Deconversion Processes in Adolescence—The Role of Parental and Peer Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Adolescent Deconversion Scale

2.2.2. Parental Bonding Instrument

2.2.3. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

2.3. Study Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ainsworth, Mary D. Salter, Mary C. Blehar, Everett Waters, and Sally N. Wall. 1978. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden, Gay C., and Mark T. Greenberg. 1987. The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 16: 427–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, Jeffrey J. 2000. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist 55: 469–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1979. Self-referent mechanisms in social learning theory. American Psychologist 34: 439–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, John D. 1994. Versions of Deconversion: Autobiography and the Loss of Faith. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, John. 1991. Attachment and Loss. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. New York: Viking Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, Chris J., David C. Dollahite, and Loren D. Marks. 2006. The Family as a Context for Religious and Spiritual Development in Children and Youth. The Handbook of Spiritual Development in Childhood and Adolescence. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 297–309. [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla, Maria, Avi Assor, Claudia Manzi, and Camillo Regalia. 2015. Autonomous versus controlled religiosity: Family and group antecedents. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 25: 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 2000. Ecological systems theory. In Encyclopedia of Psychology. Edited by Alan E. Kazdin. Washington, DC and New York: American Psychological Association Oxford University Press, vol. 3, pp. 129–33. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B. Bradford. 1990. Peer groups and peer cultures. In At the Threshold: The Developing Adolescent. Edited by S. S. Feldman and G. R. Elliott. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 171–96. [Google Scholar]

- Buchbinder, Jacob. T., Yoram Bilu, and Ely Witztum. 1997. Ethnic background and antecedent of religious conversion among Israeli Jewish outpatients. Psychological Reports 81: 1187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, Maria, Gonzalo Bacigalupe, and Patricia Padilla. 2017. The role of social support in adolescents: Are you helping me or stressing me out? International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 22: 123–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmond, Scott A., Kristopher H. Morgan, and George Kikuchi. 2010. How (and why) does religiosity change from adolescence to young adulthood? Sociological Perspectives 53: 247–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrosiers, Alethea, Brien S. Kelley, and Lisa Miller. 2011. Parent and peer relationships and relational spirituality in adolescents and young adults. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Keren, Myron D. Friesen, and Jeffrey D. Gage. 2019. The psychological salience of religiosity and spirituality among Christian young people in New Zealand: A mixed-methods study. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 11: 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubow, Erik F., Kenneth R. Lovko, Jr., and Donald F. Kausch. 1990. Demographic differences in adolescents’ health concerns and perceptions of helping agents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 19: 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecklund, Elaine H., and Jerry Z. Park. 2007. Religious Diversity and Community Volunteerism Among Asian Americans. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 46: 233–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, Joseph A. 1992. Adolescent religious development and commitment: A structural equation model of the role of family, peer group, and educational influences. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 31: 131–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, Erik H. 1963. Childhood and Society, 2nd ed. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Exline, Julie J., Steffany J. Homolka, and Joshua B. Grubbs. 2013. Negative Views of Parents and Struggles with God: An Exploration of Two Mediators. Journal of Psychology & Theology 41: 200–12. [Google Scholar]

- Flor, Douglas L., and Nancy F. Knapp. 2001. Transmission and transaction: Predicting adolescents’ internalization of parental religious values. Journal of Family Psychology 15: 627–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, James W. 1981. Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Developement and the Quest for Meaning. San Francisco: Harper & Row Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- George, Darren, and Paul Mallery. 2010. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update, 10a ed. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Michael A., and Justin W. Dyer. 2020. From parent to child: Family factors that influence faith transmission. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12: 178–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrese, Anna, and Ruggero Ruggieri. 2012. Peer attachment: A meta-analytic review of gender and age differences and associations with parent attachment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 41: 650–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, Pehr, and Berit Hagekull. 2003. Longitudinal Predictions of Religious Change in Adolescence: Contributions from the Interaction of Attachment and Relationship Status. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 20: 793–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, Pehr, and Lee A. Kirkpatrick. 2013. Religion, Spirituality, and Attachment. In APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality (Vol 1): Context, Theory, and Research. Edited by Kenneth I. Pargament, Julie J. Exline and J. W. Jones. APA Handbooks in Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 139–55. [Google Scholar]

- Granqvist, Pehr, Tord Ivarsson, Anders G. Broberg, and Berit Hagekull. 2007. Examining Relations among Attachment, Religiosity, and New Age Spirituality Using the Adult Attachment Interview. Developmental Psychology 43: 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, Yaakov, Mario Mikulincer, Pehr Granqvist, and Phillip R. Shaver. 2018. Apostasy and conversion: Attachment orientations and individual differences in the process of religious change. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 28: 260–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, Kathleen M., Dimity A. Crisp, Lisa Barney, and Russell Reid. 2011. Seeking help for depression from family and friends: A qualitative analysis of perceived advantages and disadvantages. BMC Psychiatry 11: 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, Aldona, Radosław Marzęcki, and Łukasz Stach. 2015. Pokolenie’89. Aksjologia i aktywność młodych Polaków. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Pedagogicznego. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., William Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education International. [Google Scholar]

- Halama, Peter, Marta Gašparíková, and Matej Sabo. 2013. Relationship between attachment styles and dimensions of the religious conversion process. Studia Psychologica 55: 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, Sam A., Jennifer A. White, Zhiyong Zhang, and Joshua Ruchty. 2011. Parenting and the socialization of religiousness and spirituality. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 217–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Judith. 1995. Where is the child’s environment? A group socialization theory of development. Psychological Review 102: 458–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, Lisl M., and Eleonora Gullone. 2006. The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review 26: 695–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoge, Dean R., Gregory H. Petrillo, and Ella I. Smith. 1982. Transmission of religious and social values from parents to teenage children. Journal of Marriage and the Family 44: 569–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasmohammadi, Mahdi, Sara Ghazizadeh Ehsaei, Wouter Vanderplasschen, Fariborz Dortaj, Kioumars Farahbakhsh, Hossein Keshavarz Afshar, Zahra Jahanbakhshi, Farshad Mohsenzadeh, Sidek Mohd Noah, Tajularipin Sulaiman, and et al. 2020. The Impact of Addictive Behaviors on Adolescents Psychological Well-Being: The Mediating Effect of Perceived Peer Support. Journal of Genetic Psychology 181: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sangwon, and Gissele B. Esquivel. 2011. Adolescent spirituality and resilience: Theory, research, and educational practices. Psychology in the Schools 48: 755–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, Lee A., and Philip R. Shaver. 1990. Attachment theory and religion: Childhood attachments, religious beliefs and conversion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 29: 315–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, Reed, and Maryse H. Richards. 1991. Daily companionship in late childhood and early adolescence: changing developmental contexts. Child Development 62: 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, Kathleen C., Kaye Cook, Chris Boyatzis, Cynthia N. Kimball, and Kelly S. Flanagan. 2013. Parent-child dynamics and emerging adult religiosity: Attachment, parental beliefs, and faith support. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 5: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, Gregory S., and Jungmeen Kim-Spoon. 2014. What drives apostates and converters? The social and familial antecedents of religious change among adolescents. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 6: 284–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łysiak, Małgorzata, and Piotr Oleś. 2017. Temporal dialogical activity and identity formation during adolescence. International Journal for Dialogical Science 1: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mandes, Sławomir, and Maria Rogaczewska. 2013. “I don’t reject the Catholic Church—the Catholic Church rejects me”: How Twenty- and Thirty-somethings in Poland Re-evaluate their Religion. Journal of Contemporary Religion 28: 259–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariański, Janusz. 2011. Tendencje rozwojowe w polskim katolicyzmie—Diagnoza i prognoza. Teologia Praktyczna 12: 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McDonald, Angie, Richard Beck, Steve Allison, and Larry Norswortby. 2005. Attachment to God and Parents: Testing the Correspondence vs. Compensation Hypotheses. Journal of Psychology & Christianity 24: 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, Scott M. 1996. An Interactive Model of Religiosity Inheritance: The Importance of Family Context. American Sociological Review 61: 858–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, Andreea. 2019. Exiters of religious fundamentalism: Reconstruction of social support and relationships related to well-being. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 22: 543–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowosielski, Mirosław, and Rafał P. Bartczuk. 2017. Analiza Strukturalna Procesów Dekonwersji w Okresie Dojrzewania–Konstrukcja Skali Dekonwersji Adolescentów. Roczniki Psychologiczne/Annals of Psychology 20: 143–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offer, Daniel, Kenneth I. Howard, Kimberly A. Schonert, and Erik J.D. Ostrov. 1991. To Whom Do Adolescents Turn for Help? Differences between Disturbed and Nondisturbed Adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 30: 623–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okagaki, Lynn, and Claudia Bevis. 1999. Transmission of religious values: Relations between parents’ and daughters’ beliefs. The Journal of Genetic Psychology 160: 303–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloutzian, Raymond F., Sebastian Murken, Heinz Streib, and Sussan Röβler-Namini. 2013. Conversion, Deconversion, and Transformation: A Multilevel Interdisciplinary View. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 399–421. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L., and Jeanne M. Slattery. 2013. Religion, Spirituality, and Mental Health. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Edited by Raymond F. Paloutzian and Crystal L. Park. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 540–59. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Gordon, Hilary Tupling, and L.B. Brown. 1979. A Parental Bonding Instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology 52: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Lisa D., Jeremy E. Uecker, and Melinda Lundquist Denton. 2019. Religion and Adolescent Outcomes: How and under What Conditions Religion Matters. Annual Review of Sociology 45: 201–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, Richard J. 2009. Trajectories of religious participation from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48: 552–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Christian, and Melina Lundquist Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilman, Sarah K., Tricia K. Neppl, Brent M. Donnellan, Thomas J. Schofield, and Rand D. Conger. 2013. Incorporating religiosity into a developmental model of positive family functioning across generations. Developmental Psychology 49: 762–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroczyńska, Maria. 2020. Młodzież w poszukiwaniu sacrum. Rozważania socjologiczne. Przegląd Religioznawczy 2: 113–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, Laurence, and Amanda S. Morris. 2001. Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology 52: 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streib, Heinz. 2020. Leaving Religion: Deconversion. Current Opinion in Psychology 40: 139–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streib, Heinz, and Barbara Keller. 2004. The Variety of Deconversion Experiences: Contours of a Concept in Respect to Empirical Research. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 26: 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, Chana. 1989. The Transformed Self. The Psychology of Religious Conversion. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vrublevskaya, Polina, Marcus Moberg, and Sławomir Sztajer. 2019. The role of grandmothers in the religious socialization of young adults in post-socialist Russia and Poland. Religion 49: 201–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, Ross B. 2004. The role of parental and peer attachment in the psychological health and self-esteem of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 33: 479–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata. 2009. Tradition or Charisma. Religiosity in Poland. In What the World Believes: Analysis and Commentary on the Religion Monitor 2008. Edited by Bertelsmann Stiftung. Gütersloh: Verlag Bertelsmann Stiftung, pp. 201–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycka, Beata. 2018. Parental Attachment Styles and Religious and Spiritual Struggle: A Mediating Effect of God Image. Journal of Family Issues, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata, and Elżbieta Rydz. 2014. Explaining the Relationship between Post-Critical Beliefs and Sense of Coherence in Polish Young, Middle, and Late Adults. Journal of Religion and Health 53: 834–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimet, Gregory D., Nancy W. Dahlem, Sara G. Zimet, and Gordon K. Farley. 1988. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment 52: 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WFC | — | |||||||||||

| 2 | AF | 0.64 *** | — | ||||||||||

| 3 | MC | 0.62 *** | 0.77 *** | — | |||||||||

| 4 | ETE | 0.54 *** | 0.73 *** | 0.65 *** | — | ||||||||

| 5 | DB | 0.82 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.49 *** | — | |||||||

| 6 | Care M | −0.10 | −0.21 *** | −0.19 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.06 | — | ||||||

| 7 | Care F | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.12 | 0.01 | 0.50 *** | — | |||||

| 8 | Rel M | −0.16 * | −0.19 ** | −0.17 * | −0.12 | −0.06 | 0.09 | 0.12 | — | ||||

| 9 | Rel F | −0.15 * | −0.18 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.15 * | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.26 *** | 0.58 *** | — | |||

| 10 | Friends | −0.08 | −0.19 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.26 *** | −0.03 | 0.20 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.03 | 0.02 | — | ||

| 11 | Family | −0.03 | −0.22 ** | −0.14 * | −0.22 ** | 0.04 | 0.60 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.56 *** | — | |

| 12 | Others | −0.01 | −0.12 | −0.12 | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.16 * | 0.08 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.69 *** | 0.48 *** | — |

| M | 1.35 | 0.67 | 0.89 | 0.67 | 1.35 | 2.32 | 2.09 | 3.71 | 3.40 | 5.58 | 5.50 | 5.75 | |

| SD | 0.98 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.78 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 1.02 | 1.16 | 1.39 | 1.26 | 1.40 | |

| Αlpha | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.91 | |||

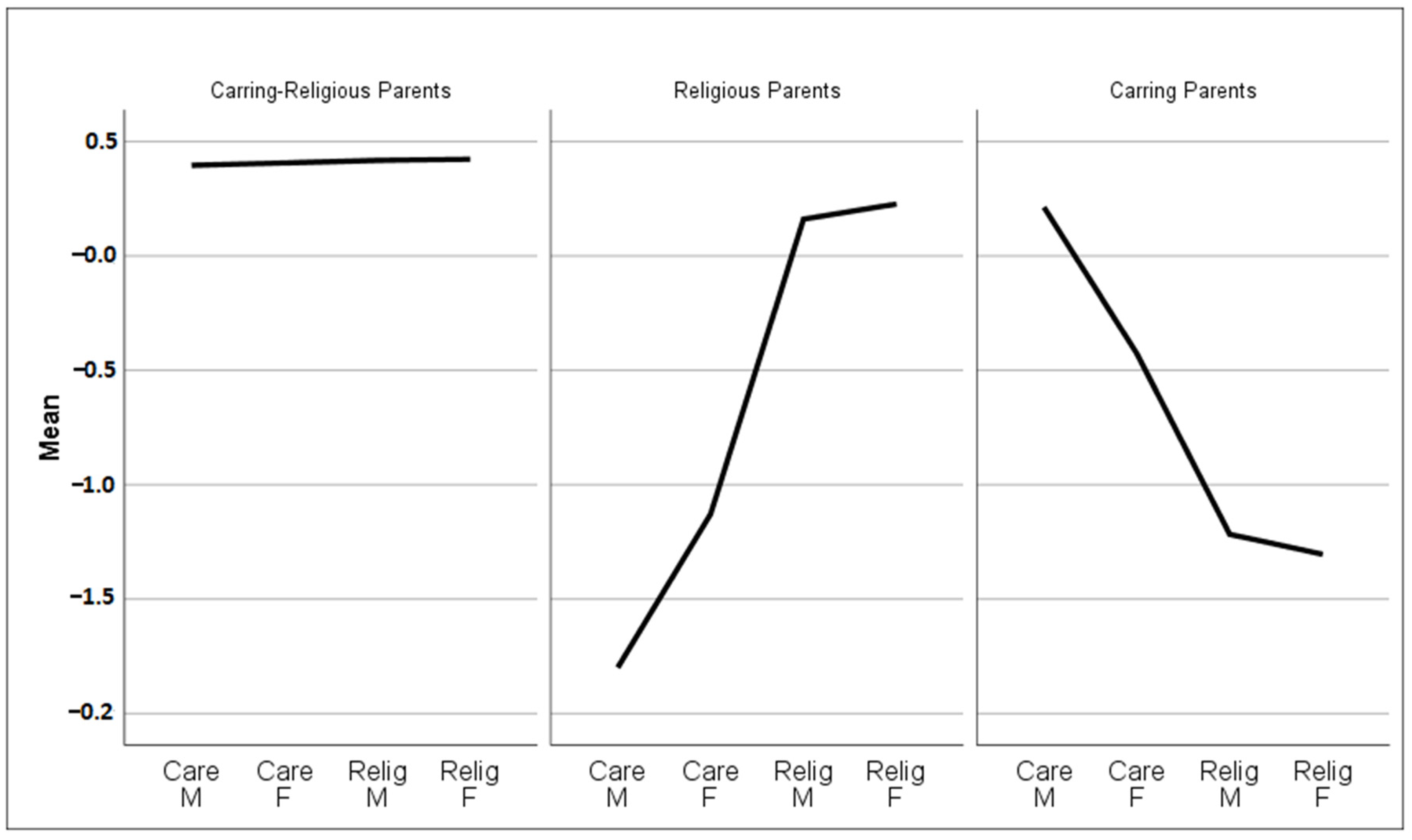

| Deconversion | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | ANOVA | Scheffe Test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caring-Religious Parents | Religious Parents | Caring Parents | |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F(2, 220) | p | 1:2 | 2:3 | 1:3 | |

| WFC | 1.27 | 0.90 | 1.49 | 1.04 | 1.64 | 1.17 | 2.70 | 0.070 | — | — | — |

| AF | 0.55 | 0.74 | 0.92 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 4.92 | 0.008 | 0.073 | — | 0.037 |

| MC | 0.76 | 0.76 | 1.13 | 0.90 | 1.15 | 1.12 | 4.95 | 0.008 | 0.090 | — | 0.030 |

| ETE | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 2.38 | 0.095 | — | — | — |

| DB | 1.30 | 0.95 | 1.49 | 1.07 | 1.49 | 1.11 | 0.94 | 0.392 | — | — | — |

| D | 0.89 | 0.66 | 1.17 | 0.82 | 1.21 | 0.93 | 4.09 | 0.018 | — | — | 0.047 |

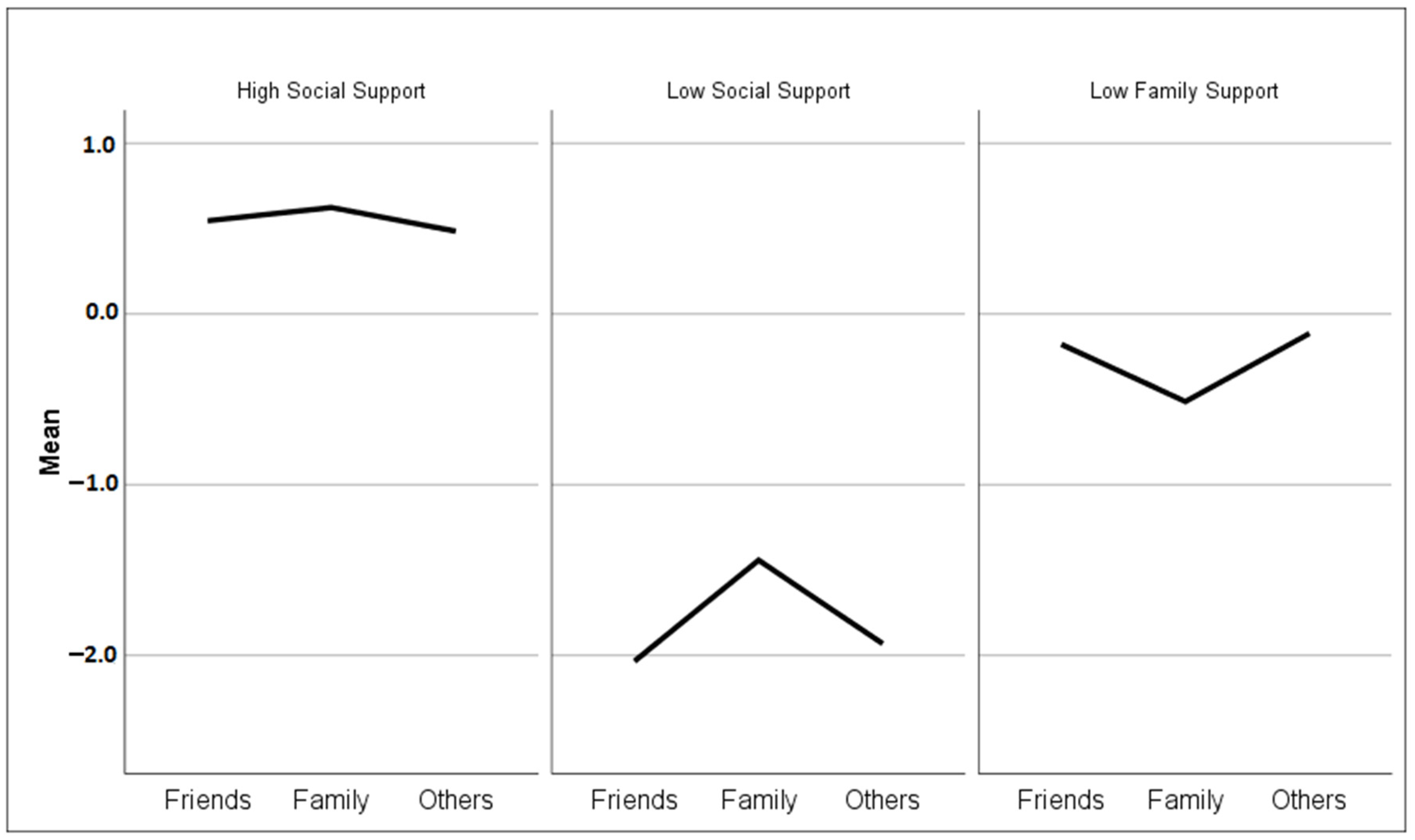

| Deconversion | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | ANOVA | Scheffe Test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Social Support | Low Social Support | Moderate Social Support | |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F(2, 220) | p | 1:2 | 2:3 | 1:3 | |

| WFC | 1.28 | 0.99 | 1.39 | 1.09 | 1.38 | 0.94 | 0.30 | 0.741 | — | — | — |

| AF | 0.53 | 0.75 | 1.14 | 0.91 | 0.66 | 0.90 | 5.83 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.042 | — |

| MC | 0.77 | 0.81 | 1.33 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 4.84 | 0.009 | 0.009 | 0.036 | — |

| ETE | 0.51 | 0.68 | 1.07 | 0.93 | 0.74 | 0.81 | 6.58 | 0.002 | 0.003 | — | — |

| DB | 1.32 | 1.01 | 1.27 | 1.07 | 1.35 | 0.96 | 0.06 | 0.941 | — | — | — |

| D | 0.88 | 0.69 | 1.24 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.76 | 2.70 | 0.069 | — | — | — |

| Model/Variables | B | Beta | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Constant | 0.98 | 19.19 | 0.001 | |

| Care M | −0.15 | −0.19 | −2.47 | 0.014 | |

| Care F | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.750 | |

| Model 2 | Constant | 0.99 | 19.58 | 0.001 | |

| Care M | −0.17 | −0.22 | −2.79 | 0.006 | |

| Care F | 0.06 | 0.09 | 1.04 | 0.297 | |

| Religiousness M | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.82 | 0.415 | |

| Religiousness F | −0.11 | −0.14 | −1.62 | 0.107 | |

| Model 3 | Constant | 0.99 | 19.71 | 0.001 | |

| Care M | −0.17 | −0.23 | −2.58 | 0.011 | |

| Care F | 0.09 | 0.12 | 1.45 | 0.150 | |

| Religiosity M | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.86 | 0.392 | |

| Religiosity F | −0.12 | −0.15 | −1.71 | 0.090 | |

| Friends’ Support | −0.20 | −0.27 | −2.66 | 0.008 | |

| Family’s Support | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.752 | |

| Others’ Support | 0.12 | 0.17 | 1.71 | 0.088 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Łysiak, M.; Zarzycka, B.; Puchalska-Wasyl, M. Deconversion Processes in Adolescence—The Role of Parental and Peer Factors. Religions 2020, 11, 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120664

Łysiak M, Zarzycka B, Puchalska-Wasyl M. Deconversion Processes in Adolescence—The Role of Parental and Peer Factors. Religions. 2020; 11(12):664. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120664

Chicago/Turabian StyleŁysiak, Małgorzata, Beata Zarzycka, and Małgorzata Puchalska-Wasyl. 2020. "Deconversion Processes in Adolescence—The Role of Parental and Peer Factors" Religions 11, no. 12: 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120664

APA StyleŁysiak, M., Zarzycka, B., & Puchalska-Wasyl, M. (2020). Deconversion Processes in Adolescence—The Role of Parental and Peer Factors. Religions, 11(12), 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120664