Surge in Measles Cases in Italy from August 2023 to January 2025: Characteristics of Cases and Public Health Relevance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

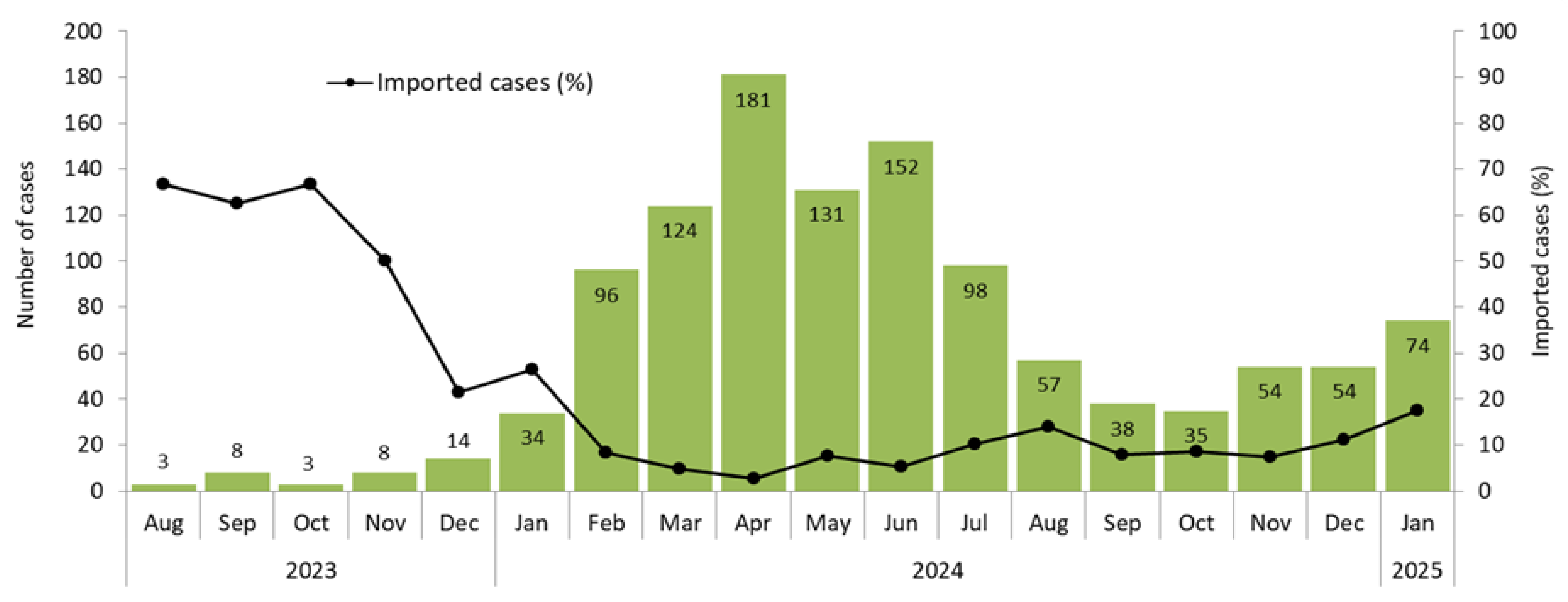

3.1. Number and Classification of Cases, Including Imported Cases

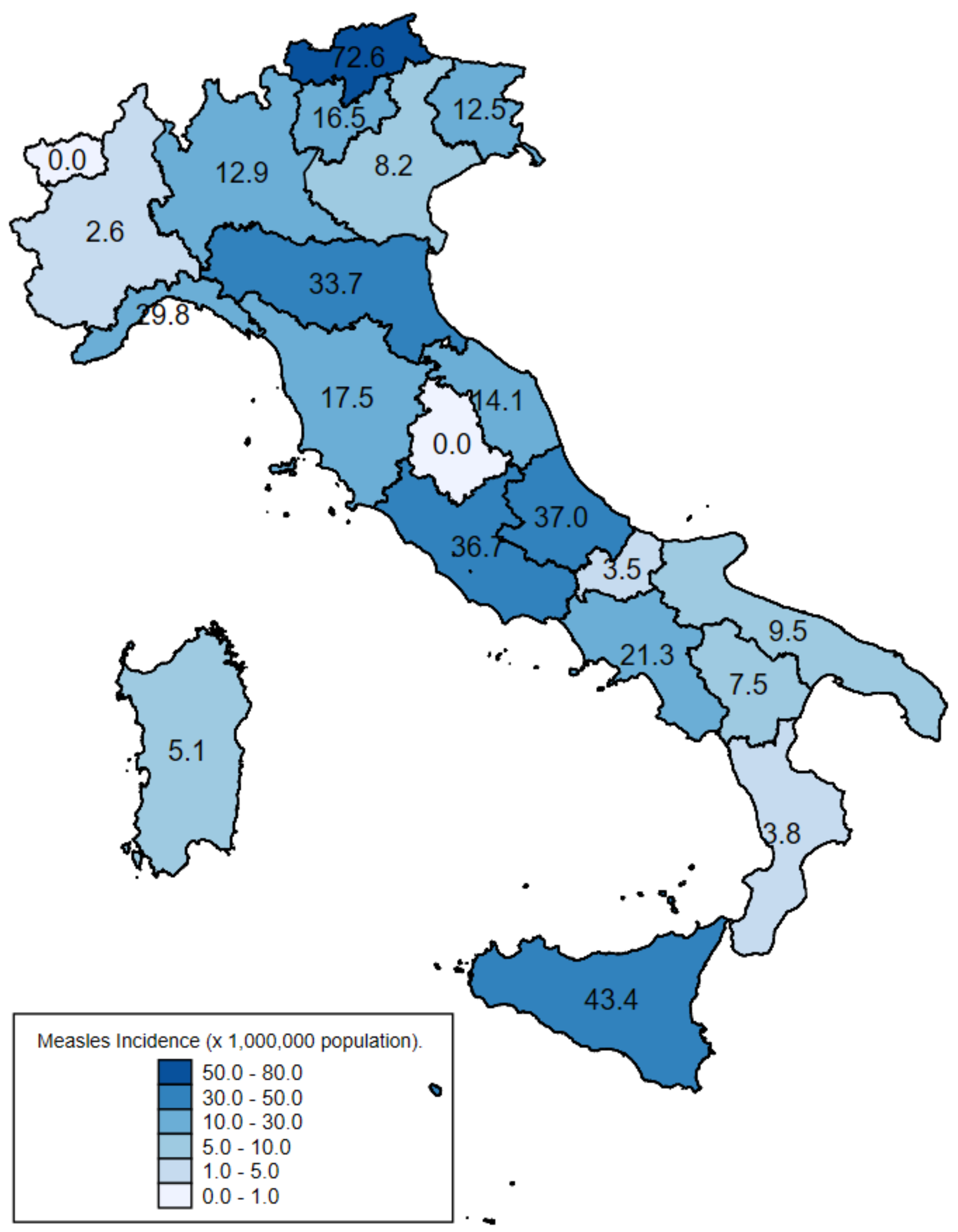

3.2. Geographic Distribution of Cases

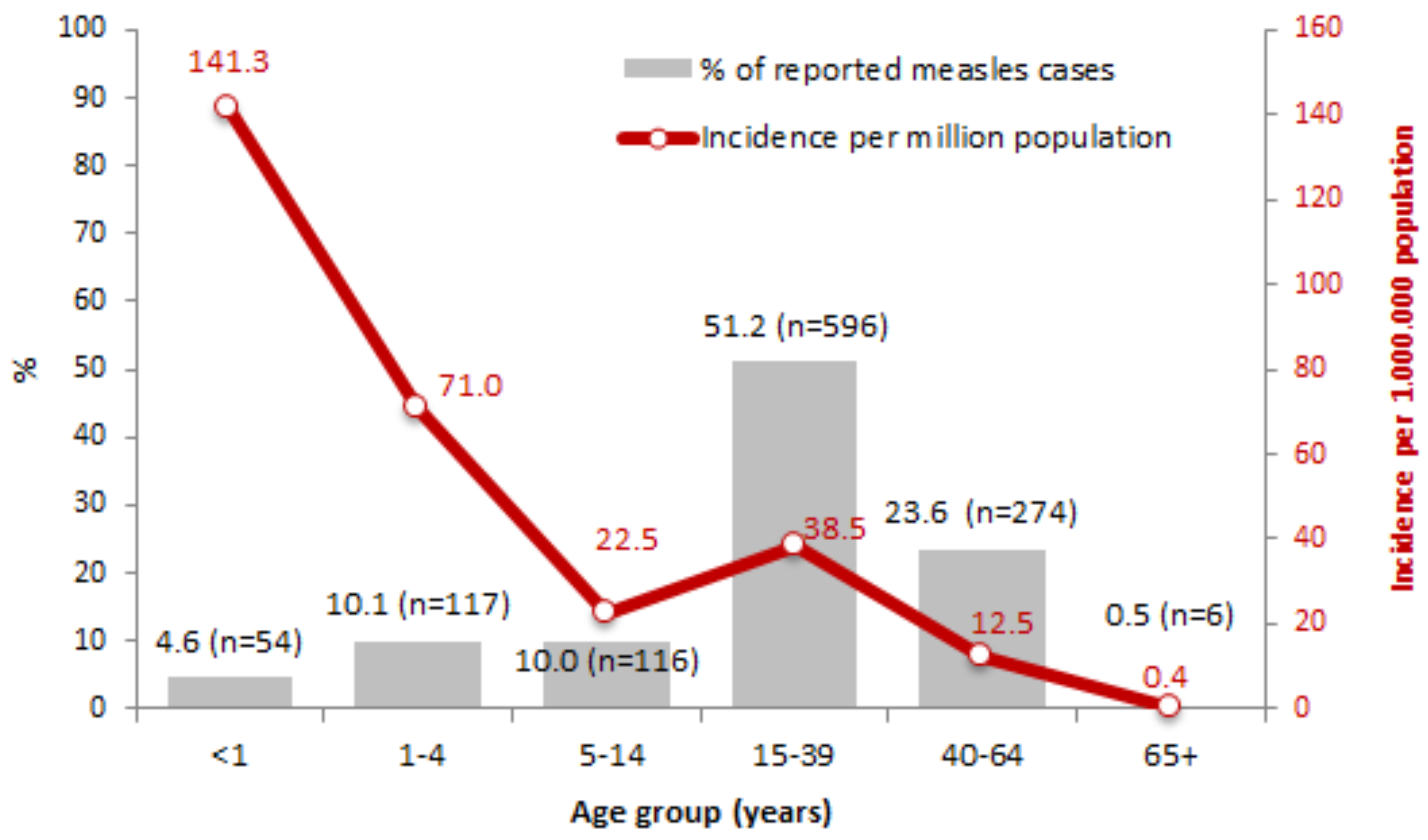

3.3. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Cases

3.4. Vaccination Status

3.5. Complications and Hospital Admissions

3.6. Transmission Settings

3.7. Genotyping

3.8. Public Health Measures

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hübschen, J.M.; Gouandjika-Vasilache, I.; Dina, J. Measles. Lancet 2022, 399, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Factsheet About Measles. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/measles/facts (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. Measles Vaccines: WHO Position Paper—April 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 92, pp. 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Shattock, A.J.; Johnson, H.C.; Sim, S.Y.; Carter, A.; Lambach, P.; Hutubessy, R.C.W.; Thompson, K.M.; Badizadegan, K.; Lambert, B.; Ferrari, P.M.J.; et al. Contribution of vaccination to improved survival and health: Modelling 50 years of the Expanded Programme on Immunization. Lancet 2024, 403, 2307–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscat, M.; Ben Mamou, M.; Reynen-de Kat, C.; Jankovic, D.; Hagan, J.; Singh, S.; Datta, S.S. Progress and Challenges in Measles and Rubella Elimination in the WHO European Region. Vaccines 2024, 12, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Eliminating Measles and Rubella in the WHO European Region; Integrated Guidance for Surveillance, Outbreak Response and Verification of Elimination; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Public Health Risk Assessment Related to Measles: Implications for the Americas Region 24 March 2025. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/public-health-risk-assessment-related-measles-implications-americas-region-24-march-2025 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. Measles Cases Surge Worldwide, Infecting 10.3 Million People in 2023. 14 November 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-11-2024-measles-cases-surge-worldwide--infecting-10.3-million-people-in-2023 (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Facchin, G.; Bella, A.; Del Manso, M.; Rota, M.C.; Filia, A. Decline in reported measles cases in Italy in the COVID-19 era, January 2020–July 2022: The need to prevent a resurgence upon lifting non-pharmaceutical pandemic measures. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1286–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Measles on the Rise in the EU/EEA: Considerations for Public Health Response. 16 February 2024; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization—Europe. Media Release 13 March 2025. European Region Reports Highest Number of Measles Cases in More Than 25 Years—UNICEF, WHO/Europe. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/13-03-2025-european-region-reports-highest-number-of-measles-cases-in-more-than-25-years---unicef--who-europe (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Plans-Rubió, P. Measles Vaccination Coverage and Anti-Measles Herd Immunity Levels in the World and WHO Regions Worsened from 2019 to 2023. Vaccines 2025, 13, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO EpiBrief: A Report on the Epidemiology of Selected Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the European Region: No. 1/2025; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/381120/WHO-EURO-2025-12024-51796-79356-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. Measles Vaccination Coverage. Available online: https://immunizationdata.who.int/global/wiise-detail-page/measles-vaccination-coverage?CODE=EUR&ANTIGEN=MCV1&YEAR= (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. 13th Meeting of the European Regional Verification Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination (RVC). Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/events/item/2024/09/10/default-calendar/13th-meeting-of-the-european-regional-verification-commission-for-measles-and-rubella-elimination-(rvc) (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- World Health Organization. Twelfth meeting of the European Regional Verification Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination: 8–11 September 2023, Copenhagen, Denmark; Meeting Report; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Filia, A.; Bella, A.; Cadeddu, G.; Milia, M.R.; Del Manso, M.; Rota, M.C.; Magurano, F.; Nicoletti, L.; Declich, S. Extensive Nosocomial Transmission of Measles Originating in Cruise Ship Passenger, Sardinia, Italy, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 1444–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- European Commission. Commission Decision of 22 June 2018 on the communicable diseases and related special health issues to be covered by epidemiological surveillance as well as relevant case definitions; Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2018/945. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, 61, 170/30. [Google Scholar]

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Morbillo & Rosolia News: Il Bollettino Della Sorveglianza Integrata Morbillo-Rosolia; Istituto Superiore di Sanità: Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/morbillo/bollettino (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Measles-Annual Epidemiological Report for 2024; ECDC: Stockholm, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Filia, A.; Bella, A.; Del Manso, M.; Baggieri, M.; Magurano, F.; Rota, M.C. Ongoing outbreak with well over 4000 measles cases in Italy from January to end August 2017—What is making elimination so difficult? Eurosurveillance 2017, 22, 30614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perfetto, B.; Paduano, G.; Grimaldi, E.; Sansone, V.; Donnarumma, G.; Di Giuseppe, G. Seroprevalence of measles antibodies in the Italian general population in 2019–2020. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126012. [Google Scholar]

- Springer, D.N.; Borsodi, C.; Camp, J.V.; Redlberger-Fritz, M.; Holzmann, H.; Kundi, M.; Aberle, J.H.; Stiasny, K.; Weseslindtner, L. Seroprevalence against measles, Austria, stratified by birth years 1922 to 2024. Eurosurveillance 2025, 30, 2400684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenk, J.; Abrams, S.; Litzroth, A.; Cornelissen, L.; Grammens, T.; Theeten, H.; Hens, N. Identifying immunity gaps for measles using Belgian serial serology data. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3676–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedricha, N.; Poethko-Müller, C.; Kuhnert, R.; Matysiak-Klose, D.; Koch, J.; Wichmann, O.; Santibanez, S.; Mankertz, A. Seroprevalence of Measles-, Mumps-, and Rubella-specific antibodies in the German adult population—Cross-sectional analysis of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 7, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonbergerr, K.; Ludwig, M.-S.; Wildner, M.; Weissbrich, B. Epidemiology of Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE) in Germany from 2003 to 2009: A Risk Estimation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Italy. Vaccination Coverage Data. (In Italian). Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/vaccinazioni/dettaglioContenutiVaccinazioni.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=811&area=vaccinazioni&menu=vuoto (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. A Practical Guide to Identifying, Addressing and Tracking Inequities in Immunization; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Measles vaccines WHO Position Paper. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2017, 92, 205–228. [Google Scholar]

| Transmission Setting | n. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Household | 228 | 42.6 |

| Nosocomial/healthcare | 107 | 20.0 |

| Travel | 94 | 17.6 |

| Work (excluding healthcare settings) | 47 | 8.8 |

| School | 30 | 5.6 |

| Prisons | 9 | 1.7 |

| Public gathering events | 11 | 2.0 |

| Other | 9 | 1.7 |

| Total | 535 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Filia, A.; Del Manso, M.; Petrone, D.; Magurano, F.; Gioacchini, S.; Pezzotti, P.; Palamara, A.T.; Bella, A. Surge in Measles Cases in Italy from August 2023 to January 2025: Characteristics of Cases and Public Health Relevance. Vaccines 2025, 13, 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070663

Filia A, Del Manso M, Petrone D, Magurano F, Gioacchini S, Pezzotti P, Palamara AT, Bella A. Surge in Measles Cases in Italy from August 2023 to January 2025: Characteristics of Cases and Public Health Relevance. Vaccines. 2025; 13(7):663. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070663

Chicago/Turabian StyleFilia, Antonietta, Martina Del Manso, Daniele Petrone, Fabio Magurano, Silvia Gioacchini, Patrizio Pezzotti, Anna Teresa Palamara, and Antonino Bella. 2025. "Surge in Measles Cases in Italy from August 2023 to January 2025: Characteristics of Cases and Public Health Relevance" Vaccines 13, no. 7: 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070663

APA StyleFilia, A., Del Manso, M., Petrone, D., Magurano, F., Gioacchini, S., Pezzotti, P., Palamara, A. T., & Bella, A. (2025). Surge in Measles Cases in Italy from August 2023 to January 2025: Characteristics of Cases and Public Health Relevance. Vaccines, 13(7), 663. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070663