1. Introduction

Michelangelo’s contemporaries unanimously described his Vatican

Pietà (

Figure 1), carved between 1498 and 1500, as the work that ensured the fame of the young artist and thus paved the way for his subsequent career (

Vasari [1550] 1962); (

Condivi [1553] 2009). More problematic was the devotional value of the work, as demonstrated by Pietro Aretino’s criticism (

Aretino 1957), and also the opinion of another author on the copy displayed in the church of Santo Spirito in Florence in 1549. The author of the Florentine Chronicle, also titled

Diario del 1536 di Marucelli, regarded Michelangelo as ‘the inventor of filth, saving the art but not the devotion’ (

De Tolnay 1948)—

inventor delle porcherie, salvandogli larte ma non devotione (

Cronaca fiorentina 2000). Nonetheless, this view, noted by scholars as early as the nineteenth century (

Gaye 1839) and often quoted since then, must have been rather isolated. Displayed in various altars of the old and then the new Vatican Basilica through the centuries, Michelangelo’s

Pietà was not only described as a masterpiece, but also—despite criticism—venerated as a holy image, a status that was officially confirmed by its coronation by the Chapter of St. Peter’s in 1637 (

Jurkowlaniec 2015).

In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, several of Michelangelo’s works provoked various responses as masterpieces or as religious images. The

Pietà drawing for Vittoria Colonna (Boston, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum) was not only a typical artist’s gift, a token of his skills, but also a devotional image strictly related to Michelangelo’s and Vittoria’s considerations of the question of divine grace, as can be inferred from the preserved correspondence (

Nagel 2000); (

Roman D’Elia 2006). In turn, the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel was perceived as a fresco that shows the power of art, but it was also vehemently criticised by Aretino, among others, as an indecent painting, which was particularly inappropriate in the pope’s chapel (

De Maio [1974] 1990); (

Barnes 1998). The marble statue of Risen Christ in Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome was praised for its excellence, but it was also reportedly mutilated by Dominican friars who, scandalized by the figure’s nudity, were said to have broken off Christ’s penis (

Ligorio 1549) cf. (

Celio 1638). However, in the early modern period the Minerva Christ, provided with a loincloth and displayed within a tabernacle, was venerated by the faithful. Since it must have been a widespread custom to kiss Christ’s feet, the General of the Dominicans, Antonino Cloche, commissioned metal sandals in 1706, to protect the marble from destruction (

Panofsky 1991); (

Schwedes 1998). As the devotional practices continued, one of the sandals was hardly preserved in the early nineteenth century (

Stendhal 1817), cf. (

Wallace 1997).

Michelangelo’s works became famous thanks to written accounts, including eulogies, factual descriptions, and pasquinades, as well as engravings, which were used profusely at that time to reproduce famous works of art and—since the fifteenth century—to disseminate devotional images. Early modern inventories evidence that prints after Michelangelo’s sculptures, paintings, and drawings were offered by Roman publishers, and often listed among devotional images (

Ehrle 1908); (

Pagani 2008a;

Pagani 2008b;

Pagani 2011;

Pagani 2012); (

Lincoln 2000); (

Rubach 2016). Some of these engravings were subsequently copied and copied again and thus contributed to the dissemination of the design, and were used in various contexts.

The reception of the Vatican

Pietà was ubiquitous in writings, but also in the visual culture of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Among many copies, reproductions, travesties, and pastiches executed in various techniques, some referred to the sculpture as Michelangelo’s masterpiece, some depicted it as an altarpiece of St. Peter’s Basilica, while some—and these are most relevant for our argument—used it as a point of departure for devotional images. In the previous research, the devotional value of the copies of the Vatican

Pietà, particularly those executed in graphic techniques, has admittedly been acknowledged (

Barnes 2010); (

Veress 2010–2011); (

Veress 2012); (

Alberti 2015), but several works remain unnoticed and thus various aspects of the phenomenon have been hitherto neglected. The aim of this paper is to elaborate on the less-explored pattern of the reception of the Vatican

Pietà, and thus to contribute to the discussion on how a masterpiece turns into a devotional image—sometimes for the sake of ‘simple folk,’ sometimes intended for a more sophisticated public—in a process in which various models are occasionally combined and the name of the original author often gets lost.

2. Fontainebleau: A Copy for the King

In a letter to Michelangelo, dated 8 February 1546, Francis I of France expressed his desire to possess the master’s works (

Carteggio di Michelangelo 1979). The King wished to purchase them via his agent in Rome, a Bolognese painter Francesco Primaticcio, whom he also asked to mould the Vatican

Pietà and the Minerva Christ, wanting the copies of these sculptures to be displayed in his chapel. While the whereabouts of the copy of the Minerva Christ remain unknown, the royal accounts of the 1540s include an entry for a Pietà in the Haute Chapelle du Donjon, the Royal Chapel of the Palace of Fontainebleau (

Comptes des bâtiments 1877). The 1642 description of the palace confirms that the Pietà, moulded after Michelangelo’s sculpture in the Vatican, was displayed on the right side of the altar of the chapel (

Dan 1642). Eventually, in 1664, the figure was moved to the Chapel of the Holy Trinity, which seems to be the last trace of this work (

Cox-Rearick 1995).

Now lost, the Fontainebleau cast was made to fulfil Francis’s personal desire as an art amateur, but it was also, like the copy in Santo Spirito in Florence and several others, displayed in a sacred place, even if it was not a publicly accessible church but the King’s chapel in his palace. This combination of aesthetic and religious motivations, on the one hand, and the intersection of the public and the domestic spheres, on the other hand, invite us to analyse the reception of Michelangelo’s sculpture as a masterpiece, as an altarpiece, and also as a model for devotional images. The Fontainebleau copy of the Vatican

Pietà was perhaps the earliest one north of the Alps (for despite some similarities, I do not believe the relief, dated ca. 1520, in the epitaph of Johann von Hatstein in the cloister of Mainz Cathedral to be a descendant of the Vatican Pietà; cf. (

Thode 1908)). The question arises, then, of how Francis I became familiar with particular Michelangelo works that he wanted to be copied. A possible intermediary was Primaticcio, one of several Italian artists working in Fontainebleau. Francis had already sent Primaticcio to Rome in 1540 to take casts of the most famous ancient sculptures, notably those from the Belvedere collection (

Dimier 1900); (

Cupperi 2010). It must remain conjecture whether the King relied on written or oral accounts, or had some visual sources at his disposal, such as drawings, rather than engravings. Prints are usually regarded as a typical medium by scholars. However, interestingly, Francis’s letter to Michelangelo ranks among the earliest responses to the Vatican

Pietà and the Minerva Christ and it also predates the printed reproductions of both works.

3. Intermediaries: Italian Engravings of the Mid-Sixteenth Century

Among the earliest Italian engravings after the Vatican

Pietà are two prints dated 1547. The one attributed to Antonio Salamanca and Nicolas Beatrizet displays the group of Mary and Christ against a ruined niche and is inscribed ‘Michelangelo Buonarroti of Florence divinely made from one stone the mother and the son for the [Basilica of] Saint Peter in the Vatican/Antonio Salamanca engraved in 1547, as much as it could be imitated’ (

MICHELANGALVS BONAROTVS FLOREN[inus] DIVI PETRI IN VATICANO EX VNO LAPIDE MATREM // AC FILIVM DIVINE FECIT // ANTONIVS SALAMA[n]CA QVOD POTVIT IMITATVS EXCVLPSIT 1547), which inevitably suggests to an erudite beholder that Salamanca reproduced a masterpiece that rivals ancient sculptures (

Figure 2). For a less-educated and, especially, illiterate spectator, however, it may not be clear if the engraving depicts a marble sculpture or Mary holding Christ on her lap (

Barnes 2010, p. 149). Thanks to this ambiguity, the print might satisfy a wide range of both learned art amateurs and faithful believers. It is, for instance, meaningful that Salamanca’s engraving was copied twice, still in the late sixteenth century (

Alberti 2015, nos. 311–13).

More unequivocal is the contemporaneous engraving by Giulio Bonasone, inscribed

MICHAELANGELVS BONAROTVS NOBILIS // FLORENTINVS INVENTOR IVLIVS BONASONIS F(ecit) (

Alberti 2015, no. 314) (

Figure 3). While the concise and factual inscription explicitly refers to Michelangelo as the inventor, the image obscures the material features of the original, as Mary and Christ are placed in the landscape, at the foot of the Cross among the instruments of the Passion (

Barnes 2010, p. 149). Thus, Bonasone took Michelangelo’s sculpture as a point of departure for his own representation of

Pietà, a widespread motif of Christian iconography. Such an attitude may also be traced back in two prints that are travesties rather than reproductions of the Vatican

Pietà: the engraving signed by Monogrammist PHPT, active in the late sixteenth century (

Alberti 2015, no. 318), to which we shall return, and the engraving by Mario Cartaro of 1564—the year of Michelangelo’s death (

Alberti 2015, no. 319).

In or soon after 1564, further engravings were produced, which testify to the development of the two different, even if occasionally merging, responses to the Vatican

Pietà. Giovanni Battista de’ Cavalieri admittedly showed Mary and Christ with a cross in the background, but his print clearly reproduces the sculpture, together with the rocky ground on which Michelangelo situated the figures, and the erudite caption contains homage to Michelangelo and no explicit reference to devotion (

Alberti 2015, no. 316); (

Jurkowlaniec 2015, p. 184). Adamo Scultori depicted the sculpture too, but he situated it in front of an opening in the rock, thus alluding to the rock-cut tomb of Christ (

Alberti 2015, no. 315) (

Figure 4). Moreover, in the second (out of four) state, dated 1566, Scultori’s engraving was inscribed: ‘Michelangelo Buonarroti accomplished these statues, which can be seen in the Vatican, so accurately, that you rather mourn the virgin Mother, scarcely breathing, pale and exhausted, and the pitiable dead body of her son, than suspect them erected of marble’ (

MICH(ael) ANG(elus) BONAROTVS signa haec, quae in uaticano uisuntur, ita exacte perfecit, ut potius Parentem uirginem // extremo spiritu exanguem & confectam, et nati corpus miserabile emortuum doleas; quam de marmore positum putes). Various literary allusions to ancient poetry included in this caption are in the service of devotion (

Jurkowlaniec 2015, p. 179). A beholder is invited to contemplate ‘the pitiable dead body’ of Christ and the ‘scarcely breathing’ Mary (a quote from Cicero,

For Sestius 37. 79). Hence, the inscription is addressed to a pious faithful rather than to an art amateur, but even the latter, touched by the suggestive value of the representation of the

Pietà, is expected to forget the material qualities of the marble statue.

Thus, the early engravings after the Vatican Pietà constantly oscillate between two genres. One may be labelled as ‘reproductions of a masterpiece,’ the other as ‘devotional images after a famous design.’ Bonasone’s 1547 print is especially relevant for our further investigation, not only because it seems relatively closest to the latter group. Compared to other engravings after the Vatican Pietà, notably Salamanca’s, Bonasone’s print itself and, above all, its further reception in the mid- and late-sixteenth century, have not yet been studied.

4. Vienna: Woodcuts in the Syriac New Testament and Peter Canisius’s Little catechism

In 1555, Viennese printer Michael Zimmermann produced the famous

editio princeps of the Syriac New Testament, edited by Johann Albrecht Widmannstetter and financed by Ferdinand Habsburg (

Ketābā d-Ewangeliyōn 1555). The publication was illustrated, but the woodcuts have remained almost hitherto overlooked in the scholarly literature, with the sole exception of

The Crucifix and the Sephirotic Tree preceding and concluding St. John’s Gospel on fol. 101

v and [fol. 158

r], respectively (

Wilkinson 2007). Further allegorical images—two diagrams and the triumphal Cross—recur in the publication a few times each, but a special emphasis must be placed on the

Pietà that concludes the section of St. Paul’s epistles (

Figure 5).

Several motifs of the Pietà—Christ’s pose, Mary’s gestures and dress, the shape of both nimbi, the lowered line of the horizon and the arma Christi displayed in a characteristic manner, with the scourges hanging from the beam of the Cross and, in particular, the lance and the rod with the vinegar-soaked sponge forming a V-shape—undoubtedly follow Bonasone’s engraving. However, there is no reference to either Bonasone or Michelangelo. Instead, the Syriac inscription cites Psalm 34[33]:6:

ܢܸܚܦܪ̈ܵܢ ܠܵܐ ܘܐܲܦܲܝ̈ܟ̇ܘܿܢ ܒܹܗ. ܘܣܲܒܲܪܘ ܠܘܵܬܹܗ ܚܘܼܪܘ

—that is, ‘Come ye to him and be enlightened: and your faces shall not be confounded’ (all English quotes from the Bible are from the Douay-Rheims Catholic Bible).

The Pietà is not a mere devotional image here, as the assumed audience of the translation of this New Testament was not only the Syriac Christian community, but above all, learned humanists. It is meaningful, for instance, that the woodcuts are inscribed in Latin and Syriac, some also in Greek, while the abbreviation of ‘Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews’ in the titulus of the Cross (cf. John 19:19) is consistently given in Hebrew (ינמה as an abbreviation of היהודים מלך הנצרת ישוע). Finally, some motifs also allude to the dynastic or imperial identity of the patron, Ferdinand Habsburg, as a crested, mantled helmet and the Habsburg coat of arms flank not only the Pietà but also the triumphal Cross.

These two woodcuts were apparently conceived as counterparts. The Cross is associated with a triumphal wreath and the small figure of a lamb trampling upon a lion and a dragon, referring to Psalm 91(90):13. While the Syriac inscriptions vary in particular impressions throughout the publication, the Latin caption ‘in this sign thou shalt conquer and thou shalt trample underfoot the lion and the dragon’ (In hoc Signo vinces, & conculabis Leonem & Draconem) invariably combines the famous augury of Constantine the Great’s victory in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, subsequently used as a motto in diverse, usually military, contexts, with the quote from Psalm 91 (90), considered to be a prophecy of Christ’s victory over death and Satan.

Consistent with common practice, the woodcut blocks used to impress the illustrations in the first edition of the Syriac New Testament were reused in the second edition published in 1562 (

Ketābā d-Ewangeliyōn 1562). Before that, however, both the

Pietà and the triumphal Cross also recurred in another work printed by Zimmermann: Peter Canisius’s

Summa doctrinae Christianae: In usum Christianae pueritiae per quaestiones recens conscripta—the so-called

Parvus catechismus catholicorum, or

A little catechism for Catholics.

This version of Canisius’s catechism was intended primarily for students. Zimmerman published it several times, usually with illustrations (the only exception is

Canisius 1558a) and invariably preceded by Ferdinand Habsburg’s 24 August 1554 letter to the reader, but with no date on the title pages or the colophons. The repertoire of the woodcuts is repetitive, but not identical (

Table 1) (

Streicher 1933); (

Palmer Wandel 2015).

Christ among the children, impressed from three diverse matrices, appears after the preface, a clear allusion to the assumed audience of Christian youth, as declared in the title. The

Crucifixion scene, in turn, consistently impressed from one woodblock of rather poor quality, recurs before the chapter on Christian justice. The same

Crucifixion matrix was used to impress the illustration on the verso of the title page in what is believed to be the

editio princeps. In subsequent editions, the

Crucifixion was replaced by the

Pietà as the opening scene, of which Zimmermann had two similar matrices at his disposal (

Figure 6). One was the block known from the Syriac New Testament, modelled on Bonasone’s engraving. The other, with the date 1556 in the lower left corner, is distinguished by a similar composition, but Mary’s gesture, the position of Christ’s arm, and both nimbi as well as various details in the background were designed independently or informed by another model. One has to remember that the

Pietà was a popular iconography; many painters and printmakers situated the group of Mary and Christ in a landscape; also the V-shape of the

arma Christi is far from unique.

Regardless of the matrix used, in the Latin editions both Pietàs were provided with almost identical inscriptions referring to Christ as the Suffering Servant from the Book of Isaiah: ‘by his knowledge shall this my just servant justify many’ (In scientia sua / iustificabit ipse // IVSTVS servos meos / multos. Esaias Cap. LIII—Isaiah 53:11). The 1556 Pietà was subsequently reprinted in the German edition of the catechism, this time, however, with the inscription travestying St. Paul’s preaching on the crucified Christ ‘who of God is made unto us wisdom, and justice’ (Jesus Christus / d(er) gecreuziget // ist der anfang / und das end // unserer weis/heit un(d) gerech/tigkeit—cf. 1 Corinthians 1:26–30).

The Pietàs in the books printed by Zimmermann were provided with various Biblical verses that invite the reader to contemplate the mystery of redemption. Neither illustration appears to have been considered a reproduction of a masterpiece or even of an altarpiece image. Still, the question arises whether Zimmermann or the Formschneiders who worked for him were aware of the origins of the design. This awareness cannot be excluded in the case of the earlier woodcut, which seems to rely directly on Bonasone’s engraving which, in turn, explicitly referred to the original. A conscious reference to the Vatican Pietà is much less plausible in the case of the woodcut dated to 1556. This one should be regarded as the next generation of descendants of Michelangelo’s design, mediated first by Bonasone’s engraving and then by the 1555 woodcut, maybe combined with another model. This sequence is plausibly the earliest, but not the only chain of works initiated by Bonasone’s print and thus ultimately—even if unintentionally—anchored in Michelangelo’s sculpture.

5. Fiammingo a Roma: Cornelis Cort for the Sake of Devotion

The undated

Pietà signed by Cornelis Cort—a Dutch engraver active from 1565 until his death in 1578 in Italy, among other cities in Rome—at first fails to evoke any associations with the Vatican

Pietà (

Figure 7). Scholars consider the engraving to be ‘after an unidentified artist’ (

Sellink and Leeflang 2000). The pose of Christ differs from that in Michelangelo’s sculpture, while Mary’s gestures are reminiscent of various prints after the Vatican

Pietà, and specifically the Cross with the scourges seems to be an abridged version of Bonasone’s design, maybe combined with another invention. In Cort’s print, the

Pietà is the main image, in an oval frame, set within an aedicule with a scene of the Deposition in a cartouche at the bottom. Such a composition may resemble an altarpiece, but it does not seem to represent one and the print’s dimensions, only 13 × 9.1 cm, are typical of popular devotional images. Lorenzo Vaccari—the publisher whose address was added in the second state (

Laurentium V[accarium] Formis Romae) together with the date 1580—plausibly offered this print among the small devotional images, some of which were ‘in an oval’ (

in ouato), an expression recurring in his 1614 inventory. However, it is impossible to point to a particular entry, because while the bigger prints in Vaccari’s stock (

fogli imperiali and

fogli reali) are often attributed to specific engravers and, rather exceptionally, to inventors, the names only occasionally appear with respect to the medium-sized prints (

mezzi fogli) and are never given in the case of smaller ones (

diuersi quarti fogli). Thus, only tentatively may one consider

La Madonna della Pietà or

La Madonna con il Signore as possible correspondences to Cort’s

Pietà (

Ehrle 1908, p. 66, lines 666 and 734).

Whatever the sources of Cort’s

Pietà, it became a model for later engravings. One of these is as a small print in a rectangular frame, inscribed ‘Surely he hath borne our infirmities and carried our sorrows’ (

VERE LANGVORES N[ost]ROS IP[s]E TVLIT / ET DOLORES N[ost]ROS IP[s]E PORTAVIT—Isaiah 53:4), another fragment of the prophecy of the Suffering Servant, also quoted in the woodcuts in the Vienna editions of Canisius’s catechism (

Figure 8a, cf.

Figure 6). Given the dimensions and the inscription, it can be concluded that the engraving after Cort’s

Pietà was conceived as a devotional image. However, some devotional objects became collectible items, as testified by the impression owned by Jan Ponętowski, a Polish nobleman who gathered an ample collection of prints between 1580 and 1587, while abbot of the Premonstratensian monastery in Hradisko, near Olomouc (

Hordyński 2016). Ponętowski’s collection is multifarious thematically, and it includes both artistic engravings and rather mediocre prints. The inconspicuous

Pietà was impressed on one sheet together with fifteen other images, predominantly representing religious subjects (

Figure 8b). Further examples of engravings after Cort’s

Pietà, all in oval frames, can be found in the Wolfegger Kabinett, one of the largest private collections of graphics (Kunstsammlung des Hauses Waldburg-Wolfegg, vol. 147, no 91: subscribed

Attendite et videte si est dolor sicut dolor meus, Thren 1, signed

F. Campion fe[cit] and

Herman Weyen excud[it]; no 136: signed

J[ohannes] sadeler excud[it], no 137: subscribed

ATTENDITE VNIVERSI POPVLI, ET VIDETE DOLOREM MEVM, no 150 with inscriptions

VENITE AD ME OMNES Matt[haeus] 11 and

O quam tristis et afflicta fuit / Illa benedicta mater vnigeniti).

The group of Mary and Christ drawn from Cort’s engraving can also be found as the central motif of a much bigger and elaborate devotional print: the

Rosarium dolorosum gloriosae Virginis signed by Giulio Roberti and Natale Bonifacio in 1579 (

Iulius Robertus exc[udit] Romae Natalis Bonifacius inventor atque Fecit 1579.) An impression preserved in Anzio (Biblioteca Clementina, 470 × 351 mm) is included in a collection of devotional engravings from the stock of Antonio Lafreri’s heirs (

Marigliani and Biguzzi 2010, no. 85). Their inventories mention several prints representing the Rosary (

Pagani 2008a;

Pagani 2008b;

Pagani 2011;

Pagani 2012), while solely Vaccari’s index includes an entry ‘Sorrowful Rosary engraved by Natale Bonifacio’—

Rosario doloroso con li misterij, intagliato da Natale Bonifacio (

Ehrle 1908, p. 61, line 94).

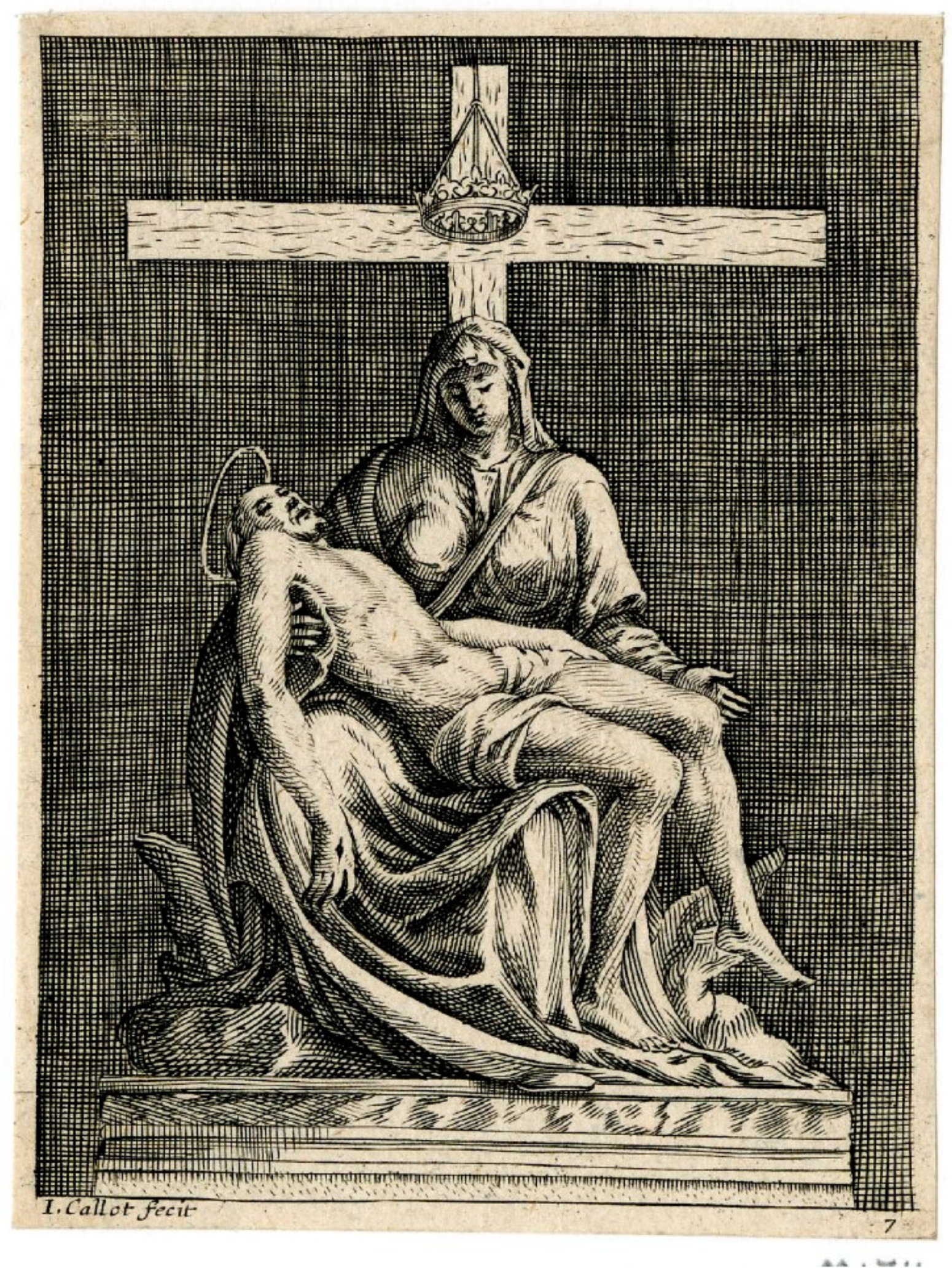

6. Between Rome and Nancy: Jacques Callot for the White Penitents

Yet another

Pietà resembling Cort’s engraving (in mirror image) is Jacques Callot’s etching for the frontispiece of

Règlement et établissement de la Compagnie des Pénitents blancs de la Ville de Nancy (

Règlement et établissement 1635) (

Figure 9), subsequently copied in the eighteenth century in the woodcut technique (

Meaume 1855), (

Dompnier and Vismara 2008). It is impossible to state whether Callot represented a painting or a sculpture displayed in the architectural framing and still less whether he portrayed a real altar with an existing panel, as he did on the frontispiece of the

Miracles et graces de N. Dame de Bon Secours les Nancy (

Miracles et graces 1630), (

Choné 1992), (

Châtellier 1993). The

Notre-Dame de Bonsecours, a relief by Mansuy Gauvain (died after 1542), is still preserved in the Bonsecours church, but the chapel (subsequently the collegiate church) of St. Michael Archangel in Nancy, given to the White Penitents in 1634, was destroyed in 1793. In 1779, Jean-Joseph Bouvier Lionnois described the chapel of the White Penitents as having no distinguishing elements in either its exterior or interior (an opinion repeated by later authors), with the choir of the congregation decorated with a number of pious images (

plusieurs tableaux de piéte); he mentioned a few interesting objects preserved in the church but no altarpiece with the

Pietà (

Lionnois 1779, pp. 340–42); (

Lionnois 1805, pp. 215–16); (

Lepage 1838).

Whether or not a depiction of a real altarpiece image, the

Pietà of the White Penitents does not seem to be intended as a reproduction of Michelangelo’s sculpture. This is particularly interesting, as Callot not only knew the Vatican

Pietà, but he even reproduced it in the early seventeenth century (

Figure 10). Born in Nancy, Callot was active in Rome between 1608 and 1611 and his

Delineationes picturae altarium in Ecclesiis S. Petri et S. Pauli Romae, also known as

Les Tableaux de Rome or

Les Eglises jubilaires, certainly included the Vatican

Pietà, as it was placed in one of the privileged altars of St. Peter’s Basilica (

Loire 1993, pp. 98, 104–5); (

Harent 2012, p. 208); (

Meyer 2012). The

Pietà of the White Penitents, engraved after Callot had returned to his hometown, seems rather unrelated to his

Pietà from

Les Tableaux de Rome, while close to the

Pietà by Cornelis Cort, considering the poses and gestures of Christ and Mary, especially the scourges hanging from the horizontal beam of the Cross (

Figure 7). Thus, on the title page of

Règlement et établissement de la Compagnie des Pénitents blancs de la Ville de Nancy we find a third- or even fourth-generation descendant of Michelangelo’s masterpiece, being at the same time an altarpiece image: mediated first by Bonasone’s engraving, then Cort’s engraving and—perhaps—the unpreserved altar panel in the Confraternity of White Penitents in Nancy.

7. Augsburg: Lucas Kilian for a Learned Lithuanian Cleric

The ambiguous status of many works regarded as both masterpieces and religious images is far from unusual and a shifting back and forth between the realms of masterpieces, altarpieces, and devotional prints is well attested in the early modern period. An example is the

Pietà by Hans von Aachen of ca. 1596, originally placed in a chapel of the Wilhelminische Veste, later known as Herzog-Max-Burg, in Munich. The painting, destroyed in 1944 and known from archival photographs (

Figure 11) (

Peltzer 1911–1912), was subject to various adaptations ca. 1600 (

Jacoby 2000). One of these is the

Pietà by Lucas Kilian, one of the most productive Augsburg printmakers of the early seventeenth century (

Zijlma and Anzelewsky 1976, no. 51), (

Jacoby 1996). The engraving is inscribed

S(uae) C(aesareae) M(aiestatis) pictor Ioan(nes) ab Ach(en) pinxit and signed

Lucas Kilian(us) Aug(ustanus) scalps(it) Venetijs (

Figure 12). Thus, the work was explicitly referred to as modelled on Hans von Aachen’s invention and executed in Venice, where Kilian stayed between 1601 and 1604 (

Trevisan and Zavatta 2013). However, the

Pietà after Hans von Aachen was not only a reproduction of a painting, but also a pious gift.

Two further names appear in the lower margin, where the publisher, Dominicus Custos (Kilian’s stepfather and teacher), dedicated the engraving to Johannes Philipp von Gebsattel, the Prince-Bishop of Bamberg, ‘when he was crossing Augsburg’ in May 1602. The dedication is preceded by a verse from the Lamentations of Jeremiah ‘[there is no] sorrow like to my sorrow’ (NON EST DOLOR SI/CVT DOLOR MEVS—Lamentations 1:12). Thus, the expression … AVGVSTAE VIND[elicorum] TRANSEVNTI … referring to Gebsattel ‘crossing Augsburg’ may be understood literally, but at the same time it recalls the beginning of the verse from the Lamentations, which reads in its entirety O vos omnes qui transitis per viam, attendite, et videte si est dolor sicut dolor meus!—‘O all ye that pass by the way, attend, and see if there be any sorrow like to my sorrow!’.

Thus, Kilian used Hans von Aachen’s Munich altarpiece as a model for an engraving, whereas Custos skilfully chose a Biblical quote for a dedication that responded to both the iconography and the circumstances. Gebsattel’s visit to Augsburg was an opportunity that was not to be missed, as the mighty Prince-Bishop might turn into a patron. Therefore, Custos not only dedicated the

Lamentation to Gebsattel but also engraved his portrait in 1602 (Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1918-1075,

http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.100185). In the early seventeenth century, offering devotional prints and portraits to prominent personalities was a common strategy for capturing customers among Church hierarchs and members of noble families and Augsburg attracted visitors from various countries, which brings us to the final example of indirect reception of Michelangelo’s Vatican

Pietà.

In early 1604, a Lithuanian magnate, Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł ‘the Orphan’ (Lithuanian:

Mikalojus Kristupas Radvila Našlaitėlis) dispatched his sons to study in Augsburg (

Chachaj 1995). They were welcomed by Eustachy Wołłowicz (Lithuanian:

Eustachijus Valavičius), a protonotary apostolic, provost of Trakai, custos of Vilnius, and referendary of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, who travelled through Europe at the time and who, encouraged by Radziwiłł, stayed in Augsburg for a few months to accompany his sons. The visit of the young Radziwiłłs proved particularly fruitful for the Augsburg engravers, who found keen customers among the Polish and Lithuanian nobles, and Wołłowicz was portrayed thrice by Kilian: first in 1604, and subsequently, as Bishop of Vilnius, in 1618 and 1621 (

Zijlma and Anzelewsky 1976, nos. 492–494). The date of the earliest portrait coincides with Wołłowicz’s sojourn in Augsburg, when another print dedicated to him was also created: a

Pietà explicitly, even if indirectly, referring to Michelangelo (

Figure 13), (

Zijlma and Anzelewsky 1976, no. 52).

According to the inscriptions, the engraver, Lucas Kilian (L[ucas] Kil[ian] A[ugustanus] fecit), used as a model Michelangelo’s work ‘painted in Rome’ (MICHAEL. ANG[elus] // B[onarotus] pinxit Romae). Actually, Kilian did not reproduce the Vatican Pietà, but almost slavishly copied one of its travesties, the aforementioned late-sixteenth century print by the Monogrammist PHPT, which also includes an identical reference to Michelangelo. However, Kilian’s Pietà, like his earlier Lamentation after Hans von Aachen, was additionally provided with a dedication in the lower margin, also subscribed by Dominicus Custos. The inscription begins with a caption from Jeremiah: ‘My sorrow is above sorrow, my heart mourneth within me’ (DOLOR MEVS SVPER DOLOREM, IN ME COR MEVM MOERENS—Jeremiah 8:18), and continues with an address to Wołłowicz dated 1604 in Augsburg.

The future Bishop of Vilnius (1616–1630) Eustachy Wołłowicz, renowned as both religious cleric and sophisticated humanist, studied in Rome from 1593 to 1596 where he was ordained subdeacon on 24 September 1594 and deacon on 13 April 1596 (

Jujeczka 2018, no. 77). He had a chance to see Michelangelo’s

Pietà then, but it is not confirmed that he did. It is also not known how he received the

Pietà dedicated to him in 1604: as a token of his past visit to Rome, as a reproduction of Michelangelo’s famous work, as a devotional image—or as all of these. However, there is a record of how the Radziwiłł brothers spent time in Augsburg, studying but also devoting themselves to various religious practices, often accompanied by Wołłowicz. Learned Jesuits played a prominent role in their milieu, such as Matthäus Rader who dedicated a collection of exempla,

Viridarium Sanctorum, to the Radziwiłłs on 29 September 1604 and

Syntagma de statu morientium, to Wołłowicz on 30 September (

Rader 1604a;

Rader 1604b; VD17). Soon afterwards, in early October, Wołłowicz left Augsburg and headed again to Italy.

8. Conclusions

Long before its official coronation in 1637, the Vatican Pietà proved to be a direct or, admittedly much more often, an indirect model for various devotional images. Between Primaticcio’s 1546 copy ‘on the right side of the altar’ of the Royal Chapel in Fontainebleau palace and Callot’s 1635 frontispiece of the Règlement et établissement de la Compagnie des Pénitents blancs de la Ville de Nancy, perhaps representing the altarpiece of the chapel of the White Penitents, there is a wide group of graphic images. Several printmakers responded to the Vatican Pietà as early as the mid-sixteenth century, and some of their works were copied repeatedly. The engravings were not always accurate, and as they gradually moved away from the appearance of Michelangelo’s sculpture, the remote original design and its author were often forgotten. In addition, the contexts and the recipients—if known—are of essence here. Even some single-sheet engravings clearly conceived as reproductions of the statue carved by Michelangelo were provided with inscriptions that appeal to believers rather than to art amateurs. Some engravings do not depict the marble sculpture, but rather represent a religious scene and name Michelangelo as the inventor. Giulio Bonasone’s 1547 print is particularly prominent, as it stands at the beginning of the whole chain of interrelated works, multifarious with regard to quality, contexts, and assumed audience. There are mediocre anonymous woodcuts and elaborate engravings and etchings by renowned masters from various countries including Cornelis Cort, Lucas Kilian, and Jacques Callot. There are single-leaf prints, title page images and illustrations in Biblical books and catechisms. Some may be regarded as images for the sake of ‘simple folk,’ some were devised for sophisticated scholars or even specific individual addressees, but all the intended recipients were, after all, pious Christians. Therefore, Michelangelo, called ‘the inventor of filth’ by an otherwise unknown author of the mid-sixteenth century, at the same time turned out to be an involuntary inventor of devotional images.