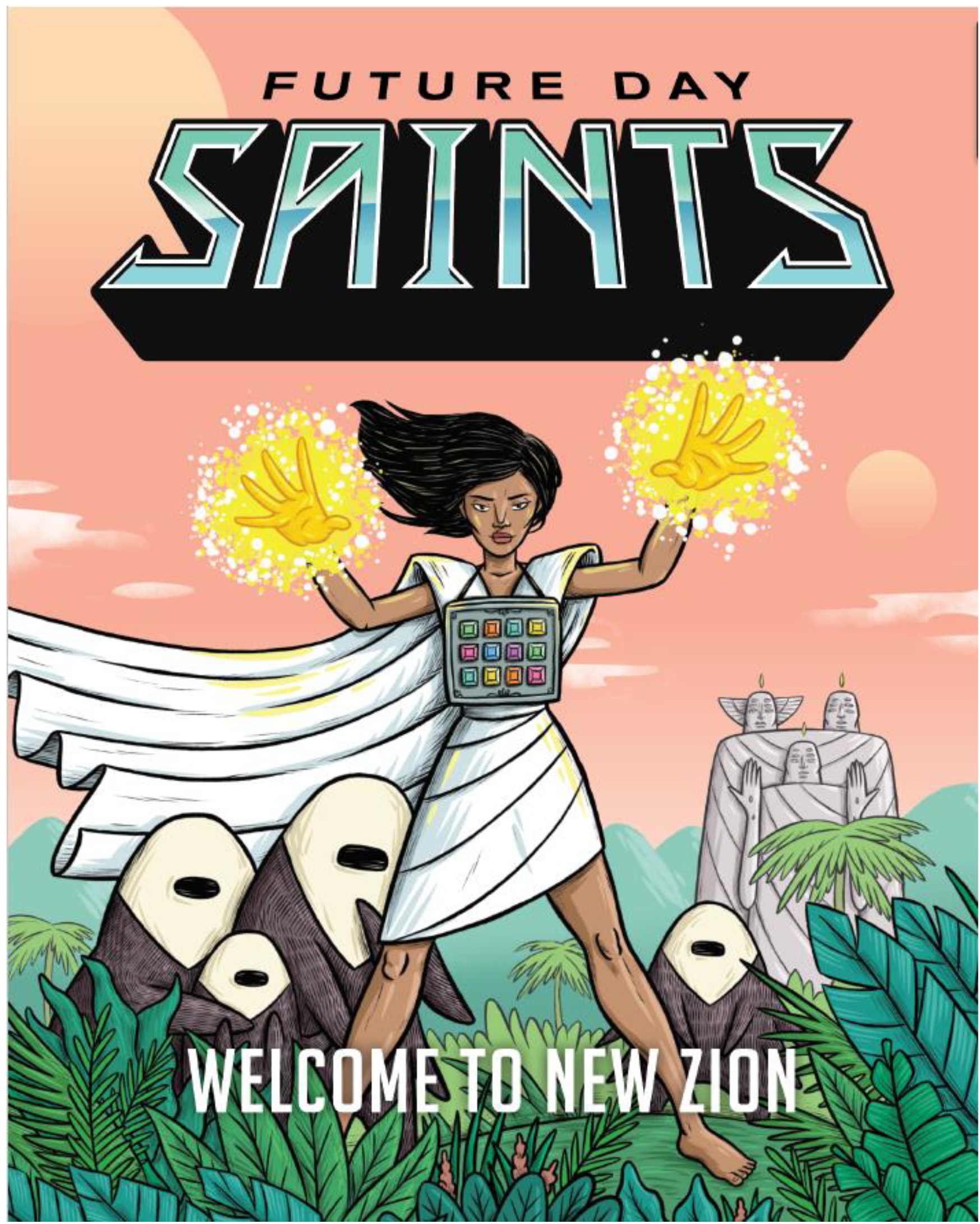

The volume is hardcover, and its dimensions are a standard picture-book nine and a half inches by eleven. Its cover displays a comic-book-style drawing of a brown-skinned woman in white robes. Her hands are outstretched towards the viewer, and they ripple with white and yellow energy. She is standing in the middle of an Edenic-looking copse of ferns and palm trees, and just slightly behind her, there are what looks like alien hybrids of a hedgehog and a fur-covered penguin. Except for a single black eye in the middle of their foreheads, these creatures are otherwise faceless ciphers. Behind her is a strange stone temple, carved in the shape of either three robed, multiple-eyed figures, or possibly of a single figure with three heads. Behind that grey spire is a skyline of tropical mountains, set against a peach-colored alien sky; this sky is made complete by a single large planet or moon looming in the background (See

Figure 1). Opening the book up, we see that the action in this book is set on a planet that was visited three thousand years ago by an alien messiah; this messiah had died and been resurrected on some other planet, only to then make an appearance on this world as well. That alien messiah prophesized the coming of immigrants from other solar systems. In the following millennia, different waves of alien refugees from numerous other star systems arrived on this planet. All of the worlds these refugees heralded from were planets that had been visited by this messiah at roughly the same time three millennia ago. On each planet where the messiah appeared, he took the form of whatever was the sentient lifeforms he preached to. The one exception is a planet named “Earth”. This planet also had contributed refugees to this strange settler world; on Earth, though, apparently, the messiah did not visit the planet in passing, but lived, died, and was resurrected there. After this short history lesson, the rest of the book is a mix of comic-book style illustrations with word balloons, and on the other large illustrations accompanied by long passages of texts. These comic pages and narratives tell the story of a team of unlikely looking superheroes who defend all these settlers on this alien world. In addition to the woman on the cover (her name is Liahona, and she holds “the Powers Of The Priest”), there is: a living skeleton with seer-stones for eyes; a scythe-wielding six-eyed blue-skinned warrior who wears a prairie dress; and a living stone capstone (a “sunstone”) who, when not serving as the team’s medic, plays in a ska band with his husband. There is also a white man in a grey business suit, who goes by the name “The Good Bishop.” They battle a team of evil antagonists called “The Curses”, whose members include: Lucifer (in the guise of “Morning Star”); the biblical “Mister Cain”; the “Bad Bishop” (who is identical in appearance to the good bishop); and an animated, sentient cup of coffee who goes by the name “Hot Drinks”. Parenthetically, the reason that all these aliens come to this planet is so that they can be close to a world called “Paradise”, which is also the “home of the Celestial Parents”. Both Paradise and New Eden, the name of the planet that the events of this book are set on, orbit a star named Kolob. The title of this book is

Future Day Saints: Welcome to New Zion (

Page 2020), and it is at once a love letter to, and a critique of, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, otherwise known as the Mormons Church.

1The author of this book has done other forms of “serial art” before, including a series of trading cards called “Garbage Pail Saints”, (a Mormon-themed parody of the comedic Garbage Pail Kids card series of the nineteen eighties) as well as a series of Mormon votive candles (votive candles are not a usual part of devotions for Latter-day Saints). This, though, is his first offering that could be classified as “Mormon Science Fiction”. However, it is certainly not the only offering in this genre.

Mormonism—most commonly represented by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—is the “restored Gospel” tradition started in the 19th century United States by Joseph Smith, a man who is generally considered to be a “prophet, seer, and revelator” by the faithful. The term “Restored Gospel” is used because much of Mormon practice and doctrine, such as temple worship and the priesthood system, are held to be a return to original forms of religiosity that go back as far as the Garden of Eden, but which were lost in the three centuries immediately following the death of Jesus, in a period that is referred to as the “Great Apostasy”. One of the distinctives of Mormonism (and there are numerous distinctives, as evidenced by the fact that Mormons sometimes describe themselves as a “peculiar people”) is that there is a robust tradition of Mormon science fiction. The contributions range from works almost universally treated as classics in the genre (such as Orson Scott Card’s

Ender’s Game) to genre television shows (the first iteration of

Battlestar Galactica). It should be stressed that the breadth of Mormon speculative fiction stands also stands out in the gross, qualitative, demographic sense. An online “Bibliography of Mormon Speculative Fiction” lists over five hundred authors who are affiliated in some way with the Church, and this is a list that has not been updated since 2014. This is not to mention the numerous books, penned by non-Mormons, that feature Mormon characters, such as Charles Stross’s

Accelerando (

Stross 2005), which includes references to the fictional “Reformed Tiplerite Church of the Latter-day Saints”, and works by James S. A. Comey (the pseudonym for the co-authors of

The Expanse book series), which features as a plot device a Mormon generational ship, the L.D.S.S.

Nauvoo, that is intended to travel to Alpha-Centauri.

1. Anthropologies of (Absent) Futures and (Religious) Space?

To be clear, we are not speaking of space in the manner customarily discussed—as the social production of topographies and landscapes here on the earth (see, e.g.,

de Certeau 1984, pp. 91–130;

Low and Lawrence-Zúñiga 2003). Instead, we are speaking about space in the “final frontier” (

Swanson 2020a,

2020b; see also

Farman 2020, pp. 151–52) sense of the term: the interplanetary and interstellar space of settler-society 20th and 21st century imagination, a place capable of being explored and peopled (though not necessarily peopled by

homo sapiens).

Now, it is puerile to associate speculative fiction unproblematically with only “space” or “the future”. Speculative fiction explores numerous imaginable scenarios, asking not what

will happen, but what

could happen given a set of hypothetical conditions; further, the scenarios selected are not necessarily based on their likelihood of occurrence, but on how interesting the underlying premises are conceptually. Because of this fact, it is better to understand speculative fiction as a form of ideational experiment or critique. (

Shaviro 2016). Additionally, thanks to this genre’s work as a conceptual laboratory or as a mode of critical investigation, “social theory and speculative fiction are two sides of the same coin”, as

Matthew Wolf-Meyer (

2019) has observed. That said, the fact that some science fiction does set itself in a future that has expanded both beyond Earth and the present moment is a point worthy of anthropological interest.

The reason why anthropology might wish to attend to the Mormon speculative imagination is that the discipline has observed that the future has become “difficult to think”—that is, the future has become something that taxes the collective cultural imaginary. As noted by

Jane Guyer (

2007), due to economic and political shifts associated with neoliberalism, the near to middle-term future has become difficult to conceive of. Guyer’s observation was intended to be an ethnographic one, but it seems safe to say that it can also be applied to anthropology itself. This can be seen in

Valentine et al.’s (

2009, p. 11) observation that “‘the future is being conspicuously overlooked as a research project” in the discipline, “despite increasing social investment in future-focused things and practices”. Some of this erasure of the future may be hard-wired into the field; it is easy to argue that participant-observation is inherently presentist by its very nature (

Irvine 2020). Of course, this argument can only go so far: scholars have found ways to ethnographically investigate outer-space-facing human practices that are metonymically linked to the future. (

Battaglia et al. 2015;

Messeri 2016;

Olson 2018). However, despite these contributions, it appears that we still need to develop ways of framing outer space as an ethnographic and anthropological problem.

This is where the before-mentioned kinship between social theory and science fiction becomes relevant. We can turn to speculative fiction qua “outsider social theory” (

Wolf-Meyer 2019) in order to be able to think what seems to have been inconceivable for the most part in the established, professional anthropological community. However, turning to this body of literature opens up new challenges and possibilities, for there is not a single speculative fiction. Instead, there is a wealth of different speculative fictions informed by the lives and the self-understandings of authors from different communities, including, as we have seen, lives and understandings of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

2The idea of religiously inflected imaginations of space is something that, for the most part, has not been addressed by anthropology, putting aside a single exception. (I am thinking here of the work of Deana Weibel, who has addressed both confessional religion in space, as well as “magic” in the form of astronaut superstition (

Weibel 2007,

2015,

2017,

2019a,

2019b,

2019c,

2020)). This lack of attention means that anthropology has not yet come to grips with how to handle religious speculative thought that operates in a register that yearns to escape earth’s orbit. What to do with such speculation—and especially what to do with the aspect of it that might read as critique? Such work should not be automatically waved away because of its religious provenance; such an origin does not mean that on first principle, it cannot be engaged in critical investigation (

Asad et al. 2013). Additionally, potentially turning to Mormon science fiction need not be an exercise in post-secular anthropology (c.f.

Fountain 2013) or even an explicitly theological endeavor (

Menses et al. 2014). Instead, given the antinomies between exclusively confessional religious thought and anthropology (

Engelke 2014), it is better to think of this as a dialogic project, an attempt to have a transformative encounter with a different mode of being in the world, instead of merely dissecting it, and to do so without necessarily abandoning core intellectual principles (see, e.g.,

Tomlinson 2020).

There is another reason, though, why Mormon speculative fiction cannot simply be “ported” into the academic mechanism of anthropology to become “ethnographic theory” (

Da Col and Graeber 2011). That is because there are elements of Mormon thought that may not be easily digested by anthropology. Views on gender, sexuality, and race are not monological in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; furthermore, Church doctrines on these issues have been reconfigured in the past, and there is every sign that doctrines regarding sexuality and gender are capable of being reconfigured yet again in the future (

Petrey 2020). Further, while many progressive Mormons find themselves leaving the Church (

Brooks 2018), there is also a respectable number who remain within the Church, even if they are nowhere close to forming a plurality, let alone a majority. Still, while there is some evidence that generationally (

Riess 2019), Mormon views on this issue may be shifting, on the whole, opinions on this subject among other elements of the Church would not be in line with the anthropological consensus. Additionally, this is putting aside the fact that even though polygamy (at least as a practice occurring among the living) has been rejected as a Church doctrine for over a hundred years (

Van Wagoner 2002), its legacy still makes discussions of kinship and gender fraught (

Pearson 2016).

3Given this, it seems best to not simply understand whatever conceptual work is being done in Mormon science fiction (for it is undoubtedly sure that the wealth of literature discussed above cannot be reduced to a single vantage point), but to examine the underlying conditions of possibility as well, so that anthropology can approach this in a way that opens itself up for the necessary critique (

Bialecki 2018a), while still maintaining its distinctiveness in how it apprehends problems (

Bialecki 2018b). This will have another advantage. Focusing on broader formations allows us to see what the social effect of speculative thought is. A study of speculative thought that does not have within it avenues that double back from the imaginative and the virtual to the social, and thus do not thread backs to concrete expressions, might say something about the potential cognitive combinatory possibilities of the human species, but an interrogation of such forms does not tell us anything regarding how actual collective processes operate.

But how does one study speculative imagination, not as fiction, but as something lived in the world?

2. “Speculation Is My Religion” (Methods and Object)

Future Day Saints did not fall into my lap from out of the sky, or at least not literally. Rather, a friend of mine sent me a message telling me of the book’s existence while we were on a larger Zoom call. The topic of the Zoom call was what it would take for humanity to settle the solar system and then later the stars. At some point in the conversation, these hypothetical settlers were compared to the handcart pioneers, the celebrated (

Bielo 2017) Mormons who migrated on foot to Salt Lake City and environs to escape persecution they experienced in the United States. Typically held in person in a strikingly large, furnished basement near Provo, Utah (the online format was a result of the pandemic of 2020), this Zoom meeting was the monthly meet-up for the Utah branch of the Mormon Transhumanist Association.

The Mormon Transhumanist Association, or “MTA” as it is often referred to, is an organization whose purpose is to create a community for those interested both in Mormonism and Transhumanism. With the approval of the Mormon Transhumanist Association, I have been studying them for a half-decade now. I have spent numberless hours at their various online forums, have conducted well over a hundred hours of interviews, have attended four annual conferences, and have studied over ten years of survey material on the group.

To understand the MTA, you have to understand transhumanism. Transhumanism is the anticipation of, and advocacy for, imminent innovations in fields as diverse as nanotechnologies, gerontology, cryonics, and artificial intelligence that

might be so species-transformative that those who adopt these technologies will have effectively transcended the human state, becoming something else, something greater, altogether. On the whole, transhumanists tend towards atheism, and often a “new” atheism that is not just skeptical regarding religious truth claims, but hostile to religion having any space in the public sphere. When given anthropological attention, transhumanism is (rightly) seen as a project concerned with achieving immortality through technical means (see

Bernstein 2019;

Farman 2020), and escaping death does indeed seem to be the chief aspiration of most transhumanists. However, that does not exhaust transhumanist ambitions. There is also a cosmological edge to transhumanism, in both the anthropological sense of a concern for ultimate horizons and all-encompassing totalities, but also in the less figurative sense of being concerned with the origins and ultimate fate of the universe. Sometimes this takes the form of speculation about the origins of the universe; a favorite hypothesis here for many Mormon Transhumanists is that this world is a computer simulation of some sort (see

Bostrom 2003). However, when beginnings are not being contemplated, it tends to imagine the propagation of humans and post-humans through outer space; and sometimes this is not just the propagation through outer space, but the transformation of it, where intelligence first colonizes the universe, and then refashions it across the board into thinking matter (

Farman 2012,

2020, pp. 197–235).

The Mormon Transhumanist Association is, as the name would suggest, a society for Mormons who are interested in, and often quite enthused about, the same technological prospects that excite secular Transhumanists. While not massive in size, the group’s growth had been exponential, running from an original fourteen founding members in 2006 to roughly seven hundred and fifty at the time of this writing. What the MTA lacks for in size, it makes up for in influence; it is both the largest, and oldest, religious transhumanist organization; it was also the first religious transhumanist association to receive an official affiliation with H+, the largest existing umbrella organization for transhumanist groups. The MTA is also taken as a model for other religious transhumanist groups, particularly for the more recent Christian Transhumanist Association, with which it has an interlocking board. For the most part, the MTA lives on the internet, through a Facebook page, a network of Twitter users, and a list-serve that has decelerated as the group’s social media presence has intensified. This should not be taken to mean that the group is entirely virtual, however. The chief ritual event in “meatspace” on the MTA’s calendar is the annual conference, where both members and invited guests (drawn from both well-known secular transhumanist and Mormon public intellectual pools) present papers and engage in discussion. In addition to the occasional family social, there are also semi-regular meet-ups in different cities: Seattle, the Bay Area, and Provo (the home to BYU).

The organization is interested in recruiting; for instance, it has produced several “primers” (introductory study guides to the overlaps between Mormonism and Transhumanism). This interest in recruiting is partly because of some anxieties about the constitution of its membership; the organization is overwhelmingly male (though there have been female board members and CEOs) and is rather white. It also does not exclusively consist of members in good standing with the Church, though this is not a source of concern in the way that the gender imbalance is. While most members belong to the Salt Lake-based Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a handful belong to other Churches that spring from Joseph Smith’s “restored gospel” tradition, and many are ex-Mormons who still have some affinity with the culture of Mormonism if not the Church itself. This relative breadth in membership is purposeful, as from the start, the organization rejected the possibility of being a more narrow, confessional group.

The demographic profile just outlined is (again) a function of founder effects. Most of the founding cohort were male BYU graduates who, despite having degrees in fields as varied as linguistics, music, and philosophy, found themselves working in Utah’s burgeoning tech sector during the first decade of the twenty-first century. Through various online sites (such as beliefnet.com) they developed a community of individuals interested in debating religion and discussing technology, and as these conversations took place, many of the members found themselves wondering whether Mormonism’s eschatological promises might not be something doled out by divine favor, but instead something that God expected believers to achieve through their own efforts. There are four aspects of Mormonism that made this thought possible. The first is that it is a thoroughly materialist religion (for example, there is no such thing as ex nihilo creation in Mormonism). While “materialist religion” may seem to be an oxymoron, this claim holds because it argues that everything is made of matter, including God, who is assumed to have a physical body and be situated in a particular place, a fact that will become important later in this essay. Second, concomitant with this belief is the tenet that miracles are not breaks with the natural order, as his held in most expressions of Christian imaginaries, but instead effective use by God of natural laws in ways that are presently beyond our ken. Third, there is the implicit assumption in this rule is that natural laws precede God, which (fourth) makes sense since Mormonism also endorses a full-throated vision of theosis (literally becoming a God) as the ultimate goal for humanity, or at least for those humans who show the proper ethical standards and moral sensibility by both endorsing and existing in accord with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (either in this life or the next, since Mormons believe in proxy baptism for the dead).

Given these doctrinal propositions, it is easy to imagine how a set of Mormons who are already deeply invested in technology, but also have their intellectual appetites whetted by their university training in fields such as the humanities, could imagine theosis as a technical achievement. Such a reimagining of their religion ended up having unforeseen social benefits. For instance, it allows for a rationalist presentation of their faith to unbelieving colleagues in the technological sector. Religious transhumanism also had advantages in their interaction with fellow Mormons. Seeing religious eschatology as a human, technical achievement (albeit one that was perhaps facilitated by a super-human intelligence when it created either the species, the world, or the universe) did certain work for Latter-day transhumanists who had come to doubt tenets of their religion when it is couched in traditional, “supernatural” terms. Religious doubts, sometimes about the supernatural, sometimes about the history and operation of the institutional Church, are increasingly driving Mormons to disbelief; paradoxically, it is often those who start with a serious investment in the truth claims of their religion that end up becoming skeptical of it (see

Brooks 2018). The ideas promulgated by the MTA allowed these Mormons to still present themselves as members in good standing of the Church (though perhaps slightly odd members). This capacity to present oneself as a Church member is important in a world where kinship networks, sexuality (and particularly marriage), and even economic practices are tightly intertwined with religious belief, and where leaving the Church could have disruptive effects on all those categories (

Bialecki 2020;

Brooks 2018). However, most of all, the MTA has allowed members to open up their speculative horizons. While much of the talk in the MTA is about near term technological horizons, they also speculate about

what a transhumanist future may be like. Additionally, many members, particularly the ones who are taken with theosis as a religious or ethical proposition, speculate as to the processes through which, over time, Mormon eschatological promises could be made real. As one Church member in good standing phrased it, when asked about the role the MTA plays in his religious life, “speculation

is my religion”. This is, in a way, Mormon speculative fiction, but as carried out in lives and conversations, as opposed to the restricted space of texts produced by a particular writing industry.

This is not merely about futurist theological musings. This speculative interest finds concrete expressions in numerous ways. There is, of course, a lively interest in consuming science fiction literature in general, including many works penned by Mormon authors. The literature read does not explicitly address outer space as a thematic; for instance, one story that is commonly known and respected in this audience for its melding of Mormon and Transhumanist themes is Steven Peck’s “For Avek, Who is Distributed” (

Peck 2015, pp. 11–14), in which a future Mormon religious official struggles to find a way to baptize a spatially distributed artificial intelligence who wishes to convert; they eventually hit on conducting the baptism by proxy, as is done in the Mormon practice of baptizing the dead. However, other works more directly involve outer space, even if their ties to Mormonism are more apparent in themes than direct references, such as in Orson Scott Card’s

Worthing Saga, which has elements drawn from Mormon cosmology (as just one parallel, it features a planet settled by a single, god-like man who over ensuing ages continues to interact with his progeny).

However, this is more than just passive consumption of genre literature. Space travel is a common topic in both monthly meet-up discussions and the yearly conferences. One meet-up spent over an hour talking about Don Lind, a Mormon space-shuttle astronaut who received permission from NASA to wear his temple garments—often referred to as “magic underwear” by Church detractors—underneath his spacesuit.

4 Online forums often contain quite technical debates about issues such as government-backed and commercial spaceflight; an example is a long-running thread critiquing the software coding practices that were being used by SpaceX, Elon Musk’s space-travel business (

Bialecki 2020, pp. 6–7).

Sometimes this interest can take the form of rather ambitious, large-scale personal projects. One member, a computer programmer for a large entertainment corporation, has, as an individual, recreational project, used mathematical graph theory to analyze astronomical data sets. This analysis was used to map possible pathways between stars that could potentially be used as routes for human (or extraterrestrial) travel through the “local” region of space—with local meaning here the two thousand stars closest to the earth’s sun. This project ended up being presented as both a publication and as a session at GraphConnect, the most prominent annual conference dedicated to the use of graph databases. This work, in turn, led to a collaboration with a postdoc SETI researcher. That later work expanded on the prior project, and used a much more recent astronomical database to map potential networks between stars with known exoplanets; this project was intended to assist scientists looking for technosignatures that could index the presence of alien life.

3. Abrahamic Astronomy

This full-throated Mormon interest in both space and speculation is arguably noteworthy in its form, and perhaps in its level of intensity as well. Some of the particular social and institutional possibility conditions of it have already been addressed, with education, and particularly BYU, being a recurrent theme in both discussions of Mormon speculative fiction and the Mormon Transhumanist Association. But what shaped this imaginary at the level of concepts and cultural material?

While an explicit interest in transhumanism, strictly understood here to mean the larger secular contemporary movement, is unusual in contemporary Mormonism (even as it is rooted in some distinctively Mormon doctrinal claims), a wider Mormon interest in religious speculation is not. Consider this: Joseph Smith’s theological innovations had broken sharply from the more conventional forms of Protestantism that dominated the United States and the United Kingdom at the time. Between the radical materialism already mentioned, and the heady idea that God was once a man (which in itself suggests the existence of other Gods who eased the way for the Mormon God to undergo theosis), much of the traditional Christian metaphysics had to be reimagined. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, many Mormon intellectuals, including some who were a part of the highest echelons of Mormon leaderships (“apostles” in Church governance), took on this labor attempting to harmonize Mormon doctrine with then-contemporary science (see

Givens 2012).

This reimagining included reinventing the relationship between religion and astronomy. Any Mormon reimagining the cosmos, though, would have to deal with Joseph Smith’s presentation of revelations concerning the planets and the stars. In part, this was because Mormonism is a post-Copernican religion, meaning that, in harmony with the scientific consensus of the time, it assumed a heliocentric solar system and imagined a plurality of (inhabited) worlds orbiting different stars. The basis of this belief, though, was not astronomical, but theological. (See

Paul 1992). For example, the “plurality of worlds” doctrine, which predicts numberless inhabited planets, is based on passages in the Book of Moses, a canonical scripture that Joseph Smith wrote while “retranslating” the Bible through revelation (as opposed to the more conventional means of translation); in it, God speaks to Moses, and after relating a version of the Genesis creation myth, goes on to state that

And worlds without number I have created; and I also created then for my own purposes; and by the Son I created them, which is mine Only Begotten…But only an account of this earth, and the inhabitants thereof, give I unto you. For behold, there are many worlds that have passed away by the word of my power. And there are many that now stand, and innumerable are they unto man.

(Moses 1: 33–35)

In short, the earth is just one world among the many that God has created and populated. This idea, however heady, though, is not the only astronomical discussion in canonical scriptures that are particular to Mormonism.

More cosmological revelations are found in the Book of Abraham, which Smith is said to have translated from some funereal documents that came with an Egyptian mummy that the Church purchased in 1835.

5 Most of the book is spent presenting an alternative history of the Biblical Abraham, including narrating Abraham’s escape from an attempt to sacrifice him by Chaldean priests. Further on, though, via both the Urim and Thummim (understood in Mormonism as a pair of devices used in “spiritual” translation) and revelation from God, Abraham learns about what is sometimes called “Abrahamic Astronomy” (

Paul 1992).

Abrahamic astronomy is predicated on the idea of a plurality of worlds, as in the Book of Moses, but also on a hierarchy of celestial objects as presented in the Book of Abraham. There is the star Kolob, which is described as “nearest” to God (Abraham 3: 3), with nearest usually understood in terms of physical proximity, as it was in

Future Day Saints.

6 Something that could be understood as akin to time dilation functions on Kolob, where “one revolution was a day unto the Lord, after his manner of reckoning, it being one thousand years according to the time appointed unto that whereon thou standest.” (Abraham 3: 4). Additionally, Kolob does work organizing the celestial sphere; that star “governs” the “lesser lights” (which are referred to as the “Kokaubeam”), meaning other stars and planets (Abraham 3: 3, 13, 16).

This revelatory Abrahamic Astronomy fired the imagination of interpreters who were working out a new Mormon cosmology. Many realized quickly that not only would this mean a break with Bishop Ussher’s claim that the world began on October 23rd, 4004 BC, but also with the relatively more expansive, but still comparatively recent, attempts at that period to estimate a geological “deep time”. As W.W. Phelps, an early leader of the Latter-day Saints, wrote to William Smith (the brother of Joseph Smith),

…and that eternity, agreeably to the records found in the catacombs of Egypt, has been going on in this system (not the world) almost 2555 millions of years: and to know at the same time that deists, geologists and others are trying to prove that matter must have existed hundreds of thousands of years:—it almost tempts the flesh to fly to God, or muster faith like Enoch to be translated and see and know as we are seen and known!”.

It is ironic that while many Christian religious thinkers were criticizing the geological claims of writers like James Hutton and Charles Lyell for expanding pre-history, Mormons were instead mocking them for truncating the age of the world.

One of the first book-length exposition on Mormonism was by Parley Pratt, an early convert and determined missionary, who later achieved the rank of “Apostle”. His 1855 book,

Key to the Science of Theology, has been described as an “audacious” reimagining of Christian cosmology (

Givens 2012). In it, he spends most of its time sketching out Mormon views on topics such as the “Council of Gods” responsible for the genesis of the world and more particularly for the genesis of humanity, the physical nature of Gods as beings of “flesh and bone”, the arc of biblical history, and the “Plan of Salvation” (which is how the salvific and eschatological doctrines of the Church are sometimes referred to). However, near to the end of the book, when he starts discussing what might be called the sociology of Gods, Pratt’s statements begin to sound like science fiction. Thinking of the future lives of divine beings, he predicts that

Planets will be visited, messages communicated, acquaintances and friendships formed, and the sciences vastly extended and cultivated … The science of astronomy will also be enlarged in proportion to the means of knowledge. System after system will rise to view in the vast field of research and exploration! Vast systems of suns and their attendant worlds, on which the eyes of Adam’s race, in their rudimental sphere, have never gazed, will then be contemplated, circumscribed, weighed in the balance of human thought, their circumferences and diameter be ascertained, their relative distances understood. Their motions and revolutions, their times and laws, their hours, days, weeks, sabbaths, months, jubilees, centuries, millenniums and eternities, will all be told in the volume of science.

Pratt’s statement is not just a vision of a cosmic future, but also an imagining of the recovery of a lost cosmic past as well. Pratt goes on to predict that

[T]he science of history will embrace the vast “univercœlum” of the past and present. It will, in its vast complications, embrace and include all nations, all ages, and all generations; all the planetary systems in all their varied progress and changes, in all their productions and attributes.

It will trace our race in all its successive emigrations, colonies, states, kingdoms and empires; from their first existence on the great, central, governing planet, or sun, called Kolob, until they are increased without number, and widely dispersed and transplanted from one planet to another, until occupying the very confines of infinitude…

Given these incredible visions, it is striking that this work is also considered to be a “great synthetic work”, and is well regarded as an excellent piece of early Mormon religious commentary to the present day (

Givens 2012, p. xvii).

It is difficult to say across the board what the place of these nineteenth-century doctrines are in the twentieth and twenty-first century. Some Latter-day Saints took them quite seriously; some did not. The idea of a plurality of worlds is occasionally referenced in Church publications, usually as an example of a Mormon doctrinal concept proven accurate by science, suggesting a vindication of the Church’s claim to truth; this is a line of apologetic argument that goes back to the early twentieth century (see, e.g., the book

Joseph Smith as Scientist,

Widtsoe 1908, pp. 45, 150). More recent forms of this argument have focused on the Drake equation, an astronomical formula designed to estimate the number of possible advanced technological civilizations that may exist at any given moment within our galaxy (see, e.g.,

Johnson 1970;

Paul 1992, pp. 192–227).

On occasion, the doctrine of the plurality of worlds will be used to make a more interesting claim regarding the nature of extraterrestrial life. In 1971,

New Era, a Church-operated magazine intended for a “youth” audience, published an article meant to dovetail on the excitement generated by the then-recent American Moon landing. In it, Kent Nielsen, a BYU Philosophy professor, noted that if there ever were contact with intelligent alien life, the Latter-day Saints as a community would be “at least partially prepared for such an event” due to its scriptural tradition. Because of this tradition,

[b]eing joint-heirs of all that the Father has, we may then look forward to using those powers to organize still other worlds from the unorganized matter that exists throughout boundless space. Creating other worlds, peopling them with our own eternal posterity, providing a savior for them, and making known to them the saving principles of the eternal gospel, that they may have the same experiences we are now having and be exalted with us in their turn—this is eternal life.

Given this, heaven has to not be read as some cloudy realm outside of space and time, but rather as

outer space. As he says,

We do not know how extensive is the order of heavens that pertain to our Lord Jesus Christ and that were created by him. It may consist of the local group of stars to which our sun belongs, or of our whole galaxy, or of our cluster of galaxies, or of all of the galaxies we have so far discovered.

However extensive heaven is, though, one thing could be said about the aliens who might people it; they would not be the “green, bug-eyed monsters” of science fiction. Because they would be “of the race of Gods”, as we are, they would look like us:

There is nothing more fundamental in God’s revelations than the basic premise that we are of the race of Gods. We are of his species. God looks like us. We look like him. He has two arms, two legs, a head—indeed, Jesus said, “If ye have seen me, ye have seen the Father.” Obviously, God’s sons and daughters would be of his species, would resemble him. This was one of the basic truths Joseph Smith knew after his vision in 1820. Consequently, people on other worlds would be like us, because we are all his children.

This crowded cosmos was juxtaposed with the cramped world of “unbelievers”, such as Saint Augustine, who is presented as doubting that, if there was land “on the other side of world,” it could not be inhabited by “men.” (

Nielsen 1971). Mormonism, in contrast, promises a far more expansive—and veridical—vision of the universe, Nielson suggests.

Nineteenth century scripture and speculation about Kolob has also been inherited in many different ways by later generations of Latter-day Saints. Both Kolob and the idea of a plurality of worlds are present in

Mormon Doctrine (1958), a book written by

Elder Bruce McConkie (

1958). At the time of its publishing, McConkie was a member of the “counsel of the seventies”, an important governing organ of the Church; he would go on to become an apostle, and even later, the First President of the Church. This text may seem authoritative until one learns that despite McConkie’s status, the book was never officially endorsed by the Church, and the first edition was officially criticized both for its astringent tone and for what were claimed to be numerous doctrinal errors. This did not mean that McConkie would cease endorsing Abrahamic Astronomy. In the 1980s, for instance, McConkie would again refer both to Kolob and the plurality of worlds it in passing in a homiliac essay on creation for

Ensign, a Church-run periodical sent to effectively all of its members (

McConkie 1982). The focus in that article was more on the idea that a day on Kolob, and hence a day for God, was one thousand years long; this allowed a more expansive reading of what a “day” meant in the Genesis account.

Kolob certainly has a place in more literalist aspects of Mormon, as shown by the work of W. Cleon Skousen, a BYU Religion Professor and author of

The Naked Communist, a book that was popular among conservative circles. Kolob makes its appearance different book that Skousen penned,

The First 2000 Years, which presents itself as a history of “the first 2000 years of Human history—from Adam to Abraham” (

Skousen 1997, p. iii). In it, relying on the prophetic authority of the third Church President John Taylor,

7 Skousen states that Earth originated near Kolob and then traveled to its current position; Taylor is quoted as saying, “this earth which had fled and fallen from where it was organized near the planet Kolob” (

Skousen 1997, p. 57). Skousen also suggests that after the resurrection, the earth would return to Kolob. (This is a claim that has been debated, tongue in cheek, once on the MTA Facebook group, where members argued about whether it would be geothermal heat or nuclear fusion that would heat the Earth during this long, cold galactic voyage through the vacuum of space.) Skousen went on to claim that Abrahamic astronomy is in harmony with contemporary scientific astronomy, and finally suggest that Kolob was most likely located within our galaxy.

There have even been efforts to be more approximate in situating Kolob. Lynn Hilton is a retired education professor from (as might be guessed at this point) BYU; he is perhaps best known for having led an archeological expedition to identify the spot where Lehi is supposed to have built his ship to sail to the new world. In his book

The Kolob Theorem (1993), Hilton has argued for Kolob being situated in the center of the Milky Way, hidden behind a wall of interstellar gas and dust (which he refers to as a “veil”, an allusion to the barrier of forgetfulness that keeps humans from remembering their pre-mortal existence in Mormon cosmology). Parenthetically, BYU should not be taken as Kolob-obsessed; scholars in the astronomy department, for instance, were capable of writing educational material for a popular Church audience about much more sedate topics, such as the stellar main sequence (see, for example,

McNamara 1968). However, this imaginative sobriety regarding astronomy was obviously not a universally held trait on that campus.

But Kolob was more than an object of religio-astronomic contemplation and theorizing. Kolob also has life as a metaphor. This metaphor has sometimes leaned into the astronomic side: a Princeton trained BYU astronomer, David Allred, has tried to explain the role played by the planet Jupiter’s gravity in stabilizing the orbits of the terrestrial planets, and also shielding the inner solar system from cometary bombardment, by describing the gas giant as “a type of Kolob” in our Solar System. (

Allred 2007, p. 62). However, by a whole order of magnitude greater, Kolob is seen as a chiefly religious, and not a scientific, metaphor. As said in a Church-issued teacher’s manual designed to assist in children’s religious education, “Kolob…might also figuratively describe the greatness of Jesus Christ.” (Anon: 70). Then there is Kolob as a general piece of Mormon pop culture. It is incorporated into the title of a well-known, though somewhat difficult to sing, hymn, “If You Could Hie to Kolob”, or sometimes used as part of some salutation (I have heard of a Mission president’s wife whose closing words to departing missionaries would be “Love you to Kolob and back!”). Sometimes Kolob even is the punchline to a narrative; there is a story about some village-atheist type who tried to debate two Sister Missionaries he found on the street by asking “if God exists, where is he? Huh? Where does he exist?” only to have one of the missionaries, hoping to cut the interaction short, reply with tired exasperation, “Kolob. He lives on Kolob.” Kolob is also just an embarrassment for some, a piece of Mormon trivia that makes Joseph Smith sound like some crank. However, mostly, as one MTA member pointed out to me, the work Kolob does is impart a sense of wonder, to create something like a religion-inflected taste of the cosmic sublime. This is an aesthetic sensibility more than a cognitive proposition, of course, but that does not mean that it does not have effects as well.

Perhaps the chief example of this sense of cosmic religious wonder associated with Kolob can be found within Temple Square, the ten-acre space located right in the heart of Salt Lake City. Two of the most iconic buildings of the Church can be found on those grounds: the Salt Lake City Temple and the Salt Lake Tabernacle (the latter structure is home to the Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square, formerly known as the Mormon Tabernacle Choir).

8 It is also home to one of the most iconic pieces of Mormon art. In Temple Square’s North Visitor’s Center, there is a replica of

Christus, a nineteenth-century Dutch statue of Jesus with outstretched arms. Since the middle of the twentieth century, this statue has been used as one of the visual calling cards of the Church; an image of this statue appears as a Church emblem on websites and printed material, and much smaller replicas of this statue are available at Deseret Books, a chain of religious bookstores that (by way of a holding company) is owned by the Church. A gallery in the visitors’ center is dedicated exclusively to the Christus statue; it is a large, round room that one reaches by ascending a long, curved ramp. The room holds several benches for those who wish to sit and contemplate the statue for a prolonged period. From time to time, a prerecorded first-person monologue “by” Jesus is played for people viewing the statue. On a small touch-screen panel near the exit, there are different settings for multiple languages—including languages such as Fijian or Finnish. There are also settings that allow different background music to be played that are labeled “Special Easter” and “Special Christmas”; at the one time I stayed in that room for a prolonged period, there were two sister missionaries whose job it was to select the appropriate language for viewers, and they delighted in my request to play numerous different languages just so I could hear them.

Additionally, behind as well as above the Christus statue is a large mural, a panorama that covers all of the chamber’s curved wall, except for a window facing south towards the Temple, as well as the ceiling. That mural was painted in 1966 by a non-Mormon commissioned artist named Sidney E. King, and the painting is of outer space. That piece of art shows the planet earth, floating directly behind the

Christus Jesus; other planets (such as Saturn and Mars) as well as some well-known astronomical objects (Andromeda, the Horsehead nebula) are also depicted. There are also stars there. The stars are painted so accurately that airline pilots have supposedly stated that they could use them to navigate by (

Campbell 2017a). However, these stars and planets are positioned as they would have appeared in the Northern Hemisphere on a specific day—April 6th, 1830, the day that Joseph Smith formally founded the Church.

Art historian

Mary Campbell (

2017b) has argued that this mural, called

Creation, should be read as a space-age masculine, patriotic mural, since it was a part of a larger trend of space-themed American religious paintings of the period, which were an epiphenomenon of a mid-twentieth century religious interest in the “Space Race” (see, e.g.,

Osborne 2015). However, Campbell also notes that

Creation is redolent of Mormon cosmology as well. The chief visual icon of the Church, located in the geographical heart of the contemporary Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,

Creation shows the degree to which religious awe and the cosmic sublime have been laminated together in mainstream Mormonism.

4. Conclusions: Speculative Religion and Recursive Time

Of course, even this sense of wonder has limits in its reception: one artistically inclined, non-MTA Mormon millennial-generation woman told me dismissively that she was never really into that much of the “planet stuff”. Additionally, it would be wrong to think that Abrahamic Astronomy and Kolob form an intellectual straitjacket, a set of doctrines that all Mormon artists, authors, and scholars are obliged to follow. For example, when Matt Page, the author/artist of Future Day Saints, was asked about the planet/star from the Book of Abraham, he reluctantly admitted that since he believed God had a material body, he must believe that there is something like Kolob out there, but he was also quick to present this belief as a function of an existential commitment to his faith, stating that if he’s going to believe something, he’ll push his belief as far as he can go. At the same time, this commitment to the idea of Kolob did not prevent him from abandoning the doctrine that other members of what Nielson refer to as the “species of Gods” looked like humans. While Future Day Saints did present different strains of Homo Sapiens who had traveled to New Eden from worlds independent of Earth, Page also signaled a desire for a more inclusive, multiracial Church by also adding to the roster of interplanetary immigrants several groups of wildly different, non-human aliens who also had been visited by Jesus after the resurrection. (Notably, on these non-human worlds, Jesus appeared in the form of whatever species of sentient life that was peculiar to each planet.) Like many other Mormon science fiction authors, for Page, Abrahamic astronomy is not a group of doctrines that he was locked into; it is instead an open-sourced set of tools to be used—or put aside—as needed for the artistic project at hand.

However, with all these qualifications, the influence that Abrahamic Astronomy has had in on Mormon Transhumanism and Mormon Speculative writing is still there. In this, there are anthropological lessons here about the importance of speculative religion. In anthropology, religion is often seen as either an issue of belief (

Geertz 1966), even if belief is treated as a sometimes problematic category (See

Lindquist and Coleman 2008), or an issue of institutional and embodied discipline (See, e.g.,

Hirschkind 2006;

Mahmood 2011), even if this discipline must be counterbalanced with leniency (

Mayblin and Malara 2018). Additionally, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with the centrality of “having a testimony”, and the importance of institutional oversight, certainly has elements that can be seen as falling into one of these categories or the other. However, while Kolob was obviously a matter of belief for some of those we looked at here, it was an object of speculation for others—a religious category that arguably falls outside of both discipline and belief, seeing how it is a kind of experimental thought and imagining that is carried out in the subjunctive mode. This essay, then, could be seen as a first step in writing the anthropology of religious speculation.

However, this also brings us back to our original anthropological question: what is necessary for there to be an imagined future? The combination of Abrahamic Astronomy and theosis suggests that a past can be useful in building a future. After all, French and American revolutionaries often used the language and visual icons of Republican Rome to communicate their ambitions and ethics. However, the case at hand suggests that when it comes to thinking through the true alterity of outer space, it cannot be any kind of past. It must be a recursive or fractal kind of past, where the past can also be kind of future. After all, the core of Mormon doctrine, at least as interpreted by these groups, is that the past is also a kind of future, and that the tale of how God overcame his humanity and became God so as to craft the present corner of the universe is also the tale of how, through either spiritual exercise or religiously inspired technological mastery, future humans will also achieve theosis and perform the same work of creation. (This imagination of space exploration as a return to already existing cosmic progenitors is what disassociate this fantasy from the usual settler-society taint rooted that is in the history of the dispossession of indigenous lands – such as, ironically, what was done by 19th century Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory.) Imagining what a secular version of this vision would be like, of course, is a harder problem; it may be that the intellectual material needed to craft this sort of intellectual framework is absent, or the aesthetics and sensibilities of secularism somehow preclude it. However, we cannot know until the work of producing such an imagining has truly begun.