Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment for Young Children1

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the factors of a Christian character scale for young children?

- What is the validity of the Christian character scale for young children?

- What is the reliability of the Christian character scale for young children?

2. Methods

2.1. Research Subjects

2.2. Research Procedure

2.2.1. Factor Development

2.2.2. Item Development and Content Validity

2.2.3. Pilot Study

3. Results

3.1. Data Screening

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

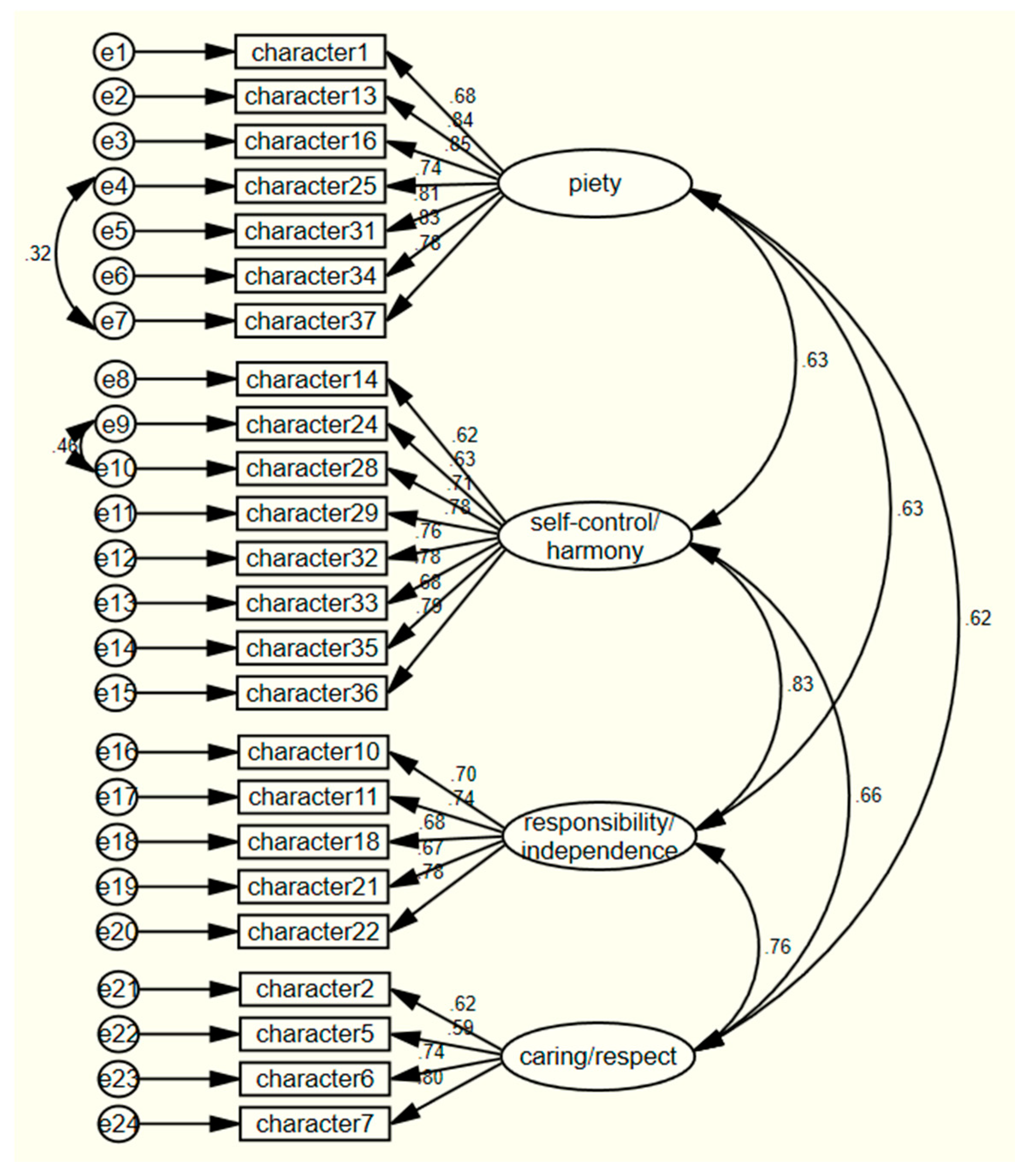

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3.1. Model Fit

3.3.2. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bae, Byung Ryul. 2017. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos 24: Principles and Practice. Seoul: Cheong Ram, ISBN 78-8-9597-2633-2. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, Sun Mi, and Sun Ah Lim. 2015. The development and validation of a preschooler character scale rated by teacher. Korean Journal of Educational Research 53: 347–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Timothy A. 2015. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press, ISBN 978-1-4625-1536-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, Geum-an, and Ok-hee Na. 2016. A study on the effect of children’s servant leadership and teacher-child interaction on children’s personality development. Journal of Future Early Childhood Education 23: 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Chul-Ho. 2016a. Structural Equation Modeling Using SPSS/AMOS. Seoul: Cheong Ram, ISBN 978-89-5972-458-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, In-young. 2016b. The effects that care education based on picture books with the six thinking hats skill has on young children’s caring thinking. Korean Journal of Early Childhood Education 18: 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Min Soo, and Eun Young Lim. 2013. The character education contents and method of young children to improve NURI Curriculum for three to five year olds. Journal of Future Early Childhood Education 20: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Minsoo, and Nam Yousun. 2015. The effect of physical activities in traditional plays on happiness and cultivation of young children. Journal of Eco Early Childhood Education 14: 242–60. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Andy. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. London: Sage, ISBN 978-1-84787-906-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, David W. 2000. Becoming Good: Building Moral Character. Downs Grove: IVP Books, ISBN 978-0-8308-2272-0. [Google Scholar]

- Henson, Robin K., and J. Kyle Roberts. 2006. Use of exploratory factor analysis in published research: Common errors and some comment on improved practice. Educational and Psychological Measurement 66: 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahng, Kyung Eun, and Seung Hee Song. 2016. Relationship-based character education for young children. Journal of Early Childhood Education & Educare Welfare 20: 157–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jeoung, Hee Young, Jung Ku Lee, and Min Joa Han. 2013. Extraction of the virtues for Christian early childhood character education. A Journal of Christian Education in Korea 36: 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeoung, Hee Young, Young Hae Choi, Hee Jung Jeoung, Seung Mi Bang, Jung Ku Lee, and Hee Jin Yu. 2014. The Theory and Practice of Christian Character Education for Young Children. Seoul: DCY Books, ISBN 978-89-6804-011-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Young Hee. 2012. Character Education Program in Conjunction with the Church and Home: With Gong Do Church as a Center. Ph.D. Dissertation, Presbyterian College and Theological Seminary, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Kyungeun. 2013. The spirituality of reconciliation for reconciliation ministry. Theology and Praxis 36: 447–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Ji Na. 2014. The General Trends and Relationship between Children’s Character and Parents’ Perceptions on Parent-Child Relationship. Master’s Thesis, Ewha Womans University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sung-Won. 2016. The evaluation of Christian character education curricula for young children. Christian Education & Information Technology 48: 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Sung-Won, and Hyun-Jung Shin. 2018. Development of a family-involved Christian character program using Bible stories for young children. Journal of Christian Education & Information Technology 58: 165–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jung won, So Rin Choi, and Eun Sil Choi. 2015. The development and practical application of a character education program using Leo Lionni picture books for young children. Journal of Early Childhood Education & Educare Welfare 19: 90–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Young Sook. 2012. Education Theory of Korean 12 Character Virtue by Dr. Lee, Young Sook. Seoul: Good Tree Character School, ISBN 978-89-6866-802-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jong-Hwan. 2017. Understanding and Application of Survey Methods and Statistical Analysis Using SPSS. Go-yang, Kyoung-Gi: Knowledge Community, ISBN 978-89-6352-676-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Jung-Ran, Hyo-Jin Jung, and Ji-Hi Bae. 2019. Early childhood teachers’ experiences of and suggestions for enhancing children’s caring behaviors. Journal for Early Childhood Teacher Education 23: 79–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. 2011. Nuri Curriculum. Notification No. 2011-30 of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. Seoul: Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. 2012. Nuri Curriculum for 3–5 Years Olds: A Guidebook. Seoul: Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Na, Eun Suk, and Kyoung Hoe Kim. 2014. A developmental study of the humanity rating scale for young children aged 3–5. Journal of Children’s Literature and Education 15: 433–52. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Sae-Nee. 2016. A Study on the Development of Character Education Program for Young Children Based on Caring. Ph.D. Dissertation, Duksung Women’s University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Hyun-Suk. 2012. A Study of the Effect of the Application of Alta Vista Curriculum to the Program on Children’s Character. Master’s Thesis, Chongshin University, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Woo-Sik. 2016. The implications of foreign SEL programs for the Korean character education policy: Based on cases of US, UK, & Singapore. Educational Research 31: 29–56. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Jung Eun. 2019. The Effect of Caring Education Activities using Picture Books on Caring Behaviors, Self-esteem, and Linguistic Expressions ability of Young Children. Ph.D. Dissertation, Wonkwang University, Iksan, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Patten, Mildred L. 2001. Questionnaire Research: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Pyrezak Publishing, ISBN 978-18-8458-532-6. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, Joo-Ha. 2010. A foundation Research on Reading Program for Biblical Character Education. Master’s Thesis, Chongshin Univerrsity, Seoul, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Hyunjung, Younchul Choi, Kyungchul Kim, Hyunju Choi, and Bookyung Cho. 2017. The development of creativity-character rating scale for 5-year-old children. Journal for Children’s Media 16: 133–56. [Google Scholar]

- Serafini, Gianluca, Caterina Muzio, Giulia Piccinini, Eirini Flouri, Gabriella Ferrigno, Maurizio Pompili, Paolo Girardi, and Mario Amore. 2015. Life adversities and suicidal behavior in young individuals: A systematic review. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 24: 1423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, James K. A. 2016. You Are What You Love. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, ISBN 978-15-8743-380-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, Soo-min, and Hee-hwan Kim. 2016. Impact of fathers’ recognition and participation of character education on character traits of young children. Journal of Future Early Childhood Education 23: 367–88. [Google Scholar]

- Stronks, Julia K., and Glora Goris Stronks. 2008. Christian Teachers in Public School. Translated by Hekyung Kim. Seoul: DCTY (Dream Comes True for You) Books, ISBN 978-89-9210-764-8. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, John, and Susan Yates. 1992. Character Matters: Raising Kids with Values that Last. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, ISBN 978-0-8010-6410-4. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Jong-Pil. 2012. Concepts and Understanding of Structural Equation Model. Seoul: Hannarae, ISBN 978-89-5566-124-8. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A5A8022121). |

| Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2011) | order, respect elders and honor parents, caring, respect, cooperation, conflict resolution | |

| Choi and Lim (2013) | basic living habits | courtesy, orderliness, cleanliness, dietary habits, well organized |

| social emotion | self-concept, stability, self-control, respect, cooperation, attentive listener, conciliatory, caring, kindness, affection, trustworthiness, communication, gratefulness, generosity, community spirit | |

| ethics and morality | public orderliness, diligence, courage, positive contribution (positivity), honesty, love, responsibility, trust, patience, devotion to parents, fairness, obedience, harmony, respect for other cultures, respect for traditional ethics, respect for life, patriotism | |

| Kim (2014) | trust, respect, responsibility, fairness, caring, civic spirit | |

| Na and Kim (2014) | interpersonal values | sharing, caring, courtesy, patience, respect, orderliness, responsibility, cooperation, honesty |

| individual values | identity formation, positive attitude, persistence, self-discipline, diligence | |

| social values | world citizen spirit, community service, commitment as a member of society | |

| Baek and Lim (2015) | sharing, caring, courtesy, patience, respect, order, responsibility, cooperation, honesty | |

| Seo et al. (2017) | interested in problem solving, finding alternatives, initiating action | |

| Lee (2012) * | empathy | attentive listening, positive attitude, happiness, caring, gratefulness, obedience |

| conscience | patience, responsibility, self-control, creativity, honesty, wisdom | |

| Jeoung et al. (2014) * | piety (holiness), love (compassion and mercy), self-control, patience, caring (gentleness, attentive listening, kindness), cooperation, peace (harmony), responsibility (loyalty, trust), honesty (sincerity, truthfulness), benevolence (goodness, generosity), joy, respect | |

| Developer | National Law Curriculum | Christian Character Program | Christian Character Constucts | Character Scale | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtues | Nuri Curriculum (2012) | Character Education Promotion Act (2015) | Bitu–Baro Character School | Saemmul Kindergarten | Good Tree Character School | Jeoung et al. (2013) | Baek and Lim (2015) | |

| gratitude | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| humility | ● | |||||||

| piety | ● | |||||||

| attentive listening | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| honor | ● | |||||||

| positive attitude | ● | |||||||

| joy | ● | ● | ||||||

| sharing | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| caring | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| love | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| communication | ● | |||||||

| obedience | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| goodness | ● | |||||||

| courtesy | ● | ● | ||||||

| courage | ● | |||||||

| forgiveness | ● | ● | ||||||

| patience | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| mercy | ||||||||

| honesty | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| self-control | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| prudence | ● | ● | ||||||

| respect | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| wisdom | ● | |||||||

| honest | ● | |||||||

| orderliness | ● | ● | ||||||

| responsibility | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| creativity | ● | |||||||

| peace | ● | |||||||

| cooperation | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| honoring parents | ● | |||||||

| Items (A Child) | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Communality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Piety | |||||

| 37. is happy to be attending church | 0.820 | 0.162 | 0.102 | 0.136 | 0.727 |

| 13. knows that Jesus loves him/her | 0.816 | 0.213 | 0.246 | −0.015 | 0.773 |

| 25. expresses thoughts about church and faith | 0.803 | 0.107 | 0.032 | 0.208 | 0.700 |

| 16. tries to listen and obey God’s words | 0.759 | 0.228 | 0.256 | 0.194 | 0.731 |

| 31. is satisfied and grateful for resources given by God | 0.757 | 0.280 | 0.102 | 0.188 | 0.698 |

| 34. treasures what God has created and cares for it | 0.744 | 0.379 | 0.139 | 0.127 | 0.732 |

| 1. likes God’s words, praise, prayer, and worship | 0.642 | 0.056 | 0.339 | 0.184 | 0.563 |

| Factor 2: Self-control/Harmony | |||||

| 36. can wait even if his/her needs are not immediately met | 0.216 | 0.799 | 0.203 | 0.130 | 0.742 |

| 28. throws a tantrum in order to achieve a difficult request to be accepted | 0.129 | 0.742 | 0.308 | 0.123 | 0.677 |

| 29. is conciliatory | 0.219 | 0.687 | 0.214 | 0.346 | 0.685 |

| 32. adjusts to and cooperates with his/her friends well in order to accomplish a collective task | 0.302 | 0.678 | 0.187 | 0.253 | 0.650 |

| 35. maintains values, convictions, and good behavior regardless of changing circumstances | 0.239 | 0.678 | 0.171 | 0.070 | 0.551 |

| 33. knows how to take turns and wait for his/her turn | 0.190 | 0.658 | 0.383 | 0.148 | 0.638 |

| 24. does not complain or have a temper tantrum when he/she is unable to get what he/she wants | 0.102 | 0.636 | 0.338 | 0.078 | 0.536 |

| 14. forgives his/her friends’ faults | 0.300 | 0.415 | 0.324 | 0.179 | 0.400 |

| Factor 3: Responsibility/Independence | |||||

| 21. keeps track of time (play, meals, arrival times) | 0.158 | 0.247 | 0.769 | 0.115 | 0.691 |

| 11. selects what is right and good | 0.230 | 0.329 | 0.684 | 0.095 | 0.638 |

| 10. completes a task given to him/her | 0.138 | 0.349 | 0.674 | 0.151 | 0.618 |

| 22. admits his/her faults and takes responsibility | 0.206 | 0.346 | 0.631 | 0.230 | 0.613 |

| 18. uses refined and honorific language to adults | 0.175 | 0.272 | 0.630 | 0.278 | 0.579 |

| Factor 4: Caring/Respect | |||||

| 6. says hello to adults first with a courteous manner | 0.149 | 0.099 | 0.341 | 0.721 | 0.668 |

| 7. expresses his/her gratefulness to a person who provides assistance | 0.283 | 0.023 | 0.400 | 0.686 | 0.712 |

| 5. gets along well with special needs individuals (foreigner, disabled, lonely child) | 0.099 | 0.359 | 0.005 | 0.656 | 0.569 |

| 2. reacts to other’s difficulties sensitively and helps out | 0.281 | 0.285 | 0.102 | 0.543 | 0.466 |

| % of Variance | 20.23 | 19.40 | 14.54 | 9.82 | |

| Eigenvalues | 10.50 | 2.34 | 1.40 | 1.12 |

| χ2 | df | SRMR | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||||

| 39 items | 2279.50 | 681 | 0.062 | 0.843 | 0.830 | 0.073 | 0.080 |

| 26 items | 825.82 | 289 | 0.048 | 0.914 | 0.903 | 0.062 | 0.073 |

| 24 items | 596.41 | 244 | 0.046 | 0.938 | 0.930 | 0.054 | 0.066 |

| Cutoffs | ≤0.08 | ≥0.90 | ≥0.90 | ≤0.06 | |||

| Construct | Item | Standardized Regression Weight | t-Value (CR) | CR (Construct Reliability) | AVE (Averaged Variance Extracted) | Cronbach’ α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piety | 1 | 0.683 | 14.366 | 0.945 | 0.712 | 0.919 |

| 13 | 0.836 | 18.391 | ||||

| 16 | 0.851 | 18.811 | ||||

| 25 | 0.738 | 19.158 | ||||

| 31 | 0.811 | 17.687 | ||||

| 34 | 0.831 | 18.246 | ||||

| 37 | 0.780 | Fix | ||||

| Self-control/Harmony | 14 | 0.618 | 12.744 | 0.936 | 0.650 | 0.896 |

| 24 | 0.627 | 12.948 | ||||

| 28 | 0.707 | 14.934 | ||||

| 29 | 0.778 | 16.804 | ||||

| 32 | 0.762 | 16.367 | ||||

| 33 | 0.780 | 16.866 | ||||

| 35 | 0.681 | 14.275 | ||||

| 36 | 0.789 | Fix | ||||

| Responsibility/Independence | 10 | 0.700 | 14.240 | 0.906 | 0.659 | 0.837 |

| 11 | 0.739 | 15.161 | ||||

| 18 | 0.679 | 13.754 | ||||

| 21 | 0.674 | 13.642 | ||||

| 22 | 0.781 | Fix | ||||

| Caring/Respect | 2 | 0.620 | 11.967 | 0.862 | 0.614 | 0.779 |

| 5 | 0.593 | 11.399 | ||||

| 6 | 0.735 | 14.285 | ||||

| 7 | 0.801 | Fix | ||||

| Model fit χ2(244) = 596.409, p = 0.000; SRMR = 0.046, CFI = 0.938; TLI = 0.930; RMSEA = 0.060 (low 0.054, high 0.066) | ||||||

| Factors | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | [0.712] | 3.87 | 0.67 | |||

| Factor 2 | 0.634 ** | [0.650] | 3.89 | 0.58 | ||

| Factor 3 | 0.537 ** | 0.723 ** | [0.659] | 4.03 | 0.57 | |

| Factor 4 | 0.532 ** | 0.581 ** | 0.622 ** | [0.614] | 3.89 | 0.59 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S. Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment for Young Children1. Religions 2019, 10, 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050318

Kim S. Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment for Young Children1. Religions. 2019; 10(5):318. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050318

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sungwon. 2019. "Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment for Young Children1" Religions 10, no. 5: 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050318

APA StyleKim, S. (2019). Development and Validation of a Scale for Christian Character Assessment for Young Children1. Religions, 10(5), 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10050318