Big Five Personality Traits and Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Religiosity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Personality and Life Satisfaction

1.2. Personality and Religiosity

1.3. Personality, Life Satisfaction, and Religiosity

1.4. Research Problem and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Assessment of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO FFI)

2.5. Assessment of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

2.6. Assessment of the Positivity Scale (PS)

2.7. Assessment of the Personal Religiousness Scale (PRS)

2.8. Assessment of the Intensity of Religious Attitude Scale (IRAS)

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Correlation Analysis

3.3. Multicollinearity and Confounding Variables

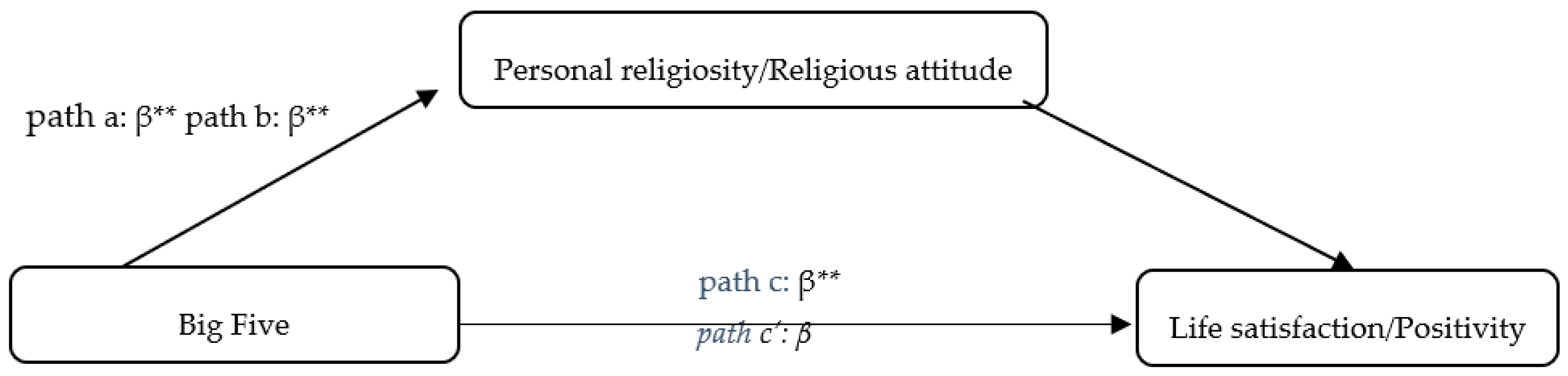

3.4. Mediational Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aghababaei, Naser. 2014. God, the Good Life, and HEXACO: The Relations among Religion, Subjective Well-Being and Personality. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17: 284–90. [Google Scholar]

- Aghababaei, Naser, Jason Adam Wasserman, and Drew Nannini. 2014. The Religious Person Revisited: Cross-Cultural Evidence from HEXACO Model of Personality Structure. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17: 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Agler, Robert, and Paul De Boeck. 2017. On the Interpretation and Use of Mediation: Multiple Perspectives on Mediation Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, Herman, Jeffrey R. Edwards, and Kyle J. Bradley. 2017. Improving Our Understanding of Moderation and Mediation in Strategic Management Research. Organizational Research Methods 20: 665–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Samantha F., Ken Kelley, and Scott E. Maxwell. 2017. Sample-Size Planning for More Accurate Statistical Power: A Method Adjusting Sample Effect Seizes for Publication Bias and Uncertainty. Psychological Science 28: 1547–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, Clifton E. 2014. Is Religiosity a Protective Factor for Mexican-American Filial Caregivers? Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging 26: 245–58. [Google Scholar]

- Berthold, Anne, and Willibald Ruch. 2014. Satisfaction with Life and Character Strengths of Non-Religious and Religious People: It’s Practicing One’s Religion that Makes the Difference. Frontiers in Psychology 5: 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błachnio, Agata, and Aneta Przepiórka. 2016. Personality and Positive Orientation in Internet and Facebook Addiction. An Empirical Report from Poland. Computers in Human Behavior 59: 230–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brief, Arthur P., Ann Houston Butcher, Jennifer M. George, and Karen E. Link. 1993. Integrating Bottom-Up and Top-Down Theories of Subjective Well-Being: The Case of Health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64: 646–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, Gian Vittorio. 2009. Positive Orientation: Turning Potentials into Optimal Functioning. The Bulletin of the European Health Psychologist 11: 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara, Gian Vittorio, Guido Alessandri Guido, Gisela Trommsdorff, Tobias Heikamp, Susumu Yamaguchi, and Fumiko Suzuki. 2012a. Positive Orientation Across Three Cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 43: 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, Gian Vittorio, Guido Alessandri, Nancy Eisenberg, A. Kupfer, Patrizia Steca, Maria Giovanna Caprara, Susumu Yamaguchi, Ai Fukuzawa, and John Abela. 2012b. The Positivity Scale. Psychological Assessment 24: 701–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwuorji, JohnBosco Chika, Ezichi Anya Ituma, and Lawrence Ejike Ugwu. 2018. Locus of Control and Academic Engagement: Mediating Role of Religious Commitment. Current Psychology 37: 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Paul T., and Robert R. McCrae. 1980. Influence of Extraversion and Neuroticism on Subjective Well-Being: Happy and Unhappy People. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 38: 668–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Paul T., and Robert R. McCrae. 1989. The NEO-PI/NEO-FFI Manual Supplement. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Paul T., Robert McCrae, and David A. Dye. 1991. Facet Scales for Agreeableness and Conscientiousness: A Revision of the NEO Personality Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences 12: 887–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNeve, Kristina M., and Harris Cooper. 1998. The Happy Personality: A Meta-Analysis of 137 Personality Traits and Subjective Well-Being. Psychological Bulletin 124: 197–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed. 1998. Subjective Well-Being and Personality. In Advanced Personality. Edited by David F. Barone, Michel Hersen and Vincent B. Van Hasselt. New York: Plenum, pp. 311–34. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, Ed, Robert A. Emmons, Randy J. Larsen, and Sharon Griffin. 1985. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49: 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Shigehiro Oishi, and Richard E. Lucas. 2003. Personality, Culture, and Subjective Well-Being: Emotional and Cognitive Evaluations of Life. Annual Review of Psychology 54: 403–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, Paul, Tessa Peasgood, and Mathew White. 2008. Do We Really Know What Makes Us Happy? A Review of the Economic Literature on the Factors Associated with Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Economic Psychology 29: 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duriez, Bart, Bart Soenens, and Wim Beyers. 2004. Personality, Identity Styles, and Religiosity: An Integrative Study Among Late Adolescents in Flanders (Belgium). Journal of Personality 72: 877–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, Robert A. 2005. Striving for the Sacred: Personal Goals, Life Meaning, and Religion. Journal of Social Issues 61: 731–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, Michael W. 1998. Personality and the Psychology of Religion. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 1: 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild, Amanda J., and David MacKinnon. 2009. A General Model for Testing Mediation and Moderation Effects. Prevention Science 10: 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, Franz, Edgar Erdfelder, Albert-Georg Lang, and Axel Buchner. 2007. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behavior Research Methods 39: 175–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, Franz, Edgar Erdfelder, Axel Buchner, and Albert-Georg Lang. 2009. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behavior Research Methods 41: 1149–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, Joseph R., Jordan Reed, and Mayra Guerrero. 2017. Personality as Predictor of Religious Commitment and Spiritual Beliefs: Comparing Catholic Deacons and Men in Formation. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health 19: 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidell, Linda S., and Barbara G. Tabachnick. 2003. Preparatory Data Analysis. In Handbook of Psychology: Research Methods in Psychology. Edited by John A. Schinka, Wayne F. Velicer and Irving B. Weiner. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 115–141. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Leslie J. 1992. Is Psychoticism Really a Dimension of Personality Fundamental to Religiosity? Personality and Individual Differences 13: 645–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Luis F., Anton Aluja, Óscar García, and Lara Cuevas. 2005. Is Openness to Experience an Independent Personality Dimension? Convergent and Discriminant Validity of the Openness Domain and its NEO-PI-R Facets. Journal of Individual Differences 26: 132–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Darren, and Paul Mallery. 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics 23 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, Veronica, Franciska Krings, Adrian Bangerter, and Alexander Grob. 2009. The Influence of Personality and Life Events on Subjective Well-Being from a Life Span Perspective. Journal of Research in Personality 43: 345–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Shang E., and Seokho Kim. 2013. Personality and Subjective Well-Being: Evidence from South Korea. Social Indicators Research 111: 341–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, Dianne Gabriela, Casswina Donald, and Gerard Hutchinson. 2018. Religion and Life Satisfaction: A Correlational Study of Undergraduate Students in Trinidad. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 1567–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahs-Vaughn, Debbie L. 2017. Applied Multivariate Statistical Concepts. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Heidemeier, Heike, and Anja S. Göritz. 2016. The Instrumental Role of Personality Traits: Using Mixture Structural Equation Modeling to Investigate Individual Differences in the Relationships Between the Big Five Traits and Life Satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies 17: 2595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henningsgaard, Jude M., and Randolph C. Arnau. 2008. Relationships between Religiosity, Spirituality, and Personality: A Multivariate Analysis. Personality and Individual Differences 45: 703–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, Peter, Leslie J. Francis, Michael Argyle, and Chris J. Jackson. 2004. Primary Personality Trait Correlates of Religious Practice and Orientation. Personality and Individual Differences 36: 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounkpatin, Hilda Osafo, Christopher J. Boyce, Graham Dunn, and Alex M. Wood. 2018. Modeling Bivariate Change in Individual Differences: Prospective Associations Between Personality and Life Satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 115: 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, Romuald. 1989. Psychologiczne korelaty religijności personalnej. Lublin: KUL. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski, Romuald. 2002. Psychologiczna analiza religijności w perspektywie komunikacji interpersonalnej. Studia Psychologica 3: 143–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm, Anthony F., and Helen Christensen. 2004. Religiosity and Personality: Evidence for Non-Linear Associations. Personality and Individual Differences 36: 1433–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, Mohsen, and Samaneh Afshari. 2011. Big Five Personality Traits and Self-Esteem as Predictors of Life Satisfaction in Iranian Muslim University Students. Journal of Happiness Studies 12: 105–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Zygfryd. 2001. Narzędzia pomiaru w promocji psychologii zdrowia. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Harold G., Dana E. King, and Verna Benner Carson. 2012. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kortt, Michael A., Brian Dollery, and Bligh Grant. 2015. Religion and Life Satisfaction Down Under. Journal of Happiness Studies 16: 277–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krok, Dariusz. 2014. The Mediating Role of Coping in the Relationships Between Religiousness and Mental Health. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 2: 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaguna, Mariola, Piotr Oleś, and Dorota Filipiuk. 2011. Orientacja pozytywna i jej pomiar: Polska adaptacja Skali Orientacji Pozytywnej. Studia Psychologiczne 49: 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lahey, Benjamin B. 2009. Public Health Significance of Neuroticism. American Psychologist 64: 241–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, Daniël. 2013. Calculating and Reporting Effect Sizes to Facilitate Cumulative Science: A Practical Primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology 4: 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Christopher Alan, John Maltby, and Liz Day. 2005. Religious Orientation, Religious Coping and Happiness among UK Adults. Personality and Individual Differences 38: 1193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomax, Richard G., and Debbie L. Hahs-Vaughn. 2012. An Introduction to Statistical Concepts. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, Richard E., Kimdy Le, and Portia S. Dyrenforth. 2008. Explaining the Extraversion/Positive Affect Relation: Sociability Cannot Account for Extraverts’ Greater Happiness. Journal of Personality 76: 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, Maike, Richard E. Lucas, Michael Eid, and Ed Diener. 2013. The Prospective Effect of Life Satisfaction on Life Events. Social Psychological and Personality Science 4: 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, David P., JeeWon Cheong, and Angela G. Pirlott. 2012. Statistical Mediation Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Edited by Harris Cooper. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 313–31. [Google Scholar]

- Maltby, John, Christopher Alan Lewis, and Liza Day. 1999. Religious Orientation and Psychological Well-Being: The Role of the Frequency of Personal Prayer. British Journal of Health Psychology 4: 363–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, John, Liz Day, and Ann Macaskill. 2007. Introduction to Personality, Individual Differences and Intelligence. Essex: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Martell, Richard F., David M. Lane, and Cynthia Emrich. 1996. Male-Female Differences: A Computer Simulation. American Psychologist 51: 157–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, Scott E., and David A. Cole. 2007. Bias in Cross-Sectional Analyses of Longitudinal Mediation. Psychological Methods 12: 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, Robert R. 1999. Mainstream Personality Psychology and the Study of Religion. Journal of Personality 67: 1209–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, Mehmet, and Tor Georg Jakobsen. 2017. Applied Statistics Using STATA: A Guide for the Social Sciences. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Miciuk, Łukasz Roland, Tomasz Jankowski, Agnieszka Laskowska, and Piotr Oleś. 2016. Positive Orientation and the Five-Factor Model. Polish Psychological Bulletin 47: 141–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Morgan, George A., and Orlando V. Griego. 1998. Easy Use and Interpretation of SPSS for Windows: Answering Research Questions with Statistics. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament, Kenneth I. 1997. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Crystal L. 2007. Religiousness/Spirituality and Health: A Meaning Systems Perspective. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 30: 319–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhoseingholi, Mohamad Amin, Ahmad Reza Baghestani, and Mohsen Vahedi. 2012. How to Control Confounding Effects by Statistical Analysis. Gastroenterology and Hepatology from Bed to Bench 5: 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prężyna, Władysław. 1968. Skala Postaw Religijnych. Roczniki Filozoficzne 16: 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Prężyna, Władysław, and Teresa Kwaśniewska. 1974. Powiązanie postawy religijnej i osobowości analizowanej w świetle danych Inwentarza Psychologicznego H. G. Gougha. Roczniki Filozoficzne 22: 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Przepiorka, Aneta, Nicolson Yat-fan Siu, Małgorzata Szcześniak, Celina Timoszyk-Tomczak, Jacqueline Jiaying Le, and Mónica Pino Muñoz. 2019. The Relationship Between Personality, Time Perspective and Positive Orientation in Chile, Hong Kong, and Poland. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosellini, Anthony J., and Timothy A. Brown. 2011. The NEO Five-Factor Inventory: Latent Structure and Relationships with Dimensions of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in a Large Clinical Sample. Assessment 18: 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis. 2002. Religion and the Five Factors of Personality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Personality and Individual Differences 32: 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis. 2010. Religiousness as a Cultural Adaptation of Basic Traits: A Five-Factor Model Perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14: 108–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroglou, Vassilis. 2015. Personality and Religion. In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Edited by James D. Wright. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 801–8. [Google Scholar]

- Saroglou, Vassilis, and Antonio Muñoz-García. 2008. Individual Differences in Religion and Spirituality: An Issue of Personality Traits and/or Values. Journal of the Scientific Study of Religion 47: 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, Ulrich, Shigehiro Oishi, R. Michael Furr, and David Funder. 2004. Personality and Life Satisfaction: A Facet-Level Analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30: 1062–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, Tatjana. 2012. Spirituality with and without Religion—Differential Relationships with Personality. Archive for the Psychology of Religion 34: 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnewe, Elisabeth, Michael A. Kortt, and Brian Dollery. 2015. Religion and Life Satisfaction: Evidence from Germany. Social Indicators Research 123: 837–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śliwak, Jacek, and Rafał P. Bartczuk. 2011. Skala Intensywności Postawy Religijnej. In Psychologiczny pomiar religijności. Edited by Marek Jarosz. Lublin: Towarzystwo Naukowe KUL, pp. 153–68. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, Christopher J., Oliver P. John, Samuel D. Gosling, and Jeff Potter. 2011. Age Differences in Personality Traits From 10 to 65: Big Five Domains and Facets in a Large Cross-Sectional Sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100: 330–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, Susan C., Amber M. Jarnecke, and Colin E. Vize. 2018. Sex Differences in the Big Five Model Personality Traits: A Behavior Genetics Exploration. Journal of Research in Personality 74: 158–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Piers, Joseph Schmidt, and Jonas Shults. 2008. Refining the Relationship Between Personality and Subjective Well-Being. Psychological Bulletin 134: 138–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Michael F., and Patricia Frazier. 2005. Meaning in Life: One Link in the Chain from Religiousness to Well-Being. Journal of Counseling Psychology 52: 574–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, Maciej, and Gerald Matthews. 2016. Time Perspectives Predict Mood States and Satisfaction with Life over and above Personality. Current Psychology 35: 516–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Kieran. 2001. Understanding the Relationship between Religiosity and Marriage: An Investigation of the Immediate and Longitudinal Effects of Religiosity on Newlywed Couples. Journal of Family Psychology 15: 610–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szcześniak, Małgorzata, Grażyna Bielecka, Iga Bajkowska, Anna Czaprowska, and Daria Madej. 2019. Religious/Spiritual Struggles and Life Satisfaction among Young Roman Catholics: The Mediating Role of Gratitude. Religions 10: 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Andrew, and Douglas A. MacDonald. 1999. Religion and the Five Factor Model of Personality: An Exploratory Investigation Using a Canadian University Sample. Personality and Individual Differences 27: 1243–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ten Kate, Josje, Willem de Koster, and Jeroen van der Waal. 2017. The Effect of Religiosity on Life Satisfaction in a Secularized Context: Assessing the Relevance of Believing and Belonging. Review of Religious Research 59: 135–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, Christopher Glen, Rae Seon Kim, Ariel M. Aloe, and Betsy Jane Becker. 2017. Extracting the Variance Inflation Factor and Other Multicollinearity Diagnostics from Typical Regression Results. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 39: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Lili, Dandan Zhang, and E. Scott Huebner. 2018. Psychometric Properties of the Positivity Scale among Chinese Adults and Early Adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unterrainer, Human Friedrich, Karl Heinz Ladenhauf, Maryam Laura Moazedi, Sandra Johanna Wallner-Liebmann, and Andreas Fink. 2010. Dimensions of Religious/Spiritual Well-Being and their Relation to Personality and Psychological Well-Being. Personality and Individual Differences 49: 192–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vater, Aline, and Michela Schröder-Abé. 2015. Explaining the Link Between Personality and Relationship Satisfaction: Emotion Regulation and Interpersonal Behaviour in Conflict Discussions. European Journal of Personality 29: 201–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidmann, Rebekka, Thomas Ledermann, and Alexander Grob. 2017. Big Five Traits and Relationship Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem. Journal of Research in Personality 69: 102–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, Paul, Lucia Ciciolla, Michele Dillon, and Allison J. Tracy. 2007. Religiousness, Spiritual Seeking, and Personality: Findings from a Longitudinal Study. Journal of Personality 75: 1051–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Le, Ru-De Liu, Yi Ding, Xiaohong Mou, Jia Wang, and Ying Liu. 2017. The Mediation Effect of Coping Style on the Relations between Personality and Life Satisfaction in Chinese Adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeniaras, Volkan, and Tugra Nazli Akarsu. 2017. Religiosity and Life Satisfaction: A Multi-dimensional Approach. Journal of Happiness Studies 18: 1815–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycka, Beata, Dominika Ziółkowska, and Jacek Śliwak. 2017. Religious Support and Religious Struggle as Predictors of Quality of Life in Alcoholics Anonymous—Moderation by Duration of Abstinence. Roczniki Psychologiczne 20: 121–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzki, Bogdan, Jan Strelau, Piotr Szczepaniak, and Magdalena Śliwińska. 1998. Inwentarz Osobowości NEO-FFI Costy i McCrae. Adaptacja polska. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych PTP. [Google Scholar]

| Scales | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NE | 35.92 | 9.66 | −0.018 | −0.332 |

| 2. EX | 39.29 | 6.91 | −0.318 | 0.040 |

| 3. OP | 39.04 | 6.44 | 0.271 | −0.139 |

| 4. AG | 41.60 | 6.21 | −0.255 | −0.188 |

| 5. CO | 43.49 | 7.41 | −0.203 | −0.293 |

| 6. LS | 21.21 | 5.64 | −0.212 | −0.308 |

| 7. PO | 28.21 | 5.05 | −0.738 | 1.022 |

| 8. FA | 26.21 | 7.11 | −0.028 | −0.568 |

| 9. MO | 21.50 | 7.38 | −0.257 | −0.927 |

| 10. RP | 28.62 | 9.33 | 0.151 | −0.991 |

| 11. RS | 20.08 | 5.89 | −0.363 | −0.530 |

| 12. PR | 96.42 | 27.97 | −0.083 | −0.949 |

| 13. RA | 98.13 | 31.44 | −0.606 | −0.406 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NE | |||||||||||||

| 2. EX | −0.509 ** | ||||||||||||

| 3. OP | −0.062 | 0.011 | |||||||||||

| 4. AG | −0.240 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.071 | ||||||||||

| 5. CO | −0.371 ** | 0.366 ** | −0.040 | 0.222 ** | |||||||||

| 6. LS | −0.433 ** | 0.492 ** | −0.010 | 0.293 ** | 0.367 ** | ||||||||

| 7. PO | −0.536 ** | 0.598 ** | 0.022 | 0.320 ** | 0.544 ** | 0.631 ** | |||||||

| 8. FA | −0.041 | 0.237 ** | −0.243 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.061 | 0.234 ** | 0.137 * | ||||||

| 9. MO | −0.023 | 0.342 ** | −0.221 ** | 0.271 ** | 0.188 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.261 ** | 0.805 ** | |||||

| 10. RP | −0.033 | 0.214 ** | −0.227 ** | 0.298 ** | 0.113 t | 0.213 ** | 0.202 ** | 0.879 ** | 0.833 ** | ||||

| 11. RS | −0.065 | 0.245 ** | −0.234 ** | 0.201 ** | 0.100 | 0.258 ** | 0.200 ** | 0.867 ** | 0.804 ** | 0.876 ** | |||

| 12. PR | −0.041 | 0.274 ** | −0.245 ** | 0.272 ** | 0.124 t | 0.268 ** | 0.213 ** | 0.943 ** | 0.916 ** | 0.962 ** | 0.936 ** | ||

| 13. RA | −0.022 | 0.282 ** | −0.283 ** | 0.252 ** | 0.154 * | 0.280 ** | 0.250 ** | 0.812 ** | 0.855 ** | 0.788 ** | 0.818 ** | 0.868 ** |

| a path | b path | c path | c’ path | Indirect Effect and B (SE) | 95% CI LOWER UPPER | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NE—PR—LS | −0.11 (ni) | −0.05 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.0060 (0.0108) | −0.0289; 0.0137 |

| 2. NE—RA—LS | −0.07 (ni) | 0.04 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.0034 (0.0126) | −0.0303; 0.0208 |

| 3. EX—PR—LS | 1.10 *** | 0.03 * | 0.40 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.0323 (0.0168) | 0.0036; 0.0690 |

| 4. EX—RA—LS | 1.28 *** | 0.03 * | 0.40 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.0353 (0.0181) | 0.0050; 0.0753 |

| 5. OP—PR—LS | −1.06 *** | 0.05 *** | −0.01 (ni) | 0.05 (ni) | −0.0608 (0.0223) | −0.1080; −0.0222 |

| 6. OP—RA—LS | −1.37 *** | 0.06 *** | −0.01 (ni) | 0.06 (ni) | −0.0746 (0.0254) | −0.1286; −0.0302 |

| 7. AG—PR—LS | 1.22 *** | 0.04 ** | 0.26 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.0503 (0.0215) | 0.0024; 0.0166 |

| 8. AG—RA—LS | 1.27 *** | 0.03 ** | 0.26 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.0504 (0.0200) | 0.0142; 0.0918 |

| 9. CO—PR—LS | 0.46 (ni) | 0.04 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.0214 (0.0143) | −0.0028; 0.0523 |

| 10. CO—RA—LS | 0.65 ** | 0.04 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.0269 (0.0156) | 0.0012; 0.0617 |

| a Path | b Path | c Path | c’ Path | Indirect Effect and B (SE) | 95% CI LOWER UPPER | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NE—PR—PO | −0.11 (ni) | −0.03 *** | −0.28 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.0041 (0.0076) | −0.0212; 0.0097 |

| 2. NE—RA—PO | −0.07 (ni) | 0.04 *** | −0.28 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.0027 (0.0097) | −0.0232; 0.0160 |

| 3. EX—PR—PO | 1.10 *** | 0.01 (ni) | 0.43 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.0108 (0.0118) | −0.0111; 0.0359 |

| 4. EX—RA—PO | 1.28 *** | 0.01 (ni) | 0.43 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.0183 (0.0139) | −0.0058; 0.0483 |

| 5. OP—PR—PO | −1.06 *** | 0.01 (ni) | 0.01 (ni) | 0.06 (ni) | −0.0447 (0.0199) | −0.0897; −0.0124 |

| 6. OP—RA—PO | −1.37 *** | 0.04 *** | 0.01 (ni) | 0.07 (ni) | −0.0616 (0.0218) | −0.1083; −0.0238 |

| 7. AG—PR—PO | 1.22 *** | 0.02 * | 0.26 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.0302 (0.0175) | −0.0001; 0.0690 |

| 8. AG—RA—PO | 1.27 *** | 0.03 ** | 0.26 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.0371 (0.0181) | 0.0057; 0.0782 |

| 9. CO—PR—PO | 0.46 (ni) | 0.02 * | 0.37 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.0125 (0.0094) | −0.0013; 0.0348 |

| 10. CO—RA—PO | 0.65 * | 0.02 * | 0.37 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.0179 (0.0115) | 0.0003; 0.0043 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szcześniak, M.; Sopińska, B.; Kroplewski, Z. Big Five Personality Traits and Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Religiosity. Religions 2019, 10, 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10070437

Szcześniak M, Sopińska B, Kroplewski Z. Big Five Personality Traits and Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Religiosity. Religions. 2019; 10(7):437. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10070437

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzcześniak, Małgorzata, Blanka Sopińska, and Zdzisław Kroplewski. 2019. "Big Five Personality Traits and Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Religiosity" Religions 10, no. 7: 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10070437

APA StyleSzcześniak, M., Sopińska, B., & Kroplewski, Z. (2019). Big Five Personality Traits and Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Religiosity. Religions, 10(7), 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10070437