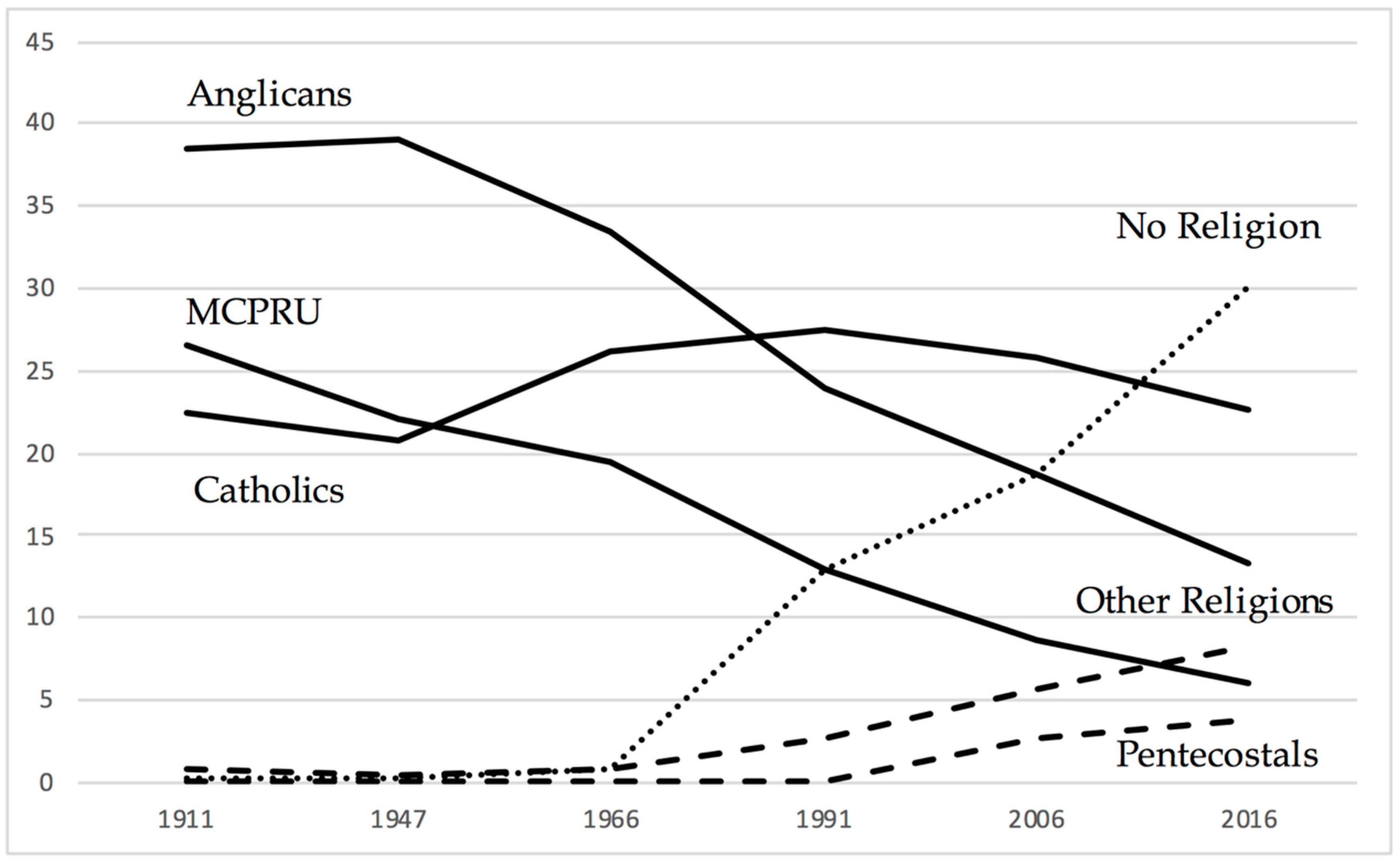

Australia has been transitioning from being a predominantly Christian nation, in perception if not in reality, to a nation of significant religious diversity. One major element in this transition is the dramatic growth in the number of people who identify as “not religious” (those who select “none” when responding to the census question about which religion they identify with). Those identifying as not religious constitute nearly one third (31%) of the population based on the 2016 census data (see

Figure 1). While there is significant within-group diversity, responses on the census include only a small number of atheists and agnostics, suggesting that the vast majority of “nones” are not particularly anti-religious. A recent survey of young Australians also includes those who identify as “spiritual but not religious” among the “nones” (

Singleton et al. 2018). The proportion of people identifying as Catholics has remained relatively steady, but this level has been maintained in part due to immigration from countries with largely Catholic populations. This resulted in a substantial increase in ethnic diversity within Catholicism in Australia (

Bouma 2015). The increase in numbers of Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs also reflects changing migration patterns and contains significant ethnic diversity (

Bouma and Halafoff 2017a). The growth in Pentecostals during the 1990s appears to largely reflect switching from other Christian denominations, with migration making an increasing contribution to Pentecostal numbers since 2006 (

Newton 2018). The decline of “traditional”, or mainstream, Christians is more pronounced than the census statistics suggest, with as few as 5% of those who identify as Anglicans attending church in any given week, and 15% of Catholics (

Bellamy and Castle 2004). In contrast, 73% of Pentecostals attend church in any given week (

Bellamy and Castle 2004).

The growth in the number of people who are “not religious” presents a major challenge to the negotiation of religious diversity, particularly in the public sphere. In Australia, these tensions have focused on “secularity”.

Tom Frame (

2009, p. 269) argues that the growth of secularity is radicalizing religious people as “a chasm has opened between the public objectives of those pursuing some forms of secularity and the religious aspirations of some faith communities”. There have been concrete expressions of this in Australian debates about religion in schools (

Maddox 2014) where, despite consistent expert advice, there remains strong resistance to introducing programs that educate students about diverse religions and non-religious worldviews. This resistance mainly comes from religious communities who prefer to provide confessional religious instruction programs in their own tradition in religious and secular state schools (

Halafoff 2015). However, the fear of an aggressively secular society may be more an imputed rather than real. As

Bouma (

2017, p. 1) points out: “declaring ‘no religion’ [on the census] does not mean that someone is anti-religious, lacking in spirituality, or an atheist. It means they just do not identify with a particular organized form of religion”. Furthermore, the growing number of people who identify as “not religious” needs to be distinguished from a hard “secularism” as a policy perspective. The two are often unrelated.

The growing numbers of Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, and Sikhs in Australia are also often highlighted in discussions of social cohesion and diversity. For example, incidents of discrimination and violence associated with Islam are escalating in Australia, many of which involve Islamophobia, that is, an exaggerated fear of Islam (

Markus 2018). Public anxiety has been heightened by poorly-informed discussions about Islamic law—Shari’a—and the fear of extremist Muslims. The 2018 Scanlon Foundation survey found 19% of Australians report discrimination “because of your skin color, ethnic origin or religion”, a level that is “significantly higher than the 9% to 10% from 2007 to 2009” (

Markus 2018, p. 26). Islamophobia is a particularly acute problem. While the majority of Australians express low levels of Islamophobia, 10% of Australians appear highly Islamophobic (

Hassan and Martin 2015). Terrorist-related violence is thankfully quite rare in Australia, although it remains a key policy concern. Recent incidents of white nationalist terrorist violence in Australia and New Zealand highlight that the threat of violence can arise in various quarters (

Barton 2019).

“Social cohesion” is often is often portrayed by media, politicians, and especially right-wing social actors as the thing that is under threat as a consequence of increased religious and ethnic diversity (

Schaeffer 2014). We suggest expressions of concern about “social cohesion” can be better understood as a response to fears associated with social change. In Australia, as Christian culture and language loses its relevance and dominance in the public sphere, conservative Christians have resisted attempts to find new forms of public discourse that respect diversity. The transition to a diverse and increasingly pluralistic society can be difficult for those who have previously had privilege and power. For example,

Nelson and associates (

2012) note that the claim that Australia is a “Christian country” is found in 40% of submissions to the 2011 Inquiry into Freedom of Religion and Belief (

Bouma et al. 2011). They argue that this is used to purposefully undermine any “movement towards more inclusive social policy and protection of rights” (

Nelson et al. 2012, p. 297). We argue that there are alternate pluralistic and inclusive discourses and frameworks for responding to diversity, “Responding to the new diversity in an inclusive way means relinquishing rightness and power by those who are accustomed to having it, rather than claiming victim status” (

Beaman 2017b, p. 18).

The perception that a sharp increase in diversity presents a threat to social cohesion is an international trend. For example,

Furseth et al. (

2018) trace the growing diversity of religion in the Nordic countries, mostly as a consequence of changed immigration beginning in the 1980s. Calhoun, in his preface to this work, links this trend to social cohesion, “In some of the most interesting and important passages of this book, the authors trace the loss of cohesive values and a shared framework for public discourse” (

Calhoun 2018, p. ix). This is a nostalgic conception of social cohesion that is inherently problematic. We turn now to a consideration of the literature on social cohesion and alternative concepts to understand the consequences of increasing religious diversity.

3. Social Cohesion

Our concern is that many scholars and policy makers rush to discuss what they think is essential to produce social cohesion without first declaring what they mean by social cohesion (see also

Chan et al. 2006). Part of the problem with the term “social cohesion” is that it is often seen as uncritically positive, when some of the ways social cohesion operates can be inimical to democratic, participatory, and egalitarian social values. Furthermore, we highlight the many ways religion operates to produce or undermine social cohesion (depending on the level of analysis). We also suggest some alternative theoretical conceptions that could be used in place of social cohesion that are more critical and just.

Social cohesion was classically problematized by Durkheim (

Durkheim [1893] 2013) who was driven by the history of revolutions in France to ask the following: What holds societies together? and What prevents violent conflict? This represents an inherently conservative starting point that seeks to preserve the current order for fear of radical disruption. Durkheim’s (

Durkheim [1893] 2013) answer was that societies are held together by interdependence, pointing to our mutual reliance on each other. He did not promote the “cultural integration” of society, such as that provided by religions pre and post Westphalia; rather social solidarity was a functional requirement, an emergent property from social interaction among diversities which could lead to corporate expression. The risk with Durkheim’s functionalism is that differentiated and interdependent roles can become a cipher for privilege and power (

Portes and Vickstrom 2011). Durkheim’s conception stands in marked contrast with the position of Weber (

Weber [1904–1905] 2001) who, facing a long period of social stability in Germany, wondered how societies could change and looked to cultural innovation as the cause of that change, with a view that social change could be constructive. We argue for an approach to religious diversity that draws on both these traditions.

Much of the academic literature on social cohesion reflects the Durkheimian approach, providing lists of factors that are necessary for a social democracy to hold together. For example,

Merlin Schaeffer (

2014, p. 9) reviews a range of definitions of social cohesion and argues for two components that are cognitive and behavioral, “Social cohesion has a cognitive component, in feelings of trust, and trust-related sentiments. It has a behavioural component in the forms of civic infrastructure, and in membership in associations and other engagements in public social life” (see also

Markus and Kirpitchenko 2007;

Economou 2007). Such definitions conflate the evaluative and the descriptive aspects of social cohesion, assuming that social cohesion is unproblematically positive.

Some reviews of the literature on social cohesion recognize a policy-oriented dimension to social cohesion but stop short of a more critical engagement. For example, Joseph Chan and associates (

Chan et al. 2006, p. 279) argue there are two main “traditions” of research on social cohesion, one that is more academic and focuses on social integration and social stability, and the other that is more policy oriented, “problem-driven” and developed in a response to “new social cleavages”.

Berger-Schmitt (

2000, p. 4) similarly differentiates two main dimensions in academic studies of social cohesion, those that focus on “the strengthening of social relations, interactions and ties” and those relating to the “reduction of disparities, inequalities, and social exclusion”.

A more critical approach is developed by

James Beckford (

2015) in his analysis of the related concept of “community”. He argues that much policy and academic discussion is uncritically positive about faith communities, assuming that either they can be deployed instrumentally to assist in the provision of social welfare and other policy goals, or that they are “intrinsically valuable in themselves precisely because they embody non-instrumental values” (

Beckford 2015, p. 233). These approaches ignore the way faith communities can be ambivalent, contributing to peacebuilding, yet also to violence, by being at times exploitative, riven by conflict, and having factions with substantially differentiated goals (

Appleby 2000).

We suggest that definitions of social cohesion need to be more explicit and that social cohesion is about social stability, which may or may not be something to which policy makers or other actors aspire. Social policies that pursue social cohesion tend to defend existing structures of privilege because social change is often experienced as disruptive. The relationship of social cohesion to privilege, equality, and respect is an issue which must be addressed to arrive at a satisfactory understanding of social cohesion. Put another way, the concept of “social cohesion” contains an inchoate notion of an ideal society, and policies designed to protect social cohesion often reflect the priorities of one or another group or ideology.

Dobbernack (

2010, p. 151) makes a similar argument that social cohesion operates as a “social imaginary” that has both “descriptive and evaluative” functions that serve to energize particular policies and practices. Functionalist models of society uncritically valorize shared values and sameness as sources of social cohesion. Taken to its extreme logical conclusion, this leads to “strongly coercive central government approaches to social order [that] provide a form of social cohesion” (

Bouma 2011, p. 51). This is problematic not only at the level of authoritarian dictatorships, but more subtly in policies and practices that attempt to institutionalize sameness. In light of increased religious diversity in Australia, we are interested in models of social cohesion that embrace democratic and pluralistic approaches to diversity.

By contrast, social cohesion is not always conceived in this way. For example,

Bouma and Ling (

2007, p. 80) state that “Social cohesion refers to the ability of a society or a group to so coordinate its resources [and people] to produce what it needs to sustain and reproduce itself”. Societies require the production and consumption of goods and services along with sufficient reproduction of population, culture, and knowledge, therefore, to support, nurture, and enhance life. This definition does not presume that the pursuit of social cohesion will always be consistent with the values of democratic participation, respect, and equality. This definition does not claim that it is necessary to maintain this or that particular feature of a society, but argues that many particular arrangements, social structures, can, and historically have, provided what is needed for a society to produce and reproduce itself.

When articulated as policy goals in response to diversity, “social cohesion”, and similar concepts such as “tolerance”, and ”accommodation” can easily become ciphers for the defense of privilege. The problematic nature of authoritarian forms of social cohesion in Australia is explored in depth by

James Jupp (

2018). He presents the history of migrant settlement in Australia as being a contest between the law and order power brokers such as prison guards, establishment powers, and captains of industry. He contrasts the pursuit of social cohesion with the freer assembly and cooperation of those who are “different” to produce the creative solutions to the problems facing the society. Social cohesion becomes something sought, or more likely, imposed for the benefit of the few. Or, to use a more recent example,

Lori Beaman (

2017a, p. 3) “questions the work done by the concepts of tolerance and accommodation” arguing that they are strategies for “effectively maintaining the status quo, preserving the hegemony of religious majorities and indeed of cultural majorities”.

In contrast, we argue for a set of relational practices that are democratic, participatory, and egalitarian, whether these be in everyday life, or in legal or political decision making. These are enabled by processes by which a society organizes itself and its resources. They can also be assessed in terms of outcomes, that is, justice or injustice and peace, stability, and progress (but, progress toward what?). Some contemporary terms that have been used to explore some of these issues include cosmopolitanism, deep equality, and reasonable pluralism. These terms provide useful alternatives to “social cohesion” as both theoretical conceptions and policy goals.

Similar to “social cohesion”, other conceptions such as “cosmopolitanism”, “deep equality”, and “reasonable pluralism” are double-edged concepts, having both a descriptive and a normative dimension. Cosmopolitanism describes an empirical social reality as nation states and national ethnic and religious identities are becoming less salient, not least as a consequence of substantial international migration. Cosmopolitanism as an empirical descriptor of a cultural form describes the growth in ethnic and religious diversity in many cities, and, as a consequence, the growing number of individuals whose values stem from a sense of being part of a cosmopolitan world. However, cosmopolitanism also describes a policy orientation, and critical commitment, to “an optimistic and practical vision—whereby seeking mutual understanding and enabling nonviolent critique can increase equitable participation in responsible local and global governance” (

Halafoff 2013, p. 169).

Anna Halafoff (

2013, p. 20) cites Kant to develop a conception of cosmopolitanism that “emphasizes the importance of equal rights for all and a belief that non-state actors, including religious actors, can collaborate with state actors by offering constructive criticism through deliberative processes as they strive collectively toward “perpetual peace”. Her model also draws on a Habermasian deliberative democracy framework (compare

McGhee 2012).

Halafoff (

2013) sets up the key problem as a conflict within societies between cosmopolitan and anti-cosmopolitan actors, who are threatened by processes of globalization and advances in rights for minorities, and respect for gender, sexuality, cultural, and multispecies diversity.

In a related, but significantly different, way Lori Beaman argues that “deep equality” is “as an achievement of day-to-day interaction, and is traceable through agonistic respect, recognition of similarity, and a concomitant acceptance of difference, creation of community, and neighbourliness” (

Beaman 2017a, p. 13). Beaman sees the key to equality as an outcome of these microprocesses. Policy responses that focus on legal rights and legislation can easily miss these everyday social practices that make equality possible. However, this is not to ignore the importance of social structures. As

Beaman (

2017a, p. 12) puts it, there are “structural impediments” to deep equality, including “poisonous religious texts and leaders, laws and embedded practices rooted in hatred and otherness”.

Robert Jackson (

2018, p. 4) cites Rawls to argue for “reasonable pluralism”, “Liberal societies have a plurality of reasonable but irreconcilable comprehensive moral, religious and philosophical positions; this is ‘reasonable pluralism’”. Here Jackson echoes

Connolly’s (

2005, p. 34) arguments for pluralism, where “the basic challenge of ethico-political life in late modern territorial states is how to negotiate honorable public settlements in settings where interdependent partisans confess different existential faiths and final sources of morality”. For Jackson and Connolly, the limit to diversity lies in the refusal to tolerate those who refuse to “tolerate conflicting comprehensive views” (

Jackson 2018, p. 4). Such limits can be set by, for example, religious anti-discrimination legislation.

Douglas Ezzy (

2013, p. 209) takes up this point, arguing that anti-discrimination legislation encourages religious actors to “wrestle with their own fears”. That is to say, it is not necessary that everyone becomes “neighborly” and accepting of diversity. There will always be some members of society who feel fear and perhaps hatred toward others. Ezzy’s argument is that such views must be allowed in a pluralistic society, within reasonable limits, and delineating these limits is exactly the role of anti-discrimination legislation. This draws on a similar understanding of arguments that a key part of social cohesion is “the presence of public institutions capable of adequately managing social conflicts” (

Markus and Kirpitchenko 2007, p. 31). It also leads back to

Greg Barton’s (

2019) earlier point about the dangers of right-wing nationalism and the question of when intervention is required to prevent the translation of such views into destructive forms of violence. If the primary commitment is to policies that encourage respectful, relational, participatory practices, such as cosmopolitanism, deep equality, and reasonable pluralism, it may also be the case that views that challenge such practices are to be respectfully ”tolerated”, within reasonable limits so that they do not cause harm to others.

These disparate theories identify a variety of policy goals and social ideals which include: sameness and shared culture, respect through dialogue, legal authority, everyday respect, social capital, and economic opportunity. These do not have uniform consequences for the goals of democratic participatory egalitarianism. They can be conceptualized as parallel processes. The challenge is to conceptualize how they operate and intersect. In some contexts, social cohesion, and the processes that enable it, can be oppressive. In other contexts, it can be liberating and nurturing of respectful democratic engagement. Cosmopolitanism, deep equality, and reasonable pluralism, all flag aspects of these processes. An analysis of social policies and practice designed to maintain social cohesion needs to engage with the complex and ambivalent nature of social cohesion. Strategies and policies designed to promote respect for people of diverse religions may not always improve “social cohesion”, if “social cohesion” is conceptualized in ways that reflect the interests and experiences of privilege. Put another way, policies and practices informed by the pursuit of cosmopolitanism, deep equality, and reasonable pluralism can create discomfort and even distress among some sections of society, which could be interpreted as undermining social cohesion, and this may be part of the process of moving to new forms of respectful engagement with an increasingly diverse society.

In the next section of the paper we review government responses to Australian religious diversity. This provides a concrete empirical illustration of the complexity and diversity that we have been discussing theoretically. We then return to a theoretical discussion of strategies of responses to religious diversity that seek to maintain social cohesion.

4. Australian Government Policy Responses to Religious Diversity

We surveyed Australian government websites to identify what they said about religious diversity and the strategies they describe as responses to this diversity. The survey was conducted in March 2019. Our aim was to identify statements that are easily accessible and placed most prominently on websites. We conducted a Google search on terms such as “religious diversity”, “multicultural policy”, “interfaith”, and “multifaith”. Government websites were also visited and explored. This survey provided some indication of the complexity of government responses to religious diversity across Australia. Australia has a national federal government, six state and two territory governments, and local governments. While local governments play a key role in responding to diversity, in this paper we focus on the federal and state and territory governments. Websites from both the federal and the state and territory levels of government were surveyed as policy responses to religious diversity fall into the responsibilities of both levels of government.

Australian government public engagement with religious diversity tends to fall into the following four distinct areas: multicultural policy, anti-discrimination legislation, education, and policing. Australian government responses to religious diversity are primarily subsumed as part of multicultural policy responses to ethnic and cultural diversity. The ubiquity of multicultural policies and plans highlights the entrenched nature of multiculturalism discourse in Australian politics. This focus on multiculturalism, however, has the consequence of less attention being given to religious diversity and multifaith awareness on Australian federal and state and territory governments’ websites.

Every Australian state and territory government (SaTG) has in place some form of multicultural action plan, policy, or strategy. Examples include: “Tasmania’s Multicultural Action Plan 2019–2022” (

Tasmanian Government 2019), the “Queensland Multicultural Recognition Act 2016” (

Queensland Government 2019), and the “Multicultural Action Plan for South Australia” (

Government of South Australia 2016). These documents incorporate elements of response to religious diversity to differing degrees. Some refer only to ethnic, cultural, or linguistic diversity, rather than religious diversity (i.e., referring only to “CALD (culturally and linguistically diverse) communities”), while others do refer to religious diversity specifically. The “Northern Territory Multicultural Participation Framework 2016–19” (

Northern Territory Government 2016, p. 6), for example, recognizes “religious diversity [as] reflected in the practices of Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism and Islam among others”. In contrast, WA’s “Charter of Multiculturalism 2004” (2004) never mentions religious diversity as a stand-alone concept. The Victorian State Government is notable in having a visible governmental body dedicated specifically to religious diversity, the Victorian Government Multifaith Advisory Group (

Victoria Multicultural Commission 2019).

All SaTGs offer community grant programs designed to facilitate multicultural or multifaith programs and events. Grants have been provided, for example, to support Diwali or Eid celebrations (

State Government of Victoria 2019a). Grant funding typically aims to support religious events and festivals oriented towards involving the greater community; there is a focus on interfaith and religious-nonreligious engagement, rather than what might be interpreted as self-containment or insularity on the part of individual religious communities. Victorian State Government grants tend to be more explicitly supportive of religious and interfaith initiatives than the grant programs of other states, and Victoria is unique in the provision of Security Infrastructure Funds for multicultural and multifaith groups to “upgrade and install security infrastructure” within their facilities (

State Government of Victoria 2019b).

Religious anti-discrimination legislation varies significantly between the states of Australia. There is currently no national legislation, although religious freedom legislation is under consideration. State and territory legislation differ in the degree of protection offered. Barring New South Wales and South Australia, all states and territories in Australia “have legislated to prohibit discrimination on the basis of what is described variously as religious ‘belief’, ‘conviction’, ‘activity’ and ‘affiliation’” (

Rees et al. 2018, p. 553). However, South Australia does “protect the attribute of ‘religious appearance or dress’, while New South Wales includes ‘ethno-religious origin’ within the definition of ‘race’” (

Rees et al. 2018, p. 553). Reflecting a general trend of more explicit response to religious diversity, Victoria has the most sophisticated legislation. This includes both the “Racial and Religious Tolerance Act” (

Victorian Parliament 2001) and the “Equal Opportunity Act” (

Victorian Parliament 2010).

SaTG education department websites’ discussion of religion and cultural/religious diversity differs considerably. The degree to which this content specifically addresses religious diversity is often low. Education Queensland’s website features the state’s “Inclusive Education” policy (2018); ACT’s education department promotes the “Safe and Supportive Schools” policy (2016); and the Tasmania Education Department’s website contains a section simply titled “Diversity” (

Tasmanian Government 2017). Most Australian states, except for South Australia and Victoria, still permit religious instruction by religious volunteers rather than teachers in secular schools. Developments in the national curriculum are moving toward a more inclusive approach to religious diversity, with the national Australian curriculum containing some limited content on diverse religions and worldviews. Victoria’s is the only state curriculum to include two dedicated sections on learning about diverse worldviews and religions in humanities and ethical capability (

Halafoff et al. 2019).

Most police departments have some form of framework or strategy policy in place for responding to diversity within the community, but it is rare for these documents to explicitly discuss religious diversity. For example, the NSW Police Force’s “Multicultural Policies and Services Plan 2017–2020” (

NSW Police Force 2017, p. 5) contains the statement that they “aspire to grow a culture of inclusion in which ethnicity, religion and language are valued”. Victoria was unique in establishing the Victoria Police Multi-Faith Council in 2005 (

Halafoff 2011).

The rationales provided on SaTGs websites for responding to religious diversity largely engage with four major themes as follows: respect, celebration of diversity, the importance of harmony, and (less commonly) explicit reference to the maintenance of social cohesion. These four themes suggest that government policy, as represented on SaTG websites, endorses forms of social cohesion and intercultural engagement that encourage the integration of multicultural communities into a wider ‘Australian culture’.

The narrative of “respect” incorporates notions of protection, inclusion, participation, and addressing of structural barriers faced by multicultural communities:

All students and families feel and are welcome, respected, included and safe at our state schools … We address the different barriers experienced by students and develop strategies and plans to support inclusive education for our diverse student population.

The very common narrative of “celebrating diversity” involves ideas of celebration and cultural diversity as a “strength” of, and benefit to, Australian communities. This is reflected in Victoria’s “Multicultural Policy Statement”:

The Victorian Government is determined to make sure that all Victorians can enjoy the social, cultural, and economic benefits of a dynamic and diverse society.

“Harmony” discourse includes notions of shared values, communal responsibility, and positive intergroup interactions:

All Tasmanians have an equal opportunity and responsibility to contribute to Tasmanian life, are treated with respect, dignity and without discrimination.

Both federal and state and territory Government websites also refer to the importance of social cohesion. The Federal Department of Home Affairs website, for example, states that “Australia’s approach to multicultural affairs is a unique model based on integration and social cohesion”. Queensland established the Queensland Social Cohesion Implementation Committee, “as a step towards enhancing social cohesion in our communities” (

Queensland Government 2016). The Northern Territory’s multicultural grants program provides funding for “projects or activities that promote … cohesion”, (

Northern Territory Government 2019) while the South Australian Multicultural Affairs (

Government of South Australia 2019) website states

Our vision is to achieve an open, inclusive, cohesive and equitable multicultural society, where cultural, linguistic and religious diversity is understood, valued and supported.

These references tend to incorporate elements from the three themes above, appearing alongside references to these other themes while using the language of “cohesion” to denote a sense of national unity. These references to social cohesion do little to articulate a clear approach to the negotiation of religious difference and diversity in Australia. As we have argued above, social cohesion can be invoked in conjunction with various, potentially divergent, responses to religious diversity. On the one hand, the language used on the websites promotes respectful intergroup contact through celebration and respect, the encouragement of various forms of participation in wider Australian society, and a stated desire to overcome barriers between people, and between people and services. However, on the other hand, these same themes can be understood as potentially reinforcing pre-existing forms of privilege in Australian society. Some of the language implies that multicultural and multifaith communities are valuable to Australia primarily for the economic or cultural contribution they make to an already-existing Australian culture. Furthermore, the repeated references to “all” Tasmanians, Victorians, students, etc., in the quotes above suggests that everyone holds a responsibility to create a cohesive society. This could be read as placing the onus on religiously diverse communities to adapt to preconceived notions of “Australian culture”. As

Thomas et al. (

2018, p. 272) argue,

There is a subtle but important difference between the view that all residents ought to endeavour to have more meaningful interactions with people from different backgrounds, and the view that the ‘Other’ ought to be doing more to integrate into the supposed host community.

The language on Australian government websites tends towards a respectful encouragement of community diversity and positive social interactions, which does not seek to impose sameness, reflecting the first half of Thomas et al.’s statement. However, this message is underpinned by a generally inconsistent and shallow level of engagement with religious diversity on these websites, and, arguably, a normative commitment to encouraging the palatable aspects of multicultural communities so that they can contribute to Australian culture more broadly. In this way, the various discourses used on these websites, from celebration and harmony, to social cohesion can be understood as “keeping up appearances”, expressing an aim of encouraging the engagement of religiously diverse individuals in Australian society, whilst maintaining demands that these individuals do so in ways that do not disrupt the nation’s ”cohesion”. The possible exception to this tension is in the use of “respect” discourse, which more firmly grounds religious diversity as an opportunity to pursue cosmopolitanism, deep equality, and reasonable pluralism. However, even “respect” can at times function as a means of managing fears about the disruptive effects of social change, where diversity is seen as a potential threat to cohesion. This can be seen in a 2018 statement about multiculturalism from the then Australian Prime Minister

Malcolm Turnbull (

2018). The statement emphasizes “mutual respect”, suggesting a strong approach to valuing diversity, at the same time as valorizing “our people” and “our values”, which suggests an approach that defends the status quo against the possibility of change.

The glue that holds us together is mutual respect—a deep recognition that each of us is entitled to the same respect, the same dignity, the same opportunities. And national security—a resolute determination to defend our nation, our people and our values—is the foundation on which our freedoms have been built and maintained. At a time of growing global tensions and rising uncertainty, Australia remains a steadfast example of a harmonious, egalitarian and enterprising nation, embracing its diversity.

Alongside the concept of social cohesion, there has been a recent take up of language associated with human rights, citizenship, and resilience. For example, the

Australian Government (

2019) is providing grants to “facilitate the participation, integration and social cohesion of both newly arrived migrants and culturally diverse communities in Australia”. The aims of these grants include goals to “build community resilience … amplifying the value of Australian citizenship … [and] promoting a greater understanding and acceptance of racial, religious and cultural diversity”. The move to consider human rights is reflected in the Victorian Charter of Human Rights (

Victorian Parliament 2006) and the

ACT Government (

2017) Human Rights Act, both of which have sections about the individual’s right to declare and practice religion. Further research is required on the significance of this human rights discourse.

Australian state and territory government policy responses could have more contextualized and nuanced responses to religious diversity. We would make two points about this. First, many of the practices that facilitate respect and inclusive pluralism operate at the everyday level and cannot be easily articulated in these sorts of policies (

Beaman 2017a). Local government activities are often aimed at supporting respect and inclusion but are not analyzed here. Second, to the extent that policies can facilitate or remove impediments to practices of respect and inclusive pluralism, there is considerable work to do. There is a relative absence of sophisticated and contextualized policy responses that facilitate the negotiation of differences and the tensions that diversity can create. This absence can reinforce the privileges of previously dominant religious voices and communities. More empirical work is required to examine whether this is actually the case. As stated above, Victoria appears to have a more sophisticated engagement with cultural innovation and social change as opportunities to support new forms of respectful diversity, as is evidenced by its more explicit legislation that addresses these issues.

5. Discussion

Australia’s religious diversity is even more complex than it first appears. As

Bouma (

2011, p. 15) argues: “Diversity is the new normal. The rise of Pentecostal spirituality along with Muslim communities, Buddhists and Hindus has required making room, geographical, social and physical for mosques, temples, and other spiritual places. In Australia, the new Christian normal is Catholic”. We would add to this that the growth in numbers of those who are “not religious” is also significantly changing how religious diversity is experienced and negotiated. Australian governmental responses to this significantly increased religious diversity are piecemeal and vary greatly between states, and within states. The State of Victoria clearly has a substantially more sophisticated response to religious diversity than other Australian states. It, therefore, serves as a useful case study of strategies responding to religious diversity (

Bouma and Halafoff 2017a).

We demonstrate that Australian government policy responses to religious diversity can be variously designed to generate sameness, authority, interdependence, democratic inclusion, cosmopolitanism, and equality. Sameness can generate shared respect, as long as sameness does not involve denial of difference. This involves the awareness of, acceptance of, and mutual respect toward differences, i.e., we treat all others the same—with respect, dignity and openness to the gift of the differences embodied in their otherness.

Beaman (

2017a, p. 34) argues that equality is: “an achievement of day-to-day interaction, and is traceable through agonistic respect, recognition of similarity, and a concomitant acceptance of difference, creation of community, and neighbourliness”. Similarly, authority can be a source of respect and equality when it prevents extremes of religious vilification and discrimination (

Ezzy 2013). However, it can also be problematic if it is used to enforce “sameness’ that erases difference. From our perspective it is not useful to argue that any one of these strategies provides a universally applicable response to religious diversity.

Schaeffer (

2014, p. 137) reaches a similar conclusion about ethnic diversity and social cohesion based on German data: “I have argued that the relation between ethnic diversity and social cohesion depends on the workings of mediating mechanisms and moderating conditions”. The important question to ask of particular strategies designed to facilitate “social cohesion” is under what circumstances they operate to achieve particular outcomes?

The European “diversity paradigm” (

Griera 2018) is partially in evidence in Australia. Griera highlights the potential political entanglements of this paradigm. Nevertheless, we would argue that the way forward is to be explicit about the normative elements in any such conceptions, rather than seeking to avoid such entanglements. Furthermore, we would point out that empirical description is often bound up with normative value commitments in the concepts utilized to understand responses to religious diversity. “Social cohesion”, “diversity”, “cosmopolitanism” and ”deep equality”, for example, are both empirical descriptions of social patterns, and articulations of particular normative and policy goals. These normative and value commitments need to be explicit.

Does the “new” religious diversity pose a threat to social cohesion, or an opportunity?

Veit Bader (

2007, p. 179) points out that “at least for a short while, it seemed as if increased religious diversity—and even new forms of institutionalisation of religious pluralism- could be seen not only in a dramatized and negative way, i.e., as a threat to peace, security, stability, cohesion, toleration and democracy, but also as an opportunity and a promise” (

Bader 2007, p. 18).

When diversity is conceptualized as a threat, policies designed to protect social cohesion tend to serve to protect privilege and undermine democratic pluralism. When diversity is conceptualized as an opportunity, however, it serves to open out a range of policy responses that are more inclusive, cosmopolitan, and respectful (see

Vasta 2013). The analysis above of policy statements on Australian government websites suggests there is still considerable work to do to ensure policy discourse appropriately encourages practices of social inclusion.

Bader (

2007, p. 247) argues that “the fear of disintegrative effects is very often based on uncritical assumptions regarding social cohesion, which are incompatible with functionally and culturally differentiated societies”. Part of the challenge is identifying these alternative forms of social cohesion. As

Bouma (

2012, p. 148) puts it “the successful integration of religious groups new to a society and the development of a form of social cohesion based on something other than similarity requires a great deal of effort”.

In the opening paragraphs we quoted the former Australian Federal Minister for Immigration and Citizenship who discussed policies to “strengthen social cohesion” and “seek the effective integration of migrants into Australian life” (

Andrews 2007, p. 46). “Social cohesion” and “integration” are complex terms. This complexity needs to be made more explicit, and particularly the way these concepts overlay empirical realities with value-based commitments.

Thus when governments develop ‘evidence based’ integration policies they normally do so in a rather confused state where the object is to make minorities become ‘just like us’—namely, rational human beings driven primarily by economic factors, subscribing to values developed with a predominantly Christian tradition, a dominant language and a common loyalty to a defined ‘nation’, which over-rides other loyalties and former homelands.

The pursuit of social cohesion through coercive policies that seek value consensus and create social exclusion can have counterproductive consequences, including marginalization, increased violence, and poor health. In turn, these contribute to the processes that increase the chances of terrorist related violence. In contrast, we argue for explicitly valuing the opportunities that are created by greater religious diversity such as new forms of democratic engagement, pluralistic respectful relationships, and equality. Engaging with diversity in this way is not necessarily an easy experience. Agonistic engagement with the “other” who threatens and unsettles us is a central part of this process, operating alongside other strategies that protect human rights and encourage respectful engagement with religious diversity (

Connolly 2005;

Ezzy 2013;

Halafoff 2013;

Beaman 2017a).