COVID-19 Vaccine Knowledge, Attitude, Acceptance and Hesitancy among Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Systematic Review of Hospital-Based Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Collection

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

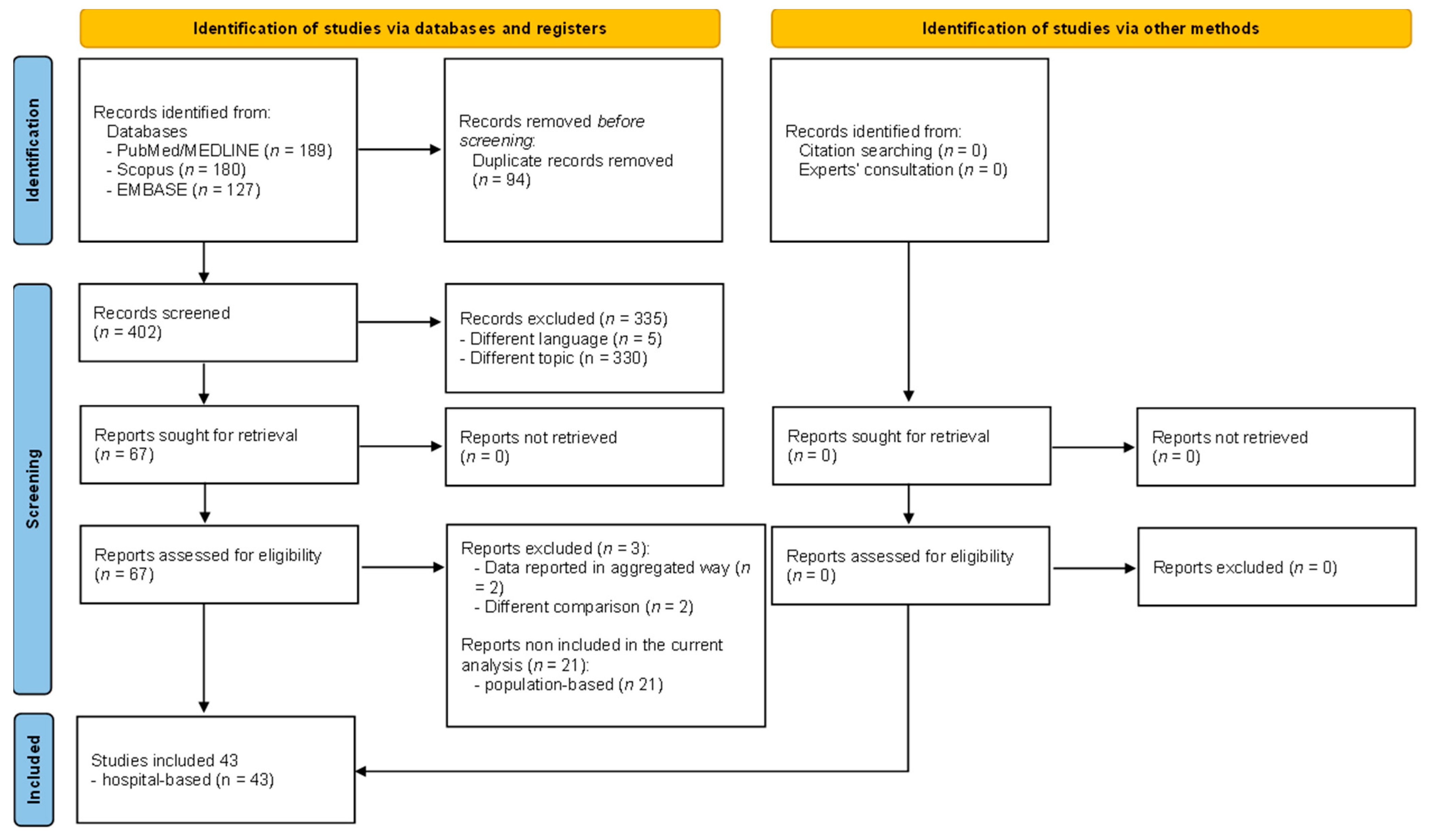

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Main Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Main Characteristics of Studied Population

3.4. Knowledge and Attitude toward COVID-19 Vaccine

3.5. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance

3.5.1. Socio-Demographic Data

3.5.2. Lifestyle Factors

3.5.3. Health Related Aspects

3.5.4. Pregnancy Characteristics

3.5.5. COVID-19 Related Aspects

3.6. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy

3.6.1. Socio-Demographic Data

3.6.2. Lifestyle Factors

3.6.3. Health Related Aspects

3.6.4. Pregnancy Characteristics

3.6.5. COVID-19 Related Aspects

3.7. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policies and Practices

4.2. Strenghts and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shook, L.L.; Kishkovich, T.P.; Edlow, A.G. Countering COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Pregnancy: The “4 Cs”. Am. J. Perinatol. 2022, 39, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiefer, M.K.; Mehl, R.; Costantine, M.M.; Johnson, A.; Cohen, J.; Summerfield, T.L.; Landon, M.B.; Rood, K.M.; Venkatesh, K.K. Characteristics and perceptions associated with COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among pregnant and postpartum individuals: A cross-sectional study. BJOG 2022, 129, 1342–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellino, M.; Lamanna, B.; Vinciguerra, M.; Tafuri, S.; Stefanizzi, P.; Malvasi, A.; Di Vagno, G.; Cormio, G.; Loizzi, V.; Cazzato, G.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines and Adverse Effects in Gynecology and Obstetrics: The First Italian Retrospective Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Hum. Vaccine Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClure, C.C.; Cataldi, J.R.; O’Leary, S.T. Vaccine Hesitancy: Where We Are and Where We Are Going. Clin. Ther. 2017, 39, 1550–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization AoaoD. Top Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- De Luca Picione, R.; Martini, E.; Cicchella, S.; Forte, S.; Carranante, M.; Tateo, L.; Rhodes, P. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic: Psycho-social perception of the crisis and sense-making processes. Community Psychol. Glob. Perspect. 2021, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Hwang, J.; Su, M.H.; Wagner, M.W.; Shah, D. Ideology and COVID-19 Vaccination Intention: Perceptual Mediators and Communication Moderators. J. Health Commun. 2022, 27, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, J.; Seng, J.J.B.; Seah, S.S.Y.; Low, L.L. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy-A Scoping Review of Literature in High-Income Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. New CDC Data: COVID-19 Vaccination Safe for Pregnant People. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s0811-vaccine-safe-pregnant.html (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfredi, V.; Berti, A.; D’Amico, M.; De Lorenzo, V.; Castaldi, S. Knowledge, Attitudes, Behavior, Acceptance, and Hesitancy in Relation to the COVID-19 Vaccine among Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women: A Systematic Review Protocol. Women 2023, 3, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools. 2017. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Alshahrani, S.M.; Alotaibi, A.; Almajed, E.; Alotaibi, A.; Alotaibi, K.; Albisher, S. Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women’s Attitudes and Fears Regarding COVID-19 Vaccination: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Womens Health 2022, 14, 1629–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuciel, N.; Mazurek, J.; Hap, K.; Marciniak, D.; Biernat, K.; Sutkowska, E. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Pregnant and Lactating Women and Mothers of Young Children in Poland. Int. J. Womens Health 2022, 14, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Kumari, S.; Kujur, M.; Tirkey, S.; Singh, S.B. Acceptance Rate of COVID-19 Vaccine and Its Determinants Among Indian Pregnant Women: A Hospital-Based Cross-Sectional Analysis. Cureus 2022, 14, e30682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfredi, V.; Stefanizzi, P.; Berti, A.; D’Amico, M.; De Lorenzo, V.; Lorenzo, A.D.; Moscara, L.; Castaldi, S. A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies Assessing Knowledge, Attitudes, Acceptance, and Hesitancy of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women towards the COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccine 2023, 11, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, O.; Khan, S.; Shahnawaz, S.; Ismail, S.; Khan, S.; Yasmin, H.; Sciences, H. Acceptance and Rejection of COVID-19 Vaccine among Pregnant and Breast Feeding Women—A survey conducted in Outpatient Department of a tertiary care setup. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 16, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aynalem, Z.B.; Bogale, T.W.; Bantie, G.M.; Ayalew, A.F.; Tamir, W.; Feleke, D.G.; Yazew, B.G. Factors associated with willingness to take COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant women at Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: A multicenter institution-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagalb, A.S.; Almazrou, D.; Albraiki, A.A.; Alflaih, L.I.; Bamunif, L.O.; Albraiki, A.; Alflaih, L.; Bamunif, L.J.C. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant and lactating women in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e32133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeway, H.; Prasad, S.; Kalafat, E.; Heath, P.T.; Ladhani, S.N.; Le Doare, K.; Magee, L.A.; O’Brien, P.; Rezvani, A.; von Dadelszen, P.; et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: Coverage and safety. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 236.e1–236.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, L.; Mappa, I.; Sirico, A.; Di Girolamo, R.; Saccone, G.; Di Mascio, D.; Donadono, V.; Cuomo, L.; Gabrielli, O.; Migliorini, S.; et al. Pregnant women’s perspectives on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccine. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2021, 3, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawanpaiboon, S.; Anuwutnavin, S.; Kanjanapongporn, A.; Pooliam, J.; Titapant, V. Breastfeeding women’s attitudes towards and acceptance and rejection of COVID-19 vaccination: Implementation research. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chekol Abebe, E.; Ayalew Tiruneh, G.; Asmare Adela, G.; Mengie Ayele, T.; Tilahun Muche, Z.; Behaile, T.M.A.; Tilahun Mulu, A.; Abebe Zewde, E.; Dagnaw Baye, N.; Asmamaw Dejenie, T. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Debre Tabor public health institutions: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 919494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citu, C.; Chiriac, V.D.; Citu, I.M.; Gorun, O.M.; Burlea, B.; Bratosin, F.; Popescu, D.E.; Ratiu, A.; Buca, O.; Gorun, F. Appraisal of COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance in the Romanian Pregnant Population. Vaccines 2022, 10, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citu, I.M.; Citu, C.; Gorun, F.; Motoc, A.; Gorun, O.M.; Burlea, B.; Bratosin, F.; Tudorache, E.; Margan, M.M.; Hosin, S.; et al. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy among Romanian Pregnant Women. Vaccines 2022, 10, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, D.; McDougall, A.; Prophete, A.; Sivashanmugarajan, V.; Yoong, W. COVID-19 vaccination: Patient uptake and attitudes in a multi-ethnic North London maternity unit. Postgrad. Med. J. 2022, 98, 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DesJardin, M.; Raff, E.; Baranco, N.; Mastrogiannis, D. Cross-Sectional Survey of High-Risk Pregnant Women’s Opinions on COVID-19 Vaccination. Womens Health Rep. 2022, 3, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ercan, A.; Şenol, E.; Fırat, A. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Pregnancy: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 32, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzbakht, M.; Sharif Nia, H.; Kazeminavaei, F.; Rashidian, P. Hesitancy about COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant women: A cross-sectional study based on the health belief model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, S.; Stephens, L.C.; Feemster, K.A.; Drew, R.J.; Eogan, M.; Butler, K.M. “This choice does not just affect me.” Attitudes of pregnant women toward COVID-19 vaccines: A mixed-methods study. Hum. Vaccine Immunother. 2021, 17, 3371–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, T.; Balis, B.; Eyeberu, A.; Debella, A.; Nigussie, S.; Habte, S.; Eshetu, B.; Bekele, H.; Alemu, A.; Dessie, Y. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women attending antenatal care in public hospitals in eastern Ethiopia: A multi-center facility-based cross-sectional study. Public. Health Pract. 2022, 4, 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncu Ayhan, S.; Oluklu, D.; Atalay, A.; Menekse Beser, D.; Tanacan, A.; Moraloglu Tekin, O.; Sahin, D. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in pregnant women. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 154, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Christina, S.; Umar, A.Y.; Laishram, J.; Akoijam, B.S. COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy among pregnant women: A facility-based cross-sectional study in Imphal, Manipur. Indian. J. Public Health 2022, 66, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husain, F.; Powys, V.R.; White, E.; Jones, R.; Goldsmith, L.P.; Heath, P.T.; Oakeshott, P.; Razai, M.S. COVID-19 vaccination uptake in 441 socially and ethnically diverse pregnant women. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagoz Ozen, D.S.; Karagoz Kiraz, A.; Yurt, O.F.; Kilic, I.Z.; Demirag, M.D. COVID-19 Vaccination Rates and Factors Affecting Vaccine Hesitancy among Pregnant Women during the Pandemic Period in Turkey: A Single-Center Experience. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya Odabas, R.; Demir, R.; Taspinar, A. Knowledge and attitudes of pregnant women about Coronavirus vaccines in Turkiye. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 3484–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Mahey, R.; Kachhawa, G.; Kumari, R.; Bhatla, N. Knowledge, attitude, perceptions, and concerns of pregnant and lactating women regarding COVID-19 vaccination: A cross-sectional survey of 313 participants from a tertiary care centre of North India. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2022, 16, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraglia Del Giudice, G.; Folcarelli, L.; Napoli, A.; Corea, F.; Angelillo, I.F.; Collaborative Working, G. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy and willingness among pregnant women in Italy. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 995382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mose, A. Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine and Its Determinant Factors Among Lactating Mothers in Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 4249–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mose, A.; Yeshaneh, A. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Its Associated Factors Among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care Clinic in Southwest Ethiopia: Institutional-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 2385–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Bashir, S.; Shahid, A.; Raees, I.; Salman, M.; Merchant, H.A.; Aldeyab, M.A.; Kow, C.S.; Hasan, S.S. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Clinics in Pakistan: A Multicentric, Prospective, Survey-Based Study. Viruses 2022, 14, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzal, Z.; Mohammad, A.; Qub, L.; Masri, H.; Abdullah, I.; Qasrawi, H.; Maraqa, B. Coverage and Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccination Among Pregnant Women: An Experience From a Low-Income Country. Am. J. Health Promot. 2023, 37, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemat, A.; Yaftali, S.; Danishmand, T.J.; Nemat, H.; Raufi, N.; Asady, A. High rates of COVID-19 vaccine refusal among Afghan pregnant women: A cross sectional study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.H.; Hoang, M.T.; Nguyen, L.D.; Ninh, L.T.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, A.D.; Vu, L.G.; Vu, G.T.; Doan, L.P.; Latkin, C.A.; et al. Acceptance and willingness to pay for COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women in Vietnam. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2021, 26, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oluklu, D.; Goncu Ayhan, S.; Menekse Beser, D.; Uyan Hendem, D.; Ozden Tokalioglu, E.; Turgut, E.; Sahin, D. Factors affecting the acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine in the postpartum period. Hum. Vaccine Immunother. 2021, 17, 4043–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pairat, K.; Phaloprakarn, C. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy among Thai pregnant women and their spouses: A prospective survey. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premji, S.S.; Khademi, S.; Forcheh, N.; Lalani, S.; Shaikh, K.; Javed, A.; Saleem, E.; Babar, N.; Muhabat, Q.; Jabeen, N.; et al. Psychological and situational factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine intention among postpartum women in Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e063469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riad, A.; Jouzova, A.; Ustun, B.; Lagova, E.; Hruban, L.; Janku, P.; Pokorna, A.; Klugarova, J.; Koscik, M.; Klugar, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance of Pregnant and Lactating Women (PLW) in Czechia: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, M.R.; Lumbreras-Marquez, M.I.; James, K.; McBay, B.R.; Gray, K.J.; Schantz-Dunn, J.; Diouf, K.; Goldfarb, I.T. Perceptions and Attitudes toward COVID-19 Vaccination among Pregnant and Postpartum Individuals. Am. J. Perinatol. 2022, 29, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, M.Y.; Hosek, M.G.; Stumpff, S.K.; Neuhoff, B.K.; Hernandez, B.S.; Wang, Z.; Ramsey, P.S.; Boyd, A.R. Sociodemographic predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and leading concerns with COVID-19 vaccines among pregnant women at a South Texas clinic. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 10368–10374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznajder, K.K.; Kjerulff, K.H.; Wang, M.; Hwang, W.; Ramirez, S.I.; Gandhi, C.K. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and associated factors among pregnant women in Pennsylvania 2020. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 26, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Wang, R.; Han, N.; Liu, J.; Yuan, C.; Deng, L.; Han, C.; Sun, F.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in China: A multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. Hum. Vaccine Immunother. 2021, 17, 2378–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatarevic, T.; Tkalcec, I.; Stranic, D.; Tesovic, G.; Matijevic, R. Knowledge and attitudes of pregnant women on maternal immunization against COVID-19 in Croatia. J. Perinat. Med. 2023, 51, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taye, E.B.; Taye, Z.W.; Muche, H.A.; Tsega, N.T.; Haile, T.T.; Tiguh, A.E. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and associated factors among women attending antenatal and postnatal cares in Central Gondar Zone public hospitals, Northwest Ethiopia. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2022, 14, 100993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tefera, Z.; Assefaw, M. A Mixed-Methods Study of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Its Determinants Among Pregnant Women in Northeast Ethiopia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 2287–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainstock, T.; Sergienko, R.; Orenshtein, S.; Sheiner, E. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination likelihood during pregnancy. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2023, 161, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Megaw, L.; White, S.; Bradfield, Z. COVID-19 vaccination rates in an antenatal population: A survey of women’s perceptions, factors influencing vaccine uptake and potential contributors to vaccine hesitancy. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 62, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Choi, B.Y.; Seong, W.J.; Cho, G.J.; Na, S.; Jung, Y.M.; Jo, J.H.; Ko, H.S.; Park, J.S. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance during Pregnancy and Influencing Factors in South Korea. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, D. The Intersections Between Social Determinants of Health, Health Literacy, and Health Disparities. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2020, 269, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilder, M.E.; Kulie, P.; Jensen, C.; Levett, P.; Blanchard, J.; Dominguez, L.W.; Portela, M.; Srivastava, A.; Li, Y.; McCarthy, M.L. The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, S.; MacDonald, N.E.; Marti, M.; Dumolard, L. Vaccine hesitancy around the globe: Analysis of three years of WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form data-2015-2017. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3861–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venerito, V.; Stefanizzi, P.; Fornaro, M.; Cacciapaglia, F.; Tafuri, S.; Perniola, S.; Iannone, F.; Lopalco, G. Immunogenicity of BNT162b2 mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in patients with psoriatic arthritis on TNF inhibitors. RMD Open 2022, 8, e001847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumptre, I.; Tolppa, T.; Blair, M. Parent and staff attitudes towards in-hospital opportunistic vaccination. Public Health 2020, 182, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallone, M.S.; Infantino, V.; Ferorelli, D.; Stefanizzi, P.; De Nitto, S.; Tafuri, S. Vaccination coverage in patients affected by chronic diseases: A 2014 cross-sectional study among subjects hospitalized at Bari Policlinico General Hospital. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, e9–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstetter, A.M.; Schaffer, S. Childhood and Adolescent Vaccination in Alternative Settings. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, S50–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, J.; Caci, G.; Hyeraci, G.; Albano, L.; Gianfredi, V. COVID-19 mRNA vaccine safety, immunogenicity, and effectiveness in a hospital setting: Confronting the challenge. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, L.; Young, J.; Williams, L.A.; Cooke, M.; Rickard, C. Opportunistic immunisation in the emergency department: A survey of staff knowledge, opinion and practices. Australas Emerg. Nurs. J. 2014, 17, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veli, N.; Martin, C.A.; Woolf, K.; Nazareth, J.; Pan, D.; Al-Oraibi, A.; Baggaley, R.F.; Bryant, L.; Nellums, L.B.; Gray, L.J.; et al. The UK-REACH Study Collaborative Group. Hesitancy for receiving regular SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in UK healthcare workers: A cross-sectional analysis from the UK-REACH study. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odejinmi, F.; Mallick, R.; Neophytou, C.; Mondeh, K.; Hall, M.; Scrivener, C.; Tibble, K.; Turay-Olusile, M.; Deo, N.; Oforiwaa, D.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A midwifery survey into attitudes towards the COVID-19 vaccine. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcon, M.; Rodriguez-Blazquez, C.; Romay-Barja, M.; Ayala, A.; Burgos, A.; De Tena-Davila, M.J.; Forjaz, M.J. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Spain and associated factors. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1129079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Alias, H.; Danaee, M.; Wong, L.P. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: A nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni Afshar, Z.; Babazadeh, A.; Janbakhsh, A.; Afsharian, M.; Saleki, K.; Barary, M.; Ebrahimpour, S. Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia after vaccination against COVID-19: A clinical dilemma for clinicians and patients. Rev. Med. Virol. 2022, 32, e2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kricorian, K.; Civen, R.; Equils, O. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Misinformation and perceptions of vaccine safety. Hum. Vaccine Immunother. 2022, 18, 1950504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skafle, I.; Nordahl-Hansen, A.; Quintana, D.S.; Wynn, R.; Gabarron, E. Misinformation about COVID-19 Vaccines on Social Media: Rapid Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e37367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feemster, K.A. Building vaccine acceptance through communication and advocacy. Hum. Vaccine Immunother. 2020, 16, 1004–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanath, K.; Bekalu, M.; Dhawan, D.; Pinnamaneni, R.; Lang, J.; McLoud, R. Individual and social determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licata, F.; Romeo, M.; Riillo, C.; Di Gennaro, G.; Bianco, A. Acceptance of recommended vaccinations during pregnancy: A cross-sectional study in Southern Italy. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1132751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvin, A.M.; Garg, A.; Moore, J.D.; Litt, D.M.; Thompson, E.L. Quality over quantity: Human papillomavirus vaccine information on social media and associations with adult and child vaccination. Hum. Vaccine Immunother. 2021, 17, 3587–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, T.E.; Paladini, A.; Marziali, E.; Gianfredi, V.; Blandi, L.; Signorelli, C.; Odone, A.; Ricciardi, W.; Damiani, G.; Cadeddu, C. Training needs assessment of European frontline health care workers on vaccinology and vaccine acceptance: A systematic review. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfredi, V.; Oradini-Alacreu, A.; Sá, R.; Blandi, L.; Cadeddu, C.; Ricciardi, W.; Signorelli, C.; Odone, A. Frontline health workers: Training needs assessment on immunisation programme. An EU/EEA-based survey. J. Public Health 2023, 1, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigezzi, G.P.; Lume, A.; Minerva, M.; Nizzero, P.; Biancardi, A.; Gianfredi, V.; Odone, A.; Signorelli, C.; Moro, M. Safety surveillance after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination: Results from a cross-sectional survey among staff of a large Italian teaching hospital. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, C.; Odone, A.; Gianfredi, V.; Capraro, M.; Kacerik, E.; Chiecca, G.; Scardoni, A.; Minerva, M.; Mantecca, R.; Musaro, P.; et al. Application of the “immunization islands” model to improve quality, efficiency and safety of a COVID-19 mass vaccination site. Ann. Ig. 2021, 33, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfredi, V.; Minerva, M.; Casu, G.; Capraro, M.; Chiecca, G.; Gaetti, G.; Mantecca Mazzocchi, R.; Musaro, P.; Berardinelli, P.; Basteri, P.; et al. Immediate adverse events following COVID-19 immunization. A cross-sectional study of 314,664 Italian subjects. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannotta, G.; Murrone, A.; Giannotta, N. COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines: The Molecular Basis of Some Adverse Events. Vaccines 2023, 11, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.A.; Failla, G.; Puleo, V.; Melnyk, A.; Lontano, A.; Ricciardi, W. Social media and attitudes towards a COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review of the literature. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 48, 101454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porat, T.; Nyrup, R.; Calvo, R.A.; Paudyal, P.; Ford, E. Public Health and Risk Communication During COVID-19-Enhancing Psychological Needs to Promote Sustainable Behavior Change. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 573397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfredi, V.; Grisci, C.; Nucci, D.; Parisi, V.; Moretti, M. Communication in health. Recenti. Prog. Med. 2018, 109, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scendoni, R.; Fedeli, P.; Cingolani, M. The State of Play on COVID-19 Vaccination in Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women: Recommendations, Legal Protection, Ethical Issues and Controversies in Italy. Healthcare 2023, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar, T.L.; Pollard, D.L.; Pina-Thomas, D.M.; Benton, M.J. Parental vaccine hesitancy and concerns regarding the COVID-19 virus. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 65, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desye, B. Prevalence and Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance Among Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 941206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfredi, V.; Balzarini, F.; Gola, M.; Mangano, S.; Carpagnano, L.F.; Colucci, M.E.; Gentile, L.; Piscitelli, A.; Quattrone, F.; Scuri, S.; et al. Leadership in Public Health: Opportunities for Young Generations Within Scientific Associations and the Experience of the “Academy of Young Leaders”. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallé, F.; Quaranta, A.; Napoli, C.; Diella, G.; De Giglio, O.; Caggiano, G.; Di Muzio, M.; Stefanizzi, P.; Orsi, G.B.; Liguori, G.; et al. How do Vaccinators Experience the Pandemic? Lifestyle Behaviors in a Sample of Italian Public Health Workers during the COVID-19 Era. Vaccines 2022, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licata, F.; Pelullo, C.P.; Della Polla, G.; Citrino, E.A.; Bianco, A. Immunization during pregnancy: Do healthcare workers recommend vaccination against influenza? Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1171142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author Name | Study Period | Study Design | Country | Study Settings | Recruitment Methods | Administration Method | Tool(s) Used to Assess the Outcomes | Validation (Yes/No) | Funds | Conflicts of Interests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akhtar, 2022 [20] | October– November 2021 | cross- sectional | Pakistan | Outpatient Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology | consecutive women | n.a. | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | n.a. | no |

| Aynalem, Z. B., 2022 [21] | August– September 2021 | cross- sectional | Ethiopia | antenatal care at selected public health institutions | antenatal care registry | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.87 | no | no |

| Bagalb, 2022 [22] | November 2021– February 2022 | cross- sectional | Saudi Arabia | maternity department of the tertiary care setting | snow ball technique | self- administered | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | n.a. | no |

| Blakeway, 2022 [23] | March 2020–July 2021 | cohort | United Kingdom | University Hospitals (London) | n.a. | n.a. | electronic medical records | n.a. | no | no |

| Carbone, 2021 [24] | January 2021 | cross- sectional | Italy | Two University teaching hospitals (Naples and Rome) | consecutive women | on-line | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | n.a. | n.a. |

| Chawanpaiboon, 2023 [25] | January–April 2022 | cohort | Thailand | postpartum ward | consecutive women | n.a. | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, no further details | n.a. | no |

| Chekol Abebe, E., 2022 [26] | March 2022 | cross- sectional | Ethiopia | Debre Tabor public health institutions | consecutive women | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no, developed based on literature | n.a. | no |

| Citu, C. 2022 [27] | January–May 2022 | cross-sectional | Romania | Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic | convenience sampling | on-line | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | no | no |

| Citu, I. M., 2022 [28] | October–December 2021 | cross-sectional | Romania | Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic of the Timisoara Municipal Emergency Hospital | convenience sampling | on-line | VAX (Vaccination Attitude Examination) scale | yes, no further details | no | no |

| Davies, 2022 [29] | October–November 2021 | cross-sectional | England | Hospital maternity department (antenatal clinics, maternity triage and maternity day unit) | consecutive women | on-line | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | no | no |

| DesJardin, M., 2022 [30] | September–October 2021 | cross-sectional | USA | Prenatal care at a central New York regional Maternal–Fetal Medicine clinic | consecutive women | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | no | no |

| Ercan, A., 2022 [31] | March–April 2021 | cross-sectional | Turkey | Outpatient Obstetrics Clinics of İstanbul Training and Research Hospital | n.a. | n.a. | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, Cronbach’s alpha 0.82 | no | no |

| Firouzbakht, M., 2022 [32] | October 2021–January 2022 | cross-sectional | Iran | public healthcare centers in the north of Iran | convenience sampling | self-administered | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | yes | no |

| Geoghegan, S., 2021 [33] | December 2020–January 2021 | cross-sectional | Ireland | prenatal care in hospital- based public, private, and semi-private clinics, and in community-based midwife-lead clinics | consecutive women | on-line | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | yes | no |

| Getachew, T., 2022 [34] | June 2021 | cross-sectional | Ethiopia | public hospitals of Dire Dawa city | random sampling techniques | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | no | no |

| Goncu Ayhan, S., 2021 [35] | January–February 2021 | cohort | Turkey | Ankara City Hospital | consecutive women | face-to-face | n.a. | no | n.a. | no |

| Gupta, A., 2022 [36] | July–August 2021 | cross-sectional | India | Gynecology and Obstetrics Department of a tertiary care institute | antenatal care registry | phone calls | questionnaire developed ad hoc | n.a. | no | no |

| Husain, 2022 [37] | September 2021–February 2022 | cross-sectional | England | antenatal clinic (general hospitals) | consecutive women | self-administered | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | no | n.a. |

| Karagöz, 2022 [38] | January–April 2022 | cross-sectional | Turkey | local hospital (Samsun Training and Research Hospital Gynecology and Obstetrics Outpatient Clinics) | consecutive women | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | no | no |

| Kiefer, 2022 [2] | March–April 2021 | cross-sectional | USA | general obstetrics, midwifery and maternal–fetal medicine clinics | consecutive women | face-to-face | the Attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine scale | yes, no further details | n.a. | no |

| Kumari, 2022 [18] | February–April 2022 | cross-sectional | India | antenatal clinic | consecutive women | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | n.a. | n.a. | no |

| Miraglia Del Giudice, 2022 [41] | September 2021–May 2022 | cross-sectional | Italy | two public hospitals | random sampling techniques | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, by opinion from experts | n.a. | no |

| Mose, 2021 [42] | February–March 2021 | cross-sectional | Ethiopia | hospital | consecutive women | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | no | no |

| Mose, A. and A. Yeshaneh 2021 [43] | January 2021 | cross-sectional | Ethiopia | Antenatal Care Clinic hospital | random sampling techniques | face-to-face | n.a. | yes, Cronbach’s alpha (α) = 0.79 | no | no |

| Mustafa, Z. U., 2022 [44] | December 2021–January 2022 | cohort | Pakistan | antenatal clinics from 7 hospitals | consecutive women | face-to-face and on-line | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no, developed based on literature | no | no |

| Nazzal, 2022 [45] | October–November 2021 | cross-sectional | Palestine | health care facilities | n.a. | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | no | no |

| Nemat, A., 2022 [46] | July–August 2021 | cross-sectional | Afghanistan | gynecology wards of several hospitals in Kabul | consecutive women | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients = 0.74 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Nguyen. 2021 [47] | January–February 2021 | cross-sectional | Vietnam | hospital (central and provincial) | consecutive women | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Odabas, 2022 [39] | September 2021–January 2022 | cross-sectional | Turkey | public hospital | consecutive women | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | no | no |

| Oluklu, D., 2021 [48] | February–March 2021 | cross-sectional | Turkey | Ankara City Hospital | n.a. | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | n.a. | no |

| Pairat, 2022 [49] | July–September 2021 | cohort | Thailand | Antenatal care | consecutive women | self-administered | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | yes | no |

| Premji, 2022 [50] | July–September 2020 | cross-sectional | Pakistan | 4 centres of Aga Khan Hospital for Women and Children | within the ongoing prospective longitudinal Pakistani cohort study | phone calls | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | yes | no |

| Riad, A., 2021 [51] | August–October 2021 | cross-sectional | Czechia | Gynecologic clinic of the University Hospital Brno | consecutive women | self-administered | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | yes | no |

| Siegel, 2022 [52] | June–August 2021 | cross-sectional | USA | health centers | consecutive women | n.a. | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | n.a. | n.a. |

| Sutanto, 2022 [53] | August–September 2021 | cross-sectional | USA | hospital south Texas | consecutive women | n.a. | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no, developed based on literature and considering the Health Believe Model | no | no |

| Sznajder, K. K., 2022 [54] | May–December 2020 | cross-sectional | USA | Mid-size academic medical center in Central Pennsylvania | consecutive women | on-line | questionnaire developed ad hoc | n.a. | yes | no |

| Tao, 2021 [55] | November 2020 | cross-sectional | China | obstetric clinics of 6 hospitals | multistage sampling approach | n.a. | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, Cronbach’s α coefficient= 0,81 | yes | no |

| Tatarevic, T., 2022 [56] | May–October 2021 | cross-sectional | Croatia | antenatal clinic in two teaching hospitals | consecutive women | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | no | no |

| Taye, E. B., 2022 [57] | August–September 2021 | cross-sectional | Ethiopia | Antenatal and postnatal cares in Central Gondar Zone public hospitals | random sampling techniques | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | no | no |

| Tefera, 2022 [58] | January 2022 | cross-sectional | Ethiopia | public hospitals | multistage sampling approach | face-to-face | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | n.a. | no |

| Wainstock, T., 2023 [59] | January–September 2021 | cohort | Israel | Soroka University Medical Center | antenatal care registry | n.a. | electronic medical records | yes | n.a. | no |

| Ward, 2022 [60] | September–October 2021 | cross-sectional | Australia | maternity units | consecutive women | on-line | questionnaire developed ad hoc | no | n.a. | no |

| Yoon, H., 2022 [61] | January–April 2022 | cross-sectional | South Corea | Mix of public and private clinics or hospitals | consecutive women | face-to-face and on-line | questionnaire developed ad hoc | yes, pre-tested | yes | no |

| Author Name | Main Characteristics of the Population | Women’s Age (Mean ± SD, or Range or %) | Sample Size | Attrition (Not Competition Rate) | Adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akhtar, 2022 [20] | Pregnant and breastfeeding women | 27.15 ± 4.788 years | 500 (249 pregnant, 251 breast feeding) | 28% | no |

| Aynalem, Z. B., 2022 [21] | Pregnant women | 30.7 ± 5.86 years | 525 | 2.9% | yes but not specified |

| Bagalb, 2022 [22] | Pregnant and breastfeeding women | n.a. | 300 (53.3% pregnant and 46.7% breastfeeding/lactating mothers) | 20% | no |

| Blakeway, 2022 [23] | Pregnant women | 30–37 years | 1328 | 26.8% | yes but not specified |

| Carbone, 2021 [24] | Pregnant and early postpartum patient | 34 (range 31−37.25) years | 142 (83.8% pregnant and 16.2% early postpartum period) | 15.5% | not applicable, chi-squared test |

| Chawanpaiboon, 2023 [25] | Breastfeeding women | 30.9 (range 15–43) years | 400 | n.a. | yes but not specified |

| Chekol Abebe, E., 2022 [26] | Pregnant women | 32.3 ± 4.14 (range 18–50) years | 634 | 0% | yes but not specified |

| Citu, C. 2022 [27] | Pregnant women | n.a. | 345 | 16.3% | no |

| Citu, I. M., 2022 [28] | Pregnant women | 30.6 ± 7.2 years | 184 | n.a. | knowledge, history of medical diseases, and history of reproductive problems |

| Davies, 2022 [29] | Pregnant women | n.a. | 202 | n.a. | not applicable, chi-squared test |

| DesJardin, M., 2022 [30] | High-risk pregnant women | n.a. | 157 | 22% | hierarchical Bayesian model |

| Ercan, A., 2022 [31] | Pregnant women | 18–49 years | 250 | n.a. | knowledge, history of medical diseases, and history of reproductive problems |

| Firouzbakht, M., 2022 [32] | Pregnant women | 20–35 years | 352 | 8% | knowledge, history of medical diseases, and history of reproductive problems |

| Geoghegan [33] | Pregnant women | 18–45 years | 300 | 12.3% | no |

| Getachew, T., 2022 [34] | Pregnant women | Mean age 28.92 ± 6.7 years | 645 | n.a. | yes but not specified |

| Goncu Ayhan, S., 2021 [35] | Pregnant women | 27.99 ± 5.6 | 300 | n.a. | not applicable, correlation analysis |

| Gupta, A., 2022 [36] | Pregnant not fully vaccinated before pregnancy | 28.3 ± 5.5 ye | 163 | 43% | yes but not specified |

| Husain, 2022 [37] | Pregnant women | 32.0 (17–44) | 441 | n.a. | not applicable, chi-squared test |

| Karagöz, 2022 [38] | Pregnant women | 28.7 ± 5.3 years | 247 | 11.7% | not applicable, chi-squared test |

| Kaya Odabas, 2022 [39] | Pregnant and postpartum individuals | 29 years (SD: 5.38 years) | 456 | 5.9% | age, parity, race, trimester of pregnancy, and chronic comorbidities |

| Kiefer, 2022 [2] | Pregnant women | 21–30 years = 79.69% | 298 | n.a. | yes but not specified |

| Kumari, 2022 [18] | Pregnant and breastfeeding | 32.2 ± 5.4 (range 19–46) years | 385 | 5.2% | yes but not specified |

| Miraglia Del Giudice, 2022 [41] | Lactating mothers | 25 ± 0.42 years | 630 | n.a. | yes but not specified |

| Mose, 2021 [42] | Pregnant women | 25.38 ± 3.809 years | 396 | 0 | yes but not specified |

| Mose, A. and A. Yeshaneh 2021 [43] | Pregnant women | 29.1 years | 405 | 37.7% | no |

| Mustafa, Z. U., 2022 [44] | Pregnant women | n.a. | 860 | 9.5% | yes but not specified |

| Nazzal, 2022 [45] | Pregnant women | 27.24 ± 5.698 years | 491 | 4.3% | not applicable, chi-squared test |

| Nemat, A., 2022 [46] | Pregnant women | 29.4 ± 5.0 years | 651 | 3.6% | no |

| Nguyen. 2021 [47] | Pregnant women | 26.33 ± 4.96 years | 400 | n.a. | no |

| Oluklu, D., 2021 [48] | Postpartum women | 28.69 ± 5.4 years | 412 (88.1% breastfeeding) | n.a. | not applicable, spearman correlation |

| Pairat, 2022 [49] | Pregnant women | 28 years (IQR 23–33 years) | 171 | 2.8% | no |

| Premji, 2022 [50] | Postpartum women | 26–30 years | 941 | 4.9% | no |

| Riad, A., 2021 [51] | Pregnant and lactating | 31.48 ± 4.56 (range 19–44) years | 362 (278 pregnant and 84 lactating) | 9.7% | yes but not specified |

| Siegel, 2022 [52] | Pregnant and postpartum | vaccinated 33.0 ± 4.5; unvaccinated 31.4 ± 5.6) | 473 | 0.8% | no |

| Sutanto, 2022 [53] | Pregnant women | 31 years among vaccinated, 28 years among not vaccinated | 109 | 8.4% | no |

| Sznajder, K. K., 2022 [54] | Pregnant women | <35 years 80%>35 years 20% | 196 | 5.7% | yes but not specified |

| Tao, 2021 [55] | Pregnant women | 55.4% equal or below 30 years old | 1392 | n.a. | age group, region, education, occupation, monthly household income per capita), health status (gravidity, parity, gestational trimester, history of adverse pregnancy outcomes, history of chronic disease, history of influenza vaccination, and gestational complications), total knowledge score on COVID-19 (as continuous variable), health belief (susceptibility, severity, barriers, benefits, and cues to action) |

| Tatarevic, T., 2022 [56] | Pregnant women | 31 (IQR = 27–36) years | 430 | 9% | not applicable, chi-squared test |

| Taye, E. B., 2022 [57] | Pregnant and postnatal women | 18–25; n = 19526–35; n = 29036–48, n = 34 | 519 (360 pregnant and 159 postnatal) | 1.5% | yes but not specified |

| Tefera, 2022 [58] | Pregnant women attending antenatal care | <20 up to 49 years | 702 | 0% | yes but not specified |

| Wainstock, T., 2023 [59] | Pregnant (women who delivered during the study period) | 20–35 years | 7017 | n.a. | yes but not specified |

| Ward, 2022 [60] | Pregnant women | 31.9 years | 218 | n.a. | not applicable, chi-squared test |

| Yoon, H., 2022 [61] | Pregnant or postpartum women | Among acceptant 33.28 ± 4.70 years; among refusal 33.65 ± 3.77 years | 533 (87.8% pregnant and 12.2% postpartum) | 15.4% | maternal age, occupation, and pregnancy period |

| Predicators of Vaccine Acceptance | Predictors of Vaccine Hesitancy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant | Not Significant | Significant | Not Significant | |

| Action | High level cues to action * aOR: 15.70 (8.28–29.80) [55] | Cues to action aOR: 0.621 (0.516–0.574) [32] | Self-efficacy [32] | |

| Age | Younger age aOR: 1.87 (1.20–2.93) [55]; 34–41 y aOR: 1.46 (1.22–5.13) [43]; age (continuous scale) aOR: 1.03 (1.02–1.05) [59]; age ≥ 35 y aOR: 5.68 (1.78–18.17) [21]; 30–35 y OR: 2.43 (1.25–4.75) [33] | Maternal age [23,26,35,42,45] | Age > 25 y aOR: 0.30 (0.17–0.54) [2]; age gravidity significantly different among groups [48] | Age [30,31,38] |

| Alcohol/Drugs | Alcohol [23] | Use of drugs [30], | ||

| Attitude | positive attitude aOR: 1.59 (1.09, 2.31) [58]; positive attitude aOR: 8.54 (5.18–14.08) [57]; good attitude aOR = 2.128, (1.348–3.360) [21], positive attitude significantly different among groups [24], | Attitude [42,43] | ||

| Barrier | low level of perceived barriers aOR: 4.76 (2.23–10.18) [55] | Perceived barriers [32], | ||

| Benefit | high level of perceived benefit aOR: 2.18 (1.36–3.49) [55]; perceived benefits aOR: 1.1 (1.06–1.16) [45]; risk/benefit ration 15.52 (2.78–86.80) [51] | Perceived benefits aOR: 0.700 (0.594–0.825) [32]; believe that vaccine will protect against COVID-19 OR: 0.1 (0.04–0.28) [53]; confidence in COVID-19 vaccine OR: 0.04 (0.02–0.13) [53]; feel confident in making a decision OR: 0.23 (0.07–0.73) [53]; not believing in vaccines aOR: 3.15 (2.80–3.49) [28]; vaccination not needed OR = 2.54 (1.11–5.75) [22] | ||

| BMI | BMI [23] | |||

| COVID-19 Fear | Worry about COVID-19 infection OR: 1.55 (0.55, 4.40) [49]; Fearing the severity of COVID-19 disease OR: 0.68 (0.34–0.82) [27]; fear of COVID-19 disease aOR: 3.46 (2.16–5.52) [57] | Fear of COVID-19 infection [41,61] | Not believing in the existence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus aOR: 2.67 (2.12–3.04) [28], no fear aOR = 1.89 (1.54–2.27) [28], lower fear of COVID-19 infection OR: 0.77 (0.64–0.93) [41], no COVID-19 anxiety symptoms OR: 2.32 (1.26–4.28) [50]; no obsession with COVID-19 symptoms OR: 2.22 (1.30–3.77) [50] | Perceived threat [32], |

| Data Availability | unavailability of data regarding safety during pregnancy and breast-feeding [20]; no need to receive information on COVID-19 vaccine 0.41 (0.21–0.79) [41]; feel the vaccine was rushed OR: 0,16 (0.10–0.27) [52]; believe people of their race were included in trials OR: 2.65 (1.79–3.92) [52] | |||

| Education | lower level of education (aOR: 2.49, (1.13–5.51) [55]; higher education OR: 0.81 (0.62–0.95) [27]; higher educational level 1.92 (1.03–3.57) [41]; higher educational level aOR: 4.2 (2.1–8.5) [34]; higher educational level aOR 3.48 (1.52–7.95) [43]; higher educational level 2.8 (1.51–4.21) [42]; higher educational level 5.99 (1.12–32.16) [51]; level of education significantly differed between groups [56] | Educational status [20,21,36,45,54] | Higher educational level aOR: 0.05 (0.02–0.13) [2]; lower educational level OR: 0.38 (0.15–0.92) [41]; lower education level OR: 3.42 (1.24–9.45) [22]; lower educational level aOR: 4.93 (2.47–9.83) [25] | Educational level [30,31,38,46,50] |

| Efficacy | Confidence in vaccine efficacy OR = 1.85 (0.38, 9.11) [49]; believe vaccine will protect them against COVID-19 OR: 0 10.75 (6.73–17.17) [52]; believe vaccine will protect their baby from COVID-19 OR: 6.36 (4.16–9.73) [52] | Believe that vaccine during pregnancy increase the newborn’s immunity aOR: 0.28 (0.08–0.98) [25] | Believe that vaccine is ineffective [41] | |

| Ethnicity | Afro-Caribbean 0.27 (0.06–0.85) [23]; Asian ethnicity significantly more frequently reported among vaccinated women [29]; Bedouin aOR 0.20 (0.18–0.23) [59] | Asian aOR: 0.11 (0.02–0.57) [2]; Sindhi OR: 0.43 (0.20–0.93) [50] | Ethnicity [30] | |

| Facility | Availability of vaccination centres nearby OR: 0.87 (0.63–0.99) [27] | |||

| Government Trust | awareness that COVID-19 vaccine has been approved by the government aOR: 3.03, CI: 1.45–6.36) [40]; Trusting the government OR: 0.83 (0.59–0.99) [27]; trust vaccine features OR: 6.52 (4.30–9.91) [52] | |||

| Health | chronic medical illness aOR: 2.41 (1.28, 4.54) [58]; underlying medical condition aOR: 2.1; (1.1–4.1) [45], 2022; diabetes 10.5 (1.74–8.32) [23]; history of chronic diseases 2.52 (1.34–4.7) [34]; having a pre-existing chronic disease aOR: 3.131 (1.700–5.766) [21], | Health status [41]; health condition [43]; comorbidities [35,36,59]; obesity [59]; diabetes [59] | Chronic comorbidities [2]; disease history [32] | |

| Husband | having a husband who favoured COVID-19 vaccination OR: 4.82 (2.34, 9.94) [49]; living with husband and children OR: 0.5 (0.28; 0.9) [47]; husbands’ educational level aOR: 1.99 (1.09, 3.64) [58] | Marital status [21] | Marital status [30], husband’s educational level [46] | |

| Infection | history of COVID-19 infection OR: 4.33 (2.31–8.12) [41] | History of COVID-19 infection [34,36,45]; antenatal COVID-19 [23]; tested COVID-19 positive [21] | History of COVID-19 infection aOR: 0.47 (0.24–0.90) [25] | History of COVID-19 [30]; tested COVID-19 positive [50] |

| Insurance | private health insurance OR: 0.46 (0.26; 0.82) [47] | Public health insurance aOR: 3.93 (2.41–6.43) [2]; insurance type correlated [30] | ||

| Knowledge | high knowledge score on COVID-19 aOR: 1.05, (1.01–1.10) [55]; Knowledge on COVID-19 vaccine aOR: 2.0; (1.2–3.1) [45]; good knowledge aOR 5.95 (3.15–7.07) [43]; good knowledge about vaccine aOR: 2.6 (1.84–3.47) [42]; good COVID-19 vaccine knowledge aOR: 9.56 (62.31, 39.53) [36]; good knowledge about COVID-19 vaccine aOR = 2.391, (1.144, 4.998) [21]; | Knowledge on COVID-19 infection [45] | COVID-19 knowledge [31,32] | |

| Employment | employment aOR: 5; (3.1–8.1) [45]; employed 2.22 (1.02–4.81) [54]; feeling overloaded 2.18 (1.02–4.68) [54] | Employment [20,21,34,43,51,61]; work related stress [54] | Employment OR: 4.47 (2.31–8.64) [44] | Employment [30,31,38] |

| Pregnancy | gravida > 2 aOR: 1.84 (1.30–2.61) [40]; late pregnancy (aOR: 1.49, (1.03–2.16) [55], recurrent pregnancy loss aOR: 0.78 (0.61–0.99) [59]; pregnancy status statistically significant different among groups [24], insufficient prenatal care aOR: 0.36 (0.30–0.42) [59]; infertility treatment aOR: 1.47 (1.18–1.83) [59]; poor obstetric history aOR: 0.65 (0.49–0.87) [59]; parity statistically significant different among groups [24] | Gravity [35]; number of antenatal care visit [21]; pregnancy a risk [41]; number of pregnancy [43]; history of abortion [21], parity [26]; previous pregnancy [51]; multiple gestation [59]; number of pregnancy [56] | Multiparity aOR: 2.07 (1.24–3.46) [2]; parity significantly different among groups [48]; childbirth during pandemic OR: 2.16 (1.17–4.00) [50]; no pregnancy-related issues OR: 6.02 (2.36–15.33) [44]; history of reproductive problems aOR: 2.327; (1.262 to 4.292) [32] | number of pregnancy [38], parity [46]; high risk pregnancy [31] |

| Gestational Week | Third trimester of pregnancy OR: 0.54 (0.28–0.86) [27]; later gestational age (OR 3.74, 95% CI 1.64–8.53) [33]; gestational week significantly differed among groups [56]; second trimester of pregnancy aOR: 7.35 (1.54–35.15) [61]; gestational week (third trimester): aOR 6.50 (1.21–35.03) [51] | Gestational week [35,45] | Gestational week [2,48] gravidity [46] | |

| Prevention | good practice of COVID-19 preventive measures aOR: 1.59 (1.09, 2.31) [58]; good practice aOR: 9.15 (8.73–12.19) [43]; good adherence to COVID-19 mitigation measures 3.2 (1.91–5.63) [42] | |||

| Residency | Western region aOR: 2.73, (1.72–4.32), [55]; urban area of residence OR: 0.86 (0.59–0.98) [27]; resident in urban area aOR: 2.03 (1.09–3.77) [57]; urban residency aOR: 2.5 (1.62–3.91) [42] | Living in rural area [34] | Resident area [46] | |

| Religion | Muslim religion aOR = 0.27 (0.12–0.61) [40] | Religion [20] | ||

| Safety | vaccine being harmful during pregnancy and breast-feeding for mother & baby [20]; confidence in vaccine safety OR: 1.66 (0.35, 7.97) [49]; fear of side effect aOR: 0.09 (0.02–4.98) [36]; COVID-19 vaccine to pregnant women would benefit her baby aOR: 18.47 (2.76–123.52) [36]; considering COVID-19 vaccine safe for both mother and fetus significantly different among groups [26], fear of side effect for pregnant OR: 0.18 (0.12–0.27) [52]; fear of side effect for baby OR: 0.17 (0.11–0.25) [52]; believe the vaccine will cause them COVID-19 infection OR: 0.21 (0.08–0.56) [52]; worried about toxins in the vaccine OR: 0.22 (0.13–0.38) [52] | Awareness that vaccine could protect fetus [61] | Fear of side effects for mother and newborn were significantly more frequently reported by unvaccinated women [60]; fear of side effects OR: 2.92 (1.09–7.79) [22] | |

| Smoking | Smoking [23,59], | Tobacco use aOR: 3.20 (1.46–7.01) [2] | Smoking [31] | |

| Cohabitation | Seeing more people getting vaccinated OR: 0.75 (0.33–0.88) [27]; living with a vaccinated family member significantly more frequently reported among vaccinated women [29]; living with a vaccinated member aOR: 2.43 (1.06–5.59) [61]; positive correlation between acceptance and number of school-age children [35]; having contact history with COVID-19 diagnosed people aOR: 7.724 (2.183, 27.329) [21] | Having a family member/friend lost to COVID-19 [21]; number of householders [35]; householders > 65 y [35] | Number of households significantly different among groups [48]; number of school children significantly different among groups [48]; know other pregnant women vaccinated OR: 0.26 (0.09–0.76) [53]; considering vaccination only if many people are vaccinated OR: 0.39 (0.19–0.81) [22]; need to consult relative before receiving the vaccine aOR: 2.58 (1.30–5.09) [25] | Number of housholds with comorbidities [48] |

| Income | lower income aOR: 0.10 (0.02–0.40) [23] | Socioeconomic status [20]; income [34,35,59] | Low income aOR: 2.06 (1.74–2.71) [28] | Income [46]; living situation [30]; economic status [31] |

| Susceptibility | high level of perceived susceptibility aOR: 2.18 (1.36–3.49) [55] | Not being aware that pregnant women are a priority group more frequently reported by unvaccinated women [60]; no awareness that pregnancy increased the risk of severe illness more frequently reported by unvaccinated women [60] | ||

| Travelling | Caring about travelling OR 0.76 (0.40–0.87) [27] | |||

| Source of Data | Official source of information OR: 2.92 (1.58–5.42) [41]; being exposed to COVID-19 vaccine information aOR: 2.2 (1.41–3.57) [34]; | Trusting rumours on social media aOR: 2.38 (1.90–2.94) [28]; not official source of information OR: 6.18 (2.53–15.09) [41]; social media news on vaccine safety aOR: 0.32 (0.13–0.84) [25] | ||

| Hcws’ Recommendation for Vaccination | having received recommendation from HCWs more frequently reported among vaccinated women [29]; immunization counselling received aOR: 3.4 (1.95–5.91) [42]; received vaccine recommendation from HCWs aOR: 3.41 (2.05–5.65) [61]; having received information form HCWs aOR: 4.36 (1.28–14.85) [51] | Having not received recommendation by HCWs more frequently reported by unvaccinated women [60]; consulted their doctors OR: 0.12 (0.04–0.35) [44]; recommendation from physician 0.34 (0.15–0.77) [22] | ||

| Having Received/Planned Other Vaccinations | having received influenza vaccine aOR 4.82 (2.17–10.72) [54]; willingness to receive pertussis and influenza vaccine were significantly different among groups [26]; received influenza or pertussis vaccine during pregnancy statistically significant different among groups [24] | Planning to receive flu vaccine during pregnancy OR: 0.11 (0.04–0.33) [53], planning to receive Tdap during pregnancy OR: 0.29 (0.1–0.87) [53], | Other vaccine [30] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gianfredi, V.; Berti, A.; Stefanizzi, P.; D’Amico, M.; De Lorenzo, V.; Moscara, L.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Venerito, V.; Castaldi, S. COVID-19 Vaccine Knowledge, Attitude, Acceptance and Hesitancy among Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Systematic Review of Hospital-Based Studies. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1697. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11111697

Gianfredi V, Berti A, Stefanizzi P, D’Amico M, De Lorenzo V, Moscara L, Di Lorenzo A, Venerito V, Castaldi S. COVID-19 Vaccine Knowledge, Attitude, Acceptance and Hesitancy among Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Systematic Review of Hospital-Based Studies. Vaccines. 2023; 11(11):1697. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11111697

Chicago/Turabian StyleGianfredi, Vincenza, Alessandro Berti, Pasquale Stefanizzi, Marilena D’Amico, Viola De Lorenzo, Lorenza Moscara, Antonio Di Lorenzo, Vincenzo Venerito, and Silvana Castaldi. 2023. "COVID-19 Vaccine Knowledge, Attitude, Acceptance and Hesitancy among Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Systematic Review of Hospital-Based Studies" Vaccines 11, no. 11: 1697. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11111697

APA StyleGianfredi, V., Berti, A., Stefanizzi, P., D’Amico, M., De Lorenzo, V., Moscara, L., Di Lorenzo, A., Venerito, V., & Castaldi, S. (2023). COVID-19 Vaccine Knowledge, Attitude, Acceptance and Hesitancy among Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: Systematic Review of Hospital-Based Studies. Vaccines, 11(11), 1697. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11111697