1.1. Status Quo of the Empirical Research on Religiosity in Russia

A substantial gap concerning church affiliation and religious practice can be identified in sociological research on religiosity in Russia. While a large share of the population belongs to the Russian Orthodox Church (according to various surveys, between 60% to 80%), low levels of religious practices like regular attendance of religious services, confession, and receiving communion, have been observed (according to various sources, between 3% to 15% of the population). See, for example,

Sahgal and Cooperman (

2017),

Emelyanov (

2016), and Sinelina (

Синелина 2013) for in-depth statistical analyses on this discrepancy.

The low religiosity level is usually explained by the strong link between Russian Orthodox religious affiliation and ethnicity, national identity, or loyalty to the state, which substitutes “true” religious commitment. For example, Zorkaya (

Зоркая 2009) argues that the mass conversion to Orthodoxy since the 1990s is not a manifestation of religious revival, since Orthodoxy is only a component of the post-Soviet identity. On the same topic, Kääriäinen and Furman (

Каариайнен and Фурман 2007a,

2007b) conclude that the “pro-Orthodox consensus”—a positive attitude towards religion and the Russian Orthodox Church in the mass consciousness, accompanied by the conviction that there is no “Russianness” without Orthodoxy—cause the growth of religious affiliation not confirmed by either practice or belief in God. Filatov and Lunkin (

Филатов and Лункин 2005) complete these thoughts by adding that the religious factor only has a minor effect on public life in Russia, as for the majority of Orthodox Christians faith has become just a cultural symbol. In her article, Mchedlova (

Мчедлова 2009) discusses the ambiguity of religiosity in Russian society and distinguishes between two contradictory aspects in the perception of religion: As a cultural identification characteristic, and as a way of life with faith as a primary principle. Lastly,

Karpov et al. (

2012) (Карпов, Лисовская, and Barry 2012) sum up the discussion by stating that religiosity in Russia is characterized by “ethnodoxy”—“a belief system that rigidly links a group’s ethnic identity to its dominant religion”. This lively discussion among scholars in Russia and outside its borders is accompanied by the question of the assessment of religiosity to establish a measurement that allows for the evaluation of the “gap” between the associated members of a religious community and the practitioners. While the interest can lie in a distinction between “true believers” and associated members of a religious community, the greater question behind this discussion is the general comprehensive assessment of someone’s religiosity.

The most systematic among the currently existing and applied approaches in measuring Orthodox religiosity in Russia is the method developed by Chesnokova (

Чеснокова 2009). It is based on the construction of the “Index of churching” (short “V-index”, Russian: “в-индекс”, “в” transcribes as the Latin letter “v” which stands for “воцерковлённость” translated as “churching”).

Churching is characterized as a change in one’s way of life, behavior, and practices caused by conversion to Orthodoxy, and, accordingly, the adoption of a certain belief system. Churching is measured using the V-index, which includes five main indicators: Frequency of attending church services, frequency of confession and communion, observation of fasting, frequency, and type of prayer (church prayers or prayers in one’s own words), and reading of sacred texts. These practices are the key to contemporary Orthodox church life. Each indicator is measured on a five-point scale. The respondents are subsequently classified according to their maximum response level on any of the five scales. In total, there are five groups: (1) “zero group”—the weakest in terms of the level of churching (i.e., “do not attend services”, “did not receive communion”, “do not read holy scripture”, “do not pray”, “do not fast”); (2) “weak churching”—those who selected the second position on any of the five scales at least once, without rising higher; (3) “beginners”—everyone who reached at least the third position at least once; (4) “semi-churching”—those who reached the fourth position on at least one variable; (5) “full churching”—everyone who attained the fifth and highest position at least once on any of the subscales. The main indicators can be supplemented by several additional questions (knowledge of the Church Slavonic language, presence of liturgical literature in the home library, knowledge of the Christian creeds, and participation in the restoration of churches, icons, religious literature). These supplementary indicators allow for an increase in the respondent’s position on the “Index of Churching”. Thus, this scale neither uses a summary or an average score to assess nor does it take into account the unbalanced scores of different participants for the categorization of one’s religiosity.

The Churching Scale is a relatively recent development but has already been adopted for others than the Christian Orthodox religious communities in Russia. Sinelina further developed this approach and applied it in several studies. She constructed a similar measure to study the religiosity of Muslims, which allowed for the examination of the Orthodox and Muslims based on comparable scales. For example, Sinelina discussed the relationship between churching and superstitious behavior (

Синелина 2006,

2013).

The V-scale remains one of the most elaborate and well-thought-out approaches to measure Russian Orthodox religiosity. Its main advantage is the possibility to take different religious practices into account simultaneously. The inquired practices constitute the core of people’s faith life. However, Chesnokova’s approach assumes a certain dynamic—from the lowest to the highest degree of churching. The operationalization is of that kind that the respondents “accumulate” points in different domains of faith life and by that summary score are categorized on different levels of churching. In the early 1990s, when Chesnokova developed this method, such an approach was relevant. Many people had joined the Church recently. There was a great lack of church infrastructure and priests. Most of the newly converted Orthodox did not have any experience in a church way of life nor were they socialized religiously. In this case, each little step on the way of churching was significant. This is directly reflected in the logic of the V-index construction which is based on the respondent’s strongest answer.

Nevertheless, in the current situation, the second decade of the 2000s, the approach of the V-scale is much less relevant as churches have been rebuilt and information about, as well as the access to the religious communities, is greatly available. Hence, the low level of the core religious practices in Russia can no longer be explained so easily. Therefore, the rationale of the V-scale has been criticized. Criticism came, for example, from Lebedev and Sukhorukov (

Лебедев and Сухоруков 2013), who claim that the V-scale overestimates the number of churched Orthodox Russians. They also scrutinized the question wording and pointed out the flaws in some of them (for example, combining several issues in one question, like type and frequency of personal prayer). Hence, there is room for improvement or alternatives, еspecially in the domain of multidimensional scales assessing religiosity, as Prutskova and Markin conclude (

Пруцкова and Маркин 2017).

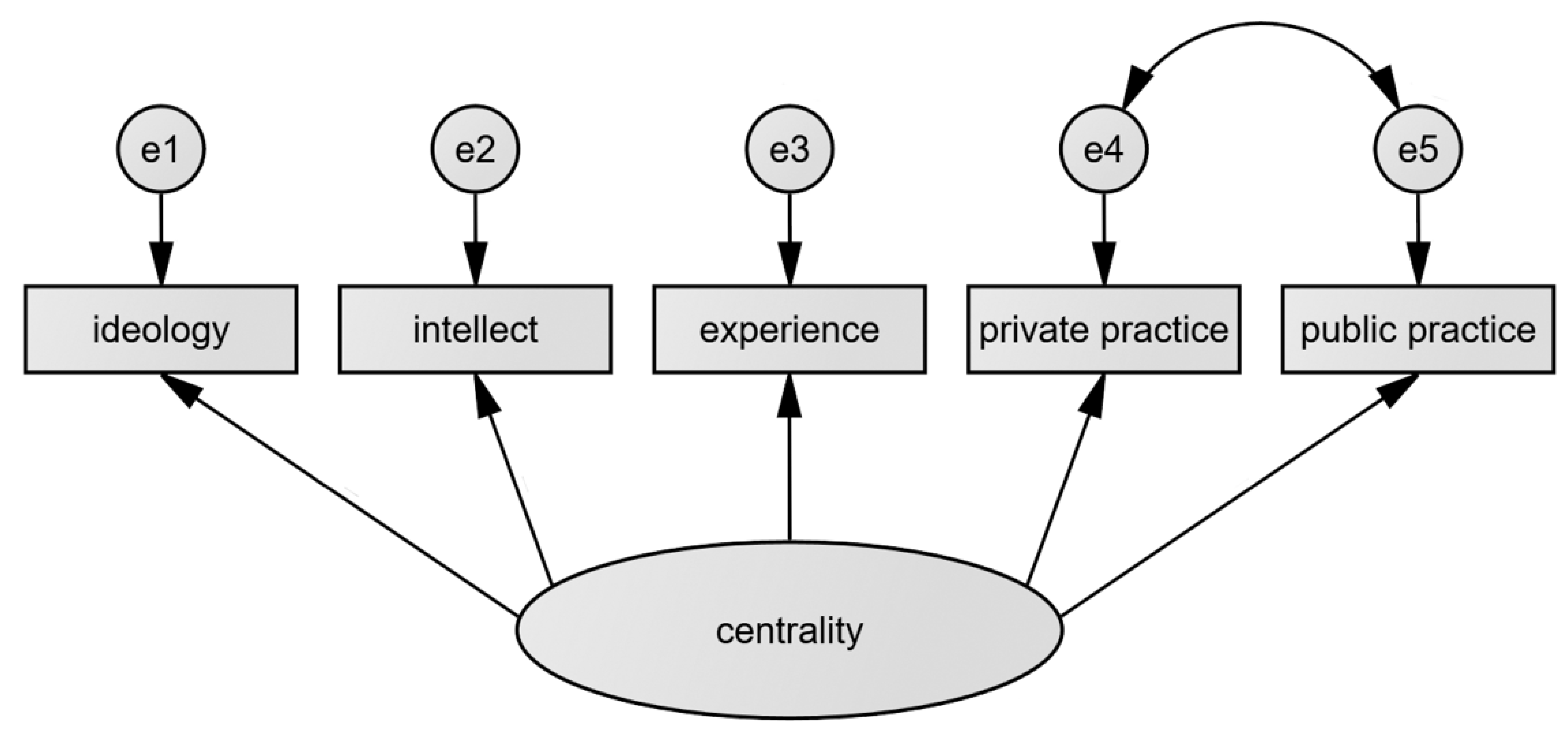

In comparison to the Index of Churching, the Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS) approach discussed in the current paper, allows for a detailed study of several dimensions of Orthodox religiosity—not only private and public practice, but also intellect, ideology, and religious experience. The questions are worded much more elaborately and a more appropriate logic consisting of a total centrality score computation is used. It allows for the comparison of different religious traditions based on the same indicators and takes both the interactive (a human being with a personalized entity) and participative (human being with a universal principle or the like) patterns of spirituality into account.

The CRS already proved its suitability for large-scale comparison in and among different countries and religious traditions (

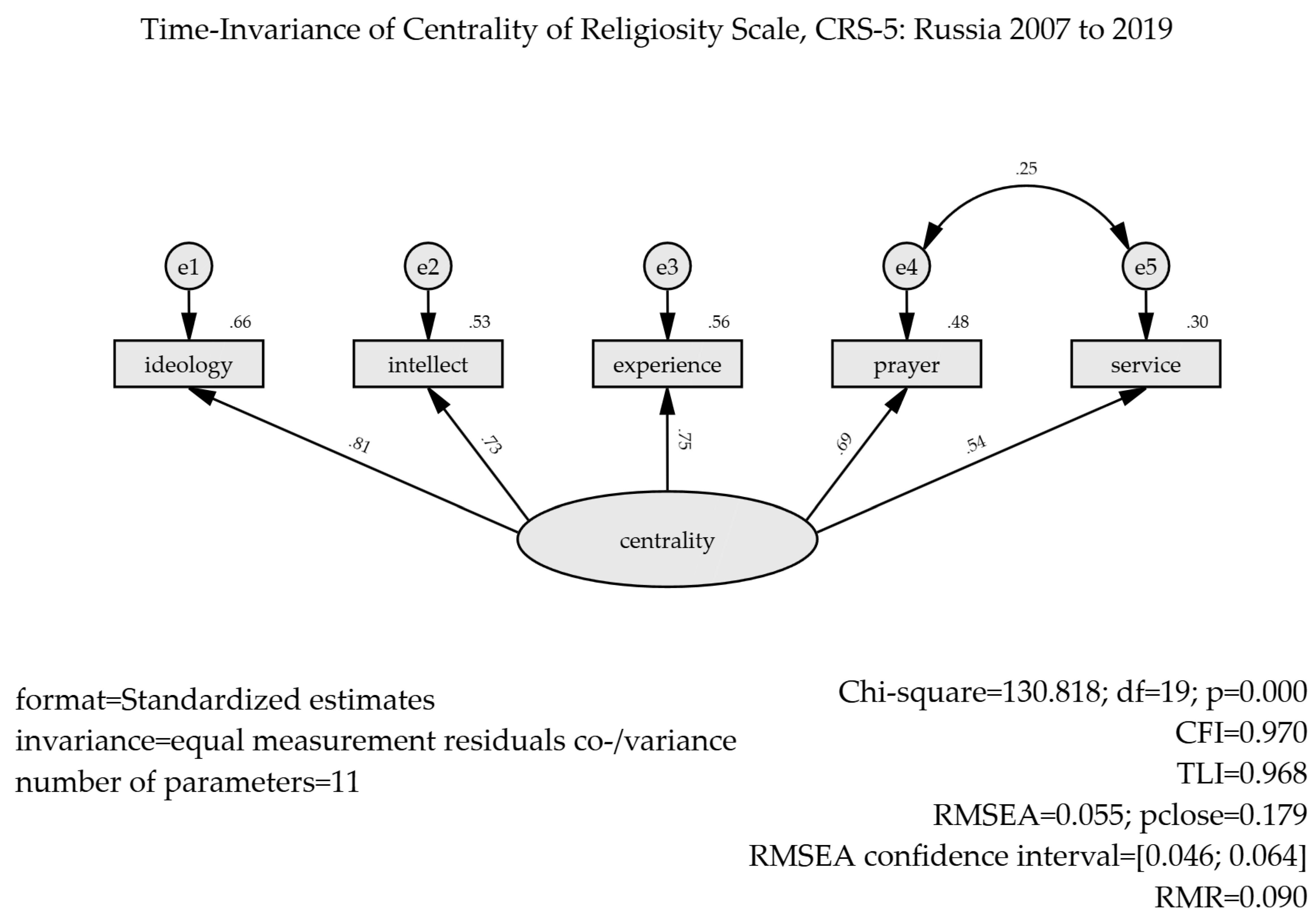

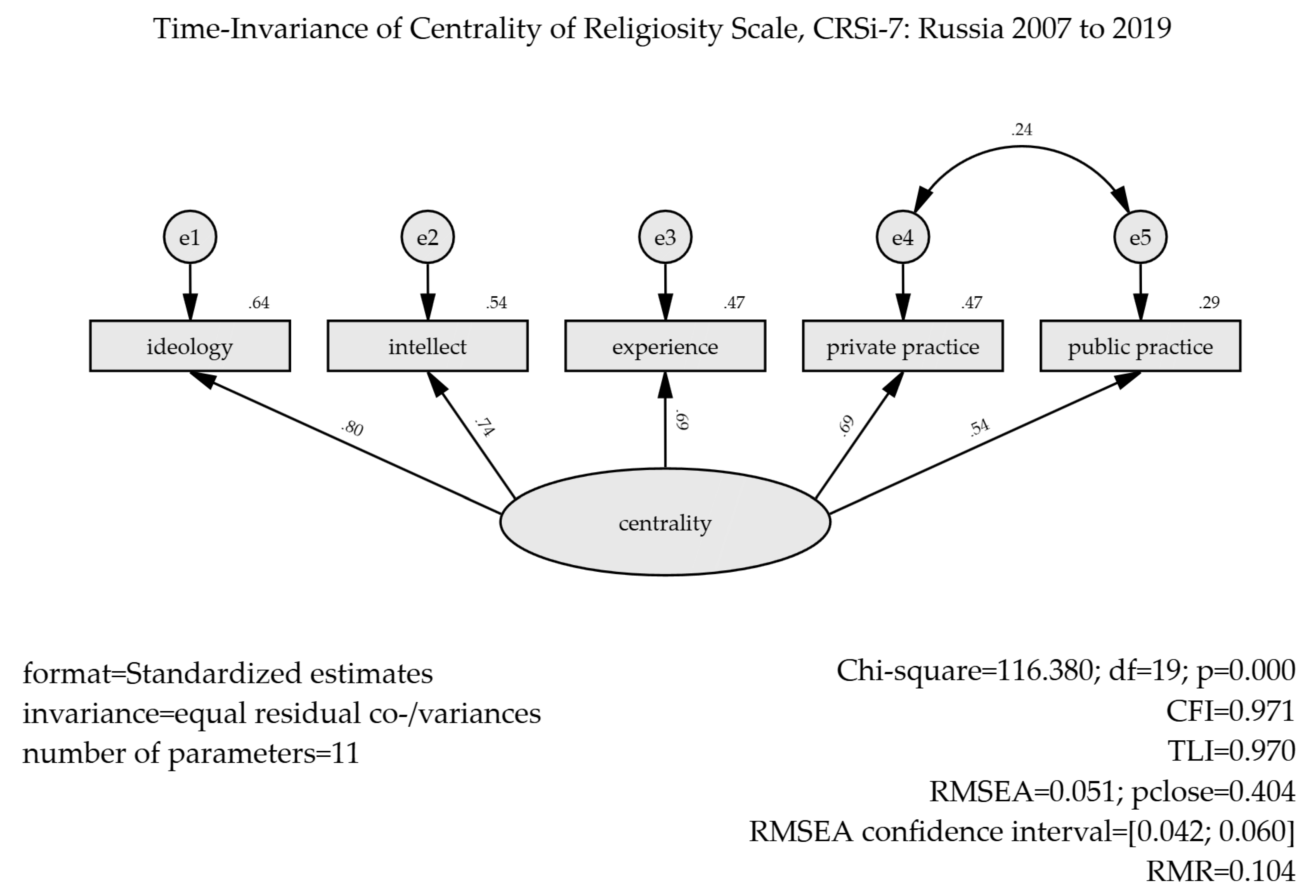

Huber and Huber 2012), but this is not enough. In this paper, we argue that for the empirical examination of the changes of religiosity in a country or a religious tradition or among them a scale should not only be multidimensional and show good internal reliability, but also have consistent psychometrical characteristics over time, in other words, to be time-invariant. Regarding the time-invariance examination of the CRS, it has been studied in the Christian Orthodox tradition of Georgia. In that study by

Ackert et al. (

2020), the scale demonstrated good statistical fit with one particularity of an extra-factorial association between the private and public practice core-dimensions. We, therefore, pick this observation and integrate it into the present analyses as a test of the particularity of the Christian Orthodox Churches.

1.2. Centrality of Religiosity Scale

Speaking about religiosity in Russia, the term is defined as a personal psychological trait in demarcation to religion as an organized, tradition-oriented social phenomenon and to spirituality as a privatized, experience-oriented, individual phenomenon (

Streib and Hood 2016, p. 9). In the present study, religiosity is operationalized by the Centrality of Religiosity Scale. The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS) was developed by

Huber (

2003) as a synthesis of the sociological religiosity model by Charles Y. Glock (

Glock 1962;

Stark and Glock 1968) and the psychological religiosity model by Gordon W. Allport (

Allport 1950;

Allport and Ross 1967). The CRS found wide application as the five- and seven-items-versions of the scale (CRS-5, CRSi-7) were integrated into the international Religion Monitor of the German foundation “Bertelsmann Stiftung” (

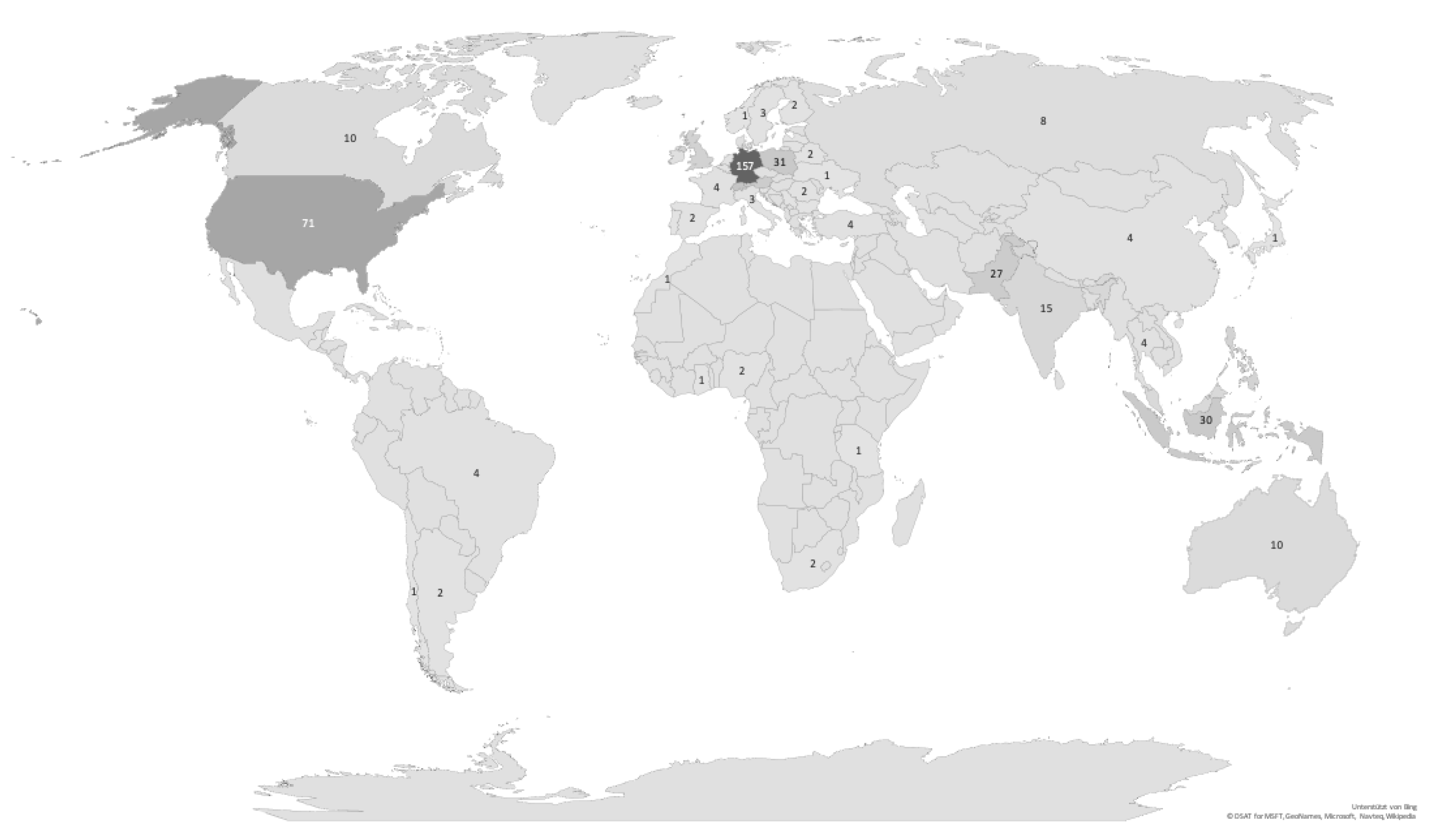

Huber 2009). In the 17 years since the first publication of the CRS (

Huber 2003), 610

1 applications of this scale have been documented so far (see

Figure 1 for a global overview of the applications).

An introduction to the construction principles of the CRS, the core-dimensions of religiosity, the coding of the indicators, the application in different religious cultures as well as the different versions of the CRS is provided by

Huber and Huber (

2012). In this article, we will therefore only briefly describe the basic ideas, the five core-dimensions, and the composite score, or in other words the CRS-index.

1.2.1. Basic Concepts

The measurement strategy of the CRS is based on the following assumptions. First: Individuals mainly articulate their religious attitudes, experiences, and behavior in five core-dimensions i.e., ideology, intellect, experience, private practice, and public practice. Second: The more central religiousness becomes for a person, the more frequently and intensively she or he expresses her or his religiousness in form of the five core-dimensions. Third: The measurement of the general intensity of the five core-dimensions allows for an estimation of the centrality of religiosity, which is a personal construct (

Kelly 1991).

1.2.2. Core-Dimensions of Religiosity

According to

Huber (

2003), there are five so-called core-dimension in which the religious life of a human being is given expression to:

The ideological dimension refers to the social expectation that religious individuals have beliefs regarding the existence and the nature of a spiritual reality. A general indicator of this dimension should exclusively focus on the aspect of the plausibility of the existence of spiritual experience without determining certain concepts of the nature of this reality. This can be achieved by concurrently referring to a theistic and pantheistic concept of the spiritual world—the existence of God or something divine.

The intellectual dimension refers to the social expectation that religious people have some knowledge of religion and that they can explain their views on transcendence, religion, and religiosity. A general indicator is the frequency of thinking about religious issues. It indicates how often religious contents are activated in personal reflections.

The experiential dimension refers to the social expectation that religious individuals have “some kind of direct contact to an ultimate reality” (

Glock 1973). In line with theistic and pantheistic concepts of the spiritual reality two basic patterns of religious experiences can be postulated. In correspondence with theistic concepts, the interactive experiences of God, e.g., the experience of a situation in which God or something divine intervenes in somebody’s/a person’s life. In correspondence with pantheistic concepts the participative experiences of the spiritual reality, e.g., the experience of a situation in which somebody feels they are one with everything.

The dimension of private practice refers to the social expectation that religious individuals devote themselves to the spiritual reality in individualized activities and rituals in private space. There are two basic and irreducible forms of addressing oneself to a spiritual reality—prayer and meditation. In prayer, a transcendent counterpart is addressed. This implies an interactive pattern of spirituality and corresponds with theistic concepts of spiritual reality. In contrast, meditation is structured regarding either one or both of the following: The self or an all-pervasive principle. Therefore, it is more in line with a participative pattern of spirituality and corresponds with pantheistic concepts of the spiritual reality and respective types of religious experiences.

The dimension of public practice refers to the social expectation that religious individuals belong to religious communities, which are manifested in the public participation in religious rituals and communal activities. The general intensity of this dimension can be measured easily by inquiring about the frequency with which somebody takes part in religious services or similar activities.

1.2.3. Centrality of Religiosity Index

Each core-dimension is represented in the various forms of the CRS by an equal number of indicators—either one, two, or three indicators, which results in the CRS-5, CRS-10, and CRS-15, respectively. This means that the five core-dimensions are equally weighted in the CRS index, which is calculated as the average score over all core-dimensions. The same principle applies to the interreligious versions of the CRS—the CRSi-7, CRSi-14, and CRSi-20 in which only the higher of two alternative indicators for one dimension is counted. The only two core-dimensions that have alternative indicators are experience, i.e., the interactive and participative pattern of experience, and private practice i.e., prayer and meditation. If, for example, both the frequency of prayer and the frequency of meditation are asked, only the higher value of both indicators is included in the calculation of the CRS index. Therefore, the two alternative indicators in the CRS only have the weight of one indicator. In this article, we only focus on the short forms: The CRS-5 and the CRSi-7. The seven items are (see also

Appendix A for a comprehensive translation of the CRS):

How often do you think about religious issues? (in CRS-5 and CRSi-7, core-dimension: Intellect).

To what extent do you believe that God or something divine exists? (in CRS-5 and CRSi-7, core-dimension: Ideology).

How often do you take part in religious services? (in CRS-5 and CRSi-7, core-dimension: Public practice).

How often do you pray? (in CRS-5 and CRSi-7, core-dimension: Private practice).

How often do you meditate? (only in CRSi-7, core-dimension: Private practice).

How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that God or something divine intervenes in your life? (in CRS-5 and CRSi-7, core-dimension: Experience).

How often do you experience situations in which you have the feeling that you are in one with all? (only in CRSi-7, core-dimension: Experience).

The measurement is based on a rating of Likert-scales. Two types of ratings are provided: Importance and frequency. Participants are asked to rate ideology in a range of “very much so (5)—quite a bit (4)—moderately (3)—not very much (2)—not at all (1)”, which is the only importance rating in the CRS-5 and CRSi-7 versions. The plainest subjective type of frequency rating is applied to the intellect and experience core-dimensions: “very often (5)—often (4)—occasionally (3)—rarely (2)—never (1)”. Public practice is assessed by an objective seven-point frequency scale: “several times a day—once a day (7)—more than once a week (6)—once a week (5)—one to three times a month (4)—a few times a year (3)—less often (2)—never (1)”. Finally, public practice is assessed by objective frequency in six answer options “more than once a week (6)—once a week (5)—one to three times a month (4)—a few times a year (3)—less often (2)—never (1)” (see

Appendix A,

Table A3 for details). After the assessment, the answers are recoded according to a calculation proposed by the author of the scale (

Huber and Huber 2012). Finally, all indicators of the CRS range between 1 and 5 with 1 being the minimum and 5 the maximum values.

The CRS index is a composite score based on the average of all items and ranges from 1 to 5. According to

Huber and Huber (

2012) three groups can be distinguished based on the CRS index—the “highly religious”, the “religious”, and the “non-religious”. If the CRS index is higher than 4.0, the respondent is categorized as “highly religious”. This means that she or he has a profound religious life. In this case, faith likely plays a central role in her or his life. If the CRS index is lower than 2.0, the respondent is categorized as “non-religious”. This means that she or he has almost no faith life. In such a case, it is very likely that religion does not matter to her or him at all or only has little influence. If the CRS index is between 2.0 and 4.0, the respondent is categorized as “religious”, which means that faith is lived sporadically. Religion is present and a part of that individual’s life but does not play a central role in life decisions.

1.3. Study Goals and Hypotheses

Before coming to the main goal, there are some notable byproducts to mention. The study should deliver norm values of every core-dimension in Russia and can be used as a reference for future investigations with the CRS in Russia. Besides the norm values, which are of statistical nature, the translated CRS items are provided in

Appendix A to facilitate a unified use of the CRS in Russian.

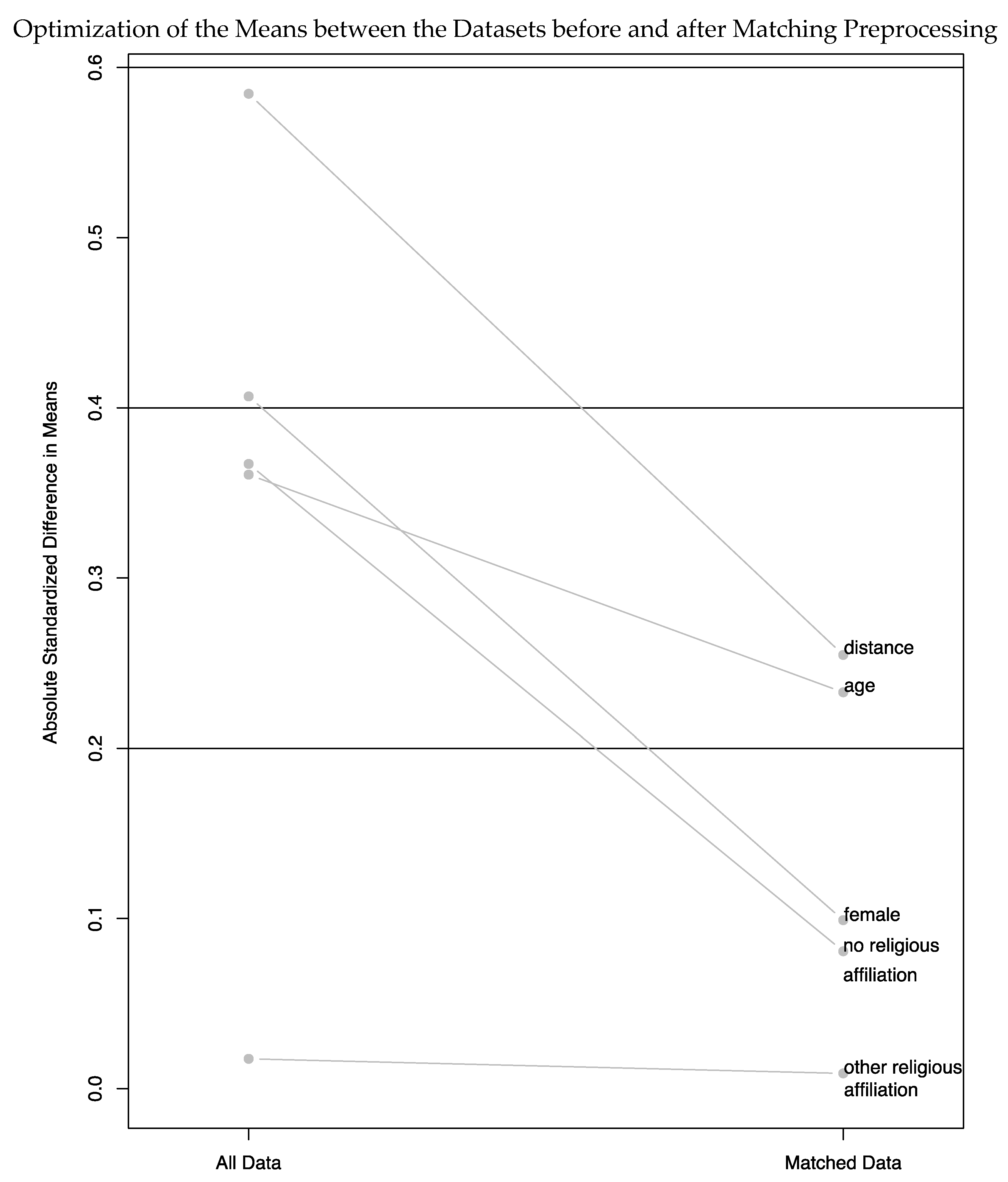

The main goal of this study is to test the statistical validity, consistency, and performance of the short forms of the CRS in Russia. The CRS is in itself a psychometrical measurement instrument that is based on the concept of the centrality of religiosity—a personality construct. Such constructs are said to be relatively stable over time in an individual. Technically spoken, we therefore expect that both short forms, the CRS-5 and the CRSi-7, have a time-invariance in measurement corroborated by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with one latent variable and five reflective indicators. The latent variable in the CFA statistically represents the concept of “centrality of religiosity” and is said to be relatively stable. Hence, stability is operationalized as configural invariance over time. Reliability analysis, on the other hand, refers to the consistency of the structural equation model. Moreover, starting with configural invariance we restrict the models and establish metric invariance. Regarding the mean structure in the CFA, no hypotheses are posed on its invariance between the two time points of assessment. This is done because the main interest lies in the consistency of the measurement and less in the changes in the centrality of religiosity in the population, which we describe but do not test statistically.

We expect the CRS-5 to perform better, in terms of having a better model fit than the CRSi-7 due to the mainly Orthodox samples, which are largely Christian and therefore Abrahamitic, making them more suitable for the dialogical formulation of the items incorporated by the CRS-5.

Considering the association of private and public practice in Orthodox church traditions we postulate a stable association between these two dimensions. This association is extra-factorial and therefore is captured by the residuals of the indicators of both practical dimensions. Such an association was already found in the mainly Orthodox samples from Georgia (

Ackert et al. 2020) and is to be corroborated in this investigation. This means, in addition to the main goal of the validation of the scale, that this study explores the potential of the CRS to capture the particularities of religious traditions with the example of Christian Orthodoxy in this article.