Changes in Attitudes and Beliefs Concerning Vaccination and Influenza Vaccines between the First and Second COVID-19 Pandemic Waves: A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Panel

3.2. One-Year Change in Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Concerning Vaccination and Influenza Vaccines

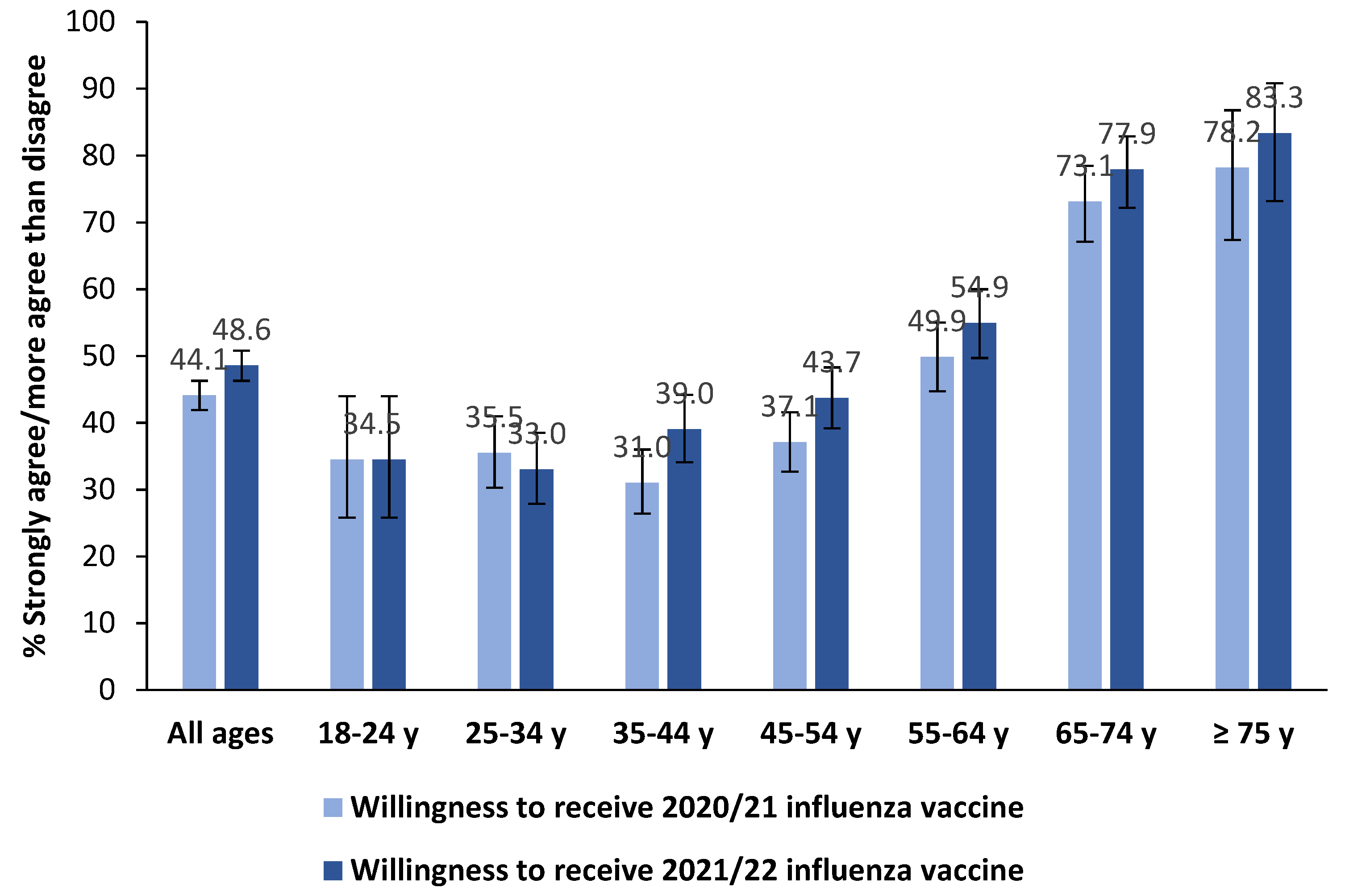

3.3. Influenza Vaccination in the Past Season, Willingness to Receive the 2021/22 Influenza Vaccination and Its Correlates

3.4. Public Opinion on the Co-Administration of COVID-19 and Influenza Vaccines and Willingness to Have a Combined Influenza/COVID-19 Vaccine

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper—November 2012. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2012, 87, 461–476. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angiolella, L.S.; Lafranconi, A.; Cortesi, P.A.; Rota, S.; Cesana, G.; Mantovani, L.G. Costs and effectiveness of influenza vaccination: A systematic review. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 2018, 54, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Waure, C.; Veneziano, M.A.; Cadeddu, C.; Capizzi, S.; Specchia, M.L.; Capri, S.; Ricciardi, W. Economic value of influenza vaccination. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2012, 8, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Influenza Vaccination Rates. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/healthcare/influenza-vaccination-rates.htm (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Influenza Vaccination Coverage Rates in the EU/EEA. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/seasonal-influenza-antiviral-use-2018.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Bosa, I.; Castelli, A.; Castelli, M.; Ciani, O.; Compagni, A.; Galizzi, M.M.; Garofano, M.; Ghislandi, S.; Giannoni, M.; Marini, G.; et al. Response to COVID-19: Was Italy (un) prepared? Health Econ. Policy Law 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Ministry of Health. Prevention and Control of Influenza: Recommendations for Season 2020–2021. Available online: http://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2020&codLeg=74451&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Region of Lazio. Mandatory Order for Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccination. Available online: http://www.regione.lazio.it/rl/coronavirus/ordinanza-per-vaccinazione-antinfluenzale-e-anti-pneumococcica-obbligatoria/ (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Region of Sicily. Influenza Vaccination Campaign 2020/2021: Involvement of GPs and Pediatricians. Available online: https://www.vaccinarsinsicilia.org/assets/uploads/files/da-n.-743.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Region of Calabria. Decree of the President of the Region of Calabria N 47 of 27th May 2020. Available online: https://portale.regione.calabria.it/website/portalmedia/2020-05/ORDINANZA-DEL-PRESIDENTE-DELLA-REGIONE-N.47-DEL-27-MAGGIO-2020.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Di Pumpo, M.; Vetrugno, G.; Pascucci, D.; Carini, E.; Beccia, V.; Sguera, A.; Zega, M.; Pani, M.; Cambieri, A.; Nurchis, M.C.; et al. Is COVID-19 a real incentive for flu vaccination? Let the numbers speak for themselves. Vaccines 2021, 9, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Ministry of Health. Influenza Vaccination Coverage. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/influenza/dettaglioContenutiInfluenza.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=679&area=influenza&menu=vuoto (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Domnich, A.; Cambiaggi, M.; Vasco, A.; Maraniello, L.; Ansaldi, F.; Baldo, V.; Bonanni, P.; Calabrò, G.E.; Costantino, C.; de Waure, C.; et al. Attitudes and beliefs on influenza vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results from a representative Italian survey. Vaccines 2020, 8, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlhoch, C.; Mook, P.; Lamb, F.; Ferland, L.; Melidou, A.; Amato-Gauci, A.J.; Pebody, R.; European Influenza Surveillance Network. Very little influenza in the WHO European Region during the 2020/21 season, weeks 40 2020 to 8 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Health. Flunews Italia. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/influenza/flunews#vir (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Abdool Karim, S.S.; de Oliveira, T. New SARS-CoV-2 variants-clinical, public health, and vaccine implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1866–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.; Archer, B.; Laurenson-Schafer, H.; Jinnai, Y.; Konings, F.; Batra, N.; Pavlin, B.; Vandemaele, K.; Van Kerkhove, M.D.; Jombart, T.; et al. Increased transmissibility and global spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as at June 2021. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleri, M.; Enzmann, H.; Straus, S.; Cooke, E. The European Medicines Agency’s EU conditional marketing authorisations for COVID-19 vaccines. Lancet 2021, 397, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). ISTAT Classification of the Italian Education Qualifications. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2011/01/Classificazione-titoli-studio-28_ott_2005-nota_metodologica.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Vatcheva, K.P.; Lee, M.; McCormick, J.B.; Rahbar, M.H. Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 2016, 6, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Ibuka, Y.; Chapman, G.B.; Meyers, L.A.; Li, M.; Galvani, A.P. The dynamics of risk perceptions and precautionary behavior in response to 2009 (H1N1) pandemic influenza. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caserotti, M.; Girardi, P.; Rubaltelli, E.; Tasso, A.; Lotto, L.; Gavaruzzi, T. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Vaccine Confidence Project. State of Vaccine Confidence in the EU+UK. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/vaccination/docs/2020_confidence_rep_en.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Fridman, A.; Gershon, R.; Gneezy, A. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odone, A.; Bucci, D.; Croci, R.; Riccò, M.; Affanni, P.; Signorelli, C. Vaccine hesitancy in COVID-19 times. An update from Italy before flu season starts. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, e2020031. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, P.; Rauber, D.; Betsch, C.; Lidolt, G.; Denker, M.L. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior-A systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005–2016. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M.; Hernández-Ramos, I.; Kurup, A.S.; Albrecht, D.; Vivas-Torrealba, C.; Franco-Paredes, C. Social determinants of health and seasonal influenza vaccination in adults ≥65 years: A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative data. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yeung, M.P.; Lam, F.L.; Coker, R. Factors associated with the uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination in adults: A systematic review. J. Public Health 2016, 38, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okoli, G.N.; Reddy, V.K.; Al-Yousif, Y.; Neilson, C.J.; Mahmud, S.M.; Abou-Setta, A.M. Sociodemographic and health-related determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence since 2000. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dini, G.; Toletone, A.; Sticchi, L.; Orsi, A.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Durando, P. Influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: A comprehensive critical appraisal of the literature. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2018, 14, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fabiani, M.; Volpe, E.; Faraone, M.; Bella, A.; Rizzo, C.; Marchetti, S.; Pezzotti, P.; Chini, F. Influenza vaccine uptake in the elderly population: Individual and general practitioner’s determinants in Central Italy, Lazio region, 2016–2017 season. Vaccine 2019, 37, 5314–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachtiger, P.; Adamson, A.; Chow, J.; Sisodia, R.; Quint, J.K.; Peters, N.S. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the pptake of influenza vaccine: UK-wide observational study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e26734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallè, F.; Sabella, E.A.; Roma, P.; De Giglio, O.; Caggiano, G.; Tafuri, S.; Da Molin, G.; Ferracuti, S.; Montagna, M.T.; Liguori, G.; et al. Knowledge and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination among undergraduate students from Central and Southern Italy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; Jin, H.; Lin, L. Vaccination against COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of acceptability and its predictors. Prev. Med. 2021, 150, 106694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarría-Santamera, A.; Timoner, J. Influenza vaccination in old adults in Spain. Eur. J. Pub. Health 2003, 13, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Milstein, A. Influence of a COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness and safety profile on vaccination acceptance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021726118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, I. Adults’ statistical literacy: Meanings, components, responsibilities. Int. Stat. Rev. 2002, 20, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tentori, K.; Passerini, A.; Timberlake, B.; Pighin, S. The misunderstanding of vaccine efficacy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 114273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodemer, N.; Müller, S.M.; Okan, Y.; Garcia-Retamero, R.; Neumeyer-Gromen, A. Do the media provide transparent health information? A cross-cultural comparison of public information about the HPV vaccine. Vaccine 2012, 30, 3747–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A.; Appel, S.; Sundberg, C.J.; Rosenqvist, M. Medicine and the media: Medical experts’ problems and solutions while working with journalists. PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, e0220897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Stirling, R.; Young, K. Should individuals use influenza vaccine effectiveness studies to inform their decision to get vaccinated? Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2019, 45, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine Effectiveness: How Well Do Flu Vaccines Work? Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/vaccineeffect.htm (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Sah, P.; Medlock, J.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Singer, B.H.; Galvani, A.P. Optimizing the impact of low-efficacy influenza vaccines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5151–5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Head, K.J.; Kasting, M.L.; Sturm, L.A.; Hartsock, J.A.; Zimet, G.D. A national survey assessing SARS-CoV-2 vaccination intentions: Implications for future public health communication efforts. Sci. Commun. 2020, 42, 698–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurie, K.L.; Rockman, S. Which influenza viruses will emerge following the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic? Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2021, 15, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. The association between influenza vaccination and COVID-19 and its outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Vaccines 2021, 9, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boytchev, H. Why did a German newspaper insist the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine was inefficacious for older people-without evidence? BMJ 2021, 372, n414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italian Ministry of Health. Prevention and Control of Influenza: Recommendations for Season 2021–2022. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2021&codLeg=79647&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Dodd, D. Benefits of combination vaccines: Effective vaccination on a simplified schedule. Am. J. Manag. Care 2003, 9 (Suppl. S1), S6–S12. [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist, S.A.; Nanni, A.; Levine, O. Benefits and effectiveness of administering pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine with seasonal influenza vaccine: An approach for policymakers. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 596–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toback, S.; Galiza, E.; Cosgrove, C.; Galloway, J.; Goodman, A.L.; Swift, P.A.; Rajaram, S.; Graves-Jones, A.; Edelman, J.; Burns, F.; et al. Safety, Immunogenicity, and Efficacy of a COVID-19 Vaccine (NVX-CoV2373) Co-Administered with Seasonal Influenza Vaccines. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.09.21258556v1 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Authorized in the United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html#Coadministration (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Massare, M.J.; Patel, N.; Zhou, B.; Maciejewski, S.; Flores, R.; Guebre-Xabier, M.; Tian, J.H.; Portnoff, A.D.; Fries, L.; Shinde, V.; et al. Combination Respiratory Vaccine Containing Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Spike and Quadrivalent Seasonal Influenza Hemagglutinin Nanoparticles with Matrix-M Adjuvant. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.05.05.442782v1.full.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Chaparian, R.R.; Harding, A.T.; Riebe, K.; Karlsson, A.; Sempowski, G.D.; Heaton, N.S.; Heaton, B.E. Influenza Viral Particles Harboring the SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD as a Combination Respiratory Disease Vaccine. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.04.30.441968v1.full.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Health for All. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/14562 (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Boggavarapu, S.; Sullivan, K.M.; Schamel, J.T.; Frew, P.M. Factors Associated with seasonal influenza immunization among church-going older African Americans. Vaccine 2014, 32, 7085–7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- King, J.P.; McLean, H.Q.; Belongia, E.A. Validation of self-reported influenza vaccination in the current and prior season. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses. 2018, 12, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | Level | % (N) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 54.9 (1086) | 52.6–57.1 |

| Female | 45.1 (893) | 42.9–47.3 | |

| Age group, years | 18–24 | 5.7 (113) | 4.7–6.8 |

| 24–34 | 16.2 (321) | 14.6–17.9 | |

| 35–44 | 18.9 (374) | 17.2–20.7 | |

| 45–54 | 23.7 (469) | 21.8–25.6 | |

| 55–64 | 18.9 (375) | 17.2–20.7 | |

| 65–74 | 12.6 (249) | 11.2–14.1 | |

| ≥75 | 3.9 (78) | 3.1–4.9 | |

| Geographic area | North-East | 19.0 (376) | 17.3–20.8 |

| North-West | 28.0 (555) | 26.1–30.1 | |

| Center | 21.2 (419) | 19.4–23.0 | |

| South | 21.9 (434) | 20.1–23.8 | |

| Islands | 9.9 (195) | 8.6–11.3 | |

| ISCED educational level | 1 | 0.7 (14) | 0.4–1.2 |

| 2 | 7.8 (154) | 6.6–9.1 | |

| 3–4 | 48.0 (949) | 45.7–50.2 | |

| 5 | 41.5 (821) | 39.3–43.7 | |

| 6 | 2.1 (41) | 1.5–2.8 | |

| Employment pattern | Employed | 63.7 (1261) | 61.6–65.8 |

| Student | 6.2 (122) | 5.1–7.3 | |

| Housekeeper | 6.1 (121) | 5.1–7.3 | |

| Unemployed | 5.8 (114) | 4.8–6.9 | |

| Retired | 16.1 (319) | 14.5–17.8 | |

| Other/prefer not to reply | 2.1 (42) | 1.5–2.9 | |

| Perceived income | Low | 2.0 (39) | 1.4–2.7 |

| Lower than average | 7.6 (150) | 6.5–8.8 | |

| Average | 32.3 (639) | 30.2–34.4 | |

| Higher than average | 42.7 (846) | 40.6–45.0 | |

| High | 2.0 (40) | 1.5–2.7 | |

| No personal income | 13.4 (265) | 11.9–15.0 | |

| Self-reported health status | Excellent | 9.1 (181) | 7.9–10.5 |

| Very good | 45.5 (901) | 43.3–47.8 | |

| Good | 42.0 (832) | 39.9–44.3 | |

| Fair | 3.0 (59) | 2.3–3.8 | |

| Poor | 0.3 (6) | 0.1–0.7 | |

| Influenza vaccination in 2019/20 season | Yes | 26.5 (524) | 24.5–28.5 |

| No | 73.5 (1455) | 71.5–75.5 |

| Item | % (95% CI) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreed a in Both 2020 and 2021 | Agreed a in 2021 But Disagreed b in 2020 | Agreed a in 2020 But Disagreed b in 2021 | Disagreed b in Both 2020 and 2021 | ||

| Vaccines are crucial to guaranteeing public health and should be mandatory | 64.9 (62.8–67.0) | 12.3 (10.9–13.9) | 10.1 (8.8–11.5) | 12.7 (11.2–14.2) | 0.037 |

| I need more information on vaccines | 69.1 (67.0–71.1) | 13.5 (12.1–15.1) | 9.8 (8.5–11.2) | 7.6 (6.5–8.8) | 0.001 |

| Vaccines are a fraud designed to profit pharmaceutical companies | 12.0 (10.6–13.5) | 6.3 (5.3–7.5) | 13.5 (12.1–15.1) | 68.1 (66.0–70.2) | <0.001 |

| Influenza vaccination is a human right and must be guaranteed for people that would like to be vaccinated | 82.5 (80.8–84.2) | 7.5 (6.4–8.7) | 7.1 (6.0–8.3) | 2.9 (2.2–3.7) | 0.72 |

| It is unacceptable that there are no influenza vaccines in the coming season for people that would like to be vaccinated | 77.7 (75.8–79.5) | 9.5 (8.2–10.9) | 8.4 (7.3–9.8) | 4.4 (3.5–5.4) | 0.29 |

| If there were no free-of-charge influenza vaccine, I would pay for it out of my own pocket | 38.2 (36.0–40.3) | 15.4 (13.8–17.1) | 14.4 (12.8–16.0) | 32.1 (30.0–34.2) | 0.41 |

| There are different types of influenza vaccine | 37.0 (34.9–39.2) | 22.7 (20.9–24.7) | 14.8 (13.3–16.4) | 25.5 (23.6–27.4) | <0.001 |

| I would be more willing to receive a flu shot if it were personalized | 56.5 (54.3–58.7) | 15.8 (14.2–17.4) | 12.2 (10.8–13.8) | 15.5 (13.9–17.1) | 0.003 |

| Information Source | Mean (SD) | p | Effect Size, d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 Survey | 2021 Survey | |||

| My physician | 7.4 (2.2) | 7.9 (2.0) | <0.001 | 0.23 |

| Public health institutions | 6.8 (2.4) | 7.3 (2.2) | <0.001 | 0.22 |

| My pharmacist | 6.3 (2.3) | 7.0 (2.1) | <0.001 | 0.32 |

| Newspapers/TV | 4.6 (2.2) | 5.5 (2.2) | <0.001 | 0.37 |

| Friends | 4.4 (2.3) | 4.5 (2.3) | 0.054 | 0.04 |

| Social media | 3.2 (2.3) | 3.7 (23) | <0.001 | 0.22 |

| Willingness to Receive 2020/21 Influenza Vaccine (2020 Survey) | 2020/21 Season Reported Vaccination (2021 Survey), % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Definitely yes (N = 465) | 84.9 (81.4–88.1) | 15.1 (11.9–18.6) |

| Probably yes (N = 408) | 47.3 (42.4–52.3) | 52.7 (47.7–57.6) |

| I do not know (N = 282) | 18.1 (13.8–23.1) | 81.9 (76.9–86.2) |

| Probably not (N = 444) | 17.8 (14.3–21.7) | 82.2 (78.3–85.7) |

| Definitely not (N = 380) | 11.1 (8.1–14.6) | 88.9 (85.4–91.9) |

| Total (N = 1979) | 38.4 (36.3–40.6) | 61.6 (59.4–63.7) |

| Reason | 2020 (N = 997) | 2021 (N = 887) |

|---|---|---|

| Influenza vaccines are designed only to profit pharmaceutical companies | 21.0 (18.5–23.6) | 12.9 (10.7–15.2) |

| Influenza vaccines do not work | 17.9 (15.5–20.4) | 12.0 (9.9–14.3) |

| I am afraid of needles | 8.5 (6.9–10.4) | 8.2 (6.5–10.2) |

| I had a flu shot but developed a fever/cold anyway | 8.5 (6.9–10.4) | 5.5 (4.1–7.2) |

| My doctor advised against it | 7.9 (6.3–9.8) | 7.0 (5.4–8.9) |

| Flu has diminished drastically since the COVID-19 pandemic began, so I do not think a flu shot is necessary any more | NA a | 13.9 (11.7–16.3) |

| Other | 36.2 (33.2–39.3) | 40.6 (37.3–43.9) |

| Variable | Level | aOR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | Ref | - |

| Male | 1.34 (1.03–1.75) | 0.032 | |

| Age | 1-year increase | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.014 |

| Influenza vaccination in the 2019/20 season | No | Ref | - |

| Yes | 4.11 (2.73–6.19) | <0.001 | |

| Influenza vaccination in the 2020/21 season | No | Ref | - |

| Yes | 13.62 (9.64–19.25) | <0.001 | |

| COVID-19 vaccination status | No, and I do not intend to receive a shot in the future | Ref | - |

| Not yet, but I will receive a shot as soon as possible | 5.52 (2.60–11.69) | <0.001 | |

| Not yet, but I have already booked my shot | 6.13 (2.85–13.21) | <0.001 | |

| Yes | 9.46 (4.48–19.97) | <0.001 | |

| Vaccines are crucial to guaranteeing public health and should be mandatory | Disagree a | Ref | - |

| Agree b | 1.87 (1.25–2.80) | 0.002 | |

| All vaccines are safe | Disagree a | Ref | - |

| Agree b | 1.53 (1.10–2.14) | 0.011 | |

| Influenza vaccination is a human right and must be guaranteed | Disagree a | Ref | - |

| Agree b | 2.08 (1.16–3.73) | 0.014 | |

| It is unacceptable that there are no influenza vaccines in the future season | Disagree a | Ref | - |

| Agree b | 2.83 (1.63–4.89) | <0.001 | |

| If there were no free-of-charge influenza vaccine, I would pay for it out of my own pocket | Disagree a | Ref | - |

| Agree b | 1.64 (1.25–2.16) | <0.001 | |

| I would be more inclined to receive a flu shot if it were personalized | Disagree a | Ref | - |

| Agree b | 2.37 (1.69–3.34) | <0.001 | |

| Confidence in one’s own physician | 1-point increase | 1.18 (1.09–1.28) | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Domnich, A.; Grassi, R.; Fallani, E.; Spurio, A.; Bruzzone, B.; Panatto, D.; Marozzi, B.; Cambiaggi, M.; Vasco, A.; Orsi, A.; et al. Changes in Attitudes and Beliefs Concerning Vaccination and Influenza Vaccines between the First and Second COVID-19 Pandemic Waves: A Longitudinal Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9091016

Domnich A, Grassi R, Fallani E, Spurio A, Bruzzone B, Panatto D, Marozzi B, Cambiaggi M, Vasco A, Orsi A, et al. Changes in Attitudes and Beliefs Concerning Vaccination and Influenza Vaccines between the First and Second COVID-19 Pandemic Waves: A Longitudinal Study. Vaccines. 2021; 9(9):1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9091016

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomnich, Alexander, Riccardo Grassi, Elettra Fallani, Alida Spurio, Bianca Bruzzone, Donatella Panatto, Barbara Marozzi, Maura Cambiaggi, Alessandro Vasco, Andrea Orsi, and et al. 2021. "Changes in Attitudes and Beliefs Concerning Vaccination and Influenza Vaccines between the First and Second COVID-19 Pandemic Waves: A Longitudinal Study" Vaccines 9, no. 9: 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9091016

APA StyleDomnich, A., Grassi, R., Fallani, E., Spurio, A., Bruzzone, B., Panatto, D., Marozzi, B., Cambiaggi, M., Vasco, A., Orsi, A., & Icardi, G. (2021). Changes in Attitudes and Beliefs Concerning Vaccination and Influenza Vaccines between the First and Second COVID-19 Pandemic Waves: A Longitudinal Study. Vaccines, 9(9), 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9091016