Abstract

This paper challenges the Japanese word mushūkyō as it is used to create a collective, non-religious identity that excludes religious practitioners. Mushūkyō, in addition to functioning as the antithesis of religion, produces the homogeneity Japanese desire for themselves. As Japan becomes increasingly more diverse in thought and ethnic background, it regulates this diversity by teaching young Japanese to subscribe to mushūkyō. This is achieved by controlling the friendships children have at school and by creating an environment that limits religious practice. The conflict between public schools and religion is epitomized by the Roman Catholic Church and the flight of its children. Nearly a decade of quantitative research at a Catholic Church located in the Tokyo suburbs is combined with ethnographic narratives of four Catholics to paint a picture of a Japanese more religiously partisan than previously imagined.

1. Introduction

My fortieth birthday began with a rough start. In September, I received a call from my credit card company saying someone had unlawfully used my account. In November, I hit a bicyclist going the wrong way on a one-way street (minor injury), for which I was sent to driving school, where despite having already driven on an international license, I failed three times (Japan is strict!). During this ordeal, I also came down with a cold to add to my perennial battle with frostbite (Japan’s floors are cold in winter). My wife provided her solution—a trip to the local shrine. I had begun to climb the proverbial ‘hill’ to middle age and instead of receiving a party or a black mug with an unwarranted reminder of my impending death, I was sent to the local Shinto shrine for a yakutoshi blessing.

It is not often that Japanese discuss religion. In my wife’s case, she never does. She is what many would identify as non-religious (mushūkyō hereafter), but this does not mean religion plays no part in her life. Despite not speaking about religion, she participates in many of the same activities. Hardacre (2017) describes in her list of Japanese religious acts: Maintaining a kamidana and butsudan altar, “first visits” to Shinto Shrines on New Year, baby blessings (hatsu miya mairi), and visits to pray for a child’s safety while growing into maturity (shichi-go-san) (pp. 513–23). All these make her seem ordinary compared with other Japanese.

In Japan, this relationship between believed and lived religion (McGuire 2008) is not perceived as contradictory because religious actions have “acquired such a customary and traditional nature that Japanese would not immediately think of them as ‘religion’ (shūkyō), a term that people tend to associate with a set of specific doctrines and requirements to affirm a doctrinal creed” (Reader and Tanabe 1998; Molle 2011; Josephson 2012; Zuckerman et al. 2016, p. 40; Hardacre 2017, p. 517). Despite many Japanese remarking they “personally do not regard religion as playing a central role in their own lives or in Japan’s public life”—it certainly does (Hardacre 2017, p. 513; Kobayashi 2019; LeMay 2018a; Iwai 2004; Tajima 2008). This is the issue at hand. How does this association-with-religion-in-practice-but-not-in-word impact Japan’s relationship with its religious minorities? From the 1980s to the present, Japan has become home to a rising number of new religious groups from home and abroad that use religion to construct their identity (Mita 2011; Miki and Sukurai 2012; Miki 2017). Representative of this diversity is the Roman Catholic Church of Japan with multicultural congregations throughout the country (Takahashi et al. 2018). These communities are finding mushūkyō to not be the religious tabula rasa Japanese claim it be, but rather an identification used to suppress dialogue and religious dissent.

2. Discourse and Its Implications for Mushūkyō Identification

This chapter focuses on the collective identification of mushūkyō taught by teachers, classmates and team members. Children sense religion is abnormal and controversial through a school system that assumes their lack of religious participation. School authority figures imbue mushūkyō with properties that look strikingly similar to ‘discourse’ and its use of power as a form of control. This paper analyzes discourse to understand how society constructs the notion that ‘all Japanese are non-religious’ to aid in its perception of religious homogeneity.

The term “discourse” originates from the French social theorist Michel Foucault who understood social narratives as being produced and disseminated through the way we speak, read, and think. Foucault was concerned specifically with how power was wielded by those in authority to construct a common narrative that advanced their view of the world (Strenski 2015; Pitsoe and Letseka 2013). Discourse differs from religion in how its central idea centers not on individual ‘belief’ but on how people act in accordance with how they believe others believe. In other words, by adopting a “system of thought that reflects and constitutes everyday reality” discourse becomes a “dominant ideology” that unconsciously influences individuals’ actions (Burgess 2007). In Japan, some examples of discourse include those of nihonjinron and multiculturalism. Nihonjinron discourse holds that Japanese are superior to other cultures due to their ethnic and cultural homogeneity. Multicultural discourse argues the inverse through claims of Japanese ethnic and cultural diversity. Both ideologies over-simplify reality by prescribing notions of homogeneity or diversity to all Japanese and influencing public opinion by ramping up feelings for or against immigration. Discourses are not concerned with whether something is ‘true’ or ‘false’, only that a certain interpretation becomes “internalized, circulated, and utilized by the population” (Burgess 2007).

Mushūkyō identification borrows many properties from discourse for the way it impacts public opinion. Regardless of whether 60%, 70% or 80% of Japanese identify with mushūkyō, what matters is how their belief-in-the-belief of others creates a “dominant ideology” of all Japanese being mushūkyō. In other words, mushūkyō identification has become the unstated reality of a society that trivializes and problematizes religion and its equivalents (Mullins and Kisala 2001; Ishii 2010). Unfortunately, data collected in this study from the utterances or open discussion of mushūkyō by teachers and school officials is insufficient to argue that mushūkyō is a ‘discourse’ in the strictest sense. For this reason, I have chosen not to use discourse in my line of reasoning forthright, but instead, raise it here for how its connection to power and ideology influence our comprehensive analysis of mushūkyō identification. This is achieved by using popular literary works and internet sources to show how mushūkyō influences the desire of children to belong.

2.1. Mushūkyō and Its Derivatives in Popular Works

Yamamoto Shihei (pen name Isaiah Ben-Dasan) and his book The Japanese and the Jews helps pain the parameters of mushūkyō identification. Yamamoto coins the term “nihonism” to classify all Japanese under a single supra-religious ideology.

Though it sounds strange to Western ears, it is not at all unusual in Japan to hear young engaged couples discussing whether their wedding ceremony will be Shinto, Buddhist, or Christian. The nature of the rite makes no difference, since those concerned are members of the Japan faith I call Nihonism. (…) Though it is natural that the regulations governing the lives of believers differ from religion to religion and must coexist in countries like Israel and America, Japan is almost unique in that its people, sharing a faith that transcends all other religions, have no need of special bodies to pass on matters relating specifically to Shinto, Buddhism, or Christianity.(Ben-Dasan 1982, pp. 113–14)

Yamamoto’s nihonism never caught on in academic circles or in public use, but its idea that all Japanese are united under something supra-religious is frequently recycled by other authors. Some of these include Ama (2005) and Shimada (2009). Ama classifies the world’s religions into “natural” and “founder” religions, for which only Shinto finds its way into the former. Shimada, voices Japanese religious exceptionalism in his argument of mushūkyō as a unique style of Japanese religion. Still more, Katayama (2006) argues the existence in Japan of a pseudo-religious “framework” (waku) that renders the “crutch” of religion obsolete. Finally, Neruke considers Japanese religiosity to be something “natural” like the “air” one “inhales and exhales” (Neruke 2014, p. 22). In addition to popular authors are numerous armchair academics on social media such as the blogger at Nippon Talk who claims, “most of Japanese have no religion (…)” (Nippon Talk Blog 2019). The blogger for Japan Today states, “Japanese people are spiritual rather than religious”, using more western terminology to define their practice, while tiptoeing around notions of Japanese possessing a singular, non-religious identity (Japan Today 2013).

Characteristic of the religionist opinion, the Japanese Muslim “Kubusan” claims in an Aljazeera documentary how Japanese do not “have a strong sense of religion” and are “not interested in religion” (Aljazeera News 2018). Kubusan narrates how as a child he “was never told about the importance of religion”. Kubusan’s perception of Japanese having no interest in religion mirrors research by Kudō (2008) of Japanese Muslim women. Kudō’s Muslim interlocutors uncover a hidden assumption that Japanese believe themselves to be non-religious, and actions hinting otherwise (such as refusing to eat pork or wearing Islamic head coverings) are met with suspicion and caution (Kudō 2008). Writing at the turn of the century, Clammer (2001) also described how Japan’s mushūkyō atmosphere (though he did not call it this) isolates Japanese Christians, whom he calls “ideological minorities”. Clammer illustrates how Christians stick out in society for subscribing to beliefs and practices that originate from a “distinctively foreign origin, of radically different cosmology and ethics” than the prevalent Buddhist and Shinto traditions that rests at the bedrock of Japanese society (Clammer 2001, p. 164; also see Pye 2009).

These voices point to the unstated belief that Japanese consider themselves to be united in religious disbelief that differs from Western atheism or agnosticism, but functions similarly in the way it constructs an imagined reality most Japanese find easy to identify with (Kobayashi 2019). Support for this collective non-religiousness has found its way into the mouths of school officials as they restrict the actions of religionists.

2.2. Mushūkyō Played Out in the Public Schools

Japanese public schools have a long history of violating or bending the Japanese constitution’s clauses on the separation between church and state. Studies by Sugawara (1996) and Nakagawa (2001) show that carrying omikoshi portable Shinto Shrines, bowing in front of kamidana altars, or requiring school attendance on Sunday can (and often do) violate children’s religious free speech. Similarly, schools’ control of extra-curricular activities shapes children’s beliefs by inculcating a sport culture of civic religious proportions (LeMay 2018b; Bain-Selbo and Sapp 2016). As a university educator who trains junior and high school teachers, I often hear from graduates how club activity is out of control, demanding long hours from teachers and children alike. This system defines club as extracurricular, but with its mandatory participation functions as anything but.

The mushūkyō narrative permeates relationships children form at school, and becomes the principal tool schools use to discourage religious difference. Effects of mushūkyō surface when teachers, coaches and students avoid topics of religion, thus producing a religion-free environment that does not reflect the actual religious diversity outside the classroom.1 In her study of Brazilian children in Japanese public schools, Dias (2014) illustrates through four case studies how stigmatization works to assimilate children’s religious differences. Her studies included a girl who refused to cut her hair, a boy who refused to take off a religious necklace, a boy who refused to eat a haram (none-Islam) school lunch, and a boy chastised for using a religious hand sign misconstrued as something vulgar. In each example, Dias shows how teachers’ ‘appropriate’ responses to the religious acts of children were to remove them from the classroom and/or demand their silence. As a result, religion was suppressed and turned into something taboo, rather than dialogued with to achieve a mutually beneficial outcome.

Dias’s study reveals some of the trials foreign-born children face within public schools, but falls short of drawing connections between the religious assimilation of her informants and their absence at church. This study attempts to fill this gap by beginning where she left—connecting the dots between schools’ religio-cultural assimilation. Mushūkyō may not be a common topic at schools, but its control of the lives of children (and teachers) has had deep ramifications in teaching alternative values such as those taught at church or at home. This has become apparent in the flight of children from their parent’s religious communities to play sports. Through replacing the former with the latter, the state has become an actor in the production of its own religious homogeneity.

3. Methodology

This chapter is laid out in two phases. First, I observed children at Yamagoe Catholic Church during the period of 2010–2019 as its church school’s architect and youth leader. Yamagoe Church was chosen for its position in Tokyo, a metropolis with the highest percentage of foreign-born Catholics and Japanese parishioners throughout the country. Churches in Tokyo are comparatively ethnically diverse, offering a variety of social services to foreign-born parishioners, for which English Masses are the most usual.

Yamagoe Church School was created in 2009 by the author in collaboration with other leaders and college students. Its members predominately come from multicultural backgrounds, but have been raised in Japan and its schools, and thus speak Japanese fluently. These children were chosen for this research because their stories represent the transition from religionist to mushūkyō that occurs with the ‘help’ of the public education system. The quantitative data in the next section exemplifies how generations of religious minorities are systematically assimilated through expectations that they, as Japanese, should identify as mushūkyō. Their stories tell of religious cohorts who are pulled from church communities well before reaching adulthood, or in the case of many, even adolescence. Their religious absence exemplifies the consequences of accepting, with little opposition, a mushūkyō identity and its promises of group conformity.

The second phase of research began in 2018 to better understand how mushūkyō controls Yamagoe children. I began this through inquiry into Daiki’s childhood, a friend I met at church two decades prior. From his story, I was inspired to continue similar interviews with Ryūtarō, Rika and finally Hiroki. These interviews are told in story form to easily comprehend how mushūkyō affects children throughout their lives. While reading their stories, readers should focus on how school rules and peer pressure construct an environment that limits religious activities. Children find maintaining their Catholicism within this environment fundamentally different from the trials Catholics confront as adults. For this reason, the following study varies from the ‘ideological minorities’ Clammer (2001) discusses in his book on Japanese Others.

The four individuals focused on below differ in ethnicity, family demographics, and school. Their ages vary from 14 to 50, although the period in question centered on their adolescence and the conflict between school and church. The age difference of informants poses challenges, considering narrations tend to change over the life course. Conscious of this limitation, I include these four interviews to delineate how the conflict between club activities and religious identity formation has existed since at least the beginning of the 19th century (Cave 2004). Their life stories reveal how fanaticism associated with sports and club activities plays a key role in the ideological assimilation of children.

The following ethnographic data was collected from informants with their consent and knowledge of my position as a researcher. Semi-structured interviews were conducted from April 2018 to May 2019 at Yamagoe Church or public places such as coffee houses or restaurants, and observations were carried out over a longer period of nearly a decade of interaction with informants. Interviews were conducted in a mixture of Japanese and English lasting between thirty to ninety minutes and followed by inquiries via the social messaging system known as LINE. The author received approval for interviews from informants’ guardians (when necessary), and fellow youth group leaders. Finally, all proper names, including Yamagoe Church, are pseudonyms.

4. Club Activity and the Properties of Mushūkyō

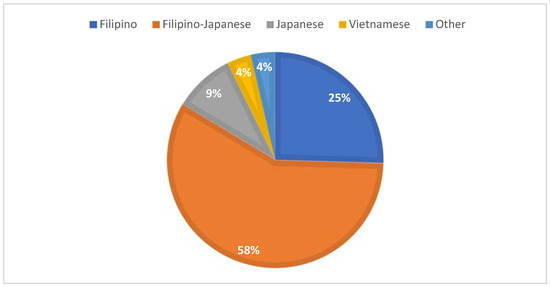

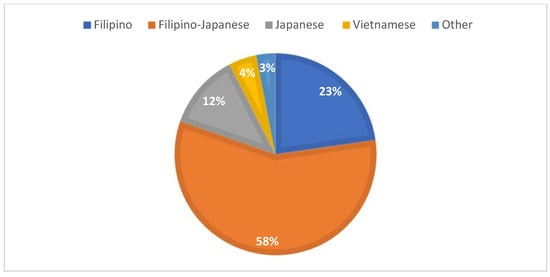

Mushūkyō is best recognized by the way it influences religious minority communities. This section uses data collected from the Yamagoe Church School (church school hereafter) to show how the culture of club activity impacts small religious communities. The following attendance was compiled from children attending catechism and church camps from ages six to eighteen. The ethnicity of children attending both events included Filipino, Japanese to Vietnamese, with most coming from Filipino-Japanese backgrounds (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Church school catechism class ethnic composition April 2017–June 2018 (n = 55).

Figure 2.

Biannual church camp ethnic composition September 2011–March 2019 (n = 66).

The large number of international children at this church school is more out of chance than design. In general, the current ethnic makeup of Catholic Churches in Japan is ethnically diverse with most parishioners being foreign-born (Terada 2010; Mullins 2011; Shirahase 2018). This is especially the case in churches that offer foreign language Masses like Yamagoe Church. Despite this diversity, Japanese, foreign and international children incur heavy assimilation into the public education system with most speaking Japanese as their strongest (if not only) language. In addition, the longer children spend within the Japanese education system, the greater their chances become to leave Yamagoe Church (and the Roman Catholic Church in Japan) (Muncada 2008; Okada 2014).

4.1. Ethnic Diversity of Yamagoe Church School

Yamagoe Church School is an ethnically diverse community heavily influenced by its Filipino community. Yamagoe Church’s ethnic diversity originates from its two Masses: A Japanese morning Mass and an English afternoon Mass. The former is attended by roughly 70 Japanese and the latter by 200 Filipinos. The church school holds catechism classes once a month after the Japanese Mass and during the English Mass. In addition to catechism class, the church school offers a biannual two-day camp held in winter and summer of each year. Ethnicity was recorded at these events and compiled in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Both figures consist of 58% Filipino-Japanese participants, with another 23–25% coming from Filipino-Filipino families. The remainder consists of Japanese-Japanese, Vietnamese, and ‘Others’ like Koreans.

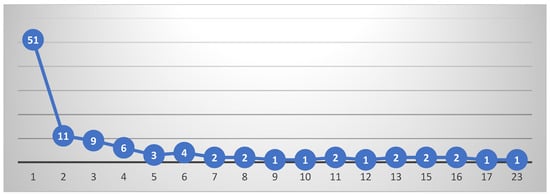

4.2. Absence from Church School

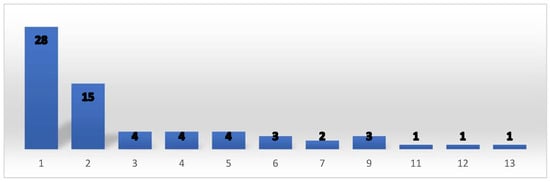

Despite the large number of children participating in classes and camps, much of their attendance is sporadic and short-lived with children attending for periods of months rather than years. I recorded this trend at monthly catechism classes. Over a period of twenty-six months from April 2017 to May 2019 one-hundred and three children attended the church school. Of these, fifty-one children, or 50% attended only once. Children attending three times or more were seventy-one children or nearly 70% of the total. The remaining thirty-one children accounted for 30% of the total, with many children being absent for periods of two or three months at a time (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of church school attendance April 2017 to December 2018 (n = 102).

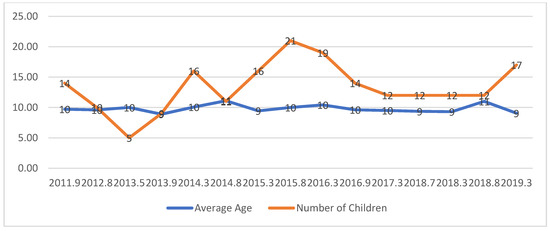

In comparison to monthly catechism classes, data was collected at fifteen biannual camps held in the winter and summertime from 2011 to 2019 (Figure 4). According to data, 66 elementary and junior high school students attended. The average age children started to attend was 9.3 years old (elementary school, grade 3), and the average age of their discontinuation was 11.2 years old (elementary school, grade 5). By comparison, the median age of children’s attendance was 10.3 years old (or elementary school, grade 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of attendance over 15 church camps (n = 66).

Data shows attendance at biannual church camps fluctuate around 10 to 15 children, of which most attend once or twice before leaving. Of the children who participate, 65% do so between one and two times, with the remaining 35% of children attending between 3 and 13 times (Figure 5). The average number of camps attended was 3.0 camps or roughly 16 months of attendance. Simply put, children do not consecutively attend church school with their overall attendance lasting between one and two years. The percentage of repeating children at the church camp is higher than at church school because the former requires more commitment, including two days of activities, a nominal fee, and preparation. Overall, even children who attended the catechism class monthly and the camp twice a year still had poor attendance leaving shortly after entrance into junior high school.

Figure 5.

Distribution of Church Camp Attendance (n = 66).

4.3. Discussing Club Activity and Church

Observations from Yamagoe Church School reveal that many children begin to attend after catechetical instruction for the sacrament of first communion. This class lasts five weeks from the month of May until June. Participants must be grade 2 in elementary school (age seven) to participate. Following the first communion, parents are solicited to send their children to church school. Most parents comply with this request enrolling their children in the middle of their second year. This usually continues for several years until club activities begin at elementary school in grade 4. As children age, their allegiance to school friends and activities outside of church increase, demanding more of their weekend time. This materializes first with their absence from church school, followed by their disappearance from church. When they reach junior high school (ages 12 or 13) few remain. This ‘silent exodus’ from the church of their parents is the result of a combination of factors including (amongst others): Pressure to participate in school clubs, and to identify as mushūkyō.

5. Ethnographic Interviews from Four Catholic Children

Why do so many Catholic children come to identify as mushūkyō? To answer this question this section looks at four life stories of Catholics from various backgrounds to paint a picture of the complexity of mushūkyō religious assimilation and its impact on children’s grade school lives. The following four narratives expose common themes in children’s suppression of their Catholicism, which are explained further in Section 6.

5.1. The Othering of Japanese Catholics

The first story comes from Daiki (42), a Japanese Catholic musician, husband and father of two. I first met Daiki more than twenty years ago at a 1997 Catholic youth event in Shiga prefecture where he played the lead guitar in a youth band. At that time, Daiki was 21 years old, and had for most of his childhood attended church in some form with his mother and his older and younger sisters. Despite being the ‘star’ at church, he hid his Catholicism in public.

From early childhood, Daiki understood that when he talked about Catholicism, it would elicit a negative response. “I learned early on that if I was to fit in, I had to avoid talking about church”, he admitted. Daiki had learned to keep his faith secret for the negative responses it attracted from his Japanese classmates. This was not something other Japanese told him explicitly, but more something he sensed from uncomfortable responses to discussions about church activity. It was this ‘othering’ that made Daiki conscious of his ideological difference as early as age seven. “One of my first memories about being Catholic was in elementary school. At that time, there was a church school event and upon asking other children if they would go, I realized I was the only one”. Finding that he would attend church alone taught Daiki about being different. Later, he came to understand Catholicism was perceived by his friends and teachers as something negative.

As Daiki got older his interactions with Japanese taught him that to fit in, he had to hide his Catholicism. Adolescence was a difficult period of development for Daiki, where he would learn the sting of Japanese isolation. This can be seen in the following two vignettes taken from his life in junior high school. The first experience came from his basketball coach whom he asked for permission to attend a church youth group event much like the one described above. To his alarm, the coach refused. “My coach mocked me saying, ‘Why do you have to go to such a place like that?’ I did not know what to say. I wondered why it was wrong I should attend a church event I had been active in since childhood”. Unlike previous experiences that reminded Daiki of how he differed from other Japanese, this experience taught him that Catholicism was not only different, but strange. From that point on, he believed he could not discuss his church activity with teachers whose job it was to facilitate his growth into adulthood. Daiki’s feeling of isolation increased throughout his time in junior high school one event at a time—first this came from his teachers, then from his classmates.

On a different occasion, Daiki had a confrontation in the locker room. The story begins with a holy medal he received from his mother he kept in his wallet. While changing for sports activity this fell to the ground and was discovered by another child. “I first felt something was wrong when I heard a kid question ‘what strange person would carry religious medals’? I overheard him ridiculing its owner and realized he was talking about me. I was petrified! I didn’t know what to say. I wanted to get my medal back, but I was afraid they would mock me.” Daiki was the only Christian in his class and felt exposing himself would cause troubles in the future. “[In the end] I said I knew someone who was Christian I could give it to.” Daiki’s quick thinking was sufficient to get his peers to hand over the medal without question, but also taught him a valuable lesson about how his beliefs were viewed by others.

5.2. Rika and the Yamagoe Church School

The next example comes from Rika (14), an adolescent girl currently experiencing identity troubles. Rika told me she was raised in Saitama prefecture by her Filipino single mother after her Japanese father committed suicide when she was an infant. When we first met in 2011, she was in second grade elementary school and attended church with her mother and older brother. Her first year of attendance at Yamagoe Church School was a bitter-sweet experience. “I wanted to play with my friends on Sundays, but my mother would deny my request yelling, ‘Sunday is for church’”. When she entered the church school with her brother, she was antisocial explaining how she did not want to associate with the same crowd as him. After two years passed, her older brother left church and she attended her first sleepover making friends with a Filipino-Japanese girl she could relate with. Her friendships with Filipino-Filipinos and Filipino-Japanese blossomed turning church into an environment different from the mono-cultural atmosphere of school.

In junior high school, Rika joined the brass band because her friends encouraged her to join. She plays the baritone saxophone. “I regret my choice” she complained, “I should have chosen basketball”. Her first complaint was the long hours she was forced to practice. “Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday” was the mantra she repeated. In the beginning, she tried her best to attend all these practices, but found them beyond her capacity. “As a first-year student (in junior high school) I can remember having to arrive at school at 5:30 am to attend an away competition. I did not get home until 10:30 pm. I was exhausted.” This invasive schedule complicated her church time on Sunday, leading to her repeated absence. She explained to me cavalierly that she could excuse herself from club whenever she felt like it, but it was this pressure to attend every day along with attending a homeroom where she had no friends that would eventually lead to her mental breakdown.

At the start of her second year, Rika was traumatized when she checked the school bulletin board to find her homeroom class. “When I initially looked for my homeroom, I passed my name because I knew no one there. I just assumed I would be placed with my friends. I reread the list several times before it hit me”. From that point forward anxiety rose every morning when she thought about attending school. First, she dropped out of the band, then she stopped attending school. She even attempted suicide by cutting her wrist. Her truancy continued for half a year leading to a physical confrontation with her mother that ended in her fleeing the house to stay with her older sister. Finally, she started going to school again in September 2018, but things never returned to the way they used to be. In class, she commented on students making fun of her behind her back, and her fellow band members criticized her for missing practice.

Rika is not a model student, yet throughout this entire ordeal, she never missed church. In fact, her attendance improved. When I asked why her attendance was so good, she told me “I like church” and “my church friends understand me better, and I don’t need to explain things like I have to when talking with people at school.” What she means is that her international friends at church understand what it is like having a Filipino mother and the difficulty of being bicultural. “I wish school was like church, at school, it seems I have no friends.” Rika attended church in place of school because she felt more accepted. Rika’s church friends understood her because she unabashedly told them who she was. This was unlike her friends at school. Before her school absence, Rika had tried everything to avoid being different, including hiding her ethnic and religious identities. For instance, she did not tell others her mother was Filipino and did not invite her school friends to church events. For all purposes, her church life was separate from her school life. However, this was the sacrifice she was forced to make, if she desired to be perceived as normal.

5.3. Mushūkyō, Baseball, and Ryūtarō

Ryūtarō (22) is a Kenyan-Japanese boy whose life story is the antithesis of Rika. For starters, Ryūtarō looks foreign. His ebony complexion reveals more of his absent father than the Japanese mother that raised him. A devout, Nagasaki Catholic, his mother divorced his father and moved to Tokyo while Ryūtarō was an infant. Despite his complexion, Ryūtarō acts more mushūkyō than any other of my informants, with deep connections to his junior high school and high school baseball team, and even annual trips to Shinto shrines.

I first met Ryūtarō while he studied for university entrance exams at a Tokyo-based, Jesuit-sponsored cram school. We talked in English about politics and odd topics. Religion was one of these. He told me he had not always been open to discuss religion and for most of his adolescence avoided religious conversation. “[While growing up], I didn’t want my friends to know my mother was Catholic because I didn’t want them to see me as different,” Ryūtarō confessed. Her difference unlike his complexion was something he could hide—and did.

Ryūtarō’s experience with church began with his baptism as an infant. From childhood, his mother would bring him to church on Sundays as she attended Japanese Mass. He attended church with his mother until completing the first communion class in second grade elementary school—something he remembers little. Looking back, Ryūtarō vaguely recalls attending Mass, receiving religious instruction from a Catholic nun, and partaking in communion. Ryūtarō found the elderly atmosphere of church “boring” with little to offer. He also had no friends there and hated sitting silently while listening to the Japanese homily. After receiving his first communion, Ryūtarō’s mother allowed him to play soccer in the park adjacent to the church while she attended Mass. “My mother knew where I was and there wasn’t any danger”, he reassured me.

Ryūtarō interpreted his flight from the Catholic Church as something natural, but his mother’s actions proved otherwise. She continued to passively influence him through purchasing church medallions and praying for his return. She also decorated their apartment with pictures of Jesus or Mother Theresa hoping this would inspire his return. When it came time for Ryūtarō’s entrance examinations into university, she suggested he study at the cram-school where we met, and later secretly met me at church to request my intervention into his faith. The latest development came when she convinced him to join the 2017 World Youth Day Catholic event held in Poland, and to study Spanish in the Dominican Republic and Mexico, all countries with heavy Catholic populations. Disappointing for her, these have had little effect on his relationship with church.

Perhaps Ryūtarō’s mother thought he would return to church when he became old enough to understand? Perhaps she believed it beneficial he spends time with children his age instead of an aging community he felt anxious attending? Whatever her feelings on the subject, Ryūtarō would never ‘return’ to his mother’s church because whether it be soccer or baseball, he chose to fill the Sunday time slot with sports. Within time, the few hours on Sunday he gave to soccer increased in junior high school where he would practice day and night. Ryūtarō explained to me the long hours of his junior high school baseball practice saying,

We would begin baseball practice before school from 7:00 to 8:30 am. After school, we would continue to play from 16:00 to 20:00 pm. On weekends, we would spend the entire day playing games from early morning to night. Even on New Year’s Day we would meet on the baseball ground at midnight to eat toshikoshi soba and start the first day of the year in practice.

There were few days Ryūtarō had free time to do anything outside of club activity, and even the New Year was not ‘open-season’ for baseball. If pressure by teammates to attend each practice was not enough to deter his absence, the physical punishment inflicted by his coach helped. “If someone were absent from a game or practice, the coach would “force them to run extra laps”, he told me. For this reason—and because “baseball was fun”—he became well-liked by his teammates.

Ryūtarō’s model record of baseball attendance directly affected the relationship with his mother and her church, because on weekends, when he had games, his mother had church. Reflecting on his feelings in high school, he admitted to blaming his mother and her Catholicism. “There was a time I hated her church and resented her for not attending my games. Other parents would attend, but mine was always missing”, Ryūtarō lamented. His mother’s absence on Sundays coincided with his baseball games, an important time he needed his mother to attend. Unlike his classmates, Ryūtarō’s foreign features necessitated his Japanese mother’s attendance to show others that he was Japanese. Nonetheless, church kept her away. The separate lives of Ryūtarō and his mother influenced their relationship in profound ways. “I barely saw her during those years”, he explained. When he returned home at night, she would have his dinner waiting for him in the fridge. He would also eat something quick in the morning on his way out the door. This separate life led him to summarize their relationship saying, “[I guess you could say that in the end] I found baseball more important [than church]”, and with this their relationship. By the time Ryūtarō reached high school, his baseball team had become a surrogate family that would (unofficially) take his mother’s place. He felt accepted, surrounded by them, but this acceptance was predicated on his ability to hide her religious activity.

5.4. Hiroshi, Mushūkyō and Youth Rebellion

The last informant is a 50-year old Japanese Catholic I call Hiroshi. We first met after a Respect for the Elder Day event Yamagoe Church held in 2018. His father, having fallen ill several times in the past year requested his assistance to attend the Japanese Mass. As a self-professed nominal Catholic, Hiroshi admitted to rarely attending Mass. This changed after his aging father requested his son to escort him to church on Sunday. Hiroshi was raised Catholic by his devout mother and father. He explained how there were obvious expressions of Catholicism around him while growing up, such as pictures of Mother Teresa or Jesus hanging on the walls of his house. Other things like having to make the sign of the cross as a sign of his honesty was an impressionable memory she left on him

Hiroshi’s first memories of school were at a Nagasaki kindergarten attached to a Catholic Church. “Growing up in a Catholic kindergarten made being Christian normal. I thought nothing of it”. Supposing he had stayed in Nagasaki, his life most certainly would have been different, but his father’s job did not allow this. Hiroshi’s father was a circuit judge and was required to move around Japan once every three years. This meant Hiroshi would attend four different elementary schools and two different junior high schools before finally ending up in a Tokyo-based, Catholic high school. “The first move I can remember was to Tochigi prefecture. There I felt like I had entered a different country. Not only was the dialect different than Nagasaki, but we lived next to a Buddhist temple and I was the only Christian in my elementary school”. Or at least he thought. The religious silence of his classmates compounded by the heavy presence of Buddhist symbols made him feel “like a foreigner”. Similar environments awaited him each time he moved, with none reflecting the Nagasaki kindergarten he was first exposed to.

“In junior high school, I stopped attending church because I became busy (with club and friends)”, he confessed. “While in elementary school children do things with their parents, but as they grow older, they become more independent”, Hiroshi said as he qualified his church absence explaining his activity in kendo2 took most of his time on Saturday and Sunday. “When I lived close to church it was easier to attend, but such was not the case after elementary school.” As a teenager, Hiroshi was physically bullied because his class was full of children with disciplinary issues. This taught him to fight back. “I learned early on that I would have to defend myself. Because I am not a large boy. So, I used my mouth to talk back to those I disagreed with.” Hiroshi complained about not being able to take things for granted like other children. “I often questioned why I did not understand things and felt stupid”. Some examples he gave were during Mochū, the Buddhist period of mourning after a family members’ death. “I didn’t know not to invite friends to play if their families were observing Mochū. Because I was raised Catholic, I was unaware of such customs.” This difference made Hiroshi stick out and led him to argue his opinion verbally.

Hiroshi’s parents associated his bad mouth with him not going to church. Their solution was to enroll him in a Catholic boarding school. “High school was different from other schools I had attended because there were more Christians and attending Mass and church events were accepted.” Hiroshi explained that many of his classmates had lived overseas or had struggled with being different. “They would speak freely like me. Of course, we would get into fights, but we would not assume each other’s opinion”. Hiroshi mentioned feeling more accepted in this Catholic environment because there were no assumptions placed on him that he should comply with the will of the group.

6. Catholics Maneuvering Mushūkyō Environment

The above stories of Catholics’ ‘othering’ at public school hint at a system that is not religiously neutral, but in fact, biased against congregational religions that require weekly attendance. Such is the case with Judeo-Christian religions that demand of its members’ weekly attendance. Unfortunately for Christians, the concept of a Sabbath is foreign to Japan (Kohara 2018). For this reason, schools are given surprising over-reach to control the lives of children. It is not uncommon, for example, for homeroom teachers to call guardians requesting children attend mock tests for entrance examination, or coaches call children’s homes for them to attend extracurricular practice or sports games. To add to these pressures, in many prefectures club activity is mandatory during first grade junior high school, leading to a severe reduction in parent-child time (LeMay 2014). Even when children opt out of club activity, a system of point allotment that benefits children who attend the club can increase chances to enter the high school and university of one’s desire. These advantages of club activity incentivize church absence, influencing even the most juvenile children to return to the club to garner points before graduation.

Japan is full of rules from the legal to the unstated. Some include acceptance to play in a park unsupervised, from grade two, or being able to ride a bike to school, at grade three. In some schools, children are encouraged to attend club activities as early as fourth grade. Ryūtarō’s mother took advantage of these rules by allowing her son to play in the park shortly after he received the first communion in second grade. His experience typifies a school system that rewards conformity and leaves little room to develop cultures other than those sanctioned by the public schools. The collective identification with mushūkyō creates public pressure for children to fall silent when confronted with religious alternatives. Silence is the means children use to avoid being ‘othered’ and blend into what they perceive to be a monolithic, mushūkyō environment.

This environment “encapsulates” children into mushūkyō groups they perceive as representative of the reality in Japan, thus producing the view that they alone practice the religious views they hold. This isolation says Setran and Kiesling (2013) “buffers” Catholic children from coreligionists by “cocoon[ing]” them from outside influence (pp. 75–76). In doing so, schools construct competing narratives of mushūkyō that challenge and displace Catholic primacy in these children’s lives. Isolating Catholic children from coreligionists is achieved through the creation of psychological and physical barriers that support mushūkyō identification.

6.1. Psychological Barriers and Isolation

Mushūkyō’s most pernicious element comes from the manner in which it convinces religious minorities that they are alone. Dias (2014) showed in Section 2 how teachers used their authority to manipulate the religious decisions of children through demanding their strict adherence to school rules. Fundamental adherence to school policy brings with it a perception that every child obeys these rules, and only the ‘religious’ child is the problem. In this environment, Dias showed how the Christian who asks for special preference to practice their religion was given a reprieve under the stipulation they “not tell anyone”. The message was clear—the religious child was the weak link in the chain, they were the stranger in the crowd.

Psychological isolation of religious minorities from each other is the tactic schools use (consciously or not) to create a perception of religious homogeneity. This method is adopted by club coaches and upperclassmen as well as through notions that children will drop everything for practice. This was at play behind the heated exchange Daiki had with his elementary school teacher upon asking to be excused for church. We can also infer such an expectation in the threats of Ryūtarō’s coach and his strict attendance policy that gave no exceptions for religious attendance or other Sunday activities. Making practices mandatory also constructs an impression that all children, regardless of their family background, hold no allegiance to groups outside the club team. This is one more psychological barrier that adds to Christian children’s perception that their religious activity is to blame for their isolation. They are the exception, they are abnormal, not the group. Psychological barriers to religious practice increase with time, as each new year children give in to public pressure and leave church. With every new absence, the assumption that ‘normal’ Japanese identify with no religion is reified.

In junior high school Daiki was convinced he was the only one who was Christian, both on his basketball team and at school. This assumption led to his Petrine denial of Catholicism in the locker room. He could not expect coreligionists to come to his aid. Thus, his solution was to concoct an imaginary Catholic friend he no doubt wished he had had. His exchange allows a rare glimpse into the quotidian confrontations Catholic children face with mushūkyō that wears away their resolve one uncomfortable interaction at a time. With club activity beginning before junior high school, it does not take long for children to replace church friends with school friends.

This was what Ryūtarō experienced shortly after receiving his first communion and given the green light to play in the park with his friends. He had turned eight and playing outside with friends while his mother prayed was a ‘natural’ development. The social gratification that rewarded sports activity made it more meaningful for him both as a child and as a young adult. It was this social acceptance that pushed Ryūtarō up the proverbial elevator through grade school toward the inevitable flight from his mother’s church. Now a senior at university, Ryūtarō is a bona fide Japanese, who now visits Shinto shrines on the New Year. Ryūtarō mentioned how this has become his “tradition” instead of the Catholic tradition of his mother and her Nagasaki parents.

6.2. Physical Barriers of Encapsulation and Catholicism

The second feature of encapsulation is physical as actual barriers of time and space conflict with the limited window of opportunity for religious attendance. This is compounded by the sparsity of Catholic churches throughout the country. The distance between church and school increases the further one leaves metropolises of Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka, or the heavily Catholic prefecture of Nagasaki. Moreover, if the Mass being attended is said in a non-Japanese language distance to be traveled increases still. To complicate matters, it is common for children to attend junior high school considerable distances from their homes. Given these two factors, if schools attended are in the opposite direction from church, two or three-hour commutes are not unheard of. Such physical distance makes it impossible to respect the commitments of church and school when conflicts occur.

The physical distance between church and school impedes children’s church activities, thus making it more difficult to make friends at church. Friendships are strained further into junior high school as moving to new schools exacerbates already weak social connections between. At Yamagoe Church, transition into junior high school is a difficult period of adjustment, as April of each new year brings new faces and the loss of old. The church school struggles with children’s irregular attendance, despite formidable odds, to forge the bonds necessary to see them through the mushūkyō gauntlet of grade school. Ironically, public schools understand that children need social time to forge new bonds between classmates, which they encourage by scheduling activities like sports days and field trips. Seldom do churches have such luxury. Instead, they are forced to constantly negotiate the little ‘free time’ children are given, which is threatened by club activities on Sunday.

Hiroki and Daiki commented on the toll physical barriers took on their church attendance, the former complaining, “When growing up, I never had any church friends at school because the church I went to was quite a distance from my home [and school]. I guess there was no one in my class who was Catholic, because there was no one I had met at church there.” Chiming in, Hiroki told me, “I didn’t know anyone at church from my school because it was too far away. During junior high school, I spent most of my time playing kendo. I don’t think I ever went to church”. The experience these middle-age Catholics faced while growing up has, if anything, gotten worse due to the Catholic Church’s lack of priests and structural downsizing.

6.3. Silence and Its Complacency of Mushūkyō

Analyzing the church behavior of the above four interlocutors has revealed a complimentary system of school rules and social pressure that influences mushūkyō identification. This has been particularly pernicious to the already fragile religious identity formation of children due to impressionability by teachers and club mates. Children comply with expectations through their silence, which helps feed mushūkyō identification that in turn returns to suppress their religious expression. Through this cycle, alternative religious voices are suppressed creating a public image of Japanese ideological homogeneity. Daiki’s locker room episode exemplifies this in how through not identifying himself as Catholic, his classmates assumed he was mushūkyō. His religious silence produced the desired result—acceptance by his classmates. Silence was often the preferred response of children I interviewed when confronted with religion. They never talked about church at school and for the most part, had learned to separate the two completely. They understood there was no escaping the mushūkyō air that permeated school, and if they desired to have a life there, it would require they breath it like everyone else.

7. Conclusion: Public Schools and the Production of Non-Religion

[T]he effort to force secular and political movements of our time to be “religious” so that we can feel justified in clinging to our religion is, in the end, a losing battle. Secularization rolls on, and if we are to understand and communicate with our present age, we must learn to love it in its unremitting secularity”.(Cox 1967, p. 3)

This paper has analyzed how mushūkyō affects the life decisions of Japan’s Catholic minority creating a perception that all Japanese are non-religious. From then, quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed to show how mushūkyō encapsulates children psychologically by constructing a perception that it is natural to be non-religion, which in turn obstructs them physically by controlling their ability to attend church. The goal of my argument was never to argue against the club system in its entirety or that Catholics be given special privileges. Ultimately, this is not an exclusively Catholic problem. The current educational system with its control of the time and life decisions of children is suffocating alternative and dissenting views. Instead of encouraging inquiry and dialogue with other values and ideas, schools have become jealous institutions that exert power on children’s lives ultimately producing an ideological homogeneity in mushūkyō. Such a system does not free children from religious belief or some secular alternative, but instead produces a non-religious homogeneity that stifles free thought.

The quote by Harvey Cox above rightfully advises religious groups to reinterpret themselves and become more compatible with secular society, and churches must do this through framing themselves within a secular environment. Nevertheless, Cox’s words, while insightful, fail to capture the complexities of Japan’s modern age and how the non-religious stance of its secular institutions is used to justify suppression of alternative views. Religious discussion is avoided in the classroom and suppressed on the playground. Through a combination of time control, public pressure, and ideological rebranding (as mushūkyō), the Japanese schools have developed a recipe for assimilating Japanese. This has had far-reaching consequences on religious minorities and their ability to pass their values and customs down to their next of kin.

As Japan enters a new age of immigration marked by a 2018 immigration law that grants long-term and permanent citizenship to foreign nationals, it may not have to “force secular and political movements of our time to be ‘religious’”. Instead, what it really needs is to find a new path forward that encourages dialogue with its religious minorities. As religious views become more diverse, it is becoming less viable to use school institutions to create mushūkyō identity. If it desires a society where free thought flourishes, the future will require it to dialogue more with its minority groups. This includes the Catholic Church showcased here. A logical first step to achieve this would be to acknowledge the religious homogeneity it finds in mushūkyō identification as more the result of its public education, than the free will of its citizens.

Author Contributions

The author is a member of Yamagoe Church and a youth leader at its Church School.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no interests of conflicts.

References

- Ama, Toshimaro. 2005. Why Are the Japanese Non-Religious: Japanese Spirituality: Being Non-Religious in a Religious Culture. Lanham: University Press of America. [Google Scholar]

- Aljazeera News. 2018. Islam in the Land of the Rising Sun: The Road to Hajj. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oKe0SV8N7b4 (accessed on 9 June 2019).

- Bain-Selbo, Eric, and D. Gregory Sapp. 2016. Understanding Sport as a Religious Phenomenon: An Introduction. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dasan, Isaiah. 1982. The Japanese and the Jews, 2nd ed. Boston: Weatherhill. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, Chris. 2007. Multicultural Japan? Discourse and the ‘Myth’ of Homogeneity. The Asia-Pacific Journal. 5/3. pp. 1–25. Available online: https://apjjf.org/-Chris Burgess/2389/article.html (accessed on 30 June 2019).

- Cave, Peter. 2004. ‘Bukatsudō’: The Educational Role of Japanese School Clubs. The Journal of Japanese Studies 30: 383–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clammer, John. 2001. Japan and Its Others: Globalization, Difference and the Critique of Modernity. Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Harvey. 1967. The Secular City: Secularization and Urbanization in Theological Perspective. New York: MacMillan Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, Nilta. 2014. Diversity and Education: Brazilian Children and Religious Practices in Everyday Life at Japanese Public Schools. In Transnational Faiths: Latin-American Immigrants and Their Religions in Japan. Edited by Hugo Côrdova Quero and Rafael Shoji. New York: Routledge Press, pp. 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hardacre, Helen. 2017. Shinto: A History. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Iwai, Hiroshi. 2004. Notes on the Understanding of Japanese Religion. Kansai Kokusai Kenkyu Kiyo 5: 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Today. 2013. How Religious Are Japanese People. Available online: https://japantoday.com/category/features/opinions/how-religious-are-japanese-people (accessed on 19 June 2019).

- Ishii, Kenji, ed. 2010. Baraeteika Suru Shūkyō. Tokyo: Seikyūsha. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson, Jason Ãnanda. 2012. The Invention of Religion in Japan. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Katayama, Fumihiko. 2006. Nihonjin wa Naze Mushūkyō de Irareru no ka? Tokyo: Harashobō. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, Rikō. 2019. Nihonjin no Shūkyōteki Ishiki ya Kōdō wa dō Kawatta ka: ISSP Kokusai Hikaku Chōsa [shūkyō]—Nihon no Kekka Kara, Hōsoku Bunka Kenkyūjo. Available online: https://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/research/yoron/20190401_7.html (accessed on 9 June 2019).

- Kohara, Katsuhiro. 2018. Shūkyō Nyūmon: Sekai wo Yomitoku. Tokyo: Nihon Jitsugyō Shuppansha. [Google Scholar]

- Kudō, Masako, ed. 2008. Ekkyō no Jinruigaku—Zainichi Pakisutan Musurimu Imin no Tsumatachi. Tokyo: Tokyo Daigaku Shuppankai. [Google Scholar]

- LeMay, Alec. 2018a. The Position of Mushūkyō Practice in Religious Dialogue. Gengo to Bunka: Bunkyo University Bulletin, vol. 30, pp. 179–218. [Google Scholar]

- LeMay, Alec. 2018b. No Time for Church: School, Family and Filipino-Japanese Acculturation. Social Science Japan Journal 21/1: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMay, Alec. 2014. Bukatsudo and the Sport of Religious Assimilation. The Japan Mission Journal 68: 196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Miki, Hizuru, ed. 2017. Ikyō no Nyu-Kama-Tachi: Nihon ni Okeru Imin to Shūkyō. Tokyo: Shinwasha. [Google Scholar]

- Miki, Hizuru, and Sakuragi Yoshihide, eds. 2012. Nihon ni Ikiru Imintachi no Shūkyō Seikatsu: Nyu-kama- no Motarasu Shūkyō Tagenka. Tokyo: Minerva. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Meredith B. 2008. Lived Religion: Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mita, Chiyoko, ed. 2011. What It Means to Live in an Age of Globalization: The Transnational Lives of Japanese Brazilians in Japan. Tokyo: Sophia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Molle, Andrea. 2011. Spiritual Life in Modern Japan: Understanding Religion in Everyday Life. In Religion, Spirituality and Everyday Practice. Edited by Guiseppe Giordan and William H. Swatos Jr. London: Springer, pp. 131–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, Mark R. 2011. Between Inculturation and Globalization: The Situation of Catholicism in Contemporary Japanese Society. In Xavier’s Legacies: Catholicism in Modern Japanese Culture. Edited by Kevin M. Doak. Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 169–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, Mark R., and Robert Kisala, eds. 2001. Religion and Social Crisis in Japan: Understanding Japanese Society through the Aum Affair. London: Palgrave MacMillian. [Google Scholar]

- Muncada, Felipe L. 2008. Japan and Philippines: Migration Turning Points. In Faith on the Move: Toward a Theology of Migration in Asia. Edited by Fabio Baggio and Agnes M. Brazal. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manilla University Press, pp. 20–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, Akira. 2001. Shūkyō to Kodomotach o Kangaeru Shiten. In Shūkyō to Kodomotachi. Edited by Akira Nakamura. Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, pp. 11–58. [Google Scholar]

- Neruke, Muho. 2014. Nihonjin ni ‘Shūkyō’ wa Iranai. Tokyo: Besuto Shinsho. [Google Scholar]

- Nippon Talk Blog. Japanese and Religion-Nihonjin to Shukyo. Available online: http://www.nippontalk.com/en/japanese-and-religion/ (accessed on 9 June 2019).

- Okada, Peter Takeo. 2014. Response to the Secretariat of the Extraordinary Synod. Catholic Bishop’s Conference of Japan. Available online: https://www.cbcj.catholic.jp/2014/03/11/3357/ (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Pitsoe, Victor, and Moeketsu Letseka. 2013. Foucault’s Discourse and Power: Implications for Instructionalist Classroom Management. Open Journal of Philosophy 3: 23–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, Michael. 2009. Genzai no Nihon ni Okeru Shimin Shūkyō. In Yureugoku Shi to Sei: Shūkyō to Gorisei no Hazamade. Edited by Jean Baubérot and Ken Kadowaki. Tokyo: Koyo Shoten, pp. 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- Reader, Ian, and Joji George Tanabe. 1998. Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Setran, David P., and Chris A. Kiesling. 2013. Spiritual Formation in Emerging Adulthood: A Practical Theology for College and Young Adult Ministry. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Shirahase, Tatsuya. 2018. Katoriku ni okeru Jyusōteki na Imin Shien. In Gendai Nihon no Shūkyō to Tabunka Kyosei: Imin to Chiiki Shakai no Kankeisei wo Saguru. Edited by Takahashi Norihito, Shirahase Tatsuya and Hoshino Sou. Tokyo: Meiseki Shoten, pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, Hiromi. 2009. Mushūkyō Koso Nihonjin no Shūkyō de aru. Tokyo: Kadokawa. [Google Scholar]

- Strenski, Ivan. 2015. Understanding Theories of Religion: An Introduction, 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara, Nobuo. 1996. Gakko kyōiku de shūkyō ha dō atsukawareteiru ka. In Shūkyō to Kodomotachi. Edited by Akira Nakagawa. Tokyo: Meiseki Shoten, pp. 175–87. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Norihito, Shirahase Tatsuya, and Hoshino So, eds. 2018. Gendai Nihon no Shūkyō to Tabunka Kyōsei: Imin to Chiiki Shakai no Kankeisei wo Saguru. Tokyo: Akaishi Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, Tadaatsu. 2008. Attitudes of Japanese Students toward Religion from 1992–2001: Findings in Relation to “Family Religion” and Religious Education at High School. Bulletin of Tenshi College 8: 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Terada, Takefumi. 2010. Oversea Migrants and Religious Praxis: From the Perspective of the Filipino Community in the Tokyo Archdiocese. In Religions Under Globalization: Decline, Renaissance and Transformation. Edited by Masatoshi Kisaichi, Takefumi Terada and Masayuki Akahori. Tokyo: Sophia University Press, pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, Phil, Luke W. Galen, and Frank L. Pasquale. 2016. The Nonreligious: Understanding Secular People and Societies. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Japanese society is awash with popular and institutional religious acts too often labeled mushūkyō. |

| 2 | Kendo is a Japanese sport based on sword fighting with bamboo sticks. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).