On the Ālayavijñāna in the Awakening of Faith: Comparing and Contrasting Wŏnhyo and Fazang’s Views on Tathāgatagarbha and Ālayavijñāna

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Tathāgatagarbha

Question: Should it be said that the self-character of this consciousness arises just due to defiled conditions, or that it does not conform to the conditions? If it arises just due to defiled conditions, then when defiled conditions are exhausted, the self-character should disappear; if the self-character does not conform to defiled conditions and thus does not disappear, then it would naturally exist by itself (K. chayŏnyu 自然有). Again, if the self-character also disappears [as in the former case], then it amounts to nihilism; likewise [if] the self-character does not disappear [as in the latter case], in turn it amounts to eternalism.Answer: Some say: The mind-essence of ālayavijñāna is ripened (K. isuk 異熟, vipāka) dharma, which is produced by karmic afflictions. Therefore, when karmic afflictions are exhausted, the base consciousness (K. ponsik 本識; viz. ālayavijñāna) disappears altogether. At the resultant [stage of] Buddhahood, however, there exists the pure consciousness that corresponds to the great perfect mirror cognition (K. taewŏn kyŏngji 大圓鏡智, ādarśa-jñāna), which has been attained from the two types of practice, practice of merits and wisdom. Thus, the minds in the both cases have identical meaning. Based on this meaning, the mind is said to be consistent until the resultant [stage of] Buddhahood.

Some say: The mind-essence of self-character moves its essence, and [this] is raised due to nescience (K. mumyŏng 無明, avidyā). This means that the serene [mind-essence] is moved and raised, not that nothing turns to something. [In other words, this mind-essence should be what originally exists, not what arises from nothing.] Therefore, the moving of this mind is what is caused by nescience, and is called the karmic character. This moving mind is basically the mind in itself, which is also called self-character. The nature of self-character is not involved with nescience. However, this mind, which is moved by nescience, also has the implication that [karmic seeds inherent in the mind continuously] produce the same types [of seeds]. Thus, although not falling into the fallacy of “naturally [existing by itself],” it still has the nature of non-ceasing. When nescience is exhausted, the moving character [of the mind] accordingly ceases, and [yet] the mind returns to the original basis by going after the initial enlightenment (K. sigak 始覺). [Therefore, the mind-essence of this mind does not cease.]

Some say: Both of the two masters’ views have a reasonable basis, because both rely on the teachings of the sacred scriptures. The former master’s view coincides with the tenets of the Yogācārabhūmi, and the latter’s with that of the Awakening of Faith. However, one should not take the meanings in a literal sense. Why? If the meaning of the former teaching is taken in a literal sense, then this would be attachment to dharmas (K. pŏp ajip 法我執, dharma-grāha); if the meaning of the latter teaching is taken in literal sense, this would be called attachment to self (K. in agyŏn 人我見, ātma-grāha). Again, if one attaches to the former meaning, one would fall into nihilism; if one attaches to the latter meaning, one would fall into eternalism. [Therefore,] one should know that the two meanings may not be taught. [However,] although they may not be taught, they may also be taught, because although they are not like [what it means], they are not unlike [what it means] either.12

Question: Is the reason why the mind-essence is called original enlightenment is because it lacks non-enlightenment or because it has the function of illumination of enlightening (K. kakcho 覺照)? If it is called original enlightenment only because it lacks non-enlightenment, then it would not have the [function of] illumination of enlightening. If then, it should be non-enlightenment. If it is called original enlightenment only because it has the function of illumination of enlightening, then I am not sure if all defilements are eradicated from this [original] enlightenment. If defilements have not been eradicated, then [in turn] it would not have the function of enlightening; if the defilements have been eradicated, then sentient beings should never exist.

Answer: [The reason why the mind-essence is called original enlightenment is] not only because it lacks non-enlightenment, but also because it has the function of illumination. Because it has the [function of] illumination, defilements can be also eradicated. What does this mean? When enlightenment that comes after delusions is considered to be called enlightenment, initial enlightenment has [the meaning of] enlightenment, while original enlightenment does not. When the original lack of delusion is said to be called enlightenment, original enlightenment is enlightenment, but initial enlightenment is not. The [matter of] eradicating defilements [may be discussed] likewise. When eradication of previously exiting defilements is called eradication, initial enlightenment has the [function of] eradication, but original enlightenment does not. When the original lack of defilements is called eradication, original enlightenment refers to eradication, but initial enlightenment does not. Viewed from this [latter] way, [defilements] are originally eradicated, and thus originally there is no ordinary being, just as stated in the passage below, “all sentient beings are originally consistently abiding (C. changzhu, K. sangju 常住) within the dharmas of nirvāṇa and bodhi.” However, although it is said that original enlightenment exists and thus originally there is no ordinary being (凡夫), there is not yet initial enlightenment and thus originally there are ordinary beings. Therefore, there is no fallacy [between the two cases]. If you [take only one aspect and] claim that because there is original enlightenment, originally there are no ordinary beings, then there would not be initial enlightenment at last. If then, on what basis could ordinary beings exist? If those [ordinary beings] do not have initial enlightenment at last, then there would be no original enlightenment, [which is contrasted to initial enlightenment,] then on basis of what original enlightenment can it be said that there is no ordinary beings?17

3. Ālayavijñāna

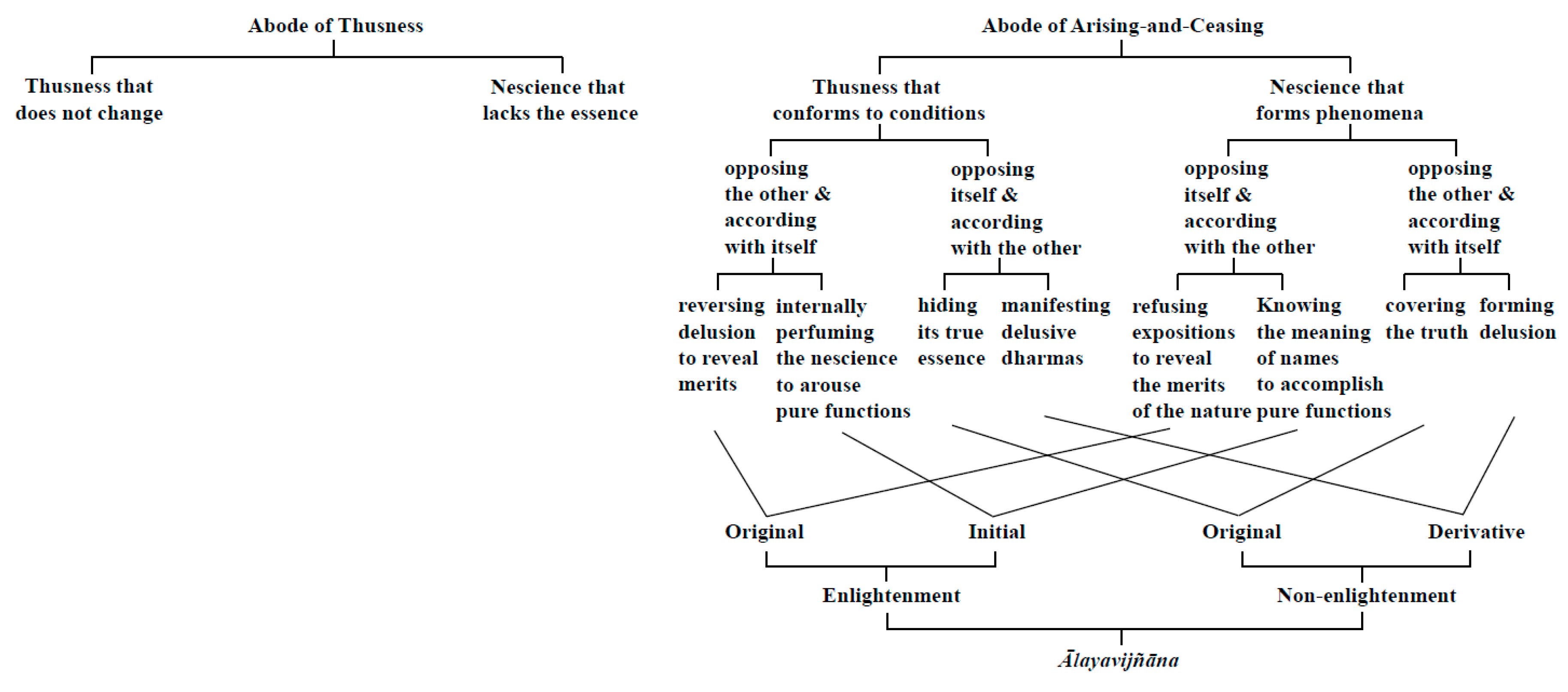

As for the above statement, “This consciousness has two natures [of the enlightenment and the non-enlightenment],” the “natures” are somewhat difficult [to understand] and now I summarize the [entire] passage above and below to briefly describe the meaning. For the rest of the passages, one will then understand it when [later] reading it. As for what [it is like, it is] as follows: Thusness (C. zhenru 眞如) has two aspects. One is the aspect of unchangeability (C. bubian yi 不變義), and the other is the aspect of conforming to [changing] conditions (C. suiyuan yi 隨緣義). Nescience (C. wuming 無明, avidyā) also has two meanings. One is the aspect of emptiness that lacks the essence (C. wuti jikong yi 無體即空義), and the other is the aspect of functioning that forms phenomena (C. youyong chengshi yi 有用成事義). Truth (C. zhen 眞), [i.e., Thusness] and delusion (C. wang 妄), [i.e., nescience] constitute the abode of Thusness (C. zhenrumen 眞如門) on the basis of the former aspects, and constitute the abode of arising-and-ceasing (C. shenmiemen 生滅門) on the basis of the latter aspects.

[The two latter aspects, that is,] Thusness that conforms to conditions (C. suiyuan zhenru 隨緣眞如) and nescience that forms phenomena (C. chengshi wuming 成事無明) each also have two aspects. One is the aspect of opposing itself and according with the other (C. weizi shunta yi 違自順他義), and the other is the aspect of opposing the other and according with itself (C. weita shunzi yi 違他順自義). In the case of nescience [that forms phenomena], the first [aspect of] opposing itself and according with the other has two further aspects. One is [the aspect of] being capable of refusing [language] expositions to reveal the virtuous merits of the nature [of Thusness] (C. nengfanduiquan shixinggongde 能反對詮示性功德), and the other is [the aspect of] being capable of knowing the meaning of names to accomplish pure functions (C. nengzhimingyi chengjingyong 能知名義成淨用). The [second aspect of] opposing the other and according with itself also has two aspects. One is [the aspect of] covering truth (C. fu zhenli 覆眞理), and the other is [the aspect of] forming delusory mind (C. cheng wangxin 成妄心). In the case of Thusness [that conforms to conditions], the [aspect of] opposing the other and according with itself has also two aspects. One is [the aspect of] reversing delusion and defilements to reveal its own merits (C. fanduiwangran xianzide 翻對妄染顯自德), and the other is [the aspect of] internally perfuming nescience to arouse pure functions (C. neixunwuming qijingyong 內熏無明起淨用). [The aspect of] opposing itself and according with the other has also two aspects. One is the aspect of hiding its true essence (C. yinzizhenti yi 隱自眞體義), and the other is the aspect of manifesting delusive dharmas (C. xianxianwangfa yi 顯現妄法義).

Among the four aspects for each of the truth and delusion, on the basis of [the two aspects, that is,] the aspect of refusing [language] expositions to reveal [the virtuous merits] in case of nescience and the aspect of reversing delusion to reveal merits in case of Thusness, one can come to have original enlightenment. On the basis of [the two aspects, that is,] the aspect of being capable of knowing the meaning of names in case of nescience and the aspect of internally perfuming in case of Thusness, one can come to have initial enlightenment. In addition, on the basis of [the two aspects, that is,] the aspect of covering the truth in case of nescience and the aspect of hiding the essence in case of Thusness, one can come to have the original non-enlightenment (C. genben bujue 根本不覺). And, on the basis of [the two aspects, that is,] the aspect of forming delusion in case of nescience and the aspect of manifesting delusion in case of Thusness, one can come to have the derivative no-enlightenment (C. zhimo bujue 枝末不覺).

In this abode of arising-and-ceasing, [the nature of] the truth and delusion is briefly divided into four aspects, but in detailed level, there are eight aspects. When [paired aspects from Thusness and nescience] are unified to constitute the dependent origination, there are four divisions, namely, two for enlightenment and two for non-enlightenment. When the origin and its derivatives are not separated from each other, there are only two divisions, namely, enlightenment and non-enlightenment. When [they are all] interfused to encompass each other, there are only one, namely, the abode of arising-and-ceasing of the one mind (C. yixin shengmie men 一心生滅門).38

4. Concluding Reflections

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

Primary Sources

Awakening of Faith 大乘起信論. T1666.Dasheng qixinlun yiji 大乘起信論義記. T1846.Huayan yisheng jiao fenqi zhan 華嚴一乘教義分齊章. T1866.Kisillon so 起信論疏. T1844.Lengqie abatuoluo baojing 楞伽阿跋多羅寶經 T670.Ru lengqie jing 入楞伽經 T671.Ru lengqiexin xuanyi 入楞伽心玄義 T1790.Taesŭng kisillon pyŏlgi 大乘起信論別記 T1845.Yŏlban chongyo 涅槃宗要 T1769.Secondary Sources

- Fuji, Ryūsei 藤隆生. 1964. Ryōga kyō ni okeru ichini no mondai: Nyoraizō Yuishiki setsu no kōshō 『楞伽経』における一・二の問題: 如来蔵唯識説の考証 [One or two problems in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra: Historical investigation of theories on tathāgatagarbha and Yogācāra]. Ryūkoku Daigaku Bukkyō Bunka enkyūjo kiyō 龍谷大学佛敎文化硏究所紀要 3: 153–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, Masanori 池田將則. 2012. Kyō’u shōoku shōzou tonkō bunken the Dashengqixinlun shu (gidai, 羽333V) ni tsuite 杏雨書屋所藏敦煌文獻 『大乘起信論疏』 (擬題, 羽333V) について [On the Dunhuang Manuscript Dasheng qixin lun shu 大乘起信論疏 (provisional title; hane 羽 333 verso) belonging to the Kyō’u 杏雨 Library]. Pulgyŏhak Review 불교학리뷰 12: 45–167. [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi, Hiroo 柏木弘雄. 1981. Daijō kishin ron no kenkyū: Daijō kishin ron no seiritsu ni kansuru shiryōron teki kenkyū 大乗起信論の研究: 大乗起信論の成立に関する資料論的研究 [A study of the Awakening of Faith: A study on the materials in the formation of the Awakening of Faith]. Tōkyō: Shunjūsha. [Google Scholar]

- Katsumata, Shunkyō 勝又俊敎. 1961. Bukkyō ni okeru shinshikisetsu no kenkyū 仏敎における心識說の研究 [A study on the theory of consciousness and mind in Buddhism]. Tōkyō: Sankibō Busshorin. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Whalen. 1980. The I-ching and the Formation of the Hua-yen Philosophy. Journal of Chinese Philosophy 7: 245–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, Charles. 2004. The Yogācāra Two Hindrances and their Reinterpretations in East Asia. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 27: 207–35. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, Charles. 2006. Wonhyo’s Reliance on Huiyuan in his Exposition of the Two Hindrances. Bulletin of Tōyō Gakuen University 14: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Takasaki, Jikido 高崎直道. 1960. Kegon shisō to nyoraizō shisō 華厳教学と如来蔵思想 [Huayan theories and tathāgatagarbha thoughts]. In Kegon shisō 華厳思想 [Huayan thoughts]. Edited by Kawada Kumatarō 川田熊太郎 and Nakamura Hajime 中村元. Kyōto: Hōzōkan, pp. 277–334. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizu, Yoshihide 吉津宜英. 1983. Shōsō yūe ni tsuite 性相融会について [On the interfusion of nature and characteristics]. Komazawa Daigaku Bukkyōgakubu kenkyū kiyō 駒澤大學佛教學部研究紀要 41: 300–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizu, Yoshihide 吉津宜英. 2005. Kishinron to Kishinron shisō: Jōyōji Eon no jirei o chūshin ni shite 起信論と起信論思想: 淨影寺慧遠の事例を中心にして [The Awakening of Faith and the ideas of the Awakening of Faith: Centering on a Case Study of Jingying Huiyuan]. Komazawa Daigaku Bukkyōgakubu kenkyū kiyō 駒沢大学仏教学部研究紀要 63: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The predominant recognition of the Awakening of Faith as a so-called “tathāgatagarbha text” owes evident debts to Fazang’s identification of the treatise as “the teaching of the dependent origination of tathāgatagarbha” (C. Rulaizang yuanqi zong 如來藏緣起宗) in his fourfold doctrinal taxonomy (C. jiaopan 敎判) of Buddhist teachings. Based on Fazang’s interpretation, the thought of tathāgatagarbha has been regarded as a separate doctrinal system from the two major Mahāyāna traditions, Madhyamaka and Yogācāra, especially by Japanese scholars. For instance, Katsumata Shunkyō argues that Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism cannot be explained merely in terms of the antagonistic evolution of the two doctrinal systems of Madhyamaka and Yogācāra, by saying that Fazang’s recognition of the teaching of the dependent origination of tathāgatagarbha (C. Rulaizang yuanqi zong 如來藏緣起宗) separately from Madhyamaka and Yogācāra shows his impartial perspective on Indian Buddhism (Katsumata 1961, pp. 593–94). Takasaki Jikido also admits that the present distinction of the tathāgatagarbha thought as a separate doctrinal system from Yogācāra is based on the traditional way of thinking that has been formed through Huayan doctrines (Takasaki 1960, p. 280). |

| 2 | Kashiwagi also goes on to indicate that in the history of the development of “the ideas of the Awakening of Faith” in China and Japan, Huayan’s, especially Fazang’s, understanding of the Awakening of Faith, offered a decisive direction (Kashiwagi 1981, pp. 4–5). Thereafter, Yoshizu Yoshihide also addresses this issue of “the ideas of the Awakening of Faith” in his article on Jingying Huiyuan’s 淨影慧遠 (523–592) deviating interpretation of the Awakening of Faith. Although Kashiwagi emphasized the need to distinguish the original tenets of the Awakening of Faith from the later commentators’ interpretations of the Awakening of Faith, in this article, Yoshizu carefully suggests the possibility that the late commentators’ interpretations may also discuss some of the original teachings of the Awakening of Faith (Yoshizu 2005, p. 1). |

| 3 | In the Dasheng qixinlun yiji (Hereafter, Yiji), Fazang seeks to resolve the contemporary doctrinal tension revolving around the distinct doctrinal positions of Madhyamaka master Bhāvaviveka (ca. 500–570; C. Qingbian 淸辯/清辨) and Yogācāra master Dharmapāla (ca. 6th century CE; C. Hufa 護法), by using the teaching of the Awakening of Faith. At the beginning of the Yiji, Fazang introduces the contrasting positions of Madhyamaka exegete Jñānaprabha (d.u.; C. Zhiguang 智光) and Yogācāra exegete Śīlabhadra (529–645; C. Jiexian 戒賢), Bhāvaviveka and Dharmapāla’s successors, respectively, regarding the Buddha’s three-period teachings (C. sanshi jiao 三時教). In his four-level taxonomy of Buddhist teachings, Fazang locates their teachings on the second and third level, designating them as the teaching of true emptiness and no-characteristics (C. Zhenkong wuxiang zong 眞空無相宗) and the teaching of consciousness-only and dharma characteristics (C. Weishi faxiang zong 唯識法相宗), respectively. The Awakening of Faith is located in the fourth and highest teaching, with the name of the teaching of the dependent origination of tathāgatagarbha (C. Rulaizang yuanqi zong 如來藏緣起宗). In this highest teaching of the Awakening of Faith, the principle (C. li 理) and phenomena (C. shi 事), which are valued in the second and third teachings, respectively, are unimpededly interpenetrated. See the Yiji, Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新修大藏經 (Hereafter, T)1846:44.242a29-242c05; 243b22-c01. |

| 4 | As is well-known, Dharmapāla’s Yogācāra teaching spread to China when the famous pilgrim and translator Xuanzang 玄奘 (602–664) brought a new corpus of canonical texts from India in 645, after he had studied under Śīlabhadra, the teacher of Dharmapāla. Beside this, the fact that early commentaries, such as Tanyan’s 曇延 (516–588) Qixinlun yishu 起信論義疏 and the Dunhuang manuscript of the Dasheng qixinlun shu 大乘起信論疏 (tentative title; 羽333V) recently discovered in the archives of the Kyou Shōoku 杏雨書屋, are written from significantly different perspectives than Wŏnhyo or Fazang’s, also suggests that the Awakening of Faith was interpreted in different ways, according to the commentators’ positions. For instance, while Wŏnhyo and Fazang explain the Awakening of Faith by drawing on the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, Tanyan’s commentary and the anonymous Dunhuang text are written with considerable reference to the She dashenglun shi 攝大乘論釋, Paramārtha’s (499–569; C. Zhendi 眞諦) translation of Mahāyānasaṃgraha, never mentioning the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra. For more information on the Dunhuang manuscript of the Dasheng qixinlun shu, see Ikeda (2012). |

| 5 | See the Awakening of Faith T1666:32.576b07-09: 心生滅者,依如來藏故有生滅心,所謂不生不滅與生滅和合, 非一非異,名為阿梨耶識. |

| 6 | Four recensions of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra are known: Bodhiruci’s (fl. 508–35) Ru lengqie jing 入楞伽經 in 10 fascicles (513), Guṇabhadra’s (394–468) Lengqie abatuoluo baojing 楞伽阿跋多羅寶經 in 4 fascicles (443), Dharmakṣema’s (d.u.) Lengqiejing 楞伽經 in 4 fascicles (412–433), and Śikṣānanda’s (fl. ca. 695) Dasheng rulengqie jing 大乘入楞伽經 in 7 fascicles (700). Among these, Dharmakṣema’s Lengqiejing is not extant. |

| 7 | See the Lengqie abatuoluo baojing T670:16,483a14-17: 諸識有三種相, 轉相、業相、眞相。大慧! 略說有三 種識,廣說有八相。何等為三? 謂眞識、現識,及分別事識. |

| 8 | See the Ru lengqie jing T671:16,521c29-522a03: 大慧! 識有三種。何等三種? 一者、轉相識;二者、 業相識; 三者、智相識。大慧! 有八種識, 略說有二種。何等為二? 一者、了別識;二者、分別事識. |

| 9 | See the Kisillon so T1844:44,208c08: 自眞相者。十卷經云中眞名自相。 |

| 10 | To explain the unification of the neither-arising-nor-ceasing mind and the arising-and-ceasing mind in a neither-identical-nor-different condition, Wŏnhyo and Fazang both quote the passage of the four-fascicle recension, in which the true character (C. zhenxiang 眞相) and the evolving character (C. zhuanxiang 轉相) are described as neither different nor identical by using the parable of a lump of soil and dust. For Wŏnhyo’s quotation, see the Kisillon so T1844:44,208b19-c12: 此是不生滅心與生滅和合。非謂生滅與不生滅和合也。非一 非異者。不生滅心舉體而動。故心與生滅非異。而恒不失不生滅性。故生滅與心非一。又若是一者。生滅識相 滅盡之時。心神之體亦應隨滅。墮於斷邊。若是異者。依無明風熏動之時。靜心之體不應隨緣。即墮常邊。離此二邊。故非一非異。如四卷經云。譬如泥團微塵。非異非不異。金莊嚴具亦如是。若泥團微塵異者。非彼所成。而實彼成。是故非異。若不異者。泥團微塵應無差別。如是轉識藏識眞相若異者。藏識非因。若不異者。轉識 滅藏識亦應滅。而自眞相實不滅。是故非自眞相識滅。但業相滅. For Fazang’s quotation, see the Yiji T1846:44.255b16-26: 又若一者。生滅識相滅盡之時。真心應滅。 則墮斷過。若是異者。依無明風熏動之時。靜心之體應不隨緣。則墮常過。離此二邊故非一異。又若一則無和合。若異亦無和合。非一異故得和合也。如經云。譬如泥團微塵非異非不異。金莊嚴具亦復如是。若泥團異者。非彼所成。而實彼成。是故非異。若不異者。泥團微塵應無差別。如是轉識藏識眞相若異者。藏識非因。若不異者。轉識滅。藏識亦應滅。而自眞相實不滅。是故非自眞相識滅。但業相滅. |

| 11 | Wŏnhyo uses self-character (K. chasang 自相), mind-essence (K. simch’e 心體), and mind-essence of the self-character (K. chasang simch’e 自相心體) in the same sense, as seen in the quotation below. In another place, Wŏnhyo also states that the mind-essence refers to the mind of self-character (K. chasangsim 自相心). See the Kisillon so T1844:44.213c07-08: 而無別體。唯依心體。故言依心。即是梨耶自相心也. The compound word, the mind-essence of the self-character, is seen in two other places in the Kisillon so. See the Kisillon so T1844:44.216c17-19: 又復上說因滅故 不相應心滅者。但說心中業相等滅。非謂自相心體滅也; T1844:44.216c 24-25 而其自相心體不滅。故言非是水滅也. |

| 12 | See the Kisillon so T1844:44.216c28-217a21: 問。此識自相。為當一向染緣所起。為當亦有不從緣義。若是一向 染緣所起。染法盡時自相應滅。如其自相不從染緣故不滅者。則自然有。又若使自相亦滅同斷見者。是則自相不滅還同常見。答。或有說者。梨耶心體是異熟法。但為業惑之所辨生。是故業惑盡時。本識都盡。然於佛果。亦有福慧二行所惑大圓鏡智相應淨識。而於二處心義是同。以是義說心至佛果耳。或有說者。自相心體。舉體為彼無明所起。而是動靜令起。非謂辨無令有。是故此心之動。因無明起。名為業相。此動之心。本自為心。亦為自相。自相義門不由無明。然即此無明所動之心。亦有自類相生之義。故無自然之過。而有不滅之義。無明盡時動相隨滅。心隨始覺還歸本源。或有說者。二師所說皆有道理。皆依聖典之所說故。初師所說得瑜伽意。後師義者得起信意。而亦不可如言取義。所以然者。若如初說而取義者。即是法我執。若如後說而取義者。是謂人我見。又若執初義。墮於斷見。執後義者。即墮常見。當知二義皆不可說。雖不可說而亦可說。以雖非然而非不然故. |

| 13 | Although it is not directly stated that Wŏnhyo himself advocates the third view in the Kisillon so, it is clear that Wŏnhyo defends the third view in the context. Moreover, at the beginning of the third view in the equivalent passage of the Pyŏlgi, “[if I] make a comment [on the two former views, it is as follows:]” (K. p’yŏngwal 評曰) appears instead of “Some say.” See the Taesŭng kisillon pyŏlgi (hereafter, Pyŏlgi) T1845:44. 239a03. |

| 14 | See the Pyŏlgi T1845:44.229a12-229b22; T1845:44.236b02-23; T1845:44.237b24-c17 and the Kisillon so T1844:44.215b25-215c13. It has also been known that although Fazang substantially relies on Wŏnhyo’s commentaries, he never cites or quotes the passages from Wŏnhyo’s commentaries, in which the early Yogācāra doctrine or text is introduced to be reconciled with the teaching of the Awakening of Faith. Besides, in the Ijang ŭi 二障義 [System of the Two Hindrances], Wŏnhyo comprehensively deals with this matter of reconciliation between the early Yogācāra and the teaching of the Awakening of Faith by focusing on the concept of the two hindrances (K. ijang 二障). Detailed discussions may be found in Muller (2004, 2006). |

| 15 | See the Awakening of Faith T1666:32.576b10-14: 此識有二種義,能攝一切法、生一切法。云何為二? 一者、覺義, 二者、不覺義。所言覺義者,謂心體離念。離念相者,等虛空界無所不遍,法界一相即是如來平等法身,依此 法身說名本覺。Here, the “enlightenment” (C. jie 覺), which is contrasted with non-enlightenment (C. bujue 不覺), is also expressed as “original enlightenment” (C. benjue 本覺). Strictly speaking, it may be said that there are two levels of meaning of original enlightenment: one that is contrasted with non-enlightenment and the other that is contrasted with initial enlightenment (C. shijue 始覺). The former may be seen as original enlightenment in a broad sense, in contrast to non-enlightenment, and the latter as in a narrow sense, in contrast to initial enlightenment within the category of the enlightenment. Yet, the Awakening of Faith states that initial enlightenment is ultimately not different from original enlightenment, and thus the broad and narrow senses of original enlightenment may be accordingly said to be not-different from each other in an ultimate sense. See the Awakening of Faith T1666:32.576b14-16: 本覺義者,對始覺義說,以始覺者即同本覺。始覺義者,依本覺故而有不覺,依不覺故說有始覺. |

| 16 | See the Awakening of Faith T1666:32.576b11-12: 所言覺義者,謂心體離念. Wŏnhyo also clearly says that the one mind essence is (or has) original enlightenment, and associates it with the nature of Tathāgata, namely, tathāgatagarbha. See the Kisillon so T1844:44.206c18-20: 此一心體是[/有]本覺。而隨無明動作生滅。故於此門 如來之性隱而不顯。名如來藏. “The essence of this one mind is[/has] the original enlightenment, and yet moves in accordance with nescience to produce the arising-and-ceasing. Therefore, the nature of Tathāgata of this abode [of arising-and-ceasing], which is hidden and does not manifest itself, is called tathāgatagarbha.” |

| 17 | See the Pyŏlgi T1845:44.230b02-18: 問。為當。心體只無不覺故名本覺。為當。心體有覺照用名為本覺。 若言只無不覺名本覺者。可亦無覺照故是不覺。若言有覺照故名本覺者。未知此覺為斷惑不。若不斷惑則無照用。如其有斷則無凡夫。答。非但無闇。亦有明照。以有照故。亦有斷惑。此義云何。若就先眠後覺名為覺者。始覺有覺。本覺中無。若論本來不眠名為覺者。本覺是覺。始覺則非覺。斷義亦爾。先有後無名為斷者。始覺有斷。本覺無斷。本來離惑名為斷者。本覺是斷。始覺非斷。若依是義。本來斷故。本來無凡。如下文云。一切眾生。從本已來。入於涅槃菩提之法。然雖曰有本覺故本來無凡。而未有始覺故。本來有凡。是故無過。若汝。言由有本覺本來無凡。則終無始覺。望何有凡者他。亦終無始覺則無本覺。依何本覺以說無凡. |

| 18 | See the Kisillon so T1844:44.211c26-212a01: 總說雖然。於中分別者。若論始覺所起之門。隨緣相屬 而得利益 。由其根本隨染本覺。從來相關有親疎故。論其本覺所顯之門。普益機熟不簡相屬。由其本來性淨本覺。等通一切無親疎故. |

| 19 | See the Yŏlban chongyo T1769:38.250a03-250a17. |

| 20 | In Wŏnhyo’s works, such as the Yŏlban chongyo, the nature of realization that conforms to impurity refers to the original enlightenment that conforms to impurity. See footnote 19 above. |

| 21 | See the Ru lengqiexin xuanyi 入楞伽心玄義 T1790:39.431c11-14: 由習氣海中 有帶妄之眞。名本覺。 為無漏因。多聞熏習為增上緣。或亦聞熏與習海合為一無漏因。梁論云。多聞熏習與本識中解性和合。一切 聖人以此為因. “In the ocean of habituated tendencies (vāsanā), there is the truth that assumes delusion, and it is called original enlightenment. [This] constitutes the cause of uncontaminated [dharmas] (anāsrava), while permeation from great learning works as auxiliary conditions. Otherwise, permeation of hearing combined with the ocean of habituated tendencies serves as the one cause of uncontaminated [dharmas]. [Therefore] Paramārtha’s commentary on the Mahāyānasaṃgraha states that permeation from great learning is combined with the nature of realization in the base-consciousness, and this is taken as the cause of all sainthood.” |

| 22 | See the Huayan yisheng jiao fenqi zhan 華嚴一乘教義分齊章 T1866:45.485c14-20: 其有種性者。瑜伽論云。 種性略有二種。一本性住。二習所成。本性住者。謂諸菩薩六處殊勝有如是相。從無始世。展轉傳來法爾所得。習所成者。謂先串習善根所得。此中本性。即內六處中意處為殊勝。即攝賴耶識中本覺解性為性種性. |

| 23 | See the Huayan yisheng jiao fenqi zhan T1866:45.487c04-c05: 梁攝論說為黎耶中解性。起信論中。說黎耶二義 中本覺是也. |

| 24 | By comparison, Fazang describes tathāgatagarbha as neither-arising-nor-ceasing, the seven consciousnesses as arising-and-ceasing, and ālayavijñāna as arising-and-ceasing and neither-arising-nor-ceasing. See the Yiji T1846:44.255a29-b03: 一以如來藏唯不生滅。如水濕性。二七識唯生滅。如水波浪。三梨耶識亦生滅亦不生滅 。如海含動靜。四無明倒執非生滅非不生滅。如起浪猛風非水非浪. “First, tathāgatagarbha neither-arises-nor-ceases, just like the nature of the wetness of water; second, the seven consciousnesses only arise-and-cease, just like waves [of water]; third, ālayavijñāna not only arises-and-ceases but also neither-arises-nor-ceases, just like the ocean that contains [the natures of] moving and stillness; the fourth, nescience and deluded attachments neither arise-and-cease nor neither-arise-nor-cease, just like arising waves and strong wind are neither water nor waves.” Fazang also states that tathāgatagarbha maintains the nature of neither-arising-nor-ceasing even when it is involved in the abode of arising-and-ceasing (C. shengmie men 生滅門). See the Yiji T1846:44.255b13-15: 非直梨耶具動靜在此生滅中。亦乃如來藏 唯不動亦在此門中. “It is not just that ālayavijñāna, which has [both natures of] moving and stillness, belongs to [the abode of] arising-and-ceasing; rather tathāgatagarbha, which never move, also belongs to this abode.” |

| 25 | Wŏnhyo explains the neither-identical-nor-different [condition], in which the two types of mind are unified, as twofold, by saying, “As for ‘the neither-identical-nor-different [condition],’ [on the one hand,] the neither-arising-nor-ceasing mind moves its essence, and thus this mind is not different from the arising-and-ceasing [mind]. Yet, [on the other hand, the mind] does not lose the neither-arising-nor-ceasing nature and thus the arising-and-ceasing [mind] is not identical to the [neither-arising-nor-ceasing] mind.” See the Kisillon so T1844:44.208b20-22: 非一非異者。不生滅心舉體而動。故心與生滅非異。而恒不失不生滅性。故生滅與心非一。In other words, the two types of minds are said to be unified in a not-different or in a not-identical condition, depending on whether tathāgatagarbha (or, the neither-arising-nor-ceasing mind) moves its essence in accordance with the arising-and-ceasing mind or keeps its neither-arising-nor-ceasing nature. In this passage, the implication is that the nature of tathāgatagarbha consists of two distinct aspects, and the twofold condition of the unification in ālayavijñāna is explained based on these aspects. In fact, Fazang cites this same passage by Wŏnhyo in the equivalent place of the Yiji. However, the implication is different: The nature of tathāgatagarbha has only the neither-arising-nor-ceasing nature, and thus, for Fazang, the twofold unification in ālayavijñāna is determined depending on whether this neither-arising-nor-ceasing tathāgatagarbha is non-identical to or non-different from the arising-and-ceasing mind. A more detailed discussion shall follow below in the main text. |

| 26 | See the Pyŏlgi T1845:44.228c25-26: 雖有二義。心體無二。此合二義不二之心。名為梨耶識也. |

| 27 | See the Kisillon so T1844:44.208b22-26: 又若是一者。生滅識相滅盡之時。心神之體亦應隨滅。墮於斷邊。若是異 者。依無明風熏動之時。靜心之體不 應隨緣。即墮常邊。離此二邊。故非一非異. Fazang also states a similar passage in the Yiji (T1846:44.255b16-19: 又若一者。生滅識相滅盡之時。真心應滅。則墮斷過。若是異者。依無 明風熏動之時。靜心之體應不隨緣。則墮常過。離此二邊故非一異). However, as discussed above, Fazang’s understanding of tathāgatagarbha is different from Wŏnhyo’s, and his interpretation of the unification in ālayavijñāna, which is based on his understanding of tathāgatagarbha, also has a different implication than Wŏnhyo’s. More discussion will follow soon. |

| 28 | The seemingly inconsistent statements of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra on the relationship between ālayavijñāna and tathāgatagarbha appear only in the Ru lengqie jing, Bodhiruci’s 10-fascicle recension. The passage, in which ālayavijñāna is identified as tathāgatagarbha, reads, “Mahāmati! Ālayavijñāna is named tathāgatagarbha and coexists with the seven consciousnesses in delusion.” See the Ru lengqie jing T671:16.556b29-c01: 大慧! 阿梨 耶識者,名如來藏,而與無明七識共俱. Soon after this passage, it states, “Mahāmati! Tathāgatagarbha consciousness does not reside in ālayavijñāna; therefore, the seven kinds of consciousness arise and cease and tathāgatagarbha neither arise nor cease.” See the Ru lengqie jing T671:16.556c11-13: 大慧! 如來藏識 不在阿梨 耶識中,是故七種識有生有滅,如來藏識不生不滅. In Guṇabhadra’s translation in the four-fascicle, the Lengqie abatuoluo baojing, ālayavijñāna is consistently identified with tathāgatagarbha. See the Lengqie abatuoluo baojing T670:16.511b07-19; 512b06-08. For a detailed explanation of the difference in the two recensions, see Fuji (1964, pp. 154–55). |

| 29 | In commenting on the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra’s passage in which tathāgatagarbha consciousness does not reside in ālayavijñāna (the Ru lengqie jing T671:16.556b29-c01; see footnote 28 above), Wŏnhyo makes a distinction between the seven consciousnesses and tathāgatagarbha by describing them as arising-and-ceasing and neither-arising-nor-ceasing, respectively (See the Pyŏlgi T1845:44.229c28-230a04: 十卷意者。欲明七識。 是浪不非海相。在梨耶識海中故有生滅。如來藏者。是海非浪。不在阿梨耶識海中故無生滅。故言如來藏不在阿梨耶識中。是故七識。有生有滅等。以如來藏即是阿梨耶識故。言不在). On the contrary, regarding the passage in which ālayavijñāna is named tathāgatagarbha (the Ru lengqie jing T671:16.556b29-c01; see footnote 28 above), Wŏnhyo says that this sentence clarifies the neither-arising-nor-ceasing nature of the original enlightenment inherent in ālayavijñāna (See the Pyŏlgi T1845:44.230a07-10: 又四卷經云。阿梨耶識名如來藏 。而與無明七識共俱。離無常過。自性清淨。餘七識者。念念不住。是生滅法。如是等文。同明梨耶本覺不生滅義). Although Wŏnhyo says that this passage is stated in the four-fascicle Sūtra, which is a mistake, it appears in the 10-fascicle recension. See the Ru lengqie jing T671:16.556b29-c04: 大慧! 阿梨耶識者,名如來 藏,而與無明七識共俱,如大海波常不斷絕身俱生故,離無常過離於我過自性清淨,餘七識者,心、意、意識等念念不住是生滅法. Moreover, Wŏnhyo also explains, in another place, the passages of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra from both approaches of a non-identical nature (K. purirŭimun 不一義門) and non-different nature (K. puriŭimun 不異義門). The distinction between the self-true character (K. chajinsang 自眞相) and the evolving character (K. chŏnsang 轉相) of ālayavijñāna is explained from the approach of a non-identical nature, while the identity of the nature of numinous realization (K. sinhae 神解) in the arising-and-ceasing and the self-true character is interpreted from the approach of a non-different nature. See the Kisillon so T1844:44.208c06-12: 如十卷經言。如來藏即阿梨耶識。共七識生。名轉滅相。故知轉相在梨耶識。自眞相者。十卷經云中眞名自相。本覺之心。不藉妄緣。性自神解名自眞相。是約不一義門說也。又隨無明風作生滅時。神解之性與本不異。故亦得名為自眞相。是依不異義門說也. |

| 30 | See the Yiji T1846:44. 254c04: 此說。此顯眞心隨動。故作生滅. |

| 31 | More explanations shall follow below. |

| 32 | The four levels of the teachings are as follows: the teaching of attachment to dharmas following their characteristics (C. Suixiang fazhi zong 隨相法執宗), the teaching of no-characteristics in true emptiness (C. Zhenkong wuxiang zong 眞空無相宗), the teaching of dharma characteristics in consciousness-only (C. Weishi faxiang zong 唯識法相宗), and the teaching of the dependent origination of tathāgatagarbha (C. Rulaizang yuanqi zong 如來藏緣起宗); see the Yiji T1846:44.243b22-28: 第二隨教辨宗者。現今東流一切經論。通大小乘 。宗途有四。一隨相法執宗。即小乘諸部是也。二眞空無相宗。即般若等經。中觀等論所說是也。三唯識法相宗。即解深密等經。瑜伽等論所說是也。四如來藏緣起宗。即楞伽密嚴等經。起信寶性等論所說是也. |

| 33 | See the Yiji T1846:44.243b28-c03: 此四之中。初則隨事執相說。二則會事顯理說。三則依理起事差別說。 四則理事融通無礙說。以此宗中許如來藏隨緣成阿賴耶識。此則理徹於事也。亦許依他緣起無性同如。此則 事徹於理也. |

| 34 | See footnote 33 above. |

| 35 | See the Yiji T1846:44.254c24255b07. In this passage, Fazang explains the unification in ālayavijñāna by introducing not only the truth and delusion, but also the origin and derivative (C. benmo 本末), as another pair with the same connotation. In fact, Yoshizu Yoshihide, in his insightful article (1983) on the Huayan notion of interfusion between the nature and the characteristics (C. xingxiang ronghui 性相融通), demonstrates that a series of paired notions, such as the mutual penetration of the truth and delusion (C. zhenwang jiaoche 眞妄交徹), the non-obstruction between the principle and phenomena (C. lishi wuai 理事無礙), the interfusion between the nature and characteristics, and the equality of the origin and derivatives (C. benmo pingdeng 本末平等), all have the same connotations in Fazang’s works. For detailed information, see Yoshizu (1983). |

| 36 | See footnote 28 above. |

| 37 | As Wŏnhyo also does, Fazang relates the sutra’s statement that tathāgatagarbha and ālayavijñāna are separate from each other to the non-identical (C. buyi 不一) condition between the truth and delusion (see the Yiji T1846:44.255a14-18: 第二不一義者。即以前攝末之本唯不生滅故。與彼攝本之末唯生滅法而不一也。依是義 故。經云。如來藏者。不在阿梨耶中。是故七識有生有滅。如來藏者不生不滅); he associates the statement that they are identical to the non-different (C. buyi 不異) condition between them (see the Yiji T1846:44.255a09-12: 三本末平等明不異者。經云。甚深如來藏。而與七識俱。又經云。何梨耶識名如來藏。 而與無明七識共俱。如大海波常不斷絶). |

| 38 | See the Yiji T1846:44.255c18-256a13: 前中言此識有二義等者。此義稍難。今總括上下文略敘其意。 餘可至文 當知。何者。謂眞如有二義。一不變義。二隨緣義。無明亦二義。一無體即空義。二有用成事義。此眞妄中。 各由初義故成上眞如門也。各由後義故成此生滅門也。此隨緣眞如及成事無明亦各有二義。一違自順他義。二違他順自義。無明中初違自順他亦有二義。一能反對詮示性功德。二能知名義成淨用。違他順自亦有二義。一覆眞理。二成妄心。眞如中違他順自亦有二義。一翻對妄染顯自德。二內熏無明起淨用。違自順他亦有二義。一隱自眞體義。二顯現妄法義。此上眞妄各四義中由無明中反對詮示義。及眞如中翻妄顯德義。從此二義得有本覺。又由無明中能知名義。及眞如中內熏義。從此二義得有始覺。又由無明中覆眞義。眞如中隱體義。從此二義得有根本不覺。又由無明中成妄義。及眞如中現妄義。從此二義得有枝末不覺。此生滅門中。眞妄略開四義。廣即有八門。若約兩兩相對和合成緣起。即有四門。謂二覺二不覺。若約本末不相離。唯有二門。謂覺與不覺。若鎔融總攝。唯有一門。謂一心生滅門也. |

| 39 | This figure was originally composed by Whalen Lai (1980, p. 252) in his article titled “the I-ching and the Formation of the Hua-yen Philosophy.” Here, I have added the part of the abode of Thusness and made some modifications in English translations. I introduce this figure to facilitate the understanding of the reciprocal interfusion between truth and delusion, or Thusness and nescience, described in this passage. |

| 40 | Whalen Lai (1980, pp. 252–55) also argues that Fazang’s doctrines were influenced by ontological metaphysics of classical Chinese philosophy, such as that of the Yijing 易經, by indicating a similarity between Fazang’s scheme of the mutual permeation of Thusness and delusion and Yijing’s “One-Two-Four-Eight” diagram, which stands for evolutionary process of phenomena from the one supreme principle. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S. On the Ālayavijñāna in the Awakening of Faith: Comparing and Contrasting Wŏnhyo and Fazang’s Views on Tathāgatagarbha and Ālayavijñāna. Religions 2019, 10, 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10090536

Lee S. On the Ālayavijñāna in the Awakening of Faith: Comparing and Contrasting Wŏnhyo and Fazang’s Views on Tathāgatagarbha and Ālayavijñāna. Religions. 2019; 10(9):536. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10090536

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sumi. 2019. "On the Ālayavijñāna in the Awakening of Faith: Comparing and Contrasting Wŏnhyo and Fazang’s Views on Tathāgatagarbha and Ālayavijñāna" Religions 10, no. 9: 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10090536

APA StyleLee, S. (2019). On the Ālayavijñāna in the Awakening of Faith: Comparing and Contrasting Wŏnhyo and Fazang’s Views on Tathāgatagarbha and Ālayavijñāna. Religions, 10(9), 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10090536