Abstract

This article explores the relationship between manuscripts of ancient religious literature and aesthetic cognitivism, a normative theory of the value of art. Arguing that manuscripts both contain and constitute works of art, we explore paratextuality as a phenomenon that connects manuscript studies to both qualitative and quantitative sides of aesthetic cognitivism. Focusing on our work with a single unpublished gospel manuscript (Dublin, CBL W 139) in the context of a larger project called Paratextual Understanding, we make that case that paratexts have aesthetic functions that allow them to contribute to the knowledge yielded by the larger literary work of which they are a part. We suggest a number of avenues for further research that engages with material culture, non-typography, paratexts, and the arts.

1. Paratexts, Knowledge, and Aesthetic Cognitivism

In this discussion we want to situate the study of manuscripts within the context of both the philosophical and quantitative sides of aesthetic cognitivism by exploring the paratextuality of a complex Byzantine gospel manuscript (Dublin, CBL W 139, GA 2604, diktyon 13571). This new contextualization opens critical avenues for research on the New Testament and other manuscript cultures, while simultaneously creating a significant reservoir of material for the study of the arts. The line that leads from manuscript studies to a normative philosophical stance on the value of art (aesthetic cognitivism) is not necessarily intuitive, but a pathway from one area to the other does exist in the form of paratexts, especially those that have aesthetic qualities. This omnipresent liminal set of features connects manuscripts, visual arts, architecture, and literature in concrete ways. As we will see, it is through the paratext that multiple related lines of research from several disciplines converge, allowing us to form new critical questions and begin to make observations across disciplines.

Let us begin with manuscript studies. A significant trend in this area in recent years has been concerned with material philology. This approach, sometimes called New Philology, originated in the study of early modern European vernacular literature in the late 1980s in reaction to changes in the media of modern literature and the digital turn in humanities scholarship.1 As a sensibility within the larger realm of textual scholarship, New Philology takes seriously each manuscript as a genuine instantiation of a literary work, engaging them not necessarily as evidence for earlier states of the text, but as particular points in a work’s reception. The proliferation of digital images and early online repositories raised fundamental questions for the significance of manuscripts within the larger context of the literary works they represent and preserve, (e.g., McGann 2001). What manuscript features are relevant for the creation of meaning? What types of metadata do we need to encode in digital workspaces to understand literature in its material contexts? The texts that manuscripts transmit will remain central to scholarly practices like textual criticism and edition making; but what of their paratextuality—their titular formulations, marginalia, colophons, cross-reference systems, prefaces, images, and other features specific to particular literary traditions and manuscript cultures? How do these features structure reading experiences and contribute to aesthetic experiences? Are these items constitutive of a literary work, or are they accidental extras to the real substance of the text? Accessibility to digital representations of manuscripts has not only aided textual criticism but has also shed new light on the complexities of communication embedded in these artefacts and the peculiarities of their production. We now know that textual history and textual transmission are instances of reception and that the material aspects and paratextuality of manuscripts influence a work’s ability to yield knowledge to people who read it, (e.g., Butts 2017; Allen 2017; and previously Karnetzki 1956; Fascher 1953).

As a result, textual scholars have begun to re-interrogate the significance of their manuscript cultures for disciplinary questions beyond purely text critical concerns.2 Particularly rich manuscript traditions—like the Greek New Testament, with over 5500 manuscripts copied from the second to the nineteenth centuries in many different locations and cultures—are especially ripe for this kind of investigation. Consequently, the New Testament has received significant recent attention in this context, sometimes in conversation with other early Jewish and Christian literature, (e.g., Lied and Lundhaug 2017; Allen 2019, 2020; Clivaz 2019).3

Historically, most scholarly work on the New Testament’s manuscripts has been oriented toward textual criticism. An outgrowth of this reality is that manuscripts have been viewed primarily as arbiters of texts that can be abstracted from their material context through the critical processes of transcription, collation, and edition making. Manuscripts have at times been treated only as abstract textual vehicles, not concrete physical objects. Important text critical work on the New Testament continues, especially in the form of the Editio Critica Maior (ECM) projects (Houghton et al. 2020), but attention is also turning to examining the significance of manuscript features for a range of historical and literary questions.4 New Philology and cognate methods take a text’s material context seriously, seeking to understand the ways that manuscript features influence reception of a text and how it is interpreted, transmitted, and conceptualized in its different contexts of production. It seeks to reconstruct the ways that ancient and medieval readers ordered and mediated textual knowledge. Text critical approaches to manuscript cultures as large and diffuse as the New Testament must abstract text from manuscripts at some stage in the process if editorial work is ever to be completed to any level of satisfaction.5 New Philology supplements text critical approaches to manuscripts by emphasizing the importance of material contexts for interpreting the semantic valence of texts, acknowledging that many manuscript features are central to the communicative act.

We now come to the paratexts, a set of flexible features that are essential to New Philological explorations of the New Testament and other literary and artistic domains. What constitutes a paratext is notoriously difficult to define with precision due to their structural fungibility, specificity to particular traditions, and diverse functions. A working definition is to define paratexts as every part of a manuscript beyond the main text itself, especially features that have aesthetic qualities insofar as they negotiate a text to readers.6 If we pursue our work from this perspective, aesthetic paratexts incorporate a range of items, including features that help to traverse the codex (e.g., page numbers, tables of contents, segmentation, cross-reference systems, punctuation), describe content (e.g., titular formulations, prefaces, commentary, marginal notations), inform the (perceived) context of production (e.g., epilogues, subscriptions), and visually represent aspects of the text or its world (e.g., illuminations, author images).

We might also consider non-textual features as paratextual, such as layout, writing block dimensions, writing support, ruling patterns, bindings, and covers. These features have aesthetic qualities, features like line, dimension, and shape that convey information about the text, organize access to it, and communicate the value of a work in terms of the costliness and arduousness of its production.7 Manuscripts, especially codices, function as framing devices for texts on multiple levels (Roby 2017). Furthermore, as many have noted, “reading has long been a multi-sensual affair” (Plate 2018, p. 24), with strong visual, tactile, and other sensorial and perceptual aspects that impinge upon reading experiences. Aesthetic paratexts are the thresholds through which readers engage texts, providing semiotic options for traversing a manuscript, limiting, and/or enriching the information that a text might yield.

Paratexts are also diverse in their deployment and are sometimes specific to particular traditions. Some features, such as page numbers and particular forms of the title, transcend the boundaries of time, tradition, language, and genre, and will be familiar to readers of modern print Bibles and other books, while others, like the Eusebian apparatus and Euthaliana, are specific late antique paratextual apparatuses designed to organize the New Testament gospels, Pauline Epistles, and Praxapostolos, respectively (Crawford 2019; Blomkvist 2012). These latter systems are aesthetic paratexts insofar as they incorporate textual, visual, and tabular information in an effort to organize texts, thus creating literary connections internal to the New Testament. The multifariousness of paratextuality creates significant fodder for research, whether that takes the form of creating editions of these underappreciated texts and systems, locating these features and their reception within the intellectual culture of particular historical contexts, or understanding their influence on interpretive procedures.

Another, yet unexplored, aspect of aesthetic paratexts is their relationship to the knowledge that a particular manuscript might yield to a reader as a work of art. As multimodal objects that contain the texts of literary works, (sometimes) visual artworks, and often high levels of craftsmanship and design, manuscripts not only include, but also constitute complex works of art, human endeavor, and acts of communication (Snijders 2015, pp. 6–10). Even if one doubts the status of a manuscript as an artwork (for us, following Goodman 1977, the question is not “is it art,” but “when is art”), the aesthetics of their paratextuality place them easily into conversation with more classical artistic forms (literature, sculpture, drama, film, etc.) that constitute the center of conversation in aesthetics. That manuscripts (and their paratexts) contain and constitute artworks allows them to intervene in a philosophical discourse on aesthetic cognitivism, a normative approach to art undergirded by two assertions: an epistemic claim—“that artworks have cognitive functions,” that they have the capacity to transmit knowledge and enhance learning—and an aesthetic claim—“cognitive functions of artworks partially determine their artistic value” (Baumberger 2013, p. 41; Graham 2005; Gaut 2003; Gaut 2007). In other words, engaging artworks contributes to our understanding of the world, human culture, and ourselves, and their ability to do so is one possible way among many to measure their aesthetic value.8 Or, as Graham puts it, “the value of art is neither hedonic, aesthetic nor emotive, but cognitive, that is to say, valuable as a source of knowledge and understanding” (Graham 2005, p. 52).9 Cognitivist philosophers of the arts have argued that artworks provide access to different kinds of knowledge: propositional (Friend 2007), spiritual (Ganz 2019), experiential, moral (Carroll 2004; Gaut 2007), conceptual (John 1998), practical know-how, and perceptual, among other possible classifications. Each of these categories of knowledge and their significance to evaluating a work of art is debated, but cognitivists largely agree that we can acquire non-trivial, non-reducible information pertaining to different domains of knowledge through engagement with the arts, including literature.

More significantly, according to some, the arts can deepen our understanding of complex ideas and persons as a non-reducible cognitive property, allowing us to re-organize knowledge domains, create new categories, improve cognitive capacities and faculties of perception, and raise new questions for further exploration. Understanding relates to larger bodies of information comprised of many individual propositions, while knowledge can be reduced to discrete units or propositions (Baumberger 2013, p. 43).10 Understanding is, therefore, a more significant category of cognitive achievement. We are interested in this article to begin to explore how the aesthetic paratexts of literary works, like the New Testament gospels, influence the knowledge and understanding that can be gained through encounters with individual manuscripts. This approach also has relevance for the ongoing study of literature in the context of aesthetic cognitivism, building upon the work of Nussbaum (1990), John (1998), and others (e.g., Walsh 1969; Novitz 1987) by bringing a material specificity to the study of literary texts. Attention to paratextuality is an important nuance that is missing in most cognitivist studies of literature.

Another side of the coin of aesthetic cognitivism is quantitative aesthetics. This empirical approach to aesthetic cognitivism seeks to measure the types of knowledge and understanding that artworks and their features inculcate by testing concrete hypotheses.11 A contention of quantitative aesthetics is that if artworks can really yield knowledge, then this acquisition and its processes can be measured experimentally. As far as we can tell, quantitative aesthetics have never engaged with the New Testament or manuscripts cultures. Because manuscripts present so many possible variables within specific objects and across manuscript traditions and cultures, paratexts represent ideal subjects for cognitive and social scientific experiments, carried out in the lab or in the museum. There is fertile ground for empirical study on these features that can supplement classic philological methods. Some paratexts, like the titles of visual artworks, have already been the subject of experiments in the understanding of paintings in museum contexts (Franklin 1988; Becklen et al. 1993; Carbon et al. 2006; Levinson 1985). Many other cognitive scientific studies have manipulated paratexts as variables for better understanding the role of viewer expectations in responses to artworks, (e.g., Barrett et al. 2014), finding that some paratexts have implicit aesthetic functions.

Connecting manuscripts to aesthetic cognitivism is a complex task because manuscript cultures are intricate and specific to particular literary traditions and because aesthetic cognitivism is a vast discourse with its own nuances that has so far focused primarily on literature (as pure text) and the plastic arts. (Our description of aesthetic cognitivism and its philosophical underpinnings is necessarily curt). In an effort to negotiate these difficulties at a preliminary stage, we focus here on one manuscript and its paratexts—an early twelfth century deluxe Greek gospel codex (Dublin, CBL W 139, GA 2604, diktyon 13571)12—briefly summarizing our work with this manuscript and describing its paratexts and their relationship to knowledge domains, all in order to begin to understand the ways that they mediate knowledge of the text and other forms of understanding to readers. In this context, we focus in particular on the elaborate aesthetic paratext of the Eusebian apparatus, which has recently received significant scholarly attention (Coogan 2017; Crawford 2019; McKenzie 2016). We conclude by articulating a number of questions raised by our work in the context of a larger project called Paratextual Understanding that explores the questions raised here in relation to CBL W 139. We offer three broad avenues that can be explored in the future by way of quantitative analysis. The interdisciplinarity of our work and the technical intricacies of philological, philosophical, and scientific discourses have forced us to begin this article with a lengthy description of the fields and their relationships. Now we can move on to a specific case: CBL W 139.

2. Digitally Editing CBL W 139

The paratextuality of CBL W 139 is vast and at times overwhelming. The list of its contents, varied as they are, does not fully do justice to its paratextual dimensions (see Table 1).13 Every folio is embedded with traditional paratexts, in addition to the interlocking features of larger paratextual systems.14 These items overlap in ways that both hinder and inform the reading of the gospels in a linear way—the paratexts that preface and co-exist with each folio of gospel text coalesce to pull the reader toward juxtaposed textual segments, liturgical practices, commentary, preface, and tabular formulations, while simultaneously enabling interpretive activities. The text of the gospels in W 139 is hypertextual; conduits of cross-reference and contextualization are embedded in a way that structures the text within the manuscript.

Table 1.

Contents of CBL W 139.

To begin to grapple this complexity in the context of aesthetic cognitivism, we started, as most textual scholars would, by creating a rough digital edition of the manuscript, emphasizing its paratexts by modelling their relationship to the text within the confines of the digital tools available to us. This inductive study afforded the opportunity to become deeply familiar with the manuscript’s reading pathways, controlled foremost by the Eusebian cross-reference system, and the potential interactions between text and other paratexts, especially the catena traditions that appears in the upper, lower, and outer margin of nearly every folio of gospel text (see Figure 1). Although it is a tool that was designed for the production of eclectic critical editions, we used two editorial tools available in the New Testament Virtual Manuscript Room (NTVMR): the transcription editor, which allows us to transcribe gospel text and nest paratextual elements in relation to the larger textual structure, and the Feature Tags tool, which enables the direct markup of the digital images, noting the presence, location, and type of paratexts on each folio. These parallel processes constitute our “edition” of the manuscript, which will be accessible to anyone who engages the manuscript on the NTVMR. In essence, we added metadata pertaining to this manuscript’s paratexts to the digital repository and workspace.

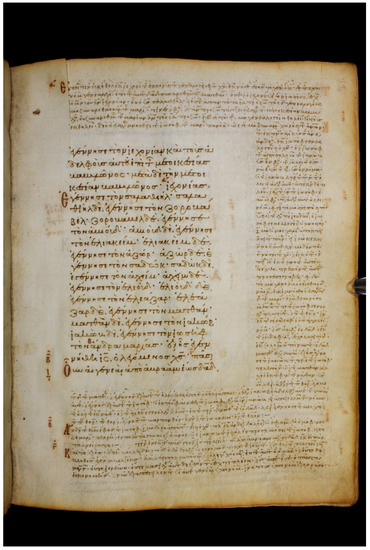

Figure 1.

Dublin, CBL W 139, 31r. Three numerated (α-γ) catena extracts in the margins, framing 20 lines of the text of Matthew’s genealogy.22

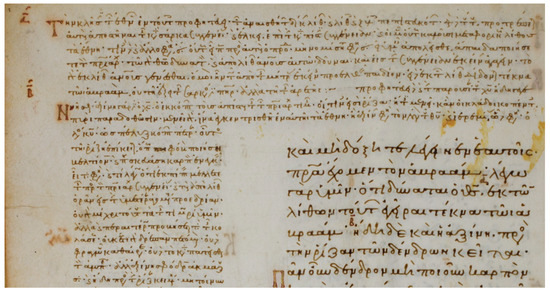

Our transcription of the main text of the gospels was made by manipulating a base text for the passage contained on any one folio (in this case, the critical text of Nestle-Aland28), the parameters of which were set in advance by our indexing of the manuscript. This process occurs within the Transcription Editor (Figure 2).

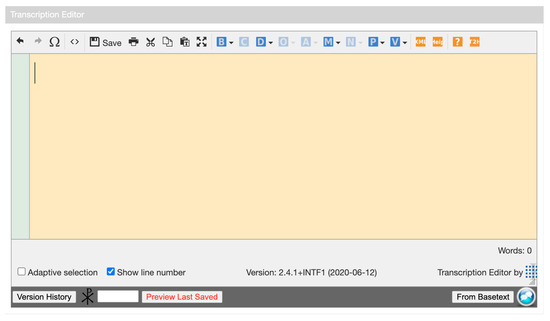

Figure 2.

New Testament Virtual Manuscript Room (NTVMR) Transcription Editor.

The text of the manuscript can be manipulated in the Editor’s yellow field and, additionally, its menu options are segmented into tabs that enable the encoding of different paratexts.23 CBL W 139 has a highly regulated and consistent layout, comprised of twenty lines of gospel text on each folio in a single column, which simplifies the transcription process. First, we adjust the base text to correspond with the layout of the manuscript by adding line, column, and page breaks thus providing a representation of the folio (e.g., Figure 3).

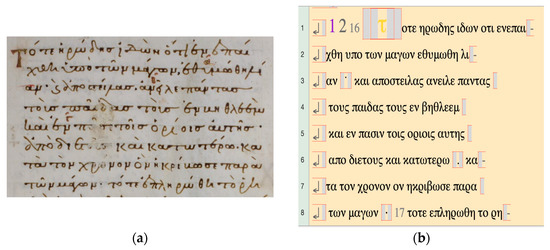

Figure 3.

First 8 lines of CBL W 139, 34r (Matt 2: 16–17) (a) and transcription of the text with punctuation, line breaks, and one ornamentation note (b).

Then we modified the text in the Editor to reflect the text of the manuscript, character by character, by adjusting the base text. This process includes inputting corrections made either by the original or subsequent scribal hands. Corrections of various kinds were input using the correction tab. For example, in Matt 7:24 a second hand inserted ομοιωσω αυτον (“I will liken him”) above ομοιωθησεται (“he will be likened”), changing the voice of the verb from passive to active and adding a direct object (Figure 4).

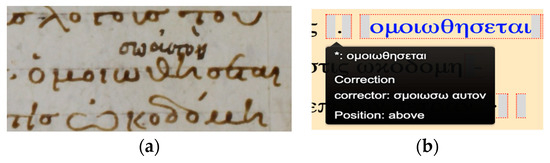

Figure 4.

CBL W 139, 47v, a second hand inserts [ομοιω]σω αυτον above ομοιωθησεται (a), and correction made on the Transcription Editor (b).

The transcription process also included the encoding of abbreviations, like nomina sacra (e.g., Figure 5) and numbers, as well as punctuation. However, we ignore some features like iota adscript, breathing marks, and accents, and we record ligatures in the manuscript as individual characters in the transcription.

Figure 5.

CBL W 139, 123r, nomina sacra Ι[ησο]υ Χ[ριστο]υ in Mark 1:1: Aρχη του ευαγγελιου Ι[ησο]υ Χ[ριστο]υ.

The Editor also enabled the encoding of instances of textual ornamentation, both for the base text and paratexts, like changes to ink colors (gold and red are used regularly) and the presence of capital letters occur on nearly every folio (Figure 6). Most sections in the base text and the catenae begin with a gilded ornamented capital letter set just into the left margin. Gold ink is also used in the titles of each gospel, preface titles, kephalaia (chapter) titles (Figure 7), and the machinery of the Eusebian and liturgical apparatus.

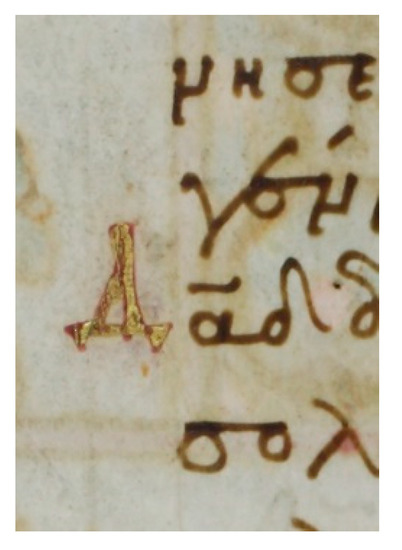

Figure 6.

CBL W 139, 30v, Matt 1:6. An example of a nomen sacrum (Δα[υι]δ), capital letter, and gilded ink, all features of one word input into the Editor using three different editorial operations to record these paratextual dimensions.

Figure 7.

CBL W 139, 176r, kephalaion of Mark 15:37–16:20. πε[ρι] της αιτησεως τ[ου] σωματος του κ[υριο]υ (Regarding the Request of the Body of the Lord).

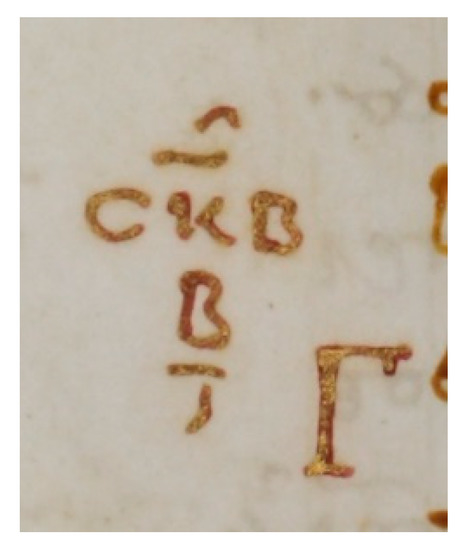

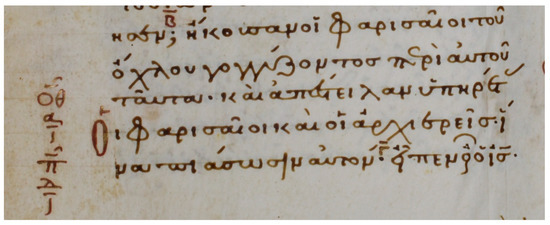

The individual items of the Eusebian and liturgical systems are also input where they appear in the manuscripts, using the marginalia menu. These features include the Ammonian sections (progressive numerical designations for each individual pericope as delineated by Eusebius in late antiquity, based in part on the antecedent Diatessaron-gospel produced by Ammonius), paired with corresponding Eusebian canon numbers (numbers that locate each pericope on one of the ten canon tables (4v–9r), denoting the pericope’s relationship to other canonical gospels). Information on the times of liturgical performance, cross-referenced to synaxarion and menologion tables at the beginning of the manuscript (13r–21r) are also recorded using this menu (Figure 8 and Figure 9).24 The transcription of lectionary notations is more complicated due to their abbreviated form and sometimes indistinguishable script (Figure 10).

Figure 8.

CBL W 139, 175v, (Ammonian) section number (σκβ, 222) (top) and canon number (β, 2) for Mark 15:36.

Figure 9.

CBL W 139, 6r, Eusebian Canon II (agreement among the Synoptic gospels), Section 222 for Mark in column 5 line 17.

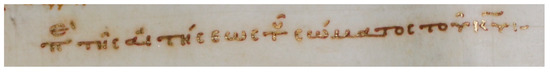

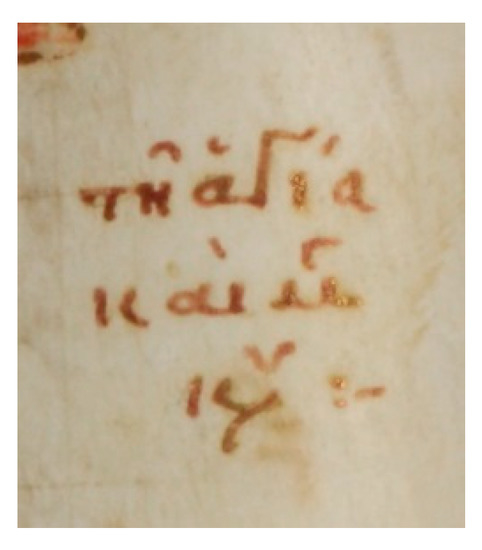

Figure 10.

CBL W 138, 279r. Lection notation for John 1:1–17: τη αγια και μ[ε]γ[αλη] κυ[ριακη] (The holy and great Sunday).

Aside from the Eusebian system, to which we will return, the most obvious paratext of CBL W 139 is the catenae wrapped around the main text, comprised of traditional excerpts from early Christian writers. We input this material using the “isolated marginal note” tag in the marginalia menu as a place holder. For most catenae, we usually provide only the incipit (the first 5–10 words), but locate the commentary vis-à-vis the main text, which is linked to the marginal comments via Greek graphemes. In the instances where we transcribed the entirety of the catena text, we used Thesaurus Linguae Graecae to identify a basic base text, supplemented by texts in older editions, (e.g., Cramer 1844). The catenae in CBL W 139 map imperfectly onto Reuss’ taxonomy of gospel catena traditions, but it does overlap with some traditions edited by Cramer and others.25 For our purposes, the most important aspect of transcribing the catena was to encode their position vis-à-vis the main text upon which they comment (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

CBL W 139, 35v. Catenae surrounding Matt 3:9–13. The first catena section (α, top margin) corresponds to the α above line three of the main text (εκ τω[ν]) and the second section (β) to the on line five (ηδη δε και). Note that the β catena begins on the line before the capital nu on line seven of the catena.

The second aspect of our editorial work that has informed our perspective on the relationship between paratextuality and knowledge is the direct tagging of paratexts in the digital images of the manuscript. This work is completed using the “Add Feature” tool of the NTVMR, a tool that allows scholars to place a digital box around the feature on the images and provide further metadata on that feature, using existing and customized tags. For example, consider 30r, the title page for Matthew’s gospel (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Screenshot of the NTVMR’s “Add Feature” tool, showing a selection of the features tagged on 30r of CBL W 139.

This folio, along with the title pages of the other gospels, is particularly ornamented. It includes not only the title of the work in ornamental script and gold letters (inscriptio), but also a phytomorphic headpiece similar to the canon tables, three catena extracts, and the Eusebian notation associated with Matt 1:1 just left of the large illuminated initial letter. The substance of these items is not input here—only their presence is recorded—but the marked-up images can be compared to the transcriptions to create a holistic view of this manuscript’s paratextuality.

3. The Eusebian Apparatus and Taxonomy of Knowledge Domains

Our editorial work with a heavily mediated manuscript like CBL W 139 has directly informed our thinking on the relationship between manuscripts, paratextuality, and aesthetic cognitivism, stimulating a number of questions about the function, perception, and cognitive weight of paratexts in the processes of interpretation. Aesthetic paratexts are essential aspects of reading in manuscript cultures (and other media), and if we can gain knowledge and understanding from literature, as most aesthetic cognitivists claim, then what types of knowledge can paratexts yield or mediate to readers? Because the paratextuality of W 139 is so all-encompassing, we want to in the first instance focus on the ways that one of the more obviously aesthetic systems of textual knowledge that exists in this manuscript—the Eusebian apparatus—instils different forms of knowledge. Our focus on the Eusebian apparatus is only one possible example of an aesthetic paratext among many preserved in this manuscript. However, we chose to focus on it here because it creates a complex network of relationships between the literary works that stand at the heart of the codex and because the Eusebian apparatus is so central to understanding the transmission and reception of the gospels from late antiquity onward.

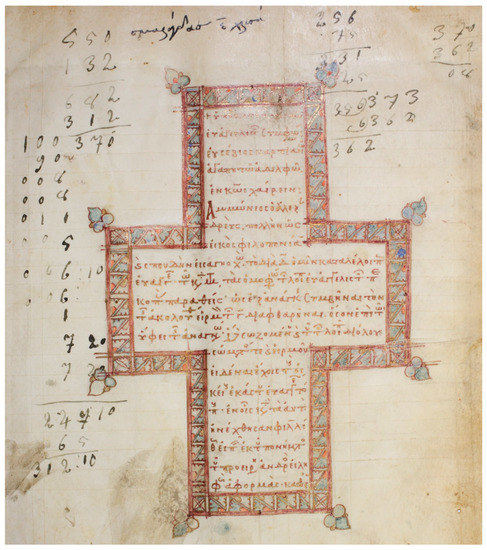

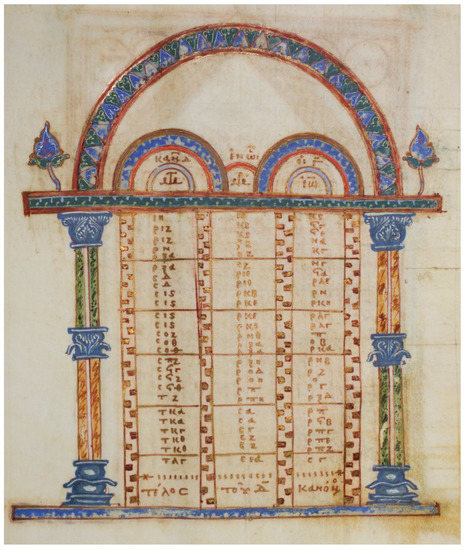

The apparatus consists of three interlocking features produced initially by Eusebius of Caesarea in the early fourth century, components that appear in varying combinations in hundreds of gospel manuscripts in multiple linguistic traditions.26 Its first feature is the Letter to Carpianus, which is the first text to appear in W 139 (2r–4r) (Figure 13).27

Figure 13.

Dublin, CBL W 139, 2r. Letter to Carpianus in cruciform design. The shared artistic dimensions of the Letter, the canon tables, and the headpieces for each gospel connect the facets of the Eusebian system to the gospel texts.

In the Letter, Eusebius begins by describing the scholarship he adopted from his predecessor, Ammonius, who created a Diatessaron-Gospel (τὸ διὰ τεσσάρων…εὐαγγέλιον). Ammonius placed parallel pericopae from Mark, Luke, and John in columns alongside a column containing the continuous text of Matthew.28 This process allowed readers to compare the wording and presence of parallel passages in each of the New Testament gospels, but indelibly ruptured the narrative flow of Mark, Luke, and John, subjugating their structure to that of Matthew. In Ammonius’ creation, it was impossible, or at least too convoluted to be practical, to read the non-Matthean gospels in a linear fashion. In an effort to preserve the narrative flow, or as Eusebius puts it, to “preserve the body and sequence of the other [gospels] throughout” (ἵνα δὲ σωζομένου καὶ τοῦ τῶν λοιπῶν δι᾽ ὅλου σώματος), he instead mapped the relationships of the four gospels as reflected in Ammonius’ work onto ten tables, assigning each possible parallel pericope a number. These tables capture the possible combinations of shared material between these works, thus enabling cross-referencing between the gospels without interrupting their narratives by way of the tables (Table 2).

Table 2.

Contents of the Canon Tables.

The Letter concludes with an explanation (διήγησις) on how to use the tables. The text of each gospel section is identified by a sequential series of numbers, beginning with one and continuing to the end of the work,29 breaking each gospel into a successive series of pericopae while also retaining narrative integrity. The numbers can be located as necessary on the tables without interfering with desires for linear readings of Mark, Luke, and John. Below each of these section (κεφαλαίῳ) numbers, another number from one to ten appears in red ink, denoting the table to which that given section belongs. For example, if we take the notation in Figure 8 (σκβ/β or 222II), we can infer that §222 of Mark is located on canon II, indicating that it has parallels in Matthew and Luke. If we wish to compare these texts, we can turn to canon II. There we learn that §222 of Mark is paralleled in §342 of Matthew and §323 of Luke. We can then flip to these sections of the parallel works to facilitate comparison, holding our fingers in different places in the codex. The text of the gospels themselves are not distributed into columns according to the narrative of Matthew (as in Ammonius’ Diatessaron-Gospel), but numerical representations of their pericopae are arranged in tabular format according to perceptions of their literary and thematic similarities to sections of the other gospels. The Letter to Carpianus spells out the background, rationale, and intended functionality of the system.

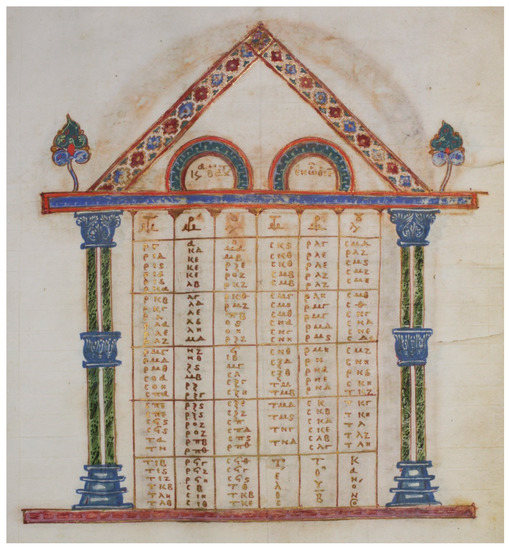

The second feature of this paratext is the ten tables themselves, which are really comprised of nine tables (canons I-IX, which can be read either horizontally or vertically) and four lists (canon X, which offers one list of material unique to each gospel). As is the case with CBL W 139 (e.g., Figure 9 and Figure 14), the canon table are aesthetic in their artistic emphasis and framing function, adorned sometimes even with images that reflect the larger reception history of the gospel tradition (Nordenfalk 1938; McKenzie 2016; Crawford 2019, pp. 228–84). Aside from the art historical significance of the canon tables, they are important insofar as they represent Eusebius’ perception of the textual interrelationships of the four gospels, facilitating cross-reference, non-linear reading practices, and other scholarly endeavors. Take, for example, canon IV in W 139 (Figure 14 and Table 3).

Figure 14.

CBL W 139, 7r. Canon IV: Pericopae shared only by Matthew, Mark, and John.

Table 3.

Canon IV from CBL W 139 translated.

The left-hand column lists the pericopae from Matthew in its serial order. The middle column records parallels in Mark, and the right-hand column records texts from John. This table constitutes a type of visualized textual data, as Crawford (2019, pp. 33–55) has recently argued, recoding every pericope (represented by the corresponding number assigned to each) where Matthew, Mark, and John share substantial material (at least according to the tradition of Eusebius’ reckoning preserved in this manuscript).

Without even looking at the associated texts, we can make a number of preliminary judgements about the aesthetics of the literary relationships of these three gospels. First, they agree together without parallel in Luke only rarely. Only seventeen pericopae from Matthew and Mark appear on the list, while 26 appear from John. Furthermore, if we read vertically down each column, we gain a terse view of the narrative differences of each gospel. The numbers in Matthew’s column are in numerical order, from §18 (ιη) to §333 (τλγ), with the majority of parallels coming from the second half of the work and the passion narrative. It is not necessarily significant that Matthew’s numbers appear in serial order because in canons I-VII it is the first gospel’s order that determines the arrangement of the sections of the other columns. More telling is that the numbers in Mark’s column also follow the same narrative order; they too are in their narrative order from §8 (η) to §211 (σια), and wherever a section from Matthew is repeated, Mark follows suit. For example, Matthew’s §216 (σιϛ) occurs four times, paralleled in each instance by Mark’s §125 (ρκε). At least where they overlap with John, Mark and Matthew have similar narrative arrangements.

On the other hand, John’s column fails to follow anything close to its numerical sequence, and it is John’s distribution of material that requires the repetition of section in Matthew and Mark. For example, material from Matthew’s §216 (Matt 21:22, “and all that you ask for in prayer in faith you will receive”) and Mark’s §125 (Mark 11:24, “and this I say to you, all that you pray for and seek, believe that you have received it and it will be so”), are paralleled in four separate sayings of Jesus in §128, 133, 137, 150 (John 14:13; 15:7, 16b; 16:23). In this case, the canon grouped together quantitatively small, individual sayings of Jesus based on their lexical and thematic overlap. More broadly, we can begin to visualize the shape of each gospel’s narrative in relation to the others by examining the numbers in the table, especially John’s differences to the two synoptics gospels here. However, more importantly, and more to the intended function of the tables, this visualization of the data enables the comparison the texts represented by these numbers because the numerated pericopae and canon table numbers appear in the margins of W 139.32

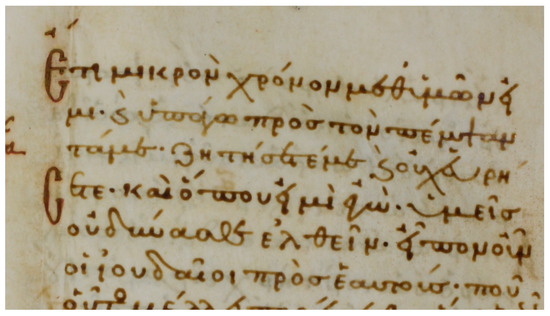

In order for the tables to be of use in facilitating cross-references when reading the gospels, the numbered pericope must also appear in the margins of the manuscript at the proper location. For instance, if you glance at what we now refer to as John chapter seven, you come to the section where the chief priests send soldiers to arrest Jesus because the crowd is speculating as to whether he is the messiah (7:32). No further narration is forthcoming on the efficaciousness of this law enforcement effort: Jesus does not address the Pharisees, the priests, or any officers who might be trying to take him into custody. Instead he says, to no one in particular, “I am only with you a little while longer (Ἔτι χρόνον μικρὸν μεθʼ ὑμῶν εἰμι), and then I will go to the one who sent me” (7:34). The “Jews” respond incredulously among themselves, reported by the narrator in 7:35: where is he going? Among the Greeks? What does he mean we will not be able to find him?

Contemplating this passage, you might be confused by Jesus’ response and the passage’s narrative incohesion. However, in W 139 and other manuscripts with the Eusebian apparatus, you have some recourse. Returning to the start of the sentence where Jesus responds to the threat of arrest (the last four words of the last line of 319r, Figure 15), the reader may see the notation π/δ (80IV) in the left margin. From this item it is evident that the reader has now arrived at §80 of John and that the corresponding parallels to this section can be found on canon IV (Figure 15). Without even turning the pages back to canon IV (7r), you already know that parallels to this saying can be found in Matthew and Mark. Turning to 319v, you can see that a new section starts on line 3, meaning that §80 encompasses this single saying of Jesus (Figure 16). Once you turn to the table (see Figure 14 and Table 3), you can read vertically down John’s column until you find §80 (π) and then horizontally to the left to Mark (§159) and Matthew’s column (§277).

Figure 15.

CBL W 139, the last lines of 319r. Eusebian in the left margin, the first words of John 7:33 beginning with ειπεν.

Figure 16.

CBL W 130, the first lines of 319v. John 7:33 ends after με on line 3, where Section 81 (πα) of John begins.

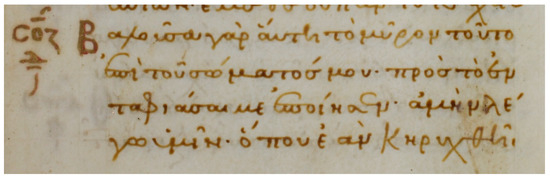

So, you start by finding the parallel in Matthew (107r, Matt 26:12–13, Figure 17) to see if it will help you to make sense of what Jesus means or why the narration of the scene in John is so terse. This pericope incorporates Jesus’ final saying as part of the anointing at Bethany before his entrance into Jerusalem. In response to grumblings about the woman who poured expensive ointment on his head (26:6–7), Jesus says that she has prepared him for burial (26:12) and that wherever the gospel is preached, people will remember her actions (23:13). Mark’s version of the event (168r-v, Mark 14:8–9) is very similar to Matthew’s.

Figure 17.

CBL W 139, last four lines of 107r. Matt 26:12–13 with Eusebian §277 (σοζ) in the left margin.

At first glance, these parallels are not “parallels” at all, and they do not help you to understand Jesus’ conflict with the “Jews” in John and his statement that he will only be with them a little longer. Instead, the reader might expect a connection to Jesus’ anointing by Mary in John 12:1–9. However, the larger context of the “parallels” in Matthew and Mark offer at least a vague connection. The sentences that immediately precede Matthew §277 and Mark §159 (Matt 26:11//Mark 14:7) both record Jesus speaking about the poor. In Matt 26:11, he says, “for you will always have the poor with you, but you will not always have me” (πάντοτε γὰρ τοὺς πτωχοὺς ἔχετε μεθʼ ἑαυτῶν, ἐμὲ δὲ οὐ πάντοτε ἔχετε). Mark’s version of the saying in 14:7 is similar. The pericopae in this case (Matthew §277//Mark §159//John §80) are not true juxtapositions of shared material; all three are sayings of Jesus, but John’s has nothing to do with woman who anointed Jesus, it has no significant lexical links to the synoptic parallels, and has no contextual similarity to the story in Matthew and Mark.

However, the material in Matthew and Mark can be viewed as implicit interpretations of the Johannine saying by way of juxtaposition. The juxtaposition of numbers on a table creates textual relationships across three gospels. When we take into account the larger context of Jesus’ response to the anointing at Bethany, he does mention the fact that he will remain with his followers only for a short time, comparing his imminent absence with the perdurance of the poor. Connecting this statement to the idea that this anointing was for his burial, it is clear that Jesus’ time is short in John because of his impending death. This understanding is certainly also implied in John 7:33, setting into relief the misunderstanding of Jesus’ opponents in their assumption that he is going to go out among the Greeks (7:35). By setting these apparently disparate passages (Jesus’ feuding with the Pharisees and his anointing at Bethany) alongside one another in canon IV, this point becomes clearer for the Johannine passage. We can also see why other versions of the Eusebian system place John §80 in canon X as unique Johannine material.

The Eusebian paratext facilitates many different forms of scholarship and comparison. In the process, the system makes judgments about what constitutes a parallel, functioning ultimately as a complex system of data visualization predicated on many interpretive procedures. The composition and function of the system mediate knowledge of the text of the gospels, the substance of literary relationships, and other religious ideas. It is not feasible to contrive a maximalist taxonomy of the forms of knowledge that a paratext like the Eusebian apparatus might yield—its complexity militates against this—but we think that the system reveals knowledge in at least three domains that leads to greater understanding in a cognitivist sense.

First, like literary fiction (John 1998), paratexts have the potential to instill conceptual knowledge, or at least challenge the concepts readers may bring to a work. The Eusebian apparatus is the product of a number of concepts, and those who use the system must at least tacitly engage with some of these ideas. For example, the system assumes an orderliness to the gospels despite their apparent contradictions and differences, providing tools to navigate the complexities of the material. The system brings conceptual questions to the surface about the nature of scripture, the function of (each of) the gospels, how these works should be read, and even the larger order of the cosmos reflected in scripture. It is a tool that enables new ways of thinking about the gospels. If “pursuing literary knowledge means paying closer attention to the text, engaging with it more imaginatively” (Rowe 2009, p. 393), then the Eusebian system enables and is the result of such a pursuit by presenting patterns and coherences across the gospels that may or not be obvious to an average reader. For example, Crawford has argued that the choices Eusebius made to craft ten tables that reflect the relationship between the four gospels, then various relations of three, then two, then one (4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 10) corresponds to his view of the cosmos as coherent with arithmetical computation. For Eusebius, the gospels are a microcosm of the created order; he saw himself as “producing a new technology that revealed the divinely ordered ‘polymorphic diversity’ evident in the church’s four canonical texts” (Crawford 2019, p. 95). The apparatus provides access to further knowledge on the text itself, but also to other external realities inherent in creation, at least as Eusebius perceived it.

Second, paratexts also offer different kinds of historical or propositional knowledge. Sometimes this knowledge can also be learned from other secondary sources, but the paratexts of ancient religious literature are the implicit residues of historical choices and perception of texts and reality writ large. The acquisition of propositional knowledge through paratexts remains, to our minds, a cognitive achievement (Friend 2007). We can better understand scholarly practices in late antique Caesarea by engaging Eusebius’ apparatus, and we can then trace its development in different contexts as further receptions of the system as an integral part of the gospel tradition. Philologists largely restrict their engagement with paratexts to their ability to offer propositions about past engagements with ancient texts. There remains much further exploration to be done along these lines.

Third, the Eusebian apparatus transmits theological or spiritual knowledge. The creation of a multitude of relationships between segments of texts that stand at the center of Christian tradition enables the enrichment of theological ideas by juxtaposition.33 Juxtaposition is a powerful suggestive tool, often used by artists, that creates relationships between items that may share unperceived or underdeveloped qualities, forcing readers, viewers, and listeners to reason out the logic behind the choice. The Eusebian apparatus produces many other literary and theological effects, but juxtaposition is an especially potent way of placing items that do not normally share the same domain into a new generative context that creates the space for the development of knowledge. This function of the apparatus makes it a tool for theological thinking and the exploration of spiritual realities, providing interpretive vantage points that might otherwise remain unexplored. The preceding example from canon IV that places Jesus dispute the Pharisees in John alongside the anointing at Bethany in Matthew and Mark highlights Jesus’ foreknowledge of his own death—gleaned from Matthew and Mark’s account—and suggests that his death will ultimately lead to his return to his father—gleaned from the text in John. When set side by side, these dissonant accounts create a picture that reinforces a synthetic theology of Jesus’ death, resurrection, and glorification derived from aspects of each of these three gospels. Each gospel narrative in their own ways hint at Jesus’ foreknowledge of his fate and the fact that he will ultimately continue to act alongside his people upon his resurrection. The counterintuitive juxtaposition of these texts gives rise to, or at least creates the conditions for, further theological insight. This is the value of juxtaposition.

Each of these forms of knowledge are integral to the paratext as a work of art. There are surely other paths to some of these forms of knowledge, but the Eusebian system expedites their accessibility through its cross-referentiality and visualization of gospel interrelatedness. The apparatus binds the four gospels into an interconnected work, allowing them to work together to instill theological ideas and create a narrative of the significance of God’s activity in the world. The apparatus enables the gospels to elaborate propositions about their main character, Jesus, in a way that both overcomes and is cognizant of their apparent contradictions.

4. Eusebius and Understanding

What makes the Eusebian system something that enables cognitive achievement is not necessarily its ability to instill discrete bits of knowledge. Instead its advancement of our understanding of the gospels themselves and their narrative texture, and its ability to provide new perspectives on their literary interrelationships, is its defining significance. Each gospel conveys a narrative of Jesus’ life and its significance for God’s engagement with the world. These narratives are complex, stylized, selective, each making the case in their own way that Jesus is God’s messiah and drawing upon traditions from Jewish scripture and Roman imperial authority to substantiate these claims. Each individual gospel constitutes a literary work of art that transmits a particular message, working to enrich human understanding of God’s activity from a particular perspective. The Eusebian apparatus enhances the individual artistic quality of the gospels even further by visualizing the relationships between them, enabling comparison and tying the works together in a web of mutual interconnectivity. It creates an aggregate work, a closed literary network where the inconsistencies of each gospel are both laid bare and subsumed under an implicit overarching argument about Jesus’ identity. In the Eusebian system, the gospels are blended together into one work, each retaining their individual substance; they become a polyptych comprised of individual images that constitute a larger whole, a work that can be read following any number of possible pathways from the linear reading of each narrative to a highly atomistic and hypertextual juxtaposition of smaller utterances across the gospels. Their similarities and their differences become impossible to ignore.

The aesthetic properties of the paratext implicitly stress claims about the gospels, their message, and relationships. The system creates a new vantage point from which to assess the gospels and their narratives, allowing us to imagine new ways of reading, referentiality, and interpretive possibilities. It directs the mind by making us more aware of what the gospels contain.34 It creates a new “mode of attention” toward the gospels and their message (Rowe 2009, p. 378). We can see the gospels from different angles, perspectives that their individual authors and traditors never intended or imagined. The system creates the space for an active literary imagination, providing ample opportunities for engaged readers to achieve a deeper understanding of these works, their message, contexts, and interpretation. It reconfigures our understanding of the gospels and their interrelationships, allowing “hitherto overlooked or underemphasized features, patterns, opportunities, and resources to come to light” (Elgin 2002, p. 1).

The Eusebian paratext visualizes the fact that the knowledge transmitted by the gospels as narratives is inextricable from these narratives and their literary interrelationships; content becomes inextricable from form. Although the paratexts of modern book publishing are designed to sell copies (think the puffery of blurbs, abstracts, and author biographies), the paratexts of ancient religious literature, at least those with aesthetic qualities, enrich our understanding of the literary work to which they are attached. Just as art helps us to see the world afresh, paratexts help us to perceive their texts anew. Paratexts have the capacity to enhance literature in ways that are cognitively relevant, and their omnipresence in many literary cultures suggests that they play a significant role in cognition and perception.

5. Manuscripts and Aesthetic Cognitivism: Prospects and Avenues

As Graham notes, “it is easy to assert that art has cognitive value, much harder to explain how” (Graham 2005, p. 55). The goal of the Paratextual Understanding project and our work with this manuscript constitute preliminary attempts explain how artworks, mediated through their paratextuality, afford access to knowledge, knowledge that can inculcate understanding. We stand still at the starting line of this ambitious goal. Nonetheless, our work has revealed at least three promising avenues of further study on paratexts that are amenable to quantitative experimentation.

First, we think that paratexts reveal new knowledge of the work to which they are attached by drawing attention to one particular aspect the work, such as its plot, segmentation, message, scope of reference, or intertextual relationships. The way that paratexts draw attention to particular features of a work function similarly to reductionism in abstract art that draws attention to one feature like line or color (Kandel 2016). The Eusebian apparatus, for example emphasizes the literary interrelationships of the gospels by enabling manual cross-referencing. The bespoke nature of paratexts enables them to transmit different forms of propositional, conceptual, and theological knowledge, all of which culminate in understanding insofar as they reflect and order intellectual effort and larger views about the world.

Our second vector for further research on paratexts in the context of aesthetic cognitivism is the idea that paratexts are essential features of the way that (religious) literature yields knowledge. Philologists and literary critics have theorized that paratexts are somehow central to processes of interpretation and understanding. However, it would be advantageous for philologists to work with cognitive scientists to craft experiments that test the role of paratexts in interpretation and perception. How do the aesthetics of paratexts—their colour, size, location, density—change perceptions of the text? How does the mind perceive and process these features? How does viewer expertise and background influence interpretation? These questions remained unanswered.

Our final suggestion for further research pertains to the idea that the cognitive efficacy of paratexts improves over time (as the paratexts of ancient literature are transmitted) because they are one vector for the development of religious ideas. This avenue relates to the transmission of paratexts across chronological planes, like the reception of the Eusebian system from late antiquity onward. Changes to the aesthetic proclivities of paratexts reflect, in part, changes in religious practices and the development of spiritual realities within these traditions. If we were to, say, test the cognitive efficacy of different forms of the Eusebian system based on its aesthetic features in the manuscripts, would we find that readers are able to better understand its mediating function and come to a greater understanding of the gospel tradition as the tradition develops?

6. Conclusions

The preceding discussion has illustrated the importance of paratexts in the study of manuscripts, the New Testament, and other disciplinary avenues. An artefact with dense paratextuality like CBL W 139 is an example of how complex systems such as the Eusebian apparatus can yield multiple types of knowledge (conceptual, propositional, theological) and understanding, while also being a window into the reception of interpretive traditions. We have sought to demonstrate throughout this essay that paratexts are essential to the interpretation of a text and are therefore inseparable from the main body of work. Paratexts with aesthetic qualities, many of which we have edited in our edition of W 139, function as a sort of bridge between philology and pursuits associated with aesthetic cognitivism.

The multiplicity of paratexts in this deluxe manuscript has allowed us to follow several lines of research that are relevant for examinations not only of W 139, but any manuscript, piece of literature, or work of art. Further collaborative work between philologists, philosophers, theologians, and cognitive and social scientists is required to explore the potential of the approach we have advocated for here.

Author Contributions

Data curation, A.P.R.; Funding acquisition, G.V.A.; Project administration, G.V.A.; Writing—original draft, G.V.A. and A.P.R.; Writing—review & editing, G.V.A. and A.P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from Templeton Religion Trust. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Templeton Religion Trust. Research for this publication also received support from the TiNT project, funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 847428). Garrick V. Allen is a research associate of the School of Ancient and Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Pretoria.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allen, Garrick V. 2017. Textual History and Reception History: Exegetical Variation in the Apocalypse. NovT 59: 297–319. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Garrick V. 2019. Paratexts and the Reception History of the Apocalypse. JTS 70: 600–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Garrick V. 2020. Manuscripts of the Book of Revelation: New Philology, Paratexts, Reception. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andrist, Patrick. 2018. Toward a Definition of Paratexts and Paratextuality: The Case of Ancient Greek Manuscripts. In Bible as Notepad: Tracing Annotations and Annotation Practices in Late Antique and Medieval. Biblical Manuscripts. Edited by Liv Ingeborg Lied and Marilena Maniaci. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 130–49. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Justin L., Jean-Luc Jucker, and Rafael Wlodarski. 2014. ‘I Just don’t Get It’: Perceived Artists’ Intentions Affect Art Evaluation. Empirical Studies of the Arts 32: 149–82. [Google Scholar]

- Baumberger, Christoph. 2013. Art and Understanding: In Defence of Aesthetic Cognitivism. In Bilder Sehen: Perspektiven der Bildwissenschaft. Edited by Mark Greenlee, Rainer Hammwohner, Bern Köber, Christoph Wagner and Christian Wolff. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, pp. 41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Becklen, Robert C., Charlotte L. Doyle, and Margery B. Franklin. 1993. The Influence of Titles on How Paintings Are Seen. Leonardo 26: 103–8. [Google Scholar]

- Blomkvist, Vemund. 2012. Euthalian Traditions: Text, Translation and Commentary. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Butts, Aaron Michael. 2017. Manuscript Transmission as Reception History: The Case of Ephrem the Syrian (d. 373). JECS 25: 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon, Claus-Christian, Helmut Leder, and Ai-Leen Ripsas. 2006. Entitling Art: Influence of Title Information on Understanding and Appreciation of Paintings. Acta Psychologica 121: 76–198. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Noël. 2004. Art and the Moral Realm. In The Blackwell Guide to Aesthetics. Edited by Peter Kivy. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 126–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cerquiglini, Bernard. 1989. Éloge de la variante: Histoire critique de la philologie. Paris: Éditions de Seuils. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier, Roger. 1995. Forms and Meanings: Texts, Performances, and Audiences from Codex to Computer. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, Anjan. 2014. The Aesthetic Brain: How We Evolved to Desire Beauty and Enjoy Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chester Beatty Online Collections. n.d. Available online: https://viewer.cbl.ie/viewer/object/W_139/10/LOG_0000/ (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Clivaz, Claire. 2019. Ecritures digitales: Digital Writing, Digital Scriptures. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Coogan, Jeremiah. 2017. Mapping the Fourfold Gospel: Textual Geography in the Eusebian Apparatus. JECS 25: 337–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, John A. 1844. Catenae Graecorum Patrum in Novum Testamentum. Oxford: Typographeo Academico, vols. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, Matthew R. 2015. Ammonius of Alexandria, Eusebius of Caesarea and the Origins of Gospel Scholarship. NTS 61: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crawford, Matthew R. 2019. The Eusebian Canon Tables: Ordering Textual Knowledge in Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elgin, Catherine Z. 2002. Art in the Advancement of Understanding. Philosophical Journal 39: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fascher, Erich. 1953. Textgeschichte Als Hermeneutisches Problem. Halle: Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Margery B. 1988. ‘Museum of the Mind’: An Inquiry into the Titling of Artworks. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity 3: 157–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friend, Stacie. 2007. Narrating the Truth (More or Less). In Knowing Art: Essays in Aesthetics and Epistemology. Edited by Matthew Kieran and Dominic McIver Lopes. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, David. 2015. Buch-Gewänder: Prachteinbände im Mittelalter. Berlin: Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz, David. 2019. Clothing Sacred Scriptures: Materiality and Aesthetics in Medieval Book Religions. In Clothing Sacred Scriptures: Book Art and Book Religion in Christian, Islamic, and Jewish Cultures. Edited by David Ganz and Barbara Schellewald. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gaut, Berys. 2003. Art and Knowledge. In The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics. Edited by Jerrold Levinson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 436–50. [Google Scholar]

- Gaut, Berys. 2007. Art, Emotion and Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, Gérard. 1987. Seuils. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Genette, Gérard. 1997. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Translated by Jane E. Lewin, and Richard Macksey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Nelson. 1977. When is Art? In The Arts and Cognition. Edited by David Perkins and Barbara Leondar. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, Nelson. 1978. Ways of Worldmaking. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Grafton, Anthony, and Megan Williams. 2006. Christianity and the Transformation of the Book: Origen, Eusebius, and the Library of Caesarea. London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Gordon. 2005. Philosophy of the Arts: An Introduction to Aesthetics, 3rd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gurry, Peter J. 2017. A Critical Examination of the Coherence-Based Genealogical Method in New Testament Textual Criticism. NTTSD 55. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, H. A. G., D. C. Parker, Peter Robinson, and Klaus Wachtel. 2020. The Editio Critica Maior of the Greek New Testament: Twenty Years of Digital Collaboration. Early Christianity 11: 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, Eileen. 1998. Fiction and Conceptual Knowledge: Philosophical Thought in Literary Context. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 64: 331–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, Eric R. 2016. Reductionism in Art and Brain Science: Bridging the Two Cultures. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karnetzki, Manfred. 1956. Textgeschichte als Überlieferungsgeschichte. ZNW 47: 170–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knust, Jennifer, and Tommy Wasserman. 2018. To Cast the First Stone: The Transmission of a Gospel Story. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzgefasste Liste. n.d. Available online: https://ntvmr.uni-muenster.de/liste (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Lamb, William R. S. 2012. The Catena in Marcum: A Byzantine Anthology of Early Commentary on Mark. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, Jerrold. 1985. Titles. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 44: 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lied, Liv Ingeborg, and Hugo Lundhaug, eds. 2017. Snapshots of Evolving Traditions: Jewish and Christian Manuscript Culture, Textual Fluidity, and New Philology. Berlin: de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- McGann, Jerome. 2001. Radiant Textuality: Literature after the World Wide Web. New York: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Judith S. 2016. The Manuscripts. In The Garima Gospels: Early Illuminated Gospel Books from Ethiopia. Edited by Judith S. McKenzie and Francis Watson. Oxford: Manar al-Athar, pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mink, Gerd. 2011. Contamination, Coherence, and Coincidence in Textual Transmission: The Coherence-Based Genealogical Method (CBGM) as a Complement and Corrective to Existing Approaches. In The Textual History of the Greek New Testament: Changing Views in Contemporary Research. TCS 8. Edited by Klaus Wachtel and Michael W. Holmes. Atlanta: SBL, pp. 141–216. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, Stephen G. 1990. Introduction: Philology in a Manuscript Culture. Speculum 65: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordenfalk, Carl. 1938. Die spätantiken Kanontafeln. 2 vols. Göteborg: Isacsons. [Google Scholar]

- Novitz, David. 1987. Knowledge, Fiction and Imagination. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 1990. Love’s Knowledge: Essays on Philosophy and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Plate, Brent. 2018. What the Book Arts Can Teach us about Sacred Texts: The Aesthetic Dimension of Scripture. In Sensing Sacred Texts. Edited by James W. Watts. Sheffield: Equinox, pp. 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Reuss, Joseph. 1941. Matthäus-, Markus- und Johannes-Katenen nach den handschriftlichen Quellen untersucht. Münster: Aschendorff. [Google Scholar]

- Roby, Courtney. 2017. Framing Technologies in Hero and Ptolemy. In The Frame in Classical Art: A Cultural History. Edited by Verity Platt and Michael Squire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 514–43. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Mark W. 2009. Literature, Knowledge, and the Aesthetic Attitude. Ratio 22: 375–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sickenberger, Joseph. 1901. Titus von Bostra: Studien zu dessen Lukashomilien. Leipzig: Hinrichs’sche. [Google Scholar]

- Sigismund, Marcus. 2020. Aus der laufenden Arbeit an der ECM der Apokalypse. In Studien zum Text der Apokalypse III. Edited by Marcus Sigismund, Darius Müller and Matthias Geigenfeind. Berlin: de Gruyter, pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Simotas, Panaiotis N. 1984. Νικήτα Σεΐδου Σύνοψις τῆς Ἁγίας Γραφῆς. Thessalonica: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders, Tjamke. 2015. Manuscript Communication: Visual and Textual Mechanics of Communication in Hagiographical Texts from the Southern Low Countries, 900–1200. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Tinio, Pablo P. L., and Jeffrey K. Smith, eds. 2014. The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Aesthetics and the Arts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, James. 2014. Philology: The Forgotten Origins of the Modern Humanities. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- von Soden, Hermann. 1902. Die Schriften des Neuen Testaments in ihrer ältesten erreichbaren Textgestalt hergestellt auf Grund ihrer Textgeschichte. 1 vol. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Wallraff, Martin. 2016. Paratexte der Bibel: Was Erasmus edierte außer dem Neuen Testament. In Basel 1516: Erasmus’ Edition of the New Testament. Edited by Martin Wallraff, Silvana Seidel Menchi and Kasper von Greyerz. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 145–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wallraff, Martin, and Patrick Andrist. 2015. Paratexts of the Bible: A New Research Project on Greek Textual Transmission. Early Christianity 6: 237–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Dorothy. 1969. Literature and Knowledge. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Winner, Ellen. 2019. How Art Works: A Psychological Exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | See (Nichols 1990; Cerquiglini 1989; Chartier 1995). Of course, critical attention to manuscripts along these lines also runs much deeper in the tradition, finding parallels in Renaissance and ancient textual scholarship. See (Turner 2014, part I). |

| 2 | This is not to say that classical text critical approaches that emphasize textual reconstruction are illegitimate exercises. They remain foundational textual activities, and there is much work to be done on understanding the origins, early transmission, and textual history of many ancient works, not least the New Testament. |

| 3 | For a catalogue of Greek New Testament manuscripts, see the digital Kurzgefasste Liste (n.d.) on the New Testament Virtual Manuscript Room. |

| 4 | A good example is the work on the pericope adulterae in (Knust and Wasserman 2018). Additionally, the Editio Critica Maior (ECM) fascicle for the book of Revelation takes into account a selection of manuscripts features specific to the tradition, embedding these features in the underlying extensible markup language (XML) of their digital transcription. For example, they encode the kephalaia of the Andrew of Caesarea commentary tradition, punctuation, accentuation traditions of some words that affect their morphology, and other marginalia. On their transcribing processes see (Sigismund 2020). |

| 5 | This abstraction is an explicit part of the text genetic eclectic method used to evaluate variation units for the production of the ECM. The approach is called the Coherence-Based Genealogical Method. See (Mink 2011; Gurry 2017). |

| 6 | This is how (Wallraff and Andrist 2015) define paratexts in their project that focuses on paratexts of the gospels: “all contents in biblical manuscripts except the biblical texts itself are a priori paratexts” (here p. 239). This definition has been fine-tuned in (Andrist 2018). |

| 7 | Gérard Genette, who provided the first descriptive taxonomy of paratexts using early modern printed French novels as a data set, even included items like author’s correspondence and interviews as forms of paratexts, items outside the book that he referred to epitexts. See especially (Genette 1987 (trans. Genette 1997)). On the usefulness of Genette’s taxonomy for ancient and medieval Greek manuscripts, see (Andrist 2018; Allen 2019, pp. 602–4; Crawford 2019, pp. 21–28). For discussion on the significance of material aspects of medieval manuscripts, especially their covers, see (Ganz 2015). |

| 8 | While aesthetic cognitivists emphasize the cognitive value of art, it is not the only possible measure of a work. Beauty, entertainment, and emotional expression continue to function as important aspects of a work’s evaluation. We do not want to reduce aesthetics to cognitive functions, but to highlight a common sense view that we often esteem artworks if we learn something from them. This approach is encapsulated well in the structure of (Graham 2005). |

| 9 | In some strands of aesthetic cognitivism, art is even placed on par with the sciences as modes of knowledge making. For example, see (Goodman 1978, p. 102): “the arts must be taken no less seriously than the sciences as modes of discovery, creation, and enlargement of knowledge in the broad sense of advancement of the understanding.” |

| 10 | Baumberger (2013) goes on to say that “understanding is holistic. Knowledge can be broken down into discrete bits” (p. 50) and that “striving for understanding is considerably more ambitious than acquiring knowledge.” See also (Elgin 2002), for whom understanding is defined by the assimilation and reorganization of new knowledge into large domains, especially when our preexisting systems are not ready to receive such information. |

| 11 | Two good examples of this type of research in the arts and psychology are (Winner 2019; Tinio and Smith 2014). Neuroaesthetics is also a burgeoning field that engages in discussions around aesthetic cognitivism and brain science, (e.g., Chatterjee 2014; Kandel 2016). |

| 12 | The images are also available on the Chester Beatty Online Collections (n.d.). |

| 13 | Each item in Table 1 not in bold print is a prefatory paratext of the gospels of one kind or another. |

| 14 | For a codicological taxonomy of paratexts in Greek gospel manuscripts see (Andrist 2018). |

| 15 | Anonymous, but attributed to Irenaeus in Athos, Iviron 56 (GA 1006). It is preserved also in Nicetas Seides’ Conspectus librorum sacrorum. See (Simotas 1984, pp. 272–73). |

| 16 | Preserved also in Nicetas Seides, Conspectus librorum sacrorum (Simotas 1984, p. 273). |

| 17 | Text preserved in (Cramer 1844, pp. 1.263–65). |

| 18 | An abbreviated form is catalogued in (von Soden 1902, p. 306). |

| 19 | Text preserved in Nicetas Seides, Conspectus librorum sacrorum (Simotas 1984, p. 273). |

| 20 | See (Sickenberger 1901, p. 143). |

| 21 | See (von Soden 1902, p. 306). |

| 22 | All images of CBL W 139 © The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. |

| 23 | From left to right the tabs are as follows: [B] Breaks, [C] Corrections, [D] Deficiency (damaged or difficult to read text), [O] Ornamentation, [A] Abbreviated text, [M] Marginalia, [N] Notes, [P] Punctuation, and [V] Verse Modify (change numbering for book, chapter, and/or verse). |

| 24 | Other marginal comments are attached to the liturgical apparatus, including introductory sentences from the lector. For example, on 40r the start of a new lection at Matt 5:20, a text addressed to Jesus’ disciples, we read in the left margin “[as] the Lord himself said to the disciples”. |

| 25 | Reuss (1941) created taxonomy for gospel catena traditions, but his categorization does not account for the fluidity of the tradition. Lamb (2012, pp. 58–64) prefers to see the gospel catena traditions as “open books.” |

| 26 | The apparatus is ubiquitous, influencing even the shape of early print editions. See (Wallraff 2016). |

| 27 | The Letter’s Greek text can be found in Nestle-Aland28, 89*–90* and a recent English translation can be found in (Crawford 2019, pp. 295–96). I quote from Crawford’s translation. The versional witnesses to the letter differ sometimes substantially from the Greek text. See, for example, the Ethiopic and Greek version translated side by side by Francis Watson in (McKenzie 2016, pp. 221–27). |

| 28 | On Ammonius and his work see (Crawford 2015; Grafton and Williams 2006, pp. 29–32). |

| 29 | Matthew has 355 sections; Mark 233; Luke 342; and John 232. |

| 30 | This section in John is 98 in the edition of the canon in Nestle-Aland28, p. 92*. |

| 31 | The critical edition of this canon in Nestle-Aland28 (p. 92*) lists section 321 in Matthew once (//§201 Mark//§192 John). |

| 32 | Many codices preserve only parts of the system, sometime only the marginal notations, lacking canon tables and/or the Letter to Carpianus. |

| 33 | See (Crawford 2019, pp. 112–19), which includes a number of case studies that argue for the theological significance of the system’s juxtapositions. |

| 34 | This is similar to Graham’s definition of aesthetic cognitivism (Graham 2005, p. 71): it is “the belief that art can illuminate experience by making us more aware of it contains.” In other words, life imitates art. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).