2. Functions of Religion from Sociological Perspectives

One of the major contributions made by classic sociologists to the study of religion resides in theories that shaped and developed the functions of religion approach. The way in which these functions were identified and conceptualised differed within the context of differing sociological frameworks. For example, Durkheim underlined the importance of collective religious practices related to symbolisation of social life. In his classical definition:

A religion is a solidary-system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single community of custom called a Church, all those who adhere to them.

Durkheim’s sacred things became the representation of social solidarity. The “plexus” of sacred and profane retains a significant sociological interest, opening up the possibility to reconsider the meaning of the sacred things in a concrete society. Whether sacred things of contemporary religions are related to purely religious symbols and myths, or whether they can keep relevance to specific sociopolitical ideals of modernity together with the religious ones has been widely discussed by sociologists who focused their analysis on religion and secularisation from the 1960s.

Later sociological responses to Durkheim’s definition of the function of

sacred things can be found in the theoretical perspective of social constructivism. It emphasised that the process of production of

finite provinces of meaning is endemic to religion (

Berger and Luckmann 1966). With its rootedness in the system of ultimate meaning, religion showed the potential to provide the sense of purpose to the individual life as well as the meaning to social order. In his last work, Berger explained that the freedom to search for a meaningful or meaning-engendering mystery of life is a fundamental human right (

Berger 2014), thus establishing the connection between production of the meaning and search for it. This connection was considered by sociologists of religion with subjective pathways in quests for the sacred, linked to the freedom of choice of the individual and quest for a meaning for existence in terms of personal well-being, in harmony with one’s “deep self” that needs to be expressed (

Giordan 2009). These experiences were described with antithetical, competing, or complementary linkages between religion and spirituality revealing a variety of new individual ways of searching for the sacred (

Ammerman 2013;

Aupers and Houtman 2010;

Flanagan and Jupp 2007;

Roof 2003).

At the level of society, the function of producing collective meaning by religion was reconsidered with discourses on deprivatisation of religion (

Casanova 1994) and debates on structural transformations of the public sphere and public religion developed by

Jürgen Habermas (

2006). The ways in which religion could influence public opinion or intervene in social affairs were contested by scholars at the level of religious and political institutions, leaving for religious and nonreligious citizens equal possibilities for participating in “complementary ‘learning processes’” (

Habermas 2006). New engagement of religion with the public sphere was conceptualised through the potential of religion not to leave individual citizens with their private interests without a sense of a common value system and trust in the project of modernity.

Globalisation of religion (

Beyer 2006) has challenged the very concept of “single community of custom” which in Durkheim’s perspective can be seen not only as Church, but also as a social group united by common values. Globalisation of religion questions the way religious and national identities produce markers of inclusion and exclusion in society, sacred and nation-state boundaries of the communities. As James Dingley argued, “Not only does religion take us into the multifaceted nature of national identity, such as sociolinguistics, social relations, morality and truth, but also concepts of identity take us back into a reconsideration of the role, nature and function of religion” (

Dingley 2011, p. 401). Starting from the Weberian idea about the juncture of values in religious and national cultures (

Weber [1905] 1930) and coming to the modern understanding of the role of religion in producing important markers of identity and social difference (

Kastoryano and Schader 2014), the process of designating imagined boundaries of belonging raises new questions to the functionalist perspective.

How does religion function as a social integration source in multicultural societies? How does the role of religion change in providing meaning for public order in a society where human rights have established the possibility to change religion? Social dynamics and new conjunctions of functions of religion within a particular sociopolitical context have suggested new lenses for functionalists—to look for a new relevance of religion to social challenges beyond the sociological perspective. The study of functions of religion becomes a new interdisciplinary exercise, providing a method of analysis for the relevance of

sacred things to the ideals of the “sacredness of person” (

Joas 2013) and liberal societies, such as individual freedoms and rights.

3. Applying Perceptions of the Functions of Religion within Contemporary Scientific Research

While classical sociologists developed functional theories of religion as the tradition of analysis of long-lasting impact of institutional religion on social, economic, legal processes, and structures (

Lidz 2010, p. 76), application of social constructivism to the analysis of the role of religion within a wider social–scientific study of religion highlighted the problem in adopting “a definition of religion in which religion is whatever serves one’s ultimate concern” (

Schilbrack 2012, p. 108). The latter approach, by questioning religion as a social construct (

Berger and Luckmann 1966;

Fitzgerald 1997;

Smith 1998), suggested an ongoing debate on the meaning of religious phenomena, importance of social context, and centrality of the subject in the process of its constructing.

Empirical research concerned with identifying individual differences in the effect religion on contemporary issues of social or personal concern has employed a range of theoretical perspectives. For example, the research literature on the connections between religion and human rights-related issues (

Van der Ven and Ziebertz 2013;

Francis et al. 2020) has widely applied the social representation approach of

Staerklé et al. (

1998) by explaining how different modes of thinking about human rights could exist depending on the socioreligious context. Empirical studies on religion and human have conceptualised individual differences in religion in terms of:

Self-assigned religious affiliation (e.g., Christian or Muslim);

Public engagement in religious practices (e.g., worship attendance);

Personal engagement in religious practices (e.g., prayer);

Religious affect (e.g., attitude toward religion);

Religious orientation (e.g., intrinsic religiosity).

Several functions of religion have been targeted by the study of religion and human rights (

Ziebertz and Sterkens 2018), such as public role of religion, conformity of religion to cultural trends, spiritual service, and the role of religion in social change. However, less prominent in this developing literature have been individual differences in the perceptions of the functions of religion. This lacuna may, at least partly, be attributable to lack of easily accessible measures available for assessing perceptions of the functions of religion. In order to address this lacuna, we began the process of developing a new measure of the functions of religions by drawing up a conceptual map of the various functions identified within the relevant literature and by searching for indicators of these functions already utilised within existing empirical studies.

As the first step, based on our literature review, we identified the following 11 core functions of religion, all of which have strong reference to current sociological and wider social scientific debates on changing and intersecting roles of religion in modern societies with the further empirical verification of developed operational definitions.

Service for marginalised;

Peacebuilding and interfaith/humanitarian dialogue;

Spiritual guidance;

Active public role;

Maintaining belief and collective experiences;

Moral guidance;

Modernisation force;

Source for national and cultural identity;

Signification (providing meaning of individual life and social order);

Providing social belonging;

Religious freedom advancement.

As the second step, we drew on individual items that had already been tested in crossnational studies, for instance, in the questionnaire of “Human rights and Religion” (

Van der Ven and Ziebertz 2012) and in the questionnaire submitted in postcommunist countries within the Aufbruch research project (

Tomka and Zulehner 2007). We then augmented this pool of items in order to offer two or three items to exemplify each of the 11 functions of religion. This full set of 30 items is set out in

Appendix A.

As the third step, we designed an original survey in order both to test our developing conceptualisation of the functions of religion and to deploy this conceptualisation for generating new knowledge concerning individual differences in attitude toward religious freedom. In order to test our developing conceptualisation of the functions of religion, we employed factor analysis to explore potential overlaps among the 11 areas initially identified. In order to deploy the outcome of this factor analysis, we employed regression analysis to test the effectiveness of these new measures of the perceptions of the functions of religion in predicting individual differences in attitudes toward the specific human rights issue concerning freedom of religion.

5. Results

The first step in data analysis examined how well the 11 sets of two or three items functioned as short scales, employing Cronbach’s alpha (

Cronbach 1951). The data presented in

Table 1 demonstrate that 9 of the 11 sets of items achieved alpha coefficients in excess of 0.65, a good result for such short measures. The two scales reporting less satisfactory levels of internal consistency reliability were the measures of source for national and cultural identity, and social identity and belonging.

Table 1 also presents the mean scores for these 11 scales.

Only 1 of these 11 scales recorded a mean value lower than the midpoint of the scale (3.00): The measure of active public role recorded a mean score of 2.95. This negative valence can be interpreted as indicating that young people care less about the societal role of religion in general but consider religion important for individual religious and spiritual needs or in specific spheres of social life (promoting tolerance and social dialogue).

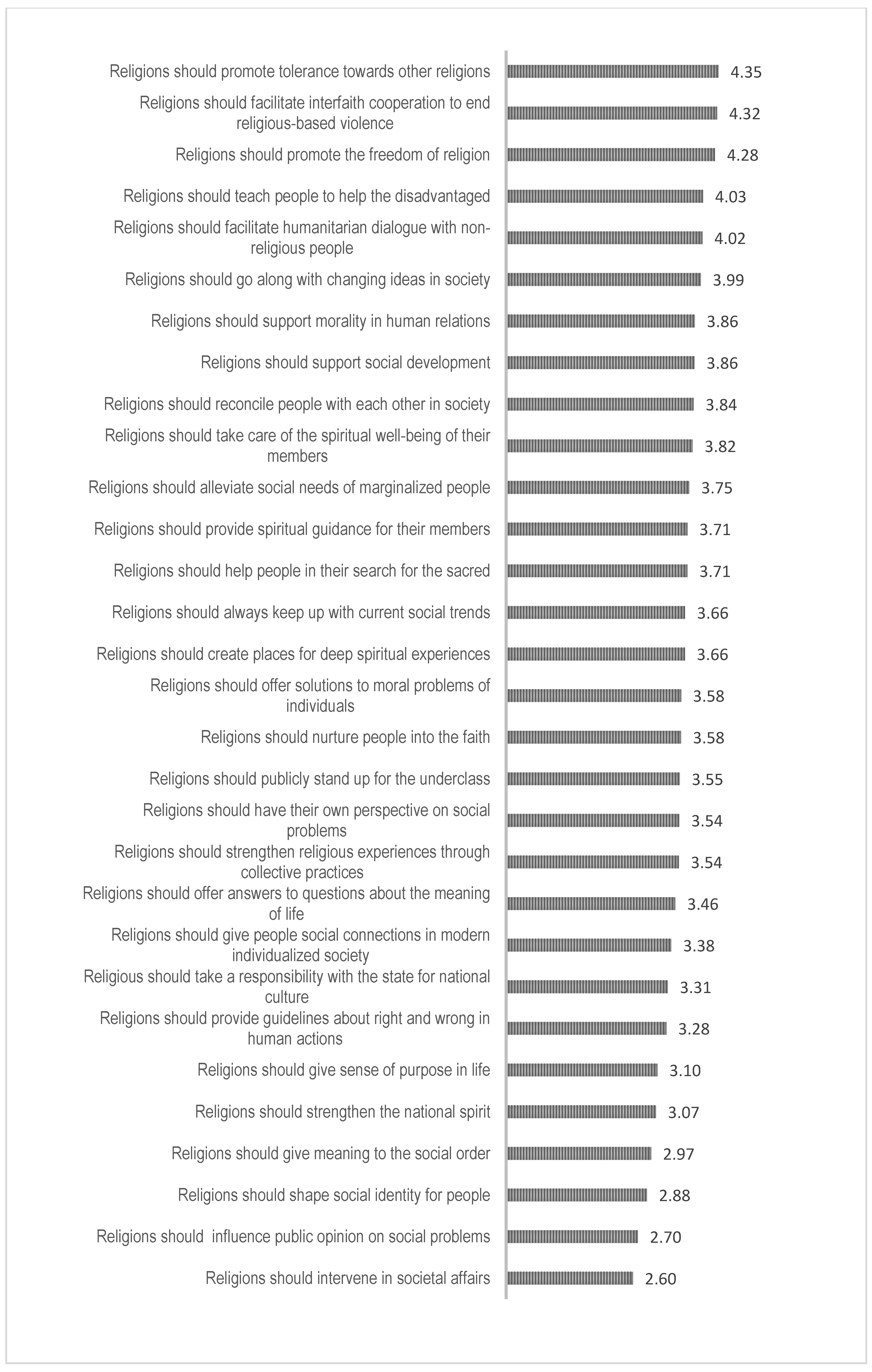

The second step in data analysis examined the level of endorsement given to each of the 30 items individually.

Figure 1 presents these items in rank order from the item that attracted the highest level of endorsement (religions should promote tolerance toward other religions, mean = 4.35) to the items that attracted the lowest level of endorsement (religions should intervene in social affairs, mean = 2.60). In interpreting these mean scores, we rely on the following rule: 1.00–1.79 = disagree totally; 1.80–2.59 = disagree; 2.60–2.99 = negative valence; 3.00–3.39 = positive valence; 3.40–4.19 = agree; 4.20–5.00 = agree totally. According to these criteria, total agreement (4.20 ≤ M ≥ 5.0) by young people with three items, two of which measure the function of religion in “religious freedom advancement” and one is part of the scale “peacebuilding and interfaith/humanitarian dialogue”, inform us about the primary perception of religion through its relevance to citizenship rights and sociopolitical values such as tolerance and nonviolence.

Agreement (3.40 ≤ M ≥ 4.19) was expressed with 18 statements about the functions of religion. They covered a variety of meanings and activities which link religion with “service for marginalised” (3 items), “peacebuilding and interfaith dialogue” (2 items), “spiritual guidance” (3 items), “active public role” (1 item), “maintaining belief and collective experiences” (3 items), “moral guidance” (2 items), “modernisation force” (3 items), and “signification” (1 item).

It was interesting to observe that the statement “religions should take care of the spiritual development of their members” (M = 3.82), which was operationalised to measure the relevance of religion in providing “spiritual guidance”, was the tenth most important in the list. The first nine statements indicated the importance of religion in the sociopolitical sphere and even the overlapping of functions of religion with the functions of the state. For instance, both the “religions should promote tolerance towards other religions” (M = 4.35) and “religions should promote the freedom of religion” (M = 4.28) statement underline the value of religious freedom, which a democratic state has an obligation to guarantee. This finding can bring some evidence that for the young people in the Italian sample, religion associated with the dominant Catholic Church can have reference to the autonomous institution which today has public visibility in human rights advancement. For instance, the Catholic Church in Italy provided a response to the migration crisis with practices towards welcoming migrants and refugees (

Giordan and Zrinščak 2018).

With positive valence (3.00 ≤ M ≥ 3.39), the participants assessed five items, three of which were related to the relevance of religion in constructing national and cultural identities and providing resources for social belonging. With negative valence (2.60 ≤ M ≥ 2.99), four items of “functions of religion” were assessed, two of which cover the “active public role” of religion and one aims at measuring religion’s role in “providing social belonging”.

The analysis of scores of the means allows us to conclude that the functions of religion performed at the level of society were depicted at the top and the bottom of this list of 30 items. At the same time, functions that religion performs for the individual such as “spiritual guidance” or “maintaining belief and collective experiences” were placed by the participants at the middle of this list. The scores of the means for these scales ranged within the values 3.82 ≤ M ≥ 3.54, which signify an agreement with six individual items from those two scales.

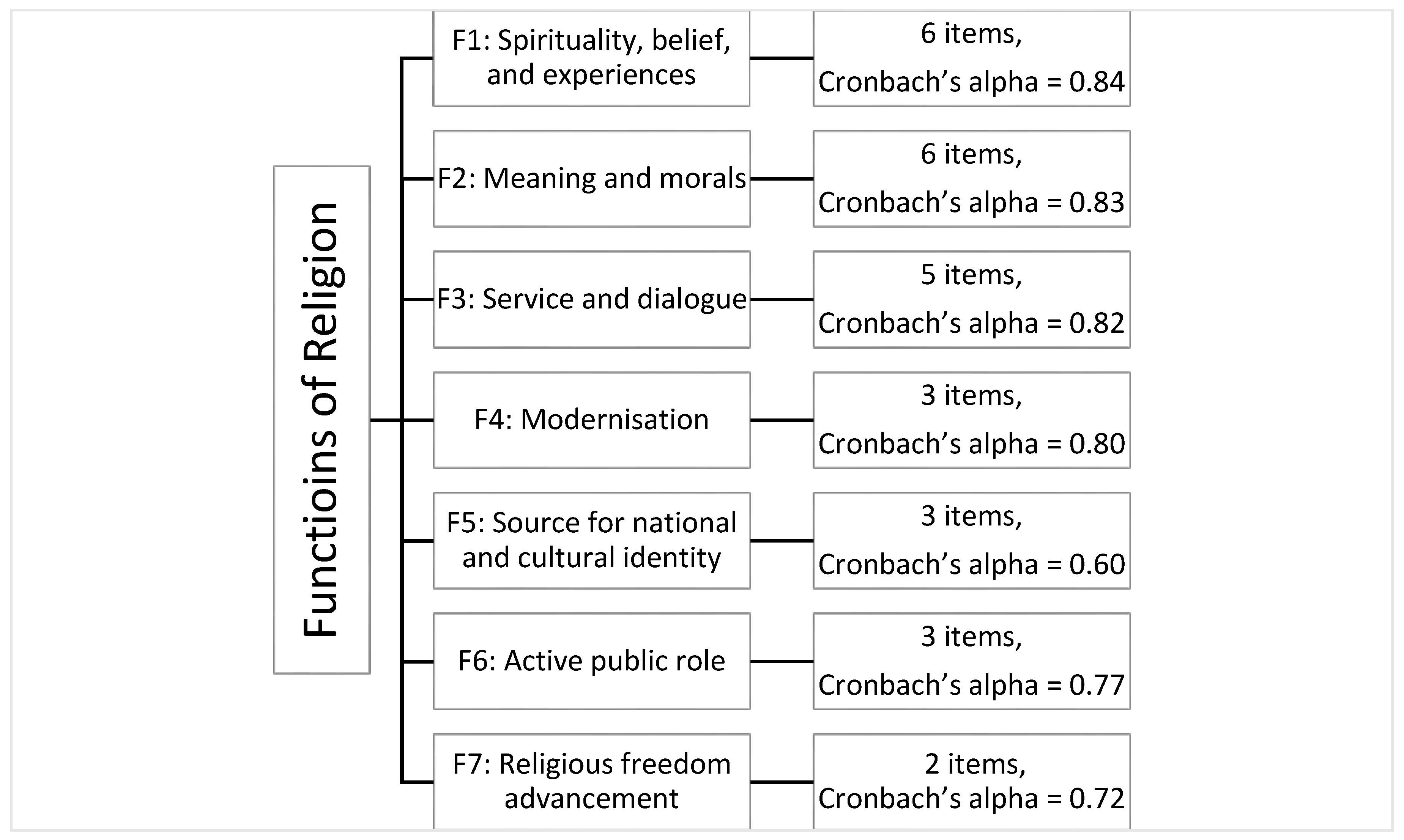

The third step in data analysis employed exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with the principal component method of extraction and Varimax rotation for 30 items of the concept “functions of religion” with the aim of developing the NIFoR. We were also interested in understanding how the theoretically constructed functions for the individual and society can overlap in the empirical model. By defining the latent factors and testing strong and weak theoretical scales for NIFoR, we were interested in exploring the patterns of overlapping functions. Thus, we put the 11 scales together with the aim of reducing the number of items in NIFoR and targeting the theoretical core of the dependent variable.

In the model of EFA, we considered the eigenvalues and controlled for the reliability of latent factors. We used a value of 0.50 as the minimum threshold acceptable for the eigenvalues and a value of 0.60 as the minimum threshold acceptable for Cronbach’s alpha. We analysed whether the value of the alpha increases consistently by deleting an item in order to have a model with fewer parameters and, above all, because that item did not adequately correlate with the rest of the scale. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy indicated that the strength of the relationships among variables was high (KMO = 0.90); thus, it was acceptable to proceed with the analysis. The EFA retrieved seven factors (

Table 2) with only one variable which had an eigenvalue below 0.50 (eigenvalue = 0.46), and it was extracted in the first factor. Thus, we decided not to consider it for further analysis and constructing of NIFoR.

In the process of verifying the identified scales, we discovered that the item “religions should facilitate interfaith cooperation to end religion-based violence” from the scale “peacebuilding and interfaith/humanitarian dialogue” merged with the items from the scale “religious freedom advancement”. The reliability of this latent factor (Factor 4) is acceptable (alpha = 0.80). However, we considered that it would be better to delete this individual item from the scale comprising Factor 4, since reliability would increase (alpha = 0.86) with the deletion of this item.

Another observation is that Factor 5 grouped two items from the scale “source for national and cultural identity” and one item from the scale “providing social belonging”. The internal consistency of the scale is questionable (alpha = 0.60), and we decided to keep all items together, even though the reliability of the latent factor will increase only slightly with the deletion of this item (alpha = 0.61)

1.

After processing the exploratory factor analysis, we observed that most of the individual items that constructed theoretical scales were extracted accordingly and were found in the same factor. Three factors from seven grouped two functions, showing through that several overlapping functions of religion. Since we excluded several items from the model, we repeated the EFA again. The results showed that the order of factors changed but not the variables, which constitute the factors. Thus, we describe which kind of latent factors appeared in the empirical model.

The data showed that the function of religion known as “moral guidance” was extracted together with the function of “signification”, which is to provide meaning for individual life and social order. This result tells us that, for our participants, the meaning constructed by religion has relevance to moral values. Thus, we named this latent factor “meaning and morals”. The role of religion as “spiritual guidance” was retrieved together with the function of religion “maintaining belief and collective experiences”. We named this latent function “spirituality, belief, and experiences”. Two more functions were extracted together: “service for marginalised” and “peacebuilding and interfaith dialogue”. We called this latent factor “service and dialogue”.

Applying the principal component method with Varimax rotation for the second EFA, we still observed seven retrieved factors. We conducted the same analysis with the fixed number of factors. Even if the order of the factors changed slightly, bringing to the top of the list the function of religion “spirituality, belief, and experiences” (

Figure 2), the composition of items in the factors remained the same. This measurement model was balanced between theoretical concepts and empirical evidence we called

New Indices of the Functions of Religion.

The first factor was robust and accounted for 27.1% of the variance in the data. “Meaning and morals” was loaded as a second factor and accounted for a further 11.5% of the variance. The third and the fourth factors explained 6.8% and 6.1% of the variance, respectfully. The remaining three factors accounted for 12.9% of the variance (

Figure 2).

The fourth step in data analysis employed multiple regression in order to explore the effect of the seven scales proposed by the New Indices of the Functions of Religion (NIFoR) on scores recorded on the Social Perception of Religious Freedom (SPRF) index, while also taking into account the effect of age, gender, citizenship, and religious belonging. The four linear regression models with the enter method are presented in

Table 3.

We considered the results separately for the general sample, for religious minorities, Catholics, and religious nones. The first interesting observation is that two functions of religion from seven (function of religion as “modernisation force” and providing a “source for national and cultural identity”) had no effect on the SPRF index.

The second observation regards the fact that all regression models reported the positive effect of the function “meaning and morals” on the SPRF index, and this effect was greater for religious minorities (beta = 0.54). Third, for Catholic participants, more functions had predictive power vis-à-vis the SPRF index than for the other two groups. Fourth, for religious nones, the functions “religious freedom advancement” (beta = 0.25), “active public role” of religion (beta = 0.17), and “meaning and morals” (beta = 0.16) had significant statistical influence on the SPRF index, while for religious minorities, only one function was salient in this model. This analysis also documents the absence of predictive power of sociodemographic characteristics in this model.

6. Conclusions

The social scientific study of the relevance of religion to modern conditions of individual life and institutional change is developing within the functionalist and social constructivist perspectives. Together with the classical study of functions of religion in producing individual and collective meanings or being a source of solidarity and identity, this approach emphasises the roles that religion performs in constructing the normative frameworks and cultural values of religious freedom in the contexts of growing intolerance (

Nussbaum 2012), increasing religious restrictions (

Fox 2015) or modern challenges of equal citizenship (

Modood and Kastoryano 2007). This study aimed to gather empirical evidence on the relevance of eleven conceptually distinct functions of religion for young people in the sample we constructed in Italy. We set out to test three hypotheses and introduce the New Indices of the Functions of Religion (NIFoR).

We started with the aim of exploring the structure of the concept “functions of religion” and verifying the hypothesis that functions linked to values of tolerance, interfaith dialogue, and support to the disadvantaged and the marginalised had better predictive power in respect of attitude towards religious freedom. In developing the NIFoR, we observed from the results of exploratory factor analysis that the first two extracted factors were related to the role of religion in providing guidance in individual spiritual well-being, religious meaning for individual lives, and social order with strong linkage to moral solutions and values.

The structure of the NIFoR revealed interesting details: The ideas of individual spiritual well-being, collective religious practices, and quest for the

sacred were merging without opposing religious and spiritual domains. That finding was recently demonstrated by a sociopsychological study of spiritual profiles of young Italians (

Giordan et al. 2018).

However, the results of regression analysis showed that the functions of “service and dialogue” and “religious freedom advancement” were strong predictors of the positive perception of religious freedom in society. Thus, the first hypothesis (H1) was proven. The more young people considered religions to be responsible for promoting ideas of tolerance, interfaith dialogue, and religious freedom, the more strongly they supported the suggested principles of religious freedom in the SPRF index. This finding offered some important arguments to the transformative theory of religious freedom of

Brettschneider (

2010) by showing that together with the state, religion and individual citizens (both religious and nonreligious) have the potential to transform and promote the culture of religious freedom in society.

The second aim was to understand if those functions of religion which assisted an individual in achieving spiritual well-being and their search for sacred had predictive power vis-à-vis positive perception of religious freedom (H2). We can conclude that for the general sample, this hypothesis was proven; however, if we look for group differences, we can confirm that the function “spirituality, belief, and experiences” was relevant only for Catholics (beta = 0.16) in our model.

Third, we examined intergroup differences between the religious majority, religious minorities, and nonreligious groups in their sensitivity towards various functions of religion and, consequently, positive perception of religious freedom. The data confirm that religious minorities endorsed only the importance of religion in promoting “meaning and morals”, while the rest of the functions had no influence on the dependent variable for this group. At the same time, for religious nones, the “active public role” of religion was more significant (beta = 0.17) than for religious minorities. This finding offers some implications for the understanding of attitudes and values of nonreligious young people in the context of Italian political secularism, in which the presence of religion in the public arena remains strong and thus relevant to current political debates. Another finding about the differences between groups concerns the fact that religious nones, compared to other groups, considered the function of “religious freedom advancement” to be the most important for the SPRF index (beta = 0.25). Thus, the third hypothesis (H3) was proven, as the statistically significant influence of belonging to religious minorities in comparison with Catholics was observed (in four cases) and between religious minorities and nones (in two cases).

The observed difference produced by religious identities of the participants (as conceptualised and operationalised by self-assigned religious affiliation) on the various functions of religion shed a light on the relationship between religious identity and perception of the role that religion performs in public and private domains. While for the purposes of testing the NIFoR, we considered self-assigned religious affiliation an important aspect of social identity that has encased within it religious significance (

Fane 1999), it will be important to include other dimensions of religiosity/spirituality in future experimental models designed to generate further insight into the predictive power of the NIFoR. Since the data generated by the SPRF survey included measuring religiosity and spirituality at the dimensions of religious belief, practice, socialisation, and education, further analyses are intended to explore the links between the functions of religion and these aspects of individual religiosity.

Already in the present analysis of the impact of the NIFoR on the SPRF index, some very important dimensions of the very concept of religion have become more transparent. The linkage between perception of the functions of religion, religious identity, and attitudes towards religious freedom uncovers the centrality of five intersecting spheres of religious presence in the everyday life of young Italians. This is a religion which (1) advances the values of tolerance, (2) provides social service and fosters interfaith dialogue, (3) gives significance and moral dimensions to life, (4) articulates its position in the public square, and (5) is a source of spirituality, belief, and experiences.

The association between religious freedom and five distinct functions of religion for the general sample with predominantly Catholic participants and only one function for the sample of religious minorities raises the issue of the meaning of religion and its functions in a specific national context. For the Italian youth, the tension between religious identity and religion can be described in terms of “individual choice, freedom, and direct experience of reality, with the attempt of reinterpretation and domestication of religious sphere” (

Giordan and Sbalchiero 2020, p. 78—our translation) or individualisation of lifestyles (

Berzano 2019). This observation can be useful in understanding why religion in the analysed sample was as significant as the source for the meaning of life for the majority and minority religious identities as well as for nones. Moreover, it assists towards an understanding of why other functions, which require more institutionalised religious forms (for instance, in providing social service or participation in public life) are not equally significant for the three groups of participants with various identities if associated with religious freedom.

The validation of the theoretical concept NIFoR confirmed that two scales of “modernisation force” and “source for national and cultural identity” had no impact on the dependent variable. Thus, further research would be useful for the replication of the results of our study and validation of the NIFoR in their sensitivity and relevance to other civil–political and economic rights or advancement of political ideals of equal citizenship.