1. Introduction

Spiritual health is a neglected aspect of rehabilitation following trauma as shown in Carey and Mathisen’s review of spiritual care for allied health practice (

Carey and Mathisen 2018). The increasing recognition that spirituality is an important part of health (

Faull and Hills 2006;

Koenig 2012), and merits special consideration in chronic health conditions (

Do Rozario 1997), requires translation into practice. Specifically, little is known about the spirituality of people following traumatic brain injury (TBI), including those with acquired aphasia (language impairment) and how they adjust post-traumatically in the presence of ongoing linguistic and cognitive impairments. There are many definitions of aphasia. According to Code and Petheram’s review, ‘Relatively non-controversial is that aphasia is the generic term we use to describe a range of impairments in language use following brain damage’ (

Code and Petheram 2011, p. 3). Aphasia can impact receptive and expressive language and communication, including the underlying verbal processes such as language-based thinking.

Changes in identity following TBI were found in a study of 29 participants by (

Carroll and Coetzer 2011). They excluded people who could not complete standardised questionnaires due to language or communication impairment, so it is unlikely that aphasia was well represented. The study identified emotional adjustment and grief as part of identity change, but it used a psychological paradigm without reference to spirituality.

Some accounts of aphasia and spirituality have applied models and theologies developed in relation to disability and illness in general (

Mundle 2011). Mundle clearly recognized the importance of listening to people with aphasia, but without going as far as co-constructing such accounts with people with aphasia. Furthermore, there is no denying that accounts drawn from carer perceptions are rich and moving (

Hale 2017). Caution is needed nevertheless, since carer accounts have been shown to differ from those with aphasia (

Gillespie et al. 2010). Whilst illuminating, such accounts do not draw their narratives directly from people with aphasia. Maori studies show that spiritual frameworks in aphasia need to encompass a range of belief systems, including those where spirituality is regarded as collective rather than individual (

McLellan et al. 2014), another reason for starting with the experience of those with aphasia.

Recent work published about spirituality and aphasia included qualitative studies of case series or single cases post-stroke. Laures-Gore, Lambert, Kruger, Love and Davis Jr. (

Laures-Gore et al. 2018) interviewed 13 adults with ‘mild’ aphasia post-stroke about their spirituality, with a questionnaire that showed nine of them identified themselves as religious and spiritual, and the other four as spiritual. They identified two main themes concerning a ‘greater power’ being in control of events and acting as a helper.

MacKenzie (

2017) interviewed eight single cases, using the word ‘mosaic’ to encapsulate the non-verbal individuality of the stories. Her findings underlined the need to facilitate communication in people with aphasia for exploring their spirituality, and she viewed her work as exploratory.

Issues specific to aphasia concerning spiritual health and well-being require better understanding, including more complete diagnostic details beyond the label ‘mild’ aphasia. This would inform support for those adjusting to experiences of loss in aphasia. People with aphasia benefit from adaptations to improve communication access, just as adaptations using ramps would improve wheelchair access. Techniques for improving communication involve ‘aphasia-friendly’ practices which are well documented (

Simmons-Mackie et al. 2007;

Rose et al. 2012;

Stroke Association 2012). Such techniques involve modifying the environment, simplifying written and spoken communication, including non-verbal support and resources, forming a routine part of speech and language therapy (SLT) practice. Understanding the needs of people with aphasia for accessible communication may offer a channel for simplifying the terms generally used in spirituality.

This paper explores insights gained from collaborating with people with aphasia about spirituality in a feasibility study of a novel intervention called WELLHEAD. It focuses on a single case with TBI, (referred to here as ‘Mrs. Green’) in the absence of any comparable published accounts. The project crosses traditional boundaries between medical, psychosocial and spiritual models, building on previous work in adjustment to long-term aphasia (

Mumby and Whitworth 2013) and a model reported in

Mumby and Hobbs (

2017). WELLHEAD was originated by Mumby, a practicing SLT, in response to a perceived vacuum for accessible spirituality assessment and intervention in aphasia. WELLHEAD is a framework consisting of four dimensions, WIDE, LONG, HIGH and DEEP, for exploring spirituality as ‘meaning and purpose’. This definition was confirmed by the steering group for the study, comprised of five people with aphasia. The background to designing WELLHEAD is outlined, and the WELLHEAD framework is summarised in relation to other current models of spirituality in

Mumby and Grace (

forthcoming). The prototype materials (WELLHEAD toolkit) which formed the basis for the feasibility study are described briefly in the Method, below and by

Mumby (

2018), comprising a structured interview framework, self-assessment and goal- setting.

This single case narrative is important for understanding how those with aphasia and TBI experience spirituality, including their spiritual awareness and spiritual health. The aim was to use language chosen by the participant, using principles of non-judgmental open listening, and reducing the intrusion of the researcher’s own perspective, whilst acknowledging the inevitable part that played in the co-construction of the narrative. In-depth narratives are also particularly important for resolving ambiguities prevalent in the context of aphasic communication (

MacKenzie 2017), including misunderstandings that may be overlooked in applying quantitative measures alone. The narrative aimed to incorporate quantitative measures with an in-depth qualitative exploration using thematic analysis, a method previously used in aphasia by

Mumby and Whitworth (

2012,

2013). The narrative also illustrated the flexibility and scope of WELLHEAD.

2. Method

2.1. A Single Case Narrative from a Case Series

A feasibility study of the WELLHEAD spirituality toolkit using a case series of 10 people with aphasia was conducted in a health service outpatient setting in accordance with health research authority ethical approval (Study reference: IRAS id 216 799

https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/application-summaries/research-summaries/aphasia-and-spirituality-toolkit-pilot-study-version-1/). The overarching findings are being reported in detail elsewhere, (

Mumby and Roddam 2019; see also

Mumby and Roddam 2018) with the focus here upon in-depth dialogue with a participant with TBI. Prior to the study, a steering group of people with aphasia collaborated with the researcher to select the spiritual health assessment, Spiritual Health and Life Orientation Measure (SHALOM (

Fisher 2010)), from the existing published resources. This independent measure had no prior use with people with aphasia. A self-assessment protocol (patient reported outcome measure, or PROM) formed an integral part of the WELLHEAD toolkit, providing comparison scores, as part of the results.

The toolkit was designed to be used in an interview context, supporting conversation and reflection for those with aphasia using a range of pictures selected by the participant, word boards and starter questions. These related to the 4 dimensions of WIDE, LONG, HIGH and DEEP, with a deliberate progression from the most neutral terms to more specific terms as directed and chosen by the participant. The word boards were a short visually accessible list of written key words from which Mrs. Green could select a word as a focus for what she wanted to communicate. Similarly, where preferred, she selected pictures (mainly photographs) from a range of choices in each dimension. The written forms of the starter questions were available on a separate page for joint reference during consideration of each dimension. The focus of each dimension is summarised in

Table 1.

Mrs. Green gave self-scores using a visual analogue scale (1–10) as discussion of each dimension was completed, where 10 signified where they wanted to be, and 1 was the furthest from this. Accordingly, the score reflected current experience in that dimension. After completing all the dimensions, the use of further word boards and pictures helped identify personalised ‘Next Steps’ as a form of goal-setting based on the exploration. Principles of total communication were adopted to offer additional communication support (

Byng et al. 2001). At regular intervals during the interaction, interpretations were checked with Mrs. Green, who also verified a simple written summary of the WELLHEAD findings. This included self-scores and goal-setting alongside summary phrases agreed with her over the course of the discussion.

The WELLHEAD interview was preceded on the same day by the SHALOM questionnaire, with extra communication support to complete this task. Breaks with refreshments were given. Finally, Mrs. Green completed a feedback interview based on a short written questionnaire.

The WELLHEAD written summaries and the SHALOM results were emailed to Mrs. Green for verification (according to her communication preference), and she was invited to offer comments. Part of safeguarding entailed offering unconditional follow-up with the hospital chaplain. Mrs. Green declined this option.

2.2. Three Phases of Analysis and Verification

The WELLHEAD interviews and feedback interviews were all videoed. Transcripts of the feedback interviews underwent systematic thematic analysis within NVivo, which was verified for consistency of coding in relation to the data by an independent researcher familiar with aphasia, in combination with reflective field notes, the numerical scores and written records. Three overarching themes were derived from this first phase of the analysis concerning accessibility, acceptability, and impact of the approach.

As part of exploring impact in more depth, a second phase of analysis focused on the summary findings from WELLHEAD which had already been verified by each participant, with additional independent review to ensure the thematic analysis was robust. The third phase of analysis used additional transcription of the full WELLHEAD interview to provide a more extensive thematic exploration concerning individual spirituality in comparison with the summary. The choice of Mrs. Green as the forerunner for this in-depth analysis was based on her active engagement with the research process, and her mid-way place in the sequence of interviews, which was deemed to be representative of the nature of the interviews as an overall case series.

Verification with participants as part of the data collection was augmented via two optional group feedback sessions. All the participants were invited to review the results in general and share their reactions, giving additional verification. Confidential one-to-one liaison concerning specific results was provided with prior consent by email according to personal preference, and in a limited way in private one-to-one conversations when participants attended the feedback sessions. Mrs. Green was provided with a full transcript. She also verified the findings by checking the content of the abstract of this paper, and the content of

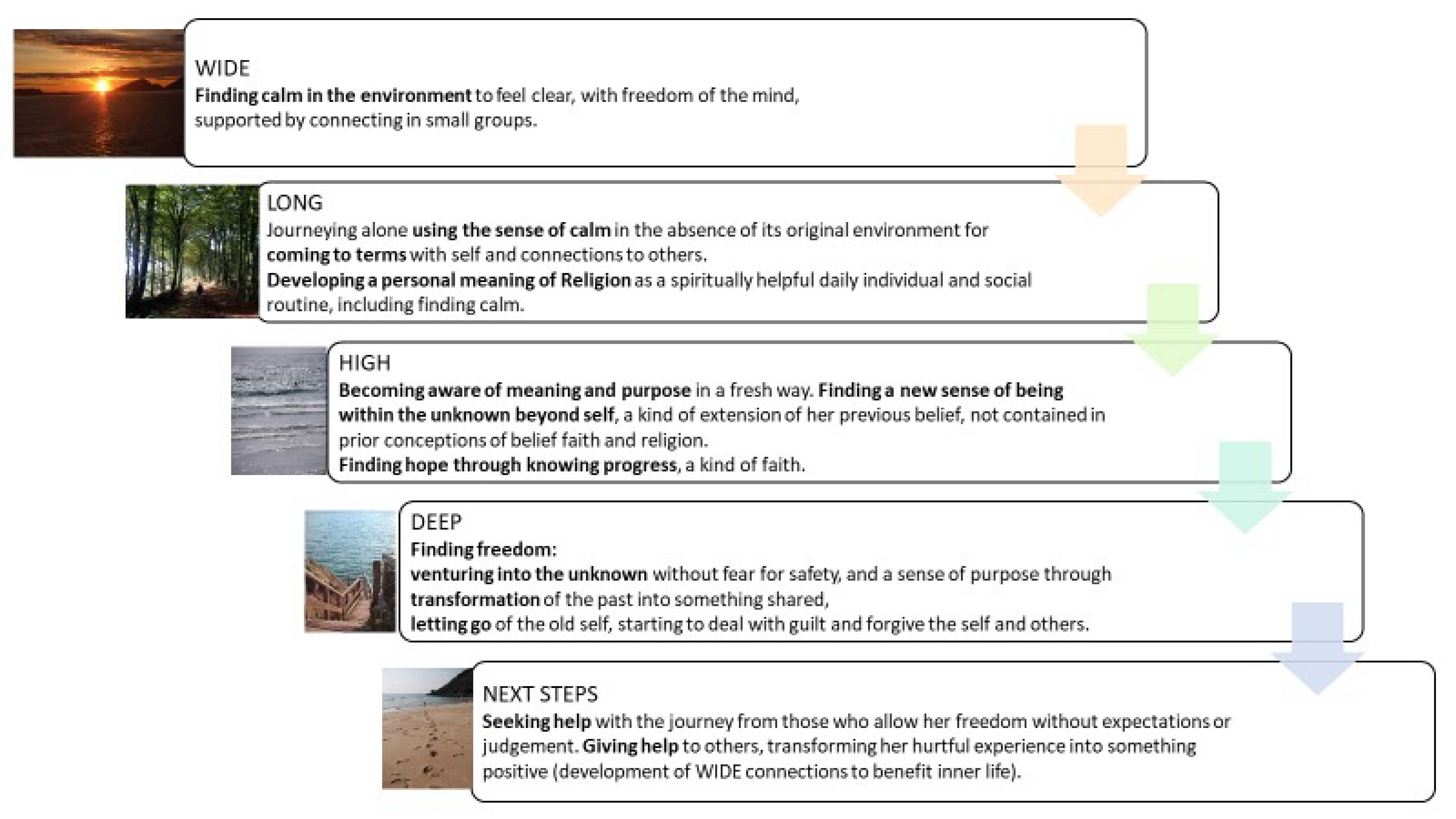

Figure 1, the summary of processes emerging from the narrative.

2.3. Participant Characteristics

Detailed information was extracted and anonymised from the SLT notes. Mrs. Green had been discharged from SLT eight months prior to recruitment, and she had consented at that time to being contacted about research opportunities, in accordance with local governance procedures. Mrs. Green’s persistent impairments all concerned verbal deficits, in the context of some generalised fatigue. She confirmed the SLT’s opinion at interview that her recovery had plateaued.

Mrs. Green sustained a traumatic brain injury 26 months earlier in her workplace following a fall, with loss of consciousness of an unknown duration. She had two days of anterograde amnesia. Brain (CT) scanning revealed no focal damage. She had suspected post-concussion syndrome with concomitant headaches, fatigue and cognitive changes involving verbal processing, with the primary symptom of aphasia. No MRI scan was carried out but small areas of neuroaxonal injury were suspected. She was expected to return to her work role after making a physical recovery but was referred for SLT for her ongoing aphasia seven months post-onset. She attended two courses of outpatient SLT, offering individual assessment and intervention for her aphasia, with peer support in a small group of others returning to work with aphasia. Compensation for her injury was not pursued, but her work situation became unsustainable due to a lack of workplace support for her ongoing impairments. She eventually found alternative employment in the same sector about six months prior to her research interview.

Mrs. Green was 32 years old, married with no children. Her husband was supportive, but she reported he did not fully understand the impact of her aphasia. She had other close family in the area but had made little reference to them during therapy. She worked in a customer-facing management role in the entertainment sector. Despite having a good prior network of friends and family, she had become isolated following her aphasia.

Routine information from Mrs. Green’s SLT notes was used to confirm her diagnosis of mild receptive and expressive aphasia, to avoid subjecting her to additional testing. In summary, she had receptive language impairments which compromised processing of complex sentences, paragraphs and discourse, especially regarding abstract or infrequent vocabulary. Auditory verbal memory for sentence repetition and dictation was impaired and variable. Paragraph recall was mildly impaired, as was verbal problem-solving involving calculations. Receptive abilities using reading were stronger than auditory abilities. Her expressive language impairments comprised grammatical and semantic difficulties. She had trouble constructing complex sentences, and planning discourse, sometimes having to restart before her message was complete. Connected speech showed word-finding difficulties particularly for rarer, longer or more abstract words. She found it hard to maintain a conversation against background noise or in a group, or to multitask during verbal activity. She required structure and extra organisation to cope with normal work and home life demands. She used a Filofax with colour-coding diligently, keeping other memos on her mobile phone, and using written notes around the house. She needed to take regular breaks from verbal tasks to avoid build-up of fatigue. Her progress had plateaued at discharge from SLT.

For optimal communication access during the interview, Mrs. Green required the use of short simple sentences addressed to her, and repetition of any complex information, due to her ongoing auditory memory impairments. Her ability to process language was also augmented by offering visual information concurrently, such as written phrases or meaningful pictures. When reading paragraphs, her accuracy improved by re-reading several times and noting down key points. Similarly, in complex discussions, her ability to keep the thread of the conversation improved by having key written words in view as the conversation progressed. Yes/no questions helped to clarify the message. Auditory memory for sequences was aided by using ‘chunking’ techniques to subdivide longer sequences and had also been aided in therapy by using conscious visualisation techniques, so having pictures as reference points was helpful.

The most recent therapy outcome measure (TOMs,

Enderby and John (

2015)), consistent with her abilities at interview, were taken eight months prior to interview at discharge from SLT and are shown in

Table 2.

The designation of ‘normal range’ does not signify a return to pre-morbid levels of activity and participation, but these fell within the normal range based on the life Mrs. Green was now living. She conveyed that she now avoided certain situations and tasks to ensure optimum functioning. This is consistent with aphasia being a largely ‘unseen’ impairment, requiring internal compensation and life change hidden to onlookers, with the nature of the difficulties often being overlooked see ‘ignorance’, (

Mumby and Whitworth 2012, p. 407;

Worrall et al. 2013, pp. 106–7). She was living with chronic aphasia. Even though it was now classified as mild or ‘high level’ aphasia, her self-evaluation during therapy showed she felt she still needed to progress towards better functioning. This was illustrated in her SLT assessment by the modified Living with Aphasia Framework for Outcome Measurement (modified A-FROM,

Mumby and Whitworth (

2013), based on work using the International Classification of Function, (ICF (

WHO 2001)) by

Kagan et al. (

2008)). This holistic self-evaluation (regarding communication within life as a whole) addressed four domains (see

Table 3). The scores showed that despite objective progress in her levels of impairment there was little change in her overall self-evaluation.

The WHO classification places spirituality in the ‘personal’ domain, and spirituality was not referred to specifically by Mrs. Green during therapy. Interestingly, the A-FROM score for the personal domain at discharge from SLT (focusing on issues such as ‘how much do you feel the real you?’) was the only domain to have reduced in score over the course of therapy. At discharge, the lower ‘personal’ score underlined a sense of ongoing adjustment to her identity and sense of self (

Mumby and Whitworth 2013).

2.4. The Scope of the Narrative

The narrative being reported in detail arose from co-construction by the researcher and Mrs. Green of her spirituality using the structure provided by the WELLHEAD toolkit, combined with reflections on her response to SHALOM and the feedback sessions. In Mrs. Green’s case, the researcher had been the lead therapist in her SLT intervention, so good rapport was already established. However, it was not normal practice to address issues of spirituality as part of SLT (the subject of reflections in

Mumby and Grace (

forthcoming).

The researcher made clear as part of the feasibility study that she was interested in the participant perceptions rather than her own pre-conceived ideas, but that a neutral perspective was not ever completely possible. In consequence, little emphasis was placed on conveying the researcher perspective to participants prior to the interview taking place. As part of constructing the narrative process, the researcher acknowledged that her reflections were influenced not only by her role as therapist, but also by her role as a lay reader in the Church of England, and a personal experience of recovering from mild aphasia following viral illness contracted several years previously. After the interview recordings, there was an unstructured relaxed time of sharing out of mutual respect. Prior to the interview, Mrs. Green volunteered additional information about her new job role, which she perceived to be outside the interview itself. After the interview, in response to direct questioning, the researcher shared her own background concerning spirituality and aphasia in brief with Mrs. Green.

The narrative encompasses both quantitative and qualitative findings, which were scrutinised through the lens of this single case.

3. Results

3.1. SHALOM Scores

The results are summarised in

Table 4, below. Mrs. Green indicated that religion had very low importance in her life, scoring 1. Spirituality had moderate importance, scoring 3. The mean score was calculated for each of the four domains, showing some ‘dissonance’, a mismatch of ideals and experience. The Mean Lived Experience of spiritual health (3.25) was less than her Ideal score (4.2). Dissonance was evident in the personal and transcendental domains where the difference was greater than 1, see (

Fisher 2010).

3.2. WELLHEAD Interview, Scores and Goal-Setting

The summary of findings agreed with Mrs. Green is shown in

Table 5.

The phase three, in-depth thematic analysis is now presented, based on the interview transcripts and additional field notes, where ‘G’ signifies Mrs. Green, and ‘KM’ the researcher, using the dimensions as a framework. For economy, limited transcripts are shown rather than including lengthy context in which the message was assembled or intentions were established.

3.3. Deeper Exploration of the Themes within the Interview Transcript

The transcription of the 80-min interview comprised 14,232 words for the WELLHEAD interview, and an additional 749 words alongside the questionnaire for the feedback interview. Transcripts included facial expression and gesture. Non-verbal behaviours disambiguated communication in instances of word-finding difficulty and were an integral part of enhancing communication.

Findings from the thematic analysis will be summarized, starting with each WELLHEAD dimension. A synthesis of the analysis overall (regarding WELLHEAD and SHALOM) will include identification of the processes which emerged, corroborated by the participant, and researcher reflections about co-construction.

3.3.1. WIDE

Previously gregarious and enjoying large groups, Mrs. Green now preferred small groups where she could participate on a less intense level than one-to-one interaction. This shift reflected the ongoing limitations from aphasia. Her continuing need and desire to connect with other people especially concerned mutual support, which she still experienced in a real way. Support came from helping and being helped in a small group network. She also revealed near the end of the interview that she found it easier to connect with children such as her niece, who did not have prior expectations from how she used to converse or interact before the TBI.

She valued being by the sea for finding a sense of calm, and she used her memories of this (sight and sound) to induce the same feeling in herself elsewhere. She described how things became ‘Clear’ when she found ‘Calm’ via connecting to the environment, a freeing of the mind, releasing her from the cognitive and linguistic limitations from the aphasia. In this way, finding freedom was concerned initially with freedom of the mind and emotions.

3.3.2. LONG

Mrs. Green chose a picture of a person journeying down a tree-lined lane to symbolise her experience.

G: yeah…going forwards…and knowing that I’ve (gestures one hand moving forwards along table top)…can keep going…and go forward.

Journeying alone and coming to terms with doing things alone felt bad at first, being enforced by the aphasia. Now there was more positivity to the extent that she sought out aloneness for reflection and embraced it.

Aloneness was now a place where her new-found ability to meditate occurred and thoughts sedimented, part of her self-acceptance. Self-affirmation enabled her to persevere with ‘keeping on’. Overcoming blocks such as her impairment gave her a sense all was ‘clearer’, linked with the theme of Calm mentioned in WIDE. She described this in terms of recent transition as if she had crossed a bridge, making special reference to finding a new job.

Mrs. Green shied away from religious tradition but was comfortable to define tradition as personal routine, ‘the things you do regularly’, assigning value to this aspect of her own spirituality. She found routine and detailed organisation a necessary scaffold to enable her to cope with reduced cognitive and linguistic processing, and she was starting to value this as part of her new self.

3.3.3. HIGH

Mrs. Green was drawn to the term ‘Unknown’ rather than God, preferring not to engage with overt symbols or vocabulary concerning established religion. In this context ‘Hope’ was now very much part of her ‘Belief’ (based on information); and was the word she used in preference to ‘Faith’. She felt that she had changed spiritually because of her story, now with new openness to spiritual considerations. After initially losing hope following her injury, she now felt she had hope for the future ‘but not too much’, wanting to be realistic rather than having false hope. She relayed that she felt spiritually part of something beyond herself, with the scope to be part of the unknown, rather than the unknown being separate (encapsulated in a picture where the sea and sky merged). She also selected a picture of waves, where she articulated aspects of being at one with the unknown and others, commenting, ‘we’re all in it (points at person in waves, smiles, then laughs)’, with a sense of all things being part of something greater, experiencing pure ‘Being’, beyond self.

The huge sense of aloneness she did feel had left a mark on her sense of self and altered her perception of the unknown ‘Beyond self’. She felt her isolation (due to the aphasia) was unknown to others and there was a deep desire to be known. Aphasia had impacted both head and heart, and she was searching for more. Not inclined to spirituality before the TBI, she had started to change.

There was some focus on definitions of Religion, Faith and Belief at this stage which will be outlined in

Section 3.3.6 below.

3.3.4. DEEP

Mrs. Green described a sense of steps leading to a place of calm (steps leading down to the sea) to search for ‘Otherness’.

She conveyed that ‘Do you feel loved?’ was not such an important question as ‘Do you love yourself?’, illustrating her link between self-forgiveness and forgiveness of others. She explained that people loved ‘

the old me’ before the aphasia, and were still in the process of coming to terms with ‘

the new me’, so her own shift required both self-acceptance and acceptance of them:

G: Yeah, I do recognise that (points up with index finger) the importance of being loved…by other people…I s don’t necessarily feel…I’ve I suppose because of…my aphasia (opens hand and looks directly at KM, who looks thoughtfully slightly upwards)…I sometimes feel that…people loved the old me

KM: mm

G: more than the new me (looks back at steps picture)

KM: mm (nods)

G: and I still think that actually, sometimes (clears throat, looks towards KM)

KM: yes. So that’s where the ‘but’ comes in, is it?

G: but I. Yeah. But I think… the way for me to get past (circular motion with hand going forwards in the air) that is to know that I’m alright with myself (places hand on heart, looks to KM).

KM: (smiles, nods)

G: so if they other people aren’t then (shrugs, pulls face and rocks head slightly side to side)

KM: (points at DEEP word board: ‘Finding Meaning, Value’) it’s like ‘Finding Value’?

G: Yeah (…)

G: yeah, and I think that was very hard for a long time, so…(points back to steps picture) and I would be…happy being here on my own (turns to KM and laughs)

KM: yes...so that’s that that calm place where...actually you feel OK about yourself

G: yeah

Mrs. Green’s thoughts and reflections had helped transform bad feelings into more positive ones. She used a picture of a prism to represent the self, now better orientated to the light to create something new in the form of a rainbow spectrum. She had moved towards more self-acceptance, but still was questioning about the past, allowing herself to look at it differently and finding freedom in this.

G: yeah, and I will always think…I will always…(circular gesture) think about it, and have questions, you know internal questions about what happened, but I’m more.. accepting…I know

KM: mm (nods) mm

G: I think, which means I can allow myself to look at it differently

There was still a sense of guilt at having changed as a person, with others having to accept it, which has compounded her struggle to have a good sense of self-worth:

G: when you work through…this part (points to question: ‘can you work through feelings such as guilt, inadequacy, shame, blame?’

KM: can you work through feelings such as guilt…inadequacy

G: I’m better at doing that

KM: (reads as G points to each word) guilt shame and blame

G: I’m still still sometimes…hold onto that a little bit (places fist to cover lips)

KM: I sense that that’s not just to do with…the aphasia (looks to G for verification)

G: Mm (strokes ear across face)

KM: That that’s not just to do with the words being tricky

G: Yeah.

KM: There’s another aspect to it aswell (gestures both hands out from starter question) which is

G: Yeah, definitely. Which...which I struggle with, yeah. And…and I sometimes feel guilty (points to ‘guilt’) that I’ve changed (looks to KM)…and other people have to deal with that

KM: Mm. Mm

G: That’s quite a tough one sometimes

KM: It is

G: Because it’s me that’s changing

Later in the interview, a recap showed how experiencing self-forgiveness (feeling forgiven) was a gradual process:

KM: about the forgiveness part, cos although that picture didn’t help you (searched through pictures) do know how…it’s about…these two things (points to starter question: ‘do you love yourself? Do you feel OK about yourself?) Do you forgive yourself? (smiles)

G: yeah (moves jaw from side to side)…I’m getting there

KM: mm

G: definitely getting there…but I still

KM: do you feel forgiven? S’pose that’s another way of putting it

G: yeah

KM: which is…you’re very accurate about that

G: yeah

KM: cos you you say you’re getting there

G: I’m getting there. I’m definitely getting there

Freedom was found in forgiving herself and not demanding that others understood, releasing them from the equation. Mrs. Green recognised the need to act on freedom. She adopted the metaphor of the open cage offering a bird freedom, incorporating coming to terms with her fear of the unknown.

G: we need a painting of a cage. (smiles, with very wide eyes). That’s a really good one…actually…a cage with the door open…it’s like a bird…bird cage

Having felt most vulnerable post-TBI, the opposite of ‘freedom’ was ‘safety’. Now, the opposite of ‘freedom’ had become ‘holding on’ rather than letting go. In finding freedom, she was progressing into the unknown, a term she drew from HIGH to represent transcendence. This progress was for her an aspect of faith (hope), and it meant finding a sense of freedom within herself rather than seeking help from others.

3.3.5. Next Steps

The Next Steps were not just alone, but with others and regarding relationships, including forgiveness. Her goals concerned being helped to come to terms with her experiences and helping others. The hard process of ‘letting go’ had to be done alone, and any help needed to be neutral as those who were too closely involved emotionally could not help. Letting go of reliance on them was necessary, as they had their own hurts to deal with. Mrs. Green recognised she had been very alone in her recovery. She was now strong enough to be able to approach other relatively neutral friends for help to work through the hurts. They would allow her freedom in a non-judgmental relationship, whereas she perceived that nearest and dearest may have been struggling to forgive. She emphasized the power of the spoken word in sharing and change, and how the aphasia undermined that process. A key part of progress was letting go of the prior sense of self:

G: because I…for me…I have to really let go of the old me actually…rather than stay connected. That’s really important for me

Mrs. Green was uneasy about considering a chaplaincy referral, which she associated with her sense of alienation from mainstream religion. She conveyed that although she scored highest in the DEEP dimension, nevertheless this was her primary focus as it was pivotal for all other aspects to develop.

Reconciliation was not a term she used, and was not included by the researcher, who adopted Mrs. Green’s terms instead. Reconciliation to altered self and to others was encapsulated by Mrs. Green as ‘Freedom’. This meant being unconstrained by her original grief at change in her sense of self, and no longer defined by the limitations of changed relationships with others, being released from responsibility for their grief. The process of reconciliation was mediated by her self-forgiveness and forgiveness of others, which felt like a gradual release (‘letting go’) as her awareness and experiences realigned.

Coming to terms with her experiences facilitated helping others in similar situations, which she also found cathartic, bringing some positivity from a bad experience, giving new meaning and purpose to her altered self.

3.3.6. Disambiguating Belief, Faith and Religion

There was a final discussion about aspects mentioned earlier (see HIGH,

Section 3.3.3), distinguishing between Belief, Faith and Religion. Mrs. Green had been comfortable with definitions using key word options within WELLHEAD. She confirmed that Belief was concerned with the head, mind, information and truth. She added ‘

I always associate this with (places finger on word ‘BELIEF’ raises eyebrows and smiles)…um…believing in something else (smiles and turns to KM). Belief also meant being ‘

more…realistic’.’

After discussion, she confirmed that Faith concerned the heart, hope, emotions and trust. Belief, Faith and Religion were separate concepts for her.

After further discussion, Religion was encapsulated by the words: social group, practice, action and system. Mrs. Green was comfortable to use the word ‘tradition’ to mean the things she did regularly rather than overtly religious activity. She felt that, since the TBI, she had moved even further away from organised religion. Even though her family were practising Christians, and had an influence on her, and welcomed her into their religious life, she had never felt it was true for her. She was nevertheless drawn to the idea of spiritual retreats:

G: and I that that’s…more (points back to ‘spiritual retreats’) I don’t know…I feel that with religion it’s something else (makes expansive gesture grasping from page, up and landing on fingertips to side of page) that you’re looking to, whereas with this (points back to ‘spiritual retreats’) it’s more within (pulls face and places hand on heart)

Her re-conceptualisation of Religion was especially personalised, as recapped below:

KM: (turns to Religion word board) and the Religion part which…seems to be more to do with (looks up) tapping into…things that might be available to help you… move down those steps into the ‘otherness’ (gestures fingers of hand moving downwards in the air)

G: yeah

KM: is that right?

G: (nods) mm yeah (looks at KM intently)

KM: (raises hands into sculpting gesture slightly to one side) it’s not like formal religion

G: yeah

KM: but it’s a system to help you…move…beyond

G: yeah…yeah t…that’s a good explanation (gestures with thumb up sideways towards KM)

KM: OK

G: less of a

KM: less of a traditional label on it (gestures inverted commas in the air)

G: yeah (nods)

KM: but but still…(gestures a circular turning mechanism with two hands) a social system that other people might use

G: yeah

KM: that helps you get…(gestures hands moving forward)

G: move forward

KM: beyond

G: yeah… definitely

3.4. Synthesis of Analysis

The SHALOM findings (

Section 3.1) indicated that though mainstream Religion was not important for Mrs. Green, Spirituality was. Throughout the interview, she chose to avoid terms she perceived to have religious connotations, choosing ‘Hope’ rather than Faith, and ‘Information and Truth’ rather than Belief. The theme of finding Calm could be aligned with ‘Peace’, but Mrs. Green did not adopt the latter which can carry transactional and religious connotations, whereas the word calm references a state of being. Calm was a state originally found in the environment by the sea. As the interview progressed, she shared how this state could now be sought out in the absence of that original environment, for example through imagery and meditation. The term ‘forgiveness’ was not fully adopted from the key words by Mrs. Green, likely due to its religious overtones. She preferred speaking of being ‘OK with self’ ‘OK with others’ and ‘Letting go’. Instead of reconciliation, she spoke of freedom through letting go (see

Section 3.3.5) and this had two main senses for her. Firstly, freedom was found via a new sense of being part of something much greater, beyond self, where she had greater Calm than before, within the unknown. Secondly, freedom concerned transformation of relationships (with self and others), brought about through forgiveness (letting go), to move forward towards greater acceptance, away from previous expectations.

She did not speak directly of blame for the TBI, and no compensation claim was made against her employer although it was a workplace accident. She carried with her a sense of self blame which she identified as guilt (see

Section 3.3.4) for the way her life had changed irretrievably in relationship terms. Any trauma such as TBI is likely to have a significant life impact, but the aphasia took a toll on communication so that her feelings were hard to express verbally. Moreover, the impairment to thinking in words and ‘self-talk’ (internal rationalisation) made the process of adjustment even more challenging.

The processes that came to light during the WELLHEAD interview are summarised below in

Figure 1, showing that there was a progression as ideas developed through the dimensions in sequence. This progression reflected the dialogue in WELLHEAD, but also comprised Mrs. Green’s own rationalisation of her spirituality as expressed during the interview. The progression through the WELLHEAD dimensions did appear congruent with an increasing level of spiritual challenge for Mrs. Green in successive dimensions: building from more straightforward aspects in WIDE, through to more deep-rooted and emotionally charged aspects in DEEP. Notably, ‘finding freedom’ and ‘letting go’ (forgiveness) were key processes that drew on the experience in other dimensions.

Mrs. Green’s experience of these processes led naturally into setting the Next Steps at the end of WELLHEAD.

Finally, the researcher reflected on the linguistic complexity of the terms used by Mrs. Green to encapsulate spiritual processes. Her choice of ‘Calm’ referring to a state of mind (noun or adjective) is relatively simple semantically and syntactically, and she chose this term rather than ‘Peace’ which has wider connotations, as already mentioned. ‘Peace’ also has greater linguistic and conceptual complexity as it can refer to the outcome of negotiation (a transaction with an underlying argument structure) or freedom from war or from internal discord, and so on. Similarly, Mrs. Green chose to recast forgiveness as ‘letting go’ (where the verb has a single argument structure as in ‘I let go’). ‘Forgiving’ on the other hand is a verb that has an underlying three-argument structure, as in ‘I forgive you for your bad action’, subsuming ‘You did a bad action to me’. The word ‘forgiveness’ is derived from the verb and, additionally can be used bidirectionally, in the sense that forgiveness can be offered and received. Finally, forgiveness may also be used of Person A at time A, forgiving the Person A at time B, rather than forgiving Person B. ‘Forgiveness’ is therefore complex linguistically and conceptually. Mrs. Green tended to talk of loving self and loving others (two argument structures) as additional components of the process of forgiveness, keeping her language structure simple. Without wanting to overplay these thoughts on the linguistic and conceptual complexity of ‘forgiveness’ as a term, it is possible that her choices may have reflected preference for linguistic simplicity in aphasia. They may also have reflected how Mrs. Green’s own spirituality had been constructed and may have preceded her aphasia.

Mrs. Green’s SLT assessment using the A-FROM (see

Table 3 and

Section 2.3) had shown a lower score in the personal domain than the others. This aligned with her perception that she hoped for more progress in the DEEP dimension of WELLHEAD, to enable change in other dimensions of her spirituality (see

Section 3.3.5). This was also borne out in the dissonance shown in SHALOM in the Personal domain (where her Ideal score was 4.8 but her Lived Experience was only 3.6, see

Table 4 and

Section 3.1). This showed a dissatisfaction with personal aspects of her spirituality. The other domain showing dissonance in SHALOM was the Transcendental one. A comparison may be made with her WELLHEAD scores and commentary (see

Section 3.2 and

Table 5), where she confirmed that the HIGH dimension was at an early stage of development (scoring 6, ‘

searching for something beyond’) and was part of her personal story as shown the LONG dimension (scoring 6, ‘

Still feels like early days’). She appeared to be using the WELLHEAD scores to indicate the degree of insight (strength of ‘

mindset’) she had in each dimension, couched here in terms of leaving the cage:

G: yeah good one (smiles), um…(serious face again) and there’s reasons for that isn’t there…not feeling like you can…go out the door…because it feels safer in the cage (gestures towards self, and looks to KM)

KM: (nods)

G: and it’s not knowing what’s outside (gestures up and over an imaginary wall away from self)

KM: that fits with your idea of ‘unknown’ doesn’t it

G: yeah..yeah so that’s…yeah that’s an interesting one…but also then as I feel like I’m getting…better

KM: mm

G: or stronger…or my mindset…is maybe…um developing (gestures hand moving forwards)

KM: mm

G: then I feel better about…(clears throat) moving forward….with it

In the transcendental domain of SHALOM, her Ideal score of 3 and Lived Experience score of 1.8 were the lowest of all the domains (

Table 4). These aligned with her WELLHEAD commentary that her family had a strong religious and spiritual affiliation, making her guilty that it had no direct meaning for her, a disconnect compounded by their struggle to come to terms with what has happened to her. The interpretation of scores was tentative, but it also appeared that the relatively high SHALOM scores in the Communal and Environmental domains were matched in her WELLHEAD commentary by the recognition in WIDE that the environment was helping in finding Calm, and that she was becoming more connected with others again.

The scores on SHALOM shown in

Table 4 may be compared tentatively with those available in the literature for other populations, though no data are available for TBI or aphasia.

Fisher (

2010) drew together findings from multiple studies using SHALOM in educational, healthcare business and community contexts, (though excluding healthcare patients).

Fisher (

2016) reviewed further, more recent studies, in each case reporting Spiritual Wellbeing (mean Lived Experience) rather than Life Orientation (mean Ideal for wellbeing). Compared with the means from the studies that included patients (cancer and renal), Mrs. Green tended to have higher scores in all but the transcendental domain, where she was lower. Compared in a cursory way with the studies overall, her score of 3.6 in the Personal domain was in the lower range, 4.4 in the Communal domain was high (though her ideal score of 5 was very high), 3.2 in the Environmental domain was unremarkable and 1.8 in the Transcendental domain was low.

3.5. Co-Constructed Feedback on the Dialogue

Mrs. Green’s feedback concerning WELLHEAD and SHALOM was analysed in the context of the feedback interview transcripts of the entire case series (as the first phase of thematic analysis in NVivo) concerning the three major themes of accessibility, acceptability and impact. Her feedback is reported in more detail here as part of her narrative. Additional reflection was informed by the subsequent in-depth analysis of her WELLHEAD interview as reported above, and her feedback during follow-up.

3.5.1. Accessibility

It might be assumed that Mrs. Green’s ‘mild’ aphasia would bring little need for modified resources to improve communication access, especially given her return to work and discharge from SLT. However, the thematic analysis showed she valued support for exploring the abstract and complex topic of spirituality. She used the WELLHEAD toolkit in every aspect (pictures, words and starter questions) for supporting both conversation and thought processes.

Mrs. Green welcomed the modified completion of SHALOM. She was supported by reading aloud the instructions with her, then recapping them, and then covering up all below the line in question to help her concentrate. The instructions were also recapped part-way through the questionnaire when she appeared to lose focus. The researcher also read aloud the questionnaire phrases as Mrs. Green read them, to reduce linguistic processing load and allow her to consider her responses. The SHALOM instructions encourage participants to ‘record your first thoughts’ rather than spending too much time on any one item. However, she was also encouraged by the researcher to review her responses. This ensured she was comfortable with her answers and avoided any misunderstanding arising from aphasia. She conveyed that these strategies had been helpful.

Concerning WELLHEAD, in her feedback interview, Mrs. Green confirmed that she found both the pictures and the words helpful, ‘I thought they were really good—the pictures were helpful actually’. Within the DEEP dimension, she found pictures more accessible than words as a starting point, and then progressed to choosing words and starter questions which were emotionally loaded compared with other dimensions. For other sections, she sometimes opted for words or chose starter questions herself, showing that they presented no barrier. Sometimes, the pictures better facilitated her ongoing thoughts.

During the WELLHEAD interview, Mrs. Green frequently placed her finger on a selected item from the toolkit (often a picture or single word) and kept it there during the ongoing interaction. This gesture demonstrated ‘taking ownership’ of the resources and their content. It confirmed that she was using them to ‘keep her place’: a form of scaffolding both for thought processes and for keeping the thread of the conversation.

3.5.2. Acceptability

Mrs. Green confirmed during the interview that she was comfortable with the definition of spirituality as ‘meaning and purpose’. Her body language showed that she was at ease with the resources, and her feedback interview and questionnaire showed that she found them appropriate for her viewpoint. The incorporation of facial expression and gesture in the transcripts enabled identification of aspects such as emotional reaction to certain topics. For example, it emerged that some of Mrs. Green’s laughter was covering unease at emotionally charged topics, particularly where vocabulary or pictures tended to be associated with mainstream religion. There, the laughter was accompanied by defensive gestures or direction of gaze. At other times, there was shared laughter with mutual gaze and animation, indicative of Mrs. Green feeling ‘well heard’. The researcher used humour to build rapport where she perceived there to be more of a challenge (the later dimensions of HIGH and DEEP), which encouraged open sharing from Mrs. Green.

During the interview, she acknowledged that Christianity was an influence in her life (though her SHALOM score indicated that religion was of little importance to her now, see

Table 3). Her parents were practicing Christians, but she tended not to take part in religious activities because they did not feel authentic. She gained a new and helpful insight during the interview process when she realised that spirituality, distinct from religion, could be valid. She had explained in WIDE that although she felt welcomed in her parents’ church, and not excluded by members of her family who were practising Christians, she had a sense of not connecting with Christianity, feeling distanced by formal religion. Viewing religion as looking outwards to something, and spirituality as more within (see

Section 3.3.6), she nevertheless found the WELLHEAD format acceptable. It allowed her to express her own viewpoints. She often left her finger on chosen words or pictures as if claiming them as her own (see above), and this was extended into her request for copies of the pictures in the feedback phase.

3.5.3. Impact

The detailed account of spirituality achieved through WELLHEAD revealed aspects of meaning and purpose through reflections on past and present life. Through the conversation process, Mrs. Green also appeared to be discovering and validating new aspects to her spirituality (e.g., the link of her concept of the unknown to her freedom). Using shared reflections, she was enabled to conceive of the next steps in a practical way. During the feedback interview, she shared that the best part was being prompted to think about things from her subconscious mind, making them part of conscious change:

G: I think… perhaps um…made me think a bit more…maybe... cos actually…stuff that I maybe hadn’t …thought about that (frowns)

KM: …Mm…what

G: thinking about a bit more might help (laughs)

Some of the thoughts had significant emotional resonance, particularly her aloneness, and the relational aspects of the DEEP dimension. Discussing those thoughts, though cathartic, was identified as the ‘worst part’ because of feeling the pain:

G: (laughs) um probably when I had…when I started (places finger chest then on lips) to think about guilt (hand gesture of grasping and pulling individual things up)

KM: (whispered) yes (writes on questionnaire form)

G: and that particular bit when…understandably (looks sad, gestures out from heart) just brings back things doesn’t it…makes you think

KM: and…is that a bit near the bone?

G: yeah (nervous laugh, bites lip)

A key aspect of the benefit perceived was being enabled to put those thoughts and feelings into words; challenging in the context of aphasia but part of what she hoped to do as a result of the interview:

G: I think …that when we said about finding the…neutral person to…

KM: (nods) yeah (writes on questionnaire form)

G: maybe just explore

KM: (nods)

G: some of those thoughts that… maybe I haven’t said out loud before

The resources seemed to be moving Mrs. Green forward in her thinking and insight as the interview progressed, with the birdcage picture she described (see

Section 3.3.4) being an addition to the existing resources. Following her interview, such a picture was commissioned and approved by the steering group and by her: ‘

I love that’.

Mrs. Green attended both optional feedback sessions where the general findings of the feasibility study were shared with participants with aphasia. At the end of the second meeting, she approached the researcher and requested emailed copies of two of the WELLHEAD pictures that had meant the most to her: ‘Journey down a lane’ (see LONG (

Section 3.3.2)) and ‘Steps to the sea’ (see DEEP (

Section 3.3.4)). (Details are available on request). These pictures had remained in her visual memory and helped her since the interview. She conveyed afterwards, by email, that these had played a significant part in her ongoing reflections and the process of coming to terms with her aphasia:

‘Thank you for your email, and the attachments. They are very personal to me, and something that were key in what I felt like was perhaps a turning point in my mind set regarding my aphasia’.

Of WELLHEAD overall, she conveyed off camera at the end of her interview, ‘You’re doing a good job here’, and in her final feedback email ‘It helped me have a focus in difficult journeys’.

3.5.4. Reflections on Co-Construction

The assumption that terms have the same meaning for the participant and the researcher was based on the aphasia assessments and prior knowledge of Mrs. Green. These indicated that input processing was mildly impaired, and concepts were largely intact, with abstract rare and lengthy language being less accessible, and strategies being helpful for clarification and facilitation of communication and thought (see

Section 2.3). In cases of word-finding difficulty, pictures and the WELLHEAD word boards were used, with questions requiring a Yes/No answer to narrow down the intended meaning and recap, to minimise pre-empting the message. Nuances concerning language meaning relate to personal experience and ideology, so there is always a need to establish joint understanding of terms and to take context into account, irrespective of the presence of aphasia.

The impact of the interactive process on the researcher is also acknowledged. The researcher was no longer living with aphasia, having recovered well from her personal experience of having mild aphasia, and having increased empathy for others with aphasia in consequence. There was a sense of privilege at sharing the narrative and, though not shared with Mrs. Green in these terms, felt like ‘standing on holy ground’, or walking alongside on a spiritual journey. The researcher responded in a specific way to this process by writing a poem (

Appendix A. In response to Mrs. Green’s email endorsement of the value of WELLHEAD, this was shared with her, rather than the others attending, at the feedback session). In common with Mrs. Green was a desire to help others through her experience (see

Section 3.3.5). There was some catharsis in undertaking and documenting the study, with delight being experienced at offering deep listening and enabling another in a mutually unconditional way.

4. Discussion

In drawing together the findings, it is important to establish credibility and dependability of the narrative. Credibility was enhanced by using a systematic method of analysis and verification. Dependability (consistency) of the thematic analysis and confirmability (groundedness of the interpretations in the data) was ensured by independent verification. Additionally, member checking was used extensively with Mrs. Green via optimal communication methods, to ensure the narrative findings were consistent with her experience. She took part in two aphasia-friendly reviews of the overall findings at feedback groups, and she welcomed the opportunity to provide more extended feedback volunteered via email, including endorsing the content of the abstract, graphical abstract and

Figure 1 which form part of this paper.

Internal consistency was prioritised using triangulation of the interview data via additional field notes, the use of quantitative measures, and the data generated from feeding back those findings to participants. The thematic analysis evolved as those aspects were incorporated, and it included researcher reflections and participant comments to ensure that themes were accurate representations of the data. Crucially, the narrative was told in Mrs. Green’s terms: using her chosen words and reference points. In interpreting the significance of what was shared, the researcher also brought her own perspective, but established that the presence of different spiritual backgrounds did not prevent Mrs. Green from sharing her story in her own way. Determining goals through self-selected terms gave personal ownership of those next steps, making them more likely to be incorporated in real life.

Mrs. Green’s motivation for consenting to be part of the research and the feedback sessions was not made explicit, potentially influencing the findings. There are three possible accounts. One possible motivation was that she expected the research to help others with aphasia, which was consistent with the theme of ‘helping others’ from the interpretive analysis. She shared, just prior to the interview session, that she wanted to promote ‘educating others about aphasia’ via a new-found campaigning aphasia group. Secondly, she had previously conveyed that she gained positive benefit from the SLT therapeutic relationship, giving glowing feedback at the end of her episode of care. It may be that she wanted to please the clinician-researcher in return, by taking part and providing certain responses; but this is very unlikely to be her true motivation, since she readily volunteered positive feedback beyond what was designed into the study feedback interview. She was also observed taking ownership of the resources by keeping her finger on selected pictures and incorporating them into her own gestures. There was a sense of mutual trust and respect, strengthened by the researcher’s experience of aphasia, which gave weight to the revelations co-constructed through the research process. Thirdly, her motivation may have been because she sensed a need to explore spirituality as defined in the research information leaflet as: ‘exploring the deeper things in life in terms of meaning and purpose’, echoed in her recognition of the personal domain being less well developed within her adjustment to aphasia.

There are limitations to the study due to its nature as a single case. Both aphasia and TBI involve a wide-ranging spectrum of impairments, which makes any generalisation from the findings cautious. It is beyond the scope of the study to determine how this co-construction of forgiveness and freedom, in language adopted by a person with aphasia, aligns with concepts of forgiveness and reconciliation in other contexts. This paper seeks to set out a narrative rather than to make comparisons, offering measures to anchor it into further work into aphasia and TBI. Nevertheless, the detailed accounts of participant characteristics and spiritual phenomena ensure the potential for comparisons with existing studies and future work. Understanding experiences of spiritual adjustment processes offers first steps in meeting the spiritual needs of people with aphasia and TBI.

The measurements gathered using WELLHEAD supplemented the qualitative analysis, but they did not stand alone, being part of a prototype. The measures will form part of a larger data set concerning aphasia (including findings from the feasibility study being reported by

Mumby and Roddam (

2019)). Preliminary comparisons of SHALOM and WELLHEAD indicated that they were mutually compatible (see

Section 3.4), and that the WELLHEAD interview provided rich data about personal perceptions and the processes involved in spirituality; not accessible from measurements alone. Moreover, WELLHEAD was acting as a catalyst for spiritual change, as shown in its perceived impact. It supplemented what could be achieved through questionnaires alone. It facilitated Mrs. Green’s development of the Next Steps, using her chosen words and preferences, building a progression in spiritual terms as the interview considered successive dimensions (see

Section 3.4 and

Figure 1). The processes may have relevance for others undergoing spiritual change: part of the adjustment to trauma. Dissonance is an indication of potential internal conflict where life does not match up to ideals. Given that Mrs. Green’s narrative from WELLHEAD was consistent with her dissonance, such measures may be valuable in future studies of adjustment processes.

Determining whether the goal-setting in WELLHEAD was reflected in subsequent changes in spirituality was beyond the scope of this study, which was not designed to measure intervention. Further intervention studies are required to investigate whether the exploration of issues and the goals set have an impact on future spiritual health, including how scores on SHALOM and WELLHEAD change over time. Nevertheless, there was clear impact from participating in WELLHEAD shown in the narrative, both during the interview and afterwards. This showed scope for future work to investigate change processes with comparative measures.

The narrative focused on someone non-religious and though such accounts are rarer in the literature than those taken in a specific religious context, they exemplify the validity of spirituality for those who do not consider themselves to be religious. There was clear distinction between spirituality and religion, belief and faith, which is important to consider in future studies to avoid overgeneralisations from assumptions about terminology.

The findings were in keeping with previous work from

Mumby and Whitworth (

2013), showing adjustment to aphasia as a gradual (long term) process: from fragmentation of life towards a sense of wholeness. The narrative was also congruent with literature about aphasia profoundly affecting relationships and participation. It showed the sense of significant isolation and aloneness, and difficulty connecting in one-to-one or large gatherings, consistent with reduced participation, the spiritual aspects of which have not been systematically examined before. The findings were also in keeping with goals reported from people with aphasia (

Worrall et al. 2011) for autonomy, dignity and respect, expressing opinions, and helping others.

WELLHEAD provided a structured framework for spiritual storytelling in keeping with previous work in post-stroke aphasia by Arnesveen, Bronken, Kirkevold, Martinson and Kvigne (

Bronken et al. 2012), who used facilitated co-construction as storytelling in relation to psychosocial wellbeing. They highlighted ‘the need to talk’ and the importance of providing ‘the opportunity to tell’, which is consistent with the experience of Mrs. Green. In common with this study, the profound impact and trauma of acquired aphasia was addressed in the narrative process, a process catalysed by WELLHEAD in the current study.

Most of the previous work in aphasia and TBI does not use a spiritual framework. A spiritual approach to aphasia is largely absent from multifactorial rehabilitation practice. It does not feature in respected models from aphasiology concerning recovery processes (

Code 2001). If, as in Mrs. Green’s case, spiritual processes can be traced in all dimensions of life (WIDE, LONG, HIGH and DEEP), then it is crucial to integrate spirituality into rehabilitation models, in keeping with conclusions from (

Carey and Mathisen 2018, p. 259) about a holistic ‘bio-psycho-social-spiritual model’ of healthcare.

The narrative was consistent with previous work on ‘sense of self’ being important for adjustment in aphasia; additionally, it used a spiritual lens to explore previously uncharted aspects concerned with love, acceptance and forgiveness. Carroll and Coetzer’s (

Carroll and Coetzer 2011) exploration of identity grief and self-awareness after TBI found identity change after TBI. They stressed the importance of considering the subjective experience of TBI as part of rehabilitation and to inform psychological therapy. In the light of the current narrative, spiritual factors may also need to be considered as part of identity, requiring spiritual support.

Further work will report the case series findings from the WELLHEAD feasibility study, giving scope to compare people with aphasia with different aetiologies and religious and social backgrounds. The important theme of forgiveness does not feature in previous accounts of acquired aphasia, perhaps because spiritual questions were not being asked. If indeed forgiveness of self and others is an integral and instrumental process in recovery, then further exploration of the applicability of this insight would inform aphasia intervention and support.