Abstract

This article reviews the historical sources and archeological finds concerning the cult in Shiloh in the Roman-Byzantine period. The study examines the transition to the Byzantine period and attempts to follow the conversion to Christianity in the region, with regard to both the holy site and the populace. Furthermore, the study explores the reasons for Shiloh’s sacred status as perceived by the Christians, who brought about the establishment of four churches on the site. An interesting development is the shift from identifying Shiloh’s location at Shiloh with Nabi Samwil in the Crusader period. A main point that emerges is the formation of a holy place. In the Early Roman period, Shiloh appears to have been recognized by the Jews, albeit with no evidence of any religious rituals, while in the Byzantine period, the place was recognized as a sacred place of worship with clear official backing, perhaps versus the Samaritans. Moreover, Shiloh was part of an overall process whereby Christian sites located in Samaria and mentioned mainly in the Old Testament were sanctified in order to influence the Christian image of this area.

1. Introduction

Many studies have been devoted to reviewing the early periods of the site at Shiloh, located 30 km north of Jerusalem, from the Bronze to the Hellenistic period. This is reflected in publications of the Danish team led by Hans Kjaer, which conducted excavations at Shiloh in the 1920s and 1930s, and in the final report published by Buhl and Holm-Nielsen (1969).1 The second part of the report was published in 1985 (Andersen 1985), containing the later findings. In the 1980s another excavation was carried out, headed by Israel Finkelstein, and most of the report was devoted to earlier periods (Finkelstein et al. 1993); namely, mainly from the Biblical period2 to the Early Roman period (see also Finkelstein 1993). The exact location of the Tabernacle complex at Shiloh has occupied many researchers, and this issue remains in dispute. The current article does not intend to discuss this conflict, but rather to illuminate the later eras of the site at Shiloh, the Roman-Byzantine period, which only few have dealt with (Reeg 1989, pp. 603–5; Tsafrir et al. 1994, p. 232). Examination of the historical, archeological, and literary sources on these eras might illuminate several main points related to the site, such as the preservation of traditions regarding the site and their diverse presentations in the various faiths.

The main body of the current article concerns the fields of historical-geography and archeology; however, related fields such as philology and rabbinical literature will also be discussed. First, the relevant historical sources for each period shall be examined; then, these will be cross-referenced with the most recent archeological studies; and in the discussion, the meaning of the findings will be elucidated. In the present researchers’ opinion, the history of the settlement and the identity of its inhabitants have an impact on the local tradition, and all these factors might complement each other and produce a more meaningful picture. It is proposed that the site of the Tabernacle at Shiloh was recognized as a ‘Holy site’ for part of this period, and that its development should be examined in light of the development of other holy places in the Holy Land (see below).

The continuous sacredness of a site between historical periods and even between different faiths is a well-known phenomenon. As described by Ora Limor:

This is what happened in significant places such as Jerusalem, which maintained its sacred status among Christians and Muslims, as well as in less significant places such as the point where the Israelites crossed the Jordan (for other examples see Klein 1933). This is also what occurred in Shiloh. The special significance of the site in the Biblical period as the location of the Tabernacle perpetuated the site’s sacred status in later generations as well, when it no longer housed the Ark of the Covenant and the Tabernacle moved on to another location.It is a well-known phenomenon, that places of pilgrimage maintain their sacred status even after shifts in the owners’ faith. In Jerusalem, pagan holy sites became Jewish holy sites, which subsequently became sites holy to Christianity and Islam. Unlike other places, where as a result of the changing religious hegemony a sacred tradition was replaced by a new tradition, Christianity did not dismiss the previous traditions, rather it preserved them while adding its own interpretation.(Limor 1998a, p. 9)

2. Shiloh in the Roman Period—‘The Scent of the Incense from between Its Walls’

Indications of the site’s magnificent historical past in the Roman period are evident in rabbinical sources. However, these sources and the information contained in them are very limited, and non-sequential. It is clear that although the Tabernacle was stationed at several stops, Shiloh became that most identified. When the sages are interested in showing the difference between the Jerusalem Temple and the Tabernacle, they mention Shiloh as a prototype of the Tabernacle: ‘Shiloh differed from Jerusalem only in that at Shiloh they could consume the Lesser Holy Things and the Second Tithe anywhere within sight [of Shiloh]; but at Jerusalem only within the city wall’ (m. Meg. 1:11).3 This is because most of the biblical stories involving the Tabernacle, after the Israelites entered the Land of Israel, occurred at Shiloh, such as the division of the land among the tribes, the decision concerning the battle against the tribe of Benjamin, and the Samuel stories.

The comparison between the Temple and the Tabernacle at Shiloh is also evident with regard to the incense. When the Babylonian Talmud seeks to describe the strong scent of the incense at the Temple in Jerusalem, a hyperbole tradition is cited that longingly hearkens back to the scent of the incense at the Tabernacle in Shiloh: ‘R. Hiyya b. Abin said in the name of R. Joshua b. Karhah: An old man told me: Once I walked towards Shiloh and I could smell the odor of the incense [coming] from its walls’ (b. Yom. 39b). R. Yehoshua ben Korha was a fourth generation Tanna who enjoyed a long life (Margalioth 1995, p. 189).4 According to his report in the name of one of the elders, it appears that it was still possible to smell the scent of the incense absorbed in Shiloh in bygone days. The homily presented is mentioned in the Talmudic issue concerning the strong scent of the incense at the Temple in Jerusalem: ‘R. Jose b. Diglai said: My father had goats on the mountains of Mikwar and they used to sneeze because of the odor of the incense’ (b. Yom. 39b), but the conceptual intention of the exegetist appears to be directed at noting the preserved sacredness of the Tabernacle’s site, where the scent shows that it remained holy despite the lengthy time that had elapsed since its destruction. We know that pleasant scents that emanate from holy sites and from the bodies of saints were an indication that these are spiritual domains (Shemesh 2017, pp. 117–29).

This statement may attest to a conception of innate holiness, as the issue of the sacredness retained by a ruined site appears repeatedly, for instance in the Midrash: ‘Look! He stands past our wall. This is the Western Wall of the Temple. For the Holy blessed be He swore that it would never be destroyed’ (Song of Songs Rabbah 2:9). Moreover, it seems that the exegetist is interested in setting a feeling or standard for the strong scent of the incense in Jerusalem by providing a concrete example from a secondary site. Namely, if the scent of the incense remained in Shiloh after such a long time, then in the Temple, which was a larger ritual site, the scent of the incense was even stronger. Although the source is Babylonian, it may have preserved a concrete tradition concerning a certain location at Shiloh, as we shall see below that Jews remained there after the destruction of the Temple as well.

Other historical sources indicate that Jews continued to live at Shiloh until the Bar Kochba revolt (132–135 AD). Josephus Flavius (Antiq. V 68) wrote that Shiloh is west of Gilgal. The Babylonian Talmud mentions a Jewish sage from Shiloh named Shimon: ‘R. Shim’on the Shilonite lectured: When the wicked Nebuchadnezzar cast Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah into the fiery furnace…’ (b. Pes. 118a). Nevertheless, we have no firm information on Shimon’s activity in the region and to what generation of Tannaim he belonged. Further on, the Tanna R. Natan contradicts Shimon in that source, supporting the assumption that Shimon was a Tanna. Edward Robinson used the inflection Shiloh-Shiloni (שילה-שילוני) to prove the preservation of the name Seilun in Shiloh (Robinson and Smith 1856, p. 87; Di Segni 2012a, p. 210). Some researchers have attempted to argue (Luria 1947, p. 172; Gevaryahu 1968, p. 158) that two of R. Yehuda Hanassi’s disciples lived in Shiloh, based on the sentence in the Jerusalem Talmud: ‘Shmuel and Ilin (אילין) from the household of Shila would greet the Nassi every day’ (y. Taan. 4b), but this opinion is based on an error, as the actual meaning of the text is that Shmuel and the members [=ilin] of the household of Shila would greet the Nassi every day, and this is undoubtedly a place in Babylon (Herman 2005, p. 156; 2012, pp. 89–90).

An indirect testimony to the Jewish familiarity with the region surrounding Shiloh appears in the Babylonian Talmud: “R. Nathan said: From Gareb to Shiloh is a distance of three mils, and the smoke of the altar and that of Micah’s image intermingled” (b. Sanh 103b). This quotation tells us that in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, the Jewish sages were able to identify not only the location of Shiloh, but also the location of Micah’s house, although this place was not mentioned from the time of the Bible to the late Roman period (Aharonovich et al. 2016, pp. 31–33). Gareb is identified as either Khirbet al Auf (2.2 km west of Seilun) or Khirbet Ghurabeh (4.8 km west of Seilun), although the latter seems more reasonable due to the late Roman finds there (Aharonovich et al. 2016, pp. 19, 31).5

The final evidence of a Jewish settlement at Shiloh comes from letters nos. 24 and 92 found by Father Roland de Vaux in the Murba’at cave in the Judea desert, in the 1950s (Benoit et al. 1961, p. 222; Sar-Avi 2002, pp. 124–25). A large number of scrolls and documents from the time of the First Temple to the Early Muslim period were found in the Murba’at cave. Most of the documents were brought there by refugees at the end of the Bar Kochba revolt. It appears that during the Bar Kochba revolt some Jewish resident of Shiloh, moved from the area of Ephraim to that of Judea and even leased land from Bar Kochba’s administrator, Hillel ben Garis. The mention of a Jewish resident in Shiloh in this period is not surprising and in the Murba’at papyri we find indications of Jews in the entire area of northern Judea, for example in Gofna, Galuda, Aqraba, and Rimmon (Sar-Avi 2002, pp. 24–127). In the time of the Second Temple until the Bar Kochba revolt, the area of northern Judea was populated by Jewish agricultural settlements that belonged to regional administrative centers,6 and Shiloh was affiliated with the capital of the toparchy, Aqraba (Stern 1968; Zissu 2001, pp. 27–28).

Eusebius, the father of church history, mentioned Shiloh in his Onomasticon:

The Onomasticon was compiled in the eighth decade of the 3rd century AD and belongs in fact to the late Roman period (Eusebius 2005, preface, p. XV).7 The main innovation contained in the information provided by Eusebius appears to pertain to the location of Shiloh relative to the city of Shechem.8 Furthermore, this testimony continues the biblical tradition whereby Shiloh was the place where the ark was stationed, a statement that accompanied the site’s Christian characterization. Eusebius’ testimony also contributed to the future identification of the site at Khirbet Seilun.In tribe of Ephraim. The ark remained here previously until the time of Samuel (1 Sam 4:3). It is twelve miles from Neapolis in Akrabattine. One of the sons of the Judah the Patriarch was also called Shelah (we read).(Onomasticon 156: 28. The translation from Eusebius 2005, p. 147)

Archeological evidence supporting the existence of a Jewish settlement in Shiloh in this period is contained in material finds with a distinct Jewish characterization throughout the site, such as stone implements and ritual baths (Buhl and Holm-Nielsen 1969, pp. 59–61; Finkelstein et al. 1993, pp. 62–63, 191–92; Livyatan-ben-Aryeh and Hizmi 2014, pp. 124–25; Klein 2009, pp. 181–88). We are familiar with the use of stone implements after the destruction of the Temple, as well as until the Bar Kochba revolt at many other sites (Magen 1988, p. 107). Boaz Zissu is of the opinion that the Shiloh site includes a hiding complex (Zissu 2006, p. 87) and Eitan Klein suggests that the many graves should be seen as evidence of the large size of the town in this period (Klein 2009, p. 188).

Nevertheless, we are not familiar with remnants that indicate a Jewish settlement in Shiloh after the Bar Kochba revolt, and as a rule, the population in the Samaria region was reduced after the Bar Kochba revolt (Magen 2012, p. 64). Klein has shown that after the Bar Kochba revolt, the area of Shiloh was populated by pagan inhabitants who appear to have come from Phoenicia, Syria, and Arabia (Klein 2011, pp. 321–22; 2010). Although another possibility is that the Samaritan population spread southwards to this area, it is not reasonable. No evidence has been found of Samaritan expansion south of the Shiloh river (Magen 2002). Moreover, Abu ‘al-Fath, a Samaritan historian, wrote in The Kitab al-Tarikh that the Samaritans saw Shiloh as a cursed place to which Eli the Priest had retired, establishing a rival temple to that at Mt. Gerizim, and it is hard to presume that they settled there, of all places (Abu al-Fath 1985, p. 48).

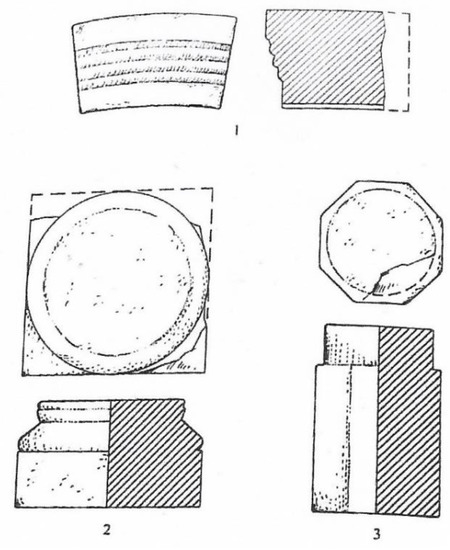

Evidence of the pagan population is the lintel above Jami’ al-Sitin (جامع الستين, see Figure 1). For a long time, various researchers (Kjaer 1930, p. 80; Luria 1947, pp. 171–75; Braslvsky 1954, p. 303; Ilan 1991, p. 251) thought that this was a lintel characteristic of synagogues in the Galilee, but Klein showed quite persuasively that this was not an original lintel intended for a building, but rather the side of a trough from a pagan burial cave that had been adapted as a lintel through secondary use (Klein 2011, pp. 172–73).9 In addition, south of the tell, evidence was found of an impressive colonnaded street (Magen and Aharonovich 2012, pp. 164–65), as well as various structures from the Late Roman period (Hizmi and Haber 2014, p. 104; Livyatan-ben-Aryeh and Hizmi 2014, pp. 125–26). A hint of pagan ritual in Shiloh is evident in an octagonal monolith altar found on the surface in the northern churches (Magen and Aharonovich 2012, pp. 200–1, Figure 2:2). Another element that may be connected to a pagan temple are the two arched stones west of the medieval mosque (Magen and Aharonovich 2012, pp. 200–1; Figure 2:1). In this regard, another hexagonal altar found in Tell er-Ras, near Nablus, should be mentioned. The altar was found on the surface near the pagan temple (Magen 2009, pp. 247–48).

Figure 1.

Part of the pagan burial cave in secondary use in Jami’ al-Sitin. (From Kjaer 1931, p. 86). This lintel is now gone. See also: http://www.iaa-archives.org.il/zoom/zoom.aspx?id=43097&folder_id=3380&type_id=&loc_id=15439.

Figure 2.

Pagan remnants in Shiloh. (From (Magen and Aharonovich 2012, p. 200). Published with the courtesy of the Staff Officer of Archaeology, Civil Administration for Judea and Samaria).

Thus, in the Late Roman period, there is no clear evidence of Jewish or pagan worship at Shiloh, but it is notable that one of the ritualistic characteristics in the Late Roman period10 was the establishment of ritual sites on the remnants of a site holy to other faiths, such as Gilgal, Ramat Mamre, and Bethlehem (Klein 2011, p. 303). This phenomenon also happens by transformation of pagan temples to churches (Saradi-Mendelovici 1990), and several similar cases are known in Palestine (Bar 2011, pp. 12–13). It is possible that Shiloh, too, was sanctified in this way, although there is no clear evidence for Shiloh’s sanctity in this period. However, although there is no clear evidence of rituals, it is at least clear that the place name was known throughout the period, and either Jews or Christians recognized the village of Shiloh as the place of the Tabernacle.

3. Shiloh in the Byzantine Period—The Ruined Altar

In contrast to the Roman period, in which there is no clear evidence of religious activity at Shiloh, in the Byzantine period there is clear evidence of Christian worship on site. Shiloh appears to have been important to Christianity from its initiation, and therefore there are various traditions connected to events and figures associated with the site.

3.1. The Historical Sources

Jerome’s translation of Eusebius from 390 AD (Newman 1997, p. 236) adds almost nothing to the Onomasticon, aside from changing the distance from Shechem from twelve to ten miles (Eusebius 2005, p. 147).11 However, in other places, Jerome relates to Shiloh differently. In letter no. 108, written in 404 AD,12 Jerome described the place of the Tabernacle as a site that contains several meaningful historical elements:

Hence, Jerome mentioned the ruined altar, but did not mention a church. Where Eusebius reported that Shiloh is the place where the ark was stationed according to the Bible, Jerome added the element of the altar, and his testimony that the altar was ruined is particularly important. Jerome seems to have hinted at Jeremiah’s prophecy, on which we will expand below: ‘But go ye now unto my place which was in Shiloh, where I set my name at the first, and see what I did to it for the wickedness of my people Israel’ (Jer. 7 12), i.e., the ruined altar is proof of the bad deeds of the Israelites and indicates the triumph of Christianity over Judaism.What shall I say of Shiloh. Its ruined altar can still be seen, and it is the place where the tribe of Benjamin foreshadowed Romulus and the rape of the Sabine women13.(Wilkinson 1977, p. 51; For the Latin source see Jerome 1912, Epistula 108, p. 322)

In a letter he sent to Marcella, a Roman Christian matron and a friend of Paula’s, circa 392 AD (Di Segni 2012a, pp. 214–15), Jerome tried to convince her to visit the Holy Land. Among his arguments he wrote:

In other words, Jerome saw Shiloh as a mark of Christianity’s triumph over Judaism. This description also shows that in the time of Jerome churches had already been built in these places.…accompanied by Christ, we shall have made our way back through Shiloh and Bethel, and those other places where churches are set up like standards to commemorate the Lord’s victories.(Jerome 1910, Epistula 46, p. 344)

In his commentary on Zephaniah 1:15–16, Jerome referred once more to the ruined altar at Shiloh but also to additional elements related to the site: ‘We hardly discern insignificant traces of ruins in cities once great. At Shiloh, where the tabernacle and the ark of covenant were, now scarcely the foundation of the altar can be seen’ (Di Segni 2012a, p. 217, note 45; for the Latin source, see Jerome 1970, p. 673). This description too supports the Christian view of their triumph over the vanquished Judaism and the Israelite iniquities that had caused this. Jerome enumerated Shiloh among the mighty cities, apparently not from a physical perspective but rather in the Jews’ religious and cultural world. Jerusalem’s ruins were seen by the Christians as evidence of the Christian triumph over Judaism, as Jerome wrote in his commentary on Isaiah 64:

This is also the place to note that Jerome mentioned the ‘ruined temple’ in his writings no less than 18 times as proof of the victory of Christianity over the Jews (Newman 1997, pp. 226–29), and the case of Shiloh appears to join these. This claim is evident from Jerome’s interpretation of Jeremiah 7:12, where he wrote:… There is no point in discussing that which is obvious, namely, that what was most precious has now become a ruin, and the temple that was famous all over the world has become the garbage dump of the new city… and the temple has become an owl’s nest(Jerome 1963, p. 626).14

The destruction of Jerusalem clearly symbolizes the ‘triumph of God’, i.e., of Christianity, over Judaism, and this is thought to be the reason that the Temple Mount was left in ruins in the Byzantine period (Limor 2014, p. 31). If so, this was true of Shiloh too, and the destruction of the Tabernacle was a prototype of the destruction of the Temple, from which the Israelites could have learned a lesson, but did not do so.He draws from the past in order to teach in the present. To those who say “this is the temple of the lord, the temple of the lord, the temple of the lord” and who delight in the splendor of this costly edifice, he recounts the historia of Shiloh where the tabernacle of god first resided. It is also written about it in the psalm: “he forsook his dwelling at Shiloh”. Just as that place was reduced to ruin and ashes so also the temple will come to ruin, since it is the adobe of similar sins. Therefore, just as Shiloh was an example of the temple, so also the temple should be an example to us, when we come to the time of this testimony: “when the son of man comes will he find faith on the earth”(Jerome 2011, p. 50).15

Shiloh appears as early as the Itineraria of the first pilgrims, and the first to mention Shiloh is Egeria, circa 384 AD. She wrote of Shiloh: ‘At the twentieth milestone from Shechem is the temple of Shiloh, now destroyed, and also in that place is the tomb of Eli the priest’ (Egeria 1981, p. 202). Therefore, as also described by Egeria, the Tabernacle (the ‘Temple’) appears in Shiloh, but instead of the ark and altar that may have been part of the Tabernacle, she mentions the grave of Eli,16 maybe under influence of the Christian rituals that developed around graves (Limor 1998a; Wilkinson 1990; Taylor 1993). Eli’s grave does not appear in the Scriptures, but he died in the Shiloh Tabernacle and was probably buried in the vicinity of the town (I Samuel 4:18). Notably, the segment on Shiloh is indeed considered a quote from Egeria, but it is not certain that these are her words. Egeria travelled under the guidance of clerics, and at each place they would read the relevant biblical text; thus, when coming to Shiloh they probably read about Eli and his sons, and if there had been a grave there the guide would clearly have identified it as Eli’s grave, as customary among tour guides to this day. Nevertheless, we know of no Christian association of Shiloh with Eli or his gravestone.

Another work that mentions Shiloh is The Lives of the Prophets (Vitae Prophetarum) that deals with the life history of 23 biblical figures. The identity of the text’s author (Hare 1985, p. 380) and its date of authorship have been the subject of lengthy debate (Wilkinson 1990; Satran 1995; Limor 1998b). The current view among the researchers follows that of Pieter van der Horst, who believes that this is a Jewish compilation from the first century AD (van der Horst 2002, p. 136) rather than that of David Satran, who thinks that it is a Christian compilation from the fourth or fifth century AD (Satran 1995, p. 118).

One of the prophets described in Vitae Prophetarum is Ahiya Hashiloni, who appears to have come from Shiloh: ‘Ahijah was from Shiloh, where the tabernacle was of old from the city of Eli… and he died and was buried near the oak of Shiloh’ (Satran 1995, p. 127). Indeed, the terebinth of Shiloh is not mentioned in the Bible, but the author seems to have been referring to Joshua 24:25, where Joshua buried the words of the covenant under the terebinth (Satran’s oak) in Shechem. Nonetheless, it is notable that in the Septuagint translation of this verse the entire incident of forming a covenant is presented as occurring in Shiloh, and hence the oak under which Ahiya was buried (Gevaryahu 1968, p. 152).

Towards the second half of the sixth century, circa 570 AD, Theodosius mentioned the location of Shiloh as situated on the way to Emmaus, on the site of Kiryat Ye’arim or Nebi Samuel: ‘From Jerusalem to Shiloh where the Ark of the Covenant of my lord used to be is eight miles. From Shiloh to Emmaus which is now called nicopolis it is nine miles’ (Wilkinson 1977, p. 65).17 Moreover, as early as the Madaba Map, dated in the same period, the sites are confused, as Shiloh appears in a completely wrong location, east of Shechem, and it is written there ‘Shiloh. And there once was the Ark’ (Avi-Yonah 1954, p. 45). From the seventh century AD, Shiloh is not mentioned in Christian sources in its original location. The meaning of this will be elucidated below.

Hence, as early as the beginning of the Byzantine period, the Christian literature contains mentions of Shiloh as the location of the Tabernacle and the altar, as well as the burial place of biblical prophets such as Ahiya Hashiloni and Eli the Priest (Jeremias 1958, pp. 42–43), which appear to preserve a Jewish tradition (van der Horst 2002). Namely, the Christian sources rely on the biblical tradition regarding the site and stress its destruction to prove the merit of Christianity, at the time considered a new faith.

3.2. The Archeological Finds

In addition to the literary documentation, there are archeological finds that support the fact that Shiloh was an important Christian center. As early as the beginning of the Byzantine period, and particularly in its subsequent years, construction in Shiloh was characterized by the establishment of religious buildings, and we know of at least four churches that were active in Shiloh.

The first dated church on the site was the early northern Church at the foot of the mound (Magen and Aharonovich 2012; Di Segni 2012a, 2012b; Figure 3 and Figure 4). The measurements of the church were 19.00 × 18.50 m., and it had a basilical design. However, the church was designed differently from similar churches, as the narthex was in the north. Moreover, the design of the west side was irregular, due to the late Roman colonnaded street mentioned above. The impression is that the architects had to fit the church to the current conditions and were not free to build it with no constraints. At the entrance to the church, an impressive inscription was found: “Lord Jesus Christ, have pity on Shiloh and its inhabitants. Amen” (Di Segni 2012a, p. 209; Figure 5). This inscription in the early church shows the connection to the biblical Shiloh and to the ancient traditions adopted by the Christian inhabitants. Another mosaic inscription at the foot of the altar mentions the names of Eutonis the Bishop and Germanus the Priest (Di Segni 2012a, p. 211).18

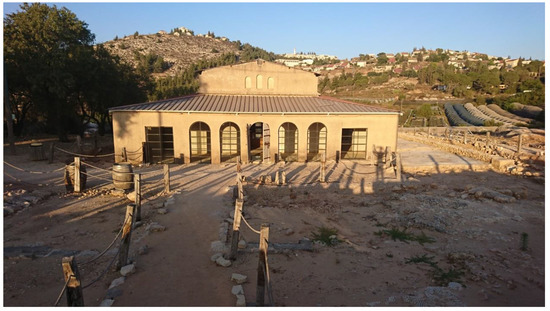

Figure 3.

The northern churches under Jami’ al-Yatim. (Photographed by the authors).

Figure 4.

The mosaics of the northern churches. The difference in the height between the two churches is evident. (Photographed by the authors).

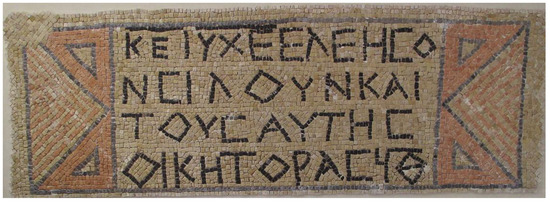

Figure 5.

The inscription at the entrance to the early northern church (From free Wikipedia).

Di Segni sets the date of establishment of this church as 386–392 AD (Di Segni 2012a, p. 215), but the excavators of the site disagree. Despite the explicit mention of a church in Jerome’s above-mentioned letter no. 46, they think that it was founded in the early fifth century AD. No church is mentioned in letter no. 108, dated 404 AD, proving that letter no. 46 should not be taken at face value, but rather in association with the attempt to persuade Marcella to visit the Holy Land (Magen and Aharonovich 2012, p. 164). One way or another, this church is one of the earliest excavated in Judea and Samaria and reflects an initial phase of the Christianization of the rural Holy Land.

Opposite this church, a baptisterium was excavated. The baptisterium was built in a building from the late Roman period, and it too is dated to the early fifth century due to an inscription mentioning Eutonis the Bishop and Germanus the Priest from the adjacent church, leading the excavators to date the buildings as belonging to the same time. The model of the baptisterium is typical of the earliest models found (Ben-Pechat 1989, p. 172, and see there Figure 1 facing p. 184), and the excavators were of the opinion that this is the earliest dated baptisterium in the Holy Land (Magen and Aharonovich 2012, pp. 194–200; Figure 6).19

Figure 6.

The ancient baptisterium. (Photographed by the authors).

The other three churches in Shiloh are dated to the 6th century. The first lies 0.6 m above the early northern Church. It was already noted by the Danish expedition, but when excavated in full, the large basilical church revealed measured 34.50 × 14.00 m. The entrance was shifted to the west by destroying the colonnaded street and it included an atrium (Magen and Aharonovich 2012, p. 179). Hence, unlike the early church that fit an early design, here we can see a standard church with the characteristics of other 6th century Byzantine churches. This fact indicates the full Christianization of Shiloh in the 6th century.

Southeast of the northern churches there is another 6th century Byzantine church called the ‘Basilica Church’ (Dadon 2012; Figure 7). The church measured 39.60 × 15.00 m and was built on the eastern side of a Roman period structure (ibid, p. 223). The church had two phases and Dadon has suggested that the first phase concluded following the Samaritan revolts from 484 CE to 529 CE (ibid).

Figure 7.

The restored Basilica Church. (Photographed by the authors).

The southernmost church is called the ‘Pilgrims’ Church’. This church is in fact an independent complex, measuring 12.20 × 25.50 m., which included a cistern and many rooms of various sizes (Kjaer 1930, pp. 40–73; 1931, pp. 78–84; Andersen 1985, pp. 61–75). In the eastern end, a chapel was erected and a very unique mosaic was revealed, containing a tree flanked by two stags.20 However, due to the significant distance from the city, the small chapel and the large number of rooms, the present authors contend that the compound was made not only for pilgrims, but as a monastery.21 The report of the Danish excavators mentioned that the church was burned in the mid-7th century, connecting this to the Arab conquest (Andersen 1985, p. 75).

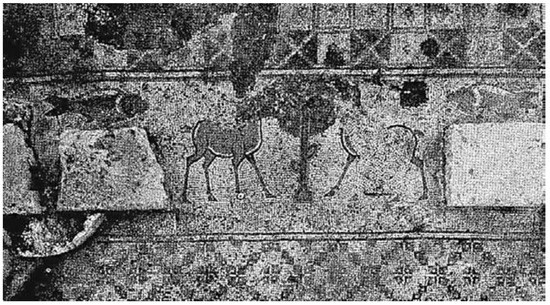

The significance of the site of Shiloh is evident from the fact that at least three churches existed concurrently in the sixth century and into the Early Muslim period. We know this from the iconoclasm of the figures in the mosaic floors (Magen and Aharonovich 2012, p. 205; Figure 8).22 Hananya Hizmi and Michal Haber suggested that the iconoclasm was an edict of the Caliph Yazid II in 721 AD, almost a century after the Muslim occupation (Hizmi and Haber 2014, p. 111, for a different opinion see Yuval-Hacham 2018). In any case, similar to other settlements in Palestine such as Beit Shean, the earthquake of 749 AD appears to have badly damaged the churches and these were not rehabilitated subsequently (Magen and Aharonovich 2012, p. 205). The reason for this lack of rehabilitation seems to be that following the Muslim occupation fewer pilgrims came to the Holy Land, while rival sites were established in Europe (Turner and Turner 1978, p. 168; Campbell 1988, p. 31, note 11).23

Figure 8.

Iconoclasm in the Pilgrims’ Church (Kjaer 1931, p. 53). These mosaics no longer exist today.

To sum up the finds in Byzantine Shiloh, it is evident that the site flourished in that era. Ofer Sion defined the site in the Byzantine period as a medium-sized village (Sion 2001, p. 142). The other excavators of Byzantine Shiloh also describe a prosperous Christian settlement and maybe a monastery. This suggestion arose based on a square tower with a burial stone, characteristic of various monasteries in the region (Hizmi and Haber 2014, p. 105, note 3, 111). However, as suggested above the monastery was probably located in the ‘Pilgrims’ Church’, and the tower should be associated with other towers built in the region in the Roman period (Magen 2008b). References to the place in Christian sources also attest to its rising religious significance as perceived by the pilgrims.

4. Discussion

Shiloh’s sacredness as perceived by Christians is related to its biblical status as the location of the Tabernacle. In this context, Jerome regards the Tabernacle as a prototype of the Temple. In fact, this is a wider issue related to the sacred status of biblical sites as perceived by Christianity in general. Wilkinson referred to this topic and pointed to a process of appropriation, i.e., appropriation of Jewish sites and the dominance of Biblical sites from the Old Testament in the descriptions of the first travelers (Wilkinson 1990, pp. 44–45). Wilkinson also showed that in the description of the anonymous traveler from Bordeaux in 333 AD, 23 of the 40 sites mentioned are from the Old Testament, versus 17 that originate from the New Testament. In the descriptions of Egeria in 381 AD, the picture is similar and even clearer: 63 Old Testament sites versus 33 from the New Testament. With regard to Paula, Wilkinson enumerated 40 Old Testament sites versus 27 from the New Testament.24

Vered Atzmon, who explored this phenomenon as well, showed that while at the beginning of the Byzantine period many sites from the Old Testament are mentioned, their number diminishes throughout this period and from the middle of the Byzantine period there is a clear dominance of sites from the New Testament (Atzmon 1997, pp. 41–48).25 Ora Limor also explained this phenomenon:

The map of the holy places for Christianity is comprised of places associated with the biblical past, now perceived as a Christian past, and places associated with the fundamental Christian story but mentioned in the Old Testament, which had now been baptized without eliminating their historical content. Places mentioned in the New Testament are added. In the period under discussion, pilgrims visited places associated with the biblical past and those associated with the Christian past with the same devotion.(Limor 1998a, p. 9)

Hence, it appears that the sacredness of Shiloh is associated with an initial stage in which the Christian holy places became established, based on the Jewish holy places. Yitzhak Magen thought that it is not clear whether establishing churches at such an early stage attests to a Christian population or to an attempt to stake a Christian claim by building a holy church rather than a community church (Magen 2012, pp. 27–28).26 In our opinion, the fact that the inscription found in the early northern church mentions not only Shiloh but also its residents should be stressed, as this indicates its role as the village church. If it is assumed that these were Christian residents, this can serve as evidence of the conversion of Shiloh’s residents to Christianity at a fairly early stage for this rural area characterized by the late arrival of Christianity (Bar 2008, p. 130; Magen 2012, pp. 28–29). Bar has shown that the community churches were located in many cases on the edges of the village, indicating gradual penetration by Christianity (Bar 2008, pp. 148–49), but the location of the church in such a central place in Shiloh may show that most of the population was Christian. Nevertheless, the integration of the baptisterium in a late Roman building (Magen and Aharonovich 2012, pp. 194–200), and the unique plan of the church may attest to a certain architectural compromise.

Shiloh’s sanctification can be linked to the flourishing of other sacred sites beginning from the fourth century AD, particularly after Constantine’s ascension to power. Ze’ev Safrai showed that at most sacred sites the place first became sanctified by local residents and only later was it recognized by the religious establishment (Safrai 1998, pp. 203–9). It may be suggested, with much caution, that the local residents of Shiloh had some traditions concerning the place of the Tabernacle and altar, as attested by Jerome, and only a while later was official recognition of the church received, in a desire to stress the Christian character of the place; but as stated, we have no proof of this process.

The development of the holy site at Shiloh during the Roman and Byzantine periods can teach us about the development of holy sites in the Holy Land. The situation at Shiloh is particularly interesting, because it is not a classic burial site, but rather a holy site that commemorates a significant Israelite historical event. Safrai dealt extensively with the emergence of Jewish (Safrai 1987) and Christian (Safrai 1998) holy sites in our relevant periods. Safrai, who examined rabbinical references to these sites, reached the conclusion that in this period the worship of holy sites had not yet been institutionalized, and most testimonies of rituals in this period come from extra-Talmudic sources such as Josephus Flavius and the Apocrypha. Indeed, the Babylonian Talmud includes several mentions of this type of worship, for example: ‘It was the practice of people to take earth from Rab’s grave and apply it [as a remedy] on the first day of an attack of fever’ (b. Sanh. 47b), but these appear to be popular rather than established customs (Safrai 1987, p. 311).

Notably, the concept of a ‘holy place’ is a recognized halakhic concept, meaning a place where halakhic precepts or prohibitions apply (Safrai 1987, p. 308). This description fits the described state in Shiloh from the Roman period to the Bar Kochba revolt. As stated, there is evidence that Shiloh was recognized as the ancient location of the Tabernacle, but there is no testimony of Jewish worship at the site, and it is clear that it did not serve as a place of pilgrimage.

Once the Jews left Shiloh after the Bar Kochba revolt, a population vacuum was formed. It was filled in time with pagan inhabitants that kept the name of the place. In general, the Christian faith spread among the land’s pagan inhabitants relatively slowly (Bar 2008, p. 127; Magen 2012, p. 1). However, the case of Shiloh is different, and Christianization occurred relatively fast. The reason for this could be the sanctity of the place in Christian eyes. Another reason could be the problematic location of Shiloh. According to the findings, the brook of Shiloh was a barrier between the Christian population to the south and the Samaritan population to the north (Bar 2008, p. 135; Magen 2008a, p. 98; 2012, p. 16; and see the map in Itah and Baruch 2001, p. 160), and therefore the Christianization of Shiloh was critical.

Incidentally, it is notable that from the end of the Byzantine period, the site at Shiloh is no longer mentioned in the accounts of travelers, and the tradition of Shiloh relocates to Nebi Samuel (Elitsur 1984, p. 80, note 31; Reiner 1988, p. 306, note 54). As stated, Theodosius in circa 570 AD already mentioned the location of Shiloh as being on the way to Emmaus, while in the Madaba Map Shiloh appears east of Shechem. Nonetheless, Theodosius’s account seems to be a collection of different sources, rather than a description of an actual journey (Limor 1998a, pp. 169–70; Wilkinson 1977, p. 65), and the location east of Shechem on the Madaba Map differs from Theodosius’ description of Shiloh as being in the vicinity of Emmaus. Since we are familiar with the continued use of churches during the Umayyad period, it seems that the place remained Christian until the end of the Umayyad period, and its lack of mention in travelers’ journals is due to the decline in travelers’ to Samaria.

This decline may be the cause for the relocation of Shiloh. The explanation for the decline follows Atzmon (1997), mentioned above. While the early Byzantine period is characterized by a marked emphasis on sites from the Old Testament, in the latter half of there is a considerable preference for sites from the New Testament. As a result, the significant of Shiloh decreased, although it was still a second-grade holy site. However, in later periods, the most significant Christian sites were chosen as a result of the short tours (Grabois 1986, p. 48). It appears that the biblical character of the site at Shiloh, as well as the religious insignificance of Samaria in the New Testament, eventually led to removal of the site from memory. The site identified with Shiloh was ‘transferred’ to a more suitable place, while joining traditions concerning Rama and Shiloh in Nebi Samwil, located on the Jerusalem–Jaffa road. Due to this process of transferring the tradition to Nebi Samuel, although the pilgrims returned to Samaria in the Crusader period, they did not re-identify Shiloh with its original location (Grabois 1986, p. 45). A similar case of relocation of biblical places in the Crusader times can be seen in the relocation of Capharnaum to Tel Kenissa (Prawer 1986, p. 39, note 33), the relocation of Modein to Belmont castle in Suba (Harper and Pringle 2000, pp. 13–14), and the transfer of Ekron to the capitol of the second Crusader kingdom, Acre (Grabois 1986, p. 50). All three are located on the route between Acre and Jerusalem.

5. Conclusions

In this article, it was shown that the tradition of Shiloh was identified with the site until the end of the Byzantine period. Its transformation and recognition as a ‘holy place’ did not occur in the first stage, as the emergence of such holy places was not characteristic of the Jewish population before the Bar Kochba revolt. Although no clear testimonies were found of rituals on the site, a tradition concerning the location of the Tabernacle was found and maybe an indication that some sacredness remained.

After the Bar Kochba revolt, the settlement at Shiloh became Roman-pagan, and we have no testimonies of the population’s attitude to the local traditions. However, it seems that the name Shiloh was kept, and a pagan temple may have been erected. Beginning from the end of the third century AD, Eusebius raised the tradition anew while identifying the site, an identification that remained in the sources until the mid-Byzantine period and in the finds until the Umayyad period. Thus, with the rise of Christianity to power, the Byzantine authorities began to invest funds in holy sites within the Holy Land and perhaps also in Shiloh. In the Byzantine period, at least four churches and a baptisterium were built, and although they may have been damaged in the Samaritan revolt (Dadon 2012, p. 231) and maybe in the Arab conquest, some continued to function as churches in the early Muslim period until the earthquake of 749 AD. However, we do not know what type of cult was practiced in them, if any. A new mosque erected in the early Muslim period bears testimony to the decline of Christianity in Shiloh.27

Shiloh disappeared from the map of holy places for centuries, and the tradition concerning the site’s sacred status only resurfaced in the 12th century AD, in the Islamic travel literature and subsequently in the Jewish travel literature, but this shall be expanded elsewhere.

Author Contributions

Investigation, A.S.; Methodology, A.O.S.; Supervision, A.O.S.; Writing—original draft, A.S.; Writing—review & editing, A.O.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Sources and authorities are quoted according to their official names. This does not imply that the journal “Religions” takes a political stance. Responsibility for correct quotation of names is with the authors.

References

- Abu al-Fath, al-Samiri. 1985. The Kitab al-tarikh of Abu ’l-Fath. Translated by Paul Stenhouse. Sydney: University of Sydney Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aharonovich, Yevgeni, Aharon Tavger, and Dvir Raviv. 2016. Archaelogical Survey of Iron Age Sites along the Main Highway West of Shiloh and a Note on the Identification of Micha’s House. In the Hiighland’s Depht 6: 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ahituv, Shmuel. 1976. Shiloh in Encyclopaedia Biblica. Edited by Chaim Tadmor. Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, vol. 7, pp. 626–32. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Flemming Gorm. 1985. Shiloh: The Danish Excavations at Tall Sailun, Palestine, in 1926, 1929, 1932 and 1963, vol. II: The Remains from the Hellenistic to the Mamluk Periods. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- Atzmon, Vered. 1997. Traditions and Sites in the Itineraries of the Christians Pilgrims to the Holy Land in the Byzantines and Crusaders Eras. Master’s thesis, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. unpublished. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Avi-Yonah, Michael. 1954. The Madaba Mosaic Map with Introduction and Commentary. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bar, Doron. 2003. The Christianisation of Rural Palestine During Late Antiquity. Journal of Ecclesiastical History 54: 401–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar, Doron. 2008. ‘Fill the Earth’: Settlement in Palestine during the Late Roman and Byzantine Periods 135–640 c.e. Jerusalem: Yad Ben Zvi. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Bar, Doron. 2011. Urban Churches in Late Antiquity Palestine. In A city Reflected Through its Research: Historical-Geographical Studies of Jerusalem. Edited by Cobi Cohen-Hattab, Assaf Selzer and Doron Bar. Jerusalem: Magness Press, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, Pierre, Józef Tadeusz Milik, and Roland de-Vaux. 1961. Discoveries in the Judaean Desert, Vol. 2: Les Grottes de Muraba’at. Oxford: Claredon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Pechat, Malka. 1989. The Paleochristian baptismal Fonts in the Holy Land: Formal and Functional Study. Liber Annuus 39: 165–88. [Google Scholar]

- Braslvsky, Joseph. 1954. Studies in Our Country Its Past and Remains. Tel-Aviv: HaKibbutz HaMeuchad. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Buhl, Marie-Louise, and Svend Holm-Nielsen. 1969. Shiloh: The Danish Excavations at Tall Sailun, Palestine, in 1926, 1929, 1932 and 1963, Vol. 1: The Pre-Hellenistic Remains. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Mary B. 1988. The Witness and the Other World: Exotic European Travel Writing, 400–1600. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conder, Claude Reignier, and Horatio Herbert Kitchner. 1882. The Survey of Western Palestine. Vol. 2: Samaria. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Dadon, Michael. 2012. The “Basilica Church” at Shiloh. In Christians and Christianity, Vol. 3: Churches and Monasteries in Samaria and Northern Judea; Edited by Noga Carmin. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 223–34. [Google Scholar]

- Di Segni, Leah. 2012a. Greek Insciptions from early Northern Church at Shiloh and the Baptistery. In Christians and Christianity, Vol. 3: Churches and Monasteries in Samaria and Northern Judea; Edited by Noga Carmin. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 209–18. [Google Scholar]

- Di Segni, Leah. 2012b. Greek inscriptions from the late Northern Church at Shiloh. In Christians and Christianity, Vol. 3: Churches and Monasteries in Samaria and Northern Judea; Edited by Noga Carmin. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 219–22. [Google Scholar]

- Egeria. 1981. Egeria’s Travels to the Holy Land. Translated by John Wilkinson. Jerusalem: Ariel Publishing House, Warminster: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Elitsur, Yoel. 1984. Sources of the “Nebi-Samuel” Tradition. Cathedra 31: 75–90. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Eusebius. 1999. Life of Constantine. Translated by Averil Cameron, and Stuart Hall. Oxford: Claredon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eusebius. 2003. The Onomasticon. Translated and Edited by Freeman-Grenville, Greville Stewart Parker, Rupert L. Chapman and Joan E. Taylor. Jerusalem: Carta. [Google Scholar]

- Eusebius. 2005. Onomasticon: The Place Names of Divine Scripture. Translated by Steven R. Notley, and Ze’ev Safrai. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, Israel. 1993. Shiloh. In The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land. Edited by Ephraim Stern. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, vol. 4, pp. 1364–70. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, Israel, Shlomo Bunimovitz, and Zvi Lederman. 1993. Shiloh: The Archaeology of a Biblical Site. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University. [Google Scholar]

- Friedheim, Emmanuel. 2003. The Worship of Tyche in the Land of Israel during the Roman Period: A Study in Historical Geography. Jerusalem and Eretz Israel 1: 47–85. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Gevaryahu, Chaim. 1968. Shilo’s Tabernacle. Machanayim 116: 152–61. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Grabois, Ariyeh. 1986. Attachment and Alienation of the Pilgrims to the Holy Land during the Period of the Crusades. Cathedra 41: 38–45. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Hare, Douglas Robert Adams. 1985. The lives of the prophets. In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. Vol. 2: Expansions of the “Old Testament” and Legends, Wisdom and Philosophical Literature, Prayers, Psalms, and Odes, Fragments of Lost Judeo-Hellenistic Works. Edited by James H. Charleswort. Garden City: Doubleday, pp. 379–99. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, Richard P., and Denys Pringle. 2000. Belmont Castle: The Excavation of a Crusader Stronghold in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Oxford: Published for Council for British Research in the Levant by Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Geoffrey. 2005. The Exilarchate in the Sasanian Era. Ph.D. thesis, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. unpublished. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Geoffrey. 2012. A Prince Without a Kingdom: The Exilarch in the Sasanian Era. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Hizmi, Hananya, and Michael Rabbi Haber. 2014. Tel Shiloh Excavations: A Preliminary Review of the 2011 Season in Area N1. Judea and Samaria Research Studies 23: 99–112. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, E. David. 1982. Holy Land Pilgrimage in the Later Roman Empire, AD 312–460. Oxford: Claredon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ilan, Zvi. 1991. Ancient Synagogues in Israel. Tel-Aviv: Security Office Press. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Itah, Michel, and Yuval Baruch. 2001. Archaeological Survey of the Remains of Byzantines Churches in the Land of Benjamin. Judea and Samaria Research Studies 10: 159–70. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Jeremias, Joachim. 1958. Heiligengräber in Jesu Umwelt (Mt. 23, 29; Lk. 11, 47): Eine Untersuchung zur Volksreligion der Zeit Jesu. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Jerome. 1910. Epistula 46: Paulae et Eustochiae ad Marcellam. In S. Eusebii Hieronymi Opera. Edited by Isidorus Hilberg. Pars 1: Epistulae I-LXX. Vindobonae: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 329–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jerome. 1912. Epistula 108: Epitaphium Sanctae Paulae. In Eusebii Hieronymi Opera. Edited by Isidorus Hilberg. Pars 2: Epistulae LXXI-CXX. Vindobonae: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 306–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jerome. 1963. S. Hieronymi Presbyteri Opera, Part 2: Commentariorum in Esaiam Libri XII-XVIII. Edited by Marcus Adriaen. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Jerome. 1970. Commentariorum in Sophoniam. In S. Hieronymi Presbyteri Opera, Part 6: Commentarii in Prophetas. Edited by Marcus Adriaen. Minores: Turnholti, pp. 655–711. [Google Scholar]

- Jerome. 2011. Commentary on Jeremiah. Translated by Michael Graves. Downers Grove: IVP Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer, Hans. 1930. The Excavation of Shilo: The Place of Eli and Samuel. Jerusalem: Beyl-Ul-Makdes Press, Copenhagen: Andr. Fr. Host. [Google Scholar]

- Kjaer, Hans. 1931. Shiloh a Summary Report of the Second Danish Expedition 1929. Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement 63: 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Shmuel. 1933. The itinerary ITINERARIUM BURDIGALENSE on Eretz Israel. Measeph Zion 6: 12–38. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Eitan. 2009. Jewish Population in the District of Akraba during the Second Temple Period–the Archaeological Foundation. Judea and Samaria Research Studies 18: 177–200. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Eitan. 2010. The Origins of the Rural Settlers in Judean Mountains and Foothills during the Late Roman Period. New Studies on Jerusalem 16: 321–50. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Eitan. 2011. Aspects of the Material Culture of Rural Judea During the Late Roman Period (135–324 C.E.). Ph.D. thesis, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. unpublished. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Limor, Ora. 1996. Christian Tradition, Jewish Authority. Cathedra 80: 31–62. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Limor, Ora. 1998a. Holy Land Travels: Christian Pilgrims in Late Antiquity. Jerusalem: Yad Ben Zvi. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Limor, Ora. 1998b. Jewish Prophets and Christian Saints. Cathedra 87: 169–74. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Limor, Ora. 2014. Holy places and Pilgrimag: The Terms of the Discussion. In Pilgrimage: Jews, Christians, Moslems. Edited by Ora Limor, Elchanan Reiner and Miriam Frenkel. Raanana: The Open University of Israel, pp. 13–42. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Livyatan-ben-Aryeh, Reut, and Hananya Hizmi. 2014. The Excavations at the Northern Platform of Tel Shiloh for the 2012–13 Seasons. Judea and Samaria Research Studies 23: 113–30. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Luria, Benzion. 1947. Regions in Homeland. Jerusalem: Kiryat Sefer. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Magen, Yitchak. 1988. The Stone Vessel Industry in Jerusalem in the Second Temple Period. Jerusalem: Society for the Protection of Nature. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Magen, Yitchak. 2002. The Areas of Samaritan Settlement in the Roman-Byzantine period. In The Samaritans. Edited by Ephraim Stern and Hanan Eshel. Jerusalem: Yad Ben Zvi, pp. 245–71. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Magen, Yitchak. 2008a. The Samaritans and the Good Samaritan; Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Magen, Yitchak. 2008b. Late Roman Fortresses and Towers in the Southern Samaria and Northern Judea. In Judea and Samaria: Researches and Discoveries; Edited by Yitchak Magen. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 177–216. [Google Scholar]

- Magen, Yitchak. 2009. Flavia Neapolis: Shechem in the Roman Period; Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Magen, Yitchak. 2012. Christianity in Judea and Samaria in the Byzantine period. In Christians and Christianity, Vol. 1: Corpus of Christian Sites in Samaria and Northern Judea; Edited by Ayelet Hashahar Malka. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Magen, Yitchak, and Evgeny Aharonovich. 2012. The Northen Churches at Shiloh. In Christians and Christianity, Vol. 3: Churches and Monasteries in Samaria and Northern Judea; Edited by Noga Carmin. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, pp. 161–208. [Google Scholar]

- Margalioth, Mordechai. 1995. Encyclopedia of Talmudic and Geonic Literature. Tel Aviv: Yavne. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Mayerson, Philip. 1987. Palaestina Tertia—Pilgrims and Urbanization. Cathedra 45: 19–40. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Hillel. 1997. Jerome and the Jews. Ph.D. thesis, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. unpublished. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Prawer, Jehoshua. 1986. The Hebrew itineraries of the crusader period. Cathedra 40: 31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Prawer, Jehoshua. 1987. Jerusalem in the Christian perspective of the Early Middle Ages. In The History of Jerusalem: The Early Islamic Period (638–1099). Edited by Jehoshua Prawer. Jerusalem: Yad Ben Zvi, pp. 249–82. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Reeg, Gottfried. 1989. Die Ortsnamen Israels nach der Rabbinischen Literatur. Wiesbaden: L. Reichert. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner, Elchanan. 1988. Pilgrims and Pilgrimage to Eretz Yisrael, 1099–517. Ph.D. thesis, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. unpublished. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Edward, and Eli Smith. 1856. Biblical Researches in Palestine and the Adjacent Regions, A Journal of the Travels in the Year 1838. London: J. Murray, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Safrai, Ze’v. 1987. Graves of the Righteous and Holy Places in Jewish Tradition. In Zev Vilnay’s Jubilee. Edited by Eli Schiller. Jerusalem: Ariel, vol. 2, pp. 303–13. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Safrai, Ze’v. 1998. The institutionalization of the Cult of Saints in Christian Society. In Sanctity of Time and Space in Tradition and Modernity. Edited by Alberdina Houtman, Marcel Poorthuis and Jehoshua Schwartz. Leiden: Brill, pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Saradi-Mendelovici, Helen. 1990. Christian Attitudes toward Pagan Monuments in Late Antiquity and Their Legacy in Later Byzantine Centuries. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 44: 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sar-avi, Doron. 2002. Toponymes Mentioned in the Documents Dated to the Roman Period, Discovered in the Judaean Desert. Master’s thesis, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. unpublished. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Satran, David. 1995. Biblical Prophets in Byzantine Palestine: Reassessing the Lives of the Prophets. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Shemesh, Abraham Ofir. 2017. The Fragrance of Paradise: Scents, Perfumes and Incense in Jewish Tradition. Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Sion, Ofer. 2001. Settlement History in the Central Samarian Region in the Byzantine Period. Ph.D. thesis, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. unpublished. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Stern, Menachem. 1968. The Description of Palestine by Pliny the Elder and the Administrative Division of Judea at the End of the Period of the Second Temple. Tarbiz 37: 215–29. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Joan E. 1993. Christians and the Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish-Christian Origins. Oxford: Claredon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsafrir, Yoram, Leah Di Segni, and Judith Green. 1994. Tabula Imperii Romani: Iudaea Palaestina: Eretz Israel in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods: Maps and Gazetteer. Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Victor, and Edith Turner. 1978. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- van der Horst, Pieter Willem. 2002. The Tombs of the Prophets in Early Judaism. In Japheth in the Tents of Shem: Studies on Jewish Hellenism in Antiquity. Edited by Pieter Willem van der Horst. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 119–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, John. 1977. Jerusalem Pilgrims Before the Crusades. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, John. 1990. Jewish Holy Places and the Origins of Christian Pilgrimage. In The Blessings of Pilgrimage. Edited by Robert Ousterhout. Urbana Illinois: University of Illinois Press, pp. 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zissu, Boas. 2001. Rural Settlement in the Judaean Hills and Foothills from the Late Second Temple Period to the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Ph.D. thesis, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, Israel. unpublished. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Zissu, Boas. 2006. “A City Whose House-Roofs Form its City Wall”, and “a City that was not Encompassed by a Wall in the Days of Joshua Bin Nun”—According to Archaeological Finds from Judea. Judea and Samaria Research Studies 15: 85–100. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

| 1 | A short excavation season also took place in 1964 towards publication of the report. |

| 2 | On Shiloh in the Biblical period, as the location of the Tabernacle and a center for the convergence of the Israelite tribes, see (Ahituv 1976). |

| 3 | Shiloh is also mentioned in the Babylonian Talmud in the context of the permit to utilize High places (‘bamot’) for religious purposes (b. Zeb. 119a). With regard to the quote: ‘If one had a protracted issue of matter from his body, lasting as long as three normal issues, which is equivalent to the time of walking from Gadyawan to Shiloh…’ (b. Sanh. 63b), it appears that the word ‘Shiloh’ should be corrected to ‘Shiloah’, as in the Mishna (m. Zab. 1:5), and see (Friedheim 2003, p. 64, note 5). |

| 4 | According to the Ba’alei Hatosafot, this may refer to R. Akiva’s son (b. Ber. 58a, s.v. ‘except for the bald one’). |

| 5 | This was already proposed by the PEF researchers (Conder and Kitchner 1882, p. 299). |

| 6 | Pliny the Elder indeed mentions Aqrabta as one of the ten toparchies in his Naturalis Historiae (Pliny NH 5, 70), as does Josephus (War III.54–55). |

| 7 | Joan Taylor thought that the treatise was in fact written in the first quarter of the fourth century. See (Eusebius 2003, preface, pp. 3–4). |

| 8 | Leah Di Segni noted that although Eusebius mentioned the distance from Shechem, according to analysis of the inscriptions in church mosaics, the Aqraba district, including Shiloh, should be associated with the Samaria diocese (Sebastia). See (Di Segni 2012a, p. 212). |

| 9 | The magnificent sarcophagus found in nearby Turmus ʿAyya should also be mentioned in this context, see (Klein 2011, pp. 112–13). |

| 10 | On the characteristics of worship in Palestine in the Late Roman period, see (Klein 2011, pp. 281–304). |

| 11 | The aerial distance from Shiloh to Shechem is 18.6 km. |

| 12 | This letter is Jerome’s eulogy for his disciple Paula, in the form of a letter of condolence to her daughter, Eustochium, on her mother’s death, following the Roman literary tradition. Jerome’s letter tells, among other things, of his joint venture with Paula to the Holy Land before they settled in Bethlehem, and in this context of their visit to Shiloh in 386 AD. On the date of the letter see (Limor 1998a, pp. 133–38). |

| 13 | According to the legend on the founding of Rome, the daughters of the Sabines were kidnapped by Romulus, founder of the city, and his warriors. See (Limor 1998a, p. 150, note 11). |

| 14 | Jerome wrote this following Eusebius’s Life of Constantine (Eusebius 1999, p. 135). On this issue see (Prawer 1987, especially pp. 255–58). |

| 15 | It is important to note that Shiloh is the only place, besides Jerusalem, that is called ‘the Temple of the Lord’ (היכל השם), as written in Sam. 1, 1:9. |

| 16 | Mentions of Eli’s grave as located in Shiloh appear in the Middle Ages as well and we intend to discuss the meaning of this elsewhere. |

| 17 | Furthermore, Limor showed that this is probably a compilation of various sources and does not reflect an actual journey. See (Limor 1998a, pp. 169–70; Wilkinson 1977, p. 65). |

| 18 | On the meaning of the names of local bishops that appear in mosaics see (Bar 2008, pp. 134–35). Bar explains there that despite the name of the bishop this normally does not indicate that the church administration covered some of the expenditures, rather the community paid for the building. In the case of Shiloh the government may have covered some of the costs, as it is a holy site. |

| 19 | On the meaning of the baptisterium as attesting to the entrance of Christianity see (Bar 2008, p. 152). |

| 20 | Kjaer also suggested linking a mosaic of a pomegranate tree found there to Solomon’s Temple, as well as to the clothes of the High Priest who may have presided at Shiloh. See (Kjaer 1930, p. 59). |

| 21 | In a personal conversation, Yevgeny Aharonovich also accepted this hypothesis and it deserves broader consideration. |

| 22 | At present, the mosaic floors uncovered in the Pilgrims’ Church no longer exist, and only Kjaer’s photographs remain. The British indeed appointed a guard for the mosaics, but in 1934, armed people broke down the door, overcame the guard, locked him in his room, and stole some of the mosaics. On this see (Andersen 1985, p. 75). Moreover, there are reports of various natural ravages, such as a roof blown off by the wind in 1937. |

| 23 | However, see (Magen 2012, pp. 62–64) on the evident continuity between the Byzantine period and the first part of the Muslim period. |

| 24 | Limor indeed wondered about the results of this count, but not about its essence. See (Limor 1998a, p. 23, note 12; 1996, p. 32; Hunt 1982, pp. 83–106). |

| 25 | Atzmon also compared mentions of biblical sites in the Byzantine period with mentions in the Crusader period, and she concluded with regard to the Crusader period that more sites from the New Testament appear in the course of this period without ‘excluding’ biblical sites, as the crusaders wanted to use these sites as evidence of their ancestral merit, in order to establish their right to the Holy Land versus the Muslims (Atzmon 1997, pp. 104–9). There is indeed also a third category, consisting of the burial sites of martyrs and monks, which at times displaces other categories (Mayerson 1987, pp. 33–40), but this does not seem to be the case here. |

| 26 | Magen showed that this phenomenon is characteristic specifically of the Samaria region, a region little mentioned in the New Testament. For this reason, the Christians were ‘compelled’ to sanctify Jewish biblical sites in order to promote Christian entrance into these areas. One of the current authors intends to further research this subject. On the process of Christianization in the rural parts of the Holy Land see (Bar 2003). |

| 27 | On this mosque one of the authors, Amichay Schwartz, is intended to write in the foreseeable future along with Reut Livyatan-Ben-Arie and Reuven Peretz. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).