Jewish and Hebrew Books in Marsh’s Library: Materiality and Intercultural Engagement in Early Modern Ireland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Archbishop Marsh and His Library

3. Exploring the Jewish Books in Marsh’s Library

3.1. Engagement with Jewish Culture: Christian Hebraism—And Beyond

3.1.1. Bibles and Translations

3.1.2. Rabbinic Texts and Commentary

Protestant attitudes to the study of Hebraica in the early modern period were characterised by a profound ambivalence. This uncertainty was rooted in a long-standing structural tension within Christianity between opposing impulses of intellectual curiosity and theological repudiation towards rabbinical literature.

3.1.3. Jewish Texts Aimed at Christian Readers

3.1.4. Jewish Texts—Beyond the Usual Suspects

3.2. The Production, Use, and Travel of Jewish Books in Early Modern Europe

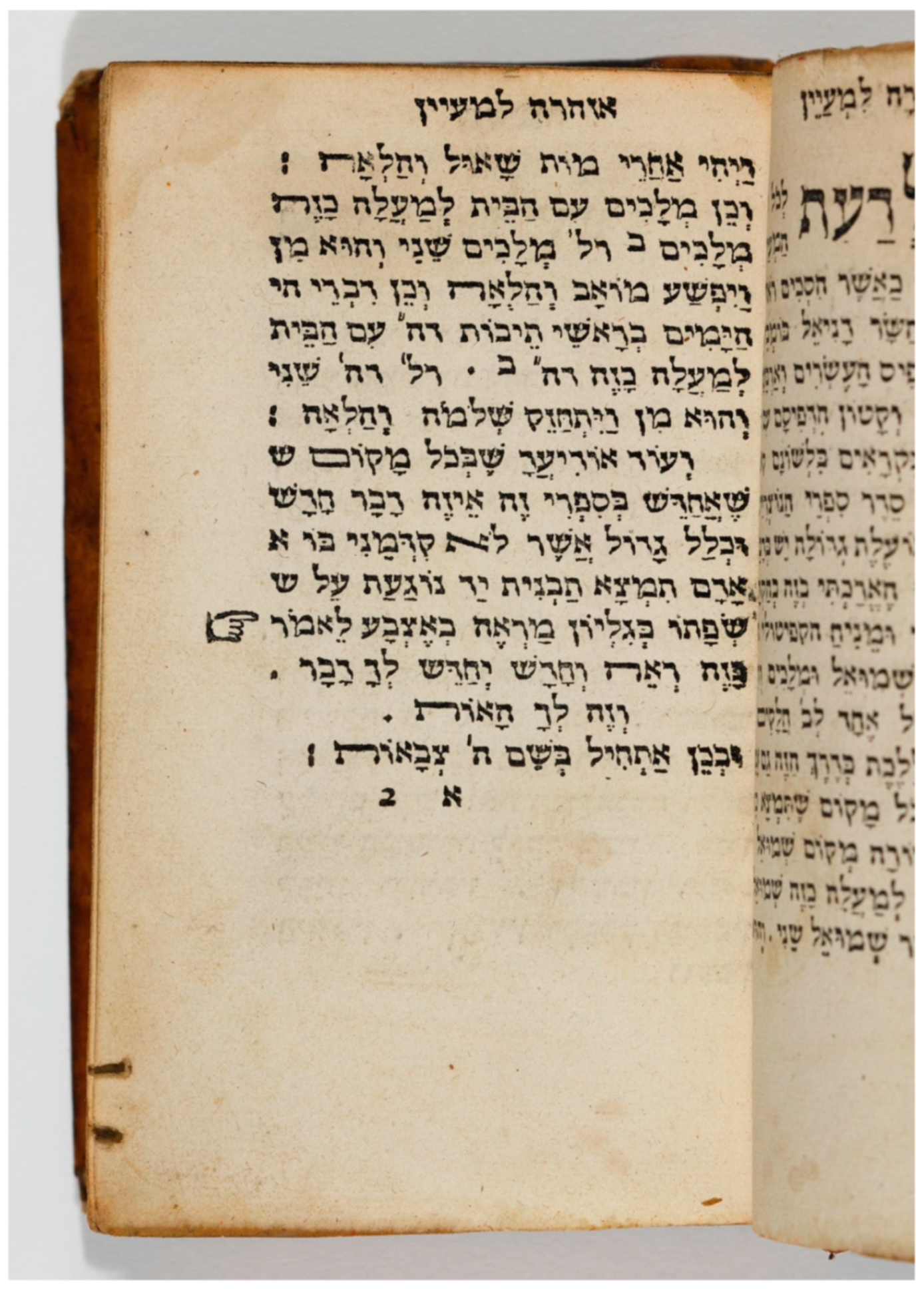

It is imperative to recall the co-operation between Sephardim and Ashkenazim in the book industry. Sephardim produced Yiddish books and Ashkenazim printed texts for the Sephardi community. Consequently, an Ashkenazi from Prague arrived in Amsterdam, worked in rich private Sephardi libraries and published in 1680 the first ever Hebrew bibliography, Siftei yeshanim (2015, p. 2).

3.3. Snapshots of Jewish Life in Early Modern Ireland and Beyond

The mixed Hebrew and Yiddish inscription, which is based on Lamentations 1:16, mentions that Hirsh died on the second day of Passover 5464 (=1704) and was buried in Dublin, Ireland. It can be surmised that, for whatever reason, both brothers were in Dublin and after 1704 (Hirsh’s death) the book was sold to Archbishop Marsh, or came into his possession in another way. This is probably the oldest copy of a book with a glimpse into a Jewish Dublin couleur-locale (Berger 2015, p. 3).

At the end of the work we find the signatures of three different censors. In the last page, we read “Dominico Irosolomi.no”, “Aless.ro scipione 1597” and, in the previous page, “visto per me Gio domenico carretto 1618”. From this single book copy, one can learn much about not only the reading habits of Jews, but the censorship regime of the Counter-Reformation Catholic Church in Italy in the late sixteenth century. The well-known Domenico Irosolimitano worked with Alessandro Scipione and Laurentius Franguellus, all of them apostates, in the Mantuan censorship commission from 1595 to 1597 … Jews took their books to be censored in great numbers, probably in fear of the penalty for having uncensored books in their possession. After looking at the books and censoring them accordingly, censors would sign at the end of the book and add the date to their signatures… Thus Irosolimitano’s and Scipione’s signatures together and the latter’s addition of the date—1597—leaves no doubt that this copy of Milḥamot ha-Shem was under the scrutiny of the Mantuan commission in 1597. Yet, bearing a censor’s signature did not free the book’s owner from the obligation of bringing the book to subsequent censorship commissions. This is the case with this copy, as attested by the signature of Giovanni Domenico Carretto dated to 1618, who worked censoring Hebrew books also in Mantua from 1617 to 1619. This footprint then situates this copy in Mantua still in 1618, where it had probably been since 1597 or earlier. … Printed in Riva di Trento by Jacob Marcaria in 1560 under the sponsorship of the bishop of Trento, this copy tells us about actual collaboration and exchange between Jews and Catholics in a cultural and intellectual endeavour such as printing books in Hebrew in Northern Italy. This was possible only before the Council of Trent was finished in 1563, as the consequences of Counter-Reformation largely affected relationships between Jews and Catholics. This can be observed very well in this book, as it was censored twice in Mantua, in 1597 and in 1618, following the establishment of censorship commissions.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altmann, Alexander. 1972. Eternality of Punishment: A Theological Controversy within the Amsterdam Rabbinate in the Thirties of the Seventeenth Century. Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research 40: 1–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Bradford A., ed. 2020. From Scrolls to Scrolling: Sacred Texts, Materiality, and Dynamic Media Cultures. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Angel, Hayyim. 2009. Abarbanel: Commentator and Teacher Celebrating 500 Years of His Influence on Tanakh Study. Tradition 42: 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Aranoff, Deena. 2009. Elijah Levita: A Jewish Hebraist. Jewish History 23: 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, Elizabeth. 1954. Robert Estienne, Royal Printer: An Historical Study of the Elder Stephanus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Shlomo. 2004. An Invitation to Buy and Read: Paratexts of Yiddish Books in Amsterdam, 1650–1800. Book History 7: 31–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Shlomo. 2015. From Lublin to Dublin (by Way of Amsterdam). Marsh’s Library. Available online: https://www.marshlibrary.ie/from-lublin-to-dublin-jewish-books-in-marshs-library/ (accessed on 18 October 2019).

- Burnett, Stephen G. 2005. Christian Aramaism: The Birth and Growth of Aramaic Scholarship in the Sixteenth Century. In Seeking Out the Wisdom of the Ancients: Essays Offered to Honor Michael V. Fox on the Occasion of his Sixty-Fifth Birthday. Edited by Ronald L. Troxel, Kelvin G. Friebel and Dennis R. Magary. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, pp. 421–36. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, Stephen G. 2012. Christian Hebraism in the Reformation Era (1500–1660). Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Euan. 2001. Early Modern Europe: An Oxford History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, W. Gordon. 2019. Visualising Revelation for Luther’s New Testament (1522–1546): Debt, Design and Development. Biblische Notizen 183: 73–99. [Google Scholar]

- Casson, Lionel. 2001. Libraries in the Ancient World. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, Justin A. I. 1999. Apocrypha Canon and Criticism from Samuel Fisher to John Toland, 1650–1718. In Judaeo-Christian Intellectual Culture in the Seventeenth Century: A Celebration of the Library of Narcissus Marsh (1638–1713). Edited by A. P. Coudert, S. Hutton, R. H. Popkin and G. M. Weiner. New York: Springer, pp. 91–117. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Richard I., Natalie B. Dohrmann, Adam Shear, and Elchanan Reiner, eds. 2014. Jewish Culture in Early Modern Europe. Essays in Honor of David B. Ruderman. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coudert, A. P. 1999. Seventeenth-Century Christian Hebraists: Philosemites or Antisemites? In Judaeo-Christian Intellectual Culture in the Seventeenth Century: A Celebration of the Library of Narcissus Marsh (1638–1713). Edited by A. P. Coudert, S. Hutton, R. H. Popkin and G. M. Weiner. New York: Springer, pp. 43–69. [Google Scholar]

- Coudert, A. P., S. Hutton, R. H. Popkin, and G. M. Weiner, eds. 1999. Judaeo-Christian Intellectual Culture in the Seventeenth Century: A Celebration of the Library of Narcissus March. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- D’Avray, D. 2004. Printing, Mass Communication, and Religious Reformation: The Middle Ages and After. In The Uses of Script and Print, 1300–1700. Edited by J. C. Crick and A. Walsham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 50–70. [Google Scholar]

- Dane, Joseph A. 2012. What Is a Book?: The Study of Early Printed Books. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Del Barco, Javier. 2017a. A Fantastic Find… from 1489. Marsh’s Library. Available online: https://www.marshlibrary.ie/a-fantastic-find-from-1489/ (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Del Barco, Javier. 2017b. From Italy to Dublin Through Double Censorship. Footprints. Available online: https://edblogs.columbia.edu/footprints/2017/12/10/guest-post-from-italy-to-dublin-through-double-censorship/ (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Efros, Israel. 1919. The Menorat Ha-Maor: Time and Place of Composition. The Jewish Quarterly Review 9: 337–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbane, Michael, and Joanna Weinberg, eds. 2013. Midrash Unbound: Transformations and Innovations. London: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flesher, Paul V. M., and Bruce Chilton. 2011. The Targums: A Critical Introduction. Waco: Baylor University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Francesconi, Federica. 2009. Jews under Surveillance: Censorship and Reading in Early Modern Italy. In Early Modern Workshop: Resources in Jewish History. EMW 2009: Reading across Cultures: The Jewish Book and Its Readers in the Early Modern Period. Available online: https://research.library.fordham.edu/emw/emw2009/emw2009/9/ (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Friedman, Jerome. 1983. The Most Ancient Testimony: Sixteenth Century Christian-Hebraica in the Age of Renaissance Nostalgia. Athens: Ohio University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, Gérard. 1997. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, Raymond. 2009. Manuscript collectors in the age of Marsh. In Marsh’s Library: A Mirror on the World: Law, Learning and Libraries, 1650–1750. Edited by Muriel McCarthy and Ann Simmons. Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 234–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, Raymond, ed. 2003. Scholar Bishop: The Recollections and Diary of Narcissus Marsh, 1638–1696. Cork: Cork University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Eliane. 2007. Judaism without Jews: Philosemitism and Christian Polemic in Early Modern England. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gordis, Robert. 1942. Rabbi Saadia Gaon. The American Jewish Year Book 44: 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Grafton, Anthony, and Joanna Weinberg, eds. 2011. “I Have Always Loved the Holy Tongue” Isaac Casaubon, the Jews, and a Forgotten Chapter in Renaissance Scholarship. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, Joseph R. 2011. Sixteenth-century Jewish Internal Censorship of Hebrew Books. In The Hebrew Book in Early Modern Italy. Edited by Joseph R. Hacker and Adam Shear. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 109–20, 268–75. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Marvin J. 2004. Mars and Minerva on the Hebrew Title-Page. The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 98: 269–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbury, William. 2004. Christian Hebraism in the Mirror of Marsh’s Collection. In The Making of Marsh’s Library: Learning, Politics and Religion in Ireland, 1650–1750. Edited by Muriel McCarthy and Ann Simmons. Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 256–79. [Google Scholar]

- Howsam, Leslie. 2015. The Cambridge Companion to Book History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, Tim, and Joanne McKenzie. 2017. Materiality and the Study of Religion: The Stuff of the Sacred. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, Louis. 1972. The Jews of Ireland: From Earliest Times to the Year 1910. Dublin: Irish University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Idel, Moshe. 2014. Printing Kabbalah in Sixteenth-Century Italy. In Jewish Culture in Early Modern Europe. Essays in Honor of David B. Ruderman. Edited by Richard I. Cohen, Natalie B. Dohrmann, Adam Shear and Elchanan Reiner. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, David. 1982. Philo-Semitism and the Readmission of the Jews to England, 1603–1655. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, David S. 1999. The Prehistoric English Bible. In Judaeo-Christian Intellectual Culture in the Seventeenth Century: A Celebration of the Library of Narcissus Marsh (1638–1713). Edited by A. P. Coudert, S. Hutton, R. H. Popkin and G. M. Weiner. New York: Springer, pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, Marjorie, and Jason McElligott. 2017. Hunting Stolen Books. Dublin: Marsh’s Library. [Google Scholar]

- Léoutre, Marie, Jane McKee, Jean-Paul Pittion, and Amy Prendergast, eds. 2019. The Diary (1689–1719) and Accounts (1704–17) of Élie Bouhéreau. Dublin: Irish Manuscripts Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Barry. 1991. Rabbinic Bibles, Mikra’ot Gedolot, and Other Great Books. Tradition 25: 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Manuscript Shelflist of Books Stolen. n.d. Dublin (MS Z3): Marsh’s Library.

- McCarthy, Muriel. 1975. Archbishop Marsh and His Library. Dublin Historical Record 29: 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Muriel. 2003. All Graduates and Gentlemen: Marsh’s Library. Dublin: Four Courts Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Muriel. 2004. Introduction. In The Making of Marsh’s Library: Learning, Politics and Religion in Ireland, 1650–1750. Edited by Muriel McCarthy and Ann Simmons. Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 11–31. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Muriel, and Caroline Sherwood-Smith, eds. 2001. “This golden fleece”: Marsh’s Library 1701–2001, A Tercentenary Exhibition. Dublin: Archbishop Marsh’s Library. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Muriel, and Ann Simmons, eds. 2004. The Making of Marsh’s Library: Learning, Politics and Religion in Ireland, 1650–1750. Dublin: Four Courts Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Muriel, and Ann Simmons, eds. 2009. Marsh’s Library: A Mirror on the World. Law, Learning and Libraries, 1650–1750. Dublin: Four Courts Press. [Google Scholar]

- Menache, Sophia. 1985. Faith, Myth, and Politics: The Stereotype of the Jews and Their Expulsion from England and France. The Jewish Quarterly Review 75: 351–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Michael A. 1967. The Origins of the Modern Jew: Jewish Identity and European Culture in Germany, 1749–1824. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Peter N. 2001. The “Antiquarianization” of Biblical Scholarship and the London Polyglot Bible (1653–57). Journal of the History of Ideas 62: 463–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, David. 2010. Religion and Material Culture: The Matter of Belief. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Osborough, Nial. 2009. Six Anne, Chapter 19: “Settling and preserving a Publick Library for ever”. In Marsh’s Library: A Mirror on the World. Law, Learning and Libraries, 1650–1750. Edited by Muriel McCarthy and Ann Simmons. Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ovenden, Richard. 2020. Burning the Books: A History of Knowledge under Attack. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, James. 1962. Early Christian Hebraists. Studies in Bibliography and Booklore 6: 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pettegree, Andrew, and Arthur der Weduwen. 2019. The Bookshop of the World: Making and Trading Books in the Dutch Golden Age. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poleg, Eyal. 2020. Memory, Performance, and Change: The Psalms’ Layout in Late Medieval and Early Modern Bibles. In From Scrolls to Scrolling: Sacred Texts, Materiality, and Dynamic Media Cultures. Edited by Bradford A. Anderson. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 119–52. [Google Scholar]

- Poleg, Eyal, and Laura Light, eds. 2013. Form and Function in the Late Medieval Bible. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Raz-Krakotzkin, Amnon. 2007. The Censor, the Editor, and the Text: The Catholic Church and the Shaping of the Jewish Canon in the Sixteenth Century. Translated by Jackie Feldman. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raz-Krakotzkin, Amnon. 2014. Persecution and the Art of Printing: Hebrew Books in Italy in the 1550s. In Jewish Culture in Early Modern Europe: Essays in Honor of David B. Ruderman. Edited by Richard I. Cohen, Natalie B. Dohrmann, Adam Shear and Elchanan Reiner. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman, David B. 2010. Early Modern Jewry: A New Cultural History. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheism. [Google Scholar]

- Schrijver, Emile. 2007. The Hebraic Book. In A Companion to the History of the Book. Edited by Simon Eliot and Jonathan Rose. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 153–64. [Google Scholar]

- Schrijver, Emile. 2017. Jewish Book Culture Since the Invention of Printing (1469–c. 1815). In The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 7, The Early Modern World, 1500–1815. Edited by Jonathan Karp and Adam Sutcliffe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 291–315. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, William H. 2008. Toward a History of the Manicule. In Used Books: Marking Readers in Renaissance England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Sholom A. 1964. The Expulsion of the Jews from England in 1290. The Jewish Quarterly Review 55: 117–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, David. 2017. The Jewish Bible: A Material History. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe, Adam. 2000. Hebrew Texts and Protestant Readers: Christian Hebraism and Denominational Self-Definition. Jewish Studies Quarterly 7: 319–37. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooden, Peter T. 1989. Theology, Biblical Scholarship, and Rabbinical Studies in the Seventeenth Century: Constantijn L’Empereur (1591–1648), Professor of Hebrew and Theology at Leiden. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Van Staalduine-Sulman, Eveline. 2018. The London Polyglot Bible. In Justifying Christian Aramaism. Leiden: Brill, pp. 199–229. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, Colin. 1994. Arabic manuscripts in the Bodleian Library: The Seventeenth-Century Collections. In The ‘Arabick’ Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England. Edited by G. A. Russell. Leiden: Brill, pp. 128–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, Colin. 2004. Archbishop Marsh’s oriental collections in the Bodleian Library. In The Making of Marsh’s Library: Learning, Politics and Religion in Ireland, 1650–1750. Edited by Muriel McCarthy and Ann Simmons. Dublin: Four Courts Press, pp. 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. 2013. Early Modern Europe, 1450–1789. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wimpfheimer, Barry S. 2018. The Talmud: A Biography. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yaakov, Elman. 2000. Moses ben Nahman/Nahmanides (Ramban). In Hebrew Bible/Old Testament: History of Its Interpretation, vol. 1, Part Two: The Middle Ages. Edited by Magnae Sabo. Goettingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 416–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zwiep, Irene. 1999. Rome, Lisbon, Naples: The Transmission of Nahmanides’ Torah Commentary: A Continuation on Isaac Maarsen’s Reconstruction of 1918/1923. Studia Rosenthaliana 33: 181–89. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Defining “Jewish books” is of course complex, and the parameters of this category have been the subject of considerable debate. On some of the issues involved, see (Schrijver 2007, 2017). For our present purposes we employ a broad understanding, encompassing books written by and for Jews, as well as Jewish texts specifically aimed at early modern Christian readers; more on the latter in Section 3.1.3, below. |

| 2 | (Hyman 1972, p. 39) makes mention of a meeting of a number of Hebrew scholars at Marsh’s in 1733, including one Abraham Judah—though the others said to have attended were Christian. |

| 3 | The library’s extensive catalogue can be searched here: https://www.marshlibrary.ie/catalogue/. |

| 4 | For more on issues of texts, materiality, and the study of religion, see (Anderson 2020). On paratexts, consult (Genette 1997). Stern’s (2017) study offers a stimulating example of how the study of materiality is crucial to the study of religious texts. |

| 5 | This research builds on important research done by two scholars who have explored the Jewish books in Marsh’s Library. Professor Shlomo Berger, of the University of Amsterdam, curated an exhibit for the library in 2014–2015 entitled, “From Lublin to Dublin (by way of Amsterdam)”, shortly before his untimely death. For this research we have drawn on some of the valuable collation and observations that were made by Professor Berger (2015). In 2017, Dr Javier del Barco undertook three months of research on the Jewish books in Marsh’s Library, in conjunction with the international “Footprints” project (https://footprints.ctl.columbia.edu/), which is tracing the history of Jewish books. Dr Del Barco made a number of significant discoveries and observations in his research, several of which are noted in what follows. |

| 6 | All images used with the kind permission of Marsh’s Library. |

| 7 | For more on the development of the library’s collection, see (McCarthy 1975). Beyond Marsh’s personal collection, other elements of the library also demonstrate a strong interest in Christian Hebraism, including volumes which came from Edward Stillingfleet and Isaac Casaubon. On Stillingfleet, see (Champion 1999); on Casaubon, see (Grafton and Weinberg 2011). |

| 8 | Marsh also collected ancient manuscripts from Hebrew, Arabic, and other near Eastern traditions. His manuscripts are now housed in Oxford; see (Wakefield 1994; McCarthy 2003; Gillespie 2009). |

| 9 | Upon his death Marsh bequeathed all of his remaining books to the library, except those already in the collection. As Stillingfleet’s collection was added before Marsh’s passing, it is possible—indeed, likely—that Marsh owned books which were already in the library and thus were not added to the collection (Gillespie 2003; Horbury 2004). |

| 10 | Marsh inscribed his personal books with his Greek motto, πανταχη την αληθειαν (“Truth everywhere”), normally in the upper right hand corner of the flyleaf or title page. This motto can be seen in a number of the images below. |

| 11 | This volume was unaccounted for in the library until 2017, when Dr Javier del Barco (re)discovered it during his research at Marsh’s Library. See (Del Barco 2017a). |

| 12 | The library also holds an edition of the famous Biblia Polyglotta, or the Complutensian Polyglot; see (McCarthy and Sherwood-Smith 2001, pp. 18–19). |

| 13 | The Footprints Project traces the movement of Jewish books after the rise of print and includes data on a number of works in Marsh’s Library: https://footprints.ctl.columbia.edu/. |

| 14 | On censorship of Jewish texts in this period, see (Hacker 2011; Francesconi 2009; Raz-Krakotzkin 2007; Raz-Krakotzkin 2014). |

| 15 | Another example is a work entitled Sefer Ḥovat ha-levavot (Duties of the Heart), which again comes from Marsh’s personal collection (Marsh’s Library C.3.3.30; the library also holds the 1692 edition). Penned in the eleventh century by the Jewish rabbi Baḥya ben Joseph ibn Paḳuda, this printed edition was created in Mantua, Italy, in 1559, and also bears evidence of censorship; an inscription on the final page reads “visto per mi fra Luigi da [Bologna] 1601”. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anderson, B.A.; McElligott, J. Jewish and Hebrew Books in Marsh’s Library: Materiality and Intercultural Engagement in Early Modern Ireland. Religions 2020, 11, 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110597

Anderson BA, McElligott J. Jewish and Hebrew Books in Marsh’s Library: Materiality and Intercultural Engagement in Early Modern Ireland. Religions. 2020; 11(11):597. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110597

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnderson, Bradford A., and Jason McElligott. 2020. "Jewish and Hebrew Books in Marsh’s Library: Materiality and Intercultural Engagement in Early Modern Ireland" Religions 11, no. 11: 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110597

APA StyleAnderson, B. A., & McElligott, J. (2020). Jewish and Hebrew Books in Marsh’s Library: Materiality and Intercultural Engagement in Early Modern Ireland. Religions, 11(11), 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11110597