Who Is Interested in Developing the Way of Saint James? The Pilgrimage from Faith to Tourism

Abstract

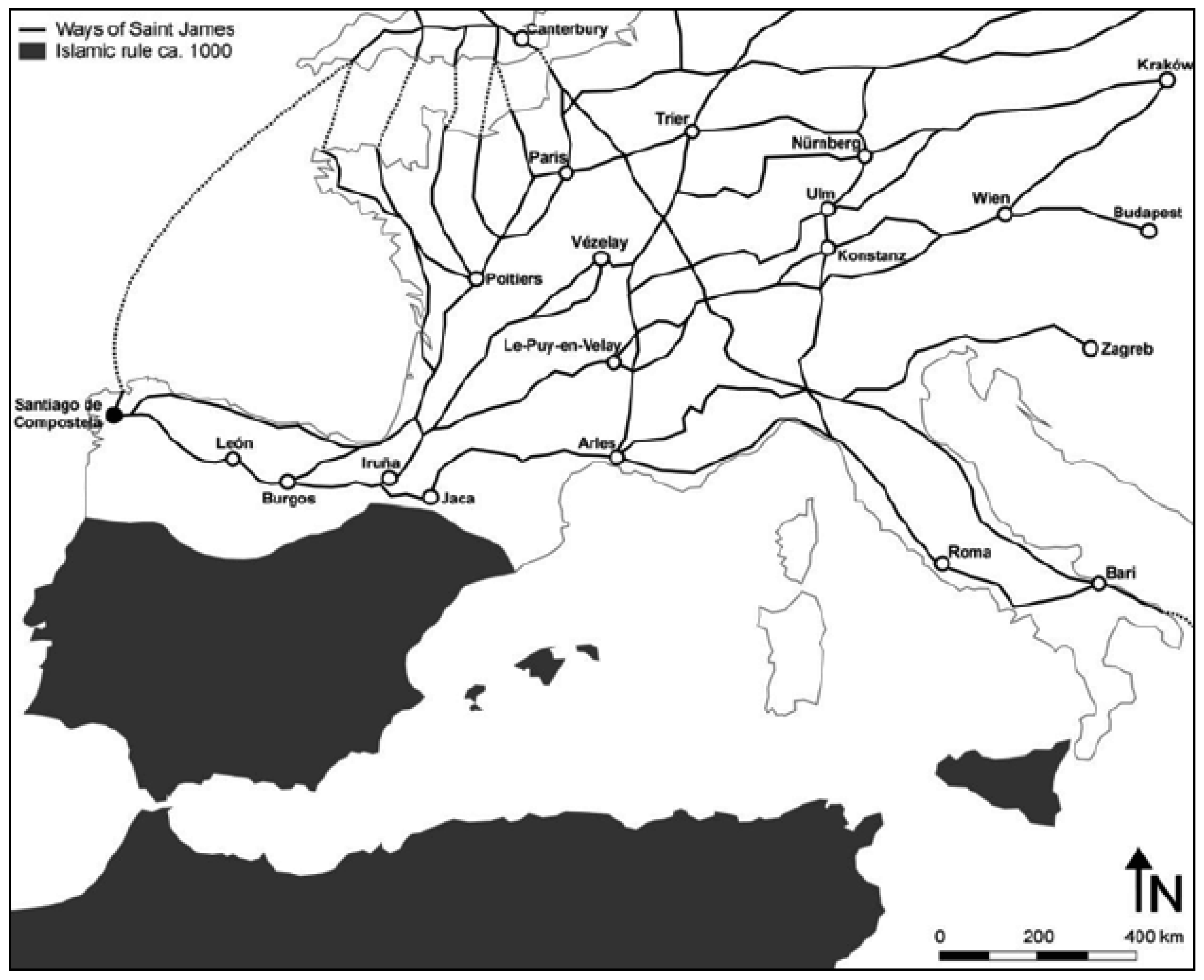

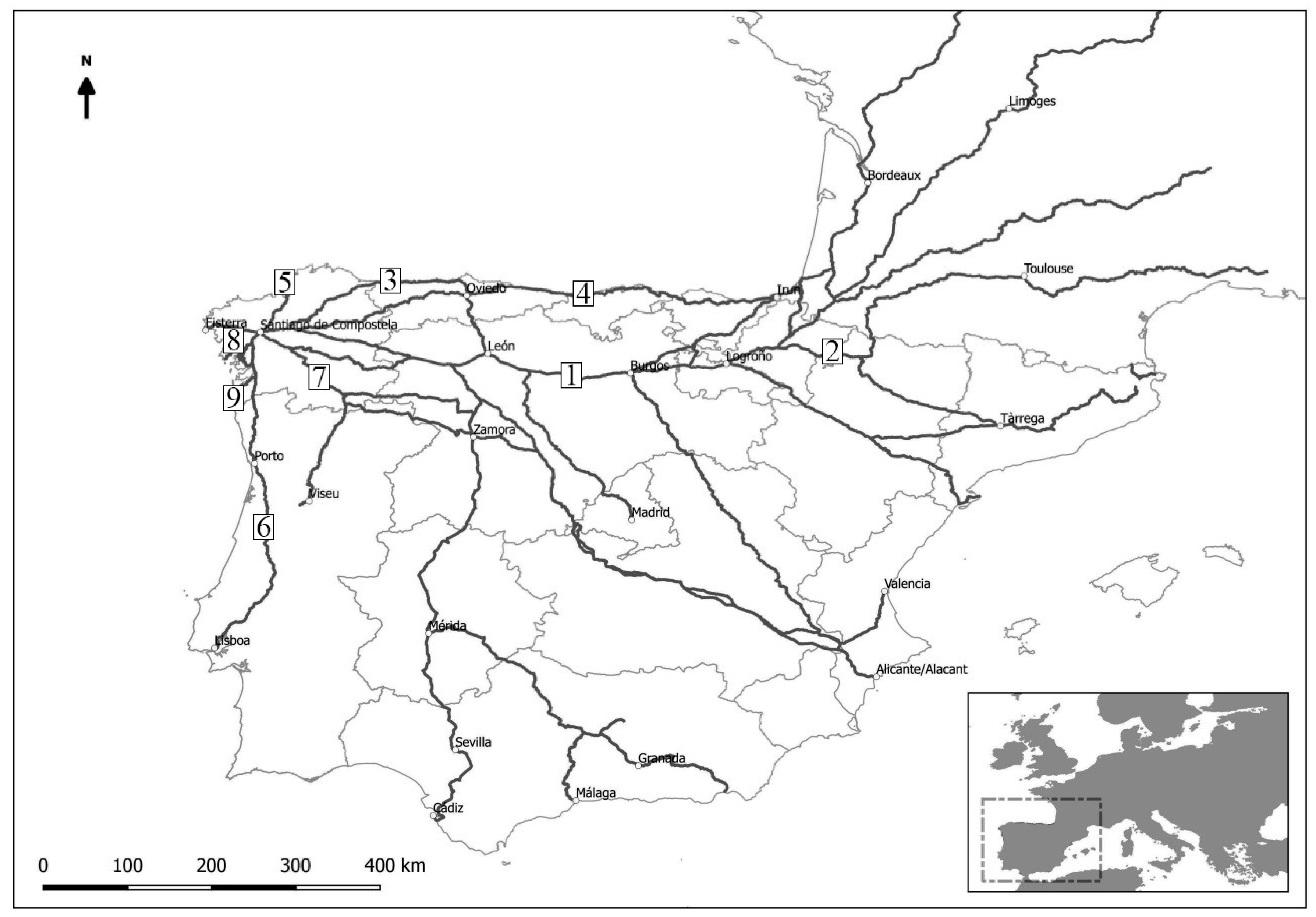

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

- Pilgrims arriving in Santiago via The Way are not required to register with the Office. A considerable number of pilgrims fly under the radar on this type of survey because they are not interested in receiving the Compostela certificate (or because they already received it, having done The Way before) or simply because they are not interested in general.

- The Compostela is a way of revealing only the pilgrims who end up in Santiago but not the ones who travel part of The Way without reaching Santiago. For this reason, they donot take into account some contemporary provisional variants; in fact, if, in the past, doing The Way involved having a lot of time, there are currently not just full-time pilgrims that travel to Santiago without stopping (they do The Way all at once), but also “part-time pilgrims”. These modern pilgrims reach Santiago in stages, in that they have little time and they do The Way at different times. For example, N.L. Frey (1998) calls the pilgrims that do The Way at weekends and tend to use pilgrimage associations “weekend pilgrims”. According to F. Cazaux (2011, p. 355), “this opportunity to accomplish the pilgrimage at various times of the year, following different routes and across several years, gave me the opportunity to apprehend the formation of the pilgrim community during different periods and to observe different methods of pilgrimage”.

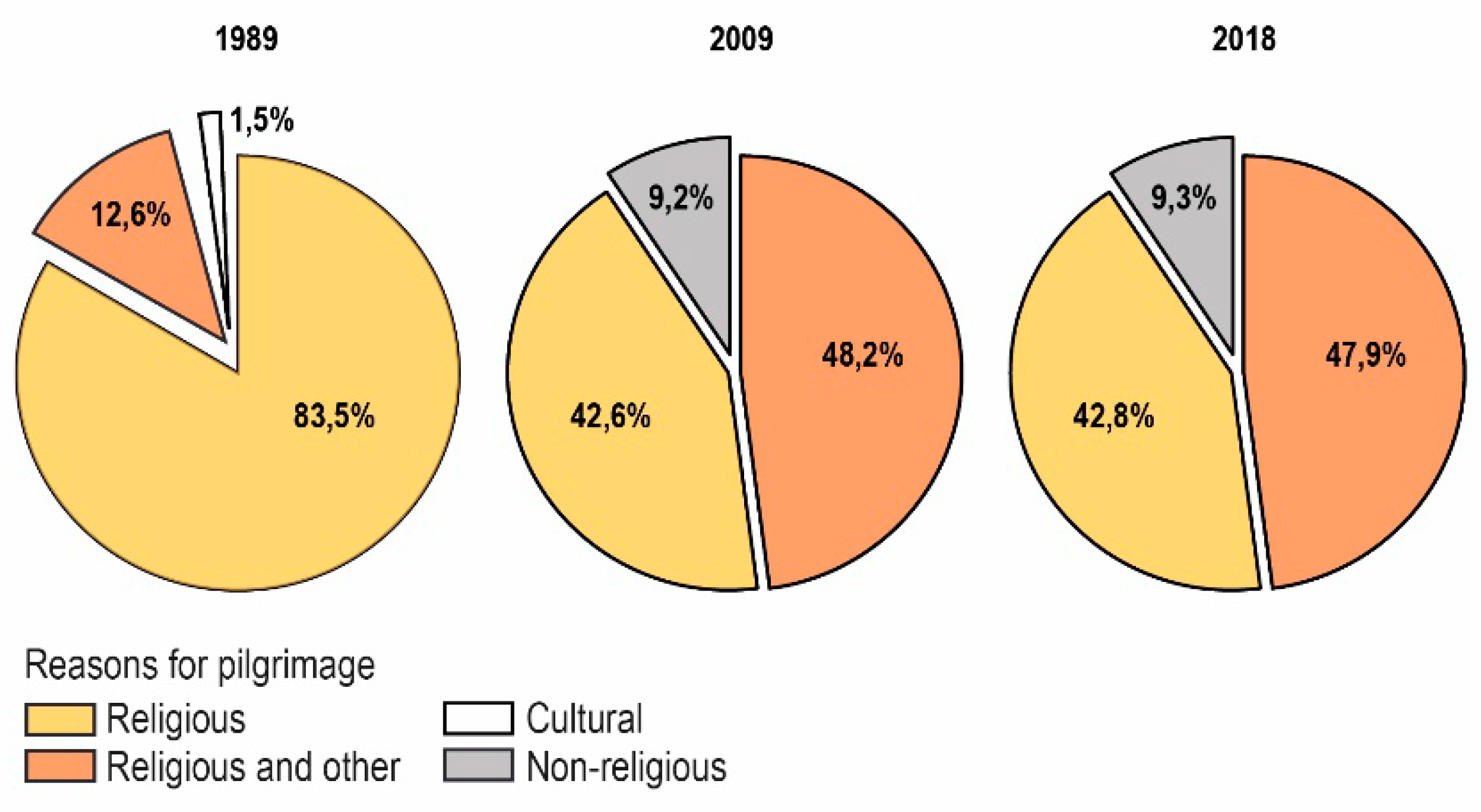

- The Compostela is only issued when the pilgrims confirm that they did The Way for religious reasons, which is a criterion that alters the truthfulness of the values, especially in terms of the motivations stated when issued, because, while obtaining this document (now a symbol of Jacobean pilgrimage), the pilgrims do not always state their real reason (Santos Solla and Lois González 2011; Lopez 2014).

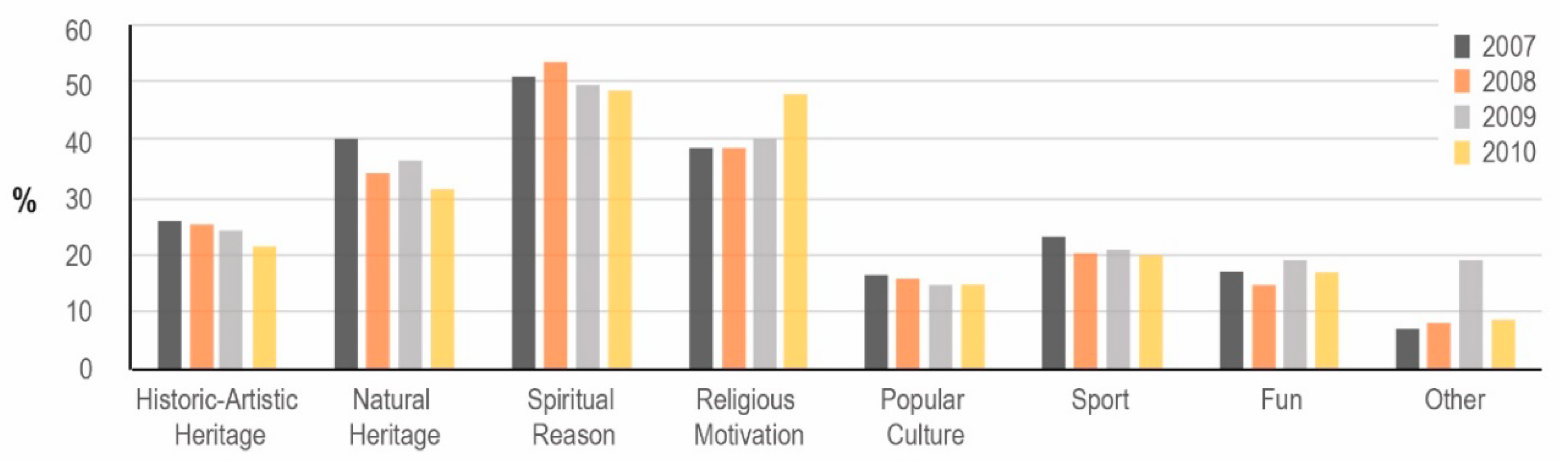

- Pilgrims identified as such through the Compostela must then be added to the tourists who arrive in Santiago or to other of The Way’s main locations. In order to address these critical issues and provide a new source of official data not exclusively linked to the Diocese of Santiago de Compostela, the abovementioned Observatory was founded in 2007. It was financed by the Galician government for three years until 2010. The data compiled by the Observatory during these three years areparticularly interesting for contemporary pilgrim profiling.

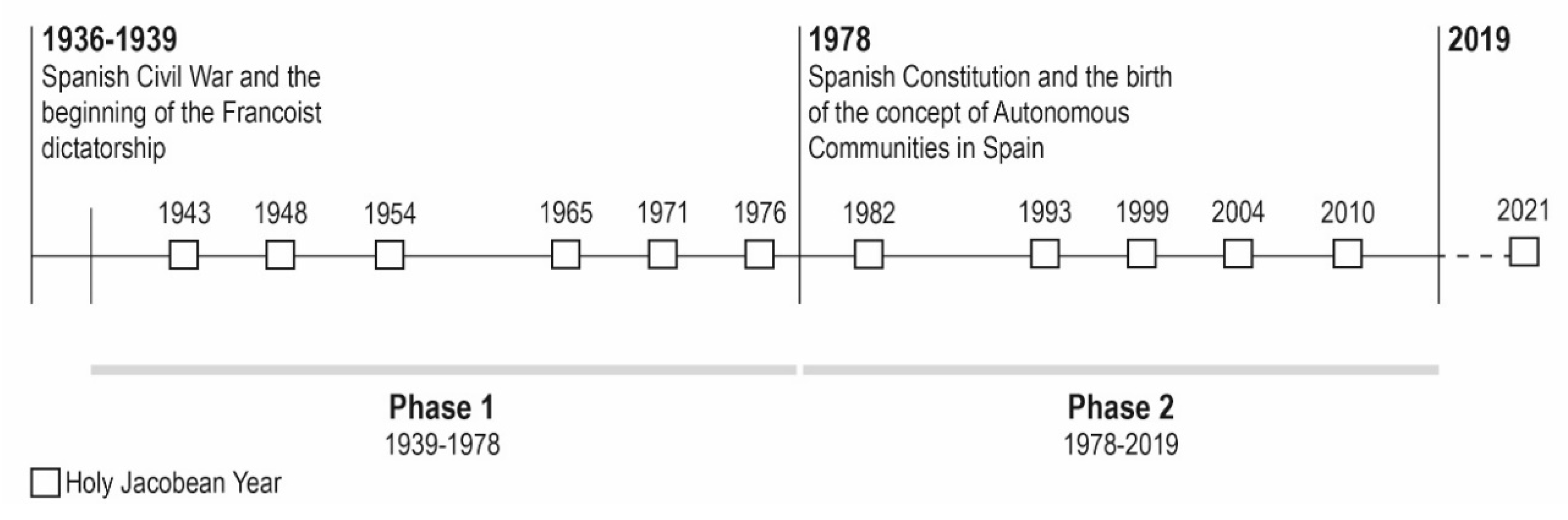

4. Discussion

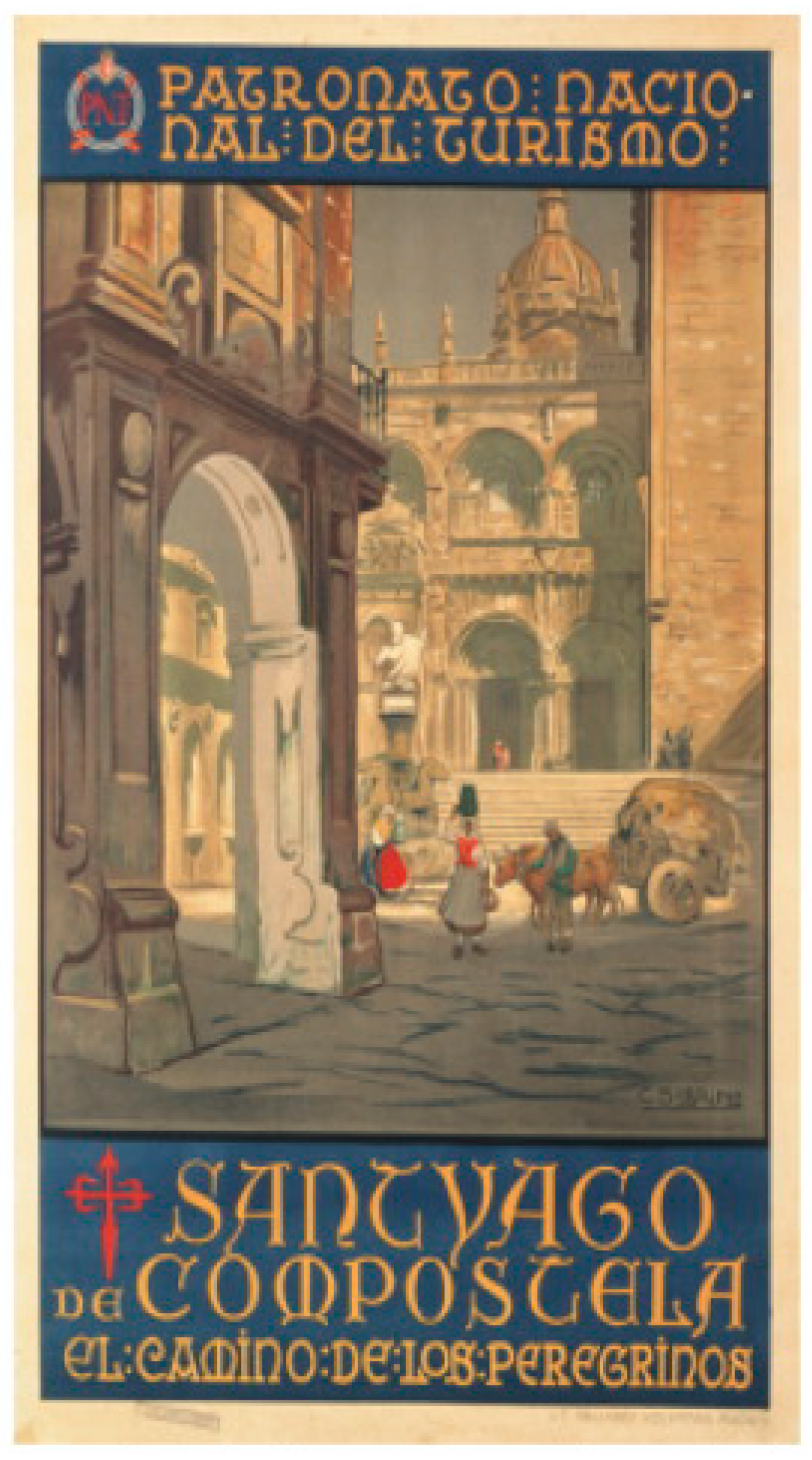

4.1. Phase 1: The Francoist Period—1939–1978

4.1.1. Context

4.1.2. Actors

4.1.3. Pilgrims

4.2. Phase 2: 1978–Present

4.2.1. Context

4.2.2. Actors

4.2.3. Pilgrims

5. Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Álvarez Junco, José. 2001. El nacionalismo español: las insuficiencias en la acción estatal. Historia Social 40: 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, Kathleen, and Marilyn Geegan, eds. 2009. Being a Pilgrim: Art and Ritual on the Medieval Routes to Santiago. Lund Humphries: Farnham-Surrey. [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro Rivas, José Luís. 1997. La función política de los Caminos de peregrinación en la Europa Medieval. Madrid: Tecnos. [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro Rivas, José Luís. 2009. The construction of political space: Symbolic and cosmological elements (Jerusalem and Santiago in Western History). Santiago de Compostela: The Araguaney Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo López, María Belén. 2001. El Camino de Santiago como Bien de Interés Cultural. Análisis en torno al estatuto jurídico de un itinerario cultural. Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco Chao, Ramon, and Sonia Garrido Faraldo. 1994. Análise da procedencia e características da afluencia turística a Santiago no Xacobeo 93. Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia. [Google Scholar]

- Blom, Thomas, Mats Nilsson, and Xosé Manuel Santos Solla. 2016. The Way to Santiago beyond Santiago. Fisterra and the pilgrimage’s post-secular meaning. European Journal of Tourism Research 12: 133–46. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Fernández, Belén María. 2007. Francisco Pons-Sorolla y Arnau, arquitecto-restaurador: sus intervenciones en Galicia (1945–1985). Santiago de Compostela: Servizo de Publicacións e Intercambio Científico, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Fernández, Belén María. 2010. El redescubrimiento del Camino de Santiago por Francisco Pons-Sorolla. Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Fernández, Belén María. 2013. Francisco Pons Sorolla. Arquitectura y restauración en Compostela (1945–1985). Santiago de Compostela: Universidad de Santiago y Consorcio de Santiago. [Google Scholar]

- Castro Fernández, Belén María, and Rubén Camilo Lois González. 2006. Se logerdans le passé. La récuperation emblematique de l’Hostal des Rois Catoliques de Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle en hotel de luxe. Espaces et Sociétés 126: 159–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Fernández, Belén María, Rubén Camilo Lois González, and Lucrezia Lopez. 2016. Historic city, tourism performance and development: The balance of social behaviours in the city of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). Tourism and Hospitality Research 16: 282–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caucci, Paolo. 1993. Santiago: La Europa del Peregrinaje. Barcelona: Lunwerg. [Google Scholar]

- Cazaux, François. 2011. To be a pilgrim: A contested identity on Saint James’ Way. Tourism.An International Interdisciplinary Journal 59: 353–67. [Google Scholar]

- Celeiro, Luís. 2013. Xacobeo 93, el renacer del Camino. In Xacobeo, de un recurso a un evento turístico global. Edited by Simone Novello, Fidel Martinez Roget, Pilar Murias Fernandez and Jose Calos de Miguel Dominguez. Santiago de Compostela: Andavira Editorial, pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- CETUR and SA Xacobeo. 2007–2010. ObservatorioEstadístico do Camiño de Santiago 2007, 2008, 2009 e 2010. Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Xunta de Galicia y Centro de Estudios Turísticos. [Google Scholar]

- Chemin, J. Eduardo. 2015. The Seductions of the Way: The Return of the Pilgrim and The Road to Compostela as a Liminal Space. In The Seductions of Pilgrimage. Sacred Journeys Afar and Astray in the Western Religious Tradition. Edited by Michael A. Di Giovine and David Picard. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 211–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chemin, J. Eduardo. 2016. Re-inventing Europe: The case of the Camino de Santiago de Compostela as European heritage and the political and economic discourses of cultural unity. International Journal of Tourism Anthropology 5: 24–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Eric. 1992. Pilgrimage and Tourism: Convergence and Divergence. In Sacred Journeys. The Anthropology of Pilgrimage. Edited by Alan Morinis. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, Simon, and John Eade. 2004. Reframing Pilgrimage. Cultures in Motion. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collins-Kreiner, Noga. 2010a. The Geography of Pilgrimage and Tourism: Transformations and Implications for Applied Geography. Applied Geography 20: 153–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Kreiner, Noga. 2010b. Researching Pilgrimage. Continuity and Transformations. Annals of Tourism Research 37: 440–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriente Córdoba, José Antonio. 1999. Protección Jurídica del Camino de Santiago: Normativa Internacional E Interna Española. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación y Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Dewsbury, John David, and Paul Cloke. 2009. Spiritual landscapes: Existence, performance and immanence. Social & Cultural Geography 10: 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giovine, Michael A., and John Elsner. 2016. Pilgrimage tourism. In the Encyclopedia of Tourism, 2nd ed. Edited by Jafar Jafari and Honggen Xiao. New York: Springer, pp. 722–24. [Google Scholar]

- Doi, Kiyomi. 2011. Onto emerging ground: Anticlimactic movement on the Camino de Santiago de Compostela. Tourism. Original Scientific Papers 59: 271–85. [Google Scholar]

- Eade, John, and Michael Sallnow. 1991. Contesting the Sacred. The Anthropology of Christian Pilgrimage. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Farias, Miguel, and Mansur Lalljee. 2008. Holistic Individualism in the Age of Aquarius: Measuring Individualism/Collectivism in New Age, Catholic, and Atheist/Agnostic Groups. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 4: 277–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Ríos, Luis, and Manuel García Docampo. 1999. As razón manifestas para face-lo Camiño. In Homo Peregrinus. Edited by Antonio Alvarez Sousa. Vigo: Xerais, pp. 119–26. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Louise Nancy. 1998. Pilgrim Stories: On and Off the Road to Santiago. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- García Cantero, Gabriel. 2010. Ruta Jacobea, jus commune y jus europeum. Revista de Derecho 7: 307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia de Cortazar, José Ángel. 1992. Viajeros, peregrinos, mercaderes en la Europa Medieval. In Viajeros, Peregrinos, Mercaderes en el Occidente Medieval (Actas de la XVIII Semana de Estudios Medeivales de Estella. 22–26 de julio 1991). Pamplona: Gobierno de Navarra, Departamento de Educación y Cultura, pp. 15–51. [Google Scholar]

- Haab, Barbara. 1996. The Way as an Inward Journey: An Anthropological Enquiry into the Spirituality of Present-Day Pilgrims to Santiago. Confraternity of Saint James Bulletin 56: 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2007. Lines: A Brief History. London: Routledge Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Kurrant, Christian. 2019. Biographical Motivations of Pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 7: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1974. La Production de l’espace. Paris: Anthropos. [Google Scholar]

- Lois González, Rubén Camilo. 2000. Dotaciones y infraestructuras del Camino de Santiago. Una aproximación geográfica. In Ciudades y villas camineras jacobeas: III Jornadas de Estudio y Debate Urbanos. Edited by Lorenzo López Trigal. León: Universidad de León, Secretariado de Publicaciones, pp. 225–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lois González, Rubén Camilo. 2013. The Camino de Santiago and its contemporary renewal: Pilgrims, tourists and territorial identities. Culture and Religion 14: 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois González, Rubén Camilo, and Lucrezia Lopez. 2012. El Camino de Santiago: una aproximación a su carácter polisémico desde la geografía cultural y el turismo. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica 58: 459–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois González, Rubén Camilo, and Xosé Manuel Santos Solla. 2015. Tourists and pilgrims on their way to Santiago. Motives, Caminos and final destinations. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 13: 149–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois González, Rubén C., Valerià Paül Carril, Miguel Pazos Otón, and Xosé Santos Solla. 2015. The Way of Saint James: A Contemporary Geographical Analysis. The Changing World Religion Map. Edited by Stanley D. Brunn. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 709–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lois González, Rubén Camilo, Belén María Castro Fernández, and Lucrezia Lopez. 2016. From sacred place to monumental space: The mobility along the way to St. James. Mobilities 11: 770–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Lucrezia. 2012. La Imagen de Santiago de Compostela y del Camino en Italia. Una aproximación desde la Geografía Cultural. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Lucrezia. 2014. Riflessioni sullo spazio sacro: il Cammino di San Giacomo di Compostella. Rivista Geografica Italiana 121: 289–309. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Lucrezia, David Santomil Mosquera, and Rubén Camilo Lois González. 2015. Film-Induced Tourism in The Way of Saint James. Almatour. J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 6: 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Lucrezia, Rubén Camilo Lois González, and Belén María Castro Fernández. 2017a. Spiritual tourism on the way of Saint James the current situation. Tourism Management Perspectives 24: 225–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Lucrezia, Yamilé Pérez Guilarte, and Rubén Camilo Lois González. 2017b. The Way to the Western European Land’s End. The Case of Finisterre (Galicia, Spain). IJPP Italian Journal of Planning Practice 1: 186–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Lucrezia, Yamilé Pérez Guilarte, and Xosé Santos Solla. 2017c. Il Nuovo Osservatorio del Cammino di Santiago: indicazioni per la sua attuazione. In Turismo, Cultura e Spiritualità. Riflessioni e Progetti Intornoalla Via Francigena. Edited by Paolo Rizzi and Gigliola Onorato. Milan: EDUCATT, pp. 103–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, Lucrezia, Enrico Nicosia, and Rubén Camilo Lois González. 2018. Sustainable Tourism: A Hidden Theory of the Cinematic Image? A Theoretical and Visual Analysis of the Way of St. James. Sustainability 10: 3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchena Gómez, Manuel. 1993. El Camino de Santiago como producto turístico. In Los Caminos de Santiago y el territorio. Edited by María P. De Torres Lunes, Augusto Pérez Alberti and Rubén Lois González. Santiago de Compostela: Conselleria de Relacions Institucionais e Portavoz do Goberno, p. 910. [Google Scholar]

- Margry, Peter Jan. 2015. Imagining an End of the World: Histories and Mythologies of the Santiago-Finisterre Connection. In Heritage, Pilgrimage and the Camino to Finisterre. Walking to the End of the World. Edited by Cristina Sánchez-Carretero. Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht and London: Springer, pp. 23–52. [Google Scholar]

- Moralejo, Serafin. 1993. Santiago, Camino de Europa. Culto y cultura en la peregrinación a Compostela. Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia. [Google Scholar]

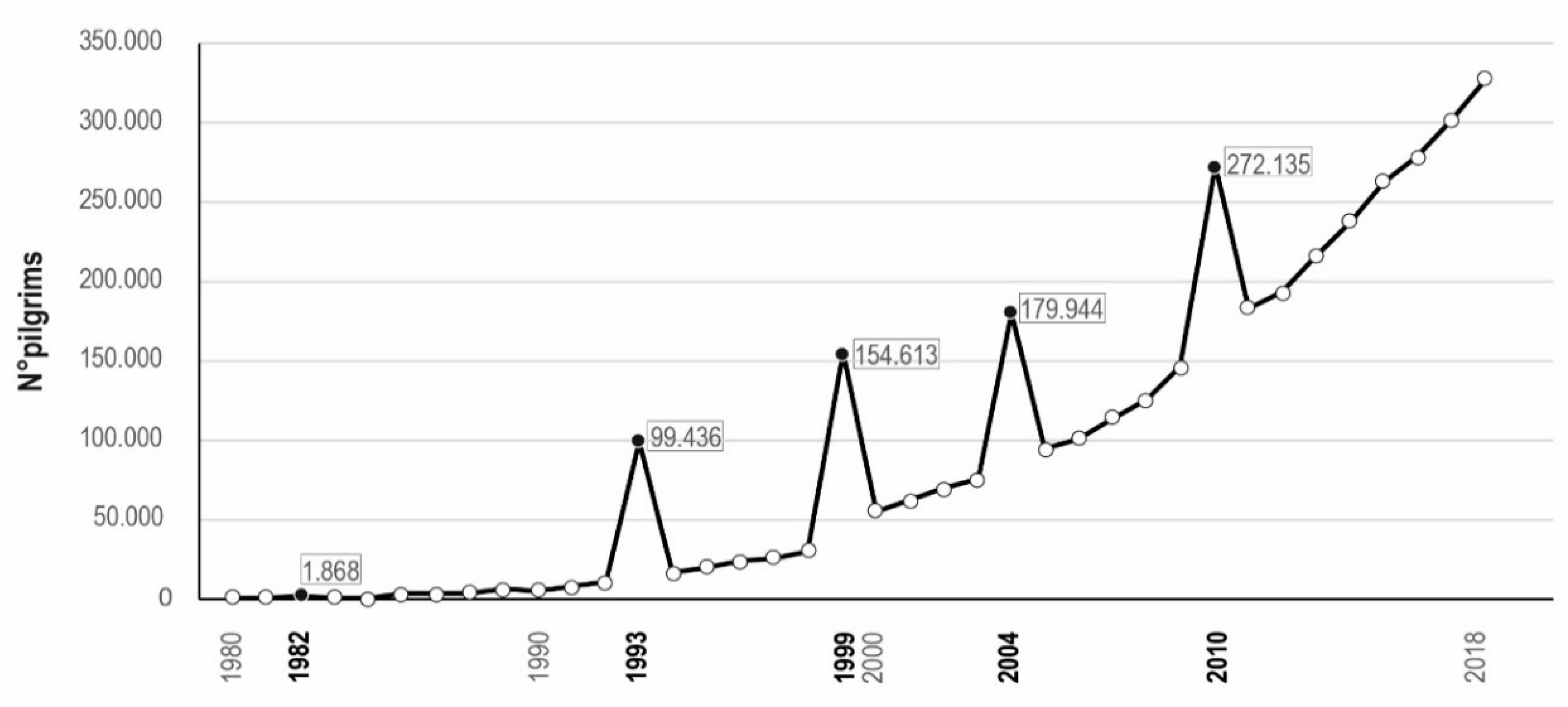

- Oficina del Peregrino (Santiago Pilgrim’s Reception Office). 1980–2018. Pilgrims’ Reports. Available online: www.archicompostela.org (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Passini, Jean. 1984. Villes Médiévales du Chemin de Saint-jacques-de-Compostelle (de Pampelune a Burgos). Villes de Fundación et Villes d’origine Romaine. Paris: Editions Recherche sur les Civilisations. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffenberger, Bryan. 1983. Serious Pilgrims and Frivolous Tourists: The Chimera of Tourism in the Pilgrimages of Sri Lanka. Annals of Tourism Research 10: 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilla, Micaela. 1991. Una ruta europea. Por Alava, a Compostela. Del paso del San Adrián al Ebro. Alava: Diputación Foral de Alava, Servicio de Publicaciones. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Manuel. 2004. Los años santos compostelanos del siglo XX. Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia. [Google Scholar]

- Roseman, Sharon R. 2008. O rexurdimento dunha base no rural no concello de Zas. O Santiaguiño de Carreira. A Coruña: Baía Edicións. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Carretero, Cristina. 2015. To Walk and to be Walked…at the End of the World. In Heritage, Pilgrimage and the Camino to Finisterre. Walking to the End of the World. Edited by Cristina Sánchez-Carretero. Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht and London: Springer, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Solla, Xosé Manuel. 1999. Mitos y realidades del Xacobeo. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 28: 103–18. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Solla, Xosé Manuel. 2013. Living in the Same but Different City. Evidence from Santiago de Compostela. Plurimond 12: 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Solla, Xosé Manuel, and Rubén Camilo Lois González. 2011. El Camino de Santiago en el contexto de los nuevos turismos. Estudios Turísticos 189: 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Santos Solla, Xosé Manuel, and Laura Pena Cabrera. 2014. Management of Tourist Flows. The Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. PASOS. Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 12: 719–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, Katharina. 2004. Coming home to the motherland. Pilgrimage tourism in Ghana. In Reframing Pilgrimage. Cultures in Motion. Edited by Simon Coleman and John Eade. London: Routledge, pp. 133–49. [Google Scholar]

- Soria y Puig, Arturo. 1993. El Camino a Santiago. Vías, Estaciones y Señales. Madrid: Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Transportes. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Otero, José. 2004. Apuntes sobre la peregrinación jacobea y la circulación monetaria en la Galicia medieval. Numisma 248: 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, Colin. 1992. Postscript: Anthropology as Pilgrimage, Anthopologist as Pilgrim. In Sacred Journeys. The Anthropology of Pilgrimage. Edited by Alan Morinis. Westport: Greenwood Press, pp. 257–74. [Google Scholar]

- Weidenfeld, Adi. 2006. Religious needs in the hospitality industry. Tourism and Hospitality Research 6: 143–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xunta de Galicia. 1994. Xacobeo 1993. Santiago de Compostela: Xunta de Galicia. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Therefore, we use the expression The Way to refer to The Way of St. James. |

| 2 | The development of The French Way and its stages were described in the famous Codex Colixtinus, also known as Liber Sancti Iacobi, particularly in the fifth section, “Liber Peregrinationis”. Given its descriptive thoroughness, this source was used as a reference to trace the historical layout of the French Way, declared a World Heritage Site in 1993. |

| 3 | The Holy Jacobean Year is essentially a Jubilee year extended uniquely to the city of Santiago de Compostela. It represents a privilege granted in 1179 by Pope Alexander III. The Holy Years are also called Jacobean Years, which are celebrated every six, five, six, and 11 years when the feast of Saint James (25 July) falls on a Sunday. |

| 4 | One example of the possible differences in turnout data in Santiago appeared in 1943, the year when Franco organised a Falangist pilgrimage. The Official Journal of the Archdiocese reported just 3000 admissions, although the press reported approximately 50,000 people. |

| 5 | The pilgrimage must at least cover 100 km on foot or 200 km by bike or on horseback. |

| 6 | The first group in the Association (from Estella, Navarre) was already around since 1962. |

| Year | Pilgrims |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 68 |

| 1971 | 451 |

| 1972 | 67 |

| 1976 | 243 |

| 1977 | 31 |

| Year | Groups | Pilgrims |

|---|---|---|

| 1943 | 128 | 100,000 |

| 1948 | 124 | 166,000 |

| 1954 | 364 | 225,000 |

| 1965 | 428 | 280,000 |

| 1971 | 496 | 305,000 |

| 1976 | 578 | 315,000 |

| Year | Groups from Galicia | Groups from Spain | Groups of Foreigners |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1943 | 93 | 35 | 0 |

| 1948 | 84 | 36 | 4 |

| 1954 | 155 | 142 | 67 |

| 1965 | 205 | 185 | 38 |

| 1971 | 183 | 280 | 33 |

| 1976 | 271 | 266 | 41 |

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | |

| Historic–artistic heritage | 25.8 | 25.0 | 23.9 | 21.2 |

| Natural heritage | 39.3 | 33.7 | 36.0 | 31.3 |

| Spiritual reason | 50.3 | 53.1 | 49.4 | 48.5 |

| Religious motivation | 38.1 | 38.3 | 39.5 | 47.6 |

| Popular culture | 16.2 | 15.7 | 14.6 | 14.7 |

| Sport | 22.8 | 19.8 | 20.8 | 19.7 |

| Fun | 17.1 | 14.8 | 19.2 | 17.1 |

| Other | 7.2 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 8.8 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moscarelli, R.; Lopez, L.; Lois González, R.C. Who Is Interested in Developing the Way of Saint James? The Pilgrimage from Faith to Tourism. Religions 2020, 11, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010024

Moscarelli R, Lopez L, Lois González RC. Who Is Interested in Developing the Way of Saint James? The Pilgrimage from Faith to Tourism. Religions. 2020; 11(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoscarelli, Rossella, Lucrezia Lopez, and Rubén Camilo Lois González. 2020. "Who Is Interested in Developing the Way of Saint James? The Pilgrimage from Faith to Tourism" Religions 11, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010024

APA StyleMoscarelli, R., Lopez, L., & Lois González, R. C. (2020). Who Is Interested in Developing the Way of Saint James? The Pilgrimage from Faith to Tourism. Religions, 11(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11010024