Religious/Spiritual Referrals in Hospice and Palliative Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

“It [religious literacy] is a metaphor connected to the ability to read and write; like reading and writing, literacy in religion is about an understanding of the grammars, rules, vocabularies and narratives underpinning religions and beliefs”.

2. Methodology

3. Findings

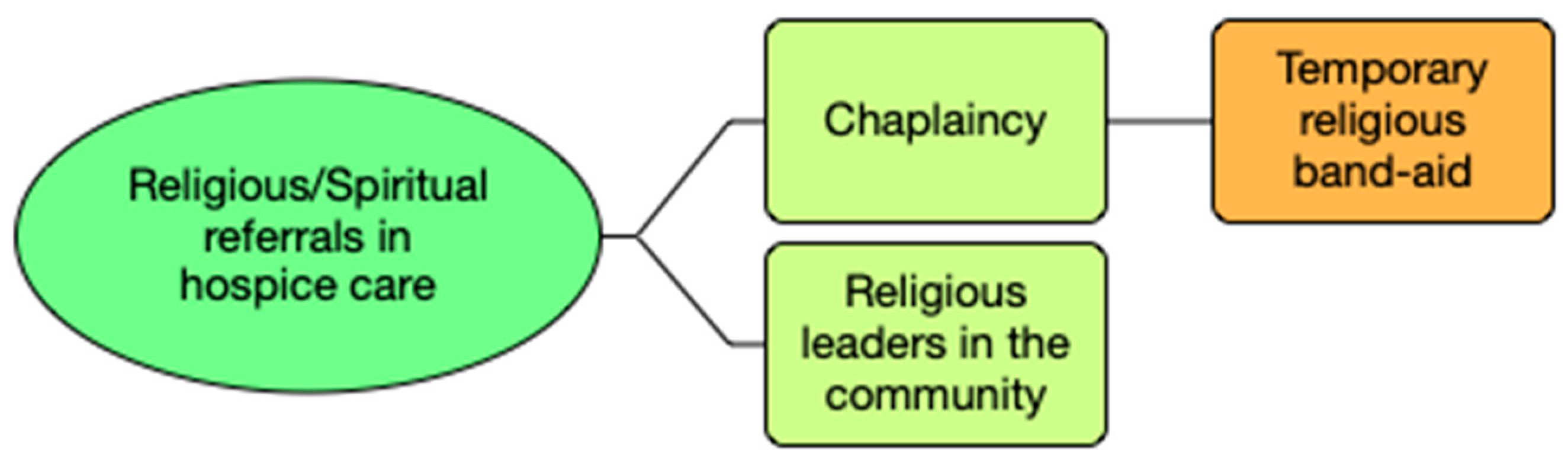

3.1. Referral to the Chaplaincy

We have got a spiritual care coordinator within our hospice, who facilitates our chaplaincy team and, therefore, a variety of different religious denominations, and actually non-religious denominations as well. So, there is a group of them [chaplaincy staff] that provide spiritual care that is done in a holistic way.(nurse, Christian)

When someone says they have religious or spiritual concerns, I tell the priest to go talk to them. It is a matter of fact as I am concerned.(counsellor, non-religious)

They have a chaplaincy here. And they have a Roman Catholic and a Church of England on staff. They also have other people—a list of people that are called in and it is led by one of the nuns.(doctor, non-religious)

I suppose the other belief is I do not know whether there is a God or not. So, once with a patient, I said, is it important to you that you find out [about God’s existence] or [are] you happy with where you are at the moment? If you want to talk about it, I can find someone to come and talk to you.(doctor, atheist)

If it is a question about faith and the meaning of life or afterlife, I am happy to offer the minister of the religion that they [patient] follow to come in and provide this service.(doctor, Christian)

Equally, if I had no understanding of a particular person’s request, then I would try and find an Imam, a Rabbi, somebody who perhaps know their faith. To try and support them in whatever they need in expression.(social worker, atheist)

We ask them, ‘shall we send the chaplain?’ And sometimes we send an Imam or someone else, almost like a substitute chaplain.(nurse, Muslim)

And I always feel that calling the chaplain is a bit like calling a psychologist. It is, you know, they [patients and family] are emotional; it is a bit messy. We need to call somebody in to stop that happening, so that we do not have to deal with it.(social worker, non-religious)

While the Catholic priest is in on Thursday, but that patient may be dying on Tuesday night, so we have to get the priest in for Tuesday night. So, there is that person, because that is what is important to him [patient].(nurse, Christian)

3.1.1. Impromptu Visits from the Chaplain

Well, chaplains [will come]. Someone from the chaplaincy team [is] here every day. They will interact with people [patients and family members].(doctor, non-religious)

The chaplaincy team is part of the permanent establishment and it is there [in the hospice]. And will actually proactively spend their time in the building, going around, offering company. They are available to the people and particularly being able to help people performing their ritual or whatever they want to do. And they will sit in the coffee bar and they are the ones that when someone starts to cry or something they will probably go over there; they want to approach and offer a form of support.(nurse, Christian)

3.1.2. Avoidance

So, obviously, I direct people to the chapel and the chaplaincy team, and I often say to people that even if they do not believe, they are very welcome in the chapel to also speak with someone if they need to.(doctor, Christian)

3.2. Referral to Religious Leaders in the Community

We also have contact with leaders of religious groups within the local area, who can come and facilitate religious ceremonies for patients, if that is unable to be provided by the chaplaincy teams.(nurse, Christian)

Alternatively [when chaplains are unavailable], there are people within the community who are able to be called upon and come in and run last rites and do whatever they have to do.(counsellor, non-religious)

3.3. Religious/Spiritual Referral and Homogenisation

After a while, it became quite apparent that what she needed was somebody who she could identify with on a religious level. So, she had spiritual distress, but she made sense of it through her religion, and what she actually needed was a priest.(nurse, Christian)

4. Discussion

4.1. Homogenisation of Religion/Spirituality

4.2. Avoidance of Conversations and Coping Strategy

4.3. Religious and Spiritual Struggles

5. Limitations of This Study

6. Implications for Practice and Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abu-Raiya, Hisham, Kenneth I. Pargament, and Julie J. Exline. 2015. Understanding and addressing religious and spiritual struggles in health care. Health & Social Care 40: e126–e134. [Google Scholar]

- Annelieke, Damen, Dirk Labuschagne, Laura Fosler, Sean O’Mohanoy, Stacie Levine, and George Fitchett. 2019. What do Chaplains Do: The Views of Palliative Care Physicians, Nurses, and Social Workers. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine 36: 396–401. [Google Scholar]

- Bay, Paul S., Daniel Beckman, James Trippi, Richard Gunderman, and Colin Terry. 2008. The effect of pastoral care services on anxiety, depression, hope, religious coping, and religious problem solving styles: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Religion and Health 47: 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazeley, Patricia, and Kristi Jackson. 2019. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bellah, Robert N. 1976. To kill and survive or to die and become: The active life and the contemplative life as ways of being adult. Daedalus 105: 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bidwell, Duane R. 2018. When One Religion isn’t Enough: The Lives of Spiritually Fluid People. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Anthony, and Kathleen Duffy. 2019. Understanding the role of chaplains in supporting patients and healthcare staff. Nursing Standard 34: 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryman, Alan. 2016. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dinham, Adam, and Martha Shaw. 2017. Religious literacy through religious education: The future of teaching and learning about religion and belief. Religions 8: 119–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinham, Adam, and Matthew Francis, eds. 2015. Religious Literacy in Policy and Practice. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, David. 2005. Cicely Saunders: Founder of the Hospice Movement: Selected Letters 1959–1999. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, David. 2000. Total pain: The work of Cicely Saunders and the hospice movement. American Pain Society Bulletin 10: 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Coble, Richard. 2017. The Chaplain’s Presence and Medical Power: Rethinking Loss in the Hospital System. New York: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Dan, Michael Aherne, and José Pereira. 2010. The competencies required by professional hospice palliative care spiritual care providers. Journal of Palliative Medicine 13: 869–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Douglas. 2017. Death, Ritual and Belief: The Rhetoric of Funerary Rites. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue, Pamela K., Matt Norvell, Renee Boss D., Jennifer Shepard, Karen Frank, Christina Patron, and Thomas Crowell Y. 2017. Hospital Chaplains: Through the Eyes of Parents of Hospitalized Children. Journal of Palliative Medicine 20: 1352–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannelly, Kevin J., Linda L. Emanuel, George F. Handzo, Kathleen Galek, Nava R. Silton, and Melissa Carlson. 2012. A national study of chaplaincy services and end-of-life outcomes. BMC Palliat Care 11: 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, Uwe. 2018. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, Lynne M. 2008. Exploring the history of social work as a human rights profession. International Social Work 51: 735–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, Paul. 2007. Understanding Cultural Globalization. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, Richard. 2018. Chaplaincy for the 21st century, for people of all religions and none. BMJ: British Medical Journal 363: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, Katherine R.B., George F. Handzo, and Kevin J. Flannelly. 2011. Testing the Efficacy of Chaplaincy Care. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 17: 100–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernohan, George W., Mary Waldron, Caroline McAfee, Barbara Cochrane, and Felicity Hasson. 2007. An evidence base for a palliative care chaplaincy service in Northern Ireland. Palliative Medicine 21: 519–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kestenbaum, Allison, Michele Shields, Jennifer James, Will Hocker, Stefana Morgan, Shweta Karve, Michael W. Rabow, and Laura B. Dunn. 2017. What impacts do chaplains have? A pilot study of spiritual AIM for advanced cancer patients in outpatient palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 54: 707–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, Nancy M. P. 1996. Making Sense of Advance Directives: Revised Edition. Washington: Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lifton, Robert J., and Eric Olson. 1974. Living and Dying. London: Wildwood House. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Charles J., Jr. 2018. Hospice Chaplains: Presence and Listening at the End of Life. Currents in Theology and Mission 45: 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1948. Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays. Boston: Beacon. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, Deborah B., Vanshdeep Sharma, Eugene Sosunov, Natalia Egorova, Rafael Goldstein, and George F. Handzo. 2015. Relationship between Chaplain Visits and Patient Satisfaction. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 21: 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslow, Abraham H. 1970. Religions, Value and Peak Experiences. New York: Viking Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Kevin, Marilyn Barnes J. D., Dana Villines, Julie Goldstein D., Anna Lee Hisey Pierson, Cheryl Scherer, Betty Vander Laan, and Wm Thomas Summerfelt. 2015. What do I Do? Developing a Taxonomy of Chaplaincy Activities and Interventions for Spiritual Care in Intensive Care Unit Palliative Care. BMC Palliative Care 14: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Karen, and Bob Whorton. 2017. Chaplaincy in Hospice and Palliative Care. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Foundation Trust-York Teaching Hospital. 2014. Spiritual Care Guideline. Available online: https://www.yorkhospitals.nhs.uk/seecmsfile/?id=681 (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Nolan, Steve. 2011. Spiritual Care at the End of Life: The Chaplain as a ‘Hopeful Presence’. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, Mary R., Karen Kinloch, Karen E. Groves, and Barbara A. Jack. 2019. Meeting patients’ spiritual needs during end-of-life care: A qualitative study of nurses’ and healthcare professionals’ perceptions of spiritual care training. Journal of Clinical Nursing 28: 182–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Stephen. 2020. Religious literacy: Spaces of teaching and learning about religion and belief. Journal of Beliefs & Values 41: 129–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Kartikeya C. 1994. Women, Earth, and the Goddess: A Shākta—Hindu Interpretation of Embodied Religion. Hypatia 9: 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentaris, Panagiotis, and Panayiota Christodoulou. 2020. Knowledge and attitudes of hospice and palliative care professionals toward diversity and religious literacy in Cyprus: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentaris, Panagiotis, and Louise L. Thomsen. 2018. Cultural and Religious Diversity in Hospice and Palliative Care: A Qualitative Cross-Country Comparative Analysis of the Challenges of Health-Care Professionals. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying 81: 648–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentaris, Panagiotis. 2018a. The marginalization of religion in end of life care: Signs of microaggression? International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare 11: 116–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentaris, Panagiotis. 2018b. Working with Loss through the Lens of Culture and Faith. Working with Grief and Traumatic Loss: Theory, Practice, Personal Self-Care and Reflection for Clinicians. Edited by Counselman-Carpenter Beth and Redcay Alex. San Diego: Cognella, pp. 153–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pentaris, Panagiotis. 2019. Religious Literacy in Hospice Care: Challenges and Controversies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sansó, Noemi, Laura Galiana, Amparo Oliver, Antonio Pascual, Shane Sinclair, and Enric Benito. 2015. Palliative care professionals’ inner life: Exploring the relationships among awareness, self-care, and compassion satisfaction and fatigue, burnout, and coping with death. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 50: 200–7. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, Dame Cicely. 2005. Cicely Saunders-Founder of the Hospice Movement: Selected Letters 1959–99. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Vanshdeep, Deborah B. Marin, Eugene Sosunov, Fatih Ozbay, Rafael Goldstein, and George F. Handzo. 2016. The Differential Effects of Chaplain Interventions on Patient Satisfaction. Journal of Health Care Chaplain 22: 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, Derald Wing. 2010. Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Swinton, John, and Harriet Mowat. 2007. What do Chaplains do? The Role of the Chaplain in Meeting the Spiritual Needs of Patients, 2nd ed. Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen and Mowat Research. [Google Scholar]

- Timmins, Fiona, Maryanne Murphy, Nicolas Pujol, Greg Sheaf, Silvia Caldeira, Elizabeth Weathers, and Bernadette Flanagan. 2016. An Exploration of Current Spiritual Care Resources in Health Care in the Republic of Ireland (ROI) and Review of International Chaplaincy Standards. Dublin: Trinity College Dublin. [Google Scholar]

- Timmins, Fiona, Silvia Caldeira, Maryanne Murphy, Nicolas Pujol, Greg Sheaf, Elizabeth Weathers, Jacqueline Whelan, and Bernadette Flanagan. 2018. The role of the healthcare chaplain: A literature review. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy 24: 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, Louise Embleton, Keemar Keemar, Keith Tudor, Joanna Valentine, and Mike Worrall. 2004. The Person-Centred Approach: A Contemporary Introduction. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, Paul. 2008. Religious Diversity in the UK: Contours and Issues. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Mari Lloyd, Michael Wright, Mark Cobb, and Chris Shiels. 2004. A prospective study of the roles, responsibilities and stresses of chaplains working within a hospice. Palliative Medicine 18: 638–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg-Lyles, Elaine, Debra Parker Oliver, George Demiris, Paula Baldwin, and Kelly Regehr. 2008. Communication dynamics in hospice teams: Understanding the role of the chaplain in interdisciplinary team collaboration. Journal of Palliative Medicine 11: 1330–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, Linda, and Rebecca Catto, eds. 2013. Religion and Change in Modern Britain. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, James. 1999. Health Care Chaplaincy: A Reflection on Models. Available online: http://jameswoodward.sdnet.co.uk/pdf/Article%2023%20Health%20Care%20Chaplaincy.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2020).

| Hospice 1 | Hospice 2 | Hospice 3 | Hospice 4 | Hospice 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Located in a city | x | x | x | x | |

| Located in a rural area | x | ||||

| Foundational roots in religious beliefs and the Church | x | x | x | x | x |

| Provide palliative and hospice care to people of all faiths and none | x | x | x | x | x |

| Maintaining quality of life until the end | x | x | x | x | x |

| Provide holistic care | x | x | x | x | x |

| Support patients and families and friends | x | x | x | x | x |

| Have a day centre | x | x | |||

| Have a chaplaincy | x | x | x | x | x |

| Provide services in the community | x | x | x | ||

| Promote education and research | x | x | x |

| Gender | Female × 12 Male × 3 |

|---|---|

| Age (mean = 45.7) | 21–30 × 1 |

| 31–40 × 4 | |

| 41–50 × 8 | |

| 51–60 × 2 | |

| Religious (non) affiliation | Christianity × 5 |

| Islam × 1 | |

| Non-religion × 7 | |

| Atheist × 2 | |

| Discipline | Nurse × 6 |

| Doctor/Consultant × 4 | |

| Counsellor × 2 | |

| Social worker × 3 | |

| Years of practice (mean = 13.4) | 0–5 × 2 |

| 6–10 × 3 | |

| 11–20 × 8 | |

| 21< × 2 | |

| Inpatient unit * | 13 |

| Outpatient unit * | 5 |

| Services in the community * | 3 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pentaris, P.; Tripathi, K. Religious/Spiritual Referrals in Hospice and Palliative Care. Religions 2020, 11, 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100496

Pentaris P, Tripathi K. Religious/Spiritual Referrals in Hospice and Palliative Care. Religions. 2020; 11(10):496. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100496

Chicago/Turabian StylePentaris, Panagiotis, and Khyati Tripathi. 2020. "Religious/Spiritual Referrals in Hospice and Palliative Care" Religions 11, no. 10: 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100496

APA StylePentaris, P., & Tripathi, K. (2020). Religious/Spiritual Referrals in Hospice and Palliative Care. Religions, 11(10), 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100496