1. Introduction

My approach to dreaming and dream analysis is to contextualize the dream experience as being intrinsic to a larger metaphysical perspective. The intent is to analyze certain dreams as contributing to a human developmental paradigm, and to show how those dreams contribute to a complex theory of sentient ontology. I will start by making a few brief comments on the relationship of dreams to metatheory. While there are many different theories about dreams, from the metatheoretical perspective, none of them can be said to be definitive or comprehensive (

Barrett and McNamara 2012;

Bulkeley 2001;

Revonsuo 2010). I regard dream theories as being based primarily upon provisional hypotheses that are incapable of being fully provable. Furthermore, those hypotheses are often embedded in cultural attitudes and beliefs that reflect the zeitgeist or social context of the theorist’s formulation (

Hunt 1989). Subsequently, we have a wide variety of theories about dreams—their value, purpose, significance, or meaning—that spans an incredible range of perspectives, each offering interpretative information based in a variety of hypotheses, none of which are final or complete. For me, what this reflects is not the irrationality or inscrutability of dreams, but rather the complexity of dreaming and its inseparable association with human mental and emotional life. Dreams are inextricably intertwined with the psyche, body, mind, and spirit—none of which can be easily defined—and reflect our social, existential, and intersubjective relations. Dreaming expresses a profoundly complex phenomenon, subtle and transformative, that eludes reduction to any one theory, while also demonstrating the very limits of our theoretical attitudes. While there is a variable consensus on the physiological correlates of sleep to dreams, no theory resolves the issue of how dream contents correlate with biological indicators (

Bulkeley 2016). The distinctions between biological activity, the meaning’s context, and the existential impact of dreaming cannot be easily integrated.

Subsequently, the manifest significance of dreaming contents is by no means obvious nor encoded in immediately comprehended symbols, while sensory dream impressions are not strictly reducible to normative bodily states. Dream states are by no means mapped according to any paranormal science, except as provisional models of a wide spectrum of mental-emotional responses to often unrecognizable or highly theoretical causal sources (

Revonsuo 2010, pp. 237–39). The challenge of dream interpretation is based on this open horizon of meanings and causes, encountered through diverse theories, and is dependent upon some recognition of dream types. Not all dreams are of equal import or significance (

Jung 1974, p. 76); some are more meaningful and impactful than others, and not all dreams reflect similar states. In fact, it seems clear that dreams reflect an immersive capacity by which dreamers may access and subjectively experience, at times, highly altered states. If dreams are state-specific, as one theory postulates (

Hobson 2007), this does not mean that we have a complete map of what the full range of states implicated in terms of human developmental potential. Therefore, I want to explore a typology of dreaming contents, suggestively linked to variable states, in the formulation of a provisional theory that dreams are a basis for human psychic and spiritual development and, in higher dreaming types, dream states can provide metaphysical insights relevant to transpersonal theories that support higher domain perceptions. Put simply, the theory presented here implies that some dreams are a basis for the development of psychic and mystical states which can subsequently impact the dreamer and shift or reorient his or her worldview and value constructions. Dreams of this higher, more impactful type may be a basis for significant human development when those dreams are assimilated into new conscious attitudes and behaviors (

Kuiken et al. 2006).

This theory of a transformative dream typology developed out of my interest in dreams and dreaming over the last 50 years. As a vivid, transpersonal dreamer, I have kept a detailed dream journal throughout all those years, starting in my early twenties, and maintained to the present day. My motivation was to better understand the role of certain dreams as they related to my own developing philosophical interests. The basis for my recording of a dream is its transformative or transpersonal contents; in this sense, it is a dream journal of significant ontological encounters ranging from collective mythic types, through many diverse psi-active dreams, and replete with numerous mystical encounters manifested while sleeping (though some while awake). These encounters form the context for my reflections on dreams, which also motivated me to attain my PhD (Indiana University) in the religion and anthropology of dreaming among Native Americans (

Irwin 1992,

1994a,

1994b,

2001,

2002,

2008,

2012a,

2017), and later to publish various papers related to dreaming and mysticism (

Irwin 2011,

2015), as well as dreaming and paranormal phenomena (

Irwin 2012b,

2014,

2016). Over all these years, I have struggled to understand the purpose and value of dreaming in the context of being both a vivid dreamer and a scholar of comparative religions, with deep interests in parapsychology and transpersonal theory. I also add that, since the late 1960s, I have been a disciplined practitioner of sitting meditation, experimenting over the years with many types of mindful practice, but consistent in 30–40 min of sitting most days. While this practice has diminished somewhat in my later years (while other practices have increased), the overall impact is a sustained waking state of attentive, lucid awareness resulting from many years of practice. The following analysis is my current synthesis of these interests in relation to a general theory of dreaming types, wedded to an emergent ontological perspective and positively aligned with enactive transpersonal theory.

2. Metaphysics and Ontology

To understand dreams, and their various purposes, I find it necessary to consider the ontological and metaphysical implication of dreaming as a primary human activity. We all dream, we are all impacted by our dreams and, in the cyclical processes of sleep, memory is consolidated or cognitively integrated. In the dreaming cycle, a usual 90 min ultradian rhythm, NREM (Non-Rapid Eye Movement) is divided into three stages: a light sleep, followed by slower theta waves (50% of dreaming is in this state), and finally slow wave sleep (SWS, delta waves). SWS is followed by a return to the theta state, and is then followed by REM (Rapid Eye Movement), before returning to the light sleep state. The cycle then repeats throughout the night. Emotionally charged and complex memories are consolidated through REM sleep, and declarative memories, or easily verbalized memories, are better consolidated in NREM slow wave sleep (

Barrett and McNamara 2012, vol. 1, pp. 172–73; vol. 2, pp. 687–91). Currently, research in both the REM and NREM stages of sleep reveal varying types and degrees of dreaming activity, with REM dreams being the most easily accessible to the dreamer (

Barusš 2003). These observations illustrate that sleeping and dreaming are primal means for the cognitive integration of experience, revealing that variable forms of sleep mentation serve a functional purpose related to the health and wellbeing of the whole person. Thus, waking cognitive processes, consisting of OWSC (Ordinary Waking State Consciousness), which is more actively left-brain and non-imagistic, and DWCS (Differentiated Waking State Consciousness), which is more passively restful and imagistic, are additionally enhanced by integrative dreaming sleep to form a mental continuum, processed in cycles of day and night, that reflects the range and capacities of ‘consciousness’ across variable states (

Kokoszka and Wallace 2011;

Revonsuo 2010). Several more phenomenal distinctions can also be added to these basic delineations: the ‘flow’ of consciousness as a continual process, including self-reflection; and, ‘fringe’ consciousness as the ‘halo’ that surrounds mental images and thoughts, a penumbra of possible relational information conjunctive with, but peripheral to, conscious mental awareness. Fringe contents have a capacity to evoke possible future contents (like tip-of-the-tongue states) as well as retrospective awareness, enhancing the flow quality of the mind (

Barusš 2012;

James [1890] 1950;

Mangan 2007).

However, the larger question is the problematic issue of how one defines or understands ‘consciousness’ as a foundational basis for the arising of variable subjective mental and emotive states, dreaming or awake, with highly differentiated contents, which are not easily reducible to any causal physical theory (

Revonsuo 2010;

Tye 2007). For many reasons, I do not prefer the term ‘consciousness’ as an adequate lingual sign representing the lived-world of embodied human existence. While we may be ‘conscious’ in various forms with highly distinctive subjective contents, the nature of that awareness is not reducible, as I see it, to any neurophysiological explanation, even though neurophysiological correlates can be mapped to a wide range of variable states but not, however, to explicit contents (

Edelman and Tononi 2000). I regard waking and sleeping awareness as an ontological condition, with strong existential parameters linked to a specific lived-world, that is, to the embodied, enacted, and day-to-day context of the self-aware individual who, in part, reflects his or her specific socio-cultural location. The so-called ‘hard problem’ of closing the gap between consciousness and the brain (

Chalmers 1996) is a fictive construction based on a dualistic worldview that cannot reconcile the disparity between material causes and experiential subjective awareness. I call this ‘fictive’ because such a view presupposes, without proof, that there are only two primary aspects of human awareness, mind and/or body, a dualistic model. Currently, three primary mind–brain philosophical positions can be delineated: ‘naïve realism’, a belief in the direct perception of an external, objective reality (

Ross and Ward 1996); ‘representationalism’, the belief that the mind reconstructs the world of sensory data as mental phenomena, a primal form of dualism (

Revonsuo 2010, p. 190); and ‘enactivism’, a view that mind and world form a participatory, interdependent, unitary complex and there is, therefore, no incipient dualism (

Bogzaran and Deslauriers 2012;

Ellis and Newton 2005;

Ferrer 2017). This last, participatory view, my own favored position, is usually aligned with the metaphysics of integral panpsychism or panentheism. This is a metaphysics that emphasizes co-creative, emancipatory, and enactive ontological processes meditated by intersubjective relations developed within a unified cosmos of superabundant potential (

Brüntrup and Jaskolla 2017;

Cooper 2006;

Griffin 2014;

Kelly 2015c;

Mathews 2003;

Skrbina 2005,

2009).

While I do not position myself as a committed panpsychist, even though I have published on that topic (

Irwin 2016), I am sympathetic to a metaphysical view that supports a unitary, ontological basis for a healthy, a shared world inhabited by self-aware individuals. The enactive paradigm assumes that the interdependence of the world and self-with-others forms a dynamic wholeness or process symmetry that cannot be broken without disempowering the elements or entities that form that symmetry. The self cannot be taken out of the world without rupturing the coherence and value of the world, and the world cannot be taken out of the individual without the restrictive loss of identity. Mind and brain are not two realities but one interactive complex, reflecting mutually formed, multiple aspects of a single ontological ground (

Schooler 2002). In this sense, agency is central, defined by relatedness, interaction, and interdependent intentions realized through successful creative expressions, which are hopefully appreciated or valued by others. The existential criteria of authenticity include participation in meaningful, intersubjective relationships that further understanding, promote insight, and support alternative, ethically-constructed views. The plenum, or fullness, of this authenticity is the plenum of Being; it is found and expressed through genuine, meaningful relations, and is individuated through genetic predisposition, life experiences, agent-centered action, visionary perceptions, and caring concerns for others (

Globus 1987,

2009;

Irwin 1996;

Krippner 1994;

Laszlo 2014). The reason I am not a fully committed panpsychist (or panentheist) is because I regard the plenum or fullness that supports our interactive diversity as surpassing human comprehension, something much more than ‘consciousness’ (

Tononi 1998;

Schroll 2016). I understand that plenum as a mystery endowed with sacred presence, whose manifestations in human experience range across a wide spectrum of states, contents, and realizations, epitomized in various religious and spiritual traditions but by no means restricted to those traditions (

Ferrer 2002,

2017;

Kelly 2015b). However, a theory of a unitary, ontological matrix that supports such diversity cannot be adequately described as ‘presence’ while ranging from the most minute levels of subparticle operations, through various degrees of complexity, up to and beyond our most profound conceptions of the sacred human. There is something more than presence, energy, or ‘consciousness’ that best represents what it is that provides the unitary context and continuum that supports life and awareness in its many forms of body–mind relations. I call it spirit, sacred potential, mystery, and the fullness of Being.

A more fundamental attribute of a process-based metaphysics would be the ascription of an inherent ‘sentience’ to the most basic forms of nature, even in the subparticle domain (

Arp 2006). While this theory is speculative, it is supported by a long history of panpsychism as an alternate metaphysical view linked to the enactive paradigm noted above. By ‘inherent’, I signify a ‘potential for sentience’ that is increased and actualized through greater complexity, leading to enhanced sentient awareness (

Koch 2009): not mind or consciousness per se, but at the microlevel, simple forms of brute awareness. Independent particles forming atoms is a process of enhancement, an increase in sentience complexity for all of the particles involved; atoms forming molecules enhances sentience; molecules forming substance and mass, an increase in sentience, and so on up the scale of complexity to plants, animals, human beings and beyond. Increased complexity enhances sentience, bringing forth greater sentient qualities of awareness. In this process, self-awareness is an emergent property sustained by the appropriate degree of sentient complexity (

Goertzel 2017;

Hunt 2001, p. 36). In the same way that ‘wetness’ cannot be ascribed to molecules of hydrogen and oxygen that make up water, so too is ‘consciousness’ emergent from the lesser constituents that support its appearance (

Holland 2014). Sentience, then, is an indwelling potential awareness inherent to all existents, the actualization of which requires increasing complexity through interactive co-creative relations. This is an ontological process dynamic based on interactive polarities, including combination/desegregation, coherence/decoherence, and context/loss of context. Quarks are not sentient, but they contain the capacity for sentience, enhanced through increasingly complex interactions. As parts or particles ‘process’, or combine and decombine, they form complex structures through which sentience ‘emerges’, manifesting diverse properties unique to that process structure: structure does not create sentience, it only actualizes a preexistent capacity for greater sentient characteristics (

Meijer 2014). Devolution represents the loss of structure and a return to elemental existents capable of later recombinations; the process view is cyclical, nothing simply increases in complexity, but elemental forms must inevitably undergo decoherence and/or disbursement to participate in later enactive recombinations.

Thus, mind or conscious awareness, in the form of human complexity, does not go ‘all the way down’, but emerges from foundational sentient bits that are far simpler, and with no specific qualia that would later represent more complex forms of awareness (

Nagel 2012). Furthermore, developing complex structures may act with ‘determinative influences’ upon the subsets (parts) and constitutive elements that make up that complex structure, indicating an interactive co-creative, process-based, responsivity in development, a dynamic part–whole relatedness (

Peacocke 2014, p. 323). Sentience is interactive and dispersive, yet also coherent and responsive in forming intra-structural relations. Some authors have argued for a strictly emergent panpsychism from the most minute particle (

Hameroff and Penrose 2014;

Strawson 2006), but

Globus (

2009) theorized a ‘quantum thermofield perspective’ that recognizes qualia (qualities of lived experience) as ‘properties of the world’, which only emerge into phenomenal aspects of mind at the appropriate domain level of complexity. Sentience, then, might be described as a pre-conscious, elemental existence that—through cosmological and ontological processes—eventually reaches a level of phenomenal qualia expressing awareness, which—at later stages—attains specific self-awareness. Related ontologies have been theologized by both physicists and scholars of religion (

Davis and Gregersen 2014).

However, while I am giving only a simple, minimalist sketch of this ontology, the more profound question is how to qualify ‘sentience’ as an irreducible psychic quality capable of increasingly complex organization, which is infinitely variable and leads to fully developed human mentalities. In the least complex terms, I theorize that sentience is imbued with spiritual potential, reflecting a deeper metaphysical ground of Being which I characterized as Superconscious-Existence, or as a Super-Existent source, whose top-down ‘determinative influence’ promotes bottom-up, interdependent, or interactive, development (

Combs 2009, pp. 77–89;

Marshall 2014). I do not regard this influence as being teleological, directed toward some pre-intended Super-Existent goal, but rather as a mediating presence within (and beyond) the structural forms that represent real existents or actual embodied beings. The enactive paradigm requires choice and self-awareness as embodied intentions in living relationships with others and contextualized by local conditions, indicating an ability to choose among alternatives. This embodied condition implies relative free-will, a range of alternatives, bound in contextual circumstances, and open to creative discovery and innovative choices. The future is not predetermined, but open, conditional, and probable, based on intentions and relations with others.

I speculate that sentience increases awareness based on attention, effort, commitment, and positive, interactive relationships. Higher sentience is perfectly consistent with higher mind or higher dreaming in the context of overall ontological development. For me, it seems clear that sentient awareness is a provisional ground for moral improvement, leading in stages toward ever-more cooperative human relations (

Jones 2016, pp. 325–30). The Super-Existent ground imbues every particle and bit with sentient capacity, and the processes of sentient development corresponds to the basic scientific principles and laws of nature, which are themselves subject to change and ratification based on the degrees of embodied sentient awareness capable of formulating (of reformulating) those laws. In a living cosmos of sentient beings, in a vast universe of multiple domains and dimensions, what is possible for sentient beings depends not upon the abstract idea of ‘consciousness’, but rather upon the actual existential choices, intentions, and encounters we enact in order to evolve our awareness to greater understanding of the Super-Existent, Super-Abundant ground in and through all of our relations (

Mathews 2003, pp. 73–88). Sentience is the spark, self-awareness is the flame, and form is the changeable media that the fire transforms. The top-down aspect of this imagined ontology is based on bottom-up choices, an inherent potential whose developmental vectors, upon reaching varying degrees of self-conscious awareness, can result in the flourishing of latent potentials of sentience far beyond normative or ordinary states and contents of mind (

Barusš and Mossbridge 2017, pp. 179–84;

Miller 2012). Dreaming is one of the primary means by which the potentials of sentience become known and provisionally embodied in order to supplement enhanced self-aware, other-aware, existence. Dreaming, in this context, is a virtual actualization of sentient potential; attended to or not, this enactment offers unique forms of agency as possible expressions of Being. Dreams are sentient expressions of potential that is not yet fully actualized in real life choices; they reflect a latent capacity for greater self-awareness and contribute to our overall understanding of what is possible in terms of direct human experience.

3. Dreaming and ASC

In formulating a theory of a general dreaming typology, I want to first delineate the phenomenological domains relevant to states of mind. The mental continuum is complex, and the development of sentience as a dynamic ontological process includes not only OWSC (more actively left-brain and non-imagistic), DWCS (more passively restful and imagistic), fringe consciousness and flow, as well as the general sense of a reflexive self, but also three fundamental content domains: subliminal, normative, and hyperliminal. Considerable theory has been published on the subliminal concept (

Kelly et al. 2007,

2015), first articulated by Frederick W. H. Meyers as “all that takes place below the threshold or outside the ordinary margins of consciousness” (

Myers 1906, pp. 26–27). This domain of activity represents the underlying processes of mind and body—beyond fringe consciousness—that support normative awareness. For Meyers, ‘supraliminal’ represents all of the contents of the subliminal that cross the threshold into normative states of mind, where normative states include the full range of everyday experience. To this, I would add a third domain, the hyperliminal, representing the emergent properties of consciousness not already assimilated to the normative or subliminal domains. By analogy, ordinary consciousness—informed by the subliminal and hyperliminal contents is like a lake (really an ocean)—in which experiential psychic contents live within the depths (subliminal, as memories, impressions, and imprints), surfacing under various existential conditions (normative states), and yet there are also reflected on the surface of that lake, from the heights, other possible, subtle contents (hyperliminal) manifested in images, flashes, intuitions, vivid dreams, and various incipient, under-developed sentient capacities. In many ways, subliminal contents are more past-oriented (assimilated experience), while hyperliminal contents tend to be future oriented (emergent capacities not yet experienced or assimilated). Furthermore, a wide variety of ‘states’ can enhance receptivity to both subliminal and hyperliminal contents, thus ASC (Altered States of Consciousness) or, alternately, ASA (Altered States of Awareness) are often a basis for the manifestations of surprising, challenging, and sometimes disturbing psychic contents (

Alvarado 1998), clearly manifested in dreams. These manifestations are rarely literal, but are much more commonly symbolic, mythic, and metaphorical, as they image the condensations of psychic life (

Hunt 1989, pp. 56–66) and our actual lived-world relationships, both personally and collectively.

While sleep is an altered state with a complex set of cycles and variable conditions (

Hobson 2007) related to dreaming, dreams range across a wide spectrum of altered states, particularly in relationship to hyperliminal contents. Provisionally, states can be desegregated from contents, as there is little correlation between a measurable state and a specific content (

Granqvist et al. 2011). The following are notably represented by distinctive, altered states: day-dreaming, mindfulness, meditation, sleep, sleep mentation, hypnogogia, hypnopompia, sleep paralysis, false awakenings, lucid dreaming, hypnotic regression, trance mediumship, possession, psychometry, psychokinesis (PK), and, of course, dying. Alternatively, the following capacities are recognizable primarily by their contents: intuition, mythic personation, erotic dreams, nightmares, visitations or afterlife encounters (AE), telepathy, clairvoyance, clairaudience, precognition, retrocognition, dreaming together, OBE (Out of Body Experience), NDE (Near Death Experience), past life recall, and mystical visions (

Arcangel 2005). Of course, both states and contents are intimately related, but there is no real correlation that is determinative or even predictable of how they are related, except in the blunt sense that some states are measurable, by some means, though in other cases, there are no measurable aspects (AE, NDE). Subsequently, my interest lies in dreaming contents, whereby the impact of certain dream materials act to stimulate growth, development, and enhanced sentient awareness through experiential encounters forming new phenomenal patterns of perception (

Rock and Krippner 2011). Content-based dreaming can then be organized into heuristic categories as an overall template reflecting developmental trajectories without creating a necessary hierarchy of state-related conditions, or any determinative or causal relationships between states and contents.

The reason I want to desegregate states from contents is to give a more precise account of psi-dreaming as denoting a developmental stage fostering enhanced sentient awareness. Such contents no doubt have state-related (but not state-based) concomitants; however, I do not regard those states as causal, but rather as transmissive, by which I mean that a state may act more as an ontological transception (transmitting information) than as a source of awareness (

Grosso 2015). The information, via content, seems to utilize a variety of states to communicate contents relative to the psychic capacities of an individual dreamer (

Cardeña et al. 2015). In terms of psi-dreaming, as distinct from mythic or mystical dreaming, I distinguish two kinds of psi-perceptions either waking or sleeping: explicit-psi and implicit-psi, a distinction lacking in the research literature on dreaming (

Rock et al. 2013). By explicit-psi, I refer to psychic contents that predominantly match the primary set of features that define a given psi ability, where explicit refers to a more collective, feature driven psi account. Thus, telepathy as explicit is ‘mind-to-mind communication’, or precognition is a content relevant to future outcomes. However, by implicit-psi I refer to contents that reflect some features that relate to at least one psi capacity, possibly mixed with other psi perceptions, where implicit refers to experiential, individual contents that feature latent (possibly subliminal) psi capacities (

Palmer 2015). Implicit psi refers to a condition in which ‘psychic awareness’ is not in fact an expression of a categorical (explicit) ability, but an incipient perceptual content, a psychic tendency, a felt sense, noting intuitive information that is not necessarily categorized by explicit categories (

Carpenter 2012;

Nelson 2015b). In my experience, a great deal of psychic perception is a kind of ‘mixed media’ phenomenon, blending and weaving psi-perceptions into flashes of information not reducible to classic abilities or categories. I see these implicit intuitions as an ontological ground state for developing more explicit ability, and the dreaming context is rich in implicit psi without always manifesting as explicit ability, which is reminiscent of

Polanyi (

1962), who theorized that ‘tacit knowledge’ is implicit to all of our cognitive processes. This may have to do with the hyperliminal threshold, whereby explicit psychic information requires a more sustained state-based condition which otherwise appears as only momentary, implicit intuitions unsustained by fully developed psychic ability.

A third type of psi can also be noted, which I call transpersonal-psi: perceptions that reflect supranormative states, metacognitions, and/or mystical contents that tend to obviate explicit or implicit psi through ground-of-being perceptions, as a metaphysical opening to Super-Existent awareness (

Bogzaran and Deslauriers 2012;

Deslauriers 2013). Transpersonal-psi denotes a field of rich, meaningful contents which are often transverbal in nature, and are expressed through various operational, embodied modes of existential relations that reflect states of being unique to, and imbued with, qualities of the sacred, however that is defined in a local context. By operational or embodied modes, I refer to ‘saintly’ qualities of being, not simply an aura of holiness, but a direct felt sense of determinative influence whose impact on others suggests a Super-Existent source. The transpersonal quality, as embodied awareness, acts as a psychic influence that transmits to others a lived sense of intimate, interpersonal relatedness. Transpersonal-psi forms an interactive link with the hyperliminal domain, which is uniquely configured to the adept qualities of the percipient, and spontaneously transmits a sense of those experiential, Super-Existent qualities to receptive others. Dream events of interpersonal relations can reflect this type of transpersonal-psi. There is really no ceiling or boundary on transpersonal-psi, as it reflects the specific embodied capacities of individual visionaries in an expansive cosmos of unlimited, and unknown, potential. The transliminal state may abolish all boundary conditions for a full-blown unitary awareness. In a co-creative ontology of forth-coming, the evolution of sentience as an ontological primary, stimulated in dreams and enacted through embodied relationships, and has no closure in explicit-psi or in any enumerated mystical state (

Ferrer 2017). Dreaming contents are open to development in a creative, discovery-based process of increasing psychic enhancement informed by a unitary sense of metaphysical coherence developed through increasing complexity. Such a model meshes well with studies in Exceptional Human Experiences (EHE), where several hundred types of EHE experiences have been named, with mystical/unitive experiences rated by experients as being the “most profound and beneficial” of all types of EHE (

Braud 2012;

Palmer and Hastings 2013, p. 345).

4. An Ontological Model

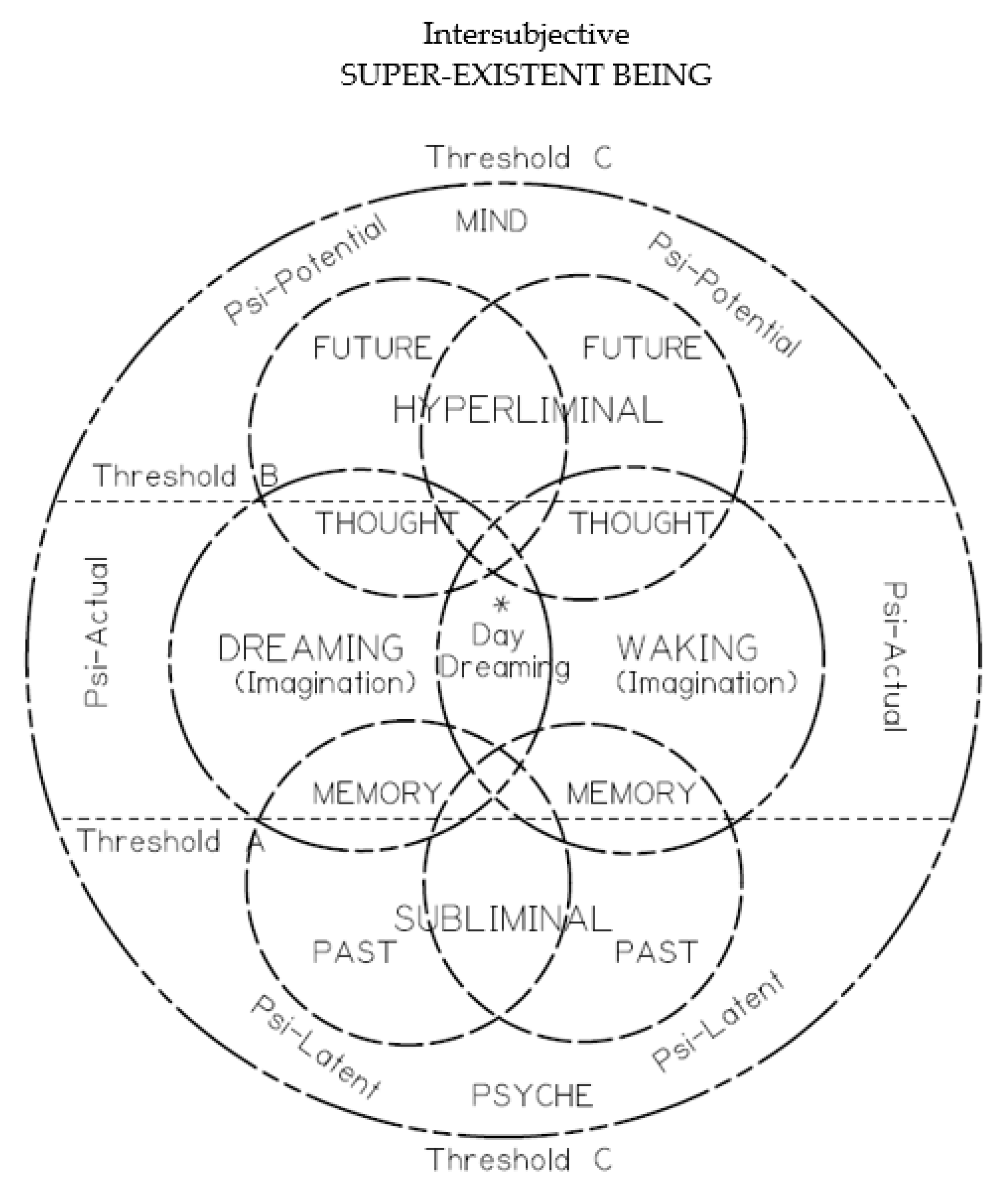

The model I am proposing represents a heuristic approach to dreaming as an intimate aspect of our daily life, co-related to waking, though variable in states and contents. The overlap between dreaming sleep and waking awareness is best expressed by the category of day-dreaming, or intensive imaginal activity manifesting subliminal and hyperliminal contents through a subtle ontological influence on both states and contents. The interpenetration of waking and dreaming domains reveals memories as being distinctive for waking (rationally and coherent) and for dreaming (transrational and syncretic), with thought also being distinctive in waking (logical, self-reflective, or imaginal) and in dream thought (creative, less self-aware, more imaginal). The following model is a brief theoretical summary of the basic concepts that are relevant to threshold awareness, and how dreams cross these variable thresholds and reveal latent sentient capacities. Three primary thresholds represent the domains of experiential awareness, linked to ASC: (1) subliminal contents as personal, familial, collective, and mythic; (2) hyperliminal contents as personal, emergent, imaginative, and experimental; and (3) the transliminal threshold of direct mystical, transpersonal encounters imbued with Super-Existent awareness. Each domain is enacted through dreaming modalities consistent with the contextual, lived world of the experient; thus, each is unique to the dreaming individual, even though shared themes and symbols may link diverse dreamers. In the hyperliminal domain, psi-(implicit or explicit) is represented as an ontological potential; in waking and dreaming states as psi-actual (when manifested), and in the subliminal domain as psi-latent, transmitted in mythic narratives, saintly stories, tales of marvel, miracles, and the spiritual belief systems of the experient. Dreaming is an activity that crosses the liminal thresholds which are dependent upon the state of the dreamer, offering creative representations of possible past, present, and future events (see

Figure 1).

The transpersonal domain of human awareness, beyond everyday mentality, represents the human embodied state as imbued with self-surpassing capacities that are not yet actualized, but are capable of possible development. The relationship between states and contents is permeable; waking and sleeping states represent points on a spectrum of awareness in which lucid dreams, mystical states, and psi-actual perceptions can permeate into the everyday condition. The psi-open domain beyond waking states reflects intuitions for tentative communication with others, (e.g., empathy, telepathy, or dreams of similar contents shared by more than one person) as either actual (consciously remembered: explicit) or latent (a felt sense with no specific memories: implicit). The subliminal domain may characterize more past oriented perceptions, symbolized through embedded archetypes or mythic forms of collective human experience, whereas the hyperliminal domain reflects creative discovery not fully actualized or embodied in collective forms, or emergent possibilities, and not actual types. The Super-Existent domain reflects a much vaster open horizon, a multidimensional, transphysical space (as in OBE and NDE) in which Being supports an enhanced human capacity for higher domain awareness (

Carr 2015;

Deslauriers 2013;

Jourdan 2011). Dreaming, which is beyond everyday dreaming, implies the crossing of a liminal threshold that allows the dreamer to participate in these various alternate domains through a virtual encounter, psi-enhanced interactions, and mythically-rich scenarios that offer provocative contents requiring self-reflection and conscious internalization. The relationship between the subliminal and the hyperliminal is heuristic, delineating a difference between assimilated (past) psychic material and emergent virtual (future) material which is not yet actualized but which, when actualized, then becomes subliminal, and potentially active in waking awareness.

The key to this model is the importance of ASCs as being fully operative in sleeping states. As a transpersonal and psychic dreamer, I can say that many of my most profound transformative encounters have occurred in dreams. Research on ASC surely applies to sleeping states as well as to waking states, and seems operative through the diverse aspects of normative sleep cycles. While research in ASC has expanded into many new areas, which are usually limited to waking states or to self-selected states, as found in meditation, ganzfeld, or with psychotropics (LSD etc.) or narratives of OBE and NDE, little is written about EHE states in dreams, because those states cannot normally be evoked by will or on demand (

Beischel et al. 2011). Thus the contents (with state descriptions) become the primary sources for the determination of the ontological value of a dream. Using the model outlined above, I conceptualize four primary areas of dreaming types, representing neither explicit content nor state-specific qualities, but rather more general features that are descriptive of a class of phenomenon in support of a theory of complex forms of sentience that are operative through and in such dreams.

5. Dream Typology

Can any assessment be made in terms of dreaming authenticity? Are all dreams necessarily authentic? Or are some dreams less authentic, and some more so? I tend to conceptualize dreams evaluatively as more or less authentic, referring to authenticity as a lived-sense of encounter and interaction, having a memorable existential impact. Impactful dreams matter more than those that simply rehash or replay everyday events with little or no remembered after-effects (

Domhoff 2001, p. 314;

Kuiken et al. 2006). One measure of such authenticity is the lingering impression, the dreaming imprint left psychically active when the dream ends; the more extreme forms of this type of dream are often referred to as a ‘big dream’ in the research literature (

Jung 1974, p. 76;

Bulkeley 2016;

Hartmann 2011, pp. 138–39;

Hurd 2015). However, while that category has been useful in general discussions of dream contents, my intent is to offer a more nuanced categorization to clarify the ontological significance of various dream types. Overall, ‘big’ dreams might be mapped to all types beyond ‘normative’ dreams—those ordinary dreams that leave only vague, not particularly meaningful, fleeting impressions. This does not mean to imply that normative dreaming is not valuable or therapeutically significant—it can be incredibly valuable for the assessment of everyday concerns and struggles. Generally, I see the dream as a virtual psychic creation (linked to variable states) manifesting enactive examples of possible embodied awareness (

Deslauriers 2013, p. 515;

Hobson 2015) and as a relatively creative activity engaging somatic, emotive, cognitive, and intuitive capacities. In the more normative context, the dream-ego is primarily self-referential, noetic, and self-validating, or the obvious dream identity called ‘myself’, as a creative dreaming agent (

Strawson 2014). The following four typological categories are consistent with my own dreaming, and with dream types in the general research literature: normative-rational; mythic-imaginative; psychic-intuitive; and mystical-ontological.

5.1. Normative-Rational Dreaming

This type refers to the integration of three constructive vectors: first, the pre-dream condition of the dreamer, in terms of conscious thoughts, wishes, feelings, ideations, values, social context, intentions and intuitions. Second is the dream content proper, which is dynamic and cross-modal, incorporating kinesthetic-somatic aspects, lingual expressions (thoughts, words, phrases, communication), and imagistic-visual scenes (metaphorical, polyvalent, emblematic, spatial or geometric forms), in varying degrees of representation (

Hunt 1995). Third, there is a psychological context that is usually personal, diffuse, and intrinsic (behind the scene), with felt significations or meanings, including unstated or unseen influences that reflect everyday life and relationships. Because such dreams reflect polysemy and multiplicity, they have no single interpretation (

Hunt 1989, pp. 208–10), as mental life acts to create complex synesthesia, and frequently manifests through metaphors by framing one situation as a medium for understanding a second situation. As Hunt notes (

Hunt 1989, p. 215), dreams are what Wittgenstein called “seeing as”, where the dream acts to creatively display instant metaphorical comparisons. Understanding those metaphors and their creative import is a post-dream work that seeks to reconcile daily waking life with sleeping dream life, in all its up and downs, surfaces and depths (

Hartmann 2011, pp. 49–59).

The reference to the ‘rational’ signifies that the content of the dream is recognizable to the dreamer in terms of his or her ordinary, daily life. I do not mean to imply that the dream is necessarily logical, but rather that the continuity between the lived-world and the dream-world, however creatively envisioned, ‘makes sense’ alongside normal life. Ontologically, this continuity suggests that both positive life experience, and the disturbing impact of turbulence and upheavals of daily life, undergo virtual processing in dreaming. This sentient processing need not be ‘conscious’ to the dreamer for functional utility, and when such dreaming is remembered, it demonstrates a rationally identifiable relationship with past waking experience. This normative type of dream implies meaningfulness, theoretically uncovered in all of the conventions of standard dream interpretations, allowing for a wide array of therapeutic outcomes. In a very rough sense, I speculate that 80–90% of dreaming is this type, functionally facilitating memory consolidation, supporting the continuity theory between waking and dreaming, and arising from the need for the resolution of everyday concerns, worries, ideals, and relationships, positive or negative (

Domhoff 2001).

Here is an example of this type of dreaming, taken from my dream journal (October 2015):

I am sitting at a table, with a white tablecloth, on a wooden chair. Other are also at the table of varying age and gender. I am in a normal state of mind but then, there is a flow or mild upsurge of awareness, an enhancement of perception. Then I bow my head and say, “Al’asmaa al’salaam” (Divine Names of Peace). This is a mantra for meditation and for greeting others. As soon as I say this, a young woman at the table also repeats it with some sense of not knowing what it means but believing that it is good, a blessing. When I raise my head, I am aware that a new possibility has entered my life, to form an organization based on peace, wisdom, and mystical teachings. As I am pondering this call, Pir Zia appears next to me and reaches out his hand and touches the left cheek of my face with his right hand. He congratulates me on attaining a new station and gives me his blessing kindly with full support. He wishes me well and I take his hand and kiss the back of it (as a traditional expression of thanks). This action creates “affinity” between his organization (Inayati Order, linked to the Seven Pillars House of Wisdom) and this possible organization forming in my mind.

This dream reflects conscious thought and possible aspirations in terms of already-existing relationships, as I was elected to be a guiding voice with the Seven Pillars House of Wisdom, and—as a friend of Pir Zia (the leader of the Inayati order)—I have great respect for his work and dedication as an American Sufi teacher. The metaphorical content is noted in the idea of forming an organization dedicated to wisdom and peace as an expression of inner aspiration to assist others to pursue spiritual life in concert with those dedicated to similar principles. The work is to form relationships that support shared attitudes toward peace and wisdom. The prayer is unique and expresses—in a condensed, alternate (sacred) language context—the compression of a mental aspiration to a meditative phrase that is meant to stimulate the remembrance of the core desire. The Arabic represents a metaphoric translingual gesture, that the phrase content is not reducible to a memetic of known contents, but rather invokes an opening to an emergent horizon of blessing that is irreducible to its lingual sign. Mutual support appears both in terms of those interested in learning, with some emphasis on the feminine, and those qualified to give support as teachers. The flow state reflects the actual experience of attunement or coordination with states that facilitate connection, and a mild participatory engagement with deeper Being. All of this is known, and yet it is symbolized through subliminal attitudes and ideals, as expressed in dreaming. The dream reflects an enhancement of sentience as moving into a greater organizational commitment to a lifepath illustrated virtually as a potential path of development (an alternate future becoming).

5.2. Mythic-Imaginal Dreaming

I hypothesize that about 5–7% of dreaming invokes more memorable, vivid archetypal dreams, mythically constructed, in either positive or negative scenarios, along a vector ranging from nightmares to more positive encounters with figures who often reflect the spiritual or belief worlds (including fictive tales) of the dreamer. In turn, this brings forward the role of the imagination in the context of dreaming (and waking) as a pluripotent psychic ability to envision, visualize, or construct virtual images, actions, interactions, and personations (a mental view of some ‘other’ as a person), and indeed, entire scenes and world pictures. Imagination as a cross-modal phenomena incorporates both imagery and language—words, talk, and exchanges between dream characters—often in a global scene that gives context to the interaction (

Miller 2008;

Kind 2018). Such dreams reflect archetypal themes or mythopoetic images “associated with numinous-uncanny emotion that goes beyond all prior waking experience” (

Hunt 1989, p. 64). In these dreams, the creative-constructive imagination seems to tap collective imagery, persons, or situations charged with strong emotional contents, recontextualizing dream scenes into a more mythic scenario depicting a wide range of culturally-defined archetypes of human experience. Often organized around a central image, laden with strong feelings, this internal image leaves a powerful imprint in the memory, at times, as an unforgettable dream experience (

Hartmann 2011, pp. 23–29;

Miller 2008). The central ‘idea-image’ of the dream synthesizes and challenges mundane associations and presents a new context, encouraging possible ontological insight. The image-idea calls the dreamer out of the ordinary and into the mythic in order to reveal dialectic tensions between individual and collective patterns of development (

Krippner et al. 2002, p. 158). Typical to such dreams are magical or heroic circumstances, or—in nightmares—more fearful, demonic, and violent personations. Other scenes may present joyful, angelic, spirit-beings, talking animals, tricksters, or clown figures. Titanic dream imagery may include powerful kinesthetic sensations, pain, fear, terror, ecstasy, crisis, dismemberment, falling, paralysis, suffocation and other forms of somatic intensification, tears, shaking, nervous flows of energy, and radical self-states of a non-ordinary kind (

Hunt 1989, pp. 132–39).

The metaphorical nature of such dreams often has a predictive value (

Mageo 2003, pp. 10–11); they often indicate symbolically a developmental trajectory, sometimes conjunctive with mythically-shaped scenes or interactions. While the imagery in mythic dreams may seem to reflect the subliminal past, such imagery simultaneously indicates a present condition of the dreamer and suggests how that situation reflects the human condition as lived-through by other generations. Positively, such dreams may suggest developmental circumstances, clad in mythic forms, actions, or imagery, linked to collective struggles, transformations, or recurrent themes that require individual attention and valuation. There is a shift in such dreams toward collective issues, or at least collective influences, formulated as changes in old mythology for new or emergent mythology (

Paris 2008). Feinstein and Krippner (

Feinstein and Krippner [1988] 2008) wrote on the relevance of mythic dreams for the formation and reformation of a ‘personal mythology’ as being intrinsic to the dreaming process—knowing one’s story and revising that story based on dreaming experience (

Krippner et al. 2002, pp. 157–67). Mythic discourses (

Irwin 1994a,

1994b, pp. 185–210) may be understood not as an interpretation of a dream text per se, but also as an enactment, even a ritualizing, of dream contents brought into relationship with a lived-world, where such an enactment is transformative, empowering, and supports new existential patterns (

Paris 2008). For example, creating a ritual expression based on the dream experience, using various objects, movements, artistic creations, and enacted events, to represent the dream’s contents (

Feinstein and Krippner [1988] 2008, pp. 165–75).

Ontologically, mythic dreams place the dreamer into a dialogical context with collective attitudes or beliefs, in a confrontation with the turbulence of subliminal collective influences. Through the creative capacities of mythopoetic, imagistic intelligence (

Hunt 1989, p. 188;

Kelly 2015a, p. 36), mythic dreams place the dreamer, as a responsive agent, into a virtual context that personalizes the collective influence. This is shared intersubjective sentience, a manifestation of collective tensions and concerns that penetrate into personal life, stimulating the assessment or possible reassessment of current attitudes or beliefs. Issues of race, ethnicity, gender, social aggression, paternalism, sexism, political attitudes, global disaster, war, oppression, conflict, terror, poverty, discrimination, and all of the detritus of collective miasma may cross the subliminal threshold to challenge the values and beliefs of the dreamer. Otherwise, such dreams may act to instill inspiration and creative response, new insights, discoveries, or the resolution of difficult situations, as another link in a chain of internal dreams expressing developmental themes. One primary significance of mythic-imaginal dreaming is the story, often incomplete and partial, that requires integration into the life of the dreamer; the fictive element—as an expression of imagistic intelligence—reveals dreams as creative constructions, and as a deepening response to social and cultural narratives that inhibit or repress human development (

Hunt 1989, pp. 174–79;

Krippner et al. 2002, pp. 24–31). This suggests an ontological feature, that creative archetypal dreaming arises from a felt sense of a better way, a more mature (complex) response, an inner urge for self-surpassing insights as an ontological provocation, leading to a more enhanced, enactive way of being. The story, as a mythic construction, reveals characters, scenes, and interactions that give an imaginal, narrative presentation centered on key images that carry powerful personal and collective aspects. The interpretive work is to understand how an individual life relates to collective narratives.

One example of this type of dream is the following, from my dream journal (2016), reflecting mythic symbolism and altered states:

The dream starts vaguely in a place that has been a sacred site for many generations, represented by a large statue of a god, seated on a conventional throne, reminiscent of the stone work of Abu Simbel (Ramses II) in upper Egypt. However, the setting is dark and the stone is black and seems worn and very old. The god does not seem conscious in the statuary, there is a deep silence, and the statue seems to be in a building or underground setting that is vague and ill-defined. There are other persons present and we are tasked with the dismantling of the statue. At first there is a general resistance to the idea but I accept the task and together, we slowly dismantle the stone work of the image. The task is difficult but as the dismantling proceeds, it becomes easier until, the image is entirely removed and the god no longer exists. The general feeling is that this was a necessary and required task that was initiated by supramental guidance; there was a felt spiritual influence at work, pressing for the dismantlement of the gods. I am responsive to this influence (along with others) and feel that images are no longer representative of the “god-truth” that they claim to represent.

Then, the scene changes to another temple complex, this one even older, with a god-image made of earth, not stone. The feeling is one of a more ancient, earth-based religion, an ancient indigenous image, one of many leading from earth, to clay, to stone and metal. The task is the same: to dismantle the image. This time, the image is quickly dissolved; it seems to collapse, and even the earth that composed the image is gone. However, something else is revealed. There is the outline of the top of a large hidden chamber, level with the surface of the earth, buried in the ground that underlay the image of the god. A voice says that this is the ‘oracle chamber’—very, very ancient, active before the rising of the popular gods. Then, the dream shifts into a multidimensional context, which is difficult to describe, rich with subtle psychic perceptions and feelings. The feeling of the dismantled second god was neutral, a necessary task which was accomplished with relative ease, clearing the way for greater revelation and insight.

This dream clearly reflects collective issues, the overturning of old order thinking and more archaic religious symbolism, but it is a dream that is also filled with a sense of awe and mystery. The dream also illustrates the collective work of many different people of different ages and ethnicities (the people of the dream were diverse), and suggests the need of the individual to confront and turn over the old imagery and beliefs wedded to that imagery. The narrative is positive, in that the image is dismantled successfully, revealing an even older earth-based ideation, which is also dissolved by collective efforts. Even so, the dismantling does not diminish the numinous sacred which then appears in the form of a unique psychic capacity—an implicit precognitive-clairvoyant perception that might be developed into a more explicit oracular or precognitive ability. The dream suggests the mythic, collective, archetypal nature of religious belief, and the need for a deconstruction that makes the dreamer a responsible agent in that process of leveling and discovering some deeper truth hidden beyond form. The sentient aspect reveals a creative process of developmental stages in religious belief as moving away from image-based ontologies to more refined and less anthropomorphic theories of god-based religions. It also shows the deconstructive aspects of development that require a dismantling of older forms for the emergence of newer ones, as sentient process dynamics leading to innovation and less dependence upon old-order thinking.

5.3. Psychic-Intuitive Dreaming

This type of dreaming is based far less on the narrative structure of the dream, and more on manifest activities of psychic abilities that are usually not operative in waking life. Research in this area begins notably with Ullman, Krippner, and Vaughan in their study of dream telepathy at the Maimonides Dream ESP laboratory from 1962–78 (

Ullman et al. [1970] 1989). Later research on dream telepathy “clearly produced overall effect sizes well above chance expectation”, though not as high as those found in the Maimonides study (

Baptista et al. 2015, p. 211; see also

Watt 2014). From that time to the present, psi-dreaming has been noted in paranormal research, though it is basically limited to narrative accounts by psi-dreamers, with the greatest emphasis on lucid dreaming. In my own dreams, I have experienced explicit-psi (telepathy, precognition, clairvoyance, past-life, and OBE); implicit-psi (dreaming together, lucid dreams, visitations (AE), and psychokinesis); and transpersonal psi (mystical, unitary, and transcendent encounters). I estimate about 3–5% of dreaming has at least implicit psi aspects, though based on the psychic development of some individuals, this percentage might be far higher, especially in those with operative, explicit-psi ability. There is also some evidence that women are more frequent psi-dreamers than men (

Xiong 2010, pp. 280–81).

Krippner et al. (

2002) wrote a major work on the topic of ‘extraordinary dreams’, offering detailed chapters on the following types of psi-phenomenon dreams: lucid, OBE, healing, dreaming together, telepathy, clairvoyance, precognitive, past-life, visitation (AE), and spiritual dreams.

Xiong (

2010) gives a brief overview of dreams and psi perceptions;

Tart (

1978) noted that, in operative psi dreams, the target of perception may take symbolic forms, and may not appear in a literal sense, problematizing the evaluation of implicit psi functioning in dreams. Research on intuition has described it as a non-analytic process, similar to insight in many ways, producing an overabundance of potential meanings that must be sorted and integrated through conscious effort and reasonable reflection. Intuition is a starting point for more mature deliberation on possible meanings (

Hogarth 2010;

Sinclair 2011;

Zander et al. 2016).

In the language of paranormal research, psi-related contents are designated as ‘anomalous’, indicating the view that psi is not a normative feature of waking or dreaming life, more the exception than the norm. However, implicit psi may be far more common in everyday life, for example, as intuitions, hunches, coincidences, a felt-sense, strong empathy, or other subtle cognitions (

Palmer 2015). Such implicit perceptions, in a hyperliminal or intuitive sense, may convey subtle information picked up across the hyperliminal threshold, indicating an operative capacity that is emergent and not yet explicit. As in waking life, so in dream life. The core of psi perception is ‘information’ and, as such, is perhaps more accessible in dreams, because there is little physical input and greater opportunity for internalized perceptions across a spectrum of awareness, including enhanced ‘emotional intelligence’ based on human relationships. Powerful images, such as those found in mythic dreams, may act as ‘attractors’, pulling psi-information into the dream context (

Krippner et al. 2002, p. 166). The dream then becomes an interior theater for the exercise of psi-capacities in virtual form; this exercise becomes a corollary to waking psi, crossing the hyperliminal threshold in unexpected moments of anomalous perception. If so, then as an ontological claim, it implies that purposeful being, interlinked through networks of human relationships, can stimulate psychic development through dreams, which are particularly evident in fringe consciousness. Intuition in this psychic sense is a spontaneous perception of information though non-sensory means, waking or dreaming.

Lucid dreaming has received considerable attention in parapsychology as a unique form of cognitive attention in dreams, demonstrating a fusion of waking and dreaming conditions (

Hurd and Bulkeley 2014;

Waggoner 2009;

Krippner et al. 2002;

Auerbach 2017;

Godwin 1994;

Hunt 1989;

LeBerge 1985). The lucid dreaming condition is when a dreamer recognizes that he or she is dreaming, and—while dreaming—the subject has variable degrees of self-awareness and some ability to make choices as though they were awake. Such dreaming has been described as a form of metacognition (

Hurd and Bulkeley 2014, pp. xxii–xxiii), meaning that the dreamer reflects on dreaming while in the dream, and can frame the on-going dream experience in a variety of ways, informed by cognitive activities such as choice, reasoning, evaluation, self-selected intention, relational interactions, and so on (

Kahn 2001). Having published a paper on lucid dreaming, with multiple examples of the lucid state (

Irwin 2014), I will note here that I place lucid dreaming into the category of implicit psi because, somewhat ironically, the mental state of being lucid is almost identical, in my experience, with being awake without psi. While the implication is one in which a unique state of awareness in linked to the dreaming content, the primary capacity to shape the dream scenario is somewhat like shaping a fictive story, or at least influencing how the story plays out. Is that psi? What fascinates researchers is the cognitive state of reflexive self-awareness in a dreaming context, a conscious intent, thereby demonstrating that some dreams manifest waking cognitive abilities. However, in terms of psi-dreaming, lucid dreaming appears to be only a moderate expression of psi-actual, or psi-explicit ability. In fact, lucid dreaming might best be described as waking self-reflection, through which conscious choice acts as a determinative to dreaming outcomes. That is not psi, but rather is much more a recognizable form of conscious choice guiding an imaginative action, perhaps similar to day-dreaming. Lucid dreaming can be described as a form of normative cognitive process occurring in a sleeping state. The very idea of ‘lucid’ suggests a waking cognitive process, decision making, and intentional direction to action, all of which are normative for wakefulness.

Often linked to lucid dreaming are out-of-body experiences (OBE), which—in the dreaming context—I associate with the ‘flying dreams’ or ‘soul travel’ so typically found in shamanic literature (

Krippner et al. 2002). In turn, this ability evokes another issue that is fundamental to paranormal research: the subtle body (or astral body), a phenomenal psychic identity capable of separating from the physical body and traveling in a variety of hyperliminal domains, often shaped by cultural belief patterns (

Braude 2003;

Samuel and Johnston 2013). The close tie between lucid dreaming and subtle body dreams is based on the state of lucidity brought to the flying dream. What differentiates them is the sense in OBE of being not in a dream per se, but rather exploring a specific hyperliminal domain linked to the physical world. The extensive literature on the ‘soul’ or ‘soul vehicle’ gives ample testimony to the widespread participatory experiences of OBE in the waking state (

Irwin 2017a). In dreaming, flying dreams may well indicate a psychic capacity to engage the subtle body as a form of EHE. From an ontological perspective, (lucid) flying dreams may be a form of psychic enactment of implicit cognitive ability, expressing self-awareness in a hyperliminal domain more easily accomplished in a sleeping state, and also indicating a possible waking capacity.

The literature on OBE is also strongly linked to near-death experiences (NDE), which also indicate a capacity for full cognitive awareness and intentional actions while the physical body is evaluated as clinically dead (

Carter 2010;

Irwin 2015). Evidence has been gathered that demonstrates enhanced cognitive function during NDE (

Greyson 1999;

Holden et al. 2009). It might be assumed that NDE is not a characteristic of dreaming; however, dreamers do in fact dream about dying and of having afterlife experiences. The most common afterlife encounter (AE) is a dream in which a person who has died interacts with a dreamer and gives veridical information sometimes unknown to that dreamer (

Arcangel 2005). Such information reflects not only psi-capacity, but opens the question of ‘survival’ as a metaphysical condition which enables dreamers and post-mortem others to communicate through dreams. From the ontological perspective, death can be characterized as a transition from the physical state to a hyperliminal state in which cognitive capacities are active and enable dreaming contact with the subtle, transphysical world (

Carter 2012;

Cattoi and Moreman 2015;

Ryan 2006;

Moore 2017). From a developmental perspective, contact with the post-mortem (and other entities, such as ‘beings of light’) through dreaming opens the hyperliminal horizon and instigates a lived-sense of a broader, more complex, multidimensional cosmos (

Barusš and Mossbridge 2017;

Ring 2006). Furthermore, contact suggests a form of dream mediumship, and therefore indicates telepathy as a means through which such communication occurs. Therefore, dreams of the dead may well indicate latent psychic ability, in several ways, as being possible through visual, auditory, or some other sense capacity. Survival theory has tended to polarize, with the alternative theory of ‘super-psi’ (or super-ESP) being defined as an ability to pick up information about the deceased through reading the minds of some other living person, perhaps taking the form of creative intersubjective dreaming (

Braude 2003). However, even in this case, such dreaming suggests an awakened psi-ability in the dreamer, a capacity to obtain psi-based information, and to do so through subtle intersubjective relations.

Other dreaming capacities related to psi-dreaming, even in the implicit sense, include dreams of (oracular) future or past events (precognition or retrocognition); dreaming a past life scenario that is vividly situated in specific cultural context; dreams of events that happen in distant places (clairvoyance); dreaming together in such a way that the dreams of two different people overlap or are compatible in an extraordinary sense; healing dreams that seem to transmit unique energy or psychic influence for the benefit of others; ritual empowerment dreams based in non-ordinary states that convey contact with spirit powers; encounter dreams with powerful figures that instill a felt sense of new powers of perception (initiatic); dreams of knowledge in which insight is propelled to new levels of understanding; a participant sense of communal activity linking dreamers across a vaster network with other dreamers; dreams of radical social transformation; and a sense of deep earth changes, linked to the fate of humanity (

Bogzaran and Deslauriers 2012;

Globus 1987;

Krippner et al. 2002). Many other types could be added to this general list. These dreams share a lived-sense of ontological import that the dreamer is entering a liminal state, crossing the hyperliminal threshold, and engaging altered psi-based awareness rich with information. Simultaneously, such dreams also act as a virtual stimulus for the further development of psychic perceptions, as an ontological evocation for the possible exercise of those perceptions in waking life (

Barusš 2012).

This type of dream can be illustrated by the following example, the second part of the 2016 dream recorded earlier in the mythic section of this paper. The dream is divided because the dream journal entries are very long and complex, this being one of the shorter narratives overall. Having seen the oracle chamber hidden below the dismantled earth god, the dream continues:

The scene shifts to the multidimensional view, I seem to be hovering over the oracle chamber which is still active and filled with very subtle energies. There is also a lake, the water is calm and dark, almost like an obsidian mirror, somehow the earth and the water together with air (where I am hovering), make up a multidimensional context in which other beings or entities are present. I have no direct sense of my physical body, but only of my head. Then I sense a very powerful female being approach from behind me. She places her hands on the opposite sides of my head from behind, I can feel her hands in a very tactile way and sense a subtle energy flowing from them into my mental state. At first the feeling is very, very subtle, hardly knowable. There is a ritual in process, one that I do not understand but in which I am a participant. There are other non-physical beings present working with the feminine spirit, they are sharing thoughts and creating a focal matrix charged with subtle energies. There is a background narrative which I do not fully remember on the value and importance of the oracle tradition. There is a question—would I embrace the oracle tradition in a contemporary context, be a spokesperson for the precognitive forthcoming of events and happenings directed to human development?

At first, I am resistant to the idea of oracular knowledge, somewhat unsure of my ability to actualize and hold such knowledge, particularly after the dissolution of the conventional gods. But emotion is welling up within me, feelings that are strong and heart-centered, not intellective, but rather more soulful and deeply-felt. As these feelings increase, the flow of energy in the feminine hands on each side of my head increases, effecting an even deeper emotive response. I can hear her voice; she is like a priestess or oracle herself, and she says to the others with her, “He is beginning to respond, it is working.” As the energy increases, I sense other dimensions opening around me, very subtle, but reflecting a spiritual complexity that is far more profound than the earlier, less developed popular god ideas. These dimensions or domains are part of a vast complex of inter-related beings of very diverse natures: some physical, some transphysical, and some meta-spiritual (beyond our current ideas of spirituality).

This dream demonstrates shifting states of consciousness, moving away from the ordinary to the non-ordinary, to more expansive perceptions that take on multidimensional characteristics. The feminine presence also indicates a collective shift to a less masculine type of perception, more global, intersubjective, and transpersonal, as well as precognitive. While there is no explicit OBE, there is a lucid sense of awareness, a feeling of floating or of being suspended in the air, with an increase in the perceptual capacities that reflect contact with possible transphysical beings whose intentions are symbolized by cooperative, interactive support, in a somewhat ritualized context. This is a clearly psi-implicit dream forecasting possible cognitive development toward a more explicit pre-cognitive and clairvoyant (oracular) ability. There is also a sense of awe and reverence, the emotional impact of which is an opening of horizons beyond any local religious construction, a transpersonal sense of something greater, more challenging, and yet instrumental in facilitating human growth and development. The dream also illustrates how the mythic and the psychic can be conjoined into a single dream experience. From the pan-sentient point of view, these dreams demonstrate a sentient ground of being, the operative modes of which are psychic and intersubjective. The movement beyond myth requires the abandonment of old images for the formation of a more complex, vastly-shared sentient cosmos in which dreaming is a means for fostering certain states that lead to an enhanced human sense of participation in a multidimensional cosmos of increased, if latent, psychic capacities. Here, sentient capacities virtually manifest enhanced psi-activity as being relative to a more complex, transphysical reality that is nevertheless agent-centered and intersubjective.

5.4. Mystical-Ontological Dreaming

I estimate that only about 1–2% of dreams are of this type. Such dreaming involves a participatory, Super-Existent encounter, an ontological affirmation of a greater reality, the nature and influences of which result in a self-surpassing knowing, a direct experiential form of transpersonal absorption. These are dreams of the most profound ontological type, a form of supernal dreaming of which the contents tend to be transphysical and transpsychic, deriving not only from the body or from the psyche of the individual, but also being shaped by an ontological ground, the very source of sentience and becoming (

Donnell 2008;

Lancaster 2011;

Marshall 2015;

Strickling 2007). Such dreams are usually profoundly transformative in effect, unforgettable in impact, and charged with super-luminous energies that are not reducible to any material or psychic cause. As Super-Existent potential manifests an infinite capacity for enacted embodied knowing, there is no specific form for such dreams, though experiences of supernal light are common, as often noted in deep NDE (

Atwater 2007, pp. 319–30;

Fox 2016;

Puhle 2014;

Kapstein 2004;

Ring 2006, pp. 273–83). Ontologically, supernal dreams give rise to multiple expressions, theories, and teachings that are capable of further creative enacted elaborations, corrections, revisions, and/or new discoveries. Every aspect of human knowing and agency—including interactions with other species—expresses a possible trajectory for further development in a sentient cosmos of creative becoming. The unitary basis of the Super-Existent potential represents a ‘divine ground’ as an ontological process-based matrix in which human agents, communities, and nation-states share a common metaphysical source for the enactment of diverse cognitive capacities, intentional concerns, and moral-ethical values (

Geels 2011). This ground is knowable and experiential, is irreducible to simple material origins, and is most easily accessed through supernal dreaming with transpersonal ASC, often preceded by—but not reducible to—psi-intuitive phenomena, sometime taking mythic and imaginal forms.

If mystical or transpersonal knowing is based on experiential encounters with a Super-Existent ground that is ontologically distinct from, but fully in support of, human life, then the transpersonal nature of the encounter may not be measurable in any bodily or neurological sense, or only minimally so, as the knowing discovered in such an encounter may occur primarily in and through a transphysical dimension. To put it simply, the mystical encounter may occur in a hyperdimensional context that leaves no significant physical trace. This hypothesis is reinforced by NDE, where the body is clinically dead but the ‘person’ is fully aware, in an altered condition, and joyfully in direct contact with Super-Existent agents or qualities (Light), leaving no trace whatsoever on, or in, the physical body (

Irwin 2017b, pp. 361–77;

Beauregard 2011, pp. 75–77;

Sabom 1998). Genuinely mystical or supernal dreams, beyond mythic and psychic dreaming, reflect a deep human capacity for acknowledging, in a direct participatory manner, the sacred ground of shared species becoming. This direct knowing opens a horizon on a unitary, infinite, process-based Super-Existent Being, and dreaming becomes—in this case—an ontological revelation of which the impact is not a message or teaching, but rather a visionary affirmation of transpersonal, metaphysical reality. The phenomenology of such an encounter does not rely on scenes, narratives, characters, or visual-auditory interactions; these all tend to vanish, and there is often no scene, no normative dream contents, only the state of direct participant knowing, beyond words and forms (

Weiss 2015).

The following is an example of a supernal dream from my dream journal:

I dream that I am talking to some friends, two women, when suddenly and very slowly, we begin to leave the ordinary dream dimension. The dream scene fades away, dissolving, until we are in a completely dark and infinitely vast space; slowly we each assume a prone position on our backs, hands folded on chest, eyes closed (I awake in this position). We separate, drifting apart, I am alone, still prone, quiet, no scene, just a vast darkness. Then from a distance, some great Power approaches, transforming my very being—my body begins to radiate energy and by degrees this energy expands while “I” contract until there is only a radiant energy surrounding and penetrating my body, brilliant with color, immensely powerful, extending out into the darkness; my individual identity has ceased, I am one with this radiant, pulsating, cosmic energy. Tremendous waves of color and illumination are pulsating through me, centered on my heart, extending out in all directions, into the vast, dark space. Then from a great distance, a tremendous overwhelming sacred Power or Presence emanates wave upon wave of pure cosmic Light, submerging me, washing over me and through me, instilling a sense of utter glory and holiness intrinsic to that Light. Then I return, slowly, to body consciousness, waking in a very calm state.

I do not regard this kind of dreaming as mythic or psychic, but rather as an ontological encounter with a deeper Being, a Super-Existent initiation, which surpasses normative dreaming and gives the dreamer a transpersonal view, which is directly experiential and yet not necessarily consistent with any specific spiritual or religious tradition. Supernal dreams are openings to very profound dimensions of mystical becoming, but they are not necessarily traditional religious dreams (

Ferrer 2017). They are often dreams of immersion and complete assimilation into a richer and more complex domain of participatory encounter resulting in inner change and transformations. These are dreams that are not forgotten, and which mark the dreamer in deep and profound ways. Religious themes are more likely in mythic dreaming, dreams informed by belief or cultural context; supernal dreams tend to be self-surpassing, and reveal an open horizon far beyond the hyperliminal threshold, revealing themes and ways of knowing that are not yet fully articulated in any spiritual tradition. Supernal dreams are a direct expression of the transpersonal nature of Super-Existent sentient potential, in my experience, which are less coded by symbolism and more informed by energetic dynamics. Such dynamics are state-based, referencing ASC conditions in which there is an expansive perceptual horizon and a felt-sense of empowerment. The ‘charge’ is psycho-ontological, an enhanced sense of participation as a ‘greater being-with’, in a shared, interactive, inclusive context that is supportive of a more profound sense of meaningfulness and value; a state of ‘fullness’ that is not empty but overflowing with surplus.

Supernal dreams as a form of knowledge (gnosis) are not reducible to a content that is either objectively measurable or reproducible, nor can such dreams be induced, though spiritual practices may enhance a person’s capacity to receive such dreams (

Laughlin 2013). Mystics of many traditions have written on the topic of their personal spiritual experiences, usually in the context of their specific tradition (

Irwin 2015;

Marshall 2014), though nature mystics and more contemporary mystical accounts demonstrate a capacity for such experience as being transtraditional, and no longer rooted in classic mystical traditions (