Acceptability of Herpes Zoster Vaccination among Patients with Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

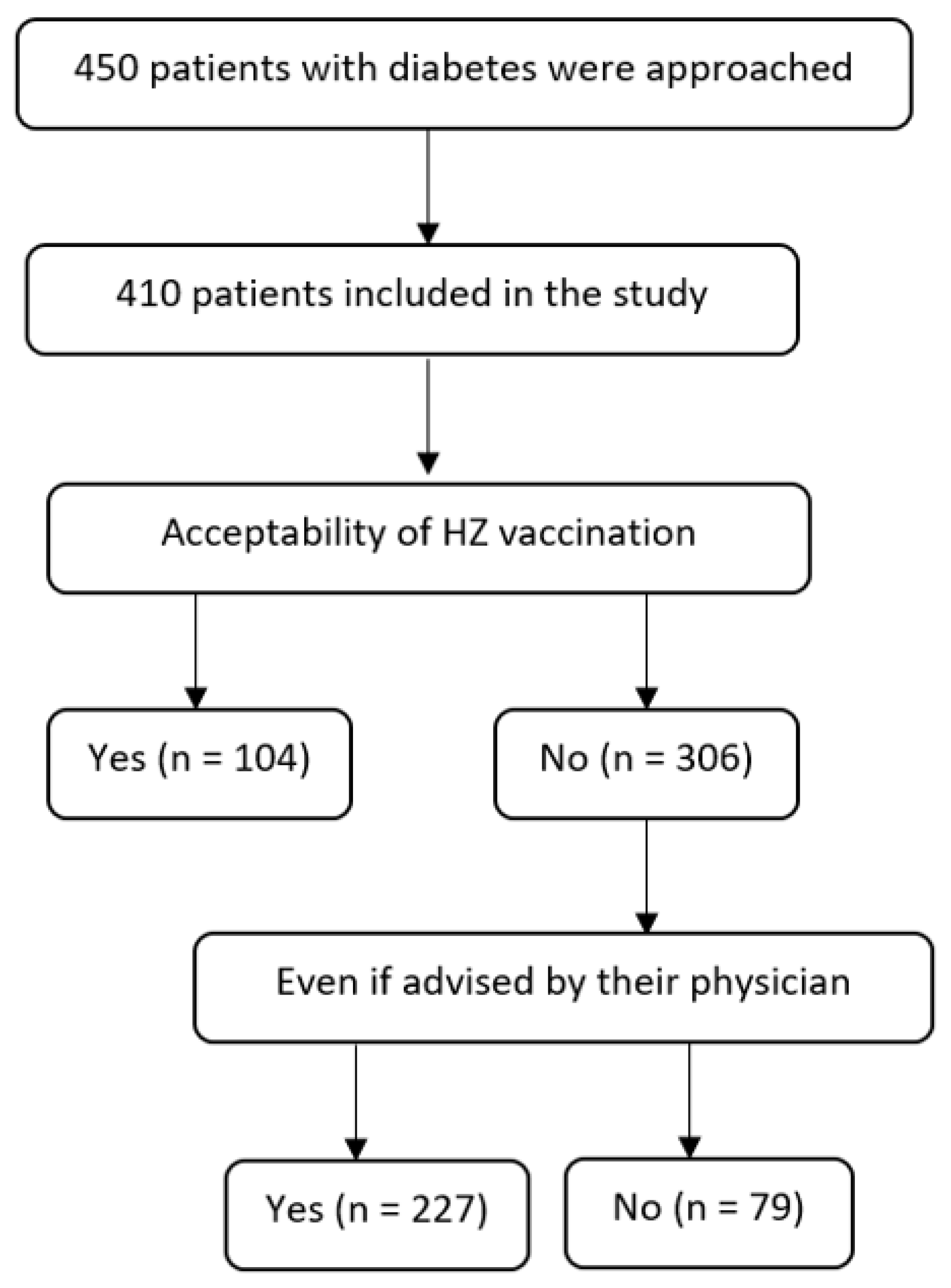

3.1. Acceptability of HZ Vaccine

3.1.1. Participant Characteristics

3.1.2. Predictors of Vaccination Acceptability

3.1.3. Reasons for HZ Vaccination Hesitancy

3.2. Acceptance of HZ Vaccine if Advised by a Physician

3.2.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2.2. Predictors of Vaccination Acceptability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdulaziz Al Dawish, M.; Alwin, R.A.; Braham, R.; Abdallah Al Hayek, A.; Al Saeed, A.; Ahmed Ahmed, R.; Sulaiman Al Sabaan, F. Diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia: A review of the recent literature. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2016, 12, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, K.; Morris, J.; Bridson, T.; Govan, B.; Rush, C.; Ketheesan, N. Immunological mechanisms contributing to the double burden of diabetes and intracellular bacterial infections. Immunology 2015, 144, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Foundation ATLAS 9th Edition 2019–Global Factsheet. 2019. Available online: https://www.diabetesatlas.org/en/ (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Binsaeedu, A.S.; Bajaber, A.O.; Muqrad, A.G.; Alendijani, Y.A.; Alkhenizan, H.A.; Alsulaiman, T.A.; Alkhenizan, A.H. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of herpes zoster disease in a primary care setting in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A retrospective cohort study. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 6433–6437. [Google Scholar]

- Steain, M.; Sutherland, J.P.; Rodriguez, M.; Cunningham, A.L.; Slobedman, B.; Abendroth, A. Analysis of T cell responses during active varicella-zoster virus reactivation in human ganglia. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 2704–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxman, M.N. Herpes zoster pathogenesis and cell-mediated immunity and immunosenescence. J. Osteopath. Med. 2009, 109, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman, D.; Shavit, O.; Stein, M.; Cohen, R.; Chodick, G.; Shalev, V. A population based study of the epidemiology of herpes zoster and its complications. J. Infect. 2013, 67, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Yawn, B.P. Risk factors for herpes zoster: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1806–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.L.; Hall, A.J. What does epidemiology tell us about risk factors for herpes zoster? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004, 4, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, L.M.A.J.; Gorter, K.J.; Hak, E.; Goudzwaard, W.L.; Schellevis, F.G.; Hoepelman, A.I.M.; Rutten, G.E.H.M. Increased risk of common infections in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamaire, M.; Maugendre, D.; Moreno, M.; Le Goff, M.C.; Allannic, H.; Genetet, B. Impaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabet. Med. 1997, 14, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plouffe, J.F.; Silva, J., Jr.; Fekety, R.; Allen, J.L. Cell-mediated immunity in diabetes mellitus. Infect. Immun. 1978, 21, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, A.; Kuniyoshi, M.; Ohkusa, Y. Risk of herpes zoster in patients with underlying diseases: A retrospective hospital-based cohort study. Infection 2011, 39, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedicino, D.; Liuzzo, G.; Trotta, F.; Giglio, A.F.; Giubilato, S.; Martini, F.; Zaccardi, F.; Scavone, G.; Previtero, M.; Massaro, G.; et al. Adaptive immunity, inflammation, and cardiovascular complications in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Res. 2013, 2013, 184258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbecke, R.; Cohen, J.I.; Oxman, M.N. Herpes zoster vaccines. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, S429–S442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, E.D.; Woodward, M.; Brown, E.; Popmihajlov, Z.; Saddier, P.; Annunziato, P.W.; Halsey, N.A.; Gershon, A.A. Herpes zoster vaccine live: A 10 year review of post-marketing safety experience. Vaccine 2017, 35, 7231–7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, Y.Y. Recombinant zoster vaccine (ShingrixR): A review in Herpes Zoster. Drugs Aging 2018, 35, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shingles Vaccine Available in Primary Care Centers. MoH. Available online: https://saudigazette.com.sa/article/625548/SAUDI-ARABIA/Shingles-vaccine-available-in-primary-care-centers-says-Health-Ministry (accessed on 13 November 2022).

- Lam, A.C.; Chan, M.Y.; Chou, H.Y.; Ho, S.Y.; Li, H.L.; Lo, C.Y.; Shek, K.F.; To, S.Y.; Yam, K.K.; Yeung, I. A cross-sectional study of the knowledge, attitude, and practice of patients aged 50 years or above towards herpes zoster in an out-patient setting. Hong Kong Med. J. 2017, 23, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, N.; Lupi, S.; Stefanati, A.; Cova, M.; Sulcaj, N.; Piccinni, L.; GPs Study Group; Gabutti, G. Evaluation of the acceptability of a vaccine against herpes zoster in the over 50 years old: An Italian observational study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqifari, S.F.; Aldawish, R.F.; Binsaqr, M.A.; Khojah, A.A.; Alshammari, M.R.; Esmail, A.K. Trends in herpes zoster infection in Saudi Arabia: A call for expanding access to shingles vaccination. World Fam. Med. 2022, 20, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanos, G.; Dimitriou, H.; Pappas, A.; Perdikogianni, C.; Symvoulakis, E.K.; Galanakis, E.; Lionis, C. Vaccination coverage of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: Challenging issues from an outpatient secondary care setting in Greece. Front. Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.W.; Lu, P.J.; O’Halloran, A.; Bridges, C.B.; Kim, D.K.; Pilishvili, T.; Hales, C.M.; Markowitz, L.E. Vaccination coverage among adults, excluding influenza vaccination—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 64, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, N.K.; Park, Y.M.; Kang, H.; Choi, G.S.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, Y.W.; Lew, B.L.; Sim, W.Y. Awareness, knowledge, and vaccine acceptability of herpes zoster in Korea: A multicenter survey of 607 patients. Ann. Dermatol. 2015, 27, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, S.; Javed, F.; Mays, R.M.; Tyring, S.K. Herpes zoster vaccine awareness among people ≥50 years of age and its implications on immunization. Derm. Online J. 2012, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Lu, J.; Zhang, F.; Wagner, A.L.; Zhang, L.; Mei, K.; Guan, B.; Lu, Y. Low willingness to vaccinate against herpes zoster in a Chinese metropolis. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 4163–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilers, R.; De Melker, H.E.; Veldwijk, J.; Krabbe, P.F. Vaccine preferences and acceptance of older adults. Vaccine 2017, 35, 2823–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khalidi, T.; Genidy, R.; Almutawa, M.; Mustafa, M.; Adra, S.; Kanawati, N.E.; Binashour, T.; Barqawi, H.J. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the United Arab Emirates population towards Herpes Zoster vaccination: A cross-sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2073752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.U.; Cheong, H.J.; Song, J.Y.; Noh, J.Y.; Kim, W.J. Survey on public awareness, attitudes, and barriers for herpes zoster vaccination in South Korea. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2015, 11, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Zarin, W.; Cardoso, R.; Veroniki, A.A.; Khan, P.A.; Nincic, V.; Ghassemi, M.; Warren, R.; Sharpe, J.P.; Page, A.V.; et al. Efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of herpes zoster vaccines in adults aged 50 and older: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2018, 363, k4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmunds, W.J.; Brisson, M.; Rose, J.D. The epidemiology of herpes zoster and potential cost-effectiveness of vaccination in England and Wales. Vaccine 2001, 19, 3076–3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.J.; Euler, G.L.; Jumaan, A.O.; Harpaz, R. Herpes zoster vaccination among adults aged 60 years or older in the United States, 2007: Uptake of the first new vaccine to target seniors. Vaccine 2009, 27, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxman, M.; Levin, M.; Johnson, G.; Schmader, K.; Straus, S.; Gelb, L.; Arbeit, R.; Simberkoff, M.; Gershon, A.; Davis, L.; et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 2271–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H.F.; Smith, N.; Harpaz, R.; Bialek, S.R.; Sy, L.S.; Jacobsen, S.J. Herpes zoster vaccine in older adults and the risk of subsequent herpes zoster disease. JAMA 2011, 305, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, S.M.; Smeeth, L.; Margolis, D.J.; Thomas, S.L. Herpes zoster vaccine effectiveness against incident herpes zoster and post-herpetic neuralgia in an older US population: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricout, H.; Torcel-Pagnon, L.; Lecomte, C.; Almas, M.F.; Matthews, I.; Lu, X.; Wheelock, A.; Sevdalis, N. Determinants of shingles vaccine acceptance in the United Kingdom. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baalbaki, N.A.; Fava, J.P.; Ng, M.; Okorafor, E.; Nawaz, A.; Chiu, W.; Salim, A.; Cha, R.; Kilgore, P.E. A community-based survey to assess knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and practices regarding herpes zoster in an urban setting. Infect. Dis. 2019, 8, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joon Lee, T.; Hayes, S.; Cummings, D.M.; Cao, Q.; Carpenter, K.; Heim, L.; Edwards, H. Herpes zoster knowledge, prevalence, and vaccination rate by race. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2013, 26, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donadiki, E.; Garcia, R.J.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Sourtzi, P.; Carrasco-Garrido, P.; Lopez-De-Andres, A.; Jimenez-Trujillo, I.; Velonakis, E. Health belief model applied to non-compliance with HPV vaccine among female university students. Public Health 2014, 128, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coe, A.B.; Gatewood, S.B.; Moczygemba, L.R. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the novel (2009) H1N1 influenza vaccine. Innov. Pharm. 2012, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooling, K.L.; Guo, A.; Patel, M.; Lee, G.M.; Moore, K.; Belongia, E.; Harpaz, R. Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices for use of herpes zoster vaccines. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardellini, M.; Farcomeni, A.; Ballanti, M.; Morelli, M.; Davato, F.; Cardolini, I.; Grappasonni, G.; Rizza, S.; Guglielmi, V.; Porzio, O.; et al. C-peptide: A predictor of cardiovascular mortality in subjects with established atherosclerotic disease. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2017, 14, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoto, E.; Cenko, F.; Doci, P.; Rizza, S. Effect of night shift work on risk of diabetes in healthy nurses in Albania. Acta Diabetol. 2019, 56, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Acceptability of HZ Vaccination | Acceptability of HZ Vaccination if Advised by Their Physician | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 410) | Yes n (%) 104 (25.4) | Total (n = 306) | Yes n (%) 227 (74.2) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Median [IQR] | 56 (53–62) | 56 (53–61) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 270 | 77 (28.5) | 193 | 154 (79.8) |

| Female | 140 | 27 (19.3) | 113 | 73 (64.6) |

| Education | ||||

| <university | 150 | 34 (22.7) | 116 | 86 (74.1) |

| ≥university | 260 | 70 (26.9) | 190 | 141 (74.2) |

| Occupation | ||||

| Unemployed | 61 | 11 (18) | 50 | 33 (66) |

| Employed | 115 | 30 (26.1) | 85 | 67 (78.8) |

| Retired | 234 | 63 (26.9) | 171 | 127 (74.3) |

| Do you know the disease called varicella? | ||||

| Yes | 351 | 91 (25.9) | 260 | 194 (74.6) |

| No | 59 | 13 (22) | 46 | 33 (71.7) |

| Have you had varicella in the past? | ||||

| Yes | 151 | 44 (29.1) | 107 | 83 (77.6) |

| No | 133 | 31 (23.3) | 102 | 77 (75.5) |

| Do not remember | 126 | 29 (23) | 67 | 67 (69.1) |

| Have you been vaccinated against varicella? | ||||

| Yes | 35 | 9 (25.7) | 26 | 24 (92.3) |

| No | 180 | 47 (26.1) | 133 | 97 (72.9) |

| Do not remember | 195 | 48 (24.6) | 147 | 106 (72.1) |

| Do you know the disease called shingles? | ||||

| Yes | 234 | 69 (29.5) | 165 | 117 (70.9) |

| No | 176 | 35 (19.9) | 141 | 110 (78) |

| Do you know someone who has had shingles? | ||||

| Yes | 251 | 73 (29.1) | 178 | 124 (69.7) |

| No | 159 | 31 (19.5) | 128 | 103 (80.5) |

| Have you had shingles in the past? | ||||

| Yes | 23 | 9 (39.1) | 14 | 6 (42.9) |

| No | 387 | 95 (24.6) | 292 | 221 (75.7) |

| There is a vaccine for shingles. | ||||

| Yes | 219 | 68 (31.1) | 151 | 104 (68.9) |

| No | 191 | 36 (18.9) | 155 | 123 (79.4) |

| Do you think that vaccines are effective for prevention? | ||||

| Yes | 82 | 44 (53.7) | 38 | 30 (79) |

| No | 328 | 60 (18.3) | 268 | 197 (73.5) |

| If an individual has chickenpox, he/she will be at risk of contracting HZ. | ||||

| Yes | 27 | 15 (55.6) | 12 | 8 (66.7) |

| No | 383 | 89 (23.2) | 294 | 219 (74.5) |

| Immunocompromised individuals are at a higher risk of contracting HZ. | ||||

| Yes | 138 | 56 (40.6) | 82 | 59 (72) |

| No | 272 | 48 (17.7) | 224 | 168 (75) |

| Variables | Bivariate Analysis | p-Value | Multivariable Analysis | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |||

| Age | 1.01 (0.98–1.05) | 0.541 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 1.67 (1.02–2.74) | 0.043 | 2.01 (1.01–4.00) | 0.047 |

| Education | ||||

| <university | Reference | |||

| ≥university | 1.26 (0.79–2.01) | 0.341 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Employed | Reference | Reference | ||

| Unemployed | 0.62 (0.29–1.35) | 0.231 | 0.84 (0.30–2.38) | 0.741 |

| Retired | 1.04 (0.63–1.73) | 0.868 | 1.01 (0.57–1.81) | 0.967 |

| Knowing the varicella disease | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.24 (0.64–2.40) | 0.526 | ||

| History of varicella infection | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.36 (0.87–2.15) | 0.181 | 1.27 (0.76–2.12) | 0.360 |

| History of varicella vaccine | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.02 (0.46–2.25) | 0.960 | ||

| Knowing about shingles | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.68 (1.06–2.68) | 0.028 | 1.23 (0.65–2.33) | 0.526 |

| Knowing someone who had shingles | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.69 (1.05–2.73) | 0.031 | 1.19 (0.62–2.27) | 0.597 |

| History of shingles | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.97 (0.83–4.71) | 0.124 | 1.54 (0.54–4.39) | 0.418 |

| Knowing that there are HZ vaccines | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.94 (1.22–3.08) | 0.005 | 1.27 (0.75–2.14) | 0.378 |

| HZ vaccines are effective | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 5.17 (3.09–8.67) | <0.001 | 3.94 (2.25–6.90) | <0.001 |

| At risk of contracting HZ if you had chickenpox | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 4.13 (1.86–9.15) | <0.001 | 1.31 (0.50–3.42) | 0.581 |

| Immunocompromised individuals are at a higher risk of contracting HZ | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 3.19 (2.01–5.05) | <0.001 | 2.32 (1.37–3.93) | 0.002 |

| Variables | Bivariate Analysis | p-Value | Multivariable Analysis | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |||

| Age | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 0.219 | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 0.114 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 2.16 (1.28–3.65) | 0.004 | 2.37 (1.18–4.79) | 0.016 |

| Education | ||||

| <university | Reference | |||

| ≥university | 1.00 (0.59–1.70) | 0.989 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Employed | Reference | Reference | ||

| Unemployed | 0.52 (0.24–1.14) | 0.103 | 1.55 (0.55–4.39) | 0.406 |

| Retired | 0.78 (0.42–1.45) | 0.424 | 1.20 (0.59–2.45) | 0.612 |

| Knowing the varicella disease | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.16 (0.58–2.33) | 0.681 | ||

| History of varicella infection | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.32 (0.76–2.29) | 0.322 | ||

| History of varicella vaccine | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 4.55 (1.05–19.72) | 0.043 | 4.50 (1.02–19.86) | 0.047 |

| Knowing about shingles | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.69 (0.41–1.16) | 0.158 | 1.20 (0.61–2.38) | 0.599 |

| Knowing someone who had HZ | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.56 (0.32–0.96) | 0.034 | 0.68 (0.35–1.34) | 0.266 |

| History of shingles | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.24 (0.10–0.72) | 0.011 | 0.33 (0.09–0.60) | 0.065 |

| Knowing that there are HZ vaccines | ||||

| No | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.58 (0.34–0.97) | 0.037 | 0.63 (0.36–1.09) | 0.100 |

| HZ vaccines are effective | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.35 (0.59–3.09) | 0.475 | ||

| At risk of contracting HZ if you had chickenpox | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.68 (0.20–2.34) | 0.546 | ||

| Immunocompromised individuals are at a higher risk of contracting HZ | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.86 (0.48–1.51) | 0.590 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Orini, D.; Alshoshan, A.A.; Almutiri, A.O.; Almreef, A.A.; Alrashidi, E.S.; Almutiq, A.M.; Noman, R.; Al-Wutayd, O. Acceptability of Herpes Zoster Vaccination among Patients with Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Vaccines 2023, 11, 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030651

Al-Orini D, Alshoshan AA, Almutiri AO, Almreef AA, Alrashidi ES, Almutiq AM, Noman R, Al-Wutayd O. Acceptability of Herpes Zoster Vaccination among Patients with Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Vaccines. 2023; 11(3):651. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030651

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Orini, Dawood, Abdulrahman A. Alshoshan, Abdullah O. Almutiri, Abdulsalam A. Almreef, Essa S. Alrashidi, Abdulrahman M. Almutiq, Rehana Noman, and Osama Al-Wutayd. 2023. "Acceptability of Herpes Zoster Vaccination among Patients with Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia" Vaccines 11, no. 3: 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030651

APA StyleAl-Orini, D., Alshoshan, A. A., Almutiri, A. O., Almreef, A. A., Alrashidi, E. S., Almutiq, A. M., Noman, R., & Al-Wutayd, O. (2023). Acceptability of Herpes Zoster Vaccination among Patients with Diabetes: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Vaccines, 11(3), 651. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030651